Submitted:

05 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

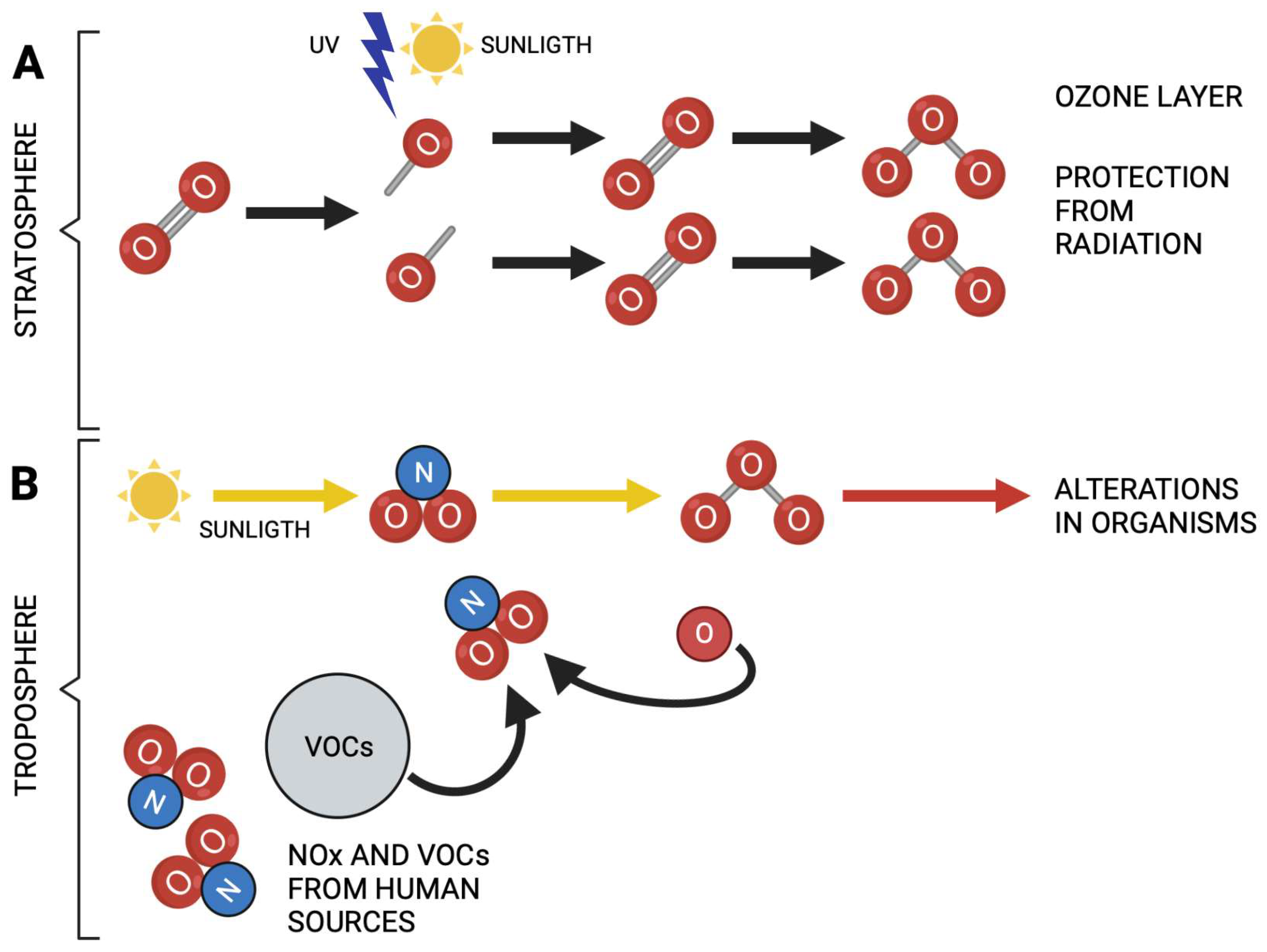

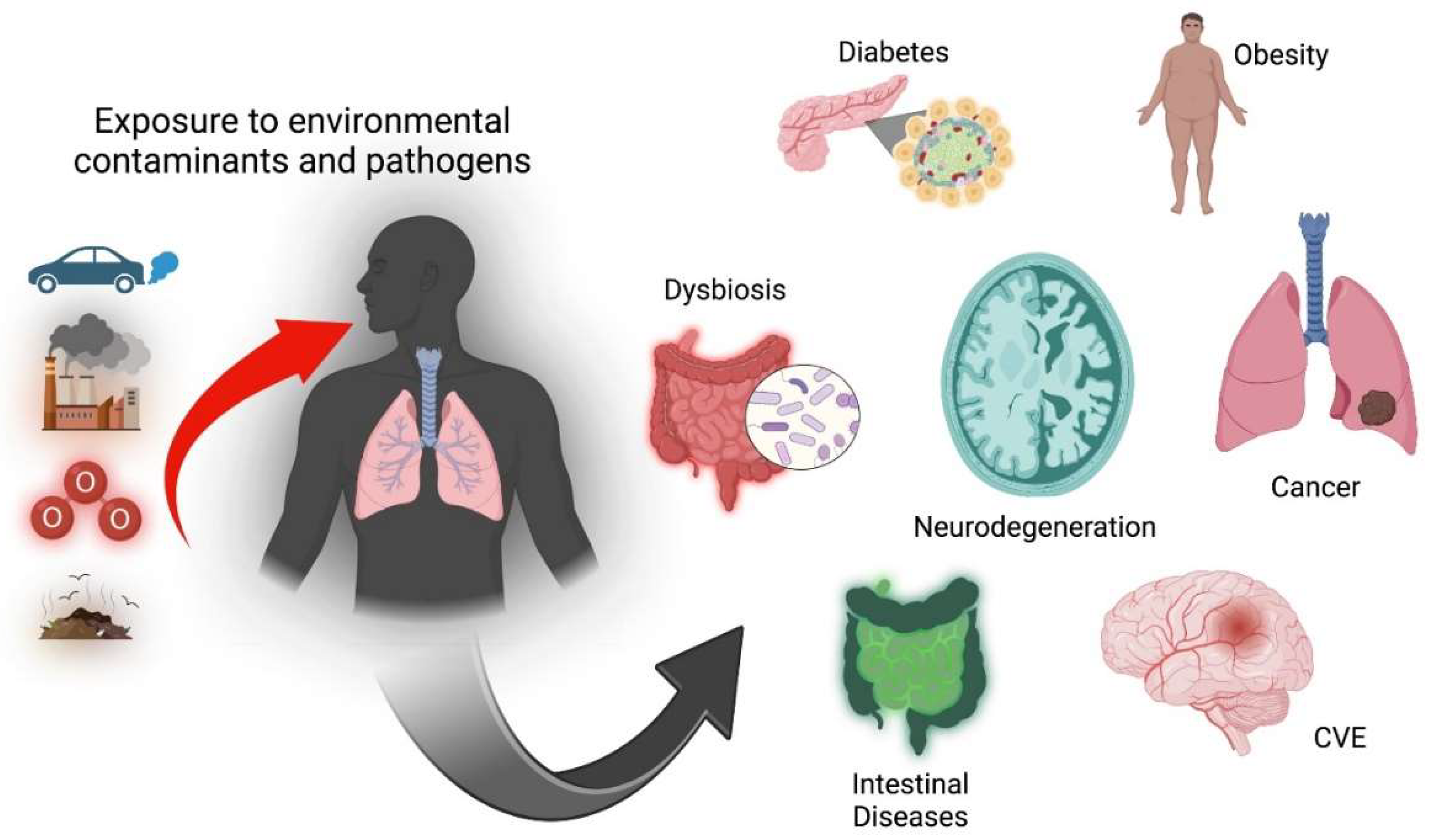

1. Environmental pollution and disease

2. Environmental pollution and intestine

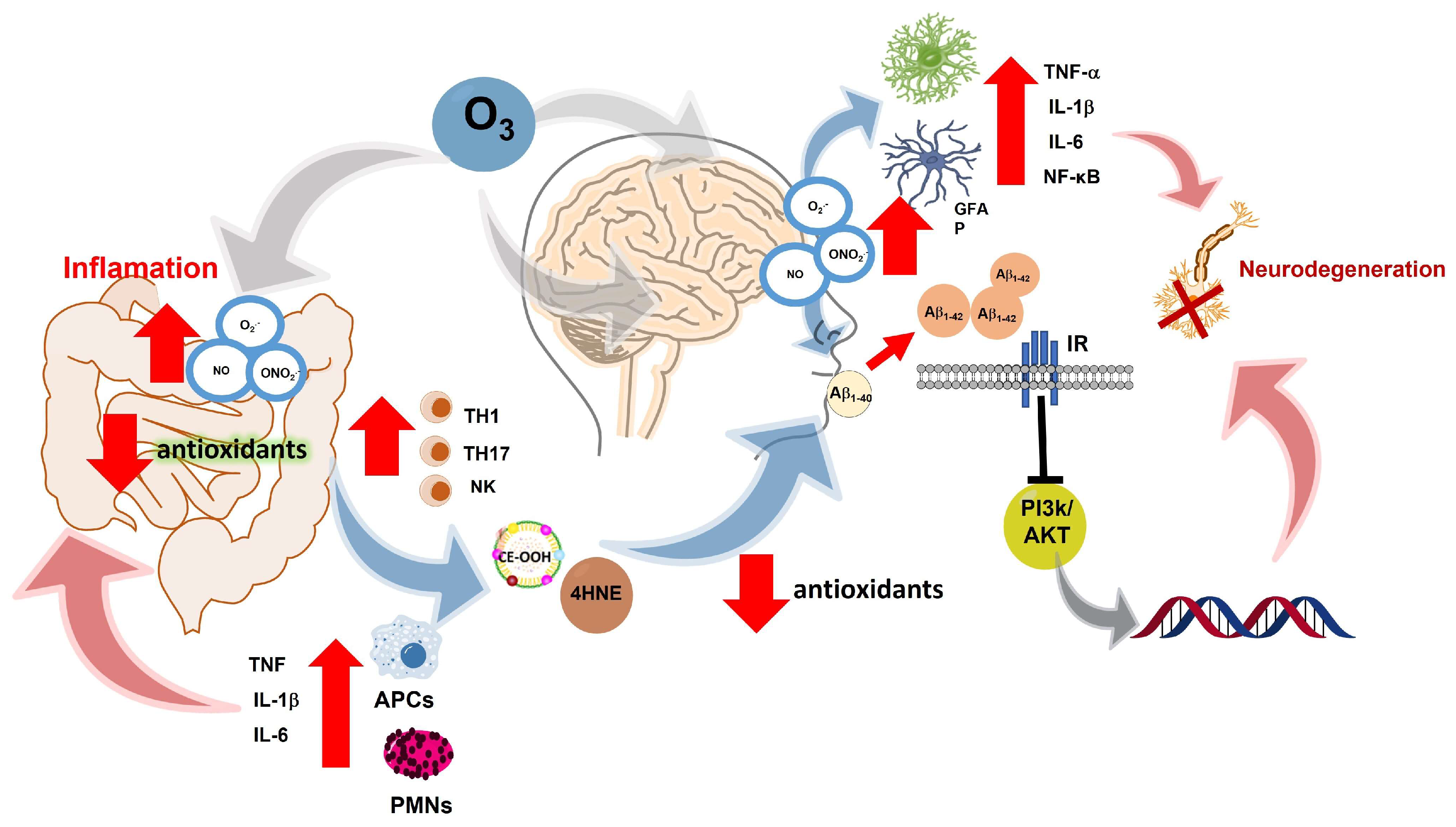

3. Intestinal alterations and neurodegeneration

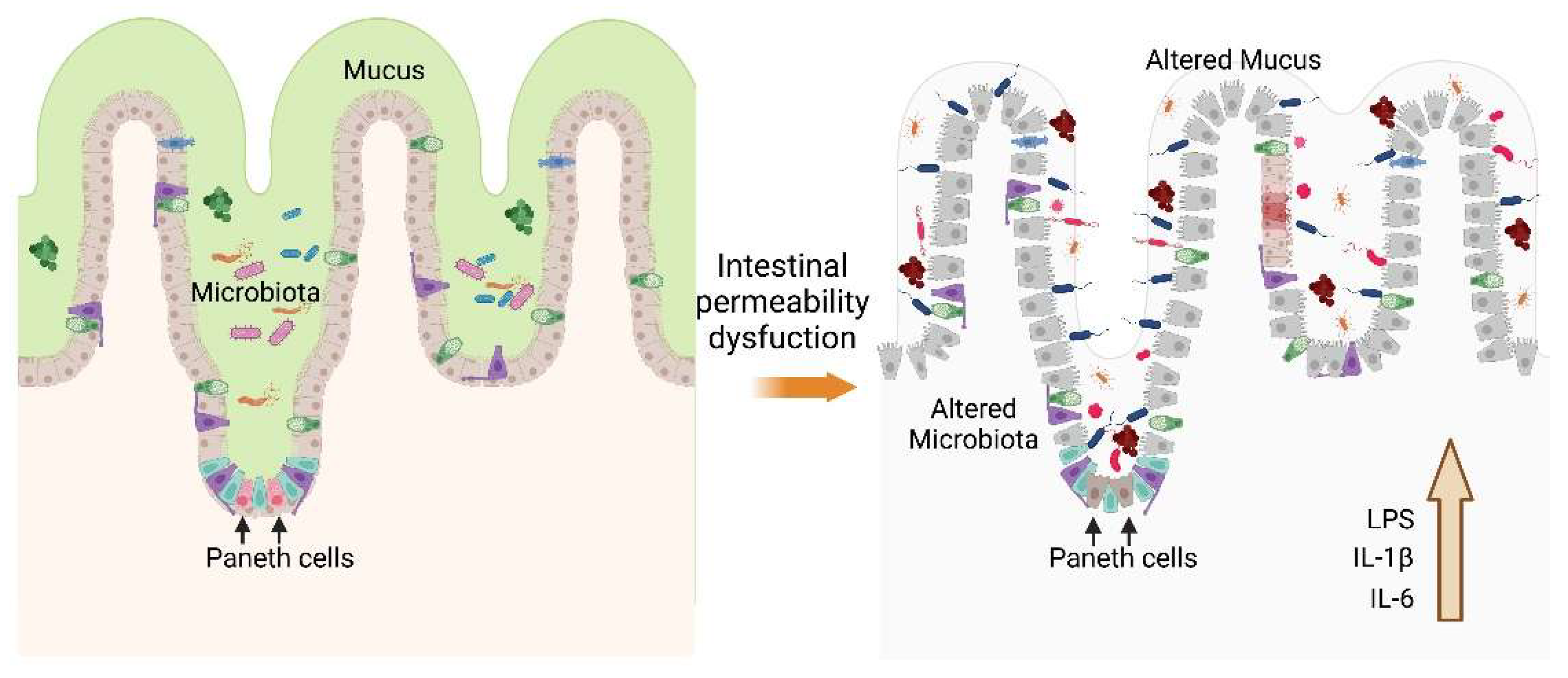

4. Intestinal permeability and neurodegeneration

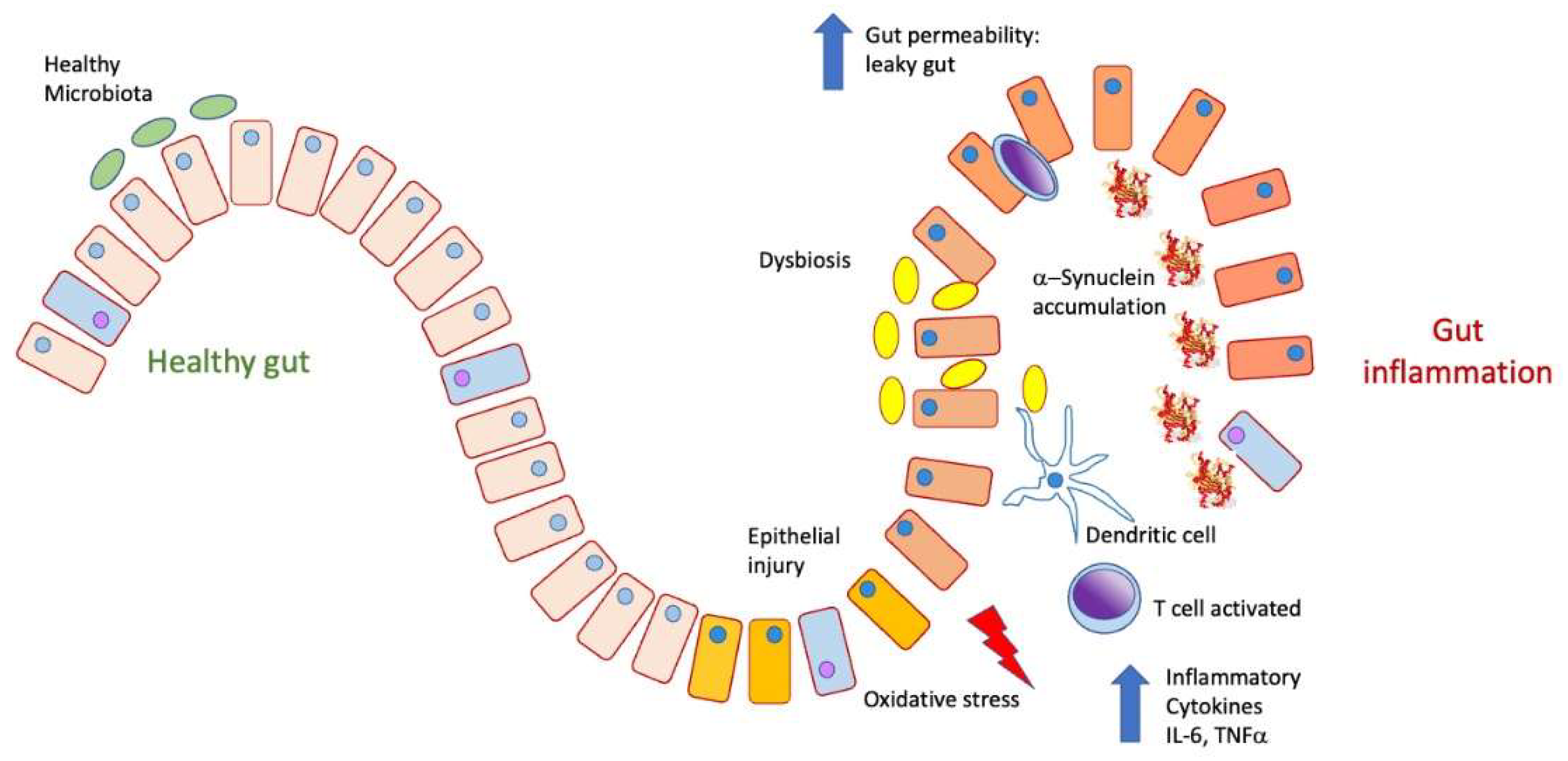

5. Parkinson's disease and intestine

6. Alzheimer's disease and intestine

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for, E. WHO guidelines for indoor air quality: selected pollutants. Copenhagen: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2010 2010.

- Climate change decreases the quality of the air we breathe.

- Orellano, P.; Reynoso, J.; Quaranta, N.; Bardach, A. , Ciapponi, A. Short-term exposure to particulate matter (PM(10) and PM(2.5)), nitrogen dioxide (NO(2)), and ozone (O(3)) and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2020,142:105876. [CrossRef]

- Harishkumar, K.; Yogesh, K. , Gad, I. Forecasting air pollution particulate matter (PM2. 5) using machine learning regression models. Procedia Computer Science. 2020,171:2057-66. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Pan, X.L.; Cui, P.J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.F.; Ren, R.J.; Deng, Y.L.; Xu, W.; Tang, H.D. , Chen, S.D. Association study of the GAB2 gene with the risk of Alzheimer disease in the chinese population. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011,25(3):283-5. [CrossRef]

- de la Salud, O.M. OMS. Convenio Marco de la OMS para el Control del Tabaco Ginebra. 2002, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Sevcsik, E.; Trexler, A.J.; Dunn, J.M. , Rhoades, E. Allostery in a disordered protein: oxidative modifications to α-synuclein act distally to regulate membrane binding. J Am Chem Soc. 2011,133(18):7152-8. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kosaras, B.; Del Signore, S.J.; Cormier, K.; McKee, A.; Ratan, R.R.; Kowall, N.W. , Ryu, H. Modulation of lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial function improves neuropathology in Huntington's disease mice. Acta Neuropathol. 2011,121(4):487-98. [CrossRef]

- Beers, D.R.; Henkel, J.S.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.; Huang, A.; Wen, S.; Liao, B. , Appel, S.H. Endogenous regulatory T lymphocytes ameliorate amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice and correlate with disease progression in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2011,134(Pt 5):1293-314. [CrossRef]

- Floyd, R.A.; Towner, R.A.; He, T.; Hensley, K. , Maples, K.R. Translational research involving oxidative stress and diseases of aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011,51(5):931-41. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbon, G. , Mills, K.H.G. The microbiota and immune-mediated diseases: Opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Eur J Immunol. 2020,50(3):326-37. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, K.E. Ganong fisiología médica (24a: McGraw Hill Mexico; 2013.

- Cheng, L.K.; O'Grady, G.; Du, P.; Egbuji, J.U.; Windsor, J.A. , Pullan, A.J. Gastrointestinal system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010,2(1):65-79.

- Baumgart, D.C. , Dignass, A.U. Intestinal barrier function. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2002,5(6):685-94.

- Thursby, E. , Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017,474(11):1823-36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Wang, N.; Tan, H.Y.; Zhang, Z. , Feng, Y. The Cross-Talk Between Gut Microbiota and Lungs in Common Lung Diseases. Front Microbiol. 2020,11:301. [CrossRef]

- Shreiner, A.B.; Kao, J.Y. , Young, V.B. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015,31(1):69-75. [CrossRef]

- McAleer, J.P. , Kolls, J.K. Contributions of the intestinal microbiome in lung immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2018,48(1):39-49. [CrossRef]

- Raftery, A.L.; Tsantikos, E.; Harris, N.L. , Hibbs, M.L. Links Between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front Immunol. 2020,11:2144. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Cavallero, S.; Hsiai, T. , Li, R. Impact of air pollution on intestinal redox lipidome and microbiome. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020,151:99-110. [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, M.; Fabisiak, A.; Murawska, N.; Wesołowska, E.; Wierzbicka, P.; Wlazłowski, M.; Wójcikowska, M.; Zatorski, H.; Zwolińska, M. , Fichna, J. Current overview of extrinsic and intrinsic factors in etiology and progression of inflammatory bowel diseases. Pharmacol Rep. 2014,66(5):766-75. [CrossRef]

- Pascual, I.P.; Martínez, A.R. , de la Fuente Moral, S. Interacciones entre microbiota y huésped. Medicine-Programa de Formación Médica Continuada Acreditado. 2022,13(49):2843-52.

- Marynowski, M.; Likońska, A.; Zatorski, H. , Fichna, J. Role of environmental pollution in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2015,21(40):11371-8. [CrossRef]

- Vignal, C.; Guilloteau, E.; Gower-Rousseau, C. , Body-Malapel, M. Review article: Epidemiological and animal evidence for the role of air pollution in intestinal diseases. Sci Total Environ. 2021,757:143718. [CrossRef]

- Salvo Romero, E.; Alonso Cotoner, C.; Pardo Camacho, C.; Casado Bedmar, M. , Vicario, M. The intestinal barrier function and its involvement in digestive disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015,107(11):686-96. [CrossRef]

- Ueno, A.; Jijon, H.; Chan, R.; Ford, K.; Hirota, C.; Kaplan, G.G.; Beck, P.L.; Iacucci, M.; Fort Gasia, M.; Barkema, H.W. , et al. Increased prevalence of circulating novel IL-17 secreting Foxp3 expressing CD4+ T cells and defective suppressive function of circulating Foxp3+ regulatory cells support plasticity between Th17 and regulatory T cells in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013,19(12):2522-34. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Kim, S.; Yang, D.H.; Lee, J.; Park, K.W.; Go, J.; Hyun, C.L.; Jee, Y. , Kang, K.S. Mucosal Immunity Related to FOXP3(+) Regulatory T Cells, Th17 Cells and Cytokines in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2018,33(52):e336. [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Joosse, M.E.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.; Dong, Y.; Cai, C.; Song, Z.; Zhang, J.; Brant, S.R.; Lazarev, M. , et al. Deletion of IL-6 Exacerbates Colitis and Induces Systemic Inflammation in IL-10-Deficient Mice. J Crohns Colitis. 2020,14(6):831-40. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.B.; Luo, M.M.; Chen, Z.Y. , He, B.H. The Function and Role of the Th17/Treg Cell Balance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Immunol Res. 2020,2020:8813558.

- Cătană, C.S.; Berindan Neagoe, I.; Cozma, V.; Magdaş, C.; Tăbăran, F. , Dumitraşcu, D.L. Contribution of the IL-17/IL-23 axis to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2015,21(19):5823-30.

- Cadwell, K.; Liu, J.Y.; Brown, S.L.; Miyoshi, H.; Loh, J.; Lennerz, J.K.; Kishi, C.; Kc, W.; Carrero, J.A.; Hunt, S. , et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008,456(7219):259-63. [CrossRef]

- Kaser, A.; Lee, A.H.; Franke, A.; Glickman, J.N.; Zeissig, S.; Tilg, H.; Nieuwenhuis, E.E.; Higgins, D.E.; Schreiber, S.; Glimcher, L.H. , et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008,134(5):743-56. [CrossRef]

- Gubatan, J.; Holman, D.R.; Puntasecca, C.J.; Polevoi, D.; Rubin, S.J. , Rogalla, S. Antimicrobial peptides and the gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2021,27(43):7402-22. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zheng, X.; Liu, S.; Ouyang, H.; Levitt, R.C.; Candiotti, K.A. , Hao, S. TNFα and IL-1β are mediated by both TLR4 and Nod1 pathways in the cultured HAPI cells stimulated by LPS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012,420(4):762-7. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.J.; Oberdörster, G.; Gelein, R. , Finkelstein, J.N. Endotoxin potentiates ozone-induced pulmonary chemokine and inflammatory responses. Exp Lung Res. 2002,28(6):419-33. [CrossRef]

- Mendy, A.; Wilkerson, J.; Salo, P.M.; Weir, C.H.; Feinstein, L.; Zeldin, D.C. , Thorne, P.S. Synergistic Association of House Endotoxin Exposure and Ambient Air Pollution with Asthma Outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019,200(6):712-20. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, B.; Lou, P.; Dai, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhuge, A.; Yuan, Y. , Li, L. The Relationship Between the Gut Microbiome and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurosci Bull. 2021,37(10):1510-22. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Rodriguez, A.B.; Hennessy, E.; Murray, C.L.; Nazmi, A.; Delaney, H.J.; Healy, D.; Fagan, S.G.; Rooney, M.; Stewart, E.; Lewis, A. , et al. Acute systemic inflammation exacerbates neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease: IL-1β drives amplified responses in primed astrocytes and neuronal network dysfunction. Alzheimers Dement. 2021,17(10):1735-55.

- Han, C.; Yang, Y.; Guan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Shen, H.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, W.; Guo, L. , et al. New mechanism of nerve injury in Alzheimer's disease: β-amyloid-induced neuronal pyroptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2020,24(14):8078-90.

- Gardner, L.E.; White, J.D.; Eimerbrink, M.J.; Boehm, G.W. , Chumley, M.J. Imatinib methanesulfonate reduces hyperphosphorylation of tau following repeated peripheral exposure to lipopolysaccharide. Neuroscience. 2016,331:72-7. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Lv, G.; Lee, J.S.; Jung, B.C.; Masuda-Suzukake, M.; Hong, C.S.; Valera, E.; Lee, H.J.; Paik, S.R.; Hasegawa, M. , et al. Exposure to bacterial endotoxin generates a distinct strain of α-synuclein fibril. Sci Rep. 2016,6:30891. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J. , Selkoe, D.J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002,297(5580):353-6.

- Xie, J.; Van Hoecke, L. , Vandenbroucke, R.E. The Impact of Systemic Inflammation on Alzheimer's Disease Pathology. Front Immunol. 2021,12:796867. [CrossRef]

- Segal, Y. , Shoenfeld, Y. Vaccine-induced autoimmunity: the role of molecular mimicry and immune crossreaction. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018,15(6):586-94. [CrossRef]

- Schapira, A.H.V.; Chaudhuri, K.R. , Jenner, P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017,18(7):435-50.

- Luk, K.C.; Song, C.; O'Brien, P.; Stieber, A.; Branch, J.R.; Brunden, K.R.; Trojanowski, J.Q. , Lee, V.M. Exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils seed the formation of Lewy body-like intracellular inclusions in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009,106(47):20051-6. [CrossRef]

- Sacino, A.N.; Brooks, M.; Thomas, M.A.; McKinney, A.B.; Lee, S.; Regenhardt, R.W.; McGarvey, N.H.; Ayers, J.I.; Notterpek, L.; Borchelt, D.R. , et al. Intramuscular injection of α-synuclein induces CNS α-synuclein pathology and a rapid-onset motor phenotype in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014,111(29):10732-7. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Lipke, P. , Klotz, S. Pathogenic microbial amyloids: Their function and the host response. OA Microbiol. 2013,1(1).

- Taylor, J.D.; Zhou, Y.; Salgado, P.S.; Patwardhan, A.; McGuffie, M.; Pape, T.; Grabe, G.; Ashman, E.; Constable, S.C.; Simpson, P.J. , et al. Atomic resolution insights into curli fiber biogenesis. Structure. 2011,19(9):1307-16. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.D. , Matthews, S.J. New insight into the molecular control of bacterial functional amyloids. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015,5:33.

- Miraglia, F. , Colla, E. Microbiome, Parkinson's Disease and Molecular Mimicry. Cells. 2019,8(3). [CrossRef]

- Santiago-López, D.; Bautista-Martínez, J.A.; Reyes-Hernandez, C.I.; Aguilar-Martínez, M. , Rivas-Arancibia, S. Oxidative stress, progressive damage in the substantia nigra and plasma dopamine oxidation, in rats chronically exposed to ozone. Toxicol Lett. 2010,197(3):193-200. [CrossRef]

- Zecca, L.; Zucca, F.A.; Wilms, H. , Sulzer, D. Neuromelanin of the substantia nigra: a neuronal black hole with protective and toxic characteristics. Trends Neurosci. 2003,26(11):578-80. [CrossRef]

- Zucca, F.A.; Segura-Aguilar, J.; Ferrari, E.; Muñoz, P.; Paris, I.; Sulzer, D.; Sarna, T.; Casella, L. , Zecca, L. Interactions of iron, dopamine and neuromelanin pathways in brain aging and Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2017,155:96-119.

- Braak, H.; de Vos, R.A.; Bohl, J. , Del Tredici, K. Gastric alpha-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner's and Auerbach's plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson's disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci Lett. 2006,396(1):67-72.

- Pfeiffer, R.F. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003,2(2):107-16.

- Fasano, A.; Aquino, C.C.; Krauss, J.K.; Honey, C.R. , Bloem, B.R. Axial disability and deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015,11(2):98-110. [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009,9(11):799-809. [CrossRef]

- van, I.S.C.D. , Derkinderen, P. The Intestinal Barrier in Parkinson's Disease: Current State of Knowledge. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019,9(s2):S323-s9.

- Saito, H.; Kanamori, Y.; Takemori, T.; Nariuchi, H.; Kubota, E.; Takahashi-Iwanaga, H.; Iwanaga, T. , Ishikawa, H. Generation of intestinal T cells from progenitors residing in gut cryptopatches. Science. 1998,280(5361):275-8. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M. , von der Weid, P.Y. Lipopolysaccharides modulate intestinal epithelial permeability and inflammation in a species-specific manner. Gut Microbes. 2020,11(3):421-32.

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Nixon, R.A. , Jones, D.T. Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021,7(1):33.

- Rivas-Arancibia, S.; Guevara-Guzmán, R.; López-Vidal, Y.; Rodríguez-Martínez, E.; Zanardo-Gomes, M.; Angoa-Pérez, M. , Raisman-Vozari, R. Oxidative stress caused by ozone exposure induces loss of brain repair in the hippocampus of adult rats. Toxicol Sci. 2010,113(1):187-97.

- Bandyopadhyay, S. Role of Neuron and Glia in Alzheimer's Disease and Associated Vascular Dysfunction. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021,13:653334. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Fernández, R.; Picón-Pagès, P.; Barranco-Almohalla, A.; Crepin, G.; Herrera-Fernández, V.; García-Elías, A.; Fanlo-Ucar, H.; Fernàndez-Busquets, X.; García-Ojalvo, J.; Oliva, B. , et al. Differential regulation of insulin signalling by monomeric and oligomeric amyloid beta-peptide. Brain Commun. 2022,4(5):fcac243. [CrossRef]

- Leino, R.L.; Gerhart, D.Z.; van Bueren, A.M.; McCall, A.L. , Drewes, L.R. Ultrastructural localization of GLUT 1 and GLUT 3 glucose transporters in rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 1997,49(5):617-26.

- Croze, M.L. , Zimmer, L. Ozone Atmospheric Pollution and Alzheimer's Disease: From Epidemiological Facts to Molecular Mechanisms. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018,62(2):503-22.

- Corradi, M.; Alinovi, R.; Goldoni, M.; Vettori, M.; Folesani, G.; Mozzoni, P.; Cavazzini, S.; Bergamaschi, E.; Rossi, L. , Mutti, A. Biomarkers of oxidative stress after controlled human exposure to ozone. Toxicol Lett. 2002,134(1-3):219-25. [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Arancibia, S.; Vazquez-Sandoval, R.; Gonzalez-Kladiano, D.; Schneider-Rivas, S. , Lechuga-Guerrero, A. Effects of ozone exposure in rats on memory and levels of brain and pulmonary superoxide dismutase. Environ Res. 1998,76(1):33-9. [CrossRef]

- Nery-Flores, S.D.; Ramírez-Herrera, M.A.; Mendoza-Magaña, M.L.; Romero-Prado, M.M.J.; Ramírez-Vázquez, J.J.; Bañuelos-Pineda, J.; Espinoza-Gutiérrez, H.A.; Ramírez-Mendoza, A.A. , Tostado, M.C. Dietary Curcumin Prevented Astrocytosis, Microgliosis, and Apoptosis Caused by Acute and Chronic Exposure to Ozone. Molecules. 2019,24(15). [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Zimbrón, L.F. , Rivas-Arancibia, S. Oxidative stress caused by ozone exposure induces β-amyloid 1-42 overproduction and mitochondrial accumulation by activating the amyloidogenic pathway. Neuroscience. 2015,304:340-8. [CrossRef]

- Pocernich, C.B.; Lange, M.L.; Sultana, R. , Butterfield, D.A. Nutritional approaches to modulate oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011,8(5):452-69.

- He, Y.; Ruganzu, J.B.; Jin, H.; Peng, X.; Ji, S.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, L. , Yang, W. LRP1 knockdown aggravates Aβ(1-42)-stimulated microglial and astrocytic neuroinflammatory responses by modulating TLR4/NF-κB/MAPKs signaling pathways. Exp Cell Res. 2020,394(2):112166.

- Kamphuis, W.; Middeldorp, J.; Kooijman, L.; Sluijs, J.A.; Kooi, E.J.; Moeton, M.; Freriks, M.; Mizee, M.R. , Hol, E.M. Glial fibrillary acidic protein isoform expression in plaque related astrogliosis in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014,35(3):492-510.

- Jung, K.K.; Lee, H.S.; Cho, J.Y.; Shin, W.C.; Rhee, M.H.; Kim, T.G.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Hong, S. , Kang, S.Y. Inhibitory effect of curcumin on nitric oxide production from lipopolysaccharide-activated primary microglia. Life Sci. 2006,79(21):2022-31. [CrossRef]

- Reichert, C.O.; Levy, D. , Bydlowski, S.P. Paraoxonase Role in Human Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020,10(1). [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, G.; Bacchetti, T.; Moroni, C.; Savino, S.; Liuzzi, A.; Balzola, F. , Bicchiega, V. Paraoxonase activity in high-density lipoproteins: a comparison between healthy and obese females. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005,90(3):1728-33. [CrossRef]

- Levy, E.; Trudel, K.; Bendayan, M.; Seidman, E.; Delvin, E.; Elchebly, M.; Lavoie, J.C.; Precourt, L.P.; Amre, D. , Sinnett, D. Biological role, protein expression, subcellular localization, and oxidative stress response of paraoxonase 2 in the intestine of humans and rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007,293(6):G1252-61. [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.; Gevezova, M.; Sarafian, V. , Maes, M. Redox regulation of the immune response. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022,19(10):1079-101. [CrossRef]

- Remigante, A. , Morabito, R. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms in Oxidative Stress-Related Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022,23(14).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).