1. Background

Pursuing the global commitment in fighting HIV, viral hepatitis and tuberculosis (TB), has led to a partnership between international institutions and over 400 cities worldwide signing the Paris Declaration on Fast Track Cities in 2014. The Paris Declaration recognizes the urgency of these public health issues and sets goals for cities to accelerate their response to them [

1].

Lombardy and Brescia have one of the highest incidence of HIV and HCV in Italy [

2,

3], highlighting the need for increased efforts to address these epidemics. Becoming a Fast-Track City in 2020 demonstrates the city’s commitment to address the issue and work towards achieving the fast-track goals.

The European Testing Week is a significant step towards achieving the fast-track goals [

4] and this. The initiatives aim to offer Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) for HIV and for viral hepatitis C (HCV) to the general population and to promote awareness on the benefits of the earlier HIV and hepatitis testing. Since 2013, the World Health Organization European region is encouraged to participate in this initiative throughout local networks including community-based sites, healthcare facilities and public health institutions

VCT is considered as one of the most cost-effective public health interventions for screening, and through the pre- and post- counseling sessions provides an opportunity to understand personal risk of infections, encourage healthy behaviors, increase awareness of personal serostatus, prevent transmission, improve access to medical care when needed and fight discrimination [

5].

Evaluating the general population knowledge and awareness of HIV and HCV is crucial in developing targeted and effective strategies to address these epidemics. This knowledge can help tailor interventions to different population strata, such as young people and adults, and increase the impact of prevention and care efforts. Here we report the results of an individual questionnaire regarding HIV and HCV awareness and knowledge, which was offered to participants during the VCT session.

2. Methods

This cross-sectional study was based on a self-administered questionnaire and conducted during the European Testing Week in May 2022 and the World AIDS Day on the 1st of December 2022.

In 2022, the Infectious and Tropical Diseases Department of the ASST Spedali Civili of Brescia and University of Brescia, together with Brescia Municipality, non-governmental organizations, and civil societies, implemented four days dedicated to offer voluntary counseling sessions and a rapid anonymous screening test for HIV and HCV to the general population in Brescia. Specialized health staff (infectious disease medical doctors and nurses) and a mobile unit reached the designated points of the city to offer the promotion and screening service.

2.1. Population

Three different city’s areas were selected to achieve different strata of population: the university district (Area A) with the aim to reach students, two different suburban city areas for reaching the working-aged adults (Area B), and the city center (Area C) for the general public.

2.2. Questionnaire

An anonymous self-completion multiple-choice questionnaire was offered to everyone who performed the screening test or requested a counseling session (

Table 1).

The questionnaire included 19 questions: four regarding the demographic characteristics such as sex, age, education, and sexual behavior (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4), 11 regarding the knowledge, attitudes, and perception about HIV (Q5, Q6, Q7, Q8, Q9, Q10, Q11, Q12, Q13, Q14, Q15) and four questions about knowledge, attitudes and perception about HCV (Q16, Q17, Q18, Q19).

Table 1.

Self-Completion Multiple-Choice Questionnaire.

Table 1.

Self-Completion Multiple-Choice Questionnaire.

| Sex (Q1) |

F |

M |

Other |

|

|

|

| Age (Q2) |

18-25y |

25-30y |

30-40y |

40-50y |

50-60y |

>60y |

| Educational level (Q3) |

Primary School Diploma |

Middle School Diploma |

High School Diploma |

High School Student |

University Student |

University Diploma |

| Sexual Orientation (Q4) |

Heterosexual |

Homosexual |

Bisexual |

Fluid |

Other |

|

| HIV |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Did you already perform an HIV test? (Q5) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

| Do you know where to perform the HIV test in your city? (Q6) |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

| Do you know people with HIV? (Q7) |

Yes, my partner |

Yes, a relative |

No |

|

|

|

| How HIV can be transmitted (Q8) *more than one correct answers |

sharing cutlery |

mosquito bites |

infected blood |

saliva |

unprotected sex |

pregnancy |

| An HIV-positive mom, regularly taking antiretroviral therapy can transmit the HIV virus during pregnancy: (Q9) |

Yes, in 90% of cases |

Yes, in 50% of cases |

In less than 1% of cases |

|

|

|

| With the current drug therapies, the HIV-positive people could have a quality of life similar to HIV-negative people (Q10) |

Yes |

No |

I don’t know |

|

|

|

| Nowadays there is a vaccine that prevents HIV (Q11) |

Yes |

No |

I don’t know |

|

|

|

| Do you know what’s the PreP? (Q12) |

Yes |

No |

I don’t know |

|

|

|

| The HIV-positive people, regularly taking antiretroviral therapy and having "viremia 0" can transmit the HIV virus (Q13) |

Yes |

No |

I don’t know |

|

|

|

| Do you know the meaning of "Undetectable"? (Q14) |

Yes |

No |

I don’t know |

|

|

|

| Do you agree to live with HIV-positive people? (Q15) |

Yes |

No |

I don’t know |

|

|

|

| HCV |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HCV virus can be transmitted through *more than one correct answers (Q16) |

mosquito bites |

by air (cough or sneeze) |

unprotected sex |

infected blood |

during the pregnancy |

|

| There is a vaccine that prevents HCV (Q17) |

Yes |

No |

I don’t know |

|

|

|

| The current therapies are able to treat the infection and eliminate the hepatitis virus HCV (Q18) |

Yes |

No |

I don’t know |

|

|

|

| Did you already perform an HCV test? (Q19) |

Yes |

No |

I don’t know |

|

|

|

2.3. Analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed on the demographic characteristics of the population and on the knowledge and attitudes with respect to the two diseases covered by the questionnaire.

Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and analyzed by contingency tables followed by the Fisher exact test with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) calculation. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 statistical package.

In order to get a more detailed picture of the respondents, we evaluated two categorized variables: age and sexual orientation. Consequently, results were analyzed for four different groups of respondents: people aged 18-40; people over 40 years old; heterosexual and LGBTQI+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer).

We conducted an analysis to assess the level of knowledge in different population groups with regards to HIV and HCV together. We evaluated four common questions related to both the infections and regarding the way of transmission (Q8, Q16), the vaccine (Q11, Q17), the therapies (Q10, Q18) and the tests (Q5, Q19). Based on the respondents’ answers, we categorized their knowledge levels as either high or low for both viruses together. Specifically, people who answered three or four of the four questions correctly for each of the two infections were classified as having a high level of knowledge, and those who answered two or fewer questions correctly for each virus were classified as having a low level of knowledge. Additionally, we identified a subgroup of participants with "uneven knowledge", those who had discordant knowledge levels between HIV and HCV.

Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and analyzed by contingency tables followed by the Fisher exact test with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) calculation. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 statistical package.

3. Results

We offered 333 people to complete the questionnaire before taking the screening test and counseling sessions. All people accepted and submitted the completed questionnaire, 123 (37%) from area-A, 105 (31.5%) from Area-B and 105 (31.5%) from Area-C. Overall, gender was balanced with 171 (51%) of females. About half of respondents (n=170; 51%) were aged between 18 and 25 years old, while 29 (8.7%) were aged over 60 years old.

More than half of the respondents (n=207; 62%) were university students or graduated from university, while 92 (27.6%) have a high school diploma or were still attending high school. In the group with the people aged <40 years old 257 (n=247; 96.1%) had the higher educational levels as high school student or high school diploma and university student and graduated. Regarding sexual behaviors, the vast majority of respondents (n=264; 79%) declared to be heterosexual, 63 (18.9%) declared to be homosexual or bisexual or fluid or other sexual orientation, and 6 (1.8%) respondents preferred not to declare it. All the population characteristics are shown in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics. n = number, %=percentage.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics. n = number, %=percentage.

| |

Overall |

<40 yo |

>40 yo |

Heterosexual |

LGBTQI+ |

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| |

TOT |

333 |

100,0 |

257 |

77,2 |

76 |

22,8 |

264 |

79,3 |

63 |

18.9 |

| Sex (Q1) |

F |

171 |

51,4 |

145 |

43,5 |

26 |

7,8 |

142 |

42,6 |

28 |

8,4 |

| M |

159 |

47,7 |

111 |

33,3 |

48 |

14,4 |

120 |

36,0 |

34 |

10.2 |

| other |

3 |

0.9 |

1 |

0.3 |

2 |

0.6 |

2 |

0.6 |

1 |

0,3 |

| Age (Q2) |

18-25y |

170 |

51,1 |

170 |

51,0 |

- |

- |

136 |

40,8 |

34 |

10,2 |

| 25-30y |

57 |

17,1 |

57 |

17,1 |

- |

- |

43 |

12,9 |

13 |

3,9 |

| 30-40y |

30 |

9,0 |

30 |

9,0 |

- |

- |

21 |

6,3 |

8 |

2,4 |

| 40-50y |

19 |

5,7 |

- |

- |

19 |

5,7 |

17 |

5,1 |

0 |

0,0 |

| 50-60y |

28 |

8,4 |

- |

- |

28 |

8,4 |

23 |

6,9 |

5 |

1,5 |

| >60y |

29 |

8,7 |

- |

- |

29 |

8,7 |

24 |

7,2 |

3 |

0,9 |

| Educational level (Q3) |

Primary School Diploma |

5 |

1,5 |

1 |

0,3 |

4 |

1,2 |

2 |

0,6 |

1 |

0,3 |

| Middle School Diploma |

27 |

8,1 |

7 |

2,1 |

20 |

6,0 |

22 |

6,6 |

3 |

0,9 |

| High School Diploma |

58 |

17,4 |

32 |

9,6 |

26 |

7,8 |

51 |

15,3 |

7 |

2,1 |

| High School Student |

34 |

10,2 |

28 |

8,4 |

6 |

1,8 |

22 |

6,6 |

11 |

3,3 |

| University Student |

139 |

41,7 |

137 |

41,1 |

2 |

0,6 |

112 |

33,6 |

27 |

8,1 |

| University Diploma |

68 |

20,4 |

50 |

15,0 |

18 |

5,4 |

53 |

15,9 |

14 |

4,2 |

| NA |

2 |

0,6 |

2 |

0,6 |

0 |

0,0 |

2 |

0,6 |

0 |

0,0 |

| Sexual Orientation (Q4) |

Heterosexual |

264 |

79,3 |

200 |

60,1 |

64 |

19,2 |

264 |

79,3 |

- |

- |

| Homosexual |

18 |

5,4 |

16 |

4,8 |

2 |

0,6 |

- |

- |

18 |

5,4 |

| Bisexual |

35 |

10,5 |

32 |

9,6 |

3 |

0,9 |

- |

- |

35 |

10,5 |

| Fluid |

4 |

1,2 |

4 |

1,2 |

0 |

0,0 |

- |

- |

4 |

1,2 |

| Other |

6 |

1,8 |

3 |

0,9 |

3 |

0,9 |

- |

- |

6 |

1,8 |

| NA |

6 |

1,8 |

2 |

0,6 |

4 |

1,2 |

6 |

1,8 |

- |

- |

3.1. HIV knowledge and attitudes

More than half of the respondents (55%; 183) never performed an HIV test. Overall, 170 (51%) subjects knew where to perform it if necessary: of these 38 (60%) were identified as LGBTQI+ people and 130 (49.2%) as heterosexuals.

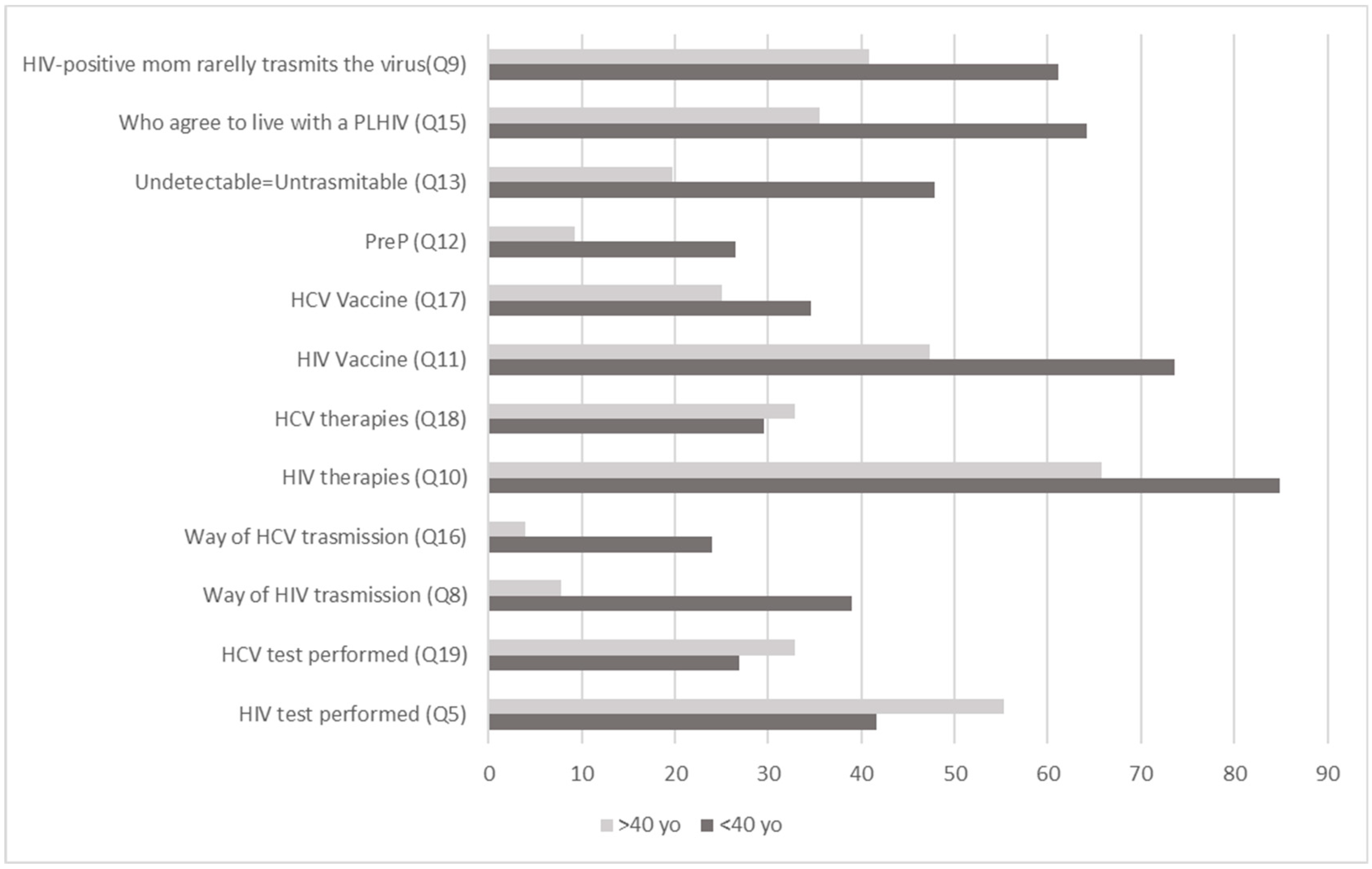

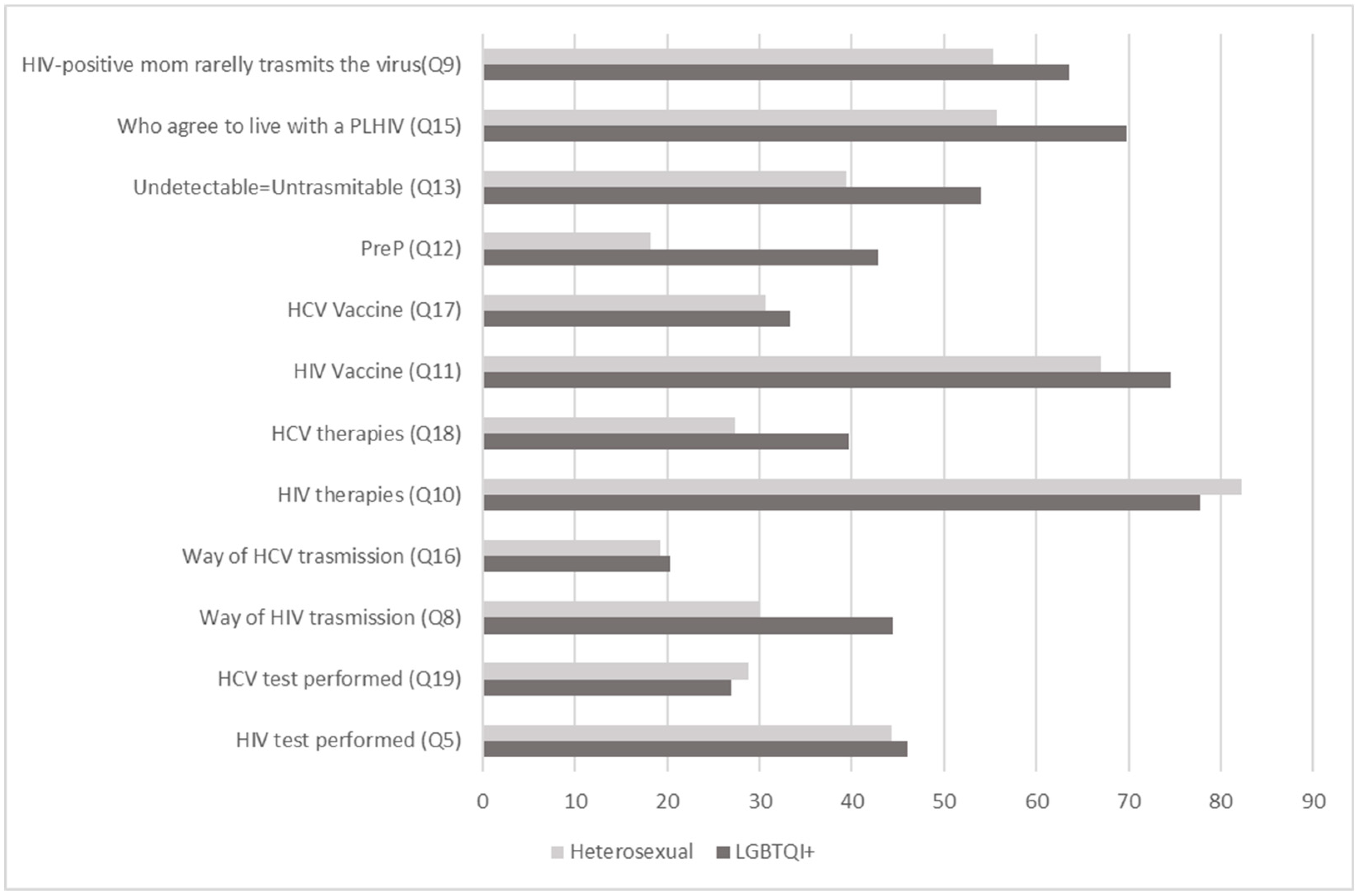

Overall, only 107 (32%) of respondents knew how HIV is transmitted (Q8). Major differences were shown between different age groups, where people under the age of 40 had a significantly higher correct response rate than people over 40 (n= 101; 39% versus n=6; 7.8%, p<0.00001). Similarly, almost half of LGBTQI+ people (n=28; 44.4%) gave the correct answer, versus 30% (n=79) of heterosexuals (p=0.0359). In particular, over half (n=188; 56.5%) of respondents were aware that the risk of transmitting HIV to a newborn by a pregnant woman adhering to therapy is less than 1% (Q9). Here again, people under 40 years of age showed a significantly higher response rate versus people over 40 years old (n=157; 61% vs n=31; 40%; p=0.0023), as well as LGBTQI+ people who had a higher response rate versus heterosexuals (n=40; 63.5% vs n=146; 55%, NS). Moreover, only 15 (19.7%) of those aged over 40 were aware that undetectable=untransmittable (Q13), while 123 (48%) of people under 40 years old gave the correct answer (p<0.00001). Significant differences are also shown between LGBTQI+ and heterosexuals (n=34; 54% and n=104; 39%, respectively, p=0.0464).

Overall, 268 (80.5%) of respondents knew that people living with HIV who regularly take antiretroviral therapy have a similar life expectancy to people living without HIV(Q10). While 218 (85%) people under 40 knew about it, only 50 (66%) of those over 40 gave the correct answer (p=0.0137). Both heterosexual and LGBTQI+ people showed a similar level of knowledge (n=217; 82% and n=49; 78% respectively).

Two thirds of respondents (n=225; 67.5%) knew that there is still no vaccine that can prevent HIV infection (Q11). People over 40 are the group that showed the biggest gaps on this issue, where only 36 (47%) gave the correct answer, versus 189 (74%) of people under 40 (p<0.001).

Only 75 (22.5%) of respondents had ever heard about PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) (Q12), with LGBTQI+ people showing better awareness than heterosexual individual (n=27; 43% versus n=48; 18%, p<0.0001). A limited awareness has been assessed among both under and over 40 years of age groups (26.5%, n=68 vs 9.2%, n=7, respectively).

About half of respondents (57.6%; 192) said they would cohabit with a person living with HIV (Q15). The major rejection has been found among the over 40 years of age population (n=27, 35.5% vs n=165, 64% in people under 40 years of age, p<0.001).

3.2. Hepatitis C Virus knowledge

More than half of the respondents (187; 56%) never performed an HCV test (Q19). No major differences can be observed between populations, where only 25 (33%) and 69 (27%) of the over and under 40 years of age population respectively declared to have ever been tested for HCV.

Overall, only 66 (20%) of respondents knew how HCV is transmitted (Q16). No major differences were shown between LGBTQI+ and heterosexuals, where 15 (23.3%) and 51 (19%) of them gave the correct answer respectively. People under 40 had a higher correct response rate than older ones (n=62; 24% versus n=3; 3.9%).

About the HCV vaccine knowledge the trend was similar in all the groups. Overall, 32.4% (n=108) of the subjects knew that there is still no vaccine that can prevent HCV infection (Q17). The participants responded similarly about the current antiviral therapies (Q18): 29.4% (n=98) were aware that it is possible to heal the HCV infection by eliminating the virus. In this topic, the better result was for the LGBTQI+ group where 40% (n=25) of respondents gave the correct answers.

Figure 1.

Percentages (%) of correct answers between age groups.

Figure 1.

Percentages (%) of correct answers between age groups.

Q5, Q19, Q8, Q16, Q10, Q18, Q11, Q17, Q12, Q13, Q15, Q9: questions 5, 19, 8, 16, 10, 18, 11, 17, 12, 13, 15, 9 of the questionnaire. <40 yo: age group under 40 years old; >40 oy: age group over 40 years old; PLHIV: people with HIV

Figure 2.

Percentages (%) of correct answers between sexual orientation groups.

Figure 2.

Percentages (%) of correct answers between sexual orientation groups.

Q5, Q19, Q8, Q16, Q10, Q18, Q11, Q17, Q12, Q13, Q15, Q9: questions 5, 19, 8, 16, 10, 18, 11, 17, 12, 13, 15, 9 of the questionnaire. PLHIV: people with HIV

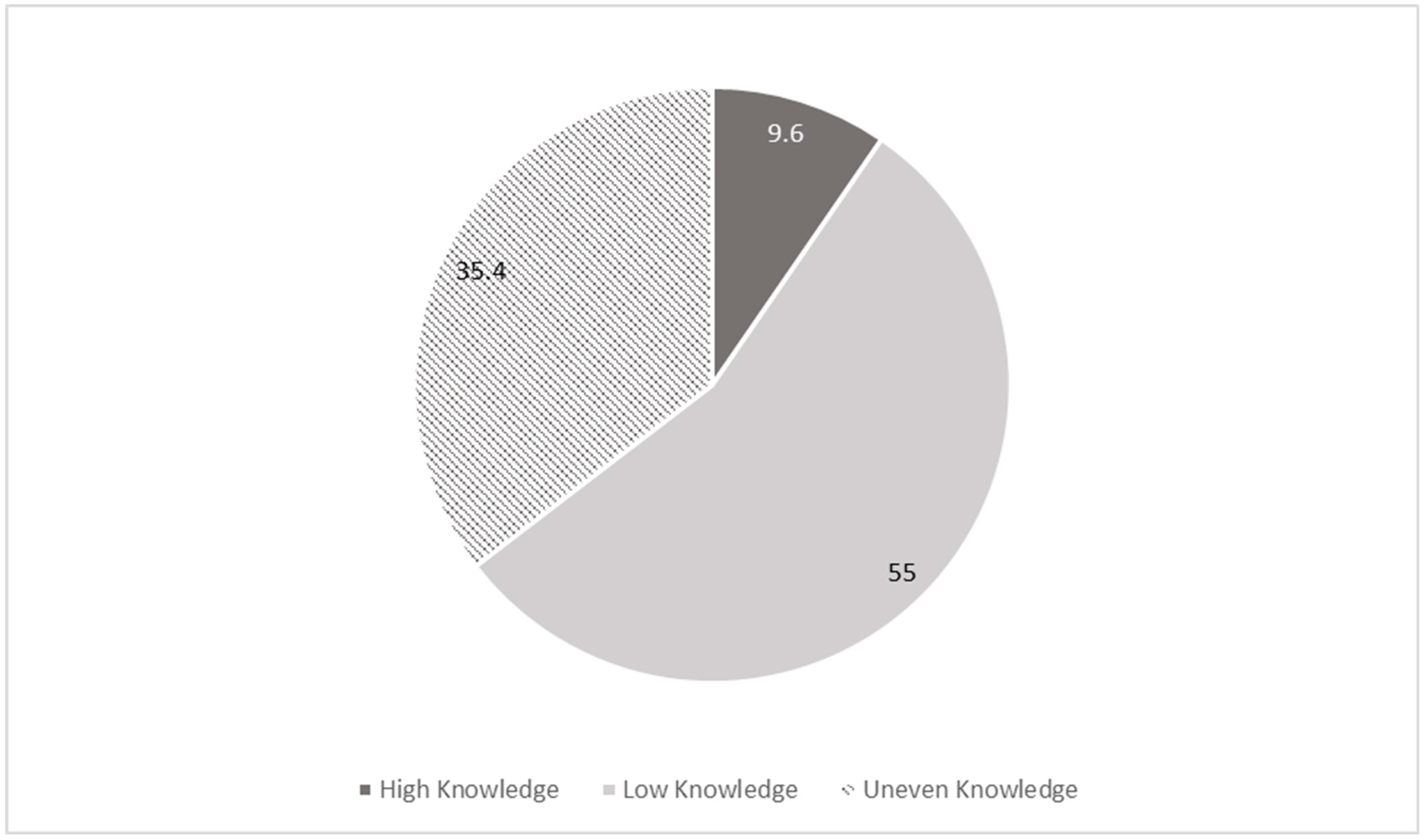

3.3. Comparing HIV and HCV Knowledge

Overall, by comparing the responses to the same four questions for HIV and HCV (Q5, Q8, Q10, Q11 and Q19, Q16, Q17, Q18), we evidenced a higher proportion of individuals who achieved 100% scores (high knowledge level) on HIV questions compared to HCV (n=56 out of 330; 16.8% vs n=11 out of 330; 3.3%). Additionally, for those who scored 75% (medium knowledge level), there is a significant difference with 27% (90 out of 330) and 7.8% (26 out of 330) correct answers for HIV and HCV, respectively.

Evaluating the knowledge about both infections together, it’s possible to notice that there is a wide discrepancy between the subgroup with the score of right answers between high knowledge and the people with low knowledge. In particular, people with high scores for HIV and HCV together represent only 9.6% (32 of 333) of the overall population (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of knowledge on HIV and HCV. Percentage (%).

Figure 3.

Distribution of knowledge on HIV and HCV. Percentage (%).

High knowledge: who achieved 3 or 4 (out of 4) in both the virus.

Low knowledge: who achieved 0, 1 or 2 (out of 4) in both the virus.

Uneven knowledge: who achieved discordant knowledge between HIV and HCV

Evaluated questions: (Q5, Q8, Q10, Q11 and Q19, Q16, Q17, Q18).

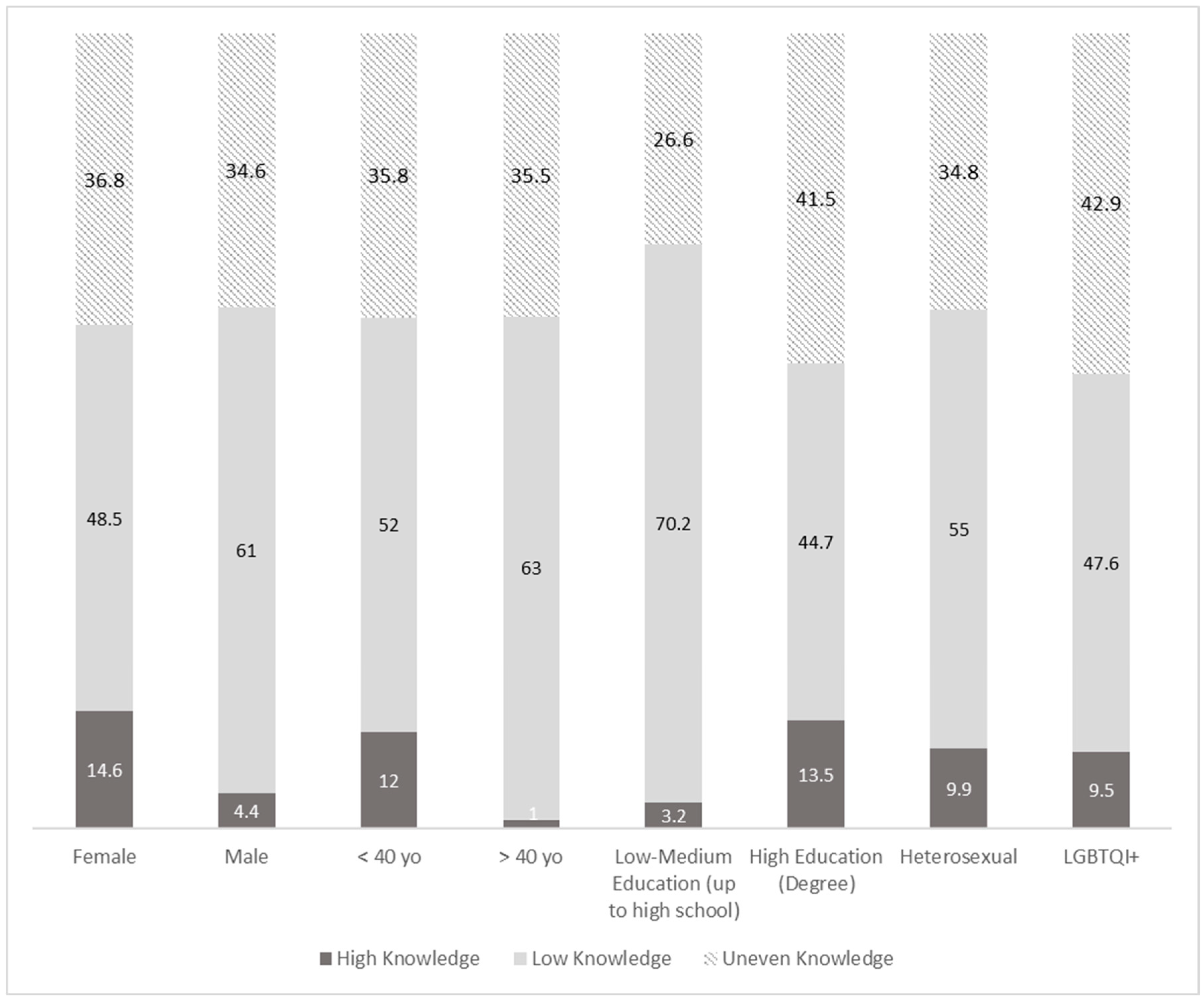

We analyzed the sub-population according to their level of knowledge on both HIV and HCV. We evidenced that 14.6% (25 of 171) of women and only 4.4% (7 of 159) of men have high knowledge levels. Regarding the age we evidenced that 12.2% (31 of 257) of people under 40 have high knowledge levels compared to the older group with only 1.3% (1 of 76). Considering the educational level the group with high education has higher prevalence of high knowledge (13.5%, 28 out of 207) compared to the group with low education 3.2% (4 out of 124).

Also evaluating low knowledge level, 48.5% (83 of 171) of women and 61.0% (97 of 159) of men have low knowledge levels for both viruses together. Regarding the age, 52.1% (134 of 257) of people under 40 have high knowledge levels compared with the older group with only 63.2% (48 of 76). Considering the educational level the group with high education has lower prevalence of low knowledge (44.7% 93 out of 207) compared to the group with low-medium education 70.2% (87 out of 124). (

Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Distribution of knowledge levels on HIV and HCV together. Percentage (%).

Figure 4.

Distribution of knowledge levels on HIV and HCV together. Percentage (%).

High knowledge: who achieved 3 or 4 (out of 4) in both the virus.

Low knowledge: who achieved 0, 1 or 2 (out of 4) in both the virus.

Uneven knowledge: who achieved discordant knowledge between HIV and HCV

F: female, M: male; <40 yo: under 40 years old, >40 yo: over 40 years old.

4. Discussion

Public awareness of infectious diseases plays an essential role in disease control, as shown during COVID- 19 pandemic [

6], and the scarce or lack of knowledge about infectious diseases leads to low detection rates, treatment interruptions, discrimination, and stigma. Furthermore, a high level of knowledge of infectious diseases could not only help the general population protect themselves, but also promote screening in risk groups, stimulate suspected infected patients to seek early medical care and more comprehensive care. We conducted this survey to provide an overall picture in our city about the public awareness of infectious diseases that WHO have planned to end epidemic by 2030 as HIV and HCV.

The main results of our study reflect that, in general, almost 70% of those interviewed had null or very low level of knowledge about HCV and almost 30% about HIV infection with important differences according to age, sexual behaviors and education. Older respondents and those with a low educational level had lower levels of knowledge of all aspects of these two infectious diseases. In addition, just under half of the participants have ever tested for HIV and/or HCV infections. In Naples, South-Italy, a small study (244 participants attending HIV counseling and testing service) was conducted before 2010 about knowledge and attitudes regarding HIV infection. Only 25% of responders correctly identified HIV modes of transmission and only 21% had received previous HIV [

7]. Our study shows as after more than 10 years there are still huge gaps in this topic in Italy.

The knowledge regarding the ways of HIV transmission appeared to be quite variable in our overall study population, with better results in the younger group. Similar results were found in studies conducted in Jordan, China and Saud Arabia [

8,

9,

10]. This group appears to be also more aware about the efficacy of HIV drug therapy and the life expectancy for the PLWH.

Notwithstanding, our study reveals an uneven level of awareness regarding the notion of undetectable=untransmittable, with greater knowledge observed among the LGBTQI+ and younger age cohorts. A recent Italian survey among university students revealed that only 3 out of 10 interviewed were knowledgeable that in Italy new cases of HIV infection are mainly attributable to heterosexual [

11]. LGBTQI+ have usually more information about HIV infection and the wrong notion that HIV is a health problem mainly of this group could generate the mistaken self-perception of a low risk of HIV infection among heterosexual people.

About the PrEP, we evidenced a poor knowledge in all the considered groups, with slightly better scores in the LGBTQI+ group. The less informed appeared to be the older group. These data are consistent with similar studies conducted in the United States [

12] and Italy [

13]. Preventive measures including health information and preventive strategies must be implemented in our area.

Poor HIV-related knowledge has been strictly linked with stigmatizing attitudes [

9,

14]. Similarly, we observed a persistent prevalence of stigma mainly among the older population, as evidenced by the reluctance to cohabit with individuals living with HIV. Again, here we showed how people over the age of 40 are influenced by old information, when HIV was a highly stigmatized and deadly disease.

In a former European study, higher knowledge levels of HIV infection have been linked to younger age groups, and higher levels of education, implying that educational initiatives could positively influence the level of knowledge regarding these diseases [

15]. Our results suggest the need to implement health educational campaigns for the older population with targeted and effective strategies tailored to different population strata, as already stated in previous studies [

9], with information on the mode of transmission of the disease and to develop a series of policies and measures to fight against HIV stigmatization. This is relevant also if we consider that in Italy the median age of the diagnosis of HIV infection is 41 years, with an increasing prevalence of late presenters [

2].

The knowledge levels of HCV infection have previously been evaluated in various countries with discordant results. Surveys in Ethiopia (Healthcare workers of a University Medical Center), and Egypt (clinically diagnosed HCV patients) showed a medium-high level knowledge of HCV infection (60.9% and 49% respectively) [

16,

17]. In Saudi Arabia, a country with 1.1% of HCV seroprevalence, the 53% of participants to one survey (general population) had low knowledge with a low HCV testing rate (17.8%) [

18]. In our study only 11% of participants had medium/high level of HCV knowledge

Another important result is obtained by comparing the knowledge of HIV and HCV. A previous study among health workers in Malawi showed that knowledge on HCV was lower when compared with HIV/AIDS [

19]. In our study, knowledge about HIV is also wider than knowledge about HCV, although HIV prevalence is estimated to be lower [

20]. In particular, the population with medium-high scores is mostly women, aged less than 40 years and almost all were university students or graduates. On the other hand, regarding the broader segment of the population who have low or insufficient knowledge, the population is equally distributed between males and females; in this group 70% are under the age of 40 while half of them are university students or graduates.

Several studies have reported inadequate knowledge regarding HCV transmission. This phenomenon may be partially explained by the lower prevalence of HCV infection in certain countries [

21,

22], which could not be applicable in Italy where 1-1.5% of the population is estimated to be affected by HCV infection [

3]. This knowledge gap may also be present among high-risk populations, such as older people, who would benefit the most from educational and prevention interventions. The large number of undiagnosed HCV cases is the biggest concern, as risk factor screening is suboptimal.

For this reason, the Lombardy region promoted a population screening for HCV infection, specifically offered to people born from 1969 to 1989 [

3].

This study demonstrated that the current level of awareness of these main infectious diseases in citizens residing in a large mainly industrial city in Northern Italy is still very low and further effective health education campaigns for the main infectious diseases are urgently needed. Health information should focus on preparedness, confidence, counseling, and prevention strategies, thereby enhancing the public’s sense of social responsibility (less than 45% of the subjects have ever tested for HIV and 44% for HCV). Higher education level and younger age play important and positive roles in the knowledge of these infectious diseases [

23]. Education is important in forming attitudes related to health-changing behaviors and awareness together with specific health campaigns as WHO promotes around the world [

24].

The main limitations of this study include limited number of interviews, bias related to the self-compilation nature and selection bias due to the fact that only people who looked for performing the screening test or requested a counseling session were interviewed.

Our findings may serve as a roadmap for education programs to prevent, early diagnosis and treatment of these infections and to eliminate stigma, while no vaccines are available for HIV and HCV. Clearly, much more work is needed to bring these diseases of public health importance to the attention of our population and authorities, especially those in some subgroups. Our study highlights that misconceptions about HIV and HCV should be addressed in prevention and education programs, whose target should also be specific populations, such as older people, that are less frequently involved in the efforts to address these epidemics. This awareness should result in network building and collective actions that benefit all, contributing expertise, resources, knowledge and experience to achieving a common public good.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: E.Q.R., F.V., B.F.; data collection: F.V., B.F., I.P.; data cleaning and storage: F.V., B.F.; data analysis: F.V., B.F., S.A. supervision: E.Q.R.; writing—original draft: F.V., B.F., S.A., E.Q.R. writing—review and editing: F.V., B.F., S.A., I.P., E.F., F.C., E.Q.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following local entities and stakeholders who contributed to the implementation of community screening interventions.Municipality of Brescia, ASST-Spedali Civili Hospital of Brescia, Spedali Civili Foundation of Brescia, ATS-Brescia, University of Brescia, White Cross of Brescia, , Co-op “Il Calabrone” Brescia, Co-op “Lotta contro l’emarginazione” Brescia, Co-op “Bessimo”, Arcigay Orlando of Brescia, Caritas of Brescia, The Brescia Fast-Track Group: Donatella Albini, Silvia Amadasi, Claudia Anzoni, Alberta Ardenghi, Milena Bertazzi, Alessandra Bongiovanni, Anna Cambianica, Deborah Castelli, Carlo Cerini, Cosimo Colangelo, Federico Compostella, Verena Crosato, Melania Degli Antoni, Cecilia Fracassi, Benedetta Fumarola, Francesca Gaffurini, Federica Gottardi, Pierangela Grechi, Maurizio Gulletta, Ilaria Izzo, Davide Laurenda, Sofia Lovatti, Paola Magro, Valentina Marchese, Davide Minisci, Manuela Migliorati, Alice Mulè, Paola Nasta, Francesca Pennati, Nadia Pigoli, Stefania Agata Reale, Maria Cristina Rocchi, Francesco Rossini, Luca Rossi, Anita Sforza, Samuele Storti, Giorgio Tiecco, Lina Rachele Tomasoni, Santina Turriceni, Laert Zeneli.

*The authors are responsible for the choice and presentation of views contained in this article and for opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organizations.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This study is not under the obligation to obtain consent from participants because it was a completely anonymous survey.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with regard to the topics discussed in this manuscript.

References

- Welcome to Fast-Track Cities | Fast-Track Cities Available online: https://www.fast-trackcities.org/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- EpiCentro Aids - Aspetti epidemiologici in Italia Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/aids/epidemiologia-italia (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Screening gratuito per l’Epatite C Available online: https://www.regione.lombardia.it/wps/portal/istituzionale/HP/DettaglioRedazionale/servizi-e-informazioni/cittadini/salute-e-prevenzione/Prevenzione-e-benessere/screening-gratuito-epatite-c/screening-gratuito-epatite-c (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- About European Testing Week Available online: https://www.testingweek.eu/about-european-testing-week/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Fonner VA, Denison J, Kennedy CE, O’Reilly K, Sweat M. Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) for changing HIV-related risk behavior in developing countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Sep 12;9(9):CD001224. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001224.pub4. PMID: 22972050; PMCID: PMC3931252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun SP, Yoo HS, Lee JS. The impact of the pandemic declaration on public awareness and behavior: Focusing on COVID-19 google searches. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021 May;166:120592. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120592. Epub 2021 Jan 13. PMID: 33776154; PMCID: PMC7978359. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giuseppe G, Sessa A, Mollo S, Corbisiero N, Angelillo IF; Collaborative Working Group. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding HIV among first time attenders of voluntary counseling and testing services in Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2013 Jun 19;13:277. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-277. PMID: 23783146; PMCID: PMC3729531. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam M, Alabbadi AM, Abdel-Razeq S, Battah K, Malkawi L, Al-Abbadi MA, Mahafzah A. HIV Knowledge and Stigmatizing Attitude towards People Living with HIV/AIDS among Medical Students in Jordan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 10;19(2):745. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020745. PMID: 35055566; PMCID: PMC8775845. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li X, Yuan L, Li X, Shi J, Jiang L, Zhang C, Yang X, Zhang Y, Zhao D, Zhao Y. Factors associated with stigma attitude towards people living with HIV among general individuals in Heilongjiang, Northeast China. BMC Infect Dis. 2017 Feb 17;17(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2216-0. PMID: 28212610; PMCID: PMC5316215. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qashqari FS, Alsafi RT, Kabrah SM, AlGary RA, Naeem SA, Alsulami MS, Makhdoom H. Knowledge of HIV/AIDS transmission modes and attitudes toward HIV/AIDS infected people and the level of HIV/AIDS awareness among the general population in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2022 Sep 27;10:955458. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.955458. PMID: 36238245; PMCID: PMC9551601. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licata F, Angelillo S, Oliverio A, Di Gennaro G, Bianco A. How to Safeguard University Students Against HIV Transmission? Results of a Cross-Sectional Study in Southern Italy. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Jun 24;9:903596. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.903596. PMID: 35814762; PMCID: PMC9263725. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters SM, Rivera AV, Starbuck L, Reilly KH, Boldon N, Anderson BJ, Braunstein S. Differences in Awareness of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis and Post-exposure Prophylaxis Among Groups At-Risk for HIV in New York State: New York City and Long Island, NY, 2011-2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017 Jul 1;75 Suppl 3:S383-S391. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001415. PMID: 28604443. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mereu A, Liori A, Fadda L, Puddu M, Chessa L, Contu P, Sardu C. What do young people know about HIV? Results of a cross sectional study on 18-24-year-old students. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022 Dec 31;63(4):E541-E548. doi: 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2022.63.4.2555. PMID: 36891004; PMCID: PMC9986992. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arifin H, Ibrahim K, Rahayuwati L, Herliani YK, Kurniawati Y, Pradipta RO, Sari GM, Ko NY, Wiratama BS. HIV-related knowledge, information, and their contribution to stigmatization attitudes among females aged 15-24 years: regional disparities in Indonesia. BMC Public Health. 2022 Apr 1;22(1):637. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13046-7. PMID: 35365099; PMCID: PMC8976340. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merakou K, Costopoulos C, Marcopoulou J, Kourea-Kremastinou J. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour after 15 years of HIV/AIDS prevention in schools. Eur J Public Health. 2002 Jun;12(2):90-3. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/12.2.90. PMID: 12073759. [PubMed]

- Hebo HJ, Gemeda DH, Abdusemed KA. Hepatitis B and C Viral Infection: Prevalence, Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Occupational Exposure among Healthcare Workers of Jimma University Medical Center, Southwest Ethiopia. ScientificWorldJournal. 2019 Feb 3;2019:9482607. doi: 10.1155/2019/9482607. PMID: 30853866; PMCID: PMC6377947. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan NY, YacoobMayet A, Alaqeel SA, Al-Omar HA. Assessing the level of knowledge and available sources of information about hepatitis C infection among HCV-infected Egyptians. BMC Public Health. 2018 Jun 18;18(1):747. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5672-6. PMID: 29914434; PMCID: PMC6007060. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani MS, Ayn Aldeen A, Almalki RS, Algethami MB, Altowairqi NF, Alzahrani A, Almalki AS, Alzhrani RM, Algarni MA. Knowledge of and Testing Rate for Hepatitis C Infection among the General Public of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 23;20(3):2080. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20032080. PMID: 36767451; PMCID: PMC9915280. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 19. Mtengezo J, Lee H, Ngoma J, Kim S, Aronowitz T, DeMarco R, Shi L. Knowledge and Attitudes toward HIV, Hepatitis B Virus, and Hepatitis C Virus Infection among Health-care Workers in Malawi. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2016 Oct-Dec;3(4):344-351. doi: 10.4103/2347-5625.195921. PMID: 28083551; PMCID: PMC5214867. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camoni L, Regine V, Stanecki K, Salfa MC, Raimondo M, Suligoi B. Estimates of the number of people living with HIV in Italy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:209619. doi: 10.1155/2014/209619. Epub 2014 Jul 17. PMID: 25136562; PMCID: PMC4124713. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adoba P, Boadu SK, Agbodzakey H, Somuah D, Ephraim RK, Odame EA. High prevalence of hepatitis B and poor knowledge on hepatitis B and C viral infections among barbers: a cross-sectional study of the Obuasi municipality, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2015 Oct 11;15:1041. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2389-7. PMID: 26456626; PMCID: PMC4601136. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaquisse E, Meireles P, Fraga S, Mbofana F, Barros H. Knowledge about HIV, HBV and HCV modes of transmission among pregnant women in Nampula - Mozambique. AIDS Care. 2018 Sep;30(9):1161-1167. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1466984. Epub 2018 Apr 27. PMID: 29701075. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Li M, Jin M, Jing F, Wang H, Chen K. Public awareness of three major infectious diseases in rural Zhejiang province, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013 Apr 29;13:192. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-192. PMID: 23627258; PMCID: PMC3644285. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Global Health Days and Campaigns Available online: https://www.who.int/campaigns (accessed on 17 April 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).