Submitted:

05 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of poly (glycerol sebacate) (PGS) prepolymer

2.3. Fabrication of the electrospun scaffolds

2.4. Morphological assessment

2.5. Fourier transform infrared spectrometry

2.6. Measurement of contact angle

2.7. In vitro degradation

2.8. In vitro cellular studies

2.9. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of electrospinning parameters

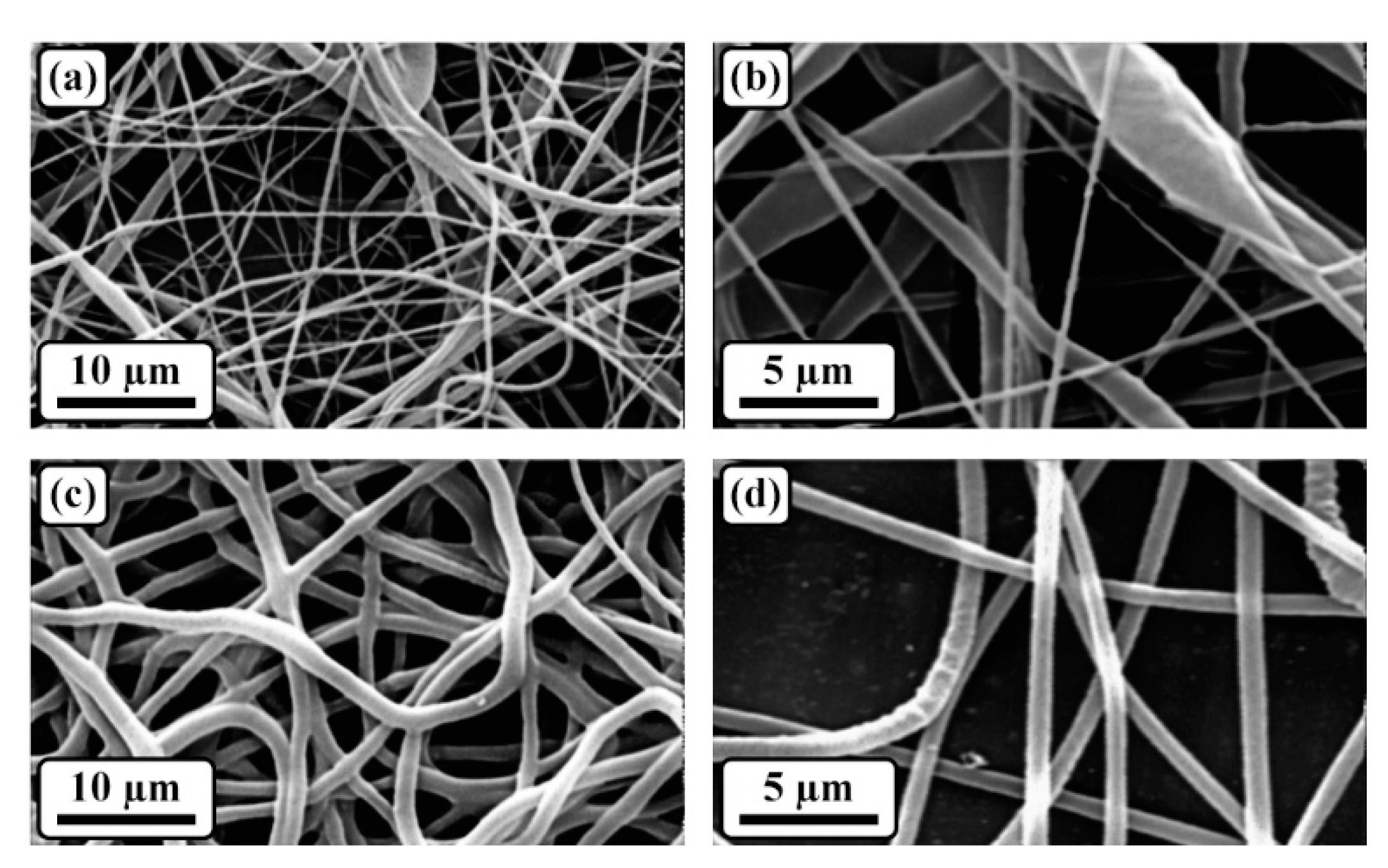

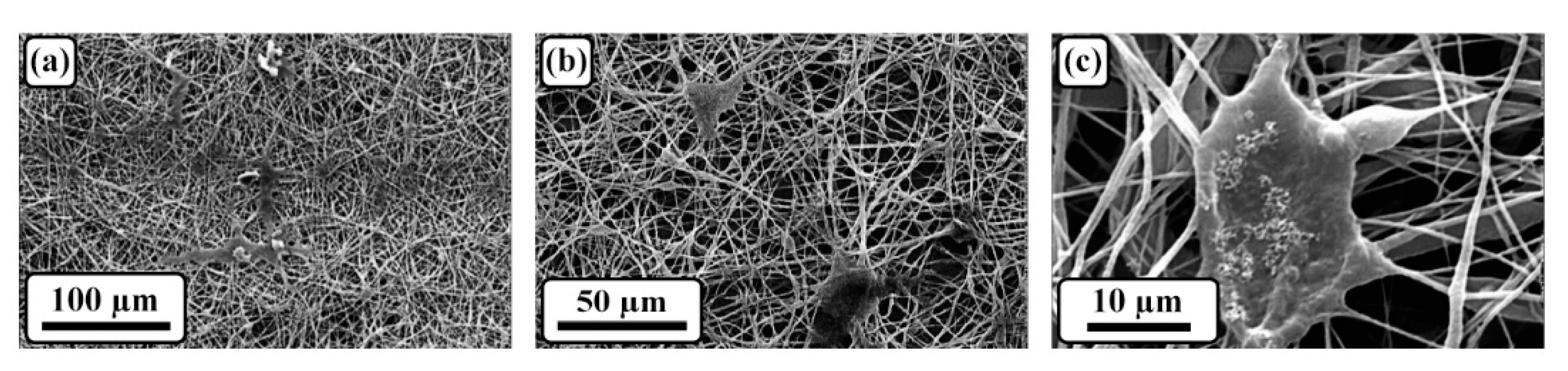

3.2. Morphological assessment

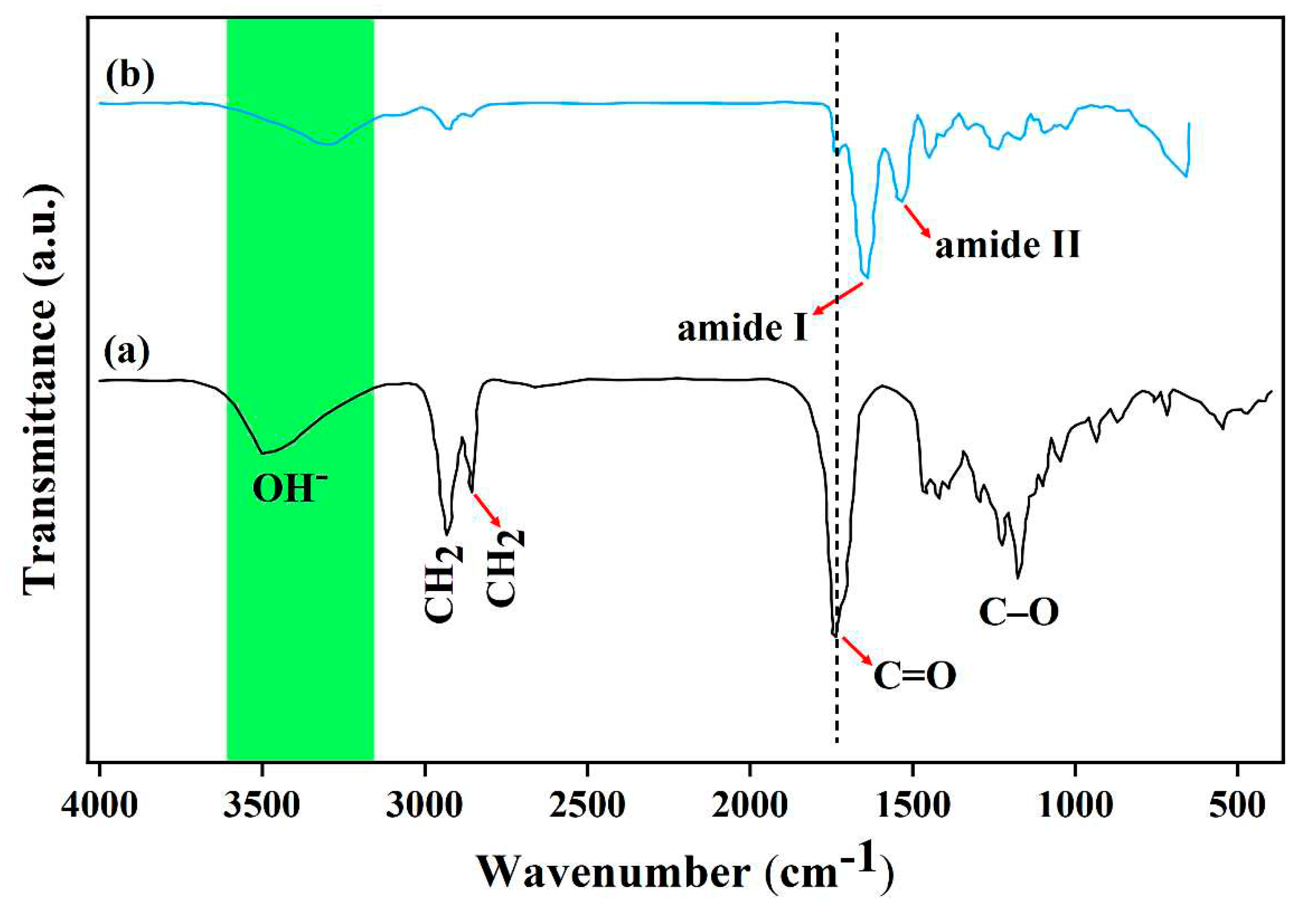

3.3. Structural evaluation

3.4. Hydrophilicity assessment

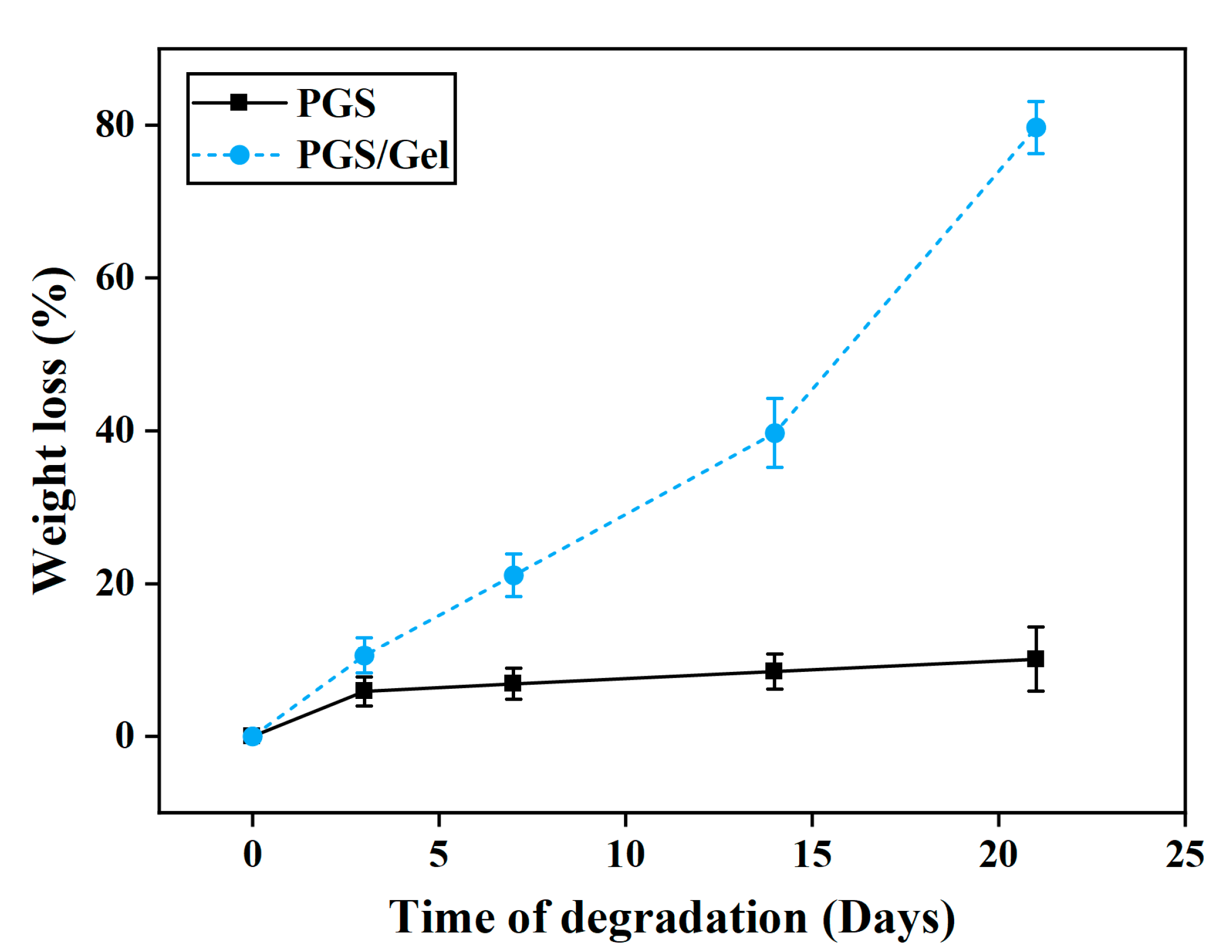

3.5. In vitro degradation

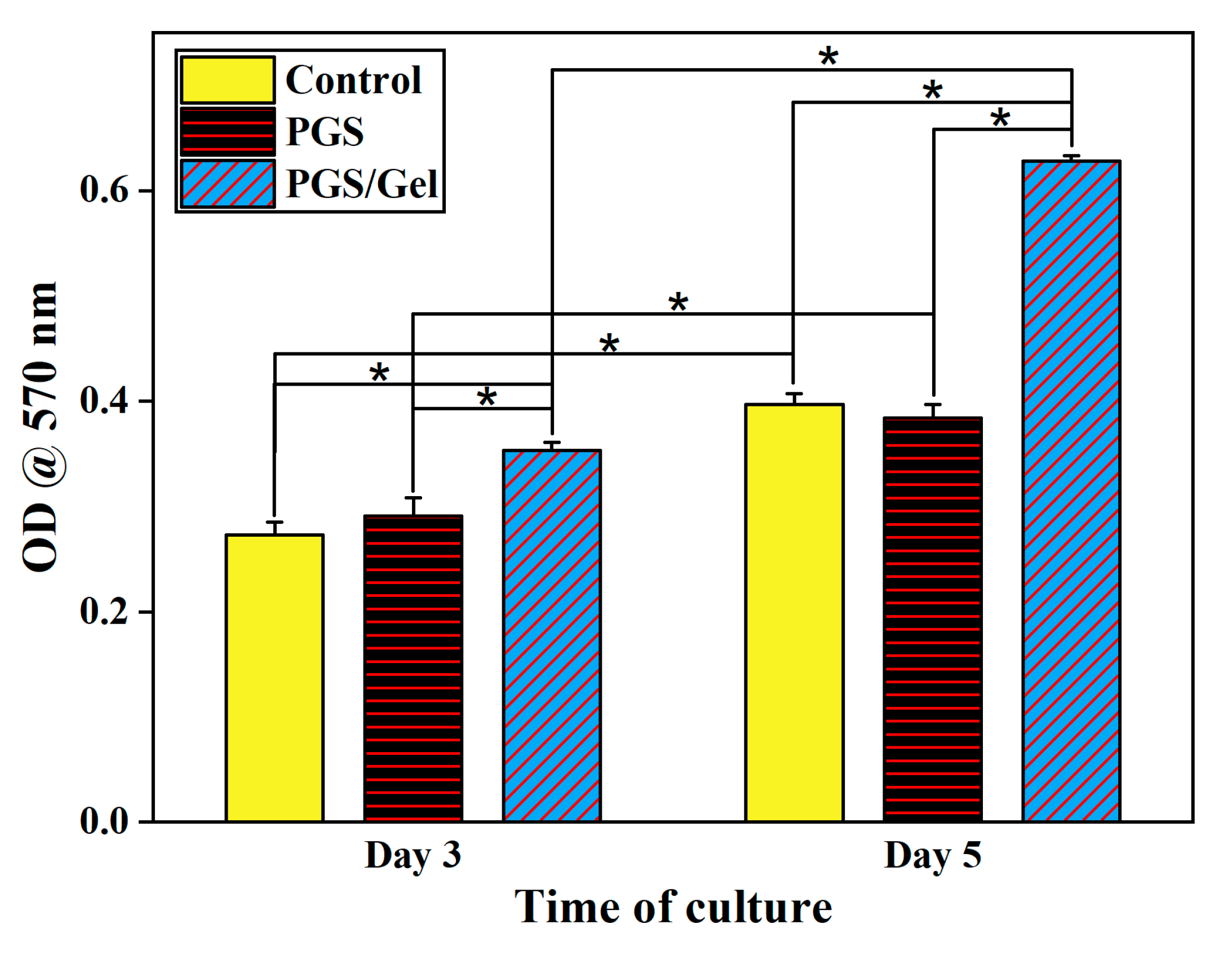

3.6. In vitro cellular studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crowe, E.; Scott, C.; Cameron, S.; Cundell, J.H.; Davis, J. Developing Wound Moisture Sensors: Opportunities and Challenges for Laser-Induced Graphene-Based Materials. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssefi Azarfam, M.; Nasirinezhad, M.; Naeim, H.; Zarrintaj, P.; Saeb, M. A Green Composite Based on Gelatin/Agarose/Zeolite as a Potential Scaffold for Tissue Engineering Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jales, S.T.L.; Barbosa, R.d.M.; de Albuquerque, A.C.; Duarte, L.H.V.; da Silva, G.R.; Meirelles, L.M.A.; da Silva, T.M.S.; Alves, A.F.; Viseras, C.; Raffin, F.N.; et al. Development and Characterization of Aloe vera Mucilaginous-Based Hydrogels for Psoriasis Treatment. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Xu, J.; Shen, J.; Qin, L.; Yuan, W. Biomimetic Hierarchical Nanocomposite Hydrogels: From Design to Biomedical Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokaya, D.; Skallevold, H.E.; Srimaneepong, V.; Marya, A.; Shah, P.K.; Khurshid, Z.; Zafar, M.S.; Sapkota, J. Shape Memory Polymeric Materials for Biomedical Applications: An Update. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizely, K.; Wagner, K.T.; Mandla, S.; Gustafson, D.; Fish, J.E.; Radisic, M. Angiopoietin-1 derived peptide hydrogel promotes molecular hallmarks of regeneration and wound healing in dermal fibroblasts. iSci. 2023, 26, 105984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Yu, H.; Zhou, X.; Li, M.; Xiao, L.; Ruan, Q.; Huang, X.; Li, L.; Xie, W.; Guo, X.; et al. Topical administration of pterostilbene accelerates burn wound healing in diabetes through activation of the HIF1α signaling pathway. Burn. 2022, 48, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, A.; Keshri, G.K.; Gupta, A. Hippophae rhamnoides L. leaf extract diminishes oxidative stress, inflammation and ameliorates bioenergetic activation in full-thickness burn wound healing. Phytomed. Plus 2022, 2, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lacerda Bukzem, A.; dos Santos, D.M.; Leite, I.S.; Inada, N.M.; Campana-Filho, S.P. Tuning the properties of carboxymethylchitosan-based porous membranes for potential application as wound dressing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 166, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Ma, X.; Fan, L.; Gao, Y.; Deng, H.; Wang, Y. Accelerating dermal wound healing and mitigating excessive scar formation using LBL modified nanofibrous mats. Mater. Des. 2020, 185, 108265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhu, S.; Deng, Y.; Xie, M.; Zhao, M.; Sun, T.; Yu, C.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, R.; Cheng, K.; et al. Construction of multifunctional hydrogel with metal-polyphenol capsules for infected full-thickness skin wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 24, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaycıoğlu, Z.; Kahya, N.; Adımcılar, V.; Kaygusuz, H.; Torlak, E.; Akın-Evingür, G.; Erim, F.B. Antibacterial nano cerium oxide/chitosan/cellulose acetate composite films as potential wound dressing. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 133, 109777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonguzhali, R.; Khaleel Basha, S.; Sugantha Kumari, V. Novel asymmetric chitosan/PVP/nanocellulose wound dressing: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soubhagya, A.S.; Moorthi, A.; Prabaharan, M. Preparation and characterization of chitosan/pectin/ZnO porous films for wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wang, K.; Yu, D.-G.; Yang, Y.; Bligh, S.W.A.; Williams, G.R. Electrospun Janus nanofibers loaded with a drug and inorganic nanoparticles as an effective antibacterial wound dressing. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2020, 111, 110805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Pan, H.; Ji, D.; Li, Y.; Duan, H.; Pan, W. Curcumin-loaded sandwich-like nanofibrous membrane prepared by electrospinning technology as wound dressing for accelerate wound healing. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2021, 127, 112245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, P.; Chhabra, R.; Muke, S.; Narvekar, A.; Sathaye, S.; Jain, R.; Dandekar, P. Fabrication and characterization of starch-TPU based nanofibers for wound healing applications. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2021, 119, 111316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Tobías, H.; Morales, G.; Grande, D. Comprehensive review on electrospinning techniques as versatile approaches toward antimicrobial biopolymeric composite fibers. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2019, 101, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadizadeh, M.; Naeimi, M.; Rafienia, M.; Karkhaneh, A. A bifunctional electrospun nanocomposite wound dressing containing surfactin and curcumin: In vitro and in vivo studies. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2021, 129, 112362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Tang, H.; Deng, W.; Guo, H.; Zeng, L. Antibacterial and antioxidant films based on HA/Gr/TA fabricated using electrospinning for wound healing. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 626, 122139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, P.; Zargar Kharazi, A.; Asgary, S.; Parham, S. Comparing the wound healing effect of a controlled release wound dressing containing curcumin/ciprofloxacin and simvastatin/ciprofloxacin in a rat model: A preclinical study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2022, 110, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Li, L.; Yang, D.; Nie, J.; Ma, G. Electrospun Core–Shell Fibrous 2D Scaffold with Biocompatible Poly(Glycerol Sebacate) and Poly-l-Lactic Acid for Wound Healing. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2020, 2, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaloo Kermani, P.; Zargar Kharazi, A. A Promising Antibacterial Wound Dressing Made of Electrospun Poly (Glycerol Sebacate) (PGS)/Gelatin with Local Delivery of Ascorbic Acid and Pantothenic Acid. J. Polym. Environ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Amirsadeghi, A.; Hassanajili, S.; Azarpira, N. Bioactive antibacterial bilayer PCL/gelatin nanofibrous scaffold promotes full-thickness wound healing. Int. J. pharm. 2020, 583, 119413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanhueza, C.; Hermosilla, J.; Bugallo-Casal, A.; Da Silva-Candal, A.; Taboada, C.; Millán, R.; Concheiro, A.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Acevedo, F. One-step electrospun scaffold of dual-sized gelatin/poly-3-hydroxybutyrate nano/microfibers for skin regeneration in diabetic wound. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2021, 119, 111602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahani, H.; Barati, A.; Arjomandzadegan, M.; Vatankhah, E. Nanofibrous cellulose acetate/gelatin wound dressing endowed with antibacterial and healing efficacy using nanoemulsion of Zataria multiflora. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharaziha, M.; Nikkhah, M.; Shin, S.-R.; Annabi, N.; Masoumi, N.; Gaharwar, A.K.; Camci-Unal, G.; Khademhosseini, A. PGS:Gelatin nanofibrous scaffolds with tunable mechanical and structural properties for engineering cardiac tissues. Biomater. 2013, 34, 6355–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahedi, M.; Karbasi, S. Electrospun halloysite nanotube loaded polyhydroxybutyrate-starch fibers for cartilage tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 214, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi-Mobarakeh, L.; Semnani, D.; Morshed, M. A novel method for porosity measurement of various surface layers of nanofibers mat using image analysis for tissue engineering applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 106, 2536–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamian, M.; Kalaee, M.R.; Dehkordi, S.R.; Panahi-Sarmad, M.; Tirgar, M.; Goodarzi, V. Design and characterization of poly(glycerol-sebacate)-co-poly(caprolactone) (PGS-co-PCL) and its nanocomposites as novel biomaterials: The promising candidate for soft tissue engineering. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 138, 109985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekinoglu, M.; Öztürk, Ş.; Chen, B.; Edirisinghe, M.; Ulubayram, K. Preparation of poly(glycerol sebacate) fibers for tissue engineering applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 121, 109297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajan, M.H.; Panahi-Sarmad, M.; Alikarami, N.; Shojaei, S.; Saeidi, A.; Khonakdar, H.A.; Shahrousvan, M.; Goodarzi, V. Using solvent-free approach for preparing innovative biopolymer nanocomposites based on PGS/gelatin. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 131, 109720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrami, P.; Karbasi, S.; Farahbakhsh, Z.; Bigham, A.; Rafienia, M. Fabrication and characterization of novel polyhydroxybutyrate-keratin/nanohydroxyapatite electrospun fibers for bone tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 1368–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asl, M.A.; Karbasi, S.; Beigi-Boroujeni, S.; Zamanlui Benisi, S.; Saeed, M. Evaluation of the effects of starch on polyhydroxybutyrate electrospun scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Fawal, G.; Hong, H.; Mo, X.; Wang, H. Fabrication of scaffold based on gelatin and polycaprolactone (PCL) for wound dressing application. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 63, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Guan, F.; Sun, F.; Gong, X. Preparation and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate)/gelatin composite nanofibrous. Surf. Interface. 2022, 33, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadalipour, M.; Behzad, T.; Karbasi, S.; Mohammadalipour, Z. Optimization and characterization of polyhydroxybutyrate/lignin electro-spun scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 218, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayatnazari, A., M. Movahedi, and M. Naseri, Fabrication And Characterization Of Bilayer Wound Dressing Polyurethane-Gelatin/Polycaprolactone For Usage In Tissue Engineering. 2021.

- Liu, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, M.; Gu, C.; Ye, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lang, M.; Tan, W.-S. Fabrication and evaluation of modified poly(ethylene terephthalate) microfibrous scaffolds for hepatocyte growth and functionality maintenance. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2020, 109, 110523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzobon, L.G.; Sperling, L.E.; Teixeira, C.E.; Malysz, T.; Pranke, P. Development of a conduit of PLGA-gelatin aligned nanofibers produced by electrospinning for peripheral nerve regeneration. Chem-Biol. Interact. 2021, 348, 109621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi, A.; Amini, S.; Amirpour, N.; Kazemi, M.; Zargar Kharazi, A.; Salehi, H.; Rafienia, M. Promoting neural cell proliferation and differentiation by incorporating lignin into electrospun poly(vinyl alcohol) and poly(glycerol sebacate) fibers. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2019, 104, 110005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rarima, R.; Unnikrishnan, G. Poly(lactic acid)/gelatin foams by non-solvent induced phase separation for biomedical applications. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 177, 109187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagiah, N.; Madhavi, L.; Anitha, R.; Anandan, C.; Srinivasan, N.T.; Sivagnanam, U.T. Development and characterization of coaxially electrospun gelatin coated poly (3-hydroxybutyric acid) thin films as potential scaffolds for skin regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2013, 33, 4444–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Xiong, J.; Li, J.; Miao, X.; Lan, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Cai, N.; Tang, Y. Fabrication and in vitro evaluation of PCL/gelatin hierarchical scaffolds based on melt electrospinning writing and solution electrospinning for bone regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2021, 128, 112287. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoumi, N.; Jean, A.; Zugates, J.T.; Johnson, K.L.; Engelmayr Jr, G.C. Laser microfabricated poly(glycerol sebacate) scaffolds for heart valve tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2013, 101A, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Row | Material name | Company/Country made |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gelatin (Gel) | Sigma Aldrich/USA |

| 2 | Sebacic acid | Sigma Aldrich/USA |

| 3 | Glycerol | Sigma Aldrich/USA |

| 4 | N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) | Merck/Germany |

| 5 | 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) | Merck/Germany |

| 6 | Acetic acid | Merck/Germany |

| 7 | Ethanol solution | Nasr/Iran |

| 8 | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) | GIBCO/USA |

| 9 | Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDF) cell line | Cell Bank of Pasteur Institute/Iran |

| 10 | Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM), Glutamax (High Glucose) | GIBCO/USA |

| 11 | Fetal bovine serum (FBS) | Vivacell/Iran |

| 12 | Penicillin/streptomycin | GIBCO/USA |

| 13 | Trypsin-EDTA (0.05% Trypsin in 0.04 mM EDTA) | Bioidea/Iran |

| 14 | Glutaraldehyde (25% Aqueous Solution) | Merck/Germany |

| 15 | Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | Sigma Aldrich/USA |

| 16 | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) | Sigma Aldrich/USA |

| Sample | Mean fiber diameter (nm) | Porosity percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PGS | 371.2 ± 64.8 | 77.2 ± 2.4 |

| PGS/Gel | 252.4 ± 32.5 | 80.8 ± 1.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).