Submitted:

06 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Whether the grants have led to more collaboration between ministries, increased involvement of stakeholders (e.g. business sector and civil society organisation (CSO), and contributed to improve the integration of adaptation issues across ministries;

- Whether the Readiness Grants promoted more (contribute to enhance) institutional adaptive capacity.

2. Conceptual framework: institutional change in the context of climate change adaptation as barrier and enabler

2.1. Climate change adaptation and institutional changes

2.2. Efficiency and coherence in climate change adaptation policies: the concept of policy integration or mainstreaming

- Enabling factors and barriers: the normative framework, the political will, cognitive and analytical capacities, and the institutional (organizational and procedural) arrangements [44]

- Integration levels: horizontal policy integration; vertical policy integration; stakeholder integration; knowledge integration; temporal integration [43].

- Integration as a process, an output or an outcome [5].

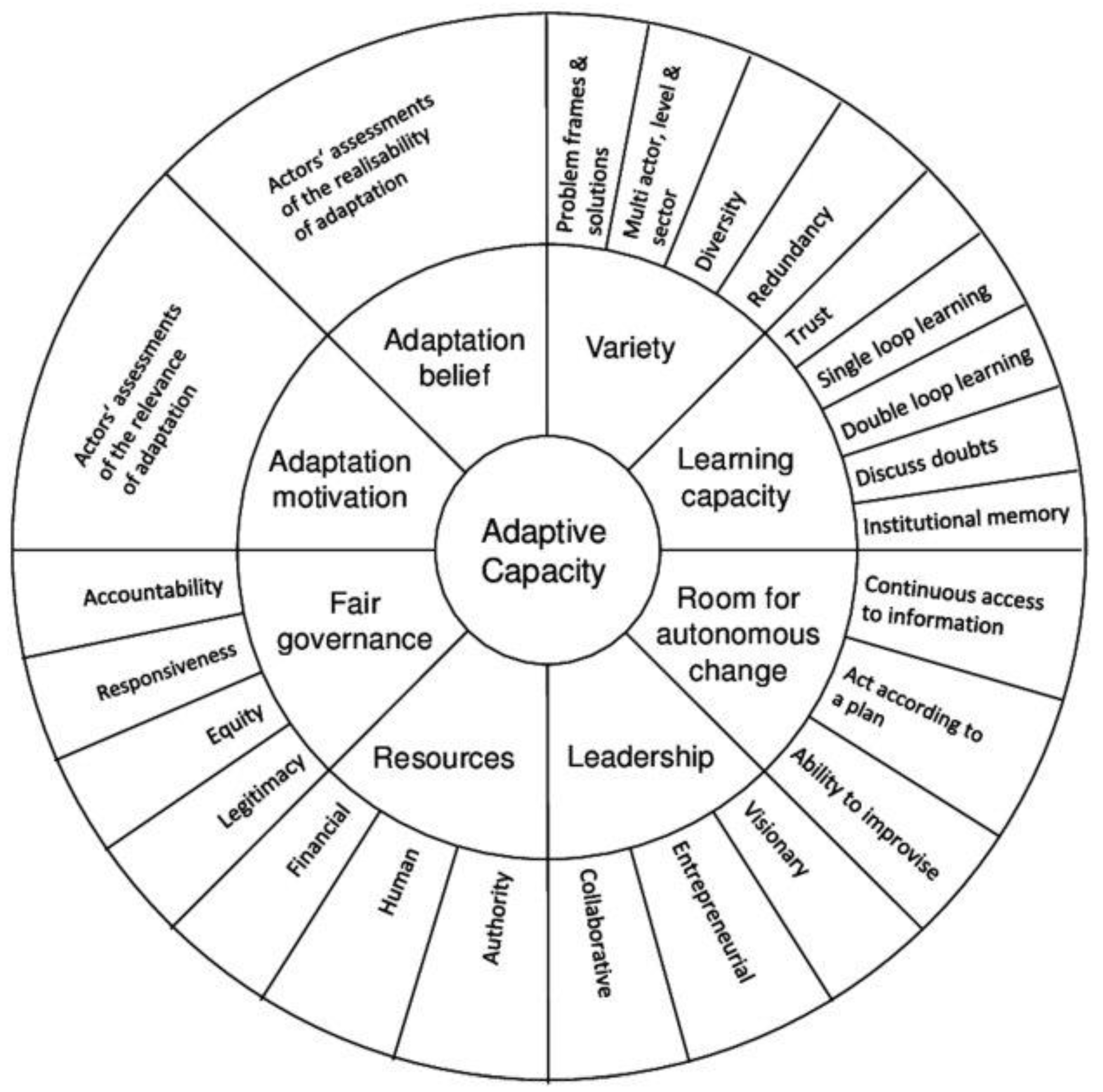

2.3. Institutional Adaptive Capacity

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Rational and research focus

3.2. Assessing Adaptation Maintreaming

- Programmatic mainstreaming: the modification of the implementing body’s sector work by integrating aspects related to adaptation into on-the-ground operations, projects or programmes;

- Managerial mainstreaming: the modification of managerial and working structures, including internal formal and informal norms and job descriptions, the configuration of sections or departments, as well as personnel and financial assets, to better address and institutionalise aspects related to adaptation;

- Intra- and inter-organisational mainstreaming: the promotion of collaboration and networking with other departments, individual sections or stakeholders (i.e. other governmental and non-governmental organisations, educational and research bodies and the general public) to generate shared understandings and knowledge, develop competence and steer collective issues of adaptation;

- Regulatory mainstreaming: the modification of formal and informal planning procedures, including planning strategies and frameworks, regulations, policies and legislation, and related instruments that lead to the integration of adaptation;

- Directed mainstreaming: higher level support to redirect the focus to aspects related to mainstreaming adaptation by e.g. providing topic-specific funding, promoting new projects, supporting staff education or directing responsibilities.

3.3. Assessing Adaptive Capacity

| Categories | Definition and Aim | Corresponding Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Variety/ Diversity | Assess whether a variety of sectors and a diversity of stakeholders were engaged and consulted in the making of the various Readiness outputs, and whether the Readiness Grants promoted a diversity of approaches in defining core adaptation policies. |

|

| Learning capacity | Assess if the Readiness Grants favoured the development of a culture of learning and sharing in targeted and across ministries, including increased monitoring and evaluation of activities. |

|

| Room for autonomous change or Agile planning | Assess the contribution of the Readiness Grants to the production of more agile adaptation plans, looking at the capacity of actors to access information, act according to plan or improvise. |

|

| Leadership | Analyse the role of leadership to understand to what extent the Readiness Grants promoted a visionary, entrepreneurial, or collaborative leadership and more processes of exchanges between Ministries. |

|

| Resources | Assess the potential of the Readiness Grants to develop the capacity of core staff and their ability to access to more financial or technical support. |

|

| Fair governance | Assess whether the Readiness Grants encouraged a higher degree of transparency, equity, accountability and whether they strengthened the legitimacy of the institutions. |

|

| Belief and Motivation | Assess how the Readiness Grants contributed to increase the belief of the efficacy of adaptation interventions and the overall motivation to implement adaptation policies at the national level. |

|

4. Results: Assessing the Effects Readiness Grant’s in SIDS

4.1. Contribution of Readiness Grants to adaptation integration: a promising opportunity

4.1.1. Programmatic mainstreaming

4.1.2. Managerial mainstreaming

4.1.3. Inter-Intra organisational mainstreaming

4.1.4. Regulatory mainstreaming

4.1.5. Directed mainstreaming

4.2.1. A positive impact on a limited number of institutions

5. Discussion

5.1. An opportunistic short-term move for potential long-term adaptation integration

5.2. Divergent strategies for institutional adaptive capacity

6. Conclusion

Appendix A: Climate change and adaptation policies in Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, and Haiti

| Description |

|

Caribbean SIDS are facing common climate change threats, but diversified impacts According to the 6th IPCC report on adaptation (Working Group II), SIDS are already facing many climate change impacts: temperature increase, stronger tropical cyclones, change in rainfall patterns, more intense and repeated droughts, storm surges, sea-level rise (SLR), and threats to biodiversity like coral bleaching or the growth of the number of invasive species (Mycoo et al., 2022). People in coastal cities and rural communities have already been affected, along with almost all economic and social sectors: health, water, agriculture, infrastructure and food security (Mycoo et al., 2022). SLR is a particular threat as it is estimated that in 2017, 22 million people in the Caribbean lived below six metres above sea level (Mycoo et al., 2022). Additionally, extreme weather events like tropical cyclones are increasing in intensity and frequency: in 2017 alone, twenty-two out of the twenty-nine Caribbean islands were affected by a Category 4 or 5 hurricane (Mycoo et al., 2022). Although this overall picture applies to all Caribbean SIDS, potential impacts of climate change are nuanced by countries’ particular vulnerabilities. Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda is a Caribbean Small Island Developing State (SIDS) of around 456 km2 of land, divided in two inhabited islands and other small islands (Government of Antigua and Barbuda, 2022). The country was ranked in 2012 by the World Bank amongst the top Five countries most at risk to multiple hazards, “with 100% of their population and land area exposed to two or more environmental hazards” (Government of Antigua and Barbuda, 2022, p.6). Climate change impacts Antigua and Barbuda in two main ways: i) physical impacts; ii) economic and social impacts. Sea-Level rise (SLR), droughts and hurricane are of particular concern as Antigua and Barbuda is composed of low-lying islands: 70 percent of Antigua is below 30 m above sea level, and most of Barbuda below 3 m above sea level (Government of Antigua and Barbuda, 2022). Estimations indicate that given the current and projected levels of SLR, Antigua and Barbuda might lose by 2080 50.8 to 64.9 km2 of coastal land - in other words, up to 14 percent of the country’s inhabited land (Government of Antigua and Barbuda’s, Department of Environment Ministry of Health, Wellness and the Environment, 2021). With climate change, droughts are also expected to become more intense and frequent (up to 81.8 percent of probability of severe droughts over a five-year period), with an average rainfall decline around 26 percent under a business-as-usual scenario (Government of Antigua and Barbuda, 2022). Droughts cause a particular strain on the water supply with heavy reliance on water desalination plants running on fossil fuel energy (ibid). Finally, the country is particularly exposed to extreme weather events, with projection of direct hit by a tropical storm every 6six to seven years (ibid, p.6). Extreme weather and other expected climate change impacts have a disproportionate bearing on Antigua and Barbuda’s already strained economy. Despite being ranked among the high-income countries, the country is socially fragile with 14 percent of people unemployed and 18 percent below the poverty line (Government of Antigua and Barbuda, 2022). External shocks can have a devastating impact on the populations (it is estimated an additional 10 percent of the population is at risk of poverty), infrastructures and the country’s development as a whole (the economy depends on tourism at 80 percent). For instance, Hurricane Irma in 2017 caused “damage and loss of USD155.1 million (10 percent of Gross Domestic Product -GDP) impacting houses, public buildings, hotels, firms engaged in tourism sector and safety nets of vulnerable households” (Government of Antigua and Barbuda’s, Department of Environment Ministry of Health, Wellness and the Environment, 2021, p. 27). Such losses impact a small-sized economy already plagued with a heavy debt burden, averaging 104.36 percent of GDP in 2015 (International Monetary Fund, n.d.), which limits the country’s fiscal ability to cope with climate change impacts with adequate adaptation or mitigation interventions (Government of Antigua and Barbuda, 2022). In addition, Antigua and Barbuda’s ability to attract international climate funds is limited by its high-income status ((World Bank Group, n.d.), preventing the country to access concessional loans (Government of Antigua and Barbuda’s, Department of Environment Ministry of Health, Wellness and the Environment, 2021). Belize Belize is classified as a SIDS and is ranked amongst the upper middle-income countries. It is rather large compared to other Caribbean SIDS, covering an area of around 22,967 km2, including 280 km of coastland. Around 42 percent of Belize’s population live in poverty (Government of Belize, 2021). Climate change is considered one of the biggest threats to the country’s development. It is estimated, depending on the projections, that Belize will witness by 2100 a temperature rise ranging between 2 and 4 degrees Celsius, and a 20 percent increase in the intensity of rainfalls while the rainy season will decrease by 7-8 percent (Government of Belize, 2021). The country is ranked 3rd among small states for susceptibility to natural disasters and 5th for climate change risks among SIDS (Cheasty et al., 2018; Government of Belize, 2021). The low-lying topography of the country makes Belize’s major infrastructures particularly at risk from flooding, storm surges and SLR (Cheasty et al., 2018). The capital city, Belize City, which is on the coast, is particularly exposed (Government of Belize, 2021). Extreme weather events are projected to have severe impacts on the country, with an average 7 percent GDP loss every year (Cheasty et al., 2018). The country’s economy is reliant on agriculture, fisheries and tourism – sectors which will all be severely affected by climate change. Losses are estimated to amount 10-20 percent of agricultural production by 2100, and annual losses of USD 12,5 million for fisheries. SLR, extreme weather events, flooding, vector-borne diseases are a considered a threat to the tourism industry, along with the impacts on biodiversity (coral reefs) and landscape (beaches). Total tourism income could decrease by up to USD 24 million a year (Government of Belize, 2021). Climate change could threaten the energy sector: the change in rainfall patterns and anticipated decrease in precipitation coupled with increased evaporation could impact the hydropower electricity generation which represents around 50 percent of the country’s electricity (Cheasty et al., 2018). Finally, Belize’s economy is vulnerable to the devastating consequences of extreme weather events and the country is burdened by a high-level of debt (around 100 percent of GDP) which limits its ability to make climate change adaptation investments (Cheasty et al., 2018). Haiti Haiti is the only Caribbean SIDS amongst the world’s Least Developed Countries. The country is located at the heart of the Caribbean and shares the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic. It is one of the largest Caribbean SIDS, with a total land area of around 27,750 km2 and a territorial sea of 30,000 km2. Most of the Haitian territory is occupied by a mountainous landscape and abrupt slopes (Gouvernement de la République d’Haïti, 2021). Haiti is the poorest country of the Latin America and Caribbean region and is ranked 170 out of 189 countries in terms of human development index (World Bank, 2021). Haiti is particularly vulnerable extreme weather events: it is located right on the hurricanes’ paths, and the country gets regularly hit by tropical storms. It is estimated that during the last 20 years, the country lost on average USD400 million a year to climatic events (Gouvernement de la République d’Haïti, 2021a). Haiti is most affected by flooding, drought, intense rainfall, landslides, soil erosion, saltwater intrusion, and hurricanes. Haiti’s institutional, social and economic fragility additionally contributes to aggravate the situation: deforestation and lack of proper water drainage system increase the impacts of hurricanes, storm surge, and flooding (Institut de la Francophonie pour le Développement Durable and Ministry of Environment - Republic of Haiti, 2021). Current and expected climate change’s impacts are likely to worsen: the average yearly temperature should increase by 0.8 to 1 degree Celsius in 2030, annual rainfall should decrease by 6 to 20 percent and some studies point to an increase up to 80 percent on category 4 and 5 hurricanes (Gouvernement de la République d’Haïti, 2021a). Other projections estimate SLR increase around 0.13 to 0.56 m by 2090 and that 50 percent of Haiti will be at risk of desertification by 2050 (Institut de la Francophonie pour le Développement Durable and Ministry of Environment - Republic of Haiti, 2021). Flooding is of special concern for Haiti. The country’s urban centres, located in the alluvial plains of large river systems, are especially vulnerable to inundations risks. Hurricanes Hanna (2008), Sandy (2012), Matthew (2016) caused intense floods, destroying many lives and buildings, and an increase in water borne diseases (Institut de la Francophonie pour le Développement Durable and Ministry of Environment - Republic of Haiti, 2021). Extreme weather events linked to climate change often exacerbate other natural disasters: in 2021, tropical storm Grace hit the country shortly after a 7.2 earthquake stroke the southern peninsula. Climate change strongest impacts are already felt in the agriculture and fisheries sectors, along with affecting the availability of freshwater resources. The expected coupling of decrease of annual rainfall with more intense downpours will negatively impact food productivity and worsen food security issues. Freshwater supplies will additionally be more vulnerable to the change in precipitations and saltwater intrusions caused by storm surges (Institut de la Francophonie pour le Développement Durable and Ministry of Environment - Republic of Haiti, 2021). Finally, Haiti’s overall lack of institutional capacity, adequate funding and infrastructures are serious challenges to the country’s development and ability to address the current and expected impacts of climate change (Gouvernement de la République d’Haïti, 2021a). |

|

An uneven policy landscape to tackle climate change adaptation issuesAt the regional level, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) unites fifteen Caribbean member states and five associate territories in a single market and foreign policy initiative. Its decisions are non-binding until ratified by Member States (Gilbert-Roberts, 2011). The CARICOM developed the 2009-2015 Regional Framework for Achieving Development Resilient to Climate Change which was approved CARICOM Heads of Government in July 2009 (Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre, 2017). The framework is designed as a guidance for member States to follow climate resilient development pathways and comprises five strategic objectives, including the Strategic Element 1 which is to “Mainstream climate change adaptation strategies into the sustainable development agendas of the CARICOM Member States” (Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre, 2009, p.iv). Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda developed several policies to address climate change mitigation and adaptation, among them: the Policy Framework for Integrated Adaptation Planning and Management in Antigua and Barbuda (2002), the National Physical Development Plan (2012), the Medium Term Development Strategy (2015), the National Comprehensive Disaster Management Policy and Strategy for Antigua and Barbuda (2015– 2017), the Environmental Protection and Management Act (2015) and the draft Building Code for the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), the Coastal Zone Management Plan (2016), (Department of Environment, Ministry of Health and the Environment, Antigua & Barbuda, 2017). Belize The Ministry of Environment defines the climate policies and plans, and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MFED) is responsible for resource mobilisation and climate finance. In terms of policy, the country is quite advanced, with what Cheasty et al. (2018) refer to as “a well-articulated policy framework and sectoral strategies for resilience- building” (p.29) and “good example of effective mainstreaming of climate-related projects” (p. 47). Among those policies, the Belize’s Nationally Determined Contribution (Government of Belize, 2021) refers particularly to Horizon 2030 (national development framework); the National Climate Resilience Investment Plan 2013; the National Climate Change Policy, Strategy and Action Plan (NCCPSAP) (administrative and legislative framework, 2014); the National Energy Policy Framework (2014); the Growth and Sustainable Development Strategy (2014). Haiti According to the draft Adaptation Communication prepared for the CoP26, the Republic of Haiti lacks specific environmental and climate change policies except the international treaties and the legal framework is weak (Gouvernement de la République d'Haïti, 2021b). The current strategic documents referring to climate change and adaptation more specifically are the Programme Stratégique pour la Résilience Climatique6 (PSRC), Haiti’s Nationally Determined contribution (2015), Haiti’s Revised National Adaptation Plan of Action (2017), the Politique Nationale sur les Changements Climatiques7 (PNCC) and contributions from the Schéma National d'Aménagement du Territoire8 (SNAT) and the Système National de Gestion des Risques et des Désastres9 (SNGRD) (Gouvernement de la République d'Haïti, 2021b). To address those challenges, Caribbean SIDS rely on climate finance, and particularly concessional grants. Readiness Grants have therefore a key role to play to strengthen institutional capacity, and Section 2 below details the methodology used to answer the research questions. |

- Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (2009). Regional Framework for Achieving Development Resilient to Climate Change. Available at: https://www.caribbeanclimate.bz/blog/2017/11/28/the-regional-climate-change-strategic-framework-and-its-implementation-plan-for-development-resilient-to-climate-change-us2800000/ [Accessed 4 Aug. 2022].

- Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (2017). The Regional Climate Change Strategic Framework and Its Implementation Plan for Development Resilient to Climate Change. [online] https://www.caribbeanclimate.bz. Available at: https://www.caribbeanclimate.bz/blog/2017/11/28/the-regional-climate-change-strategic-framework-and-its-implementation-plan-for-development-resilient-to-climate-change-us2800000/ [Accessed 2 Aug. 2022].

- CPI, 2019. Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019 [Barbara Buchner, Alex Clark, Angela Falconer, Rob Macquarie, Chavi Meattle, Rowena Tolentino, Cooper Wetherbee]. Climate Policy Initiative, London. Available at: https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/ global-climate-finance-2019/

- Department of Environment, Ministry of Health and the Environment, Antigua & Barbuda (2017). National Adaptation Planning Support for Antigua and Barbuda through Ministry of Health and Environment. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/readiness-proposals-antigua-and-barbuda-ministry-health-and-environment-adaptation-planning.pdf [Accessed 25 Mar. 2022].

- Gilbert-Roberts, T.-A. (2011). CARICOM Governance in crisis: Challenges of Context and Political Traditions. Trade Negotiations Insights, 10(2).

- Gouvernement de la République d’Haïti (2021a). Contribution Déterminée au Niveau National de la République D’Haïti. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/CDN%20Revisee%20Haiti%202022.pdf [Accessed 20 Apr. 2022].

- Gouvernement de la République d’Haïti (2022). Communication d’Haïti Relative à l’Adaptation. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/ACR/2022-07/Communication%20d%20Haiti%20relative%20a%20l%20adaptation.pdf [Accessed 25 Jul. 2022].

- Government of Antigua and Barbuda’s, Department of Environment Ministry of Health, Wellness and the Environment (2021). Updated Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC). Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/ATG%20-%20UNFCCC%20NDC%20-%202021-09-02%20-%20Final.pdf [Accessed 12 May 2022]

- Government of Belize (2021). BELIZE Updated Nationally Determined Contribution. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/Belize%20Updated%20NDC.pdf [Accessed 14 Apr. 2022].

- Government of Belize Press Office (2022). Newly Created Climate Finance Unit. [online] https://www.pressoffice.gov.bz. Available at: https://www.pressoffice.gov.bz/newly-created-climate-finance-unit/ [Accessed 15 Jul. 2022].

- Institut de la Francophonie pour le Développement Durable and Ministry of Environment - Republic of Haiti (2021). Strengthening NDA Capacity for Greater Leadership on Climate Change Adaptation. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/20211231-haiti-ifdd-proposal.pdf [Accessed 12 May 2022].

- International Monetary Fund (n.d.). Antigua and Barbuda Debt to GDP Ratio. [online] data.imf.org. Available at: https://data.imf.org/?sk=388DFA60-1D26-4ADE-B505-A05A558D9A42&sId=1479331931186 [Accessed 12 Jun. 2022].

- Mahoney, J. and Thelen, K.A. (2010). A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change. In: Explaining Institutional Change: ambiguity, agency, and Power. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- United Nations (n.d.). Climate Finance. [online] United Nations. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/raising-ambition/climate-finance [Accessed 28 May 2022].

- World Bank (2021). Haïti Présentation. [online] https://www.banquemondiale.org. Available at: https://www.banquemondiale.org/fr/country/haiti/overview [Accessed 12 Jun. 2022].

- World Bank Group (n.d.). High income| Data. [online] data.worldbank.org. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/country/XD [Accessed 20 Aug. 2022].

Appendix B. Readiness proposals selection table

| Number | Doc name | Country | Sector | Type of project | Proposing entity | Adaptation focus | Date submitted | Date Approved | Budget (USD) | Budget for adaptation/ integration/ research area | Institutional focus (Y/N/S) |

| AB-1 | multi-year-readiness-proposal-ab-doe | Antigua and Barbuda | Energy | Multi-Year Strategic Readiness for Antigua and Barbuda: Supporting Antigua and Barbuda’s NDCs implementation towards a transformation to Climate Resilient and Low-Emission Development Pathway by 2030 | Department of Environment, Ministry of Health and Environment (DoE) | Capacity building to support the project pipeline and the achievement of the country's NDC's targets | 30/08/2020 | 25/10/2021 | 2 836 551 | 1 034 220 | Y |

| AB-2 | readiness-proposals-antigua-and-barbuda-ministry-health-and-environment-adaptation-planning | Antigua and Barbuda | Governance | National Adaptation Planning in Antigua and Barbuda (NAP) | Ministry of Health and Environment | Data collection, assessment, preparation of the NAP, development of a sustainable financing strategy | 26/01/2017 | 01/11/2017 | 3 000 000 | 2 621 500 | Y |

| AB-3 | readiness-proposals-antigua-and-barbuda-department-environment-entity-support-strategic-framework | Antigua and Barbuda | Governance | Realizing direct access climate financing in Antigua and Barbuda and the Eastern Caribbean | Department of Environment, Ministry of Health and Environment | support the accreditation of a national direct access entity through the accreditation of the Department of Environment. Readiness funding will also support the further development and submission of an Enhanced Direct Access (EDA) funding proposal, to include project activities in Dominica and Grenada and in partnership with the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) Commission | 26/10/2016 | 01/03/2017completed | 620 250 | 438 000 | Y |

| AB-4 | readiness-proposals-antigua-and-barbuda-department-environment-entity-support | Antigua and Barbuda | Governance | Accelerating a transformational pipeline of Direct Access climate adaptation and mitigation projects in Antigua & Barbuda | Ministry of Health and Environment | National direct access entity meets all accreditation conditions and EDA funding proposal conditions; Accreditation Master Agreements (AMA) requirements are met annually and independent functions are strengthened using international best practice• Baseline gender assessment to guide transformational gender interventions in Antigua and Barbuda’s country programme• Strengthened climate rationale and evidence base for adaptation and mitigation interventions• Technology needs assessments for five sectors, including feasibility analyses and risk assessment annexes, to significantly advance the Country Programme pipeline | 30/04/2018 | 23/12/2018 | 931 000 | 791 200 | Y |

| AB-5 | readiness-proposals-antigua-and-barbuda-department-environment-nda-strengthening-and-country | Antigua and Barbuda | Governance | NDA Strengthening and Country Programming | Environment Division, Ministry of Health and the Environment | Strengthening the NDAThe NDA will hire consultants and procure services to build the capacity of theEnvironment Division and the Debt Management Unit that will be responsible forcoordinating with other ministries on the Green Climate Fund (the Fund).Strategic frameworks for engagement with the Fund, including thepreparation of country programmes. | 08/07/2015 | completed | 300 000 | N/A | Y |

| B-3 | 20211231-belize-pact-proposal | Belize | Governance | Enhancing Access for Climate Finance Opportunities, through pre accreditation support to Belize Social Investment Fund (BSIF) and Ministry of Economic Development-Belize and technical support for Belize National Protected Areas System (BNPAS) Entities, Belize | Protected Areas Conservation Trust (PACT) | to address institutional gaps identified that inhibit Belize’s ability to successfully access climate finance through entities such as the GCF. | 16/06/2021 | 31/12/2021 | 600 000 | 505 060 | Y |

| B-6 | readiness-proposals-belize-5cs-nda-strengthening-and-country-programming | Belize | Governance | NDA Strengthening & Country Programming | Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre | NDA capacity to undertake Fund-related responsibilities and engage national stakeholders strengthenedStrategic framework for engagement with the Fund development | 14/12/2016 | -completed | 300 000 | 300 000 | Y |

| B-7 | readiness-proposals-belize-ccccc-entity-support | Belize | Governance and entity strengthening | Building Capacity for direct access to Climate Finance - Support for the accreditation of the Development Finance Cooperation and Social Investment Fund of Belize | Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre | to facilitate the preparation of nominated entities to meet GCF accreditation standards in areas such as environmental and social safeguards (ESS), the GCF gender policy, and project development, monitoring and evaluation. This will allow for national institutions to effectively administer resources from the GCF and other resources partners, ensuring high country ownership. | 15/09/2018 | 22/12/2018 | 355 365 | 214 000 | Y |

| H-2 | readiness-proposals-haiti-undp-adaptation-planning | Haiti | Governance | Integrating climate change risks into national development planning processes in Haiti | United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) | Strengthen institutional and technical capacities for iterative development of NAP for an effective integration of CCA into national and sub-national coordination, planning and budgeting process. | 23/04/2018 | 15/05/2019 | 2 856 957 | 2 450 040 | Y |

| H-3 | 20211231-haiti-ifdd-proposal | Haiti | Governance | Strengthening NDA Capacity for greater leadership on Climate Change Adaptation | Institut de la Francophonie pour le Développement Durable (IFDD) | (a) strengthen the technical and operational capacities of the NDA and; (b) enhance stakeholder engagement mechanisms and processes | 26/06/2021 | 31/12/2021 | 300 000 | 255 354 | Y |

| H-5 | readiness-proposals-haiti-undp-nda-strengthening-and-country-programming | Haiti | Governance | Green Climate Fund (GCF) Readiness Programme in Haiti | United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) | to support the Government of Haiti through its GCF Focal Point in strengthening their national capacities to effectively and efficiently plan for, access, manage, deploy and monitor climate financing in particular through the GCF. | 16/12/2016 | 05/06/2017completed | 430 000 | 341 268 | Y |

| H-6 | readiness-proposals-haiti-ccccc-nda-strengthening-and-country-programming | Haiti | Governance | Institutional Strengthening and Preparatory Support for the Republic of Haiti | Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre | to continue the strengthening of Haiti’s ministerial institutions and associated services in order to enhance the country’s ability to effectively manage climate risk, promote greater public/private partnerships and mobilize climate resources. | 23/09/2018 | 22/12/2018 | 403 390 | 332 750 | Y |

Appendix C: Interview questions set

- Target interviewees

- -

- The actual projects and their implementation status;

- -

- The policy framework and institutional arrangements regarding climate change adaptation in a given country.

- Interview guide

- Questions set

- i)

-

General contextual questionsObjective: Getting a sense of who the interviewee is and his/her ability to give insightful/informed answers to the following questions

- What is your function within the <Relevant department> ?

- You are currently acting a Nationally Designed Authority for the Green Climate Fund. What does it entail for you? How long have you been in this position?

- How is the department organised? How many people and what is the turnover?

- ii)

-

Current climate change adaptation policy landscapeObjective: Setting a baseline for the analysis and confirming information from the document review

- 4.

- What are your country's climate change adaptation institutional priority needs?

- 5.

- What are your country's climate change adaptation policy needs?

- iii)

-

Past and ongoing readiness projectsObjective: Understanding the context of the grants and assessing quickly the expectations of the respondents towards those grants

- 6.

- There are currently XX GCF readiness projects in country. Already XX were completed.

- 7.

- What are the main focus of these projects? Do they target your institutional priority areas and needs?

- 8.

- What was your role in designing these projects? Did you take an active part in their development?

- iv)

-

Perception on the impact of the readiness projects – Would you say the Readiness Grants (Asking to rank from 0 to 10 and to justify?):Objective: Assessing the institutional adaptive capacity potential of the grants within the framework of the adaptive capacity wheel. Getting a sense of change (before/after) and sustainability (temporary improvement or lasting change) through poking the type of impact (normative, organisational/procedural, political, resources/capacities…)

- 9.

- Promoted a diversity of approaches and favoured the intervention of a variety of actors in defining core adaptation policies?

- 10.

- Helped develop a culture of learning and knowledge sharing in the targeted institutions?

- 11.

- Led to the development of agile adaptation plans?

- 12.

- Adequately and sustainably developed the capacities of teams and their ability to reach for more resources?

- 13.

- Improved the accountability, transparency, legitimacy on climate change issues of relevant institutions?

- 14.

- Favoured a collaborative leadership and more processes of exchanges between the Ministries?

- 15.

- Increased the belief of the efficacy of adaptation actions and the overall motivation to implement adaptation policies?

- v)

-

Conclusion and closeObjective: Drawing on from the previous section, getting a sense of what really works well or what is needed to improve

- 16.

- Overall, your assessment would be that those grants helped your country to better adapt, at least in your institutional priority areas?

- 17.

- What would you suggest is needed for climate finance to be more impactful in your country at the policy level?

| Criterion | ||

| Variety/ Diversity | Variety of problem frames | |

| Multi-actor, multi-level,multi-sector | ||

| Redundancy | ||

| Learning capacity | Trust | |

| Single/double loop learning | ||

| Discuss doubts | ||

| Institutional memory | ||

| Agile planning | Continuous access to information | |

| Act according to plan | ||

| Capacity to improvise | ||

| Leadership | Visionary | |

| Entrepreneurial | ||

| Collaborative | ||

| Resources | Authority | |

| Human resources | ||

| Financial resources | ||

| Fair governance | Legitimacy | |

| Equity | ||

| Responsiveness | ||

| Accountability | ||

| Psychological | Belief | |

| Motivation | ||

Appendix C: List of Acronyms

|

References

- Mycoo, M., Wairiu, M., Campbell, D., Duvat, V., Golbuu, Y., Maharaj, S., Nalau, J., Nunn, P., Pinnegar, J. and Warrick, O. (2022). Small Islands. In: H-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem and B. Rama, eds., Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. In Press.

- Green Climate Fund (2020a). Updated Strategic Plan for the Green Climate Fund: 2020-2023. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/updated-strategic-plan-green-climate-fund-2020-2023.pdf [Accessed 28 May 2022].

- Green Climate Fund (2020b). GCF Portfolio Dashboard. [online] Green Climate Fund. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/projects/dashboard [Accessed 28 May 2022].

- Khan, M., & Roberts, J. T. (2013). Adaptation and international climate policy. WIREs Climate Change, 4(3), 171–189. [CrossRef]

- Persson, Å. (2004). Environmental Policy Integration: an Introduction. Stockholm: Stockholm Environment Institute. PINTS – Policy Integration for Sustainability Background Paper.

- Persson, Å. (2008). Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation into Official Development Assistance: a Case of International Policy Integration. EPIGOV Papers, No. 36. Ecologic –Institute for International and European Environmental Policy, Berlin.

- Runhaar, H., Driessen, P. and Uittenbroek, C. (2014). Towards a Systematic Framework for the Analysis of Environmental Policy Integration. Environmental Policy and Governance, [online] 24(4), pp.233–246. [CrossRef]

- Runhaar, H., Wilk, B., Persson, Å., Uittenbroek, C. and Wamsler, C. (2018). Mainstreaming Climate adaptation: Taking Stock about ‘What Works’ from Empirical Research Worldwide. Regional Environmental Change, 18(4), pp.1201–1210. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, T.J. and Fogelman, C. (2013). Déjà Vu or Something new? the Adaptation Concept in the Climate Change Literature. Geoforum, 48, pp.42–53. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, N. and Hill, K. (2021). Climate change, adaptation planning and institutional integration: A literature review and framework. Sustainability, 13. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J., Termeer, C., Klostermann, J., Meijerink, S., van den Brink, M., Jong, P., Nooteboom, S. and Bergsma, E. (2010). The Adaptive Capacity Wheel: a Method to Assess the Inherent Characteristics of Institutions to Enable the Adaptive Capacity of Society. Environmental Science & Policy, 13(6), pp.459–471. [CrossRef]

- Fidelman, P., Van Tuyen, T., Nong, K. and Nursey-Bray, M. (2017). The institutions-adaptive Capacity nexus: Insights from Coastal Resources co-management in Cambodia and Vietnam. Environmental Science & Policy, 76, pp.103–112. [CrossRef]

- Grothmann, T., Grecksch, K., Winges, M. and Siebenhüner, B. (2013). Assessing Institutional Capacities to Adapt to Climate change: Integrating Psychological Dimensions in the Adaptive Capacity Wheel. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 13(12), pp.3369–3384. [CrossRef]

- Mycoo, M.A. (2017). Beyond 1.5 °C: Vulnerabilities and Adaptation Strategies for Caribbean Small Island Developing States. Regional Environmental Change, 18(8), pp.2341–2353. [CrossRef]

- Dorman, D.R. and Ciplet, D. (2021). Sustainable Energy for All? Assessing Global Distributive Justice in the Green Climate Fund’s Energy Finance. Global Environmental Politics, pp.1–23. [CrossRef]

- Garschagen, M. and Doshi, D. (2022). Does funds-based Adaptation Finance Reach the Most Vulnerable countries? Global Environmental Change, 73, p.102450. [CrossRef]

- Omukuti, J. (2020). Country Ownership of adaptation: Stakeholder Influence or Government control? Geoforum, 113, pp.26–38. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, A. (2020). Role of Intermediaries in Shaping Climate Finance in Developing Countries—Lessons from the Green Climate Fund. Sustainability, 12(14), p.5507. [CrossRef]

- Zamarioli, L.H., Pauw, P. and Grüning, C. (2020). Country Ownership as the Means for Paradigm Shift: the Case of the Green Climate Fund. Sustainability, 12(14), p.5714. [CrossRef]

- Bertilsson, J. and Thörn, H. (2020). Discourses on Transformational Change and Paradigm Shift in the Green Climate Fund: the Divide over Financialization and Country Ownership. Environmental Politics, pp.1–19. [CrossRef]

- Puri, J., Prowse, M., De Roy, E. and Huang, D. (2022). Assessing the Likelihood for Transformational Change at the Green Climate Fund: an Analysis Using self-reported Project Data. Climate Risk Management, 35, p.100398. [CrossRef]

- Green Climate Fund (2022). Country Readiness. [online] Green Climate Fund. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/readiness [Accessed 28 May 2022].

- Independent Evaluation Unit (2018). Independent Evaluation of Green Climate Fund Readiness and Preparatory Support Programme. [online] https://ieu.greenclimate.fund. Songdo: Green Climate Fund. Available at: https://ieu.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/rpsp-main-report.pdf [Accessed 13 May 2022]. Evaluation Report No. 1.

- Government of Antigua and Barbuda (2022). Climate Change Country Programme 2020. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/country-programme-antigua-and-barbuda.pdf [Accessed 12 Apr. 2022].

- Cheasty, A., Leigh, D., Parry, I., Vasilyev, D., Boyer, M., Gunasekera, R. and Alfaro-Pelico, R. (2018). Belize - Climate Change Policy Assessment. [online] http://www.imf.org. Washington: International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2018/11/16/Belize-Climate-Change-Policy-Assessment-46372 [Accessed 18 Jun. 2022]. IMF Country Report No. 18/329.

- Henstra, D. (2015). The Tools of Climate Adaptation policy: Analysing Instruments and Instrument Selection. Climate Policy, 16(4), pp.496–521. [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, J. and Biesbroek, R. (2013). Comparing Apples and oranges: the Dependent Variable Problem in Comparing and Evaluating Climate Change Adaptation Policies. Global Environmental Change, 23(6), pp.1476–1487. [CrossRef]

- Ulibarri, N., Ajibade, I., Galappaththi, E.K., Joe, E.T., Lesnikowski, A., Mach, K.J., Musah-Surugu, J.I., Nagle Alverio, G., Segnon, A.C., Siders, A.R., Sotnik, G., Campbell, D., Chalastani, V.I., Jagannathan, K., Khavhagali, V., Reckien, D., Shang, Y., Singh, C. and Zommers, Z. (2021). A Global Assessment of Policy Tools to Support Climate Adaptation. Climate Policy, 22(1), pp.77–96. [CrossRef]

- Beunen, R. and Patterson, J.J. (2016). Analysing Institutional Change in Environmental governance: Exploring the Concept of ‘institutional Work’. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(1), pp.12–29. [CrossRef]

- Bisaro, A., Roggero, M. and Villamayor-Tomas, S. (2018). Institutional Analysis in Climate Change Adaptation Research: a Systematic Literature Review. Ecological Economics, 151, pp.34–43. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.J. (2021a). Remaking Political Institutions in Sustainability Transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 41. [CrossRef]

- Biesbroek, G.R., Klostermann, J.E.M., Termeer, C.J.A.M. and Kabat, P. (2013). On the Nature of Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation.nRegional Environmental Change, 13(5), pp.1119–1129. [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, S.C. (2017). Institutional Dimensions of Climate Change adaptation: Insights from the Philippines. Climate Policy, 18(4), pp.499–511. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.J. (2021b). Remaking Political Institutions: Climate Change and beyond. [online] Elements in Earth System Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J. and Thelen, K.A. (2010). A Theory of Gradual Institutional Change. In: Explaining Institutional Change: ambiguity, agency, and Power. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Patterson, J., de Voogt and Sapiains, R. (2019). Beyond inputs and outputs: Process-oriented explanation of institutional change in climate adaptation governance. Environmental Policy and Governance, 29, pp.360–375. [CrossRef]

- Viñuela, L., Barma, N.H. and Huybens, E. (2014). Overview Institutions Taking Root: Building State Capacity in Challenging Contexts. In: Institutions Taking Root : Building State Capacity in Challenging Contexts. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

- Eisenack, K., Moser, S.C., Hoffmann, E., Klein, R.J.T., Oberlack, C., Pechan, A., Rotter, M. and Termeer, C.J.A.M. (2014). Explaining and Overcoming Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 4(10), pp.867–872. [CrossRef]

- Adelle, C. and Russel, D. (2013). Climate Policy Integration: a Case of Déjà Vu? Environmental Policy and Governance, 23(1), pp.1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. and Pauleit, S. (2016). Making Headway in Climate Policy Mainstreaming and ecosystem-based adaptation: Two Pioneering countries, Different pathways, One Goal. Climatic Change, 137(1-2), pp.71–87. [CrossRef]

- Mickwitz, P., Aix, F., Beck, S., Carss, D., Ferrand, N., Görg, C., Jensen, A., Kivimaa, P., Kuhlicke, C., Kuindersma, W., Máñez, M., Melanen, M., Monni, S., Branth Pedersen, A., Reinert, H. and van Bommel, S. (2009). Climate Policy Integration, Coherence and Governance. [online] HAL. Helsinki: Partnership for European Environmental Research.

- Macchi, S. and Ricci, L. (2014). Mainstreaming Adaptation into Urban Development and Environmental Management Planning: a Literature Review and Lessons from Tanzania. In: S. Macchi and M. Tiepolo, eds., Climate Change Vulnerability in Southern African Cities. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Climate, pp.109–124. [CrossRef]

- Mullally, G. and Dunphy, N. (2015). State of Play Review of Environmental Policy Integration Literature. Dublin: National Economic and Social Council (NESC). Research Series Paper No.7.

- Nilsson, M. and Persson, Å. (2017). Policy note: Lessons from Environmental Policy Integration for the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Environmental Science & Policy, 78, pp.36–39. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. (2017). Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation in Small Island Developing States. Climate and Development, 11(1), pp.47–59. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.B.R., Möller, V., van Diemen, R., Fuglestvedt, J.S., Masson-Delmotte, V., Méndez, C., Semenov, S. and Reisinger, A., eds (2021). IPCC, 2021: Annex VII: Glossary. In: V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou, eds., Climate Change 2021: the Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [online] Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York,: Cambridge University Press, pp.2215–2256. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_AnnexVII.pdf [Accessed 16 Aug. 2022].

- Brooks, N., & Adger, WN. (2005). Assessing and enhancing adaptive capacity. In B. Lim, E. Spanger-Siegfried, I. Burton, E. Malone, & S. Huq (Eds.), Adaptation Policy Frameworks for Climate Change: Developing Strategies, Policies and Measures (pp. 165-181). Cambridge University Press.

- Adger, N.W., Arnell, N.W. and Tompkins, E.L. (2005). Successful Adaptation to Climate Change across Scales. Global Environmental Change, 15(2), pp.77–86. [CrossRef]

- Munaretto, S. and Klostermann, J.E.M. (2011). Assessing Adaptive Capacity of Institutions to Climate change: a Comparative Case Study of the Dutch Wadden Sea and the Venice Lagoon. Climate Law, 2(2), pp.219–250. [CrossRef]

- Akanbi, R.T., Davis, N. and Ndarana, T. (2021). Assessing South Africa’s Institutional Adaptive Capacity to Maize Production in the Context of Climate change: Integration of a Socioeconomic Development Dimension. INTEGRATED ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT, 17, pp.1056–1069. [CrossRef]

- Green Climate Fund (2019). Readiness and Preparatory Support Programme: Strategy for 2019-2021 and Work Programme 2019. [online] https://www.greenclimate.fund. Songdo: Green Climate Fund. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/gcf-b22-08.pdf [Accessed 26 Jun. 2022].

- Green Climate Fund (2021). Readiness Pipeline as of 24 June 2021. [online] Green Climate Fund. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/readiness-pipeline [Accessed 29 May 2022].

- Green Climate Fund (2020c). Readiness and Preparatory Support Programme Guidebook. [online] https://www.greenclimate.fund. Songdo: Green Climate Fund. Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/readiness-guidebook_2.pdf [Accessed 26 Jun. 2022].

- Harvey, F. (2022). Grenadian Minister Simon Stiell to Be next UN Climate Chief. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/aug/15/grenadian-minister-simon-stiell-to-be-next-un-climate-chief [Accessed 21 Aug. 2022].

| 1 | For more information, see Appendix A. |

| 2 | For more information, see Appendix A |

| 3 | For more information, see Appendix A |

| 4 | Detailed question set is available in Appendix C |

| 5 | This is evidenced by the recent appointment of Grenadian Prime Minister as the Head of the next Conference of the Parties in 2022 [54] |

| 6 | Strategic Programme for Climate Resiliences (PSRC) |

| 7 | National Policy on Climatic Changes (PNCC) |

| 8 | National Land use plan (SNAT) |

| 9 | National framework for disasters and risks management (SNGRD) |

| Objective | Description | Title 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity building for climate finance coordination | Countries established human, technical and institutional capacity to drive low-emission and climate resilient development, including through direct access to the GCF | data |

| Strategies for climate finance implementation | Ambitious strategies implemented to guide GCF investment based on analyses of emissions reduction potential and climate vulnerability and risk and in complementarity with other sources of climate finance | data |

| National adaptation plans and/or adaptation planning processes | National adaptation plan (NAP) and/or other adaptation planning processes formulated to catalyse public and private adaptation finance at scale | data |

| Paradigm-shifting pipeline development | Country priority-aligned and paradigm-shifting concept notes and funding proposals submitted by countries with least capacity, including LDCs, and direct access accredited entities | |

| Knowledge sharing and learning (cross-cutting) | Increased levels of awareness, knowledge sharing and learning that contribute to countries developing and implementing transformational projects in low-carbon and climate-resilient development pathways. | data |

| Criteria for climate adaptation integration Wamsler and Pauleit (2016) | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Programmatic Mainstreaming | Climate finance planning Development of NAP (e.g. Haiti as a strategy non-binding) Participatory development of framework, multi-year documents (country programmes, NAP) Focus on baseline assessments and data collection to inform policies and plans |

|

| Managerial Mainstreaming | Capacity building interventions Creating new positions (consultants) Knowledge sharing mechanisms (workshops, platforms) |

|

| Inter-Intra organisation mainstreaming: | Multiple provisions for Stakeholder consultations Capacity building interventions Focus on the engagement of the private sector References to regional/ international cooperation on adaptation tools and planning |

|

| Regulatory mainstreaming | New sectoral legislative output (NAP – Antigua and Barbuda) Amendments of current regulations (Antigua and Barbuda only) |

|

| Directed mainstreaming | Mainstream climate finance and adaptation at all levels (Antigua and Barbuda only) |

|

| Element | Criterion | Evaluation1 |

|---|---|---|

| Variety | Problem frames and solutions | + |

| Multi actor, level and sector | ++ | |

| Diversity | + | |

| Redundancy | N/A | |

| Learning capacity | Trust | + |

| Single loop learning | N/A | |

| Double loop learning | N/A | |

| Discuss doubts | + | |

| Institutional memory | + | |

| Agile planning and room for autonomous change | Continuous access to information | + |

| Act according to plan | + | |

| Ability to improvise | = | |

| Leadership | Visionary | = |

| Entrepreneurial | N/A | |

| Collaborative | ++ | |

| Resources | Authority | + |

| Human | ++ | |

| Financial | ++ | |

| Fair governance | Legitimacy | + |

| Equity | + | |

| Responsiveness/ Transparency | + | |

| Accountability | ++ | |

| Psychological | Belief | = |

| Motivation | = |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).