INTRODUCTION

Urethral prolapse (UP) is a rare condition in which the distal urethral mucosa protrudes circularly from the external urethral meatus (1). Although it is more common in prepubertal girls (80%), it can also be seen in postmenopausal women (2). It is an incidental pathology in asymptomatic prepubertal girls. One of the largest published series on UP was by Owen et al. According to this study, its incidence was found to be approximately 1 in 3000 (3). It has also been reported that UP cases are more common in black girls (4). The etiology of UP is not exactly known. Congenital prolapse in pediatric patients occurs as a result of poor submucosal collagen support; the mucosa becomes hypermobile, resulting in prolapse (5). In postmenopausal women, UP usually develops due to estrogen deficiency, hypermobility, and increased intra-abdominal pressure (6).

Urethral bleeding is the most common symptom (7). In postmenopausal women, urinary symptoms such as dysuria, urgency, and urinary retention are also present, depending on severity. Urinary symptoms are not usually seen in prepubertal girls. Diagnosis is based on physical examination and clinical findings. When a mass appearance is seen in the distal urethra on inspection, other pathologies such as ureterocele, malignancies, condyloma, urethral caruncle should be excluded. There is no obvious treatment or management in symptomatic patients. The priority in treatment is conservative management, such as manual reduction, sitz baths, topical estrogen creams, and antibiotics (8). Local anesthesia may be beneficial, especially in elderly patients with urethral prolapse. Surgical excision is preferred in patients who do not heal with these methods or who have a large or necrotic UP (9). Minor postoperative bleeding is the most common complication after excision (10). Other complications include urethral stricture, voiding dysfunction, and recurrence (11). In this case report, we describe the surgical treatment of a patient with necrotic UP who presented with urinary retention.

CASE PRESENTATION

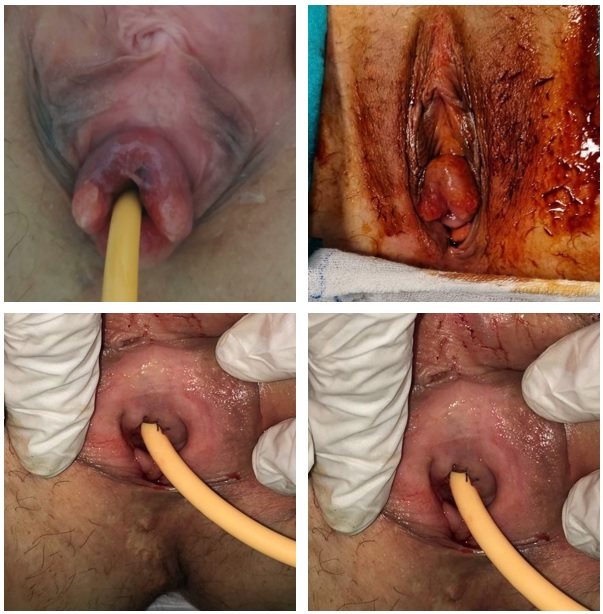

A 56 year old postmenopausal female patient was admitted to the outpatient clinic with acute urinary retention and perineal pain. She also suffered from constipation related to her dietary habits. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images If we look at the history of the patient, he had hypertension. He also had a history of surgery for a brain aneurysm 1 year ago. There was the use of antihypertensive and anticoagulant therapy. In the urinary ultrasonography performed on the patient, 700 cc of post-void residual ( PVR ) was detected. No dilatation or any mass lesion was detected in the upper urinary system. In the pelvic examination, it was observed that there was an erythematous necrotizan urethral prolapse of approximately 3-4 cm in diameter protruding from the vagina. ( Figure 1a/b). A catheter was then inserted, and topical estrogen and antibiotic treatment was started. The patient was advised to take a sitz bath with sitting antiseptic soap and was called for control after 2 weeks. At the follow-up 2 weeks later, there was no regression in the patient's prolapse and perineal pain. Urinary retention developed after the catheter was removed. Thereupon, surgical treatment was planned and the patient was hospitalized.

SURGERY

We began the operation with cystoscopy under general anesthesia. In cystoscopy, bilateral ureteral orifices were in the usual location and shape. Bladder mucosa and bladder neck were normal. When the bladder was completely filled, no leakage was observed in the bladder. Manual reduction of the prolapse failed. Then inserted a 14 Fr foley catheter. Suspension sutures were placed on the prolapsed urethral mucosa for a better view. A vaginal pack was inserted to assist with haemostasis. Fixation sutures were placed on the intact mucosa at the 3 and 6 o'clock positions to be used in anastomosis before starting the dissection so that the healthy urethral tissue would not escape after excision. Following the suspension and fixation sutures, a circular incision was made to define the proximal margin of the intact urethral mucosa. Starting from this point, dissection was performed and the necrotic prolapsed mucosa was excised circumferentially. After excision, anastomosis of the intact urethra was performed with 4/0 absorbable polyglactin suture ( Figure 1c/d). The procedure was ended by placing a vaginal tampon containing antibiotics in the vaginal area.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW UP

The vaginal tampon was removed on the 1st postoperative day. Foley catheter was removed on the 4th postoperative day. Spontaneous diuresis was observed in the patient after catheter removed. PVR was not observed in the residual measurement. The patient's pain and lower urinary tract symptoms completely disappeared during the 2nd postoperative week. There was no recurrence or urinary system complaint at the 16 month postoperative follow-up visit.

DISCUSSION

Urethral prolapse is seen in two age groups: prepubertal girls and postmenopausal women (11). The fact that it is seen in older women shows that it may be acquired. Although urethral prolapse is well defined in the literature, the etiology and pathophysiology of the lesion remains unclear. UP has been hypothesized to be associated with estrogen deficiency and increased intra-abdominal pressure. Other causes of acquired UP include weakening of smooth muscle layers secondary to, chronic cough, chronic constipation, trauma, recurrent urinary tract infections, pelvic radiotherapy, and sexual abuse (12). UP is a rarely seen pathology, making differential diagnosis important. It is necessary to differentiate it from urethral caruncle, urethral diverticulum, ureterocele prolapse, and malignancy. In addition, poor hygiene and urinary tract infection can facilitate the development of the disease. At this point, the physical examination gains a special importance. In a study, it was found that only 21% of female patients with UP could be correctly diagnosed with pediatrician or emergancy phsician (13). From this point of view, it is a difficult disease to diagnose by physicians other than urologists. In UP, the normal mucosal tissue protrudes circularly from the external urethral meatus. The meatus is located in the center of the prolapse. Although the underlying pathology is similar, the appearance of the mucosa in urethral caruncle is different. Typically, mucosal tissue protrudes from the lower quadrant of the meatus. It does not completely surround the urethra, and the meatal orifice appears to be located upward. If there is uncertainty about malignancy in thrombosed and necrotic UP cases, biopsy is recommended. Cystoscopy can be performed to differentiate ureterocele or prolapse.

The reasons for admission vary according to age. Pediatric patients mostly present with urethral bleeding. Lower urinary tract symptoms, such as urinary retention, dysuria, urgency, and dyspareunia, are more dominant in postmenopausal women due to larger prolapses. In untreated cases, venous return is impaired due to the compression of the prolapse. The prolapse thromboses, and in more advanced cases, necrosis develops. The main complaints in thrombotic and necrotic prolapses are bleeding and pain.

Conservative approaches constitute the first step in treatment and management. . In medical treatment, there are sitz baths with antiseptic solution, topical estrogen and antibiotic application. Although its effectiveness is lower than surgical treatment, it is successfully used in patients who need anesthesia ( 13). In a cohort series of 21 pediatric patients, it was reported that sitz baths were the mainstay of treatment (14). In addition, topical estrogen creams have been shown to be beneficial in women who are thought to have estrogen deficiency. Preventing underlying causes and educating patients are also important in the treatment process. Conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as cough and constipation, should be corrected. In cases with acute urinary retention, a urinary catheter should be placed and the bladder should be emptied. The general consensus is to switch to surgical treatment in patients who do not benefit from a conservative approach. The conservative approach is of limited benefit in advanced cases with thrombosis and necrosis. In these cases, surgical management should be considered sooner. In our case, conservative management with sitz baths, topical estrogen cream, and topical antibiotics was tried first since the necrosis was limited. Because there was no benefit after 2 weeks of treatment, surgical excision was chosen.

The surgical technique is to excise the prolapsed mucosa and suture it to the intact urethral vestibule margin. We preferred a circular excision in our case. After determining the intact mucosal border, circular excision of the prolapsed mucosa was performed. Regarding the excision method, Shurtleff et al. described the four-quadrant technique (15). Post-surgical complications are rare. Complications are recurrence of prolapse, meatal stenosis, urethritis, urinary retention, and postoperative bleeding. The most frequently reported complications after excision are urethral stricture and postoperative urinary retention, but in the Hall et al. study, postoperative minor bleeding (25%) was reported to be the most common complication. Measurement of post-void residual in postoperative controls in patients undergoing surgery may prevent compression-related renal dysfunction in the future (10). Studies have reported that the success of surgical excision is high in UP cases. In pediatric patients, Yi Wei et al. 84%, Herzberg et al. They have reached 88% success rate (7,16). Ballouhey et al. reported that they did not encounter any recurrence in the 28-month follow-up after the operation (17). The most important advantage of operative treatment is that the patient recovers quickly and is discharged in a cured manner with a short hospitalization period. Its disadvantage is the increased risks associated with anesthesia, especially in elderly patients. Other treatment options in the literature are ligation over the urethral catheter, electrocoagulation, and cryosurgery (18). There is no clear view on the duration of the urethral catheter after the operation. While some authors remove the catheter on the first post-op day, some authors prefer to remove the catheter 3-5 days after the post-op. We decided to remove the catheter of our patient after 4 days because urinary retention developed beforehand.

CONCLUSION

UP is a rare disease that peaks in two age groups. Especially in prepubertal girls, when it is ignored, there may be delays in diagnosis.

Due to the limited number of publications in the literature about UP, the treatment process is controversial. Treatment is shaped according to the patient's age, symptoms and underlying causes. First of all, if there is an underlying cause, it should be corrected. In symptomatic patients, sitz baths and topical estrogen creams are the mainstay of treatment. Although conservative treatment is the first approach, in advanced cases, surgical treatment provides rapid recovery and can prevent complications related to obstruction. The surgical treatment of patients who are symptomatic who can tolerate anesthesia and who do not respond to medical treatment is the curative approach. Also according to the literature, surgical excision still remains the most definitive therapy about UP.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Olumide A, Olusegun AK, Babatola B. Urethral mucosa prolapse in an 18-year-old adolescent. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:231709. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary K, Panda A, Devasia A. Spontaneous irreducible urethral prolapse in a post-menopausal woman: a rare differential diagnosis of an intralabial mass. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(7):1067-1068. [CrossRef]

- Owens, S. B., & Morse, W. H. (1968). Prolapse of the female urethra in children. The Journal of Urology, 100(2), 171-174. [CrossRef]

- Velcek, F. T., Kugaczewski, J. T., Klotz, D. H., & Kottmeier, P. K. (1989). Surgical therapy for urethral prolapse in young girls. Adolescent and Pediatric Gynecology, 2(4), 230-233. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Parra JD, Cebrián Lostal JL, Lozano Uruñuel F, Alvarez BS (2010) Urethral prolapse in postmenopausical women. Actas Urol Esp 34(6):565–567.

- Eke N, Ugboma HA, Eke F (2005) Urethral prolapse in a woman in her reproductive age–a very rare occurrence. Niger J Med 14 (4):431–433.

- Anveden-Hertzberg L, Gauderer MWL, Elder JS. Urethral prolapse: an often misdiagnosed cause of urogenital bleeding in girls. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11(4):212-214. [CrossRef]

- Imai A, Horibe S, Tamaya T. Genital bleeding in premenarcheal children. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1995;49:41-5. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Garg G, Singh BP, Pandey S. Strangulated urethral prolapse in a postmenopausal woman presenting as acute urinary retention. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2018227040. [CrossRef]

- Hall ME, Oyesanya T, Cameron AP. Results of surgical excision of urethral prolapse in symptomatic patients. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017 Nov;36(8):2049-2055. [CrossRef]

- 13. Anveden-Hertzberg, L. O. T. T. A., Gauderer, M. W., & Elder, J. S. (1995). Urethral prolapse: an often misdiagnosed cause of urogenital bleeding in girls. Pediatric emergency care, 11(4), 212-214. [CrossRef]

- Holbrook C, Misra D. Surgical management of urethral prolapse in girls: 13 years’ experience. BJU Int. 2011;110:132–134. [CrossRef]

- Shurtleff BT, Barone JG. Urethral prolapse: four quadrant excisional technique. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2002;15(4):209-211. [CrossRef]

- Wei Y, Wu S-d, Lin T, He D-W, Li X-L, Wei G-H. Diagnosis and treatment of urethral prolapse in children: 16 years' experience with 89 Chinese girls. Arab J Urol. 2017;15(3):248-253. [CrossRef]

- Ballouhey Q, Galinier P, Gryn A, Grimaudo A, Pienkowski C, Fourcade L. Benefits of primary surgical resection for symptomatic urethral prolapse in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10(1):94-97. [CrossRef]

- Devine PC, Kessel HC. Surgical correction of urethral prolapse. J Urol. 1980;123:856-7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).