Submitted:

07 June 2023

Posted:

09 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ1

- : What are the benefits obtained from Andalusia’s tourism promotion budgets?

- RQ1

- RQ2: Can the Andalusia’s tourism promotion help to enhance tourism supply and demand?

- RQ1

- RQ3: What are the shortages of the tourism promotion in the eight provinces of Andalusia?

- RQ1

- RQ4: Can Andalusia’s tourism promotion campaigns be improved by DMOs?

- The need to study tourism promotion in tourism and aviation industries jointly.

- The lack of studies that covered this topic in tourism literature.

- The pandemic crisis and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have led to an increase in tourism promotion by DMOs and tour operators to restart tourism and aviation sectors.

- The attention to digital channels and their effective role in tourism promotion.

- Shed light on the tourism cities of Andalusia.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism Promotion a Marketing Tool to Increase the Number of Tourists and Passengers at Andalusian Provinces and Airports

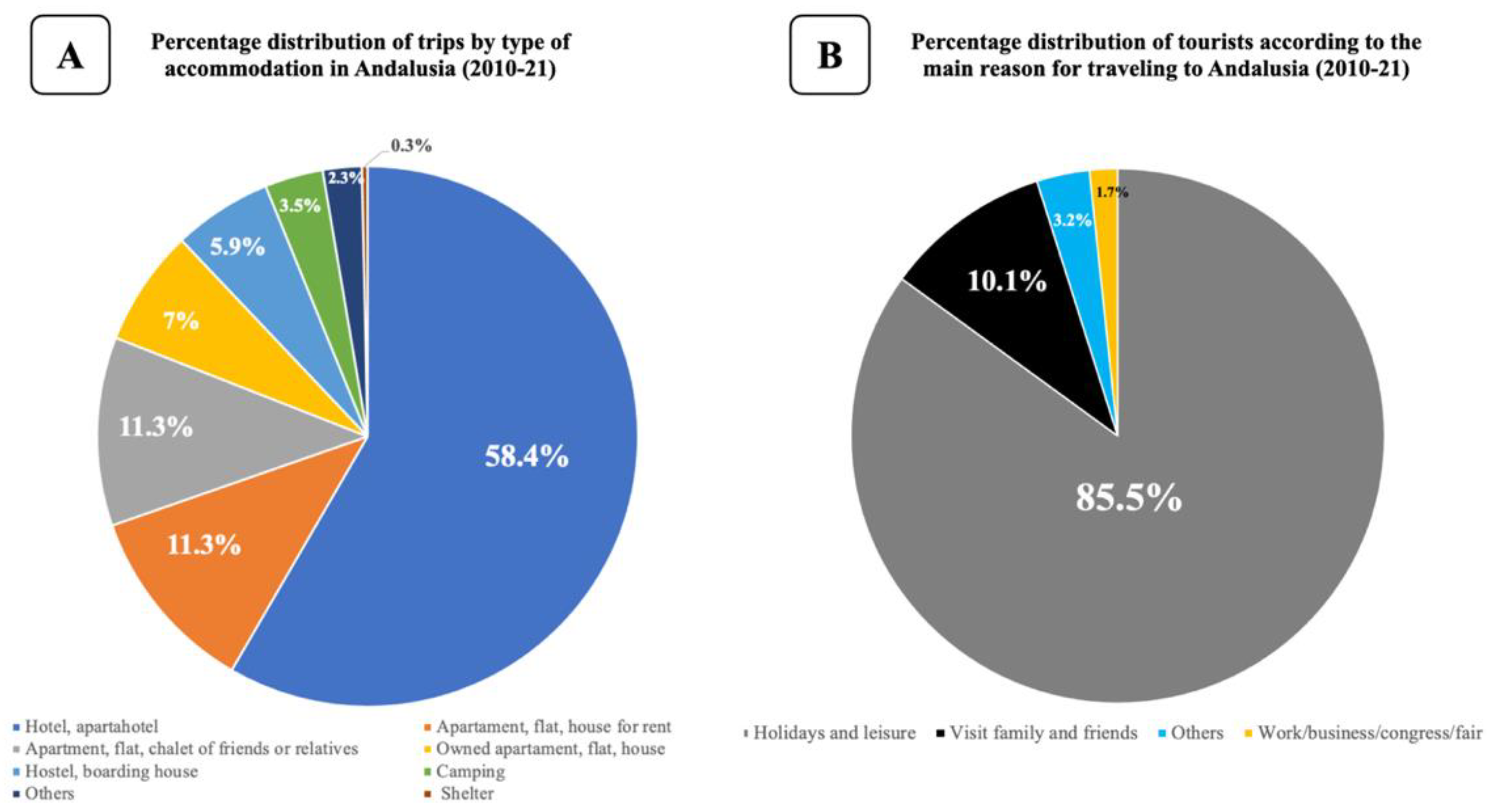

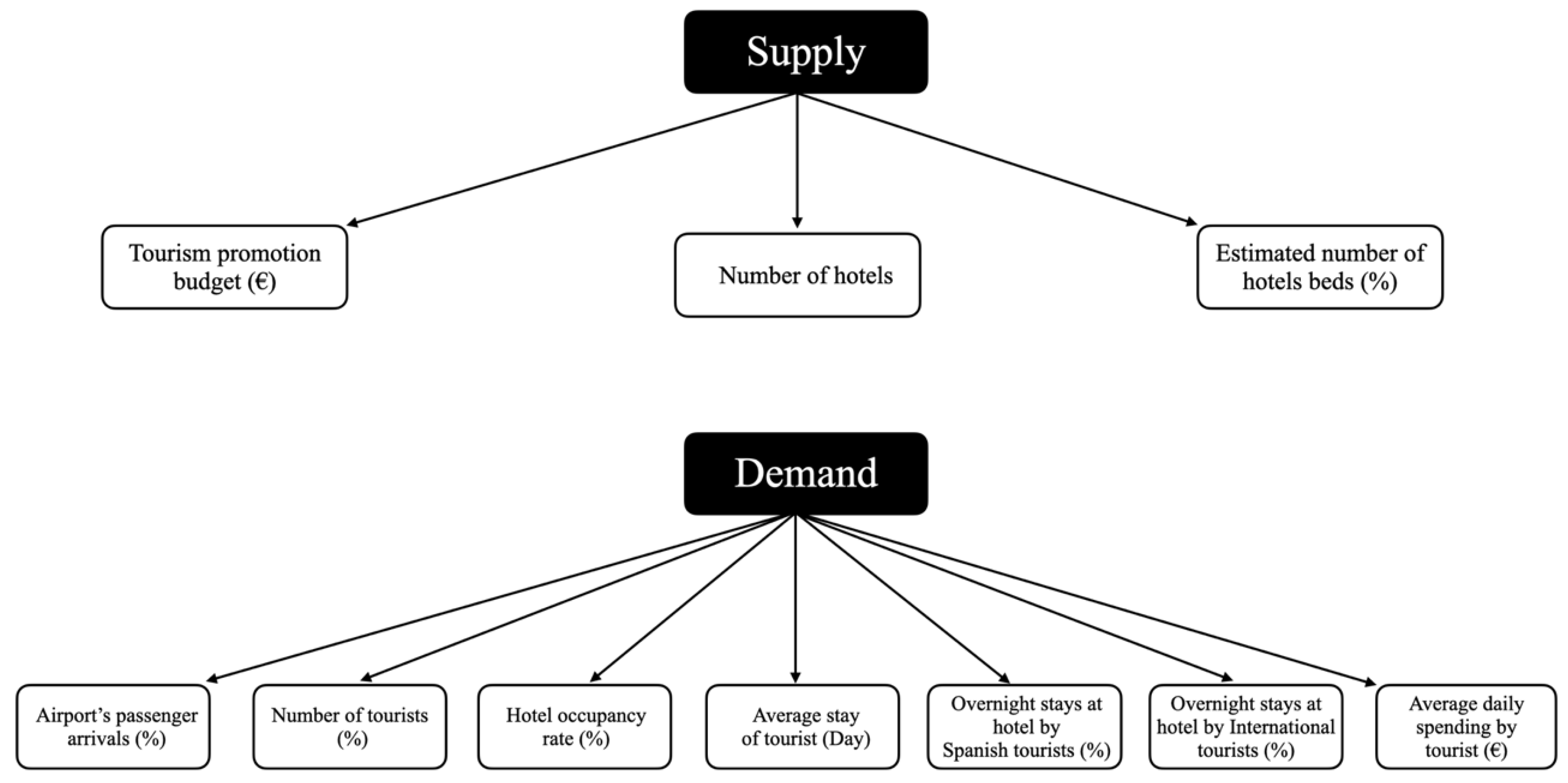

3.1. Supply Indicators

3.2. Demand Indicators

3. Methodology

4. Analysis and Results of Research

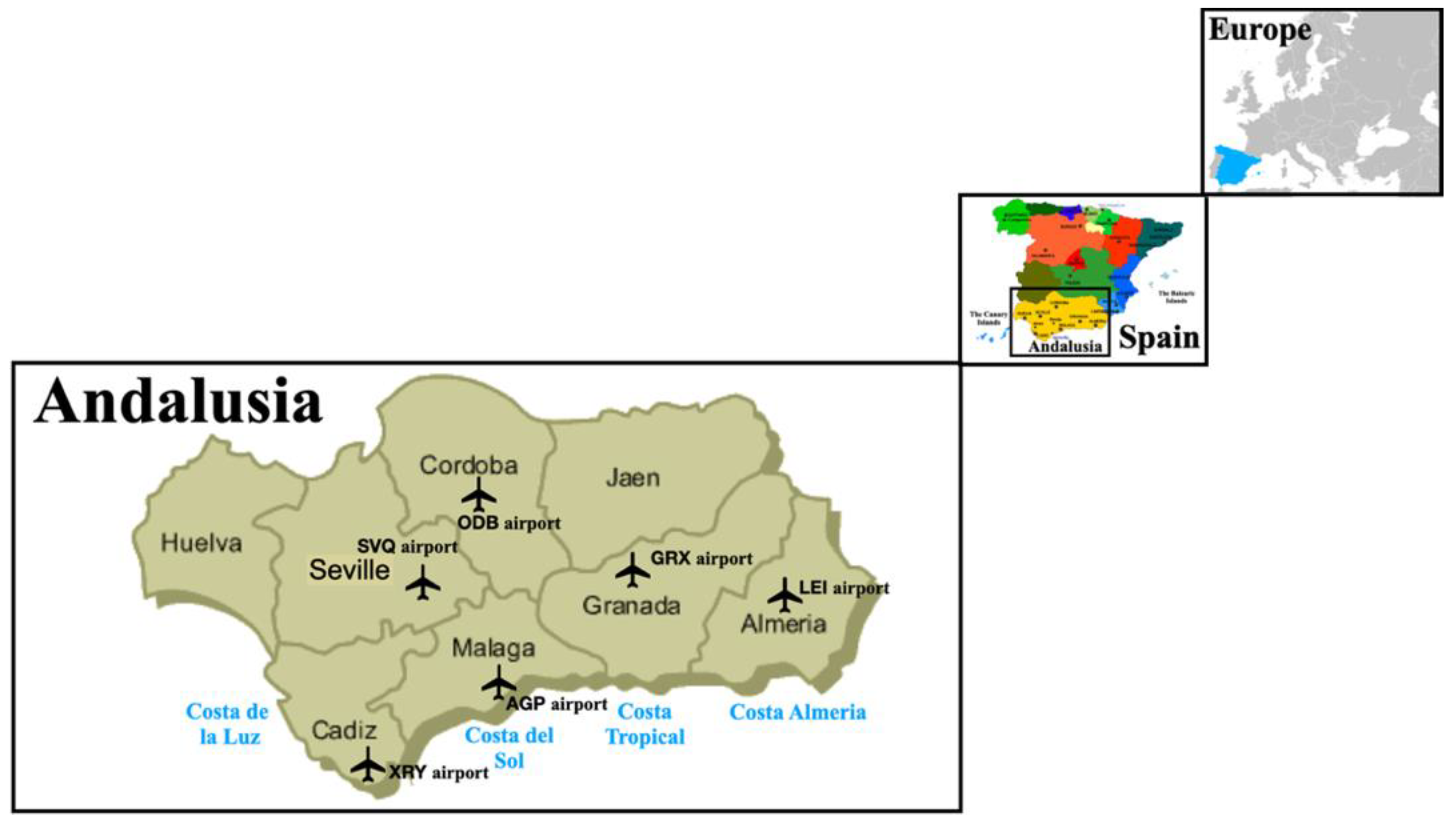

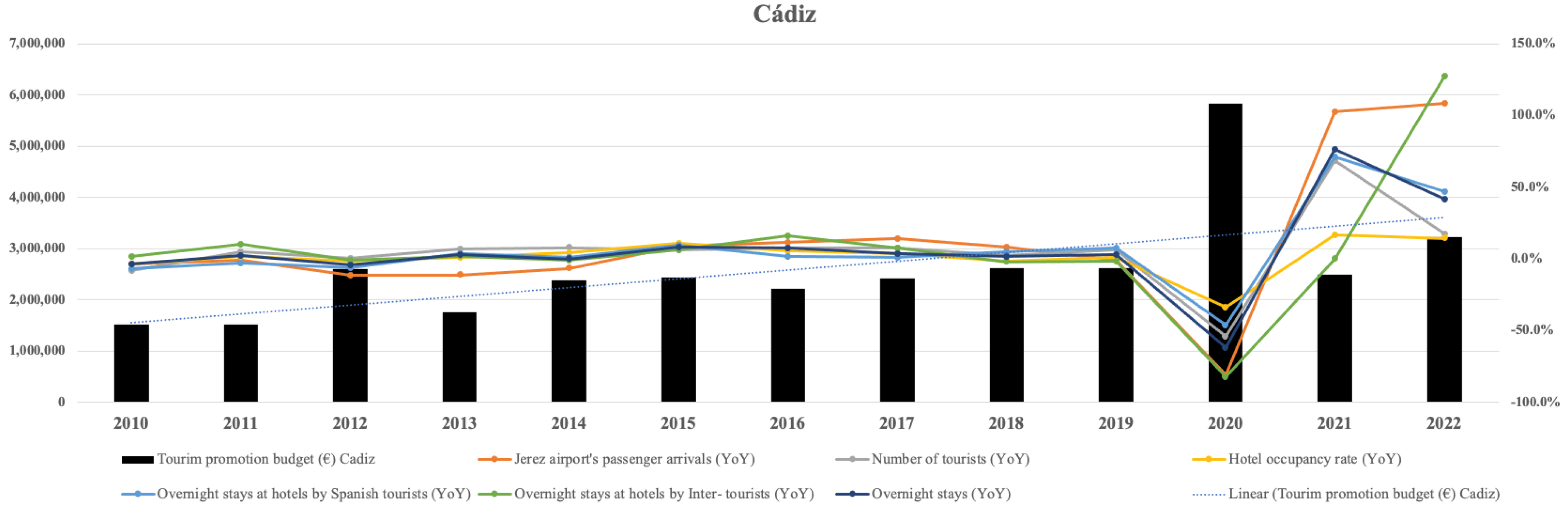

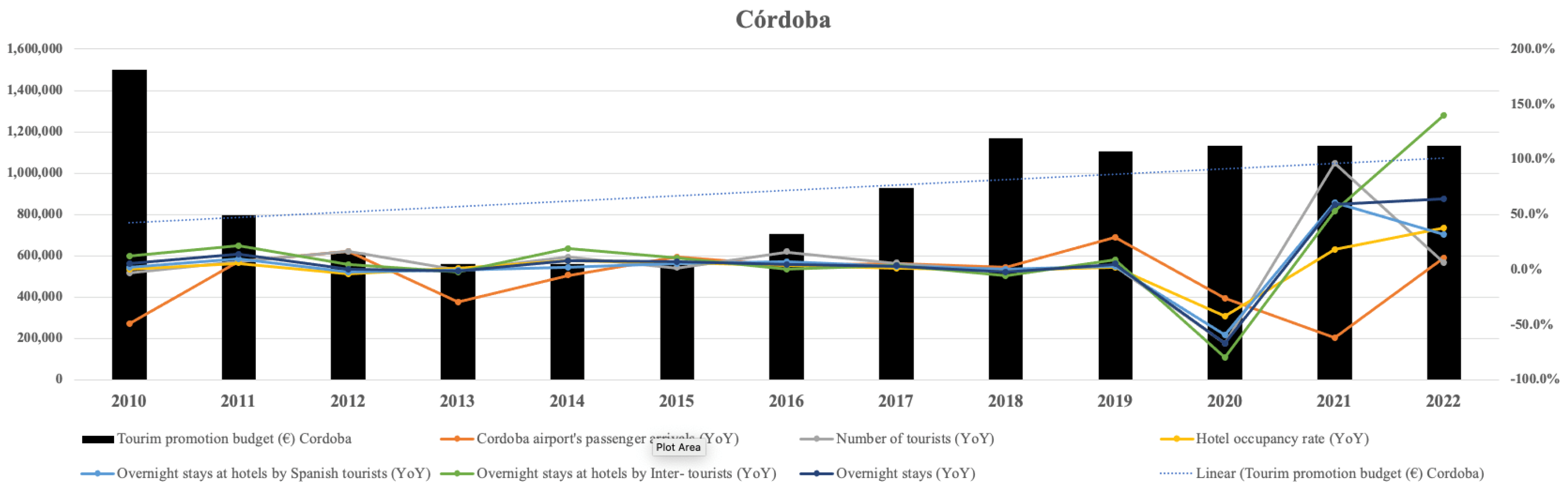

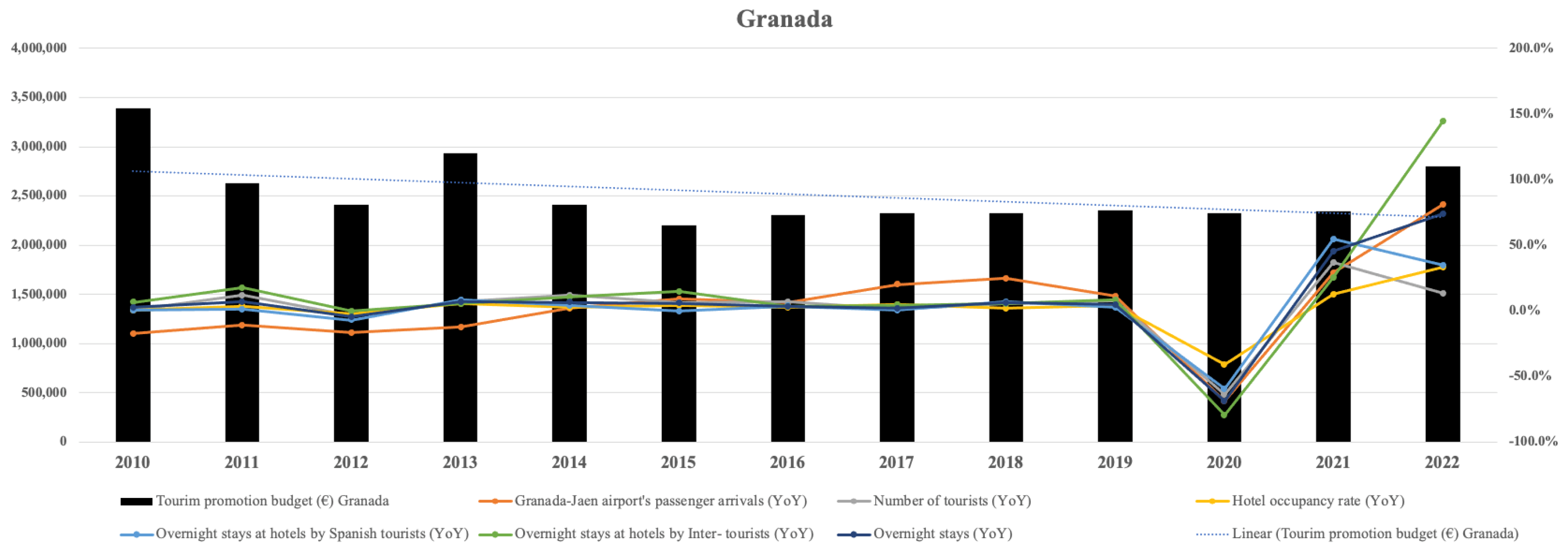

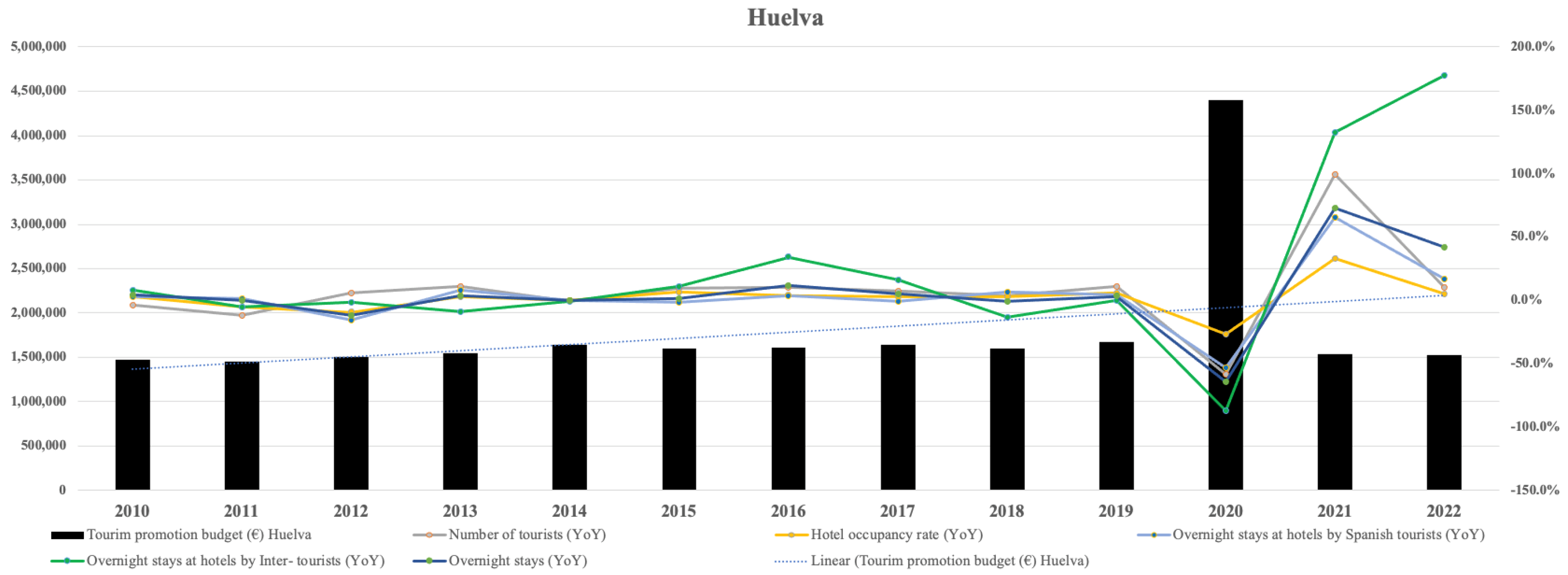

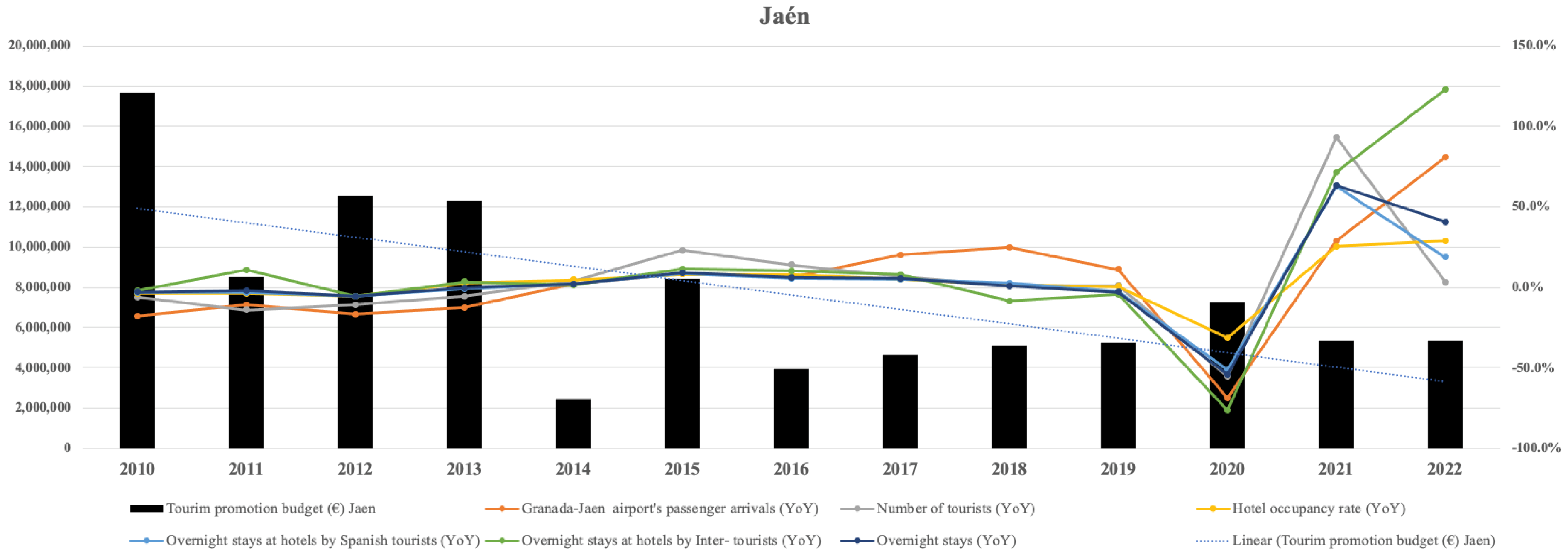

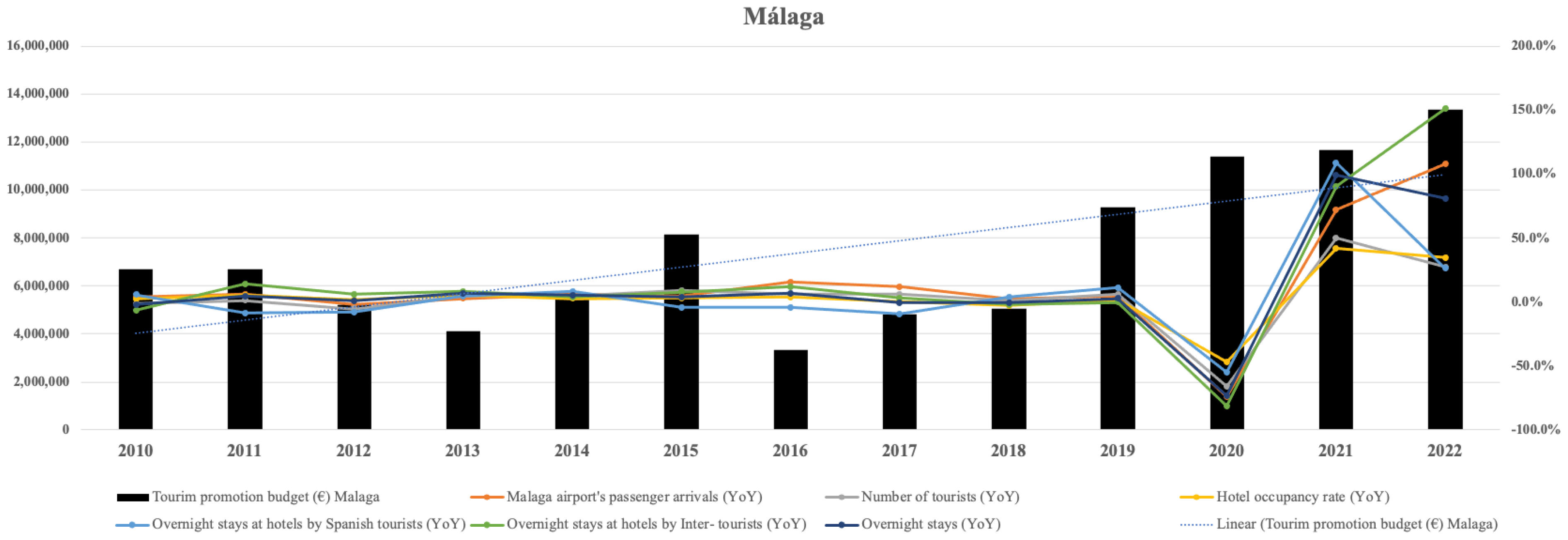

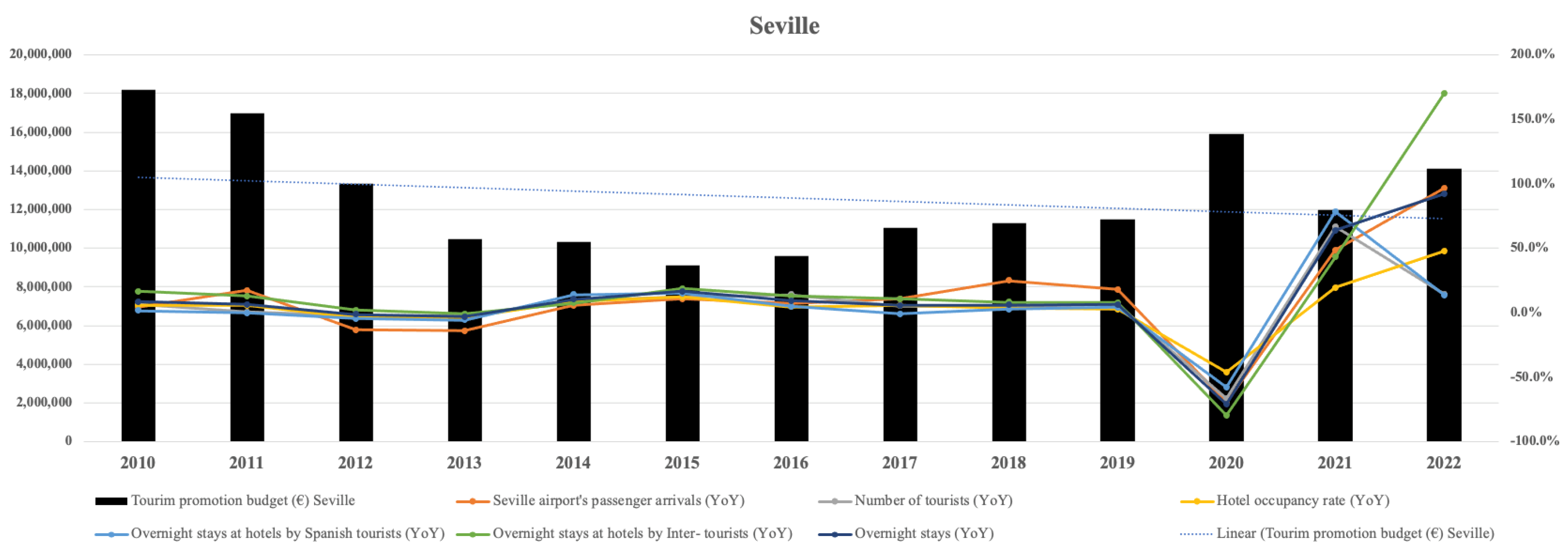

4.1. Present and Future of the Eight Provinces of Andalusia in Tourism Industry

- Tourism promotion budget (€).

- Number of passenger arrivals at Andalusia’s airports.

- Number of tourist (national and international).

- Hotel occupancy rate.

- Overnight stays at hotels by Spanish tourists.

- Overnight stays at hotels by international tourists.

- Total overnight stays at hotels (national and international).

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Number of hotels in Almería | Estimated number of hotel beds | Average stay of tourists (Days) | Average daily spending by tourist (€) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 192 | 29,989 | 8 | 52,8 |

| 2011 | 180 | 29,290 | 8,3 | 46,4 |

| 2012 | 177 | 28,023 | 9,6 | 44,2 |

| 2013 | 172 | 28,311 | 9,2 | 48,2 |

| 2014 | 186 | 28,498 | 8,8 | 52,4 |

| 2015 | 193 | 28,816 | 7,1 | 52,6 |

| 2016 | 195 | 29,665 | 7 | 56,6 |

| 2017 | 206 | 29,465 | 7,7 | 60,3 |

| 2018 | 204 | 29,973 | 7,7 | 61,5 |

| 2019 | 195 | 29,753 | 7,9 | 63,1 |

| 2020 | 137 | 15,976 | 7,6 | 60 |

| 2021 | 138 | 18,924 | 7,5 | 64,5 |

| 2022 | 179 | 38,916 | 7,3 | 66,8 |

| Number of hotels in Cádiz | Estimated number of hotel beds | Average stay of tourists (Days) | Average daily spending by tourist (€) | |

| 2010 | 421 | 39,261 | 7,7 | 69.8 |

| 2011 | 416 | 39,518 | 7,6 | 68,4 |

| 2012 | 416 | 38,322 | 8 | 66 |

| 2013 | 401 | 39,238 | 9,1 | 65,7 |

| 2014 | 388 | 37,639 | 8,6 | 66,5 |

| 2015 | 397 | 36,832 | 8,4 | 67,2 |

| 2016 | 406 | 37,603 | 6,9 | 70 |

| 2017 | 414 | 37,941 | 6,7 | 69,6 |

| 2018 | 429 | 39,193 | 6,4 | 71 |

| 2019 | 437 | 39,892 | 6,3 | 77,2 |

| 2020 | 316 | 25,156 | 7,7 | 72 |

| 2021 | 351 | 30,156 | 7,1 | 78,2 |

| 2022 | 408 | 38,916 | 6,9 | 84,5 |

| Number of hotels in Córdoba | Estimated number of hotel beds | Average stay of tourists (Days) | Average daily spending by tourist (€) | |

| 2010 | 184 | 9,915 | 3,2 | 64,7 |

| 2011 | 196 | 10,615 | 3,7 | 56,3 |

| 2012 | 197 | 11,034 | 3,8 | 52,5 |

| 2013 | 195 | 10,768 | 3,9 | 54,9 |

| 2014 | 192 | 10,812 | 3,9 | 57,6 |

| 2015 | 188 | 10,886 | 3,9 | 56 |

| 2016 | 196 | 11,048 | 3,7 | 59 |

| 2017 | 203 | 11,224 | 3,5 | 62,2 |

| 2018 | 198 | 11,045 | 3,3 | 63,9 |

| 2019 | 203 | 11,314 | 3,2 | 64,7 |

| 2020 | 139 | 7,192 | 3,1 | 65,2 |

| 2021 | 148 | 8,784 | 3 | 66,2 |

| 2022 | 183 | 10,936 | 3,2 | 72,6 |

| Number of hotels in Granada | Estimated number of hotel beds | Average stay of tourists (Days) | Average daily spending by tourist (€) | |

| 2010 | 408 | 29,013 | 5,3 | 72,4 |

| 2011 | 427 | 29,892 | 5,9 | 69,4 |

| 2012 | 407 | 29,168 | 5,5 | 63,7 |

| 2013 | 400 | 29,600 | 5 | 63,4 |

| 2014 | 417 | 30,677 | 5,1 | 62,1 |

| 2015 | 422 | 31,150 | 5,3 | 63,6 |

| 2016 | 418 | 31,227 | 5,4 | 65,7 |

| 2017 | 401 | 30,580 | 5,3 | 66,2 |

| 2018 | 413 | 31,878 | 5,1 | 70,4 |

| 2019 | 398 | 31,976 | 5,1 | 69,3 |

| 2020 | 235 | 18,567 | 5,3 | 63,9 |

| 2021 | 278 | 21,678 | 4,8 | 67,3 |

| 2022 | 361 | 29,478 | 4,3 | 73,4 |

| Number of hotels in Huelva | Estimated number of hotel beds | Average stay of tourists (Days) | Average daily spending by tourist (€) | |

| 2010 | 146 | 20,197 | 7,3 | 47,2 |

| 2011 | 150 | 21,298 | 8,1 | 46,9 |

| 2012 | 146 | 21,075 | 8,3 | 50,3 |

| 2013 | 143 | 20,899 | 7,9 | 54,7 |

| 2014 | 140 | 20,661 | 7 | 55 |

| 2015 | 140 | 19,427 | 7,5 | 51,8 |

| 2016 | 143 | 21,155 | 7,2 | 54,5 |

| 2017 | 148 | 21,484 | 7,9 | 58,2 |

| 2018 | 131 | 20,827 | 8,1 | 58,6 |

| 2019 | 133 | 20,575 | 7,9 | 56,1 |

| 2020 | 94 | 11,035 | 8,9 | 52,4 |

| 2021 | 110 | 12,693 | 7,5 | 58,7 |

| 2022 | 136 | 18,341 | 6,3 | 56,9 |

| Number of hotels in Jaén | Estimated number of hotel beds | Average stay of tourists (Days) | Average daily spending by tourist (€) | |

| 2010 | 183 | 8,842 | 3,7 | 85,2 |

| 2011 | 182 | 9,037 | 3,8 | 92,7 |

| 2012 | 183 | 9,046 | 2,7 | 98,5 |

| 2013 | 185 | 8,787 | 2,4 | 93,9 |

| 2014 | 177 | 8,560 | 2,4 | 96,8 |

| 2015 | 186 | 8,626 | 3 | 87,6 |

| 2016 | 178 | 8,440 | 2,7 | 92,1 |

| 2017 | 175 | 8,489 | 2,9 | 82,3 |

| 2018 | 175 | 8,453 | 2,6 | 85,2 |

| 2019 | 164 | 8,143 | 2,5 | 79,4 |

| 2020 | 117 | 5,922 | 2,5 | 73,3 |

| 2021 | 142 | 7,039 | 2,7 | 74,5 |

| 2022 | 161 | 8,015 | 2,6 | 78.7 |

| Number of hotels in Málaga | Estimated number of hotel beds | Average stay of tourists (Days) | Average daily spending by tourist (€) | |

| 2010 | 532 | 80,345 | 11,9 | 47,4 |

| 2011 | 536 | 79,478 | 11,4 | 51,5 |

| 2012 | 560 | 78,748 | 12 | 53,5 |

| 2013 | 546 | 79,737 | 10,7 | 55,9 |

| 2014 | 571 | 81,610 | 9,4 | 55,7 |

| 2015 | 561 | 81,550 | 9,7 | 55 |

| 2016 | 569 | 83,446 | 10 | 58 |

| 2017 | 555 | 83,344 | 9,3 | 61,9 |

| 2018 | 546 | 84,974 | 9,4 | 61,4 |

| 2019 | 548 | 85,967 | 9,2 | 63,3 |

| 2020 | 329 | 47,139 | 10,4 | 56,5 |

| 2021 | 401 | 59,870 | 8,3 | 65,4 |

| 2022 | 548 | 84,299 | 7,2 | 71,3 |

| Number of hotels in Seville | Estimated number of hotel beds | Average stay of tourists (Days) | Average daily spending by tourist (€) | |

| 2010 | 316 | 26,150 | 3,4 | 76 |

| 2011 | 317 | 26,256 | 3,3 | 73 |

| 2012 | 335 | 26,908 | 3,6 | 73,9 |

| 2013 | 336 | 27,091 | 3,5 | 74 |

| 2014 | 339 | 27,445 | 3,4 | 78,8 |

| 2015 | 350 | 28,597 | 3,5 | 82,7 |

| 2016 | 372 | 29,705 | 3,3 | 81,8 |

| 2017 | 366 | 29,805 | 3,4 | 78,9 |

| 2018 | 367 | 30,594 | 3,4 | 76 |

| 2019 | 385 | 31,646 | 3,3 | 73 |

| 2020 | 215 | 18,888 | 3,1 | 70,1 |

| 2021 | 250 | 23,494 | 3,8 | 72,5 |

| 2022 | 365 | 32,045 | 3,5 | 72,6 |

References

- Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; García-Pozo, A.; Marchante-Lara, M. (2011). The environment and competitive strategies in hotels in Andalusia. Env. Eng. Manag. J. 2011, 10, 1835–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. World Tourism Barometer. 2022, Available online:. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/wtobarometereng.2022.20.1.4 (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Moniche, A.; Gallego, I. Benefits of policy actor embeddedness for sustainable tourism indicators’ design: the case of Andalusia. J. Sus. Tour ahead- ahead-of-print. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilla-González, J.A. Does the Tourism Development of a Destination Determine Its Socioeconomic Development? An Analysis through Structural Equation Modeling in Medium-Sized Cities of Andalusia, Spain. Land. 2021, 10, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, P.; Romero, I.; Moreno, P. Measuring Tourism Sustainability: The Case of Andalusia. In: Ferrante, M., Fritz, O., Öner, Ö. (eds) Regional Science Perspectives on Tourism and Hospitality. Advances in Spatial Science. Springer, Cham. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. The impact of tourism promotion in tourist destinations: A bibliometric study. Inter. J.Tour. Ci. 2022, 8, 844–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Supporting jobs and economies through travel & tourism. Call for action to mitigate the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 and accelerate recovery. United Nations. 2020. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-04/COVID19_Recommendations_English_1.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- INE. Press Release. 2020. Available online: https://www.ine.es/en/daco/daco42/frontur/frontur1219_en.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- INE. Press Release. 2022. Available online: https://www.ine.es/en/daco/daco42/egatur/egatur0722_en.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Florido-Benítez, L. COVID-19 and BREXIT crisis: British Isles must not kill the goose that lays the golden egg of tourism. Gran Tour. 2022, 6, 61–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ruiz, E.; Ruiz-Romero, E. , Caballero-Galeote L. Recovery Measures for the Tourism Industry in Andalusia: Residents as Tourist Consumers. Economies. 2022, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.; Papatheodorou, A. Spatial evolution of airports: A new geographical economics perspective. The Eco. Air. Ope. Ad. Air. Eco. 2017, 6, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodorou, A. A review of research into air transport and tourism: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research Curated Collection on Air Transport and Tourism. A. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergori, A.S.; Arima, S. Low-cost carriers and tourism in the Italian regions: A segmented regression model. A. Tour. Res. 2022, 97, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IATA. Global Outlook for Air Transport. Times of Turbulence. 2022. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/airline-industry-economic-performance---june-2022---report/ (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Florido-Benítez, L.; del Alcázar, B. Airports as ambassadors of the marketing strategies of Spanish tourist destination. Gran Tour, 2020, 21, 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Chen, N.; Yuan, Q.; Yan, M. Evaluation of Tourism Development Potential on Provinces along the Belt and Road in China: Generation of a Comprehensive Index System. Land. 2021, 10, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B.; Sannassee, R.V. Marketing Promotion Financing and Tourism Development: The Case of Mauritius. J. Hos. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeral, E. Aspects to justify public tourism promotion: An economic perspective. Tour. Rev. 2006, 61, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P. The case for tourism promotion: An economic analysis. The Tour. Rev. 1992, 47, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Japutra, A.; Molinillo, S. Branded premiums in tourism destination promotion. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uner, M.M.; Karatepe, O.M.; Cavusgil, S.T.; Kucukergin, K.G. Does a highly standardized international advertising campaign contribute to the enhancement of destination image? Evidence from Turkey. J. Hos. Tour. In. Ahead-of-print. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, M.; Vernuccio, M. Challenges in Marketing Communications during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from Tourism and Hospitality Managers. Tour. Inter. Inter. J. 2022, 70, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Customer experience and engagement in tourism destinations: The experiential marketing perspective. J. Tra. Tour. Mar. 2020, 37, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktan. M.; Zaman, U.; Farías, P.; Raza, S.H.; Ogadimma EC. Real Bounce Forward: Experimental Evidence on Destination Crisis Marketing, Destination Trust, e-WOM and Global Expat’s Willingness to Travel during and after COVID-19. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jorge, J.; Suárez, C. Productivity, efficiency and its determinant factors in hotels. The Ser. In. J. 2014, 34, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, D. Emotional or rational? The congruence effect of message appeals and country stereotype on tourists’ international travel intentions. An. Tour. Re. 2022, 95, 103423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. The location of airport an added value to improve the number of visitors at US museums. Ca. Stu. Trans. Po. 2023, 11, 100961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B.; Sannassee, R.V.; Teeroovengadum, V.; Nunkoo, R. Air access liberalization, marketing promotion and tourism development. Inter. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. International mobile marketing: a satisfactory concept for companies and users in times of pandemic. Ben. Inter. J. 2021, 29, 1826–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, H.L. Amusement/Theme Parks and Resorts. In: Travel Industry Economics, Springer, Cham, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Warnock-Smith, D.; Christidis, P. European Union-Latin America/Caribbean air transport connectivity and competitiveness in different air policy contexts. J. Trans. Geo. 2021, 92, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AALEP. Tourism promotion in the EU and destination image. 2016. Available online: http://www.aalep.eu/tourism-promotion-eu-and-destination-image (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Nusair, K.; Alazri, H.; Alfarhan, U.F.; Al-Muharrami, S. Toward an understanding of segmentation strategies in international tourism marketing: the moderating effects of advertising media types and nationality. Re. Inter. Bu. Stra. 2022, 32, 346–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.C.; Evans, F.H.; Spilsbury, K.; Ciesielski, V.; Arrowsmith, C.; Wright, G. Market segments based on the dominant movement patterns of tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, E.; Pinto, C.; da Silva, D.S.; Capela, C. ’No country for old people’. Representations of the rural in the Portuguese tourism promotional campaigns. Ager: Revista de estudios sobre despoblación y desarrollo rural. J. Dep. Ru. Dev. Stu. 2014, 17, 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, M.; Suzuki, S.; Yamaguchi, Y. Effects of tourism promotion on COVID-19 spread: The case of the “Go To Travel” campaign in Japan. J. Trans. He. 2022, 26, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallathadka, L.K.; Pallathadka, H.; Singh, S.K. A Quantitative Investigation on the Role of Promotions and Marketing in Promoting Tourism in India. Inte. J. Res. Arts Hu. 2022, 2, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancausa Millán, M. G.; Millán Vázquez de la Torre, M. G.; Hernández Rojas, R. Analysis of the demand for gastronomic tourism in Andalusia (Spain). PloS one. 2021, 16, e0246377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Saed, B. , Upadhya, A.; Saleh, M.H. Role of airline promotion activities in destination branding: Case of Dubai vis-à-vis Emirates Airline. Euro. Res. Manag. Bu. Eco. 2020, 26, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.; Elshaer, I.; Saad, S. Tourism public-private partnership (PPP) projects: an exploratory-sequential approach. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva-Shapira, K.A. New Paradigms in City Tourism Management: Redefining Destination Promotion. J. Tra. Re. 2007, 46, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. , Mishra, J.M.; Rao, Y.V. Analysing tourism destination promotion through Facebook by Destination Marketing Organizations of India. Cu. Iss.Tour. 2022, 25, 1416–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreel, S.S.O.; Shuayb, A. Contribution of Social Media Platforms in Tourism Promotion. Sino. J. 2022, 1, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, U.A. The Need for the Identification of the Constituents of a Destination’s Tourist Image: A Promotion Segmentation Perspective. J. Pro. Ser. Mark. 1996, 14, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Bigné, E.; Andreu, L. Web-based national tourism promotion in the Mediterranean area. Tour. Rev. 2005, 60, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubes, D.R.; Vila, N.A.; Fraiz, B.J.A. Changes in Consumption Patterns and Tourist Promotion after the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Theo. App. Ele. Co. Res. 2021, 16, 1332–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix,A. ; Reinoso, N.G.; Vera, R. Participatory diagnosis of the tourism sector in managing the crisis caused by the pandemic (COVID-19). Re. Inter. Am. Tur. Ta. 2020, 16, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R.; Go, F.M.; Kumar, K. Promoting tourism destination image. J. Tra. Res. 2007, 46, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chiang, C.C. Is virtual reality technology an effective tool for tourism destination marketing? A flow perspective. J. Hos. Tour. Tec. 2022, 13, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, N.; Marušić, F. Tourism promotion of destination for Swedish emissive market. Ad. Eco. Bus. 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudensing, R.M.; Hughes, D.W.; Shields, M. Perceptions of tourism promotion and business challenges: A survey-based comparison of tourism businesses and promotion organizations. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.A. Trouble in the UK hotel sector? Inter. J. Con. Hos. Manag. 1997, 9, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, B.K.; Smiljanić, A.R.; Kežić, I. Role of tourism and hotel accommodation in house prices. A. Tour. Res. Em. In. 2022, 3, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, R.; Herrmann, O. Hotel roomrates under the influence of a large event: The Oktoberfest in Munich 2012. Inter. J. Hos. Manag. 2014, 39, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peypoch, N. , Randriamboarison, R.; Rsoamananjara, F.; Solnaandrasana, B. The length of stay of tourists in Madagascar. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IECA. Statistical Yearbook of Andalusia. 2021. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/badea/informe/anual?CodOper=b3_6&idNode=6100 (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Šimková, E.; Holzner, J. Motivation of tourism participants. Pro. So. Be. Sci. 2014, 158, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phucharoen, C.; Sangkaew, N. Does firm efficiency matter in the hospitality industry? An empirical examination of foreign demand for accommodation and hotel efficiency in Thailand. J. Tour. Ana. Re. Aná. Tur. 2020, 27, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xue, L.; Jones, T.E. Tourism-enhancing effect of world heritage sites: panacea or placebo? A meta-analysis. A. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé, A.; McAleer, M.; Ramos, V.; Rey-Maquieira, J. Modelling Air Passenger Arrivals in the Balearic and Canary Islands, Spain. Tour. Eco. 2009, 15, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. How Málaga’s airport contributes to promotes the establishment of companies in its hinterland and improves the local economy. Inter. J. Tour. Ci. 2021, 8, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. The effects of COVID-19 on Andalusian tourism and aviation sector. Tour. Re. 2021, 76, 829–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, M.C.; McAleer, M.; Slottje, D.; Ramos, V.; Rey-Maquieira, J. An alternative approach to estimating demand: neural network regression with conditional volatility for high frequency air passenger arrivals. J. Eco. 2008, 147, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postorino, M.N.; Mantecchini, L.; Malandri, C.; Paganelli, F. Airport Passenger Arrival Process: Estimation of Earliness Arrival Functions. Trans. Res. Pro. 2019, 37, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doganis, R. Flying off course. Airline Economics and Marketing, Routledge, UK. 2019.

- Florido-Benítez, L. The Safety-Hygiene Air Corridor between UK and Spain will coexist with COVID-19. Logistics. 2022, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, T.N.; Semeyutin, A.; Hubbard, N. Effects of enhanced air connectivity on the Kenyan tourism industry and their likely welfare implications. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastathopoulos, A.; Koritos, C.; Mertzanis, C. Effects of faith-based attributes on hotel prices: the case of halal services. Inter. J. Con. Hos. Manag. 2021, 33, 2839–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kester, J. International tourism trends in EU-28 member states: Current situation and forecasts for 2020-2025-2030 Report for the European Commission, Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry, prepared by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/international-tourism-trends-eu-28-member-states-current-situation-and-forecast-2020-2025-0_en (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Li, X.R. Public transport connectivity and intercity tourist flows. J. Tra. Res. 2019, 58, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, E.E. Sustainable hotel business practices. J. Re. Le. Pro. 2005, 5, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, N.; Raveh, A. Categorization of tourist attractions and the modeling of tourist cities: based on the co-plot method of multivariate analysis. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oklevik, O.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. , Grøtte, I.P.; McCabe, S. Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: a case study of activities in Fjord Norway. J. Sus. Tour. 2019, 27, 1804–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Witt, S.F. Tourism Demand Modelling and Forecasting: Modern Econometric Approaches; Pergamon, Oxford, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Jiménez, I.; Blake, A. Tourism demand modeling by propose of visit and nationality. J. Tra. Res. 2011, 50, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeral, E. Impacts of the world recession and economic crisis on tourism: forecasts and potential risks. J. Tra. Res. 2010, 49, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.C.; Song, H.; Shen, S. New developments in tourism and hotel demand modeling and forecasting. Inter. J. Con. Hos. Manag. 2017, 29, 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulos, G.; Hyndman, R.J. Modelling and forecasting Australian domestic tourism. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R.; Sainaghi, R. Mapping time series into networks as a tool to assess the complex dynamics of tourism systems. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanauskaitė, D.; Fioreb, M.; Stašysa, R. Use of E-marketing tools as communication management in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag.Pers. 2020, 34, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ruiz, D. , Elizondo-Salto, A.; Barroso-González, MdlO. Using social media in Tourist Sentiment Analysis: A Case Study of Andalusia during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Martínez, J.D.; Fernández-Morales, A. Cultural tourism as tourist segment for reducing seasonality in a coastal area: the case study of Andalusia. Cu. Iss.Tour. 2015, 18, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Aurioles, B. Seasonality in the peer-to-peer market for tourist accommodation: the case of Majorca. J. Hos.Tour. Ins. 2022, 5, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Aurioles, B. How the peer-to-peer market for tourist accommodation has responded to COVID-19. Inter. J. Tour. Ci. 2022, 8, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; García, M.N.; Viglia, G. , Nicolau, J.L. Competitors or Complements: A Meta-analysis of the Effect of Airbnb on Hotel Performance. J. Tra. Res. 2022, 61, 1508–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, L.; Li, X. What can hotels learn from the last recovery? Examining hotel occupancy rate and the guest experience. Inter. J. Hos. Manag. 2022, 103, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E.H.C.; Hu, J.; Chen, R. Monitoring and forecasting COVID-19 impacts on hotel occupancy rates with daily visitor arrivals and search queries. Cu. Iss. Tour. 2022, 25, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.R.; Liu, A.; Stienmetz, J.L.; Yu, Y. Timing matters: crisis severity and occupancy rate forecasts in social unrest periods. Inter. J. Con. Hos. Manag. 2021, 33, 2044–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, G. and Sandstrom, J. (2021), “The influence of occupancy changes on hotel market equilibrium”, Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, Vol. 62 No. 4, pp. 426-437. [CrossRef]

- La Moncloa. Government of Spain strengthens tourism with a Strategic Plan worth 4.26 billion euros. 2020. Available online: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/lang/en/presidente/news/Paginas/2020/20200618tourism-plan.aspx (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Gera, R.; Kumar, A. Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism Destination Resilience and Recovery: A Review of Future Research Directions. In: Dube, K., Nhamo, G., Swart, M. (eds) COVID-19, Tourist Destinations and Prospects for Recovery. Springer, Cham. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nyns, S.; Schmitz, S. Using mobile data to evaluate unobserved tourist overnight stays. Tour. Manag. 2022, 89, 104453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ozanne, L. A systematic review of peer-to-peer (P2P) accommodation sharing research from 2010 to 2016: Progress and prospects from the multi-level perspective. J. Hos. Mar. Manag. 2018, 27, 649–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrane, C. Analyzing Tourists’ Length of Stay at Destinations with Survival Models: A Constructive Critique Based on a Case Study. Tour. Manag, 2012, 33, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling,, S. , Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Global trends in length of stay: implications for destination management and climate change. J. Sus. Tour. 2018, 26, 2087–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.E. D O., Ramos, V.; Rey-Maquieira, J. Length of stay at multiple destinations of tourism trips in Brazil. J. Tra. Res. 2015, 54, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, N.P.; Jorgenson, J.; Boley, B. Are sustainable tourists a higher spending market? Tour. Manag., 2016, 54, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsız, O.; Leoni, V. ; Akova, Determinants of tourists’ length of stay in cultural destination: one-night vs longer stays. J. Hos. Tour. In. 2022, 5, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilton, J.J.; Nickerson, N.P. Collecting and Using Visitor Spending Data. J. Tra. Res. 2006, 45, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurdana, D.S.; Frleta, D.S. Satisfaction as a determinant of tourist expenditure. Cu. Iss. Tour. 2017, 20, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrane, C.; Farstad, E. Tourists’ length of stay: the case of international summer visitors to Norway. Tour. Eco. 2012, 18, 1069–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.A.; Juaneda, S.C. Tourist expenditure for mass tourism markets. A. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiper, N. The framework of tourism: Towards a definition of tourism, tourist, and the tourist industry. A. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, R.; Nayak, D. Microeconomic determinants of domestic tourism expenditure in India. International J.Tour. Po. 2023, 13, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, H.D.; Jopp, R.; Gholipour, H.F.; Lim, W.M.; Lim, A.L.; Wee, L.L.M. Information source and tourist expenditure: evidence from Sarawak, Malaysia. Cu. Iss.Tour. 2022, 3, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbruzzo, A.; Brida, J.G.; Scuderi, R. Determinants of individual tourist expenditure as a network: Empirical findings from Uruguay. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrión-Gavilán, M.D.; Benítez-Márquez, M.D.; Mora-Rangel, E.O. Spatial distribution of tourism supply in Andalusia. Tour. Manag. Pers. 2015, 15, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, M.G.; Sánchez-Ollero, J.L.; Millán, M.G. Ham Tourism in Andalusia: An Untapped Opportunity in the Rural Environment. Foods. 2022, 11, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Andalucía. Todas las playas andaluzas, aptas para el baño. 2018. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/presidencia/portavoz/salud/133964/ConsejeriaSalud/playas/aguasdebano/calidad/Andalucia (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- AENA. Air traffic statistics 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.aena.es/es/estadisticas/informes-anuales.html (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Junta de Andalucía. Andalusia will tour eight European cities in a direct-to-consumer promotion to recover international tourism. 2021. Available online: https://www.turismoandaluz.com/noticias/andalucia-recorrera-ocho-ciudades-europeas-en-una-promocion-directa-al-consumidor-para (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Junta de Andalucía. Presupuesto de la Comunidad Autónoma de Andalucía. 2023. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/transparencia/informacion-economica-presupuestaria/visor-presupuestos.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Hosteltur. La Junta de Andalucía destina un presupuesto de 83 M € a Turismo. 2019. Available online: https://www.hosteltur.com/129287_la-junta-de-andalucia-destina-un-presupuesto-de-83-m-a-turismo.html (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- IECA. Statistical Yearbook of Andalusia. 2023. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/badea/informe/anual?CodOper=b3_6&idNode=6100 (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- IECA. Tourism demand. 2021. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/badea/informe/anual?CodOper=b3_6&idNode=6100 (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- INE. Press Release. 2022. Available online: https://www.ine.es/en/daco/daco42/frontur/frontur1219_en.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- INE. Press Release. 2022. Available online: https://www.ine.es/en/daco/daco42/egatur/egatur0722_en.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Rita, P.; Moutinho, L. Allocating a Promotion Budget. Inter. J.Co. Hos. Manag. 1992, 4, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, L.; Crouch, G.I. Promoting destinations: An exploratory study of publicity programmes used by national tourism organizations. J. Va. Mar. 1992, 9, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITB Berlin. Andalusia enjoyed strong growth in tourist arrivals in Q1. 2022. Available online: https://news.itb.com/topics/news/andalusia-growth62022/ (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Lu, S.; Cheng, G.; Li, T.; Xue, L.; Liu, X.; Huang, J.; Liu, G. Quantifying supply chain food loss in China with primary data: A large-scale, field-survey based analysis for staple food, vegetables, and fruits. Res., Con. Re. 2022, 177, 106006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabianski J., S. Primary and secondary data: Concepts, concerns, errors, and issues. The Appra. J. 2003, 71, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio, N.; de Almeida, A.; Nunes, L. Big Data in Hotel Revenue Management: Exploring Cancellation Drivers to Gain Insights Into Booking Cancellation Behavior. Cor. Hos. Qua. 2019, 60, 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Gretzel, U. Influencer marketing for tourism destinations: Lessons from a mature destination. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2020: Proceedings of the International Conference in Surrey, United Kingdom, January 08–10.; 2020; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, M.; Bellia, C.; Giurdanella, C.; Columba, P.; Chironi, S. Digital influencers, food and tourism—A new model of open innovation for businesses in the Ho. Re. Ca. sector. J. In. Tec. Mar. Co. 2022, 8, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U. (2018) Influencer marketing in travel and tourism. In: Sigala M, Gretzel U (eds) Advances in social media for travel, tourism, and hospitality: new perspectives, practice and cases. Routledge, New York, 147–156.

- Hughes, H.; Allen, D. Cultural tourism in Central and Eastern Europe: The views of ‘induced image formation agents. Tour. Manag. 2017, 26, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Japutra, A. Factors influencing domestic tourist attendance at cultural attractions in Andalusia, Spain. J. Des. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrades-Caldito, L.; Sánchez-Rivero, M. ,Pulido-Fernández, J.I. Differentiating Competitiveness through Tourism Image Assessment: An Application to Andalusia (Spain). J. Tra. Res. 2013, 52, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IATA. Airports codes. 2023. Available online: https://www.iata.org/en/youandiata/airports/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Dube, K. COVID-19 vaccine-induced recovery and the implications of vaccine apartheid on the global tourism industry. Phy. Che. Ear. 2022, 126, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y. Benchmarking the recovery of air travel demands for US airports during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Trans. Res. Inter. Per, 2022, 13, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, B.; Rigall-I-Torrent, R.; Ballester, R.; Benavente, J.; Ferreira, O. Coastal erosion perception and willingness to pay for beach management (Cádiz, Spain). J. Co. Con. 2015, 19, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, J.; Moreno, P.; Tejada, P. The tourism SMEs in the global value chains: the case of Andalusia. Ser. Bu. 2008, 2, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, AT. , Randerson, P.; Di Giacomo, C.; Anfuso, G.; Macias, A.: Perales, J.A. Distribution of beach litter along the coastline of Cádiz, Spain. Ma. Po. Bu. 2016, 107, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.L. Understanding consumers’ preferences for green hotels – the roles of perceived green benefits and environmental knowledge. J. Hos. Tour. In. ahead-of-print. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, M.; Mikulić, J. Building brand equity through communication consistency in luxury hotels: an impact-asymmetry analysis. J. Hos. Tour. In. 2020, 3, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granada. Provincial Tourism Board of Granada. 2022. Available online: https://www.turgranada.es/en/provincial-tourism-board-granada/ (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- González, R.; Medina, J. Cultural tourism, and urban management in northwestern Spain: the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Tour. Geo. 2003, 5, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñán-Ludeña, M.S.; de Campos, L.M. Analysing tourist data on Twitter: a case study in the province of Granada at Spain. J. Hos. Tour. In. 2022, 5, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante-Moro, A.; Infante-Moro, J.C.; Gallardo-Pérez, J.; Martínez-López, F.J.; García-Ordaz, M. Training needs in digital skills in the tourism sector of Huelva”, 2021 XI International Conference on Virtual Campus. 2021, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- NECSTouR. Balance of the tourism season in 2021 in Andalusia. 2021. Available online: https://necstour.eu/good-practices/balance-tourism-season-2021-andalusia (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Aguado-Correa, F.; Rabadán-Martín, I.; Padilla-Garrido, N. COVID-19 and the accommodation sector: first measures, and online communications strategies. A multiple case study in a Spanish province. Inv. Tur. 2022, 24, 172–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Sanchez, A.; Dredge, D. Huelva, the Light: Enlightening the process of branding and place identity development, In Dredge, D. & Jenkins, J. (eds.) Stories of Practice: Tourism Planning and Policy, Ashgate, 2021.

- Figueroa, C.M.C. La competitividad del destino a través de la lente de la promoción: Huelva la Luz y Huelva más allá. In II Congreso Internacional Ciudades Creativas: actas. Icono 14 Asociación Científica, 2011, 1648–1659.

- Tregua, M. , D’Auria, A.; Marano-Marcolini, C. Oleotourism: Local Actors for Local Tourism Development. Sustainability. 2018, 10, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano-Marcolini, C.; D’Auria, A.; Tregua, M. Oleotourism Development in Jaén, Spain. Camilleri, M.A. (Ed.) The Branding of Tourist Destinations: Theoretical and Empirical Insights, Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, 2018, 147–168.

- CES. Annual report of socioeconomic of the province of Jaén. 2020. Available online: https://www.dipujaen.es/export/sites/default/galerias/galeriaDescargas/diputacion/dipujaen/CES/otras-imagenes/Resu_Memoria_2020_completa_final.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Casado-Montilla, J.; Carrillo-Hidalgo., I.; Durán-Román, J.L. Does type of accommodation influence tourist behavior? Hotel accommodation vs. rural accommodation. Anatolia 2023, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio-Martin, J.L. Estimating the Tourism Demand Impact of Public Infrastructure Investment: The Case of Málaga Airport Expansion. Tour. Eco. 2016, 22, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. Málaga Costa del Sol airport and its new conceptualization of hinterland. Tour. Cri. 2021, 2, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, N.; Cañas, J.A. Waiting for tourists in southern Spain’s ghost coast. 2020. Available online: https://english.elpais.com/economy_and_business/2020-09-24/waiting-for-tourists-in-southern-spains-ghost-coast.html (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Doerr, L.; Dorn, F.; Gaebler, S.; Potrafke, N. How new airport infrastructure promotes tourism: evidence from a synthetic control approach in German regions. Re. Stu. 2020, 54, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, N.; Graham, A. Airport Marketing, Routledge, New York. 2013.

- Barke, M.; Newton, M. Promoting sustainable tourism in an urban context: Recent developments in Málaga city, Andalusia. J. Sus. Tour. 1995, 3, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

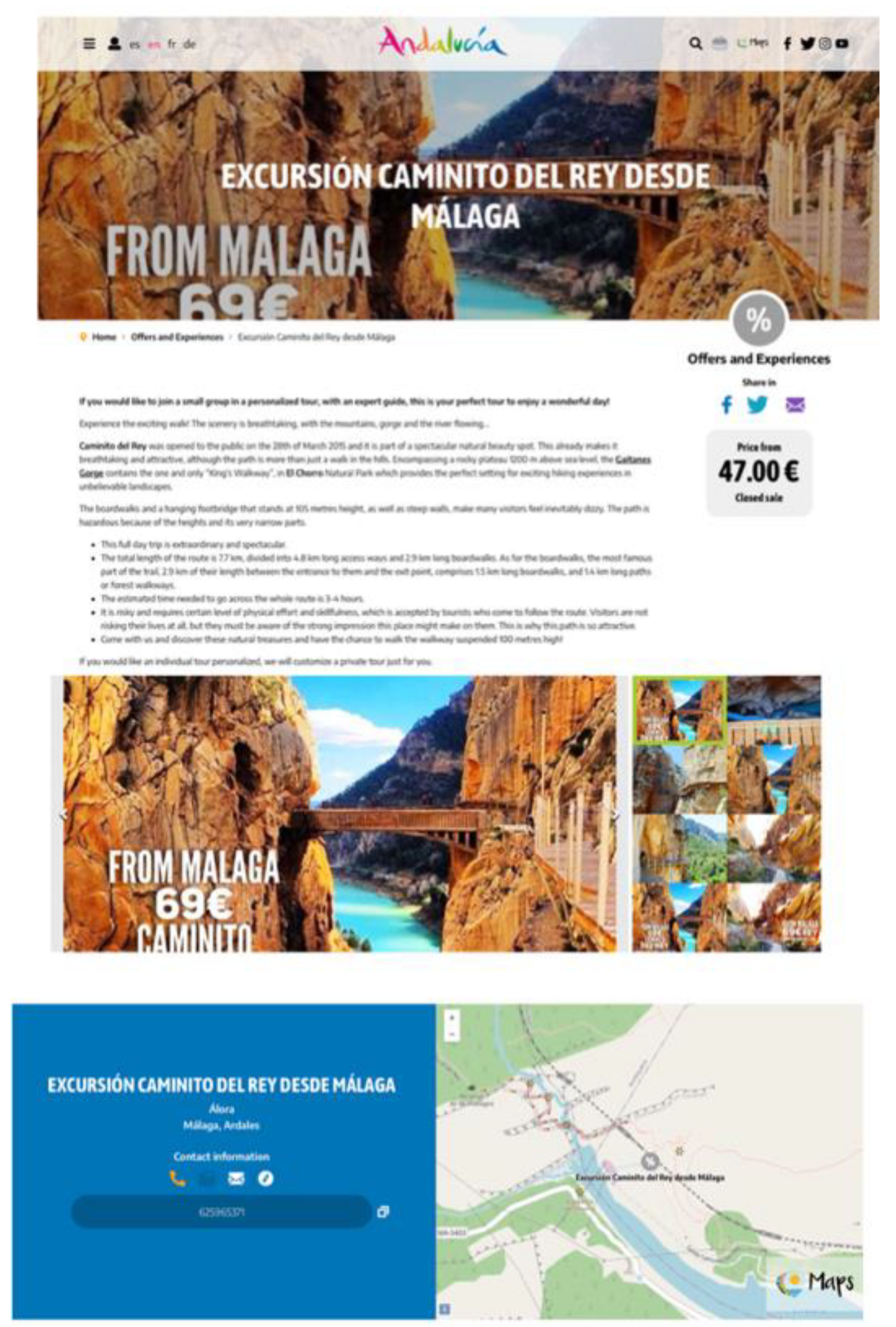

- Andalucía.org. Offers and Experiences – Excursión Caminito del Rey desde Málaga.2022. Available online: https://www.andalucia.org/en/deals-excursion-caminito-del-rey-desde-malaga (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Pisonero, R.D. Actuation and Promotion Mechanisms of Urban Tourism: The Case of Seville (Spain). Turizam. 2011, 15, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moragas, R. Patrimonio, Turismo y Ciudad. Bo.Ins. An. Pa. 2004, 9, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. Seville Airport: A Success of good relationship management and Interoperability in the improvement of air connectivity. Re. Tur. Es. Prá. 2020, 5, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Thimm, T. The Flamenco Factor in Destination Marketing: Interdependencies of Creative Industries and Tourism —the Case of Seville. J.Tra. Tour.Mar. 2014, 31, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Quintero, A.M.D. Understanding the Effect of Place Image and Knowledge of Tourism on Residents’ Attitudes Towards Tourism and Their Word-of-Mouth Intentions: Evidence from Seville, Spain. Tour. Pla. De. 2022, 5, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, E. From 9/11 through Katrina to Covid-19: crisis recovery campaigns for American destinations. Cu. Iss. Tour. 2021, 24, 2875–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilson, J.; KHS; APR. Fellow PRSA (2005) Religious-Spiritual Tourism and Promotional Campaigning: A Church-State Partnership for St. James and Spain. J. Hos. Le. Mar. 2005, 12, 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narváez, I.C.; Zambrana, J.M.V. How to translate culture-specific items: a case study of tourist promotion campaign by Turespaña. J. Spe. Tra. 2014, 21, 71–112. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski-Strzyżowski, D.J. Promotional Activities of Selected National Tourism Organizations (NTOs) in the Light of Sustainable Tourism (Including Sustainable Transport). Sustainability. 2022, 14, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubes, D.R.; Vila, N.A.; Fraiz, B.J.A. Changes in Consumption Patterns and Tourist Promotion after the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. The.App. Ele. Co. Re. 2021, 16, 1332–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, K.; Eichelberger, S.; Peters, M. Tourism organizations’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic: an investigation of the lockdown period. Cu. Iss. To. 2022, 25, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. A review of the UK’s tourism recovery plans post COVID-19. Athe. J. Tour. 2022, 9, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. (2021), “Sustainable tourism in urban destinations”, Inter. J. Tour. Ci. 2021, 7, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H. The efficiency of government promotion of inbound tourism: The case of Australia. Eco. Mo. 2012, 29, 2711–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katircioglu, S.T. International tourism, higher education and economic growth: the case of North Cyprus. The Wo. Eco. 2010, 33, 1955–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenete, M.A.; Delgado, M.-C.; Villegas, P. Impact assessment of Covid-19 on the tourism sector in Andalusia: an economic approach. Cu. Iss.Tour. 2022, 25, 2029–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, M.J. , de Magalhães, S. T.; Rodrigues, C.; Marques, S. Acceptance criteria in a promotional tourism demarketing plan. Pro, Com, Sci, 2017, 121, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Lata, S. YouTube channels influence on destination visit intentions: An empirical analysis on the base of information adoption model. J. In. Bu. Res. 2020, 12, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).