Submitted:

06 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1. Materials and Methods

1.1. Search Strategy

1.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Studies

1.2. Study Selection, Quality Assessment, and Data Extraction

1.2.1. Selection Process

1.2.2. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

1.2.3. Data Extraction Process (selection and coding)

1.3. Data Synthesis

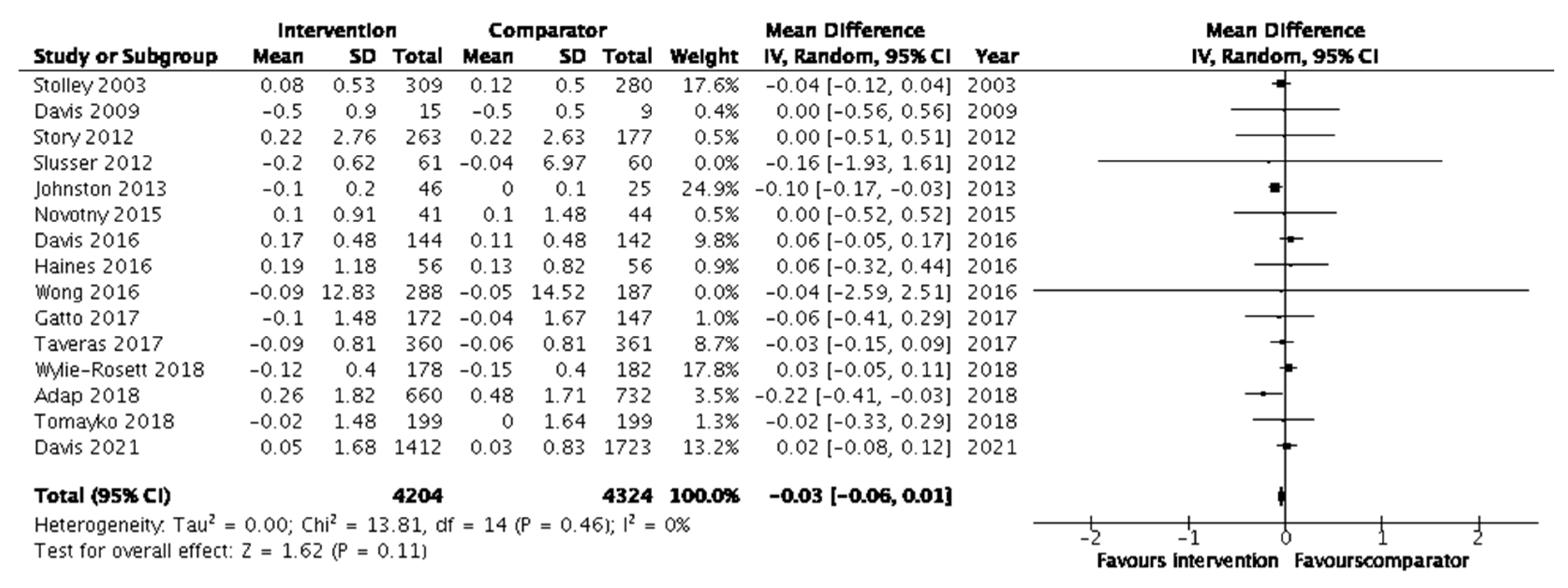

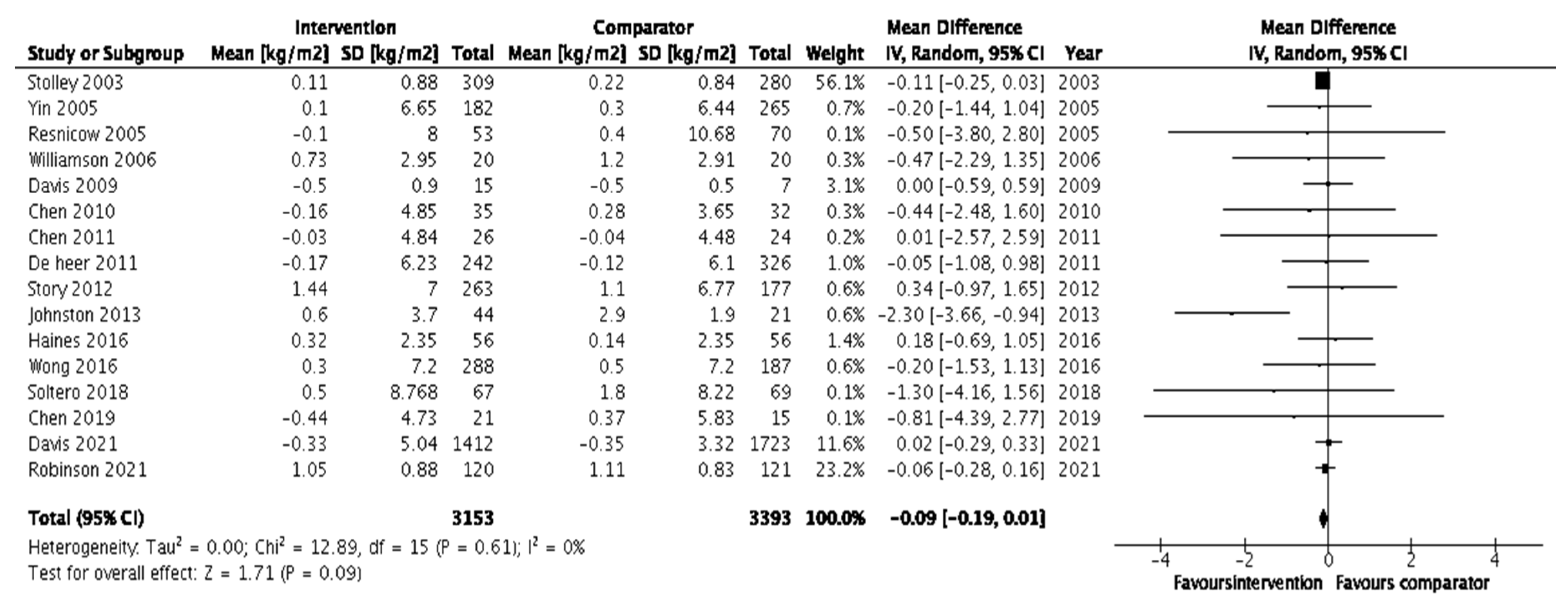

1.4. Statistical Analysis

2. Results

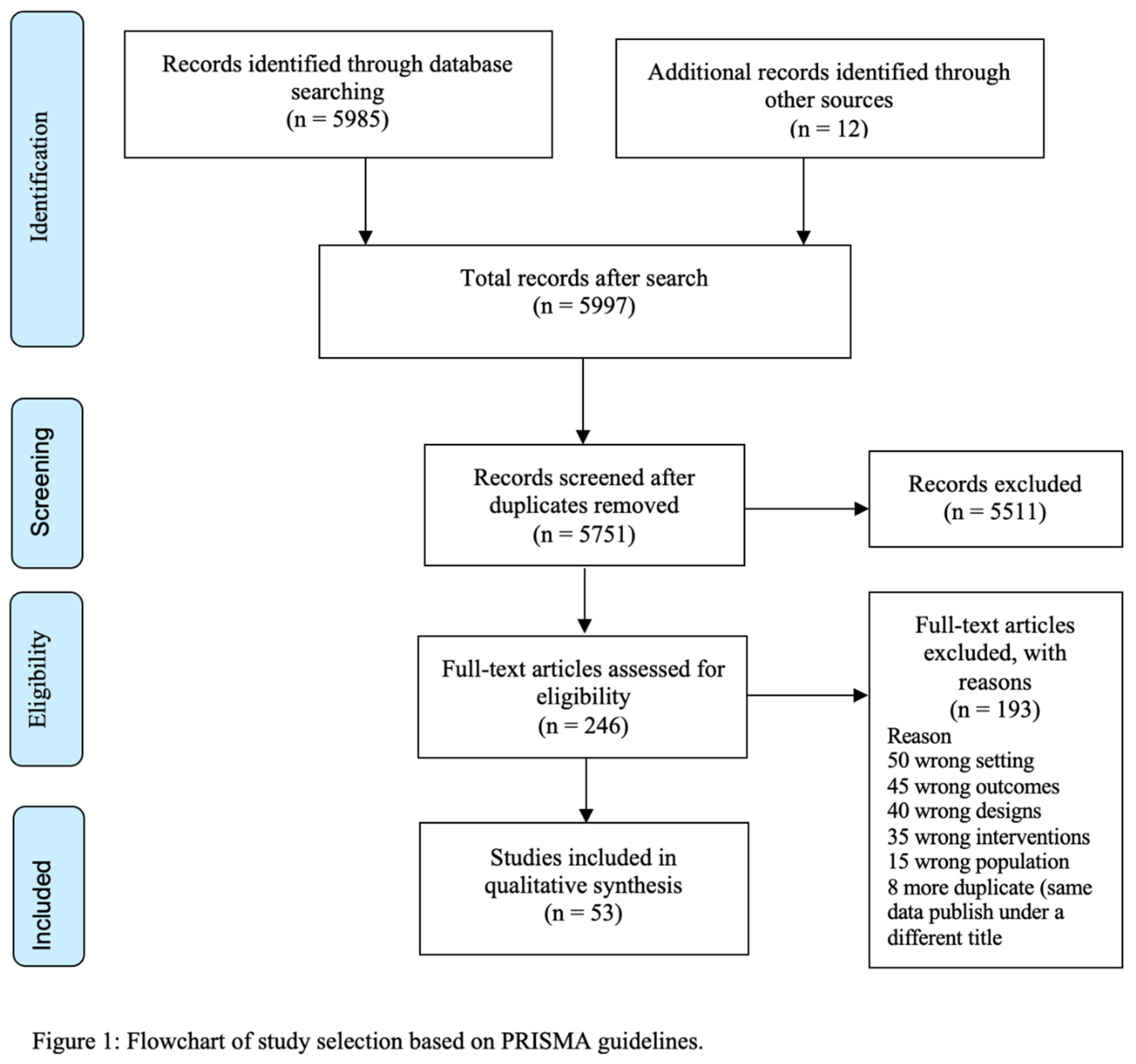

2.1. Study Selection

2.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

| Study | Study design, setting and sample | Study participant (sample, ethnicity, and age) | Intervention (Type, duration, frequency, and theory base) | Comparator control | Main results | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yli-Piipari et al., 2018, USA [50]. | Quasi-experimental one-arm pre- and post-test design, conducted in a primary care setting. |

22 high-risk Hispanics children, with overweight and obesity (BMI ≥85th United States CDC BMI percentile for age and sex); Mean age 11.7 years; 27% female. |

12 weeks PA and nutrition behaviour programme: Twice per week 60 min (total of 24 hours) of moderate-to-vigorous intensity Boxing exercise, a 12 hours of nutrition education for guardians, and a 30-min paediatrician appointment |

None | BMI (kg/m2) change: t(15)=-2. BMI% change: t(15)=-2.53, p = 0.023, d = 0.20.20, p=0.044, d=0.5. BM z score change: t(15)=-3.64, p=0.002, d=0.19. WC change: t(17)=-2.57, p=0.020. Fasting glucose change: t (15) = -6.43, p < 0.001, d = 1.67. |

In Hispanic minorities with severe obesity, the multicomponent supervised exercise and nutrition intensive programme is effective, in the short term, in reducing obesity and metabolic risk (fasting glucose). However, long term adherence to this program is unknown. |

| Yin et al., 2012, USA [49]. | Quasi-experimental pre- and post-test design with two groups; Community Head start centres and home base settings | 384 predominantly Hispanic Children; 52% female; attending community head start centres; and aged 3 to 5 (mean =4.1) years. |

18 Week intervention PA and Nutrition.

Centre based intervention:

i). PA: 60 minutes of structured (15 – 20 minutes) and free play (30 – 45 minutes) per day

ii) Nutrition promotion

Home based intervention: i). Peer led parent obesity education. ii). healthy snack for their children (<150 calories). |

Control group received intervention materials and implementation training upon completion of the study | Adjusted difference in BMI z-score for age and gender between Centre based intervention + home based and comparator –0.09 (P<0.09), Adjusted difference in BMI z-score for age and gender between comparison and centre-based intervention = -0.04 (not significant) | This large size study with intervention in both centre and home setting targeting both PA and Nutrition showed improvement in BMI z scores though not statistically significant. Participants were children not described as overweight or obese, therefore nonsignificant reduction in zBMI is to be expected. |

| Yin et al., 2005, USA [51]. | Quasi-experimental pre- and post-test design with two groups; in elementary school setting. |

601 predominantly black (61%) elementary school children; Mean age of 8.7 years, female 52% with |

24 weeks (8 months) after school programme: i) 40 minutes academic enrichment ii) Healthy snack iii) 80 minutes PA |

265 children served as control, who only received health screening (no after school activities). | BMI (kg/m2) change: -0.16 (-0.40,0.07) p=0.18. % Body fat (BF): 0.76 (1.42, 0.09) p=0.027. Fat mass (FM) (Kg): -0.29 (-0.70,0.13) p=0.17. Free fat mass (FFM) (kg) 0.18 (-0.04, 0.40) p=0.12. WC (cm): -0.4 (-1.1,0.4) p=0.32. SBP (mmHg): -1.8 (-4.2,0.6) P=0.15. DBP (mmHg): -1.1 (-3.6, 1.5) p=0.41. TC (mg/dl): -0.2 (-6.2, 5.7) P=0.94. HDL (mg/dl): 0.7 (-2.1, 3.5) p=0.64 |

After-school intervention programme had some effects on BMI, body fat and lipid profile in Black communities, but not statically significant. The interventions are difficult to adhere to in home and community setting because it lacked parental involvement. |

| Wylie-Rosett et al., 2018, USA [52]. | RCT; safety-net paediatric primary care setting in Bronx, New York. |

360 predominantly Hispanic (73%) children with BMI ≥85th United States CDC BMI percentile for age and sex; aged 7 to 12 (mean =9.3) years, 33% were female. |

A 12-month programme: 8-weekly: i). Standard care ii). Enhanced programme (skill building core: food preparation or other skill activity for parents/guardians and children, PA session for the children and discussion session for parents/ guardians regarding their role in weight management. + Post-core programme support) |

Standard care – Quarterly visits to see a paediatrician for the weight management. | BMI Z-score change: The mean BMI Z-score decreased in both programmes, 0.12kg within the Standard Care (p < 0.01) and 0.15kg within both Standard Care + Enhanced Program (P < 0.01. No significant difference between the two programmes. Older children had a greater decline in BMI Z-score than younger (beta −0.04 units per additional year of age; P = <0.01). Girls exhibited a greater decline in BMI Z-score than boys, (β = 0.09 P = 0.03). TC (mmol/L) change: -0.1 P=0.05. HDL (mmol/L) change: 0.01 p=0.67. LDL (mmol/L): -0.07 p=0.04. Triglyceride (mmol/L): -0.06 p=0.08. |

In high-risk (with overweight/obesity) children, the enhanced care was not more effective than standard care, though clinical care in both groups reduced weight and improved lipid profile. |

| Wong et al., 2016, USA [53]. | A non-randomized trial: setting of community centres located in low- income neighbourhoods within the city. | 877 Hispanic and African American children, age 9 to 12 years with 47% female. | A nine-month programme: i). 90 minutes of structured PA twice a week for six weeks in the fall, early spring, and at the end of the school year. ii). 30 minutes of nutrition or healthy habits lessons twice a week during each of the three 6-week sessions. |

Regular after-school childcare enrichment programs at community centres offered by the site staff such as homework time, arts, and crafts activities, and supervised free play. | There were no significant intervention effects BMI (P=0.94), BMI z score (P=0.88) and BMI percentile (P=0.23) | Structured 90 minutes PA plus nutrition education was not more effective than supervised free play in reducing weight but helped enhance regular exercise. |

| Wilson et al., 2022, USA [54]. | RCT; Online setting. |

241African American, child/care giver dyads. Children aged 11- and 16-years with BMI ≥85th United States CDC BMI percentile for age and sex. | 24 weeks (6 months) programme: i). 8 week tailored online education on parenting, nutrition, PA and decreasing screen time. This was followed by 3 online booster sessions, 1 every 2 months. |

Control online program | There were no significant intervention effects BMI. significant effect of the group intervention on parent light physical activity at 16 weeks (B = 33.017, SE = 13.115, p = .012) and a similar trend for adolescents. | The Online programme was not effective for BMI but had useful impact on physical activities. Actual data was not shown on BMI means difference between intervention and comparators for both children and parents. |

| Williford et al., 1996, USA [55]. | Quasi-experimental with pre- and post-test analyses; school setting. |

17 African American male children in 7th grade from a physical education class; aged 11 to 13 (mean=12.8) years. |

15-week programme: 5days/week for 45 mins session of PE class + conditioning programme (aerobic training 3 days and weight training 2 days). |

PE class as usual | Sum of 7 Skin fold thickness (mm): 99.01 ± 67.8 to 97.7 ± 67.4 p=0.09. TC (mmol/L): 4.03 ± 0.81 to 4.03 ± 0.77 p=0.98. HDL (mmol/L) change intervention group: 1 ± 0.18 to 1.28 ± 0.17 p<0.05. LDL (mmol/L) change intervention group: 2.73 ± 0.74 to 2.41 ± 0.81 p<0.05 |

Small improvement in HDL and LDL from the PA intervention. However, the sample was small, and it is not clear how effective this PA alone intervention is on overweight/obesity. |

| Williamson et al., 2006, USA [56]. | RCT; internet based interactive behaviour therapy. |

57 African American girls, Aged 11 to 15 (mean=13.2) years, with BMI >85th percentile for age and gender based on 1999 National Health and Nutrition Examination Study normative data and with a biological parent with BMI>30. |

A 96 weeks (24 month) internet programme: i) An interactive behavioural internet program ii) Face-to- face sessions and e-mail correspondence by a counsellor. |

An internet health education program (a passive (non-interactive) program that provided useful health education for the parents and the adolescents by electronic links to other health-related web sites.) | BMI, F (3,54) = 3.13, p < 0.04. BF % change: 0.08 ± 0.71 vs. 0.84 ± 0.72 BF, P<0.05. |

The internet- based intervention was effective in reducing weight in overweight/obese girls. However, the girls appeared to be a highly motivated groups as they were willing to purchase their own computers at, at least $300.00. |

| Van der Heijden et al. 2010, USA [57]. | Quasi-experimental with pre- and post-test analyses; recruitment done the community setting, checking done in hospital for good health. |

29 Hispanic adolescents, Median age 15 years, obese and lean (obese participants had BMI >95th and all lean participants <85th percentile for age according to CDC growth charts). Female were 48%. | A 12-week PA programme supervised by an experienced exercise physiologist: i) PA: a twice a week 30-min aerobic exercise session at ≥70% of peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) at a hospital physical therapy unit. . |

None | In obese participants, intramyocellular fat remained unchanged, whereas hepatic fat content decreased from 8.9 ± 3.2 to 5.6 ± 1.8%; P < 0.05 and visceral fat content from 54.7 ± 6.0 to 49.6 ± 5.5 cm2; P < 0.05. No significant changes were observed in lean participants. Insulin resistance: Decreased fasting insulin (21.8 ± 2.7 to 18.2 ± 2.4 μ/ml; P < 0.01) and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMAIR) (4.9 ± 0.7 to 4.1 ± 0.6; P < 0.01). No significant changes were observed in lean participants |

Aerobic exercise in a controlled environment reduced hepatic fats, visceral fats, and insulin resistance in obese participants. The sample was small and in selected individuals with severe adiposity, therefore may not be generalisable. |

| Tomayko et al., 2018, USA [58]. | A modified crossover design; 4 tribal reservations and one urban clinic setting. | 450 American Indian adult/child dyads, children were aged 2 to 5 (mean 3.3) years and 50% female. | A 52 weeks (12 months) programme: Monthly mailed healthy lifestyle lessons, items, and children's books addressing six targets: increased fruit and vegetable consumption, decreased sugar consumption, increased PA, decreased screen time, improved sleep habits, and decreased stress (adult only) |

Active control -crossover. | BMI-z score at 1 year: Intervention = 0.80 ± 1.10 Comparator = 0.76 ± 1.04 p=0.513 |

The unsupervised mailed education materials were not effective in reducing BMI z scores. The extent to which the material was used is unknown. |

| Taveras et al., 2017, USA [59]. | RCT; 6 paediatric practices in an urban setting. |

721 predominantly (65%) non-White children, aged 2 to 12 (mean = 8) years with BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age according to CDC growth charts. Female comprised 51% | A 12-month programme, enhanced primary care plus contextually tailored, individual health coaching lasting 15 – 20 minutes using telephone, videoconference (Vidyo), or in-person visits. |

enhanced primary care 2 monthly educational materials focusing healthy lifestyle behaviour change. |

BMI z score: In the enhanced primary care group, adjusted mean (SD) BMI z score improvement of −0.06 BMI z score units (95% CI, −0.10 to −0.02) from baseline to 1 year. In the enhanced primary care plus coaching group, improvement of −0.09 BMI z score units (95% CI, −0.13 to −0.05). However, there was no significant difference between the 2 intervention arms (difference, −0.02; 95% CI, −0.08 to 0.03; P = 0.39). | Advanced clinical care improved BMI z scores in high-risk children (overweight/obese), but additional individual coughing did not add effect. |

| Story et al., 2012, USA [60]. | RCT; schools in reservations. |

454 American Indian children attending Kindergarten and first grade, mean age 5.8 years, and 49% female. | A 45-week Programme: i). PA: school-based PA, at least 60 minutes daily. ii). Nutrition: Healthy eating at school. iii). Family-focused intervention: improving nutrition, PA and reducing sedentary lifestyle. iii). Parents received telephone motivational encouragement |

Usual school activities and no change to family environment | Mean BMI (kg/m2) net difference (I vs C): 0.34 p=0.057 BMI-z net difference: 0.01 p=0.904. %BF net difference 0.9 p=0.122. Prevalence overweight (BMI ≥85th percentile and <95th): net difference. 10.14 p=0.019. Prevalence obese (BMI ≥95th percentile): 2.11 p=0.503 |

Interestingly, this multicomponent programme reduced the prevalence of overweight although participants were young children and not described as overweight, |

| Stolley et al., 2003, USA [61]. | RCT; Public Schools settings. |

618 African American preschool children, age 3 to 5 (mean = 4.3) years, with 53% female. | A 14-week programme: i). Education: two lesson sessions each week on healthy eating and exercise ii). 20-min PA, two sessions each week. iii). Parents received a weekly newsletter |

Usual preschool activities | Adjusted BMI(Kg/m2) diff. -0.08 P=0.28. Adjusted BMI z scores = -0.05 p=0.23. |

Predominantly nutrition and PA education intervention reduced BMI z scores, but not more effective than usual school activities. |

| Soltero et al., 2018, USA [62]. | RCT; recruitment through schools, community centres, and healthcare organizations but intervention administered at YMCA centres settings. |

160 Hispanic children aged 14 to 16 years with BMI BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts or a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Female were 46% | A 52-week (12 months) programme: i). Nutrition and health education one days/week, 60 minutes. ii). PA: exercise curriculum was delivered by fitness instructors three days/week for 60 minutes iii). Behaviour changes strategies. |

Handout with general information on healthy lifestyle behaviours |

Changes in insulin sensitivity (using insulin and glucose sensitivity during OGTT): Intervention: 0.8±0.1 to 2.2±0.1, p<0.01. Comparator: 1.7±0.2 to 1.7±0.1, p>0.05. Between group difference (delta difference) = Δ=0.37, p<0.05 at 12 weeks. Δ=0.21, p>0.05 at 12 months (no difference). Within group changes in intervention group at 12 months: BMI (kg/m2) = 1.16 P<0.001. BMI% = -0.1 P=0.95. %BF = -0.63 p=0.65. WC (cm) = 1.68, p=0.29. At 12-months, between group differences in BMI% and percent body fat remained significant (all p<0.01); however, changes in WC was not (p=0.078). |

There seems to be short term effective in increasing insulin sensitivity but no difference long term in this high-risk group with obesity. The intervention was shown effectiveness in reducing adiposity parameters and sustain at 12 months. This long duration Nutrition education and PA intervention improved insulin resistance but only in the short term. |

| Slusser et al., 2012, USA [63]. | RCT; Family clinic & Wellness Centre, and community sites serving low-income predominantly Hispanic community. |

161 Hispanic children, aged two to four years living in the home. | A 17-week program comprised of: 9 sessions lasting 90minutes of parent training based on social learning theory | Care as usual and a standard nutritional informational pamphlet | BMI percentile changes: Intervention -3.85 Comparator = 1.33 BMI Z scores diff. between Intervention group and control -2.4 P=0.04. (Children in the intervention group decreased their BMI z-scores significantly on average by 0.20 (se= 0.08) compared to children in the control group who increased z scores on average by 0.04 (se=0.09) at one year (P<0.05). |

Only 9 sessions over 17 weeks of parent training were effective in reducing overweight/obesity in pre-school children, from low come families. Not clear whether would be the same in larger population or over longer period |

| Shaibi et al., 2006, USA [64]. | RCT; participants were recruited through medical clinics, advertisements, and local schools. Intervention was conducted at Girls and Boys clubs. |

22 Hispanic male adolescents, mean age 15.3 years, with overweight, BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age according to CDC growth charts | A 17-week programme: i). PA: twice-per-week resistance training | non-exercising control group | Changes insulin sensitivity (x10-4 min-1mL1, using insulin and glucose sensitivity during OGTT): I = 0.9±0.1 p<0.05 C = 0.1±0.3 The intervention group significantly increased insulin sensitivity compared with the Comparator group (P < 0.05) |

Resistance training alone significantly reduced metabolic risk factor of insulin sensitivity within 3 months in overweight/obese children. However, its effect on adiposity was not reported. |

| Robinson et al., 2021, USA [65]. | RCT; recruitment was done through medical clinics, advertisements, and schools. Administration of intervention was done at Los Angeles Boys and Girls Club. |

241 primarily Hispanic children, aged seven to 11 years with overweight or obesity, BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts. Female were 56%. | A 3-year community-based, multi-level, multi-setting, multi-component (MMM) Programme: i). Home environment changes and behavioural counselling, ii). community after school team sports, iii). Reports to primary health-care providers |

General Health Education (HE) | Mean adjusted difference in BMI trajectory over 3 years between MMM and HE = −0.25 (CI −0.90, 0.40) kg/m2, Cohen’s d = −0.10, p= 0.45). |

The multi-component and multi-level intervention did not reduce BMI gain in low-socioeconomic Hispanic children with overweight, despite the long duration of intervention. However, there was drop in participation over time. |

| Rieder et al., 2013, USA [66]. | Quasi-experimental with pre- and post-test analyses; community setting. |

349 majority minority ethnic group (52% blacks and 44% Hispanic), mean age 15 years. Female were 54% | A 9-month programme: i) Teaching of healthy lifestyle principles. ii). PA: 60 minutes/week moderate PA. iii). Monthly family healthy behaviour education |

No comparator intervention | Decreases in BMI (kg/m2) (- 0.07 per month; p < 0.001). Percent overweight (- 0.002%/month; p < 0.001) BMI z-score (- 0.003/month; p < 0.01). Decrease in BMI percentile (- 0.006 percentile/month; p = 0.06). |

This 9-month education and PA showed a small effect in reducing overweight/obesity in adolescent. However, their pre-intervention weight status is unknown. |

| Resnicow et al., 2005, USA [67]. | RCT; churches in a rural setting. |

147 African Americans female children aged 12 to 16 years with BMI > 90th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts | A 26 weeks (6 months) multicomponent programme tailored to the population. High intensity (24 to 26 sessions). i). At least 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous PA, ii). Preparation and/or consumption of low-fat, portion-controlled meals or snacks. iii). Parental involvement. |

Moderate-Intensity Intervention. Six session of education, topics included: fat facts, barriers to physical activity, fad diets, neophobia (i.e., fear of new foods), and benefits of PA |

0.5 BMI units’ difference. This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.20). | There was no difference between high intensity and moderate intensity PA over 6 months in a group obese African American adolescent girl. However, both showed some improvement in adiposity. |

| Prado et al., 2020, USA [68]. | RCT; community setting. |

22 Hispanic children mean age 13.1 years (in 7th/8th grade) who were overweight or obese, BMI > 85th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts. Female were 88% | A 12-week programme with 2.5-hour: 1.5-hour lifestyle education involving families and children, and 1 hour of PA for the children). PA was coach supervised in local park. |

Prevention as usual, participants were referred to their local health department’s health initiative Internet page and the usual programs they offer to reflect the typical services that overweight and obese adolescents may receive in their own community. |

BMI (kg/m2) difference baseline and 2 years: -0.3 (CI -0.7 to 0.1) p=0.15 (not significant). | Small sample and short duration lifestyle education intervention. No effect demonstrated. Not generalisable because of selected small sample. |

| Polonsky et al., 2019, USA [69]. | RCT; Communities and schools. |

1362 predominantly black, fourth- through sixth-grade students, Mean age 10.8 years, with 51% female. | A 2-year programme: Free school breakfast; 18 session 45 minutes nutrition education; items with the one healthy breakfast logo; |

Control schools served breakfast free of charge in the cafeteria before school, and existing SNAP-Ed nutrition education continued in control schools. | There was no significant difference in the combined incidence of overweight and obesity between intervention schools (11.7%) and control schools (9.1%) after 2.5 years (odds ratio [OR], 1.42; 95% CI, 0.82-2.44; P = 0.21. | Healthy school breakfast and education alone without PA or home environment change was not shown to be effective in preventing overweight and obesity. Moreover, the incidence of overweight and obesity was slightly higher in the intervention group |

| Pena et al., 2022, USA [70]. | RCT; Community YCMA centres setting. |

117 Hispanic youths aged 12 to 16, with prediabetes (fasting glucose 100 to 125 mg/dL or HbA1c) level of 5.7% to 6.4%) and obesity BMI >95th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts. Female were 40% | A 52-week (12 months) programme: i). One day/week of nutrition and health education with behaviour change skills training ii). PA: Three days/week of physical activity. |

Comparator group met with a paediatric endocrinologist and a bilingual, bicultural registered dietitian to discuss laboratory results and develop SMART goals for making healthy lifestyle changes. | The intervention led to significant decreases in mean 2-hour glucose level (baseline: 144 mg/dL; 6 months: 132 mg/dL; P = .002) and increases in mean insulin sensitivity (baseline: 1.9 [0.2]; 6 months: 2.6 [0.3]; P = .001). |

The one-year education and structured PA intervention was effective in decreasing NCD metabolic risk in a high-risk group. However, there was no information on effect on overweight/obesity. |

| Novotny et al., 2015, USA [71]. | RCT; clinic setting. |

85 predominantly Asian children, aged 5 to 8 years; with BMI between the 50th and 99th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts. Female were 62%. | A 39-week (9 months) programme: i). Handout on recommended eating pattern, DASH of Aloha cookbook, ii). Farmers Market locations, iii). A PA location/ map in the study informational packet |

Received a welcome letter and attention control mailings on unrelated health topics, such as importance of hand washing, sun protection, and dental hygiene, at 2, 5, and 8 months. |

There was no significant effect of the DASH intervention on change in BMI Z score, SBP, waist circumference, total body fat by skinfolds, PA level, or total HEI score (p > 0.05. DBP percentile was 12.2 points lower in the treatment group than the control group (p = 0.01). |

The only effect was on DBP. However, as participants were a clinic setting there could have ongoing clinical care. |

| Norman et al., 2016, USA [72]. | RCT; clinic setting. |

106 predominantly Hispanic (82%) children aged 11–13 years who are obese, BMI > 95th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts. Female were 51% | A 17 week (Four-month) ‘steps’ beginning with the most intensive contact followed by reduced contact if treatment goals were met. Based on Chronic Care Model (CCM) and social cognitive theory). i). Counselling, Physician led on healthy dietary and PA. ii). Health educator visits discussed weight management, barriers to healthy eating and PAs iii). Follow up phone calls, |

Participants received an initial counselling visit by the physician, one visit with a health educator, materials on how to improve weight-related behaviours, and monthly follow-up mailings on weight-related issues. | BMI (kg/m2) change difference between intervention group and comparator: Boys 1.3 p=0.003. Girls 0.7 (p=0.15). BMIz score change difference between intervention group and comparator between intervention group and comparator: Boys 0.1 p=0.008. Girls -0.2 (p=0.42). BF (kg) No difference Boys P=0.26. Girls (P=0.11). Fasting lipid and BP no difference. |

The intervention was shown to be effective in reducing BMI among boys but not girls. The intervention was, however, tested in age group 11 to 13, a period of growth sprout in girls. |

| Messito et al., 2020, USA [73]. | RCT; clinic setting. |

643 Hispanic pregnant mothers with a singleton uncomplicated pregnancy and postpartum infants. Fifty-four (54%) of infants were female. | 33-month programmes based on Social cognitive theory to promote healthy behaviours: i). Prenatal nutrition counselling, ii). Postpartum lactation support, iii). Nutrition and parenting support groups coordinated with paediatric visits. |

Standard prenatal, postpartum, and paediatric primary care. | Intervention infants had significantly lower mean WFAz at 18 months (0.49 vs 0.73, P = .04) and 2 years (0.56 vs 0.81, P = .03) but not at 3 years (0.63 vs 0.59, (P = 0.76). Obesity prevalence was not significantly different between groups at any age point 33.5% vs 39.4% (P=0.11) |

The intervention targeting mothers was only effective up to 18 months, but not sustained at 3 years |

| Johnston et al., 2007, USA [74]. | RCT in a setting of a school that serves an urban student population. |

60 Mexican American children between the ages of 10 and 14 years with BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts. Female were 45% | A six-month programme: i). PA: A 12-week instructor/ trainer-led intervention, 4 days per week, lasting 35 to 40 minutes at school location. ii). Nutrition instruction (1 day/week) iii). Parents monthly meetings to teach them how to adapt family meals and activities to facilitate healthy changes. |

Six-month parent-guided manual intended to promote child weight loss and long-term maintenance of changes. | zBMI in the intervention group significantly reduced compared the comparator group (F = 11.72; (P < 0.001), with significant differences in zBMI change at both 3 and 6 months (F = 16.50, (P < .001) and F = 22.01, (P < .001), respectively Children in the intervention group significantly reduced their total cholesterol (F = 5.27; P = 0.027) and LDL cholesterol (F = 7.43; P = 0 .01) compared with children in the comparison condition at 6 months. |

In an urban setting, structured PA and nutrition was more effective than parental education alone over a short duration, 12 weeks. It is however uncertain whether this improvement can be sustained long term. |

| Johnston et al., 2013, USA [75]. | RCT in a setting of a school that serves an urban student population. |

71 Mexican American adolescents aged 10 to 14 years. Female were 55% | 12-week programme: 12 weeks of daily instructor/trainer led, healthy eating and PA behaviour change intervention sessions followed by 12 weeks of biweekly follow-up session. Based on Behaviour theory |

Given a parent-guided manual for the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity. The manual provides a 12-week weight management plan and instructions for long-term maintenance of changes. |

Repeated-measures analyses revealed that adolescents in intervention significantly reduced their BMI z scores compared with adolescents in control (F = 8.34; p < .001). Similar results for BMI (overall: F = 6.0, p < .01; 1 year: F = 6.6, p < .05; 2 years: F = 7.0, p < .05) and BMI percentile (overall: F = 5.8, (p < .01); 1 year: F = 5.6, (p < .05); and 2 years: F = 6.6, (p < .05). TC: F = 5.27; P=0 .027). LDL: F = 7.43; P =0.01. HDL: (F 1= .5, P>0.05). TG: (F = 0.5, p>0.05). |

Structured PA, nutrition education and long-term follow up was more effective than parental education in reducing both overweight/obesity and metabolic NCD risks. This effect was sustained for over 2 years. |

| Hull et al., 2018, USA [76]. | RCT; home setting, Metropolitan area. |

318 Hispanic children aged 5 to 7 years with at least one adult parent of Hispanic origin (self-identified) child with BMI ≥25th <-35/kg/m2 percentile. Female were 52% |

52 weeks (12 months) programme aimed to increase PA, decrease sedentary behaviour, and improve healthy eating behaviours. Used parental modelling and experiential learning for children. Was based on Social cognitive theory, behavioural choice theory, and food preference theory. |

Focused on oral health | Intervention short-term effect: BMI z 0.068 (P=0.11). BMI 0.084 (p=0.42). WC-to-Height ratio -0.004 (p=0.15). WC-to-Hip ratio 0.005 (p=0.24). Intervention long-term effect: BMI z 0.023 (P=0.25). BMI (Kg/m2) 0.067 (p=0.27). WC-to-Height ratio 0.006 p=0.02. WC-to-Hip ratio: -0.004 (p=0.15). |

The purely education and behaviour change intervention showed no effect. |

| Hughes et al., 2021, USA [77]. | RCT in a community childcare centres settings. |

25 predominantly Hispanic children aged were 3 to 5 years. Female were 50% | A 7-week programme: Weekly teaching curriculum on Nutrition and PA. |

The control arm received no curriculum | BMI z-score showed no significant (F = 0.18, P = 0.91). | Short duration nutrition education and infrequent PA showed no effects. |

| Hollar et al., 2010, USA [78]. | Quasi-experimental with pre- and post-test analyses in setting of elementary schools. | 1197 predominantly Hispanic children, mean age 7.8 years. | A 2-year programme: i). Dietary intervention: Modifications to school-provided breakfasts, lunches, and extended-day snacks in the intervention schools. ii). PA. opportunities for PA during the school day. |

Usual practice | Significantly more children in the intervention schools than in the control school stayed within the normal BMI percentile range for both years of the study (P=0.02). | Long duration actual dietary change and PA reduced BMI. |

| Heerman at al., 2019, USA [79]. | RCT; physicians’ offices and community settings. |

117 majority Hispanic child-parent pair, children, aged 3 to 5 years, Spanish speaking, and a BMI >50th percentile age and sex according to CDC growth charts. Female were 54% | A 15-week programme: i). Weekly, 90-minute education and PA sessions, followed by twice-monthly of health coaching calls for 3 months. |

The control group was a twice-monthly school readiness curriculum for 3 months. | After adjusting for covariates, the intervention’s effect on linear child BMI growth was -0.41 (Kg/m2) per year (95% confidence interval -0.82 to 0.01; (p = 0.05). | Surprisingly health coaching alone showed effects in young children, however the study was under powered and not generalisable. |

| Hasson et al., 2012, USA [80]. | RCT; clinic setting. |

100 African American and Latino children aged 14 to 18 years with obesity BMI >95th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts. Female were 61% |

16 week programme: Intervention 1(N): Nutrition (N) education only, once per week targeting and four motivational interviewing (MI) sessions during the 16 weeks Intervention 2 (N+ST): Nutrition (N) + strength training (ST): In addition to the nutrition education, participants in the N+ST group also received strength training twice per week (~60 min/session) for 16 weeks at a Lifestyle Intervention Laboratory. |

No intervention but pre and postintervention data collection |

There were no significant differences in BMI, BMI z-score, BMI percentile between N+ST, N and control groups. However N compared to N+ST and control reported significant improvements in insulin sensitivity (+16.5% vs. −32.3% vs. −6.9% respectively, (P < 0.01) and disposition index (DI: +15.5% vs. −14.2% vs. −13.7% respectively, (P < 0.01). Hepatic fat fraction (HFF): The N+ST group had a 27.3% decrease in HFF compared to 4.3% decrease in the N group |

Both Nutrition and Nutrition plus strength training were not effective in reducing BMI but improved insulin sensitivity. |

| Haines et al., 2016, USA [81]. | RCT; Community health centres and community agencies. |

112 predominantly Hispanics parents/child dyads with children aged 2-5 years with 50% female | A 39-week programme: A total of 9 sessions of parenting skills, children’s education, and homework assignments (based on social contextual framework theory) |

Mailed publicly available educational materials on promoting healthful behaviours among pre-schoolers [e.g., My pyramid for pre-schoolers each week for 9 weeks. | BMI (kg/m2) decreased by a mean of 0.13 among children in the intervention arm and increased by 0.21 among children in the control arm, with an unadjusted difference of 20.34 (95% CI 21.21, 0.53). After adjusting for child sex and age, the difference was minimally changed (20.36; 95% CI 21.23, 0.51; (P=0.41). | The predominantly parents and young children nutrition education programme was not effective on adiposity. |

| Gatto et al., 2017, USA [82]. | RCT; elementary schools. |

319 Hispanic children in 3rd, 4th and 5th grade in schools that offer after school programme. | 12-week programme (LA Sprout). Weekly: i). 45-minute interactive cooking/nutrition lesson and a ii). 45-minute gardening lesson. iii). Parallel classes were offered to parents’ bimonthly. The intervention was based on Self efficiency theory |

Did not receive any nutrition, cooking, or gardening information from investigators | Intervention group had significantly greater reductions in BMI z-score than controls [−0.1(9.9%) versus −0.04 (3.8%), respectively; (p=0.01). Intervention group had a 1.2 cm (1.7%) reduction in WC, while controls had a 0.1 cm (0.1%) increase after the intervention (p<0.001) Fewer Metabolic syndrome (n=1) after the intervention than before (n=7), while the number of controls with the metabolic syndrome remained essentially the same between pre- (n=3) and post- intervention (n=4). |

A predominantly school-based nutrition programme reduced both BMI and metabolic risks in the short term, however it not clear if this can be sustained. |

| Fiechtner et al., 2021, USA [83]. | RCT; clinic and community settings. |

4044 Hispanic, low-income children aged 6 to 12 years with BMI > 85th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth charts. Female were 48% | Two intervention groups: Intervention I: Healthy Weight Clinic (HWC). 30 hours multidisciplinary team nutrition and PA education to parents/guardians and child, alternating group, and individual sessions Intervention II: YMCA Modified Healthy Weight and Your Child (YMCA M-HWYC). A total of 25 education sessions were offered to the parent/guardians and child over 1year. each session was 2 hours long. Both groups were exposed to primary care provider weight management training and text messages to parents/guardians for self- guided behaviour-change support. |

Eight demographically matched, comparison community health centres were chosen as control sites. | The mean difference in % of children in the 95th percentile BMI between the M-HWYC and the HWC was 0.75 (90% CI: 0.07 to 1.43), which did not support noninferiority. Compared with the control sites, children in the HWC had a -0.23 (95% CI: -0.36 to -0.10) decrease in BMI (Kg/m2) per year and a -1.03 (95% CI -1.61 to -0.45) decrease in % of children in 95th percentile BMI. There was no significant effect on BMI in the M-HWYC. | There was no difference in offering an education (nutrition and PA) programme in a multidisciplinary clinical setting and community YMCA setting in a large sample of low-income high-risk children. Both approaches reduced the percentage of children in the 95th percentile BMI. |

| Eichner et al., 2016, USA [84]. | Quasi-experimental with pre- and post-test analyses; school setting. |

353 predominantly America Indian children in sixth, seventh, and eighth grade aged 12 to 15 years. Female were 50% | A 5-year programme, Middle School Opportunity for Vigorous Exercise (MOVE): i). PA: walked or ran 1 mile each school day and then engaged in a team activity such as basketball, soccer, foot- ball, dodge ball, or volleyball. |

None participants in the MOVE programme. |

Mean BMI z scores remained the same among girls participating in MOVE (from 0.7 to 0.7) and increased for nonparticipating girls (from 1.1 to 1.2). Mean BMI z score decreased among boys participating in MOVE (from 0.8 to 0.7) and increased among nonparticipating boys (from 1.1 to 1.2). Overall, MOVE participants had significantly smaller BMI z score than non-participants (P=0.01) |

The 5-year PA was shown to prevent increase BMI, but as most of the children were not in the high-risk category, it did not reduce BMI z scores. |

| Dos Santos et al., 2020, USA [85]. | Quasi-experimental with pre- and post-test analyses; school setting. |

46 predominantly Hispanic parent-child dyads, children aged from 10 to 16 years old, with a BMI ≥85th percentile CDC chart for age and sex. 45% female. | An eight-week programme comprised of: i) Joint education of parent and child on nutrition, PA and lifestyle issues. ii). PA classes: Adoles cents engaged in moderate to vigorous PA (e.g. lap runs). |

None | Mean BMI (kg/m2): Pre-intervention = 29.95 (SD = 5.82); post-intervention = 29.44, (SD = 5.78; p = 0.012) Participants' waist- hip-ratio from pre-intervention (mean = 1.00, SD = 0.06) to post intervention (mean = 0.99, SD = 0.06; p <0.001). |

Education and moderate PA had a small effect in reducing adiposity, however the sample size was small and had short duration of intervention. Long term sustainability is uncertain. |

| De Heer et al., 2011, USA [48]. |

RCT; school setting. |

901 Hispanic students in third, fourth, and fifth grades, mean age 9.2 with 45% female. | 12 weeks After-school programme ran twice weekly, based on Social cognitive theory. i). Education: 20-to-30-minute health education component ii). PA: followed by 45 to 60 minutes of PA. |

Control and spill over groups received fourth-grade health workbooks and incentives at pre-test and follow-up measurements, but they did not attend the after-school sessions | BMI percentile reduction: Intervention group = 2.8% (P = 0.015); Spill over group = 2.0% (P = 0.085) and Control group = 1.4% (P = 0.249). |

This education and PA programme were shown to reduce BMI; however, a comparative analysis was not done, therefore it is unclear to what extend it is effective. |

| Davis et al., 2016, USA [86]. | RCT; community and school settings. |

1898 predominantly American Indian and Hispanic children, aged 3-years, enrolled in Head Start (HS) centres, with 47% female. | 5 years programme based on socioecological approach. , A 6 components programme comprised of nutrition and PA education ; and increasing availability of healthier food options. | Participated in measurement but not intervention | No effect of the intervention on change in BMIz was observed difference in slopes = −0.006 [95% CI −0.031 to 0.020]) (p = 0.69). | This large size and long duration predominantly prevention education intervention did not show effect on BMI although there some reduction in BMIz. |

| Davis et al., 2012, USA [87]. | RCT; schools, community centres and health clinics. |

53 African American and Latino children in grades 9th through 12th, mean age 15.3 years, with BMI ≥85th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth chart. Female were 55%. | 12-month Maintenance programme (newsletter group) following a 4-month nutrition and strength training intervention: Received a monthly newsletter in the mail that matched their 4-month intervention group assignment |

Maintenance group class: met monthly (classes lasted 90 min) and received a monthly class that was like their 4-month intervention classes |

Fasting insulin and acute insulin response decreased by 26% and 16%, respectively (P < 0.001 & P = 0.046); while HDL and insulin sensitivity improved by 5% and 14% (P = 0.042 & P = 0.039) respectively. | 12-month programme of newsletter followed by nutrition and resistance training improved insulin and lipid metabolic profiles, though on overweight/obesity was not assessed. |

| Davis et al., 2021, USA [88]. | RCT; schools. |

3135 predominantly Hispanic, 3rd-5th grade students with mean age of 9.2 years. Female were 53%. | 9-month programme (Sprout): i). Garden Leadership Committee formation; ii) a 0.25-acre outdoor teaching garden; iii). 18 student gardening, nutrition, and cooking lessons iv). nine monthly parent lessons. Based on social ecological-transactional model |

The control schools received a delayed intervention (identical intervention as described) in the year after the post-testing for that wave. | BMI change, mean (kg/m2): I=4.12; C=3.71, p=0.006. BMI z-score change, mean: I=-0.04; C=-0.02, p=0.51. BMI percentile change: I=-0.82; C=-0.39, p=0.53. WC change, mean (cm): I=1.16; C=-1.53, p=0.34. % BF change: I=-0.34; C=-0.49, p=0.40. SBP change, mean (mmHg): I=-0.39; C=0.20, p=0.64. DBP change, mean (mmHg): I=-1.33; C=0.32, p=0.18. |

The nutrition intervention did not show effectiveness in most overweight/obesity parameters or blood pressure except difference in mean BMI change. |

| Davis et al., 2009, USA [47]. | RCT; clinic setting. |

54 overweight Hispanic children, aged 14 to 18 years (mean 15.5), BMI ≥85th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth chart. | 16-week Nutrition + Strength training (N+ST) programme: In addition to the nutrition education class described under comparator, participants in the N+ST group also received strength training twice per week (~60 min/ session) for 16 weeks |

Nutrition only group: once per week (~90 min) for 16 weeks for a culturally tailored dietary intervention. |

There were no significant intervention effects on insulin sensitivity, body composition, or most glucose/insulin indices with the exception of glucose incremental area under the curve (IAUC) (P = 0.05), which decreased in the N and N+ST group by 18 and 6.3% compared to a 32% increase in the C group. |

The short duration and small size nutrition education and PA programme had no effect on Adiposity and metabolic risk. |

| Davis et al., 2011, USA [89]. | RCT; school setting. |

38 Hispanic females, in grades 9–12 aged 14 to 18 years, BMI ≥85th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth chart. |

16-week intervention with: 1ntervention group I, circuit training (CT): aerobic + strength training, two times/week for 60–90 min per session. Intervention group II, CT + motivational interviews (MI) on behaviour change |

Control offered abbreviated CT intervention after post-test data collection | No changes in BMI, children in all conditions increased their overall mean BMI z- score over the course of the study. WC: CT participants also decreased waist circumference (-3% vs +3%; P = 0.001). % BF: Subcutaneous adipose tissue (10% vs 8%, P = 0.04), visceral adipose tissue (j10% vs +6%, P = 0.05). Fasting insulin (24% vs +6%, P = 0.03), and insulin resistance (-21% vs -4%, P = 0.05). |

16 weeks PA (aerobic and strength) programme was effective in reducing fat depots and improving insulin resistance in Latino youth who are overweight/obese. The additional motivational interviewing showed no additive benefit. Both interventions had no effect on overweight/obesity. |

| Crespo et al., 2012, USA [90]. | RCT; schools and community settings. |

808 Hispanic parent–child dyads, children mean age 5.9 years with 50% female | Three groups, 4 year intervention programme: Intervention I, Family group: Home visits (newsletters, recipe cards delivery and goal setting) and follow up phone calls. Intervention 2, community group: Improvement of nutrition and PA environment in school playground and community parks. Distribution of education materials. Intervention 3, Family + Community group: Involved in both family and community intervention |

Control: Participants in the control condition were asked to maintain their regular lifestyles and to complete the yearly measurements. |

No changes in any weight measures were statistically significant. Children in all conditions increased their overall mean BMI z- score over the course of the study. | Despite long duration, the nutrition education and support programme at family, school and combined family and school settings was not effective in reducing BMI. However, the effect of the intervention on other metabolic was not assessed. |

| Chen et al., 2011, USA [91]. | RCT; web-based setting. |

54 Chinese American Adolescents aged 12 to 15 (mean = 12.5) years old and were normal weight or overweight, BMI ≥85th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth chart. 70% female | An 8-week web-based programme (based on Transtheoretical Model– Stages of Change): i). nutrition, PA, and coping ii). Internet sessions to coach parents on parenting the skills. |

Participants in the control group also logged on to the Web site using a preassigned username and password. Every week for 8 weeks, adolescents also received general health information. | No reduction in BMI (Kg/m2) in both intervention (t0 =20.79, T3=20.76) and control (t0=20.25, t3=20.21) Significantly more adolescents in the intervention group than in the control group had decreased their waist-to-hip ratio (Effect size 0.01, p =0.02). DBP (Effect size 1.12, p =0.02). |

This short duration, 8 weeks, web-based education programme was not shown to be effective reducing BMI. However, as most of the participants were of normal weight, the intervention could have played a preventive role. |

| Chen et al., 2019, USA [92]. | RCT; community setting. |

40 Chinese American children aged 13 to 18 years of age; (3) had a BMI ≥85th percentile for age and sex according to the CDC growth Chart. | 12-week intervention (based on social cognitive theory): i) used a wearable sensor (Fit- bit Flex) for six months, ii). reviewed eight online educational modules. for three months, and, after completing the modules received tailored, biweekly text messages for three months. |

After completion of the baseline assessments, control group participants were given an Omron HJ-105 pedometer and a blank food-and-activity diary; the adolescents were asked to record and track physical activity, sedentary activity, and food intake in the diary for three months. | BMI (kg/m2) difference −4.89, (p <.001), BMI z score difference = −4.72, (p <.001). | With overweigh/obese Chinese American children, the online education programme was effective in reducing BMI. |

| Chen et al., 2010, USA [93]. |

RCT; community setting. |

67 Chinese American children, aged 8 to 10 years who were normal weight or overweight (BMI ≥85th percentile for age and sex according to CDC growth chart). Female were 44% |

An 8-week ABC programme (Based on social cognitive theory): i). Children participated in a 45-min session of education and play based activities once each week for 8 weeks. ii) parents participated in two sessions that lasted 2 h each session during the 8 weeks. The parents took part in ‘Healthy Eating and Healthy Family: A Hands-on Workshop. Follow up was 8 months. |

Waiting-list control group, received intervention after the follow up period. |

Significant decrease of BMI (kg/m2) in the intervention group (19.74 to 19.32) (p<0.05) but not the control group (18.65 to 18.42), (p>0.05) No change in Waist to Hip ratio in the intervention group, 0.88 to 0.88, (P>0.05) Significant reduction of DBP in the intervention group, 61.03 to 59.27, (P<0.05) |

Surprisingly, small reduction in BMI and CVD risk among Chinese American was shown after a few sessions of child and parent education and play activities. However, the result may not be generalisable because of convenient sampling. |

| Caballero et al., 2003, USA [94]. | RCT; school setting, serving American Indian. |

1704 American India from 3rd to 5th grade, mean age was 7.6 years. | The 3-year intervention had 4 components education: i) change in dietary intake, ii) increase in PA iii) a classroom curriculum focused on healthy eating and lifestyle iv) a family-involvement program. |

The control group participated in measurement but not interventions | Mean diff at follow up: %BMI Mean difference at follow up: -0.2, p=0.30. %BF mean difference = 0.2, (p=0.66) Triceps skinfold thickness (mm) Mean difference at follow up: 0.1, p=0.84 Scapula skinfold thickness (mm) Mean difference at follow up -0.1, (p=0.85). |

Despite the long duration of implementation, the predominantly education and low intensity PA programme did have effects on BMI/adiposity among American Indian children. However, there was indications that their Calorie intake improved. |

| Barkin et al., 2011, USA [95]. | RCT; participants were identified from primary care clinic, radio advertising, and local churches. |

72 mostly Hispanic parent-child dyads, children aged 8 to 11 years with a BMI ≥ 85% for age and sex according to CDC growth chart. Female were 54% | 6-month programme (Based on Transtheoretical Model): i) Counselling by a physician trained in brief principles of motivational interviewing. ii) 45-minute group health education session. iii) Five, monthly one-hour sessions on the topic of increasing PA for both parents and their child. |

Families in this control group received standard of care counselling from physicians trained using AAP guidelines, addressing both nutrition and activity. | Participants that had a higher baseline BMI were more likely to decrease their absolute BMI (Kg/m2) (β= −0.22; p< 0.0001). | The counselling and education effective for children with highest obesity, but less so in normal or overweight children. |

| Barkin et al., 2012, USA [96]. | RCT; community setting. |

75 majority Hispanic parent child dyad, child aged 2 to 6 years with 48% female. | A programme: i) weekly 90-minute skills- building sessions for parents and preschool-aged children designed to improve nutritional family habits, increase weekly PA, and sedentary activity. |

A brief school readiness program was conducted as an alternative to the active intervention because there is no standard care condition for comparison. | The effect of the treatment condition on post intervention absolute BMI (Kg/m2) was B = –0.59 (P=0.001) | These skills building intervention programme targeting both parents and children with obesity had small but significant effect onBMI. |

| Arlinghaus et al., 2017, USA [97]. | RCT; school setting. |

189 Hispanic adolescent students in grades 6 through 12 who were overweight or obese, BMI ≥ 85% for age and sex according to CDC growth chart. Female were 47%. | 6-month programme: Trained peer led discussion of the selected topic with their group of middle school students during PE classes. E.g., what they were going to eat for lunch that day or discuss their favourite vegetables. |

Usual PE classes | Significant differences were found between conditions across time (F = 4.58, P = .01). After the 6-month intervention, had a larger decrease in zBMI (F = 6.94, P = .01) than students in the control. | Adding nutritional peer led education to PE classes reduced adiposity in high-risk Hispanic children. |

| Arlinghaus et al., 2021, USA [98]. | RCT; school setting. |

491 Hispanic America middle school student enrolled in PE class. Female were 53% | A 12-month programme. i). PA component of an obesity intervention with established efficacy at reducing standardized BMI among this population. |

Control was physical education (PE) class as traditionally taught in the district (TAU) | Intervention decreased zBMI significantly more than control (F (1, 56) = 6.16, p < .05) | PA addition to PE class reduced overweight/obesity after 12 months, however it is uncertain if this is sustainable. |

| Adab et al., 2018, UK [45]. | RCT; Primary schools setting. |

1392 Non-White multi-ethnic population age 5 to 6 years in year 1 in primary schools. Female were 51%. | A 12-month programme: i). Encouraged healthy eating and PA, ii) Daily additional 30 minute school time PA opportunity, iii). A six week interactive skill-based programme in conjunction with a football club. iv). Signposting of families to local PA places. v) School led family workshops on healthy cooking skills. |

Ongoing year 2 health related activities. In addition, citizenship education resources, excluding topics related to healthy eating and physical activity were provided. |

At 15 months: mean difference in BMI Z score was −0.075 (95% confidence interval −0.183 to 0.033, P=0.18. At 30 months: mean difference was −0.027 (−0.137 to 0.083, P=0.63). no statistically significant difference between groups |

No significant effect of intervention on adiposity in both short and longer term. Although there was improvement in BMI, the difference was smaller the longer the duration of intervention. |

2.3. Risk of Bias within Studies

2.4. Effectiveness of Interventions

2.4.1. Quasi-experimental Pre and Post Intervention Studies

| Study, year and author | Intervention type, duration, intensity, and time characteristics | Intervention Settings | Age and characteristics of participating children | Intervention benefits on obesity and comorbidity outcomes measured | Recommendation for effectiveness on comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective interventions | |||||

| Yli-Piipari et al., 2018, USA [50]. | 12 weeks of supervised PA (moderate/vigorous,60 mins, twice a week) and parents/guardian nutrition education | Health care, paediatric primary care setting | Overweight/ obese Hispanic children, Mean age 11 years | Change mean BMI (kg/m2) change: -2.2, (P=0.04) | Short term supervised high intensity PA, targeting high risk adolescents is effective in reducing diabetes risk |

| Change mean BMI%: -2.53, (p=0.02) | |||||

| Change mean BMI z score: -3.64, (p=0-002) | |||||

| Change mean WC (cm): -2.57, (p=0.02) | |||||

| Change mean fasting glucose: -6.43, (p<0.001) | |||||

| Williford et al., 1996, USA [55]. | 15 weeks supervised, PA only 5days/week for 45 mins session of PE class + conditioning programme | School-based | Predominantly African American children, age range 12 to 13 (7th grade) | Change Sum of 7 Skin fold thickness (mm): -1.31, (P=0.09) | Short term more frequent, moderate intensity PA effective in serum lipid profile regardless of BMI |

| Change mean HDL (mmol/L): 0.28, (P<0.05) | |||||

| Change mean LDL (mmol/L): -0.32, (p<0.05). | |||||

| Van der Heijden et al. 2010, USA [99]. | 12 weeks, supervised PA (a twice a week 30-min aerobic exercise session at ≥70% of peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak)) | Primary care. Equipped laboratory in a hospital | Lean and Obese Hispanic children, median age 15 years | Intrahepatic fats change: Obese -3.3, (p<0.05). No change in the lean |

Well-controlled short-term high intensity exercise intervention is effective in reducing diabetes risk only in high risk with obesity |

| Visceral fats change: Obese -5.1, (p<0.05). No change in the lean | |||||

| Change Fasting insulin: Obese -3.6, (p<0.01). No change in the lean | |||||

| Change HOMAIR: Obese -0.8, (P<0.01). No change in the lean | |||||

| Rieder et al., 2013, USA [66]. | 6 months supervised PA (60 minutes/week moderate) and lifestyle education | Community-based | Mixed ethnic minority children, mean age 15 years | Change mean BMI (kg/m2): -0.7/month, (P<0.001) | Medium term, moderate intensity supervised PA was effective at community level in adolescents with obesity |

| Change mean BMI z scores: -0.003/month, (P<0.001) | |||||

| Hollar et al., 2010, USA [78]. | 2 years unsupervised, PA and dietary modification | School-based | Predominantly Hispanic children, mean age 7.8 years | Mena BMI: Maintained normal BMI, (p=0.02). | Longitudinal unsupervised PA with diet education was effective for maintenance of healthy BMI in minority groups |

| Eichner et al., 2016, USA [84]. | 5 years, unsupervised, unstructured PA (Walk to school and team sport) | School-based, program | Indian American, age 12 - 15 years | BMI z scores change (0.7 to 0.7) | Very long duration, unsupervised, unstructured PA maintained BMI, in American Indian adolescents |

| Dos Santos et al., 2020, USA [85]. | 8 weeks, supervised PA (vigorous, e.g lap run) | School-based | Overweight/ obese mainly Hispanic children 10-16 years | BMI (kg/m2) change (-0.51, p=0.012) | Short duration supervised high intensity PA reduced obesity in high-risk Hispanic adolescents |

| Change in waist- hip-ratio (-0.01, p<0.001) | |||||

| No significant effect of intervention | |||||

| Yin et al., 2012, USA [49]. | 18 weeks, unsupervised, unstructured PA (free play), nutrition promotion and parent’s education | Community centre and Homes | Hispanic children, mean age 4.1 years sand range 3 to 5 years | Change mean BMI z scores: -0.09, (P=0.09). | Short term low intensity PA and nutrition education targeting was ineffective in the very young Hispanic children. |

| Yin et al., 2005, USA [51]. | 24 weeks duration of intervention, but 129 days of after school PA (moderate intensity, 80min, per week) & Provision of healthy snack | School-based (school and after school sessions) | Predominantly African American children, Mean age 8.7 years | Change mean BMI (kg/m2): 0.1, (P>0.05). | Short term moderate intensity PA was ineffective in reducing obesity or its comorbidities within African Americans |

| Change % BF: -0.76, (p=0.027). | |||||

| Change FM (Kg): -0.29, (p=0.17). | |||||

| Change FFM (kg): 0.18,( p=0.12). | |||||

| Change mean WC (cm): -0.4, (p=0.32). | |||||

| Change mean SBP (mmHg): -1.8, (p=0.15). | |||||

| Change mean DBP (mmHg): -1.1, (p=0.41). | |||||

| Change mean TC (Mg/dl): -0.2, (p=0.94). | |||||

| Change mean HDL (mg/dl): 0.7, (p=0.64). | |||||

2.4.2. Randomised Control Studies

3. Discussion

3.1. Findings

3.2. Implication for Practice and Research

3.3. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Non-communicable disease. 2018 [cited 2019 1st December].

- WHO, Preventing noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) by reducing environmental risk factors. 2017, World Health Organization.

- Geneau, R., et al., Raising the priority of preventing chronic diseases: a political process. The Lancet, 2010. 376(9753): p. 1689-1698. [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.S. and S. Yusuf, Stemming the global tsunami of cardiovascular disease. The Lancet, 2011. 377(9765): p. 529-532. [CrossRef]

- Twig, G., A spotlight on obesity prevention. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 2021. 9(10): p. 645-646. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. 2019 [cited 2019 26th October 2019].

- Xiao, C. and S. Graf, Overweight, poor diet and physical activity: Analysis of trends and patterns. 2019.

- Ng, S.W. and B.M. Popkin, Time use and physical activity: a shift away from movement across the globe. Obes Rev, 2012. 13(8): p. 659-80. [CrossRef]

- Zvolinskaia, E.I., et al., [Relationship between carotid artery intima media thickness and risk factors of cardiovascular diseases in young men]. Kardiologiia, 2012. 52(8): p. 55-60.

- Yates, T., et al., A population-based cohort study of obesity, ethnicity and COVID-19 mortality in 12.6 million adults in England. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 624. [CrossRef]

- World Obesity federation. World Obesity Atlas 2023. 2023 [cited 2023 20th April].

- Morales Camacho, W.J., et al., Childhood obesity: Aetiology, comorbidities, and treatment. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, 2019. 35(8): p. e3203-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, A. and J. Tuomilehto, Lifestyle Diabetes Prevention, in Encyclopedia of Endocrine Diseases (Second Edition), I. Huhtaniemi and L. Martini, Editors. 2019, Academic Press: Oxford. p. 148-159.

- Reinehr, T., Effectiveness of lifestyle intervention in overweight children. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 2011. 70(4): p. 494-505. [CrossRef]

- Wijtzes, A.I., et al., Effectiveness of interventions to improve lifestyle behaviors among socially disadvantaged children in Europe. European Journal of Public Health, 2017. 27(2): p. 240-247. [CrossRef]

- Psaltopoulou, T., et al., Prevention and treatment of childhood and adolescent obesity: a systematic review of meta-analyses. World J Pediatr, 2019. 15(4): p. 350-381. [CrossRef]

- Weihrauch-Blüher, S., et al., Current Guidelines for Obesity Prevention in Childhood and Adolescence. Obes Facts, 2018. 11(3): p. 263-276. [CrossRef]

- Ballon, M., et al., Socioeconomic inequalities in weight, height and body mass index from birth to 5 years. Int J Obes (Lond), 2018. 42(9): p. 1671-1679. [CrossRef]

- Falconer, C.L., et al., Can the relationship between ethnicity and obesity-related behaviours among school-aged children be explained by deprivation? A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 2014. 4(1): p. e003949. [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Differences in child obesity by ethnic group. 2019 [cited 2022 22 December].

- Obita, G. and A. Alkhatib, Disparities in the Prevalence of Childhood Obesity-Related Comorbidities: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Public Health, 2022. 10: p. 923744. [CrossRef]

- Gortmaker, S.L., et al., Changing the future of obesity: science, policy, and action. Lancet, 2011. 378(9793): p. 838-47. [CrossRef]

- Hillier-Brown, F.C., et al., A systematic review of the effectiveness of individual, community and societal level interventions at reducing socioeconomic inequalities in obesity amongst children. BMC public health, 2014. 14(1): p. 834-834. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.R., et al., Racial Disparities in Obesity Treatment Among Children and Adolescents. Current Obesity Reports, 2021. 10(3): p. 342-350. [CrossRef]

- Salam, R.A., et al., Effects of Lifestyle Modification Interventions to Prevent and Manage Child and Adolescent Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 2020. 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Waters, E., et al., Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 2011(12). [CrossRef]

- Brown, T., et al., Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2019(7). [CrossRef]

- Brown, T., et al., Diet and physical activity interventions to prevent or treat obesity in South Asian children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2015. 12(1): p. 566-94. [CrossRef]

- White, M., et al., Social inequality and public health, in How and why do interventions that increase health overall widen inequalities within populations? 2009, Policy Press Bristol. p. 65-81.

- Bhopal, R., Health education and ethnic minorities. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 1991. 302(6788): p. 1338. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., et al., Adapting health promotion interventions to meet the needs of ethnic minority groups: mixed-methods evidence synthesis. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 2012. 16(44): p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M., et al., Understanding local ethnic inequalities in childhood BMI through cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected local data. BMC Public Health, 2019. 19(1): p. 1585. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D., E. Fu, and M.A. Kobayashi, Prevention and Management of Childhood Obesity and Its Psychological and Health Comorbidities. Annual review of clinical psychology, 2020. 16(1): p. 351-378. [CrossRef]

- Bhavnani, R., H.S. Mirza, and V. Meetoo, Tackling the roots of racism: Lessons for success. 2005: Policy Press. [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A., et al., The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Italian Journal of Public Health, 2009. 6(4): p. 354-391. [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M., et al., PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res, 2014. 14: p. 579. [CrossRef]

- Mazzucca, S., et al., Variation in Research Designs Used to Test the Effectiveness of Dissemination and Implementation Strategies: A Review. Frontiers in public health, 2018. 6: p. 32-32. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., et al., Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Medicine, 2009. 6(7): p. e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. and D. Altman, Assessing risk of bias in included 11 studies, in Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.0.0, J. Higgins and S. Green, Editors. 2008, The Cochrane Collaboration: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/.

- Jüni, P., D.G. Altman, and M. Egger, Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ, 2001. 323(7303): p. 42-46. [CrossRef]

- West, S., et al., Systems to Rate the Strength of Scientific Evidence: Summary., in AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries., Rockville, Editor. 2002, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11930/: USA. p. 1998-2005.

- ‘The-Cochrane-Collaboration, Review Manager (RevMan). 2020, The Cochrane Collaboration: www.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/revman/.

- Higgins JPT, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 2022 February 2022 [cited 2023 10 January].

- Higgins, J.P., et al., The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj, 2011. 343: p. d5928. [CrossRef]

- Adab, P., et al., Effectiveness of a childhood obesity prevention programme delivered through schools, targeting 6 and 7 year olds: cluster randomised controlled trial (WAVES study). BMJ, 2018. 360: p. k211. [CrossRef]

- Messito, M.J., et al., Prenatal and Pediatric Primary Care-Based Child Obesity Prevention Program: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics, 2020. 146(4). [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.N., et al., Randomized Control Trial to Improve Adiposity and Insulin Resistance in Overweight Latino Adolescents. Obesity (19307381), 2009. 17(8): p. 1542-1548. [CrossRef]

- de Heer, H.D., et al., Effectiveness and Spillover of an After-School Health Promotion Program for Hispanic Elementary School Children. American Journal of Public Health, 2011. 101(10): p. 1907-1913. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z., et al., Míranos! Look at us, we are healthy! An environmental approach to early childhood obesity prevention. Childhood obesity (Print), 2012. 8(5): p. 429-439. [CrossRef]

- Yli-Piipari, S., et al., A Twelve-Week Lifestyle Program to Improve Cardiometabolic, Behavioral, and Psychological Health in Hispanic Children and Adolescents. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 2018. 24(2): p. 132-138. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z., et al., An environmental approach to obesity prevention in children: Medical College of Georgia FitKid Project year 1 results. Obes Res, 2005. 13(12): p. 2153-61. [CrossRef]

- Wylie-Rosett, J., et al., Embedding weight management into safety-net pediatric primary care: randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2018. 15(1): p. 12. [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.W., et al., A Community-based Healthy Living Promotion Program Improved Self-esteem Among Minority Children. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, 2016. 63(1): p. 106-112. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.K., et al., The Results of the Families Improving Together (FIT) for Weight Loss Randomized Trial in Overweight African American Adolescents. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 2022. 56(10): p. 1042-1055. [CrossRef]

- Williford, H.N., et al., Exercise training in black adolescents: changes in blood lipids and Vo2max. Ethnicity & disease, 1996. 6(3-4): p. 279-285.

- Williamson, D.A., et al., Two-year internet-based randomized controlled trial for weight loss in African-American girls. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 2006. 14(7): p. 1231-1243. [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, G.-J., et al., A 12-week aerobic exercise program reduces hepatic fat accumulation and insulin resistance in obese, Hispanic adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 2010. 18(2): p. 384-390. [CrossRef]

- Tomayko, E.J., et al., The Healthy Children, Strong Families 2 (HCSF2) Randomized Controlled Trial Improved Healthy Behaviors in American Indian Families with Young Children. Current developments in nutrition, 2018. 3(Suppl 2): p. 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Taveras, E.M., et al., Comparative Effectiveness of Clinical-Community Childhood Obesity Interventions: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA pediatrics, 2017. 171(8): p. e171325. [CrossRef]

- Story, M., et al., Bright Start: Description and main outcomes from a group-randomized obesity prevention trial in American Indian children. Obesity (19307381), 2012. 20(11): p. 2241-2249. [CrossRef]

- Stolley, M.R., et al., Hip-Hop to Health Jr., an obesity prevention program for minority preschool children: baseline characteristics of participants. Preventive medicine, 2003. 36(3): p. 320-329. [CrossRef]

- Soltero, E.G., et al., Effects of a Community-Based Diabetes Prevention Program for Latino Youth with Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity (19307381), 2018. 26(12): p. 1856-1865. [CrossRef]

- Slusser, W., et al., Pediatric overweight prevention through a parent training program for 2-4 year old Latino children. Childhood obesity (Print), 2012. 8(1): p. 52-59. [CrossRef]

- Shaibi, G.Q., et al., Effects of resistance training on insulin sensitivity in overweight Latino adolescent males. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 2006. 38(7): p. 1208-1215. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.N., et al., A community-based, multi-level, multi-setting, multi-component intervention to reduce weight gain among low socioeconomic status Latinx children with overweight or obesity: The Stanford GOALS randomised controlled trial. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology, 2021. 9(6): p. 336-349. [CrossRef]

- Rieder, J., et al., Evaluation of a community-based weight management program for predominantly severely obese, difficult-to-reach, inner-city minority adolescents. Child Obes, 2013. 9(4): p. 292-304. [CrossRef]

- Resnicow, K., et al., Results of go girls: a weight control program for overweight African-American adolescent females. Obesity research, 2005. 13(10): p. 1739-1748. [CrossRef]

- Prado, G., et al., Results of a Family-Based Intervention Promoting Healthy Weight Strategies in Overweight Hispanic Adolescents and Parents: An RCT. American journal of preventive medicine, 2020. 59(5): p. 658-668. [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, H.M., et al., Effect of a Breakfast in the Classroom Initiative on Obesity in Urban School-aged Children: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 2019. 173(4): p. 326-333. [CrossRef]

- Peña, A., et al., Effects of a Diabetes Prevention Program on Type 2 Diabetes Risk Factors and Quality of Life Among Latino Youths With Prediabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open, 2022. 5(9): p. e2231196. [CrossRef]

- Novotny, R., et al., Effect of the Children's Healthy Living Program on Young Child Overweight, Obesity, and Acanthosis Nigricans in the US-Affiliated Pacific Region: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open, 2018. 1(6): p. e183896. [CrossRef]

- Norman, G., et al., Outcomes of a 1-year randomized controlled trial to evaluate a behavioral 'stepped-down' weight loss intervention for adolescent patients with obesity. Pediatr Obes, 2016. 11(1): p. 18-25. [CrossRef]

- Messito, M.J., et al., Prenatal and Pediatric Primary Care-Based Child Obesity Prevention Program: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics, 2020. 146(4): p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.A., et al., Weight loss in overweight Mexican American children: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics, 2007. 120(6): p. e1450-7. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.A., et al., Impact of a School-Based Pediatric Obesity Prevention Program Facilitated by Health Professionals. Journal of School Health, 2013. 83(3): p. 171-181. [CrossRef]

- Hull, P.C., et al., Childhood obesity prevention cluster randomized trial for Hispanic families: outcomes of the healthy families study. Pediatric obesity, 2018. 13(11): p. 686-696. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.O., et al., Twelve-Month Efficacy of an Obesity Prevention Program Targeting Hispanic Families With Preschoolers From Low-Income Backgrounds. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 2021. 53(8): p. 677-690. [CrossRef]

- Hollar, D., et al., Effective multi-level, multi-sector, school-based obesity prevention programming improves weight, blood pressure, and academic performance, especially among low-income, minority children. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 2010. 21(2): p. 93-108. [CrossRef]

- Heerman, W.J., et al., Competency-Based Approaches to Community Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Reduce Childhood Obesity among Latino Preschool-Aged Children. Childhood obesity (Print), 2019. 15(8): p. 519-531. [CrossRef]

- Hasson, R.E., et al., Randomized controlled trial to improve adiposity, inflammation, and insulin resistance in obese African-American and Latino youth. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 2012. 20(4): p. 811-818. [CrossRef]

- Haines, J., et al., Randomized trial of a prevention intervention that embeds weight-related messages within a general parenting program. Obesity (19307381), 2016. 24(1): p. 191-199. [CrossRef]

- Gatto, N.M., et al., LA sprouts randomized controlled nutrition, cooking and gardening programme reduces obesity and metabolic risk in Hispanic/Latino youth. Pediatric obesity, 2017. 12(1): p. 28-37. [CrossRef]

- Fiechtner, L., et al., Comparative Effectiveness of Clinical and Community-Based Approaches to Healthy Weight. Pediatrics, 2021. 148(4). [CrossRef]

- Eichner, J.E., O.A. Folorunso, and W.E. Moore, A Physical Activity Intervention and Changes in Body Mass Index at a Middle School With a Large American Indian Population, Oklahoma, 2004-2009. Preventing Chronic Disease, 2016. 13: p. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, H., et al., THE EFFECT OF THE SHAPEDOWN PROGRAM ON BMI, WAIST-HIP RATIO AND FAMILY FUNCTIONING - A FAMILY-BASED WEIGH-REDUCTION INTERVENTION SERVICEABLE TO LOW-INCOME, MINORITY COMMUNITIES. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 2020. 27(1): p. 22-28.

- Davis, S.M., et al., CHILE: Outcomes of a group randomized controlled trial of an intervention to prevent obesity in preschool Hispanic and American Indian children. Preventive medicine, 2016. 89: p. 162-168. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.N., et al., Effects of a randomized maintenance intervention on adiposity and metabolic risk factors in overweight minority adolescents. Pediatric obesity, 2012. 7(1): p. 16-27. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.N., et al., School-based gardening, cooking and nutrition intervention increased vegetable intake but did not reduce BMI: Texas sprouts - a cluster randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2021. 18(1): p. 18. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.N., et al., LA Sprouts: a gardening, nutrition, and cooking intervention for Latino youth improves diet and reduces obesity. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 2011. 111(8): p. 1224-1230. [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N.C., et al., Results of a multi-level intervention to prevent and control childhood obesity among Latino children: the Aventuras Para Niños Study. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 2012. 43(1): p. 84-100. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-L., et al., The Efficacy of the Web-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Program in Chinese American Adolescents (Web ABC Study). Journal of Adolescent Health, 2011. 49(2): p. 148-154. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-L., C.M. Guedes, and A.E. Lung, Smartphone-based Healthy Weight Management Intervention for Chinese American Adolescents: Short-term Efficacy and Factors Associated With Decreased Weight. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 2019. 64(4): p. 443-449. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., et al., Efficacy of a child-centred and family-based program in promoting healthy weight and healthy behaviors in Chinese American children: a randomized controlled study. Journal of Public Health, 2010. 32(2): p. 219-229. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, B., et al., Pathways: a school-based, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in American Indian schoolchildren. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2003. 78(5): p. 1030-1038. [CrossRef]

- Barkin, S.L., et al., Changing overweight Latino preadolescent body mass index: the effect of the parent-child dyad. Clinical Pediatrics, 2011. 50(1): p. 29-36. [CrossRef]

- Barkin, S.L., et al., Culturally tailored, family-centered, behavioral obesity intervention for Latino-American preschool-aged children. Pediatrics, 2012. 130(3): p. 445-456. [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, K.R., et al., Compañeros: High School Students Mentor Middle School Students to Address Obesity Among Hispanic Adolescents. Preventing chronic disease, 2017. 14: p. E92. [CrossRef]

- Arlinghaus, K.R., T.A. Ledoux, and C.A. Johnston, Randomized Controlled Trial to Increase Physical Activity Among Hispanic-American Middle School Students. The Journal of school health, 2021. 91(4): p. 307-317. [CrossRef]