1. Introduction

Ultrasonography is an easy, non-invasive method to visualize the udder parenchyma and blood flow on farm. [

1] first used amplitude-mode (A-mode) ultrasonography to examine internal structures of the udder. Two decades later, brightness-mode (B-mode) was employed to visualize the bovine udder and teat [

2]. Ever since, the physiological appearance of the glandular parenchyma and specific ultrasonographic findings under pathological conditions have been reported [

3,

4,

5]. Ultrasound has also been used to assess parenchymal development in dairy heifers [

6,

7]. Finally, the applicability of three-dimensional ultrasonography to the examination of the bovine udder has been tested and produced good quality perspective images of the mammary gland [

8].

Echotexture analysis of udder B-mode sonograms has been used to evaluate mammary parenchyma and increase the acquired information. Echotexture refers to the appearance, structure and arrangement of the parts of an object within an ultrasonographic image [

9]. Echotexture analysis employs statistical features, such as mean numerical pixel values (NPV) and pixel standard deviation (PSD) to quantify parenchymal changes depicted in grey-scale images (B-mode sonograms) due to the presence of milk or under pathological conditions [

10,

11]. In buffaloes, echotexture features were significantly correlated with milk somatic cell count (SCC) [

12]. Recently, a deep learning algorithm was trained to process udder echotexture features and predict productivity traits of dairy cows [

13].

Blood flow of the udder has been studied with invasive techniques [

14,

15,

16] and with non-invasive color Doppler ultrasonography [

17,

18,

19]. The milk vein (subcutaneous abdominal vein) is the main route of blood drainage from the udder, it plays a key role in the mammary function and is commonly used for drugs’ administration [

20,

21]. The morphology and blood flow of the milk vein have been studied with color Doppler ultrasonography in lactating Brown Swiss cows [

21,

22]. Another study compared blood flow of cows in the dry period (DP), cows with 10 kg and cows with 20 kg of daily milk yield (DMY) and found that milk yield has a profound effect on blood flow variables of the milk vein [

23].

Research has shown that udder health and productivity traits affect blood flow and echotexture. Despite being the breed with the highest milk production and worldwide spread, only a few studies have focused on Holstein cows’ udder echotexture, blood flow and morphological parameters of the milk vein [

11,

24]. There is also limited longitudinal data on changes of udder echotexture features and blood flow of the same cows throughout the period from late lactation, dry-off, udder involution during the DP, calving and early lactation. Moreover, in most studies only first order statistics (NPV and PSD) have been used to quantify udder echotexture. According to recent developments [

13,

25] second and higher-order statistics could optimize echotexture analysis of the mammary gland, but further research on this topic is necessary. Finally, there is a lack of a comprehensive approach connecting the relationships between udder parenchymal echotexture, blood flow, milk SCC –as an indicator of subclinical mastitis– and milk production, in the same study.

The present longitudinal study of clinically healthy Holstein dairy cows, starting from late lactation, throughout dry period and early lactation aimed to investigate: i) changes of morphological and blood flow parameters of the right and left milk vein, ii) udder echotexture changes with the employment of first, second and higher-order statistics, and iii) the relationships between blood flow volume in the milk vein, udder echotexture features, milk somatic cell count and milk production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (protocol number: 1399/05-04-2019). All operations were conducted in accordance with the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments and the University’s guidelines for animal research. Reporting of this observational study was conducted under STROBE-Vet reporting guideline.

Twenty-three clinically healthy, lactating, pregnant Holstein dairy cows (11 primiparous and 12 multiparous) were initially selected from one commercial herd located in the region of Thessaloniki, Greece. Cows in late and early lactation stages were housed in the same free-stall barn, in the low and high-lactation groups, respectively. They were milked twice daily with a conventional milking system and DMY was automatically recorded. They were fed a total mixed ration designed for the low and high-lactation group, respectively, offered once a day, every morning. Cows in DP were housed as far-off and close-up groups and fed total mixed rations designed for these groups, offered every morning.

Median DMY and interquartile range (IQR) at the peak of lactation was 47.3 (10.3) kg, and on the last day of lactation it was 24.3 (8.5) kg. Median duration of the dry period (IQR) was 56 (6) days. Abrupt dry-off with blanket dry cow treatment was applied using an intramammary antibiotic suspension (Nafpenzal®, Intervet International B.V., Boxmeer, Netherlands) (300 mg procaine benzylpenicillin, 100 mg nafcillin, and 100 mg dihydrostreptomycin). On entrance day in the study median age (IQR) of the cows was 4.2 (1.5) years old; 11 cows were at the end of 1st lactation, 8 were at the end of 2nd lactation, 3 were at the end of 3rd lactation and 1 was at the end of 4th lactation.

2.2. Study design and clinical examination

This observational study consisted of 17 repeated measurements performed on each of the 23 cows throughout 3 consecutive production stages starting from late lactation (7 days before dry-off and at dry-off day), during the DP (on the 3rd, 7th, 21st and 35th day of the dry period, and 7 and 3 days prior to calving) and early lactation (on calving day and on the 3rd, 7th, 14th, 30th, 45th, 60th, 75th and 90th day of the new lactation period).

All measurements took place in the middle of the time interval between morning and afternoon milking (10:00–11:00 a.m.). A thorough general physical examination was performed prior to any handling [

26]. Udder health was assessed clinically, milk was inspected visually for abnormalities and California Mastitis Test was performed on farm using a commercially available reagent (BOVIVET CMT Liquid, Jørgen Kruuse A/S, Denmark) [

27]. On each measurement day, individual cow DMY was obtained from farm data records and quarter milk SCC (qSCC) and individual cow SCC (iSCC) were recorded on farm with DeLaval Cell Counter (DeLaval International AB, Tumba, Sweden). SCC was log-transformed to somatic cell score (SCS) using the formula: SCS=3+log

2(SCC/100.000) [

28].

Cows with clinical symptoms, moderate or strong California Mastitis Test reaction and/or major pathogens isolated from their milk samples were excluded after the appearance of these conditions. Among the 23 cows initially enrolled in this study, two cows were excluded due to the appearance of clinical conditions (clinical mastitis and left displaced abomasum), all diagnosed promptly and treated successfully.

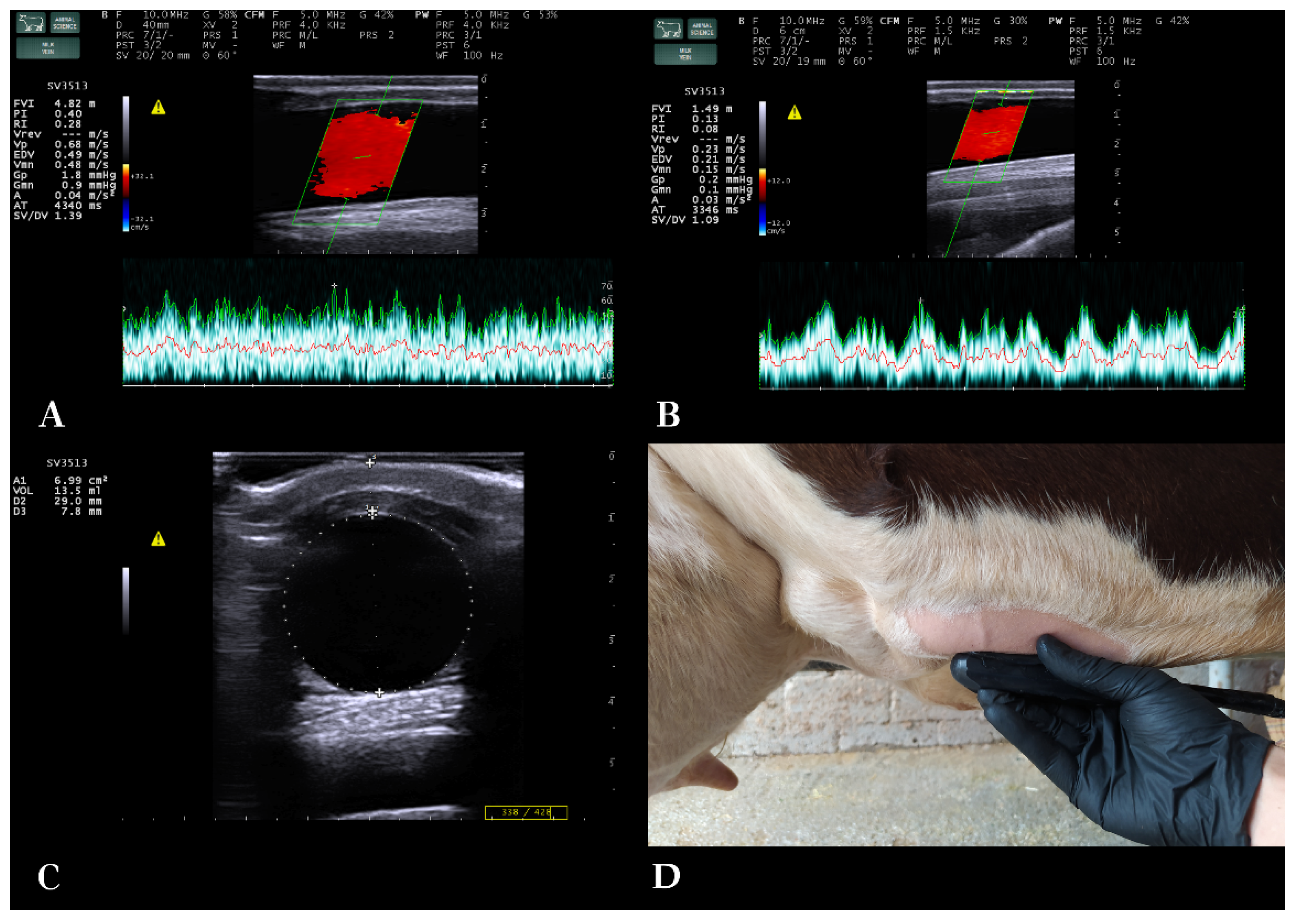

2.3. Ultrasonography of the milk vein (B-mode and spectral Doppler)

Cows were examined at standing position, non-sedated, restricted in a cattle crush, handled gently to minimize stress. Ultrasonographic examination of all cows was performed constantly by the first author. Morphology and blood flow of the milk veins were examined bilaterally with B-mode and spectral Doppler (triplex) ultrasonography, respectively. Cows had normal resting heart rate during the vascular flow examination [

29]. The same ultrasound scanner was used, equipped with a broad-bandwidth multi-frequency linear transducer (SV3513, Esaote S.p.A., Genoa, Italy; 2.5–10 MHz). B-mode frequency was 10 MHz, scanning depth was 4–6 cm, gain 58% and time-gain compensation in neutral position.

A straight part of the milk vein was selected for the measurement located at the midpoint between its cranial and caudal part. The area was shaved, washed, degreased with 70% alcohol and covered with coupling gel (

Figure 1). To avoid compression of the vein while ensuring sufficient contact, an appropriate amount of coupling gel was applied on the transducer, without the latter directly touching the skin. First, the transducer was positioned in cross-section to the vein. Distance of the milk vein from skin surface (D1) (cm), its vertical diameter from intima to intima (D2) (cm) and vein area in cross-section (A) (cm

2) were measured from B-mode images.

Then, the transducer was positioned longitudinally to the vein, and Color Doppler gate was activated and placed at the center of the milk vein. Blood flow sample volume cursor included at least 2/3

rds of the vein diameter, 16-20 mm wide, and theta angle was 60

o (

Figure 1). Blood flow was examined for 2 minutes per vein and 5 optimal spectral Doppler images were obtained from each milk vein measurement for further processing with MyLab™_Desk v. 9.0 software (Esaote S.p.A., Genoa, Italy). Blood flow parameters used were time-averaged mean velocity (TAMV) (cm/s), peak velocity (Vpeak) (cm/s) and milk vein blood flow volume (BFVol) (L/min) [

23]. The total number of spectral Doppler sonograms used was 690 [345 measurement days * 2 milk veins (right/left) per cow].

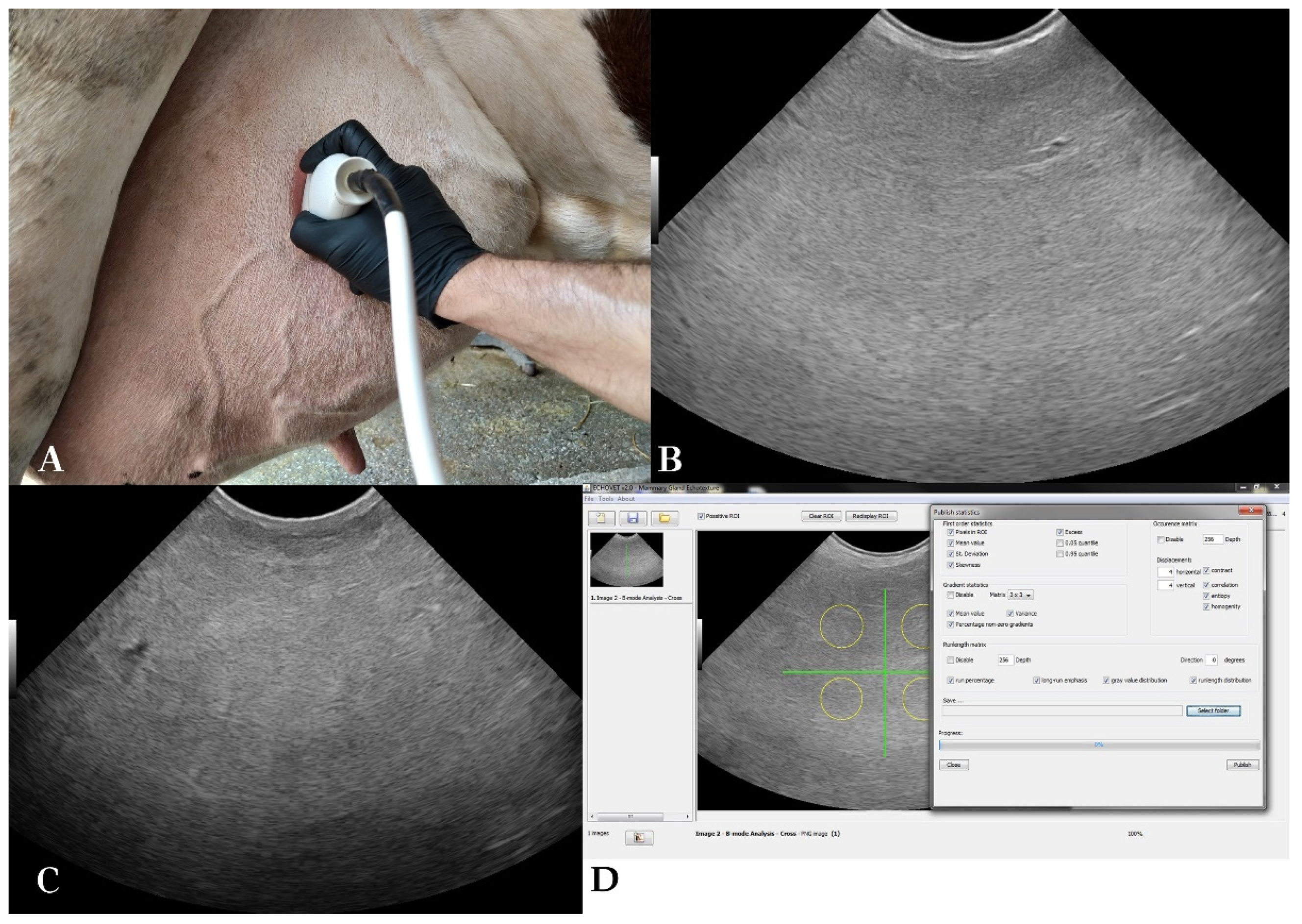

2.4. Ultrasonography and echotexture analysis of the mammary parenchyma

Udder parenchyma was examined with B-mode ultrasonography transcutaneously using a portable ultrasound scanner (MyLab™ OneVET, Esaote S.p.A., Genoa, Italy), equipped with a broad-bandwidth multi-frequency convex probe (SC3421, Esaote S.p.A., Genoa, Italy; 2.5–6.6 MHz). All four udder quarters were examined at each measurement day and two optimal B-mode images per quarter were acquired. The probe was placed in coronal plane to examine the front quarters and in sagittal plane for the rear quarters, 15–20 cm above the base of each teat (

Figure 2). Ultrasound settings remained constant throughout the scans; frequency 6.6 MHz, scanning depth of 15 cm, gain 58% and time-gain compensation in neutral position.

The total number of sonograms used was 2,760 (345 measurements x 4 udder quarters x 2 B-mode images obtained from each udder quarter). The ultrasound scanner produced images with a resolution of 720 by 540 pixels. Each pixel had one of the possible shades of grey (0 to 255). Echotexture analysis procedure presented in

Figure 2 was performed with EchoVet v.2.0 software (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece) [

25]. Each image was divided into four imaginary quarters [

30]. A circular region of approximately 5,000 pixels was manually selected within each of the image quarters. Selection criteria were physiological gland parenchyma, with medium homogeneous echogenicity, avoiding mammary vessels [

3]. The overall region of interest selected from each B-mode image was 20,000 pixels [

13].

Parenchymal echotexture in B-mode images was evaluated using 15 features: mean NPV, PSD, Skewness, Excess, Contrast, Homogeneity, Correlation, Entropy, Run Percentage, Long Run Emphasis, Grey Value Distribution, Runlength Distribution, Gradient Mean Value, Gradient Variance and Percentage of Non-zero Gradients [

13].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data quality control was performed prior to any analysis. Descriptive analyses were performed to summarize the animals’ characteristics, compared by production stage (late lactation / dry period / early lactation). Quantitative variables were described with means [standard deviation (SD)] and median (IQR). One-way ANOVA for repeated measurements was used to test for differences between production stages. Linear Mixed Effects (LME) models under the Maximum Likelihood method [

31] were employed to describe the relationship and the evolution over time between variables of the parenchymal echotexture, BFVol, DMY and SCC, taking into consideration correlations within repeated measurements.

We included random effects (random intercept and slope) for the time of measurements to improve model fitting by accounting for sources of variability that are not explained by the fixed effects in the models. We accounted for individual differences in baseline levels of the outcome variable (individual variability) and for individual differences in the rate of change over time. This is important because individuals may have different trajectories of change over time, even if they started at the same baseline level. Time was included in the models both as fixed and as random effect. Restricted cubic splines with four knots were used to estimate the time evolution curves of udder BFVol, DMY and SCS. The location of the knots was placed based on Harrell’s recommended percentages for a 4-knot RCS [

32] with knots at: 1) 7 days before dry-off, 2) 36

th day of the DP, 3) 30

th and 4) 90

th day of consecutive lactation. Interactions with time terms were investigated for all models.

All models were minimally adjusted for lactation period and RCS of time to address potential sources of bias due to confounding and capture the outcome’s non-linearity. To improve interpretability of our results we log

e transformed Grey Value Distribution and Runlength Distribution. Additionally, we rescaled Homogeneity, Correlation, Gradient Variance and Long Run Emphasis values (

Table 3 and

Table 4). Model selection procedure with backwards evaluation was performed to determine the final multivariable models, keeping variables with p≤0.10. The most significant predictor variables were identified with this method, while controlling for other variables in the models. Model selection was based on the Akaike information criterion and log-likelihood. Multicollinearity was checked for every multivariable model and collinear variables were excluded based on the highest value of Generalized Variance Inflation Factor [

33].

The general form of the LME model with a 4-knot RCS that investigated the relationship of BFVol with DMY and iSCC (Supplementary materials) was:

where Y

ij is the BFVol in the milk vein of the i

th cow at the j

th measurement day,

RCS (time)i is the restricted cubic spline with 4 knots for time for the i

th cow,

LPi is the lactation period of the i

th cow,

iSCCij is the individual somatic cell count for the i

th cow at the j

th measurement day,

DMYij is the daily milk yield of the i

th cow at the j

th measurement day,

MV_Sideij represents the right / left milk vein of the i

th cow at the j

th measurement day,

random (intercept, time)i is the random intercept and random slope for time of the i

th cow and

eij is the model errors for the i

th cow at the j

th measurement day.

The multivariable LME model formulas regarding the relationships of DMY with each of the 15 echotexture variables and of qSCS with the 15 echotexture variables, respectively, are presented in Supplementary materials. The general form of the LME models with a 4-knot RCS that investigated the relationship of DMY with each of the 15 echotexture variables and the relationship of qSCS with the 15 echotexture variables, respectively, was:

where Y

ij is the daily milk yield or the quarter somatic cell score of the i

th cow at the j

th measurement day,

RCS (time)i is the restricted cubic spline with 4 knots for time for the i

th cow,

LPi is the lactation period of the i

th cow,

Quarterij is the udder quarter of the i

th cow at the j

th measurement day,

Xij is each time one of the echotexture variables measurements of the i

th cow at the j

th measurement day,

random [intercept, RCS(time)]i is the random intercept and random slope for time of the i

th cow and

eij is the model errors for the i

th cow at the j

th measurement day.

Normality of distribution regarding residuals and random effects of the final multivariable models were graphically checked. All p-values were two-sided and significance level was set at p≤0.05. All statistical analyses, data manipulation and data visualization were performed using R programming software (version 4.2.2) (R Core Team, 2022). The “lme4” package in R programming language was used to assess convergence of the LME models.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

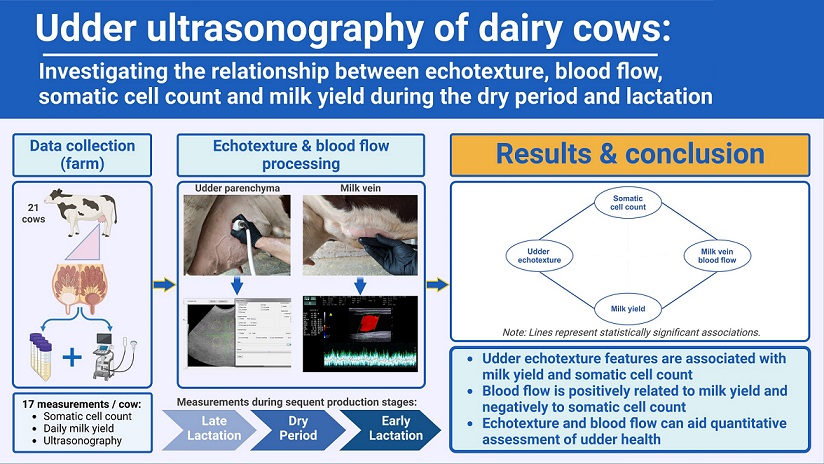

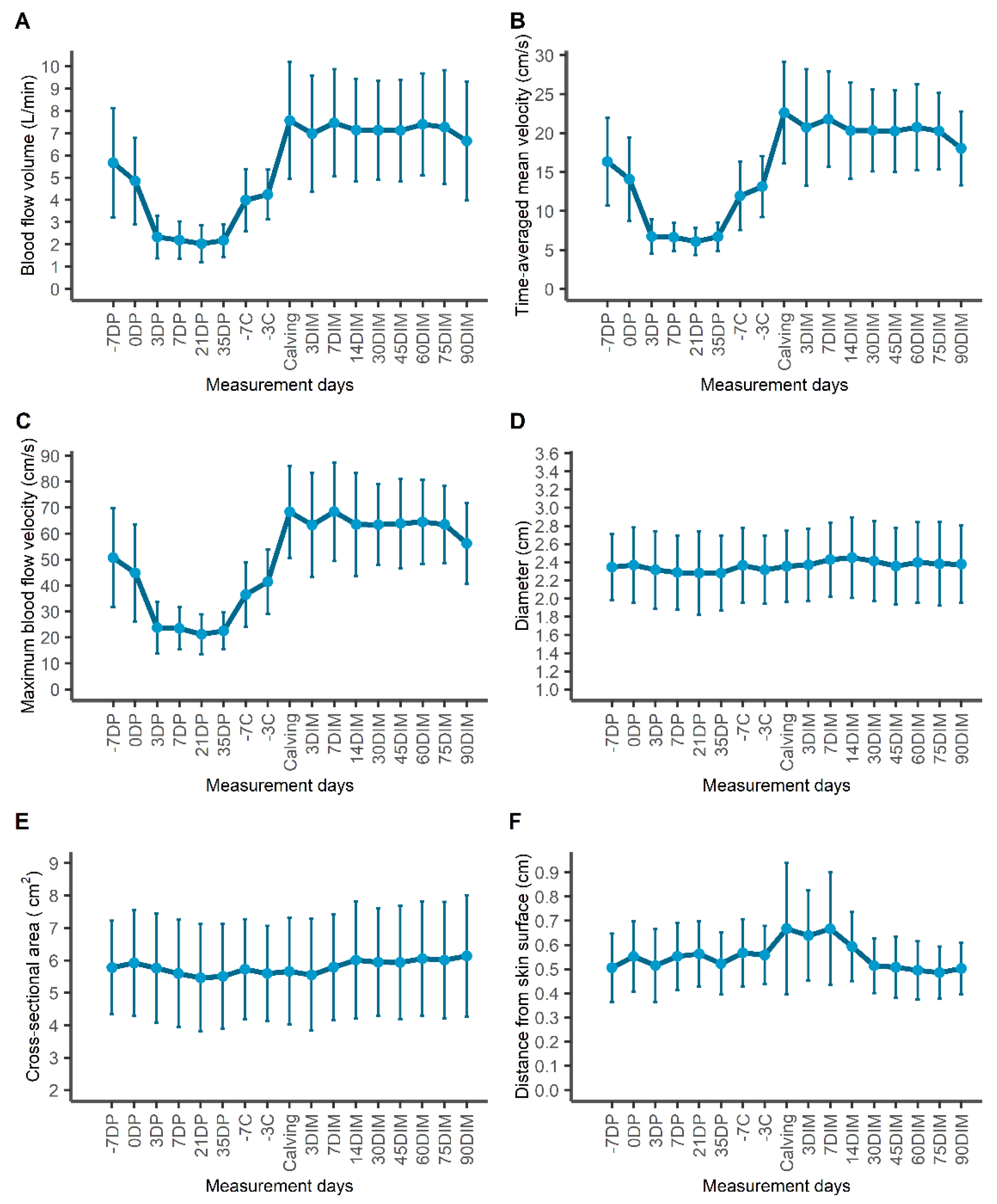

Repeated measurements from 21 clinically healthy Holstein dairy cows corre-sponding to 345 cow measurement days were included in our analysis. Changes during the study period of each of the 15 echotexture features used for the investigation of udder parenchymal changes is presented in Supplementary materials. Morphological and blood flow parameters of the milk vein throughout the study period are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 3. Distance of the milk vein from skin surface, its diameter and cross-sectional area remained constant across production stages.

A significant change was observed in the values of blood flow variables (BFVol, TAMV and Vmax) of the milk vein between late lactation, dry period and early lactation (

Table 1,

Figure 3). The highest value of mean BFVol was recorded at calving day, at 7.57±2.18 L/min and the lowest at mid-DP (21

st day in the DP). The most abrupt changes in BFVol were observed between measurements “dry-off day” and “3

rd day in DP” (decrease) and between measurements “3 days before calving” and “calving” (increase). TAMV and Vmax followed the same trend as BFVol throughout the study period.

3.2. Blood flow volume, daily milk yield and somatic cell count

The results of the univariable and multivariable LME models investigating the relationship between BFVol in the milk vein, DMY and iSCC are presented in

Table 2. A significant association was observed between BFVol and DMY in the respective multivariable model, where side of the milk vein (right/left) appeared significant, too. According to this model, BFVol in the milk vein increases by 0.25 [95% CI (0.13, 0.39)] L/min for every 1 kg increase in DMY, keeping all other variables constant. Lactation period did not significantly affect BFVol neither in univariable nor multivariable models. Individual cow SCC was significantly related with BFVol only in the univariable model. For a 1,000,000-cells/mL increase in iSCC there is a significant decrease of 0.49 L/min [95% CI (-0.97, -0.01)] in BFVol in the milk vein, keeping all other variables constant.

3.3. Udder echotexture and daily milk yield

The results of the univariable and multivariable LME models investigating the relationship between udder parenchymal echotexture parameters and DMY are presented in

Table 3. Six out of 15 echotexture parameters were significantly related with DMY in the respective univariable models: Mean NPV, PSD, Gradient Mean Value, Correlation, Excess and Skewness. The multivariable model includes 3/15 echotexture parameters: Mean NPV [est. per 1 unit increase (95%CI), 0.09 (0.03, 0.15)], mean PSD [est. per 1 unit increase (95%CI), 0.57 (0.11, 1,03)], and Long Run Emphasis [est. per 1 unit increase (95%CI), -0.23 (-0.46, -0.002)].

Table 3.

Association between daily milk yield and udder echotexture parameters using linear mixed models.

Table 3.

Association between daily milk yield and udder echotexture parameters using linear mixed models.

Outcome:

Daily Milk Yield (kg) |

Univariable

Model’s estimates

(95% C.I.) 1

|

p-value |

Multivariable

model's estimates

(95% C.I.) 1

|

p-value |

| Mean Numerical Pixel Value |

0.11 (0.05, 0.16) * |

<0.01 |

0.09 (0.03, 0.15) * |

0.003 |

| Mean Pixel Standard Deviation |

0.72 (0.28, 1.18) * |

<0.01 |

0.57 (0.11, 1,03) * |

0.01 |

| Gradient Mean Value |

0.30 (0.15, 0.47) * |

<0.01 |

|

|

| Contrast |

0.007 (-0.01, 0.03) |

0.554 |

|

|

| Correlation2 |

-3.73 (-6.14, -1.48) * |

<0.01 |

|

|

| Homogeneity3 |

-0.86 (-3.13, 1.40) |

0.454 |

|

|

| Run Percentage |

1.22 (-1.60, 4.04) |

0.397 |

|

|

| Gradient Variance4 |

1.96 (-0.06, 3.98) |

0.057 |

|

|

| Grey Value Distribution5 |

-1.28 (-8.75, 6.18) |

0.736 |

|

|

| Runlength Distribution5 |

-1.16 (-8.72, 6.39) |

0.763 |

|

|

| Entropy |

0.59 (-4.98, 6.17) |

0.835 |

|

|

| Excess |

-5.86 (-8.68, -3.05) * |

<0.01 |

|

|

| Percentage Non-zero Gradients |

-0.46 (-2.29, 1.36) |

0.619 |

|

|

| Long Run Emphasis3 |

-0.15 (-0.33, 0.02) |

0.087 |

-0.23 (-0.46, -0.002) * |

0.048 |

| Skewness |

-4.25 (-6.27, -2.23) * |

<0.01 |

|

|

3.4. Udder echotexture and somatic cell score

The results of the univariable and multivariable LME models investigating the relationship between udder parenchymal echotexture parameters and udder quarter SCS are presented in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Association between udder quarter somatic cell score and udder echotexture parameters using linear mixed models.

Table 4.

Association between udder quarter somatic cell score and udder echotexture parameters using linear mixed models.

Outcome:

quarter Somatic Cell Score |

Univariable

Model’s estimates

(95% C.I.) 1

|

p-value |

Multivariable

model's estimates

(95% C.I.) 1

|

p-value |

| Mean Numerical Pixel Value |

0.005 (-0.01, 0.02) |

0.623 |

-0.07 (-0.12, -0.02) * |

<0.01 |

| Mean Pixel Standard Deviation |

0.27 (0.10, 0.44) * |

<0.01 |

0.72 (0.43, 1.00) * |

<0.01 |

| Gradient Mean Value |

0.04 (-0.02, 0.10) |

0.196 |

0.17 (0.05, 0.30) * |

<0.01 |

| Contrast |

0.001 (-0.007, 0.010) |

0.725 |

|

|

| Correlation2 |

-1.18 (-2.02, -0.33) * |

<0.01 |

|

|

| Homogeneity3 |

-0.13 (-0.97, 0.71) |

0.761 |

-1.23 (-2.19, -0.28) * |

0.01 |

| Run Percentage |

0.27 (-0.79, 1.34) |

0.615 |

|

|

| Gradient Variance4 |

0.05 (-0.71, 0.82) |

0.890 |

-2.50 (-3.75, -1.26) * |

<0.01 |

| Grey Value Distribution5 |

0.36 (-2.42, 3.15) |

0.798 |

|

|

| Runlength Distribution5 |

0.49 (-2.32, 3.31) |

0.731 |

|

|

| Entropy |

-0.72 (-2.82, 1.36) |

0.493 |

-4.36 (-6.95, -1.79) * |

<0.01 |

| Excess |

-0.52 (-1.57, 0.51) |

0.323 |

|

|

| Percentage Non-zero Gradients |

0.0005 (-0.68, 0.68) |

0.998 |

|

|

| Long Run Emphasis3 |

-0.014 (-0.082, 0.053) |

0.677 |

|

|

| Skewness |

-0.27 (-0.10, 0.46) |

0.465 |

|

|

Two out of 15 echotexture parameters had a significant association with qSCS in the respective univariable models: Mean PSD and Correlation. However, in the multivariable model, 6/15 echotexture parameters were found significant: Mean NPV [est. per 1 unit increase (95%CI), -0.07 (-0.12, -0.02)], PSD [est. per 1 unit increase (95%CI), 0.72 (0.43, 1.00)], Gradient Mean Value [est. per 1 unit increase (95%CI), 0.17 (0.05, 0.30)], Homogeneity [est. per 1 unit increase (95%CI), -1.23 (-2.19, -0.28)], Gradient Variance [est. per 1 unit increase (95%CI), -2.50 (-3.75, -1.26)], and Entropy [est. per 1 unit increase (95%CI), -4.36 (-6.95, -1.79)].

4. Discussion

Ultrasonography was employed to examine dairy cows’ udder parenchyma and blood flow repeatedly from late lactation, throughout the DP and early lactation. This period is very demanding for the udder as it transits from a state of milk synthesis to involution and, through intense growth, back to high milk production [

34]. This interval is also crucial for udder health because it is related to high infection risk [

35]. In this study we recorded echotextural changes of the mammary parenchyma, as well as changes in morphology and blood flow features of the milk vein throughout the above period. Also, we investigated the associations between udder parenchymal echotexture, blood flow in the milk vein, somatic cell count and milk yield of Holstein dairy cows.

Venous morphological parameters remained constant throughout late lactation, dry period and early lactation stage, despite significant changes in BFVol (

Table 1). Change in BFVol is related to milk synthesis taking place in the mammary gland during late and early lactation, respectively. Indeed, in our linear mixed model BFVol appeared significantly associated both with DMY and production stage (

Table 2). This is also apparent in the change of BFVol and DMY in time, as BFVol follows the curve of milk production: a rapid decrease within 3 days after the abrupt dry-off, followed by a stationary (non-lactating) period and then a rapid increase in BFVol one week before calving (

Figure 3), when parenchymal re-growth and milk synthesis take place. Given the calculation formula BFVol = TAMV × 60 × A [

18], the increased blood supply during lactation was achieved by increased flow velocities (TAMV, Vmax), while venous diameter and cross-sectional area remained constant. This explains why BFVol, TAMV and Vmax curves throughout the study period presented almost identical trends.

Our results agree with [

18] who observed a significant correlation between DMY and BFVol, and with [

23] who found that lactating cows had significantly higher BFVol than dry cows. Brown Swiss cows’ diameter of the milk vein recorded in [

23] was smaller than Holstein cows in our study, with no significant difference regarding production status in both studies. Even though BFVol of both right and left milk vein did not differ significantly in [

23], we included the “side” parameter in our linear mixed model, as it appeared significant. The presence of this parameter in the model formula improves its performance. This is explained by the variability in udder quarter milk yield contribution to the total DMY throughout a lactation period [

36], affecting BFVol of each side, too. Finally, mean BFVol values of the milk vein reported by [

24] are higher than our findings and [

22,

23]. This could be due to the different technique applied in that study, measuring blood flow in cross-section instead of longitudinal section of the vein.

A significant association was observed in the BFVol–iSCC univariable model, where measurement day (corresponding to production stage) was significant, too. Cows with elevated iSCC present lower DMY [

37,

38,

39,

40], which in turn is significantly associated with BFVol, as discussed above. The lower DMY and its impact on BFVol could possibly explain the reduced BFVol in cows with elevated iSCC. Further research could be based on these clinical observations to distinguish cause and consequence in BFVol–DMY–SCC relationship, and to fully understand how subclinical mastitis affects udder blood flow.

Echotexture of the mammary parenchyma is subject to changes from dry-off, throughout the DP, regrowth and high lactation [

41]. Milk quantity, histomorphology of the udder and ultrasound transducer frequency have an impact on mean NPV and PSD of dairy sheep’s udder sonograms [

42]. Milk quantity affects the echotexture features of dairy cows’ udder sonograms and removal of the hypoechoic milk alters parenchymal echotexture of the mammary gland [

11]. In our multivariable model (

Table 3) milk yield and production stage were significantly associated with changes in echotexture features (NPV, PSD and Long Run Emphasis). The variability of milk quantity contained in the mammary parenchyma among different production stages could explain the significant changes in echotexture features throughout the study period. A limitation of our study was the lack of quarter-level DMY data that could aid optimal fitting of the model. Future studies could focus on udder quarter echotextural differences utilizing quarter milk yield data produced from automatic milking systems to optimize the models’ predictive accuracy.

Normally, udder parenchyma is uniformly echogenic, whereas milk appears anechoic. Mastitis milk has elevated cellular content leading to increased milk echogenicity. Subclinical mastitis also leads to elevated SCC, and, in chronic cases, it may induce changes in the mammary parenchyma [

39], resulting in increased presence of echogenic connective tissue [

3,

4]. In our multivariable model (

Table 4), quarter SCS was significantly associated with NPV, PSD, Gradient Mean Value, Homogeneity, Gradient Variance and Entropy, whilst udder quarter and time were significant, too. [

12] studied buffaloes and also found that echotexture features (NPV and PSD) were significantly affected by SCC, lactation stage, scanning plane and udder quarter. These results indicate that echotexture analysis could aid the detection of subclinical mastitis-induced alterations of the mammary parenchyma. To optimize models’ accuracy, future research should focus on the impact of udder quarter, examination before/after milking, age/lactation period, ultrasound scanning plane and scanner device technical specifications on udder echotexture models.

Our study attempted to connect the dots between udder echotexture and blood flow in the milk vein with milk production and somatic cell count. Based on these results, echotexture analysis could potentially be applied for early diagnosis of subclinical mastitis in lactation, it could aid the assessment of parenchymal alterations due to chronic subclinical mastitis and suggest a novel method to detect parenchymal alterations due to subclinical mastitis in the DP. Finally, this comprehensive approach on udder ultrasonography, combined with deep learning algorithms [

13] could lead to sophisticated models evaluating udder health and productivity in the direction of precision dairy farming.

5. Conclusions

Ultrasonographic examination of the mammary parenchyma and milk veins is a practical, non-invasive method on farm site. Blood flow parameters in the milk vein change significantly throughout late lactation, dry period and early lactation, corresponding to lactation needs, while morphological parameters remain constant. In order to serve these needs BFVol in the milk vein increases by 0.25 L/min for every 1 kg increase in DMY, keeping all other variables constant. The presence of elevated SCC in milk is associated with decreased BFVol in the milk vein. Certain echotexture parameters are significantly associated with DMY and SCC , respectively. These parameters can be used to evaluate udder health and productivity. Second and higher-order statistical parameters can provide useful information on udder echotexture. Finally, udder echotexture and blood flow examination can contribute to the quantitative assessment of udder health in the direction of precision dairy farming.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org: 1) Video S1: color Doppler ultrasonographic examination of the blood flow in the milk vein of a cow; Figures presenting the progress of the 15 echotexture parameters throughout the study period: 2) Mean NPV; 3) PSD; 4) Skewness; 5) Entropy; 6) Run Percentage; 7) Correlation; 8) Runlength Distribution; 9) Contrast; 10) Percentage Non Zero Gradients; 11) Excess; 12) Gradient Mean Value; 13) Gradient Variance; 14) Grey Value Distribution; 15) Long Run Emphasis; 16) Homogeneity.

Author Contributions

K.S.T.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing I.P.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft N.P.: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing A.Z.: Writing – review & editing E.K.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The doctoral thesis of Konstantinos Themistokleous was co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Social Fund), through the Operational Program "Human Resource Development, Education and Lifelong Learning", 2014-2020, under the Action "Strengthening human resources through the implementation of Ph.D. Research, Sub-Action 2: IKY Scholarships Program for Ph.D. Candidates of Greek Universities". Grant No: 2022-050-0502-52155.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (protocol number: 1399/05-04-2019). All operations were conducted in accordance with the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments and the University’s guidelines for animal research.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the American Farm School Thessaloniki for their collaboration. The graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A

We present the analytical versions of the models’ general equations presented in the main text:

-

1.

Blood flow volume, daily milk yield and somatic cell count

where BFVol

ij is the blood flow volume in the milk vein for cow i at measurement day j,

is the random intercept for each cow,

is the random error of the cow i at measurement day j,

, k=1,2,3 are restricted cubic splines with four- knot terms,

is the corresponding random effect of time, DMY is the daily milk yield for cow i at measurement day j, iSCC is the individual cow somatic cell count for cow i at measurement day j, LP

2, LP

3 and LP

4 are the second, third and fourth lactation periods, MV_Side is the left/right milk vein of the i cow at measurement day j and β

10, β

11, β

12 are the interaction effects.

-

2.

Udder echotexture and daily milk yield

where DMY

ij is the daily milk yield for cow i at measurement day j,

is the random intercept for each cow,

is the random error of the cow i at measurement dai j,

,k=1,2,3 are restricted cubic splines with four- knot terms,

,

,

are restricted cubic splines with four-knot terms and

,

,

are the corresponding random effects, NPV is the Mean Value for cow i at measurement day j, LRE is the LongRun Emphasis for cow i at measurement day j, PSD is the Pixel standard deviation for cow i at measurement day j, LP

2, LP

3 and LP

4 are the second, third and fourth lactation periods and Quarter

B, Quarter

C, Quarter

D are the quarters of udder.

-

3.

Udder echotexture and somatic cell score

where SCS

ij is the udder quarter somatic cell score for cow i at measurement day j,

is the random intercept for each cow,

is the random error of the cow i at measurement dai j,

,k=1,2,3 are restricted cubic splines with four- knot terms,

,

,

are restricted cubic splines with four-knot terms and

,

,

are the corresponding random effects, NPV is the Mean Value for cow i at measurement day j, PSD is the Pixel standard deviation for cow i at measurement day j, GMV is the Gradient mean value for cow i at measurement day j, HG is the Homogeneity for cow i at measurement day j, GradVar is the Gradient variance for cow i at measurement day j, ENT is the Entropy for cow i at measurement day j, LP

2, LP

3 and LP

4 are the second, third and fourth lactation periods and Quarter

B, Quarter

C, Quarter

D are the quarters of udder.

References

- Caruolo, E. V.; Mochrie, R.D. Ultrasonograms of Lactating Mammary Glands. J Dairy Sci 1967, 50, 225–230. [CrossRef]

- Cartee, R.E.; Ibrahim, A.K.; McLeary, D; B-Mode Ultrasonography of the Bovine Udder and Teat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986, 188(11):1284-7, PMID: 3522514.

- Flöck, M.; Winter, P. Diagnostic Ultrasonography in Cattle with Diseases of the Mammary Gland. The Veterinary Journal 2006, 171, 314–321. [CrossRef]

- Franz, S.; Floek, M.; Hofmann-Parisot, M. Ultrasonography of the Bovine Udder and Teat. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 2009, 25, 669–685. [CrossRef]

- Gundling, N.; Drummer, C.; Lüpke, M.; Hoedemaker, M. Quantitative Measurement of Udder Oedema in Dairy Cows Using Ultrasound to Monitor the Effectiveness of Diuretic Treatment with Furosemide. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 2021, 164, 767–777. [CrossRef]

- Esselburn, K.M.; Hill, T.M.; Bateman, H.G.; Fluharty, F.L.; Moeller, S.J.; O’Diam, K.M.; Daniels, K.M. Examination of Weekly Mammary Parenchymal Area by Ultrasound, Mammary Mass, and Composition in Holstein Heifers Reared on 1 of 3 Diets from Birth to 2 Months of Age. J Dairy Sci 2015, 98, 5280–5293. [CrossRef]

- Albino, R.L.; Guimarães, S.E.F.; Daniels, K.M.; Fontes, M.M.S.; Machado, A.F.; dos Santos, G.B.; Marcondes, M.I. Technical Note: Mammary Gland Ultrasonography to Evaluate Mammary Parenchymal Composition in Prepubertal Heifers. J Dairy Sci 2017, 100, 1588–1591. [CrossRef]

- Franz, S.; Hofmann-Parisot, M.M.; Baumgartner, W. Evaluation of Three-Dimensional Ultrasonography of the Bovine Mammary Gland. Am J Vet Res 2004, 65, 1159–1163. [CrossRef]

- Castellano, G.; Bonilha, L.; Li, L.M.; Cendes, F. Texture Analysis of Medical Images. Clin Radiol 2004, 59, 1061–1069. [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Simplício, K.; Sanchez, D.; Coutinho, L.; Teixeira, P.; Barros, F.; Almeida, V.; Rodrigues, L.; Bartlewski, P.; Oliveira, M.; et al. B-Mode and Doppler Sonography of the Mammary Glands in Dairy Goats for Mastitis Diagnosis. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2015, 50, 251–255. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, T.; Scheeres, N.; Małopolska, M.M.; Murawski, M.; Agustin, T.D.; Ahmadi, B.; Strzałkowska, N.; Rajtar, P.; Micek, P.; Bartlewski, P.M. Associations between Mammary Gland Echotexture and Milk Composition in Cows. Animals 2020, 10, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ahmad, M.J.; An, Z.; Niu, K.; Wang, W.; Nie, P.; Gao, S.; Yang, L. Relationship Between Somatic Cell Counts and Mammary Gland Parenchyma Ultrasonography in Buffaloes. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Themistokleous, K.S.; Sakellariou, N.; Kiossis, E. A Deep Learning Algorithm Predicts Milk Yield and Production Stage of Dairy Cows Utilizing Ultrasound Echotexture Analysis of the Mammary Gland. Comput Electron Agric 2022, 198, 106992. [CrossRef]

- Kronfeld, S.D.; Raggi, F.; Ramberg, C.F.J. Mammary Metabolism Blood Flow and Ketone Body in Normal , Fasted , and Ketotic Cows. American Journal of Physiology 1968, 215, 218–227. [CrossRef]

- Gorewit, R.C.; Aromando, M.C.; Bristol, D.G. Measuring Bovine Mammary Gland Blood Flow Using a Transit Time Ultrasonic Flow Probe. J Dairy Sci 1989, 72, 1918–1928. [CrossRef]

- Delamaire, E.; Guinard-Flament, J. Increasing Milking Intervals Decreases the Mammary Blood Flow and Mammary Uptake of Nutrients in Dairy Cows. J Dairy Sci 2006, 89, 3439–3446. [CrossRef]

- Piccione, G.; Arcigli, A.; Fazio, F.; Giudice, E.; Caola, G. Pulsed Wave–Doppler Ultrasonographic Evaluation of Mammary Blood Flows Speed in Cows during Different Productive Periods. Acta Sci Vet 2004, 32, 171–175. [CrossRef]

- Götze, A.; Honnens, A.; Flachowsky, G.; Bollwein, H. Variability of Mammary Blood Flow in Lactating Holstein-Friesian Cows during the First Twelve Weeks of Lactation. J Dairy Sci 2010, 93, 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Potapow, A.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Schmauder, S.; Friker, J.; Nautrup, C.P.; Mehne, D.; Petzl, W.; Zerbe, H. Investigation of Mammary Blood Flow Changes by Transrectal Colour Doppler Sonography in an Escherichia Coli Mastitis Model. Journal of Dairy Research 2010, 77, 205–212. [CrossRef]

- Kjœrsgaard, P. Mammary Blood Flow and Venous Drainage in Cows. Acta Vet Scand 1974, 15, 179–187. [CrossRef]

- Braun, U.; Hoegger, R. B-Mode and Colour Doppler Ultrasonography of the Milk Vein in 29 Healthy Swiss Braunvieh Cows. Vet Rec 2008, 163, 47–49.

- Braun, U.; Forster, E.; Bleul, U.; Hässig, M.; Schwarzwald, C. B-Mode and Colour Doppler Ultrasonography of the Milk Vein and Musculophrenic Vein in Eight Cows during Lactation. Res Vet Sci 2013, 94, 138–143. [CrossRef]

- Braun, U.; Forster, E. B-Mode and Colour Doppler Sonographic Examination of the Milk Vein and Musculophrenic Vein in Dry Cows and Cows with a Milk Yield of 10 and 20 Kg. Acta Vet Scand 2012, 54, 15. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Mutinati, M.; Minoia, G.; Spedicato, M.; Pantaleo, M.; Sciorsci, R.L. The Impact of Oxytocin on the Hemodynamic Features of the Milk Vein in Dairy Cows: A Color Doppler Investigation. Res Vet Sci 2012, 93, 983–988. [CrossRef]

- Ntemka, A.; Tsakmakidis, I.; Boscos, C.; Theodoridis, A.; Kiossis, E. The Role of Ewes ’ Udder Health on Echotexture and Blood Flow Changes during the Dry and Lactation Periods. Animals 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.G.G.;; Cockcroft, P.D. Clinical Examination of Farm Animals; 1st ed.; Blackwell Science Ltd: Oxford, UK; 2002; Online ISBN: 9780470752425. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.S.; Amarante, A.F.; Correia, L.B.N.; Guerra, S.T.; Nobrega, D.B.; Latosinski, G.S.; Rossi, B.F.; Rall, V.L.M.; Pantoja, J.C.F. Diagnostic Accuracy of Somaticell, California Mastitis Test, and Microbiological Examination of Composite Milk to Detect Streptococcus Agalactiae Intramammary Infections. J Dairy Sci 2018, 101, 10220–10229. [CrossRef]

- Barnouin, J.; Chassagne, M.; Bazin, S.; Boichard, D. Management Practices from Questionnaire Surveys in Herds with Very Low Somatic Cell Score Through a National Mastitis Program in France. J Dairy Sci 2004, 87, 3989–3999. [CrossRef]

- Kline, D.D.; Hasser, E.M.;; Heesch, C.M. Regulation of the Heart; In: Reece W.O. Ed. Dukes’ Physiology of Domestic Animals; 13th Ed.; 2015, John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Ames, Iowa 50010, USA, ISBN 978-1-118-50139-9.

- Schmauder, S.; Weber, F.; Kiossis, E.; Bollwein, H. Cyclic Changes in Endometrial Echotexture of Cows Using a Computer-Assisted Program for the Analysis of First- and Second-Order Grey Level Statistics of B-Mode Ultrasound Images. Anim Reprod Sci 2008, 106, 153–161. [CrossRef]

- Molengerghs, G.; Verbeke, G. Models for Discrete Longitudinal Data; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2005; ISBN 0-387-25144-8.

- Harrell, F.E. Regression Modeling Strategies; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-19424-0.

- Fox, J.; Monette, G. Generalized Collinearity Diagnostics. J Am Stat Assoc 1992, 87, 178–183. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, S.P.; Sordillo, L.M. Udder Health in the Periparturient Period. J Dairy Sci 1988, 71, 2584–2606. [CrossRef]

- Dufour, S.; Dohoo, I.R. Monitoring Dry Period Intramammary Infection Incidence and Elimination Rates Using Somatic Cell Count Measurements. J Dairy Sci 2012, 95, 7173–7185. [CrossRef]

- Penry, J.F.; Crump, P.M.; Hernandez, L.L.; Reinemann, D.J. Association of Quarter Milking Measurements and Cow-Level Factors in an Automatic Milking System. J Dairy Sci 2018, 101, 7551–7562. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, J.W.; Thurmond, M.C.; Lasslo, L. Relationship between Test-Day Measures of Somatic Cell Count and Milk Production in California Dairy Cows. Can J Vet Res 1989, 53, 182–187.

- Koldeweij, E.; Emanuelson, U.; Janson, L. Relation of Milk Production Loss to Milk Somatic Cell Count. Acta Vet Scand 1999, 40, 47–56. [CrossRef]

- Green, L.E.; Schukken, Y.H.; Green, M.J. On Distinguishing Cause and Consequence: Do High Somatic Cell Counts Lead to Lower Milk Yield or Does High Milk Yield Lead to Lower Somatic Cell Count? Prev Vet Med 2006, 76, 74–89. [CrossRef]

- Hagnestam-Nielsen, C.; Emanuelson, U.; Berglund, B.; Strandberg, E. Relationship between Somatic Cell Count and Milk Yield in Different Stages of Lactation. J Dairy Sci 2008, 92, 3124–3133. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ponchon, B.; Lanctôt, S.; Lacasse, P. Invited Review: Accelerating Mammary Gland Involution after Drying-off in Dairy Cattle. J Dairy Sci 2019, 102, 6701–6717. [CrossRef]

- Murawski, M.; Schwarz, T.; Jamieson, M.; Ahmad, B.; Bartlewski, P.M. Echotextural Characteristics of the Mammary Gland during Early Lactation in Two Breeds of Sheep Varying in Milk Yields. Anim Reprod 2019, 16, 853–858. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).