1. Introduction

Since its discovery in November 2019, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has infected an estimated 200 million people around the world and been responsible for more than 4 million deaths worldwide [

1]. As it spread rapidly across continents, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared in March 2020 that the COVID-19 pandemic was one of the global health issues of concern [

2].The WHO has also requested early identification, the isolation and management of patients, tracking of contacts and social distancing to interrupt the transmission chain [

3].

The spread of COVID-19, the increasing number of patients and the complications of the disease have imposed high medical costs on both patients and the healthcare system [

4]. Although costs vary depending on several factors such as the number of infected persons, the severity of the disease, the average length of hospitalization, and the average length of stay in the intensive care unit [

5,

6], international studies have shown that the economic burden of direct medical costs for patients with COVID-19 has been significantly higher than for other infectious diseases due to higher mortality and a higher likelihood of hospitalization [

7].

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on health systems around the world and Romania is no exception. In this country, the health system was already dealing with many difficulties before the pandemic, including a lack of medical staff, equipment, and funding [

8]. The COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened these problems and highlighted the need for health system reform in Romania [

9]. There has been no specific treatment for SARS-COV-2 and tremendous efforts have been made to find an effective treatment to reduce both morbidity and mortality [

10].

The impact on healthcare expenditure for pregnant women has been considerable, especially in tertiary centers providing only COVID, where specialized care is provided. The increased need for healthcare facilities during the pandemic has put a strain on the health system, leading to increased expenditure [

11].

A contributory factor to the rising costs of healthcare is the need for personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare professionals [

11]. Pregnant women are considered at higher risk for COVID-19, and the use of PPE has become routine for healthcare workers. The cost of PPE has increased due to increased demand and lack of availability, which has been passed on to patients in the form of greater healthcare costs [

12].

In addition, many hospitals have implemented additional safety measures such as increased testing and isolation protocols for pregnant women. These measures have resulted in longer hospital stays and additional medical procedures, which have contributed to the rise in healthcare costs [

5].

The aim of this study is to analyze the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on healthcare costs, in particular by managing cases in COVID-only maternity.

2. Materials and Methods

The objective of the study was to analyze if the model adopted by the health system consisting in complete separation of delivering obstetrical care for covid and non-covid patients was efficient. We conducted an observational study in which we compared a group of pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 (study group) with a control group in which we included uninfected pregnant women. The patients were recruited from Bucur Maternity Hospital, declared a COVID-only center in March 2020. The patients in the study group were recruited throughout the pandemic, from March 2020- March 2022.

Patients were included after written informed consent was obtained and the study received ethical committee approval.

Inclusion criteria for the study group were: gestational age between 24 and 40 weeks, RT-PCR test or Antigen test positive for SARS-CoV-2, live fetus, singleton pregnancies and patients who gave birth.

Inclusion criteria for the control group were: gestational age between 24 and 40 weeks, live fetus, singleton pregnancies, patients who gave birth.

Exclusion criteria: age under 16 years old, patients who requested discharge on demand, stillbirth.

The studied parameters were: maternal age, gestational age, type of test for SARS-CoV-2, days of infection, type of birth, presence of symptoms (cough, fever, chills, shortness of breath and other uncommon symptoms) , the severity of infection, antiviral treatment, days in Intensive Care Unit (ICU), number of hospital days, expense report for hospitalization, treatment, medical supplies, and blood tests. All information were obtained from the patient's observation record and from the expense report attached to the discharge notes.

In order to prove the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the healthcare system, we compared the results obtained from infected patients with a group that included all pregnant women who gave birth between January 2019 – January 2020.

Data analysis was performed with the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) v. 19.0. We analyzed the characteristics of all patients using descriptive statistic tests of each group separately. Pearson’s correlation was used as appropriate and two-sided p values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

After inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, the study included 300 patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection who gave birth in the pandemic, and 300 patients in the control group.

In the study group, the mean maternal age was 30,58 years vs 27,36 years in the control group, so we can observe an increase in maternal age during the pandemic period. In the COVID-19 period there were hospitalized 10% patients with pregnancy under 37 weeks of gestation, in comparison with only 4,62% non-COVID-19 patients. As can be seen, during the pandemic period there were significant differences, especially in the type of birth, i.e. a significant increase in the incidence of cesarean section compared to the non-COVID period (81,36% vs 63,32%)(

Table 1).

According to

Table 1, the average number of days of hospitalization in these years is 5,65 days, lower than in the non-COVID-19 period, i.e. 6,88 days.

Even if the average hospitalization days were shorter during the pandemic period, according to

Table 1 we can see a significant increase in hospitalization costs (16147,152 RON vs 8135,459 RON), almost double. As it can be seen, the biggest differences appear in medication costs (966,456 RON vs 209,778 RON), especially in terms of the introduction of antivirals in most treatment plans, in the costs of sanitary materials (29933,637 RON vs 175,631 RON), the increase is determined by the introduction of compulsory equipment consisting of overalls or reinforced gowns and FFP2 or FFP3 masks. The cost of medical investigations also increased by 4 times, because a long list of blood tests was required to determine the appropriate treatment, which was repeated to monitor the evolution of the patients, and most patients underwent chest X-rays and CT scans.

Table 2 illustrates the distribution of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients according to COVID vaccination, disease severity, and evolution during hospitalization. As can be seen, a very small percentage of patients were vaccinated against COVID-19, i.e. 16,8%; 26,1% were patients with moderate and severe forms, and 94,7% had a favorable evolution during hospitalization.

According to

Table 1, we found a significant increase in all costs for SARS-CoV-2 positive patients. Under these conditions in

Table 3 it can be visualized which factors have caused the high expenses during the pandemic period. As far as medication costs are concerned, it can be seen that these have increased not only by increasing the percentage of antibiotics (97.5% vs. 63.3%), but also by the constant addition of corticosteroids (66.7%) and antivirals (8.3%), drugs which in non-COVID cases were administered in certain cases such as the threat of premature birth (corticosteroids - 3.9%) or were never administered (antivirals).

The average length of intensive care unit stay for positive patients was 2,18 days, with a maximum of 15 days, in comparison with only 0,68 days in non-COVID cases. All patients with severe COVID-19, i.e. 15.1%, were admitted to the intensive care unit for more than 5 days, during which time they received mechanical ventilation support.

The tripling of the costs noted in

Table 1 can be explained by an increase in the number of investigations per patient in the case of infected pregnant women.

Table 3 shows a much higher percentage of chest X-rays (63.3%) performed routinely in moderate and severe cases of COVID-19, as well as an increase in the number of blood investigations per patient (1 set- 36.7% vs 63.4%; 2 sets- 53.5% vs 33.2%; ≥ 3 sets- 9.8% vs 3.4%).

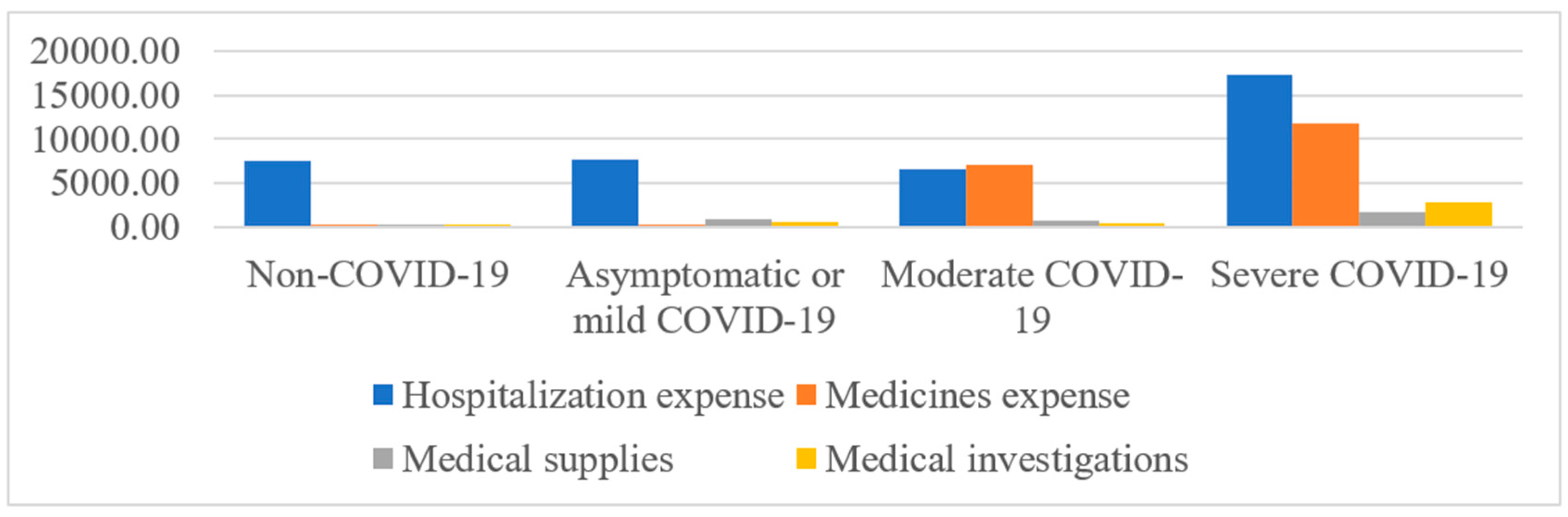

In a more schematic form,

Figure 1 shows the distribution of cost components (hospitalization, medication, medical supplies, and medical investigations) in cases of pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 according to the severity of the disease, as well as those not infected.

According to our study costs increased significantly not only according to the presence of infection but also according to severity. There was a strong correlation between case severity and direct and indirect costs of hospitalization (p<0.001).The costs of a severe case of COVID-19 can be about 3 times higher than a mild case and 70 times higher than a non-COVID-19 case.

4. Discussions

The objective of this study was to outline the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on healthcare system resources through the perspective of a maternity unit exclusively for infected patients.

Following this study we were able to demonstrate a significant increase in the costs of hospitalization, medication and investigations correlated with the increase in the severity of the disease, but also compared to the cases of uninfected pregnant women.

The increase in costs was due to several factors such as an increase in the percentage of births by caesarean section (81.36% vs 63.32%), premature births (10% vs 4.62%), the number of days spent in ICU (2.18 vs 0.68), multiple medications (antibiotics, corticosteroids, antivirals) and routine investigations in moderate and severe cases of illness (chest X-rays, chest CT, multiple sets of blood tests). As we know, both caesarean operations and premature births, as independent factors, involve high costs by increasing the number of days of hospitalization, including in ICU, and by the use of various medications.

As in other studies, we also found an increased rate of cesarean section births and premature births during the pandemic [

13,

14,

15,

16]. In the pre-COVID-19 period, the minimum length of stay for cesarean delivery was 3 days, with a total cost of approximately 2000 RON/hospitalization. Our findings suggest that pregnant women positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection, on average, stayed in the hospital for about 5 days, at an approximate cost of 9000 RON/ hospitalization, thus more than 4 times higher. The main determinant of this increase in cost is related to the PPE needed to care for patients infected with COVID-19. Medical oxygen is the leading cost factor when pregnant women present with severe COVID-19 and require a long hospital stay.

In a 2020 review, the authors reported that the median cost of a vaginal delivery was

$40 in a public hospital, while the cost of a cesarean delivery was

$178 in public hospitals in low income and middle income countries before SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and in cases of pregnant women infected, the costs increased 6 times for vaginal birth and 16 times for caesarean birth [

17]. Our findings suggest that the state pays for pregnant women with COVID-19 twice as much and up to 70 times as much if they have COVID-19, the severe form. This finding is of considerable concern, especially given that we are talking about a public hospital, which is seen as a foundation stone for achieving universal health coverage [

18].

It has been ascertained that tertiary hospitals are significantly more expensive for care compared to both secondary and primary health units, mainly because of the specialist skills that are concentrated there [

19]. The main determinant in this increase in the cost of use for deliveries relates to the PPE required to care for patients infected with COVID-19. This surge in PPE as a major cost driver (up to 50%) is worrying. Previously, while cost factors varied by country, a majority reported that medicines and supplies, transport, and accommodation were the main cost factors women had to address to access care [

18]. Nevertheless, there is also the issue of medical oxygen emerging as the main cost factor (up to 48%) in severe cases requiring a long hospital stay. This is happening despite it being the second most important component of the COVID-19 care bundle [

19].

Before COVID-19, health professionals had some form of PPE to protect them when providing services, but not enough for adequate care. During the COVID-19 pandemic, demand exceeded supply worldwide [

20]. More than half of healthcare workers reported that they did not have access to enough PPE to keep themselves safe during consultations [

21]. At the beginning of the pandemic, the cost of PPE was lower, but it skyrocketed, along with the price of surgical masks ( 6 times), N95 respirators ( 3 times), and surgical gowns (2 times) [

20].

Given the costs involved in caring for pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2, it can be established that prevention of infection is better than cure, which is where vaccination of pregnant women against SARS-CoV-2 comes in [

22]. This strategy would have substantial cost-saving implications for pregnant women. According to our study, only 16.8% of pregnant women were vaccinated at the time of admission. Unfortunately, the vaccination campaign has not been very successful since its launch in October 2021, and all pregnant women with severe COVID-19 were unvaccinated.

There are multiple studies on the impact of the pandemic on healthcare costs in which increased use of healthcare resources and a significant increase in costs were found. It is difficult to compare expenditures because of differences in healthcare costs, population, or methodology. There are studies from Switzerland [

23], the USA [

24], Turkey [

25,

26], China [

27], and Saudi Arabia [

28] where the burden on the healthcare system in terms of resource use and costs has been shown to be substantial. In a study of 70 patients in China during the early period of the pandemic, the cost per patient was identified as USD 6827, of which the largest proportion was medication, i.e. 45.1% [

19]. A study by ALTEMS (Advanced School of Health Economics and Management at the Catholic University of Sacro Cuore in Rome) shows that each patient treated in Italian hospitals costs the state almost €8,500, while the cost for each patient who deceased from Covid in a hospital was almost €9,800 [

29]. To date, a significant impact of COVID-19 on health expenditure and on all state economies has been reported [

30,

31].

Researchers have shown that health spending is a factor that can be used to drive economic growth [

32]. The pandemic has had devastating effects in several areas, not only on health [

33]. These devastating effects have far outweighed the health costs. The International Monetary Fund estimates the cost of COVID-19 at three trillion euros for the European Union [

34].

This study was an attempt to estimate the COVID-19 burden in COVID-19-only centers, based on data from a maternity, tertiary center. Among the pandemic prevention and control strategies, the measures implemented for the safety of healthcare workers were quite extensive. Personal protective gowns, gloves, and masks such as N95, FFP2, and FFP3, as well as face shields and goggles had to be used during contact with patients. Efforts such as the conversion of existing areas or the creation of special wards isolated from other parts of the hospital, the division into "red" zones for infected patients, and "green" zones for medical staff, also generated additional costs. In addition, performing COVID-19 diagnostic tests on every patient or newborn, repeated at certain times, especially in the first wave, caused additional costs of care for other diseases.

In the first part of the COVID-19 pandemic, doctors were inclined to hospitalize patients for close follow-up for any severity. However, this habit changed over time, and only patients with a more severe form or lower oxygen saturation were hospitalized. In September 2020, the WHO recommended outpatient monitoring of mild-form patients [

35].

The economic impact of the pandemic on hospitals that had to restrict access to health services for patients who were not COVID-positive but needed medical care appears to be another issue that requires further investigation. COVID-19 has brought exacerbated expenditure in the Romanian health system: 594 million euros went directly to the budget of the National Health Insurance House for the settlement of anti-COVID treatments to hospitals; 214 million euros represented the purchase of equipment and doctors' bonuses.

This money was budgeted for the purchase of protective equipment, payment of bonuses to medical staff, tests, and expansion of health services accessible to vulnerable groups, but so far there are no reported settlements.

5. Conclusion

Through the current study, we found a significant increase in all costs caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection in a maternity, tertiary center. For patients with severe forms of the disease, the costs could even be 70 times higher than a case without COVID complications. The costs were increased by the length of hospitalization, medication, and medical investigations, but also by the use of sanitary materials especially dedicated to the protection of medical professionals. Considering those results and barring the access to obstetrical care for non covid patients it is reasonable to conclude that the strategy was not efficient and very expensive increasing the burden of the expenses without evident benefit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-I.B. and L.P.; methodology, A.B.; software, M.P.; validation, L.P., and B.H.H.; formal analysis, G.-P.G.; investigation, T.-I.B.; resources, M.P.; data curation, R.-M.S; writing—original draft preparation, T.-I.B.; writing—review and editing, R.-M.S;.; visualization, B.H.H.; supervision, L.P.; project administration, L.P.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of “Sf. Ioan” Emergency Hospital, Bucharest, Romania (no 30386/16.12.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- COVID-19 dashboard by the center for systems science and engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Available from: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6. Accessed March 24, 2022.

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic – Emergency Use Listing Procedure (EUL) open for in vitro diagnostics: World Health Organisation; 2020 [cited 2020 cited4/17/2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/diagnostics_laboratory/EUL/en/.

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). situation report; 2020. p. 72.

- Gupta AG, Moyer CA, Stern DT. The economic impact of quarantine: SARS in Toronto as a case study. J Infect. 2005;50(5):386–93. [CrossRef]

- Warren DK, Shukla SJ, Olsen MA, Kollef MH, Hollenbeak CS, Cox MJ, et al. Outcome and attributable cost of ventilator-associated pneumonia among intensive care unit patients in a suburban medical center. Crit Care Med. [CrossRef]

- Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Matté A, Barr A, et al. Two-year outcomes, health care use, and costs of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(5):538–44. [CrossRef]

- Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Matté A, Barr A, et al. Two-year outcomes, health care use, and costs of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(5):538–44. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. State of Health in the EU Romania. Country Health Profile. 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/state/docs/chp_romania_english.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Vlădescu, C.; Scîntee, S.G.; Olsavszky, V.; Hernaández-Quevedo, C.; Sagan, A. Romania: Health system review. Health Syst. Transit. 2016, 18, 1–170.

- Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ, Terry SJ. COVID-Induced Economic Uncertainty. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. 2020;No. 26983.

- Berardi, C.; Antonini, M.; Genie, M.G.; Cotugno, G.; Lanteri, A.; Melia, A.; Paolucci, F. The COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: Policy and technology impact on health and non-health outcomes. Health Policy Technol. 2020, 9, 454–487. [CrossRef]

- Moy, N.; Antonini, M.; Kyhlstedt, M.; Paolucci, F. Categorising Policy & Technology Interventions for a Pandemic: A Comparative and Conceptual Frame-Work. Work. Pap. 2020. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=36229662020 (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Smith V, Seo D, Warty R, et al. 2020. Maternal and neonatal outcomes associated with COVID-19 infection: A systematic review Ryckman KK (ed). PLOS ONE 15: e0234187. [CrossRef]

- Bellos, I., Pandita, A., & Panza, R. (2020). Maternal and perinatal outcomes in pregnant women infected by SARS-CoV-2: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhou Z, Zhang J, et al. A Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in a Pregnant Woman With Preterm Delivery, Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020; 71:844–846. [CrossRef]

- Mullins E, Evans D, Viner RM, O'Brien P, Morris E. Coronavirus in pregnancy and delivery: rapid review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(5):586-592. [CrossRef]

- Banke-Thomas A, Ayomoh FI, Abejirinde I-OO, Banke-Thomas O, Eboreime EA, Ameh CA. 2020. Cost of Utilising Maternal Health Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review.International Journal of Health Policy and Management 0: 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Sachs JD. 2012. Achieving universal health coverage in low-income settings. Lancet (London, England) 380: 944–7. [CrossRef]

- Stein F, Perry M, Banda G, Woolhouse M, Mutapi F. 2020. Oxygen provision to fight COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Global Health 5: 2786. [CrossRef]

- Burki T. 2020. Global shortage of personal protective equipment. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 20: 785–6. [CrossRef]

- Semaan A, Audet C, Huysmans E, et al. 2020. Voices from the frontline: findings from a thematic analysis of a rapid online global survey of maternal and newborn health professionals facing the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Global Health 5: e002967. [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente D, Driha OM, Bekun FV, Sinha A, Adedoyin FF. Consequences of COVID-19 on the social isolation of the Chinese economy: accounting for the role of reduction in carbon emissions. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health. 2020;13(12):1439–51. [CrossRef]

- Vernaz N, Agoritsas T, Calmy A, et al. Early experimental COVID-19 therapies: associations with length of hospital stay, mortality and related costs. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2020;https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20446.

- Bartsch SM, Ferguson MC, McKinnell JA, et al. The potential health care costs and resource use associated with COVID-19 in the United States. Health Aff. 2020;39(6):927–35. [CrossRef]

- Gedik H. The cost analysis of inpatients with COVID-19. Acta Medica Mediterr. 2020;36(6):4.

- Karahan EB, Öztopçu S, Kurnaz M, Ökçün S, Caliskan Z, Oğuzhan G, et al. PIN56 cost of COVID-19 patients treatment in Turkey. Value Health. 2020;23:S554. [CrossRef]

- Li X-Z, Jin F, Zhang J-G, et al. Treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 in Shandong, China: a cost and affordability analysis. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2020;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Khan A, Alruthia Y, Balkhi B, et al. Survival and estimation of direct medical costs of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7458. [CrossRef]

- Di Bidino R, Cicchetti A. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on Provided Healthcare. Evidence From the Emergency Phase in Italy. Front Public Health. 2020 Nov 23;8:583583. [CrossRef]

- Autrán-Gómez AM, Favorito LA. The social, economic and sanitary impact of COVID-19 pandemic. Int Braz J Urol. 2020;46(suppl.1):3–5. [CrossRef]

- El-Khatib Z, Otu A, Neogi U, Yaya S. The Association between Out-of-Pocket Expenditure and COVID-19 Mortality Globally. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health. 2020;https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.200725.001.

- Balsalobre-Lorente D, Driha OM, Bekun FV, Sinha A, Adedoyin FF. Consequences of COVID-19 on the social isolation of the Chinese economy: accounting for the role of reduction in carbon emissions. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health. 2020;13(12):1439–51. [CrossRef]

- Alola AA, Bekun FV. Pandemic outbreaks (COVID-19) and sectoral carbon emissions in the United States: a spillover effect evidence from Diebold and Yilmaz index. Energy & Environment. 2021;32(5):945–55. [CrossRef]

- Trebski K, Costa C, Smidova M, Nemcikova M. The costs of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Italian Perspective Acta Missiol. 2020;14(2):127–37.

- WHO. Coronavirus sypmtoms 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/healthtopics/coronavirus#tab=tab_3.].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).