1. Introduction

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic era

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic era, most students in higher education institutions (HEIs) received their educations from their lecturers in face-to-face auditoriums (Cullinan et al., 2021). Alongside this era, there were broadband connectivity challenges. Additionally, in prior Covid-19 pandemic era, there existed correspondence classes, distance learning and electronic learning as forms of non-formal education, where all were based on digitalization (Mishra et al., 2020). In support of Mishra statement, Cullinan et al. stated that online learning existed within the HEIs sector for a recorded number of years (Cullinan et al., 2021; Mishra et al.,2020),

Covid-19 pandemic era

The Covid-19 pandemic era emerged in Wuhan City of China in December 2019 and was epidemic (Mishra et al., 2020). It became pandemic where the highly infectious diseases of Covid-19 severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus (SARS-CoV-2) spread had a negative global impact (Mishra et al., 2020). The negative global impact in March 2020 compelled and warranted governments to take measures to restrict corpus population movement for the Covid-19 spread reduction and the R-number below 1 decrease, where R is the average sum of people that one infected person will transmit the virus to another (Al-Habaibeh, 2021).

According to the April 2020 World Bank report, 175 countries closed their higher education institutions with a student population of over 220 million due to the Covid-19-related lockdowns (World Bank, 2020). This global health crisis of Covid-19 pandemic era led most educational institutions including HEIs to organize for online learning and migrated to technology-based online pedagogy to alleviate the face-to-face interaction danger (Agarwal & Kaushik, 2020; Dhawan, 2020; Zoljargal, 2021).

Online learning

Online learning (digital education system) connects students and lecturers who are separated from each other by physical distance, as well as transactional distance (Zilka, Finkelstein, Cohen, & Rahimi, 2021). An online environment enables students to upsurge the learning process and usually provides (i) groomied interpersonal communication skills, (ii) inquiry-based learning extensive section, (iii) supports collaboration and spatial division, (iv) the integration of higher-order thinking integration tasks, and (v) visual, auditory, texts, verbal, and visual inclusion (Zilka et al,, 2021; Zilka, Rahimi, & Cohen, 2019; Zilka, Cohen, & Rahimi, 2018). Online learning is either a synchronous (where the teaching takes place live online) or asynchronous process and creates better flexibility in where and when students learn (Lee, 2017).

Technology integrated educational systems and broadband connectivity challenges

The technology integrated educational systems brought changes in pedagogy styles (Faloye & Ajayi 2021). Presently, educational institutions are embracing technologies, such as computers, and the Internet to enhance pedagogy activities (Faloye & Ajayi 2021). However, in the HEIs, this unexpected and emergency shift resulted in problems for some undergraduate students without access to technology and low Internet connectivity of low bandwidth (Cullinan et al., 2021). The broadband connectivity challenges experienced prior Covid-19 pandemic era became a sharp focus because of no face-to-face-education. In other words, with the unexpected change to the widespread closure of campus facilities and emergency online delivery education, resulting in online connectivism.

Connectivism and digital divide

Connectivism is regarded as a fairly new pedagogy for the future, where students are regarded as, “nodes” in a network. A node is any object or individual, which connects to another object or individual, such as book person website, etc. However, in connectivism theory, it supersedes personal knowledge construction with external learning networks. Based on connectivism theory, students learn when they make students’ connections, or “links”, between various “nodes” of information, and they continuously make and maintain connections to form knowledge. However, there was a connectivism challenge referred to as, “digital divide”, indicating that the technology usage has not served the intended purpose due to the digital divide.

Ercikan, Asil, and Grover defined digital divide as a social inequality between individuals regarding access to information and communication technology (ICT), frequency of use of technology, and the ability to use ICT for different purposes” (Ercikan, Asil, & Grover, 2018), The three digital divide levels in schools are (i) ICT infrastructure, (ii) lecturers and students’ ICT usage in the lecture rooms/online classes; and (iii) students’ empowerments. Factors obstructing technologies usage are lecturers’ approaches towards technologies and their unwillingness to new ICT (Chisango & Marongwe, 2018).

Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), 5G usage, and digital divide closure

There is a right imperative to ensure everyone belongs to the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), through timely reserves and fixed positioning. At an accelerated speed in 2020, the world involved in digital transformation, re-pictured technology’s critical role in societal ethos. Simultaneously, the Covid-19 pandemic lit up an enduring issue, where numerous people remain without internet access as their universal human right.

Globally and according to Davos Agenda 2021, numerous rural, low-income societies, and large urban areas lack cheap and consistent technology benefits, such as Internet access. These societies will further be deprived of technology accessibility benefits as more devices and systems compliant to internet connectivity emerge. Based on an International Telecommunication Union report, the Internet penetration rate is 87% in the developed world, 47% in developing countries and 19% in the least developed countries.

A telecom conjointly cloud and information technology (IT) industries built an open with modern 5G infrastructure to help close the digital divide. The 5G creates value across local and national economies and contributes to economic stimuli. Additionally, the 5G innovation enables societies to transform industries, such as civic engagement, education, healthcare, job and skills training, and public services with a shared focus of the telecom, cloud and IT industries.

Presently, however, the telecom industry and technology status fell behind the evolutionary speed of the cloud and IT domains resulting in more expensive with more complex early 5G to achieve its impacts. With 5G, it is possible to possess a globally connected virtual classroom that allows every student to learn regardless of comprehension style, geography, or language. Presently, efforts to develop 5G networks were segmented where most regions were with no 5G positioning and other enterprises with limited 5G usage.

Segmentation deepens digital divide, hinders innovation, and limits much-required digital transformations of education, health, and transportation. In providing solution to the segmentation challenge, the technology system expansion that delivers the 5G innovations and outcomes is needed. Herein, existing major IT and cloud companies investments and faster pace are needed.

Despite a growing number of studies into technological adoption within teaching and learning at South African (SA) HEIs in the wake of Covid-19 lockdown restrictions (Mhlanga & Moloi, 2020), there is a need for studies that explicitly consider the technology and assessment utilisation of students in this emerging context. Prior studies identified inadequate digital infrastructure, primary digital divide affordability and skills challenges in emerging economies, lecturers’ perspectives of technology and assessment, with a critical stress on the lecturers’ voice in digital technology usage (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021; Dwivedi et al., 2020). Additional studies examined matters critical to the student’s, especially the Generation Z experience of the digital divide and to assess student-centered perspectives to identify specific challenges, readiness and circumstances arising from the digital divide in emergency times (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021).

Digital literacy

However, the digital divide and educational inequalities remain noteworthy societal problems in South Africa’s emerging context, affecting disadvantaged students from low income households (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). Accordingly, universities are challenged to meet the students’ needs with (i) varying technological readiness levels, (ii) information deficiencies, and (iii) digital literacy shown to be a hindrance to student success (Takavarasha, Cilliers & Chinyamurindi, 2018). Digital literacy refers to the ability to comprehend (read with meaning and understand) and use information in numerous formats from extensive sources when it is presented via computers. Digital literacy or digital competence (that is. information literacy, ICT skills, and technological literacy) is part of the lifelong learning competencies (Martínez-Bravo, Sadaba-Chalezquer & Serrano-Puche, 2020). In information literacy, emergent digital divide became noticeable with students who struggle to use digital tools (Reedy & Parker, 2018). Digital tools are the devices, gadgets, various software, and hardware artefacts, which influence one’s capability to learn and how to use digital platforms for engaging in educational activities in an accountable and safe style (Takavarasha et al., 2018).

Marginalized universities, such as University of Fort Hare are aware of digital literacy for their students. Herein, first year undergraduate students are given free trainings to equip them with computer skills for their registered courses and future requirements. The 2020 registered students did the training before lockdown but during the Covid-19 2021, the computer literacy training for first year undergraduate students was not feasible. Between 2020 and 2022, the South African studies on Covid-19 impact in the South African HEI contexts relevant to this study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

South African studies on Covid-19 impact in the South African HEI contexts.

Table 1.

South African studies on Covid-19 impact in the South African HEI contexts.

| Authors and study year |

Participants used in study |

Theoretical framework in support of the study |

Methodologies via data collection used in study |

| Ajani and Gamede (2021) |

General university students |

No learning framework was stated |

Qualitative research systematic review |

| Azionya and Nhedzi, (2021) |

General university students |

No learning framework was stated |

Netnography/Social media-Twitter |

| Badaru, Adu, Adu, and Duku, 2022) |

Lecturers |

SWOT analysis |

Empirical qualitative research approach |

| Mphahlele, Seeletso, and Muleya (2021) |

Mathematics second-year undergraduate students |

Digital equity |

Case study of Botswana, South African, and Zambia universities |

| Mpungose (2020) |

Postdoctoral students |

Connectivism learning framework |

Empirical qualitative research approach |

| Nnadozie, Anyanwu, Ngwenya, and Khanare, (2020). |

Final-year undergraduate students |

Activity theory |

Empirical qualitative research approach with electronic mail feedback as data collection instruments |

| Woldegiorgis, 2022 |

General university students |

Social justice of Fraser (1999) |

Empirical qualitative research approach and qualitative research systematic review |

Participants

Based on participants in the SA HEI context, studies on Covid-19 impacts conducted in South Africa considered (i) general university students as participants with no specific students’ levels as undergraduate or postgraduate (Ajani & Gamede, 2021; Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021; Woldegiorgis, 2022), (ii) lecturers as participants (Badaru, Adu, Adu,& Duku, 2022), (iii) Mathematics second year students (Mphahlele, Seeletso, and Muleya (2021), and (iv) postdoctoral students as participants (Mpungose, 2020), and (v) Nnadozie, Anyanwu, Ngwenya, and Khanare used final-year undergraduate students as participants (Nnadozie, Anyanwu, Ngwenya, & Khanare, 2020) . With the exceptions of Ajani and Gamede, Azionya and Nhedzi, and Woldegiorgis who used general university students as participants, other researchers used different participants in the SA HEIs (Ajani & Gamede, 2021; Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021; Woldegiorgis 2022).

Theoretical framework

Based on theoretical framework, there are studies on Covid-19 impacts conducted in the SA HEI context. Ajani and Gamede did not refer to any theoretical framework, but only mentioned social injustice in the title for their study (Ajani, & Gamede, 2021). Azionya and Nhedzi did not indicate any theoretical framework used for their research (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). Badaru et al. used SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis (Badaru, Adu, Adu, & Duku, 2022). Mphahlele, Seeletso, and Muleya used digital equity (Mphahlele et al., 2021), and Mpungose used connectivism learning framework (Mpungose, 2020). In addition, Nnadozie et al. used activity theory (Nnadozie et al., 2020) as the theoretical framework and Woldegiorgis used social justice of Fraser (1999) as the theoretical framework (Woldegiorgis, 2022).

Concisely, five researchers used different theoretical frameworks to justify their innovations, while the two groups (Ajani & Gamede, 2021; Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021) did not specify their theoretical frameworks.

Methodology via data collection

Based on methodology, there are studies on Covid-19 impacts conducted in the SA HEI context. From Ajani and Gamede study, it was observed that both researchers used narrative essay in form of qualitative research systematic review (Ajani, & Gamede, 2021). Azionya and Nhedzi used twitter (netnography) as data collection (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). Badaru et al. used empirical qualitative research approach (Badaru, Adu, Adu, & Duku, 2022) and Twitter is a social medium forum. Mphahlele et al. used case study of Botswana, South African, and Zambia universities (Mphahlele, Seeletso, and Muleya, 2021). Mpungose used empirical qualitative research approach (Mpungose, 2020). In addition, Nnadozie et al. used empirical qualitative research approach with electronic mail feedback as data collection instruments (Nnadozie et al., 2020) and Woldegiorgis used both empirical qualitative research approach and qualitative research systematic review from primary and secondary sources (Woldegiorgis, 2022). Concisely, all the researchers used different methodology via data collection to justify their innovations.

The purpose of this study is to explore via qualitative research systematic review of the Covid-19 pandemic impacts, online engagement, and digital divide on disadvantaged undergraduate students in South African universities. According to the authors’ knowledge, there are scarce studies in line with their innovative research in the HEI and global contexts in terms of the title, participants in alignment to the aim, theoretical framework, and methodology as systematic literature review (SLR).

Background studies

Prior Covid-19 pandemic era, researchers reported technological challenges, such as difficult access to high-speed broadband that negatively impacted on student and teacher engagement with online education, particularly with synchronous-based material (Silva, 2018; Skinner, 2019; Zydney et al., 2019).

Based on location and prior Covid-19 pandemic era, Raes et al stated that home students compared with on campus or near campus students experienced potential difference in access to digital learning resources during online schooling (Raes et al., 2019). On a similar digitalization note, Silva et al gave three factors (access gaps to right equipment, such as a laptop or personal computer (PC), right home environment to study, and the digital literacy skills for online learning) responsible for this digital divide (Silva et al., 2018). Based on broadband coverage, quality of broadband connectivity variations for home students as opposed to on campus, or near campus students is expected to be an important consideration in digital divide (Rasheed et al., 2020).

During Covid-19 era, a digital divide was exposed which referred to the digital technology access challenge, and broader inequalities pervading the educational systems (Dey 2021). The divide revealed the inequalities surrounding access to resources, but lit up an online learning interest levels gap in both student and lecturer (Dey, 2021). In 2020, during spring, Naffi and his colleagues used survey data from 78 centers for teaching and learning across 23 countries. Herein, they identified bandwidth challenges for students in some learning experiences, such as sharing files or synchronous classes (Naffi et al., 2020).

The European University Association (EUA) appraised that 90% of European HEIs in Europe engaged in online pedagogy during Covid-19 pandemic era (Gaebel, 2020). In addition to these studies, the UK student survey data specified that 7% of students reported their internet access insufficiency. The percentage rose to 12% for students from lower socioeconomic households (Montacute & Holt-White, 2020). Another student survey reported that 56% lacked access to right online course materials, where 9% were cruelly impacted (Office for Students, 2020). In Ireland, 21% of third-year students indicated that reliable Wi-Fi access was a fundamental need to increase their learning experience for progress (Union of Students in Ireland, 2020).

The HEIs in United (US) and numerous other countries adopted the same approach similar to the European HEIs (Staff, 2020).

In South Africa, access to higher education is one of the critical concern areas principally for students from disadvantaged backgrounds (Woldegiorgis, 2022). Historically Black universities were underprivileged prior to South Africa’s transition to democracy in 1994 and still experience legacy issues hindering their deliveries. These underprivileged universities are referred to as “marginalised universities”, while their historically white and resourced counterparts are referred to as “privileged universities”. Marginalised universities majorly serve the Black African and previously disadvantaged university students (Mzangwa, 2019). For marginalised universities, technology access and device ownership are less widespread than at privileged institutions. In marginalised universities, students are less prepared to apply core computer skills and use the Internet, digital library/scholarly resources for academic pursuits (Takavarasha et al., 2018).

Prior Covid-19 pandemic in some South African universities, some lecturers used Blackboard Collaborate as learning management system (LMS) or online learning platforms (OLPs) in blended learning, while some used Moodle as LMS or OLPs.

The 2020 South African academic year witnessed the Covid-19 pandemic era where people’s lives and higher education delivery conventions were reformed. Herein, on 15 March 2020, the South African (SA) government declared a nationwide disaster state under Section 27(1) and Section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). For the SA ever-evolving digital economy, higher education online learning was the ICT fast-paced developmental results (Palvia, Aeron, Gupta, Mahapatra, Parida, Rosnera, & Sindhi, 2018).

The Covid-19 pandemic led to lockdown restrictions, where there was major shift from face to face learning in SA HEIs to online learning for safeguarding health against the students’ needs (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). During Covid-19 pandemic era in the SA universities, with no face to face pedagogy, the paradigm shift led to highest use of Blackboard Collaborate online learning platform (OLP) at University of Fort Hare (UFH) and Moodle OLP at Rhodes University (RU). University of Fort Hare and Rhodes University are two universities in the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. Both Blackboard Collaborate and Moodle OLPs are two of the several learning management systems (LMSs) used in SA HEIs and other global HELs. Other LMSs are Canvas (used in University of Witwatersrand in Eastern Cape), Clickup, Efundi, RUconnected and Vula. The two LMSs’ pros enable students to access, download lecture notes and learning resources freely (Gamage et al., 2022; Hamad, 2017). They were self-assured, use electronic test to get better learning outcomes than paper test, and own their exam results in confidence. Additionally, students could learn according to their learning pace, styles, and from their course mates’ posts.

However, some of these students are digital divide casualties, where there is a separation between students with unrestrained Internet access and the marginalized students (those with restrained Internet access). The marginalized students concerns about reduced access to Internet devices, data and socioeconomic status created major barriers to the educative intent of emergency online teaching. As a result, the Covid-19 pandemic era emphasized the pre-existing digital divides experienced by students (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021).

Additionally, during Covid-19 pandemic, most South Africa universities provided laptops and free Wi-Fi (wireless network) for technological devices link to interface with internet access within the university and residences (Rodrigues, Almeida, & Figueiredo, & Lopes, 2019). However, some disadvantaged undergraduate students at home experienced digital divide challenge that hampered them from accessing e-learning from home (Mpungose, 2020). Concisely, the two LMSs’ cons are erratic with low access to Internet, which prevented disadvantaged students to retain their learning resources when needed. The ongoing LMSs’ cons in academic engagement were challenges for both the lecturers and students due to access to technology and internet connectivity. The connectivity limitation challenge in contrary to South African National Qualification Framework (NQF) led to a gap between those without and with internet access.

The South African National Qualifications Framework (NQF) anticipated a fundamental shift to introducing lifelong learning, highlighting accessibility, and learning flexibility across the knowledge system, with assertion between academic and occupational knowledge (Parker and Walters, 2008). In 1995, lifelong learning was among the main validations for the South African NQF establishment. Lifelong learning entails providing flexible learning opportunities through individual’s lifespan, which recognizes diverse knowledge systems amid and through regions, practice sites, or institutions. It sustains the learning culture basics to enable individuals to learn.

Flexible learning concept arose as an alternative for online learning challenge in HEIs. Flexible learning emphases on providing students with choices in the learning modes, pace, and setting, pace, place to support right pedagogical practice (Gordon, 2014). In addition, flexible pedagogy is more important than using technologies, such as the Internet, LMSs, mobile technologies, and personal computer (PC), because these technologies do give immeasurable opportunities for flexibility (Jones, & Walters, 2015). Flexible learning is also referred to resilient pedagogy (Clum, Ebersole, Wicks, & Shea, 2022), crisis resilient pedagogy (CRP) (Chow, Lam, & King, 2020), or pivot pedagogy (Schwarzman, 2020). Resilient pedagogy is defined as the ability to facilitate learning experiences designed to adapt to unstable conditions and interruptions, which considers a dynamic learning context requiring new interaction systems between lecturers, students, teaching content, and teaching tools (Quintana & DeVaney, 2020). Chow et al. stated that, the instructional approach was CRP (Chow et al. (2020). Pivot pedagogy is the preparing action for a module to be delivered in a various modalities in unanticipated situations (Schwarzman, 2020).

However, lifelong learning involves flexible provision of learning opportunities across the individuals’ lifespan that recognizes different knowledge forms across and between sectors, practice sites, or institutions. It confirms the learning culture importance, which enables all people to learn. However, in both nationally and internationally, the lifelong learning concept with its significance to sustainable socio-economic development is still of limited understanding.

The South African National Qualifications Framework (NQF) was understood as a key lever towards embedding lifelong learning, emphasizing flexibility, portability and learning accessibility across the system, with articulation between academic and knowledge vocational forms (Parker and Walters, 2008).

In South Africa, few HEIs have consistently explored lifelong learning. As a result, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCS) are supported as the answer to flexibility in education to enable thousands of learners to access learning in novel ways, but there might be concerns about pedagogy, learners’ hidden costs, and low course completion rates (Gordon, 2014).

Problem statement

Digital divide entails the gap between students without and with access to computers, where the Internet is a huge challenge preventing the e-learning feasibility in a South African setting (Van Deursen, & van Dijk, 2019). The consequences of universities not engaging with technology-enhanced learning are that the gap between those who are not exploring these modes and those who are will continue to expand, students become gradually dissatisfied with higher education and disengaged from learning, non-visible skills assessments are negotiated, and lost opportunities to prepare suitable graduates traits (Bond, Buntins, Bedenlier, Zawacki-Richter, & Kerres, 2020).

What are the factors responsible for digital divide challenge among undergraduate students’ engagements during Covid-19 pandemic online pedagogy?

What impact does digital divide challenge have on disadvantaged undergraduate students?

How was digital divide managed with connectivism for a sustainable post Covid-19 era?

Exploring the Covid-19 pandemic impacts, online engagement, and digital divide on disadvantaged undergraduate students in South African universities.

Factors responsible for digital divide challenge during among undergraduate students’ engagements during Covid-19 pandemic online pedagogy.

Disadvantaged undergraduate students and how they coped with the digital divide challenge

Digital divide challenge management with connectivism for a sustainable post Covid-19 era

Based on the research questions, the rationale of this study is to explore via qualitative research systematic literature review of the Covid-19 pandemic impacts, online engagement, and digital divide on undergraduate students in South African universities.

Based on time constraints, the study delimitation is exclusion of postgraduate and inclusion of undergraduate students.

This study will help to prepare students for the post-pandemic world, which will probable follow a blended approach between in-person and virtual learning and work environments (Dey, 2021). This study’s significance considers connectivism as the most active method for the administrators and educators (agents of change) to start the school year. This study’s significance considers community building at the foremost in the 4IR. For undergraduate students, it is crucial that the lecturers effectively communicate with students to achieve maximum engagement to develop the students’ potentials for develop twenty-first century skills. Additional research significance is the academic integrity development among undergraduate students during remote research supervision to fulfil twenty-first century competency and requirement for quality education as the fourth goal of 2030 South African development Goals (SDG).

2. Theoretical framework

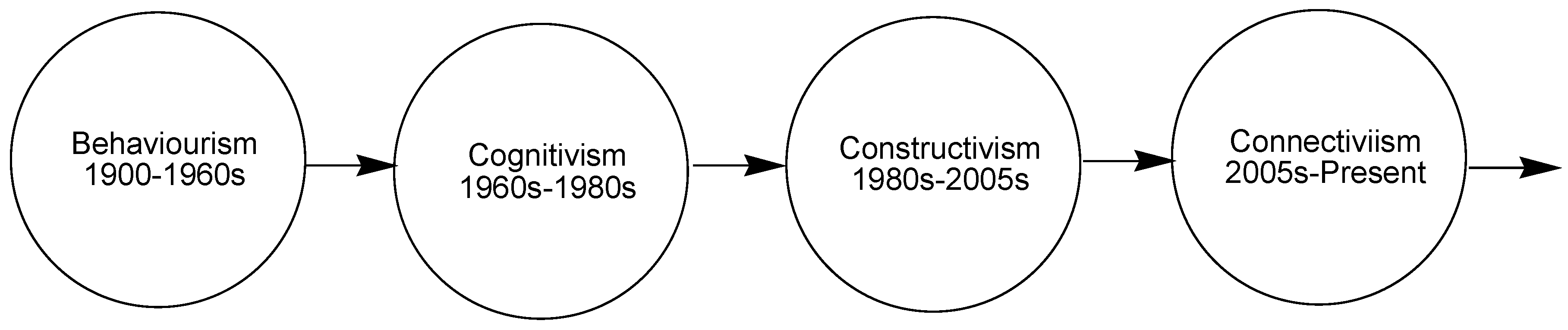

Prior Covid-19 era and over two decades ago, technology simplified communication, learning, and living styles. As a result, learning theories are changing due to technology advent and advancement (Shrivastava, 2018). Technology has changed how students learn within and outside the lecture halls, where smartphones and laptops are information hubs for nowadays students. According to Chandrappa's study, behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism are the three general learning theories usually used to create teaching environments. These three learning theories developed in a non-impacted learning technology era as shown in Figure 1 and do not address the learning value, knowledge outside a person, organizational knowledge and transference challenges. However, connectivism addresses numerous organizations challenges in knowledge management actions, because knowledge within a database needs to be connected with the right people in the right environment to be considered as learning.

Figure 1.

Evolution of learning theories.

Figure 1.

Evolution of learning theories.

Connectivism is a new learning theory for the digital age introduced by George Siemens and Stephen Downes in 2004 (Chandrappa, 2018). In 2005, George Siemens coined connectivism as a learning theory. It is a collaborative learning environment, which links people and things from different geographical locations and from diverse walks of life. Siemens is both a technology and education writer who got credit for co-creating the Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) with Stephen Downes. Siemen perceived face-to-face pedagogies as components in connectivism, but believed that there were connectivism variations. The theory depends on collaboration and what Siemens referred to as, “navigating digital networks’- or the internet usage to discover information for personal learning. Learning as an actionable knowledge, is a process that occurs within vague environments of shifting core elements—not completely under the control of the individual. Learning outside an individual but within a database or an organization is aimed at connecting specific information sets for lifelong learning.

Individual is the connectivism commencing point, where personal knowledge comprised a network, which feeds into institutions, recycles into the network, and continue to deliver learning to individual. The individual to network to organization is knowledge development cycle which enables students to remain conversant in their specializations through their formed connections. Social network analysis is an added element to understanding learning models in a digital era. In social networks, hubs are well-connected people who foster and maintain knowledge flow. Their interdependence results in effective knowledge flow for personal understanding of institutional activities.

Connectivism builds on proven theories to propose that technology is changing what, how, and where we learn. Siemens and Downes identified eight connectivism principles are: (i) learning and knowledge depends on opinions’ diversities, (ii) learning is a connecting process, (ii) learning could reside in non-human appliances, (iv) learning is more thoughtful than knowing, (v) nurturing and maintaining connections are needed for continuous learning, (vi) the ability to observe connections between specializations and thoughts is a fundamental skill, (vii) exact with up-to-date knowledge is the aim of connectivist learning, and (viii) decision-making is a learning process. What we know today might change tomorrow. While there’s a right answer now, it might be wrong tomorrow owing to the continuously varying information climate (Chandrappa, 2018). Similar to Mpungose, this study proposed connectivism learning framework as an alternative path for South African universities to control the digital divide (Mpungose, 2020).However, unlike Mpungose’s participants as postdoctoral students, this study’s participants were undergraduate students.

Connectivism is a new learning theory for a digital age because it has autonomy, connectedness, diversity, and openness as the four main learning principles (Corbett, & Spinello, 2020). It is one of the most eye-catching network learning theories developed for electronic learning environments (Shrivastava, 2018). The trying ground for this theory is massive open online courses (MOOCs), because it accepts technology as the learning process most important part and that our incessant connection allow learning choices opportunities. It is often addressed as the future pedagogy, because it unravels some age old problems. Area schools that experience extreme weather conditions or with far off-campus students will benefit from the remote education via the internet with a learning management system (LMS). This new ability also helps with unexpected scenarios, such as school closures and disrupted teaching.

Connectivism theory was largely accepted among technology writers and education technology humanitarians. Numerous traditional education experts thought the theory was to some extent, an adjusted version of constructivism theory. They contended that using online social interaction was extremely similar to habitual social interaction with deficiency of real human contact for it to be considered a new approach. However, the criticism discounts the additional factors present in online interactions, such as different language usage and text conversation rather than audio. These two factors make the experience overall different. True connectivism lessens human contact and increases the time extent students spend in front of computer monitors. For educational purposes, a hybrid version of connectivism is used to merge with broader constructivism to give students the best of both worlds.

3. Research methodology

In response to the three research questions via the research objectives, the research methodological approach was an eight (2014-2022) year duration systematic literature review using Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS) databases as advanced search strategies. Herein, 178 publications were collected in line with the research objectives. The included measures were publications in English language and between the years of 2014 and 2022 to obtain56 relevant publications in line with this study. The retrieved and relevant documents for suitability were validated and credited by seasoned lecturers in the Faculty of Education.

Advent of the Covid-19 pandemic era aggravated the digital divide challenges of students from disadvantaged backgrounds in HEIs (Woldegiorgis, 2022). Disadvantaged undergraduate students from lower-income families have reduced or no access to online classes because of digital inequalities and inadequate access to current technology (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). Factors, such as low literacy and income levels, geographical restrictions, lack of motivation to use technology, lack of physical access to technology, and digital illiteracy contribute to the digital divide. Some lecturers considered what could be the usefulness of sophisticated technology when some students are “disadvantaged” by it (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021).

The three digital divide categories are (i) inadequate technology, which is referred to as, “first-level digital divide”, (ii) inadequate relevant skills development needed for the Internet navigation, as well as information literacy skills to seek and evaluate information, which is referred to as, “second-level digital divide”, and (iii) the unequal technology usage benefits according to socioeconomic status, which is referred to as, “third-level digital divide” (Lombana-Bermudez, Cortesi, Fieseler, Gasser, Hasse, Newlands & Wu, 2020). Usage skills involves the occurrence, time duration, and types of activities achieved. In support of Lombana-Bermudez et al., Woldegiorgis stated that availability of digital facilities and Internet connectivity were important factors in enabling HEIs participation during the Covid-19 pandemic (Lombana-Bermudez et alal, 2020; Woldegiorgis, 2022). For the three digital divide categories, Azionya & Nhedzi suggested that the blended and hybrid models are better suited and most effective ways to ease student learning in online environments without the person-to-person classroom interactions, as well as being updated with emerging online teaching technologies that offer students the best online learning options and the optimal course management system to adopt (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). Blended classes, hybrid or mixed modality course design and classroom flipping use both face-to-face teaching and technology-facilitated networks to enhance interactive, engaging learning experiences and to improve students’ engagements, interaction, learning skills and learning results (Auster, 2016).

This study does not support Azionya and Nhedzi’s suggestion of using blended and hybrid models to control the three digital divide categories to safeguard lives during Covid-19, but supports Azionya and Nhedzi’s suggestion of using blended and hybrid models for post-Covid-19 era (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). However, the study further supports the three digital divide categories because firstly, students have computer or laptop to overcome first-level digital divide. Secondly, students must have acquired the relevant skills to overcome the second-level digital divide. Thirdly, students must have unrestrained access to Internet with wideband or hotspot to connect with others via the Internet for synchronous learning to overcome the third-level digital divide. Most importantly, the third-level digital divide aligns with the aim of this research, as well as with Lombana-Bermudez et al., and Woldegiorgis ideologies. For assignments within courses, course policies, and institutional policies, synchronous lectures were unsuccessful (Coman et al., 2020; Williamson, Eynon & Potter 2020; Hodges et al., 2020). As a result of digital divide challenges, Azionya and Nhedzi recommended that asynchronous activities might be more realistic than synchronous ones. (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021).

In South Africa, during Covid-19 in 2020, Azionya and Nhedzi, used netnograph to collect 678 tweets as data from Twitter between 29 June 2020 and 31 July 2020. The collected data including “digital divide concept,” “online learning” and “student voice.” were analysed with qualitative content analysis (Azionya & Nhedzi, 2021). Both researchers discussed that digital media in the digital divide covers socio-economic relationships between university students and management. Their study provided insights into the 4IR role, digital inequalities, environmental, institutional, situational and technological obstacles/inequalities the students faced during remote learning and assessment. Factors, such as day time, device type, digital competence, network coverage, and socio-economic status negatively affect synchronous attendance, participation, and lecture. As a result, their results revealed that online learning did not upsurge the university education accessibility during the pandemic era for disadvantaged students attending marginalised universities. Based on a university’s resources and student profile, the two researchers recommended more flexible and general pedagogy to ease digital and educational inequalities affecting disadvantaged students.

Concisely, factors responsible for digital divide are day time, device type, digital facilities, digital illiteracy, digital incompetence, geographical restrictions, income levels, Internet connectivity, lack of motivation to use technology, lack of physical access to technology, low literacy, network coverage, and socio-economic status.

Findings revealed that disadvantaged students are not satisfied with the current state of online learning and the key challenges confirmed the lack of digital resources (Moonasamy, 2022). Students that have not been exposed to any form of technology are often at a disadvantage with their learning because they often lack or do not possess computer skills (Faloye, 2019). Access to higher education has been one of the critical areas of concern in South Africa, particularly for students from disadvantaged (Woldegiorgis, 2022). The Covid-19 pandemic has not only worsen congestion problems with more people working via the Internet but also decreased Internet speeds globally (Lai, &Wildmar, 2021). The broadband access (and associated cost) availability for rural residents differs significantly at the geography, micro-level, province, or township, designation. However, schools and public places, such as libraries and institutions had education's roaming wireless access service for students for educational purposes. (Eduroam) (InCommon, 2020; Lai, &Wildmar, 2021). Countryside residents face further challenges due to long traveling distances required to get to public access points. In marginalized institutions, such as University of Fort Hare, numerous undergraduate students were provided laptops and Internet data monthly as a means of access to sufficient Internet connectivity (Lai, &Wildmar, 2021).

In Israel, with the Covid-19 outbreak crisis, the HEIs prepared for online learning. Herein, Zilka et al’s aim of study was a mixed-method study involving 639 students at Israel HEIs to examine the online learning’ implications of restricted access to digital content technology, digital environments, as well as information and communication technology (ICT) (Zilka et al., 2021). They assumed that restricted Internet access weakened students’ ongoing learning process with online pedagogy resulting in drop out of school desire, frustration, and stress. Their results showed that 13% participants had difficulties and restricted Internet access mainly during synchronous lectures. Additional results showed 10% fora usage. Zilka et al. recommended a more general fora usage in modules where students have restricted Internet access to create a helpful learning community (Zilka et al., 2021).

According to Zika et al, the digital divide challenge on disadvantaged undergraduate students’ impacts were, inadequate motivation, and low self-efficacy, which were responsible for gap creation or widening between students with full and those with restricted Internet access (Zilka et al., 2021).

Although Zika’s et al’s study was conducted in Israel, it provided the relevant response for this section. Concisely, impacts of digital divide challenge on disadvantaged undergraduate students are drop out of school desire, emotional distress, frustration, inadequate motivation, low self-efficacy stress, and long traveling distances required to get to public access points for Internet connection.

Educational institutions were basically built and based on an industrial rather than a digital era. In the total connectivity era of a passionate social media, universities discover education approaches for students to experience student-centered learning. As a result, educational institutions and educators (lecturers) are confronted with a huge challenge of change.

Students in this contemporary digital era participate in producing information (content producers) via social media learning (Shristava, 2018). Additionally, learning in the social media context is easy, free, and highly self-motivated, as well as an important part of the university experience (Shristava, 2018). A student who has multiple laptops in their home and has access to high-speed broadband might have better educational success and connectivity.

Connectivism is the integration of principles explored by chaos, complexity, network, and self-organization theories. Connectivism is driven by the understanding that decisions are based on rapidly altering foundations. New information is continually being acquired. Connectivity’s relationship with higher education is to develop twenty-first century' skills needed in the labor market and post Covid-19 era.

The future auditoriums will demonstrate more technology and more internet-skilled students for educational purposes, where connectivism must play a part in making that a reality. However, the reality might be farther from now and it requires patience, but more social media addition to classes and safe online spaces for students to explore topics, the reality is seen sooner. The ability to draw distinctions between important and unimportant information is vital. The ability to recognize when new information alters the landscape based on decisions made yesterday is also critical.

Connectivism relies profoundly on technology for digital learning opportunities, such as blogs, forums, online courses, social networks, and webinars. Incorporation off connectivism helps students to be flexible in their content and pace learning. It also enables personal learning to match with needs and strengths. Three ways to incorporate connectivism in lecture halls are gamifications, simulations, and social media.

Gamification reforms activities and assignments into a competitive game for a meaningful interactive learning experience. Lecturers track students' progress while students receive “points” for progressing through classes.

Simulations engage students in profound learning that empowers comprehension against surface learning requiring memorization. They also add inquisitiveness and fun to a classroom environment.

Government support

In the last ten years, the ICT division at a gradual pace, innovated, developed, and responded to unstable student needs. Government can support wider education access across all socioeconomic, race groups and geographic locations by confirming more equitable Internet access. Numerous South Africans accessed Internet outside the home. Herein, at work (15.0%), in internet cafés or schools and universities (9.3%) and with mobile devices (47.6%). An ICT policy think tank called, “Research ICT Africa”, discovered that, in the first three months in 2017, the “cheapest cost for a 1GB basket’’ in South Africa was US$7.49. This was a higher cost compared with lower costs in countries, such as Egypt (US$1.41), Kenya (US$4.92) and Nigeria (US$3.21). Both high data package costs and out-of-bundle rates indicate that mobile phone Internet access is not an economically viable option for low-income users, whose commonalities are the students.

Non-government supports

Supporting organizations, such as Silulo and various technology incubators, such as like Bandwidth Barn in Khayelitsha work in the space to make Internet accessible and digital space accessible for entrepreneurs, and numerous academics.

Concisely, digital divide challenge is manageable with connectivism (gamification, simulations, and social media) for a sustainable post Covid-19 era. Alongside, are the needed supports from government and non-government stakeholders.