1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was an extraordinary and unprecedented phenomenon because of its global impact. Combating the disease and developing ways to prevent it in a short time was one of the greatest challenges the world has faced in recent decades. Consequently, many of the measures taken by governments to contain the virus (e.g. compulsory social isolation) had a negative impact on the mental health of family groups. In this direction, previous studies [e.g. 1] had already pointed out that social isolation during pandemics or natural disasters can generate psychological disorders (e.g. post-traumatic stress) for both parents and children. Indeed, initial studies of people's reactions to the pandemic context revealed symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as symptoms of stress in the population [

2,

3]. In addition, the rapid spread of this virus provoked fear of the disease, as well as fear of the social and economic consequences of the pandemic [

4]. Particularly, in Argentina, a study conducted on the general population [

5] showed that anxiety and depressive symptoms increased over time and that intolerance to uncertainty was the main predictor of this variability. Especially, women and young people reported the highest number of psycho-pathological symptoms [

5].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, compulsory social isolation, social and work conditions, and changes in education negatively influenced parenting practices [e.g. 6; 7, 8]. Many parents faced work changes such as job loss, reduced pay, and remote work, and at the same time, had to assume greater child care responsibilities due to school closures [

9]. In this direction, several studies have reported that many parents felt overloaded and stressed by having to perform full-time parenting [6; 10]. In addition, parents or caregivers reported more mental health problems, greater irritability, lower positive family expressiveness, and higher alcohol consumption [8; 3; 11]. Likewise, the pandemic seems to have had a more negative impact on women with children [

12] and this impact was greater in mothers with more children [

13]. Mothers or caregivers suffered a greater load of unpaid work and the requirement of multifunctionality in relation to having to fulfill work, domestic, and child care roles, especially in Latin American cultures [

14] such as Argentina.

The literature in the area has pointed out that positive parenting can act as a protective factor for children against stressful events [

15] and as a facilitator of family resilience [

16]. Similarly, an Argentine study [

13] analyzed maternal perceptions of three dimensions of parenting [i.e., positive parenting, parental stress, and school support] and how these impacted perceived behavioral changes in children (e.g., in sleep, appetite, mood, obedience, fighting with siblings, participation and attitude in online classes, etc.). The results showed that indeed the type of parenting influenced the perceived behavior of the children during the pandemic. Mothers with low positive parenting perceived that their children yelled more and fought more with their siblings, were more anxious, were more disobedient, and showed more defiant and dependent behaviors. Mothers who presented greater parental stress perceived more negative changes in almost all the behaviors evaluated. They also perceived more internalizing behaviors in their children, such as greater sadness and regressive behaviors, compared to less stressed mothers. Mothers who reported having provided more school support also perceived that children adapted better to online classes, doing their homework, and enjoying their classes while being less frustrated by having to do school work at home [

13].

As for the children, a study that analyzed the impact of quarantine on Italian and Spanish children and adolescents [

17], showed that more than 80% of parents perceived negative changes in their mood and behavior during social isolation. The most frequent changes observed in children were: difficulty in concentrating, boredom, irritability, restlessness, nervous-ness, feelings of loneliness, discomfort, and fears. Particularly in Argentina, a study conducted during the pandemic by COVID- 19 [

18], in 4500 children and adolescents, found that almost 8 out of 10 (77%) showed more anger and 68% felt sad, 7 out of 10 children and adolescents (6 to 18 years of age) expressed feelings of discouragement and boredom, and 60% reported fear. Sixty percent felt a lack of outdoor recreational activities and sports, especially children and adolescents aged 6 to 14 years [

18].

In recent decades we have witnessed important changes in favor of gender equality that have resulted in greater involvement of fathers in the care and education of children. Nonetheless, parenting remains the most gender-typed role during adulthood [19; 20]. Mothers around the world show greater availability and commitment than fathers to parenting. Some studies conducted in families in Kenya, India, Guatemala, and Peru revealed that fathers rarely participate in the care of children under one year of age [

21]. In this direction, a recent study conducted in the United States [

22] indicated wide differences in the way mothers and fathers describe parenting styles. For example, about half of mothers (51%) say they tend to be overprotective compared to 38% of fathers. In turn, fathers (24%) are more likely to give children too much freedom than mothers (16%). Mothers are also more likely than fathers to say that parenting is exhausting (47% vs. 34%) and stressful (33% vs. 24%) all or most of the time [

22]. Consistent with previous surveys [

23], mothers report taking more responsibility for children's care than fathers, although fathers tend to say they share responsibilities almost equally. Most mothers (78%) report doing more than their spouse when it comes to managing schedules and monitoring children's school activities or homework (65% of those with school-age children), providing comfort or emotional support to their children (58%), and attending to their children's basic needs, such as feeding, hygiene, or diapering (57% among those with children younger than 5 years of age). Therefore, it can be stated that women already assumed a greater share of children's care before the pandemic. Even when both parents work, women have struggled more with work-family balance [

24].

Specifically, during the pandemic, women reported a greater load of children care and housework [

14] and more symptoms of anxiety and exhaustion, as well as more parenting-related worries and fears than men [

9]. However, a Canadian study suggests that fathers increased their involvement in household and children-care tasks during this period [

25].

In this context, the present study aimed to compare changes in children's behaviors and different parenting aspects as perceived by fathers and mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Based on the proposed objectives, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1: There are differences between fathers and mothers regarding the perception of behavioral changes in children during the pandemic.

Hypothesis 2: Mothers perceive higher levels of parental stress, involvement in children's school support, and positive parenting compared to fathers during the pandemic

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of study and Design

The study was quantitative, descriptive, and cross-sectional [

26].

2.2. Participants

The sample consisted of 120 parents (70 mothers, 58 % and 50 fathers, 42 %), of school-children, aged between 27 and 56 years (M=38.84; SD=5.03) from different Argentine provinces. A non-probabilistic availability sampling method was used [

27]. In addition, we asked about the work status of the fathers and mothers in the sample and found that 57% were employed, 31% were self-employed, and the remaining 12% were unemployed or homemakers -performed domestic and care tasks in their homes, without working outside the home. Finally, when evaluating the educational background of the parents, it was found that half of them had a university degree and 5% had postgraduate studies (complete or incomplete).

The inclusion criteria used were: (a) being over 18 years of age, and (b) being a parent of schoolchildren (between 5 and 12 years of age). Parents or caregivers of children with psychological, developmental, or learning disorders were not included in the study. This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

2.3. Instruments

Sociodemographic questionnaire. To collect information on the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, an ad hoc semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect data on gender, age, occupation, and educational level.

Questionnaire of perceived behavior of children. A semi-structured questionnaire was de-signed to assess changes in children's behavior as perceived by parents during the pandemic. In the questionnaire, parents were asked whether they observed variations in their children's behavior. The questionnaire mainly inquired about: (a) behaviors observed in the children concerning: sleep, eating habits, mood, and relationship with siblings and friends, and (b) behaviors observed concerning the children's school situation: online classes, relationship with classmates, and compliance with school assignments. Response options were: less, the same, or more than before the pandemic (e.g. Eating: less, the same, more).

Brief scale of perceived parenting during the pandemic [

28]. This instrument assesses three dimensions of perceived parenting in the pandemic context: a) positive parenting (e.g. I dedicate some time during the day to speak to my children), b) parenting stress (e.g. Time is not enough, as it used to be, to fulfill all my responsibilities), and c) parenting school support (e.g. I know which homework and assignments are given to my children in online education), based on 17 items with a 4-point Likert-type response scale (i.e., Never, Seldom, Very often and Always). The study of the instrument carried out in Argentina indicated adequate psychometric properties [28). The confirmatory study of factorial structure of 3 factors of the scale showed satisfactory fit indexes (χ2/gl =1.22; NFI = .93; NNFI = .99; CFI = .99; IFI = .99; GFI = .99) and an acceptable error (RMSEA = .02). The internal consistency was adequate for the three dimensions: positive parenting (⍵=.79), parenting stress (⍵=.77), and school support (⍵=.75) [

28].

2.4. Ethical procedures and data collection

All actions performed in the setting of this study followed the international ethical recommendations for research involving human subjects [

29]. In all cases, the purpose of the research was explained and parents gave informed consent before completing the form. Responses were anonymous and data confidentiality was strictly guarded. A reduced number of questions was included to avoid participant fatigue. The response time was less than 10 minutes.

Due to the confinement conditions of the pandemic, the invitation to participate in the study was made through social networks (Facebook and Instagram), email (Gmail, Outlook, etc.), and instant messaging services (WhatsApp and Telegram, etc.). Data collection was conducted during the social isolation phase, between September and December 2020. The information was collected through an online form (i.e., Google Forms), which included the instruments described in the previous section.

2.5. Procedures for data analysis

For the description of the sociodemographic variables and the study variables, descriptive statistics were calculated: measures of central tendency (mean, standard deviations), frequencies, and percentages.

A Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was performed to compare perceived parenting as a function of parental gender.

Given the qualitative nature of the variables, the Mann Whitney U test was used to analyze changes in behavior as a function of parental gender.

Data analysis was performed with SPSS version 25 software.

3. Results

3.1. Perception of changes in children's behavior between fathers and mothers

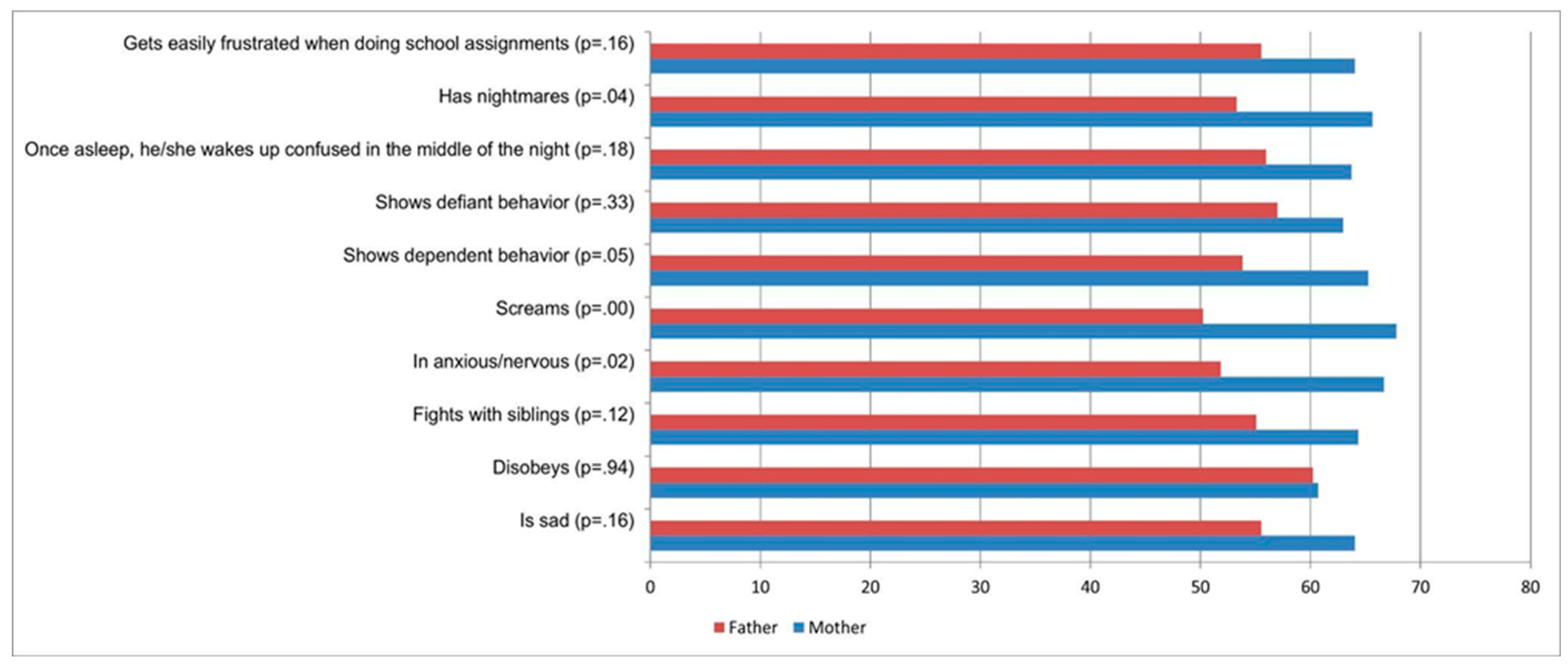

Table 1 and

Figure 1 show which children's behaviors were perceived as different between fathers and mothers during the pandemic. In the behaviors: is anxious, nervous, screams, and has nightmares, mothers perceived significantly more changes than fathers. For the remaining behaviors assessed, mothers also perceived more changes in their children than fathers, although these differences were not statistically significant (see

Table 1).

3.2. Comparison of perceived parenting between fathers and mothers

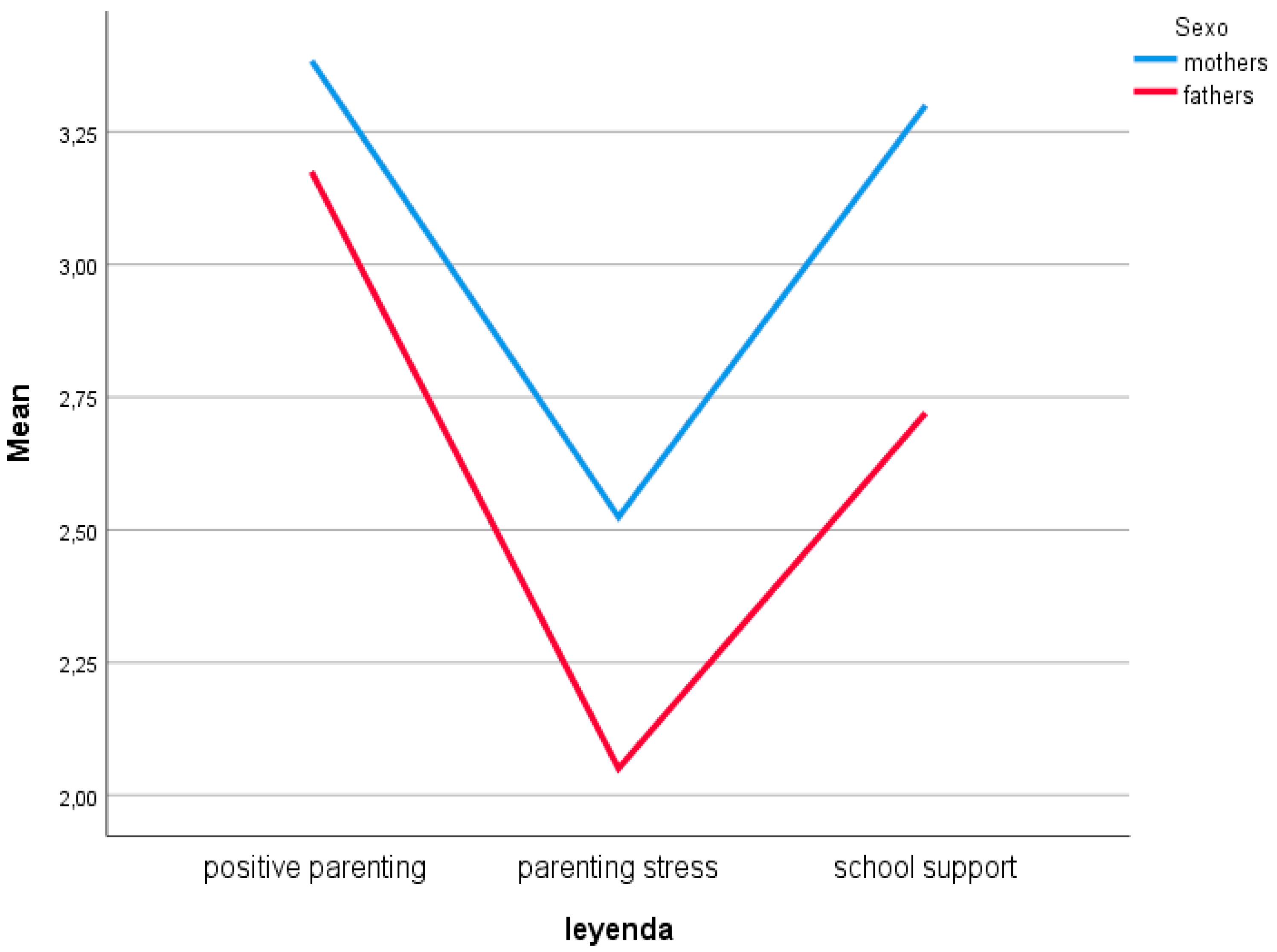

As shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 2, the dimensions of parenting were differentially perceived between fathers and mothers (Hotelling's F(3,116) p < .001; η² = .23) . Both positive parenting (F(1,118) = 7.16; p = .009; η² = .06), parental stress (F(1,118) = 19.09; p < .001; η² = .14) and in-volvement in school support (F(1,118) = 18.44; p < .001; η² = .14) presented higher scores for mothers than for fathers. (See

Table 2).

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought numerous challenges worldwide and had a strong impact on interpersonal relationships in general and particularly on family dynamics, routines, and interactions. Also, mothers and fathers often perceive and exercise their family roles, parenting styles and practices differently [

30]. Consequently, the present study aimed to compare changes in children's behaviors and parenting as perceived by fathers and mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina.

Regarding behavioral changes in children during the pandemic, differences were observed in the perception of fathers and mothers. Mothers, in particular, perceived more changes in all the behaviors evaluated. We hypothesize that since in our culture the mother is usually the most influential figure in parenting [

31], is more aware of the health, school performance, and interpersonal relationships of children, she has developed a greater perception of changes in children's behavior in adverse situations. At the same time, although mothers perceived changes to a greater extent in all the behaviors assessed, they did so especially in: shows dependent behavior, is anxious/nervous, screams, and has nightmares. In this sense, the child behaviors in which the greatest differences were observed in comparison to those perceived by the fathers were those referring to the children's emotional problems. Indeed, some studies suggest that mothers tend to perceive their children's emotional changes more easily and to be more sensitive to the signals their children give, compared to fathers [32; 33]. Regarding night-mares, one study indicated that mothers were more likely to report sleep problems in their children [

34]. We initially thought that differences in the perception of behavioral changes would be significant for all behaviors. However, it is possible that, during social isolation, parents may have taken a more active role in children's care compared to before the pandemic. Some studies have suggested that fathers increased their involvement in performing household and children care tasks during the pandemic [e.g. 25]. The compulsory social isolation, which lasted for several months in Argentina, led many parents to work remotely and thus spend more time at home and possibly interact more with their children. Thus, the results obtained partially support our first hypothesis.

On the other hand, the results showed significant differences in perceived parenting be-tween fathers and mothers. First, mothers perceived that they had more positive parenting practices than fathers during the pandemic. These results are consistent with pre-pandemic studies, so this aspect would seem to respond more to socio-cultural influences than to the pandemic context. For example, in a study conducted in the Netherlands, mothers reported significantly more positive parenting practices than fathers [

35]. In another pre-pandemic study in the Mexican population, mothers reported more authoritative parenting strategies than fathers, which was con-firmed by their partners [

36]. Also, a study conducted in Chinese families [

30], found differences in perceived parenting between fathers and mothers. Mothers re-ported having a more authoritative (i.e., warm and less controlling] parenting style than fathers. Finally, in other works [e.g. 37; 38], mothers scored on average higher than fathers on all positive parenting practices.

Regarding parental stress, it appeared more highlighted in mothers, possibly because they were mainly responsible for children's care and housework [

39], while many of them had to continue with their work. In this direction, a US study by [

40] showed that 79% of mothers reported being primarily responsible for housework and 66% for children's care during the pandemic, compared to 28% and 24% of fathers, respectively. Another study of Norwegian mothers [

41] indicated that their well-being decreased significantly as compared to before confinement. Furthermore, it was found that gender ideologies aggravated the negative impact of increased domestic responsibilities (i.e., children care and house-work) on the well-being (higher level of stress) of mothers. Mothers who more strongly endorsed the belief that mothers are instinctively and innately better caregivers than fathers, increasing their perceptions of increased household responsibilities, perceived lower well-being after confinement [

41].

Finally, mothers reported providing significantly more school support to their children than fathers. In this direction, some studies [

40] have pointed out that the division of time devoted to learning at home and monitoring homework completion during the pandemic was also influenced by gender. An 84% of mothers reported spending more time providing school sup-port than other family members, compared to 50% of fathers. Mothers were also more likely (57%) to say that they felt more pressure regarding their children's home learning compared to fathers (45%). Indeed, this study showed that of couples working from home, 72% of mothers perceived themselves to be primarily responsible for children's care compared to 33% of men. In this sense, mothers may have felt more responsible for their children's education even when both parents were available at home for this task. The results found for the three parenting aspects that indicated higher values for mothers support our second hypothesis.

5. Limitations and Strengths

The main strength of this study is that it allows us to know how a challenging context such as the COVID-19 pandemic affected some characteristics of parenting. In addition, it provides in-sight into the perceptions of fathers and mothers concerning parenting in Argentine culture.

However, the study conducted has some limitations that should be considered. First, the sample was purposive and non-probabilistic, and its size was small, making it unrepresentative of the Argentine population. For example, families from other social strata were not represented in these results, which is an important limitation considering that families of low socioeconomic status and with pre-existing problems in family relationships or mental health were more affected by multiple collateral effects of the pandemic [42; 42].

In addition, due to the conditions of social isolation, self-reports of the parents were used, and the children's perspective could not be considered in the evaluation. Future studies should also assess parenting and behavioral changes perceived by the children themselves. On the other hand, since this was a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to determine whether the changes in behavior and perceived parenting were maintained over time or were modified after the pandemic. There-fore, it would be advisable to conduct a post-pandemic evaluation to know the long-term effects of the pandemic on both caregivers and children. Also, in this paper, we have mainly analyzed the role of gender in parenting and the perception of children's behavior. However, there are many other contextual variables and individual differences that could be analyzed in future studies, such as: social status, gender of children, age of parents and children, occupation, and number of children, among others.

6. Implications

The results of the present study allow delineating intervention strategies in challenging con-texts (e.g., pandemics or natural disasters) in the future. At the same time, it highlights the need to design, implement and evaluate parenting intervention programs to mitigate the long-term negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on parenting. These approaches should consider the differences in parenting beliefs and practices that exist between fathers and mothers. Such proposals could promote greater involvement of men in parenting. In particular, they should provide psychoeducational training to parents or caregivers to contain children and prevent their psychological distress. Indeed, the protective role that caregivers can have in the face of fear and stress during a pandemic is important [

43], so timely intervention is necessary to ensure the mental health of all family members. Intervention programs should be based on sound theoretical approaches such as positive parenting, which has had promising results in adverse contexts and situations [e.g., 45; 31, 46; 47]. Likewise, strategies for the management of parental stress, especially in mothers, should be included in the program, considering the damage it can have on the family atmosphere, parenting, and psychological well-being of children [e.g, 48].

7. Conclusions

In short, during the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine, mothers perceived more behavioral changes than fathers. They also reported more positive parenting, more parental stress, and more school support than fathers. In this sense, we could say that a risk context such as social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted and exposed characteristics that are present in the usual conditions of families and that, therefore, are more determined by already existing cultural pat-terns, in this case referring to gender differences. These findings make visible the specific challenges faced by Argentine families, especially mothers, during the critical period of compulsory social isolation during the pandemic. In particular, they highlight the importance of addressing the gen-der differences that imposed additional loads on women in families.

Author Contributions

Data collection, C.B. and J.V.R Conceptualization, J.V.R.; Methodology, M.C. R and V. L. Data analysis, V.L. and C.B; Writing original draft, JVR., V.L. and M.C.R; Writing—review & editing, J.V.R. and V. L.; Supervision, J.V.R and M.C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET, Argentina), Universidad Adventista del Plata and Universidad Austral provided support to researchers through its infrastructure for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Adventista del Plata. The participants provided their written informed was obtained from all the participate in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the research assistants who collaborated in the data collection phase.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that there were no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Sprang, G.; Silman, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness 2013, 7(1), 105-110. [CrossRef]

- Canet-Juric, L.; Andrés, M. L.; Del Valle, M.; López-Morales, H.; Poó, F.; Galli, J. I., ...Urquijo, S. A longitudinal study on the emotional impact cause by the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine on general population. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2431. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; McIntyre, R. S., et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of the general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C. A.; Paluszek, M. M.; Fergus, T. A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G. J. COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and anxiety. 2020, 37(8), 706-714. [CrossRef]

- Del-Valle, M. V.; López-Morales, H.; Andrés, M. L.; Yerro-Avincetto, M.; Trudo, R. G.; Urquijo, S.; Canet-Juric, L. Intolerance of COVID-19-related uncertainty and depressive and anxiety symptoms during the pandemic: A longitudinal study in Argentina. Journal of anxiety disorders 2022, 86, 102531. [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. M.; Doom, J. R.; Lechuga-Peña, S.; Watamura, S. E.; Koppels, T. Stress and parent-ing during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child abuse & neglect 2020. 110(2). [CrossRef]

- Griffith, A. K. Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence 2020, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Roos, L. E.; Salisbury, M.; Penner-Goeke, L.; Cameron, E. E.; Protudjer, J. L. P.; Giuliano, R., et al. Supporting families to protect child health: Parenting quality and household needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2021, 16(5): e0251720. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M. L.; Rasmussen, H. F.; Fanning, K. A.; Braaten, S. M. Parenting during COVID-19: A study of parents' experiences across gender and income levels. Family Relations 2021, 70(5), 1327-1342 . [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Most Americans Say that Trump Was Too Slow in Initial Response to Coronavirus Threat. 2020. Available online at: https://www.people-press.org/2020/04/16/most-americans-saytrump-wastoo-slow-in-initial-response-to-coronavirus-threat/ (accessed march 1, 2023).

- Westrupp, E.; Bennett, C.; Berkowitz, T. S.; Youssef, G. J.; Toumbourou, J.; Tucker, R., et al. Child, parent, and family mental health and functioning in Australia during COVID-19: comparison to pre-pandemic data. Eur. Child Adolesc. 2021. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Encuesta de Percepción y Actitudes de la Población. Impacto de la Pandemia COVID-19 y las Medidas Adoptadas Por el Gobierno Sobre la Vida Cotidiana [Survey on Perception and Attitudes of Population. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Measures. 2020. Adopted by the Government on Daily Life], First Edn. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/argentina/sites/ unicef.org.argentina/files/2020-06/EncuestaCOVID_GENERAL.pdf (accessed March 15, 2023).

- Vargas Rubilar, J.; Richaud, M. C.; Lemos, V. N.; Balabanian, C. Parenting and Children’s Behavior During the COVID 19 Pandemic: Mother’s Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022. 13:801614. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Shrestha, A.; Stojanac, D.; Miller, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s mental health. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health. 2020, 23, 741–748. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M. R.; Turner, K. M. The importance of parenting in influencing the lives of children, in Handbook of Parenting and Child Development Across the Lifespan, eds M. R. Sanders and A. Morawska. Berlin: Springer. 2018, 3–26.

- Miller-Graff, L. E.; Scheid, C. R.; Guzmán, D. B.; Grein, K. Caregiver and family factors promoting child resilience in at-risk families living in Lima. Peru. Child Abuse Neglect 2020, 108:104639. [CrossRef]

- Orgilés, M.; Morales, A.; Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C.; Espada, J. P. Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11: 579038. [CrossRef]

- Cabana, J. L.; Pedra, C. R.; Ciruzzi, M. S.; Garategaray, M. G.; Cutri, A. M.; Lorenzo, C. Percepciones y sentimientos de niños argentinos frente a la cuarentena COVID-19. Arch. Argent Pediatr. 2021, 119, S107–S122.

- Koivunen, J. M.; Rothaupt, J. W.; Wolfgram, S. M. Gender dynamics and role adjustment dur-ing the transition to parenthood: Current perspectives. The Family Journal 2009, 17, 323–328.

- Nentwich, J. C. New fathers and mothers as gender troublemakers? Exploring discursive constructions of heterosexual parenthood and their subversive potential. Feminism & Psychology 2008, 18, 207–230. [CrossRef]

- Whiting, B. B., & Edwards, C. P. Children of different worlds: The formation of social behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 1988.

- Minkin, R.; Horowitz, J. Parenting in America Today, Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project. United States of America. 2023. Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/3412930/parenting-in-america-today/4212333/on 14 Apr 2023. CID: 20.500.12592/1svz8f.

- Pew Research Center. Parenting in America: Outlook, worries, aspirations are strongly linked to financial situation.2015. Available at www.pewresearch.org.

- Borelli, J. L.; Nelson-Coffey, S. K.; River, L. M.; Birken, S. A.; Moss-Racusin, C. Bringing work home: Gender and parenting correlates of work-family guilt among parents of toddlers. Journal of Child and Family Studies.2017, 26, 1734-1745. [CrossRef]

- Shafer, K.; Scheibling, C.; Milkie, M. A. The division of domestic labor before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: Stagnation versus shifts in fathers’ contributions. Canadian. Review of Sociology 2020 57(4), 523–549. [CrossRef]

- Bickman, L.; Rog, D. J. Handbook of applied social research methods. British Journal of Educational Studies.1998, 46, 351-351. [CrossRef]

- Otzen, T.; Manterola, C. Técnicas de Muestreo sobre una Población a Estudio. International journal of morphology. 2017, 35(1), 227-232.

- Vargas Rubilar, J.; Lemos, V.; Balabanian, C.; Richaud, M. C. Parentalidad en el contexto de pandemia: propuesta de una escala breve para su evaluación. Póster presentado en el XIV Congreso Argentino de Salud Mental.Buenos Aires, Argentina, 12 de octubre de 2021.

- American Psychological Association. Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 2017.

- Huang, C. Y.; Hsieh, Y. P.; Shen, A. C. T.; Wei, H. S.; Feng, J. Y.; Hwa, H. L.; Feng, J. Y. Relationships between parent-reported parenting, child-perceived parenting, and children’s mental health in Taiwanese children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16(6), 1049. [CrossRef]

- Richaud, M. C.; Vargas-Rubilar, J.; Lemos, V. Advances in the Study of Parenting in Argentina.In Parenting Across Cultures: Childrearing, Motherhood and Fatherhood in Non-Western Cultures. Springer Publishers of the Netherlands. 2022, 101-118.

- Katz-Wise, S. L.; Priess, H. A.; Hyde, J. S. Gender-role attitudes and behavior across the transition to parenthood. Developmental Psychology. 2010, 46(1), 18-28. [CrossRef]

- Leerkes, E. M.; Calkins, S. D.; Henrich, C. C.; Smolen, A.; Granic, I. Mothers' and fathers' sensitivity and children's regulatory behaviors in the first three years of life. Infant Behavior and Development. 2014, 37(4), 591-602. [CrossRef]

- Mindell, J. A.; Sadeh, A.; Kohyama, J.; How, T. H.; Goh, D. Y. T. Parental behaviors and sleep outcomes in infants and toddlers: A cross-cultural comparison. Sleep Medicine. 2010, 11(4), 393-399. [CrossRef]

- Okorn, A.; Verhoeven, M.; Van Baar, A. The Importance of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Positive Parenting for Toddlers’ and Preschoolers’ Social-Emotional Adjustment. Science and Practice, 2022, 22(2). [CrossRef]

- Gamble, W. C., Ramakumar, S., & Diaz, A. Maternal and paternal similarities and differences in parenting: An examination of Mexican-American parents of young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2007, 22(1), 72–88. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, D. C. R.; Lopez, N. L.; Olson, S. L.; Sameroff, A. J. Parental discipline and externalizing behavior problems in early childhood: The roles of moral regulation and child gender. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004, 32(2), 369–383. [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, S. T.; Leve, L. D.; Harold, G. T.; Neiderhiser, J. M.; Shaw, D. S.; Ge, X.; Reiss, D. Trajectories of parenting and child negative emotionality during infancy and toddlerhood: A longitudinal analysis. Child Development. 2011, 82(5), 1661–1675. [CrossRef]

- Giurge, L. M.; Whillans, A. V.; Yemiscigil, A. A. Multicountry perspective on gender differences in time use during COVID-19. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences. 2021, 118(12), e2018494118. [CrossRef]

- Dunatchik, A.; Gerson, K.; Glass, J.; Jacobs, J. A.; Stritzel, H. Gender, parenting, and the rise of remote work during the pandemic: Implications for domestic inequality in the United States. Gender & Society. 2021, 35(2), 194-205. [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsen, K.; Parks-Stamm, E. J.; Kvalø, M.; Olsen, M.; Martiny, S. E. Mothers’ domestic responsibilities and well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown: The moderating role of gender essentialist beliefs about parenthood. Sex Roles. 2022, 87(1-2), 85-98. [CrossRef]

- Swit, C. S.; Breen, R. Parenting during a pandemic: Predictors of parental burnout. Journal of Family Issues. 2022. 0192513X211064858. [CrossRef]

- Weeland, J., Keijsers, L., & Branje, S. Introduction to the special issue: Parenting and family dynamics in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Developmental Psychology.2021, 57(10), 1559. [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; Cattelino, E.; Baiocco, R.; Trumello, C.; Babore, A.; Candelori, C.; Chirumbolo, A. Parents and children during the COVID-19 lockdown: The influence of parenting distress and parenting self-efficacy on children’s emotional well-being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 584645. [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J. A.; Sanders, M. R. Reducing child maltreatment by making parenting programs available to all parents: a case example using the triple p-positive parenting program. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016, 17, 398–407. [CrossRef]

- Turner, K. M.; Singhal, M.; McIlduff, C.; Singh, S.; Sanders, M. R. Evidence-based parenting support across cultures: the Triple P—Positive Parenting Program experience, in Cross-Cultural Family Research and Practice, eds W. K. Halford and F. van de Vijver (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press). 2020, 603–644.

- Vargas Rubilar, J.; Richaud, M. C.; Oros, L. Programa de promoción de la parentalidad positiva en la escuela: un estudio preliminar en un contexto de vulnerabilidad social. Pensando Psicología. 2018, 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Babore, A.; Trumello, C.; Lombardi, L.; Candelori, C.; Chirumbolo, A.; Cattelino, E., ...; Morelli, M. Mothers’ and children’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: The mediating role of parenting stress. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2023. 54(1), 134-146.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).