1. Introduction

Due to its direct relationship with the health-disease process, throughout the life cycle

1, physical activity is one of the priority themes of the global health agenda [

1]. The benefits of physical activity are widely recognized in relation to quality of life [

2] and well-being [

3], as well as the prevention of different diseases [

1] and early mortality [

4].

Apart from these benefits, promoting changes in physical activity is not a quick or simple task, due to its multifaceted nature [

1,

5]. Given the need to recognize the main strategies for increasing physical activity in community level, Heath et al. (2012) indicate the potential of behavioral and social interventions [

6].

Other studies complement this evidence, indicating, for example, the potential of counseling for physical activity in primary health care setting [

7], given the possibility of a wide reach, as well as because counseling is constituted as a good cost-effectiveness educational strategy [

8,

9], based on dialogue and reflection on how physical activity can be inserted in people's lives, considering their life contexts [

10,

11].

However, physical activity counseling can be carried out in many ways, in aspects of theoretical basis, design, time, implementation, and evaluation [

10,

11]. Among these, the 5A model can be highlighted, which is based on the transtheoretical model of behavior change [

12,

13]. Its implementation starts from the recognition of the contexts and needs of the individuals, in order to guide the health care process, being structured from the questioning the behavior (assess), indication of doses and benefits and/or risks (advise), shared action planning (agree), identification of barriers and types of support (assist) and the follow-up and assessment (arrange) [

12,

13].

Previous studies suggest the potential of the 5A model in addressing other behaviors and improvements in health indicators [

14,

15,

16]. Given its potential, the present study was carried on, with the aim of identifying and summarizing the impacts and effectiveness of interventions based on the 5a counseling model on physical activity indicators in adults.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic review was carried out, designed, registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022333797), developed and reported based on previous references [

17,

18]. Its inclusion criteria were based on the “PICOS” structure, established as follows:

“Population”: adults, between 18 and 59 years of age, without impeding conditions for the practice of physical activity;

“Interventions”: the provision of 5A model counselling-based interventions about physical activity, regardless of the duration, the professional nucleus that implemented it and the support of other strategies (e.g., preparation of materials, offer of practical activities);

“Comparators”: who preferably did not receive care, or who received standard care, without offering physical activity counseling based on the 5A model;

“Outcome”: physical activity indicators (e.g., increase in the amount of physical activity, number of steps per day/week, proportion of people meeting the recommendation, self-efficacy for physical activity, etc.) preferably total, or in the leisure time or as a form of transport and;

“Study design”, intervention studies without restrictions regarding the presence of a control group and randomized allocation between groups.

On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were: literature reviews (e.g., narrative, scoping or systematic), other forms of publication, such as dissertations, theses, abstracts and articles published in languages other than English, Portuguese or Spanish.

To identify the studies, systematic searches were conducted in seven electronic databases (Embase, Lilacs, Pubmed, Scielo, Scopus, Sportdiscus and Web of Science), covering the literature available until 16 May 2022. Initially, the search strategy was developed using the Pubmed database: (((physical activity[Text Word]) OR (exercise[Text Word])) OR (walk*[Text Word])) AND (((5A[Text Word]) OR (5As[Text Word])) OR (5A's[Text Word])) and then adapted to the other databases. The full presentation of the systematic searches is available in Supplementary Material 1. Also, to avoid the loss of relevant studies, manual searches were conducted in Google Scholar, based on the terms “physical activity”; “counseling”; “5A”, and in the reference lists of the studies evaluated by their full texts.

Studies identified by systematic searches were entered into Rayyan [

19]. On the platform, duplicates were identified and removed, and titles and abstracts were also screened. Subsequently, the full texts of potential articles were downloaded and assessed, as well as having their data extracted. Assessments and data extraction processes were conducted by two researchers (LS and PG), who worked independently, with the support of a third researcher to resolve doubts and establish consensus (RF).

In the titles and abstracts screening, exclusions were made as soon as the first divergence was identified, according to the inclusion criteria. The reasons for full-text exclusions were registered.

Data extraction was performed in an electronic spreadsheet, divided into three tabs: (I) descriptive data of the studies (e.g., study location, mean age, sample size, percentage of women, study objective, sample characteristics), (II) methodological aspects of the studies (e.g., research design, intervention implementers, research protocol, instruments used in the assessment of physical activity) and (III) results, organized by the physical activity indicators evaluated.

The descriptive synthesis was prepared based on the logic of the extraction spreadsheet (e.g., descriptive, methodological data and results). Through meetings, the researchers evaluated – from the objectives of the present review and previous experiences with other reviews – the main information to be included in the descriptive synthesis, as well as the form of its presentation.

In regard of the measures of effect, we preferably opted for the differences in means (e.g., means and variability of pre- and post-intervention data of the intervention and control groups), to provide better comparability among the findings. In studies that did not show differences in means, data were identified and the calculations were performed in Review Manager 5.4.1 [

20]. In view of the high heterogeneity between studies, metanalysis was not planned.

Risk of bias of included studies was assessed in an adapted version of the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) tool [

21], which assesses seven methodological domains of an intervention study: “selection bias”, “adjustment of confounding variables”, “methods used in data collection”, “losses of and dropouts”, “protocol used in the analysis” and “use of data imputation in the analysis”.

3. Results

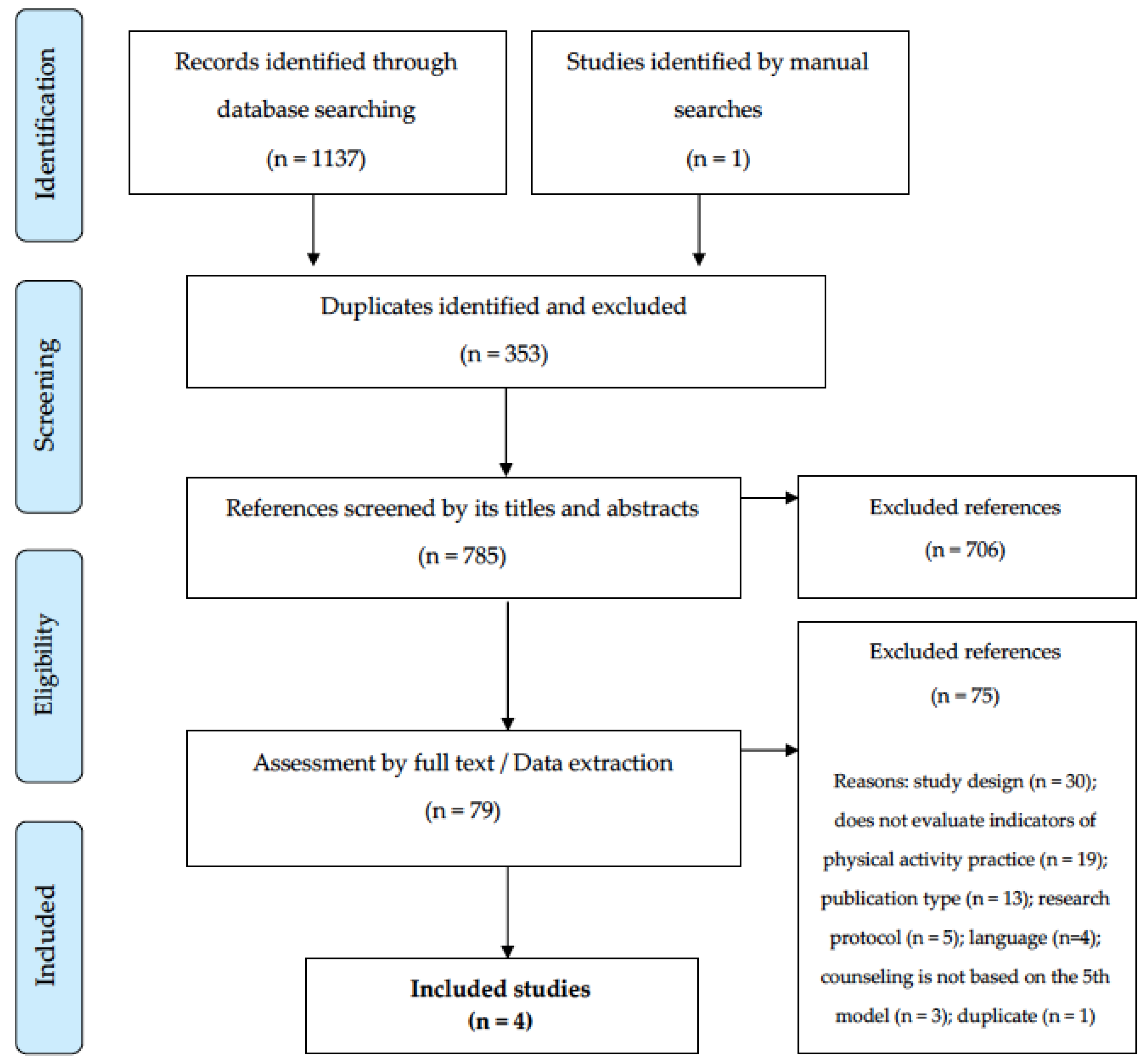

The numbers related to the review process are presented in the Figure 1. Briefly, the systematic searches in the databases and manuals resulted in the identification of 1138 potential references. After removing duplicates (n = 353), 785 titles and abstracts were evaluated. From this process, 79 references remained, later evaluated by their full texts. At the end of this phase, 75 references were excluded, the main reasons being: design (n = 30) and the “non-assessment of indicators of physical activity practice” (n = 19). In the end, four intervention studies adequately responded to all eligibility criteria and composed the descriptive synthesis of the present review [

22,

23,

24,

25].

By country, two studies were carried out in the United States [

23,

24], one in China [

25] and one in Mexico [

22], involving adult populations, with a mean age between 40 [

25] and 55 [

24] years and a majority of women in three studies (

Table 1). Heterogeneity was observed in the profile of the participants, highlighting the involvement of inactive people / people who did not meet the recommendation [

22,

23], populations living in rural setting [

23], overweight or obese veterans [

24] and people with insomnia [

25]. The objectives of the studies converged to assess the effects of interventions based on counseling on physical activity based on the 5A model.

Except for Galaviz et al. (2017) [

22], all studies presented randomization among the participants of the intervention and control groups, with heterogeneity among the implementers of the counseling, highlighting the participation of general practitioners [

22], nurses [

23], health students [

24] and psychologists [

25] (

Table 2). Among the research protocols, it was observed that counseling on physical activity was offered in different settings, such as in the office practice [

22], remote/online [

23,

24], highlighting other support strategies, such as the elaboration of a health action plan [

23], sending messages [

23] and offering educational material [

24] (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Methodological characteristics of the studies included in the synthesis (n = 4).

Table 2.

Methodological characteristics of the studies included in the synthesis (n = 4).

| Reference |

Study design |

Professionals who implemented the intervention |

Study protocol |

| Galaviz et al., 2017 [22} |

Effectiveness-implementation hybrid study |

General practitioners working in the public service |

Previously trained physicians offered counseling based on the 5a model in regular consultations. |

| Reed et al., 2019 [23] |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

Nurses and Researchers |

Elaborating action plans to improve self-regulation and sending motivational weekly text messages. |

| Viglione et al., 2019 [24] |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

Health professionals and students |

Delivery of educational material and counseling (face-to-face and remote). |

| Wang et al., 2015 [25] |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

Psychologists |

Offer of four weekly counseling sessions, adjustment of prescription and sleep restriction strategy. |

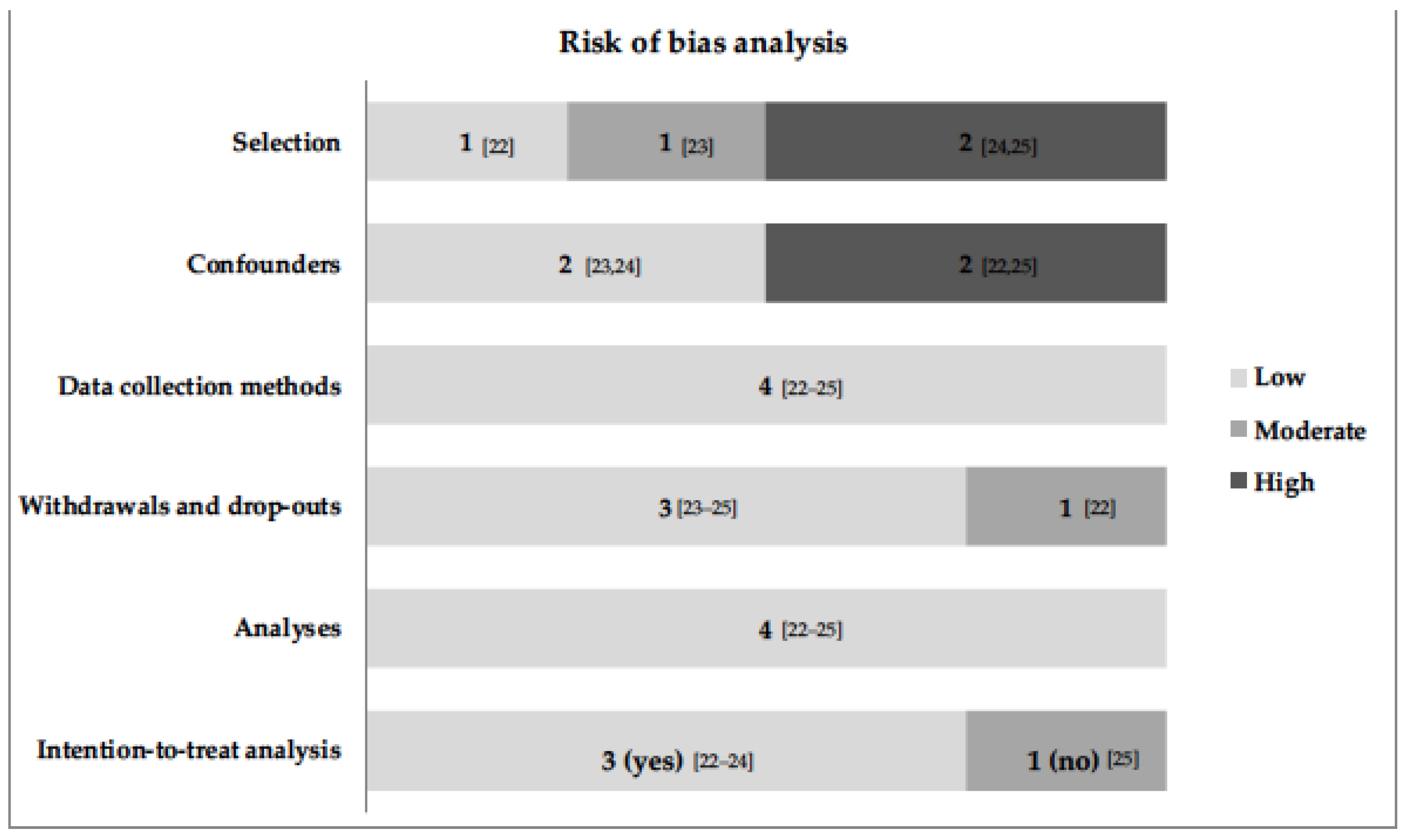

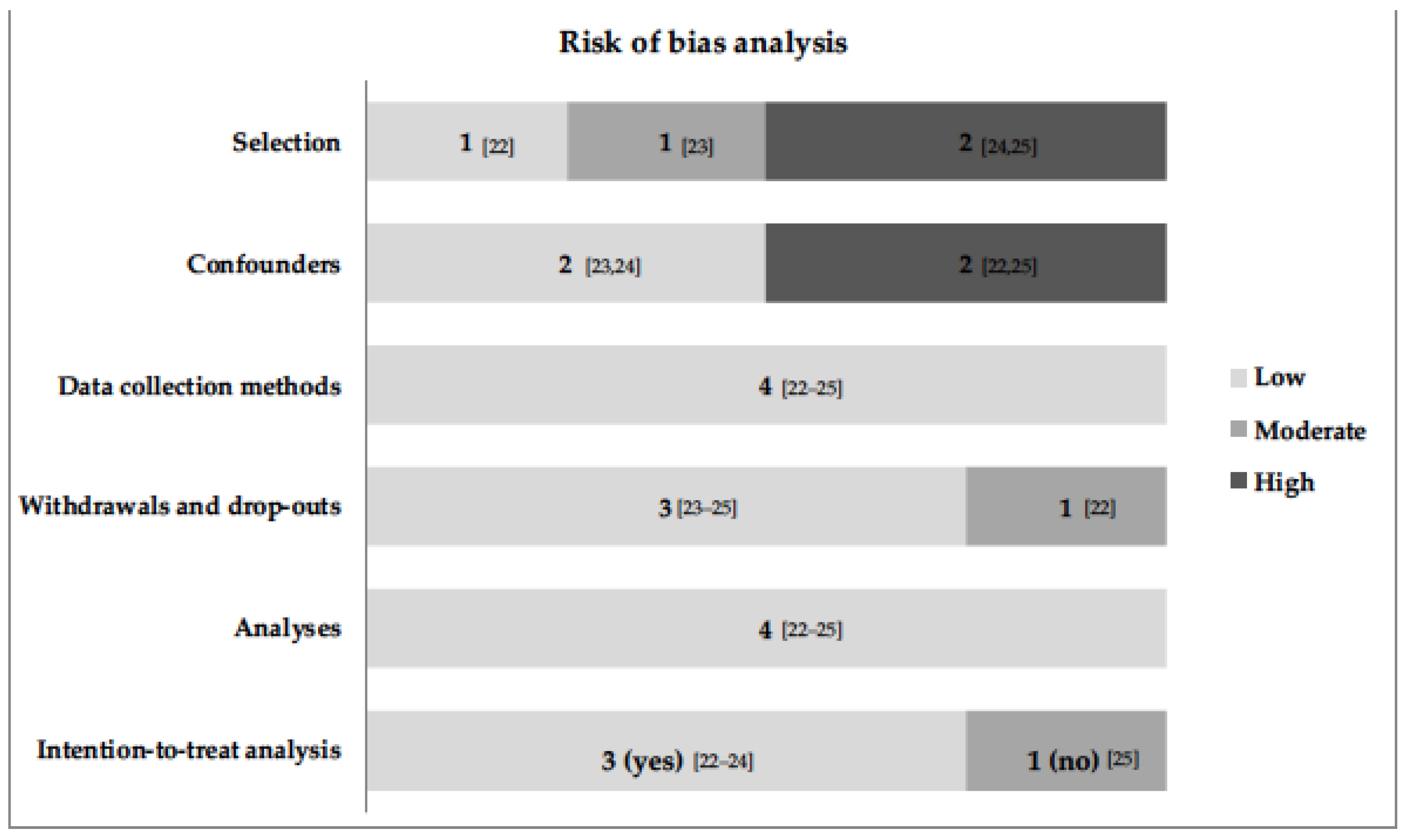

All studies had a low risk of bias in the domains “Methods used in data collection” and “Analysis protocol” (Figure 2). In the domains "Adjustment of confounding variables" and "Selection of participants", the greatest weaknesses were due to the lack of adjustment for the variables that showed differences between groups at baseline [

22], lack of reporting of the information evaluated [

24] and by populations with specific clinical conditions [

24,

25], respectively. Three studies conducted the analysis with imputation of missing data, using the “intention-to-treat” method [22-24].

The included studies evaluated physical activity using different instruments, such as questionnaires [

22,

23,

24,

25] and monitor [

23] (

Table 3). The sample sizes analyzed varied between 43 [

24] and 459 [

22] participants. Heterogeneity was observed between the evaluation times of post-intervention behavior and the physical activity indicators evaluated, highlighting "number of people classified as physically active" [

22], "weekly number of steps" [

23], "weekly minutes" [

23], “self-efficacy for physical activity” [

24]. Overall, only the study by Wang et al. (2015) [

25] showed a statistically significant result between the intervention and control groups in the indicator “daily number of steps” (2,231; 95%CI = 474; 3,987; p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

With the objective of identifying the effectiveness of interventions that carried out the practice of counseling, based on the 5A model, in indicators of physical activity in adults, the present review was elaborated from four original studies, developed in three countries. In only one study, a statistically significant result was observed, related to the increase in the daily number of steps [

25]. In addition, heterogeneity was observed between the profile of the populations studied, research protocols, implementation processes and physical activity indicators evaluated.

The World Health Organization suggests the promotion of physical activity in Primary Health Care, and counseling provided by professionals has shown promising results in behavior change. For this reason, counseling is recommended as part of integrated community interventions [

26]. However, the findings of the present review suggest that there is no consistent evidence supporting the positive effectiveness to recommend the implementation of model 5A in intervention studies to increase the level of physical activity. Thus, it is worth mentioning that none of the studies included involved interpersonal and environmental approaches, in parallel with the provision of counseling.

Other consideration on the results is the time for behavior consolidation. Except in Reed et al. (2019) [

23], who evaluated self-efficacy for physical activity after 12 months, the other indicators of physical activity present in the synthesis were evaluated between three and six months after the start of the intervention. For example, according to the Transtheoretical Model of Prochaska & DiClemente [

27] suggests that six months is the minimum time for the stability of the behavior change that involves the practice of physical activity.

In addition to what is suggested about networks and the environment, it is also worth mentioning the need for longitudinal efforts in the practice of counseling, involving different health professionals and their offer in different settings (e.g., health unit, community spaces, home visits). Future studies can predict the insertion of 5A in a multidisciplinary work logic, considering the potential of action of different health professionals in increasing the physical activity levels [

28].

It is also worth noting the reduced samples, as well as heterogeneity between the samples that participated in the studies. Two interventions were implemented in physically inactive populations, one in an urban setting and another in a rural setting and two other interventions aimed at populations with specific clinical conditions, such as obesity [

24] and insomnia [

25]. A previous study suggests differences in the determinants of physical activity in free time between women living in urban and rural settings [

29], which reduces the comparability between studies. On the other hand, it is necessary to take a more careful look at the practice of counseling on physical activity in populations with more specific clinical conditions, based primarily on their health situation. Thus, we suggest that future research may involve larger and more heterogeneous samples, both in terms of physical activity levels and their clinical condition.

Even though it was not the objective of the present review, we consider it important to mention the lack of a more in-depth report on the application of the 5A model in the practice of counseling on physical activity. Apart from the conceptual similarity between the models used in the studies, we believe that this information is important and, in some way, can guide the practice of counseling on physical activity, given its high frequency, particularly in Primary Health Care settings [

30,

31]. We also consider it important to indicate the main demands and challenges for the application of the model, taking as a suggestion, for example, the structure suggested by Alahmed and Lobelo [

13].

The main limitation of the present review is its small number of studies included in the synthesis. Somehow, we justify it, because it seems that dealing with behavioral research has this difficulty in recruiting and following people for a longer period of time – and this may also be one of the main challenges for evaluating the 5A in future studies. However, it is expected that from the potential of the 5A model in approaching other behaviors, as well as the suggestions presented, future interventions can be designed and conducted, especially in Primary Health Care setting, and may even be tested in systems health services. In addition, we believe that the present review stands out for presenting a more specific synthesis of studies that carried out counseling on physical activity based on the 5A model, given the plurality of theories and models addressed in previous reviews and to guide more specific advances for future studies.

5. Conclusions

Based on data from four interventions conducted in samples of adults, with the exception of increasing the daily number of steps, counseling based on the 5A model did not reflect significant findings in relation to physical activity indicators. Considering that behavior change for many people is neither a simple nor a quick process and that the 5A model is promising for other behavioral indicators, we indicate the need to carry out new intervention studies, with an expanded focus in relation to themes related to physical activity (e.g., types, doses, risks, benefits, identification of barriers and assessment) and, in parallel, the offer of practices in the Primary Health Care setting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.S and P.G. Review design and protocol: L.S and P.G. Title and abstracts screening, Full text assessment and Data extraction: L.S, P.G and R. F. Formal analysis of descriptive synthesis: C.P, C.R., F.C. L.S., P.G. and R.F. Writing—original draft preparation: P.G. Writing—review and editing: C.P, C.R., F.C. L.S. and R.F.; supervision: P.G. Project administration: P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was not funded.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- DiPietro, L., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S. J. H., Borodulin, K., Bull, F. C., Buman, M. P., et al. Advancing the global physical activity agenda: recommendations for future research by the 2020 WHO physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines development group. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 143.

- Vagetti, G. C., Barbosa Filho, V. C., Moreira, N. B., Oliveira, V., Mazzardo, O., Campos W. Association between physical activity and quality of life in the elderly: a systematic review, 2000-2012. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2014, 36(1), 76-88.

- Hyde, A. L., Maher, J. P., Elavsky, S. Enhancing our understanding of physical activity and wellbeing with a lifespan perspective. Int. J. Wellbeing 2013, 3(1), 98-115.

- Samitz, G., Egger, M., Zwahlen, M. Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40(5), 1382-1400.

- Giles-Corti, B., Donovan, R. J. The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54(12), 1793-1812.

- Heath, G. W., Parra, D. C., Sarmiento, O. L., Andersen, L. B., Owen, N., Goenka, S., et al. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet. 2012, 380(9838), 272-81.

- Baker, P. R., Francis, D. P., Soares, J., Weightman, A. L., Foster, C. Community wide interventions for increasing physical activity. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD008366.

- Garrett, S., Elley, C. R., Rose, S. B., O'Dea, D., Lawton, B. A., Dowell, A. C. Are physical activity interventions in primary care and the community cost-effective? A systematic review of the evidence. Br. J. Gen. Pract., 2011, 61(584), e125-33.

- Vijay, G. C., Wilson, E. C., Suhrcke, M., Hardeman, W., Sutton, S., VBI Programme Team. Are brief interventions to increase physical activity cost-effective? A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50(7), 408-417.

- Ainsworth, B. E., Youmans, C. P. Tools for physical activity counseling in medical practice. Obes. Res. 2002, 10 Suppl 1, 69S-75S.

- Gagliardi, A. R., Abdallah, F., Faulkner, G., Ciliska, D., Hicks, A. Factors contributing to the effectiveness of physical activity counselling in primary care: a realist systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98(4), 412-419.

- Carroll, J. K., Fiscella, K., Epstein, R.M., Sanders, M. R., Williams, G. C. A 5A's communication intervention to promote physical activity in underserved populations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 374.

- Alahmed, Z., Lobelo, F. Physical activity promotion in Saudi Arabia: A critical role for clinicians and the health care system. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health, 2018, 7 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S7-S15.

- Vallis, M., Piccinini-Vallis, H., Sharma, A. M., Freedhoff, Y. Clinical review: modified 5 As: minimal intervention for obesity counseling in primary care. Can. Fam. Physician. 2013, 59(1), 27-31.

- Moattari, M., Ghobadi, A., Beigi, P., Pishdad, G. Impact of self-management on metabolic control indicators of diabetes patients. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2012, 11(1), 6.

- Welzel, F. D., Bär, J., Stein, J., Löbner, M., Pabst, A., Luppa, M., Grochtdreis, T., Kersting, A., Blüher, M., Luck-Sikorski, C., König, H. H., Riedel-Heller, S. G. Using a brief web-based 5A intervention to improve weight management in primary care: results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22(1), 61.

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A. C., Welch, V. A., Whiting, P., McKenzie, J. E. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372, n160.

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 2022. Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (Accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5(1), 210.

- Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020.

- Guerra, P. H., Soares, H. F., Mafra, A. B., Czarnobai, I., Cruz, G. A., Weber, W. V., Farias, J. C. H., Loch, M. R., Ribeiro, E. H. C. Educational interventions for physical activity among Brazilian adults: systematic review. Rev. Saude. Publica. 2021, 55, 110.

- Galaviz, K. I., Estabrooks, P. A., Ulloa, E. J., Lee, R. E., Janssen, I., López, Y., Taylor, J., Ortiz-Hernández, L., Lévesque, L. Evaluating the effectiveness of physician counseling to promote physical activity in Mexico: an effectiveness-implementation hybrid study. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017, 7(4), 731-740.

- Reed, J. R., Estabrooks, P., Pozehl, B., Heelan, K., Wichman, C. Effectiveness of the 5A's model for changing physical activity behaviors in rural adults recruited from Primary Care Clinics. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2019, 16(12), 1138-1146.

- Viglione, C., Bouwman, D., Rahman, N., Fang, Y., Beasley, J. M., Sherman, S., Pi-Sunyer, X., Wylie-Rosett, J., Tenner, C., Jay, M. A technology-assisted health coaching intervention vs. enhanced usual care for Primary Care-based obesity treatment: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Obes. 2019, 6, 4.

- Wang, J., Yin, G., Li, G., Liang, W., Wei, Q. Efficacy of physical activity counseling plus sleep restriction therapy on the patients with chronic insomnia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2771-2778.

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. 2018. Geneva. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf. (Accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Prog. Behav. Modif. 1992, 28, 183-218.

- Costa, E. F., Guerra, P. H., Santos, T. I., Florindo, A. A. Systematic review of physical activity promotion by community health workers. Prev Med. 2015, 81, 114-121.

- Wilcox, S., Castro, C., King, A. C., Housemann, R., Brownson, R. C. Determinants of leisure time physical activity in rural compared with urban older and ethnically diverse women in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000, 54(9), 667-672.

- Florindo, A. A., Mielke, G. I., Gomes, G. A., Ramos, L. R., Bracco, M. M., Parra, D. C., Simoes, E. J., Lobelo, F., Hallal, P. C. Physical activity counseling in primary health care in Brazil: a national study on prevalence and associated factors. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13, 794.

- Füzéki, E., Weber, T., Groneberg, D. A., Banzer, W. Physical Activity Counseling in Primary Care in Germany-An Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17(15), 5625.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the studies included in the synthesis (n = 4).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the studies included in the synthesis (n = 4).

| Reference |

Country |

Mean age (% of women) |

Sample characteristics |

Main objective |

| Galaviz et al., 2017 [22} |

México |

49 (77) |

Adults who do not meet physical activity recommendations but without clinical impediments |

Increase the use of the 5A model in counseling and observe whether the intervention provided an increase in users' physical activity. |

| Reed et al., 2019 [23] |

United States |

48 (80) |

Inactive adults assisted by a primary health care unit located in a rural setting |

Test the use of the 5A model in counseling to increase physical activity |

| Viglione et al., 2019 [24] |

United States |

55 (33) |

Veterans with a BMI ≥30kg/m2 or between 25 and 29.9km/m2 diagnosed with some comorbidity (hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, high cholesterol, prediabetes and metabolic syndrome) |

Determine the feasibility and acceptability of a technology-based method compared to usual care. Test the impact of this method on weight, diet and physical activity |

| Wang et al., 2015 [25] |

China |

40 (65) |

Adults with chronic insomnia |

To verify the effects of a counseling-based intervention on physical activity and sleep restriction |

Table 3.

Physical activity indicators, assessment and results of the included studies (n = 4).

Table 3.

Physical activity indicators, assessment and results of the included studies (n = 4).

| Reference |

Tools used to assess physical activity |

Intervention Group |

Control Group |

Physical activity indicator (time in which the assessment took place) |

Result |

| Galaviz et al., 2017 [22] |

Questionnaire GLTEQ |

228* |

231 |

Physical activity score (6 months post-intervention) |

data were not statistically significant (numbers were not presented in the report) |

| Number of people classified as physically active (6 months post-intervention) |

data were not statistically significant (numbers were not presented in the report) |

| Reed et al., 2019 [23] |

Questionnaire GLTEQ; Fitbit Charge 2 |

29 |

30 |

Assessment by questionnaire (4 months) |

8.1 (95%CI = 0.1; 16.1) |

| Weekly number of steps (4 months) |

1266 (95%CI = -520; 3052) |

| Active weekly minutes (4 months) |

42 (95%CI = -102; 186) |

| Viglione et al., 2019 [24] |

Paffenbarger Physical Activity Questionnaire |

21 |

22 |

Self-efficacy for physical activity (3 months) |

-1.1 (95%CI = -6.8; 4.7); |

| Self-efficacy for physical activity (6 months) |

2.1 (95%CI = -4.5; 8.8) |

| Self-efficacy for physical activity (12 months) |

-2.2 (95%CI = -9.1; 4.1) |

| Wang et al., 2015 [25] |

IPAQ Long version |

35 |

36 |

Daily number of steps (4 months) |

2231 (95%CI = 474; 3987) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).