Submitted:

09 May 2023

Posted:

10 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. General considerations on gender differences in cancer susceptibility and oxidative stress

2. Molecular mechanisms of sex disparities

3. Sex differences in oxidative stress and neoplastic diseases

3.1. Glioma, oxidative stress and gender differences

3.2. Liver cancer, oxidative stress and gender differences

3.3. Colorectal cancer, oxidative stress and gender differences

3.4. Lung cancer, oxidative stress and gender differences

3.5. Melanoma, oxidative stress and gender differences

3.6. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, oxidative stress and gender differences

4. Future perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dorak, M.T.; Karpuzoglu, E. Gender differences in cancer susceptibility: an inadequately addressed issue. Front Genet. 2012, 3, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, D.J. A male-female differential in tumour incidence. Br. J. Cancer 1969, 23, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgren, G.; Liang, L.; Adami, H.O.; Chang, E.T. Enigmatic sex disparities in cancer incidence. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012, 27, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.B.; McGlynn, K.A.; Devesa, S.S.; Freedman, N.D.; Anderson, W.F. Sex disparities in cancer mortality and survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011, 20, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlus, M.; Elies, L.; Fouque, M.C.; Maliver, P.; Schorsch, F. Historical control data of neoplastic lesions in the Wistar Hannover Rat among eight 2-year carcinogenicity studies. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2013, 65, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadekar, S.; Peddada, S.; Silins, I.; French, J.E.; Högberg, J.; Stenius, U. Gender differences in chemical carcinogenesis in National Toxicology Program 2-year bioassays. Toxicol Pathol. 2012, 40, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifarth, J.E.; McGowan, C.L.; Milne, K.J. Sex and life expectancy. Gend Med. 2012, 9, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thannickal, V.J.; Fanburg, B.L. Reactive oxygen species in cell signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2000, 279, L1005e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olinski, R.; Zastawny, T.; Budzbon, J.; Skokowski, J.; Zegarski, W. , Dizaroglu, M. DNA base modifications in chromatin of human cancerous tissues. FEBS Lett 1992, 309, 193e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, E.M.; Grisham, M.B. Inflammation, free radicals, and antioxidants. Nutrition 1996, 12, 274e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavata, L.; Aguilaniu, H.; Pichova, A.; Nystrom, T. The oncogenic RAS2(val19) mutation locks respiration, independently of PKA, in a mode prone to generate ROS. EMBO J 2003, 22, 3337e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafa, O.; Wade, M.; Kern, S.; Beeche, M.; Pandita, T.K.; Hampton, G.M.; Wahl, G.M. c-Myc can induce DNA damage, increase reactive oxygen species, and mitigate p53 function: a mechanism for oncogene-induced genetic instability. Mol Cell 2002, 9, 1031e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozben, T. Oxidative stress and apoptosis: impact on cancer therapy. J Pharm Sci 2007, 96, 2181e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbesi, S.; Musolino, C.; Allegra, A.; Saija, A.; Morabito, F.; Calapai, G.; Gangemi, S. Oxidative stress in oncohematologic diseases: an update. Expert Rev Hematol. 2013, 6, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musolino, C.; Allegra, A.; Saija, A.; Alonci, A. , Russo, S.; Spatari, G.; Penna, G., Gerace, D.; Cristani, M.; David, A.; Saitta, S., Gangemi, S. Changes in advanced oxidation protein products, advanced glycation end products, and s-nitrosylated proteins, in patients affected by polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Clin Biochem. 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, S.; Allegra, A.; Alonci, A.; Cristani, M.; Russo, S.; Speciale, A.; Penna, G.; Spatari, G.; Cannavò, A.; Bellomo, G.; Musolino, C. Increase of novel biomarkers for oxidative stress in patients with plasma cell disorders and in multiple myeloma patients with bone lesions. Inflamm Res. 2012, 61, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegra, A.; Tonacci, A.; Giordano, L.; Musolino, C.; Gangemi, S. Targeting Redox Regulation as a Therapeutic Opportunity against Acute Leukemia: Pro-Oxidant Strategy or Antioxidant Approach? Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegra,A. ; Petrarca, C.; Di Gioacchino, M.; Casciaro, M.; Musolino, C.; Gangemi, S. Modulation of Cellular Redox Parameters for Improving Therapeutic Responses in Multiple Myeloma. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Högberg, J.; Hsieh, J.H.; Auerbach, S.; Korhonen, A.; Stenius, U.; Silins, I. Gender differences in cancer susceptibility: role of oxidative stress. Carcinogenesis. 2016, 37, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, T.; Tsutsui, H.; Ohashi, N.; Hayashidani, S.; Suematsu, N.; Tsuchihashi, M.; Tamai, H.; Takeshita, A. Greater oxidative stress in healthy young men compared with premenopausal women. ATVB 2002, 22, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niveditha, S.; Deepashree, S.; Ramesh, S.R.; Shivanandappa, T. Sex differences in oxidative stress resistance in relation to longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2017, 187, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barp, J.; Araújo, A.S.; Fernandes, T.R.; Rigatto, K.V.; Llesuy, S.; Bello-Klein,´A. ; Singal, P. Myocardial antioxidant and oxidative stress changes due to sex hormones. Braz. J. Med Biol. Res 2002, 35, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kander, M.C.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Z. Gender difference in oxidative stress: a new look at the mechanisms for cardiovascular diseases. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borras, C.; Sastre, J.; García-Sala, D.; Lloret, A.; Pallardo, F.V.; Vina, J. 2003. Mitochondria from females exhibit higher antioxidant gene expression and lower oxidative damage than males. Free Radic. Biol. Med, /: 546–552. https, 1016. [Google Scholar]

- Miquel, J.; Economos, A.C.; Fleming, J.; Johnson Jr., J.E. Mitochondrial role in cell aging. Exp. Gerontol. 1980, 15, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohal, R.S.; Sohal, B.H.; Brunk, U.T. Relationship between antioxidant defenses and longevity in different mammalian species. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1990, 53, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barja, G.; Cadenas, S.; Rojas, C.; Perez-Campo, R.; Lopez-Torres, M. Low mitochondrial free radical production per unit O2 consumption can explain the simultaneous presence of high longevity and high aerobic metabolic rate in birds (Oct). Free Radic. Res 1994, 21, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barja, G. Updating the mitochondrial free radical theory of aging: an integrated view, key aspects, and confounding concepts. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2013, 19, 1420–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.A.; Drummond, G.R.; Mast, A.E.; Schmidt, H.H.; Sobey, C.G. Effect of gender on NADPH-oxidase activity, expression, and function in the cerebral circulation: role of estrogen. Stroke 2007, 38, 2142–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Núnez, V.M.; Beristain-Perez, A.; Perez-Vera, S.P.; Altamirano-Lozano, M.A. Age-related sex differences in glutathione peroxidase and oxidative DNA damage in a healthy Mexican population. J. Women’s. Health (Larchmt.). [CrossRef]

- Kendall, B.; Eston, R. Exercise-induced muscle damage and the potential protective role of estrogen. Sports Medicine 2002, 32, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolkiewicz, J.; Michalak, E.; Pospieszna, B.; Deskur-Smielecka, E.; Nowak, A.; Pilaczynska-Szczesniak, L. Response of oxidative stress markers and antioxidant parameters to an 8- week aerobic physical activity program in healthy, postmenopausal women. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2009, 49, e67–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, N.V.; Rychkova, L.V.; Darenskaya, M.A.; Kolesnikov, S.I.; Nikitina, O.A.; Petrova, A.G.; Vyrupaeva, E.V.; Kolesnikova, L.I. Superoxide Dismutase Activity in Male and Female Patients of Different Age with Moderate COVID-19. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med 2022, 173, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ji, L.L.; Liu, T.Y.; Wang, Z.T. Evaluation of gender-related differences in various oxidative stress enzymes in mice. Chin. J. Physiol. 2011, 54, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobocanec, S.; Balog, T.; Sverko, V.; Marotti, T. Sex-dependent antioxidant enzyme activities and lipid peroxidation in ageing mouse brain. Free Radic. Res 2003, 37, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q.; Sheng, Y.; Jiang, P.; Ji, L.; Xia, Y.; Min, Y.; Wang, Z. , 2011. The gender- dependent difference of liver GSH antioxidant system in mice and its influence on isoline-induced liver injury. Toxicology. [CrossRef]

- Vina, J.; Borras, C.; Gambini, J.; Sastre, J.; Pallardo, F.V. Why females live longer than males: control of longevity by sex hormones. Sci. Aging Knowl. Environ. 2005, (23), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erden Inal, M.; Akgün, A.; Kahraman, A. The effects of exogenous glutathione on reduced glutathione level, glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase activities of rats with different ages and gender after whole-body Γ-irradiation. AGE 2003, 26, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkazemi, D.; Rahman, A.; Habra, B. Alterations in glutathione redox homeostasis among adolescents with obesity and anemia. Sci. Rep. /: 3034. https, 3034. [Google Scholar]

- Bellanti, F.; Matteo, M.; Rollo, T.; De Rosario, F.; Greco, P.; Vendemiale, G.; Serviddio, G. Sex hormones modulate circulating antioxidant enzymes: impact of estrogen therapy. Redox Biol. 2013, 1, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, J.; Navarro, I.; Alabadí, B.; Bosch-Sierra, N.; Benito, E.; Civera, M. : Ascaso, J.F.; Martinez-Hervas, S.; Real, J.T. Gender differences on oxidative stress markers and complement component C3 plasma values after an oral unsaturated fat load test. Clin. Invest. Arterioscler. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Pandeya, N.; Byrnes, G.; Renehan, P.A.G.; Stevens, G.A.; Ezzati, P.M.; Ferlay, J.; Miranda, J.J.; Romieu, I.; Dikshit, R.; et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to high body-mass index in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2015, 16, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrgiou, M.; Kalliala, I.; Markozannes, G.; Gunter, M.J.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Gabra, H. , Martin-Hirsch, P.; Tsilidis, K.K. Adiposity and cancer at major anatomical sites: umbrella review of the literature. BMJ.

- Renehan, A.G.; Zwahlen, M.; Egger, M. Adiposity and cancer risk: new mechanistic insights from epidemiology. Nat Rev Cancer 2015, 15, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, N.; Strickler, H.D.; Stanczyk, F.Z.; Xue, X.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Rohan, T.E.; Ho, G.Y.; Anderson, G.L.; Potter, J.D.; et al. A prospective evaluation of endogenous sex hormone levels and colorectal cancer risk in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlebowski, R.T.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Ritenbaugh, C.; Hubbell, F.A.; Ascensao, J.; Rodabough, R.J.; Rosenberg, C.A.; Taylor, V.M.; Harris, R.; Chen, C.; et al. Estrogen plus progestin and colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgerinos, K.I.; Spyrou, N.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Dalamaga, M. Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metabolism Clinical and Experimental 2019, 92, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutari, C.; Mantzoros, C.S. Inflammation: a key player linking obesity with malignancies. Metabolism 2018, 81, A3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 48 Deng, T.; Lyon, C.J.; Bergin, S.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Hsueh, W.A. Obesity, inflammation, and cancer. Annu Rev Pathol 2016, 11, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.L.; Chadid, S.; Singer, M.R.; Kreger, B.E.; Denis, G.V. Metabolic health reduces risk of obesity-related cancer in framingham study adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 2014, 23, 2057–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

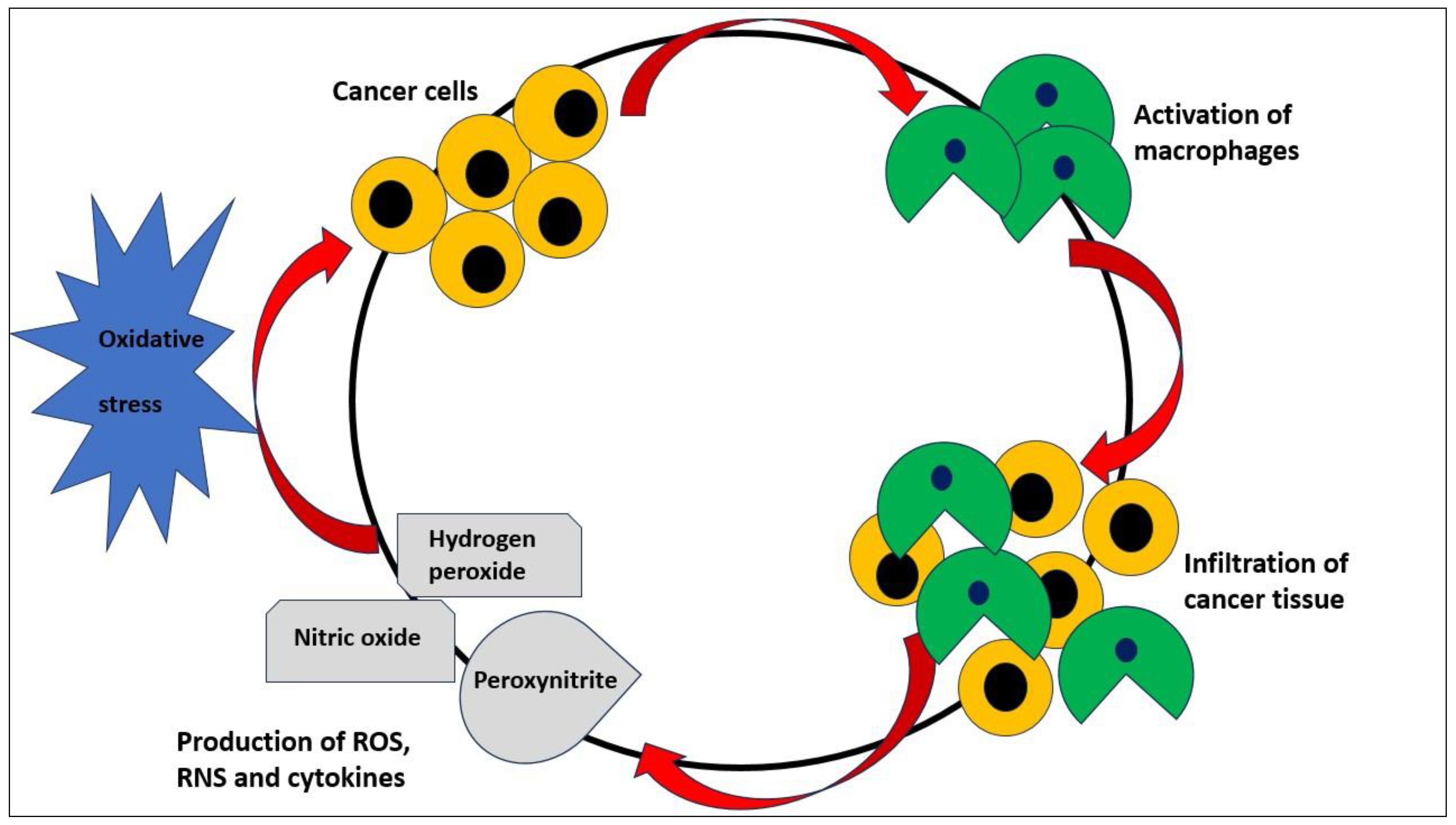

- Sabharwal, S.S.; Schumacker, P.T. Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles' heel? Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikalov, S.I.; Nazarewicz, R.R. Angiotensin II-induced production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: potential mechanisms and relevance for cardiovascular disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 19, 1085–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkwill, F.; Charles, K.A.; Mantovani, A. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell 2005, 7, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, N.M.; Gucalp, A. , Dannenberg, A.J.; Hudis, C.A. Obesity and cancer mechanisms: tumor microenvironment and inflammation. J Clin Oncol, 4270. [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda-Shnaidman, E.; Schwartz, B. Mechanisms linking obesity, inflammation and altered metabolism to colon carcinogenesis. Obes Rev 2012, 13, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

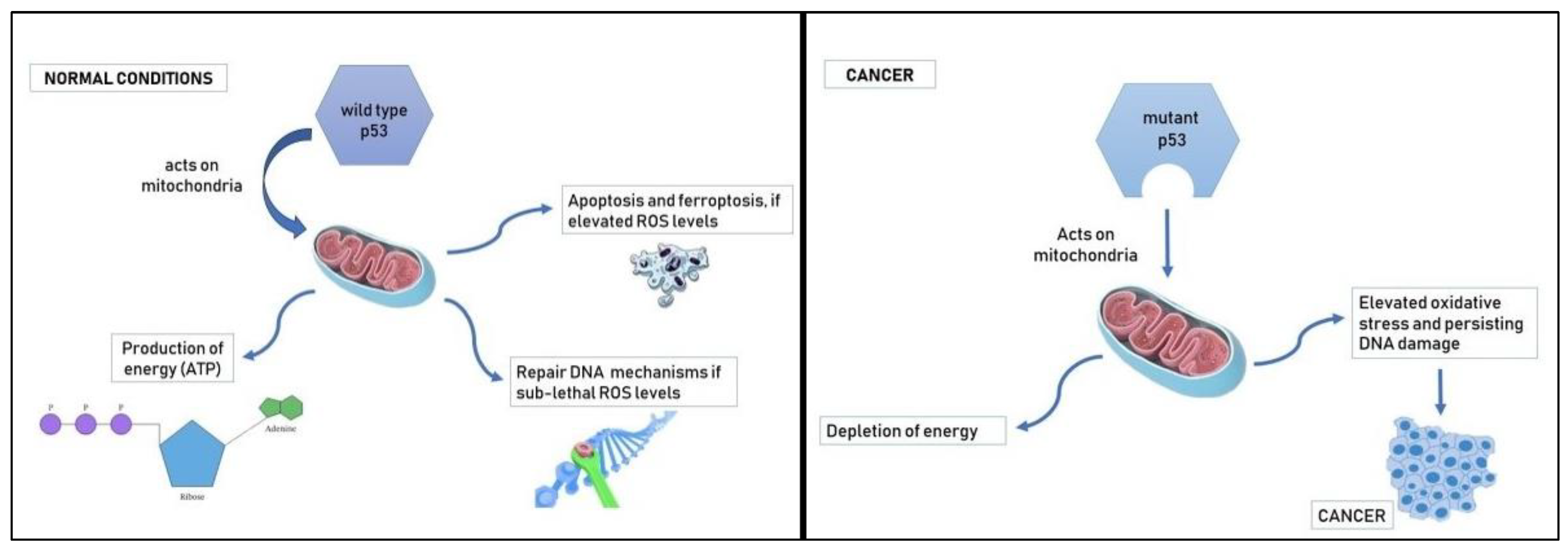

- Fischer, M. Census and evaluation of p53 target genes. Oncogene 2017, 36, 3943–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeland, K. Cell cycle arrest through indirect transcriptional repression by p53: i have a DREAM. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenstein, D.; Litchfield, C.; Caramia, F.; Wright, G.; Solomon, B.J.; Ball, D.; Keam, S.P.; Neeson, P.; Haupt, Y.; Haupt, S. TP53 Status, patient sex, and the immune response as determinants of lung cancer patient survival. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyfuss, K.; Hood, D. A. A systematic review of p53 regulation of oxidative stress in skeletal muscle. Redox Rep. 2018, 23, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebedeva, M.A.; Eaton, J.S. , Shadel, G.S. Loss of p53 causes mitochondrial DNA depletion and altered mitochondrial reactive oxygen species homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Hu, W.; Feng, Z. Tumor suppressor p53 and metabolism. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 11, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beekman, M.; Dowling, D.K.; Aanen, D.K. The costs of being male: are there sex-specific effects of uniparental mitochondrial inheritance? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, S.E.; Ceder, S.; Bykov, V.J.N. , Wiman, K.G. p53 as a hub in cellular redox regulation and therapeutic target in cancer. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 11, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perillo, B.; Di Donato, M.; Pezone, A.; Di Zazzo, E.; Giovannelli, P.; Galasso, G. , Castoria, G.; Migliaccio, A. ROS in cancer therapy: the bright side of the moon. Exp. Mol. Med. [CrossRef]

- Haupt, S.; Haupt, Y. Cancer and Tumour Suppressor p53 Encounters at the Juncture of Sex Disparity. Front Genet. 2021, 12, 632719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, L.A.; Siegel, R.L.; Ward, E.M.; Jemal, A. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends–an update. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Plutynski, A.; Ward, S.; Rubin, J.B. An integrative view on sex differences in brain tumors, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 3323–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Warrington, N.M.; Taylor, S.J.; Whitmire, P.; Carrasco, E.; Singleton, K.W.; Wu, N. , Lathia, J.D.; Berens, M.E.; Kim, A.H.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Swanson, K.R.; Luo, J., Rubin, J.B. Sex differences in GBM revealed by analysis of patient imaging, transcriptome, and survival data. Sci Transl Med. 2019, 11, eaao5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi-Blok, N.; Lee, M.; Sison, J.D.; Miike, R.; Wrensch, M. Inverse association of antioxidant and phytoestrogen nutrient intake with adult glioma in the San Francisco Bay Area: a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2006, 6, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, V.; Jain, A.; Shaghaghi, H.; Summer, R.; Lai, J.C.K.; Bhushan, A. Combination of Biochanin A and Temozolomide Impairs Tumor Growth by Modulating Cell Metabolism in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Ni, Q.; Wang, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, Y. Synergistic anticancer effects of formononetin and temozolomide on glioma C6 cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruszkiewicz, J.A.; Miranda-Vizuete, A.; Tinkov, A.A.; Skalnaya, M.G.; Skalny, A.V.; Tsatsakis, A. , Aschner, M. Sex-Specific Differences in Redox Homeostasis in Brain Norm and Disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2019, 67, 312–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candeias, E.; Duarte, A.I.; Sebastião, I.; Fernandes, M.A.; Plácido, A.I.; Carvalho, C.; Correia, S. , Santos, R.X.; Seiça, R.; Santos, M.S.; Oliveira, C.R.; Moreira, P.I. Middle-Aged Diabetic Females and Males Present Distinct Susceptibility to Alzheimer Disease-like Pathology. Mol Neurobiol. 6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, A.; Gulati, K.; Banerjee, B.D.; Ray, A. Possible involvement of free radicals in the differential neurobehavioral responses to stress in male and female rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2007, 179, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, T.B.; Coburn, J.; Dao, K.; Roqué, P.; Chang, Y.C.; Kalia, V.; Guilarte, T.R.; Dziedzic, J.; Costa, L.G. Sex and genetic differences in the effects of acute diesel exhaust exposure on inflammation and oxidative stress in mouse brain. Toxicology. 2016, 374, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, R.; Santandreu, F.M.; Valle, A.; Gianotti, M.; Oliver, J.; Roca, P. Sex-dependent differences in aged rat brain mitochondrial function and oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katalinic, V.; Modun, D.; Music, I.; Boban, M. Gender differences in antioxidant capacity of rat tissues determined by 2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline 6-sulfonate; ABTS) and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assays. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2005, 140, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.L.A.; Braz, G.R.F.; Silva, S.C.A.; Pedroza, A.A.D.S.; Freitas, C.M.; Ferreira, D.J.S.; da Silva, A.I.; Lagranha, C.J. Serotonin transporter inhibition during neonatal period induces sex-dependent effects on mitochondrial bioenergetics in the rat brainstem. Eur J Neurosci. 2018, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobočanec, S.; Balog, T.; Kušić, B.; Šverko, V.; Šarić, A.; Marotti, T. Differential response to lipid peroxidation in male and female mice with age: correlation of antioxidant enzymes matters. Biogerontology 2008, 9, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, R.; Gianotti, M.; Roca, P.; Oliver, J. Age and sex-related changes in rat brain mitochondrial function. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. /: 201–206. https, 1016. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, M.E.; Metzger, D.B. A sex difference in oxidative stress and behavioral suppression induced by ethanol withdrawal in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2016, 314, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, H.; Kayali, R.; Çakatay, U. The chance of gender dependency of oxidation of brain proteins in aged rats. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. /: 16–19. https, 1016. [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa, A.R.; Abdel-Rahman, E.A.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Ali, M.H.; Noureldin, M. , Saber, S.H.; Mohsen, M.; Ali, S.S. Sex-specific differences in mitochondria biogenesis, morphology, respiratory function, and ROS homeostasis in young mouse heart and brain. Physiol Rep. 2017, 5, e13125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloret, A.; Badía, M.C.; Mora, N.J.; Ortega, A.; Pallardó, F.V.; Alonso, M.D.; Atamna, H.; Viña, J. Gender and age-dependent differences in the mitochondrial apoptogenic pathway in Alzheimer's disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008, 44, 2019–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dkhil, M.A.; Al-Shaebi, E.M.; Lubbad, M.Y.; Al-Quraishy, S. Impact of sex differences in brain response to infection with Plasmodium berghei. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenbrink, G.; Hakenhaar, F.S.; Salomon, T.B.; Petrucci, A.P.; Sandri, M.R.; Benfato, M.S. Antioxidant enzymes activities and protein damage in rat brain of both sexes. Exp. Gerontol. 2006, 41, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krolow, R.; Noschang, C.G.; Arcego, D.; Andreazza, A.C.; Peres, W.; Gonçalves, C.A.; Dalmaz, C. Consumption of a palatable diet by chronically stressed rats prevents effects on anxiety-like behavior but increases oxidative stress in a sex-specific manner. Appetite 2010, 55, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mármol, F.; Rodríguez, C.A.; Sánchez, J.; Chamizo, V.D. Anti-oxidative effects produced by environmental enrichment in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of male and female rats. Brain Res. 2015, 1613, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 88 Noschang, C.; Krolow, R.; Arcego, D.M.; Toniazzo, A.P.; Huffell, A.P.; Dalmaz, C. Neonatal handling affects learning, reversal learning and antioxidant enzymes activities in a sex-specific manner in rats. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2012, 30, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocardo, P.S.; Boehme, F.; Patten, A.; Cox, A.; Gil-Mohapel, J.; Christie, B.R. , Anxiety and depression-like behaviors are accompanied by an increase in oxidative stress in a rat model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: protective effects of voluntary physical exercise. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 1607–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charradi, K.; Mahmoudi, M.; Bedhiafi, T.; Kadri, S.; Elkahoui, S.; Limam, F.; Aouani, E. Dietary supplementation of grape seed and skin flour mitigates brain oxidative damage induced by a high-fat diet in rat: Gender dependency. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017, 87, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Llort, L.; García, Y.; Buccieri, K.; Revilla, S.; Suñol, C.; Cristofol, R.; Sanfeliu, C. Gender-specific neuroimmunoendocrine response to treadmill exercise in 3xTg-AD mice. Int. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, G.; Venkateshappa, C.; Mahadevan, A.; Pruthi, N. ; Srinivas, Bharath, M.M.; Shankar, S.K. Effect of premortem and postmortem factors on the distribution and preservation of antioxidant activities in the cytosol and synaptosomes of human brains. Biopreserv. Biobanking. [CrossRef]

- Engler-Chiurazzi, E.B.; Brown, C.M.; Povroznik, J.M.; Simpkins, J.W. Estrogens as neuroprotectants: estrogenic actions in the context of cognitive aging and brain injury. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 157, 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Kelley, M.H.; Herson, P.S.; Hurn, P.D. Neuroprotection of sex steroids. Minerva Endocrinol. 2010, 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, A.N.; Siddiqui, N.; Khan, R.A.; Kalam, A.; Jabir, N.R.; Kamal, M.A.; Firoz, C.K.; Tabrez, S. Neuroprotective Role of Steroidal Sex Hormones: An Overview. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016, 22, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spychala, M.S.; Honarpisheh, P.; McCullough, L.D. Sex differences in neuroinflammation and neuroprotection in ischemic stroke. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 95, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillinan, N.; Deng, G.; Grewal, H.; Herson, P.S. Androgens and stroke: good, bad or indifferent? Exp. Neurol. 2014, 259, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, D.S.; Bakshi, K. Neurosteroids: biosynthesis, molecular mechanisms, and neurophysiological functions in the human brain. Horm. Signal. Biol. Med. 2020, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, C.; Karali, K.; Fodelianaki, G.; Gravanis, A.; Chavakis, T.; Charalampopoulos, I.; Alexaki, V.I. Neurosteroids as regulators of neuroinflammation. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2019, 55, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illan-Cabeza, N.A.; Garcia-Garcia, A.R.; Martinez-Martos, J.M.; Ramirez-Exposito, M.J.; Pena-Ruiz, T.; Moreno-Carretero, M.N. A potential antitumor agent, (6-amino-1-methyl-5-nitrosouracilato-N3)-triphenylphosphinegold(I): Structural studies and in vivo biological effects against experimental glioma. European Journal of Medical Chemistry,.

- Ramirez-Exposito, M.J.; Martinez-Martos, J.M. The Delicate Equilibrium between Oxidants and Antioxidants in Brain Glioma. Current Neuropharmacology,.

- Martínez-MartosJ.M., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Mayas, M.D.; Carrera, P.; Arias de Saavedra, J.M.; Sánchez-Agesta, R.; Marcela Arrazola, M.; Ramírez-Expósito, M.J. 103. Martínez-MartosJ.M.; Mayas, M.D.; Carrera P.; Arias de Saavedra, J.M.; Sánchez-Agesta, R.; Marcela Arrazola, M.; Ramírez-Expósito, M.J. Phenolic compounds oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol exert differential effects on glioma development via antioxidant defense systems. J Functional Food.

- Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Carrera-González, M.P.; Mayas, M.D.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Gender differences in the antioxidant response of oral administration of hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein against N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced glioma. Food Res Int. 2021, 140, 110023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Mayas, M.D.; Carrera-González, M.P.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Gender Differences in the Antioxidant Response to Oxidative Stress in Experimental Brain Tumors. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2019, 19, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A.; Llovet, J.M. Liver cancer in 2013: mutational landscape of HCC-the end of the beginning. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Serag, H.B. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011, 365, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, J.; Peters, M.G. Liver disease in women: the influence of gender on epidemiology, natural history, and patient outcomes. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 9, 633–639. [Google Scholar]

- Vesselinovitch, S.D.; Mihailovich, N.; Wogan, G.N.; Lombard, L.S.; Rao, K.V.; Sugamori, K.S.; Brenneman, D.; Sanchez, O.; Doll, M.A.; Hein, D.W.; et al. Reduced 4-aminobiphenyl-induced liver tumorigenicity but not DNA damage in arylamine N-acetyltransferase null mice. Cancer Lett. 2012, 318, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramenzi, A.; Caputo, F.; Biselli, M.; Kuria, F.; Loggi, E.; Andreone, P.; Bernardi, M. Review article: alcoholic liver disease--pathophysiological aspects and risk factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006, 24, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, S. Classification of alcohol metabolizing enzymes and polymorphisms--specificity in Japanese. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2001, 36, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brandon-Warner, E.; Walling, T.L.; Schrum, L.W.; McKillop, I.H. Chronic ethanol feeding accelerates hepatocellular carcinoma progression in a sex-dependent manner in a mouse model of hepatocarcinogenesis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012, 36, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, K.; Komura, S.; Watanabe, I.; Nakagawa, Y.; Yagi, K. Effect of estrogens on serum and liver lipid peroxide levels in mice. J Clin Biochem Nutr 1987, 3, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacort, M.; Leal, A.M.; Liza, M.; Martín, C.; Martínez, R.; Ruiz-Larrea, M.B. Protective effect of estrogens and catecholestrogens against peroxidative membrane damage in vitro. Lipids 1995, 30, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoya, T.; Shimizu, I.; Zhou, Y.; Okamura, Y.; Inoue, H.; Lu, G.; Itonaga, M.; Honda, H.; Nomura, M.; Ito, S. Effects of idoxifene and estradiol on NF-kappaB activation in cultured rat hepatocytes undergoing oxidative stress. Liver 2001, 21, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Shimizu, I.; Lu, G.; Itonaga, M.; Cui, X.; Okamura, Y.; Shono, M.; Honda, H.; Inoue, S.; Muramatsu, M.; Ito, S. Idoxifene and estradiol enhance antiapoptotic activity through estrogen receptor-beta in cultured rat hepatocytes. Dig Dis Sci 2003, 48, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Mukaide, M.; Orito, E.; Yuen, M.F.; Ito, K.; Kurbanov, F.; Sugauchi, F.; Asahina, Y.; Izumi, N.; Kato, M.; Lai, C.L.; Ueda, R.; Mizokami, M. Specific mutations in enhancer II/core promoter of hepatitis B virus subgenotypes C1/C2 increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2006, 45, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slocum, S.L.; Kensler, T.W. Nrf2: control of sensitivity to carcinogens. Arch Toxicol. 2011, 85, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, Y.; Umemura, T.; Kanki, K.; Kodama, Y.; Kitamoto, S.; Saito, K.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Masegi, T.; Nishikawa, A.; Hirose, M. Increased susceptibility to hepatocarcinogenicity of Nrf2-deficient mice exposed to 2-amino-3-methylimidazo [4,5-f]quinoline. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimmulappa, R.K.; Lee, H.; Rangasamy, T.; Reddy, S.P.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Biswal, S. Nrf2 is a critical regulator of the innate immune response and survival during experimental sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2006, 116, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wruck, C.J.; Streetz, K.; Pavic, G.; Götz, M.E.; Tohidnezhad, M.; Brandenburg, L.O.; Varoga, D.; Eickelberg, O.; Herdegen, T.; Trautwein, C.; Cha, K.; Kan, Y.W.; Pufe, T. Nrf2 induces interleukin-6 (IL-6) expression via an antioxidant response element within the IL-6 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2011, 286, 4493–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, D.; Riedmaier, A.E.; Sugamori, K.S.; Grant, D.M. Influence of sex and developmental stage on acute hepatotoxic and inflammatory responses to liver procarcinogens in the mouse. Toxicology 2016, 373, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shupe, T.; Sell, S. Low hepatic glutathione S-transferase and increased hepatic DNA adduction contribute to increased tumorigenicity of aflatoxin B1 in newborn and partially hepatectomized mice. Toxicol Lett. [CrossRef]

- Eaton, D.L.; Gallagher, EP. Mechanisms of aflatoxin carcinogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994, 34, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egner, P.A.; Groopman, J.D.; Wang, J.S.; Kensler, T.W.; Friesen, M.D. Quantification of aflatoxin-B1-N7-Guanine in human urine by high-performance liquid chromatography and isotope dilution tandem mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006, 19, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.R.; Ilic, Z.; Guest, I.; Milne, G.L.; Hayes, J.D.; Sell, S. Characterization of liver injury, oval cell proliferation and cholangiocarcinogenesis in glutathione S-transferase A3 knockout mice. Carcinogenesis. 2017, 38, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Hornick, C.A. Modulation of lipid metabolism at rat hepatic subcellular sites by female sex hormones. Biochim Biophys Acta 1995, 1254, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Lavigne, J.A.; Trush, M.A.; Yager, J.D. (1999) Increased mitochondrial superoxide production in rat liver mitochondria, rat hepatocytes, and HepG2 cells following ethinyl estradiol treatment. Toxicol Sci 1990, 52, 224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, M.; Astre, C.; Segala, C.; Saintot, M.; Scali, J.; Simony Lafontaine, J.; Grenier, J.; Pujol, H. Tumor progression and oxidant-antioxidant status. Cancer Lett 1997, 114, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sverko, V.; Sobocanec, S.; Balog, T.; Marotti, T. Age and gender differences in antioxidant enzyme activity: potential relationship to liver carcinogenesis in male mice. Biogerontology. 2004, 5, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coto-Montes, A.; Boga, J.A.; Tomas-Zapico, C.; Rodriguez Colunga, M.J.; Martinez-Fraga, J.; Tolivia-Cadrecha, D.; Manendez, G.; Herdeband, R.; Tolivia, D. Physiological oxidative stress model: syrian hamster harderian gland-sex differences in antioxidant enzymes. Free Radical Bio Med 2001, 30, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberley, L.W.; Oberley, T.D. Role of antioxidant enzymes in cell immortalization and transformation. Mol Cell Biochem 1988, 84, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.M.; Bosman, C.B.; Sier, C.F.; Griffioen, G.; Kubben, F.J.; Lamers, C.B.; van Krieken, J.H.; van de Velde, C.J.; Verspaget, H.W. Superoxide dismutase in relation to the overall survival of colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 1998, 78, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, S.K.; Zhang, H.J.; Yan, T.; Oberley, L.W.; Aggarwal, B.B. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase suppresses tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis and activation of nuclear transcription factor-jB and activated protein-1. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 13245–13254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatrowski, T.P.; Nathan, C.F. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Res 1991, 51, 794–798. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R.; Salvador, A.; Moradas-Ferreira, P. Why does SOD overexpression sometimes enhance, sometimes decrease, hydrogen peroxide production? A minimalist explanation. Free Radical Bio Med 2022, 32, 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigeolet, E.; Corbisier, P.; Houbion, A.; Lambert, D.; Michiels, C.; Raes, M.; Zachary, M.D.; Remacle, J. Glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase and catalase inactivation by peroxides and oxygen-derived free radicals. Mech Ageing Dev.

- Gonzales, M.J. Lipid peroxidation and tumor growth: an inverse relationship. Med Hypotheses 1992, 38, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Sugamori KS, Tung A, McPherson JP, Grant DM. N-hydroxylation of 4-aminobiphenyl by CYP2E1 produces oxidative stress in a mouse model of chemically induced liver cancer. Toxicol Sci. 2015 Apr;144:393-405. [CrossRef]

- Calle, E.E.; Rodriguez, C.; Walker-Thurmond, K.; Thun, M.J. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskaran, K.; Douglas, I.; Forbes, H.; dos-Santos-Silva, I.; Leon, D.A.; Smeeth, L. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5.24 million UK adults. Lancet 2014, 384, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świątkiewicz, I.; Wróblewski, M.; Nuszkiewicz, J.; Sutkowy, P.; Wróblewska, J.; Woźniak, A. The Role of Oxidative Stress Enhanced by Adiposity in Cardiometabolic Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.M. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: structural and functional differences. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setiawan, V.W.; Lim, U.; Lipworth, L.; Lu, S.C.; Shepherd, J.; Ernst, T.; Wilkens, L.R.; Henderson, B.E.; Le Marchand, L. Sex and ethnic differences in the association of obesity with risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Jung, H.S.; Cho, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yun, K.E.; Lazo, M.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Ahn, J.; Kim, C.W.; Rampal, S.; et al. Metabolically healthy obesity and the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedland, E.S. Roles of critical visceral adipose tissue threshold in metabolic syndrome: implications for controlling dietary carbohydrates: a review. Nutr. Metab. 2004, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björntorp, P. Endocrine abnormalities in obesity. Metabolism. 1995, 44(9 Suppl. 3), 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Gu, D.; Wu, X.; Reynolds, K.; Duan, X.; Yao, C.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.S.; Chen, J.; Wildman, R.P.; Klag, M.J.; Whelton, PK. Major causes of death among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2005, 353, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, G.F.; Potosky, A.L.; Lubitz, J.D.; Kessler, L.G. Medicare payments from diagnosis to death for elderly cancer patients by stage at diagnosis. Med Care. 1995, 33, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, S.; Murata, M.; Kawanishi, S. DNA damage induced by hypochlorite and hypobromite with reference to inflammation-associated carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett,.

- Kiyohara, C.; Yoshimasu, K.; Takayama, K. , Nakanishi, Y. NQO1, MPO, and the risk of lung cancer: a HuGE review. Genet Med. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Choi, Y.; Hwangbo, B.; Lee, J.S. Combined effects of genetic polymorphisms in six selected genes on lung cancer susceptibility. Lung Cancer. 2007, 57, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Ambrosone, C.B.; Hong, C.C.; Ahn, J.; Rodriguez, C.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E. ; Relationships between polymorphisms in NOS3 and MPO genes, cigarette smoking and risk of post-menopausal breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007, 28, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenport, M.; Eom, H.; Uezu, M.; Schneller, J.; Gupta, R.; Mustafa, Y.; Villanueva, R.; Straus, E.W.; Raffaniello, R.D. Association of polymorphisms in myeloperoxidase and catalase genes with precancerous changes in the gastric mucosa of patients at inner-city hospitals in New York. Oncol Rep. 2007, 18, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascorbi, I. ; Henning S, Brockmöller J, Gephart J, Meisel C, Müller JM, Loddenkemper R, Roots I. Substantially reduced risk of cancer of the aerodigestive tract in subjects with variant--463A of the myeloperoxidase gene. Cancer Res.

- Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Wang, M.L.; Zhu, H.F.; Huang, X.E. The myeloperoxidase-463 G>A polymorphism influences risk of colorectal cancer in southern China: a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011, 12, 1789–1793. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Otero Regino, W.; Velasco, H.; Sandoval, H. The protective role of bilirubin in human beings. Rev. Colomb. Gastroenterol. 2009, 24, 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, K.H.; Wallner, M.; Molzer, C.; Gazzin, S.; Bulmer, A.C.; Tiribelli, C.; Vitek, L. Looking to the horizon: The role of bilirubin in the development and prevention of age-related chronic diseases. Clin. Sci. 2015, 129, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlak, T.W.; Saleh, M.; Higginson, D.S.; Paul, B.D.; Juluri, K.R.; Snyder, S.H. Bilirubin and glutathione have complementary antioxidant and cytoprotective roles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5171–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.M.; Sola, S.; Brito, M.A.; Brites, D.; Moura, J.J. Bilirubin directly disrupts membrane lipid polarity and fluidity, protein order, and redox status in rat mitochondria. J. Hepatol. 2002, 36, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.W.; Mathiesen, S.B.; Walaas, S.I. Bilirubin has widespread inhibitory effects on protein phosphorylation. Pediatr. Res. 1996, 39, 1072–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fevery, J. Bilirubin in clinical practice: A review. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Stud Liver 2008, 28, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, A.C.; Ried, K.; Coombes, J.S.; Blanchfield, J.T.; Toth, I.; Wagner, K.H. The anti-mutagenic and antioxidant effects of bile pigments in the Ames Salmonella test. Mutat. Res. 2007, 629, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molzer, C.; Huber, H.; Diem, K.; Wallner, M.; Bulmer, A.C.; Wagner, K.H. Extracellular and intracellular anti-mutagenic effects of bile pigments in the Salmonella typhimurium reverse mutation assay. Toxicol. Int. J. Public Assoc. BIBRA 2013, 27, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molzer, C.; Huber, H.; Steyrer, A.; Ziesel, G.; Ertl, A.; Plavotic, A.; Wallner, M.; Bulmer, A.C.; Wagner, K.H. In vitro antioxidant capacity and antigenotoxic properties of protoporphyrin and structurally related tetrapyrroles. Free Radic. Res. 2012, 46, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molzer, C.; Huber, H.; Steyrer, A.; Ziesel, G.V.; Wallner, M.; Hong, H.T.; Blanchfield, J.T.; Bulmer, A.C.; Wagner, K.H. Bilirubin and related tetrapyrroles inhibit food-borne mutagenesis: A mechanism for antigenotoxic action against a model epoxide. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1958–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyed Khoei, N.; Jenab, M.; Murphy, N.; Banbury, B.L.; Carreras-Torres, R.; Viallon, V.; Kühn, T.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, B.; Aleksandrova, K.; Cross, A.J.; et al. Circulating bilirubin levels and risk of colorectal cancer: Serological and Mendelian randomization analyses. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyed Khoei, N.; Anton, G.; Peters, A.; Freisling, H.; Wagner. K.H. The Association between Serum Bilirubin Levels and Colorectal Cancer Risk: Results from the Prospective Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) Study in Germany. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020, 9, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollinger, R.; Kogler, P.; Troppmair, J.; Hermann, M.; Wurm, M.; Drasche, A.; Konigsrainer, I.; Amberger, A.; Weiss, H.; Ofner, D.; et al. Bilirubin inhibits tumor cell growth via activation of ERK. Cell Cycle Georgetown Tex. 2007, 6, 3078–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavan, P.; Schwemberger, S.J.; Smith, D.L.; Babcock, G.F.; Zucker, S.D. Unconjugated bilirubin induces apoptosis in colon cancer cells by triggering mitochondrial depolarization. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 112, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.J.; Bell, D.A. Bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 gene polymorphisms: Susceptibility to oxidative damage and cancer? Mol. Carcinogen. 2000, 29, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Joubert, P.; Ansari-Pour, N.; Zhao, W.; Hoang, P.H.; Lokanga, R.; Moye, A.L.; Rosenbaum, J.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Martínez-Jiménez, F.; et al. Genomic and Evolutionary Classification of Lung Cancer in Never Smokers. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1348–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, E.; Nassar, A.H.; Abou Alaiwi, S.; Groha, S.; Akl, E.W.; Sholl, L.M.; Michael, K.S.; Awad, M.M.; Jänne, P.A.; Gusev, A.; et al. Variation in Targetable Genomic Alterations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Genetic Ancestry, Sex, Smoking History, and Histology. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasperino, J.; Rom, W.N. Gender and lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2004, 5, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 176. Thomas L, Doyle LA, Edelman MJ. 2005. Lung cancer in women: Emerging differences in epidemiology, biology, and therapy. Chest.

- Kiyohara, C.; Ohno, Y. Sex differences in lung cancer susceptibility: A review. Gend Med 2010, 7, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henschke, C.I.; Yip, R.; Miettinen, O.S. Women’s susceptibility to tobacco carcinogens and survival after diagnosis of lung cancer. JAMA 2006, 296, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parajuli R, Bjerkaas E, Tverdal A, Selmer R, Le Marchand L, Weiderpass E, Gram IT. 2013. The increased risk of colon cancer due to cigarette smoking may be greater in women than men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22:862–871.

- Forder, A.; Zhuang, R.; Souza, V.G.P.; Brockley, L.J.; Pewarchuk, M.E.; Telkar, N.; Stewart, G.L.; Benard, K.; Marshall, E.A.; Reis, P.P.; et al. Mechanisms Contributing to the Comorbidity of COPD and Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewhirst, M.W.; Cao, Y.; Moeller, B. Cycling Hypoxia and Free Radicals Regulate Angiogenesis and Radiotherapy Response. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covey, T.M.; Edes, K.; Coombs, G.S.; Virshup, D.M.; Fitzpatrick, F.A. Alkylation of the Tumor Suppressor PTEN Activates Akt and β-Catenin Signaling: A Mechanism Linking Inflammation and Oxidative Stress with Cancer. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Xu, D.; Li, J. Cigarette Smoke Extract Amplifies NADPH Oxidase-Dependent ROS Production to Inactivate PTEN by Oxidation in BEAS-2B Cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2021, 150, 112050. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.D.; Shastri, M.D.; Jha, N.K.; Gupta, G.; Chellappan, D.K.; Bagade, T.; Dua, K. Female Gender as a Risk Factor for Developing COPD. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 1290–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zaken Cohen, S.; Paré, P.D.; Man, S.F.P.; Sin, D.D. The Growing Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Lung Cancer in Women: Examining Sex Differences in Cigarette Smoke Metabolism. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 176, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, S.I.; Esteves, G.H.; Hirata, R.J.; Peri, S.; Devarajan, K.; Slifker, M.; Mosier, S.L.; Peng, J.; Vadhanam, M.V.; Hurst, H.E.; et al. Early Changes in Gene Expression Induced by Tobacco Smoke: Evidence for the Importance of Estrogen within Lung Tissue. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010, 3, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollerup, S.; Ryberg, D.; Hewer, A.; Phillips, D.H.; Haugen, A. Sex Differences in Lung CYP1A1 Expression and DNA Adduct Levels among Lung Cancer Patients. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 3317–3320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Winkle, L.S.; Gunderson, A.D.; Shimizu, J.A.; Baker, G.L.; Brown, C.D. Gender Differences in Naphthalene Metabolism and Naphthalene-Induced Acute Lung Injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2002, 282, L1122–L1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, J.B.; Kendrick, P.J.; Paulson, K.R.; Gupta, V.; Abrams, E.M.; Adedoyin, R.A.; Adhikari, T.B.; Advani, S.M.; Agrawal, A.; Ahmadian, E.; et al. Prevalence and Attributable Health Burden of Chronic Respiratory Diseases, 1990-2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Venegas, A.; Sansores, R.H.; Pérez-Padilla, R.; Regalado, J.; Velázquez, A.; Sánchez, C.; Mayar, M.E. Survival of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Due to Biomass Smoke and Tobacco. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 173, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, B.G.; Gibbs, G. Exposure-response relationship between lung cancer and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Occup Environ Med 2009, 66, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglia, F.; Matullo, G.; Vineis, P. Bulky DNA adducts and risk of cancer: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003, 12, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom, C.E.; Gerde, P.; Hanberg, A.; Jernstrom, B.; Johansson, C.; Kyrklund, T.; Rannug, A.; Tornqvist, M.; Victorin, K.; Westerholm, R. Cancer risk assessment, indicators, and guidelines for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air. Environ Health Perspect 2002, 110 (Suppl 3), 451–488. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Huang, K. , Zhang, X., Zhang, W.; Guan, L., Kuang, D., Deng, Q.; Deng, H., Zhang, X., He, M., Christiani, D., Wu, T. Women are more susceptible than men to oxidative stress and chromosome damage caused by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exposure. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2014, 55, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.; Naishadham, D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013, 63, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, C.M.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Soong, S.J.; Thompson, J.F. , Atkins, M.B.; Byrd, D.R.; Buzaid, A.C.; Cochran, A.J.; Coit, D.G.; Ding, S.; Eggermont, A.M.; et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27, 6199–6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, E.; Nijsten, T.E.; Visser, O.; Bastiaannet, E.; Van Hattem, S.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.; Coebergh, J.W. Superior survival of females among 10,538 Dutch melanoma patients is independent of Breslow thickness, histologic type and tumor site. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasithiotakis, K.; Leiter, U.; Meier, F.; Eigentler, T.; Metzler, G.; Moehrle, M.; Breuninger, H.; Garbe, C. Age and gender are significant independent predictors of survival in primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 2008, 112, 1795–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, B.; Price, A.; Wagner, M.; Williams, V.; Lorigan, P.; Browne, S.; Miller, J.G.; Mac Neil, S. Investigation of female survival benefit in metastatic melanoma. Br. J. Cancer 1999, 80, 2025–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemeny, M.M.; Busch, E.; Stewart, A.K.; Menck, H.R. Superior survival of young women with malignant melanoma. Am. J. Surg.

- Daryanani, D.; Plukker, J.T.; De Jong, M.A.; Haaxma-Reiche, H.; Nap, R.; Kuiper, H.; Hoekstra, H.J. Increased incidence of brain metastases in cutaneous head and neck melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2005, 15, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoggins, C.R.; Ross, M.I.; Reintgen, D.S.; Noyes, R.D.; Goydos, J.S.; Beitsch, P.D.; Urist, M.M.; Ariyan, S.; Sussman, J.J.; Edwards, M.J. , Chagpar, A.B.; Martin, R.C.; Stromberg, A.J.; Hagendoorn, L.; McMasters, K.M.; Sunbelt Melanoma Trial. Gender-related differences in outcome for melanoma patients. Ann Surg. 2006, 243, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joosse, A.; Collette, S.; Suciu, S.; Nijsten, T.; Lejeune, F.; Kleeberg, U.R.; Coebergh, J.W.; Eggermont, A.M.; de Vries, E. Superior outcome of women with stage I/II cutaneous melanoma: pooled analysis of four European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer phase III trials. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30, 2240–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosse, A.; de Vries, E.; Eckel, R.; Nijsten, T.; Eggermont, A.M.; Hölzel, D.; Coebergh, J.W.; Engel, J. ; Munich Melanoma Group. Gender differences in melanoma survival: female patients have a decreased risk of metastasis. J Invest Dermatol. [CrossRef]

- Sondak, V.K.; Swetter, S.M.; Berwick, M.A. Gender disparities in patients with melanoma: breaking the glass ceiling. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30, 2177–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, C.S.; Clarke, C.A.; Keegan, T.H.; Tao, L.; Swetter, S.M. Melanoma survival disadvantage in young, non-Hispanic white males compared with females. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruehauf, J.P.; Trapp, V. Reactive oxygen species: an Achilles’ heel of melanoma? Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2008, 8, 1751–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavò, S.P.; Tonacci, A.; Bertino, L.; Casciaro, M.; Borgia, F.; Gangemi, S. The role of oxidative stress in the biology of melanoma: A systematic review. Pathol Res Pract. 2019, 215, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittinger, F.; Gonzalez-Garcia, J.L.; Klein, C.L.; Brochhausen, C.; Offner, F.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. Production of superoxide by human malignant melanoma cells. Melanoma Res.

- Meyskens, F.L. Jr.; Chau, H.V.; Tohidian, N.; Buckmeier, J. Luminol-enhanced chemiluminescent response of human melanocytes and melanoma cells to hydrogen peroxide stress. Pigment Cell Res. 1997, 10, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosse, A.; De Vries, E.; van Eijck, C.H.; Eggermont, A.M.; Nijsten, T.; Coebergh, J.W. Reactive oxygen species and melanoma: an explanation for gender differences in survival? Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010, 23, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, C.S.; Hamm, F.; Elsner, P.; Thiele, J.J. Oxidative stress in malignant melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2003, 148, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyskens, F.L. Jr.; McNulty, S.E. , Buckmeier, J.A.; Tohidian, N.B.; Spillane, T.J.; Kahlon, R.S., Gonzalez, R.I. Aberrant redox regulation in human metastatic melanoma cells compared to normal melanocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001, 31, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, M. Reactive oxygen species in tumor metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2008, 266, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trouba, K.J.; Hamadeh, H.K.; Amin, R.P.; Germolec, D.R. Oxidative stress and its role in skin disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002, 4, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Ahner, J.M.; Wulff, B.C.; Tober, K.L.; Kusewitt, D.F.; Riggenbach, J.A.; Oberyszyn, T.M. Gender differences in UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis, inflammation, and DNA damage. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 3468–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.Y.; Lin, B.; Chen, Y.T.; Huang, Y.P.; Feng, W.P.; Wu, Y.; Long, G.H. , Zou, Y.N.; Liu, Y.; Lin, B.Q.; Sang, N.L.; Zhan, J.Y. Gender differences in UV-induced skin inflammation, skin carcinogenesis and systemic damage. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masback, A. : Olsson, H.; Westerdahl, J.; Ingvar, C.; Jonsson, N. Prognostic factors in invasive cutaneous malignant melanoma: a population-based study and review. Melanoma Res.

- Borrás, C.; Gambini, J.; López-Grueso, R.; Pallardó, F.V.; Viña, J. Direct antioxidant and protective effect of estradiol on isolated mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010, 1802, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield-Lillico, A.J.; Reid, M.E.; Turnbull, B.W.; Combs, G.F. Jr.; Slate, E.H.; Fischbach, L.A.; Marshall, J.R.; Clark, L.C. Baseline characteristics and the effect of selenium supplementation on cancer incidence in a randomized clinical trial: a summary report of the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2002, 11, 630–639. [Google Scholar]

- Hercberg, S.; Ezzedine, K.; Guinot, C.; Preziosi, P.; Galan, P.; Bertrais, S.; Estaquio, C.; Briançon, S.; Favier, A.; Latreille, J.; Malvy, D. Antioxidant supplementation increases the risk of skin cancers in women but not in men. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2098–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Preziosi, P.; Bertrais, S.; Mennen, L.; Malvy, D.; Roussel, A.M.; Favier, A.; Briancon, S. The SU.VI.MAX Study: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the health effects of antioxidant vitamins and minerals. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 2335–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radkiewicz, C.; Bruchfeld, J.B.; Weibull, C.E.; Jeppesen, M.L.; Frederiksen, H.; Lambe, M.; Jakobsen, L.; El-Galaly, T.C.; Smedby, K.E.; Wästerlid, T. Sex differences in lymphoma incidence and mortality by subtype: A population-based study. Am J Hematol. 2023, 98, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobus, J.A.; Duda, C.G.; Coleman, M.C.; Martin, S.M.; Mapuskar, K.; Mao, G.; Smith, B.J.; Aykin-Burns, N.; Guida, P. , Gius, D.; Domann, F.E.; Knudson, C.M.; Spitz, D.R. Low-dose radiation-induced enhancement of thymic lymphomagenesis in Lck-Bax mice is dependent on LET and gender. Radiat Res. 2013, 180, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Štěrba, M.; Popelová, O.; Vávrová, A. , Jirkovský, E.; Kovaříková, P.; Geršl, V.; Šimůnek, T. Oxidative stress, redox signaling, and metal chelation in anthracycline cardiotoxicity and pharmacological cardioprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal, /: 899–929. https, 1089. [Google Scholar]

- Malorni, W.; Campesi, I.; Straface, E.; Vella, S.; Franconi, F. Redox features of the cell: a gender perspective. Antioxid Redox Signal 2007, 9, 1779–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijay, V.; Han, T.; Moland, C.L.; Kwekel, J.C.; Fuscoe, J.C.; Desai, V.G. (2015) Sexual dimorphism in the expression of mitochondriarelated genes in rat heart at different ages. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0117047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, N.A.; Twelves, C.J.; Gillies, H.; James, C.A. , Harper, P.G., Rubens, R.D. (1995) Gender affects the doxorubicin pharmacokinetics in patients with normal liver biochemistry. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 36, 473–476. [CrossRef]

- Wade, J.R.; Kelman, A.W.; Kerr, D.J.; Robert, J.; Whiting, B. Variability in the pharmacokinetics of epirubicin: a population analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1992, 29, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varricchi, G.; Ameri, P.; Cadeddu, C.; Ghigo, A.; Madonna, R.; Marone, G.; Mercurio, V. , Monte, I.; Novo, G.; Parrella, P.; Pirozzi, F.; Pecoraro, A., Spallarossa, P.; Zito, C.; Mercuro, G.; Pagliaro, P.; Tocchetti, C.G. Antineoplastic drug-induced cardiotoxicity: a redox perspective. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 167. 9,. [CrossRef]

- Tocchetti, C.G.; Cadeddu, C.; Di Lisi, D.; Femminò, S.; Madonna, R.; Mele, D.; Monte, I.; Novo, G.; Penna, C.; Pepe, A.; Spallarossa, P.; Varricchi, G.; Zito, C.; Pagliaro, P.; Mercuro, G. From molecular mechanisms to clinical management of antineoplastic drug-induced cardiovascular toxicity: a translational overview. Antioxid Redox Signal 2019, 30, 2110–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupo, M.; Pisano, A.; Abonante, S.; Maggiolini, M.; Musti, A.M. GPER activates Notch signaling in breast cancer cells and cancerassociated fibroblasts (CAFs). Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2014, 46, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubecka, K.; Kurzava, L.; Flower, K.; Buvala, H.; Zhang, H.; Teegarden, D.; Camarillo, I.; Suderman, M.; Kuang, S. , Andrisani, O.; Flanagan, J.M.; Stefanska, B. (2016) Stilbenoids remodel the DNA methylation patterns in breast cancer cells and inhibit oncogenic NOTCH signaling through epigenetic regulation of MAML2 transcriptional activity. Carcinogenesis. 37, 656–668. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, Y.; Pokrzywinski, K.L.; Rosen, E.T.; Mog, S.; Aryal, B.; Chehab, L.M.; Vijay, V.; Moland, C.L.; Desai, V.G.; Dickey, J.S.; Rao, V.A. Reproductive hormone levels and differential mitochondria-related oxidative gene expression as potential mechanisms for gender differences in cardiosensitivity to doxorubicin in tumor-bearing spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2015, 76, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Octavia, Y.T.C.; Gabrielson, K.L.; Janssens, S.; Crijns, H.J.; Moens, A.L. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2012, 52, 1213–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, F.S.; Burgeiro, A.; Garcia, R.; Moreno, A.J.; Carvalho, R.A.; Oliveira, P.J. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: from bioenergetic failure and cell death to cardiomyopathy. Med Res Rev 2014, 34, 106–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, S.; Autschbach, R. Doxorubicin in experimental and clinical heart failure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Marfatia, R.; Tannenbaum, S.; Yang, C.; Avelar, E. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy 17 years after chemotherapy. Texas Heart Inst J 2012, 39, 424–427. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova, K.R.; DeGroot, K.; Myers, A.K.; Kim, Y.D. Estrogen and homocysteine. Cardiovasc Res 2002, 53, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogita, H.; Node, K.; Kitakaze, M. The role of estrogen and estrogen-related drugs in cardiovascular diseases. Curr Drug Metab. 2003, 4, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershman, D.L.; McBride, R.B.; Eisenberger, A.; Tsai, W.Y.; Grann, V.R.; Jacobson, J.S. Doxorubicin, cardiac risk factors, and cardiac toxicity in elderly patients with diffuse B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26, 3159–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancaniello, T.; Meyer, R.A.; Wong, K.Y.; Sager, C.; Kaplan, S. (1980) Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in children. J Pediatr 1980, 97, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.R.; Bernasochi, G.B.; Varma, U.; Raaijmakers, A.J.; Delbridge, L.M. Sex and sex hormones in cardiac stress—mechanistic insights. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2012, 137, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Knapton, A.; Lipshultz, S.E.; Cochran, T.R.; Hiraragi, H.; Herman, E.H. Sex-related differences in mast cell activity and doxorubicin toxicity: a study in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Toxicol Pathol 2014, 42, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belham, M.; Kruger, A.; Mepham, S.; Faganello, G.; Pritchard, C. Monitoring left ventricular function in adults receiving anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. Eur J Heart Fail 2007, 9, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.Y.T.F.; Tsai, C.H.; Huang, C.Y. (2011) Mechanisms governing the protective effect of 17B-estradiol and estrogen receptors against cardiomyocyte injury. BioMedicine 2011, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), Assessing Dose of the Representative Person for the Purpose of Radiation Protection of the Public and the Optimisation of Radiological Protection: Broadening the Process. ICRP Publication 101. Ann. ICRP 36.

- International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), Adult Reference Computational Phantoms. ICRP Publication 110. Ann. ICRP 39 2009.

- Langen, B.; Vorontsov, E.; Spetz, J.; Swanpalmer, J.; Sihlbom, C.; Helou, K.; Forssell-Aronsson, E. Age and sex effects across the blood proteome after ionizing radiation exposure can bias biomarker screening and risk assessment. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyapour, R.; Motevaseli, E.; Rezaeyan, A.; Abdollahi, H.; Farhood, B.; Cheki, M.; Najafi, M.; Villa, V. Mechanisms of Radiation Bystander and Non-Targeted Effects: Implications to Radiation Carcinogenesis and Radiotherapy. Curr Radiopharm. 2018, 11, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizard, A.; Boutou, O.; Pottier, D.; Troussard, X.; Pheby, D.; Launoy, G.; Slama, R.; Spira, A. The incidence of childhood leukaemia around the La Hague nuclear waste reprocessing plant (France): a survey for the years 1978-1998. J. Epidemiol. Comm. health,.

- Yoshida, K.; Nemoto, K.; Nishimura, M.; Seki, M. Exacerbating factors of radiation-induced myeloid leukemogenesis. Leukemia Res,.

- Kovalchuk, O.; Burke, P.; Besplug, J.; Slovack, M.; Filkowski, J.; Pogribny, I. Methylation changes in muscle and liver tissues of male and female mice exposed to acute and chronic low-dose Xray-irradiation. Mutat. Res.

- Koturbash, I.; Zemp, F.; Kolb, B.; Kovalchuk, O. Sex-specific radiation-induced microRNAome responses in the hippocampus, cerebellum and frontal cortex in a mouse model. Mutat. Res,.

- Koturbash, I.; Kutanzi, K.; Hendrickson, K.; Rodriguez-Juarez, R.; Kogosov, D.; Kovalchuk, O. Radiation-induced bystander effects in vivo are sex specific. Mutat. Res,.

- Koturbash, I.; Zemp, F.J.; Kutanzi, K.; Luzhna, L.; Loree, J.; Kolb, B.; Kovalchuk, O. Sex-specific microRNAome deregulation in the shielded bystander spleen of cranially exposed mice. Cell Cycle, 1658; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y.; Calaf, G.M.; Zhou, H.; Ghandhi, S.A.; Elliston, C.D.; Wen, G.; Nohmi, T.; Amundson, S.A.; Hei, T.K. Radiation induced COX-2 expression and mutagenesis at non-targeted lung tissues of gpt delta transgenic mice. Br. J. Cancer,.

- Cheng, C.; Omura Minamisawa, M.; Kang, Y.; Hara, T.; Koike, I.; Inoue, T. Quantification of circulating cellfree DNA in the plasma of cancer patients during radiation therapy. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Rong, S.; Qu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, D.; Pan, H.; Wang, W. Relation between gastric cancer and protein oxidation, DNA damage, and lipid peroxidation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deligezer, U.; Eralp, Y.; Akisik, E.Z.; Akisik, E.E.; Saip, P.; Topuz, E.; Dalay, N. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on integrity of free serum DNA in patients with breast cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad Sci. 2008, 1137, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, S.; Shao, L.L.; Yin, J.C.; Wu, X.; Shao, Y.W.; Yuan, S.; Yu, J. Developing more sensitive genomic approaches to detect radioresponse in precision radiation oncology: From tissue DNA analysis to circulating tumor DNA. Cancer Lett. 2020, 472, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, A.G.; Mannino, F.; Innao, V.; Musolino, C.; Allegra, A. Radioprotective Agents and Enhancers Factors. Preventive and Therapeutic Strategies for Oxidative Induced Radiotherapy Damages in Hematological Malignancies. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020, 9, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegra, A.; Tonacci, A.; Pioggia, G.; Musolino, C.; Gangemi, S. Anticancer Activity of Rosmarinus officinalis L.: Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Potentials. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegra, A.; Speciale, A.; Molonia, M.S.; Guglielmo, L.; Musolino, C.; Ferlazzo, G.; Costa, G.; Saija, A.; Cimino, F. Curcumin ameliorates the in vitro efficacy of carfilzomib in human multiple myeloma U266 cells targeting p53 and NF-κB pathways. Toxicol In Vitro. 2018, 47, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristani, M.; Speciale, A.; Saija, A.; Gangemi, S.; Minciullo, P.L.; Cimino, F. Circulating Advanced Oxidation Protein Products as Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and Progression Mediators in Pathological Conditions Related to Inflammation and Immune Dysregulation. Curr Med Chem. 2016, 23, 3862–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y. Oxidative stress and gender disparity in cancer. Free Radic Res. 2022, 56, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R.C. Gender, immunity and the regulation of longevity. Bioessays 2007, 29, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malorni, W.; Straface, E.; Matarrese, P.; Ascione, B.; Coinu, R.; Canu, S.; Galluzzo, P.; Marino, M.; Franconi, F. Redox state and gender differences in vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vina, J.; Sastre, J.; Pallardo, F.; Borras, C. Mitochondrial theory of aging: importance to explain why females live longer than males. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2003, 5, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loft, S.; Vistisen, K.; Ewertz, M.; Tjonneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Poulsen, H.E. Oxidative DNA damage estimated by 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine excretion in humans: influence of smoking, gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis 1992, 13, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marnett, L.J. Oxyradicals and DNA damage. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokov, A.F.; Ko, D.; Richardson, A. The effect of gonadectomy and estradiol on sensitivity to oxidative stress. Endocr. Res. 2009, 34, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Valencia, C.A.; Zhang, J.; Lee, N.C.; Slone, J.; Gui, B.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Dell, S.; Brown, J.; Chen, S.M.; Chien, Y.H.; Hwu, W.L.; Fan, P.C.; Wong, L.J.; Atwal, P.S.; Huang, T. Biparental inheritance of mitochondrial DNA in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018, 115, 13039–13044, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rius, R.; Cowley, M.J.; Riley, L.; Puttick, C.; Thorburn, D.R.; Christodoulou, J. Biparental inheritance of mitochondrial DNA in humans is not a common phenomenon. Genet Med 2019, 21, 2823–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz-Bonengel, S.; Parson, W. No further evidence for paternal leakage of mitochondrial DNA in humans yet. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019, 116, 1821–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaignard, P.; Liere, P.; Thérond, P.; Schumacher, M.; Slama, A.; Guennoun, R. Role of sex hormones on brain mitochondrial function, with special reference to aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2017, 9, 406, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Clapier, R.; Moulin, M.; Piquereau, J.; Lemaire, C.; Mericskay, M.; Veksler, V.; Garnier, A. Mitochondria: a central target for sex differences in pathologies. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017, 131, 803–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Higher risk | Mechanism | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glioma | men | Testosterone has neurotoxic effects | [97] |

| Liver cancer | men | Low levels of alcohol-dehydrogenase | [111] |

| Colorectal cancer | women | Low levels of unconjugated bilirubin which has antioxidant effects | [163] |

| Lung cancer | smokimg women | High levels of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 that activate tobacco smoke components to create ROS | [184] |

| Melanoma | men | Low levels of antioxidant enzymes in the skin | [215] |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | men | High levels of superoxide in thymocytes overexpressing Bax | [223] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).