1. Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive form of interstitial lung disease of unknown etiology characterized by progressive fibrosis and worsening lung function [

1,

2]. Although the disease course varies, IPF is usually progressive in cases of irreversible pulmonary fibrosis [

3,

4]. Several lines of evidence have suggested that genetic and epigenetic mechanisms play roles in the development and prognosis of IPF [

5]. Global gene expression studies have identified several novel genes in lung tissues from IPF patients [6-9]. We also revealed that 178 of 15,020 genes are differentially expressed in lung fibroblasts from IPF patients compared with those from controls [

10]. Among them, the mRNA level of Erythrocyte Membrane Protein Band 4.1-like 3 (

EPB41L3) was 14-fold higher in IPF patients than controls.

EPB41L3 (also called

DAL-1/4.1B) is on 18p11.31 and is believed to enable cytoskeletal protein-membrane anchor activity, cytoskeletal rearrangements, intracellular transport, and signal transduction [

11].

EPB41L3 inhibits the progression and development of several cancers, including lung adenocarcinoma, meningioma, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer [

11]. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition (FMT) are involved in the development and progression of cancer [

12]. Multiple signaling pathways play roles in the EMT and FMT [

11]. The extracellular matrix (ECM) is degraded during the late stages of the EMT by increased expression of proteases, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which play a crucial role in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis [

13].

Several studies have revealed the involvement of

EPB41L3 in the EMT and FMT. Transforming growth factor

(TGF)-β increased mRNA and protein expression of EPB41L3 by the A549 cell line, and deleting

EPB41L3 attenuated the TGF-β-induced EMT in a lung cancer cell line [

14]. In addition, EPB41L3 suppressed tumor cell invasion, and inhibited MMP2 and MMP9 expression in an esophageal squamous cancer cell line [

15]. Most studies have focused on cancer. However, few have been conducted on pulmonary fibrosis.

TGF-β1 expression is particularly high in fibrotic areas of the lungs of patients with IPF, and activated

TGF-β1 drives ECM components, such as

COL1A1 (collagen 1), FN1 (fibronectin) and

ACTA2 (

α-SMA), to generate a profibrotic environment in the injured area [16-20]. Therefore, regulating

TGF-β1 activity with

EPB41L3 is a potential therapeutic strategy for fibrosis in patients with IPF. In the present study, the role of

EPB41L3 was investigated by comparing mRNA and protein expression between lung fibroblasts derived from patients with IPF and those of controls, and by regulating the EMT of an epithelial cell line (A549) and FMT of a fibroblast cell line (MRC5) by overexpressing and silencing

EPB41L3.

2. Results

2.1. Comparison of mRNA and Protein Expression of EPB41L3 by Fibroblasts in IPF and Control Groups

To validate the enhancement of

EPB41L3 mRNA expression by fibroblasts in our previous transcriptome chip study [

10],

EPB41L3 mRNA and protein were measured using cultured primary fibroblasts obtained from lung tissues of IPF patients (n = 14) and those of controls (n = 10). Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) revealed 168 base pair-sized

EPB41L3 bands in IPF and control fibroblasts (

Figure 1A). Densitometry revealed that mRNA

EPB41L3 expression normalized to that of

β-actin was 2-fold higher in IPF than control fibroblasts [0.83 (0.67–0.89) vs. 0.46 (0.37–0.52), p < 0.001; (

Figure 1B)]. Real-time PCR also revealed 8-fold higher mRNA levels of

EPB41L3 normalized to those of

β-actin in IPF than control fibroblasts [10.59 (8.79–23.34) vs. 1.29 (0.61–1.86), p < 0.001; (

Figure 1C)]. Western blotting revealed that the levels of EPB41L3 normalized to those of β-actin were 9-fold higher in IPF than control fibroblasts [0.93 (0.75–1.15) vs. 0 (0–0.09), p < 0.001;

Figure 1D,E)]. Additionally, a positive correlation was detected between mRNA and protein EPB41L3 levels in 24 fibroblasts (r = 0.504, p = 0.012,

Figure 1F).

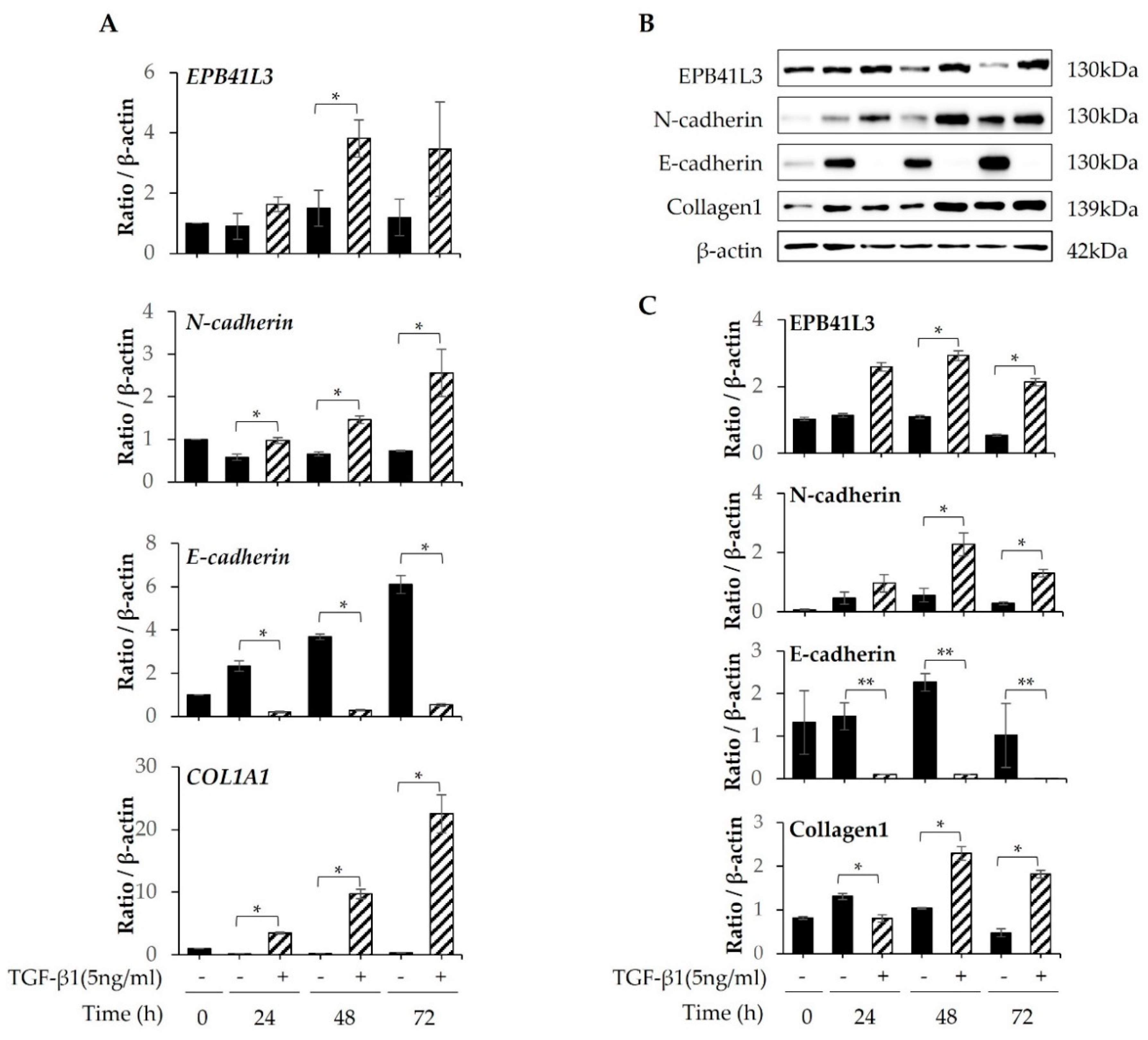

2.2. Changes in mRNA and Protein Expression of EPB41L3 and EMT-Related Genes by A549 Cells after Stimulation with TGF-β1

After A549 cells were cultured in tissue culture medium (TCM) containing 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24, 48, and 72 h,

EPB41L3, N-cadherin, E-cadherin, COL1A1, and

β-actin were quantified using real-time PCR. A 2-fold increase in the

EPB41L3 to

β-actin mRNA ratio was observed after stimulation with TGF-β1 in a time-dependent manner. Moreover, the

COL1A1 and

N-cadherin to β-actin mRNA expression ratios were 10- and 3-fold higher, respectively. In contrast, the

E-cadherin to β-actin mRNA expression ratio decreased significantly after stimulation with TGF-β1 in a time-dependent manner (

Figure 2A). Western blot demonstrated similar changes in protein expression (

Figure 2B). The EPB41L3, N-cadherin, and collagen 1 to β-actin protein expression ratios increased significantly after stimulation with TGF-β1 in a time-dependent manner, while the E-cadherin to β-actin ratio decreased significantly (

Figure 2C).

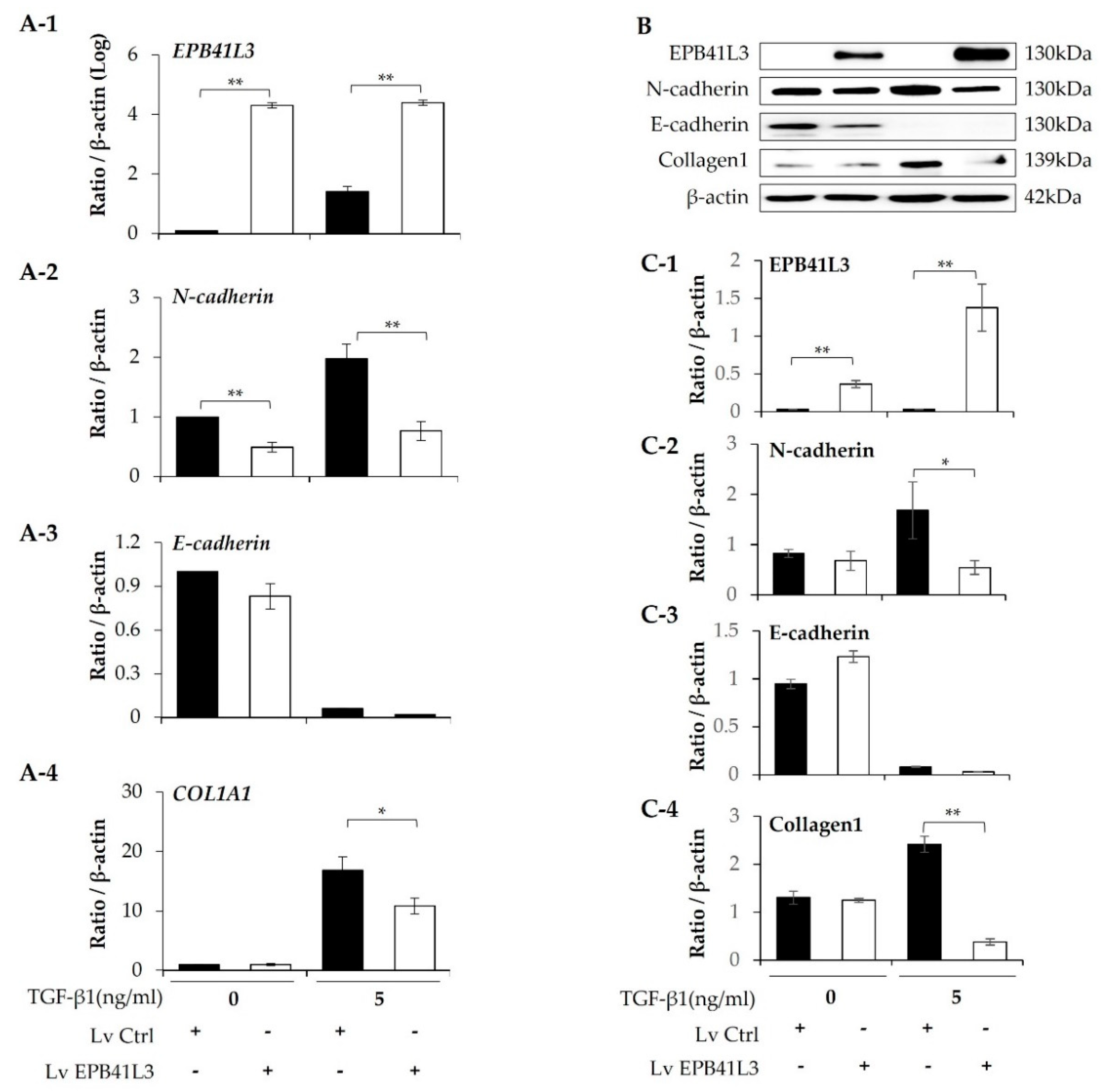

2.3. Effect of Overexpressing EPB41L3 on the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in A549 Cells

A549 cells were transfected with lenti-

EPB41L3 or the control lentiviral vector. The mRNA levels of

EPB41L3 (normalized to

β-actin) measured using real-time PCR increased 48 h after transfection of lenti-

EPB41L3 compared with those of the lentiviral vectors in the absence (4-fold) and presence (3-fold) of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 (

Figure 3A-1). Concomitantly, 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 increased

N-cadherin and

COL1A1 mRNA levels, which were significantly downregulated by transfected lenti-

EPB41L3 (

Figure 3A-2,A-4).

E-cadherin mRNA tended to be decreased by lenti-

EPB41L3 (

Figure 3A-3). Protein levels of these genes changed similarly on western blots (

Figure 3B): The protein level of EPB41L3 (normalized to the β-actin level) increased 48 h after transfection of lenti-

EPB41L3 in the absence (38-fold) and presence (26-fold) of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 (

Figure 3C-1). Additionally, 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 induced an increase in N-cadherin, and collagen 1, which were completely downregulated by

EPB41L3 transfection (

Figure 3C-2,C-4). E-cadherin was not changed by lenti-

EPB41L3 (

Figure 3C-3). These data indicate that overexpressing EPB41L3 inhibits the EMT induced by TGF-β1.

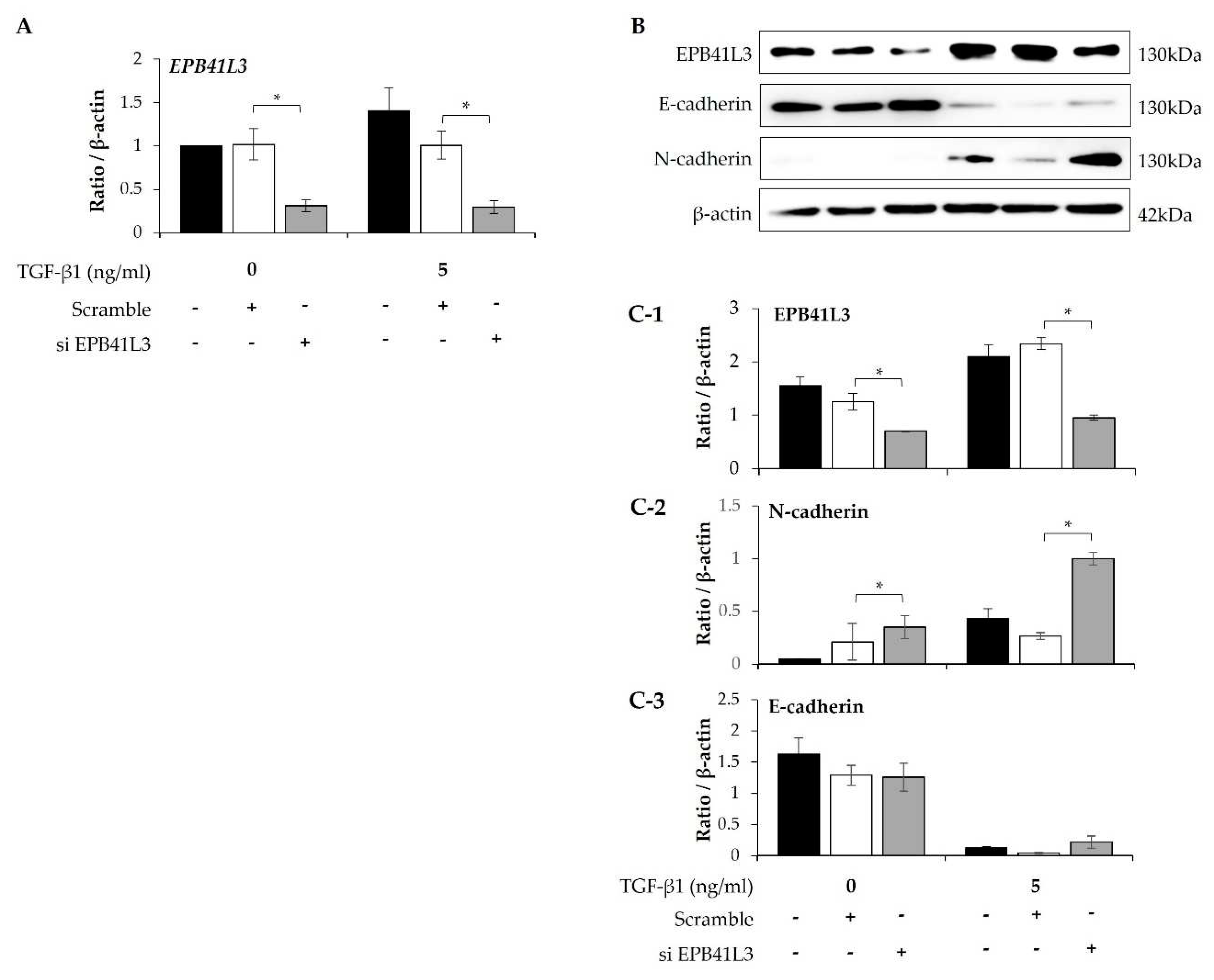

2.4. EPB41L3 Gene Silencing during the EMT of A549 Cells

Treatment with siRNA (100nM) for 48 h decreased the mRNA expression of

EPB41L3 (normalized to the

β-actin level) in the presence and absence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 (

Figure 4A). Concomitantly, EPB41L3 siRNA significantly decreased mRNA level of

EPB41L3 to the untreated level (

Figure 4A). Western blot revealed similar changes in the protein levels (

Figure 4B). The protein level of EPB41L3 was decreased significantly, while the N-cadherin to β-actin protein expression ratio increased significantly by

EPB41L3 siRNA in the absence or the presence with TGF-β1 (

Figure 4C-1,C-2), while the E-cadherin to β-actin ratio was not significantly changed (

Figure 4C-3).

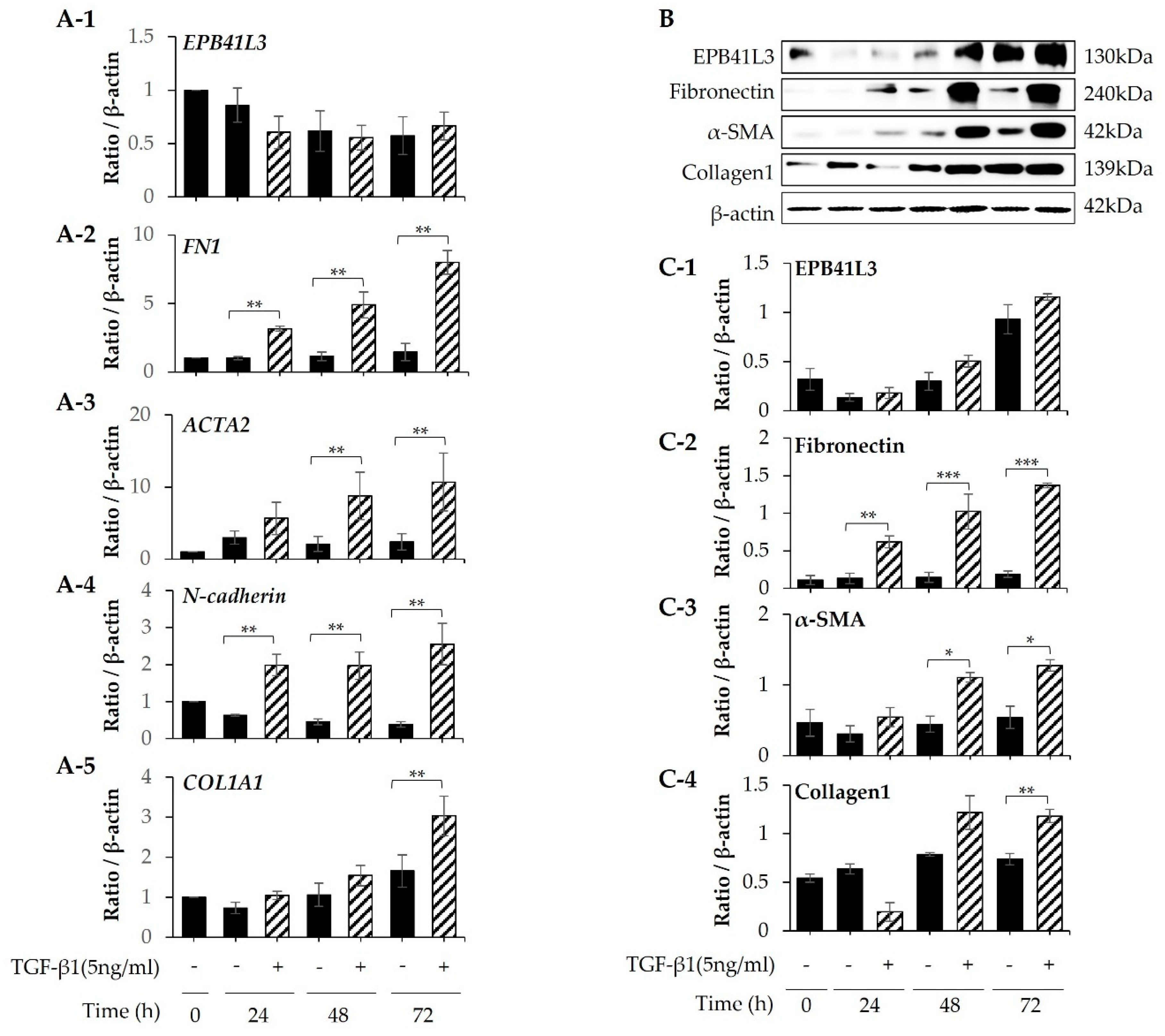

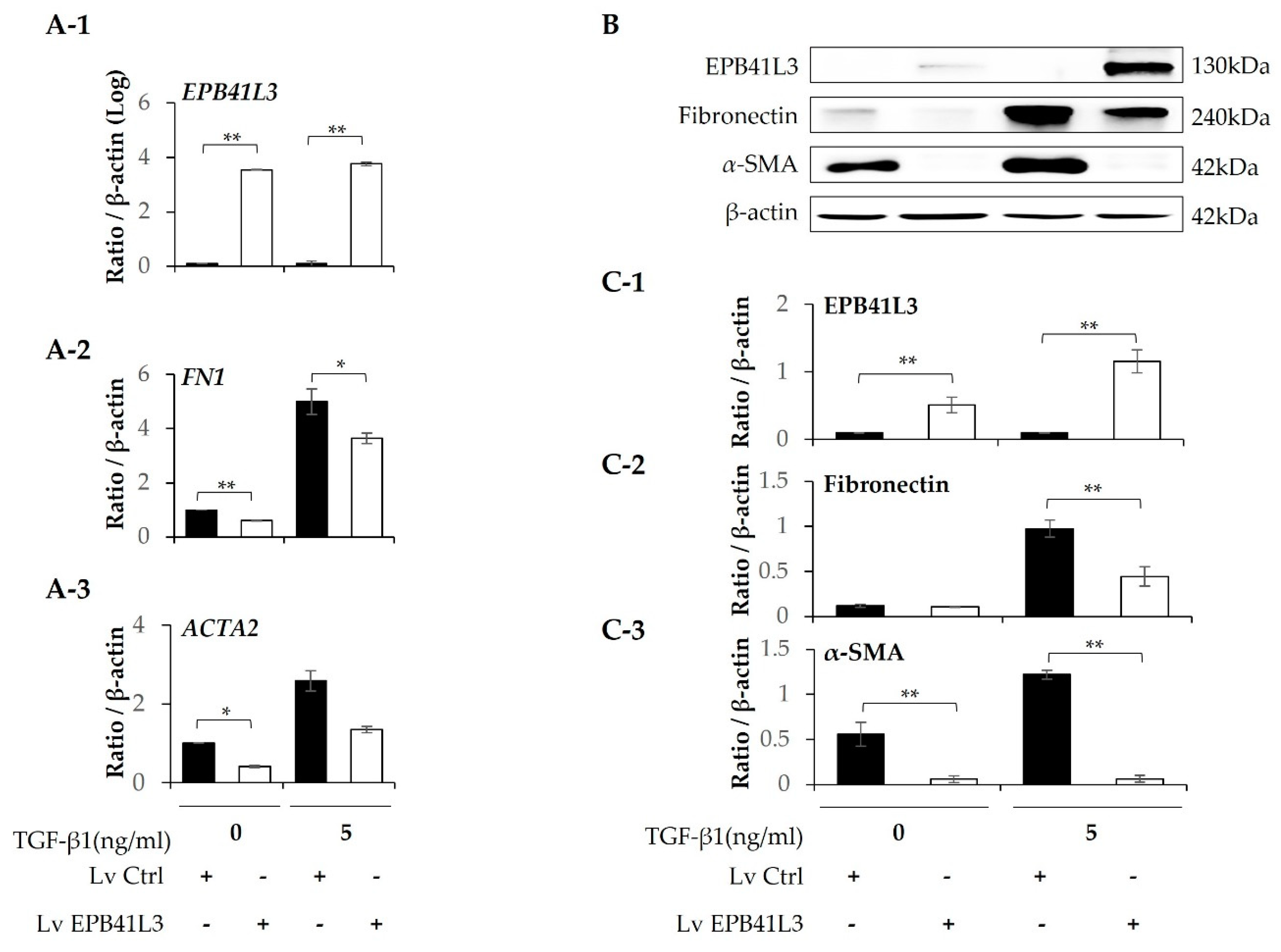

2.5. Effect of EPB41L3 Overexpression and Knockdown on the FMT in MRC5 Cells

Treatment with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 significantly increased the mRNA expression of

FN1, ACTA2,

N-cadherin and

COL1A1 (normalized to the

β-actin level) of MRC-5 cells in a time-dependent manner (

Figure 5A-2–A-5). The protein levels of these genes showed the same pattern of change (

Figure 5B). The protein expression of EPB41L3, fibronectin, α-SMA, and collagen 1 increased in a time-dependent manner (

Figure 5C-1–C-4). When

EPB41L3 was transfected into MRC5 cells with lenti-

EPB41L3, mRNA and protein expression of

EPB41L3 increased 48 h after transfection (

Figure 6A-1,C-1). Concomitantly, mRNA and protein expression of

FN1 (

Figure 6A-2,C-2) and

ACTA2 (

Figure 6A-3 and C-3) significantly decreased after transfection with lenti-

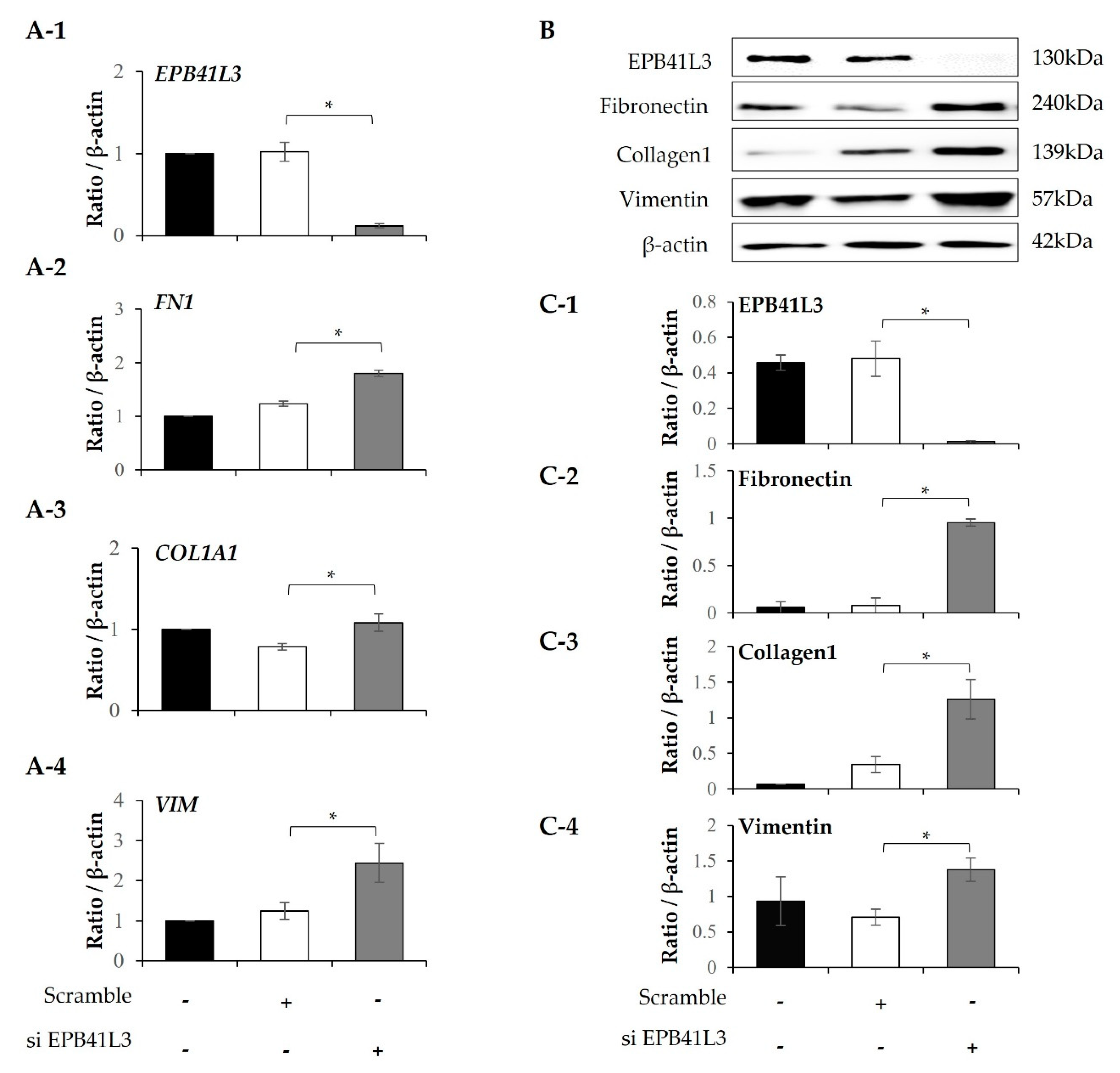

EPB41L3 in the absence and presence of TGF-β1. Treatment with EPB41L3 siRNA (100nM) for 48 h decreased

EPB41L3 mRNA expression normalized to the

β-actin level (

Figure 7A-1). Concomitantly,

FN1,

COL1A1, and

VIM mRNA levels were significantly up-regulated after treatment with

EPB41L3 siRNA (

Figure 7A-2–A-4). Western blot demonstrated the same findings that the protein level of EPB41L3 was significantly decreased (

Figure 7B,C-1), while the fibronectin, collagen 1, and vimentin to β-actin protein expression ratios were increased significantly by treatment with siEPB41L3 (

Figure 7C-2–C-4). These data indicate that EPB41L3 regulates the FMT.

3. Discussion

In the present study, protein and mRNA expression of the

EPB41L3 gene significantly increased in lung tissue-derived fibroblasts from IPF patients compared to those from controls. This result is in a good line with the transcriptomic datasets of single-cell RNA-seq demonstrating upregulation of

EPB41L3 in the lung fibroblasts of IPF patients [

21]. In A549 and MRC5, overexpression of

EPB41L3 suppressed the EMT - and FMT - related genes while

EPB41L3 knockdown upregulated these genes. These data show for the first time that the

EPB41L3 gene may play a role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis by regulating the EMT and FMT.

EPB41L3 has been regarded as a tumor suppressor that inhibits the progression and development of several types of cancer, including lung adenocarcinoma, meningioma, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer [

22,

23]. Loss of the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein leads to a substantial decrease in the expression of numerous EMT markers, including E-cadherin and β-catenin in lung cancer cell lines [

24], which agrees with our EPB41L3 knockdown data.

EPB41L3 maintains the epithelial cell phenotype and attenuates the EMT by inhibiting Snail and PI3K/Akt/Mdm2/p53 signaling [11,24-26]. In a study using 83 osteosarcoma tissues [

11], the expression of Snai1/Slug/Twist1 was correlated with that of EPB41L3. Thus,

EPB41L3 may inhibit progression of the EMT by interacting with

Snail1, 2 and

Twist1 in patients with pulmonary fibrosis.

The mechanism underlying the increase in

EPB41L3 in IPF has not been revealed. In our previous transcriptome analysis of 12 lung fibroblast samples derived from 4 controls and 8 IPF-patients (GSE71351), strong correlations were observed between the EPB41L3 levels and those of 344 among 15,020 genes (160 positive and 184 negative correlations) (

Table S1). Among them,

ZNF678, which is involved in transcriptional regulation, interacted with EPB41L3 in the STRING protein-protein interaction network analysis (

Figure S1). Among the 99 proteins interacting with ZNF687, 33 proteins including MYC [

27], CSNK2A1 [

28], CDKN2A [

29], HDAC2 [

30], MI1 [

31], SOX2 [

32], and RNF2 [

33] have been revealed to associate with fibrosis. These data indicate that EPB41L3 may be regulated through interactions with ZNF687 and interacting genes.

In addition, CpG methylation is a common mechanism of genetic downregulation. Hypermethylation of DAL-1 is strongly correlated with the loss of DAL-1 and predicts short overall survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

34]. Hypermethylation of CpG sites in the EPB41L3 promoter region leads to loss of expression, as observed in esophageal cancer [

35]. In our previous methylation study (GSE107226) using the same fibroblasts [

36], 21 CpG sites were identified on the

EPB41L3 gene (5 on TSS1500, 5 on TSS200, 9 on the 5′UTR, 1 on the body, and 1 on the 3′UTR) (

Figure S2 and

Table S2). Among them, different methylation levels were detected at 4 CpG sites (cg15528411, cg22335490, cg27082185, and cg14075742) in the fibroblasts of IPF patients compared with the controls. Significant positive correlations were observed at 1 CpG site (cg27082185) and a negative correlation was observed at 1 CpG site (cg00027083) compared with the transcriptome levels (

Figure S2 and

Table S2). Although we did not conduct a functional study of these CpG sites, different CpG methylation sites may be responsible for the changes seen in

EPB41L3 transcriptome levels.

Our study has several limitations. First, control fibroblasts were obtained from normal portion of the resected cancer specimens. The gene expression profile of fibroblasts derived from lungs in which cancer developed may be different from that of fibroblasts derived from truly normal lungs. Secondly, we used the A549 and MRC-5 cell lines in the EMT and FMT studies instead of primary lung epithelial cells or fibroblasts. Thirdly, the EPB41L3 gene and protein levels were not measured using the sample such as bronchoalveolar lavage or lung tissues. To reveal the exact role of EPB41L3 in IPF, protein and gene levels of EPB41L3 should be evaluated in the lungs of the patients with IPF in terms of clinical manifestations by assessing the correlations of their levels with prognostic parameters, such as the long-term survival rate, in large number of patients.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Subjects

Lung fibroblasts and lung tissues of patients with IPF were obtained from the Biobank of Soonchunhyang University Hospital (Bucheon, South Korea) after approval of the study protocol by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University (201910-BR-058). The lung fibroblasts were cultured from the surgical specimens of 14 patients with IPF and the normal lungs of 10 subjects who underwent surgery to remove stage I or II lung cancer; their clinical characteristics were described previously [

10]. The diagnostic criteria for IPF were based on 2011 and 2018 international consensus statements [

37,

38]

4.2. Cell Culture

A549 (human epithelial cells, ATCC-CCL-185; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and MRC-5 (human fetal lung fibroblast cells; ATCC-CCL-171) were cultured in tissue culture medium (TCM) consisting of RPMI-1640 culture medium (GenDEPOT, Katy, TX, USA) or MEM culture medium with 100 U/mL penicillin (GenDEPOT) and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cells were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The A549 and MRC-5 cells were stimulated in TCM with 0.1% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) and 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) to induce the EMT and FMT.

4.3. RT-PCR and Real-Time PCR Analysis of EPB41L3 mRNA Expression

Total RNA was extracted using QIAzol reagent (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). Total RNA (3 μg) suspended in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water was heated at 65°C for 5 min with 0.5 μg of 10 mM dNTPs, which is a random hexamer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and then cooled on ice. Amplification was performed for 35 cycles (30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 61°C, and 30 s at 72°C) with extension at 72°C for 7 min. The primer sequences used were as follows: EPB41L3; sense 5’-TCG GAG ACT ATG ACC CAG ATG A-3’ and antisense 5’-GGT GCA AAG CGG AAC TCA CT-3’, β-ACTIN; sense 5’-GGA CTT CGA GCA AGA GAT GG-3’ and antisense 5’-AGC ACT GTG TTG GCG TAC AG-3’, N-cadherin; sense 5’-AGG GAT CAA AGC CTG GAA CA-3’ and antisense 5’-TTG GAG CCT GAG ACA CGA TT-3′, E-cadherin; sense 5’-CCA CCA AAG TCA CGC TGA AT-3’ and antisense 5’-GGA GTT GGG AAA TGT GAG C-3’, COL1A1; sense 5’-ACG TCC TGG TGA AGT TGG TC-3’ and antisense 5’-ACC AGG GAA GCC TCT CTC TC-3, FN1 ; sense 5’-ACA ACA CCG AGG TGA CTG AGA C and antisense 5’-GGA CAC AAC GAT GCT TCC TGA G, ACTA2 ; sense 5’-CTA TGC CTC TGG ACG CAC AAC T and antisense 5’-CAG ATC CAG ACG CAT GAT GGC A, VIM; sense 5’-AGG CAA AGC AGG AGT CCA CTG A, and antisense 5’-ATC TGG CGT TCC AGG GAC TCA-3. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide in Tris-borate EDTA buffer at 100 V for 35 min and visualized under ultraviolet light. The intensities of the EPB41L3, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, COL1A1, FN1, ACTA2, and VIM bands were normalized to those of β-actin. Real-time PCR was conducted using the StepOneTM Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The PCR mixture (20 μL) contained 1 μg cDNA, 10 μL of 2× Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), and 1 μL of the forward and reverse primers (10 pmol each). The reaction was executed in a two-step procedure: denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min, with melting at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 95°C for 15 s. The results were determined using the 2-ΔΔCT method (26) and are presented as fold-change normalized to β-actin.

4.4. Determination of Protein Levels by Western Blot

Proteins were extracted from cells in lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing proteinase and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Equal amounts of protein were resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked in 5% skimmed milk and incubated for 24 h at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-human EPB41L3 (1:2,000; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-human E-cadherin (1:1,000; Invitrogen), mouse monoclonal anti-human N-cadherin (1:1,000, Invitrogen), rabbit polyclonal anti-human collagen I (1:1,000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and mouse monoclonal anti-human β-actin (1:50,000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After washing several times with Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20, the membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit (1:5,000; GenDEPOT) or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000 and 1:100,000 for β-actin; GenDEPOT). The membranes were analyzed using chemiluminescence [Thermo Fisher Scientific and Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA)] with the ChemiDoc™ Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

4.5. Lentiviral Transduction to Overexpress EPB41L3 in A549 and MRC5 Cells

Stable transfection was performed using the Open Reading Frame (ORF) Lentiviral Transduction Particles kit (ORIGENE, Rockville, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The EPB41L3 Human Tagged ORF (Cat: RC209736L3V; ORIGENE) and corresponding control lentiviral particles (Cat: PS100092V; ORIGENE) were used for stable transfection. Lentiviral transduction was performed when the cells reached 70% confluence. EPB41L3 Human Tagged ORF clone-expressing lentivirus or Lenti-ORF control virus particles were added to the cells at a multiplicity of infection of 5 for A549 cells and 1 for MRC5 cells, along with 8 µg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were maintained in 5 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for approximately 10 days to establish stable cell lines. Then, mRNA and protein overexpression of EPB41L3 was determined by real-time PCR and western blot.

4.6. EPB41L3 Gene Silencing Using siRNA

siRNAs against EPB41L3 and scrambled siRNA (Bioneer, Daejeon, South Korea) were transfected into A549 and MRC5 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol when the cells were 70% confluent. The siRNA sequences used were siEPB41L3; sense 5’-GUG AAG ACG GAA ACC AUC A-3’ and antisense 5’-UGA UGG UUU CCG UCU UCA C-3’. The siRNAs (100 nM) were incubated in Opti-MEM (Gibco) solution for 5 min; 4 µl of Lipofectamine 2000 was mixed into the solution, which was then incubated for 20 min. The mixtures were added to the cells and incubated for 6 h at 37℃. The cells were cultured in 1% FBS-TCM with or without TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) for 48 h. Knockdown efficiencies were quantified by real-time PCR and western blot.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (ver. 20.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze continuous data. Skewed data are expressed as medians with 25% and 75% quartiles, and normally distributed data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Correlations between mRNA and protein EPB41L3 levels were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient analysis. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

5. Conclusions

Fibroblasts from the lungs of IPF patients expressed high mRNA and protein levels of the

EPB41L3 gene compared with controls.

EPB41L3 gene and protein expression was induced during the EMT and FMT. Overexpressing

EPB41L3 suppressed EMT- and FMT-related genes and proteins, while silencing

EPB41L3 upregulated them. These data demonstrate the inhibitory role of

EPB41L3 in the fibrosing process. Because TGF-β levels increase in the lungs of IPF patients [

39], the phenotypes of the fibroblasts may be changed by long-term stimulation with an excessive amount of TGF-β in the lungs of IPF patients. Thus, a balance between the amount of TGF-β (fibrotic factor) and EPB41L3 (anti-fibrotic factor) may determine the progress of fibrosis in patients with IPF.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

M.K.K.: validation, investigation, visualization/data presentation; J.-U.L.: investigation, validation, supervision, J.-S.P. and C.-S.P.: writing-review and editing, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (NRF-2022R1A2C1010172), and a Soonchunhynag University grant to Jong Sook Park.

Institutional Review Board Statement

It was mentioned in the materials and methods sections as follows: Lung fibroblasts and lung tissues of patients with IPF were obtained from the Biobank of Soonchunhyang University Hospital (Bucheon, South Korea) after approval of the study protocol by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University (201910-BR-058).

Informed Consent Statement

A written informed consent for donation of the samples to the biobank was obtained from all the subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Data of is freely available.

Acknowledgments

The biospecimens and data used for the present study were provided by the Biobank of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, a member of the Korea Biobank Network (KBN4_A06).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage, NC: normal controls, EMT: Epithelial-Mesenchymal transition FMT: fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition, transforming growth factor-β (TGF- β)

References

- Richeldi, L.; Collard, H.R.; Jones, M.G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet 2017, 389, 1941–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, R.C.; Mercer, P.F. Mechanisms of alveolar epithelial injury, repair, and fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015, 12 Suppl 1, S16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Collard, H.R.; King Jr, T.E. Classification and natural history of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 2006, 3, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, B.J.; Ryter, S.W.; Rosas, I.O. Pathogenic Mechanisms Underlying Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2022, 17, 515–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, E.; Sarvari, P.; Savai, R.; Seeger, W.; Pullamsetti, S.S. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Parenchymal Lung Diseases: Bystanders or Therapeutic Targets? Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, K.; Bailey, N.W.; Yang, J.; Steel, M.P.; Groshong, S.; Kervitsky, D.; Brown, K.K.; Schwarz, M.I.; Schwartz, D.A. Molecular phenotypes distinguish patients with relatively stable from progressive idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). PLoS One 2009, 4, e5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konishi, K.; Gibson, K.F.; Lindell, K.O.; Richards, T.J.; Zhang, Y.; Dhir, R.; Bisceglia, M.; Gilbert, S.; Yousem, S.A.; Song, J.W.; et al. Gene expression profiles of acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 180, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selman, M.; Pardo, A.; Barrera, L.; Estrada, A.; Watson, S.R.; Wilson, K.; Aziz, N.; Kaminski, N.; Zlotnik, A. Gene expression profiles distinguish idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis from hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 173, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengrong Zuo, N.K. , Eugui, John Allard, Zohar Yakhini, Amir Ben-Dor, Lance Lollini, David Morris, Yong Kim, Barbara DeLustro, Dean Sheppard, Annie Pardo, Moises Selman, and Renu A. Gene expression analysis reveals matrilysin as a key regulator of pulmonary fibrosis in mice and humans. Proceedings of the national Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002, 6292–6297. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-U.; Cheong, H.S.; Shim, E.-Y.; Bae, D.-J.; Chang, H.S.; Uh, S.-T.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, J.-S.; Lee, B.; Shin, H.D. Gene profile of fibroblasts identify relation of CCL8 with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiratory research 2017, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Piao, L.; Wang, L.; Han, X.; Tong, L.; Shao, S.; Xu, X.; Zhuang, M.; Liu, Z. Erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1-like 3 inhibits osteosarcoma cell invasion through regulation of Snai1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 13, 1947–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D.; Tamma, R.; Annese, T. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer: A Historical Overview. Transl Oncol 2020, 13, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, Y.; Nagase, H. Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer. Essays Biochem 2002, 38, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, J. DAL-1/4.1B contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition via regulation of transforming growth factor-β in lung cancer cell lines. Mol Med Rep 2015, 12, 6072–6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, R.; Huang, J.P.; Li, X.F.; Xiong, W.B.; Wu, G.; Jiang, Z.J.; Song, S.J.; Li, J.Q.; Zheng, Y.F.; Zhang, J.R. Epb41l3 suppresses esophageal squamous cell carcinoma invasion and inhibits MMP2 and MMP9 expression. Cell Biochem Funct 2016, 34, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, K.L.; Johnson, K.E.; Harrison, C.A. Targeting TGF-β mediated SMAD signaling for the prevention of fibrosis. Frontiers in pharmacology 2017, 8, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verrecchia, F.; Chu, M.-L.; Mauviel, A. Identification of novel TGF-β/Smad gene targets in dermal fibroblasts using a combined cDNA microarray/promoter transactivation approach. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 17058–17062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hocevar, B.A.; Brown, T.L.; Howe, P.H. TGF-β induces fibronectin synthesis through ac-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent, Smad4-independent pathway. The EMBO journal 1999, 18, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, N.; O’Connor, R.N.; Unruh, H.W.; Warren, P.W.; Flanders, K.C.; Kemp, A.; Bereznay, O.H.; Greenberg, A.H. Increased production and immunohistochemical localization of transforming growth factor-b in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1991, 5, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, N.; O'Connor, R.N.; Flanders, K.C.; Unruh, H. TGF-beta 1, but not TGF-beta 2 or TGF-beta 3, is differentially present in epithelial cells of advanced pulmonary fibrosis: an immunohistochemical study. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 1996, 14, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.S.; Schupp, J.C.; Poli, S.; Ayaub, E.A.; Neumark, N.; Ahangari, F.; Chu, S.G.; Raby, B.A.; DeIuliis, G.; Januszyk, M.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eaba1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, Y.K.; Bögler, O.; Gorse, K.M.; Wieland, I.; Green, M.R.; Newsham, I.F. A novel member of the NF2/ERM/4.1 superfamily with growth suppressing properties in lung cancer. Cancer Res 1999, 59, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Piao, L.; Wang, L.; Han, X.; Zhuang, M.; Liu, Z. [Corrigendum] Pivotal roles of protein 4.1B/DAL-1, a FERM-domain containing protein, in tumor progression (Review). Int J Oncol 2020, 56, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Guan, X.; Zhang, H.; Xie, X.; Wang, H.; Long, J.; Cai, T.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y. DAL-1 attenuates epithelial-to mesenchymal transition in lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015, 34, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Guan, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. DAL-1 attenuates epithelial to mesenchymal transition and metastasis by suppressing HSPA5 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep 2017, 38, 3103–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Piao, L.; Wang, L.; Han, X.; Zhuang, M.; Liu, Z. Pivotal roles of protein 4.1B/DAL-1, a FERM-domain containing protein, in tumor progression (Review). Int J Oncol 2019, 55, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, H.; Tang, Y.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xu, T.; Liu, W.; Su, X. C-MYC induces idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis via modulation of miR-9-5p-mediated TBPL1. Cell Signal 2022, 93, 110274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Tong, G.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, K.; Hu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Chen, R.; et al. CK2 blockade alleviates liver fibrosis by suppressing activation of hepatic stellate cells via the Hedgehog pathway. Br J Pharmacol 2023, 180, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scruggs, A.M.; Koh, H.B.; Tripathi, P.; Leeper, N.J.; White, E.S.; Huang, S.K. Loss of CDKN2B Promotes Fibrosis via Increased Fibroblast Differentiation Rather Than Proliferation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2018, 59, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, X.Q.; Xu, T.; Li, X.F.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.X.; Huang, C.; Meng, X.M.; Li, J. Role of histone deacetylases(HDACs) in progression and reversal of liver fibrosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2016, 306, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaiyar, A.; Juguilon, C.; Dong, F.; Cumpston, D.; Enrick, M.; Chilian, W.M.; Yin, L. Cardioprotection during ischemia by coronary collateral growth. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2019, 316, H1–h9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, H.M.; Ho, L.I.; Huang, M.H.; Huang, K.L.; Chiou, T.W.; Lin, S.Z.; Su, H.L.; Harn, H.J. Non-Canonical Regulation of Type I Collagen through Promoter Binding of SOX2 and Its Contribution to Ameliorating Pulmonary Fibrosis by Butylidenephthalide. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Pan, L.; Qi, S.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; Qian, C.; Chen, L.; Du, J. RNF2 Mediates Hepatic Stellate Cells Activation by Regulating ERK/p38 Signaling Pathway in LX-2 Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 634902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, S.; Yamada, D.; Fukami, T.; Masuda, M.; Sakurai-Yageta, M.; Williams, Y.N.; Maruyama, T.; Asamura, H.; Matsuno, Y.; Onizuka, M.; et al. Promoter methylation of DAL-1/4.1B predicts poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005, 11, 2954–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhou, F.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, N.; Yang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J. Identification of a DNA methylome profile of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and potential plasma epigenetic biomarkers for early diagnosis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.U.; Son, J.H.; Shim, E.Y.; Cheong, H.S.; Shin, S.W.; Shin, H.D.; Baek, A.R.; Ryu, S.; Park, C.S.; Chang, H.S.; et al. Global DNA Methylation Pattern of Fibroblasts in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. DNA Cell Biol 2019, 38, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Collard, H.R.; Egan, J.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Cordier, J.F.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lasky, J.A.; et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183, 788–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Morell, F.; et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruqaj, G.; Karnati, S.; Kotarkonda, L.K.; Boateng, E.; Bartkuhn, M.; Zhang, W.; Ruppert, C.; Günther, A.; Bartholin, L.; Shi, W.; et al. Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Regulates Peroxisomal Genes/Proteins via Smad Signaling in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Fibroblasts and Transgenic Mouse Models. Am J Pathol 2023, 193, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Comparison of mRNA and protein EPB41L3 levels in lung tissue-derived fibroblasts between 14 IPF patients and 10 controls. Expression of EPB41L3 mRNA (normalized to that of β-actin) was measured using (A) RT-PCR, (B) densitometry and (C) real-time PCR (log (2-△△Ct). Protein expression of EPB41L3 (normalized to that of β-actin) was measured using (D) western blot and (E) densitometry. (F) Correlations between the RT-PCR and western blot band intensities was analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r = 0.504, p = 0.012). Data are medians and quantiles, *p < 0.01.

Figure 1.

Comparison of mRNA and protein EPB41L3 levels in lung tissue-derived fibroblasts between 14 IPF patients and 10 controls. Expression of EPB41L3 mRNA (normalized to that of β-actin) was measured using (A) RT-PCR, (B) densitometry and (C) real-time PCR (log (2-△△Ct). Protein expression of EPB41L3 (normalized to that of β-actin) was measured using (D) western blot and (E) densitometry. (F) Correlations between the RT-PCR and western blot band intensities was analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r = 0.504, p = 0.012). Data are medians and quantiles, *p < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Changes in mRNA and protein expression of EPB41L3 and EMT-related genes expressed by A549 cells after stimulation with TGF-β. A549 cells were cultured with or without 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24, 48, and 72 h. The EPB41L3, N-cadherin, E-cadherin, and COL1A1 to β-actin ratios were measured using (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of six independent experiments. EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition. * p < 0.05 and ** p <0.01.

Figure 2.

Changes in mRNA and protein expression of EPB41L3 and EMT-related genes expressed by A549 cells after stimulation with TGF-β. A549 cells were cultured with or without 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24, 48, and 72 h. The EPB41L3, N-cadherin, E-cadherin, and COL1A1 to β-actin ratios were measured using (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of six independent experiments. EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition. * p < 0.05 and ** p <0.01.

Figure 3.

Effect of EPB41L3 transfection on EMT-related genes in the A549 cell line. Changes in EPB41L3 and EMT-related gene expression after EPB41L3 transfection in the presence and absence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 48 h. Expression of mRNA and protein normalized to β-actin levels were measured by (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Lv = Lentivirus, * p <0.05 and ** p <0.01.

Figure 3.

Effect of EPB41L3 transfection on EMT-related genes in the A549 cell line. Changes in EPB41L3 and EMT-related gene expression after EPB41L3 transfection in the presence and absence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 48 h. Expression of mRNA and protein normalized to β-actin levels were measured by (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Lv = Lentivirus, * p <0.05 and ** p <0.01.

Figure 4.

Effect of silencing EPB41L3 on EMT-related genes in A549 cells. Changes of EPB41L3 expression in response to EPB41L3 siRNA in the presence and absence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 48 h. Expression of mRNA and protein normalized to the β-actin level was measured using (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. * p <0.05.

Figure 4.

Effect of silencing EPB41L3 on EMT-related genes in A549 cells. Changes of EPB41L3 expression in response to EPB41L3 siRNA in the presence and absence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 48 h. Expression of mRNA and protein normalized to the β-actin level was measured using (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. * p <0.05.

Figure 5.

Changes in mRNA and protein levels of EPB41L3 and FMT-related genes expressed by MRC5 cells after stimulation with TGF. MRC5 cells were cultured with or without 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24, 48, and 72 h. The EPB41L3, FN1, ACTA2, N-cadherin, and COL1A1 to β-actin ratios were measured using (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot and (C) densitometry. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. * p <0.05 and ** p <0.01.

Figure 5.

Changes in mRNA and protein levels of EPB41L3 and FMT-related genes expressed by MRC5 cells after stimulation with TGF. MRC5 cells were cultured with or without 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24, 48, and 72 h. The EPB41L3, FN1, ACTA2, N-cadherin, and COL1A1 to β-actin ratios were measured using (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot and (C) densitometry. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. * p <0.05 and ** p <0.01.

Figure 6.

Effect of EPB41L3 transfection on FMT-related genes in the MRC5 cell line. Changes in the expression of EPB41L3 and FMT-related genes in response to EPB41L3 transfection in the presence and absence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 48 h. Expression of mRNA and protein normalized to the β-actin level were measured using (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. Lv = Lentivirus. * p <0.05 and ** p <0.01.

Figure 6.

Effect of EPB41L3 transfection on FMT-related genes in the MRC5 cell line. Changes in the expression of EPB41L3 and FMT-related genes in response to EPB41L3 transfection in the presence and absence of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 48 h. Expression of mRNA and protein normalized to the β-actin level were measured using (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. Lv = Lentivirus. * p <0.05 and ** p <0.01.

Figure 7.

Effect of silencing EPB41L3 on FMT-related genes in MRC5 cells. Changes in the expression of EPB41L3 and FMT-related genes in response to EPB41L3 siRNA. Expression of mRNA and protein were measured by (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. * p <0.05.

Figure 7.

Effect of silencing EPB41L3 on FMT-related genes in MRC5 cells. Changes in the expression of EPB41L3 and FMT-related genes in response to EPB41L3 siRNA. Expression of mRNA and protein were measured by (A) real-time PCR, (B) western blot, and (C) densitometry of protein bands. Data are mean ± SE of 6 independent experiments. * p <0.05.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).