1. Introduction

Highlights:

Hidden portrait of Werner Tübke's father was revealed.

The state of the painting, the texture of the author's brushstroke, the technique of applying the paint layer, the artist's work on the composition and the types of pigments and binders used have been identified.

The unique artistic language of Werner Tübke at an early stage of the artist's work was examined.

Grounds have been laid for future comparison of Tübke's early paintings with his later works, as well as his contemporaries and predecessors.

The advantages of using multidisciplinary study are described.

I paint in stages. At the beginning I make a false colour in tempera mixed with chalk, then I add English colours: black, red and white. I don't go too deep or into perspective. In the second layer, I intensify the colour with mother of pearl glaze which I apply on top of the darker shades. The white mixture is made up of a tempera white and an oil white. I then apply an intermediate coat of varnish from damask, turpentine and Venetian turpentine at a ratio of 60 : 30 : 10. It is only the third coat that I start painting rationally in the alla prima technique in one session until the colours are completely dry, using dammar, poppy oil and turpentine in a 2 : 1 : 1 ratio" [

1].

One of the many diary entries of Werner Tübke (1929 - 2004), the leading official artist of the GDR and, along with Wolfgang Mattheuer, Bernhard Heising and Willy Sitte, the most outstanding representative of the Leipzig school of painting [

2,

3,

4], gives a faithful representation of this master. His adherence to the classical tradition of easel painting and his universal mastery of painting techniques is one of the unique features of his oeuvre. As an artist with higher not only artistic but also pedagogical education, Tübke brilliantly mastered the techniques of the old masters, disregarding the methods of pre- and post-war modernism [

5].

Consider the famous "Peasant War Panorama" at Bad Frankenhausen (1976 - 1988), the monumental painting "The Working Class and the Intellectuals" at the University of Leipzig (1973), the triptych "Man is the Measure of All Things" for the Palace of the Republic in Berlin (1975) or his altarpiece in the church in Clausthal-Zellerfeld (1997) [

6,

7,

8,

9]. All of these pieces stand out for their intricate link to the traditions of 15th- and 20th-century painting, not only on the level of iconography and style, but also in terms of technology. The artist himself described the process of creating each work in detail: selecting the base of the painting, the type of primer, creating the preliminary drawing, selecting the composition of binders, varnishes and pigments, he was guided by the techniques of the old masters, among whom he was particularly influenced by Brueghel and the representatives of naturalistic realism of the late Middle Ages, The art of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in northern Europe, the German tradition of Dürer, Grunewald, the Cranach and Baldung, but also Italian Mannerism and its influences from Flanders to Spain, Goya and late Venetian painters like Magnasco, Tiepolo and Longi. He never directly imitated the German Romantics, neither Friedrich nor Runge, but constantly had the Nazarenes (especially Julius Schnorr von Karolsfed, maybe indirectly Schwind) and the early Düsseldorf school (Wilhelm Schadow) in mind [

10].

All key experts on Tübke's art have written about the deep connection between Tübke's art and the traditions of the old masters. Günter Meissner, the master biographer, presents an extensive monograph entitled “Werner Tübke : Leben und Werke” [

11], which describes Tübke's artistic education: his childhood and drawing studies in Schönebeck, his years at the art school in Magdeburg, at the University of Greifswald and at the University of Graphic Arts Leipzig, his career choice and early artistic quests, his teachers and the premises for his realistic style and historical thinking. Another serious scholar, Harald Behrendt's "Werner Tübkes Panoramabild in Bad Frankenhausen: Zwischen staatlichem Prestigeprojekt und künstlerischem Selbstauftrag" [

12,

13,

14] has a depth and attention to detail. The author not only describes the twelve-year process of creating the monumental panorama in great detail, but also gives a detailed commentary on the role of colour and the composition in the spirit of the old masters. Eduard Bokamp dedicates the book "Werner Tübke. Arbeiterklasse und Intelligenz. Eine zeitgenössische Erprobung der Geschichte" (Working class and intelligentsia) [

15] and numerous allusions to art from the past. The book "Zellerfelder Flügelaltar von Werner Tübke und seine Vorarbeite" [

16] focuses on the artist's later work, the Altar in Clausthal-Zellerfeld (1997), and includes a description of the artist's late technique. Finally, Rudolf Kober and Gerd Lindner devoted a very informative and important article to the influence of Matthias Grunewald's painting on artists in the GDR and Tübke in particular [

17].

Nevertheless, despite the general understanding of the need to consider Tübke's heritage in the context of the great artistic tradition of European painting, at the level of analysis of precise material a certain limitation of approaches is revealed. Most of the authors of publications on Tübke are interested in the iconography of his works and the context of their creation. Often they move away from the art itself and focus on the ideological views of the state painter. For all the value of each statement, a rare author allows himself, after studying in detail this or that piece, to look at it "closely" and ask more specific questions. It seems to us that in the case of such an adherent of the ancient tradition of easel painting as Tübke, a specific work of art and its individual characteristics should serve as the main source and material of research, and, for example, the technological analysis of his works can help us answer the question of what is the originality of his art, why it is so interesting to look at him today, and what are the preconditions for his works.

In order to understand Tübke's technology, it was decided to conduct a multidisciplinary study [

18,

19,

20] of his paintings in the department of technical and technological research at the Russian Museum, using the following methods: optical microscopy, photos in the light of visible luminescence, infrared reflectography, radiography, portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF), infrared-Fourier spectroscopy (FT-IR) and polarization microscopy. The only known Tübke’s painting in Russia was taken as the object of analysis. It is "Hiroshima I" (canvas, oil, NT-287), presented to the Russian Museum in 1995 by collector Peter Ludwig [

21]. Tübke's choice of subject matter is revealing: along with current events, Tübke's themes cover primarily historical subjects. In Hiroshima I, for example, he reflects the American atomic bombing of the Japanese city of the same name in 1945: a destroyed cityscape, a chaotic mixture of bodies, people lying motionless or gesticulating, debris and bicycle parts. This work was produced in 1958, at a time when the artist was making a decisive shift away from modernism towards figurative painting. This transition was most clearly reflected in the diptychs from the Five Continents cycle, which he painted in 1958 for the Astoria Hotel in Leipzig as part of a government commission. It was then that he first so explicitly used the masters of the German Renaissance as his models. The painting Hiroshima I, on the other hand, represents a modernist experiment peculiar to his early work and not characteristic of his mature period. Nevertheless, a laboratory study of this painting seems important because of the need to study Tübke's painting technique and the unique features of his paintings (such as hidden images, author's edits and the pigment composition of the image) in order to understand and preserve his heritage for future generations.

Figure 1.

Hiroshima. Werner Tübke. Oil on canvas, 1958, 45.4 x 38.3 cm.

Figure 1.

Hiroshima. Werner Tübke. Oil on canvas, 1958, 45.4 x 38.3 cm.

2. Materials and Methods

Photofixation of images in visible light was carried out using a Nikon D850 camera, fix lenses of 50 mm and 200 mm for macro photography. Similarly, images were obtained in visible luminescence using Master Alpha 16 UV 365 nm LED. Nikon D800 with an infrared filter removed from a digital matrix and Master Alpha 16 IR 950 nm LED sources was used to obtain infrared reflectography images.

The elemental analysis was carried out using an energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometer TRACER 5 (Bruker) with a thin graphene window and a rhodium anode (Rh), a silicon drift detector cooled by Peltier elements. The results were obtained by analysis in the air in the mode of 40 keV, 300 µA, software “Artax".

In order to determine the composition of binders and pigments FT-IR spectroscopy (TENSOR 37, Bruker) was used. The spectra were recorded in an ATR (MVP-Pro™, Harrick) mode in the range 4000–380 cm-1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm-1. Sample preparation was carried out by crushing the sample and placing it on the surface of a diamond crystal. Single-point ATR measurements were performed by recording a total of 128 scans and averaging the resulting interferograms. All spectra were pro-cessed using extended ATR correction (1 reflection, angle of incidence 45°, average refractive index 1.5), in some cases non-informative regions of the spectra (2400–1850 cm–1) were removed, and baselines were corrected. For identification of substances, the obtained spectra were compared with the library data in the FT-IR spectrometer.

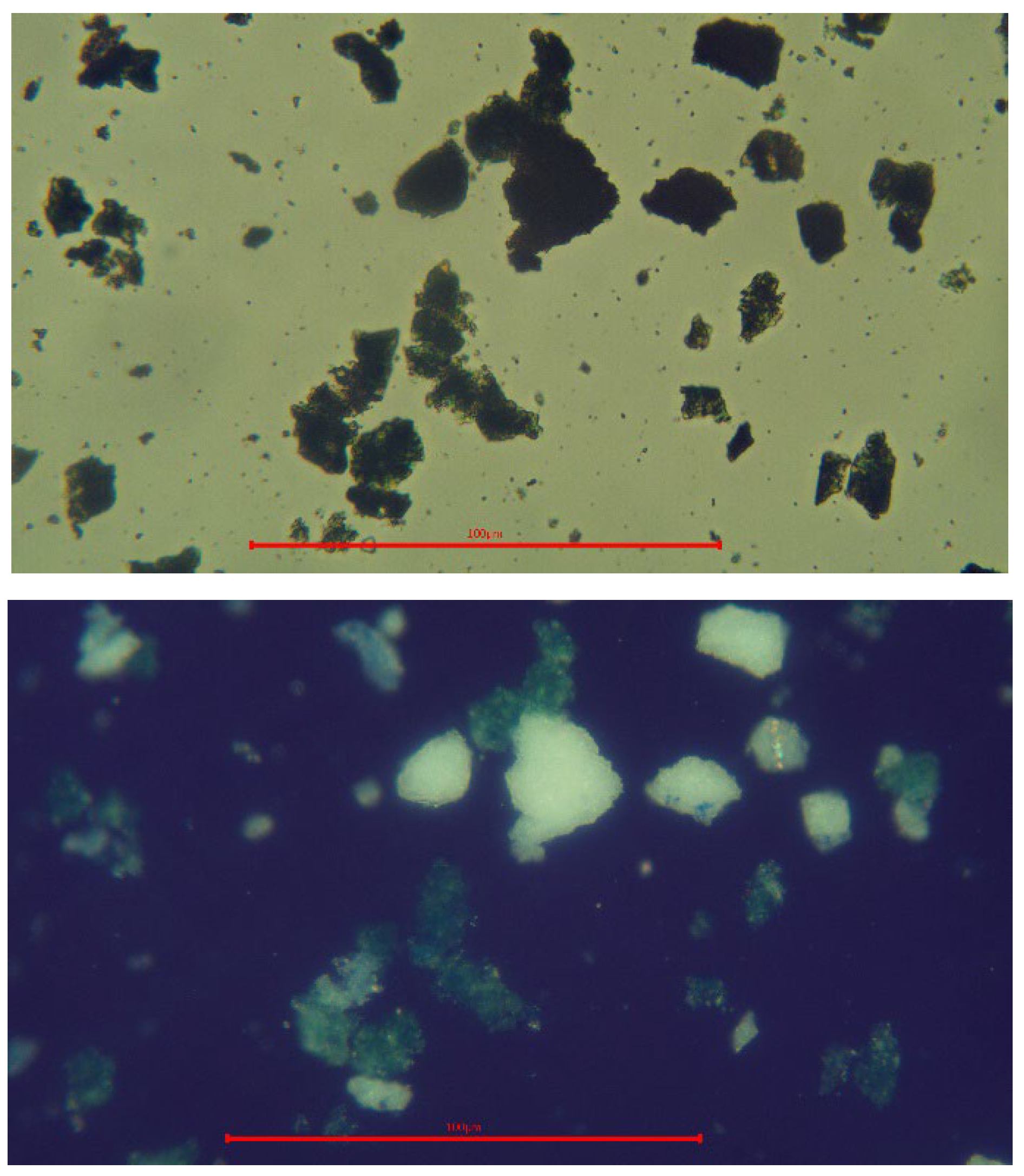

To clarify the pigment composition of the colorful layers, in some cases, a polarizing microscope PLM-2 (LOMO Microsystems) was used, designed to study objects in transmitted and reflected light, ordinary and polarized.

The analysis of the painting surface and sampling was performed using a STEMI 2000 binocular stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Observations by Visual Analysis

Visual inspection of the painting allowed us to assess the state of preservation and technical features of the upper colorful layers [

22]. The underlying green layer of painting is viewed through a microscope (

Figure 2a,b). The underlying painting was partially scraped (erased), in places to the canvas. No signatures or inscriptions were found on the painting. Canvas with a rare weave and a thick layer of sizing. There is no developed craquelure in the picture, and there is also no lacquer film. The primer is factory-made, preserved on the edges. Several scree along the edges of the painting also indicate careless storage of the painting before its arrival in the museum (

Figure 2a–c).

3.2. Observations by UV luminescence, IRR, radiography

Photography in the light of visible luminescence (

Figure 3a) revealed the heterogeneous structure of the blue sky, and also allowed us to identify luminescent pigments, which in most cases are organic compounds. This fact was later confirmed by the results of X-ray spectral analysis and infrared Fourier spectroscopy [

22,

23,

24].

Based on the results of infrared refletography, no significant alterations were found. The underlying image is already overlooked in the photo – a portrait rotated 90 degrees.

To clarify the identity of the person depicted, an X-ray was obtained (

Figure 4) [

22]. The most similar person on the X-ray is Werner Tubke's father.

3.3. Elemental analysis of pictorial layers (XRF)

The method of X-ray fluorescence was used to carry out non-destructive analysis of chemical elements. As a non-destructive method, this technique was performed at 9 different points of the painting (

Figure 5) to get meaningful data about pigments and collect all the different chromatic shades that define the artist's palette. X-ray diffraction analysis (

Table 1) revealed the presence of elements such as lead (Pb), zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), cadmium (Cd), selenium (Se), chromium (Cr), calcium (Ca) and barium (Ba). This canvas was made of lead white [2PbCO

3 x Pb(OH)]. It is a pigment that has been widely used since ancient times both for making primers and for mixing in layers of painting [

25], as well as calcium, a typical filler for primers and paints in the form of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) or two-water gypsum (CaSO

4 x (H

2O)

2). The whitewash is made with a mixed pigment based on zinc (ZnO) and lead white [

25,

26].

Chromatic pigments are represented by a wide palette, including organic pigments that cannot be identified using this method. The inorganic red pigment is cadmium red (CdX x CdSe) (

Figure 6), a widely used pigment since the early 20th century, used as a substitute for the classic red pigment cinnabar (HgS) [

27]. Some of the red pigments remained unrecognized by the results of X-ray fluorescence, since no characteristic cadmium peaks were detected. To refine them, the method of infrared-Fourier spectroscopy was used.

The blue pigment was also not recognized, which suggests the use of either organic blue pigments or blue ultramarine (Na

6Ca

2(AlSiO

4)

6(SO

4,S,CO

3)

2). The artist used cadmium yellow (CdS) as a yellow pigment [

27]. The green pigment based on spectral data is a chromium-containing pigment. It can be chromium oxide (Cr

2O

3 chromium oxide hydrate (Cr

2O

3 x H

2O), volkonskite (СаО

3 (Сr

3+, Mg

2+, Fe

2+)

2 (Si, Al)

4 O

10 (OH)

2 ∙ 4H

2 O [

28] or a mixture of blue and yellow chromate. Purple pigment may be purple mars (Fe

2O

3). Refinement of this pigment was also carried out using FTIR and polarization microscopy.

Iron-containing pigments are also found in the composition of the colorful layers. Barium, most likely barium sulfate (BaSO

4) was found as an inert filler of paints [

29].

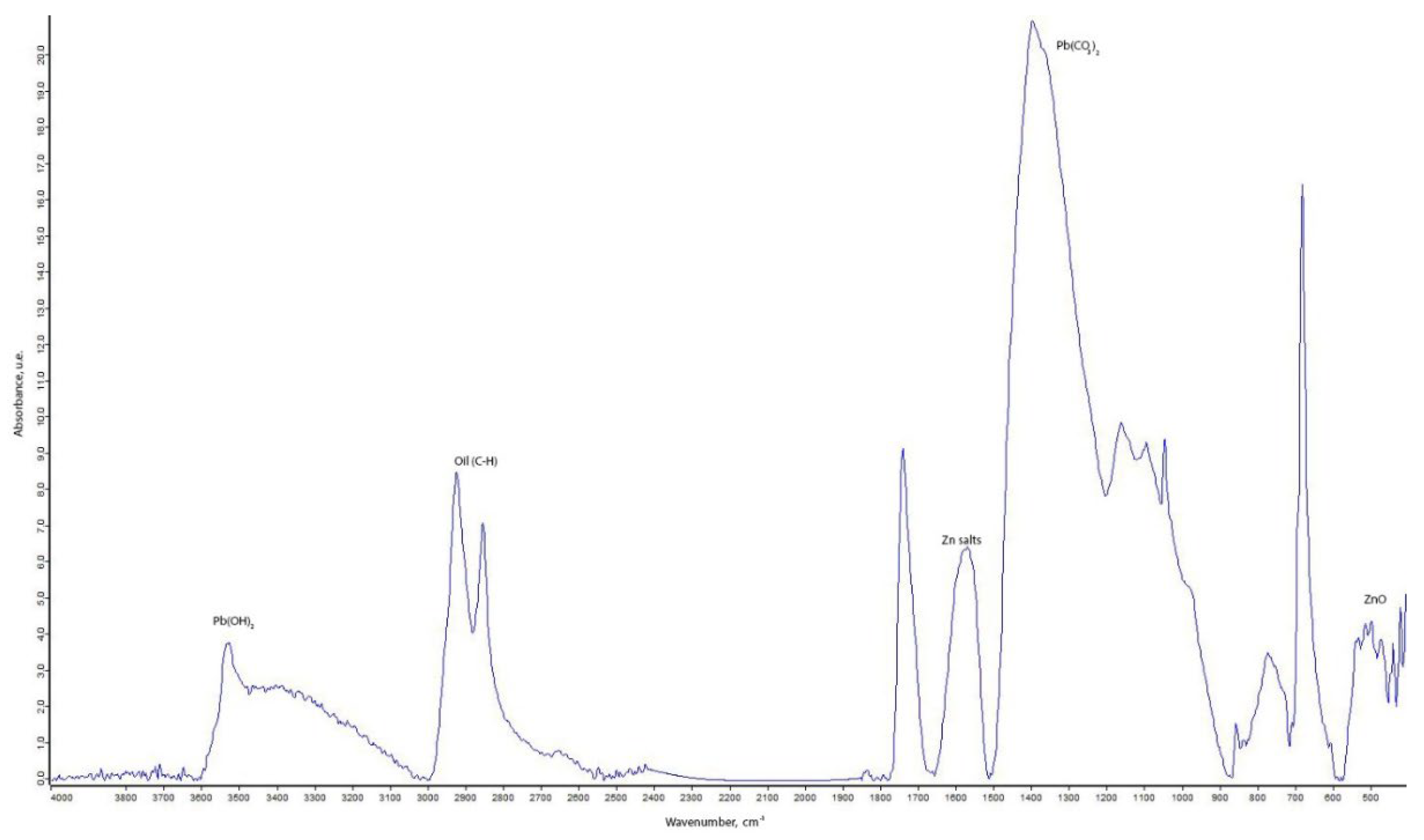

3.4. FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy and polarizing microscopy

Using only XRF does not give a complete understanding of the artist's color palette due to the physical limitations of the method. In this case, it is logical to use another spectral method – infrared-Fourier spectroscopy. The absence of characteristic peaks for inorganic pigments almost always refers to the use of molecular analysis methods.

The presence of the oil component is confirmed by intense absorption bands of asymmetric

and symmetric

stretching vibrations of the methylene group at 2919 cm

-1 and 2850 cm

-1, stretching vibrations of the carbonyl group

at 1736 cm

-1 and stretching vibrations of the ester bond

at 1160 cm

-1 [

30].

The white, according to the IR spectrum, corresponds to the composition of lead-zinc white (2(PbCO

3) x Pb(OH)

2; ZnO). Currently, lead white is not produced on an industrial scale due to the high toxicity of production. In the mid-infrared range, IR spectrum (

Figure 7) shows the main absorption bands of the lead components - the stretching vibrations of the hydroxyl group

at 3537 cm

-1, asymmetric

) and symmetric

stretching vibrations of the carbonyl group at 1396 cm

-1 and 1045 cm

-1, and out-of-plane

and planar

bending vibrations of the carbonyl group at 851 cm

-1 and 679 cm

-1 [

31]. We also note in the low-frequency infrared region of the IR spectrum of white paint the absorption bands of zinc. They corresponded to a broad peak at 525 cm

-1 – stretching vibrations of zinc oxide

[

32].

The blue pigment according to the research results is ultramarine. The red pigment of the XRF #7 spot is a red litole (PR3), yellow hansa PY3 [

33,

34]. The green pigment was not determined during this study. In order to refine it, polarization microscopy was used. Indirectly, one can judge the presence of such a green pigment as volkonskoite. It was opened at the beginning of the last century in Russia by Prince Volkonsky [

28].

4. Conclusions

The use of an integrated interdisciplinary approach allows you to accurately describe the object under study. The use of non–invasive visualization methods - UV, IRR, radiography allows an art critic and a curator to look at an art object from other grain points. The determination of the pigment composition and binders can be useful in the dating of paintings, and also simplifies the preparation for the restoration process.

The determination of the green pigment turned out to be difficult due to the absence of characteristic peaks of pigment absorption in the mid-infrared region. Therefore, we can only assume the use of green volkonskite, based on the data of polarization microscopy and the presence of chromium in the XRF spectrum.

Typical pigments for painting of the 20th century were also identified: lead-zinc whitewash, red cadmium selenide sulfide, yellow cadmium sulfide, blue ultramarine, red litol PR3, yellow hansa PY3.

All the results of the study described are significant not only in terms of assessing the condition and storage conditions of the Hiroshima I painting. The findings are also valuable from an art historian's point of view: they clearly demonstrate what modernist experiments in the artist's oeuvre were like.

Thus, preliminary observations by visual analysis vividly demonstrates the expressive manner of this piece: the strokes are textured, there are no subtle glazes, the painting is done in alla prima technique in a single stroke - the way many expressionist painters painted, both earlier and nowadays. At the same time, the ultraviolet photography shows that even in this case, Tübke made changes to the composition of the painting, changing (recording) the insignificant details.

Of particular interest in the examination carried out are observations by UV luminescence, IRR and radiography. These examination methods demonstrated the underlying layer of the painting, leading to the assumption that another painting was concealed beneath the Hiroshima image. Radiography confirmed this hypothesis by revealing a male portrait beneath the top layer that had been partially scraped (erased), in places, to the canvas. Comparison of the resulting image with the drawings by Tübke of the time confirmed the art historian's guess: the portrait of the artist's father on a green background is hidden under Hiroshima [

35]. In contrast to the expressive painting of the upper layer, the portrait was executed in a more substantive, precise, academic manner, which the artist developed over the years.

An unobvious connection between Hiroshima and Tübke's later works was also revealed by elemental analysis of pictorial layers (XRF), infrared-Fourier spectroscopy (FT-IR) and polarization microscopy. In particular, green pigment volkonskoite and (presumably) Gutankara violet were found among the pigments of Tübke paints. The exact elemental composition of these pigments raised questions. Curiously enough, the same pigments have aroused the interest and bewilderment of German colleagues studying Tübke's artistic legacy. In the autumn of 2022, the author of this article travelled to the artist's homeland in Germany, including the Werner Tübke Archive in Leipzig and the Panorama Museum in Bad Frankenshausen. The director of the Panorama Museum, Professor Gerd Lindner, explained that Tübke's only similar technical study in Germany was of the "Peasant War Panorama" (1976-1988): for the conservation and restoration of the monumental canvas, an expertise was conducted in the 1990s and data was obtained, primarily concerning its paint layer. A colleague raised questions about the same pigments: Volkon's Green Earth and Gutankara's Purple; they were unable to identify them precisely. The authors of the article suggested that Tübke used these pigments to imitate the paintings of the old masters [

36,

37]. This theory is currently being refined; we plan to report on it in future research.

Thus, even in an example as atypical of Tübke's painting as Hiroshima I, laboratory analysis reveals how meticulously he approached painting early in his career. The upper layer of paintings in expressive technique can be regarded more as a sketchbook in relation to his later works. The portrait of his father, on the other hand, anticipates his painting of the 70s and 80s (the artist's heyday period): it is executed in an academic manner and corresponds to the national German tradition of figurative painting and easel painting. It appears that already in the 1950s, at a time of changes in cultural policy in the GDR with its course towards socialist realism and the increasing ideological pressure on art, Tübke was looking for a language in which he could speak freely, while remaining a politically engaged artist. In his early encounters with both pre-war modernism and the old masters, Tübke always aimed for a statement that was not linked to ideology or a specific artistic movement, yet was also invisibly linked to past traditions (Portrait of his father). One gets the impression that the artist was driven by the desire to preserve the national style amidst the destruction of memory after the Third Reich, the Second World War and the emergence of the GDR. It was a search for an answer to the question of what it means to be a German painter in post-war conditions.

The study is an example of how laboratory methods can be applied for the art history analysis of painting, which as art is more complex and meaningful and cannot be exhausted with the data of ideological discourse. Tübke's legacy turns out to be all too original (no such artists existed in the Third Reich or the Soviet Union) and his works reveal an artistic freedom that prevents him from being recognized as a pure formalist [

38]. This fact seems important from the point of view of assessing and preserving an important testimony of German cultural heritage and Werner Tübke's artistic legacy in honesty.

Acknowledgments

The research was carried out with the support of a grant under the Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 220 of 09 April 2010 (Agreement No. 075-15-2021-593 of 01 June 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Tübke, W., Mein Herz empfindet optisch: Aus den Tagebüchern, Skizzen und Notizen. Herausgegeben von Annika Michalski und Eduard Beaucamp; Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2017; ss. 396.

- Behrendt, H. Die Leipziger Malschule und Werner Tübke. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte. 2008. 71. Bd., H. 1 pp. 101-120. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40379326.

- Eisman, A. Bernhard Heisig and the Fight for Modern Art in East Germany. Boydell and Brewer, Camden House, 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1qv129.

- Makarinus, J. Über die Entfaltung der "Berliner Schule". Staatliche Museen zu Berlin // Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Forschungen und Berichte, 1991, Bd. 31, pp. 313-328. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3881104.

- Osmond, J. German Modernism and Anti-Modernism; Weimar : The Burlington Magazine, 1999, Vol. 141, No. 1158; pp. 574-575. https://www.jstor.org/stable/888618.

- Tübke W. Gemalde, Aquarelle, Druckgrafik, Zeichnungen. Dresden-Leipzig-Berlin: Ministerium für Kultur DDR, 1976, 256 S.

- Tübke W. Das malerische Werk : Verzeichnis der Gemälde 1976 bis 1999; Amsterdam-Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 1999; s. 299.

- Michalski, A. Zöllner, F. Tübke-Schellenberger, Brigitte. Das „Grüne Skizzenbuch“ Werner Tübkes von 1952”; Leipzig: Plöttner, 2010.

- Michalski, A., Zöllner F. Tübke Stiftung Leipzig: Bestandskatalog der Gemälde; Leipzig: Plöttner, 2008; s. 90.

- Loest, E. Tübke-Bild im Fundus verwahren // Journal Universität Leipzig, 2004; №6; s. 3.

- Meißner G. Werner Tübke : Leben und Werke; Leipzig: Seemann, 1989; ss. 400.

- Behrendt, H., Werner Tübkes Panoramabild in Bad Frankenhausen: Zwischen staatlichem Prestigeprojekt und künstlerischem Selbstauftrag / Bau + Kunst; Kiel : Schleswig-Holsteinische Schriften zur Kunstgeschichte, 2006; ss. 422.

- Gillen, E. One can and should present an artistic vision.. of the end of the world": Werner Tübke's Apocalyptic Panorama in Bad Frankenhausen and the End of the German Democratic Republic // Getty Research Journal, 2011, No. 3, pp. 99-116. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23005390.

- Tübke, W. Monumentalbild Frankenhausen / Text: Karl Max Kober. Dresden : VEB Verlag der Kunst, 1989; s. 104.

- Beaucamp, E. Werner Tübke. Arbeiterklasse und Intelligenz. Eine zeitgenössische Erprobung der Geschichte; Frankfurt a. M.: Fisher, 1985; ss. 310.

- Zellerfelder Flügelaltar von Werner Tübke und seine Vorarbeiten / Mit Texten von H. von Poser, Eduard Lohse, Gerd Lindner, Johanna Brade, Rudolf Kober; Bad Frankenhausen: Panorama Museum Bad Frankenhausen, 2007; ss. 144.

- Kober, R., Lindner, G. Paradigma Grünewald. Zur Erbe-Rezeption in der bildenden Kunst der DDR / Grünewald in der Moderne. Die Rezeption Matthias Grünewald im 20. Jahrhundert. o.A. Schad, Brigitte / Ratzka, Thomas; Köln : Wienand Verlag, 2003.; ss. 192.

- Grenberg U. I. Technology of easel painting: History and research. Moscow : Fine Arts, 1982. - 319 с. : ill. ; 22 cm. Bibliography: p. 308-318 (291 titles).

- D.I. Kiplik. Technique of painting / D. I. Kiplik. Moscow : V. Shevchuk, 2011. 502, [1] p., [15] l. ill. ; 22 cm.

- Feinberg, L. E., Grenberg, U. I. Secrets of old masters' painting / [Afterword by V.P. Tolstoy, Doctor of Arts, Corresponding member of USSR Academy of Arts]. M. : Fine Art, 1989; 319 с. illustration: colored illusions. ; 29 cm.

- .

- Haddad, A., Hartman, D., Martins, A., Complex Relationships: A Materials Study of Édouard Vuillard’s Interior, Mother and Sister of the Artist, 2021, Heritage Science, 4(4), 2903-29, . [CrossRef]

- Manzano E., Blanc R, Martin-Ramos J.D., Chiari G., Sarrazin P., Luis Vilchez J., A combination of invasive and non-invasive techniques for the study of the palette and painting structure of a copy of Raphael’s Transfiguration of Christ, 2021, Heritage Science, 9, 150, . [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, S., Vanmeert ,F., Vertongen, R., Van Loon ,A., Gonzalez, V., Delaney, J., Dooley, K., Dik J., Van der Snickt, G., Vandivere, A., Janssens, K., Macroscopic X-ray powder diffraction imaging reveals Vermeer’s discriminating use of lead white pigments in Girl with a Pearl Earring, 2019, Sci. Adv., vol.5, issue8: . [CrossRef]

- Calza, C., Oliveira, D.F., Freitas, R.P., Rocha, H.S., Nascimento, J.S., Lopes, R.T., Analysis of sculptures using XRF and X-ray radiography, Radiat. Phys. Chem., 2015, vol. 116, p. 326-331. [CrossRef]

- Giorgi L., Nevin A., Comelli D., Frizzi T., Alberti R., Zendri E., Piccolo M., Izzo F.C., In-situ technical study of modern paintings - Part 2: Imaging and spectroscopic analysis of zinc white in paintings from 1889 to 1940 by Alessandro Milesi (1856–1945), Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 219, 2019, p. 504–508. [CrossRef]

- Saverwyns, S., Currie C., Lamas-Delgado E., Macro X-ray fluorescence scanning (MA-XRF) as tool in the authentication of paintings, 2018, vol. 137, p. 139-147. [CrossRef]

- Hani, N. Khoury, Importance of Clay Minerals in Jordan Case Study: Volkonskoite as a Sink for Hazardous Elements of a High pH Plume, JJEES, 2016, vol. 6, p. 1-10. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278686077_Journal_Volk_Hani_Vol6SP3_HQ_P1-10.

- Rosi, F., Burnstock A., Klaas Jan Van den Berg, Miliani C., Giovanni Brunetti B., Sgamellotti A., A non-invasive XRF study supported by multivariate statistical analysis and reflectance FTIR to assess the composition of modern painting materials, Spectrochimica Acta Part A 71, 2009, p. 1655–1662. [CrossRef]

- Van der Weerd , J., van Loon A., J. Boon, FTIR studies of the effects of pigments on the aging of oil, 2005, Studies in conservation, 50(1): 3-22. [CrossRef]

- Catalli K., Santillan J., Williams, Q. A high pressure infrared spectroscopic study of PbCO3-cerussite: constraints on the structure of the post-aragonite phase, 2005, Phys Chem Minerals 32: 412–417. [CrossRef]

- Osmond, G., Zinc Soaps: An Overview of Zinc Oxide Reactivity and Consequences of Soap Formation in Oil-Based Paintings, 2019, Metal Soaps in Art: 25-46. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J., Singer B. W., Perry J. J., Bacon A., The identification of synthetic organic pigments in modern paints and modern paintings using pyrolysis-gas chromatography–mass spectrometryAnal Bioanal Chem (2011) 400, p. 1473–1491. [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, B.N., Pause R., van der Werf I.D., Astefanei A., van den Berg K.J., van Bommel M. R., Analytical approaches for the characterization of early synthetic organic pigments for artists’ paints, Microchemical Journal, 2021, vol. 170. [CrossRef]

- Linder, G. Werner Tübke. Handzeichnungen und Aquarelle; Leipzig, 1992; s. 65.

- Menu M., Ezrati J.J., Laval É., Pagès S., Pricipaud A. Rioux J.P., Waiter P., Welcomme É., Nowik W. Analyse de la palette des couleurs du Retable d'Issenheim par Matthias Grünewald = Analyse der Farbpalette des Isenheimer Retabels von Matthias Grünewald = Analysis of the palette used by Matthias Grünewald in the Isenheim Altarpiece = Colmar Musée d'Unterlinden. Source : - 2006.

- Fontoura, P., Menu M. Visual perception of natural colours in paintings: An eye-tracking study of Grünewald's Resurrection. March 2021. Color Research & Application 46(7). [CrossRef]

- Lewer, D. Review: After Fascism: Two Views of Two Germanys // Oxford Art Journal, 2009, Vol. 32, No. 3, Mal'Occhio: Looking Awry at the Renaissance Special Issue, pp. 466-471. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25650883.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).