1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, international students enrolled in universities worldwide have skyrocketed to over five million, making International Student Migration (ISM) a significant trend in higher education (UIS Statistics, 2023). Despite this, little research has been conducted on the potential impact of emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), on the education of international students. This paper addresses this gap by exploring how AI can improve educational administration, curriculum development, teaching, and learning processes for international students.

To achieve this goal, the paper will address the following research question: What is the impact of artificial intelligence on the education of international students, and how can it be used to improve various aspects of educational administration, curriculum development, teaching, and learning processes? AI in education has the potential to provide international students with personalized and adaptive learning opportunities (Ouyang & Jiao, 2021; Zhai et al., 2021). For example, AI-powered applications can develop customized content and offer language translation services, making education more accessible to those with language barriers (Jiang et al., 2021; Lehman-Wilzig, 2001). Similarly, AI-based writing and revision assistants can provide valuable feedback on students’ work, enabling them to hone their writing skills and improve their grades (Niyozalievna, 2022; Parra & Calero, 2019).

However, using AI in education has limitations and risks. AI-powered voice recognition and dictation tools may struggle with accents and dialects, potentially leading to misunderstandings or miscommunications (Martin & Wright, 2022; Mengesha et al., 2021). Additionally, AI-based English language learning applications may not offer a broad enough view of language and culture, limiting students’ exposure to diverse perspectives (Celik et al., 2022; Nikiforos et al., 2020).

It is crucial for higher education institutions to take an active role in defining the usage and scope of AI in education for international students. By carefully evaluating the potential benefits and risks of this technology, universities can develop theories and models that support the implementation of AI in a way that maximizes its benefits for all students and improves the educational experience (Chen et al., 2020a).

2. What Is Artificial Intelligence?

Though artificial intelligence/AI is a “hot topic” today, few know what exactly is meant by this term. While discussions and examples in this paper will help readers understand what AI is and is not, it is important to provide a definition that will orient readers to the perspective of this paper. To this end, we draw inspiration from Russell’s (2010) work defining AI as constructing or reconstructing intelligence. Humans have intelligence, which has developed organically through biology and evolution, and includes reasoning, logic, problem-solving, and other cognitive abilities. Artificial intelligence seeks to replicate this intelligence for narrow or broad purposes. For example, if a device were created to enable a dog to think like a human, that would be an artificial creation of intelligence. However, AI is most frequently associated with digital technology that enables computers to perform tasks that previously required a human operator.

This paper examines the current applications of AI in education, its potential to support international students, and future “large-scale AI applications” that could significantly transform education services. The term “large-scale AI applications” refers to innovations in AI that may take years or decades to develop but have the potential to impact education services dramatically. In contrast, the current applications of AI discussed in this paper are innovations that are already available or in development, for which the impact is more limited, or some of the pressing ethical and adoption concerns have already been addressed.

3. Growth in the Number of International Students

Student mobility has been a global phenomenon for many years, but it wasn’t until the 21st century that the number of students studying abroad increased significantly. In recent decades, there has been a substantial rise in the number of students who pursue their education in a foreign country, known as “internationally mobile students.” According to the definition provided by International Students (2023), internationally mobile students are individuals who leave their home country and relocate to a different country to participate in educational activities.

Historically, it has been approximated that over 90% of international students are registered in countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Verbik & Lasanowski, 2007). The so-called “international student market” has garnered much attention due to the increased number of internationally mobile students. As a result, various nations have implemented assertive policies to shift from countries that send students abroad to countries that attract international students, which has further contributed to the rise in the total number of students studying abroad (Ding, 2016). OECD (2022) reports that students increasingly cross international boundaries to pursue higher education and progress through academic stages. Interestingly, only a small percentage of students fall under the category of “internationally mobile,” with OECD reporting that, on average, they constitute just 5% of bachelor’s degree students, 14% of master’s degree students, and 24% of doctoral students in OECD countries (OECD, 2022, p. 218). Despite this, the impact of international students on higher education and the economy cannot be ignored, making it a topic of continued interest and study.

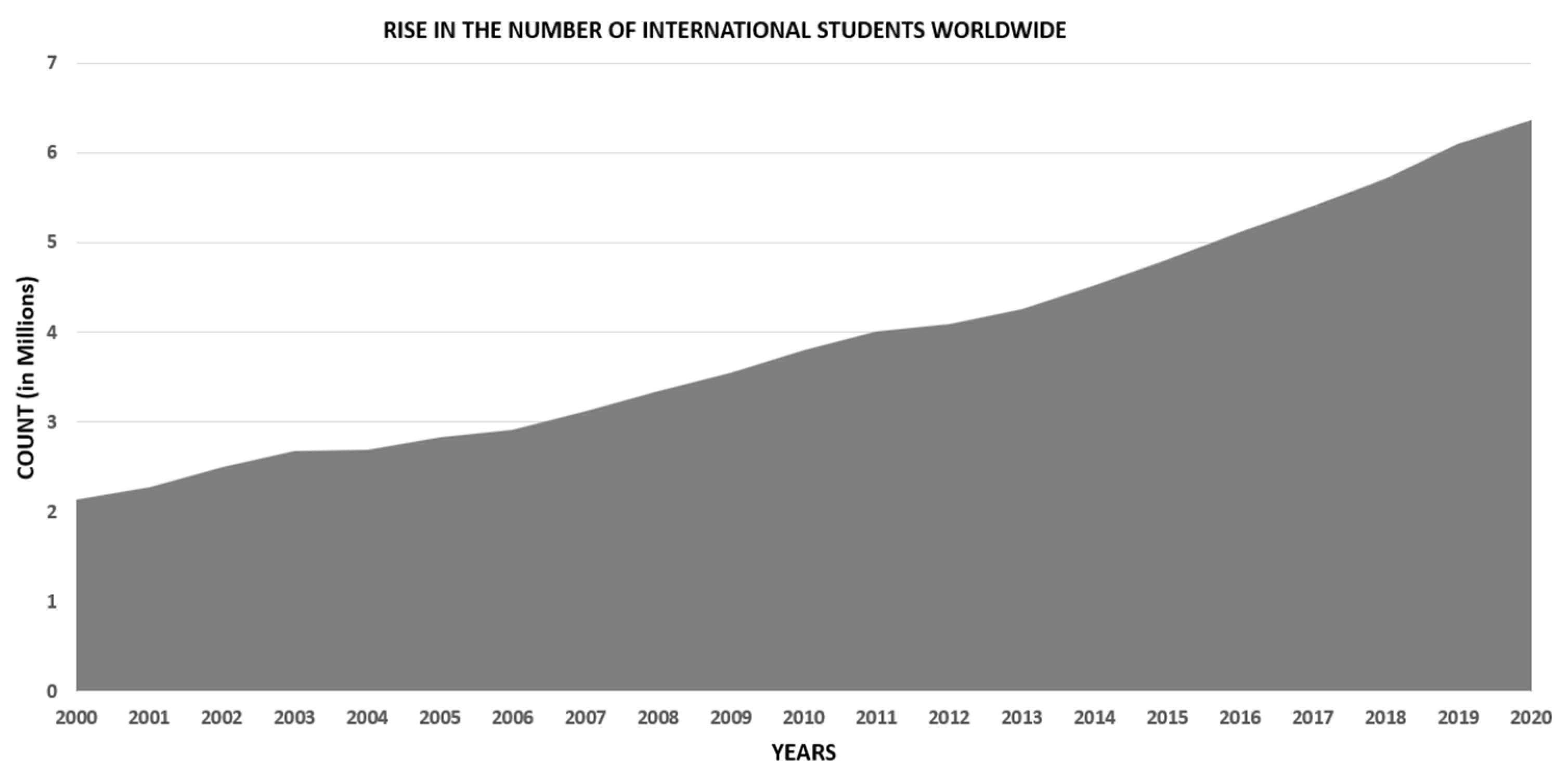

Furthermore, Ding (2016) cites the OECD’s report, which indicates that the number of students registered outside their country of citizenship has risen significantly from 2.1 million in 2000 to 4.3 million in 2011 and, most recently, to 6.3 million in 2020 (UIS Statistics, 2023) (refer to

Figure 1, where data is only available until 2020). This represents an approximate 200% increase in international students from 2000 to 2020, suggesting that the trend of international student mobility will continue to proliferate in the coming years.

4. Unique Needs of These Students

The increasing number of international students has spurred countries to develop innovative strategies to attract even more students. Traditionally, international students have moved from less developed to more developed countries, with North America and Europe being the most popular destinations (Yin & Zong, 2022). However, a student’s decision to attend a particular institution or country for their academic pursuits is influenced by a wide range of variables. Mazzarol and Soutar (2002) note that the motives behind international students’ decisions to study abroad are determined by “push-pull factors.” Push factors encourage and influence students to move away from their home country, while pull factors attract individuals to a particular host country. Pull factors can include familiarity with the institution or country, the cost of living, the local environment, social connections, and more (Wintre et al., 2015).

Research on international student migration has identified various factors that motivate students to study abroad. King and Sondhi (2018) found that primary motivators are the desire to attend a prestigious or innovative university and obtain an international education to establish a successful career in the global marketplace. Binsardi and Ekwulugo (2003) similarly found that students are inspired by the opportunities for employment, lifestyle advancement, and recognition that come with earning a degree from an international institution. A thematic analysis conducted by Wintre et al. (2015) identified “learning and educational experiences,” “qualities and characteristics of the universities,” such as program variety and prestige, and “future career prospects” as the most commonly cited reasons for choosing to study abroad. Financial benefits and filling skills gaps in technology-related employment (Choudaha, 2017) and a desire to improve language skills and learn about other cultures (Sánchez et al., 2006) are also contributing factors.

However, international students face numerous challenges when studying abroad. Dillon and Swann (1997) noted that a significant area of concern for international students is a loss of confidence in their language abilities, one of the most intimidating obstacles to a positive transition experience. Butcher and McGrath (2004) identified several challenges and academic needs of international students, including language proficiency, understanding instructions, completing assignments, conducting research, participating in discussions, and keeping pace with the rest of the class. Addressing these challenges and meeting the academic needs of international students is essential for ensuring their success and improving the overall international student experience.

The key drivers behind international student migration are providing students with a high-quality education and meeting their learning-related needs. As such, universities and colleges must focus on developing and implementing effective academic methods that incorporate the latest technological advancements to improve the overall educational experience for their students. In particular, the following sections will examine the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) applications in education and how they can help support international students by providing personalized learning experiences, adaptive testing, predictive analytics, and chatbots for learning and research. These AI innovations have the potential to revolutionize higher education and enhance the learning experience for international students, but it is important to carefully consider and address the potential risks and limitations associated with their use (Roll & Wylie, 2016).

5. Current Applications of AI in Education

Incorporating AI applications in education has the potential to revolutionize the learning experience for international students, as emphasized by Seldon and Abidoye (2018). There has been a significant increase in research on AI and education in recent years, as the practicality of this technology has rapidly evolved (Russell & Norvig, 2010). AI-powered tools can provide instructors with insights into how students respond to learning content and style, creating a more dedicated learning atmosphere for international students from diverse backgrounds. Additionally, AI-based learning can be tailored to develop the skills and abilities employers seek in learners, including those from different countries (Pokrivčáková, 2019). Specific examples of AI applications in education, such as personalized learning experiences, adaptive testing, predictive analytics, and chatbots for learning and research, will be examined in this section for their potential impact on international students.

AI can potentially improve learning value and efficiency through different computing technologies, such as intelligent education, innovative virtual learning, and data analysis and prediction (Chen et al., 2020b; Kahraman et al., 2010). Education administration for international students is a crucial area AI affects, including automated processes and tasks, curriculum and content development, and teaching and learning processes (such as reviewing assignments, grading, and providing feedback) (Chen et al., 2020b). Interactive Learning Environments platforms such as AI-assisted ACTIVE Math, MATHia, and Why2Atlas have been implemented to manage learning achievements, track performance, improve teaching tools, and support communication and feedback between instructors and international learners of different levels and subjects (Chassignol et al., 2018). AI-powered applications like Grammarly, Ecree, and PaperRater offer plagiarism detection, grading, and writing improvement, among other administrative functions that can benefit international students (Chen et al., 2020b).

The utilization of learner-centered AI applications, such as Deep Tutor and Auto Tutor, has been shown to cultivate custom and personalized content based on the international learners’ ability and requirements, thereby enhancing the learning experience and potentially leading to more successful learning outcomes for international students (Rus et al., 2013). Furthermore, the emergence of online learning has enabled AI to develop improved instructional tools for instructors and to transcend geographic boundaries, resulting in international students having the opportunity to optimize their learning outcomes by utilizing AI-powered language translators such as Google Translate (Mikropoulos & Natsis, 2011; Sharma et al., 2019). In a study of Chinese college students’ English learning, Tsai (2019) confirmed that Google translate had a positive impact in helping international students use advanced-level words and reduce spelling and grammatical errors. The international students are also satisfied with the experience of using Google translate for English writing to find and improve their proficiency in English writing. Further, Gamification, integrated with Virtual Reality and 3D technologies and aimed at instruction, has positively impacted teaching quality and efficiency for international students (Lee & Hammer, 2011; Le et al., 2013).

Several studies point to the benefits of AI for learning experiences for international students. Chassignol et al. (2018) discussed the applications such as Knewton, Cerego, Immersive reader, and CALL could provide international students with real-time recommendations based on machine learning algorithms to tailor course materials to meet learners’ needs, improve learning experience from early childhood education to graduate school. Pokrivakova (2019) further confirmed that chatbots using machine learning algorithms AI could improve students’ learning experience by customizing learning content based on their needs and capabilities. AI-based revision and writing assistants, such as Pearson’s Write-to-Learn and Turnltln, are also used to encourage academic integrity (Sutton, 2019; Wu, 2015). However, Crowe et al. (2017) argued that the tools could lead students to use paper mill websites or platforms, encouraging dishonest behavior and jeopardizing academic integrity.

For international students whose native language is not English studying in English-speaking countries, AI-powered translator and writing tools, voice recognition and dictation tools, and language learning tools can assist their learning. For example, besides Google Translator, Grammarly, a writing support application, facilitates academic writing for international students, faculties, and researchers (Galn et al., 2019; O’Neill & Russell, 2019; Pratama, 2020). Similar tools, such as ProWritingAid, Quillbot, and Ginger, also positively impact English as foreign language students in English academic writing (Erkan, 2022; Nurmayanti & Suryadi, 2023; Tran & Nguyen, 2021).

In addition to academic writing skills, listening and oral skills are equally critical for international students. Holmes (2004) highlighted that international students often need more effort than native-English-speaker peers to achieve higher academic achievement due to their lack of discussion skills, lower listening skills for long lectures, and unfamiliarity with the instructors’ accents, humor, and examples. Many AI English voice chat applications have been developed recently with diverse goals. For instance, instructors can use ELIZA and ALICE chatbots to allow students to check grammar errors and incorrectly used words. Andy and Mondly interpret sentences’ meaning and provide appropriate answers, and can be recommended for individuals who want to practice more complex sentences (Kim et al., 2019). Based on empirical research, AI voice chatbots have been approved to positively impact students’ English communication ability by enriching language input and expanding interaction. Also, chatbots increase students’ English learning motivation, self-confidence, and interest in learning (Junaidi et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2019).

Several general AI languages learning apps and platforms, such as Duolingo and Rosetta Stone, offer personalized interactive lessons, exercises and quizzes, and feedback to help learners improve their vocabulary, grammar, and oral skills (Alhabbash et al., 2016). However, despite their potential, AI English learning applications are limited in their ability to interact with humans, replicate cultural and contextual differences in language, understand or produce creative or original language, and recognize errors (de la Vall & Araya, 2023).

6. Applications for Academic Libraries

Current AI applications in education have the potential to transform academic libraries significantly. Cox et al. (2019) suggest that AI could impact various aspects of libraries, including search and recommendation systems, personalization, text and data mining, and analytics. Such technologies could enhance user experiences and the overall functionality of library spaces.

Although there is some hesitancy in academia regarding AI adoption, research by Lund et al. (2020) indicates that academic librarians are generally receptive to integrating AI into their operations. They are often early adopters of new information and communication technologies. The study by Lund et al. (2020) also reveals that librarians are interested in incorporating AI in reference services, cataloging, and improved library search.

Yoon et al. (2022) note that AI has become a reliable substitute for some human services, assisting in various user services. Gujral et al. (2019) discuss specific roles and applications of AI in academic libraries, including data curation for collection management and digital preservation and navigating new information environments to better understand the scholarly communication landscape. By automating certain tasks, AI can improve librarians’ productivity and efficiency.

One common example of AI in libraries is chatbots. Cox et al. (2019) highlight the benefits of chatbots, such as 24/7 availability, consistency, and patience in answering queries. AI also has the potential to offer personalized assistance and targeted services to students, faculty, and staff. It could help users find relevant resources quickly and efficiently while simultaneously analyzing user behavior to retrieve the most useful materials.

AI’s potential impact on academic libraries extends beyond patron assistance; it could also optimize the library’s daily operations. By automating routine tasks like cataloging, shelving, and book sorting, librarians could devote more time to research assistance, outreach, and programming. AI could also aid in digitizing library collections, improving accuracy and speed in retrieval methods. This would save resources and time by reducing the need for physical storage space and manual labor for organizing and maintaining collections.

7. Large-Scale AI Applications in the Future of Education

This section will discuss four examples of large-scale AI applications for education: personalized learning experiences, adaptive learning, predictive analytics, and chatbots for learning and research. Each of these four innovations can be seen as a longer-term application of AI, though some have already reached technological feasibility through developments such as large language models like ChatGPT (Lund & Wang, 2023). However, the feasibility of using these technologies to revolutionize higher education will only improve in years to come.

Personalized learning experiences use AI to create customized learning content that caters to the learner’s background and abilities, ensuring relevance (Chaipidech et al., 2022; Furini et al., 2022). This innovation has the potential to challenge learners in their zone of proximal development while also providing culturally relevant examples that are beneficial for international students (Ballard & Butler, 2011). However, such a learning design would impact the instructional design considerations on the part of the educator, where the AI would design learning experiences (lightening the load on the educator) but would necessitate greater oversight for each student (increasing the need for personalized assistance) (Vandewaetere & Clarebout, 2014).

Consider two learners: one is an international student from India, and the other is a domestic student at a US university. Both could receive assignments on a common topic, such as the political theory of democracy, but with more relevant examples of their background and experience. Democracies may look different in different countries, and providing such personalized learning experiences can enhance their understanding. Additionally, there may be students from various disciplinary backgrounds, such as journalism and teaching majors, within the political science class. Examples of the political theory of democracy framed within the lens of these disciplines may better equip students with relevant knowledge. Finally, it may be possible to have undergraduate and graduate students in the same course, or majors and non-majors, where the challenge of the content can be reflective of the differences in these students, their current position as a student, and their future goals.

Adaptive testing would allow for a more meaningful understanding of students’ abilities and enhance the feedback provided to students (Conejo et al., 2004; Mujtaba & Mahapatra, 2020). The complexity of questions could vary based on responses to prior questions to more fully assess the knowledge and abilities of the student (Wainer et al., 2000; Weiss & Kingsbury, 1984). Different aspects of the question could be evaluated separately, such as syntax and vocabulary in a writing sample. The ability to apply knowledge in disciplines or professions relevant to the student (such as journalism versus education) could be assessed. This functionality would allow educators and future employers to understand students holistically and prospective employees’ strengths and weaknesses in various areas rather than just broad areas, like with standard entrance exams like the SAT/ACT and GRE (Gershon, 2005). Additionally, it could allow test questions to be tailored to students’ language abilities and cultural context (Chalhoub-Deville & Deville, 1999).

Consider two learners again: one is an undergraduate journalism major, and the other is a doctoral-level literature major. These two learners come from vastly different academic backgrounds, and the assessment of their learning should reflect this diversity. In order to more accurately evaluate their abilities and knowledge, it is crucial to assess these students differently and understand whether they can apply course knowledge to their unique disciplinary contexts. Adaptive testing could be a powerful tool to help achieve this goal.

Adaptive testing would enable educators to adjust the complexity of questions based on the student’s responses, providing a more nuanced and accurate assessment of their higher-order thinking skills. For example, the undergraduate journalism major may need to demonstrate their ability to apply political theory concepts to real-world situations, while the doctoral level literature major may need to demonstrate their ability to analyze and critique political theory literature. Adaptive testing could allow both students to be assessed at a complexity level appropriate for their academic level and disciplinary background.

Predictive or learning analytics can transform how educators and administrators understand and support students’ academic performance. Using data to identify patterns and trends in student behavior and performance, predictive analytics can provide insights that enable educators to intervene early and effectively when students are struggling (Clow, 2013; Siemens, 2013). For example, one application of predictive analytics is using early warning systems to identify students at risk of falling behind or dropping out (Doleck, 2020). By analyzing data such as attendance, grades, and course completion rates, these systems can identify students needing additional support or intervention before their academic performance deteriorates (Viberg et al., 2018). This could help educators provide timely and targeted support to at-risk students, potentially improving their chances of success (De Freitas et al., 2015).

Universities could also use analytics to identify factors that contribute to the success of international students, such as language proficiency, cultural background, and socio-economic status (Umer et al., 2021). This information could be used to develop more effective support programs tailored to international students’ needs. This could improve the quality of support provided to international students and make it more cost-efficient, as universities could focus resources on the most effective interventions (Attaran et al., 2018).

We have already seen some of the applications of chatbots for learning and research through language models like ChatGPT. Chatbots come with significant concerns about academic integrity, but when used properly, they provide timely support to students struggling with coursework (Perkins, 2023). For example, they can provide personalized feedback on writing tasks and assist with navigational and technological issues within a course. They could also translate instructions from a professor so that they may be better understood by learners for whom English is a secondary language.

Consider an international student navigating a new academic environment in a foreign country while balancing cultural and language differences. With these added challenges, student needs access to resources that can help them succeed academically. For example, if the student is struggling with a particular topic or assignment, a chatbot can provide a helpful tool for the student to receive immediate and accurate responses to their questions. Although the chatbot cannot replace a professor’s valuable expertise and guidance, it can serve as a complementary resource for the student to use until they can connect with their professor during office hours. Using a chatbot allows international students to maximize their learning potential and stay on track with their studies, even with limited access to their professor due to language or cultural barriers. Additionally, the chatbot can provide a quick and efficient means of obtaining information, and in some cases, the chatbot may also be able to direct the student to relevant resources or suggest possible solutions to complex problems.

When referring to personalized learning experiences or adaptive learning and the role of academic libraries, consider a student needing to view written materials which are visually impaired. AI has the potential to make library resources and services more accessible for users with disabilities, including visual impairment, by providing real-time transcriptions, translations, and audio descriptions. Furthermore, AI could offer text-to-speech tools to create audio versions of written materials. Accessibility tools (that are more commonly known) like text-to-speech, image recognition, voice-activated interfaces, electronic braille displays, and automatic translations could happen within a moment for the student.

Consider a neurodivergent student navigating the various resources found at the library. AI could analyze a student’s reading habits and preferences to recommend materials tailored to him/her. Also, AI could offer an alternative to traditional learning methods. Accessibility tools like sensory support, chatbots, virtual assistants, and personalized recommendations would offer patrons a whole new realm of helpful methods. This would allow for fewer barriers and help students (also faculty and staff) engage with library resources that fit their learning styles and accommodations. Inclusivity and accessibility in academic libraries would be forever and ultimately changed for the better.

8. Limitations and Concerns about These AI Applications

Of course, significant risks and limitations are associated with educational, and technological innovations that specifically impact international students. For example, personalized learning experiences may raise privacy and security concerns for these students, as using data to tailor learning experiences may require collecting personal information that could be subject to regulations in their home countries (Bulger, 2016). Additionally, there may be cultural factors that impact how personal information is shared or used, which must be taken into consideration.

Adaptive testing can also present risks for international students, particularly concerning language proficiency. For example, using algorithms to determine the complexity of questions may not accurately reflect a student’s language skills or ability to comprehend nuanced phrasing. This could result in biased test results that do not fully capture the student’s abilities or knowledge (Wang & Kolen, 2001).

Predictive analytics in education may also have ethical implications for international students. For example, identifying students at risk of dropping out or struggling may require the use of data that is not relevant or applicable to international students, leading to inaccurate or misleading predictions. There is also a risk that the data used to make predictions could be subject to different privacy laws or regulations in their home countries (Slade & Prinsloo, 2013).

Finally, using chatbots in learning and research can raise concerns about language barriers and cultural differences that may impact the quality and accuracy of the information provided (Lund et al., 2023). For example, international students may have different needs or require more personalized assistance, and chatbots may not always be able to provide the level of support necessary. Additionally, there may be cultural differences in how students perceive the role of educators and their expectations for feedback and guidance.

9. Discussion

As the enrollment of international students in higher education continues to rise, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in education presents new opportunities to meet these students’ unique needs and challenges. However, universities must take an active role in defining the usage and scope of AI to ensure that it benefits all students and improves the educational experience. This requires careful consideration of privacy, security concerns, cultural differences, and language barriers. Universities can also ensure that AI is used culturally sensitively and considers students’ individual needs.

One way universities can ensure that AI is used to its full potential is by taking an active role in defining the usage and scope of the technology (Pagano, A., Marengo, A., 2021). By doing so, higher education institutions can carefully weigh the risks and rewards of AI and determine how it can be best used to support their students’ needs.

While AI can revolutionize education for international students, some potential risks and limitations must be considered (Alam, 2021). AI-powered tools may struggle with accents and dialects or provide a narrow view of language and culture, limiting students’ understanding of diverse perspectives. Therefore, institutions must strike a balance between using AI to enhance the educational experience and preserving the critical role of human educators in supporting students’ academic and personal growth.

AI is not a substitute for the expertise and guidance of human educators (Chen et al., 2022; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). Even with the potential benefits of AI in education for international students, it is crucial to recognize that it is not a panacea. AI can provide valuable support and guidance, but it cannot replace the critical role of human educators in supporting students’ academic and personal growth. Therefore, higher education institutions must balance using AI to enhance the educational experience and preserving the critical role of human educators in supporting students.

The development of AI applications for education has significant implications for international students, and institutions of higher education must carefully consider the opportunities and risks associated with their implementation (AlDhaen, 2022; Ghotbi et al., 2022; Yang & Evans, 2019). It is imperative to acknowledge that AI is not a one-size-fits-all solution and that it must be implemented in ways that align with international students’ unique needs and cultural differences. By doing so, universities can work towards providing a more inclusive, accessible, and practical educational experience for all students, regardless of their background or circumstances. Ultimately, institutions must approach AI in education as a tool that can enhance, not replace, the important role of human educators in supporting and guiding international students through their academic journeys.

As the field of AI in education continues to evolve, there is a need for further research to understand how AI can be most effectively used to support international students’ learning and success. Universities and researchers must continue to work together to develop and implement innovative approaches that cater to the unique needs of international students. The development of AI applications for education has significant implications for international students, and institutions of higher education must carefully consider the opportunities and risks associated with their implementation.

10. Conclusions

The development of AI applications for education has significant implications for international students, and higher education institutions must work towards maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks associated with their implementation. This paper has explored the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on the education of international students and how it can be used to improve various aspects of educational administration, curriculum development, teaching, and learning processes. The rise of international student migration has increased the need for innovative educational approaches, and AI provides a promising solution. By providing personalized and adaptive learning opportunities to international students, AI can enhance the overall quality of education. However, weighing the limitations and potential risks associated with using AI in education, such as language barriers and cultural differences, is crucial.

AI in education is an emerging field with vast potential for supporting international students in their academic journey. It is crucial to balance the risks and rewards of this technology and ensure that it is implemented to benefit all students and improve the educational experience. The future of education for international students is exciting, with AI set to play a critical role in enhancing learning and improving educational outcomes. Therefore, higher education institutions should continue researching and developing AI applications to provide a more inclusive, accessible, and practical educational experience for all students, regardless of their background or circumstances. With careful consideration and implementation, AI has the potential to revolutionize education for international students and support their academic success.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Alam, A. Possibilities and apprehensions in the landscape of artificial intelligence in education. International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Computing Applications, 2021, 1-8.

- AlDhaen, F. The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education–Systematic Review. In M. Aliaali (Eds.), COVID-19 Challenges to University Information Technology Governance, 2022, pp. 269–285. Spring Nature. [CrossRef]

- Alhabbash, M., Mhadi, A. O., & Abu-Naser, S. S. An intelligent tutoring system for teaching grammar English tenses. European Academic Research, 2016, 4(9), 7743-7757.

- Attaran, M., Stark, J., & Stotler, D. Opportunities and challenges for big data analytics in US higher education: A conceptual model for implementation. Industry and Higher Education, 2018, 32(3), 169-182. [CrossRef]

- Ballard, J., & Butler, P. Personalised learning: Developing a Vygotskian framework for e-learning. International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society,2011, 7(2), 21-36. [CrossRef]

- Binsardi, A., & Ekwulugo, F. International marketing of British education: research on the students’ perception and the UK market penetration. 2003. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 21(5), 318-327. [CrossRef]

- Bulger, M. Personalized learning: The conversations we’re not having. Data and Society. 2016. Retrieved from https://datasociety.net/library/personalized-learning-the-conversations-were-not-having/.

- Butcher, A., & McGrath, T. International Students in New Zealand: Needs and Responses. International Education Journal, 2004, 5(4), 540–551.

- Celik, I., Dindar, M., Muukkonen, H., & Järvelä, S. The promises and challenges of artificial intelligence for teachers: A systematic review of research. TechTrends, 2022. 66(4), 616-630. [CrossRef]

- Chaipidech, P., Srisawasdi, N., Kajornmanee, T., & Chaipah, K. A personalized learning system-supported professional training model for teachers’ TPACK development. 2022. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, article 100064. [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub-Deville, M., & Deville, C. Computer adaptive testing in second language contexts. 1999. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 19, 273-299. [CrossRef]

- Chassignol, M., Khoroshavin, A., Klimova, A., & Bilyatdinova, A. Artificial Intelligence trends in education: a narra-tive overview. 2018. Procedia Computer Science, 136, 16-24. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Chen, P., & Lin, Z. Artificial intelligence in education: A review. 2020a. IEEE Access, 8, 75264-75278. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Xie, H., Zou, D., & Hwang, G. J. Application and theory gaps during the rise of artificial intelligence in edu-cation. 2020. Computers in Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1, article 100002. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Zou, D., Xie, H., Cheng, G., & Liu, C. Two decades of artificial intelligence in education. 2022. Educational Technol-ogy and Society, 25(1), 28-47.

- Choudaha, R. Three waves of international student mobility (1999–2020). 2017. Studies in Higher Education, 42(5), 825–832. [CrossRef]

- Clow, D. An overview of learning analytics. 2013. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(6), 683-695. [CrossRef]

- Conejo, R., Guzman, E., Millan, E., Trella, M., Perez-de-la-Cruz, J., & Rios, A. SIETTE: A web-based tool for adaptive testing. 2004. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 14(1), 29-61.

- Cox, A. M., Pinfield, S., & Rutter, S. The intelligent library: Thought leaders’ views on the likely impact of artificial intelligence on academic libraries. 2019. Library Hi Tech, 37(3), 418-435. [CrossRef]

- Crowe, D., LaPierre, M., & Kebritchi, M. Knowledge based artificial augmentation intelligence technology: Next step in academic instructional tools for distance learning. 2017. TechTrends, 61(5), 494-506. [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, S., Gibson, D., Du Plessis, C., Halloran, P., Williams, E., Ambrose, M., Dunwell, I., & Arnab, S. Foundations of dynamic learning analytics: Using university student data to increase retention. 2015. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(6), 1175-1188. [CrossRef]

- De la Vall, R. R. F., & Araya, F. G. Exploring the Benefits and Challenges of AI-Language Learning Tools. 2023. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention, 10(01), 7569-7576. [CrossRef]

- Dillon, R. K., & Swann, J. S. Studying in America: Assessing How Uncertainty Reduction and Communication Satis-faction Influence International Students’ Adjustment to US Campus Life. 1997.

- Ding, X. Exploring the Experiences of International Students in China. 2016. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(4), 319–338. [CrossRef]

- Doleck, T., Lemay, D. J., Basnet, R. B., & Bazelais, P. Predictive analytics in education: A comparison of deep learning frameworks. 2020. Education and Information Technology, 25, 1951-1963. [CrossRef]

- Erkan, Y. Ü. C. E. The immediate reactions of EFL learners towards total digitalization at higher education during the Covid-19 pandemic. 2022. Journal of Theoretical Educational Science, 15(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Furini, M., Gaggi, O., Mirri, S., Montangero, M., Pelle, E., Poggi, F., & Prandi, C. Digital twins and artificial intelli-gence: As pillars of personalized learning models. 2022. Communications of the ACM, 65(4), 98-104. [CrossRef]

- Gershon, R. C. Computer adaptive testing. 2005. Journal of Applied Measurement, 6(1), 109-127.

- Ghotbi, N., Ho, M. T., & Mantello, P. Attitude of college students towards ethical issues of artificial intelligence in an international university in Japan. 2022. AI & Society, 37, 283-290. [CrossRef]

- Gujral, G., Shivarama, J., & Choukimath, P. A. Perceptions and prospects of artificial intelligence technologies for ac-ademic libraries: An overview of global trends. 2019. 12th International CALIBER, 79-88.

- Holmes, P. Negotiating differences in learning and intercultural communication: Ethnic Chinese students in a New Zealand university. 2004. Business Communication Quarterly, 67(3), 294-307. [CrossRef]

- International students. 2023, March 3. Migration Data Portal. https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/international-students.

- Jiang, T., Li, W., Wang, J., & Wang, X. Using Artificial Intelligence-based Online Translation Website to improve the Health Education in International Students. 2021, June. In 2021 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Education (ICAIE), 25-28.

- Junaidi, J. Artificial intelligence in EFL context: rising students’ speaking performance with Lyra virtual assistance. 2020. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology Rehabilitation, 29(5), 6735-6741.

- Kahraman, H. T., Sagiroglu, S., & Colak, I. Development of adaptive and intelligent web-based educational systems. 2010, October. 2010 4th International Conference on Application of Information and Communication Technologies, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. Y., Cha, Y., & Kim, H. S. Future English learning: Chatbots and artificial intelligence. 2019. Multimedia-Assisted Language Learning, 22(3), 32-53.

- King, R., & Sondhi, G. International student migration: A comparison of UK and Indian students’ motivations for studying abroad. 2018. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 16(2), 176–191. [CrossRef]

- Le, N. T., Strickroth, S., Gross, S., & Pinkwart, N. A review of AI-supported tutoring approaches for learning pro-gramming. 2013. Advanced Computational Methods for Knowledge Engineering, 267-279. 40. Lee, J. J., & Hammer, J. Gamification in education: What, how, why bother? 2011. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 15(2), 146.

- Lehman-Wilzig, S. (2001). Babbling our way to a new Babel: Erasing the language barriers. The Futurist, 35(3), 16.

- Lund, B. D., Omame, I., Tijani, S., & Agbaji, D. Perceptions toward artificial intelligence among academic library em-ployees and alignment with the diffusion of innovations’ adopter categories. 2020. College & Research Libraries, 81(5), 865. [CrossRef]

- Lund, B. D., & Wang, T. Chatting about ChatGPT: How may AI and GPT impact academia and libraries? 2023. Library Hi Tech News. [CrossRef]

- Lund, B. D., Wang, T., Mannuru, N. R., Nie, B., Shimray, S., & Wang, Z. ChatGPT and a new academic reality: AI-written research papers and the ethics of the large language models in scholarly publishing. 2023. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. L., & Wright, K. E. Bias in Automatic Speech Recognition: The Case of African American Language. 2022. Applied Linguistics, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Mazzarol, T., & Soutar, G. N. ‘‘Push-pull’’ factor influencing international student destination choice. 2002. International Journal of Educational Management, 16, 82–90. [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z., Heldreth, C., Lahav, M., Sublewski, J., & Tuennerman, E. “I don’t Think These Devices are Very Cultur-ally Sensitive.”—Impact of Automated Speech Recognition Errors on African Americans. 2021. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 4, 169. [CrossRef]

- Mikropoulos, T. A., & Natsis, A. Educational virtual environments: A ten-year review of empirical research (1999–2009). 2011. Computers & Education, 56(3), 769-780. [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, D. F., & Mahapatra, N. R. Artificial intelligence in computerized adaptive testing. 2020. 2020 International Con-ference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence. [CrossRef]

- Nikiforos, S., Tzanavaris, S., & Kermanidis, K. L. Virtual learning communities (VLCs) rethinking: influence on be-havior modification—bullying detection through machine learning and natural language processing. 2020. Journal of Computers in Education, 7, 531-551. [CrossRef]

- Niyozalievna, K. I. To develop students’ writing skills in teaching English. 2022. Web of Scientist: International Scientific Research Journal, 3(02), 113-119.

- Nurmayanti, N., & Suryadi, S. The Effectiveness Of Using Quillbot In Improving Writing For Students Of English Education Study Program. 2023. Jurnal Teknologi Pendidikan: Jurnal Penelitian dan Pengembangan Pembelajaran, 8(1), 32-40. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, R., & Russell, A. Stop! Grammar time: University students’ perceptions of the automated feedback program Grammarly. 2019. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(1), 42-56. [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators. 2022. OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F., & Jiao, P. Artificial intelligence in education: The three paradigms. 2021. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100020. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A., Marengo, A. Training Time Optimization through Adaptive Learning Strategy. 2021. 2021 International Con-ference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies, pp. 563–567. [CrossRef]

- Parra G, L., & Calero S, X. Automated writing evaluation tools in the improvement of the writing skill. 2019. International Journal of Instruction, 12(2), 209-226. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M. Academic integrity considerations of AI large language models in the post-pandemic era: ChatGPT and beyond. 2023. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 20(2). [CrossRef]

- Pokrivčáková, S. Preparing teachers for the application of AI-powered technologies in foreign language education. 2019. Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 7(3), 135-153. [CrossRef]

- Pratama, Y. D. The investigation of using Grammarly as online grammar checker in the process of writing. 2021. English Ideas: Journal of English Language Education, 1(2), 46-54.

- Roll, I., & Wylie, R. Evolution and revolution in artificial intelligence in education. 2016. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26, 582-599. [CrossRef]

- Rus, V., D’Mello, S., Hu, X., & Graesser, A. Recent advances in conversational intelligent tutoring systems. 2013. AI maga-zine, 34(3), 42-54. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S. J., & Norvig, P. Artificial intelligence: A modern approach. 2010. Prentice Hall.

- Sánchez, C. M., Fornerino, M., & Zhang, M. Motivations and the Intent to Study Abroad Among U.S., French, and Chinese Students. 2006. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 18(1), 27–52. [CrossRef]

- Seldon, A., & Abidoye, O. The Fourth Education Revolution. 2018. London, UK: University of Buckingham Press.

- Sharma, R. C., Kawachi, P., & Bozkurt, A. The landscape of artificial intelligence in open, online and distance educa-tion: Promises and concerns. 2019. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 1-2.

- Siemens, G. Learning analytics: The emergence of a discipline. 2013. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(10), 1380-1400. [CrossRef]

- Slade, S., & Prinsloo, P. Learning analytics: Ethical issues and dilemmas. 2013. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(10), 1510-1529. [CrossRef]

- Sutton, H. Minimize online cheating through proctoring, consequences. 2019. Recruiting & Retaining Adult Learners, 21(5), 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Tran, T. M. L., & Nguyen, T. T. H. The impacts of technology-based communication on EFL students’ writing. 2021. AsiaCALL Online Journal, 12(5), 54-76.

- Tsai, S. C. Using google translate in EFL drafts: a preliminary investigation. 2019. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(5-6), 510-526. [CrossRef]

- UIS Statistics. Education: Inbound Internationally Mobile Students by Continent of Origin. 2023. http://data.uis.unesco.org/#. Accessed 20 March 2023.

- Umer, R., Susnjak, T., Mathrani, A., & Suriadi, L. Current stance on preditive analytics in higher education: Opportu-nities, challenges and future directions. 2021. Interactive Learning Environments. [CrossRef]

- Vandewaetere, M., & Clarebout, G. Advanced technologies for personalized learning, instruction, and performance. 2014. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Verbik, L., & Lasanowski, V. International Student Mobility: Patterns and Trends. 2007. World Education News and Re-views, 20(10), 1–16.

- Viberg, O., Hatakka, M., Balter, O., & Mavroudi, A. The current landscape of learning analytics in higher education. 2018. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 98-110. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., & Kolen, M. J. Evaluating comparability in computerized adaptive testing: Issues, criteria and an example. 2001. Journal of Educational Measurement, 38(1), 19-49. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D. J., & Kingsbury, G. G. Application of computerized adaptive testing to educational problems. 1984. Journal of Ed-ucational Measurement, 21(4), 361-375. [CrossRef]

- Wintre, M. G., Kandasamy, A. R., Chavoshi, S., & Wright, L. Are International Undergraduate Students Emerging Adults? Motivations for Studying Abroad. 2015. Emerging Adulthood, 3(4), 255–264. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. Research progress of humanoid robots for mobile operation and artificial intelligence. 2015. Journal of Harbin Insti-tute of Technology, 47(7), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., & Evans, C. Opportunities and challenges in using AI chatbots in higher education. 2019. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Education and E-Learning, 79-83. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X., & Zong, X. International student mobility spurs scientific research on foreign countries: Evidence from inter-national students studying in China. 2022. Journal of Informetrics, 16(1), 101227. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J., Andrews, J. E., & Ward, H. L. Perceptions on adopting artificial intelligence and related technologies in li-braries: public and academic librarians in North America. 2022. Library Hi Tech, 40(6), 1893-1915. [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O., Marin, V., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education: Where are the educators? 2019. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Educa-tion, 16(1), 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X., Chu, X., Chai, C. S., Jong, M. S. Y., Istenic, A., Spector, M., ... & Li, Y. A Review of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education from 2010 to 2020. 2021. Complexity, 2021, 1-18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).