Submitted:

10 May 2023

Posted:

11 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- 1)

- a reliable diagnosis of SARS-CoV2 infection obtained by RT-PCR molecular swab testing;

- 2)

- no history of pharmacological treatments responsible for alterations in the leukocyte count and/or CRP upon admission;

- 3)

- no current or past history of conditions responsible for alterations in the leukocyte count and/or CRP;

- 4)

- availability of at least three blood tests and blood gas analyses during hospitalization, and a hospitalization period not less than 48 hours.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| P/F | PaO2/FiO2 ratio |

| CAP | COMMUNITY acquired Pneumonia |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| V/Q | Ventilation/Perfusion |

References

- da Rosa Mesquita, R.; Francelino Silva, L. C., Jr.; Santos Santana, F. M.; Farias de Oliveira, T.; Campos Alcântara, R.; Monteiro Arnozo, G.; da Silva Filho, E. R.; Galdino dos Santos, A. G.; Oliveira da Cunha, E. J.; Salgueiro de Aquino, S. H.; Freire de Souza, C. D. Clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in the general population: systematic review. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift 2021, 133, 377-382. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Ji, P.; Pang, J.; Zhong, Z.; Li, H.; He, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C. Clinical characteristics of 3062 COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Journal of medical virology 2020, 92, 1902-1914. [CrossRef]

- Caramaschi, S.; Kapp, M. E.; Miller, S. E.; Eisenberg, R.; Johnson, J.; Epperly, G.; Maiorana, A.; Silvestri, G.; Giannico, G. A. Histopathological findings and clinicopathologic correlation in COVID-19: a systematic Review Modern Pathology 2021, 34(9), 1614-1633. [CrossRef]

- FORCE, ARDS Definition Task, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome JAMA 2012, 307(23), 2526-2533. [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, L.; Chiumello, D.; Caironi, P.; Busana, M.; Romitti, F.; Brazzi, L.; Camporota L. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med 2020, 46, 1099–1102. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Huang, S.; Yin, L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. Journal of medical virology 2021, 93, 250– 256. [CrossRef]

- Vaninov, N. In the eye of the COVID-19 cytokine storm. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 277. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xie, X.; Tu, Z.; Fu J.; Xu D.; Zhou Y. The signal pathways and treatment of cytokine storm in COVID-19 Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 2021, 6, 255. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shi L.; Wang Y.; Zhang J.; Huang L.; Zhang C.; Liu S.; Zhao P.; Liu H.; Zhu L. et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Lancet respiratory medicine 2020, 8, 420-422. [CrossRef]

- Ou, M.; Zhu, J.; Ji, P.; Li, H.; Zhong, Z.; Li, B.; Pang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, X. Risk factors of severe cases with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Epidemiology and infection 2020 148, e175. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, D.; Nee, S.; Hickey, N.S.; Marschollek M. Risk factors for Covid-19 severity and fatality: a structured literature review Infection 2021, 49, 15–28. [CrossRef]

- Clyne, B.; Olshaker, J.S. The C-reactive protein. J Emerg Med. 1999, 17(6), 1019-1025. [CrossRef]

- Zahorec R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, past, present and future perspectives. Bratislavske lekarske listy 2021, 122(7), 474–488. [CrossRef]

- Regolo, M.; Vaccaro, M.; Sorce, A.; Stancanelli, B.; Colaci, M.; Natoli, G.; Russo, M.; Alessandria, I.; Motta, M.; Santangelo, N.; et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) Is a Promising Predictor of Mortality and Admission to Intensive Care Unit of COVID-19 Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2235. [CrossRef]

- Sinatti, G.; Santini, S.J.; Tarantino, G.; Picchi G.; Cosimini B.; Ranfone F.; Casano N.; Zingaropoli M. A.; Iapadre N.; Bianconi S.; et al. PaO2/FiO2 ratio forecasts COVID-19 patients’ outcome regardless of age: a cross-sectional, monocentric study. Intern Emerg Med 2022, 17, 665–673. [CrossRef]

- Marini, J. J.; Gattinoni, L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress Jama 2020 323(22), 2329-2330. [CrossRef]

- Zanoli, L.; Briet, M.; Empana, J. P.; Cunha, P. G.; Mäki-Petäjä, K. M.; Protogerou, A. D.; Tedgui, A.; Touyz, R. M.; Schiffrin, E. L.; Association for Research into Arterial Structure, Physiology (ARTERY) Society, the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) Working Group on Vascular Structure and Function, and the European Network for Noninvasive Investigation of Large Arteries; et al. Vascular consequences of inflammation: a position statement from the ESH Working Group on Vascular Structure and Function and the ARTERY Society. Journal of hypertension 2020, 38(9), 1682–1698. [CrossRef]

- Zanoli, L.; Gaudio, A.; Mikhailidis, D. P.; Katsiki, N.; Castellino, N.; Lo Cicero, L.; Geraci, G.; Sessa, C.; Fiorito, L.; Marino, F.; et al. Vascular Dysfunction of COVID-19 Is Partially Reverted in the Long-Term. Circulation research 2022, 130(9), 1276–1285. [CrossRef]

- Pepys, M.B.; Hirschfield, G.M. C-reactive protein: a critical update [published correction appears in J Clin Invest. 2003 Jul;112(2):299]. J Clin Invest. 2003,111(12),1805-1812. [CrossRef]

- Gustine, J.N.; Jones, D. Immunopathology of Hyperinflammation in COVID-19. Am J Pathol. 2021, 191(1), 4-17. [CrossRef]

- Haverkate, F.; Thompson, S.G.; Pyke, S.D.; Gallimore, J.R.; Pepys, M.B. Production of C-reactive protein and risk of coronary events in stable and unstable angina. European Concerted Action on Thrombosis and Disabilities Angina Pectoris Study Group. Lancet 1997, 349(9050), 462-466. [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Rifai, N.; Rose, L.; Buring, J.E.; Cook, N.R. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347(20), 1557-1565. [CrossRef]

- Sproston, N.R.; Ashworth, J.J. Role of C-Reactive Protein at Sites of Inflammation and Infection. Front Immunol. 2018, 9:754. Published 2018 Apr 13. [CrossRef]

- Mold, C.; Gewurz, H.; Du Clos, T.W. Regulation of complement activation by C-reactive protein. Immunopharmacology 1999, 42(1-3), 23-30 . [CrossRef]

- Buono, C.; Come, C.E.; Witztum, J.L.; Maguire, G.F.; Connelly P.W.; Carroll, M.; Lichtman, A.H. Influence of C3 deficiency on atherosclerosis. Circulation 2002, 105(25), 3025-3031. [CrossRef]

- Ahnach, M.; Zbiri, S.; Nejjari, S.; Ousti, F.; Elkettani, C. C-reactive protein as an early predictor of COVID-19 severity Journal of medical biochemistry 2020, 39(4), 500–50. [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ma, Q.; Li, C.; Liu, R.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Gao, G.; Liu, F.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, C.; Xia, Y. Profiling serum cytokines in COVID-19 patients reveals IL-6 and IL-10 are disease severity predictors Emerging microbes & infections 2020, 9(1), 1123–1130 . [CrossRef]

- Tirelli, C.; De Amici, M.; Albrici, C.; Mira, S.; Nalesso, G.; Re, B.; Corsico, A.G.; Mondoni, M.; Centanni, S. Exploring the Role of Immune System and Inflammatory Cytokines in SARS-CoV-2 Induced Lung Disease: A Narrative Review. Biology 2023, 12, 177. [CrossRef]

- Lowery, S. A.; Sariol, A.; Perlman, S. Innate immune and inflammatory responses to SARS-CoV-2: Implications for COVID-19. Cell Host & Microbe 2021, 29(7), 1052-1062. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1038] [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1038]. Lancet 2020, 395(10229), 1054-1062. [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, D. M.; Kim-Schulze, S.; Huang, H. H.; Beckmann, N. D.; Nirenberg, S.; Wang, B.; Lavin, Y.; Swartz, T. H.; Madduri, D.; Stock, A.; et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nature medicine 2020, 26(10), 1636–1643. [CrossRef]

- Vorobjeva, N. V.; Chernyak, B. V. NETosis: molecular mechanisms, role in physiology and pathology. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2020, 85, 1178-1190. [CrossRef]

- González-Jiménez, P.; Méndez, R.; Latorre, A.; Piqueras, M.; Balaguer-Cartagena, M.N.; Moscardó, A.; Alonso, R.; Hervás, D.; Reyes, S.; Menéndez, R. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Platelet Activation for Identifying Severe Episodes and Clinical Trajectories in COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6690. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.C.; Liang, W.G.; Chen, F.W.; Hsu, J.H.; Yang, J.J.; Chang, M.S. IL-19 induces production of IL-6 and TNF-alpha and results in cell apoptosis through TNF-alpha. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, MD: 1950), 2002, 169(8), 4288–4297. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhong, L.; Deng, J.; Peng, J.; Dan, H.; Zeng, X.; Li, T.; Chen, Q. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. International Journal of Oral Science 2020, 12(1), 8–5. [CrossRef]

- Helal, M. A.; Shouman, S.; Abdelwaly, A.; Elmehrath, A. O.; Essawy, M.; Sayed, S. M.; Saleh, A,H.; El-Badri, N. Molecular basis of the potential interaction of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to CD147 in COVID-19 associated-lymphopenia. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 2022, 40(3), 1109-1119. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Ding, J.; Huang, Q.; Tang, Y. Q.; Wang, Q.; Miao, H. Lymphopenia predicts disease severity of COVID-19: a descriptive and predictive study. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2020, 5(1), 33. [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; Tian, D. S. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients with Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 2020 71(15), 762–768. [CrossRef]

- Petrie, H. T.; Klassen, L. W.; Kay, H. D. Inhibition of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in vitro by autologous peripheral blood granulocytes. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 1985, 134(1), 230-234. [CrossRef]

- El-Hag, A.; Clark, R. A. Immunosuppression by activated human neutrophils. Dependence on the myeloperoxidase system Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), 1987, 139(7), 2406-2413. [CrossRef]

- Cataudella, E.; Giraffa, C. M.; Di Marca, S.; Pulvirenti, A.; Alaimo, S.; Pisano, M.; Terranova, V.; Corriere, T.; Ronsisvalle, M. L.; Di Quattro, R.; Stancanelli, B.; Giordano, M.; Vancheri, C.; Malatino, L. Neutrophil-To-Lymphocyte Ratio: An Emerging Marker Predicting Prognosis in Elderly Adults with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2017, 65(8), 1796–1801. [CrossRef]

- Paliogiannis, P.; Fois, A. G.; Sotgia, S.; Mangoni, A. A.; Zinellu, E.; Pirina, P.; Negri, S.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, A. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and clinical outcomes in COPD: recent evidence and future perspectives. European respiratory review: an official journal of the European Respiratory Society, 2018, 27(147), 170113. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, X.; She, F.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhao, X. Effects of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Combined With Interleukin-6 in Predicting 28-Day Mortality in Patients With Sepsis Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 639735. [CrossRef]

- Cupp, M. A.; Cariolou, M.; Tzoulaki, I.; Aune, D.; Evangelou, E.; Berlanga-Taylor, A. J. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and cancer prognosis: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies BMC medicine 2020, 18(1), 360. [CrossRef]

- Afari, M. E.; Bhat, T. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and cardiovascular diseases: an update. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy 2016, 14(5), 573–577. [CrossRef]

- Buonacera, A.; Stancanelli, B.; Colaci, M.; Malatino, L. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio: An Emerging Marker of the Relationships between the Immune System and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3636. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A. P.; Liu, J. P.; Tao, W. Q.; Li, H. M. The diagnostic and predictive role of NLR, d-NLR and PLR in COVID-19 patients 2020, International immunopharmacology, 84, 106504. [CrossRef]

- Poggiali, E.; Zaino, D.; Immovilli, P.; Rovero, L.; Losi, G.; Dacrema, A.; Nuccetelli, M.; Vadacca, G. B.; Guidetti, D.; Vercelli, A.; Magnacavallo, A.; Bernardini, S.; Terracciano, C. Lactate dehydrogenase and C-reactive protein as predictors of respiratory failure in CoVID-19 patients. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry, 509 2020, 135–138. [CrossRef]

- Herold, T.; Jurinovic, V.; Arnreich, C.; Lipworth, B. J.; Hellmuth, J. C.; von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.; Klein, M.; Weinberger, T. Elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP predict the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2020, 146(1), 128–136.e4. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A. A.; Tamura, T.; Crowley, C. P.; DeGrado, J. R.; Haider, H.; Jezmir, J. L.; Keras, G.; Penn, E. H.; Massaro, A. F.; Kim, E. Y. Inflammatory Biomarker Trends Predict Respiratory Decline in COVID-19 Patients Cell reports. Medicine, 2020, 1(8), 100144. [CrossRef]

- Besutti, G.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; Ottone, M.; Spaggiari, L.; Canovi, S.; Monelli, F.; Bonelli, E.; Fasano, T.; Sverzellati, N.; Caruso, A.; et al. Inflammatory burden and persistent CT lung abnormalities in COVID-19 patients Scientific reports, 2022, 12(1), 4270. [CrossRef]

| TOTAL n=764 |

SURVIVORS n=534 |

ICU ADMISSION n=106 |

DECEASED n=124 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 74 (72-75) | 71 (69-73) | 71 (67-73) | 85 (84-86) | < 0.000001 (1-2, 3) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 412 (54.1) | 282 (68.2) | 69 (16.7) | 61 (14.8) | 0.019 (1,2,3) |

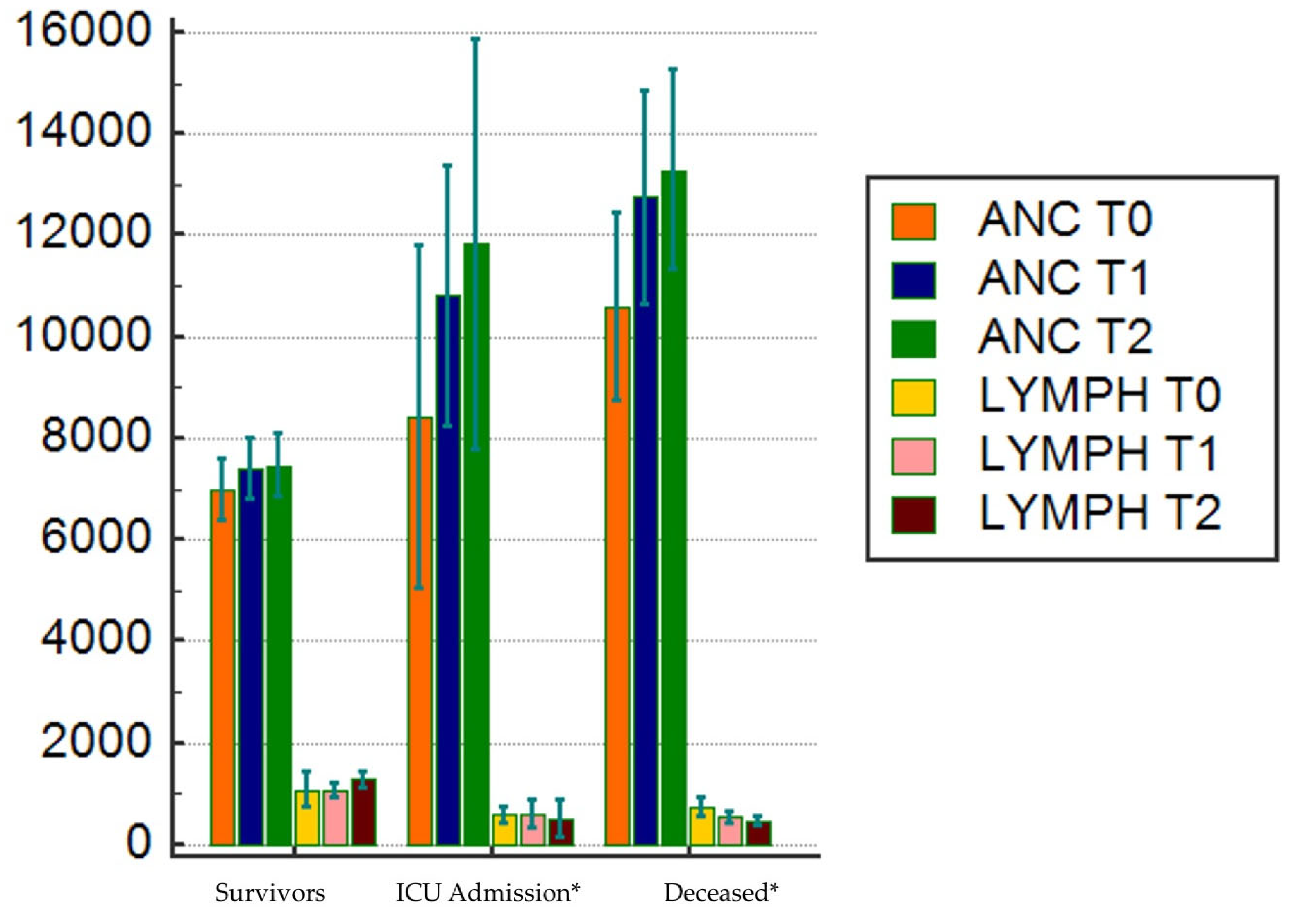

| Lymph, 109/L | 800 (718 – 800) | 900 (800-900) | 581 (506-820) | 600 (500-671) | < 0.000001 (1,2) |

| Anc, 109/L | 6500 (6200-6800) | 5900 (5600-6300) | 7500 (6760-8927) | 9000 (7500-9039) | < 0.000001 (1,2,3) |

| P/F Ratio | 206 (198 – 224) | 258 (241-272) | 171(121-133) | 128 (117-146) | < 0.000001 (1,2,3) |

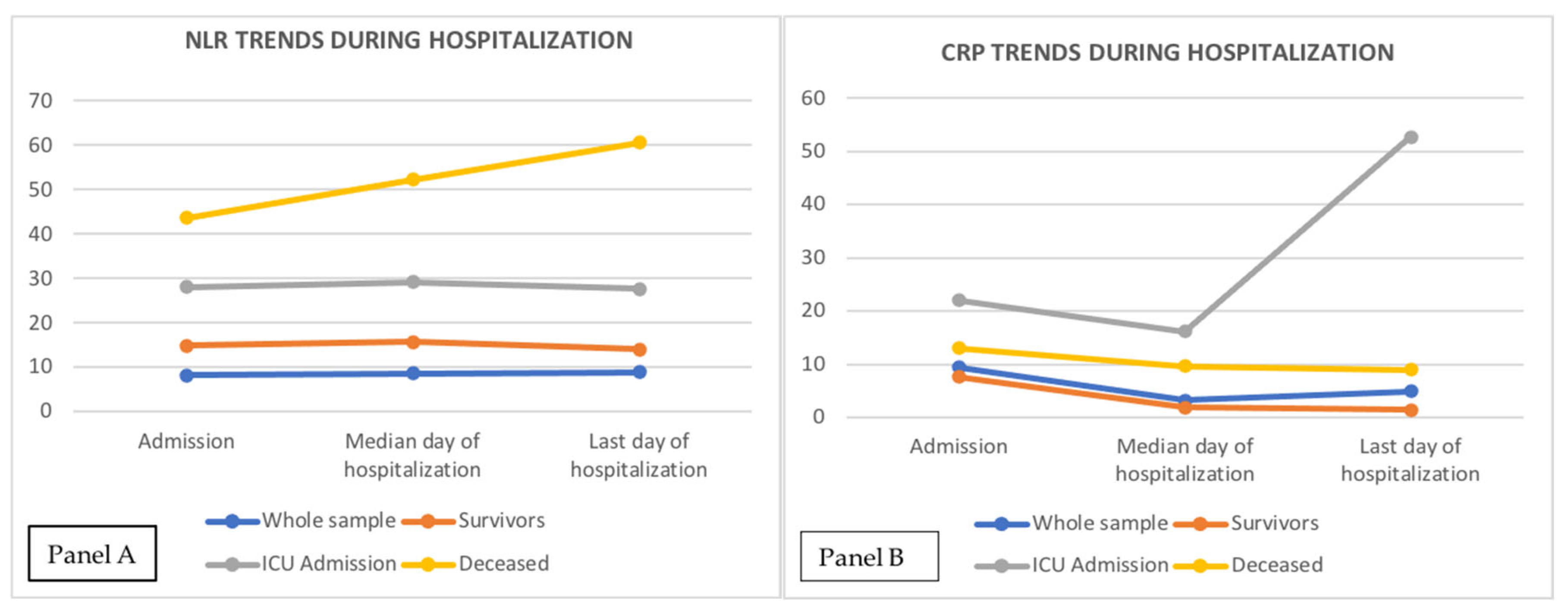

| NLR T0 | 8.18 (7.7 – 8.9) | 6.7 (6.2-7.3) | 13.2 (11.1-15.8) | 15.5 (13.6-18.6) | < 0.000001 (1,2) |

| NLR T1 | 8.7 (7.8 – 9.7) | 7 (6.1-7.8) | 13.5 (11-16) | 23 (17.8-31.3) | < 0.000001 (1,2,3) |

| NLR T2 | 8.9 (8.6-10.5) | 5.2 (4.5-5.3) | 13.5 (12.4-22.4) | 33 (22.6-41,7) | < 0.000001 (1,2,3) |

| CRP T0, mg/dL | 9.4 (8.4-10.6) | 7.7 (6.2-8.7) | 22 (12.8-73.8) | 13 (9.3-15.5) | < 0.000001 (1,2,3) |

| CRP T1, mg/dL | 3.3 (2.5-4.5) | 1.9 (1.4-2.4) | 16.2 (8.5-25) | 9.7 (6.9-11) | < 0.000001 (1,2,3) |

| CRP T2, mg/dL | 4.9 (3-6.6) | 1.5 (1.3-2.2) | 52.7 (22.4-101) | 10 (8.1-16.8) | < 0.000001 (1,2,3) |

| Length of stay, days | 9 (8-10) | 10 (10-11) | 4 (3-5) | 8 (7-9) | < 0.000001 (1,2,3) |

|

Comorbidities Hypertension n (%) Diabetes, n (%) CKD, n (%) COPD, n (%) CV disease, n (%) |

457 (62.5) 334 (43.9) 166 (21.7) 107 (13.8) 297 (25.7) |

306 (57) 221 (41) 105 (19) 82 (15) 198 (37) |

68 (64) 47 (44) 30 (28) 11 (10) 47 (44) |

83 (66) 66 (53) 31 (25) 14 (11) 52 (41) |

0.09 0.06 0.082 0.252 0.279 |

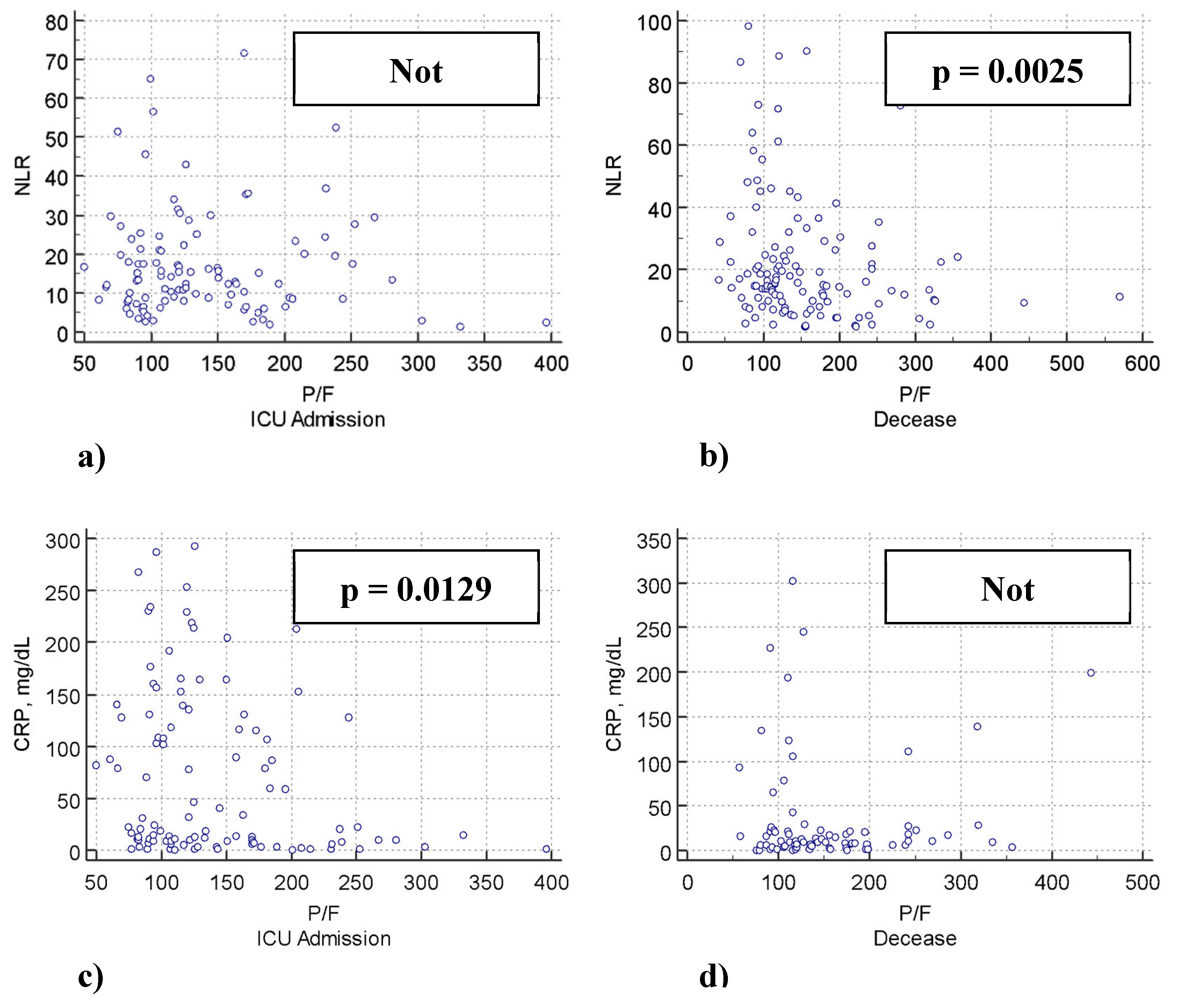

| Dependent Variable P/F ratio | WHOLE POPULATION | SURVIVORS | ICU ADMISSION | DECEASED | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | r | p | β | r | p | β | r | p | β | r | p | |

| NLR | -1.91 | - 0.22 | <0.0001 | -1.68 | -0.13 | 0.002 | -0.35 | -0.007 | 0.438 | -0.84 | -2.2 | 0.023 |

| CRP | -0.5 | -0.27 | <0.0001 | -0.65 | -0.24 | <0.0001 | -0.19 | -0.23 | 0.015 | -0.15 | -1.5 | 0.134 |

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE: DECEASE | ||||

| HR univariable | p | HR multivariable | p | |

| NLR | 1.05 (2.01*) [1.0406 – 1.0709] |

<0.0001 | 1.04 (1.77*) [1.0295 – 1.0618] |

<0.0001 |

| CRP | 1.002 [0.9996 – 1.0058] |

0.0879 | 1.002 (1.001*) [0.9994 – 1.0063] |

0.1081 |

| DEPENDENT VARIABLE: ICU ADMISSION | ||||

| HR univariable | p | HR multivariable | p | |

| NLR | 1.02 (1.4*) [1.0127 – 1.0390] |

0.0001 | 1.02 (1.39*) [1.0117 – 1.0419] |

0.002 |

| CRP | 2.66 [2.4315 – 3.1368] |

<0.0001 | 2.4 (1.7*) [1.922 – 2.615] |

<0.0001 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Z | p | % Mediation | ||||||||

| Indirect | -0.035 | 0.174 | -0.940 | -0.251 | -3.19 | 0.001 | 16.3 | ||||||||

| Direct | -2.849 | 0.640 | -4.153 | -1.583 | -4.45 | < 0.001 | 83.7 | ||||||||

| Total | -3.404 | 0.672 | -4.678 | -2.112 | -5.07 | < 0.001 | 100.0 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).