1. Introduction

Falls are a chronic condition [

1] that require long-term care and support services to fully meet the older populations’ needs[

2]. More than 37 million falls each year require medical attention, 684,000 people globally die from falls, and over 80% are from low-and middle-income countries (LMICs)[

3]. In addition, more than 1 billion older adults in LMICs do not have access to resources to help them stay healthy [

4,

5] thus, they are exposed to a high risk of falls and long-term adverse consequences. For example, Thailand will have one of the largest older populations (25%,~17 million in 2040) among LMICs in Asia. Thailand is facing an overburdened public healthcare system.[

6] One-third to half of Thai adults aged ≥ 60 years acknowledged having falls and/or fear of falling.[

7] Falls were also reported in 10.4-53.5% of older people living in the community in Asia.[

8]

A review of international fall prevention strategies indicated that no country has been able to eliminate falls in older adults.[

9] Several behavioral interventions developed in high-income countries effectively reduce falls, however, there are many barriers to incorporating these types of initiatives in LMICs. Large-scale implementation research in Thailand demonstrates the benefits of using trained community-health workers (CHWs) and care managers (CMs) to reduce behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia [

10]. We conducted a systematic review related to evidence-based fall interventions for older adults and selected the US CDC’s STEADI based on several considerations including (a) effectiveness based on published evidence in improving fall risk screening, reducing fall-related hospitalizations and medical costs in the US;[

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] (b) the intervention fits the needs of Thai older adults; and (c) three components of STEADI would be implemented in the long-term care system using existing resources in primary care settings.

Implementation programs, such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’ s Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) program, illuminate vital elements of coordinated care and fall prevention for healthcare providers. STEADI also provides strategies to help older adults acknowledge their fall risk and fear of falling and stay independent [

16]. STEADI was developed in 2013[

1] based on three conceptual models including the Chronic Disease Care Model,[

17] health communication,[

1] and Transtheoretical Stages of Change Model [

18]. STEADI effectively improves fall-risk screening and reduces fall-related hospitalizations and medical costs in the U.S.[

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] STEADI implementation in primary care settings suggests that fall-risk screening, assessments, and individualized care plans (e.g., exercise) are effective at reducing falls and preventing chronic conditions[

11,

13,

19,

20]. STEADI Algorithm of screening, assessment, and intervention has the potential to be implemented in LMICs, but has yet to be adapted and systematically implemented in any LMICs.

Cultural adaptation is an essential action and natural step in the implementation process to improve the adoption of evidence-based interventions in LMICs. Culturally adapted STEADI for LMICs is needed and has the potential to benefit a large population. Adaptation of evidence-based interventions is needed when patients’ engagement in service falls below what is expected, culturally specific risks/protective factors need to be incorporated into the intervention, and patient outcomes are not achieved.[

21] Large-scale implementation research in Thailand demonstrates the benefits of a cultural adaptation of evidence-based intervention [

22]. Thus, proper adaptations of STEADI to the Thai context are necessary for creating a sustainable and effective implementation program in Thailand. We aimed to culturally adapt the CDC’s Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) for Thai older adults and assess the acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of the Thai-STEADI in primary care delivered by trained community health workers (CHWs) and care managers (CMs).

2. Materials and Methods

Design This study consists of two phases, including cultural adaptation of the CDC’s Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) for Thai older adults and assess the acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of the Thai-STEADI in primary care delivered by trained community health workers (CHWs) and care managers (CMs).

Phase I: Cultural adaptation of STEADI

STEADI’s tools for screening (Step a) and assessment (Step b) were culturally adapted into the Thai context[

23,

24] and a 1-year prospective study (N=480) showed that these tools have high sensitivity (93.9%, 95% CI 88.8, 92.7) and specificity (75%, 95% CI 70, 79.6) to predict falls.[

24] We culturally adapted STEADI Step c: intervene using the following steps: 1) assess the community; 2) understand/select the intervention; 3) consult with experts/stakeholders and decide what needs to be adapted and adapt the original program; and 4) train staff and pilot test the adapted materials.[

25,

26]

First, Assessed the current care delivery system and resources in the community. We met with the representatives from the Thai Ministry of Public Health, National Health Security Office, and local public health to assess their need and receive support to launch the study when funded. All parties agreed to select the city of Mahasarakham as the study site.

Second, Selected EBI that matches the population and context. We conducted a systematic review related to evidence-based fall interventions for older adults and selected the US CDC’s STEADI based on several considerations including (a) effectiveness based on published evidence in improving fall risk screening, reducing fall-related hospitalizations and medical costs in the US;[

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] (b) the intervention fits the needs of TOA; and (c) three components of the STEADI would be implemented using existing delivery resources in primary care.

Third, Seven researchers and clinicians in the US and Thailand met via zoom meetings and in-persons in Thailand to decide what needs to be adapted.

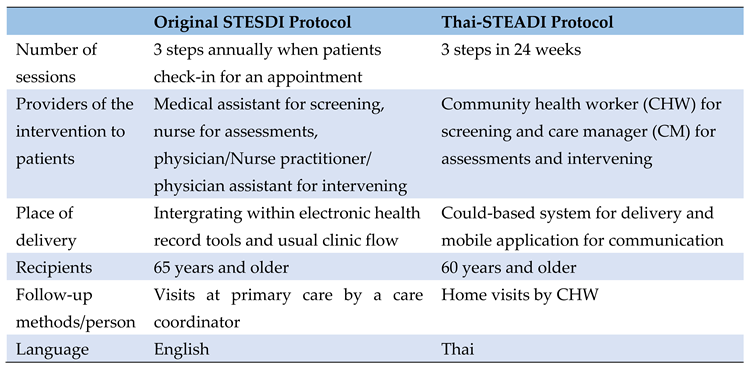

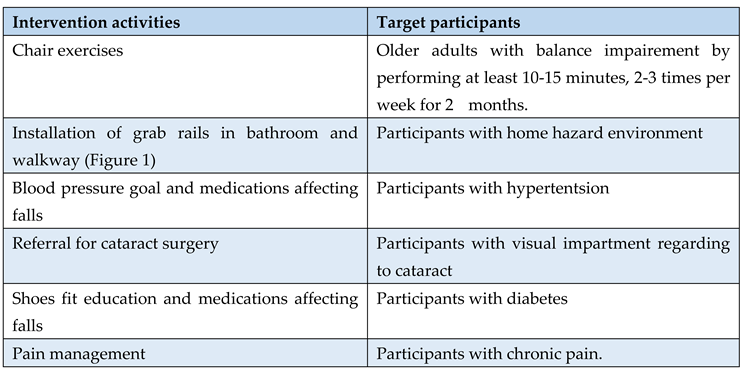

Table 1 compares the original STEADI with the adapted STEADI in Thai context.

Table 1 shows a comparison of the original STEADI with the adapted STEADI in Thai context.

Finally, we trained 5 CHWs and 2 CMs, aged 57.2±.3.3 (aged range 53-62), all female and 60% have 10+ years of experience in their roles to conduct the pilot study in phase II.

Table 1.

Comparison of the original STEADI with the adapted STEADI in Thai context.

Table 1.

Comparison of the original STEADI with the adapted STEADI in Thai context.

Phase II: Acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of the Thai-STEADI.

Setting and sample. Participants were recruited from low-income communities in Mahasarakham Province, Thailand. The screening, assessment and fall intervention procedures were carried out at older participants’ homes, a community center, and a primary care unit. Twenty participants who met the following inclusion criteria were enrolled: 1) ≥60 years old of age and 2) live in their own homes. Exclusion criteria were: 1) a medical condition precluding fall risk assessments using a timed up-and-go test (e.g., on a wheelchair or bedridden), and 2) currently receiving a treatment program from a rehabilitation facility.

Measures

Fall risk

Fall risk was assessed by the CDC’s Stay Independent fall risk checklist. It consists of 12 statements related to physical and psychological fall risk factors with yes or no answers. A score of 4 points or higher indicates a risk of falling.[

16] The sensitivity of this checklist with discriminating fallers and predicting future fallers for community-dwelling older adults is 73-80%.[

27]

Time-up and go test

Timed Up and Go (TUG) test has been widely used to assess functional mobility and predict fall risk.[

28,

29] It provides reliable data and is validated among community-dwelling older adults.[

30] The TUG has an acceptable sensitivity (87%) and specificity (87%) for assessing older adults who are prone to falls.[

31]. For the TUG test, participants stand up from a standard armchair, walk at a normal pace for 3 meters, return, and sit down again.[

32] Participants who complete the TUG test in less than 12 seconds will be classified as having low fall risk.[

33]

Acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility

We assess the acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of Thai-STEADI using the three newly developed implementation outcome measures.[

34] Time to complete is less than 5 minutes per measure. Scales values range from 1 to 5 (1=completely disagree and 5= completely agree). Scales can be created for each measure by averaging responses. No items need to be reverse coded.[

34] Higher scores indicate greater acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of the Thai-STEADI.

Data collection and pilot testing of Thai- STEADI

Thai-STEADI consists of three steps including screening, assessing, and intervening.[

35]

Step 1 Screening fall risk: Community Health Worker (CHW) provided older adults a Stay Independent self-assessment checklist or perform a quick screening to identify persons at high risk for falls and further assess multiple fall risk factors such as fear of falling, which could detect care needs early and thereby prevent the future need for more intensive long-term care. CHW documented the risk in the STEADI flowsheet and sent it to the Care Manager (CM).

Step 2 Assessing fall risk: Care Manager (CM) conducted fall risk assessments to determine specific fall risk factors including balance tests, vision test, medications review, comorbidities, and home hazards. CM documented the assessments in the STEADI flowsheet and shared it to CHWs.

Step 3 Intervening: After identifying the risk factors, the CM developed a plan based on the modifiable risk factors including a strength and balance program, medication management, corrective eyewear, cataract surgery, orthotics and exercise, vitamin D supplementation, and home modification.[

35] The CM intervened via several techniques such as assisting older adults in understanding their fall risk and successfully making behavior changes based on the Stages of Change model.[

18] If an older adult need assistive devices (e.g., walking sticks) and home modification, the Universal Coverage (UC) scheme supported by national taxation (National Health Securtiy Office) and district and local municipal funds usually support these needs, respectively. In addition, our program integrates with a long-term care system that can refer individuals who need specialists to the community hospital where Thai citizens can access medical care as part of three schemes including Social Health Insurance, Civil Servant Medical Benefit and UC under the national health insurance program. Besides the three steps, older adults receive the STEADI's information pamphlet (Thai language) related to fall risk, how to prevent falls, check for safety, postural hypotension, and chair rise exercise.[

16]

Data analysis

Data was analysed using descriptive statistics such as pecentage, mean and standard deviation using SPSS program (IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0).

3. Results

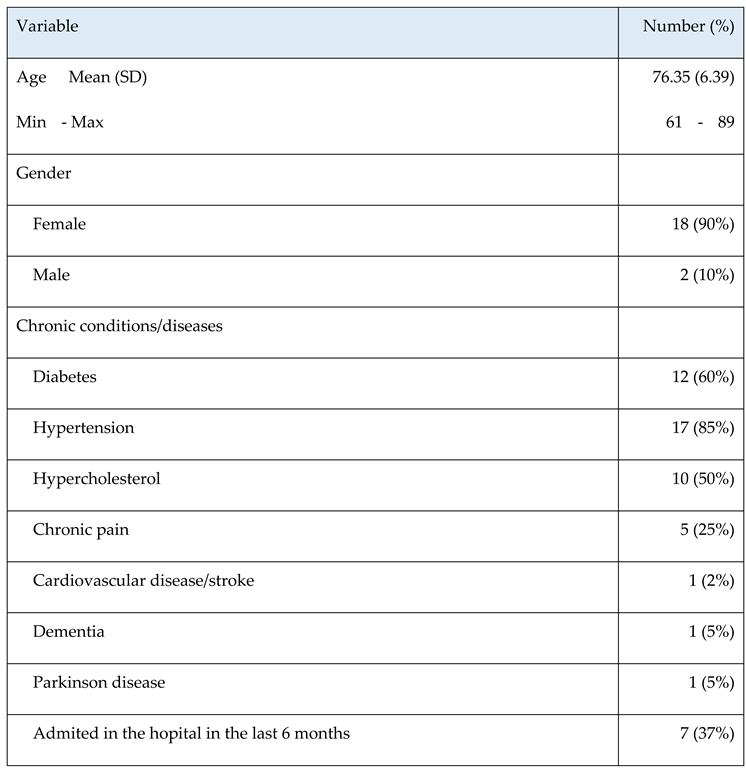

The majority of participants (90%) were women, mean age was 76.4 (SD=5.4, range 61 to 89) years, 85% have hypertension and 60% have diabetes.

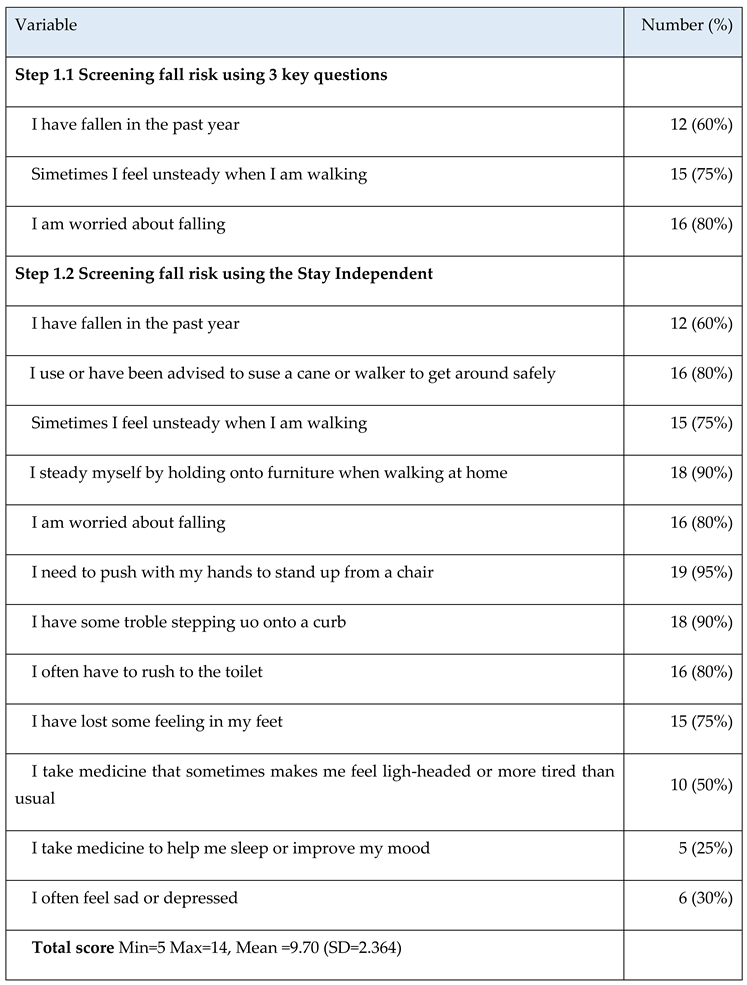

Table 2 presents the descriptive characteristics of 20 older participants.

Step a: Screening at home or in community.

Community health workers screened for fall risk in 20 older adults using 3 key quick questions. If older partcipants have at least one issue from the three, they are high risk to fall. In the quick screening, CHWs found that 100% of older partcipants have high risk to fall. Next, CHWs used the CDC’s Stay Independent fall risk checklist (range 0-14) and found that 100% of older partcipants have the total score at least 4 which indicated that all of them have high risk to fall (total scores mean 9.7 and SD= 2.4). In addition, the majority (80%) reported that they are worried about falling, 95% reported that they need to push with their hands to stand up from a chair and 90% have some troble stepping uo onto a curb.

Table 3.

Screening fall risk from older participants by communty health workers.

Table 3.

Screening fall risk from older participants by communty health workers.

Step b: Assessing.

Care managers assessed balance, vision, feet, footwear, number of medications and CHWs assessed home hazards. They found that 50% have poor balance (Timed Up and Go score 27.3± 18.2 seconds), 70% take at least 4 types of medications, 50% have vision impairment, 80% lost some feeling in their feet, 75% fell at the walkway and 70% have problems with toilet (e.g., no bar rail).

Step c: Intervening. For this pilot testing, CMs selected 5 older participants who had the highest fall risk scores and provided the interventions that tailored to their risk factors as presented in

Table 4.

Figure 1.

Installation of grab rails in bathroom (Before and after).

Figure 1.

Installation of grab rails in bathroom (Before and after).

Five participants’ attendance all sessions. Examples feedback from participants included:

“Being more aware of my fall risk and trying to exercise more” (Male #3).

“I like my community health worker and care manager; they are friendly and care about my health and safety” (Female #5).

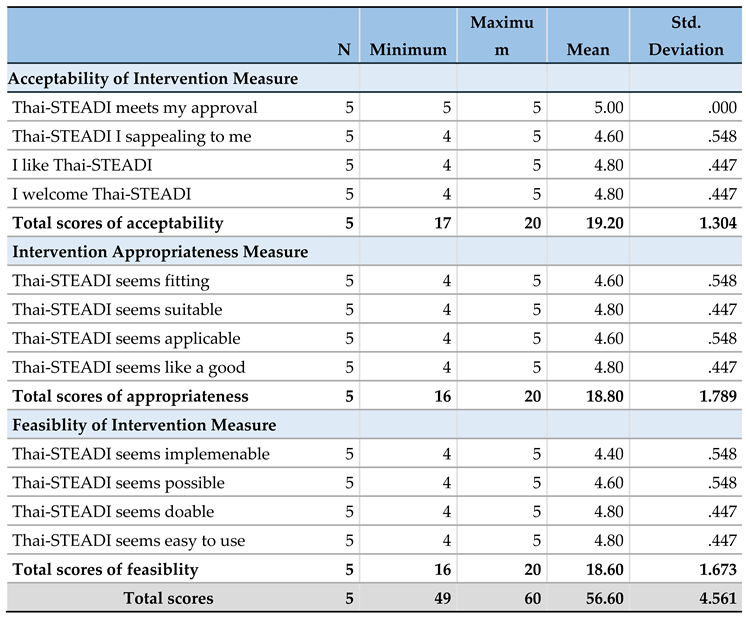

Acceptability, Appropriateness and Feasibility of the Thai-STEADI.

Table 5 shows the mean and total scores of acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility from CHWs and CMs’ perspectives.

Acceptability: 80% of CHWs and CMs completely agreed that STEADI meets their approval, appealing to them, they like and welcome it.

Appropriateness: 60-80% of CHWs and CMs completely agreed that STEADI seems fitting, suitable, applicable and like a good match. Feasibility: 80% of CHWs and CMs completely agreed that STEADI seems implementable, possible, doable, and easy to use. Overal, CHWs & CMs indicated high acceptability (19.20±1.31 of 20 total), appropriateness (18.80±1.79 of 20 total) and feasibility (18.60±1.67 of 20 total) of the STEADI program.

Table 5.

Acceptability, Appropriateness and Feasibility of the Thai-STEADI.

Table 5.

Acceptability, Appropriateness and Feasibility of the Thai-STEADI.

Discussion

We aimed to culturally adapt the CDC’s STEADI for Thai older adults and assess the acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of the Thai-STEADI in primary care delivered by trained CHWs and CMs. To our knowledge , this study presents the first cultural adaptation of the CDC’s STEADI for older adults in LMICs which delivered by CHWs and CMs. This study introduces an international fall collaborative and prevention for older people in LMICs. This study also incorporates researchers and clinicians in the US and Thailand.

A recent systematic review of strategies to implement multifactorial fall prevention indicated that the most used implementation strategies at the individual level were tailoring, active learning, personalizing risk, consciousness-raising and participation.[

36] Most strategies at the environmental level were technical assistance, use of lay health workers, peer education, increasing stakeholder influence and forming coalitions.[

36] Also, the differences between countries (e.g., culture, environment, exercise preference, sunlight exposure, healthcare and social welfare) may influence the success of implementing falls prevention.[

37] A culturally adapted program and systematically implementation have the potential to create a sustainable intervention and improve older adults’ engagement in the program and outcomes. Most falls in Thai older adults occur at home the same as other studies[

38] and are caused by several modifiable risk factors such as balance impairment, fear of falling and hypertension.[

39]

Our study showed that the community-based multifactorial Thai-STEADI delivered by CHWs and CMs is feasible and acceptable to prevent falls in older adults with limited access to health care. A recent scoping review indicated knowledge and awareness of risk, the influence of peers, and general uptake and trust in health services were barriers to implementation in LMICs. [

40] In collaboration with CHWs, a CM (nurse) provided a 3-month simple home-based balance training program and found the intervention group (n=52) improved the timed up and go test, functional reach test and FOF after 3, 6, 9 and 12 months compared with the control group (n=52).[

41] In addition

, after home modifications, previous study found that participants (n=43) improved their mobility and walking distance. [

42] Moreover, all participants’ quality of life increased by 0.203 from 0.346 at baseline to 0.549 after the modifications.[

43] Previous study in Thailand indicated that home modification in low-resourced settings are technically and financially feasible and can lead to improving physical function and quality of life.[

43] Large-scale implementation research in Thailand demonstrates the benefits of using trained community-health workers and care managers to reduce behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia [

10]. Incorporating peer support into the healthcare system may reduce the burden on the healthcare system [

44]. Also, peers and community partners may influence the general uptake of and trust in health services, even in rural environments where accessibility may be difficult.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the pilot study with small sample sizes and a cross-sectional design limited the ability to drawn the effects of Thai-STEADI and establishment of causal relations. Second, social desirability may lead older participants to under or over-reporting their fall risk. Finally, the selection of participants was not random.

Conclusions

Primary care systems and community partners can be leveraged to stop falls and enhance older adults' well-being in LMICs. Community-health workers and care managers are leaders in their communities, at the forefront of primary prevention, and play an essential role in reducing the burden on the healthcare system. The STEADI of screening, assessment, and intervention for primary care providers could be used in LMICs or low-income settings with limited resources. A culturally adapted program and systematically implementation have the potential to create a sustainable intervention and improve older adults’ engagement in the program and outcomes. This project incorporates researchers and clinicians in the US and Thailand, builds on successful projects that use community health workers, students, and care managers to assess, educate and facilitate change, and has the potential to reduce fall rates and concern for falling in Thailand, with implications for other LMICs.

Author Contributions

LT: ST, JS, RX, BPN, JHP, WL and EK contributed to the study, conceptualization, design, and data analysis. LT wrote the original draft, and ST, JS, RX, BPN, JHP, WL and EK contributed to substantial revision of the original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is received financial support from the University of Central Florida Foundation. Drs. Thiamwong, Xie and Park have received funding from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) (R03AG06799) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) (R01MD018025) of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Central Florida Institutional Review Board (STUDY00004288).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stevens JA, Phelan EA. Development of STEADI: a fall prevention resource for health care providers. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(5):706-14.

- Abdi S, Spann A, Borilovic J, de Witte L, Hawley M. Understanding the care and support needs of older people: a scoping review and categorisation using the WHO international classification of functioning, disability and health framework (ICF). BMC Geriatrics. 2019;19(1):195. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Preventing and controlling noncommunicable diseases: WHO; 2022 [Available from: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/activities/preventing-and-controlling-noncommunicable-diseases.

- The World Bank. Poverty [Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview.

- Thiamwong L. Future Nursing Research of Older Adults: Preserving Independence and Reducing Health Disparities. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research. 2022;26(1):1-6.

- WorldBank. Thailand Economic Monitor - June 2016: Aging Society and Economy 2016 [cited 2022 April 29]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/thailand/publication/thailand-economic-monitor-june-2016-aging-society-and-economy.

- Thiamwong L, Ng BP, Kwan RYC, Suwanno J. Maladaptive Fall Risk Appraisal and Falling in Community-Dwelling Adults Aged 60 and Older: Implications for Screening. Clinical Gerontologist. 2021:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Romli MH, Tan MP, Mackenzie L, Lovarini M, Suttanon P, Clemson L. Falls amongst older people in Southeast Asia: a scoping review. Public health. 2017;145:96-112. [CrossRef]

- Allen C, Wallace SC. Around the World in 16 Ways: Searching Internationally for Fall Prevention Strategies. Patient Safety. 2020;2(3):24-9. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Levkoff S, Chuengsatiansup K, Sihapark S, Hinton L, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Implementation Science in Thailand: Design and Methods of a Geriatric Mental Health Cluster-Randomized Trial. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC). 2022;73(1):83-91. [CrossRef]

- Stevens JA, Lee R. The Potential to Reduce Falls and Avert Costs by Clinically Managing Fall Risk. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(3):290-7.

- Lohman MC, Crow RS, DiMilia PR, Nicklett EJ, Bruce ML, Batsis JA. Operationalisation and validation of the Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) fall risk algorithm in a nationally representative sample. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2017;71(12):1191-7. [CrossRef]

- Casey CM, Parker EM, Winkler G, Liu X, Lambert GH, Eckstrom E. Lessons Learned From Implementing CDC’s STEADI Falls Prevention Algorithm in Primary Care. The Gerontologist. 2016;57(4):787-96. [CrossRef]

- White ND. Mitigating Medication-Related Fall Risk Through Pharmacist–Prescriber Collaboration. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2021;15(6):602-4. [CrossRef]

- Blalock SJ, Ferreri SP, Renfro CP, Robinson JM, Farley JF, Ray N, et al. Impact of STEADI-Rx: A Community Pharmacy-Based Fall Prevention Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1778-86. [CrossRef]

- CDC. STEDI-Older Adult Fall Prevention 2017 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/.

- Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective clinical practice : ECP. 1998;1(1):2-4.

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American journal of health promotion : AJHP. 1997;12(1):38-48.

- Eckstrom E, Parker EM, Lambert GH, Winkler G, Dowler D, Casey CM. Implementing STEADI in Academic Primary Care to Address Older Adult Fall Risk. Innovation in Aging. 2017;1(2):igx028-igx. [CrossRef]

- Phelan EA, Aerts S, Dowler D, Eckstrom E, Casey CM. Adoption of Evidence-Based Fall Prevention Practices in Primary Care for Older Adults with a History of Falls. Front Public Health. 2016;4:190.

- Marsiglia FF, Booth JM. Cultural Adaptation of Interventions in Real Practice Settings. Research on social work practice. 2015;25(4):423-32. [CrossRef]

- Tongsiri S, Levkoff S, Gallagher-Thompson D, Teri L, Hinton L, Wisetpholchai B, et al. Cultural Adaptation of the Reducing Disability in Alzheimer's Disease (RDAD) Protocol for an Intervention to Reduce Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Thailand. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2022.

- Loonlawong S, Limroongreungrat W, Jiamjarasrangsi W. The Stay Independent Brochure as a Screening Evaluation for Fall Risk in an Elderly Thai Population. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:2155-62. [CrossRef]

- Loonlawong S, Limroongreungrat W, Rattananupong T, Kittipimpanon K, Saisanan Na Ayudhaya W, Jiamjarasrangsi W. Predictive validity of the Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries (STEADI) program fall risk screening algorithms among community-dwelling Thai elderly. BMC Medicine. 2022;20(1):78. [CrossRef]

- Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Udelson H, Böing EA, Wood R, Fernandez ME, et al. A scoping study of frameworks for adapting public health evidence-based interventions. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Haardoerfer R, Boing E, Udelson H, Wood R, et al. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implementation Science. 2018;13(1):125. [CrossRef]

- Nithman RW, Vincenzo JL. How steady is the STEADI? Inferential analysis of the CDC fall risk toolkit. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;83:185-94. [CrossRef]

- Ory MG, Smith ML, Jiang L, Lee R, Chen S, Wilson AD, et al. Fall prevention in community settings: results from implementing stepping on in three States. Frontiers In Public Health. 2015;2:232-. [CrossRef]

- Shumway-Cook A, Silver IF, LeMier M, York S, Cummings P, Koepsell TD. Effectiveness of a community-based multifactorial intervention on falls and fall risk factors in community-living older adults: a randomized, controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A. 2007(12):1420. [CrossRef]

- Bohannon RW. Reference values for the timed up and go test: a descriptive meta-analysis. Journal Of Geriatric Physical Therapy (2001). 2006;29(2):64-8.

- Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Physical Therapy. 2000;80(9):896-903. [CrossRef]

- Podsiadlo D, Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. Timed Up & Go. The Timed Up & Go: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. 1991;39(2):142-8. [CrossRef]

- Bischoff HA, Stahelin HB, Monsch AU, Iversen MD, Weyh A, Von Dechend M, et al. Identifying a cut-off point for normal mobility: a comparison of the timed 'up and go' test in community-dwelling and institutionalised elderly women. Age and Ageing. 2003(3):315. [CrossRef]

- Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Clary AS, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science. 2017;12(1):108. [CrossRef]

- Eckstrom E PE SI, Lee R. Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI):Coordinated Care Plan to Prevent Older Adult Falls2021.

- Vandervelde S, Vlaeyen E, de Casterlé BD, Flamaing J, Valy S, Meurrens J, et al. Strategies to implement multifactorial falls prevention interventions in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. Implementation Science. 2023;18(1):4. [CrossRef]

- Hill KD, Suttanon P, Lin S-I, Tsang WWN, Ashari A, Hamid TAA, et al. What works in falls prevention in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatrics. 2018;18(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Ding Z, Qiu L, Li A. Falls and risk factors of falls for urban and rural community-dwelling older adults in China. BMC Geriatrics. 2019;19(1):379. [CrossRef]

- Dai W, Tham Y-C, Chee M-L, Tan NYQ, Wong K-H, Majithia S, et al. Falls and Recurrent Falls among Adults in A Multi-ethnic Asian Population: The Singapore Epidemiology of Eye Diseases Study. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):7575. [CrossRef]

- Martin K, Wenlock R, Roper T, Butler C, Vera JH. Facilitators and barriers to point-of-care testing for sexually transmitted infections in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):561. [CrossRef]

- Thiamwong L, Suwanno J. Effects of Simple Balance Training on Balance Performance and Fear of Falling in Rural Older Adults. International Journal of Gerontology, Vol 8, Iss 3, Pp 143-146 (2014). 2014(3):143. [CrossRef]

- Tongsiri SaH, K. The Application of ICF-based Functioning Data on Home Environment Adaptation for Persons with Disabilities. Disability, CBR & Inclusive Development. 2013;24(2):40-53.

- Tongsiri S, Ploylearmsang C, Hawsutisima K, Riewpaiboon W, Tangcharoensathien V. Modifying homes for persons with physical disabilities in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(2):140-5. [CrossRef]

- Shalaby RAH, Agyapong VIO. Peer Support in Mental Health: Literature Review. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(6):e15572. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).