1. Introduction

The concept of cultural distance is well anchored in the International Business (IB) literature, and has evolved through several and different periods, showing how much this construct has influenced research in this field. However, its effects on international entry mode, performance, and even FDI distribution still raises great questions. There is an ever-growing concern regarding a possible mismatch between the theoretical arguments, methodological procedures and empirical results found in distance related studies (Dow, 2017; Verbeke et al. 2017). In fact, Shenkar et al. (2020) show that studies have been trying to rescue the distance metaphor by providing remedies to deal with several of its shortcomings. Therefore, in order to advance the knowledge of distance, our attention should be steered towards identifying the conditions that explain the different outcomes described in the literature. In this article, we aim to contribute to this debate, and examine more specifically the relationships between cultural distance (CD) and formal institutional distance (FID), and how their interaction affects the performance of foreign multinational subsidiaries.

When it comes to the implications of CD, the majority of studies emphasize its negative effects (Beugelsdijk et al. 2018). However, there is a growing number of studies pointing to the asymmetric implications of CD. Depending on the direction, the effects of CD can be positive or negative (Correa da Cunha et al. 2022; Magnani et al., 2018; Selmer et al., 2007). The directionality of formal institutional distance (FID) has been extensively supported by theoretical arguments and empirical evidence showing that the quality of formal institutions in the host country reduces transaction costs and impacts financial performance positively (Correa da Cunha et al. 2022b; Klasing, 2013; Maseland, 2013; Zaheer et al. 2012, Hernández and Nieto, 2015).

When considering how formal and informal institutions interact, North (1990, p. 47) posits that formal institutions can be “enacted to modify, revise, or replace informal constraints”. In fact, studies have shown that when operating in host countries with institutional voids, the effects of CD on the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms tend to increase (Correa da Cunha et al. 2022a). In this study we argue that the greater the FID between the home and the host country the more difficult it becomes to adapt to the formal norms and regulations in the host country environment. This causes foreign subsidiary firms to rely more on their ability to cope with the cultural differences. Thus, the higher the FID the more significant the effects of CD on the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms.

We test our assumptions using data from the Orbis database and a sample that includes over 1450 foreign subsidiaries with approximately 1200 from developed countries and 250 from emerging markets operating in the 10 largest economies in Latin America over a period of 3 years ranging from 2013 to 2015. Latin America provides a relevant context for this study due to “societal, cultural, and economic characteristics that make the region an ideal ‘natural laboratory’ to build and test management theories” (Aguinis et al., 2020, p. 615). Furthermore, the diversity in our data which includes 168 pairs of different home and host countries provides the means to discuss the effects of distances (Franke and Richey, 2010) and make comparisons regarding the implications of distances for the financial performance of foreign subsidiaries from developed countries and from emerging markets.

Our findings contribute to the debate on how formal and informal institutional distances interact and impact the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms by showing that the asymmetric effects of CD tend to increase only when FID is towards less developed host countries. These results indicate that when the foreign host country environment provides less support from formal institutions compared with the home country, foreign subsidiaries are likely to rely on their ability to cope with the less formal and less strict nature of cultural differences (i.e. Cultural Distance). In that sense, by considering the direction of FID, our findings reveal that the higher the FID towards less developed host countries, the more significant the effects of CD on the financial performance.

This paper is organized into five major sections. Following the introduction, section 2 presents the theoretical background and hypotheses to be tested. The third section focusses on our research method and approach to model estimation. Results are presented in the fourth section, while in the fifth and final section we conclude by highlighting our main contributions, limitations and opportunities for future research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Behavioral factors affecting the internationalization of firms were first introduced by Uppsala scholars. Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) and Johanson and Vahlne (1977) introduced the concept of “psychic distance” (Beckerman, 1956) to represent the sum of factors preventing the flow of information between the multinational firm and the foreign market. According to the Uppsala model, the internationalization of firms is affected by several factors including differences in language, culture, political systems, level of education and economic development (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977).

Distance can be defined as the physical separation between two points which implies a positive value. Although the meaning is straightforward, recent studies show that the “knowledge of distance, in terms of conceptual specification and consequences for IB practice, is incomplete and sometimes ambiguous” (Verbeke et al., 2017, p. 1). Others have gone further by recommending that when it comes to distance, despite the huge popularity of the topic in the IB literature, results from empirical studies indicate that we may be at the wrong track (Shenkar, 2012a; Zaheer et al., 2012).

In order to address these critiques, it is important to review how the notion of distance evolved in the IB literature. Initially, scholars introduced the broad concept of psychic distance to represent the sum of factors preventing the flow of information between the multinational firm and the foreign market (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977; Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975). Being too broad and, therefore, difficult to operationalize, the contributions of Hofstede (1980) and Kogut and Singh (1988) offered a more practical alternative for computing the differences between countries by adopting the CD construct. However, CD is a much narrower perspective that focuses on the “extent to which the shared norms [ideas, beliefs] and values in one country differ from those in another” (Drogendijk and Slangen, 2006, p. 362). As the arguments in the majority of CD studies derive from the transaction cost theory, which attributes a liability character to distances (Zaheer, 1995), there is a tendency towards emphasizing its negative effects (Stahl and Tung, 2015; Beugelsdijk et al., 2018).

Although CD became extremely popular in the IB research agenda, Shenkar (2001) criticized several of its underlying assumptions and indicated that institutional distance (Kostova, 1996) could be a viable alternative to deal with some of these issues. Early studies adopting the institutional distance construct argued that the greater the institutional distance between home and host countries, the more difficult it will be for a parent firm to transfer organizational practices to a foreign subsidiary and operate in a profitable manner (Kostova, 1999; Kostova and Zaheer, 1999). However, it is important to note that institutions are ‘regulative, normative, and cognitive structures that provide stability and meaning to social behavior’ (Scott, 1995, p. 33).

While formal institutions relate to the regulatory pillar, informal ones refer to the normative and cognitive structures of a society (Peng et al., 2009). Thus, culture can be seen as a substratum of institutional arrangements, which means that culture is part of the informal institutions in the environment that underpin formal institutions (Peng et al., 2009). In that sense, formal rules are created by the polity, whereas informal norms are part of the heritage that we call culture (North, 1990, p. 37).

By considering the interdependence among the different levels of formality within the institutional framework, we argue that when focusing on a single perspective in isolation (e.g. CD and FID) studies provide an incomplete (and impaired) assessment of the differences between two countries. In that sense, rather than rejecting the distance metaphor, we build on the contributions of several important previous studies and follow the recommendation by Shenkar et al. (2020, p. 9) which indicates that in order to advance the knowledge of distance, “focus should now turn towards specifics, that is, the conditions under which the impact will be positive or negative, the mechanisms involved, and the process through which the benefits and drawbacks are activated”. We contribute to this debate by focusing on how FID moderates the asymmetric effects of the dimensions of CD on the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms.

2.1. The Asymmetric Effects of Cultural Distance

Since its introduction, distance has been used to explain the additional challenges and the resulting costs associated with conducting business in a distant foreign country (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977; Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975). Thus, distance can be perceived as a liability (Zaheer, 1995) which creates friction (Shenkar, Luo & Yeheskel, 2008; Shenkar, 2012b) as it increases transaction costs and affects the financial performance of foreign companies in a negative way.

More recently however, while the vast majority of CD studies still focus on the negative effects of CD (Beugelsdijk et al. 2018), there is a growing number of studies pointing to the asymmetric implications of CD by considering not only the magnitude (size) but also the direction of CD (Correa da Cunha et al. 2022; Magnani et al., 2018; Selmer et al., 2007). Additionally, it is important to consider that the different dimension of national culture can affect performance in specific and distinct ways. In fact, studies have shown that some dimensions of national culture might be more important and have a greater impact while other dimensions might have little or no impact at all (Maseland et al., 2018; Hofstede, 1989; Tallman and Shenkar, 1994).

In this study, we follow this approach and adopt the directional CD measure developed by Correa da Cunha et al. (2022) which accounts for the size and direction of the distance towards host countries in each (opposite) pole of the cultural dimensions` scales. Therefore, we consider that the direction of the specific dimensions of CD are likely to affect the financial performance of foreign subsidiaries in specific and distinct ways. In order to test these assumptions, we present the following hypothesis:

H1. The effects of CD on the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms are specific to each dimension of national culture and asymmetric depending on the direction towards host countries in each pole of the cultural dimension` scale.

2.2. FID Moderating the Relationship between CD and PERFORMANCE

In addition to investigating the effects of CD, we address the moderating effects of formal institutional distance (FID) on the relationship between CD and the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms. FID represents the degree of dissimilarity in terms of regulatory aspects of the institutional environments in the two countries (Kostova, 1999; Kostova and Zaheer, 1999).

Institutions are “the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction. In consequence they structure incentives in human exchange, whether political, social, or economic.” (North,1990, p. 3). Institutions are strong “if they support the voluntary exchange underpinning an effective market mechanism” and weak “if they fail to ensure effective markets or even undermine markets” (Meyer et al., 2009, p. 63). Studies have shown that the formal institutions, are among the several factors that impact the internationalization of emerging market firms (Correa da Cunha et al. 2022c).

The directionality of FID is well established in IB research (Hernández and Nieto, 2015; Konara and Shirodkar, 2018). Studies have shown that developed country firms are at an advantage when FID is towards more developed host countries, while emerging market firms know how to deal with institutional voids when operating in less developed host countries (Correa da Cunha, 2019; Correa da Cunha et al. 2022b; Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2011).

By focusing on the institutional framework (North, 1990; Scot, 1995), we analyze the interplay of cultural and formal institutional distances. Institutions can be defined as ‘regulative, normative, and cognitive structures that provide stability and meaning to social behavior’ (Scott, 1995, p. 33). While formal institutions relate to the regulatory pillar, informal ones refer to the normative and cognitive structures of a society (Peng et al., 2009). In that sense, formal rules are created by the polity, whereas informal norms are part of the heritage that we call culture (North, 1990, p. 37).

According to North (1990), formal and informal institutions can interact in a complementary or suppressive manner. Institutional complementarity refers to a condition in which “the presence (or efficiency) of one [institution] increases the returns from (or efficiency of) the other” (Hall and Soskice, 2001, p. 17). Alternatively, the suppressive relationship refers to a condition in which the formal rules may be “enacted to modify, revise, or replace informal constraints” (North, 1990, p. 47). In the same way, Pejovich (1999, p. 170) provides an “interaction thesis” that proposes the following outcomes: “1) Formal institutions suppress, but fail to change informal institutions; 2) Formal rules directly conflict with informal rules; 3) Formal rules are either ignored or rendered neutral; and 4) Formal and informal rules cooperate - as in cases where the state institutionalizes informal rules that had evolved spontaneously.”

According to Pejovich (1999, p. 171), “when formal rules conflict with the prevailing informal rules, the interaction of their incentives will tend to raise transaction costs and reduce the production of wealth in the community”. In addition, North (1990, p. 91) states that “formal rules change, but the informal constraints do not. In consequence, there develops an ongoing tension between informal constraints and the new formal rules, as many are inconsistent with each other.” In that sense, we argue that then foreign subsidiary firms operate in host countries that are distant in terms of formal institutions (i.e. greater FID), the lack of familiarity with the formal institutions in the host country is likely to increase the effects of CD as foreign subsidiaries will rely more heavily on their ability to deal with the less strict and more tacit aspects of the host country institutional environment. In order to test these assumptions, we hypothesize:

H2. FID moderates positively the effects of CD on the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms.

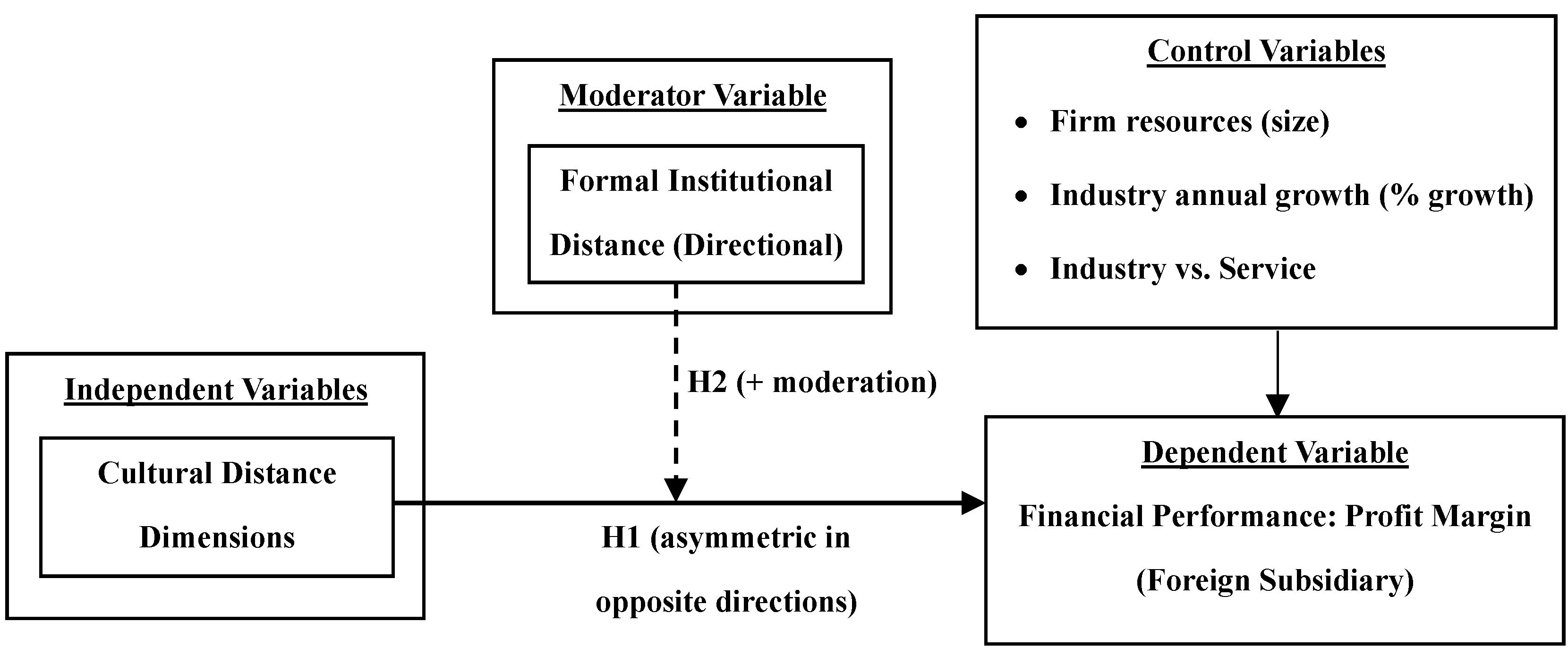

Next, in

Figure 1 we present the general framework of the study.

3. Methodology and Data

To test the hypotheses, we adopt a quantitative approach using the econometric technique of panel data. According to Park (2011) panel data are also called longitudinal data or cross-sectional time-series data. These longitudinal data have “observations on the same units in several different time periods” (Kennedy, 2008, p. 281). For the present study, due to fast paced and volatile institutional conditions in Latin American countries, panel data allowed the researchers to check the patterns and relationships between the variables included in this study through different time periods.

We use data from the Orbis database and a sample that includes over 1450 foreign subsidiaries with approximately 1200 from developed countries and 250 from emerging markets operating in the 10 largest economies in Latin America over a period of 3 years ranging from 2013 to 2015. Latin America provides a relevant context for this study due to “societal, cultural, and economic characteristics that make the region an ideal ‘natural laboratory’ to build and test management theories” (Aguinis et al., 2020, p. 615). Furthermore, the diversity in our data which includes 168 pairs of different home and host countries provide the means to discuss the effects of distances (Franke and Richey, 2010) and make comparisons regarding the implications of distances to the financial performance of foreign subsidiaries from developed countries and from emerging markets.

In order to compare the effects, we separate the data into sub-samples including foreign subsidiary firms from developed countries and from emerging markets. In the emerging markets sub-sample there are 22 different home countries from which 8 are from outside Latin America. In addition, the sample includes 177 foreign subsidiaries from Latin America and 73 from other emerging markets outside the region. In the developed country sub-sample, there are a total of 23 home countries and 10 different host countries in Latin America. Thus, both samples are equally diversified in terms of number of home and host countries which makes the comparison of the results more equitable.

3.1. Dependent Variable

3.1.1. Financial Performance (Profit Margin)

In this study, subsidiary financial performance is measured using profit margin. In turbulent contexts such as in emerging markets, sustaining the company’s profit margins becomes even more challenging and reflects management’s effectiveness at investing in projects that add value (Chopra and Mier, 2017). Profit margin becomes of particularly relevant for this study and it has been extensively employed in the literature (Hitt et al., 1997; Venkatraman and Ramanujam, 1986). Furthermore, profit margin is less susceptible to the influences of different asset valuations that result from the time of investment or depreciation (Geringer and Hebert, 1989, Contractor et al., 2003). When comparing firms in different industries, profit margin provides a more equitable alternative to measure firm performance as firms in different sectors use assets differently. Therefore, financial performance is measured in terms of subsidiary’ profit margin which was obtained from the Obis database.

3.2. Independent Variables

3.2.1. The Direction of the Distances

We follow the approach proposed in previous research (Correa da Cunha, 2019; Correa da Cunha et al, 2022b; Hernández and Nieto, 2015; Konara and Shirodkar, 2018) and use a dummy variable (i.e. true or false condition) to compute distances in opposite directions separately. We use “LH” (Low-High) for distances when the score at the home country is lower in comparison to the score at the host country and “HL” (High-Low) when the score at the home country is higher in comparison to the score in the host country.

Cultural Distance Measurements

CD is measured using Hofstede’s 4 original dimensions which include Power Distance (PDI), Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV), Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS) and Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI). Hofstede’s model was chosen mainly due to its validity, reliability, and its usefulness has been attested over time and in a wide variety of settings (Hofstede, 2001; Deephouse et al., 2016; Kirkman et al., 2006; Li and Parboteeah, 2015; Oyserman et al., 2002). In addition, for the specific context of Latin America this framework has the greatest coverage (Shi and Wang, 2011; Correa da Cunha et al. 2022).

3.3. Moderation Tests

The moderation tests are performed according to Hayes (2013) by analyzing how different (and possible) values of the moderator variable (FID) affect the relationship between CD and the financial performance of foreign subsidiaries. Therefore, the moderator variable is computed by adding and subtracting 1 std deviation to the FID_HL and FID_LH variables. We compute the interaction terms for the different levels of the FID variables (i.e. 1 std deviation up and 1 std deviation down) in each direction and multiply it by each CD variable. Only the results in which moderation was verified are reported.

3.4. Control Variables

Controls include industry sector (1 = industry and 0 = service), and the Industry Annual Growth using the ISIC Rev.3. (International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic. Activities, Rev.3) classification. The data for the host country industry sector growth was collected from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) website for each of the host countries and years that was matched to the ISIC codes from the Orbis database. Firm resources were measured in terms of size as larger firms have access to superior resources. Size is measured using Total Assets reported annually by the firms and collected from Orbis database.

4. Results and Discussion

Preliminary tests were performed in order to select the proper estimator, the Hausman test indicated that the Random Effects estimator to be consistent. Additionally, the White’s test indicated the presence of heteroskedasticity which was corrected using Heteroskedasticity consistent covariance estimation as suggested in the econometrics literature (Andrews, 1991; MacKinnon and White, 1985; White, 1980). Moreover, Lu and White (2014, p. 178) indicate that “a now common exercise in empirical studies is a “robustness check," where the researcher examines how certain "core" regression coefficient estimates behave when the regression specification is modified in some way, typically by adding or removing regressors.” The strength of our results was verified as the size and signal for the coefficients and the characteristics of the models remained stable when new predictors were included or changed in each of the tests that were performed.

For the models including only emerging market firms, a dummy variable (Latin American Firm) was introduced in order to verify if foreign subsidiary firms from Latin America have an advantage when compared to foreign subsidiary firms from other emerging markets outside the region.

Next, we present the results, starting with the models that test the implications of CD, followed by FIDs and finally the models testing the moderation.

4.1. The Asymmetric Effects of Cultural Distance Dimensions on the Financial Performance

Table 1 presents the main results for the effects of CDs on the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms in Latin America.

Results in

Table 1 support hypothesis H1 and confirm that the effects of CD are asymmetric as they depend on the direction and the characteristics of the specific cultural dimensions. Furthermore, industry sector and Industry Annual Growth do not affect financial performance in a significant way while firm resources measured in terms of the total assets affect performance in a positive way. Additionally, the non-significant effects for the Latin American Firm (Dummy) variable indicate that foreign subsidiary firms from Latin America do not have an advantage when dealing with the implications of CD when compared to foreign subsidiary firms from other emerging markets from outside the region.

4.2. The Moderating Effects of FID on the CD and Performance Relationship

Next, we present the results for the moderation effects of FID on the relationship between the different dimensions of CD and the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms. Only the significant results were reported. Due to the contextual characteristics of this study which is set to investigate the case of foreign subsidiary firms operating in the context of emerging markets (Latin American host countries), the moderating effects were only identified for FID towards less developed host countries (FID_HL direction). These findings partially confirm hypothesis H2, and reveal when foreign subsidiary firms operate in host countries with less developed formal institutions compared with the home country, the positive and negative effects of CDs tend to increase.

Next, we present the specific moderating effects of FID on each dimension of CD. We start by presenting the results for the sample including foreign subsidiaries from developed country and then the results for the foreign subsidiaries from emerging markets.

4.2.1. Moderating Effects of FID on the Relation between CD and the Performance of Foreign Subsidiaries from Developed Countries

Table 2 presents the positive moderating effects of FID towards less developed host countries (FID_HL) in the relationship between the Masculinity vs. Femininity dimension of CD and the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms from developed countries. The base models include only the first order components while the interaction models include the interaction term (i.e. the product of the CD variable and the FID variable increased and decreased by 1 std. deviation).

Results for the Masculinity vs. Femininity dimension of CD confirm hypothesis H2 as FID_HL moderates positively the effects of this dimension of CD on the financial performance. These findings provide a complementary view of the results for the effects of CD presented in

Table 1 as they highlight that the negative effects associated to CD towards more Masculinity host countries (MAS_LH) increase when FID towards less developed host countries increase (i.e. high values of FID_HL). The positive moderation is verified by the change in the coefficient for the effects of MAS_LH which is -0.905 (p-value < 0.01) at low values for FID_HL (i.e. shorter distances which are calculated by subtracting 1 std. deviation) and it increases to -3.180 (p-value < 0.01) when 1 std deviation is added to the FID_HL variable. The adjusted R-squared also confirms the moderation as there is a significant improvement when the interaction term is introduced.

Additionally, FID towards less developed host countries moderates the effects of CD towards more feminine host countries (MAS_HL). However, as the direct effects of CD towards more feminine host countries are positive, the positive moderating effects of FID_HL cause the effects of MAS_HL to change to -0.761 (non-significant) when FID_HL are small and the effects increase to a positive 2.360 (significant, p-value < 0.01) when 1 std deviation is added to the FID_HL variable.

The change in the effects of the Masculinity vs. Femininity Dimension of CD on the performance of foreign subsidiaries from developed countries support hypothesis H2 as there is significant increase in the effects corresponding to greater FID towards less developed host countries increase. These findings suggest that FID towards less developed countries can either increase the negative effects of CD towards more masculine host countries as well as increase the positive effects associated to CD towards more feminine host countries. Therefore, the moderating effects of FID on the Masculinity vs. Femininity dimension of CD show that when the quality of formal institutions in the host country is lower, the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms become more dependent on the cultural characteristics of the host country.

Next, in

Table 3, we present the moderating effects of FID towards less developed host countries in the relationship between the Uncertainty Avoidance dimension of CD and the financial performance of foreign subsidiaries from developed countries.

Table 3 shows that when FID towards less developed host countries increases, the effects of the Uncertainty Avoidance dimension of CD in the LH (i.e. towards host countries that score higher) change from 0.273 (non-significant) to a negative -0.478 (p-value < 0.01). By comparing these results (

Table 3) with the negative effects found for UAI_LH on

Table 1 (-0.734, p-value < 0.01), these findings partially support hypothesis H2 as the negative effects of CD towards host countries that score high in terms of Uncertainty Avoidance increase when FID in towards less developed host countries.

On the other hand, the moderation effects of FID-HL in the Uncertainty Avoidance dimension of CD towards host countries that score lower in this dimension of CD change from a significant -6.671 (p-value <0.01) when 1 std deviation is subtracted from FID_HL, to -3.640 and non-significant effect when 1 std deviation is added to the moderator variable. These findings reveal that the interaction of FID and CD can result in different effects depending on the specific characteristics of the cultural dimension.

4.2.2. Moderating effects of FID on the Relation between CD and the Performance of Foreign Subsidiaries from Emerging Markets

Table 4 shows the moderating effects of FID towards less developed host countries on the relationship between the Power Distance dimension of CD and the performance of emerging market firms.

The moderating effects of FID in the relationship between the Power Distance dimension of CD and the financial performance of foreign subsidiaries from emerging markets presented in

Table 4 support hypothesis H2. Results show that the effects of CD towards high Power Distance host countries change from a non-significant –0.428 corresponding to smaller FID towards less developed host countries (i.e. when 1 std. deviation is subtracted from the FID_HL variable) to a positive 5.953 and significant effect when FID towards less developed host countries is increased by 1 std deviation. In addition to the increase in the effects of CD corresponding to greater FID towards less developed host countries, the explanatory capacity of the models (Adjusted R-squared) increases from 0.023 to 0.163 and 0.142 for the models including the interaction terms. According to Hayes (2013) both conditions confirm the positive moderating effects of FID in the relationship between CD and performance.

Therefore, our findings reveal that the greater the FID towards less developed host countries, the higher the positive returns associated with CD towards high power distance host countries on the performance of foreign subsidiaries from emerging market. These results show that the ability of foreign subsidiary firms from emerging markets to obtain positive returns from their ability to accommodate the effects of CD towards high power distance host countries is constrained by the quality of formal institutions in the host country.

There findings provide partial support hypothesis H2 by highlighting that the higher the FID towards less developed host countries, the more pronounced the effects of CD on the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms. By considering the direction of FID, these results suggest that foreign subsidiary firms are more exposed to the positive and negative effects of CD when operating in host countries with less supportive formal institutions.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

We contribute to advancing the knowledge of how cultural and formal institutional distances affect the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms by investigating how FID moderates the relationship between CD and performance. By considering the direction of CD and FID we highlight the asymmetric effects of CD which are moderated positively by FID towards less developed host countries. These findings are consistent with North (1990, p. 47) who posited that formal institutions are “enacted to modify, revise, or replace informal constraints”, as it shows that when foreign subsidiaries operate in host countries characterized by weak formal institutions, the positive and negative effects of CD are likely to increase. In that sense we provide empirical evidences that foreign subsidiary firms are likely to rely more on their ability to cope with the more tacit characteristics and implications of CD when formal institutions in the host country are ineffective.

5.2. Practical Implications

By addressing the interaction hypothesis, our findings reveal that FID towards less developed host countries increase the effects of CD on the financial performance of foreign subsidiary firms in specific ways. Being aware of these implications can help firms to identify alternatives to compensate for the lack of formal institutional support when operating in less developed host countries in order to accommodate the effects of CD more positively. For instance, in regards to the effects of the Masculinity vs. Femininity dimension of CD, our results show that not only the negative effects on the performance of foreign subsidiaries from developed countries associated to CD towards more masculine host countries increase but also that the positive effects associate to CD towards more feminine host countries also increase with greater FID towards less developed host countries. Furthermore, it is shown that the negative effects associated to CD towards high uncertainty avoidance host countries on the performance of foreign subsidiary firms from developed countries tend to increase with greater FID towards less developed host countries. When CD is towards low uncertainty avoidance host countries, greater FID towards less developed host countries causes the relationship between CD and performance to turn non-significant. These findings indicate that CD towards high uncertainty avoidance host countries require “more formal laws and informal rules controlling the rights and duties of employers and employees” (Hofstede et al., 2010, p. 209), whereas greater FID towards less developed host countries seem to cause the effects of CD towards low uncertainty avoidance countries to have a lower and non-significant effect. Moreover, it can be concluded that FID towards less developed host countries makes it more difficult to implement and enforce contracts (Claessens and Van Horen, 2008; Lumineau and Malhotra, 2011) which in turn increases the negative effects associated with CD towards high uncertainty avoidance on the performance of foreign subsidiaries from developed countries.

When it comes to the moderating effects of FID on the relationship between CD and the financial performance of foreign subsidiaries from emerging markets, our findings reveal that when in less developed host countries, these firms seem to take advantage of their expertise in high power distance contexts. Although studies indicate that “the use of power should be subject to laws and to the judgment between good and evil. Inequality is considered basically undesirable; although unavoidable, it should be minimized by political means” (Hofstede et al., 2010, p. 78), our findings show that when in less developed host countries, foreign subsidiaries from emerging markets rely more on their expertise to accommodate in a positive way the effects of CD towards high power distance host countries.

5.3. Limitations and Direction for Future Research

Despite the contributions, we consider that our study has some limitations which provide fertile ground for future research. First, our data enabled us to verify the effects of the different dimensions of CD towards host countries with distinct (opposite) characteristics, however, we consider that despite being important, CD provides a restricted view of how countries differ in terms of informal institutions. In that sense, future research could broaden the discussion by including different aspects of informal institutions such as social ties, level of regional embeddedness, among others. Second, as the main contribution of this study relates to how FID moderates the relationship between CD and performance, future studies could strengthen our findings by investigating how FIDs towards more developed host countries might moderate in a negative way (i.e. suppress) the effects of CD. Thus, we believe that the power of formal institutions to moderate the effects of informal institutional constraints is likely to depend on country profiles and the ability of foreign subsidiary firms to cope with such environments. Future research could explore the diverse institutional settings in different contexts to explore the complex systems of how such moderation operates and how firms’ ownership advantages can interfere in such relationships.

Author Contributions

H.C.d.C.: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, validation. M.A.: writing—review and editing, investigation, formal analysis, validation. D.F.: writing—review and editing, investigation, formal analysis, validation. S.A.: writing—review and editing, investigation, formal analysis, validation. C.F.: writing—review and editing, investigation, formal analysis, validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding support for this research project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguinis, Herman, Isabel Villamor, Sergio G. Lazzarini, Roberto S. Vassolo, José Ernesto Amorós, and David G. Allen. Conducting management research in Latin America: Why and what’s in it for you? Journal of Management 2020, 46, 615–636.

- Beckerman, Wilfred. Distance and the pattern of intra-European trade. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 1956, 38, 31–40.

- Beugelsdijk, Sjoerd, Tatiana Kostova, Vincent E. Kunst, Ettore Spadafora, and Marc Van Essen. Cultural Distance and Firm Internationalization: A Meta-Analytical Review and Theoretical Implications. Journal of Management 2018, 44, 89–130.

- Chopra, Rohit, and Juan Mier. 2017. Profitability Trends in Emerging Markets Setting the Stage for Active Management. New York: Lazard Asset Management LLC.

- Contractor, Farok J., Sumit K. Kundu, and Chin-Chun Hsu. A three-stage theory of international expansion: The link between multinationality and performance in the service sector. Journal of international business studies 2003, 34, 5–18. [CrossRef]

- Correa da Cunha, Henrique. 2019. Asymmetry and the moderating effects of for-mal institutional distance on the relationship between cultural distance and performance: The case of multinational foreign subsidiaries in Latin America. In The Direction of Cultural Distance and the Performance of Foreign Subsidiaries in Latin America Disser-Tations no. 61. Halmstad: Halmstad University Press.

- Correa da Cunha, Henrique, Carlyle Farrell, Svante Andersson, Mohamed Amal, and Dinora Eliete Floriani. Toward a more in-depth measurement of cultural distance: A re-evaluation of the underlying assumptions. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 2022, 22, 157–188. [CrossRef]

- Correa da Cunha, Henrique, Nursel Selver Ruzgar, and Vik Singh. The Moderating Effects of Host Country Governance and Trade Openness on the Relationship between Cultural Distance and Financial Performance of Foreign Subsidiaries in Latin America. International Journal of Financial Studies 2022, 10, 26. [CrossRef]

- Correa da Cunha, Henrique, Mohamed Amal, and James Mark Viminitz. Formal vs. Informal Institutional Distances and the Competitive Advantage of Foreign Subsidiaries in Latin America. Economies 2022, 10, 114. [CrossRef]

- Correa da Cunha, Henrique, Vik Singh, and Shengkun Xie. The Determinants of Outward Foreign Direct Investment from Latin America and the Caribbean: An Integrated Entropy-Based TOPSIS Multiple Regression Analysis Framework. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2022, 15, 130. [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, Alvaro, and Mehmet Erdem Genc. Obligating, pressuring, and supporting dimensions of the environment and the non-market advantages of developing-country multinational companies. Journal of Management Studies 2011, 48, 441–455. [CrossRef]

- Dow, Douglas. 2017. Are we at a Turning Point for Distance Research in International Business Studies? In Distance in International Business: Concept, Cost and Value. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 47–68.

- Gani, Azmat. Governance and foreign direct investment links: Evidence from panel data estimations. Applied Economics Letters 2007, 14, 753–756. [CrossRef]

- Geringer, J. Michael, and Louis Hebert. Control and performance of international joint ventures. Journal of international business studies 1989, 20, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globerman, Steven, and Daniel Shapiro. Governance Infrastructure and US Foreign Direct Investment. Journal of International Business Studies 2003, 34, 19–39. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew.F., 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, second ed. Guilford Publications, New York.

- Hernández, Virginia, and María Jesús Nieto. The effect of the magnitude and direction of institutional distance on the choice of international entry modes. Journal of World Business 2015, 50, 122–132. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization. 1980, 10, 15–41.

- Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2005. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: Mcgraw-Hill, vol. 2.

- Hofstede, Geert. Organising for cultural diversity. Europ. Manag. J. 1989, 7, 390–397. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert, 2001. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across cultures, second ed.

- Hofstede, Geert, Geert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations, Software of the mind. Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for survival.

- Johanson, Jan, and Finn Wiedersheim-Paul. The internationalization of the firm—Four Swedish cases 1. Journal of Management Studies 1975, 12, 305–323. [CrossRef]

- Johanson, Jan and Erick J Vahlne. The internationalization process of the firm: A model knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. J. of Int. Bus. Stud. 1977, 8, 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Art Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi, 2009. Governance matters VIII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996-2008. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (4978).

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Art Kraay and Massimo Mastruzzi. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues1. Hague journal on the rule of law 2011, 3, 220–246. [CrossRef]

- Klasing, Mariko, J. Cultural dimensions, collective values and their importance for institutions. Journal of Comparative Economics 2013, 41, 447–467. [CrossRef]

- Kogut, Bruce, and Harbir Singh. The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies 1988, 19, 411–432. [CrossRef]

- Konara, Palitha, and Vikrant Shirodkar. Regulatory institutional distance and MNCs’ subsidiary performance: Climbing up vs. climbing down the institutional ladder. Journal of International Management 2018, 24, 333–347.

- Kostova, Tatiana. 1996. Success of the Transnational Transfer of Organizational Practices Within Multinational Companies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Kostova, Tatiana. Transnational transfer of strategic organizational practices: A contextual perspective. Acad. of Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 308–324. [CrossRef]

- Kostova, Tatiana and Srilata Zaheer. Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. Acad. of Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 64–81. [CrossRef]

- Magnani, Giovanna, Antonella Zucchella, and Dinorá Eliete Floriani. The logic behind foreign market selection: Objective distance dimensions vs. strategic objectives and psychic distance. International Business Review 2018, 27, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Maseland, Robbert. Parasitical cultures? The cultural origins of institutions and development. Journal of Economic Growth 2013, 18, 109–136. [CrossRef]

- Maseland, Robbert, Dow, Douglas, Piers Steel. The Kogut and Singh national cultural distance index: Time to start using it as a springboard rather than a crutch. J. of Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 1154–1166. [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, Alemu Aye, and Bishnu Kumar Adhikary. Does good governance matter for FDI inflows? Evidence from Asian economies. Asia Pacific Business Review 2011, 17, 281–299. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Klaus E. Saul Estrin, Sumon Kumar Bhaumik, and Mike W. Peng. Institutions, resources, and entry strategies in emerging economies. Strategic Management Journal 2009, 30, 61–80.

- North, D.C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Peng, Mike W. Sunny Li Sun, Brian Pinkham, and Hao Chen. The institution-based view as a third leg for a strategy tripod. Academy of Management Perspectives 2009, 23, 63–81. [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. 1995. Institutions and Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage, vol. 2.

- Selmer, Jan, Randy K. Chiu, and Oded Shenkar. Cultural distance asymmetry in expatriate adjustment. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal. 2007, 4, 150–160.

- Shenkar, Oded. CD revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies 2001, 32, 519–535. [CrossRef]

- Shenkar, Oded, Yadong Luo, and Orly Yeheskel. From “distance” to “friction”: Substituting metaphors and redirecting intercultural research. Academy of Management Review 2008, 33, 905–923. [CrossRef]

- Shenkar, Oded. Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. J. of Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Shenkar, Oded. Beyond cultural distance: Switching to a friction lens in the study of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies 2012, 43, 12–17. [CrossRef]

- Shenkar, Oded, Stephen B. Tallman, Hao Wang, and Jie Wu. National culture and international business: A path forward. Journal of International Business Studies 2020, 53, 516–533.

- Stahl, Günter K., and Rosalie L. Tung. Towards a more balanced treatment of culture in international business studies: The need for positive cross-cultural scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies 2015, 46, 391–414. [CrossRef]

- Stein, Ernesto, and Christian Daude. 2001. Institutions, integration and the location of foreign direct investment. In Global Forum on International Investment: New Horizons for Foreign Direct Investment. Paris: OECD Publications Services, pp. 101–130.

- Verbeke, Alain, Rob van Tulder, and Jonas Puck. 2017. Distance in International Business Studies: Concept, Cost and Value. In Distance in International Business: Concept, Cost and Value. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 17–43.

- Wernick, David A. Jerry Haar, and Shane Singh. Do governing institutions affect foreign direct investment inflows? New evidence from emerging economies. International Journal of Economics and Business Research 2009, 1, 317–332. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2021. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Zaheer, Srilata. Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal 1995, 38, 341–363.

- Zaheer, Srilata, Margaret Spring Schomaker, and Lilach Nachum. Distance without direction: Restoring credibility to a much-loved construct. Journal of International Business Studies 2012, 43, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).