1. Introduction

The decision to institutionalize an elderly person is based on several reasons, including his advanced age, the lack or small number of children, the deterioration of the home or its inaccessibility, cognitive disorders or the absence of the spouse [

1].Although the elderly avoid institutionalization, preferring as much as possible to live in the community, in their houses, the transition to a nursing home becomes an option when the state of health worsens, when physical and cognitive impairments appear and, implicitly, the needs of palliative care, specialized care. Added to these are situations in which family members cannot take care of the person in need, especially if they are also elderly or have other obligations that do not allow them to get involved [

2].

For the elderly, the house is more than a residence, because they feel deeply connected to it, they feel safe, they have familiar objects and a community with common principles and values, a fact that helps them always find resources, resist more easily in the face of risks. This is also the reason why the elderly want to stay at home as much as possible and even spend their last years there [

3].

In what regards the advantages, residential centers for the elderly offer them a safe and hygienic environment, medical care, food and protection from possible abuse suffered at home. On the other hand, the disadvantages consist of social exclusion, excessive sadness, the impossibility of establishing solid social relationships, the diminution or even loss of communication skills [

4].

The elderly person's transition to a nursing home causes other family members to redefine their roles, control and involvement in care diminishing with this move. However, in addition to the reduction of burdens, they may also feel a sense of guilt caused by the decision to institutionalize. However, they can still monitor the care received by the elderly, provide feedback to the staff, but also effectively contribute to their care and maintain the beneficiary's connection with the outside world [

2].

At the same time, this transition also associates several changes for the beneficiary, especially on the style and quality of life. Institutionalization can therefore increase the degree of vulnerability of the elderly who are prone to experience, in addition to loneliness, functional impairments or depression [

1].

Although the Covid 19 pandemic affected all socio-demographic groups, scientific evidence has shown that advanced age is a risk factor associated with a higher lethality of the virus [

5]. Not only did the direct contact with the virus make them more vulnerable, but also the indirect effects of social isolation, embodied in loneliness, limited access to medical services, limited social relationships and reduced accessibility to community life [

6]. However, due to the comorbidities and frailty that characterize them, the institutionalized elderly represented one of the most vulnerable populations to the morbidity and mortality of the SARS COV 2 virus [

2].

Among the measures adopted by residential centers for the elderly in order to limit the spread of the SARS COV 2 virus were the prohibition of group activities, the limitation of movements outside the premises and isolation in their own rooms [

7], the efficient distribution of residents in space ( avoiding overcrowding), establishing hygiene measures, cleaning and disinfecting spaces and devices, control policies and management of infected people [

5], canceling all social activities and restricting all visits [

8]. Thus, the staff of residential centers for the elderly became solely responsible for the transmission of the virus to the residents [

9].

Basically, once all the measures to prevent the spread of the virus were put in place, social relations with other residents, staff and family members, and informal care from the relatives was limited [

10].

Thus, as a result of physical isolation and the impossibility of using common residential spaces, the institutionalized elderly felt the physical, psychological and cognitive consequences, exacerbating a pressing pre-existing problem, namely loneliness. Derived clinical effects consisted of weight loss, the appearance of depressive symptoms, deterioration of cognitive functions, insomnia, but also increased frailty, a consequence of the lack of mobility [

5].Even though adults naturally become frailer and less mobile as they age, the excess sedentariness caused by the COVID 19 restrictions has drastically increased the rate of this decline. In addition, these restrictions constituted a barrier to leisure activities for residents. Even though occupational employment plays an important role in residential centers for the elderly in the sense that they favor the psychosocial well-being and dignity of the beneficiaries, the latter have been forced to spend passive time in their rooms with reduced opportunities for occupational stimulation [

10].

Beneficiary families have tried to adopt various support strategies embodied in various ways of remote care: delivering essential items to the elderly, staying connected through technology, visiting outside with social distancing or behind a glass partition. All of these, however, have been shown to be ineffective for residents with cognitive impairments or those with vision and hearing impairments [

2].

Even if they could not fully compensate for physical visits, alternative ways of contacting the family, namely phone calls, video calls, e-mails or letters, proved useful in the sense that they positively influenced the emotional well-being of residents [

7]. Despite the fact that video calling may be inappropriate for elderly people with dementia, for instance, this form of digital contact has been found to reduce agitation and anxiety in these residents [

10]. Another study, [

11], reinforces this idea, appreciating that the frequency of communication is directly proportional to resident satisfaction. Thus, social support, embodied in the present situation in telephone or video calls, lessened the negative effects of isolation on mental health. More, the support thus received helped them in the sense that they felt listened to and protected.

Thus, in order to support the residents, employees helped them use technology, namely electronic devices, to keep in touch with their family. However, the digital gap between generations has made communication very difficult, a fact that has exacerbated feelings of isolation and loneliness [

1]. Also, the reduced staff and its overload during the COVID 19 pandemic constituted a barrier to alternative means of communication, which is why, in most cases, the digital contact between the beneficiary and the family ceased after the restrictions were lifted [

7].

Despite the dramatic consequences of COVID 19 and, implicitly, the restrictions imposed, the elderly were much more self-confident compared to other age groups, based on a vast life experience. Given the fact that they have experienced, in the past, stressful events and similar moments of crisis, they have developed skills that have led to an increase in the degree of resistance. Thus, if other age groups perceived the pandemic as an element of novelty, the elderly demonstrated greater adaptability [

12].

According to [

11], nursing home residents paid particular attention to spirituality during the COVID 19 pandemic. Religiosity and spirituality helped the elderly to remain calm and confident, being considered both resources and coping skills, with a positive impact on physical health and mental. Given the fact that the elderly are the people most involved in religious activities, spiritual resources can thus constitute a source of resilience to manage the stressful period of the pandemic [

13].

Generically referred to as information disorder, misinformation and fake news have dominated the media scene during the COVID 19 pandemic. The sharing of fake content has called into question both medicine and technology. The fact that the elderly have low experience with digital media makes them more vulnerable and prevents them from detecting manipulative images, clickbait news or any other form of deception [

14]. Thus, mass media or traditional media is considered more credible than social media due to the processing of information using journalistic standards, but also due to sources of information that are verifiable. During the COVID 19 pandemic, the news disseminated information related to death, dramatic aspects that generally produced panic and negative effects. On the other hand, news has given less importance to information about prevention, spread control and healthy practices [

15].

The fear of infection and the lack of a specific treatment for COVID 19, but also the preconceptions related to the vaccine, caused negative emotions, stress and anxiety. Although age is a critical factor in vaccine acceptance, with older people more willing to be vaccinated, this decision was influenced by information sources. During the COVID 19 pandemic, in addition to the large amount of fake news, there were also conspiracy theories about the disease and the vaccine. Thus, misinformation presented as evidence-based could affect vaccination behavior in the sense that the elderly have a lower ability to differentiate between conventional and fake news [

16].

At the same time, social media platforms have spread, in addition to misinformation about the virus, treatment schemes or simple alternative treatments, unscientific remedies and unverified drugs promoted by fake doctors, thus causing people to become negligent, refuse hospitalization and , implicitly, to spread the disease [

17]. The media can thus limit government efforts to inform the population during the pandemic, having a substantial impact on subsequent behaviors [

18]. Also, the promotion by the mass media of the news that the elderly are almost the only demographic group affected by COVID 19, emphasizing their weakness, created a form of stigmatization and increased the level of psychosocial suffering among them [

19].

In addition to increasing care costs, aging also implies diminishing functional abilities and decreasing quality of life. In this regard, occupational therapy can play an important role in maintaining or improving the independence and, implicitly, the mobility of the elderly [

20].

Cognitive decline is a problem characteristic of the elderly in the sense that it can produce dementia and, implicitly, can increase the risk of mortality. Although cognitive decline is associated with a low quality of life in the elderly, its contributing factors include hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, and depression. On the other hand, balanced food diets based on fruits and vegetables, as well as physical activity are associated with a lower risk of cognitive impairment [

21].

At the same time, one of the expressions of aging, considered to be the most visible, is fragility. This is rather a consequence in the sense that it involves the installation of some changes in the physiological systems, the increase of vulnerability and, implicitly, the alteration of the state of health. Repeated falls, disability, dependence on long-term care, hospitalization, but also mortality, are some of the characteristics of the elderly considered to be frail [

22,

23].

Loneliness is also a risk factor for mortality, with older people feeling this more acutely because of the changes and functional losses associated with aging. If social loneliness refers to the lack or diminution of social relationships or social support, emotional loneliness represents the lack of closeness, of intimacy with another person. The latter is experienced, in particular, by the elderly whose partners have died, which is why they live alone and do not have reliable relationships with other people. However, regardless of its specifics, loneliness has negative consequences on both the mental and physical health of the elderly manifested in depression, increased stress level, sudden mood changes [

24]. Thus, loneliness, also defined as an unpleasant subjective state of sensing a discrepancy between the desired amount of affection or emotional support and the one received, is an effect of social isolation, prevalent among the elderly population [

25]. In addition to health consequences, loneliness is also associated with malnutrition, sleep disorders (nighttime insomnia and daytime sleepiness), but also with other risky behaviors such as excessive alcohol consumption and tobacco use [

26,

27].

Although most seniors prefer to remain in the community, in their familiar environment, institutionalization becomes imminent when functional disability or frailty occurs. The latter is defined by weight loss, exhaustion, weakness, slow walking speed and low physical activity. Thus, the chances of institutionalization are up to 5 times higher in the case of the frail elderly, the transition to an asylum can even amplify the loss of autonomy and independence of the elderly [

28]. At the same time, institutionalization is a feasible alternative when the elderly person presents a severe cognitive impairment. Professional care, including medical care, can improve the resident's quality of life, on the one hand, and reduce stress and burden on caregivers, on the other [

29].

Thus, the decision to institutionalize the elderly requires his relocation and acceptance of a new lifestyle, which is why it proved to be very difficult from an emotional point of view. If for some beneficiaries moving to an asylum is associated with the opportunity to socialize and make new friends, others see it as a loss of freedom and independence. Therefore, given that institutionalization is a stressful event by its nature, elderly people who overestimate their ability to care for themselves at home do not understand the need to move, do not cooperate and have difficulties adapting to the new environment [

30].

Another research [

31], considers malnutrition and depression to be two major problems that particularly affect the institutionalized elderly, with a prevalence of 60% and 45%, respectively. Thus, undernutrition indicates an insufficient intake of energy and nutrients, which increases the risk of complications such as infections, falls, frailty and sarcopenia. On the other hand, obesity involves an excessive accumulation of fat, both of which pose health risks [

32]. Elderly people usually consume insufficient amounts of food or inappropriate food, due to reduced basal metabolic rates, low level of physical activity, difficulties in chewing and swallowing, but also due to reduced digestion capacity [

33].

Therefore, the consequences of malnutrition and depression increase the degree of dependence and, implicitly, the risk of mortality. Moreover, there is also a causal relationship between the two by reference to the elderly in that depression, an increasingly common problem among the institutionalized elderly, can cause weight loss. However, very often, depression among the elderly is not diagnosed, thus remaining untreated [

31].

At the same time, approximately 70% of the institutionalized elderly face a decrease in sleep quality, a fact generated by medical conditions, anxiety, stress, fear or other associated factors. Moreover, insomnia is considered to be a facilitating factor of mental disorders, in general, and of depression, in particular, hence its association with difficulties in managing emotions. However, sleep disturbances can be lessened by physical activity that helps institutionalized seniors improve their cognitive function and increase their self-esteem. Furthermore, gymnastics encourages psychosocial interactions and has positive effects on attention and memory, significantly reducing anxiety among the elderly [

34]. At the same time, physical exercises can be a way to prevent and even treat the frailty of the elderly. They can improve gait, increase muscle strength, and decrease weakness [

28].

The residential environment plays an important role in increasing the quality of life of the elderly. Therefore, friendly, safe and comfortable homes are directly proportional to well-being, enabling people to enjoy old age. Also, the infrastructure of the communities of which the elderly are a part (public transport, accessibility to buildings and public spaces) to which is added the promotion of a healthy lifestyle, social participation, entertainment and social services for the elderly represent some of the necessary conditions to lead an autonomous and independent living in old age. So, the physical and social facilities in the proximity of the elderly's homes (including shops, public lighting, green areas, recreational spaces, bicycle paths, medical services) are associated with the functional performance of the elderly. On the other hand, steep or uneven streets, lack of infrastructure for pedestrians, lack of street safety can constitute dangers for the elderly, restricting their participation in the community space [

35].

Thus, walking among the elderly, i.e. walking in the vicinity of the home, helps them maintain their health and stay in their homes as long as possible. To this end, the elderly must benefit from enabling infrastructure, including adequate sidewalks, seating areas, and chairs or benches along their route [

36].

So, physiological conditions, community design, social participation and social support strongly influence the psychological health of the elderly. However, [

37] appreciates that the elderly, accustomed to living in areas with a developed infrastructure and increased security, also present greater material and spiritual demands. For this reason, dissatisfaction makes them prone to negative emotions and, implicitly, to feel an acute need for emotional support (telephone conversations, the company of family members). Thus, in order to reduce the risk of psychological problems, stress, but also feelings of loneliness and abandonment among the elderly, the younger generations must offer them emotional support.

However, elderly people living in the community are prone to frequent falls, with about one third of them experiencing this problem. In addition to the physical effects (bruises, fractures), many of the falls also have psychosocial consequences in the form of isolation, fear or even depression. Thus, falls in the elderly may require medical treatment, but in extreme cases, they may also cause the death of the elderly [

38].

A high risk of falling is caused by malnutrition. Even if it has a higher prevalence among the institutionalized elderly, those in the community also face this pathology, weight loss being a predictive factor in this regard. Thus, malnourished elderly are prone to injury, long-term hospitalizations and even slower recovery from illness, thus a shorter life expectancy [

39].

However, the falls of the elderly can also be caused by the number of medications they administer and, implicitly, by their adverse effects, by functional disorders or even by an inappropriately organized environment. Other predictive factors of falls among the elderly may also be certain comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension [

40].

Considering the aspects mentioned above, the purpose of our paper was to examine the ways in which the care centers for the elderly acted and adapted, mainly during the pandemic period from the perspective of the beneficiaries, the employees and the managers of those centers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Purpose and objectives of the research

The purpose of this research was to study the ways in which the care centers for the elderly acted and adapted, mainly during the pandemic period from the perspective of the beneficiaries, the employees and the managers of those centers. Note: for simplification, we will call the elderly people from those centers with the term 'beneficiaries'.

Related to the purpose stated above, we also formulated a series of objectives, as follows:

O1. Measuring the general level of satisfaction of beneficiaries in specialized care centers.

O2. Identifying the main difficulties faced by the beneficiaries during the institutionalization period and during the pandemic

O3. Identification of the main medical/therapeutic services that the beneficiaries receive.

O4. Identification of the main leisure activities of the beneficiaries.

O5. Evaluation of beneficiaries' perceptions regarding the pandemic period and how their general health, mental health and personal needs were affected.

O6. Identification of the beneficiaries' proposals for improving the way of life in the care centers

O7. Identification of perceptions regarding the pandemic period from the perspective of employees and managers of the care centers

2.2. Hypotheses of the research

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The satisfaction with life in care and support centers treatment is significant different with gender, initial residence environment, the life stage and time spent in this kind of organizations.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). There are statistically significant differences in the calls of therapies in care and support centers according to the gender of respondents and to the age category.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The biggest difficulties encountered during the pandemic were significant different with gender, residence environment, the life stage and time spent in care center.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). The more the pandemic affected the physical condition of the beneficiaries, the better was the perception of the relationship with the staff in the care centers.

2.3. Data collection method

We used for this research a mixed methods design named more precisely convergent parallel design [

41] (pp.111-113). These designs refer to the implementation of quantitative and qualitative techniques at the same time, both being equally prioritized. The research was conducted between February – June 2022.

From a quantitative perspective, we applied a questionnaire to a quota sample of beneficiaries of care centers for the elderly in Timis County, Romania, and from a qualitative perspective, we applied interview guides to three target populations (beneficiaries, employees of care centers, managers of these centers).

Questionnaires and interview guides were applied in the following elderly care centers:

The socio-medical care center "St. Francis" Bacova, DGASPC Timiş – Centers 1-4, DAS Timiş, Periam Neuropsychiatric Recovery and Rehabilitation Center, Gavojdia Neuropsychiatric Recovery and Rehabilitation Center, Neuropsychiatric Recovery and Rehabilitation Center, Care and Assistance Center, Ciacova.

2.4. Sample

The sample of our research consists of retired people who live in the state or private asylums in Timis County Romania listed above. The subjects were selected by controlled quota sampling. The volume of the sample was 430 institutionalized elderly. The structure of the resulting sample was recorded thus following a series of independent variables: gender (male-49%, female-51%), initial residence environment (urban-53%, rural-47%), the life stage (adults under 64 years old [ 20%], young-old, ages 65–74 [50%], the middle-old, ages 75–84 [20%]), and the old-old, over age 85 [10%]), time spent in care and support center (up to 2 years -28%; 2-4 years -33.5%; 4 years and over 38.5%) and the type of care centers (public and private). All those quotas were established having as a model the characteristics of the research population transposed into a descriptive matrix [

42]. Furthermore, considering the qualitative research, the interview was applied to 31 beneficiaries- people living in the care centers, to 7 employees and to 4 managers.

2.5. The research instruments

The questionnaire applied to the beneficiaries can be seen in Appendix 1 and we note that it is structured on a series of thematic areas as follows:

According to the objectives of the research, the questions from the questionnaire were used either for descriptive data or for stating and testing the hypotheses. Considering the qualitative research, the three interview guides used in the discussion with the beneficiaries, with employees and with managers, can be found in Appendix 2. In the interview guide applied to the beneficiaries we took into consideration dimensions such as: adjusting to the changes imposed by the move to the care center, adapting to the changes that have occurred due to the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in care mode due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the most important task they had to accomplish during the COVID-19 pandemic, contracting the virus, losing loved ones due to the COVID-19 virus, mood during the COVID-19 pandemic, solidarity at the level of the institution's employees, respondent’s greatest achievement, respondents' relationship with God. In the interview guide applied to employees we took into account dimensions such as: physical distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, the greatest difficulty encountered by the beneficiaries, losing relatives, friends and/or loved ones due to the COVID-19 virus, the most important task they had to accomplish during the COVID-19 pandemic, mood during the COVID-19 pandemic, solidarity in the behavior of the institution's employees and beneficiaries, changes in the activity of the institution during the COVID-19 pandemic, care of the elderly in other institutions, respondents' relationship with God. Furthermore, in the interview guide applied to managers with measured the following the dimensions: physical distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, the greatest difficulty encountered by the beneficiaries, losing beneficiaries, relatives or acquaintances due to the COVID-19 virus, the most important task they had to accomplish during the COVID-19 pandemic, mood during the COVID-19 pandemic, solidarity at the level of the institution's employees and beneficiaries, changes in the activity of the institution during the COVID-19 pandemic, changes that managers would like to make in the future, models of good practices identified in other institutions, respondents' relationship with God.

2.6. Data analysis

The data collected after applying a questionnaire in the care centers were analyzed with the 20 version of the program Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). The analyzed variables were: a word describing the life in the care and support center, reason to be in support center, seniority in center, decision to stay in the center, Likert scale about satisfaction with the way of treatment in the center, six Likert scales about satisfaction with different services, general attitude of the staff, the biggest difficulty encountered in centers, kinds of medical/therapeutic services, main relaxation activities, communications with family members or other acquaintances/close people. For the pandemic situation the variables were: a word describing the life in the care and support center during pandemic, physical health affected by Covid 19, mental health affected by Covid 19, emotional states during the pandemic, concerns during pandemics, activities allowed during the pandemic, activities that miss the most, physical distancing measures, quality of the services in care centers, biggest difficulty encountered during the pandemic, kinds of contacts with family members, kinds of communications with family members, relationship evolution with family members, digital communications, staff attitudes during the pandemic, evaluation of relations with staff, socialization with beneficiaries, ways of socialization, emotional states during the pandemic, needs respect, suggestions for improving the way of life in the care center. To these are added the socio-demographic variables.

In our analysis we included as predictors gender, age categories, initial residence environment, the life stage and time spent in centers. In order to test the hypothesis, we used the construction of some statistical indexes, parametric Independent T Test, Kruskal-Wallis non parametric test, Chi Square test of independence, Spearman correlation.

4. Discussion and conclusions

In our research we aimed to examine the ways in which the care centers for the elderly acted and adapted during the pandemic period, by taking into account the opinions of the beneficiaries, of the employees and of the managers of those centres. In this regard, in our research we used a mixed method approach, by applying a questionnaire to the beneficiaries of the care centers and also by conducting interviews with beneficiaries, employees and managers of the care centres.

Considering the results of the quantitative research, our research showed that the institutionalized elderly described, in general, the care centres while using positive words, and that most of the elderly were institutionalized because they remained alone, with having no other people to care for them. However, a significant number of the respondents also declared that they were institutionalized due to the fact that they had health problems which required assistance that could no longer be provided at home.

Taking into account the beneficiaries’ satisfaction with their life in the care centre, the results of the research revealed that most respondents were mainly satisfied with their life and the level of satisfaction does not differ depending on their gender or on their initial living environment (urban/rural). However, the research revealed differences depending on the age of the respondents in the sense that adults under 64 years old were significantly more satisfied than adults aged 65 to 74, but also that adults aged 75 to 84 were significantly more satisfied than those aged 65 to 74. In this regard, although the results showed differences according to age, we could conclude whether the level of satisfaction with the life in the centres increases or decreases with age. Thus, in order to clarify the matter, this issue could be also analysed from a qualitative perspective.

Moreover, the findings showed that the time spent in the care centre can influence the beneficiaries’ level of satisfaction with their life. In this regard, the results revealed that those who spent up to two years in the care centres were significantly more satisfied than adults who lived there for a period of 2 to 4 years.

Given the difficulties the elderly experienced in the care centres, the main difficulty mentioned was the impossibility of being close to loved ones, it being followed by the difficulty of adapting to the living conditions within the centre. Hence, the institutionalized elderly were affected by the fact that while being in the centre, they were away from their family and friends, and by the fact that they had to adjust to a new way of living, compared to the one they had at home. In this regard, our research is in line with a previous study [

4], which emphasized the disadvantages of living in a care centre, disadvantages such as social exclusion, or the impossibility to establish solid social relationships.

Considering the type of medical services they usually receive, most respondents declared they receive therapeutic massages, that they do therapeutic gymnastics, and that they receive physical therapy. Thus, as expected, the results of the research showed that gender and age are elements that influence the type of medical help received by the beneficiaries. In this regard, men requested to a greater extent than women therapeutic massages and medical assistance, while women requested more than men recuperative gymnastics, physical therapy, or assistance in basic activities. Also, adults aged 65 to 74, were the ones who requested therapeutic services more than the other age groups categories.

Taking into account the main leisure activities carried out by the beneficiaries, the findings revealed that most respondents declared they mostly watch TV shows, that they play board games with the other residents or that the take walks in the inner courtyard of the centre.

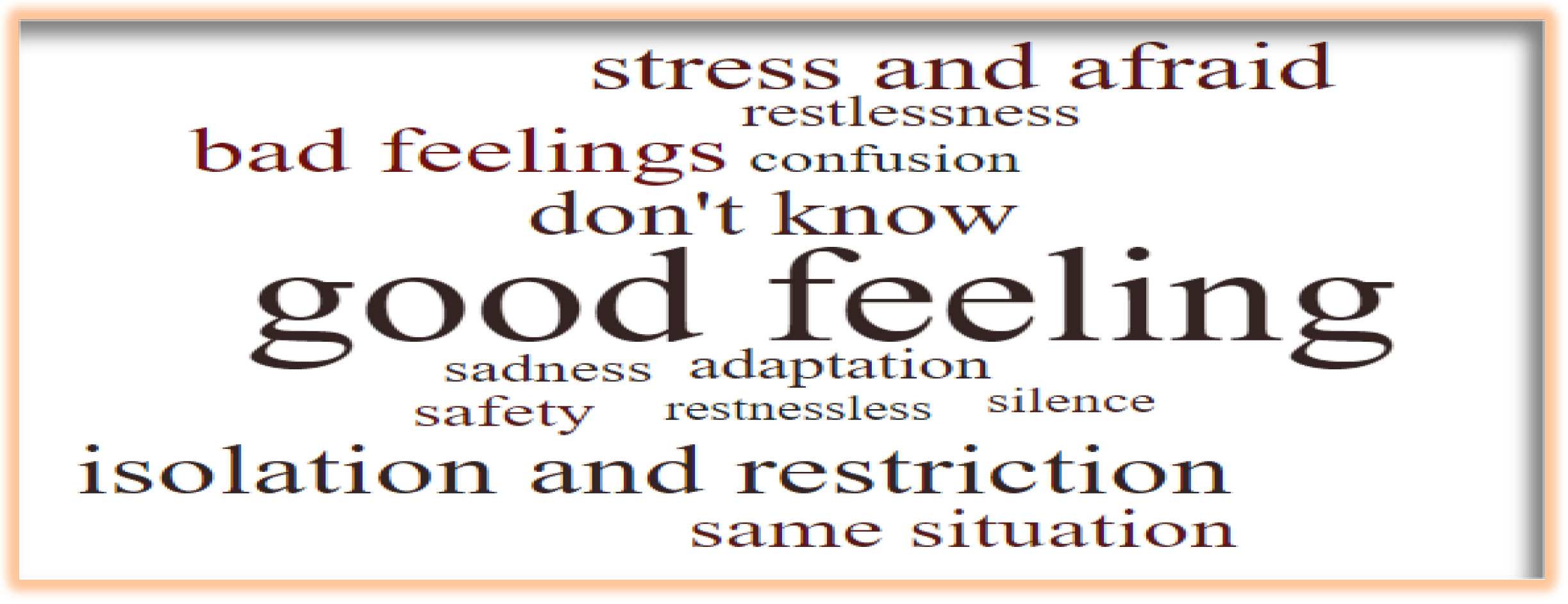

In the context of the COVID – 19 pandemic, the beneficiaries described the period while using positive but also negative words such as isolation, restriction, stress. The respondents considered to a small extent that the pandemic influenced the process of improving their physical health, and most of them declared that their need have been met to a great extent during this period. However, most respondents stated that they have felt “alone, restless, “nervous”, “helpless” and sad, during the pandemic and the research revealed that these emotional states were not influenced by the gender of the respondents. In other words, we found no differences in the emotions felt by the elderly depending on their gender.

Given the restrictions the elderly had to comply with in the pandemic period, our research is in line with previous studies which described similar measures taken in order to assure the well-being of people, measures such as the prohibition of group activities, the limitation of movements outside the premises, isolation in their own rooms [

7,

10], and limiting all social activities and restricting all visits [

8]. Hence, most of the respondents of our research mentioned restrictions such as: having fewer roommates, impossibility to play board games, wearing masks, limitation of the number of people who had access to common spaces and limitation of the time they were allowed to spend in the common spaces. Hence, even though we expected beneficiaries to develop negative attitudes towards the staff of the care centres in the pandemic periods, the results showed that most respondents had positive opinions, them considering the quality of the services they received to be good and very good.

Furthermore, according to the results of the research, the measures taken within the centres were quite restrictive, the beneficiaries not being allowed to watch TV shows, or take walks in the inner courtyard of the centre, or to socialize and interact with the other members of the centre. In this regard, in the pandemic period, the elderly missed the most the possibility to take walks outside the centre and the possibility to socialize with the other residents.

When being asked to state the biggest difficulty encountered during the pandemic, most of the respondents referred to the impossibility to communicate with family members / close persons, to the fact that they had to adapt to the new living conditions in the centre, that they weren’t allowed to interact with the other members of the centre, and that their feelings of loneliness increased. From this perspective, our research is in line with a previous study [

6], which highlighted that the pandemic increased the elderly’s feeling of loneliness and limited their social relationships. Comparing the respondents of the elderly about difficulties encountered in general and in the COVID – 19 period in particular, we observed that those difficulties are similar in the sense they refer to the idea of adapting to a new lifestyle and to the idea that institutionalization and the pandemic both affected communication with family members or friends. Moreover, the research showed that variables such as age or living environment did not influence the opinion about the main difficulties encountered, but the opinion of the respondents was influenced by age and time spent in the care centre. In this regard, while the main difficulty mentioned referred to the impossibility to communicate with family members, the dominant percentages of the respondents who felt this difficulty was represented by adults aged 65 to 74 and by those who had been in the centre for a period of 2 to 4 years.

Considering the way beneficiaries managed to maintain communication with their family members or loved ones, the finding indicated that the communication process was mainly maintained through the usual phone calls. We expected the elderly to communicate with friends or family through video calls, but due to lack of technology skills and knowledge, most of them resorted to phone calls. From this perspective our study is in line with a previous study [

43], which showed that even if they have phones, the elderly do not usually use apps that require internet.

Furthermore, face to face interaction with the family members was not possible during the pandemic, and the interesting results of our research showed that even in these conditions, most respondents declared their relationships with family members remained the same, and some of them even stated that they improved. A possible explanation for this result could be represented by the fact that, it is possible that during the pandemic the families were more concerned with the well- being of the institutionalized elderly and as a result, they may have called them more often compared to the pre-pandemic period. This idea is indirectly supported by a previous study [

11], which showed that the frequency of communication influences the satisfaction of the beneficiaries, and that the social support received through the phone calls decreased the negative effects of isolation on the mental health of the patients.

Similar to the attitude towards the relationship with family members, the research revealed that the elderly were satisfied with the interactions they had with the staff of the care centres and they even mentioned that in the pandemic period, the employees paid more attention to them than before. However, when the role of the pandemic in influencing the opinion of the elderly about the interaction with employees was measured, the results showed that the more important the influence of COVID – 19 was, the more the beneficiaries tended to perceive in a negative manner the relationship with the employees.

Taking into account the suggestions of the beneficiaries regarding improving the way of life of residents of the care centres, the main suggestions mentioned referred to: developing more collective/recreational activities, offering residents more freedom of movement, improving the spaces of the centres, encouraging the employees to have more empathy and respect for the patients, offering the possibility to receive more visits from family and friends, or taking measures in order to reassure discipline and peace within the centres. Such measures should be taken into consideration by the employees and the managers of care centres and the matter should also be approached in detail in a future research.

Considering the results of the qualitative research, in the context of the perception of the beneficiaries, the results showed that: most respondents stated that they adjusted rather well to the changes imposed by their move, but they had a hard time adapting to the changes which took place due to the COVID – 19 pandemic. The results of the qualitative research are similar to the results of the quantitative research in the sense that in both types of research, the beneficiaries stated that their main difficulty was represented by the impossibility to communicate or receive visits from family and friends. Moreover, the beneficiaries described the attitude of the employees as being good or acceptable.

Given the opinions of the employees, the findings revealed that physical distancing measures during the pandemic comprised the strict isolation of the beneficiaries, that the activities developed within the centre decreased significantly, that the main measure taken referred to isolating the elderly from their families and from the community and that their work hours increased. The most important task that employees had was to make sure the beneficiaries comply with the social distancing rules, they generally tried to have a good mood in their interactions with the patients and the employees observed that the beneficiaries manifested sadness, confusion, anger, frustration and even desperation during the pandemic period. Most of them stated they experienced solidarity from their colleagues or from their managers, and significant changes took place within the centre in the pandemic period, changes such as: isolation, the need to wear masks, social distancing.

In the context of the opinions of the managers, the findings showed that managers highlighted the inconsistencies between the measures imposed by the government at national level, they emphasized the difficulty to comply with all the measures in order to protect both the health of the beneficiaries and of the employees. Other difficulties encountered were represented by bureaucracy, having access to protective equipment, or the deficit of personnel. Given the most difficulty encountered by the beneficiaries, the managers stated that the elderly had a hard time understanding what was happening, that they had difficulties due to the fact that they had to remain isolated and they no longer had the opportunity to socialize with their relative or with the other members of the centre. Considering the most important task they had, managers declared that they struggled with keeping things normal, that they had to make sure the health of the beneficiaries and of the employees is protected, and that they had to offer updated information to the beneficiaries and to the employees. Managers described their mood as being stressed and even overloaded and they perceived the beneficiaries to be anxious and afraid. Furthermore, the managers also highlighted that they observed solidarity between the employees and the beneficiaries and they mentioned a series of measure which they would like to take in the future to improve the activity of the care centre. The main measures mentioned were represented by: keeping and improving discipline in the activities with beneficiaries, improving the ties between beneficiaries and employees, training the personnel for potential special situations that may require changes in the organization, hiring new personnel, improving teamwork by integrating the beneficiaries in the team, or improving the connections and the involvement of the local community.

Hence, both the employees and the managers were aware of the difficulties encountered by the beneficiaries during the pandemic, they tried to maintain a positive mood in their interactions with the beneficiaries and they tried to protect their health and well- being by complying with the social distancing rules. Moreover, the pandemic period generated feelings of solidarity between the beneficiaries and the employees and the pandemic also made managers aware of some measures they require to take in order to improve the way the care centres function.

Therefore, considering the theoretical and practical implications of our paper, from a theoretical point of view, our research contributes to the literature on the effects of the pandemic at the level of the elderly. From a practical perspective, our research offers a view on the lifestyle and struggle of the institutionalized elderly during the pandemic, it raises awareness regarding the struggles of the beneficiaries as well as of the employees and managers of these institutions, and it offers a series of measure which could be taken in account by managers in order to improve the activity of the care centres.

4.1. Limitations and future research directions

Considering the limitations of the research, one limitation is represented by the fact that the study was conducted only in a specific area of Romania, Timis county, and thus the results can not be generalized. However, the results are relevant considering that most care centres had to comply with the same rules during the pandemic, but in order to obtain a larger view on the matter of the lifestyle of the institutionalized elderly during the pandemic, a future research should take into consideration care centre from other regions of Romania and even care centre from other countries.

Another limitation refers to the fact that we obtained only the opinion of the institutionalized elderly and a future research should considering examining the opinion of the elderly that had to stay at home during the pandemic too, in order to analyse further if the COVID -19 pandemic influenced differently the lifestyle and the mental health of the elderly who stay at home and of the institutionalized elderly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C., C.G., and L.P.; Methodology, F.A., C.G., C.B., and M.C.B..; Software, A.N. and C.C..; Validation, C.C., M.C.B., C.B., and L.P,.; Formal Analysis, C.C., A.N..; Investigation, C.B., G.C., F.A., L.P., and D.B..; Resources, C.G., C.B., G.C.,L.P., G.C, and F.A.; Data Curation, C.C., A.N., M.C.B., C.G., C.B, F.A., and L.P.; Writing – Original draft preparation, C.B., C.G., L.P, G.C., F.A., A.N., M.B., and M.C.B.; Writing – Review & Editing, C.C., C.B., C.G., M.C.B., F.A., L.P.,G.C., A.N., M.B., and D.B.; Visualization, C.C., C.G., C.B., L.P., M.B., M.C.B., and A.N..; Supervision, C.C..; Project Administration, C.C., C.G. A.N., M.C.B.

Appendix A. Questionnaire applied to the beneficiaries

A. First of all, please answer some questions referring to your life in the healthcare centre/old age home before the start of the COVID 19 pandemic.

A1. Which is the first word that comes to your mind when you think about your lifestyle in the health care and assistance centre?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

A2. Why are you in this centre?

because of my poor health I need supplementary care which cannot be offered at home

the members of my family did not have the possibility to offer me the necessary care

I remained alone and I do not have other people to take care of my wellbeing

other.......................

A3. Since when are you a resident of this home?

less than 1 year

one year

3 two years

three years

four years

more than 5 years

A4. Concerning the decision to come to this centre, this was made:

A5. On a scale of 1 to 7, how satisfied are you with the way you are treated in the healthcare centre?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Extremely dissatisfied

very dissatisfied

quite dissatisfied

neither satisfied nor dissatisfied

quite satisfied

very satisfied

extremely satisfied

A6. On a scale of 1 to 7, how satisfied are you with the following services of the healthcare centre?

1

Extremely dissatisfied

very dissatisfied

quite dissatisfied

neither satisfied nor dissatisfied

quite satisfied

very satisfied

extremely satisfied

the food you are offered 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Entertainment opportunities 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

the activities organised by the centre (trips, events)1 2 3 4 5 6 7

the medical care from the staff 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

accommodation services 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

A7. Do you consider that in general the staff’s attitude towards you is:

A8. Which is, in your opinion, the biggest difficulty you have encountered since you are in this centre?

- 1.

The impossibility to be with the loved ones

- 2.

the communication with the members of the family/close friends

- 2.

socialisation with the other residents of the healthcare centre

- 3.

adjusting to the living standards within the healthcare centre

- 4.

the enhancement of the loneliness feeling

- 5.

the relationship with the staff

- 6.

other.........................................................................................................................

A9. In your particular case, what kind of medical/therapeutic services do you regularly benefit from within the healthcare centre?

- 1.

psychological assistance

- 2.

assistance in achieving the basic activities (hygiene, moving, feeding)

- 3.

kineto-therapy

- 4.

therapeutic massage

- 4.

recovering gymnastics

- 5.

others.............................................................................................................................................

A10. The main relaxing activities that you currently do in the centre are:

Reading

Watching TV shows

Walks in the centre’s yard

Socialisation with other residents by means of society games

Maintaining fitness by doing easy physical exercises

Participating in music evenings

Others....................................................................................

A11. What is the activity that you like the most within the centre?

Reading

Watching TV shows

Walks in the centre’s yard

socialisation with other residents by means of society games

maintaining fitness by doing easy physical exercises

participating in music evenings

others....................................................................................

..........................................................................................................................

A12. How do you usually communicate with the members of your family or other acquaintances/close friends?

B. Next, I would kindly ask you to answer some questions referring to your lifestyle in the centre during the COVID 19 pandemic.

B.1 How would you describe in one word your way of living in the centre after the start of COVID 19 pandemic? .........................................................................................

B2. On a scale of 1 to 7, please express the agreement with the following statements referring to your life in general:

- 1.

definitely disagree

- 2.

disagree

- 3.

slightly disagree

- 4.

neither agree nor disagree

- 5.

slightly agree

- 6.

agree

- 7.

strongly agree

- a)

In general, my life is very close to my ideal life 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

- b)

My life conditions are excellent 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

- c)

I am satisfied with the life I have 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

- d)

Until now I have obtained the important things that I have wanted in my life 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

- e)

If I could live my life again, I would not change anything 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

B3. Having in view your state of health, in what degree do you think the COVID 19

pandemic has affected the process of maintaining/improving your physical health?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Extremely low degree

Very low degree

Neither low nor high degree

High degree

Very high degree

Extremely high degree

B4. To what degree do you consider the impossibility to socialise with other residents during the pandemic has affected your psychic health?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Extremely low degree

Very low degree

Neither low nor high degree

High degree

Very high degree

Extremely high degree

B5. What emotional states did you experience during the pandemic? (multiple answer)

B6. Which of these emotional states did you feel the most during the pandemic? (only one answer)

B7. During the pandemic you were mostly preoccupied with:

your own health

the health of your family members

the health of your friends/acquaintances

I do not know/ I do not answer

B8. Having in view the relaxation activities in the centre, what kind of activities you were not allowed to do during the pandemic?

reading in public spaces

walking in the yard of the centre

relating with the other residents by means of society games

watching TV shows in the common/public spaces

participating in music evenings

other........................................................................................

B9. Among the relaxation activities that you were not allowed to do during the pandemic which one did you miss the most?

B10. Taking into consideration the protection measures against infection or spread of the virus, what kind of physical distancing measures were taken in the centre?

- 1

the limitation of the number of people who have access in the communal spaces

- 2

the limitation of the time spent in the communal spaces of the centre

- 2

the interdiction of the socialisation by means of society games

- 3

the diminution of the room-mates’ number

- 4

the achievement of the communal activities with the obligation of wearing a mask

- 5

others..........................................................................................

B11. On a scale of 1 to 7, how do you appreciate the quality of services offered by the healthcare centre in the context of COVID 19 pandemic?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Extremely bad

Very bad

Quite bad

Neither bad nor good

Quite good

Very good

Extremely good

B12. Which was the biggest difficulty that you have encountered during the pandemic in the centre?

1. the impossibility to socialise with the other residents

2. the impossibility to communicate with the family members/close friends

3. adjusting to the new conditions of life in the centre

4. enhancing the loneliness feeling

5. relating with the staff

6. other....................................

B13. Having in view the relation with the family members/close friends to what degree did you keep in touch with them during the COVID 19 pandemic?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Extremely low degree

Very low degree

Neither low nor high degree

High degree

Very high degree

Extremely high degree

B14. What way of communicating with your family members/close friends did you use mostly during the pandemic?

B15. Referring to your relationship with family members/close friends during the pandemic, do you consider that this relationship:

B16. In the context of COVID 19 pandemic, were your family members/close friends allowed to visit you in the centre?

B17. Concerning the technology, how often did you communicate on video with the closed people outside the centre by means of mobile applications?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Extremely rare

Very rare

Quite rare

Neither rare nor often enough

Often

Very often

Extremely often

B18. Taking into consideration the relationship with the staff in the centre during the pandemic do you consider that the employees’ attitude towards you was:

B19. As compared to the period before the pandemic, did you feel that during the pandemic the staff has given you:

B20. Next, I would kindly ask you to express the agreement with the following statements:

- 1.

Strong disagreement

- 2.

Disagreement

- 3.

Rather disagreement

- 4.

Neither disagreement nor agreement

- 5.

Rather agreement

- 6.

Agreement

- 7.

Strong agreement

- 1.

The centre employees were more reticent towards me during the pandemic 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

- 2.

For the assistants and caretakers in the centre, my needs represented a priority during the pandemic 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

- 3.

The assistants and caretakers socialised less with the beneficiaries during the COVID 19 pandemic 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

B21. To what degree could you socialise with the other residents of the healthcare centre during the pandemic?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Extremely low degree

Very low degree

Neither low nor high degree

High degree

Very high degree

Extremely high degree

B22. What are the socialising ways with other people who live in the same centre in the context of COVID 19 pandemic?

We have watched TV shows in the communal spaces respecting the rules of physical distancing

We have socialised by means of phone calls

We have socialised by means of video calls with mobile applications

others......................

B23. Thinking about the emotional states created by the impossibility/reduced possibility of socialising with other members of the centre, most often during the pandemic you felt:

B24. To what degree do you consider that your needs were respected in the context of the COVID 19 pandemic?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Extremely low degree

Very low degree

Neither low nor high degree

High degree

Very high degree

Extremely high degree

B25. If you were the decision maker, which were the first three measures you would implement in order to improve the lifestyle of the residents of the health care centre?

............................................................

...........................................................

............................................................

B26. Where did you find out what the pandemic did in the country? .............................................

B26. Whom do you trust in the most within the centre?

C. In the end, please offer us the answer to some identification questions :

C1. Your gender

C2. Your age

...........................................................................

C3. Do you come from the:

C4. The last graduated school

primary school

secondary school

high school

faculty

master

6ther………………………………

C5. The field you worked in:

- 1.

IT

- 2.

Sales

- 3.

Services

- 4.

Health

- 5.

Education

- f)

Other..................................

Thank you for your answer!

Appendix B. Interview guides

B1. Interview guide - the way of life of elderly people in care centers and the changes brought about by the covid-19 pandemic

− How did you adjust to the changes imposed on your way of life when you moved to the care center ?

− How have you adapted to these changes after the start of the covid-19 pandemic?

− What changes have you noticed in your grooming?

− Which changes of this type did/do you consider exaggerated, erroneous or even abusive? How did/do you deal with them?

− What has been the most important task you have had or still have to complete since you have been in the care facility? (To yourself, to your family or to someone else.)

− Have you contracted covid-19? Do you want to talk to us about this fact?

− Have you lost loved ones, relatives or acquaintances to this disease?

− What about someone else who did not get this disease, but did not receive the necessary/timely medical care as a result of the imposition of anti-covid measures?

− How would you characterize the current mood of downtown residents?

− But that of the management of the institution and the care staff?

− Do you think that the pandemic has brought with it a change for the better in the consciousness and behavior of peers? (Including you, the staff, the management of the institution).

− What do you consider to be the greatest achievement of your life?

− Tell us about your relationship with God.... Are you a believer?

− Would you like to add anything else? ------------

− Your gender is

− Your age in years is

− You come from the environment

− Last school completed

− The field in which you worked

B2. Interview guide - challenges for care staff in residential care and the changes brought about by the covid-19 pandemic

− What concrete physical distancing measures were you able to take/respect in the care of the beneficiaries and in the usual activities in the institution?

− How would you characterize the sanitary measures in the country imposed during this period?

− How did these measures influence the way you did your business? What was the biggest difficulty you encountered in this regard?

− What do you think was the biggest difficulty faced by your beneficiaries?

− Have you lost beneficiaries, relatives or acquaintances to this disease?

− But someone who did not get sick from this virus, but did not receive the necessary medical care / in a timely manner as a result of the imposition of anti-covid measures?

− What has been the most important task you have had or still have to complete in relation to your own conscience and to the beneficiaries?

− How would you characterize the current mood of downtown residents?

− What about yours and the care staff?

− Have you noticed a real solidarity in the behavior of the institution's employees (managers, care staff), as well as the beneficiaries after the pandemic?

− Do you think that the pandemic has brought with it a change for the better in the consciousness and behavior of peers? (Including you, the staff, the management of the institution, the beneficiaries).

− What changes have occurred in the activity and personnel scheme of the institution? (number/period of quarantines, resignations, layoffs, changes regarding involvement in direct activity with beneficiaries, employment, etc.)

− How did you find out that care for the elderly would be done now in similar institutions, both in the country and abroad?

− Tell us, if you can, about your relationship with God. How has faith influenced the realities you have experienced in the past year?

− Would you like to add anything else?

− Your gender is

− Your age in years is

− Last school completed

− Your experience in aged care is:

− Your job description provides care and responsibilities towards ..../ (number of) beneficiaries.

B3. Interview guide- the challenges of managers of elderly care centers during the pandemic

− What concrete physical distancing measures were you able to take/respect in the care of the beneficiaries and in the usual activities in the institution?

− How would you characterize the sanitary measures in the country imposed during this period?

− How did these measures influence the way you did your business? What was the biggest difficulty you encountered in this regard?

− What do you think was the biggest difficulty faced by your beneficiaries?

− Have you lost beneficiaries, relatives or acquaintances to this disease?

− But someone who did not get sick from this virus, but did not receive the necessary medical care / in a timely manner as a result of the imposition of anti-covid measures?

− What has been the most important task you have had or still have to complete in relation to your own conscience and to the beneficiaries?

− How would you characterize the current mood of downtown residents?

− What about yours and the care staff?

− Have you noticed a real solidarity in the behavior of the institution's employees and the beneficiaries after the pandemic?

− Do you think that the pandemic has brought with it a change for the better in the consciousness and behavior of peers? (Including you, your beneficiaries, and your institution's employees.)

− What models of good practice do you know in similar institutions, both in the country and abroad? ------------

− What changes occurred/imposed in the organization of the institution's activities during the pandemic? (Resignations, quarantines, changes regarding involvement in direct activity with beneficiaries, employment, etc.)

− What changes do you want to make in the future in the management of the institution?

− Tell us, if you can, about your relationship with God. How has faith influenced the realities you have experienced in the past year?

− Would you like to add anything else?

− Your gender is

− Your age in years is

− Last school completed

− Your experience in aged care is of

− Your social work experience is of