Submitted:

09 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. COVID 19 and Beyond

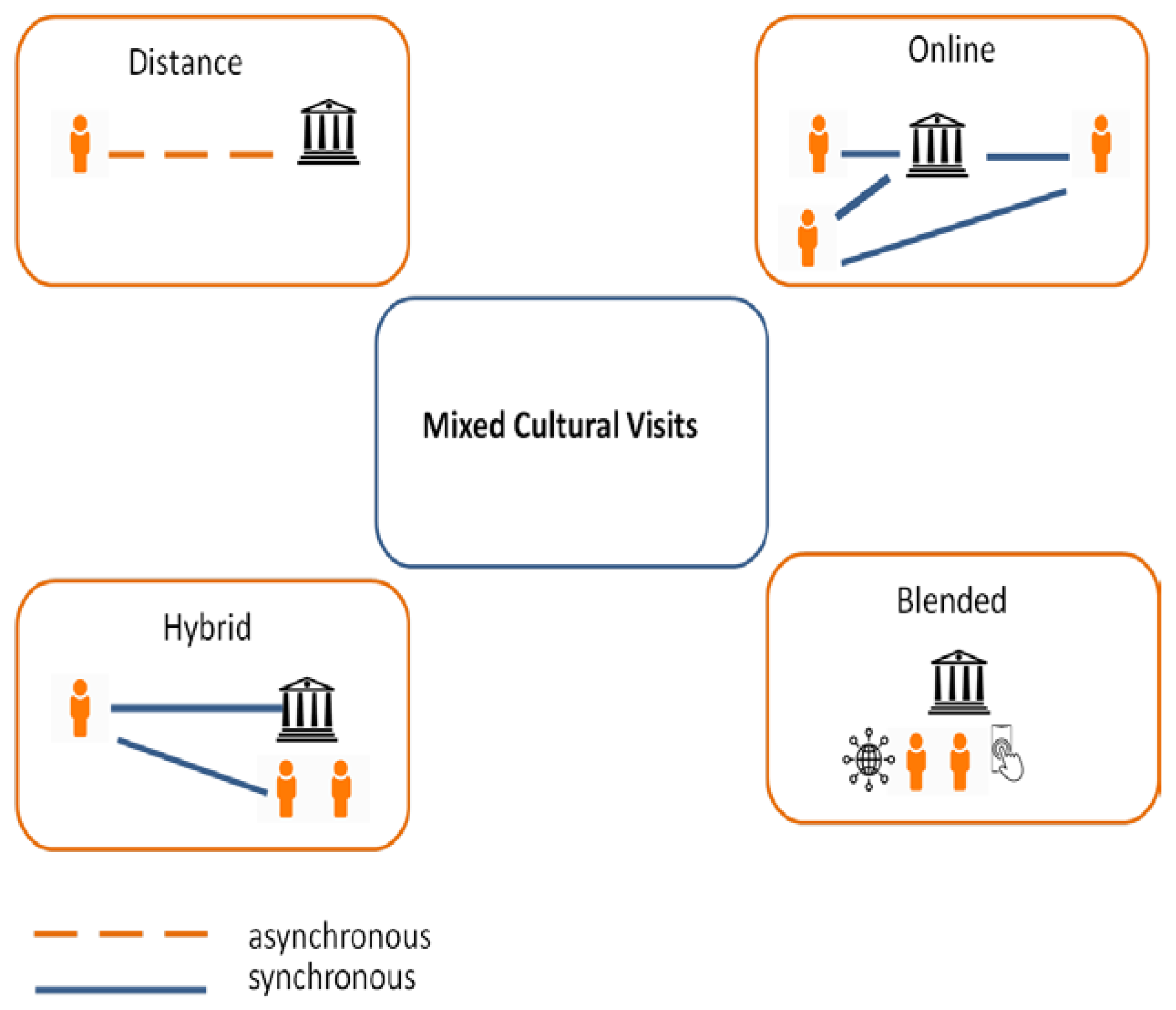

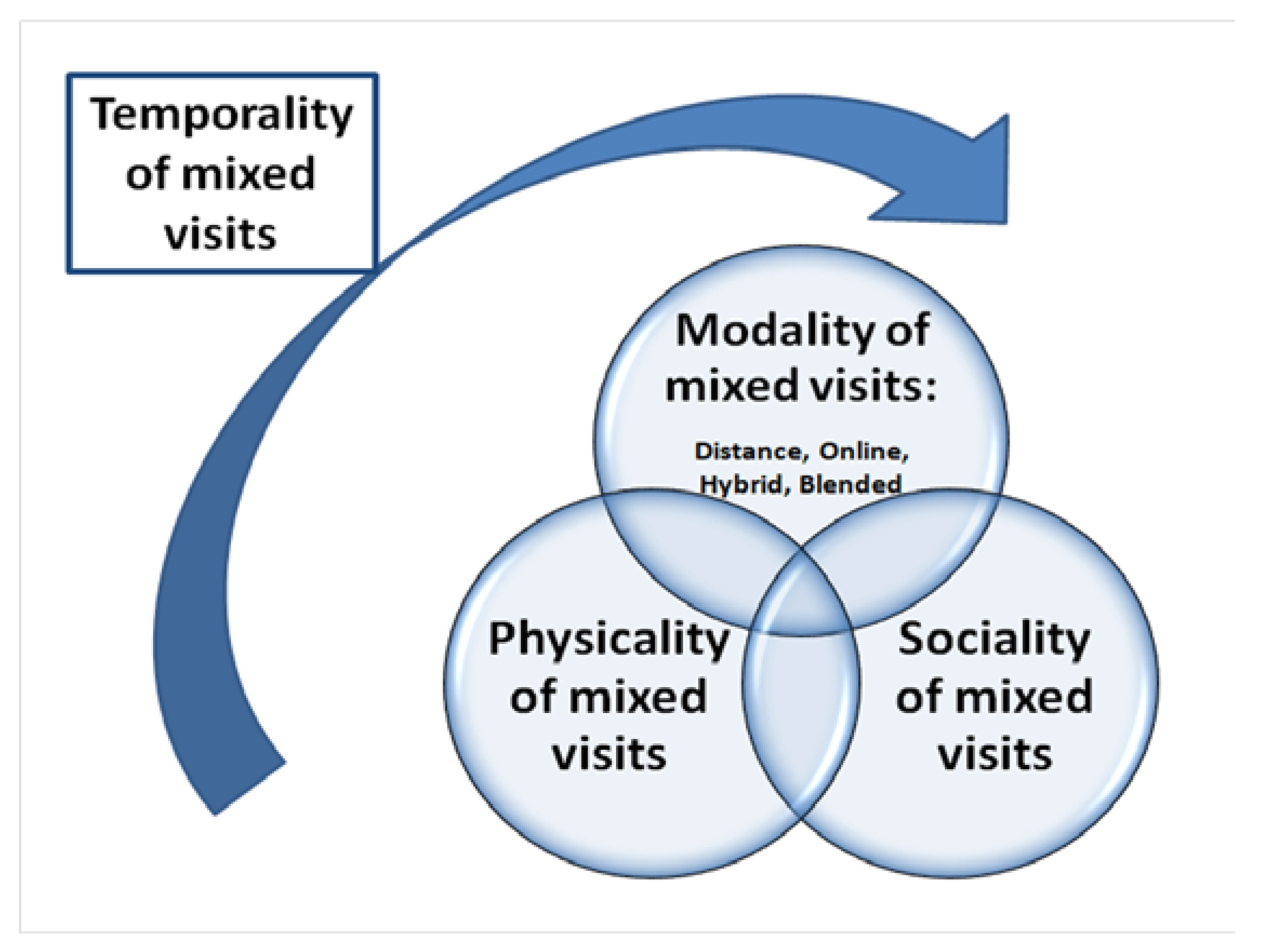

2. Three Years of Rapid Developments (2020-2023)

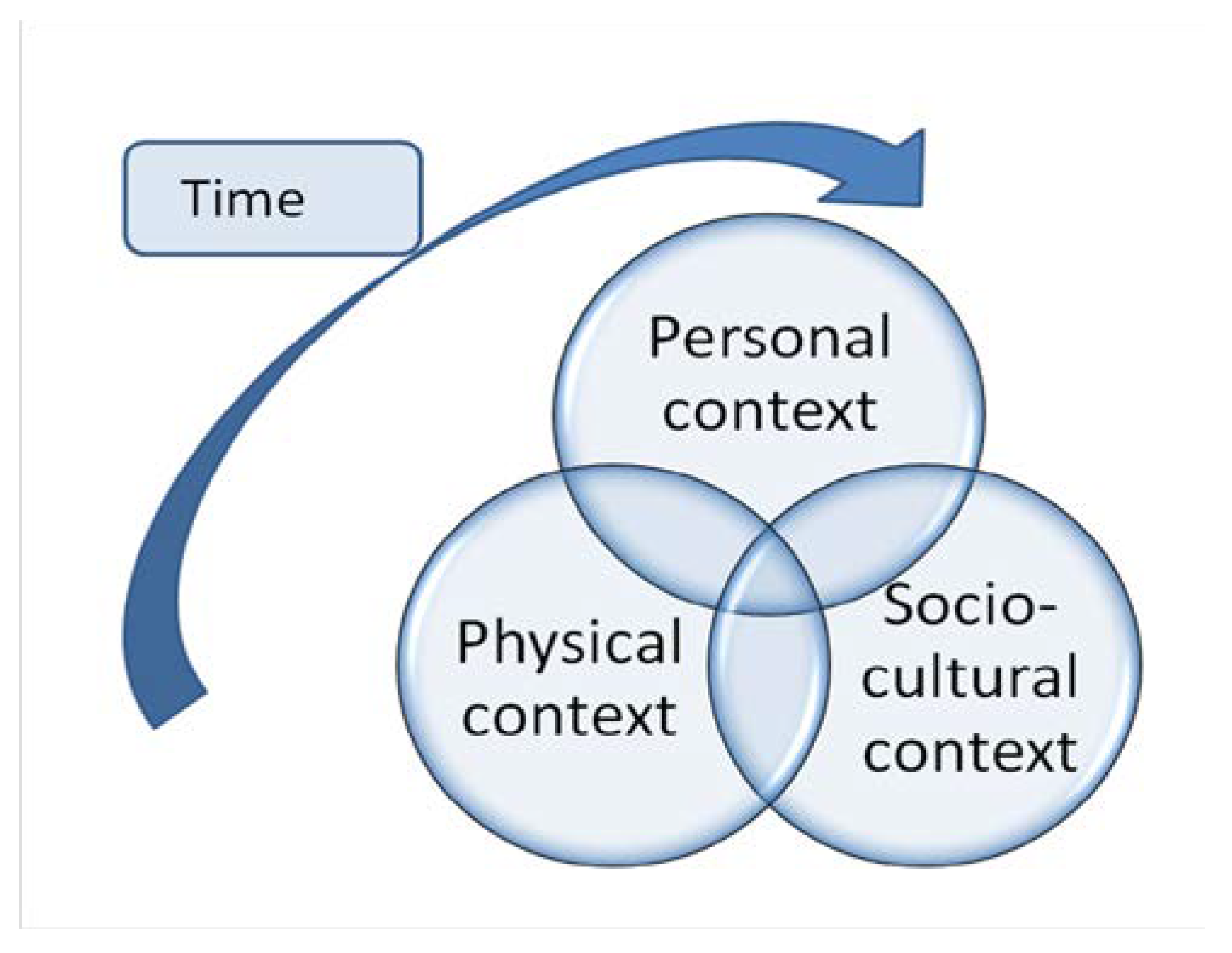

3. Using the Contextual Model for Museum Visits

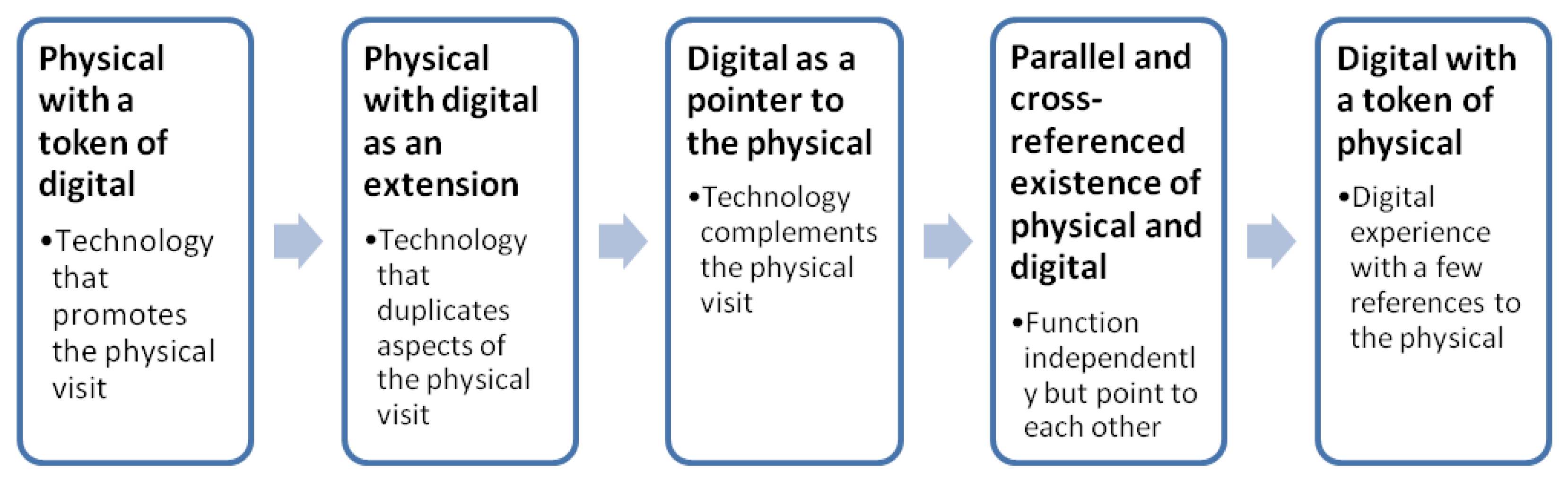

4. Mixed Visits in the Personal Context

- Physical with a token of digital: these are primarily physical spaces that use online tools to promote the physical visit, like websites with visit information, social media campaigns to increase physical visits, etc.

- Physical with digital as an extension: Again these are physical spaces that use technology to duplicate aspects of the visit, like virtual tours. The content of the technology is the same as in the physical environment but only as a subordinate substitute.

- Digital as a pointer to the physical: the physical space is again the central in the cultural experience and although the digital content is different from the physical one, is only complementary to the physical visit.

- Parallel and cross-referenced existence of physical and digital: There are two distinct experiences in the digital and the physical world that function independently, although they both refer to each other.

- Digital with a token of physical: The experience is primarily digital and there are only a few references to the physical world. For example, there are museums and collections that only exist in the digital world and they do not have a physical condition, like the Digital Art Museum (https://dam.org/museum/dam/about/).

5. Mixed Visits in the Socio-Cultural Context

6. Mixed Visits in the Physical Context

7. Mixed Visits over Time

8. Contextual Model of Mixed Visits

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burke, V.; Jørgensen, D.; Jørgensen, F.A. Museums at home: Digital initiatives in response to COVID-19. Nor. Museumstidsskrift 2020, 6, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, L. Museums and Communication: The Case of the Louvre Museum at the Covid-19 Age. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, D.; Arnaboldi, M.; Lampis, A. Italian state museums during the COVID-19 crisis: From onsite closure to online openness. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2020, 35, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J. Museums and social media during COVID-19. Public Hist. 2020, 2020 42, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kist, C. Museums, challenging heritage and social media during COVID-19. Mus. Soc. 2020, 18, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, G. Are we living the future? Museums in the time of Covid19. In Tourism facing a pandemic: From crisis to recovery; Burini, F., Ed.; Universita degli Studi di Bergamo: Italy, 2020; pp. 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ciolfi, L. Hybrid interactions in museums: Why materiality still matters, 2008. Available online: https://www.ubiquitypress.com/site/chapters/10.5334/bck.g/download/4874/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Galani, A.; Kidd, J. Hybrid material encounters–Expanding the continuum of museum materialities in the wake of a pandemic. Mus. Soc. 2020, 18, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waern, A.; Løvlie, A.S. Hybrid Museum Experiences: Theory and Design; Amsterdam University Press, 2022; p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, F. B.; Boyd, J. E.; Levy, R. M.; Eiserman, J. New media and space: An empirical study of learning and enjoyment through museum hybrid space. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2020, 28, 3013–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Løvlie, A.S.; Waern, A.; Eklund, L.; Spence, J.; Rajkowska, P.; Benford, S. 2022. Hybrid Museum Experiences. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/53260 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Løvlie, A.S.; Ryding, K.; Spence, J.; Rajkowska, P.; Waern, A.; Wray, T.; Benford, S.; Preston, W.; ClareThorn, E. Playing games with Tito: Designing hybrid museum experiences for critical play. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021, 14, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, A. Online and hybrid learning. J. Manag. Educ. 2018, 42, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, J.; Bedwell, B.; Benford, S.; Eklund, L.; Sundnes Løvlie, A.; Preston, W.; ... Wray, T. GIFT: Hybrid museum experiences through gifting and play. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Cultural Informatics co-located with the EUROMED International Conference on Digital Heritage, Nicosia, Cyprus, 3 November 2018.

- Passebois Ducros, J.; Euzéby, F. Investigating consumer experience in hybrid museums: A netnographic study. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2021, 24, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiu, D.; Ştefan, L.; Hodea, M. Gestures and re-enactments in a hybrid museum of archaeology: Animating ancient life. In Augmented Reality in Tourism, Museums and Heritage: A New Technology to Inform and Entertain, Geroimenko, V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Shelyubskaya, A.; Sokolova, M. The Influence of Digital Technology on Museums, 2022. Available at SSRN 4313290. Online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4313290#:~:text=With%20many%20new%20ways%20to,and%20transforming%20the%20visiting%20experience.

- Kendall, J. J. Invisible Doors the Hybrid Museum: Early Childhood Virtual & In-Person Learning in Art Museums, Doctoral dissertation, Vanderbilt University, 2021.

- Resta, G.; Dicuonzo, F.; Karacan, E.; Pastore, D. The impact of virtual tours on museum exhibitions after the onset of covid-19 restrictions: Visitor engagement and long-term perspectives. SCIRES-IT-SCIentific RESearch Inf. Technol. 2021, 11, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Miyakita, G.; Homma, Y. A Case Study from Keio Museum Commons, Japan, 2022. Online: https://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/media/pdf/article/magazen/2022/2/art-10.30687-mag-2724-3923-2022-06-002_yfGESmj.pdf.

- Simone, C.; Cerquetti, M.; La Sala, A. Museums in the Infosphere: Reshaping value creation. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2021, 36, 322–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradaran Rahimi, F.; Levy, R. M.; Boyd, J. E. Hybrid space: An emerging opportunity that alternative reality technologies offer to the museums. Space Cult. 2021, 24, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergin, G. Museums in the Digital Age: Hybrid Museum Experience. In Multidisciplinary Perspectives Towards Building a Digitally Competent Society; Bansal, S., huja, V., Chatervedi, V., Jain, V., Eds.; IGI Global, 2022, pp. 51-69.

- Mason, M. The elements of visitor experience in post-digital museum design. Des. Princ. Pract. 2020, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunfio, M.; Campana, S.; Magnelli, A. Experimenting hybrid reality in cultural heritage reconstruction. The Peasant Civilisation Park and the ‘Vicinato a Pozzo’museum of Matera (Italy). Mus. Manag. Curatorship.

- Li, Y.; Ch’ng, E. A framework for sharing cultural heritage objects in hybrid virtual and augmented reality environments. In Visual Heritage: Digital Approaches in Heritage Science, Ch’ng, E., Chapman, H., Gaffney, V., Wilson, A.S. Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 471–492. [Google Scholar]

- Trunfio, M.; Jung, T.; Campana, S. Hybrid Reality and Mixed Reality experiences in Italian Cultural Heritage Museums: Are they so far away? 2021. Available online: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/628641/.

- Jung, T.; Trunfio, M.; Campana, S. Serious Game Reality and Industrial Museum: The ‘Bryant and May Match Factory’Project in the Peoples’ History Museum (UK). In Extended Reality and Metaverse: Immersive Technology in Times of Crisis; Jung, T., tom Dieck, M.C., Correia Loureiro, S.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, K. Challenges and opportunities: Creative approaches to museum and gallery learning during the pandemic. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2021, 40, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J. H.; Dierking, L. D. Learning from museums. Rowman & Littlefield, 2018.

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. 2004. The contextual model of learning. In Reinventing the museum: Historical and contemporary perspectives on the paradigm shift, Anderson, G., Ed.; 2004, pp. 139–142.

- Falk, J.; Storksdieck, M. Using the contextual model of learning to understand visitor learning from a science center exhibition. Sci. Educ. 2005, 89, 744–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, D. Distance learning: Promises, problems, and possibilities. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2002, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Trahanias, P.; Argyros, A.; Tsakiris, D.; Cremers, A.; Schulz, D.; Burgard, W.; Haehnel, D.; Savvaides, V.; Giannoulis, G.; Coliou, M.; Kamarinos, G. Tourbot-interactive museum tele-presence through robotic avatars. In Proceedings of the 9th International World Wide Web Conference, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 15 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C.R. Blended learning systems. In The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs 1; Bonk, C. J., Graham, C. R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, 2012; pp.3-21.

- Antoniou, A.; Reboreda Morillo, S.; Lepouras, G.; Jason Diakoumakos, J.; Vassilakis, C.; Lopez Nores; M. ; Jones, C.E. Bringing a peripheral, traditional venue to the digital era with targeted narratives. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2019, 14, e00111. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, A.; Lepouras, G.; Kastritsis, A.; Diakoumakos, J.; Aggelakos, Y.; Platis, N. "Take me Home": AR to Connect Exhibits to Excavation Sites. Proceedings of AVI²CH@ AVI 2020, Ischia, Italy, 29 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Jung, T.H.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Chung, N. C.; Chung, N. Experiencing immersive virtual reality in museums. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, A.; Dejonai, M. I.; Lepouras, G. (2019). ‘Museum escape’: A game to increase museum visibility. In Proceedings of Games and Learning Alliance: 8th International Conference, GALA 2019, Athens, Greece, 27–29 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilakis, C.; Poulopoulos, V.; Antoniou, A.; Wallace, M.; Lepouras, G.; Lopez Nores, M. "exhiSTORY: Smart Selforganizing Exhibits." In Big Data Platforms and Applications; Pop, F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing, 2021; pp. 91–111.

- Dudar, V.L.; Riznyk, V.V.; Kotsur, V.V.; Pechenizka, S.S.; Kovtun, O.A. Use of modern technologies and digital tools in the context of distance and mixed learning. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2021, 5(S2), 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, E.; Reffat, RM.; Vande Moere, A. Phygital heritage: An approach for heritage communication. In Proceedings of the 3rd Immersive Learning Research Network Conference (iLRN 2017), Coimbra, Portugal, 26 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Debono, S. Thinking Phygital: A Museological Framework of Predictive Futures. Mus. Int. 2021, 73((3-4)), 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayanou, M.; Katifori, A.; Chrysanthi, A.; Antoniou, A. (2020). Cultural Heritage and Social Experiences in the Times of COVID 19. In Proceedings of AVI²CH@ AVI, Ischia, Italy, 29 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Daif, A.; Dahroug, A.T.; López-Nores, M.; González-Soutelo, S.; Bassani, M.; Antoniou, A.; Gil-Solla, A.; Ramos-Cabrer, M.; Pazos-Arias, J.J. A mobile app to learn about cultural and historical associations in a closed loop with humanities experts. Applied Sciences 2018, 9, p.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katifori, A.; Perry, S.; Vayanou, M.; Antoniou, A.; Ioannidis, I.P.; McKinney, S.; Chrysanthi, A.; Ioannidis, Y. “Let them talk!” exploring guided group interaction in digital storytelling experiences. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2020, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, A.; Vayanou, M.; Katifori, A.; Chrysanthi, A.; Cheilitsi, F.; Ioannidis, Y. “Real Change Comes from Within!”: Towards a Symbiosis of Human and Digital Guides in the Museum. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysanthi, A.; Katifori, A.; Vayanou, M.; Antoniou, A. Place-based digital storytelling. the interplay between narrative forms and the cultural heritage space. In Proceedings of the Emerging Technologies and the Digital Transformation of Museums and Heritage Sites: First International Conference, RISE IMET 2021, Nicosia, Cyprus, 2–4 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jokanović, M. Perspectives on Virtual Museum Tours. INSAM Journal of Contemporary Music Art Technol. 2020, 2, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabassi, K.; Maravelakis, E.; Konstantaras, A. Heuristics and Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision Making for Evaluating Museum Virtual Tours. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2018, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, G. Mediating distance: New interfaces and interaction design techniques to follow and take part in remote museum visits. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2020, 22, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carolis, B. N.; Lops, P.; Musto, C.; Semeraro, G. Towards a Social Robot as Interface for Tourism Recommendations. Proceedings of cAESAR, Cagliari, Italy, 17–20 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kontiza, K.; Antoniou, A.; Daif, A.; Reboreda-Morillo, S.; Bassani, M.; González-Soutelo, S.; Lykourentzou, I.; Jones, C.E.; Padfield, J.; López-Nores, M. On How Technology-Powered Storytelling Can Contribute to Cultural Heritage Sustainability across Multiple Venues—Evidence from the CrossCult H2020 Project. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliacani, M.; Sorrentino, D. Reinterpreting museums’ intended experience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from Italian University Museums. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E. People, Museums and the Rhetoric of Temporality: Considerations Regarding the Formation of the Collection at The Museum of Anthropology of Vancouver. Arch. Antropol. Mediterr. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentazou, I.; Laliotou, I. Perceptions of temporality in city museums: Timeline as visualization structure. Alifragkis, S., Papakonstantinou, G., Papasarantou, Volos, Greece, 3-4 July 2015., C.Eds 2015. In Proceedings of the Symposium Museums in Motion. [Google Scholar]

- Barndt, K. Layers of time: Industrial ruins and exhibitionary temporalities. PMLA 2010, 125, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon, J.P. Museums, plasticity, temporality. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2006, 21, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölling, H.B. Keeping Time: On Museum, Temporality and Heterotopia. ArtMatters: Int. J. Tech. Art Hist. 2021, 1, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Walklate, J.A. Time and the Museum: Literature, Phenomenology, and the Production of Radical Temporality. Taylor & Francis: 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).