Submitted:

11 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

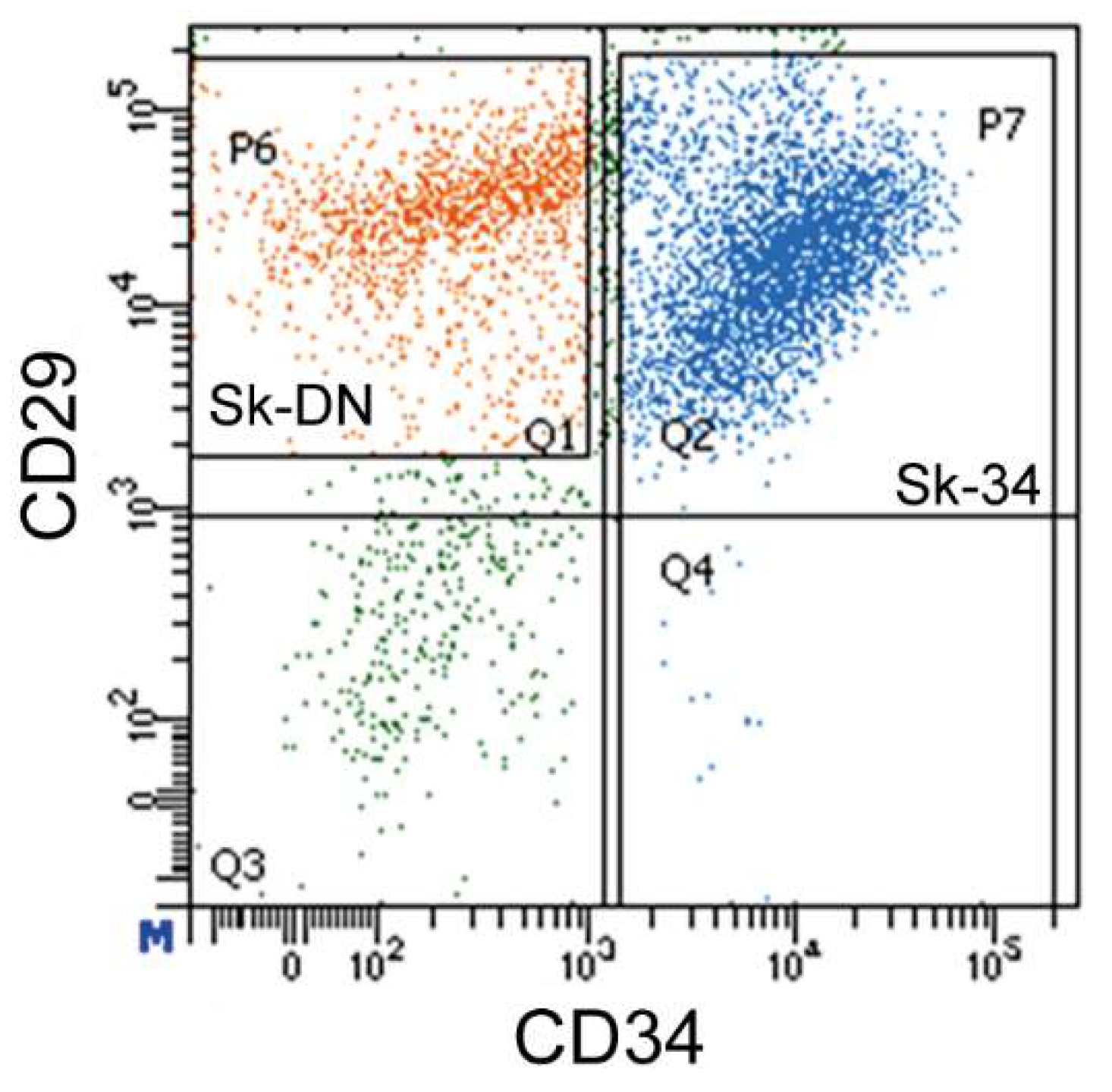

2.1. Fractionation of Sk-34 and Sk-DN cells

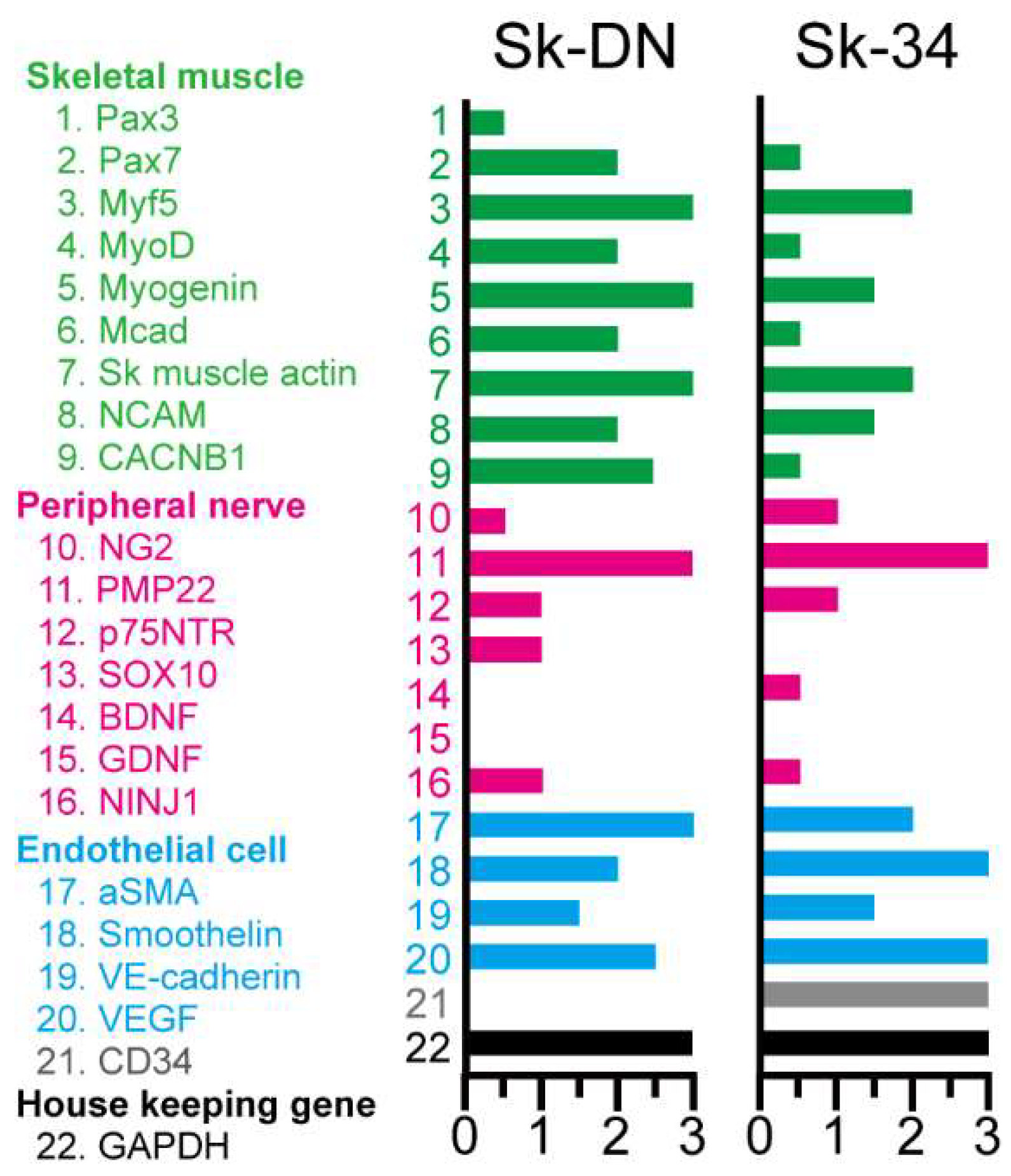

2.2. Expression of skeletal muscle, peripheral nerve, and vascular cell lineage specific mRNAs immediately after sorting

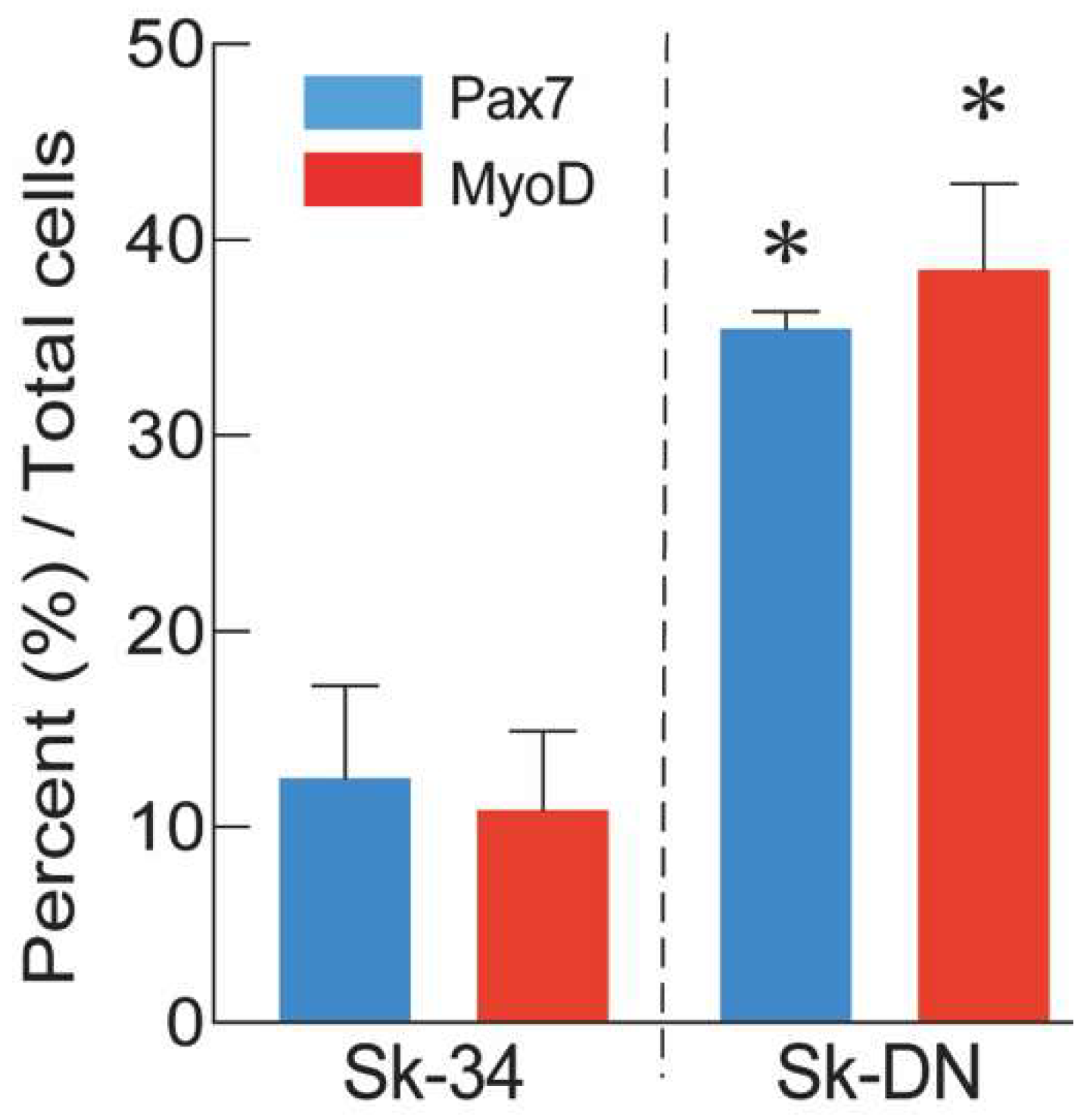

2.3. Distributions of Pax7 and MyoD positive cells after culture

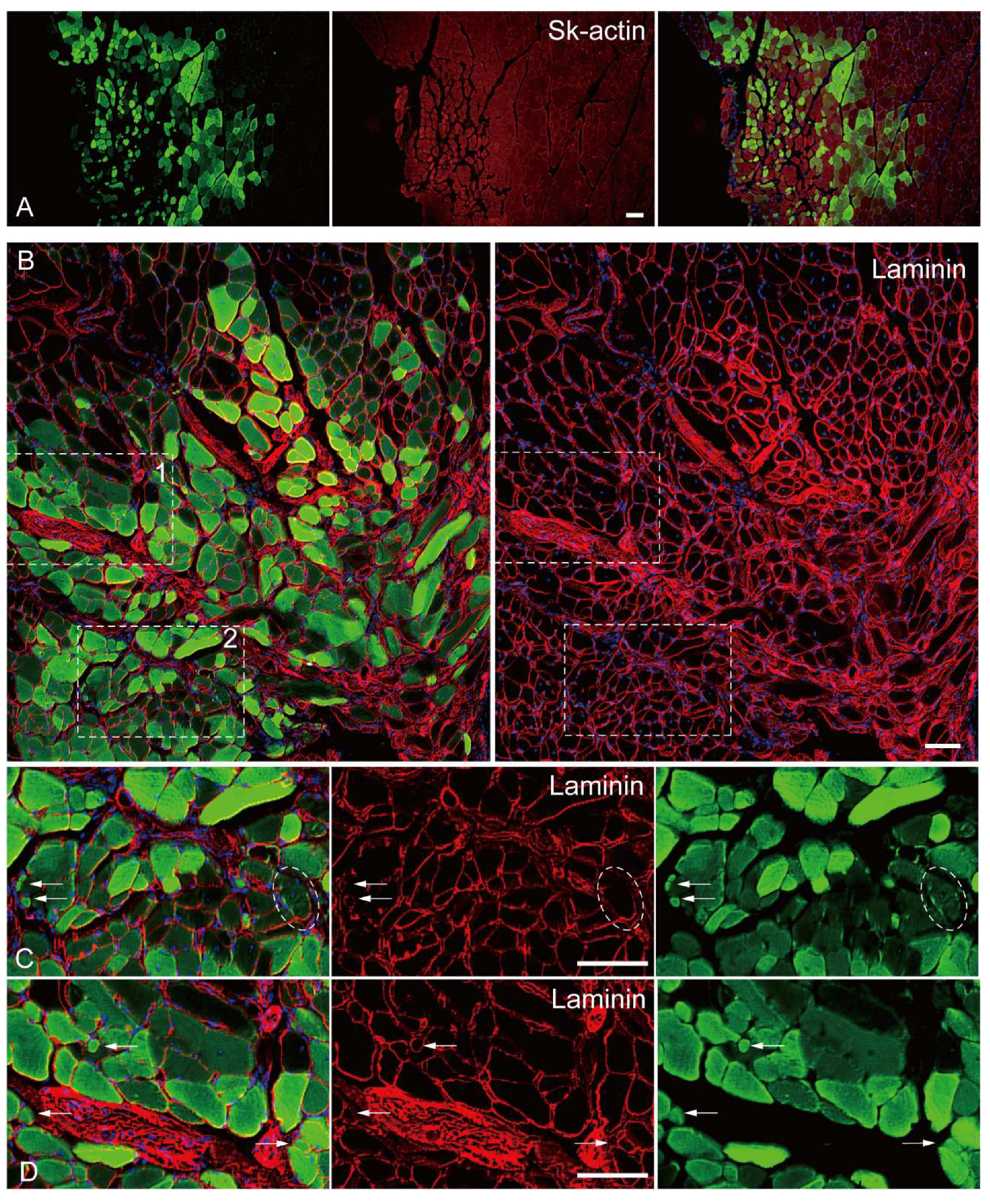

2.4. In vivo differentiation capacity of Sk-DN cells

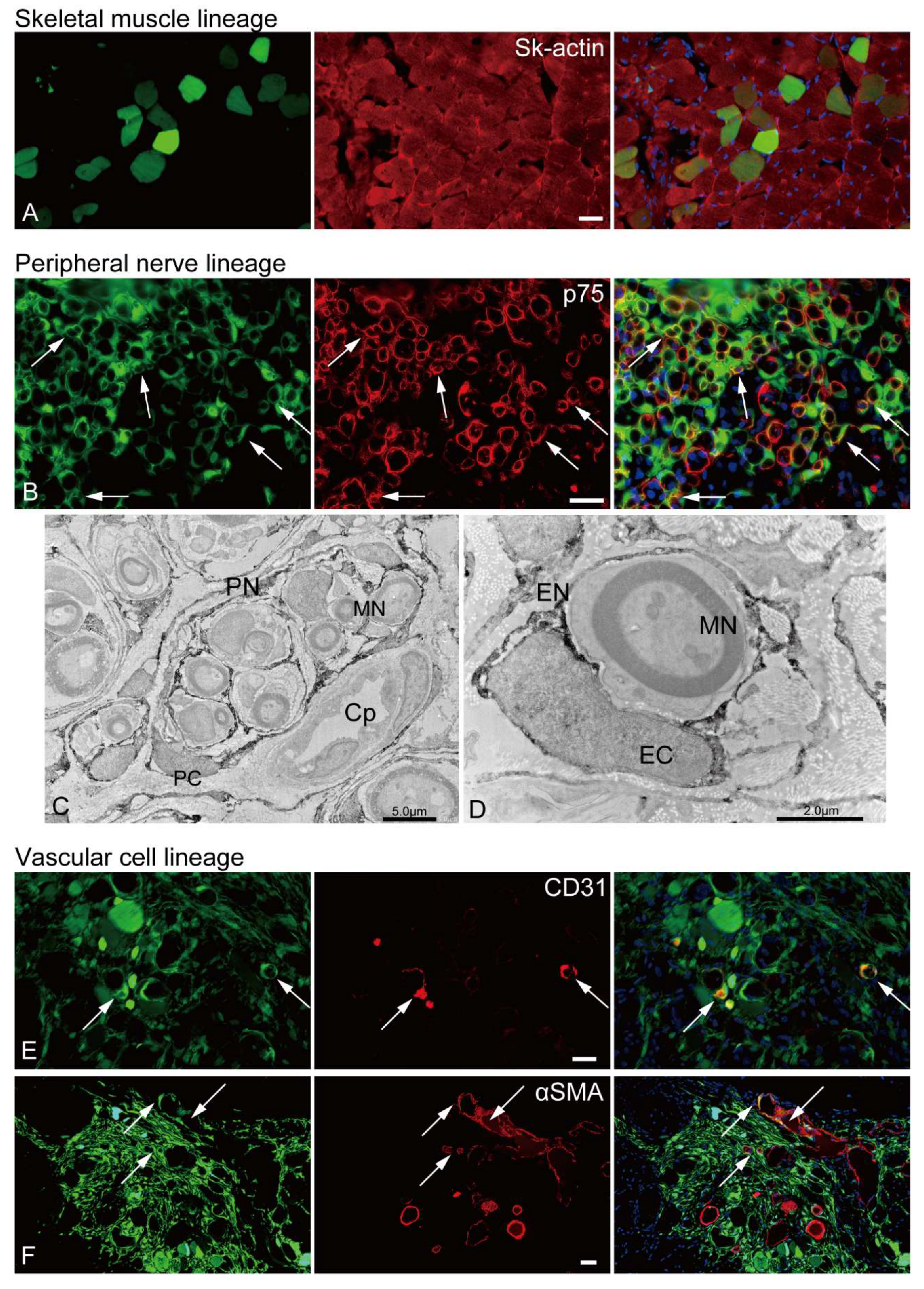

2.5. In vivo differentiation capacity of Sk-34 cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal usage

4.2. Cell isolation and sorting

4.3. Cell sorting

4.4. RT-PCR

4.5. In vitro myogenic differentiation capacity of pig Sk-34 and Sk-DN cells

4.6. In vivo cell differentiation capacity and recipient animals

4.7. Immunohistochemistry and immunoelectron microscopy

4.8. Statistics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Okabe, M., M. Ikawa, K. Kominami, T. Nakanishi and Y. Nishimune. "'Green mice' as a source of ubiquitous green cells." FEBS Lett 407 (1997): 313-9. S0014-5793(97)00313-X [pii]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9175875.

- Ijiri, M., Y. C. Lai, H. Kawaguchi, Y. Fujimoto, N. Miura, T. Matsuo and A. Tanimoto. "Nr6a1 allelic frequencies as an index for both miniaturizing and increasing pig body size." In Vivo 35 (2021): 163-67. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33402462. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, N., K. Itoh, A. Sugiyama and Y. Izumi. "Microminipig, a non-rodent experimental animal optimized for life science research: Preface." J Pharmacol Sci 115 (2011): 112-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32272527. [CrossRef]

- https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jphs/115/2/115_10R16FM/_pdf.

- Kawaguchi, H., N. Miyoshi, N. Miura, M. Fujiki, M. Horiuchi, Y. Izumi, H. Miyajima, R. Nagata, K. Misumi, T. Takeuchi, et al. "Microminipig, a non-rodent experimental animal optimized for life science research: Novel atherosclerosis model induced by high fat and cholesterol diet." J Pharmacol Sci 115 (2011): 115-21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32272528. [CrossRef]

- https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jphs/115/2/115_10R17FM/_pdf.

- Sugiyama, A., Y. Nakamura, Y. Akie, H. Saito, Y. Izumi, H. Yamazaki, N. Kaneko and K. Itoh. "Microminipig, a non-rodent experimental animal optimized for life science research: In vivo proarrhythmia models of drug-induced long qt syndrome: Development of chronic atrioventricular block model of microminipig." J Pharmacol Sci 115 (2011): 122-26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32272529. [CrossRef]

- https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jphs/115/2/115_10R21FM/_pdf.

- Kawarasaki, T., K. Uchiyama, A. Hirao, S. Azuma, M. Otake, M. Shibata, S. Tsuchiya, S. Enosawa, K. Takeuchi, K. Konno, et al. "Profile of new green fluorescent protein transgenic jinhua pigs as an imaging source." J Biomed Opt 14 (2009): 054017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19895119. [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M. E., S.; Yukiko Otsu, Y.; Kawarasaki, T. "Development of gfp-transgenic mini-pig by backcrossing." Bulletin of Shizuoka prifectural research institiute of animal indaustry swine & poultry research center 6 (2013): 7-10.

- Tamaki, T., A. Akatsuka, K. Ando, Y. Nakamura, H. Matsuzawa, T. Hotta, R. R. Roy and V. R. Edgerton. "Identification of myogenic-endothelial progenitor cells in the interstitial spaces of skeletal muscle." J Cell Biol 157 (2002): 571-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11994315.

- Tamaki, T., A. Akatsuka, Y. Okada, Y. Matsuzaki, H. Okano and M. Kimura. "Growth and differentiation potential of main- and side-population cells derived from murine skeletal muscle." Exp Cell Res 291 (2003): 83-90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=14597410.

- Tamaki, T., Y. Uchiyama, Y. Okada, T. Ishikawa, M. Sato, A. Akatsuka and T. Asahara. "Functional recovery of damaged skeletal muscle through synchronized vasculogenesis, myogenesis, and neurogenesis by muscle-derived stem cells." Circulation 112 (2005): 2857-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16246946.

- Tamaki, T., Y. Okada, Y. Uchiyama, K. Tono, M. Masuda, M. Wada, A. Hoshi and A. Akatsuka. "Synchronized reconstitution of muscle fibers, peripheral nerves and blood vessels by murine skeletal muscle-derived cd34(-)/45 (-) cells." Histochem Cell Biol 128 (2007): 349-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17762938. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, T., Y. Okada, Y. Uchiyama, K. Tono, M. Masuda, M. Wada, A. Hoshi, T. Ishikawa and A. Akatsuka. "Clonal multipotency of skeletal muscle-derived stem cells between mesodermal and ectodermal lineage." Stem Cells 25 (2007): 2283-90. 2006-0746 [pii].

- 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0746. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17588936.

- Tamaki, T., Y. Okada, Y. Uchiyama, K. Tono, M. Masuda, M. Nitta, A. Hoshi and A. Akatsuka. "Skeletal muscle-derived cd34+/45- and cd34-/45- stem cells are situated hierarchically upstream of pax7+ cells." Stem Cells Dev 17 (2008): 653-67. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18554087. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, T., Y. Uchiyama, M. Hirata, H. Hashimoto, N. Nakajima, K. Saito, T. Terachi and J. Mochida. "Therapeutic isolation and expansion of human skeletal muscle-derived stem cells for the use of muscle-nerve-blood vessel reconstitution." Front Physiol 6 (2015): 165. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26082721. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, T., A. Akatsuka, Y. Okada, Y. Uchiyama, K. Tono, M. Wada, A. Hoshi, H. Iwaguro, H. Iwasaki, A. Oyamada, et al. "Cardiomyocyte formation by skeletal muscle-derived multi-myogenic stem cells after transplantation into infarcted myocardium." PLoS One 3 (2008): e1789. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18335059. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, T., Y. Uchiyama, Y. Okada, K. Tono, M. Masuda, M. Nitta, A. Hoshi and A. Akatsuka. "Clonal differentiation of skeletal muscle-derived cd34(-)/45(-) stem cells into cardiomyocytes in vivo." Stem Cells Dev 19 (2010): 503-12. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19634996. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, T., M. Hirata, S. Soeda, N. Nakajima, K. Saito, K. Nakazato, Y. Okada, H. Hashimoto, Y. Uchiyama and J. Mochida. "Preferential and comprehensive reconstitution of severely damaged sciatic nerve using murine skeletal muscle-derived multipotent stem cells." PLoS One 9 (2014): e91257. [CrossRef]

- PONE-D-13-38421 [pii]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=24614849.

- Tamaki, T., M. Hirata, N. Nakajima, K. Saito, H. Hashimoto, S. Soeda, Y. Uchiyama and M. Watanabe. "A long-gap peripheral nerve injury therapy using human skeletal muscle-derived stem cells (sk-scs): An achievement of significant morphological, numerical and functional recovery." PLoS One 11 (2016): e0166639. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27846318. [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, T. "Therapeutic capacities of human and mouse skeletal muscle-derived stem cells for a long gap peripheral nerve injury." Neural Regen Res 12 (2017): 1811-13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29239325. [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G., S. Pagano, A. Bez, A. Benetti, S. Pozzi, G. Iannolo, M. Baronio, G. Invernici, A. Caruso, C. Muneretto, et al. "Isolation and culture of human muscle-derived stem cells able to differentiate into myogenic and neurogenic cell lineages." Lancet 364 (2004): 1872-83. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15555667.

- Arriero, M., S. V. Brodsky, O. Gealekman, P. A. Lucas and M. S. Goligorsky. "Adult skeletal muscle stem cells differentiate into endothelial lineage and ameliorate renal dysfunction after acute ischemia." Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287 (2004): F621-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15198930. [CrossRef]

- https://journals.physiology.org/doi/pdf/10.1152/ajprenal.00126.2004.

- Hoshi, A., T. Tamaki, K. Tono, Y. Okada, A. Akatsuka, Y. Usui and T. Terachi. "Reconstruction of radical prostatectomy-induced urethral damage using skeletal muscle-derived multipotent stem cells." Transplantation 85 (2008): 1617-24. [CrossRef]

- 00007890-200806150-00023 [pii]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18551069.

- Kazuno, A., D. Maki, I. Yamato, N. Nakajima, H. Seta, S. Soeda, S. Ozawa, Y. Uchiyama and T. Tamaki. "Regeneration of transected recurrent laryngeal nerve using hybrid-transplantation of skeletal muscle-derived stem cells and bioabsorbable scaffold." J Clin Med 7 (2018): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30213120. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, N., T. Tamaki, M. Hirata, S. Soeda, M. Nitta, A. Hoshi and T. Terachi. "Purified human skeletal muscle-derived stem cells enhance the repair and regeneration in the damaged urethra." Transplantation 101 (2017): 2312-20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28027190. [CrossRef]

- Qu-Petersen, Z., B. Deasy, R. Jankowski, M. Ikezawa, J. Cummins, R. Pruchnic, J. Mytinger, B. Cao, C. Gates, A. Wernig, et al. "Identification of a novel population of muscle stem cells in mice: Potential for muscle regeneration." J Cell Biol 157 (2002): 851-64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12021255. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B., C. W. Chen, G. Li, S. D. Thompson, M. Poddar, B. Peault and J. Huard. "Isolation of myogenic stem cells from cultures of cryopreserved human skeletal muscle." Cell Transplant 21 (2012): 1087-93. ct0204zheng [pii] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=22472558. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., H. Cui, H. Lu, Z. Xu, W. Feng, L. Chen, X. Jin, X. Yang and Z. Qi. "Muscle-derived stem cells in peripheral nerve regeneration: Reality or illusion?" Regen Med 12 (2017): 459-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28621200. [CrossRef]

- Sarig, R., Z. Baruchi, O. Fuchs, U. Nudel and D. Yaffe. "Regeneration and transdifferentiation potential of muscle-derived stem cells propagated as myospheres." Stem Cells 24 (2006): 1769-78. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16574751.https://stemcellsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1634/stemcells.2005-0547?download=true.

- Mitutsova, V., W. W. Y. Yeo, R. Davaze, C. Franckhauser, E. H. Hani, S. Abdullah, P. Mollard, M. Schaeffer, A. Fernandez and N. J. C. Lamb. "Adult muscle-derived stem cells engraft and differentiate into insulin-expressing cells in pancreatic islets of diabetic mice." Stem Cell Res Ther 8 (2017): 86. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28420418. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., Z. Qu-Petersen, B. Cao, S. Kimura, R. Jankowski, J. Cummins, A. Usas, C. Gates, P. Robbins, A. Wernig, et al. "Clonal isolation of muscle-derived cells capable of enhancing muscle regeneration and bone healing." J Cell Biol 150 (2000): 1085-100. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/Entrez/referer?http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/abstract/150/5/1085.

- http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/150/5/1085.

- http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/abstract/150/5/1085.

- Ikezawa, M., B. Cao, Z. Qu, H. Peng, X. Xiao, R. Pruchnic, S. Kimura, T. Miike and J. Huard. "Dystrophin delivery in dystrophin-deficient dmdmdx skeletal muscle by isogenic muscle-derived stem cell transplantation." Hum Gene Ther 14 (2003): 1535-46. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=14577915.

- Tamaki, T., Y. Uchiyama and A. Akatsuka. "Plasticity and physiological role of stem cells derived from skeletal muscle interstitium: Contribution to muscle fiber hyperplasia and therapeutic use." Curr Pharm Des 16 (2010): 956-67. BSP/CPD/E-Pub/00021 [pii]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20041822.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).