Submitted:

11 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

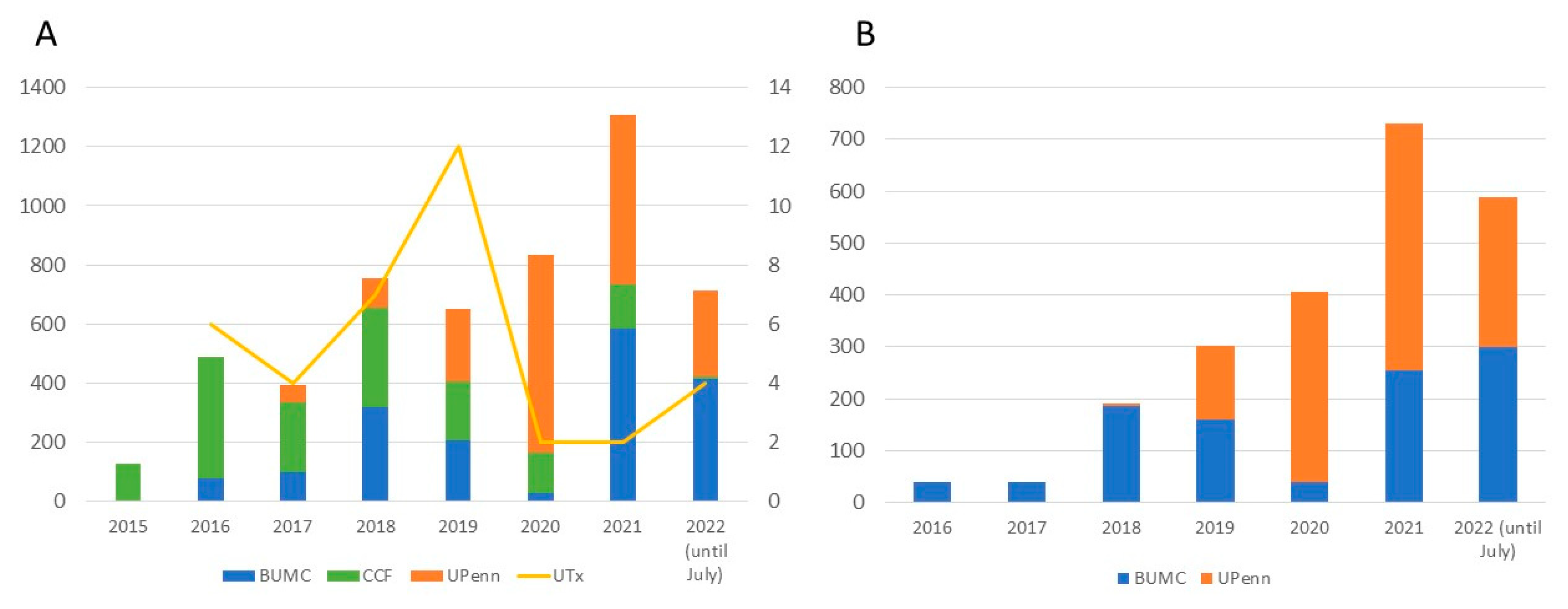

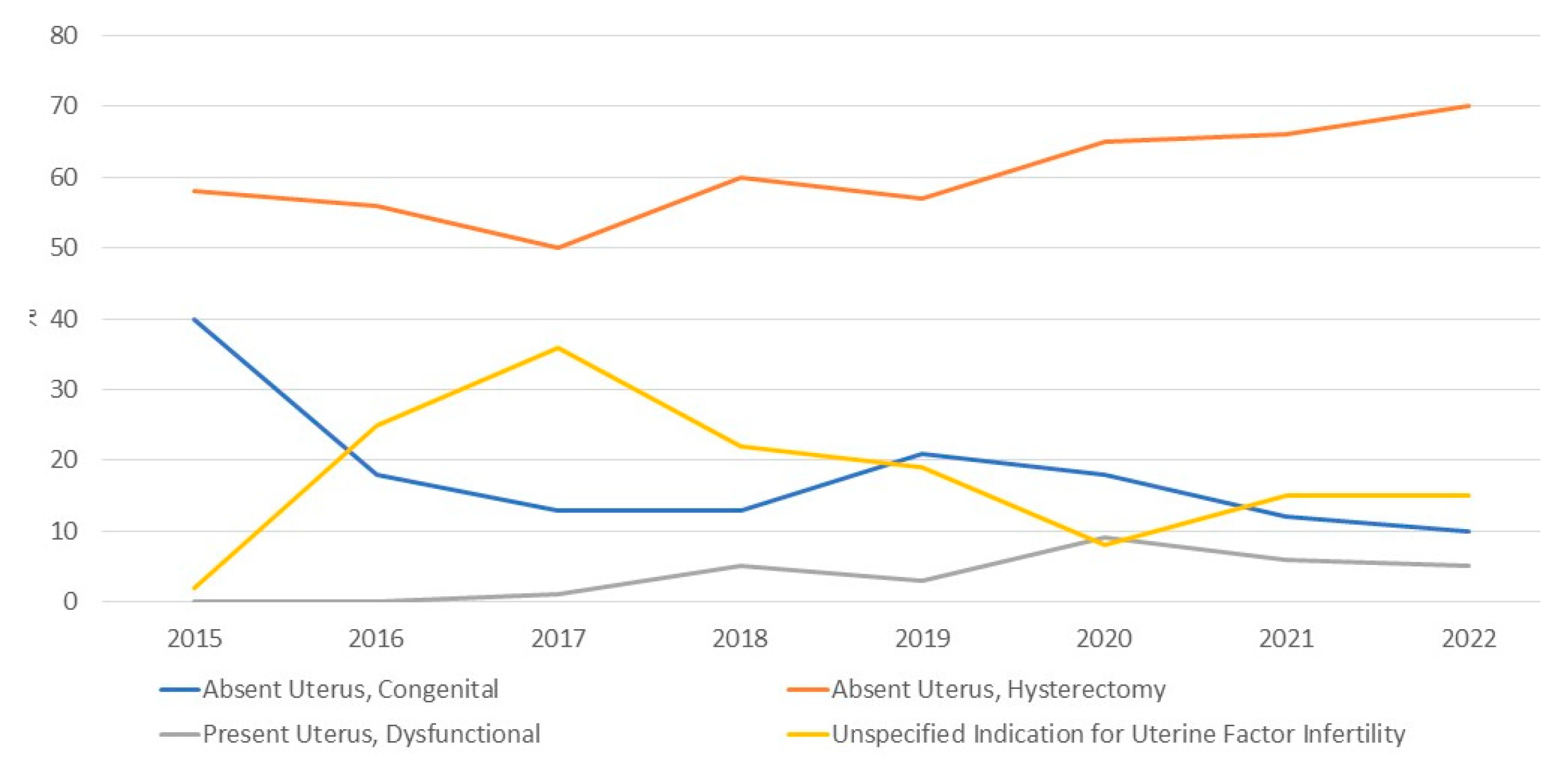

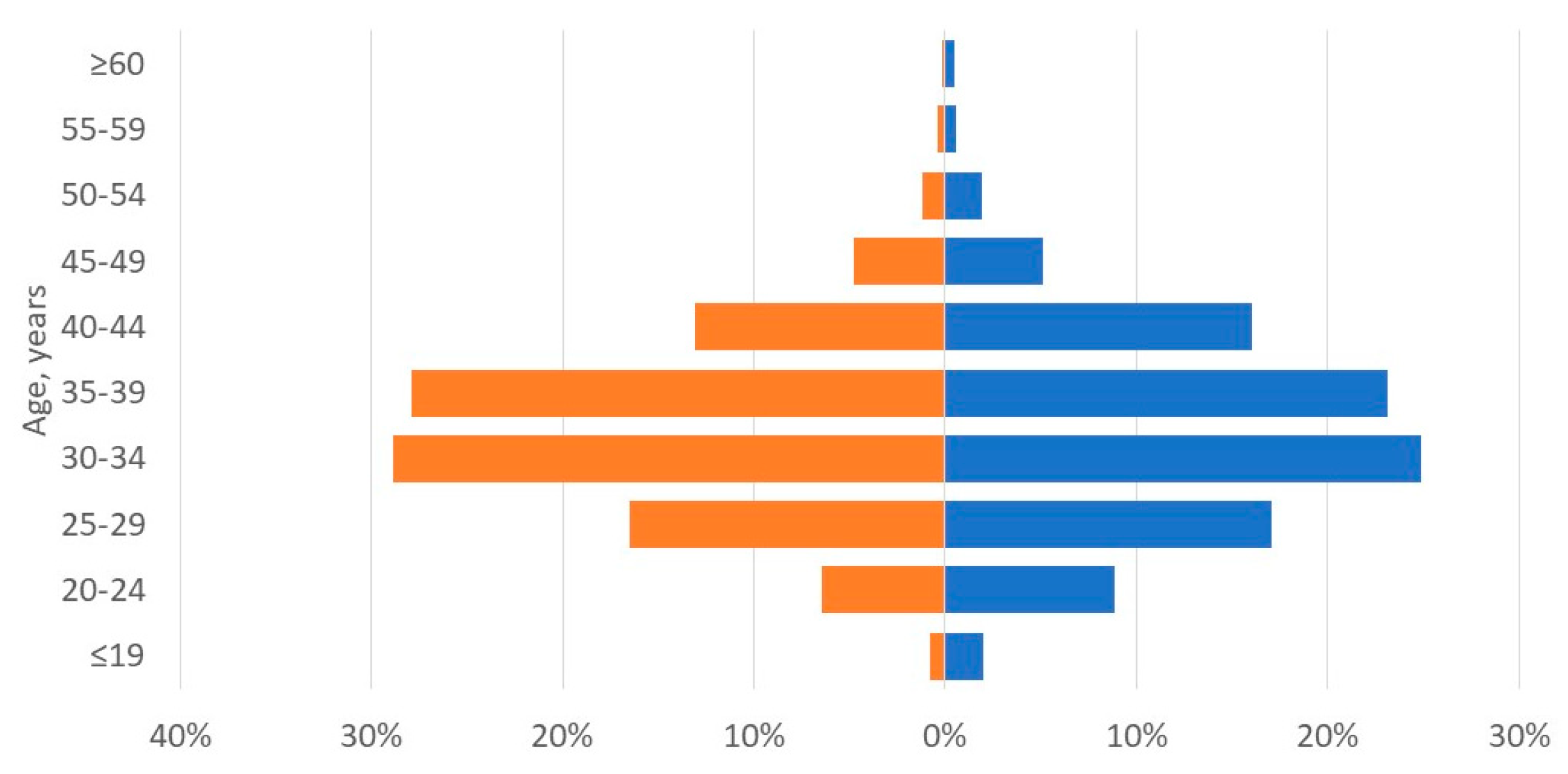

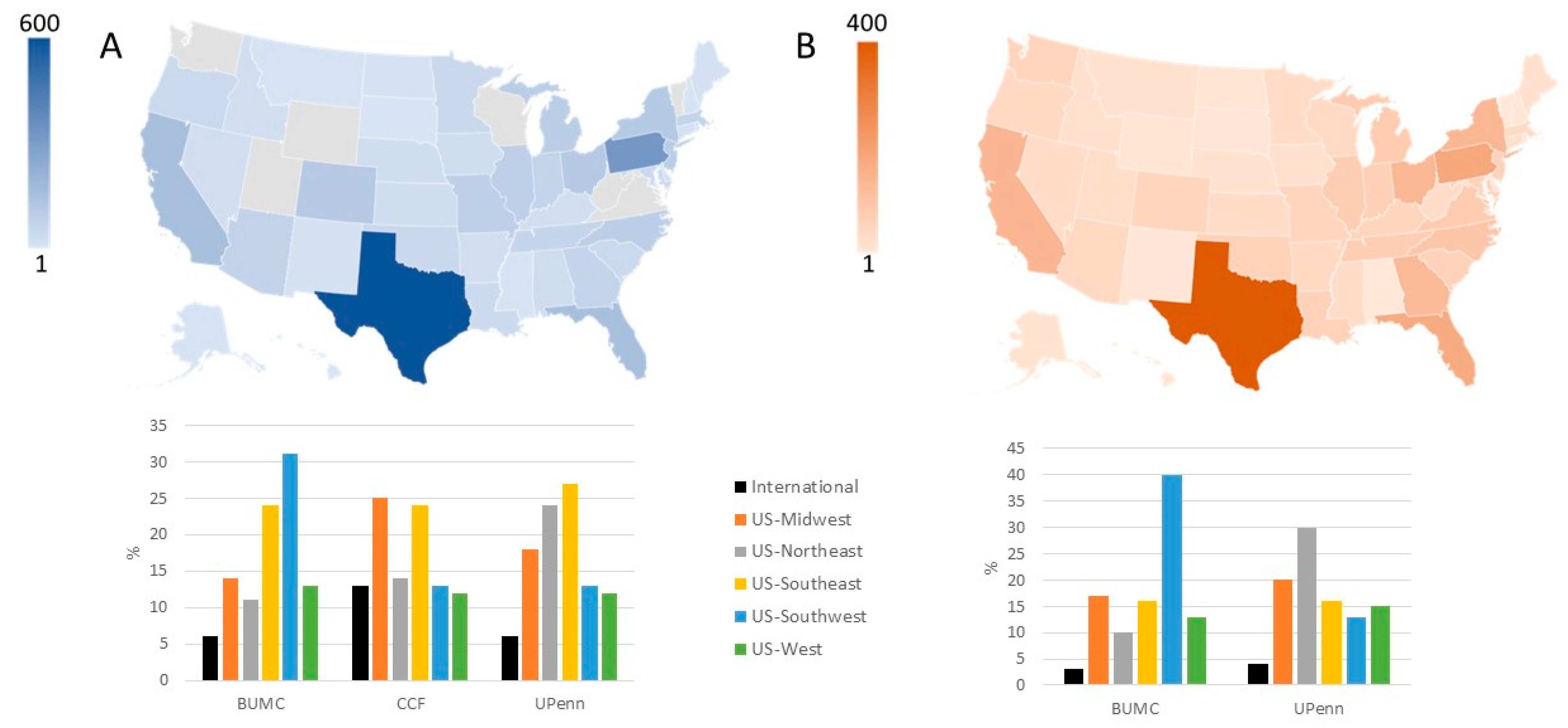

3.1. Applicant Characteristics: Potential Recipients

3.2. Applicant Characteristics: Potential Donors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johannesson, L.; Richards, E.; Reddy, V.; Walter, J.; Olthoff, K.; Quintini, C.; Tzakis, A.; Latif, N.; Porrett, P.; O'Neill, K.; et al. The First 5 Years of Uterus Transplant in the US—A Report From the United States Uterus Transplant Consortium. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, G.; McKenna, G.J.; Gunby, R.T., Jr.; Anthony, T.; Koon, E.C.; Warren, A.M.; Putman, J.M.; Zhang, L.; DePrisco, G.; Mitchell, J.M.; et al. First live birth after uterus transplantation in the United States. Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 1270–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brännström, M.; Tullius, S.G.; Brucker, S.; Dahm-Kähler, P.; Flyckt, R.; Kisu, I.; Andraus, W.; Wei, L.; Carmona, F.; Ayoubi, J.-M.; et al. Registry of the International Society of Uterus Transplantation: First Report. Transplantation 2023, 107, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arian, S.E.; Flyckt, R.L.; Farrell, R.M.; Falcone, T.; Tzakis, A.G. Characterizing women with interest in uterine transplant clinical trials in the United States: who seeks information on this experimental treatment? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonnel, M.; Revaux, A.; Menzhulina, E.; Karpel, L.; Snanoudj, R.; Le Guen, M.; De Ziegler, D.; Ayoubi, J.M. Uterus Transplantation with Live Donors: Screening Candidates in One French Center. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huet, S.; Tardieu, A.; Filloux, M.; Essig, M.; Pichon, N.; Therme, J.F.; Piver, P.; Aubard, Y.; Ayoubi, J.M.; Garbin, O.; et al. Uterus transplantation in France: for which patients? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 205, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannesson, L.; Wallis, K.; Koon, E.C.; McKenna, G.J.; Anthony, T.; Leffingwell, S.G.; Klintmalm, G.B.; Gunby, R.T., Jr.; Testa, G. Living uterus donation and transplantation: experience of interest and screening in a single center in the United States. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 331.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taran, F.-A.; Schöller, D.; Rall, K.; Nadalin, S.; Königsrainer, A.; Henes, M.; Bösmüller, H.; Fend, F.; Nikolaou, K.; Notohamiprodjo, M.; et al. Screening and evaluation of potential recipients and donors for living donor uterus transplantation: results from a single-center observational study. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 111, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesson, L.; Testa, G.; da Graca, B.; Wall, A. How Surgical Research Gave Birth to a New Clinical Surgical Field: A Viewpoint from the Dallas Uterus Transplant Study. Eur. Surg. Res. 2023, 64, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, A.M.; McMinn, K.; Testa, G.; Wall, A.; Saracino, G.; Johannesson, L. Motivations and Psychological Characteristics of Nondirected Uterus Donors From The Dallas UtErus Transplant Study. Prog. Transplant. 2021, 31, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, L.; Santin, G.; Nyangoh Timoh, K.; Boudjema, K.; Jacquot Thierry, L.; Gauthier, T.; Carbonnel, M.; Ayoubi, J.M.; Kerbaul, F.; Lavoue, V. Procurement of uterus in a deceased donor multi-organ donation national program in France: a scarce resource for uterus transplantation? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristek, J.; Johannesson, L.; Testa, G.; Chmel, R.; Olausson, M.; Kvarnström, N.; Karydis, N.; Fronek, J. Limited Availability of Deceased Uterus Donors: A Transatlantic Perspective. Transplantation 2019, 103, 2449–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifferlin, A. First U.S. baby born after a uterus transplant. Time. Available online: https://time.com/5044565/exclusive-first-u-s-baby-born-after-a-uterus-transplant/ (accessed on 1 December 2017).

- Park, M. Baby is first to be born in US after uterus transplant, hospital says. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2017/12/04/health/uterus-transplant-us-baby-birth/index.html (accessed on 4 December 2017).

- Brännström, M.; Johannesson, L.; Dahm-Kähler, P.; Enskog, A.; Mölne, J.; Kvarnström, N.; Diaz-Garcia, C.; Hanafy, A.; Lundmark, C.; Marcickiewicz, J.; et al. First clinical uterus transplantation trial: a six-month report. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, E.H.; Falcone, T.; Flyckt, R.L.; Tzakis, A.G.; Kodish, E.; Richards, E.G. Uterus Transplantation: Revisiting the Question of Deceased Donors versus Living Donors for Organ Procurement. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, B.; Arora, K.S. Uterus Transplantation: The Ethics of Using Deceased Versus Living Donors. Am. J. Bioeth. 2018, 18, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, A.; Edwards, M.; Balayla, J. Ethical considerations in the era of the uterine transplant: an update of the Montreal Criteria for the Ethical Feasibility of Uterine Transplantation. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, A.; Testa, G. Living Donation, Listing, and Prioritization in Uterus Transplantation. Am. J. Bioeth. 2018, 18, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayefsky, M.J.; Berkman, B.E. The Ethics of Allocating Uterine Transplants. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 2016, 25, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A. Allocating Uterus Transplants—Who Gets to Be a Gestational Mother? Am. J. Bioeth. 2018, 18, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefkowitz, A.; Edwards, M.; Balayla, J. The Montreal Criteria for the Ethical Feasibility of Uterine Transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2012, 25, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvholm, S.; Enskog, A.; Hammarling, C.; Dahm-Kähler, P.; Brännström, M. Uterus transplantation: joys and frustrations of becoming a ‘complete’ woman—a qualitative study regarding self-image in the 5-year period after transplantation. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 35, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, A.E.; Johannesson, L.; Sok, M.; Warren, A.M.; Gordon, E.J.; Testa, G. The journey from infertility to uterus transplantation: A qualitative study of the perspectives of participants in the Dallas Uterus Transplant Study. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 129, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggan, K.A.; Khan, Z.; Langstraat, C.L.; Allyse, M.A. Provider Knowledge and Support of Uterus Transplantation: Surveying Multidisciplinary Team Members. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 4, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortoletto, P.; Hariton, E.; Farland, L.V.; Goldman, R.H.; Gargiulo, A.R. Uterine Transplantation: A Survey of Perceptions and Attitudes of American Reproductive Endocrinologists and Gynecologic Surgeons. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2018, 25, 974–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylor Scott & White Health. Uterus Transplant Donor Eligibility. Available online: https://www.bswhealth.com/treatments-and-procedures/uterus-transplant (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- PennMedicine. Frequently Asked Questions and Answers about Uterus Transplant. Available online: https://www.pennmedicine.org/for-patients-and-visitors/find-a-program-or-service/transplant-institute/uterus-transplant/faqs-about-uterus-transplant#can-women-donate-their-uterus (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- McCarthy, C.R. Historical background of clinical trials involving women and minorities. Acad. Med. 1994, 69, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.T.; Watkins, L.; Piña, I.L.; Elmer, M.; Akinboboye, O.; Gorham, M.; Jamerson, B.; McCullough, C.; Pierre, C.; Polis, A.B.; et al. Increasing Diversity in Clinical Trials: Overcoming Critical Barriers. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2019, 44, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Recipients | Living donors |

|---|---|---|

| Candidates expressing interest, n | 5194 | 2217 |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 34 ± 7 | 34 ± 8 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 29 ± 8 | 28 ± 7 |

| Previous children | 2545 (49%) | 1330 (60%) |

| None | 1039 (20%) | 865 (39%) |

| 1 | 571 (11%) | 244 (11%) |

| 2 | 727 (14%) | 510 (23%) |

| 3 | 676 (13%) | 310 (14%) |

| ≥4 | 571 (11%) | 266 (12%) |

| Not reported | 1610 (31%) | 22 (1%) |

| Geographic origin | ||

| United States | 3999 (77%) | 2128 (96%) |

| International | 312 (6%) | 45 (2%) |

| Not reported | 883 (17%) | 44 (2%) |

| Indication for uterus transplantation | ||

| Absent uterus, congenital | 796 (15%) | NA |

| Absent uterus, hysterectomy | 3259 (63%) | NA |

| Present uterus, dysfunctional | 251 (5%) | NA |

| Not reported | 888 (17%) | NA |

| Category | Indication | N |

|---|---|---|

| Absent Uterus, Congenital | 796 | |

| Mullerian Anomaly (Includes MRKH) | 749 | |

| Swyer Syndrome | 1 | |

| Transgender Female | 41 | |

| Turners Syndrome | 1 | |

| CAIS | 3 | |

| Intersex, no Female Sex Organs | 1 | |

| Absent Uterus, Hysterectomy | 3259 | |

| Gynecological Indication | ||

| Abnormal bleeding | Abnormal bleeding, Unspecified | 58 |

| Menorrhagia | 65 | |

| Endometrial Ablation | 1 | |

| Contraception | Contraception | 8 |

| Complications of contraception* | 21 | |

| Infection | Pelvic inflammatory disease | 5 |

| Infection, Unspecified | 16 | |

| Malformations | Bicornuate Uterus | 2 |

| Hypoplasia | 5 | |

| Outflow Obstruction/Hematometra | 3 | |

| Septate Uterus | 1 | |

| Malformation, Unspecified | 8 | |

| Malignancy or Premalignancy | Cervical dysplasia | 64 |

| Malignancy, Adenosarcoma | 2 | |

| Malignancy, Appendix | 2 | |

| Malignancy, Breast | 1 | |

| Malignancy, Cervical | 120 | |

| Malignancy, Colon | 2 | |

| Malignancy, Endometrial | 56 | |

| Malignancy, Gestational Trophoblastic Disease | 6 | |

| Malignancy, Ovarian | 17 | |

| Malignancy, Placental | 3 | |

| Malignancy, Rhabdomyosarcoma | 2 | |

| Malignancy, Unspecified | 48 | |

| Pain | Congested Pelvic Syndrome | 9 |

| Chronic Pain | 29 | |

| Dysmenorrhea | 15 | |

| Endometriosis | 298 | |

| Structural Abnormalities | Adenomyosis | 57 |

| Asherman syndrome | 8 | |

| Myomas | 320 | |

| Trauma | Trauma, Sexual | 5 |

| Trauma, Unspecified | 29 | |

| Urogynecological indication | Fistula | 1 |

| Prolapse | 55 | |

| Reconstruction surgery | 1 | |

| Other | Complication of Surgery | 6 |

| Cysts | 23 | |

| Scarring, Unspecified (Includes Complication of Radiation) | 11 | |

| PCOS | 10 | |

| Obstetrical Indication | Abnormal Placentation | 66 |

| Complication of Miscarriage/Abortion | 16 | |

| Complication of Pregnancy, Unspecified | 22 | |

| Complications of Ectopic Pregnancy | 6 | |

| Complications of Molar Pregnancy | 3 | |

| Postpartum Hemorrhage | 289 | |

| Postpartum Infection | 9 | |

| Uterine Rupture at Delivery | 28 | |

| Other | Claim of Malpractice | 33 |

| Family Pressure | 9 | |

| Personal Decision | 3 | |

| Unspecified Indication for Hysterectomy | 1382 | |

| Present Uterus, Dysfunctional | 251 | |

| Adenomyosis | 3 | |

| Asherman Syndrome | 6 | |

| Endometrial Ablation | 19 | |

| Endometriosis | 11 | |

| Hypoplasia | 3 | |

| Malignancy, Unspecified | 4 | |

| Myomas | 14 | |

| Trauma, Unspecified | 4 | |

| Present but Dysfunctional Uterus, Unspecified | 187 | |

| Unspecified Indication for Uterine Factor Infertility | 888 | |

| Total | 5194 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).