1. Introduction

The Mitrofanoff appendicovescicostomy (or “Mitrofanoff channel”) [

1]is a urinary continent diversion aimed to treat complex urological conditions[

2], such as bladder exstrophy, neurogenic bladder and vesicovaginal fistula. This surgical technique provides for a continent catheterizable tunnel between the umbilicus and the bladder (or neobladder) to pursuit the goals of continence and a painless auto-catheterization [

3]. During the bladder filling, the increased intravesical pressure is transmitted to the submucosal tunnel of the appendix, determining its lumen occlusion, thus ensuring continence[

1]. In patients undergone a contextual bladder neck closure, the Mitrofanoff channel is the only way to access the bladder (or neobladder) lumen. Therefore, in case of complications, such as the presence of stones or clots, the trans-Mitrofanoff passage of endoscopic instrumentation has enhanced concerns about the possible adverse effects, such as continence mechanisms impairments and iatrogenic stomal stenosis.

A frequent complication in augmented bladders is the formation of bladder stones, since the ileal mucus act as a facilitator. The main risk factors for stones formation are: persistent post-catheterization residual, recurrent urinary tract infections and foreign bodies presence. Nowadays, trans Mitrofanoff endoscopic approaches have been described exclusively for stones management, although the open approach is recommended as the safest and easiest technique, especially to treat large and multiple calculi [

4,

5,

6]. In particular, when an access through the Mitrofanoff channel is required, an Amplatz sheath allows the channel protection and the free drainage of the irrigation system, without reaching high intravesical pressures (in particular in augmented bladders)[

6].

Bladder clot retention, also known as bladder tamponade, is a rare condition consequent to a massive hematuria. It usually presents with a cohort of typical clinical signs and symptoms: suprapubic discomfort or bladder overdistension, cystospasm, worsening of hematuria and dysuria. Once abdominal ultrasonography (US) has confirmed the diagnosis, manual bladder irrigation with large bore catheters constitutes a feasible and suggested strategy to progressively clear the urine and allow the clots aspiration. Computed tomography (CT) should preceed any invasive maneuver in trauma setting, to avoid the risk of further damages on an injured low urinary tract.[

7] In neobladders the symptomatology is usually more nuanced, consisting in abdominal pain or tension and dysuria or difficulties in catheter drainage.

Different techniques have been described to treat bladder tamponade, for example the suction with large bore catheters and thoracic drainages, or other surgical tools connected with intermittent suction (syringe or Ellik) or continuous vacuum systems. In case of failure, intravesical agents may help to repeat the procedure, since they reduce the clots size facilitating their aspiration. Nevertheless, in order to prevent the main long-term complications such as stoma stenosis or conduit incontinence, large caliber catheters cannot be used through Mitrofanoff channels: therefore, the suggested highest catheter size is 14 Ch[

3]. Endoscopic or percutaneous approaches may be taken in consideration in refractory cases, while open surgery represents the last choice[

7].

The percutaneous approach and open cystotomy are also the eligible strategies in case of not-catheterizable urethra (surgical closure of bladder neck, severe urethral stricture, neobladder), but they are still invasive - even if minimally – approaches, therefore they require the operatory room availability and the anesthesiologic support[

7].

This work aims to describe our challenging big clot evacuation from an augmented ileal bladder though a Mitrofanoff channel. Among the current literature, no similar cases have been described so far.

2. Materials and Methods

This case report respects CARE Guidelines[

8]. Patient medical history, perioperative and postoperative clinical data and images are described. Surgical instruments, tools’ data and treatment are reported. The patient perspective has been assessed with a qualitative self-evaluation of her personal clinical experience, while pain was objectively assessed with a numeric rating scale (NRS), from 0 (“no pain”) to 10 (“worst pain imaginable”).

Informed consent for publishing purposes was obtained from the patient.

3. Case Report

3.1. Case Presentation

A 17-years-old girl, weight 38 kg and height 140 cm, developed hematuria three days after a surgical cystolithotomy for a 30 millimeters bladder stone. After an unsuccessful bladder washing, she was administered with oral tranexamic acid resulting in the successive hematuria ending. Subsequently, she developed abdominal pain, NRS 7/10, and inadequate bladder drainage at intermittent catheterization, suggestive for bladder tamponade. The bladder lavage allowed a bare evacuation of small clots.

3.2. Medical History

The patient was born premature at 34th gestational week, from a planned caesarean section (CS), due to a maternal malignant neoplasm. She presented a congenital anorectal malformation (cloaca), immediately treated with colostomy. At two years of age, she underwent anorectoplasty and vaginoplasty. Bladder neck closure occurred as a complication and a permanent vesicostomy was performed, resulting in a total urinary incontinence.

Two years before our evaluation, at the age of 16, the patient was treated with bladder augmentation (ileum enterocystoplasty) together with Mitrofanoff appendicovesicostomy.

During the current admission, she underwent uncomplicated cystolithotomy of a three centimeters bladder stone.

3.3. Diagnostic Assessment

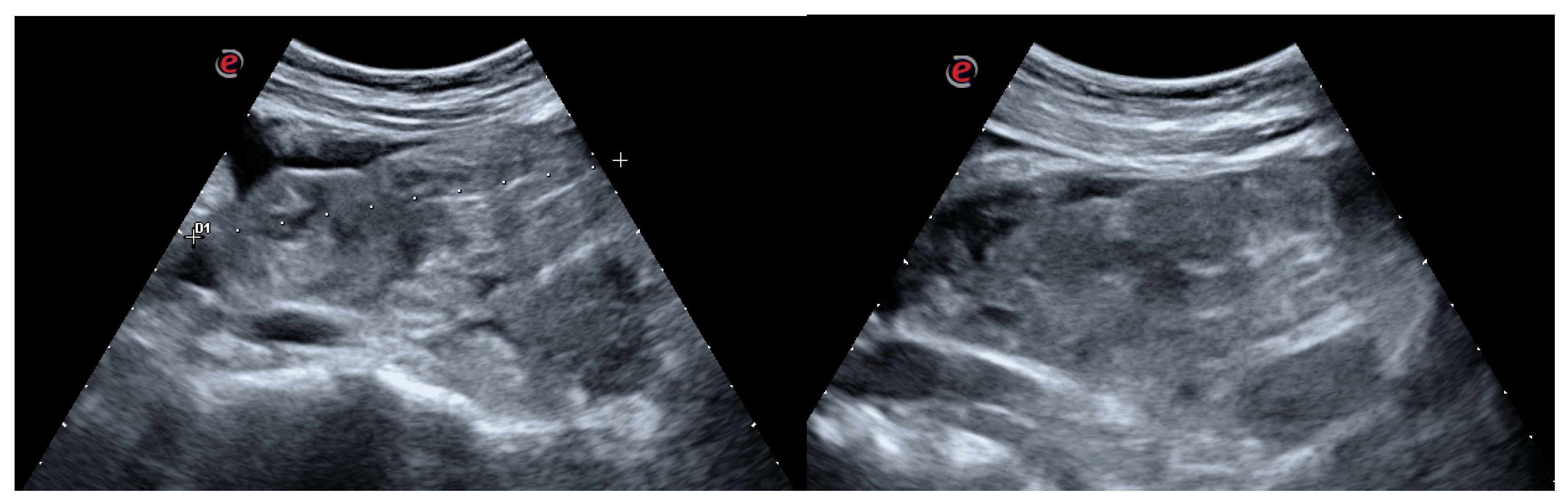

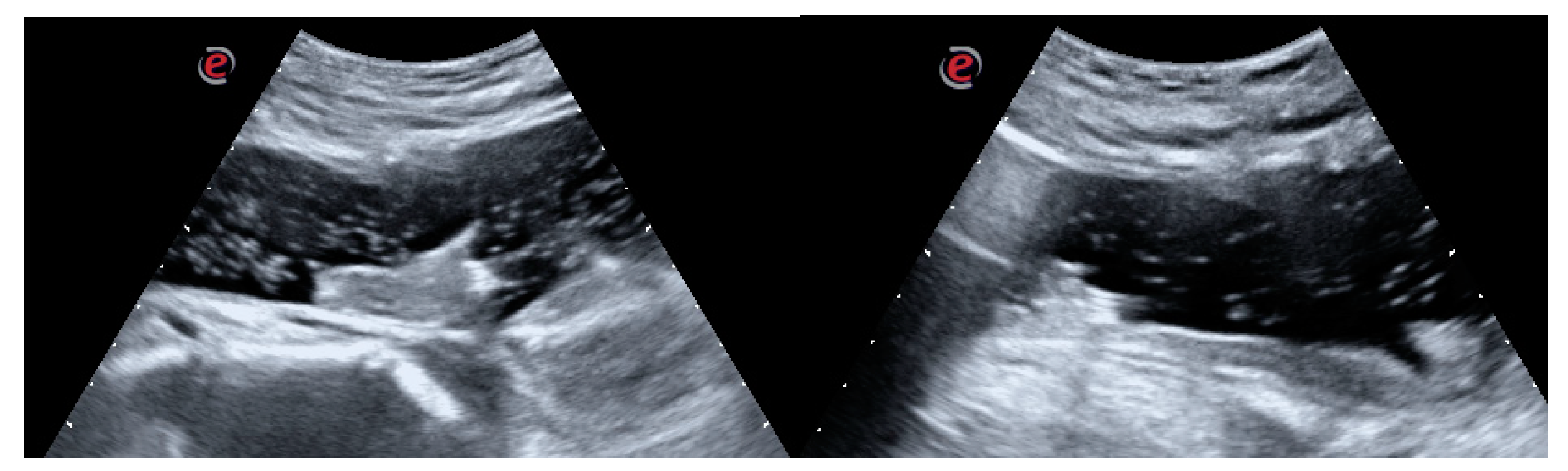

Abdominal US showed a large clot filling the bladder, varying position depending on the patient decubitus. The clot had a 10 centimeters diameter as a main projection (

Figure 1a,b).

Considering the recent open surgery, the persistent abdominal pain and the bladder overdistension, CT scan was performed with the administration of iodinated contrast media (ICM). The late phase showed a big clot occupant the entire bladder lumen, with a ICM accumulation around the clot which appeared hypodense.

3.4. Surgical Management

The clot was neither susceptible of a conservative approach, due to its size, nor likely to be managed through a trans catheter evacuation, after several failed attempts. Large caliber catheters were avoided in order not to damage the Mitrofanoff channel.

The patient was transferred to the operatory room. She underwent general anesthesia and she was placed in supine position. The trans-appendicovesicostomy catheter was coaxially pierced with a hydrophilic nitinol 0,035 inches guidewire (Boston Scientific® – Marlborough, 300 Boston Scientific Way, Massachussetts, USA).

A 10 Ch rigid cystoscope surrounded by its own ureteral 14 Ch sheath (Karl Storz Se & Co. KG® - 78532 Tuttlingen, Germany) was gently inserted though the appendicovesicostomy, coaxially to the guidewire, which was removed after the bladder wall attainment.

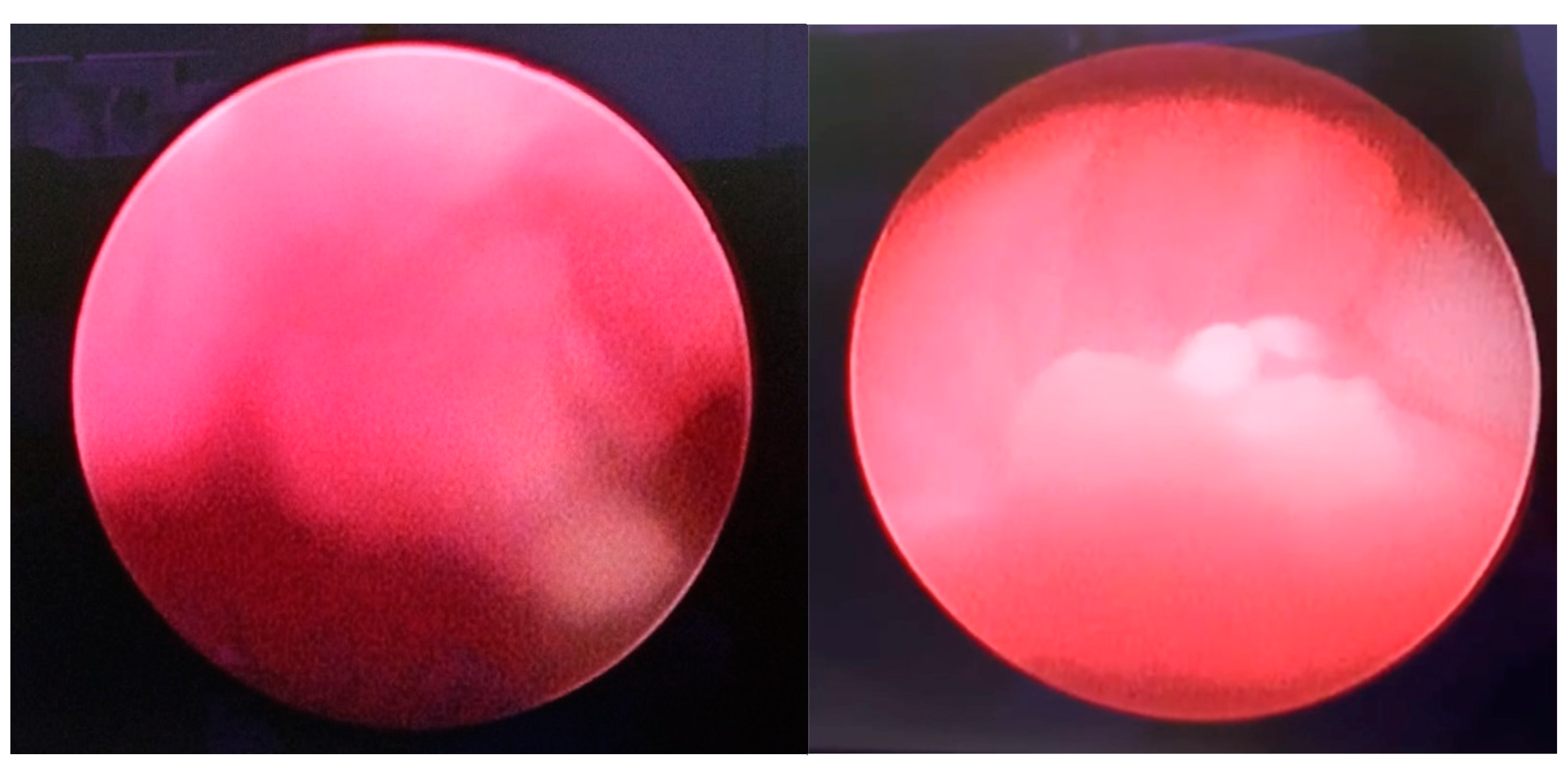

The preliminary endoscopic evaluation confirmed the hematic nature of the clot without any sign of active bleeding (

Figure 2a,b).

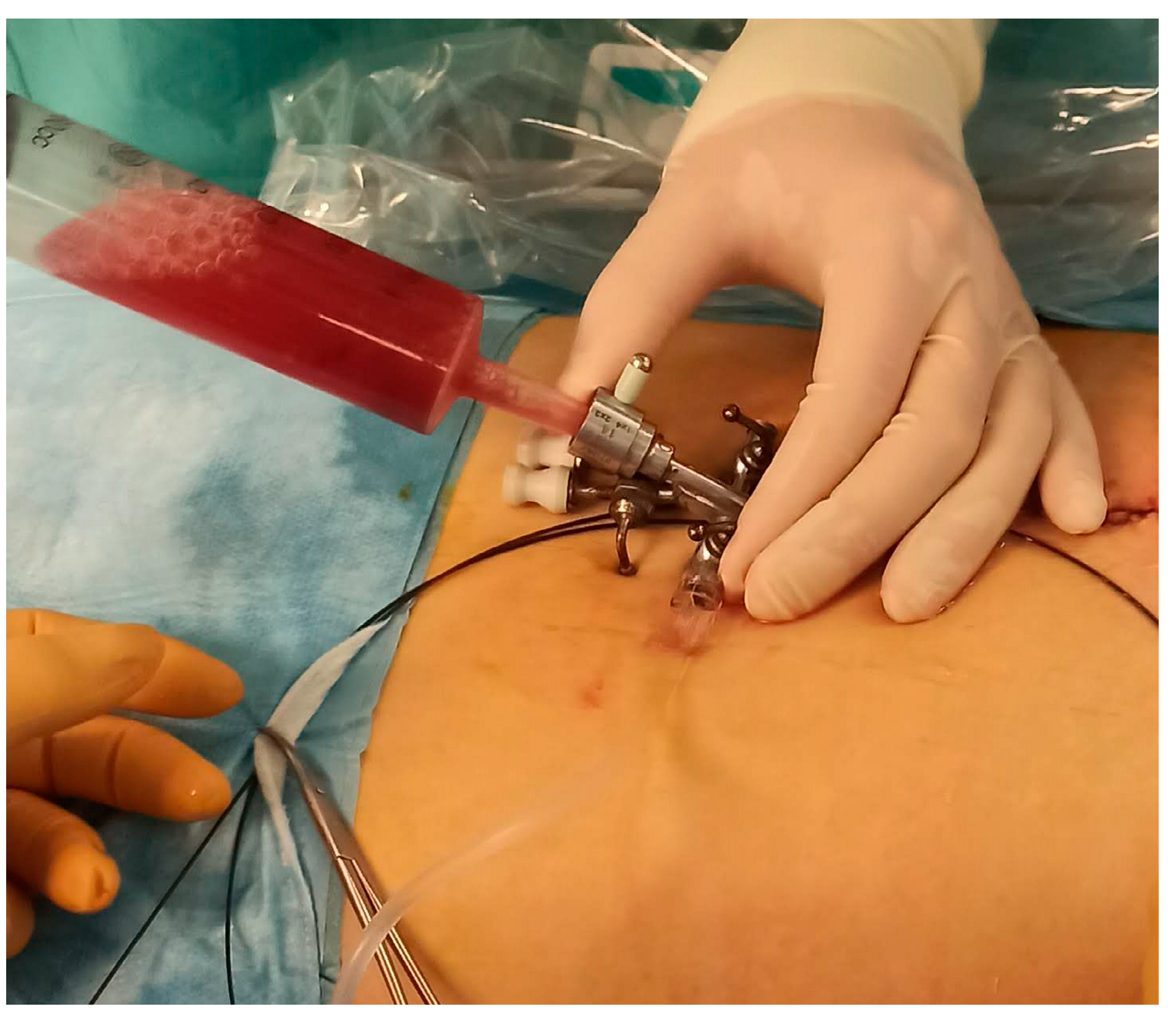

Under the direct vision, the clot was progressively fragmented with the aid of the cystoscope, compressing the clot against the neobladder wall and weakening it. The vacuum effect of the 60 ml syringe permitted a progressive clot reduction in smaller fragments, which were progressively evacuated (

Figure 3).

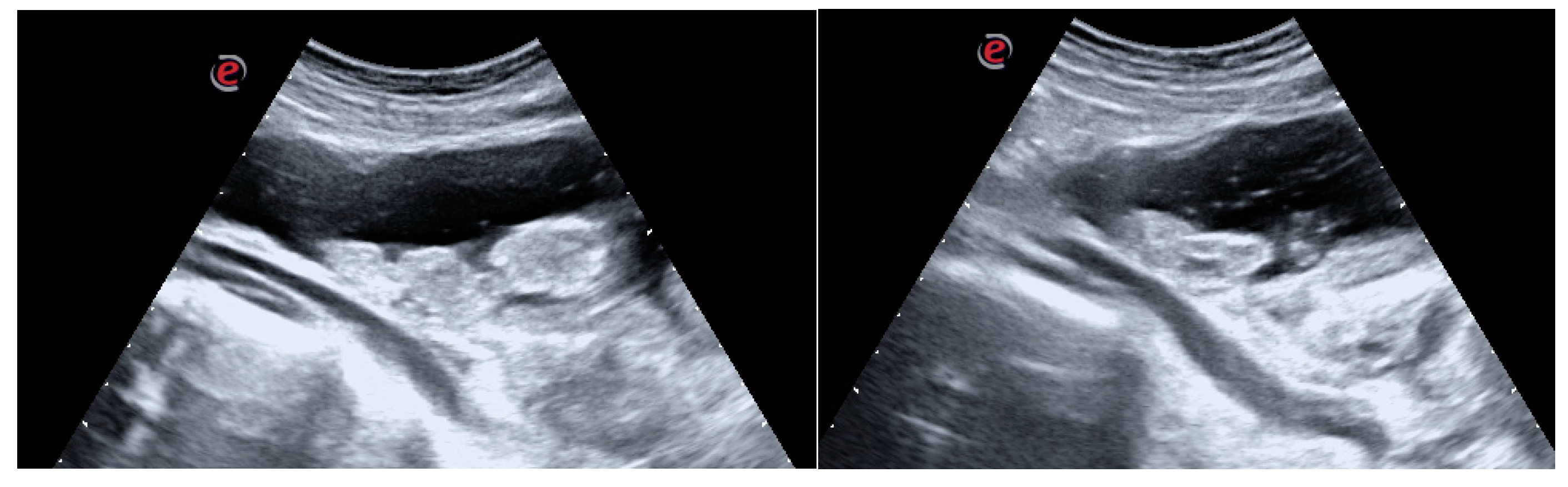

Because of the limited degrees of movement, in order not to damage the appendicovesicostomy, the contemporary US examination was performed till the complete clot disruption (

Figure 4a–d).

The sheath of the cystoscope was removed under direct vision, ensuring the optimal conditions of the Mitrofanoff channel and of the surgical anastomosis.

At the end, a trans-Mitrofanoff 14 Ch catheter was placed to ensure the continuous drainage of the neobladder and to monitor the clearness of the urine.

3.5. Results, Outcomes and Follow-Up

The procedure was performed by two urologists and the complete clot removal was achieved in 130 minutes. The urethral sheath preserved the appendicovesicostomy from the continuous passages of the cystoscope and its swinging movements.

Postoperative period was uneventful. Neobladder catheter was removed after two days. Neither channel stenosis nor anastomosis dehiscence nor incontinence were reported after five months.

3.6. Patient Perspective

The patient reported a full satisfaction for the received treatment, in particular she appreciated the minimally invasiveness of the procedure and the prompt postoperative recovery. The procedure did significantly reduce the pain perception: post-operatively the patient assessed pain up to NRS 3/10. Therefore, no administration of pain therapy was required.

4. Discussion

The Mitrofanoff appendicovesicostomy represents a challenging limit to perform endoscopic procedures in patients with a previous bladder neck closure.

The bladder clots management usually consists in drainage with large bore catheters and manual irrigation [

7,

9]. In case of failure, surgical approaches, intravesical agent instillation and endoscopic procedures have been described for bladder clots evacuation, and the preferrable choice depends on the characteristics of the patient, the surgeon’s expertise and the hospital equipment availability.

In the presented case, since hematuria was due to a recent cystolithotomy, a re-do open surgical approach would not have represented a preferential strategy.

Intravesical agents are a group of substances that, after the trans-catheter bladder instillation, reduce the consistence or disintegrate the blood clots thanks to their enzymatic or chemical activity[

7]. The first attempt in 1993, described by LaFave and Decter, regarded a successful clot dissolution after intravesical urokinase in two boys[

10]. Korkmaz et al. used streptokinase in a 12 years old patient, without encountering changes in hemodynamic and coagulation indexes[

11]. Lastly, Olarte et al. approached a critical neonate in ECMO support with alteplase to dissolve a big clot[

12]. Similar approaches with different agents, such as chymotrypsin plus sodium bicarbonate and hydrogen peroxyde, have been described on adults, lacking for data on pediatric patients[

7]. In the presented case, intravesical agents instillation was not taken into account, since the patient had an ileocystoplasty: these drugs could be absorbed by ileal villi and enter in systemic circulation, carrying the risk of unpredictable effects on blood coagulation[

7]. Truthfully, the urine exposed ileal mucosa develops many changes, such as villous atrophy, reducing its absorptive properties. The metabolic ileal-bladder activity may also be influenced by other factors (e.g. mucus, neo-urinary tract microbiota[

2], enzymes, lymphatic circle absorption), therefore further studies are required to assess these features[

13]. Due to the lack of proper knowledges among neobladder resorptive abilities, an intracavitary treatment was not chosen.

Although the urokinase and streptokinase properties through an oral administration are not significative [

14,

15,

16,

17], their eventual absorption after a direct ileal administration has never been studied. In particular, this anatomical district does not endure most of the digestive processes encountered after an oral administration. Furthermore, in consideration of the recent cystolithotomy, an intravesical plasminogen activator administration would have provoked ad additional bleeding.

Apart from the unexpected systemic effects, other local consequences would have been showed up in case of different intravesical agents administration. For example, intravesical hydrogen peroxyde instillation would have released high volumes of gaseous oxygen, which would have resulted not appropriate for an augmented bladder recently undergone cystotomy. The consequent uncontrollable distension of neobladder walls and its stretching effects on the recent stitches are risk factors for bladder rupture[

18]. Lastly, the relative safety attributed to intravesical agents cannot be extended to the field of neobladders, because of the absence of data about these patients.[

7]

Endoscopic approaches are based on Ellik suction, sometimes preceded by the physical disruption of clots using morcellator or resectoscope. When the urethra is not patent, percutaneous endoscopic approaches and open cystotomy represent the eligible alternatives[

7]. The use of a resectoscope through the Mitrofanoff channel would have mechanically stressed the appendicostomy because of the required swinging movements. In addition, Ellik suction would have represented a risk factor for neobladder rupture, because of the recent cystotomy and the presence of freshly done stitches, as stated above.

Lastly, an endoscopic trans urethral retrograde approach was not feasible, because of previous bladder neck closure.

The patient’s characteristics (a closed bladder neck, an ileal augmented bladder and a Mitrofanoff appendicovesicostomy) forced us to choose a conservative and minimally invasive endoscopic approach. As showed in this case, placing a sheath through appendicovesicostomy allowed the preservation of both stoma and Mitrofanoff conduit, making safe the clots fragmentation and removal. A simi-lar technique was described for stone fragmentation using Amplatz 18-28 Ch sheath by Thomas et al.[

6] However, the cystoscope 14 Ch sheath in this case allowed safe placement in the Mitrofanoff channel, with no risk of conduit damages.

Although this case was managed in general anesthesia to avoid patient’s discomfort and to promptly manage any possible complication, considering the recent open surgery, the minimal invasiveness of this procedure would have allowed a safe executability even in ambulatory settings. In that case, pain relieve techniques, such as nitrous oxide, virtual reality analgesia and other sedation techniques, may be considered.[

7] In addition, this type of approach would result cheaper than a surgical one and does not require an high level of expertise, differently from the percutaneous, endoscopic or surgical ones.

4.1. Limits of this case

This case management has some limits. Through this work, we offer an objective description of a surgical management, nevertheless the main limit consists in its anecdotical singularity. Any type of high scale application needs to be deeply evaluated and cannot be carried out uncritically. Its unicity actually offers only a new perspective of treatment in some selected cases, but a specific case evaluation is strongly suggested if anybody wishes to extend the proposed technique to other patients. As it usually happens for case reports, a generalization is not possible and the clinical results may be different than the expected ones. Their overinterpretation or misinterpretation may induce into the “anecdotal fallacy”.[

19,

20]

5. Conclusions

The bladder blood clots evacuation in a closed-neck augmented bladder with a Mitrofanoff channel presents some challenges related to its management. The absence of a natural endoscopically explorable channel impends the use of a resectoscope and the Mitrofanoff tunnel is highly delicate, therefore suitable to fulfill this scope. The use of urethral sheath simplifies the clots suction and improves the safety of the minimal endoscopic maneuvers. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of neobladder tamponade managed in this way so far.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.C., E.Clemente, M.S., S.G.N.; methodology, M.D.C., E.Clemente, M.S., E.Cerchia, B.T., P.T., S.G.N.; software, M.D.C., E.Clemente, S.G.N.; validation, S.G.N.; formal analysis, E.Clemente, E.Cerchia, B.T., S.G.N.; investigation, M.D.C., E.Clemente, M.S., E.Cerchia, P.G., P.T., S.G.N.; resources, M.D.C., E.Clemente, M.S., E.Cerchia, B.T., P.G., S.G.N.; data curation, M.D.C., E.Clemente, S.G.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.C., E.Clemente, M.S., E.Cerchia, B.T., P.G., S.G.N.; writing—review and editing, M.D.C., E.Clemente, M.S., E.Cerchia, B.T., P.G., S.G.N.; visualization, M.D.C., E.Clemente, S.G.N.; supervision, S.G.N.; project administration, M.D.C., S.G.N.; funding acquisition, M.D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local Institutional Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mitrofanoff, P. [Trans-appendicular continent cystostomy in the management of the neurogenic bladder]. Chir Pediatr 1980, 21, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Della Corte, M.; Fiori, C.; Porpiglia, F. Is It Time to Define a “Neo-Urinary Tract Microbiota” Paradigm? Minerva Urol Nephrol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeratterapillay, R.; Morton, H.; Thorpe, A.C.; Harding, C. Reconstructing the Lower Urinary Tract: The Mitrofanoff Principle. Indian J Urol 2013, 29, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okhunov, Z.; Duty, B.; Smith, A.D.; Okeke, Z. Management of Urolithiasis in Patients after Urinary Diversions. BJU Int 2011, 108, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’Esperance, J.O.; Sung, J.; Marguet, C.; L’Esperance, A.; Albala, D.M. The Surgical Management of Stones in Patients with Urinary Diversions. Curr Opin Urol 2004, 14, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.S.; Smeulders, N.; Yankovic, F.; Undre, S.; Mushtaq, I.; López, P.-J.; Cuckow, P. Paediatric Cystolitholapaxy through the Mitrofanoff/Monti Channel. J Pediatr Urol 2018, 14, 433.e1–433.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Corte, M.; Clemente, E.; Cerchia, E.; De Cillis, S.; Checcucci, E.; Amparore, D.; Fiori, C.; Porpiglia, F.; Gerocarni Nappo, S. Intravesical Agents in the Treatment of Bladder Clots in Children. Pediatric Reports 2023, 15, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CARE Case Report Guidelines. Available online: https://www.care-statement.org (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Avellino, G.J.; Bose, S.; Wang, D.S. Diagnosis and Management of Hematuria. Surg Clin North Am 2016, 96, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaFave, M.S.; Decter, R.M. Intravesical Urokinase for the Management of Clot Retention in Boys. J Urol 1993, 150, 1467–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K, K.; H, S.; F, I.; Z, B.; I, I. A New Treatment for Clot Retention: Intravesical Streptokinase Instillation. The Journal of urology 1996, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Olarte, J.L.; Glover, M.L.; Totapally, B.R. The Use of Alteplase for the Resolution of an Intravesical Clot in a Neonate Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J 2001, 47, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinnab, L.; Straub, M.; Hautmann, R.E.; Braendle, E. Postoperative Resorptive and Excretory Capacity of the Ileal Neobladder. BJU Int 2005, 95, 1289–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, T. Oral Urokinase: Absorption, Mechanisms of Fibrinolytic Enhancement and Clinical Effect on Cerebral Thrombosis. Folia Haematol Int Mag Klin Morphol Blutforsch 1986, 113, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abe, T.; Kazama, M.; Naito, I.; Kinoshita, T.; Sasaki, K. Effect of Oral Urokinase and Its Clinical Application. New Istanbul Contrib Clin Sci 1982, 13, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oliven, A.; Gidron, E. Orally and Rectally Administered Streptokinase. Investigation of Its Absorption and Activity. Pharmacology 1981, 22, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonmoos, P.L.; Straub, P.W. [Absorption and hematologic effect of streptokinase-streptodornase (varidase) after intracavital or oral administration]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1979, 109, 1538–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, B.E.; Proudfoot, A.T.; Vale, J.A. Hydrogen Peroxide Poisoning. Toxicol Rev 2004, 23, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, T.; Wynn, R. The Clinical Case Report: A Review of Its Merits and Limitations. BMC Res Notes 2014, 7, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Corte, M.; Amparore, D.; Sica, M.; Clemente, E.; Mazzuca, D.; Manfredi, M.; Fiori, C.; Porpiglia, F. Pseudoaneurysm after Radical Prostatectomy: A Case Report and Narrative Literature Review. Surgeries 2022, 3, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).