1. Introduction

This article examines the lexical-semantic and pragmatic characteristics of Chinese food taste adjectives. The article analyzes errors in the translation of adjectives meaning taste in Chinese into foreign languages, as well as the stylistic features of adjectives of taste. Through a case study, the article identified problems in the translation of taste adjectives in Chinese, which were translated incorrectly by translators and students into Uzbek.

Since the beginning of time, humans have considered food to be a daily necessity, the primary tool in their struggle for survival. The process of preparing and eating food, which has become a physiological phenomenon that an individual must deal with daily, occupied a specific linguistic “territory” in the language during the early stages of human evolution. The concept of “food” has a special place in each nation's NWP (National Picture of the World). The world is an existence that can be consumed or not consumed in the mind of a hungry man. This global cognitive appeal serves as the foundation for an individual's attempt to (Olyanich, 2004).

It is a natural process for Chinese cuisine to enter every country as the Chinese language and culture develop. The issue of correct description of Chinese national dishes in the menus is on the agenda during this process. The reason for this is that every customer has the right to be fully informed about the food they are eating as well as the food and products available when they enter the restaurant. Unlike Asian cuisine, CIS cuisine does not have a sweet or bitter flavor. For example, because the technique of caramelizing fruits and vegetables is not used in the preparation of Uzbek dishes and pastries, if the words “caramelized banana” and “caramelized pear” are translated into Uzbek as “karamellashtirilgan” (with the method of calking), this technique is completely unacceptable to the Uzbek housewife. The recipe may become incomprehensible due to unfamiliarity. In this case, three or four actions can be given in sequence, which is carried out by the caramelize command in English: 1. Melt a small piece of butter in a pan over medium heat; 2. When the oil is hot, add the bananas and brown sugar; 3. Bananas are dug from the sugar until they form a brown coating; 4. Caramel continues to boil until the sauce thickens (G. Odilova, Dsc dissertation, 2021).

The cuisine of the CIS is devoid of all flavors that could be described as sweet, bitter, sour, moderately harsh, severely bitter, or sweet-sour. For a customer who has never experienced these flavors before, trying new dishes can be a dangerous endeavor. For instance, in Uzbekistan, digestive disorders claim the lives of 4.1% of the population annually. The extraordinarily high-fat content of Uzbek cuisine is the cause of this. Uzbek customers can prefer Chinese light food with delicate flavors.

For those with gastrointestinal issues, however, foods having a bitter or sour flavor might be highly harmful. Translation or editing of Chinese food recipes to design equivalent menus the target language for restaurants is necessary for this reason. The primary qualities of gluttonies that best exemplify the taste adjectives of Chinese food were listed at the outset of this study.

We looked at the meal comments on the restaurant menus in Tashkent, Bishkek, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan to assess the degree of translation. By examining these menus, one may accurately interpret Chinese flavors that are absent from the cuisine of the CIS nations. The purpose was to evaluate how well the translations matched the original. The reason is that visitors of Chinese eateries in these areas frequently lament that the menus descriptions about meals are ambiguous and unable to fully educate the customers the food's flavor. The authors looked at the difficulties encountered while translating adjectives that describe food's flavor seeking understand why this occurs.

The adjectives of Chinese national dishes that were incorrectly translated in the translation of the menus of Chinese restaurants in the aforementioned regions sought to understand how Chinese philology (in the bachelor's degree) Uzbek students with a level of HSK level 4 can translate and understand them.

To explore the lexical-semantic characteristics of the adjectives in Chinese that denote taste, inaccurate translations were submitted to a comparative – lingo pragmatical analysis during the experiment. The authors also sought to ascertain the cause of the difficulty that aspiring philologists and translators have in comprehending and translating these adjectives.

2. Literature Review

The issues with food discourse and the translation of food names have been studied several scientists in Chinese linguistics (Lin Hong 2009, Yu Zhang, Jiaying Fang 2020), but the lexical-semantic analysis and translation of complete adjectives expressing the taste of Chinese food have not been the subject of critical analysis.

Several of the original names of Chinese foods are translated into English in the article林红 Lín Hóng “中国菜名英译的文化错位与翻译实践” 2009 by Lin Hong, «Linguo-cultural faults and translation practice in the translation of Chinese food into English» Understanding a culture involves looking at the mistakes and omissions made when words are translated literally and when the reality is interpreted. Lin Hóng asserts that if you do not recognize that the name of the dish is a component of Chinese culture, it is possible to make a mistake when translating food names from Chinese to English. For instance, the famous Sichuan meal is referred to as “鱼香肉丝” (literally: Fish-flavored thinly sliced meat pieces). The meal does not, however, contain fish meat. Although, the dish's name contains the word “fish” the Chinese are aware that no fish is present in it. The Brits, who are unfamiliar with Chinese cuisine, interpret the name of this dish in English as «Fish-flavored Pork Slivers» or «Fish-flavored Pork Shreds» based on the dish's name. When the Chinese say «fish-flavored» they mean pork with a fragrant, smoky flavor. They can acknowledge the presence of fish in the dish and comprehend it. In actuality, pork is the main ingredient in the dish “鱼香肉丝” and no fish items were used in its preparation (Lin Hóng 2009). Lin Hong examines the issues surrounding Chinese translation as an illustration considering the issue of cultural misunderstandings in the translation of numerals in Chinese cuisine names: Chinese people frequently employ the lucky numbers 双,三,五,八 (two, three, five, and eight) in the names of their foods. For instance, the translation of “三元牛头” (Three meals) is «Ox head with tri-colored veggies» Beef, red and white radishes and three different kinds of vegetables, all sliced into circles, make up this dish. According to Lin Hong, the meaning of 三元 (three veggies) is misunderstood and translated into the English language of this dish. In truth, when we look at the history of the dish's name, we can see that there is a claim that the dish's name refers to the food of the competition victors in ancient China. The 童生Tóngshēng (Initially examination), the town examination, the general examination, and the palace examination were the four categories used to categorize the official imperial examinations in the Ming and Qing dynasties. The dish may have been consumed with hopes of success, advancement, and crossing the finish line because the number 3 in the dish's name relates to the competition's winners. Ling Hong claims that the English translator rendered the dish's name literally, obscuring the dish's concealed philosophical connotation. (Lín Hóng 2009). Naturally, the implicit meaning of the name of this meal should be clarified or referenced in the text whenever it appears in a work of fiction or whenever a pragmatic relationship is made between the name of this dish and the word victory. But, in our opinion, the English translator's translation of the dish's name on the menus is accurate. The menus shouldn't contain a lot of text or quotations for two reasons: first, the consumer should be able to understand the translation of the dish's name, and second, the translation should include information about the dish's ingredients. In addition, Lin Hong noted that the translation of food names associated with person names in Chinese food names, the translation of similes, the errors made during the translation process associated with the legend of Chinese food names, history, religion, and literature, and the translation of magical wishes in Chinese food names.

张昱, 方嘉莹 “翻译作为跨文化交际的媒介:以澳门菜单为例” In his article titled “Translation as the mediation of cross-cultural communication: the case of menus in macau” which is based on corpus linguistics analysis, (Yu Zhang, Jiaying Fang) explores the mistakes and shortcomings of Macao menus. In this study, 71 menus from restaurants in Macao were analyzed, and 84.5% of them complied with linguistic standards and contained only a few details. 2.8% of texts have a high rate of esthetic faults, while 14.1% of texts are pragmatic functional translations. 1.4% of menus were found to be wholly untranslated following the criteria. The equivalence level, functional level, and aesthetic level of the translation are all impacted differently by different translation approaches. (Yu Zhang, Jiaying Fan, 2020) When menus names are rendered incorrectly, it demonstrates the translator's lack of subject-matter expertise, the mechanical nature of the translation, the presence of numerous errors in the rendering of culturally significant words and concepts, the decline in interest of foreign visitors in the country's cuisine, and a subsequent decline in restaurant patronage. A menu that is accurately translated is a popular seller. The cornerstone of a successful connection with the restaurant's customers and a driver of increased sales, according to academics, is a complete translation of the menus. (Gulnoza Odilova, 2021)

熊欣 “跨文化交际理论下的中国菜名英译研究” From the perspective of cross-cultural communication, Xiong Xin in his Ph.D. dissertation (2013 titled «On the C-E Translation of the Names of Chinese Dishes), he proposes that, given that Chinese dish names are typically written freehand or in the shaky script, “transliteration + translation” “transliteration and literal translation” and “transliteration + interpretation + literal translation of the image” should form the basis for future Chinese language in the process of intercultural communication of Chinese food names. (Xiong Xin, 2013)

3. Methodology

The word gluttony is derived from the Latin verb glutting, which means “to swallow” and the Old French and Middle English noun gluttony which means «throat» Food processing in its totality, from locating it to processing semi-finished goods to creating a ready-to-eat product, is included in the manufacturing of glutonium (Derjavetskaya, 2013).

While learning about the images of the gastronomic world aids in the development of a clear picture of the life, worldview, culture, and social environment of the country, researching the linguistic aspect of gluttonous discourse aids in deepening the understanding of the gastronomic NLPW (National Linguistic Picture of the World) of the language. The gluttony cognitive system in NLPW is mentioned by A. V. Olyanich in his monograph “Presentational theory discourse” According to him, the term glutonic correlates with the idea of gastronomy (which includes the knowledge of culinary art and its application) and is compatible with the glutonic cognitive system of any ethnocultural concepts. The glutonic discourse is also closely related to the linguistic and ethnocultural concepts that include the process of food preparation.

The most concise and logical arguments for gluttony discourse were made by A. V. Olyanich. The restaurant is described as the gluttony communication hub, and the menus is described as a tool of communication, based on the form of the gluttony cognitive system he suggests (Olyanich.2004).

The next stage is to produce a menus, that is, a menus, after naming the food and describing its preparation (i.e., developing a recipe). The definition of “Menus” in English dictionaries is a list of the foods you can order at a restaurant. The Latin term minutes served as the basis for the French word Menus (Heimann, Jim Heller, Steven, and Mariani, John. Menus design in America: A Visual and Culinary History of Graphic Styles and Design 1850-1985: Taschen, 2011). The menus's stylistic architecture, style, and graphics are examined by linguists from around the world, who then define it differently. Redis claims that the menus's primary goal is communication. The menus, in Kershev's opinion, is a sales tool that might affect the customer's decision. Peyves calls the menus a metaphorical «silent salesman».

According to Dr. Ronald Cichy and Philip Hickey, the Menus acts as a bridge between hunger and fulfillment, and its success is directly correlated with its layout (Yung Wang. 2012).

The Song Dynasty, which controlled China from the X to the XIII century, is where the history of the menus begins. Like contemporary cookbooks, they had two columns that listed the names of the dishes (Gernet Jacques. 1962). The 18th century saw the introduction of contemporary menus throughout Eastern Europe. The first modern menus were created by French restaurateur Pierre Boulanger, who in 1765 displayed the list of meals cooked that day and the chef's name outside his restaurant for the first time on a sizable sheet of paper with lovely designs (Fellman Leonardo F. 1981)

The menus has gotten better every year, and it is now a genre of gluttonous discourse with its own creative style, sorts, and unique terminology. As challenging as it is for the translator to translate something into another language, creating a menus demands considerable expertise and understanding from the author and designer of the menus. It is important to have a thorough understanding of the structure, methods, and different types of menus before discussing the difficulties with menus translation.

The menus should be simple, clear, and error-free in both language and spelling. Even the least profitable dish can become a top seller with careful, menus planning. One of the urgent challenges of contemporary linguistics is the stylistic analysis of gluttonous discourse genres, nominees of national food, and research of their semantic and etymological properties. It is impossible to develop explanations of the national food nominees if the lexical-semantic characteristics of the food nominees, the motive for naming them according to the nature of their preparation, and the preparation itself are not researched. The translator cannot translate a dish into a menus without understanding its characteristics. It's critical to create models for translating food nominees so that national dishes aren't just transliterated in restaurants (G. Odilova, Dsc Dissertation, 2021).

To correctly translate the names of the dishes into the menus, the adjectives related to the taste, shape, and preparation of the food must be given correctly in the translation. The adjective is described as follows by Z.T. Kholmonova in her textbook «Introduction to Linguistics» (2007): 1. The subject denotes an object's sign; it provides the answer to the question “how”

An adjective is a word group that designates an object in linguistics. The word sign has a broad definition in grammar and refers to a sign based on its color, size, form, appearance, feature, etc., such as red, wide, pleasant, etc.

Adjectives are gradable words that mostly describe an object and sporadically describe an action: a red pen, a white dove, speaking well. (Sayfullayeva R.R., Mengliyev B.R., Boqiyev G.H., Qurbonova M.M., Yunusova Z.Q., Abuzalova M.Q. , 2009, )

There are nine categories of adjectives in this study guide: 1. A distinguishing feature. 2. A status adverb. 3. A formal adverb. 4. A property that denotes color. 5. Tasty attributes. 6. The smell. 7. Measurement. 8. Positional quality. 9. Adverbial adjective.

Words that connect to a noun-subject and indicate its sign are called adjectives. (U. Amonov, 2021)

In Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, adjectives are characterized

as expressions “that alter, clarify, or adjust the meaning contributions of nouns”, to allow for the expression of “finer gradations of meaning” than are possible through the use of nouns alone (Huddleston and Pullum 2002).

(See Dixon and Aikhenvald 2004 for a detailed discussion of the cross-linguistic properties of adjectives.)

Some researchers, including Lewis (1970), Wheeler (1972), Cresswell (1973), and Montague (1974), have taken the existence of non-intersective interpretations of adjectives as evidence that adjectives do not denote properties, but rather must be analyzed as expressions that map properties into new properties. Recent work on semantic relativism (see chapter 4.15) has focused extensively on differences in truth judgments of sentences containing adjectives of personal taste like tasty and fun (see e.g. Richard 2004; Lasersohn 2005; MacFarlane 2005; Stephenson 2007; Cappelen and Hawthorne 2009), and researchers interested in motivating contextualist semantic analyses have often used facts involving gradable adjectives (recall the judgments in (23) which show that the threshold for what “counts as” tall can change depending on whether we are talking about jockeys or basketball players) to develop arguments about the presence (or absence) of Contextual parameters in other types of constructions, such as knowledge statements (see e.g. Unger 1975; Lewis 1979; Cohen 1999; Stanley 2004, and chapters 3.7 and 4.14).

4. Data collection techniques

For our scientific investigation, we first examined the menus of Chinese restaurants in Uzbekistan and the CIS countries, identifying the Chinese taste adjectives that were incorrectly translated on the menus. Following that, we will attempt to determine the number and cause of translation errors by translating sentences containing these adjectives to determine the level of understanding of these adjectives by graduates of the Chinese language translation department. By incorporating the translation of full adjectives into a linguistic analysis, we will attempt to determine why these adjectives are translated incorrectly. Following that, recommendations are developed by studying the main educational literature and textbooks in this direction to, eliminate the cause of this error.

To conduct our scientific investigation, we first looked at the menus of Chinese restaurants in Uzbekistan and the CIS nations and noted any Chinese adjectives that had been mistranslated. Then, to assess the degree of comprehension of these adjectives by the graduates of the Chinese language translation department, we will attempt to identify the quantity and cause of translation errors by translating the sentences using these adjectives. By putting the translation of entire adjectives through linguistic analysis, we will attempt to determine why these adjectives are translated improperly. Afterward, by examining the primary academic literature and textbooks in this area, suggestions are made to get rid of the error's root cause.

5. Research design

The lexical, semantic, and cultural meanings of taste adjectives in the Chinese language are analyzed in the conducted research. Errors made by translators in the translation the following adjectives in Chinese are studied from the point of view of translation studies. Transformational methods for translating adjectives in Chinese are developed. The linguistic and cultural aspects of the adjectives of taste in the Chinese are revealed based on sources in the Chinese language and literature.

The study that was undertaken examines the lexical, semantic, and cultural meanings of taste adjectives in Chinese language. Chinese taste adjectives' translation mistakes are examined from the perspective of translation studies. Analyses of which adjectives in Mandarin are translated using transformational approaches. Based on sources from the Chinese language and literature, the linguistic and cultural facets of the Chinese adjectives of taste are disclosed.

6. Results

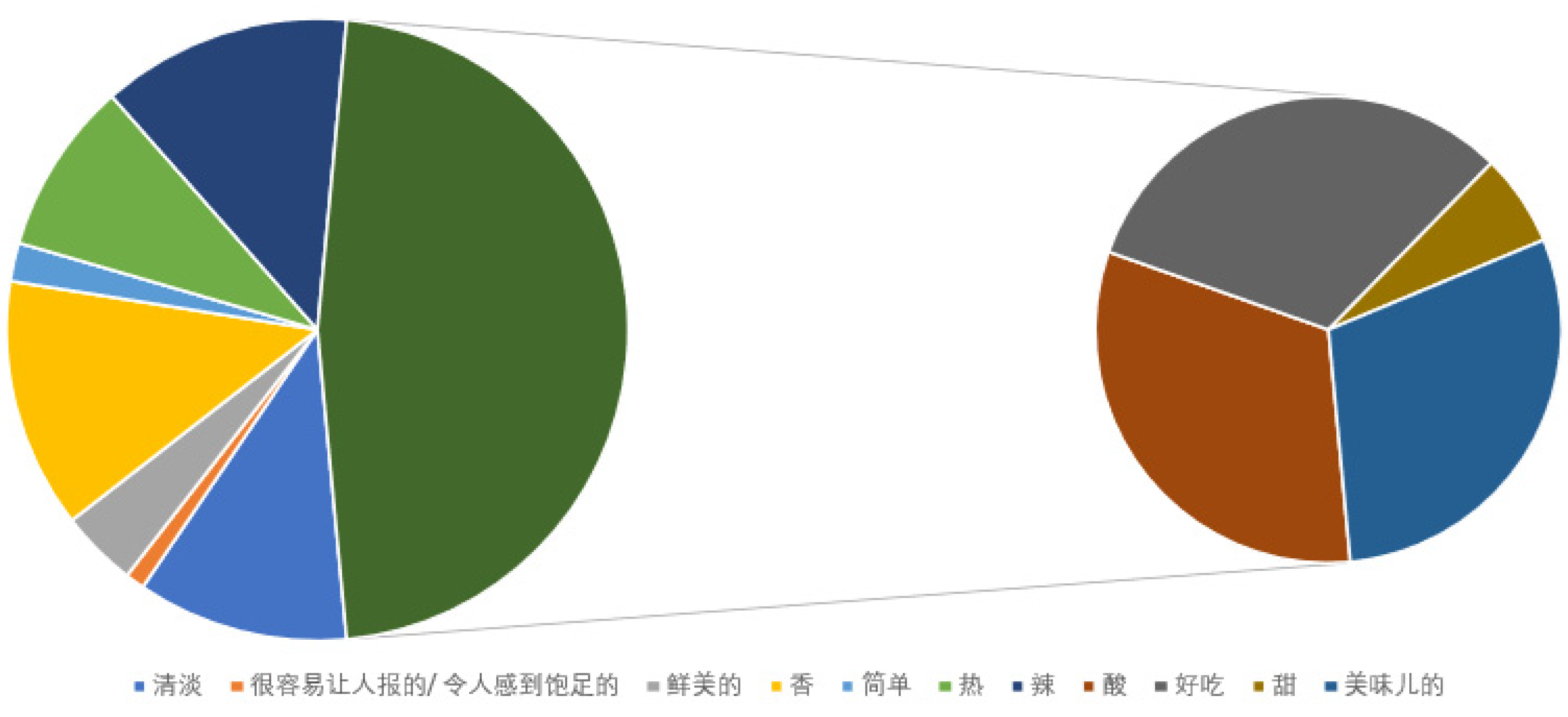

Figure 1.

The experiment produced a general result.

Figure 1.

The experiment produced a general result.

The following sentence were provided to the students to translate from Chinese into Uzbek: 海藻是中国最受欢迎的食品之一,因为它味道鲜美、清淡、营养丰富- Seaweed is one of the most well-liked foods in China since it is tasty, light, and nutritious.

The adjectives light, nutritious, and wonderful taste are in the first sentence of the examples; fried, typical, and aromatic adjectives and adjectives are used to describe the food in the second sentence; easy-to-prepare food and hot qualities are in the third sentence; bitter and sour adjectives are in the fourth sentence; a fragrant expression and a bitter taste are in the fifth sentence; the bitter taste is in the sixth sentence; delicious is in the seventh sentence; and sweet is in the eighth sentence. Sixty students were given these sentences to translate from Chinese into Uzbek.

The following errors were made by students when translating the aforementioned adjectives only the first sentence and other results we will give in the general results of the experiment:

1. Seaweed is one of the most well-liked foods in China because it is tasty, light, and healthy - examination of the first clause:

Simple (food) 45 students successfully applied the 清淡 qīngdàn adjective. One student used the term 零食 língshí, while 14 students used 轻 qīng.

清淡 qīngdàn is the original Chinese translation for the “light” character brought about by the food's preparation and digestion process. This adverb is more frequently used when describing cuisine. The term 清淡qīngdàn “汉语词典” is used bland meals with a mild flavor and color. For instance:

The adjective of “清淡” qīngdàn is referenced in the passage “平生不经尝五味丰腴之物,清淡安全,所以致寿” in Ming Zhang Ding's «Conversations of Fang Zhou»- Consume a lot of healthy food regularly rather than heavy meals. The adjective 清淡qīngdàn in this phrase refers to light fare.

In the third chapter of the fifth chapter of the masterpiece of Chinese traditional literature «A Dream of Red Rose” 清淡is used as follows: “晴雯 此症虽重,幸亏他素昔是个使力不使心的人,再者素昔饮食清淡,饥饱无伤的。- «Fortunately, Xing Wen was a guy who did not use his strength even though his illness was severe. Su Xi also ate diet cuisine that was light and healthy. The adjective 清淡 is used in this example's definition as well.

In the 37th chapter of «My Twenty Years of Strange Adventures» it is stated that «雪渔 道:我们讲喫酒,何必考究菜,我觉得清淡点的好». Xu Yu remarked: «On vino about that, I believe it would be wiser to purchase something lighter. 清淡qīngdàn adjective is used in its meaning.

Three definitions of the characteristic 清淡 qīngdàn are provided in the «Dictionary of Modern Chinese Adjectives». The first one has a light and a strong, not light, meaning: 清淡的花香弥散在小院中。- A faint floral scent drifted from the little yard.

The second definition is to conduct a modest amount of business: 现在服装业的生意很清淡。-The textile industry's current turnover is very low.

清淡is the translation of «food without fat, easily digestible» in the third sense of the Chinese word 清淡:我愿意吃清淡的食物- I like to consume modestly.

The comments made about the adjective 清淡in both dictionaries serve as evidence that this word was generally used properly when the sentence was being translated from Uzbek to Chinese.

However, it is incorrect to refer to the dishes' adjective as 轻 qīng, which conveys the load's lightness and is directly translated from Uzbek to Chinese. The definition of the word 轻 qīng is given as follows on page 176 of the «Dictionary of Modern Chinese Adjectives»: (1995)

1. Lightness: 她的身体很轻。- It is incredibly light.

2. The lack of quantity, the lightness of the level: - 运动员们备力拼搏,轻伤决不下赛场。- The athletes worked hard and did not leave the field due to minor injuries.

3. Unimportant meaning: 这次你的责任不轻呀! - This time your responsibility is not light!

4. Simple equipment and low load: 内蒙古有支非常有名的轻骑兵。- There is very popular light cavalry in Inner Mongolia.

5. Easy: 我爱听轻音乐。- I like to listen to light music.

6. To use less effort: 一定要轻拿轻放,不可大意。- Take it slow and put it down slowly, carelessness is not good.

7. Casual, careless, not serious: 切勿轻举妄动。- Don't do it carelessy.

The use of the adjective轻 qīng of food in the food discourse has led to rhetorical, methodological, and semantic confusion because there is no information about the easy digestion or preparation of food among the meanings provided in the explanatory lexicon.

零食língshí Snacks that are simple to consume and digest are referred to as.

According to the «Online Annotated Dictionary of the Chinese Language» it is a supplemental food item consumed in between main meals and implies a snack. Products that are typically eaten in China in addition to three meals a day. Candy, dried fruits, pistachios, almonds, and canned items are a few examples of such products. In the writings of well-known Chinese women authors Bing Sin and Ding Lin, the term “零食 língshí” appears.

Bing Xin, a children's author, penned «Dispatches to a Young Reader» with the phrase “我从病后是不吃零食的”- The literal definition of the phrase 零食 língshí snack: «I haven't had a snack since I was sick a snack». In his novel «Pine Nuts» author Ding Lin, who enjoys bringing attention to the suffering of women, wrote, “在白天的时候,这里常有一些卖零食的小担。- «In the daytime, there are small stalls selling snacks. In the word «零食 língshí» the word «零食 língshí” is also used to refer to a refreshment. The word «零食» cannot be used in the translation provided for the exercise, according to the definitions provided. It doesn't line up with the translation's or the sentence's sense. The index of sentences translated by upcoming translators is based on the research above:

| № |

Light (food) |

The type of translation |

Result |

| 1. |

清淡 qīngdàn |

Equivalent translation |

45 - Number of students who translated correctly |

| 2. |

轻 qīng |

Functional translation |

14 students in the interference method |

| 3. |

零食 língshí |

Translation error |

1 student made a mistake |

The first line of the analysis's translation of the word «nutritious» is as follows: 5 students accurately translated the phrase «the adjective of nutritious (food)» as “令人感到饱足的” lìng rén gǎndào bǎo zú de” while 55 students used the phrase «营养丰富 yíngyǎng fēngfù « to convey the meaning of the word.

On the Chinese language website «Daily Learning English» it is written, “形容食物好吃除了” delicious 你还会别的吗? In the article entitled (Do you know other adjectives for the taste of food other than delicious?), the following sentence is included in the explanatory definition of 令人感到饱足的 lìng rén gǎndào bǎo zú de, which expresses the meaning of hearty:

螃蟹虽然好吃,却容易让人感到饱足。- Crab is not only scrumptious but also very nourishing.

The words «令人感到饱足的 - lìng rén gǎndào bǎo zú de” together denote the food's nutritional value. The passive participle word 令 lìng is frequently used interchangeably with the noun 让 ràng, but this does not alter the sentence's overall meaning. The richness of the food is what the explanation for the Chinese character 令人感到饱足的 lìng rén gǎndào bǎo zú de signifies.

The term «compound» is more commonly known as «很容易让人饱的 hěn róngyì ràng rén bào de» which refers to a substance that readily fills a person in line with its nutritive adjective. This meaning is the most practical for Chinese people. Examples include: 蛋白、纤维多的食物, 更让人饱。 如果这么比,就会发现,在蛋白质、脂肪、碳水化合物大产能营养素当中,蛋白质的饱腹感最高,脂肪最低。- Foods high in protein and plant bases are more nutrient-dense When you compare the three major nutrients that provide energy-protein, fat, and carbohydrates—you'll see that protein is both very low in fat and rich in saturated fat.

The word 让人饱 ràng rén bào means “nutritious” in this context. From the analysis, we can conclude that when we translate the nutritious adjective into Chinese, 令人感到饱足的 lìng rén gǎndào bǎo zú de (one feels full), 很容易让人饱的 hěn róngyì ràng rén bào de (easily which satiates a person), is translated interpretatively in forms such as 让人饱 ràng rén bào (which satiates a person). Since there isn't a single adjective in Chinese that can be translated exactly to mean «nutritious» the meanings may be altered. Instead, the Chinese use descriptive adjectives. We can see that many students rendered this sentence incorrectly. (5 students were able to translate it correctly)

55 students substituted 营养丰富 yíngyǎng fēngfù, a functional equivalent rich in nutrients, for its nutritive adjective. To examine:

营养- yíngyǎng- is a term related to the noun group that is required to ensure the growth, development, and other essential activities of the organism, according to the renowned Oxford Languages online dictionary. is a collective word for nutrients: 食物营养是身体健康的最重要的因素,因为人是从一个小细胞发育成长成人的,食物营养是物质的源泉 - Since a person is only made up of cells and food is the source of nutrition, food is the single most essential factor in determining one's health. Speech for nourishment is 营养- yíngyǎng.

In addition, the expression 营养- yíngyǎng “这是词人向古典诗词学习,从中吸取艺术营养的实践。” can be used to characterize a person's emotional and spiritual nourishment. - «This is the practice of poets taking lessons from classical poetry and getting artistic nourishment from it» reads the eighth chapter of the 1982 book «Reading». The artistic meaning of food in this phrase is to provide nourishment; it has nothing to do with the food's nutritional value.

In its second meaning, which is connected to the 营养- yíngyǎng word family, it denotes that the organism takes in the nutrients required to ensure important processes like growth and development. For instance, the word «营养身体» refers to bodily nourishment. According to the study, the lexeme 营养- yíngyǎng cannot be an adjective because neither of its two meanings concern to the richness of the food. This function is translated into Chinese using a counterpart that is similar to the word “nutritious” in English. These are the outcomes:

| № |

Nutritious (food) |

The type of translation |

Result |

| 1. |

很容易让人饱的/ 令人感到饱足的 - hěn róngyì ràng rén bào de/ lìng rén gǎndào bǎo zú de |

Annotated translation |

5 - The number of students who translated correctly |

| 2. |

营养丰富 yíngyǎng fēngfù |

Functional equivalent |

55 students used it |

In the translation of the first sentence under analysis, 7 students used the Uzbek adjective 鲜美的xiānměi in their translation, 味道好吃 wèidào hào chī 2 words, adjective有味儿 yǒu wèi er – 1 student, 12 students used 佳 jiā, 美味 měiwèi – 10 students, 肴yáo -1 student, 有闻精彩 yǒu wén jīngcǎi- 1 student and 16 students used the definition of 味道好wèidào hào. Following is the analysis:

On page 231 of «The Dictionary of Modern Chinese Adjectives», the adjective 鲜美的xiānměi de is given two different meanings:

1. For food products, the taste is delicious: 餐桌上摆放着鲜美的菜肴,令人食欲大增。- There are wonderful dishes on the table, and it tickles the appetite.

2. Qualifying the abundance of plants and vegetables: 城市路旁的树上开满了鲜美的花朵。- The streets of the city are now full of budding trees.

The adjective 鲜美的xiānměi de is based on the above analysis, it is used to express the wonderful taste of food, and given in Uzbek, Seaweed is one of the most popular dishes in China, it is light, nutritious and has a wonderful taste. fully corresponds to the wonderful word in the sentence “has”. When translated using this adjective, the sentence meets the translation requirements.

味道好吃 Wèidào hào chī The words 味道 wèidào - taste (noun word) and 好吃hào chī (adjective word) are analyzed below in our paper. It means delectable when interpreted literally. To ensure that there are no grammatical or stylistic mistakes, the translator must accurately translate every word used in the written translation process. It might be sufficient to use the word to convey the wonderfulness of the flavor. The taste is excellent, but the sentence's meaning suggests that it does not equivalently convey how great the taste is “味道好吃 wèidào hào chī”:

One student, who contributed to the experiment analysis with his translation work, used the phrase «有味儿 yǒu wèi er» to describe the food's exceptional adjective.

Three interpretations are listed for the word «有味儿 yǒu wèi er « in the 汉语词典online dictation:

1) Which translates to «delicious» conveys the superiority of food's flavor. 这菜真有味, 我爱吃- This cuisine is delicious, and I enjoy eating it.

2) Smelly: This adjective refers to food items that have an unpleasant odor. It is frequently used to describe food that is stale, bitter, or nauseating: 饭有味了, 吃了会闹肚子的. - I felt sick after consuming the food because it was a little bitter.

3) When the word «surprising» is translated, it refers to the novelty and fascination of the objects:

这幅小品画很有味儿。— This tiny image is really lovely.

In all three instances, the word 有味儿 yǒu wèi er can be translated verbally as «delicious» to describe the flavor of the first dinner. We can see that the translation is used using the functional equivalent technique because «awesome» has no meaning.

Additionally, because it can mean things like sour or smelly when used to describe Chinese cuisine, the word «有味儿 yǒu wèi « is less frequently used in a positive context.

It is clear from the sentence 佳兵者不祥that the illustrious Chinese philosopher Laozi used this term to refer to a handsome soldier. The student used the word-for-word translation technique, according to the analysis presented above, because the definition of food does not imply that it is wonderful.

Twelve students mistranslated the «肴 yáo» adjective, which refers to «food with great taste» as the word «肴 yáo» because, according to the Chinese online dictionary, «肴 yáo» is a noun. The term «z» describes goods like prepared beef and meat dishes. In Sima Guang's «Taste Economy and Health Index» for instance, 肴止于脯、醢、菜羹 (肴, 下酒的菜) the term «delicacy» is used to describe dried meat, glutinous rice, and veggie broth. It was established from this example and the provided definition that the word 肴 yáo was a translation error and was not used to mean wonderful.

When translating the meaning of excellent taste, one student used the Chinese phrase 有闻精彩 yǒu wén jīngcǎi。 The phrase 有闻 yǒu wén which is part of the compound, denotes hearing. 精彩 jīngcǎi is a term that belongs to the adjective word family and is used to describe speeches, performances, exhibitions, and articles in the sense of being superb, wonderful, or in some ways exceeding expectations.

Despite having a beautiful meaning when translated from Uzbek to Chinese, the word «精彩 jīngcǎi» only has a restricted range of uses and 精彩 jīngcǎi cannot be used to describe the flavor, appearance, or shape of food.

精彩 jīngcǎi interference incident, a student studying a foreign language made a grammatical error. As a consequence, this word was used as a function of 精彩 jīngcǎi. As evidence for our assertion, 《文选·宋玉》:目略微盼,精彩相授。 李善 注:精神光采相授与也 is the Song Yu's Selected Works, p. «Bring Spiritual Brilliance to Each Other» according to Li Shan's Note, and «Looking Forward a Little, We Gave Each Other a Wonderful Gift» 精彩 jīngcǎi which means «gift» is meant to be bright, beautiful. It has evolved to take on the connotations of a spiritual radiance, as is evident.

The word-for-word translation technique was applied by 16 students味道好 wèidào hào. Firstly, it translates to «Tastes good» in Uzbek, according to our analysis. The excellent adjectives translation was in high demand. If 好hǎo is translated as having a high adjective, it cannot be used to mean an excellent adjective.

The Chinese online lexicon defines the adjective 美味 měiwèi as having a sweet, delectable, or pleasant taste. The definitions of sweet and delicious are expressed in the following sentences:

瞧瞧那些看起来很美味的西红柿。- Those tomatoes are much better than they appear, you see.

美味的黑巧克力味女人无法抗拒。- Women are powerless against delicious, dark chocolate.

10 students used the adjective 美味 měiwèi to give the meaning of great taste in the translation, but according to the analysis, the adjective 美味 měiwèi only has the meaning of sweet and delicious, and during the translation process, the students translated by the method of lexical-semantic equivalence. Following are the findings of the outstanding adjective translation analysis:

| № |

Delicious (taste) |

The type of translation |

Result |

| 1. |

鲜美的xiānměi de |

Equivalent translation |

17 students translated correctly |

| 2. |

味道好吃 wèidào hào chī |

Lexical-semantic equivalent |

Used by 2 students |

| 3. |

有味儿 yǒu wèi er |

Functionally equivalent |

Used by 1 student |

| 4. |

佳 jiā |

Literal translation |

Used by 12 students |

| 5. |

美味 měiwèi |

Lexical-semantic translation |

Used by 10 students |

| 6. |

肴yáo |

Translation error |

Used by 1 student |

| 7. |

精彩jīngcǎi |

Functional translation |

Used by 1 student |

| 8. |

味道好wèidào hào |

Lexical-semantic translation |

Used by 16 students |

7. Discussion

In Chinese, there are five main categories of taste adjectives: pungent, bitter, sweet, sour, and salty, which describe tastes such as sweet-salty, bitter-sour, and sour-sweet. Because has been stated, there are cases where adjectives or words expressing taste are missing or not completely translated during the translation process into other languages. It is critical to understand the categories of quality and taste in Chinese cuisine when translating from Chinese to Uzbek. To do so, the translator must have a thorough understanding of the original language and culture. The variety of flavors in Chinese cuisine, primarily bitter, sweet, and salty, creates many difficulties in translating it into the languages of the CIS countries. It is critical to study the original text thoroughly, to use an equivalent translation when translating adjectives related to the category of taste, or to use descriptive translation methods if there is no such category of taste in the language to be translated.

Currently, Chinese language classes in the Republic of Uzbekistan's higher education institutions are designed for foreign students in the PRC, and textbooks published include 标准教程 (HSK 1、2、3、4、5、6)”, “新实用汉语”, “博雅汉语”,“汉语教程”,“发展汉语”,“成功之路” and others. Taste adjectives are only mentioned in the text in these textbooks. In the linguistics subjects of «Lexicology» or «Practical and theoretical grammar,» only four hours are allotted for topics related to the adjective word group, and information is presented on 7-8 pages. For example, on pages 50-57 of Chinese scholar DsC S. Hashimova's book (S. Hashimova, 2017) «Grammar of the Chinese language» the topic «Adjective» is discussed. There are only a few words related to HSK level 4 among the 1200 words.

60 students were assigned 10 sentences to translate from Chinese to Uzbek as part of the experiment's analysis. Both the second and third phases of philology are areas of study. Of these adjectives given for translation, 清淡qīngdàn - light (food) adjective was translated in 11% equivalent translation method, 很容易让人报的/ 令人感到饱足的hěn róngyì ràng rén bào de/ lìng rén gǎndào bǎo zú de - nutritious (food) adjective 1%, 鲜美的xiānměi de - delicious (taste) adjective 4% student, 13% of students used the term香 xiāng- (taste) aromatic; «简单jiǎndān» which means «easy (to prepare food)» 2% of students; 热rè - hot (used to describe the adjective of food) 9% of students used; the word «辣là»- bitter 13% of students used; 15% of students use the word酸suān- sour (tasting) adjective;

好吃 hào chī - delicious (meaning «tasty») 15% of the class, 甜tián sweet (taste) character美味儿的měiwèi er – delicious was translated by 3% of students from the original, which was spoken by 14% of the students. According to the analysis, students translate using a basic Chinese-Uzbek dictionary throughout the class;

好吃 hào chī - delicious (meaning «tasty») 15% of the class, 甜tián sweet (taste) character美味儿的měiwèi er – delicious was translated by 3% of students from the original, which was spoken by 14% of the students. According to the analysis, students translate using a basic Chinese-Uzbek dictionary throughout the class.

8. Conclusion

Additionally, the textbooks provided to students learning Chinese do not contain lexical-semantic analyses of every word. Students make mistakes about where to use synonyms due to the interference effect. Of course, it is normal for a person learning a new language to experience interference in their speech. However, students specializing in translation and philology must be able to use words properly in conversation and during the translation process. The absence of Chinese-Uzbek or Uzbek-Chinese dictionaries, descriptive translations of many adjectives with the feature of synonymy, or dictionaries linked to food discourse suggests that thorough scientific study should be done in this area. The conclusion is that Uzbek students and Chinese language learners will benefit greatly from the development of an explanatory dictionary of Chinese synonyms and dictionaries of adjectives used in food discourse.

Author Contributions

Gulnoza Odilova and Dilshoda Mamatova conceived of the presented idea. Gulnoza Odilova developed the theory and performed the computations. Dilshoda Mamatova verified the analytical methods. Both authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Amonov U. (2021) “Modern Uzbek literary language” (p 78).

- Cappelen and Hawthorne, (2009) from Relativism and Monadic Truth.

- Herman Cappelen & John Hawthorne Oxford, GB: Oxford University Press UK.

- Cohen, 1999 from What qualitative research can be Ronald Jay Cohen first Published: 09 June 1999 https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199907)16:4<351::AID-MAR5>3.0.CO;2-S. [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, (1973) from Logics and Languages Max Cresswell London: Methuen, Harper & Row.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2004). Adjective Classes in Typological Perspective. In R. M. W. Dixon, & A. Y. Aikhenvald (Eds.), Adjective Classes: A Cross-Linguistic Typology (pp. 1-49). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fellman Leonard, (1981) from Merchandising by Design: Developing Effective Menus and Wine List S Hardcover – January 1, 1981.

- Gernet Jacques (1962) Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250-1276 1st Edition.

- Heimann, Jim Heller, Steven and Mariani, John (2011) Menus design in America: A Visual and Culinary History of Graphic Styles and Design 1850-1985: Taschen.

- Huddleston and Pullum, (2022) from Rodney Huddleston, Geoffrey K. Pullum and Brett Reynolds, A student's introduction to English grammar, 2nd in Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022. Pp. 400.

- Kholmonova Z. T. (2007) “Modern Uzbek language” (p 123).

- Lasersohn, (2005) from Context-Dependence, Disagreement, and Predicates of Personal Taste Linguistics and Philosophy volume 28, pages 643–686.

- Lewis, (1970) from General semantics David K. Lewis Synthese 22, (P 18—67).

- Lewis, (1979) THE DUAL ECONOMY REVISITED W. ARTHUR LEWIS September 1979 from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9957.1979.tb00625. [CrossRef]

- Lin Hong, (2009) “Linguo-cultural faults and translation practice in the translation of Chinese food into English» from (林红 “中国菜名英译的文化错位与翻译实践” 成都理工大学学报(社会科学版); 第17卷 第1 期,2009 年 3 月 ).

- Mac Farlane (2005) from December 2005 Higher Education Quarterly 59(4):296 – 312 DOI:10.1111/j.1468-2273.2005.00299.x. [CrossRef]

- Montague, 1974 Branching Quantifiers, English and Montague Grammar. D. M. Gabbay & J. M. E. Moravcsik, Theoretical Linguistics (140—157).

- Odilova G.K., 2021 DsC dissertation.

- Olyanich, (2014) from Discursive Actualization of Ethno-Linguocultural Code in English Gluttony, Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta Serija 2 Jazykoznanije 23(4):70-83 DOI:10.15688/jvolsu2.2014.4.8. [CrossRef]

- Sayfullayeva R.R., Mengliyev B.R., Boqiyev G.H., Qurbonova M.M., Yunusova Z.Q., Abuzalova M.Q. (2009) “Modern Uzbek literary language” (P 237).

- Unger, (1975) Ignorance: A Case for Scepticism Peter K. Unger Oxford University Press (323 pages).

- Wheeler, (1972) Wheeler, G. C.; Wheeler, J. 1972a. The subfamilies of Formicidae. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington.

- Xiong Xin, (2013) from 熊欣 “跨文化交际理论下的中国菜名英译研究” PhD dissertation, (202 p).

- Yu Zhang, Jiaying Fang (2020) from IETI, SSH, 2020, Volume 10. http://paper.ieti.net/ssh/index.html. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.6896/IETITSSH.202011_10.0002. P 12-20. [CrossRef]

- S. Khashimova, (2017) Chinese grammar/. - Tashkent: “Extremum- Press” (P-176).

- 陶然,良岳中,张志东 (1995) 现代汉语形容词辞典。- 中国国际广播出版社,1995 年。-北京,页175.

- Derjavetskaya I.A. (2013) Glutonic vocabulary and problems of its translation / I. A. Derzhavetskaya // Scientific notes of the Tauride National University. V. I. Vernadsky. Series “Philology. Social Communications". - 2013. - P. 466-470.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).