Preprint

Article

E-commerce Adoption in Morocco: Key Factors and Growth Strategies

Altmetrics

Downloads

1310

Views

274

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

15 May 2023

Posted:

16 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

E-commerce is a rapidly evolving global trend that is having a significant impact on consumer behavior and business strategies. Despite its growing impact, e-commerce adoption by Moroccan firms remains low and research on this topic in this context is scarce. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the main determinants influencing e-commerce adoption by Moroccan firms. We use logit, probit, and conditional mixed process-probit models to identify the critical factors driving e-commerce adoption. Our results reveal five key findings. First, newer firms that are more open to innovation and change are more likely to adopt e-commerce. Second, firms with a higher proportion of highly educated employees are more likely to adopt e-commerce. Third, the digital skills of new employees do not directly influence the likelihood of e-commerce adoption. Fourth, being listed on digital platforms increases the likelihood of e-commerce adoption. Finally, there is a positive relationship between firms engaged in innovation activities and e-commerce adoption. These findings highlight the need for additional investment in promoting modern organizational practices, reskilling workers, and implementing advanced technologies to facilitate effective e-commerce integration among Moroccan SMEs. By addressing these challenges, Moroccan firms can harness the full potential of e-commerce and contribute to the country’s economic growth and digital transformation.

Keywords:

Subject: Business, Economics and Management - Business and Management

1. Introduction

This paper examines the adoption of e-commerce by Moroccan firms, a topic that has received little attention in the existing literature despite the high potential of e-commerce. The adoption of e-commerce by Moroccan firms remains remarkably slow, and academic research focusing specifically on the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and Morocco in particular, is surprisingly sparse. A main reason for this paucity of research is the lack of surveys that specifically ask about the determinants of the adoption of e-commerce activities. This paper fills this gap by using data from the recent Economic Resilience Fund (Economic Research Forum - ERF) survey, which provides a rich source of information on this aspect, thereby enhancing our understanding of e-commerce adoption in Morocco.

The diffusion of digital technologies since the early 1990s has revolutionized societies around the world. These digital technologies, recognized as General Purpose Technologies (GPTs) (GPTs are defined as “a single generic technology, recognizable as such over its whole lifetime, that initially has much scope for improvement and eventually comes to be widely used, to have many uses, and to have many spillover effects” [1] (p. 98)), have the capacity to significantly impact economies and societies worldwide if properly applied and managed. They offer potential solutions to many economic, social, and environmental challenges [2]. GPTs are designed for multipurpose use rather than single or singular applications. The economic and societal implications of the digital revolution are the subject of intense debate among politicians, economists, and business leaders. Digital transformation refers to a process that enables substantial improvements through a synergy of information, computation, communication, and network technologies [3].

Since the 1990s, we have witnessed successive waves of complementary digital technologies, each with greater transformative potential than its predecessor. These include artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), robotics, 3D printing, and virtual and augmented reality. Their profound impact is being felt across all sectors of the economy. They have revolutionized manual tasks, automated services, and employment in the manufacturing sector, increasing productivity and market competitiveness. However, these benefits require a highly skilled workforce and significant changes in business models.

In theory, digital transformation could enable developing countries to leapfrog technologically and developmentally. In reality, however, the digital dividend is conditional. Given their different economic landscapes and varying access to technology, developing countries may experience a different trajectory of the Fourth Industrial Revolution than developed countries. These differences are attributed to industry maturity, technology adoption, skills availability, human resources, and political governance. Nevertheless, the prevailing view strongly supports the notion that digital transformation will yield significant overall benefits. According to the ITU [4], projected outcomes indicate that a mere 10 percent increase in mobile broadband access has the potential to generate an average GDP growth of 1.5 percent. In the African context, this increase could be even greater, reaching up to 2.5 percent.

Despite the widespread penetration of digitalization in societies, its productive and economic applications remain limited in Africa, which may explain the lack of substantial economic value creation and growth. Studying the diffusion of e-commerce among firms and its determinants can provide valuable insights into the impact of digitalization on economic performance.

Digital technologies have paved the way for online buying and selling, commonly known as e-commerce or electronic commerce. [5], in one of the earliest studies of e-commerce, defined it as “the sharing of business information, maintaining business relationships, and conducting business transactions through telecommunication networks”. However, this broad definition has since evolved and e-commerce is now understood as the use of the Internet to buy and sell products and services [6,7]. [8] suggest that e-commerce is catalyzing a new era in marketing by converging with traditional commerce and providing opportunities to identify and understand customers and their needs in an expanded context. Encompassing both domestic and international markets, e-commerce is revolutionizing business and marketing practices across sectors.

E-commerce has the potential to be a significant driver of economic growth in developing countries by supporting international value chains, enhancing market access, improving market efficiency, and reducing operating costs [9,10,11]. Developing countries can benefit from adopting e-commerce by leveraging competitive advantages that do not exist in the “traditional economy”, which is characterized by inefficient marketing and export channels dominated by multiple offline intermediaries. In particular, e-commerce can spur growth in developing countries by improving the transparency and efficiency of market operations and public institutions, ultimately fostering a more robust and sustainable economic landscape.

However, the uptake of e-commerce in African countries has lagged behind that of China and India, with less consistent growth, higher transaction costs, and limited demand. In Morocco, the state of e-commerce is still relatively underdeveloped, as indicated by its ranking of 95 out of 152 countries in the UNCTAD B2C E-commerce Index. Moreover, the proportion of Internet shoppers compared to Internet users stands at 22%, while the figure for the overall population is 14.2% [12]. The Moroccan national telecommunications regulatory agency [13] reports that online purchases by Moroccan businesses represent about 8.4% of total purchases, with 95% of cases representing only 4% of total purchases. This underperformance could be attributed to a lack of confidence in legal guarantees and the limited use of online payment solutions.

By addressing these challenges, Morocco can harness the transformative potential of e-commerce and digital technologies to drive economic growth, improve market efficiency, and enhance global competitiveness. Through this research, we contribute to the scarce literature on e-commerce adoption in Morocco and provide valuable insights for businesses, policymakers, and other stakeholders to promote e-commerce integration and reap its benefits.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 1 examines digitalization trends in Morocco; Section 2 reviews relevant literature; Section 3 discusses digitalization and e-commerce in Morocco; Section 4 outlines the methodology and estimation strategy; Section 5 presents results and discusses the findings; and Section 6 concludes with policy implications.

2. Literature Review

Over the past two decades, e-commerce research has expanded considerably. For the most part, e-commerce studies are based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), or the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) [14,15,16,17]. However, UTAUT is used less frequently than other theories due to its more recent introduction in 2003 and the development of UTAUT2 in 2012.

Despite the extensive literature on e-commerce adoption, it is primarily focused on developed countries [18,19,20] and large firms. E-commerce has the potential to increase efficiency and productivity in various sectors, but there is skepticism about its applicability to developing countries. Using data from 107 countries, [21] apply partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling and show that mobile infrastructure and affordable mobile devices do not positively affect e-commerce use.

[8] argue that the slow adoption of e-commerce in developing countries is due to inadequate infrastructure, poor socioeconomic conditions, and the lack of a national strategy, which prevents these countries from reaping the benefits of e-commerce. [8] assert that understanding the adoption and diffusion of e-commerce in developing countries requires consideration of cultural factors.

In developing countries, e-commerce is seen as an innovation. [22] identify security and privacy concerns, limited knowledge and understanding of e-commerce, and high maintenance costs as the main barriers to e-commerce adoption by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Iran, Malaysia, and India. [23] examine the impact of national culture on the relationship between privacy and e-commerce adoption in Trinidad and Tobago. They argue that individual privacy concerns and societal acceptance of e-commerce are influenced by cultural values, regardless of technological and economic infrastructure. Their study also highlights the importance of Internet security awareness, e-commerce acceptance, privacy, and personal interests in determining the intention to use online transactions.

Technology is the primary driver of e-commerce use and product accessibility [24]. Inadequate technological infrastructure in developing countries hinders technology diffusion [25]. [26] attributes the lack of technological innovation in developing countries to high licensing costs.

The shift to online shopping depends on technology awareness. [27] conclude that technological barriers hinder e-commerce in less developed countries. The study by [10] supports this view, claiming that infrastructure is a major barrier to e-commerce adoption in developing countries and that access to technology is the most important infrastructural barrier.

E-commerce offers numerous benefits to both consumers and businesses. For consumers, it expands product choices, enables shopping anytime, anywhere, and allows for product customization [28]. Organizations benefit through increased sales, operational efficiency, employee productivity, reduced costs, improved customer/supplier relationships, enhanced competitive advantage, and increased financial returns [28,29].

[8] show that e-commerce adoption in underdeveloped countries faces infrastructural challenges, including access to technology, connectivity, internet access, secure online transactions, presence of medium and large firms, a robust legal system, and adequate telecommunications infrastructure. In developed countries, the adoption of e-commerce is influenced by the quality and affordability of internet connectivity, telecommunication services, and reliable electricity supply [30].

Some studies identify employment type as a variable affecting e-commerce adoption. [31] found that online shoppers are wealthier than those who shop in physical stores. The ability of e-commerce to increase welfare depends on various factors, including trust and payment methods, which are crucial for e-commerce adoption in African countries [32].

[33] identified barriers to e-commerce in Iran, such as lack of awareness of its benefits and organizational issues related to its implementation. [34] conducted a qualitative study on factors influencing the adoption of e-commerce by SMEs in Algeria and found that electronic payment methods, banking readiness, legal protection, awareness of e-commerce benefits, and risk concerns were the main barriers.

Research on the MENA region is limited. [35] highlighted the importance of innovation and e-commerce models. This study emphasizes the role of government support, investment, and opportunities in promoting e-commerce growth and technology adoption in the United Arab Emirates. [36] conducted a study on Tunisian students and found that while internet use is widespread, the adoption of e-commerce needs to be encouraged.

In Morocco, research on e-commerce adoption is scarce. [37] examined the main factors hindering the adoption of e-commerce solutions by cooperatives in the Agadir region. Their conceptual model, based on previous research, used structural equation modeling on a sample of 102 cooperatives. The study found that technical, economic, and external factors hinder the adoption of e-commerce among cooperatives. [38] examined the barriers to e-commerce adoption in Moroccan agricultural cooperatives. The study found that lack of information and low digital literacy were the main barriers. The cooperatives believed that e-commerce would have a positive impact on their brand image and competitiveness, but a minimal impact on the speed of operations. The level of digitalization was found to be positively associated with the perceived impact of e-commerce on business performance. [27] conducted an exploratory investigation on e-commerce adoption among SMEs in Morocco. The study identified technological, financial, cultural, and organizational factors that influence the readiness of SMEs to adopt e-commerce. The findings revealed that financial and technological factors were the most critical, followed by cultural and organizational factors. These insights shed light on the factors shaping e-commerce adoption among SMEs in Morocco and underscore the significance of addressing technological and financial challenges to promote e-commerce adoption in the country.

3. Digitalization in Morocco: Key Developments and Trends

Morocco’s digital landscape has undergone a major transformation since the privatization of its telecommunications infrastructure in the early 1990s and regulatory reforms in the mobile sector, resulting in a significant increase in internet users. By early 2023, the number of Internet users in Morocco had risen to 33.18 million, representing an Internet penetration rate of 88.1%, up from 84% the previous year. In addition, there were 21.30 million active social media users, representing 56.6% of the total population, and 50.19 million active mobile connections, representing 133.3% of the population. Despite these impressive statistics, there remains a disparity in the quality of network access between rural and urban areas. The number of internet users in Morocco increased by 341 thousand (+1.0%) between 2022 and 2023, leaving 4.47 million people, or 11.9% of the population, offline at the beginning of the year [39].

The government’s focus on developing technology parks and industrial zones has attracted significant foreign direct investment (FDI) into the country, enabling the growth of advanced manufacturing industries. This has resulted in the IT sector showing strong growth potential, characterized by a burgeoning number of technology start-ups and innovation hubs. The Moroccan Agency for Digital Development (ADD) has played a key role in fostering the local tech ecosystem by supporting innovative projects [40].

Morocco’s innovation ecosystem is growing rapidly and, according to the Global Innovation Index 2022 [41], the country ranks second in North Africa and 67th globally in terms of competitiveness in new technologies. Since 2012, Morocco has been pursuing a cluster development strategy to boost productivity and innovation. The Innov-Investment Fund and the Mohammed VI Investment Fund further support this growth by offering comprehensive financing and support programs [40].

The rise in internet penetration and mobile connectivity has also fostered a rapid increase in e-commerce adoption in Morocco. By 2021, e-commerce revenues will reach $300 million, representing a growth rate of 40% [39]. This trend has been facilitated by the availability of digital payment options and the government’s introduction of e-payment systems, such as m-wallet.

Government initiatives, such as the Digital Morocco 2020 strategy and the regulatory role of the national telecommunications regulatory agency (ANRT), have been instrumental in shaping Morocco’s digital landscape. These efforts have fostered the growth of the digital economy, the use of e-government services, and the development of digital infrastructure [40].

Despite significant progress in digitalization, Morocco still faces challenges in bridging the digital divide, especially between urban and rural areas. There are also issues related to ensuring affordable internet access for all and addressing the digital skills gap. In response, the government has launched several initiatives, including the National Digital Inclusion Program, which aims to provide affordable Internet access and digital training to disadvantaged populations.

As digitalization grows, so does the need for a robust cybersecurity infrastructure. To address this issue, the government established the National Agency for Cybersecurity (ANAC) in 2017. The agency is responsible for developing a comprehensive cybersecurity strategy and promoting best practices to ensure the security of digital transactions and data.

While these advances mark significant progress in Morocco’s digital landscape, challenges remain in bridging the digital divide between urban and rural areas, ensuring affordable Internet access for all, and addressing the digital skills gap. These challenges underscore the need for further research into the determinants of Moroccan firms’ adoption of online commercial activities.

4. Methodology

When dealing with a qualitative (dichotomous or multiple choice) dependent variable, it is necessary to use an alternative approach to simple or multiple linear regression models. In this case, a binary (dichotomous) model is more appropriate to account for the binary nature of the dependent variable, which indicates the presence or absence of a probabilistic event.

Theoretically, there are three primary models: the probit model, the logit model, and the linear probability model. In practice, the probit and logit models are more commonly used. The error distribution function of the probit model follows a reduced centered normal distribution, while the logit model follows a logistic distribution [42]. These models differ in their distribution functions and the variances of the random deviations. The variance of the random deviations in the normalized probit model is unity (1), while in the logit model it is π2/3 [43].

We start our analysis with the logistic regression model supported by a probit model. This choice is justified by the advantages offered by the logit model, including alternative interpretations of results (e.g., signs of coefficients, marginal effects, and odds ratios) [44] and its ability to assign higher probabilities to “extreme” events compared to the normal distribution [42]. The simple logit regression model can be expressed as:

where EAi is a binary variable with a value of 1 if the firm has adopted an e-commerce system and 0 otherwise. FCi is a dummy variable representing the firm’s technological support for e-commerce adoption, and Xi is a vector of observed characteristics that are expected to influence the firm’s decision to adopt e-commerce. These characteristics include factors such as firm size, age, location, economic sector, digital skills of the workforce, and product innovation.

Previous research underscores the importance of addressing selection bias and endogeneity issues when examining the determinants of digital technology adoption, including e-commerce. E-commerce adoption is not a random firm decision; firms with favorable enabling conditions are more likely to adopt e-commerce. The endogeneity of the facilitating conditions variable could bias our estimates, especially if factors related to the availability of organizational and technical infrastructure also affect e-commerce adoption decisions.

To address these concerns, we will estimate Eq. (1) using the two-stage probit model within the conditional mixed process with heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors (CMP) framework proposed by [45]. This method is commonly used in analyses of the determinants of digital technology adoption and employs a seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) technique to simultaneously estimate the determinants of e-commerce adoption and the facilitating conditions. The CMP model consists of two correlated error equations:

The CMP method consists of a two-stage regression analysis. In the first stage (eq. 3), the instrumental variables related to the explanatory variable are identified and their correlation is evaluated. In the second stage (eq. 2), the exogeneity of the explanatory variable is tested using the endogeneity test parameter (atanhrho_12) by including the instrumental variables in the regression model. If the endogeneity test parameter is significantly different from 0, indicating the presence of an endogeneity problem, the estimation result of the CMP method is more reliable. If the endogeneity test parameter is not significantly different from 0, the basic regression estimation result can be used.

In these equations, Zi represents the instrument (i.e., the availability of computers, websites, and IT staff), Xi is a vector of explanatory variables excluding the instrumental variables, and μi and ωi are the error terms. By estimating these equations, we aim to obtain more consistent estimates of the determinants of e-commerce adoption by Moroccan firms.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

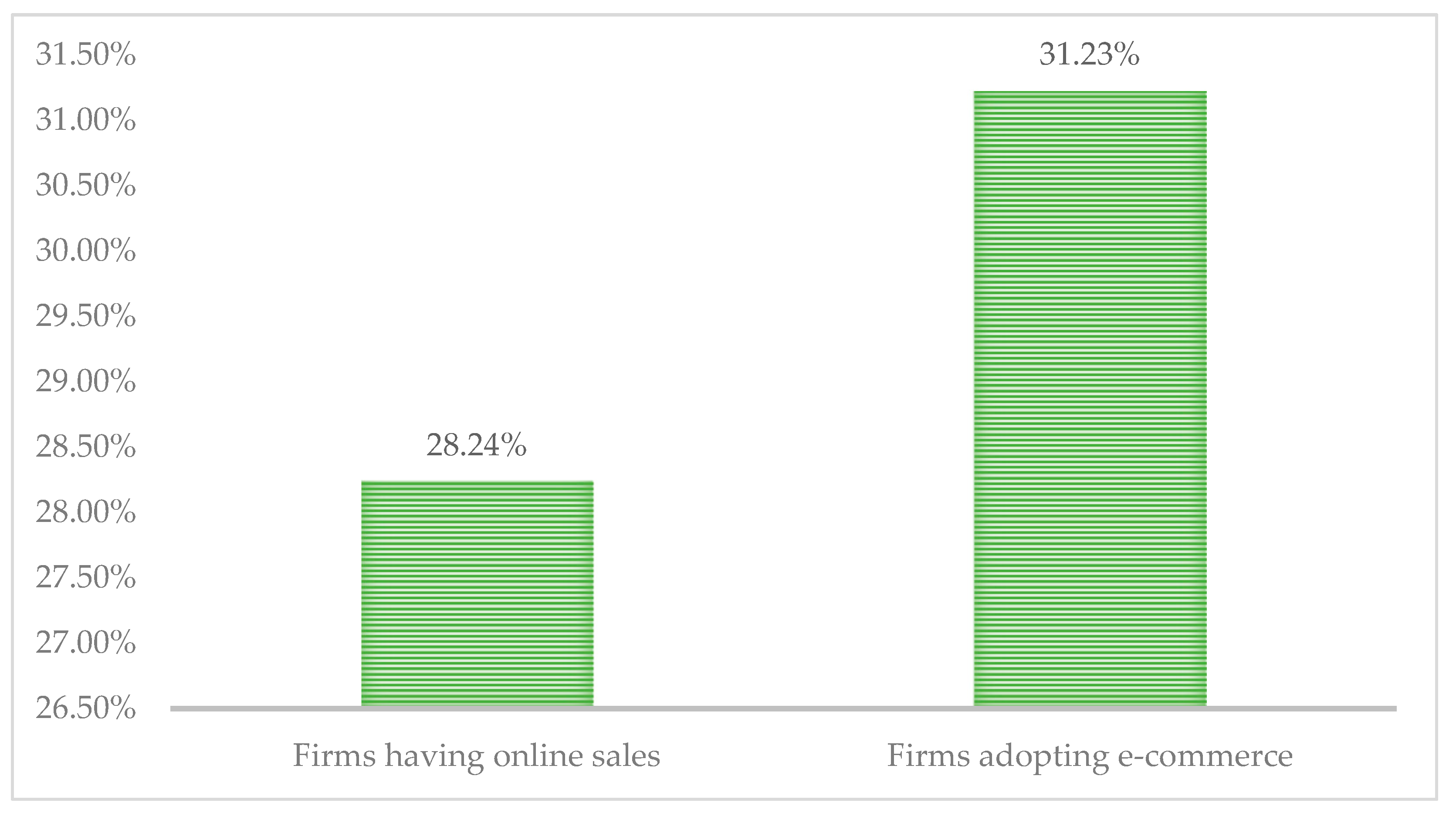

Primary data were collected in July 2022 from 807 firms in Morocco. Table 1 and Table 2 present descriptive statistics for the qualitative variables. They show that less than a third of the surveyed firms have adopted e-commerce (31.23%), as measured by the proportion of firms that buy and/or sell online (see Figure 1). Moreover, 79.80% of the companies have less than 15 employees. In terms of firm age, 25.99% of the sample are young firms (less than 5 years old) and 36.58 have been in the market between 6 and 10 years. Table 1 and Table 2 also show that 20.06% of the firms are between 11 and 15 years old and only 17.37% of the firms are older than 15 years.

The descriptive analysis shows that 44.24% of the surveyed firms are located in the Casablanca-Settat region, 14.75% in the Rabat-Salé-Kénitra region, 10.66% in the Marrakech-Safi region, 9.67% in the Fez-Meknes region and 8.05% in the Tangier-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region. These five regions represent 87.37% of the sampled firms. The largest sector is “accommodation and food services” (21.81%), followed by “retail or wholesale or services of motor vehicles” (19.58%). The least represented industries are “chemicals and chemical products” and “petroleum products, plastics and rubber”, with 0.99% and 0.5%, respectively. In terms of higher education (university degree), 32.71% of the enterprises in the sample have less than 25% of their workforce with a university degree, while only 17.35% of the enterprises have more than 75% of their workforce with a university degree. Most enterprises (80.79%) are managed or owned by men. In the sample, 48.94% have an information technology infrastructure to support sales and customer service activities, 55.90% and 48.74% use social media and smartphones, respectively, for business purposes, 68.65% have a website, 46.70% have internet access, 5.57% do not use computers for business purposes, 40.52% are engaged in product innovation activities, and 7.81% are listed on digital platforms. Finally, 60.15% of the sample did not consider digital skills to be a requirement for employment in their organization.

5.2. Estimation Results

Table 3 presents the estimates of the determinants of e-commerce adoption using logit, probit, and conditional mixed process probit models. As these are binary models, the coefficients cannot be interpreted directly. Instead, the signs of these coefficients indicate whether the associated variables have a positive or negative effect on the probability of adopting e-commerce. To measure the sensitivity of the probability of adopting e-commerce in the logit model, we use the odds ratio.

The CMP estimation approach of [45] also accounts for endogeneity due to self-selection bias. The statistic atanhrho_12, reported at the bottom of the table, measures the covariance of the error terms in the two equations used. Its negative significance indicates that some unobserved factors negatively affect both the outcome variable (e-commerce adoption) and the endogenous variables (facilitating conditions); however, these factors are considered in the estimation.

Examining the coefficients and odds ratios, their probabilities and pseudo-R2 values, we find that most of the variables explain the probability of adopting e-commerce. In Morocco, the age of the firm, the location of the firm in the Oriental, Casablanca-Settat or Souss-Massa regions, and having between 51% and 75% of employees with higher education all contribute to this probability. In addition, management’s level of digital skills, facilitating conditions, the use of social media for business purposes, the use of digital platforms, product innovation, and the use of smartphones for business purposes significantly affect a firm’s likelihood of adopting e-commerce. However, firm size, the proportion of female employees, female managers or owners, and the level of digital skills of employees do not affect the probability of adopting e-commerce in Morocco.

Regarding the activity sectors of our sample firms, our results show that firms in “basic metals, metal products, wood products, furniture, paper and publishing”, “education”, and “health” are 21.79, 33.40, and 15.24 times more likely to adopt e-commerce, respectively.

The age of the firm seems to be crucial for the adoption of e-commerce, as evidenced by its negative and significant coefficient in all models. The odds ratio values in the logit model suggest that in Morocco, newer firms are more likely to adopt e-commerce. Firms aged 11-15 years and those older than 15 years are 0.46 and 0.26 times less likely to adopt e-commerce, respectively, than firms younger than five years. This can be explained by the fact that younger firms are more likely to adopt technological innovations, while older firms may have more traditional attitudes and be more resistant to change. Older firms may also face greater difficulties in adopting e-commerce due to limitations in adopting new technologies. This result is consistent with the findings of [25,46,47].

In terms of firm location, we find that firms located in the Oriental, Casablanca-Settat, and Souss-Massa regions are less likely to adopt e-commerce than firms located in the Tangier-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region. No other location factor contributes to explaining e-commerce adoption in Morocco. Our results are consistent with [38] and suggest that barriers to e-commerce adoption in the Rabat-Salé-Kenitra, Fes-Meknes, Rabat-Salé-Kenitra, and Beni Mellal-Khenifra regions include Internet access, lack of information, and cost of technology.

Regarding the gender of owners, managers, and employees, these variables do not affect the adoption of e-commerce in Morocco. Similarly, firm size does not affect the likelihood of e-commerce adoption, as its coefficients are statistically insignificant.

Regarding the educational level of employees, the results show that having a significant proportion of employees with university degrees positively affects the likelihood of adopting e-commerce in Morocco. Firms with 51-75% of their employees having a university degree are 2.96 times more likely to adopt e-commerce. This is because the use of technologies related to e-commerce requires a certain level of cognitive and technological skills. This result supports the findings of studies by [48,49,50].

Moreover, the results indicate that the level of digital skills required for new hires has an insignificant statistical effect on the probability of e-commerce adoption by Moroccan firms. It appears that e-commerce adoption depends on the level of digital skills of employees. Limited digital cognitive skills may limit the use of ICTs required for e-commerce activities to rudimentary uses without added value, revealing the low importance given to e-commerce among all digital technologies.

The importance of digital skills in managerial staffing decisions is statistically significant at the 10% level and affects the willingness to adopt e-commerce, with an odds ratio value of 0.60. This suggests that firms are not aware of the impact of digital skills on e-commerce adoption decisions, which is consistent with the findings of [47,51].

The positive coefficient of facilitating conditions in all models highlights the importance of having the necessary organizational and technical infrastructure to support the use of technology or systems to increase the likelihood of e-commerce adoption by firms. Based on the results of the logit estimation, the odds ratio calculation shows that the availability of organizational and technical infrastructure to support the use of systems increases the probability of e-commerce adoption by 1.68 times.

Our results also show that being listed on an app, website, or digital platform such as Amazon or Jumia increases the likelihood of e-commerce adoption. This underscores the importance of being part of an online commerce network, as it increases the likelihood of e-commerce adoption by 2.57 times. This is expected as these digital platforms offer extensive resources to help users maximize their experience and provide detailed guides and tutorials. The large user base of these platforms makes them an ideal choice for firms looking to engage in e-commerce.

The logit model shows that the probability of e-commerce adoption increases significantly (at the 1% level) with employees’ use of social media and smartphones for business purposes. The odds ratios of these two variables indicate that the probability of adoption increases by a factor of 3.22 and 3.41, respectively. This result is consistent with the literature [29,45,53].

Finally, engaging in product innovation activities has a positive impact on the probability of adoption, with statistical significance at the 1% level in all models. Firms that introduce new products/services or implement production process innovations experience a 1.83-fold increase in the probability of e-commerce adoption.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This paper has attempted to analyze the adoption of e-commerce by firms in Morocco. Using logit, probit, and CMP models, we identified the main factors influencing the adoption of e-commerce by Moroccan firms. Although digitalization is progressing in Morocco, the adoption of e-commerce remains low. Most firms do not prioritize e-commerce development, and there is a lack of skills required for e-commerce adoption in Moroccan firms.

This paper presents five main findings. First, firm age is an important indicator of e-commerce adoption, with younger firms more likely to adopt e-commerce due to their openness to innovation and change. Second, e-commerce adoption depends on the level of education, and firms with a higher proportion of educated employees are more likely to adopt e-commerce. Third, the level of digital skills required of new recruits does not affect the likelihood of adopting e-commerce, suggesting that Moroccan firms place a low priority on adopting e-commerce and believe that digital skills are not a prerequisite for recruitment. Fourth, being listed on a digital platform increases the likelihood of adopting e-commerce. Fifth, innovation activities and the introduction of new products and services influence e-commerce adoption in Moroccan firms.

Based on these findings, we propose the following recommendations to promote e-commerce adoption among Moroccan firms.

First, Moroccan firms should change their business strategy to exploit the potential of new technologies and shift to online. E-commerce requires a certain level of digitization, which makes the Internet and digital technologies crucial for effective e-commerce adoption.

Second, firms should have an online consumer retention strategy. Many consumers prefer to buy online because e-commerce helps them save time, in addition to several other benefits. The adoption of e-commerce could increase customer and sales volumes.

Third, it is important to train employees and teach them the skills required to use e-commerce. Equipping employees with digital skills is crucial for the good functioning of e-commerce.

Fourth, firms should seek a digital platform listing and explore new ways to leverage the online market. Digital platforms are affecting daily life and listing on an e-commerce digital platform provides many benefits, including reaching more consumers and increasing visibility.

Fifth, firms should offer more innovative products and services online to increase the market and use of e-commerce.

By implementing these recommendations, Moroccan firms can better exploit the potential of e-commerce and reap its many benefits, such as increased market reach, improved customer satisfaction, and higher sales.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.Y. and M.D.; methodology, A.B.Y. and M.D.; formal analysis, A.B.Y. and M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.Y. and M.D.; writing—review and editing, A.B.Y. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available at the ERF Data Portal, accessible at http://www.erfdataportal.com/index.php/catalog/250.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lipsey, R.; Carlaw, K.; Bekar, C. Economic Transformations: General Purpose Technologies and Long-Term Economic Growth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Youssef, A. How Can Industry 4. 0 Contribute to Combatting Climate Change? Revue d’Économie Industrielle 2020, 169, 161–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial. Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access. Broadband Commission Working Group on Smartphone Access. 2022. Available at: https://www.broadbandcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2022/09/Strategies-Towards-Universal-Smartphone-Access-Report-.pdf (accessed March 17, 2023).

- Vladimir, Z. Electronic Commerce: Structures and Issues. Int. J. Electron. Commerce 1996, 1, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.; Kraemer, K.L.; Dedrick, J. Environment and Policy Factors Shaping Global E-Commerce Diffusion: A Cross-Country Comparison. Inf. Soc. 2003, 19, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandon, E.E.; Pearson, J.M. Electronic Commerce Adoption: An Empirical Study of Small and Medium US Businesses. Inf. Manage. 2004, 42, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Goyal, K.; Chauhan, A. Emerging Trends of E-Commerce Perspective in Developing Countries. J. Posit. School 2022, 6, 7090–7096. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, J.; Mansell, R.; Paré, D.; Schmitz, H. E-commerce for Developing Countries: Expectations and Reality. IDS Bull. 2004, 35, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.E.; Tar, U.A. Barriers to e-commerce in developing countries. Inf. Soc. Justice J. 2010, 3, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Information Economy Report 2015: Unlocking the Potential of E-Commerce for Developing Countries; United Nations: New York and Geneva, 2015.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). UNCTAD B2C E-commerce Index 2020: Spotlight on Latin America and the Caribbean - UNCTAD Technical Notes on ICT for Development No. 17. United Nations, 2021.

- Agence Nationale de Règlementation des Télécommunications (ANRT). Observatoire de la Téléphonie Mobile au Maroc: Situation Fin Décembre 2020; ANRT: Rabat, Morocco, 2020; 7 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Yi, S. The Effects of Extend Compatibility and Use Context on NFC Mobile Payment Adoption Intention. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: 2016; pp 57–68. [CrossRef]

- Tomić, N.; Kalinić, Z.; Todorović, V. Using the UTAUT model to analyze user intention to accept electronic payment systems in Serbia. Port Econ J 2023, 22, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M.; Nadzar, F.; Rahman, B.A. Examining user Acceptance of E-Syariah Portal Among Syariah users in Malaysia. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 67, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YenYuen, Y.; Yeow, P.H.P. User Acceptance of Internet Banking Service in Malaysia. In Web Information Systems and Technologies; Springer: 2009; pp 295–306. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, W.; Hussain, A.; Farhat, K.; Arif, I. Underlying Factors Influencing Consumers’ Trust and Loyalty in E-commerce. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2019, 8, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Hashimoto, M. Changes in consumer dynamics on general e-commerce platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploratory study of the Japanese market. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze Schwering, D.; Isabell Sonntag, W.; Kühl, S. Agricultural E-commerce: Attitude segmentation of farmers. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 197, 106942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, M.D.; Adam, I.O. The Effect of Mobile Phone Penetration on E-commerce Diffusion: A Global Perspective Using Structural Equation Modelling. Int. J. Bus. Syst. Res. 2022, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.A.; Zhang, S.X.; Brem, A. E-commerce for SMEs: empirical insights from three countries. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2013, 20, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Z.A.; Tejay, G.P. Examining privacy concerns and e-commerce adoption in developing countries: The impact of culture in shaping individuals’ perceptions toward technology. Comput. Secur. 2017, 67, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhi, M.I. The Role of Technology, Government, Law, And Social Trust on E-Commerce Adoption. J. Global Inf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 25, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornkitvikai, Y.; Tham, S.Y.; Harvie, C.; Buachoom, W.W. Barriers and Factors Affecting the E-Commerce Sustainability of Thai Micro-, Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises (MSMEs). Sustainability 2022, 14, 8476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, B. The Technology Cycle and Inequality. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2009, 76, 707–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahbi, S.; Benmoussa, C. What Hinder SMEs from Adopting E-commerce? A Multiple Case Analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 158, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Sharma, V.; Kapoor, R. Study of E-Commerce and Impact of Machine Learning in E-Commerce. Adv. Electron. Commerce 2022, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, R.; Day, J. E-commerce adoption by SMEs in developing countries: evidence from Indonesia. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2016, 7, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, R.; Day, J. Determinant Factors of E-commerce Adoption by SMEs in Developing Country: Evidence from Indonesia. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Soza-Parra, J.; Circella, G. The increase in online shopping during COVID-19: Who is responsible, will it last, and what does it mean for cities? Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2022, 14, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amofah, D.O.; Chai, J. Sustaining Consumer E-Commerce Adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Trust and Payment Method Matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N.; Sims, J.; Shanmugam, M. A practical model for e-commerce adoption in Iran. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2014, 27, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, H.; Binti Abd Rahima, N.H.; Mohamed Razi, M.J.; Shah, A. Factors Influencing the adoption of e-commerce by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) in Algeria: a qualitative study. Int. J. Percept. Cogn. Comput. 2020, 6, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccia, A.; Le Roux, C.L.; Pandey, V. Innovation and E-Commerce Models, the Technology Catalysts for Sustainable Development: The Emirate of Dubai Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebei, M. Diffusion du commerce électronique en Tunisie : une analyse et modélisation des comportements d’adoption de l’internet et des services marchands par les jeunes. Economies et Finances. Université Côte d’Azur; Institut supérieur de gestion (Tunis), 2018.

- Bighrissen, B. A Study of Barriers to E-Commerce Adoption Among Cooperatives in Morocco. Lect. Notes Networks Syst. 2022, 557, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbouri, I.; Jabbouri, R.; Bahoum, K.; El hajjaji, Y. E-commerce adoption among Moroccan agricultural cooperatives: Between structural challenges and immense business performance potential. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2022, 00, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datareportal. Digital 2023: Morocco. 2023. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-morocco (accessed February 12, 2023).

- U.S. Department of Commerce. Morocco: Telecommunications. 2022. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/morocco-telecommunications (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Global Innovation Index 2022. 2022. Available at: https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_2000_2022/ma.pdf (accessed February 12, 2023).

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, Global Edition, 8th ed.; Pearson, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Amemiya, T. Advanced Econometrics; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, D.A. Randomization Does Not Justify Logistic Regression. Stat. Sci. 2008, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. Fitting Fully Observed Recursive Mixed-process Models with CMP. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2011, 11, 159–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, J.; Chellasamy, A.; Singh, B.N.B. Readiness factors for information technology adoption in SMEs: testing an exploratory model in an Indian context. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2019, 13, 694–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.H.; Saffu, K.; Mazurek, M. An Empirical Study of Factors Influencing E-Commerce Adoption/Non-Adoption in Slovakian SMEs. J. Internet Commerce 2016, 15, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualrob, A.A.; Kang, J. The barriers that hinder the adoption of e-commerce by small businesses. Inf. Dev. 2016, 32, 1528–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouk, M.A.; Eraqi, M.I. Perceived barriers to e-commerce adoption in SMEs in developing countries: the case of travel agents in Egypt. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2015, 21, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Min, S.; Ma, W.; Liu, T. The adoption and impact of E-commerce in rural China: Application of an endogenous switching regression model. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 83, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muathe, S.M.A.; Muraguri-Makau, C.W. Entrepreneurial Spirit: Acceptance and Adoption of E-Commerce in the Health Sector in Kenya. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. Works 2020, 7, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Apergis, E. Who is tech savvy? Exploring the adoption of smartphones and tablets: An empirical investigation. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2019, 30, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahliza, F. The Influence of E-commerce Adoption Using Social Media Towards Business Performance of Micro Enterprises. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law 2019, 18, 209–298. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Adoption of e-commerce.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variables | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-commerce adoption | 807 | 0.3123 | 0.4637 | 0 | 1 | |

| Firm size | 807 | 2.1239 | 1.1357 | 1 | 4 | |

| Firm age | 710 | 2.2901 | 1.0369 | 1 | 4 | |

| Firm location | 807 | 5.2577 | 2.0881 | 1 | 12 | |

| Economic sector | 807 | 11.4027 | 4.3189 | 1 | 18 | |

| Highly educated workers | 807 | 2.1958 | 1.0771 | 1 | 4 | |

| Managerial staff digital skills | 517 | 0.7215 | 0.4487 | 0 | 1 | |

| Workers digital skills | 517 | 0.3985 | 0.4901 | 0 | 1 | |

| Facilitating conditions | 517 | 0.4894 | 0.5004 | 0 | 1 | |

| Social media use | 517 | 0.5590 | 0.4970 | 0 | 1 | |

| Women in the workforce | 807 | 1.9455 | 0.8582 | 1 | 4 | |

| Gender of the firm’s owner | 807 | 0.8079 | 0.3942 | 0 | 1 | |

| Digital platform use | 807 | 0.0781 | 0.2684 | 0 | 1 | |

| Product innovation | 807 | 0.4052 | 0.4912 | 0 | 1 | |

| Smartphone use | 517 | 0.4874 | 0.5003 | 0 | 1 |

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of qualitative data.

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| E-commerce adoption | |||

| Non adopters | 555 | 68.77 | 68.77 |

| Adopters | 252 | 31.23 | 100.00 |

| Firm size | |||

| 5 employees or less | 313 | 38.79 | 38.79 |

| 6 to 10 employees | 244 | 30.24 | 69.02 |

| 11 to 15 employees | 87 | 10.78 | 79.80 |

| More than 15 employees | 163 | 20.20 | 100.00 |

| Firm age | |||

| 5 years or less | 184 | 25.99 | 25.99 |

| 6 to 10 years | 259 | 36.58 | 62.57 |

| 11 to 15 years | 142 | 20.06 | 82.63 |

| More than 15 years | 123 | 17.37 | 100.00 |

| Firm location | |||

| Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima | 65 | 8.05 | 8.05 |

| Oriental | 21 | 2.60 | 10.66 |

| Fès-Meknès | 78 | 9.67 | 20.32 |

| Rabat-Salé-Kénitra | 119 | 14.75 | 35.07 |

| Béni Mellal-Khénifra | 15 | 1.86 | 36.93 |

| Casablanca-Settat | 357 | 44.24 | 81.16 |

| Marrakech-Safi | 86 | 10.66 | 91.82 |

| Drâa-Tafilalet | 7 | 0.87 | 92.69 |

| Souss-Massa | 47 | 5.82 | 98.51 |

| Guelmim-Oued Noun | 6 | 0.74 | 99.26 |

| Laayoune-Sakia El Hamra | 4 | 0.50 | 99.75 |

| Eddakhla-Oued Eddahab | 2 | 0.25 | 100.00 |

| Economic sector | |||

| Agriculture, fishing or mining | 12 | 1.49 | 1.49 |

| Textile & Garments | 27 | 3.35 | 4.83 |

| Industry of Food | 39 | 4.83 | 9.67 |

| Industry of mechanics or electronics or Vehicles | 25 | 3.10 | 12.76 |

| Leather Products | 15 | 1.86 | 14.62 |

| Chemicals & Chemical Products | 8 | 0.99 | 15.61 |

| Petroleum products, Plastics & Rubber | 4 | 0.50 | 16.11 |

| Non-Metallic Mineral Products | 15 | 1.86 | 17.97 |

| Basic Metals, Metal Products, Wood Products, Furniture, Paper & Publishing | 53 | 6.57 | 24.54 |

| Construction or utilities | 26 | 3.22 | 27.76 |

| Retail or Wholesale or Services of Motor Vehicles | 158 | 19.58 | 47.34 |

| Transportation and storage | 30 | 3.72 | 51.05 |

| Accommodation and food services | 176 | 21.81 | 72.86 |

| Information and communication or IT | 48 | 5.95 | 78.81 |

| Financial activities or real estate | 30 | 3.72 | 82.53 |

| Education | 40 | 4.96 | 87.48 |

| Health | 55 | 6.82 | 94.30 |

| Other Manufacturing or services | 46 | 5.70 | 100.00 |

| Highly educated workers | |||

| 25% or less | 264 | 32.71 | 32.71 |

| 26% to 50% | 261 | 32.34 | 65.06 |

| 51% to 75% | 142 | 17.60 | 82.65 |

| More than 75% | 140 | 17.35 | 100.00 |

| Women in the workforce | |||

| 25% or less | 281 | 34.82 | 34.82 |

| 26% to 50% | 328 | 40.64 | 75.46 |

| 51% to 75% | 159 | 19.70 | 95.17 |

| More than 75% | 39 | 4.83 | 100.00 |

| Gender of the firm’s owner | |||

| Female | 155 | 19.21 | 19.21 |

| Male | 652 | 80.79 | 100.00 |

| Managerial staff digital skills | |||

| Digital skills not important | 144 | 27.85 | 27.85 |

| Digital skills important | 373 | 72.15 | 100.00 |

| Workers digital skills | |||

| Digital skills not important | 311 | 60.15 | 60.15 |

| Digital skills important | 206 | 39.85 | 100.00 |

| Facilitating conditions | |||

| Not having information technology support | 264 | 51.06 | 51.06 |

| Having information technology support | 253 | 48.94 | 100.00 |

| Social media use | |||

| Don’t use social media for business purposes | 228 | 44.10 | 44.10 |

| Use social media for business purposes | 289 | 55.90 | 100.00 |

| Digital platform use | |||

| Firm not listed on app or website | 744 | 92.19 | 92.19 |

| Firm listed on app or website | 63 | 7.81 | 100.00 |

| Product innovation | |||

| Do not have product innovation activities | 480 | 59.48 | 59.48 |

| Having product innovation activities | 327 | 40.52 | 100.00 |

| Smartphone use | |||

| Not using smartphones for business | 265 | 51.26 | 51.26 |

| Using smartphones for business | 252 | 48.74 | 100.00 |

| Firm’s website | |||

| Do not have a website | 554 | 68.65 | 68.65 |

| Having own website | 253 | 31.35 | 100.00 |

| Having Internet access | |||

| Firm don’t have access to the Internet | 290 | 46.70 | 46.70 |

| Firm have access to the Internet | 331 | 53.30 | 100.00 |

| Using computers for business purposes | |||

| Do not use computers for business purposes | 28 | 5.57 | 5.57 |

| 1-25% of employees | 185 | 36.78 | 42.35 |

| 26 to 50% of employees | 144 | 28.63 | 70.97 |

| 51 to 75% of employees | 40 | 7.95 | 78.93 |

| 76 to 100% of employees | 106 | 21.07 | 100.00 |

Table 3.

Regression results for Logit, Probit, and CMP Models.

| Variable | Logit | Probit | CMP | |

| Coefficient | Odds ratio | |||

| Firm size | ||||

| 5 employees or less | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| 6 to 10 employees | -0.3131 (0.2763) |

0.7311 (0.2020) |

-0.1758 (0.1592) |

-0.2244 (0.1369) |

| 11 to 15 employees | -0.2639 (0.6131) |

0.7681 (0.4709) |

-0.1368 (0.3448) |

-0.3601 (0.3212) |

| More than 15 employees | 0.6493 (1.3377) |

1.9143 (2.5608) |

0.4434 (0.7478) |

0.3265 (0.5790) |

| Firm age | ||||

| 5 years or less | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| 6 to 10 years | -0.5392* (0.3193) |

0.583* (0.186) |

-0.310* (0.185) |

-0.3046* (0.1648) |

| 11 to 15 years | -0.7578** (0.3923) |

0.469** (0.184) |

-0.465** (0.223) |

-0.4077** (0.1927) |

| More than 15 years | -1.3204*** (0.3712) |

0.267*** (0.099) |

-0.792*** (0.217) |

-0.6907*** (0.1991) |

| Firm location | ||||

| Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Oriental | -1.0947 (0.7236) |

0.3347 (0.2422) |

-0.6588 (0.4253) |

-0.5909 (0.4015) |

| Fès-Meknès | -0.7791 (0.5697) |

0.4588 (0.2614) |

-0.4230 (0.3149) |

-0.4135 (0.2617) |

| Rabat-Salé-Kénitra | -0.3110 (0.5284) |

0.7327 (0.3872) |

-0.1709 (0.2993) |

-0.1571 (0.2549) |

| Béni Mellal-Khénifra | -0.0025 (0.7424) |

0.9975 (0.7406) |

0.0480 (0.4569) |

0.0628 (0.4352) |

| Casablanca-Settat | -0.8414* (0.4591) |

0.4311* (0.1979) |

-0.4874* (0.2574) |

-0.4126* (0.2176) |

| Marrakech-Safi | -0.7576 (0.6104) |

0.4688 (0.2862) |

-0.4221 (0.3341) |

-0.3677 (0.2683) |

| Drâa-Tafilalet | -1.0348 (0.9261) |

0.3553 (0.3291) |

-0.5903 (0.5866) |

-0.4661 (0.6078) |

| Souss-Massa | -2.0786*** (0.6422) |

0.1251*** (0.0803) |

-1.2346*** (0.3707) |

-1.1137*** (0.3763) |

| Guelmim-Oued Noun & Laayoune-Sakia El Hamra & Eddakhla-Oued Eddahab | -0.9960 (1.1737) |

0.3694 (0.4335) |

-0.5661 (0.6855) |

-0.6899 (0.5708) |

| Economic sector | ||||

| Agriculture, fishing or mining | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Textile & Garments | 1.9003 (1.3454) |

6.6877 (8.9976) |

1.1098 (0.7593) |

0.5424 (0.6288) |

| Industry of Food | 0.2435 (1.3505) |

1.2757 (1.7228) |

0.0962 (0.7612) |

-0.2422 (0.6273) |

| Industry of mechanics or electronics or Vehicles | 1.4374 (1.3278) |

4.2095 (5.5894) |

0.8003 (0.7563) |

0.3184 (0.5801) |

| Leather Products | 3.2087** (1.4139) |

24.7472** (34.9893) |

1.8567** (0.7945) |

1.3308 (0.6417) |

| Chemicals & Chemical Products | 3.8332** (1.7081) |

46.2104** (78.9341) |

2.2360** (0.9540) |

1.2595 (0.8013) |

| Petroleum products, Plastics & Rubber | 0.9891 (1.7900) |

2.6887 (4.8130) |

0.5428 (1.0922) |

0.2460 (0.9960) |

| Non-Metallic Mineral Products | 2.7625* (1.5892) |

15.8398* (25.1726) |

1.6075* (0.8782) |

0.8570 (0.7077) |

| Basic Metals, Metal Products, Wood Products, Furniture, Paper & Publishing | 3.0818*** (1.3048) |

21.7982*** (28.4412) |

1.8289*** (0.7342) |

1.2329** (0.5878) |

| Construction or utilities | 1.3719 (1.4061) |

3.9427 (5.5438) |

0.8036 (0.7831) |

0.3898 (0.5943) |

| Retail or Wholesale or Services of Motor Vehicles | 2.2189* (1.2376) |

9.1975* (11.3828) |

1.2901* (0.6918) |

0.7551 (0.5235) |

| Transportation and storage | 2.3003* (1.2926) |

9.9774* (12.8963) |

1.3604* (0.7288) |

0.7261 (0.5891) |

| Accommodation and food services | 2.0337* (1.2305) |

7.6421* (9.4036) |

1.1398* (0.6877) |

0.6838 (0.5149) |

| Information and communication or IT | 2.1938* (1.2643) |

8.9693* (11.3396) |

1.3033* (0.7082) |

0.7159 (0.5532) |

| Financial activities or real estate | 1.0778 (1.3484) |

2.9383 (3.9619) |

0.6448 (0.7510) |

0.1513 (0.5564) |

| Education | 3.5088*** (1.3918) |

33.4069*** (46.4970) |

2.0336*** (0.7679) |

1.4422*** (0.5998) |

| Health | 2.7243** (1.3218) |

15.2450** (20.1501) |

1.5953** (0.7341) |

0.9677* (0.5736) |

| Other Manufacturing or services | 2.3431* (1.2736) |

10.4133* (13.2623) |

1.3519* (0.7154) |

0.8359 (0.5611) |

| Highly educated workers | ||||

| 25% or less | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| 26% to 50% | 0.2957 (0.3172) |

1.3441 (0.4264) |

0.1568 (0.1831) |

0.0640 (0.1591) |

| 51% to 75% | 1.0877*** (0.4083) |

2.9675*** (1.2116) |

0.6039*** (0.2310) |

0.3972** (0.1946) |

| more than 75% | 0.1100 (0.4089) |

1.1163 (0.4565) |

0.0481 (0.2302) |

-0.1042 (0.1908) |

| Women in the workforce | ||||

| 25% or less | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| 26% to 50% | -0.0872 (0.2972) |

0.9165 (0.2724) |

-0.0563 (0.1684) |

-0.0419 (0.1394) |

| 51% to 75% | -0.3690 (0.3712) |

0.6914 (0.2566) |

-0.1951 (0.2123) |

-0.1647 (0.1777) |

| more than 75% | 0.0265 (0.6374) |

1.0269 (0.6545) |

-0.0477 (0.3834) |

-0.0385 (0.3227) |

| Gender of the firm’s owner | ||||

| Female | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | |

| Male | 0.4595 (0.3180) |

1.583 (0.504) |

0.2596 (0.1851) |

0.2650 (0.1731) |

| Managerial staff digital skills | ||||

| Digital skills not important | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Digital skills important | 0.4967* (0.3082) |

0.6085* (0.1875) |

0.2897* (0.1755) |

-0.3373** (0.1473) |

| Workers digital skills | ||||

| Digital skills not important | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | |

| Digital skills important | 0.2131 (0.2762) |

1.2375 (0.3418) |

0.1358 (0.1573) |

0.0904 (0.1338) |

| Facilitating conditions | ||||

| Not having IT support | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Having IT support | 0.5235* (0.2975) |

1.6879* (0.5022) |

0.3017* (0.1673) |

1.3709*** (0.2340) |

| Social media use | ||||

| Do not use social media for business purposes | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Use social media for business purposes | 1.1709*** (0.2600) |

3.2248*** (0.8383) |

0.6928*** (0.1500) |

0.5234*** (0.1438) |

| Digital platforms use | ||||

| Firm not listed on app or website | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Firm listed on app or website | 0.9447** (0.4161) |

2.5720** (1.0702) |

0.5804*** (0.2298) |

0.4421** (0.2048) |

| Product innovation | ||||

| Do not have product innovation activities | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Having product innovation activities | 0.6055*** (0.2418) |

1.8321*** (0.4429) |

0.3539*** (0.1392) |

0.3272*** (0.1219) |

| Smartphone use | ||||

| Not using smartphones for business | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Using smartphones for business | 1.2270*** (0.2742) |

3.4111*** (0.9351) |

0.7283*** (0.1561) |

0.5700*** (0.1441) |

| Constant | -2.8391** (1.3026) |

0.0585** (0.0762) |

-1.6544** (0.7326) |

-1.3615** (0.5716) |

| Facilitating conditions | ||||

| Computers use | ||||

| Not using computers for business | (Ref.) | |||

| Using computers for business | 0.1610*** (0.0492) |

|||

| Firm’s website | ||||

| Do not have own website | (Ref.) | |||

| Having own website | 0.6731*** (0.1082) |

|||

| Internet access | ||||

| Firm do not have access to the Internet | (Ref.) | |||

| Firm have access to the Internet | 0.0816*** (0.1200) |

|||

| Constant | -1.2083*** (0.1897) |

|||

| Observations | 462 | 462 | 462 | 512 |

| Log pseudolikelihood | -234.7048 | -234.7048 | -234.4637 | -539.3411 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2661 | 0.2661 | 0.2668 | |

| atanhrho_12 | -0.9456*** (0.2995) |

|||

| rho_12 | -0.7378 (0.1365) |

|||

Notes: Asterisks (***) denote significance at the 1% level, (**) indicate significance at the 5% level, and (*) represent significance at the 10% level. The term “Ref.” refers to the modality thresholds. Values in parentheses represent robust standard errors.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated