1. Introduction

Natural evolution has equipped biological materials in organisms with complex structures and functions that enable them to flourish in harsh environments over hundreds of millions of years [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Countless generations of adaptation and modification have led to an infinite variety of structures and properties in biological materials, enabling them to perform diverse functions, such as protecting cells and providing structural support for organisms (

Figure 1) [

1,

3,

6]. Synthetic materials have gradually replaced biological materials in many applications due to their superior performance in strength, durability, and mature large-scale fabrication strategies. Synthetic compounds have revolutionized several industries, including construction, manufacturing, electronics, and telecommunications, by offering materials with unprecedented properties and capabilities [

3,

7]. Although synthetic materials have many advantages, they still lack the sophisticated hierarchical structures and multifunctionality presented in biological materials [

8,

9,

10]. Researchers are inspired to explore the unique structures and properties of biological materials and seek ways to incorporate them into synthetic materials to overcome this limitation.

In recent years, researchers have made numerous breakthroughs in the fields of materials science and engineering through the exploration of biological materials. Contemporary advanced characterization and fabrication tools have allowed us to decipher and construct the intricate structures of these materials at different length scales, from the macroscopic to the atomic [

11,

12]. This has enabled us to better understand the hierarchical structures underlying multiscale biological materials, which consist of a diverse range of building blocks with tightly controlled sizes and shapes. These building blocks include fibrous, gradient, suture, layered, helical, tubular, cellular, overlapping, and more [

6,

9,

12]. The complex design mandates the precise ordering of these structure motifs with varying sizes and shapes into well-controlled arrangements that are reminiscent of walls constructed by individual bricks. The diverse range of building blocks and the coupling between different scales in the hierarchical design of multiscale biological materials are key to their remarkable properties. For instance, the nacre, which possesses a hierarchically ordered multiscale framework composed of rigid mineral tablets and soft organic constituents, exhibits exceptional mechanical properties, such as a fracture toughness value approximately 3000 times higher than the brittle aragonitic CaCO

3 [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Through the study of these multiscale structures, researchers have received insight into optimizing the properties of synthetic materials.

In addition, the multifunctionality of biomaterials has been identified as a pivotal factor in adapting to living environments, thereby advancing the efforts to effectively imitate natural materials and facilitate the development of novel synthetic materials [

3,

6,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Even though biological materials consist of a limited array of elements compared to synthetic compounds, which are chiefly composed of a few minerals, proteins, and polysaccharides such as chitin and cellulose. The versatility and diversity of properties exhibited by biological materials are remarkable. Recent studies have revealed that the diversity of biological materials stems not only from their composition but also from the complexity of their structures [

23,

24,

25,

26]. For instance, collagen is found in connective tissues like bone, skin, and cartilage, providing them with strength and flexibility. It is also employed as corneas to provide structural support and assist in refracting light [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Similarly, keratin, a protein utilized by some animals for gripping and snapping tools like nails or beaks, and also serves as thermal insulation in wool [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Moreover, biological materials exhibit a complex, multi-layered, and multi-scaled structure, where each layer or scale displays unique functionalities [

3,

6]. This inherent structural complexity enables biological materials to integrate different functions, resulting in exceptional multifunctionality. For example, mussel byssal threads are high-performance fibers with exhibit mechanical properties, while they also possess other functions (such as adhesion and self-healing) [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Similarly, melanin plays a role in coloring skin, hair, and eyes. It also protects against UV radiation while providing mechanical strengthening functions to tissues [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. The understanding of the significant roles that multifunctionality plays in biomaterials has opened new avenues for scientists to create multifunctional materials, which may lead to further innovations and breakthroughs in the design and development of functional materials.

The complex, multi-scale structure of biomaterials has generated considerable interest, but multifunctionality has also emerged as a critical aspect of engineering materials. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the diverse functionalities exhibited by biomaterials is essential to optimize and design the versatility and performance of synthetic materials. In this work, we provide an overview of some key functionalities exhibited by biological materials in natural organisms, including impact, wear and crush resistance, shape memory effects, self-healing properties, sensing, actuation, camouflage, adhesion, antifouling, and living strategies in extreme environments. Different functionalities may hold varying degrees of importance for different applications, and their combination can offer unprecedented advantages and possibilities for biological materials. In summary, this review sheds light on the relationship between the structure and functionality of biological materials, providing a valuable guidance for future research on bioinspired multifunctional materials, which will culminate in the creation of innovative, highly versatile materials.

2. Impact, Wear and Crush Resistance

One of the main functions of biological materials in natural organisms is serving as weapons and defense armors, such as teeth, scales, claws, horns, etc [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. To meet the mechanical requirement, the composed materials in biological tissues can be impact, wear and crush resistant, depending on the loading rate and time scale. For instance, mantis shrimp accelerate its dactyl club up to 20 m/s in less than 3 ms, leading to huge impact energy [

48,

53]. Similarly, bighorn sheep hurl themselves to fight with each other at an impact speed near 9 m/s [

54,

55]. In contrary, exoskeletons of insects and crustacean face quasi-static crush and low-speed impact from the tooth and claws of predators [

50,

52,

56]. In addition, biological tissues such as tooth and bone need to serve several years, which sometimes cannot be remodeled. This thus requires wear and fatigue resistance in a relative longer time period. We will take mantis shrimp dactyl club, iron-clad beetle exoskeleton and the teeth of chiton as examples to illustrate the structure-function relationship in biological tissues that working at different range of mechanical loading rates.

In

Figure 2, a schematic of the length scale of structures and the time scale of loading period is presented. The impact of mantis shrimp dactyl club occurred within several milliseconds, in which cavitation was observed due to the high-speed impact, leading to extreme damage of the hard preys. It has been summarized that the impact resistance of dactyl club stem from the gradient and hierarchical structure of dactyl clubs [

48]. The inner periodic region is composed of aligned chitin fibers that form a helicoidal pattern, which has been shown can deflect and twist cracks, thus increase the overall fracture toughness and impact energy dissipation. The outer nanoparticle region is responsible for absorbing the impact energy and prevent penetration. The bicontinuous hydroxyapatite nanoparticles show various energy dissipation mechanisms under high-speed impact: particle translation and breakage, organic fiber bridging, amorphization, etc. Different from mantis shrimp, the Diabolical ironclad beetle is well-known for its quasi-static crush resistance [

52,

57]. It can survive and withstand the crush even from automobile. Researchers showed the interdigitated suture structure and the laminated chitin fibers provided mechanical interlocking and resist crack propagating through the exoskeleton. In addition to high-speed impact and quasi-static crush, another common loading mode in nature is wear and fatigue, such as teeth. Chiton teeth is one of the examples showing fabulous wear resistant because of the compositions and microstructures [

51,

58]. Because of the hard teeth, chiton can scratch algae on the surface of rocks without severe damage to its teeth. It has been found the nanorods structure at the tip of tooth provide hardness and fracture toughness. The main composition of the tip of tooth is magnetite, and the hardness can reach 10 GPa, which is the hardest biomineral found on earth. At the nanoscale, magnetite nanorods are composed of proteins, chitin fibers and magnetite crystals. The intricate combination of organic and inorganic phases at the nanoscale is formed in the biomineralization process, which is seldom observed in synthetic systems.

In summary, the combination of organic and inorganic phases at different length scales can provide unexpected properties. The structural designs in natural organisms can sometimes overcome the contradicts in mechanical properties, such as hardness and toughness. The mechanical performance at different range of loading rate presented by natural organisms looks promising, which stimulate the innovations of high-performance engineering materials.

3. Self-Healing and Shape Memory Effect

In the last decade, the scientific community has taken a keen interest in exploring intelligent materials due to their potential to meet the increasing demands of technological advancements. According to the ability to respond to a wide range of stimuli (i.e., heat, light, humidity, pressure, pH, and so on), shape-memory and self-healing materials have been one of the most fascinating intelligent materials [

59,

60,

61,

62]. In this part, we will summarize the multiscale structure of spider silk and mussel byssal threads, and link these structures to the performance of shape memory and self-healing, which will inspire the design and preparation of synthetic materials.

3.1. Spider Silk

Spider silk is a remarkable fiber material with impressive stiffness and strength, making it an ideal candidate for various applications [

63,

64,

65]. Moreover, it exhibits a peculiar behavior under specific environmental conditions, such as contracting up to 50% of its original length when unrestrained and exposed to water or high humidity (Super contraction) [

66,

67,

68,

69]. When Spider silk is exposed to a stimulus, i.e., water, it undergoes a reversible phase transformation that allows it to recover its original shape. This humidity-sensitive behavior is a typical shape memory effect.

Spider silk is composed of protein molecules arranged in a multiscale structure (shown in

Figure 3A), with each level contributing to the final properties [

63,

64]. In the molecular scale, the proteins are essentially block copolymers, mainly containing two different major ampullate spidroins (MaSp), namely, MaSp1 and MaSp2. They have a large core domain of alternating alanine- and glycine-rich motifs, which are terminated by small non-repetitive amino- and carboxy-terminal domains. The alanine-rich motifs (polyalanine) form stable β-sheet crystallites, while the glycine-rich motifs (GGX, GPGXX) presumably form β-turns, β-spirals, α-helices, and random coils that constitute the amorphous matrix in which the crystallites are embedded [

65,

66]. At the nanoscale, the MaSp proteins assemble to form intermediate filaments with a diameter of 20-150 nm through simultaneous internal drawdown and material processing. These filaments are further coated with a thin layer (nanometer-scale) of spidroin-like proteins, glycoproteins, and lipids, which protects them from damage and contributes to the mechanical properties of the final material. At the microscale, these coated fibrils are arranged into a final structure with a diameter ranging from 2 to 7 μm.

Spider silk exhibits unique shape memory behavior, which arises from its synergistic structure comprising highly ordered β-sheet crystals and a less ordered, malleable amorphous network (depicted in Figure 3B). The β-sheet crystals serve as net points, providing the silk with remarkable strength. Conversely, the amorphous network, composed of α-helix, β-turn, and random coil structural elements, confers elasticity upon the silk. Notably, the β-sheet crystals formed by the polyalanine motifs are hydrophobic and less susceptible to humidity, while the elastic amorphous network undergoes supramolecular associations and dissociations of hydrogen bonds, rendering it highly responsive to moisture. Extensive research has been conducted to investigate the contributions of various components in spider silk to its shape memory behavior. It has been found that the amorphous region of MaSp2 plays a vital role in the association and dissociation of hydrogen bonds. This region is rich in prolines, which produce a unidirectional twist and cause steric exclusion effects after external stimulus, disrupting hydrogen bonds in their vicinity and acting as a switch in the shape memory behavior. In particular, a humidity-responsive shape memory model for spider silk has been proposed, as programmed in

Figure 3C [

67,

68,

69]. When the spider silk is stretched, some of the hydrogen bonds break, which deforms the shape of the specimen. The entropy elasticity of the silk causes it to slightly recover. After being exposed to water, water molecules interfere with the hydrogen bonds in the network, causing the silk to plasticize and exhibit super contraction. Upon drying, the hydrogen bonds recombine, causing the silk to recover its original length. This shape memory mechanism has also been observed in other protein based biological materials, such as keratin.

3.2. Mussel byssal Threads

Mussels (

Figure 4A) are well-known for their ability to firmly attach themselves to rocky surfaces, nearby shells, and other hard substrates using a proteinaceous attachment device called the byssus [

36,

37,

70,

71]. A typical byssus from marine mussels has 50-100 byssal threads composed of numerous self-healing fibers made up of specific protein building blocks. The distal region of the byssal thread is hard, extensible, and tough, capable of dispersing a large amount of mechanical energy through a hysteresis effect. When the mechanical yield is exceeded, the distal region exhibits reduced stiffness and hysteresis effect in subsequent cycles, but after a sufficient rest period, it can fully recover its initial performance. This self-healing behavior is entirely dependent on the specific structure and chemical properties of the protein building blocks that make up the thread [

35,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The impressive self-healing properties and potential biomimetic applications of the threads of bivalves have attracted considerable attention from researchers, who are studying their molecular architecture and properties to gain insights into how they achieve their remarkable performance.

Mussel byssal threads are comprised of three distinct regions, namely the plaque, the core, and the cuticle (

Figure 4B), with the core believed to be the primary determinant of the overall tensile strength [

37]. The core of the thread has a 6+1 hexagonal bundle structure consisting of seven triple-helical collagens called PreCols. The central rod-like domain of the PreCol has a typical rigid fibrous collagen [Gly-X-Y]n repeat sequence, approximately 150 nm in length, where X and Y are usually proline or hydroxyproline (

Figure 4C). The folded flanking domains of the PreCol are extensible and have different variants, including PreCol-D, an arm-like domain resembling a cable with a polyproline sequence and glycine-rich spacers; PreCol-P, with hydrophobic sequences resembling those of elastin; and PreCol-NG, a highly flexible whip-like domain.

The self-healing ability of byssal threads has been an intriguing topic in biomaterials research. Recent studies have shown that the extensible domains, instead of the collagen domains, are responsible for this property [

37,

40]. These domains are composed of histidine-rich regions (HRDs) that are capable of binding transition metal ions. The histidine ligands in HRDs donate electrons to form coordination bonds with these ions. Self-healing occurs through the re-formation and exchange of broken metal coordination bonds, leading to the restoration of stiffness and a native-like cross-link network (

Figure 4D) [

41,

42]. Under mechanical stress, sacrificial bond topology offers resistance to deformation and exhibits high stiffness. As the level of strain increases, sacrificial bonds rupture and exchange ligands with neighboring groups, thereby allowing for the extension of length. Eventually, under very high levels of strain, the amino acid ligands are replaced by water molecules. Interestingly, after relaxation, the protein-metal coordination bonds re-form with a less stable topology. They slowly convert back towards the initial structure through the exchange of ligands, which results in more native-like mechanical properties.

4. Adhesion and Anti-Fouling

Surface adhesion is a crucial concern in multiple technological fields [

72,

73,

74]. Surface contaminants are one of the primary factors that affect adhesion strength [

74,

75]. Researchers have been seeking inspiration from nature to solve this issue. Mussels and geckos are two of the most well-known examples of natural adhesion and anti-fouling. Mussels regulate the pH of their surroundings to clean rock surfaces and form robust plaques that adhere firmly to the substrate. They achieve this by employing a variety of molecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and metal coordination, to strengthen adhesion [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81]. In contrast, geckos have multi-scale structured toe pads that allow them to develop a sturdy adhesive system. And geckos' toe pads display superhydrophobic properties that defend them against contamination [

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89]. Gaining an understanding of the principles that govern natural adhesion and anti-fouling could offer valuable insights for the advancement of new technologies in surface engineering.

4.1. Mussel Byssus Plaque

Marine bivalves, such as clams, mussels, and oysters, are more than a source of food or ornamental shells [

36]. They serve as sentinels for the health of coastal ecosystems, providing important ecosystem services that are more relevant in the face of pollution and climate change. Mussels, especially those that form reefs or beds, play an important role as "ecosystem engineers" in coastal environments, similar to the role played by coral reefs in tropical waters. They also help to stabilize sediments, reduce wave energy, and improve water quality by filtering large volumes of water as they feed. Finally, mussels can serve as models for bioinspired technologies, as their unique adaptations to their environment have inspired the development of new materials and designs. For instance, the adhesive properties of mussels byssal threads (

Figure 5C) [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81], which they use to attach themselves to surfaces, have been studied for their potential application in surgical adhesives and other biomedical applications.

Adhesion proteins are secreted by the foot's contact surface, facilitating attachment to various substrates. The adhesion process (

Figure 5A) is complex and involves a series of physicochemical interactions between the foot and the substrate. The conditions required for adhesion differ from those found in seawater, such as pH and ionic strength. Organisms can create an environment conducive to the formation of cells and fluids by raising "ceilings" and creating cavitation, where the average pH is approximately 3 and the ion strength is 0.15 mol/L [

76]. The pH adjustment process plays a crucial role in cleaning surfaces, killing surface-adhered microorganisms, and regulating the redox environment. The unoxidized form of Dopa is also essential in adhesion, while Dopa-quinone (from oxidation of Dopa) facilitates protein cross-linking [

77,

78]. Hence, redox adjustment is necessary to control location-specific redox. Despite Dopa-quinone's excellent cohesive properties, its surface binding characteristics are poor. Therefore, a "self-reduction" process is necessary to reduce Dopa-quinone to catechol (Δ-Dopa), where many of the original dopamine properties can be used again, such as metal coordination, re-oxidation, and hydrogen bonding (

Figure 5B) [

79]. Finally, the liquid rich in protein solidifies through condensation and becomes a plaque.

Researchers have long been fascinated by the mussel's adhesive properties, which are largely due to the synergistic interplay between the structural components of its byssal threads and adhesive plaques [

80,

81]. At the centimeter scale, the radial distribution of byssal threads (

Figure 5C) in each mussel allows them to withstand dynamic loading, increasing their toughness by up to 900 times. At the millimeter scale, the distinctive spoon-like shape (

Figure 5D) of plaques further enhances their adhesion performance. Compared to a cylindrical shape with the same contact area, the spoon-shaped structure improves adhesion by a factor of 20. This is due to the increased contact area and greater surface energy of the spoon-shaped structure, which allows it to create stronger bonds with the substrate. At the microscale, these plaques are composed of a porous solid (

Figure 5E) with two distinct length scales of pores, which act to prevent crack propagation, increase energy dissipation, and promote reversible deformation, thereby enhancing the toughness of the adhesive.

4.2. Gecko Toe Pads

Geckos (

Figure 6A) are fascinating animals found in warm climates, known by their specialized and multifunctional toe pads. These pads possess an efficient reversible adhesive system, which enables geckos to climb almost any surface whether it is rough, smooth, vertical, or inverted [

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89]. In the meantime, the pads also possess superhydrophobic surfaces. This combined performance of high adhesion and anti-fouling has inspired the development of engineering materials such as grabbing robotic hands.

Under microscopic examination, researchers discovered that geckos' toe pads contain almost half a million keratinaceous hairs or scales [

82,

83,

84,

85,

86]. Each of these measures between 30-130 micrometers in length, which is only one-tenth of the diameter of a human hair. These small structures are composed of hundreds of conical protrusions. Additionally, each protrusion ends in a spatula-shaped structure that measures between 200-500 nm in length (

Figure 6C) [

89].

Recent studies have uncovered the remarkable adhesive ability of gecko toe pads, which is attributed to their hierarchical micro- and nano-structures, which form a periodic array. When the toe pad contacts a surface, the spatula-shaped structures deform, thereby increasing the contact area between the large molecules and converting weak van der Waals interactions into a tremendous attractive force, allowing geckos to effortlessly ascend vertical walls or traverse ceilings [

86,

87]. The material of gecko foot-hair is composed of relatively hard and hydrophobic β-keratin, including the claws used for mechanical locking (

Figure 6D). Geckos have the ability to adhere to surfaces of virtually any roughness and detach with ease at speeds that exceed 1 m/s. In addition to their adhesive properties, the water contact angle of gecko scales (θ) is approximately 160° (

Figure 6E), which may be attributed to the micro-roughness of the scales and skin, providing them with self-cleaning properties [

88,

89].

5. Sensing, Actuating and Camouflage

Given the rapid advancement of intelligent robotics and the increased pressure from modern warfare, the field of research on intelligent sensing and responsive materials has gained significant interest [

90,

91,

92,

93]. Consequently, the study of sensing-camouflage and sensing-actuating principles found in biology, such as those observed in moths, chameleons, and banksia plants, has become a focal point. Moths possess remarkable sensing-camouflage abilities that allow them to blend seamlessly into their environment and evade predators. Similarly, chameleons are well-known for their color-changing abilities, which enable them to blend in with their surroundings or communicate with other chameleons. Banksia plants, on the other hand, utilize their sensing-actuating abilities to safeguard their seeds from fire. When exposed to high temperatures and moisture, the plant's cones open, and the seeds are released.

5.1. Moth Wings

Lepidopterans' wing color is determined by both pigment and structure, which enables them to achieve their camouflage function [

94,

95,

96,

97]. In this part, we provide a detailed explanation of how the multi-scale structure of a moth's wings helps it achieve camouflage. Bogong moths (Agrotis infusa) are a species of nocturnal moth notable for their seasonal long-distance migration to the Australian Alps, shown in

Figure 7A [

97]. This species undertakes two migrations each year, in the spring and autumn, traveling up to 1,000 kilometers to reach their summer and winter habitat. The Bogong moth precisely navigates over such long distances, relying on visual cues and the Earth's magnetic field for navigation. Research suggests that the moth's reliance on visual cues and the Earth's magnetic field for navigation is remarkable. In addition to their unique brownish hue, Bogong moths are also known for their ability to blend in with their surroundings during the day, making them less visible to potential predators in the open plains they traverse.

The wings of the Bogong moths are composed of two layers of chitinous scales, as shown in

Figure 7B. The well-structured upper lamina is made up of parallel ridges (consisting of slightly overlapping lamellae) and interconnected cross-ribs, leaving minor open windows. Moreover, the top and middle areas of ridges contain a large number of melanin pigments, regarded as brown filters [

94,

95]. On the other hand, the flat lower lamina is a slightly wrinkled plane that serves as a reflector, with variable thicknesses. The combination of the windows, reflectors, and filters in the scales creates a complex optical system, which determines the wing coloration. Additionally, a series of beams and columns act as connection units between the two layers, providing mechanical support and spacing.

When incident light enters the upper layer, most of it passes through the windows. As the film reflector, the lower layer partly reflects the above-transmitted light. Finally, a major fraction of this reflected light reaches again the upper layer, absorbed by a spectral filter (melanin pigments). Hence, the coloration of Bogong moths is not particularly striking, which will match the trees, providing them with perfect camouflage (

Figure 7C) [

96,

97]. More, they will optimize the locations and orientations on the bark, to maximize their camouflage potential. However, their coloration does not match well with the granite rock in their aestivation caves. As a result, the moths have to tile tightly and form carpets at the cave wall, camouflaged against themselves. In conclusion, Bogong moths have evolved a unique capability of sensing camouflage, which enables them to seamlessly integrate into their environment, making them difficult to be detected by predators.

5.2. Chameleons

Chameleons are renowned for the ability to change their coloration depending on their surroundings, through a complex interplay of pigment and structure color [

98,

99,

100,

101]. Some of them switch colors rapidly in response to outside stimuli (i.e., courtship, male contests, and so on), while others might spend several hours or even days. According to their particular environment, chameleons show distinctive coloration. For example, the chameleons living in forested areas obtain more vivid and varied colors. By contrast, the chameleons inhabiting arid or grassy surroundings tend to show brown or tan color. This crypsis, from the ability to sensing-camouflage, is their primary defense when facing the predators of birds and snakes [

98,

102].

Chameleons obtain a unique visual system, which permits two eyes to move independently and focus on two different objects simultaneously, forming a full 360-degree arc of vision around their bodies [

98,

99]. With the aid of visuals, chameleons can do stereoscopic scans of their surroundings to discover dangerous predators, which is the foundation of camouflage. The mechanism of camouflage in chameleons has been in the spotlight [

100,

101,

102]. It is generally interpreted that these abilities are due to the dispersion/aggregation of pigment. And recent research has found that the active tuning of guanine nanocrystals and cytoplasm in iridophores is also responsible for the color change. In

Figure 8A, the skin of adult male panther chameleons possesses a multilayer structure, with S-iridophores in the upper layer and D-iridophores in the lower layer. S-iridophores (

Figure 8B) contain small, densely packed guanine crystals with a higher refractive index, dispersed in the cytoplasm (the lower refractive index materials). This arrangement of high and low refractive index materials acts as a photonic crystal, affecting the color of the skin. Specifically, the distance of guanine nanocrystals is increased in excited male panther chameleons compared with the relaxed individual (

Figure 8D to 8G), presenting a red shift in the reflectance and absorption spectrum, and finally leading to the orange skin. On the other hand, D-iridophores with larger, more irregularly shaped guanine crystals, play a crucial role in thermal protection by absorbing and reflecting heat. The combination of S- and D-iridophores plays an important role in thermoregulation, which is helpful for more perfect camouflage. This iridophore system provides a potent example of how structure and function interplay in evolutionary processes and offers implications for the development of intelligent biomimetic materials.

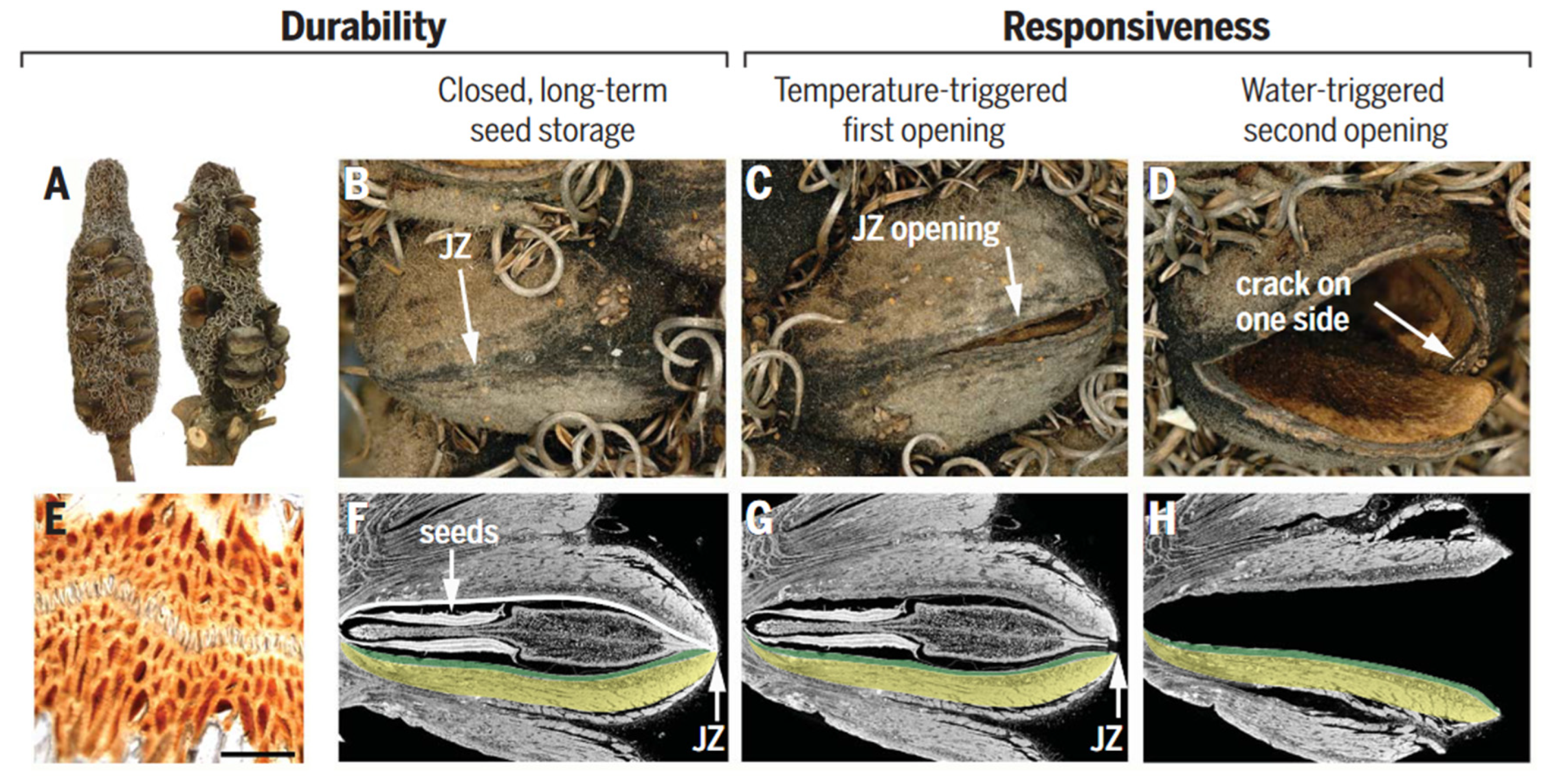

5.3. Banksia Seed Pods

Many plants in nature have developed strategies to optimize the dispersal and germination of their seeds [

3]. Instead of releasing their seeds immediately upon maturity, these plants often wait for optimal conditions for seed dispersal and germination. For instance, the Australian plant genus Banksia stores seeds in metabolically inactive closed pods that can remain viable for up to 15 years (

Figure 9A) [

103,

104,

105,

106]. Specific environmental stimulations, including temperature and rainfall patterns, trigger the release of these seeds. Different species and individuals may respond differently to these stimulations, depending on their geographic location and climatic conditions. The seed pods resemble small robotic devices, performing a simple task (releasing seeds) after two consecutive signals coming from nature without an external energy source. These processes inspire the design of intelligent soft robots [

92,

105].

Seed pods are complex structures, composed of a diverse range of materials, including cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, wax, and tannins, which contribute to both structural and functional roles [

103]. These materials determine the pod's mechanical properties, including strength, elasticity, and resistance to environmental stresses, such as temperature and humidity fluctuations. The pods consist of two pericarp valves, each comprising three distinct layers (i.e., endo-, meso-, and exocarp), with varying orientations of cellulose fibers. These multilayer structures create internal stresses that facilitate seed release. The junction zone, which connects the two valves, is composed of interdigitating cells with a high surface area (

Figure 9B, C, and E) [

3,

104]. To prevent water loss and the adhesion of insects or microorganisms, the above structures are coated with wax. During summer days, when temperatures reach about 45 to 50°C, the wax melts and seals microcracks caused by environmental challenges.

The mechanism of seed release in Banksia attenuata is closely related to the geometric structure of its internal follicles [

105,

106]. Specifically, the curvature radius of the inner pericarp plays a crucial role in determining the temperature at which seed release begins and the size stability of the released seeds. When exposed to high temperatures, the inner pericarp undergoes a softening process, which causes a shift in the internal force balance (

Figure 9F,G). This shift triggers the release of stored pre-stress through the formation of cracks and initial openings. Further opening (

Figure 9D) of the follicle requires a cycle of wetting and drying to activate the double-layered bending (

Figure 9H) of the endocarp and mesocarp.

6. Lives in Extreme Environment

In previous sections, we discussed organisms evolve specific structures to realize various functions and adapt to the surrounding environment. There are extreme environment existing on earth that make lives much harder, where prerequisite living strategies are necessary for organisms, such as deep sea where there is high pressure and no light; dry desert where there is very limited water and food; vent of volcano where extreme temperature occurs, etc [

107,

108,

109]. Interestingly, lives have been found inhabiting these extreme environments. It is worthwhile looking into the living strategies of the organisms, which could give us inspirations of inventing new materials or solutions that can help us live in extreme environments, such as Mars.

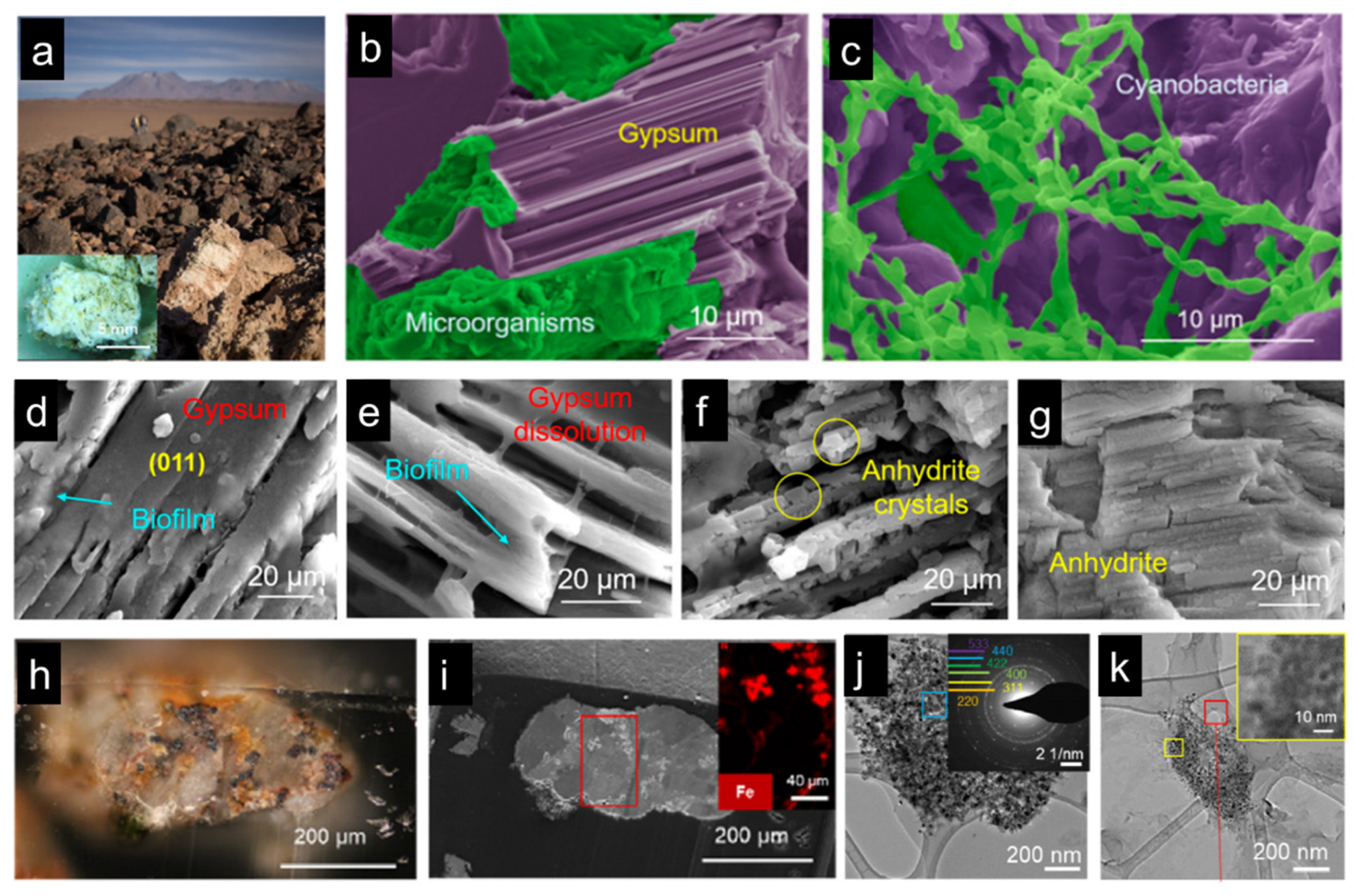

One of the examples is the cyanobacteria that live in the driest non-polar place on earth, the Atacama Desert (

Figure 10a-c) [

107]. It has been found that due to the lack of water, cyanobacteria can extract the crystalline water from gypsum as its water source, cause the phase transformation of its surrounding rock from gypsum to anhydrite phase. Surrounding the cyanobacteria colony, organic biofilm was detected. The dissolution of gypsum crystals nearby the organic biofilm was observed, which was believed because of the organic acids existing in the biofilm (

Figure 10d-g) [

107]. In the meantime, water molecules were released as the dissolution process proceeded. In addition to water, it has also been noticed that cyanobacteria can acquire iron ions from the surrounding rocks. Iron is one of the most important trace elements, playing a critical role in the metabolism and photosynthesis process of cyanobacteria. In order to get iron, cyanobacteria have to searching iron sources from the surrounding minerals, where magnetite and hematite were found (

Figure 10h-i) [

108]. Combining high-resolution microscopy and spectroscopy techniques, it was provided that the biofilms surrounding the cyanobacteria colony could also dissolve magnetite minerals, and iron ions were thus released from the solid minerals (

Figure 10j-k) [

108]. And due to the photosynthesis process, oxygen is produced, which turns magnetite to hematite surrounding the cyanobacteria colony. This whole living strategy of cyanobacteria in extreme dry place can provide inspirations for inventing techniques and materials that facilitate human beings inhabit in space, such as Mars.

7. Conclusions and Outlook

Multifunctional micro- and nano-structured materials play a vital role in diverse fields, including energy, defense, aerospace and biomedical engineering. Scientists seek to emulate the strategies found in nature, where materials exhibit multiscale structures and multifunctional properties that have been refined through evolution. Biological tissues, primarily composed of proteins, polysaccharides and biominerals, possess a limited variety of chemical components that are biodegradable and recyclable. However, these tissues in natural organisms can optimize specific properties and attain multifunctional integration by employing structural design at varying scales. In the current work, we present several attractive functions realized in natural organisms. However, the contents we discussed here are just the tip of the iceberg, the mysterious functions and marvelous structures in nature are always waiting for us to explore. By understanding the mechanisms that underlie biological structures and multifunction, researchers can get inspirations and develop biomimetic materials that substantially enhance human life while providing valuable insights into designing artificial materials with unparalleled properties and capabilities.

Researchers have employed various advanced techniques, including nanolithography, self-assembly, freeze casting and additive manufacturing, to fabricate and manipulate materials at different length scales. By combining biomimetic design principles with these techniques, they can generate materials that mirror the structure and function of natural materials. One promising method is using synthetic polymers that can self-assemble into diverse shapes and sizes that emulate the hierarchical structures of biological materials. These materials can incorporate functional molecules like enzymes, antibodies, and nanoparticles, enabling specific properties and applications. Another approach is to employ nanoscale building blocks, such as carbon nanotubes, graphene, and metal nanoparticles, to create materials with tailored functionalities and properties. These building blocks can be assembled into intricate architectures like nanocomposites and hierarchical structures to achieve adaptability and multifunctionality.

In conclusion, comprehending the structural-functional integration mechanism in nature can inspire the design and preparation of synthetic compounds with multifunction. The optimized multiscale structure and multifunction will meet the requirements of the next generation of engineering materials, which tackle the most pressing challenges that our society is now facing society.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the start-up funding from Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 3004110199).

References

- Wegst, U.G.K.; Bai, H.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Bioinspired Structural Materials. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Naleway, S.E.; Wang, B. Biological and Bioinspired Materials: Structure Leading to Functional and Mechanical Performance. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eder, M.; Amini, S.; Fratzl, P. Biological Composites-Complex Structures for Functional Diversity. Science 2018, 362, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, M.A.; Chen, P.-Y.; Lin, A.Y.-M.; Seki, Y. Biological Materials: Structure and Mechanical Properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2008, 53, 1–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, M.A.; McKittrick, J.; Chen, P.-Y. Structural Biological Materials: Critical Mechanics-Materials Connections. Science 2013, 339, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, D.; Kang, S.; Adstedt, K.M.; Kanhaiya, K.; Bockstaller, M.R.; Brinson, L.C.; Buehler, M.J.; Coveney, P.V.; Dayal, K.; El-Awady, J.A.; et al. Hierarchically Structured Bioinspired Nanocomposites. Nat. Mater. 2023, 22, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthelat, F.; Yin, Z.; Buehler, M.J. Structure and Mechanics of Interfaces in Biological Materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, G. Rigid Biological Systems as Models for Synthetic Composites. Science 2005, 310, 1144–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Restrepo, D.; Jung, J.; Su, F.Y.; Liu, Z.; Ritchie, R.O.; McKittrick, J.; Zavattieri, P.; Kisailus, D. Multiscale Toughening Mechanisms in Biological Materials and Bioinspired Designs. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1901561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, H.D.; Rim, J.E.; Barthelat, F.; Buehler, M.J. Merger of Structure and Material in Nacre and Bone-Perspectives on de Novo Biomimetic Materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009, 54, 1059–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelat, F. Architectured Materials in Engineering and Biology: Fabrication, Structure, Mechanics and Performance. Int. Mater. Rev. 2015, 60, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naleway, S.E.; Porter, M.M.; McKittrick, J.; Meyers, M.A. Structural Design Elements in Biological Materials: Application to Bioinspiration. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 5455–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.-B.; Ge, J.; Mao, L.-B.; Yan, Y.-X.; Yu, S.-H. 25th Anniversary Article: Artificial Carbonate Nanocrystals and Layered Structural Nanocomposites Inspired by Nacre: Synthesis, Fabrication and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addadi, L.; Joester, D.; Nudelman, F.; Weiner, S. Mollusk Shell Formation: A Source of New Concepts for Understanding Biomineralization Processes. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.-B.; Gao, H.-L.; Yao, H.-B.; Liu, L.; Cölfen, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, S.-M.; Li, S.-K.; Yan, Y.-X.; Liu, Y.-Y.; et al. Synthetic Nacre by Predesigned Matrix-Directed Mineralization. Science 2016, 354, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checa, A.G.; Cartwright, J.H.E.; Willinger, M.-G. The Key Role of the Surface Membrane in Why Gastropod Nacre Grows in Towers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuprian, E.; Munkler, C.; Resnyak, A.; Zimmermann, S.; Tuong, T.D.; Gierlinger, N.; Müller, T.; Livingston, D.P.; Neuner, G. Complex Bud Architecture and Cell-Specific Chemical Patterns Enable Supercooling of Picea Abies Bud Primordia. Plant Cell Environ 2017, 40, 3101–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyroud, E.; Wenzel, T.; Middleton, R.; Rudall, P.J.; Banks, H.; Reed, A.; Mellers, G.; Killoran, P.; Westwood, M.M.; Steiner, U.; et al. Disorder in Convergent Floral Nanostructures Enhances Signalling to Bees. Nature 2017, 550, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T.N.; Wang, B.; Espinosa, H.D.; Meyers, M.A. Extreme Lightweight Structures: Avian Feathers and Bones. Mater. Today 2017, 20, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquato, S.; Hyun, S.; Donev, A. Optimal Design of Manufacturable Three-Dimensional Composites with Multifunctional Characteristics. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 94, 5748–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F.; Bréchet, Y.J.M.; Cebon, D.; Salvo, L. Selection Strategies for Materials and Processes. Mater. Des. 2004, 25, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, C.J.; Wilts, B.D.; Brodie, J.; Vignolini, S. Structural Color in Marine Algae. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1600646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzt, E. Biological and Artificial Attachment Devices: Lessons for Materials Scientists from Flies and Geckos. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2006, 26, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studart, A.R. Biological and Bioinspired Composites with Spatially Tunable Heterogeneous Architectures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 4423–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studart, A.R. Biologically Inspired Dynamic Material Systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3400–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Meyers, M.A.; Zhang, Z.; Ritchie, R.O. Functional Gradients and Heterogeneities in Biological Materials: Design Principles, Functions, and Bioinspired Applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 88, 467–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, L.; Oldberg, Å.; Heinegård, D. Collagen Binding Proteins. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2001, 9, S23–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Wang, N.; You, X.-G.; Zhang, A.-D.; Chen, X.-G.; Liu, Y. Collagen-Based Biocomposites Inspired by Bone Hierarchical Structures for Advanced Bone Regeneration: Ongoing Research and Perspectives. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 318–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagini, C.; Riccitelli, F.; Messina, M.; Piccinelli, F.; Torroni, G.; Said, D.; Al Maazmi, A.; Dua, H.S. Epi-off-Lenticule-on Corneal Collagen Cross-Linking in Thin Keratoconic Corneas. Int. Ophthalmol. 2020, 40, 3403–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.; Sun, L.; Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Shang, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, L. Recombinant Human Collagen Hydrogels with Hierarchically Ordered Microstructures for Corneal Stroma Regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, D.; Liao, Z.; Gong, Z.; Zhao, W.; Gu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, J. Extraction of Keratin from Pig Nails and Electrospinning of Keratin/Nylon6 Nanofibers for Copper (II) Adsorption. Polymers 2023, 15, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Zaheri, A.; Yang, W.; Kisailus, D.; Ritchie, R.O.; Espinosa, H.; McKittrick, J. How Water Can Affect Keratin: Hydration-Driven Recovery of Bighorn Sheep ( Ovis Canadensis ) Horns. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1901077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C Marshall, R.; Gillespie, J. The Keratin Proteins of Wool, Horn and Hoof from Sheep. Aust. Jnl. Bio. Sci. 1977, 30, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Zhou, H.; Forrest, R.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Dyer, J.; Luo, Y.; Hickford, J. Wool Keratin-Associated Protein Genes in Sheep—A Review. Genes 2016, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.N.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, W.H. Bioinspired Self-Healable Polyallylamine-Based Hydrogels for Wet Adhesion: Synergistic Contributions of Catechol-Amino Functionalities and Nanosilicate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 18324–18337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waite, J.H. Mussel Adhesion – Essential Footwork. J. Exp. Biol. 2017, 220, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, M.J.; Jehle, F.; Priemel, T. Mussel Byssus Structure-Function and Fabrication as Inspiration for Biotechnological Production of Advanced Materials. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, 1800133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Li, K.; Yu, G.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, Y. Mussel-Inspired and Aromatic Disulfide-Mediated Polyurea-Urethane with Rapid Self-Healing Performance and Water-Resistance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 593, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Mi, H.-Y.; Napiwocki, B.N.; Peng, X.-F.; Turng, L.-S. Mussel-Inspired Electroactive Chitosan/Graphene Oxide Composite Hydrogel with Rapid Self-Healing and Recovery Behavior for Tissue Engineering. Carbon 2017, 125, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.N.Z.; Politi, Y.; Reinecke, A.; Harrington, M.J. Role of Sacrificial Protein–Metal Bond Exchange in Mussel Byssal Thread Self-Healing. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 2852–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, S.; Metzger, T.H.; Fratzl, P.; Harrington, M.J. Self-Repair of a Biological Fiber Guided by an Ordered Elastic Framework. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, B.K.; Lee, D.W.; Israelachvili, J.N.; Waite, J.H. Surface-Initiated Self-Healing of Polymers in Aqueous Media. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.; Shawkey, M.D.; Dhinojwala, A. Bioinspired Melanin-Based Optically Active Materials. Adv. Optical Mater. 2020, 8, 2000932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, A.; Tobin, D.J.; Shibahara, S.; Wortsman, J. Melanin Pigmentation in Mammalian Skin and Its Hormonal Regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 1155–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, D.N.; Mattoni, M.A.; Slack, N.L.; Waite, J.H.; Zok, F.W. Role of Melanin in Mechanical Properties of Glycera Jaws. Acta Biomater. 2006, 2, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.-N.; Simon, J.D.; Sarna, T. Role of Ocular Melanin in Ophthalmic Physiology and Pathology. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arao, T.; Perkins, E. The Skin of Primates. XLIII. Further Observations on the Philippine Tarsier (Tarsius Syrichta). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1969, 31, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Shishehbor, M.; Guarín-Zapata, N.; Kirchhofer, N.D.; Li, J.; Cruz, L.; Wang, T.; Bhowmick, S.; Stauffer, D.; Manimunda, P.; et al. A Natural Impact-Resistant Bicontinuous Composite Nanoparticle Coating. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Huang, W.; Pham, C.H.; Murata, S.; Herrera, S.; Kirchhofer, N.D.; Arkook, B.; Stekovic, D.; Itkis, M.E.; Goldman, N.; et al. Mesocrystalline Ordering and Phase Transformation of Iron Oxide Biominerals in the Ultrahard Teeth of Cryptochiton Stelleri. Small Struct. 2022, 3, 2100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaraghi, N.A.; Trikanad, A.A.; Restrepo, D.; Huang, W.; Rivera, J.; Herrera, S.; Zhernenkov, M.; Parkinson, D.Y.; Caldwell, R.L.; Zavattieri, P.D.; et al. The Stomatopod Telson: Convergent Evolution in the Development of a Biological Shield. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1902238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Hogan, A.; Huang, W.; Serrano, C.; Kisailus, D.; Meyers, M.A. Tooth Structure, Mechanical Properties, and Diet Specialization of Piranha and Pacu (Serrasalmidae): A Comparative Study. Acta Biomater. 2021, 134, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, J.; Hosseini, M.S.; Restrepo, D.; Murata, S.; Vasile, D.; Parkinson, D.Y.; Barnard, H.S.; Arakaki, A.; Zavattieri, P.; Kisailus, D. Toughening Mechanisms of the Elytra of the Diabolical Ironclad Beetle. Nature 2020, 586, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, J.C.; Milliron, G.W.; Miserez, A.; Evans-Lutterodt, K.; Herrera, S.; Gallana, I.; Mershon, W.J.; Swanson, B.; Zavattieri, P.; DiMasi, E.; et al. The Stomatopod Dactyl Club: A Formidable Damage-Tolerant Biological Hammer. Science 2012, 336, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Zaheri, A.; Jung, J.-Y.; Espinosa, H.D.; Mckittrick, J. Hierarchical Structure and Compressive Deformation Mechanisms of Bighorn Sheep (Ovis Canadensis) Horn. Acta Biomater. 2017, 64, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchener, A. An Analysis of the Forces of Fighting of the Blackbuck ( Antilope Cervicapra ) and the Bighorn Sheep ( Ovis Canadensis ) and the Mechanical Design of the Horn of Bovids. J. Zool. 1988, 214, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Montroni, D.; Wang, T.; Murata, S.; Arakaki, A.; Nemoto, M.; Kisailus, D. Nanoarchitected Tough Biological Composites from Assembled Chitinous Scaffolds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckham, G.T.; Crowley, M.F. Examination of the α-Chitin Structure and Decrystallization Thermodynamics at the Nanoscale. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 4516–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Obaldia, E.E.; Jeong, C.; Grunenfelder, L.K.; Kisailus, D.; Zavattieri, P. Analysis of the Mechanical Response of Biomimetic Materials with Highly Oriented Microstructures through 3D Printing, Mechanical Testing and Modeling. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 48, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Qi, H.J.; Xie, T. Recent Progress in Shape Memory Polymer: New Behavior, Enabling Materials, and Mechanistic Understanding. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 49–50, 79–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Li, G. A Review of Stimuli-Responsive Shape Memory Polymer Composites. Polymer 2013, 54, 2199–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.L.; In Het Panhuis, M. Self-Healing Hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 9060–9093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zuo, J. Self-Healing Polymers Based on Coordination Bonds. Adv. Mater. 2019, 1903762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaris, A.; Arcidiacono, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, J.-F.; Duguay, F.; Chretien, N.; Welsh, E.A.; Soares, J.W.; Karatzas, C.N. Spider Silk Fibers Spun from Soluble Recombinant Silk Produced in Mammalian Cells. Science 2002, 295, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollrath, F.; Knight, D.P. Liquid Crystalline Spinning of Spider Silk. Nature 2001, 410, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anton, A.M.; Heidebrecht, A.; Mahmood, N.; Beiner, M.; Scheibel, T.; Kremer, F. Foundation of the Outstanding Toughness in Biomimetic and Natural Spider Silk. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 3954–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnarsson, I.; Kuntner, M.; Blackledge, T.A. Bioprospecting Finds the Toughest Biological Material: Extraordinary Silk from a Giant Riverine Orb Spider. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, G. Spider-Silk-like Shape Memory Polymer Fiber for Vibration Damping. Smart Mater. Struct. 2014, 23, 105032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Y. Shape-Memory Biopolymers Based on β-Sheet Structures of Polyalanine Segments Inspired by Spider Silks: Shape-Memory Biopolymers Based on β-Sheet Structures of Polyalanine Segments Inspired by Spider Silks. Macromol. Biosci. 2013, 13, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Kim, Y.; Na, S.; Liu, W.; Hu, J. Artificial Spider Silk Is Smart like Natural One: Having Humidity-Sensitive Shape Memory with Superior Recovery Stress. Mater. Chem. Front. 2019, 3, 2472–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryou, M.-H.; Kim, J.; Lee, I.; Kim, S.; Jeong, Y.K.; Hong, S.; Ryu, J.H.; Kim, T.-S.; Park, J.-K.; Lee, H.; et al. Mussel-Inspired Adhesive Binders for High-Performance Silicon Nanoparticle Anodes in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.K. Perspectives on Mussel-Inspired Wet Adhesion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10166–10171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Work, A.; Lian, Y. A Critical Review of the Measurement of Ice Adhesion to Solid Substrates. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2018, 98, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maboudian, R. Critical Review: Adhesion in Surface Micromechanical Structures. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 1997, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Bawazir, M.; Dhall, A.; Kim, H.-E.; He, L.; Heo, J.; Hwang, G. Implication of Surface Properties, Bacterial Motility, and Hydrodynamic Conditions on Bacterial Surface Sensing and Their Initial Adhesion. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 643722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, G.D. Contamination of Surfaces: Origin, Detection and Effect on Adhesion. Surf. Interface Anal. 1993, 20, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D.G.; Fullenkamp, D.E.; He, L.; Holten-Andersen, N.; Lee, K.Y.C.; Messersmith, P.B. PH-Based Regulation of Hydrogel Mechanical Properties Through Mussel-Inspired Chemistry and Processing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, J.R.; Wojtas, J.L.; Cloud, J.L.; Wilker, J.J. A Method for Measuring the Adhesion Strength of Marine Mussels. J. Adhes. 2009, 85, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Miller, D.R.; Kaufman, Y.; Martinez Rodriguez, N.R.; Pallaoro, A.; Harrington, M.J.; Gylys, M.; Israelachvili, J.N.; Waite, J.H. Tough Coating Proteins: Subtle Sequence Variation Modulates Cohesion. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, K.W.; Zacchia, N.A.; Waite, J.H.; Valentine, M.T. Dynamics of Mussel Plaque Detachment. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 6832–6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, S.A.; Yang, L.-M.; Saha, L.C.; Ahmed, E.; Ajmal, M.; Ganz, E. A Fundamental Understanding of Catechol and Water Adsorption on a Hydrophilic Silica Surface: Exploring the Underwater Adhesion Mechanism of Mussels on an Atomic Scale. Langmuir 2014, 30, 6906–6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Lee, D.W.; Ahn, B.K.; Seo, S.; Kaufman, Y.; Israelachvili, J.N.; Waite, J.H. Underwater Contact Adhesion and Microarchitecture in Polyelectrolyte Complexes Actuated by Solvent Exchange. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autumn, K.; Liang, Y.A.; Hsieh, S.T.; Zesch, W.; Chan, W.P.; Kenny, T.W.; Fearing, R.; Full, R.J. Adhesive Force of a Single Gecko Foot-Hair. Nature 2000, 405, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Lee, B.P.; Messersmith, P.B. A Reversible Wet/Dry Adhesive Inspired by Mussels and Geckos. Nature 2007, 448, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Du, J.; Wu, J.; Jiang, L. Superhydrophobic Gecko Feet with High Adhesive Forces towards Water and Their Bio-Inspired Materials. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Jiang, L. Bio-Inspired Design of Multiscale Structures for Function Integration. Nano Today 2011, 6, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autumn, Kellar. Gecko adhesion: structure, function, and applications. MRS Bull. 2007, 32, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Ge, L.; Ci, L.; Ajayan, P.M.; Dhinojwala, A. Gecko-Inspired Carbon Nanotube-Based Self-Cleaning Adhesives. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, G.; Lai, Y. A Review on Special Wettability Textiles: Theoretical Models, Fabrication Technologies and Multifunctional Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Mcadams, D.A.; Grunlan, J.C. Nano/Micro-Manufacturing of Bioinspired Materials: A Review of Methods to Mimic Natural Structures. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 6292–6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhu, X.; Yong, K.-T.; Gu, G. Stimuli-Responsive Functional Materials for Soft Robotics. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 8972–8991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, D.; Tolley, M.T. Design, Fabrication and Control of Soft Robots. Nature 2015, 521, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, T.J.; Broer, D.J. Programmable and Adaptive Mechanics with Liquid Crystal Polymer Networks and Elastomers. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, S.I.; Wood, R.J.; Majidi, C. Untethered Soft Robotics. Nat. Electron. 2018, 1, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, S.; Nakano, T.; Nozue, Y.; Kinoshita, S. Coloration Using Higher Order Optical Interference in the Wing Pattern of the Madagascan Sunset Moth. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2008, 5, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavenga, D.G.; Leertouwer, H.L.; Wilts, B.D. Colouration Principles of Nymphaline Butterflies - Thin Films, Melanin, Ommochromes and Wing Scale Stacking. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, jeb.098673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuthill, I.C.; Stevens, M.; Sheppard, J.; Maddocks, T.; Párraga, C.A.; Troscianko, T.S. Disruptive Coloration and Background Pattern Matching. Nature 2005, 434, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavenga, D.G.; Wallace, J.R.A.; Warrant, E.J. Bogong Moths Are Well Camouflaged by Effectively Decolourized Wing Scales. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziai, Y.; Petronella, F.; Rinoldi, C.; Nakielski, P.; Zakrzewska, A.; Kowalewski, T.A.; Augustyniak, W.; Li, X.; Calogero, A.; Sabała, I.; et al. Chameleon-Inspired Multifunctional Plasmonic Nanoplatforms for Biosensing Applications. NPG Asia Mater 2022, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatankhah-Varnosfaderani, M.; Keith, A.N.; Cong, Y.; Liang, H.; Rosenthal, M.; Sztucki, M.; Clair, C.; Magonov, S.; Ivanov, D.A.; Dobrynin, A.V.; et al. Chameleon-like Elastomers with Molecularly Encoded Strain-Adaptive Stiffening and Coloration. Science 2018, 359, 1509–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyssier, J.; Saenko, S.V.; van der Marel, D.; Milinkovitch, M.C. Photonic Crystals Cause Active Colour Change in Chameleons. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Bai, H. Recent Progress of Bio-Inspired Camouflage Materials: From Visible to Infrared Range. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2023, 39, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.; Berg, J.; Berg, R. Predator–Prey Interaction between a Boomslang, Dispholidus Typus, and a Flap-necked Chameleon, Chamaeleo Dilepis. Afr. J. Ecol. 2020, 58, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, J.C.; Schoeppler, V.; Merritt, D.J.; Best, C.; Maire, E.; Adrien, J.; Spaeker, O.; Janssen, N.; Gladisch, J.; Gierlinger, N.; et al. Climate-Dependent Heat-Triggered Opening Mechanism of Banksia Seed Pods. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Timonen, J.V.I.; Carlson, A.; Drotlef, D.-M.; Zhang, C.T.; Kolle, S.; Grinthal, A.; Wong, T.-S.; Hatton, B.; Kang, S.H.; et al. Multifunctional Ferrofluid-Infused Surfaces with Reconfigurable Multiscale Topography. Nature 2018, 559, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Lum, G.Z.; Mastrangeli, M.; Sitti, M. Small-Scale Soft-Bodied Robot with Multimodal Locomotion. Nature 2018, 554, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, J.C.; Spaeker, O.; Gierlinger, N.; Merritt, D.J.; Miller, B.P.; Neinhuis, C.; Fratzl, P.; Eder, M. Temperature-Induced Self-Sealing Capability of Banksia Follicles. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2018, 15, 20180190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ertekin, E.; Wang, T.; Cruz, L.; Dailey, M.; DiRuggiero, J.; Kisailus, D. Mechanism of Water Extraction from Gypsum Rock by Desert Colonizing Microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 10681–10687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, T.; Perez-Fernandez, C.; DiRuggiero, J.; Kisailus, D. Iron Acquisition and Mineral Transformation by Cyanobacteria Living in Extreme Environments. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 17, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Hogan, A.; Deheyn, D.D.; Koch, M.; Nothdurft, B.; Arzt, E.; Meyers, M.A. On the Nature of the Transparent Teeth of the Deep-Sea Dragonfish, Aristostomias Scintillans. Matter 2019, 1, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).