Submitted:

12 May 2023

Posted:

16 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Definition of Concepts

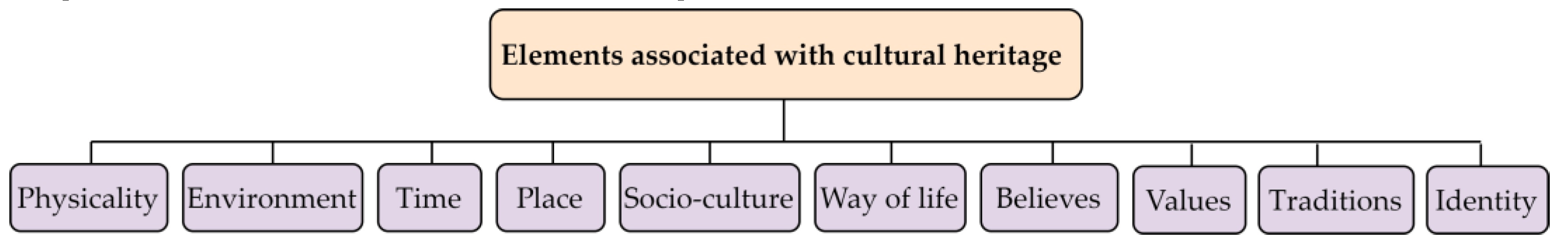

2.1. Cultural Heritage

2.1.1. Definition of Cultural Heritage

2.1.2. Approaches to the Concept of Heritage

- Heritage as a set of valuable objects, this approach emphasized on the tangible heritage, such as architecture, work of arts that belong to the past. At the 2000s emphasize is directed towards intangible aspects of heritage.

- Heritage as a part of the environment. This approach is focusing on the sustainable connection between heritage and environment. Depending on the specific heritage, the environment can mean places, territories, landscapes, other objects, as well as the entire living environment more generally, in either the physical or intangible sense.

- Heritage as a socio-cultural construct, this approach is related to the social and cultural aspects of heritage. Heritage no longer dealt as an object related to a certain environment. There are also socio-cultural aspects that relate to heritage. This new approach is called (new heritage) [9].

2.1.3. Heritage as a Sustainable Process

2.1.4. Heritage as Identity

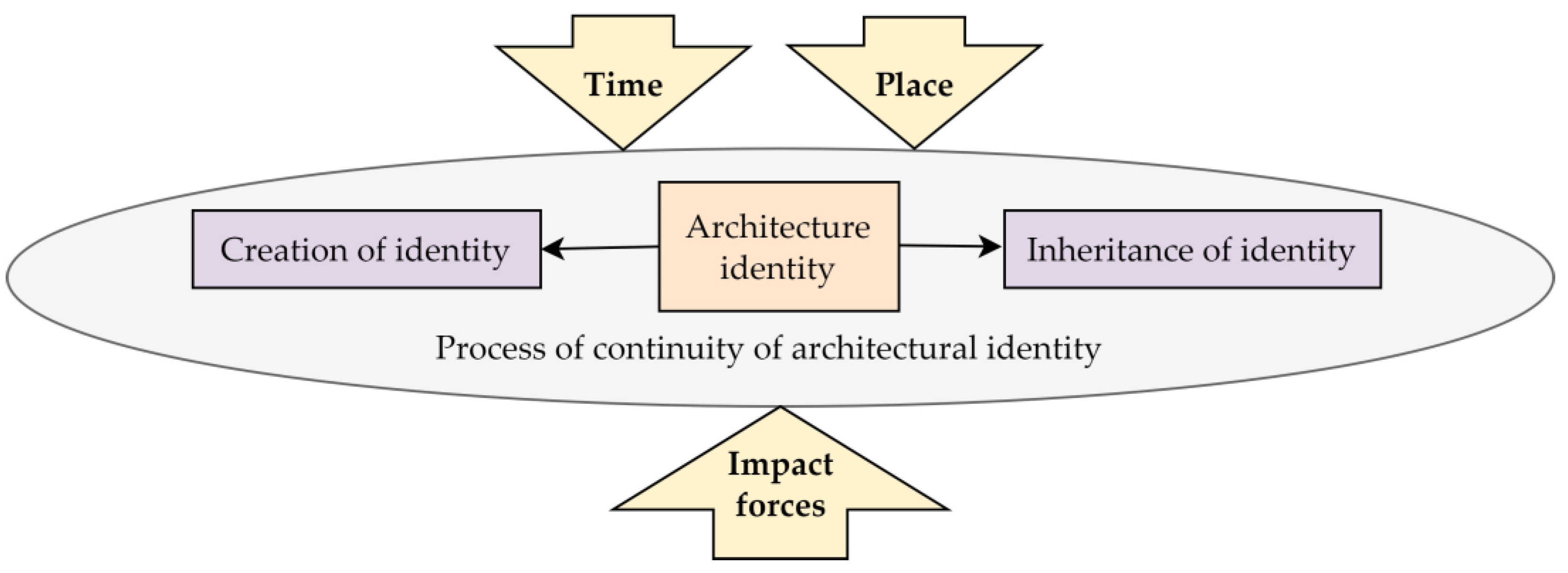

2.2. The concept of Identity

2.3. Architecture Identity

2.3.1. Architecture Identity as a Concept

2.3.2. Identity and Time (Architecture Identity as a Continuous Process)

2.3.3. Identity and Place (Architecture Identity and Context)

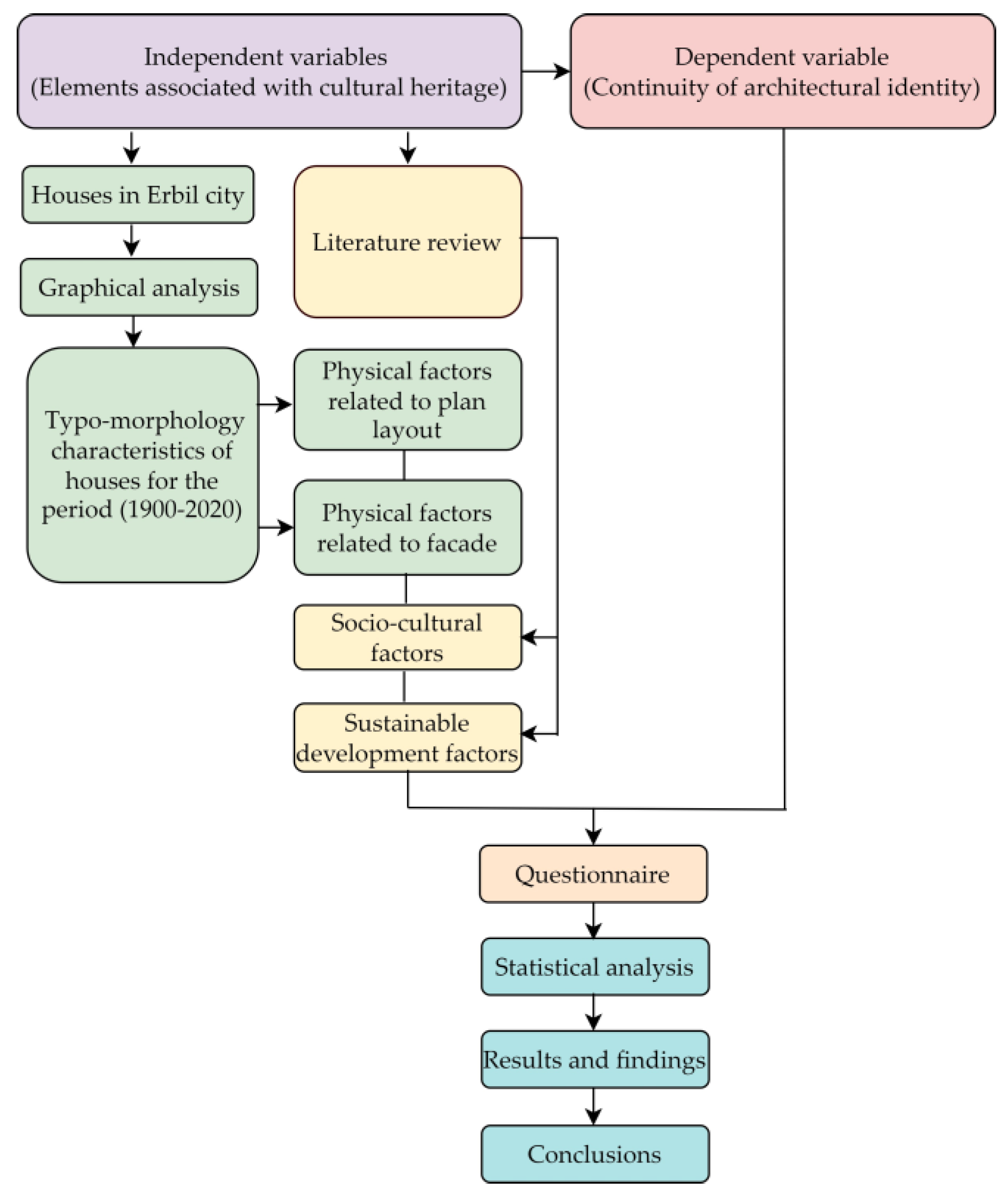

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Objectives and Research Steps (Implementation Matrix)

3.2. Step one: Developing a Framework for Typo-Morphologies of Houses in Erbil City for the Period (1900-2020)

3.2.1. Typology in Architecture

3.2.2. Morphology in Architecture

3.2.3. Typo-morphology in Architecture

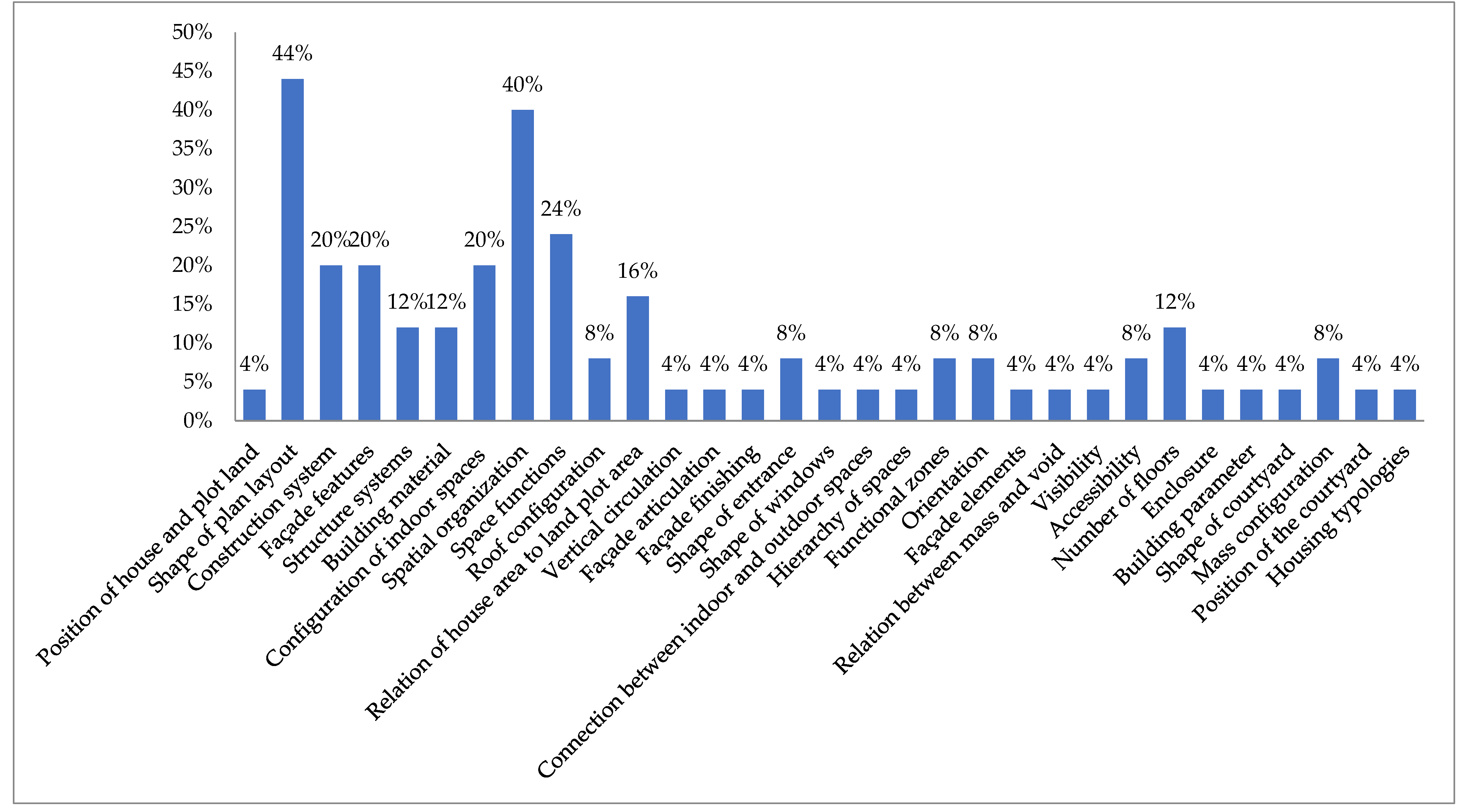

3.2.4. Analysis of Previous Studies Related to Typo-Morphology of Houses

3.2.5. Sampling and Typo-Morphology Analysis for Houses in Erbil City

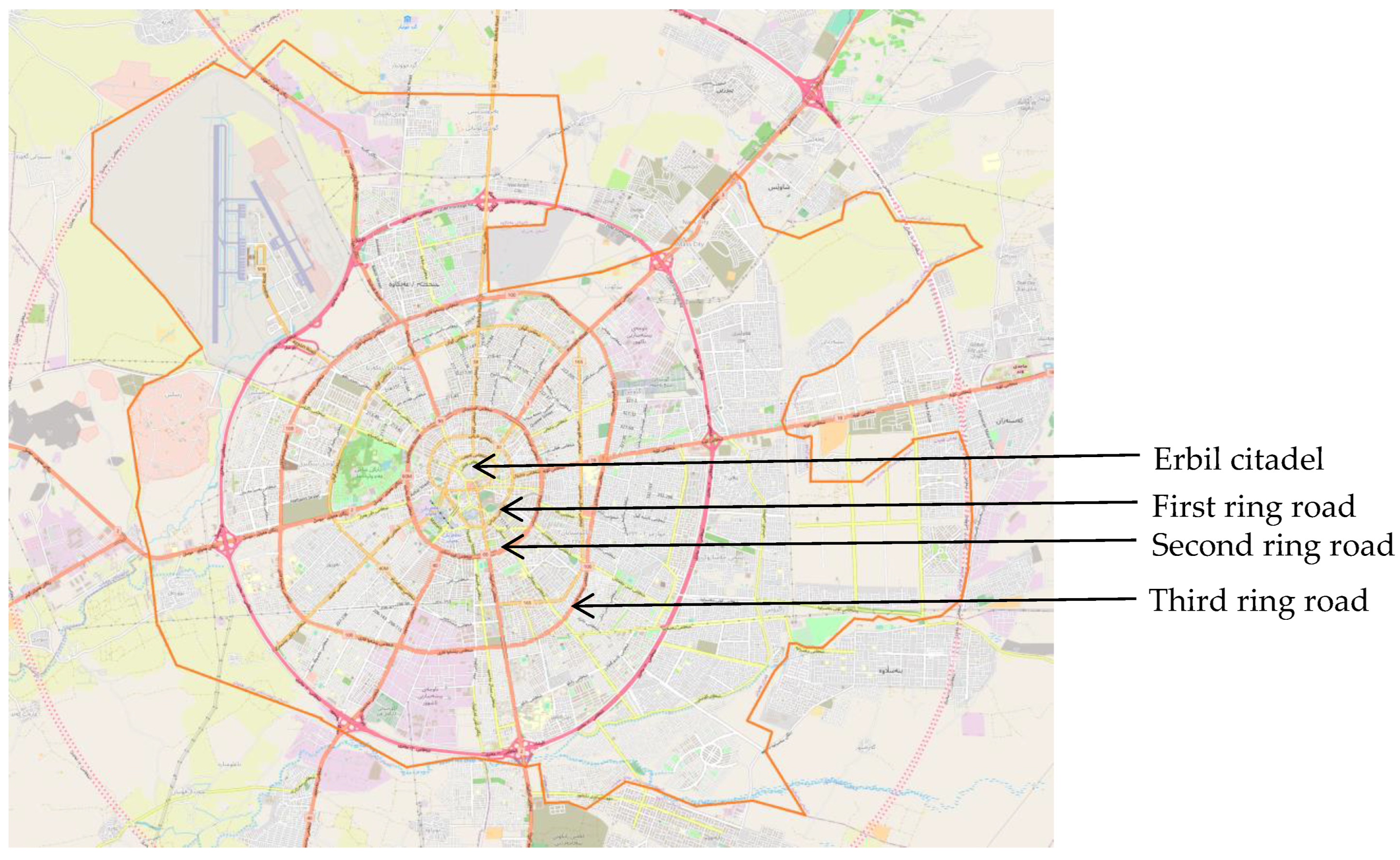

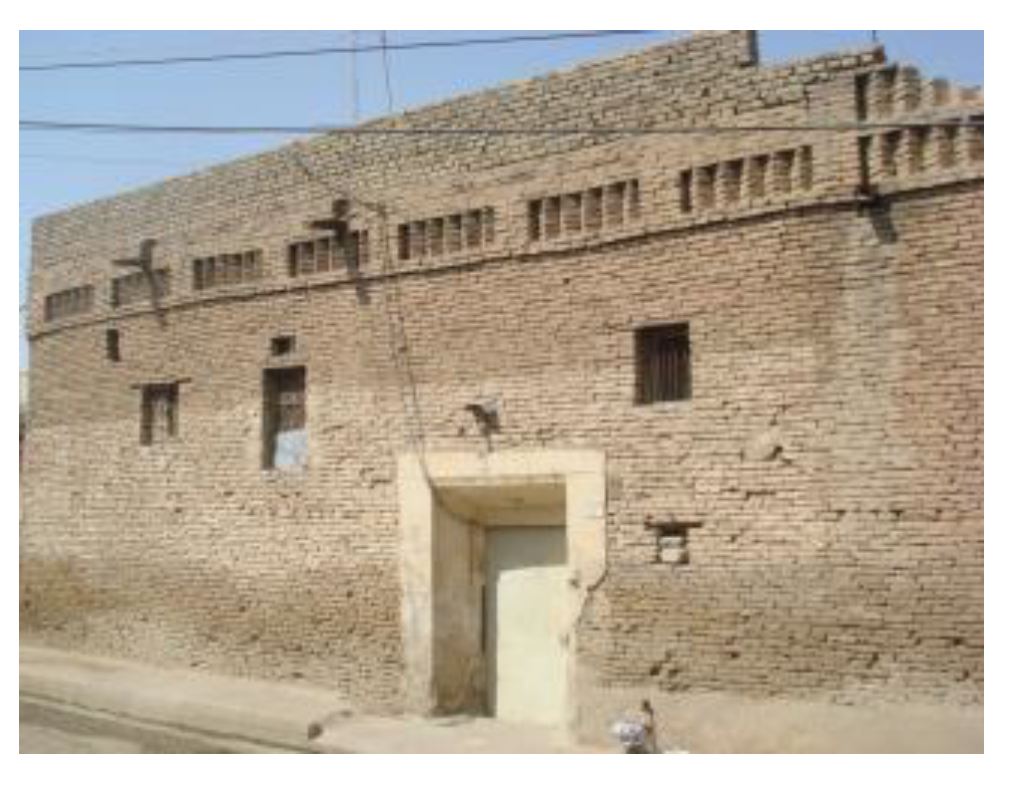

- (1900-1929), this period represents the traditional houses; they are mainly located in Erbil citadel

- (1930-1959), this period represents the beginning of modern houses with keeping traditional house features; they are mainly located inside the first ring road that surrounds the citadel.

- (1960-1989), this period represents modernity in house features; they are located between the first ring road and the second ring road.

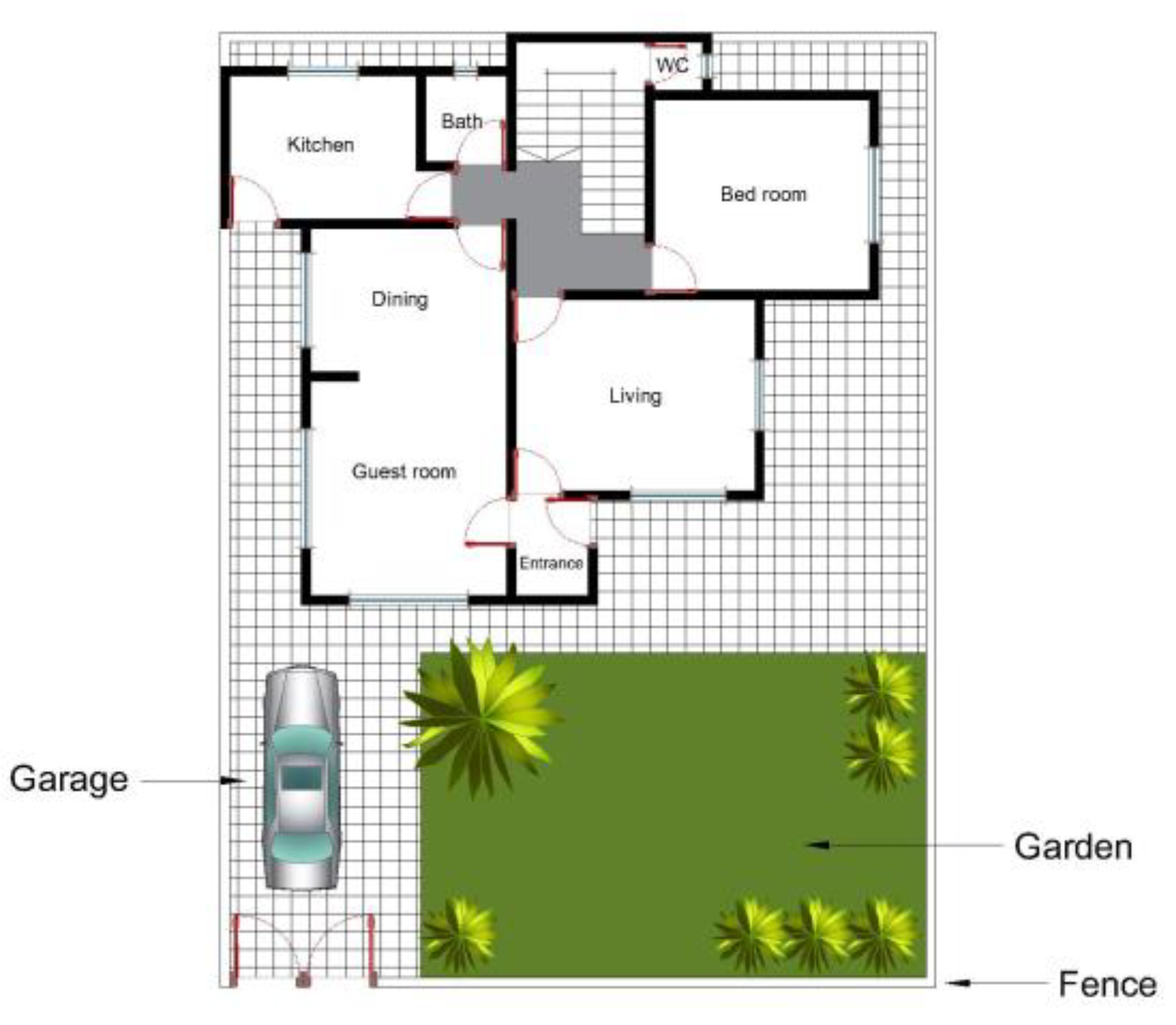

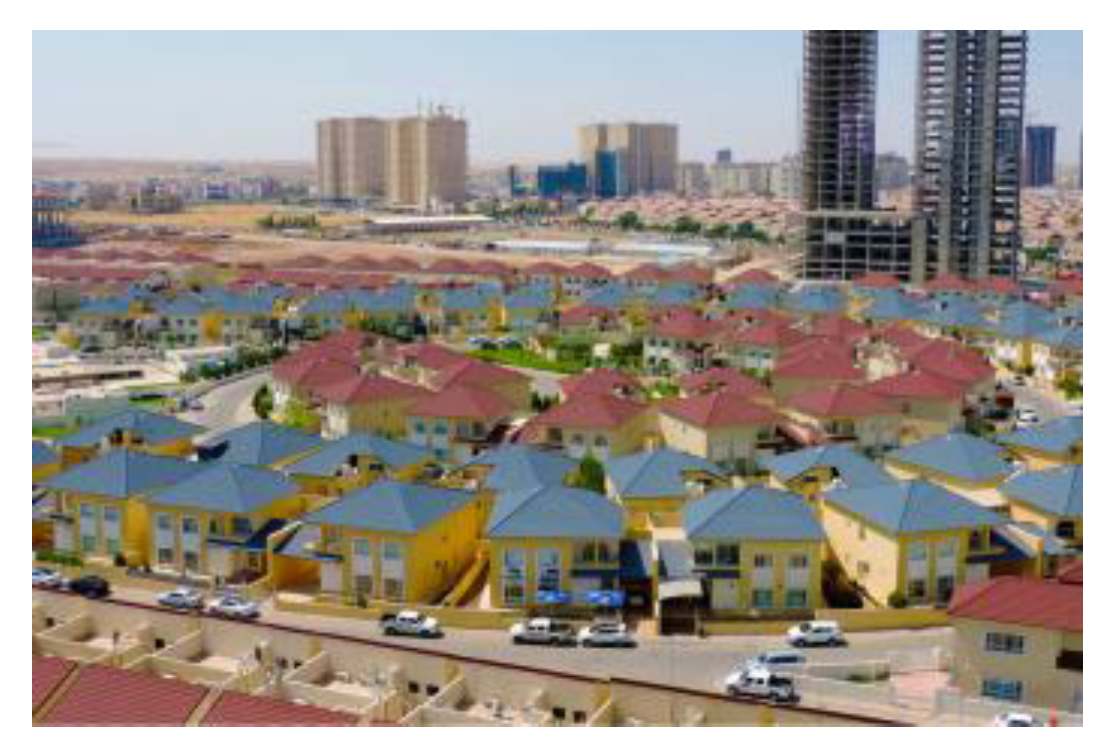

- (1990-2020), this period represents contemporary design features in houses; they are located between the second ring road and the third ring road (Figure 5).

3.2.6. Criteria for Sample Selection

3.2.7. Sampling Method

3.2.8. Data Collection

- Conducting a site survey to gather information through measurements and photographs.

- Paying visits to official organizations in Erbil city, such as the municipality and the High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalization (HCECR), to obtain data, particularly the construction dates of sample structures and some original design sketches of house samples.

- During the survey, conducting brief interviews with homeowners to gather information on the construction dates of their houses and to check whether any alterations have been made to the original structure.

3.2.9. Typo-Morphology Analysis Procedure

3.2.10. Findings of Typo-Morphology Analysis

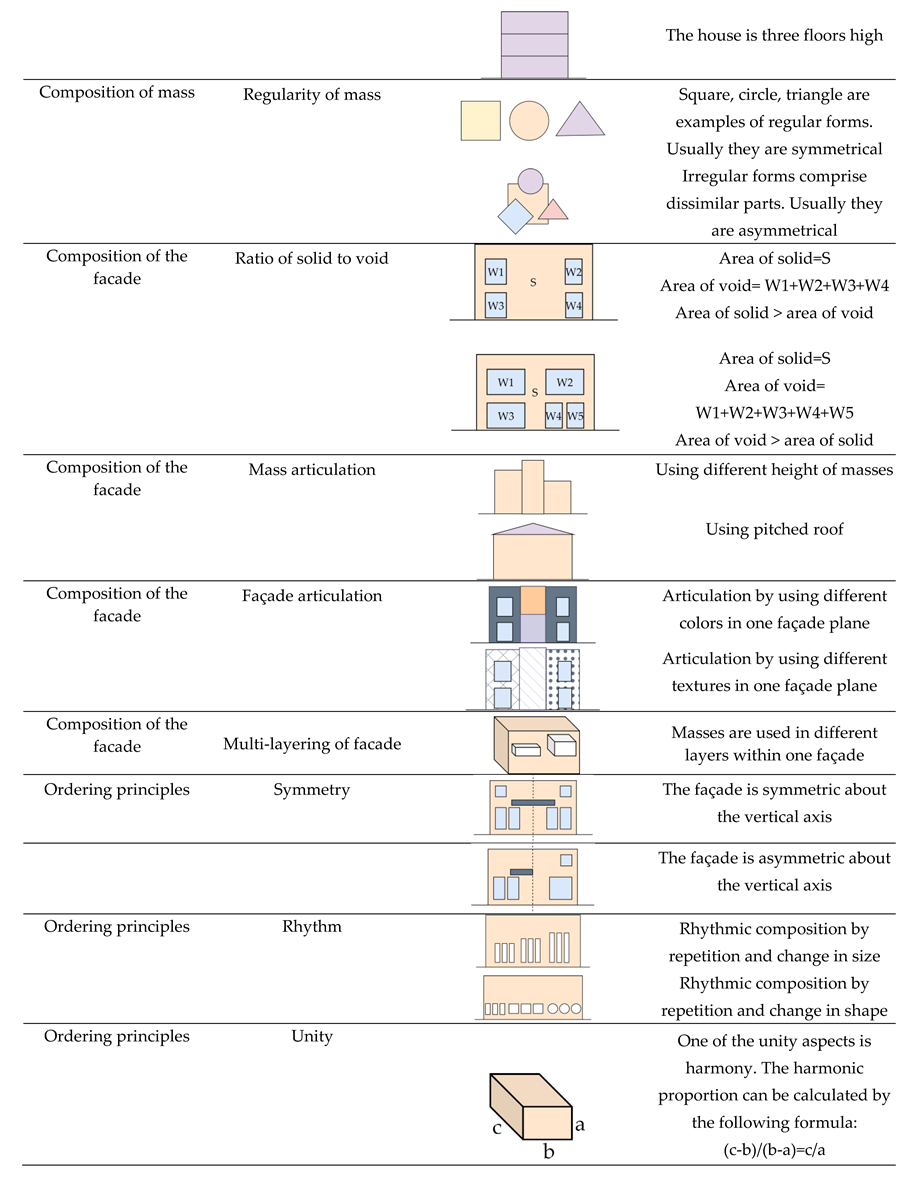

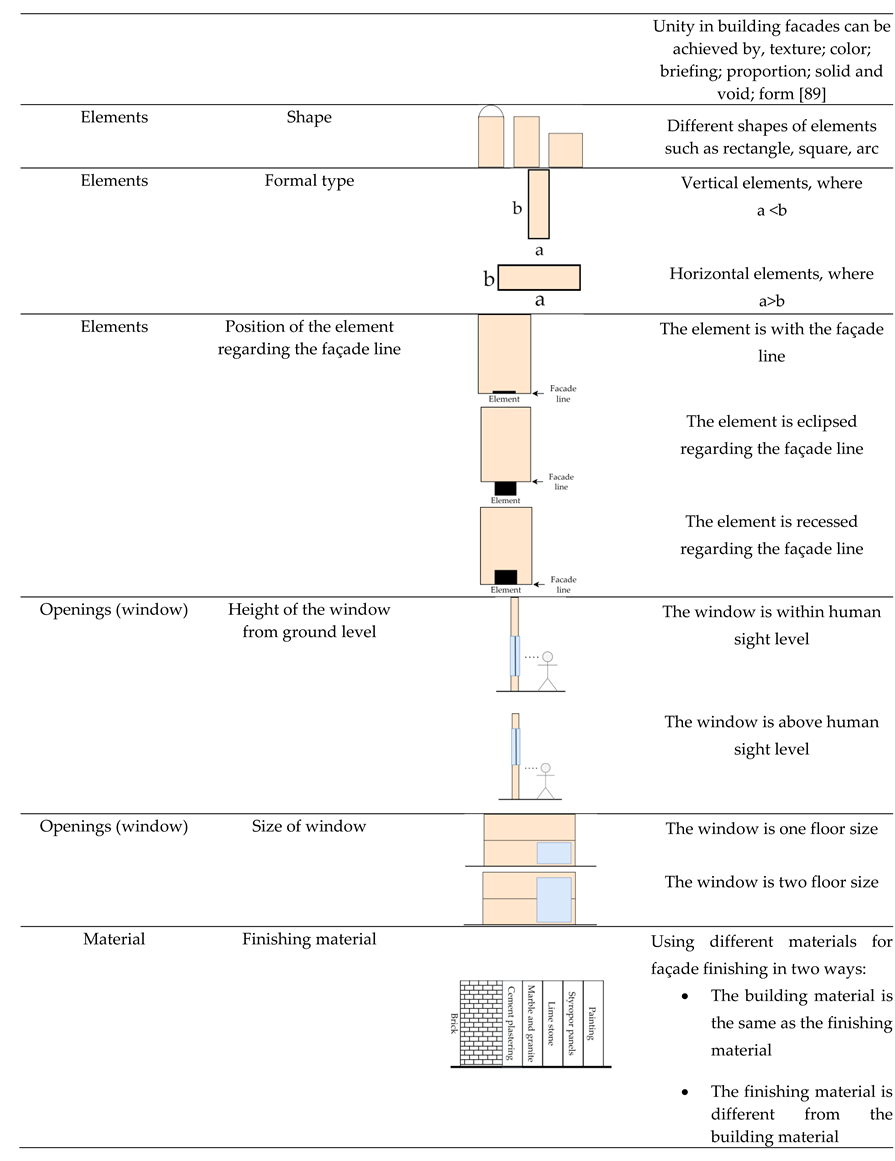

- Composition of mass

- Composition of the façade

- Ordering principles

- Façade elements

- Openings

- Material

- Color

3.2.11. Findings and Discussions of Step One

- -

- The British occupation of Iraq in 1917 and the subsequent establishment of the first Iraqi national government on August 23, 1923 marked the start of a sequence of cultural, social, and technological transformations [90].

-

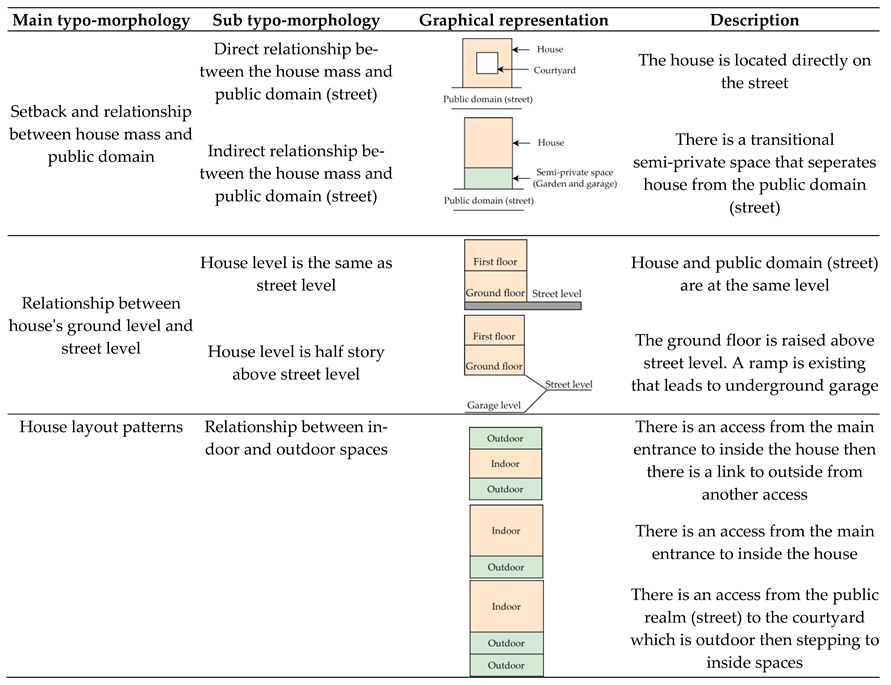

Factor of house ground level regarding the street level, two types are recognized:

- -

- The house is on the same level with the street.

- -

- The ground level is elevated by half or one floor, with a ramp leading to semi-underground areas that typically serve as garages and storage spaces, this is mainly found in the period (1990-2020)

-

Factor of house layout patterns, includes the following items:

- -

- Relationship between indoor and outdoor spaces, including three types:

- o

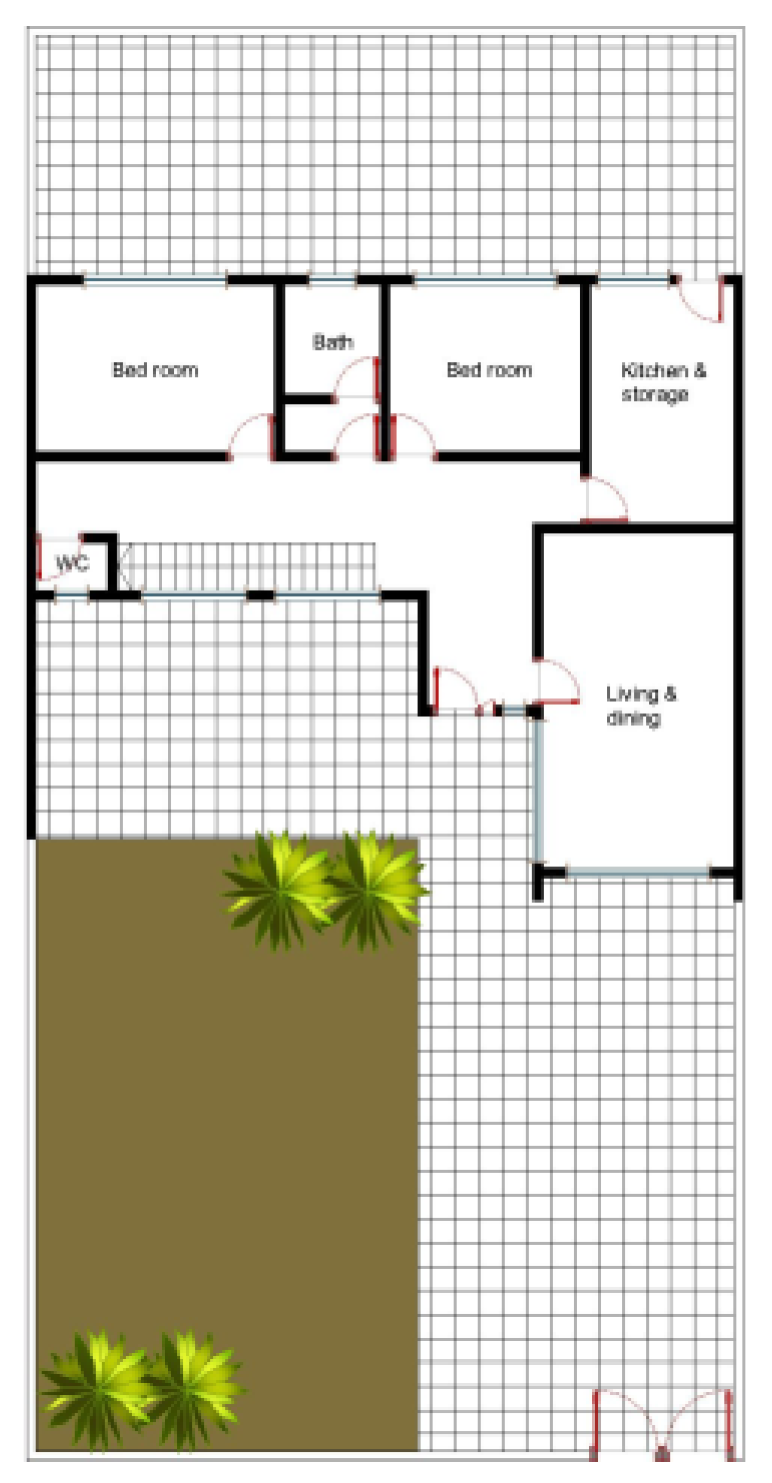

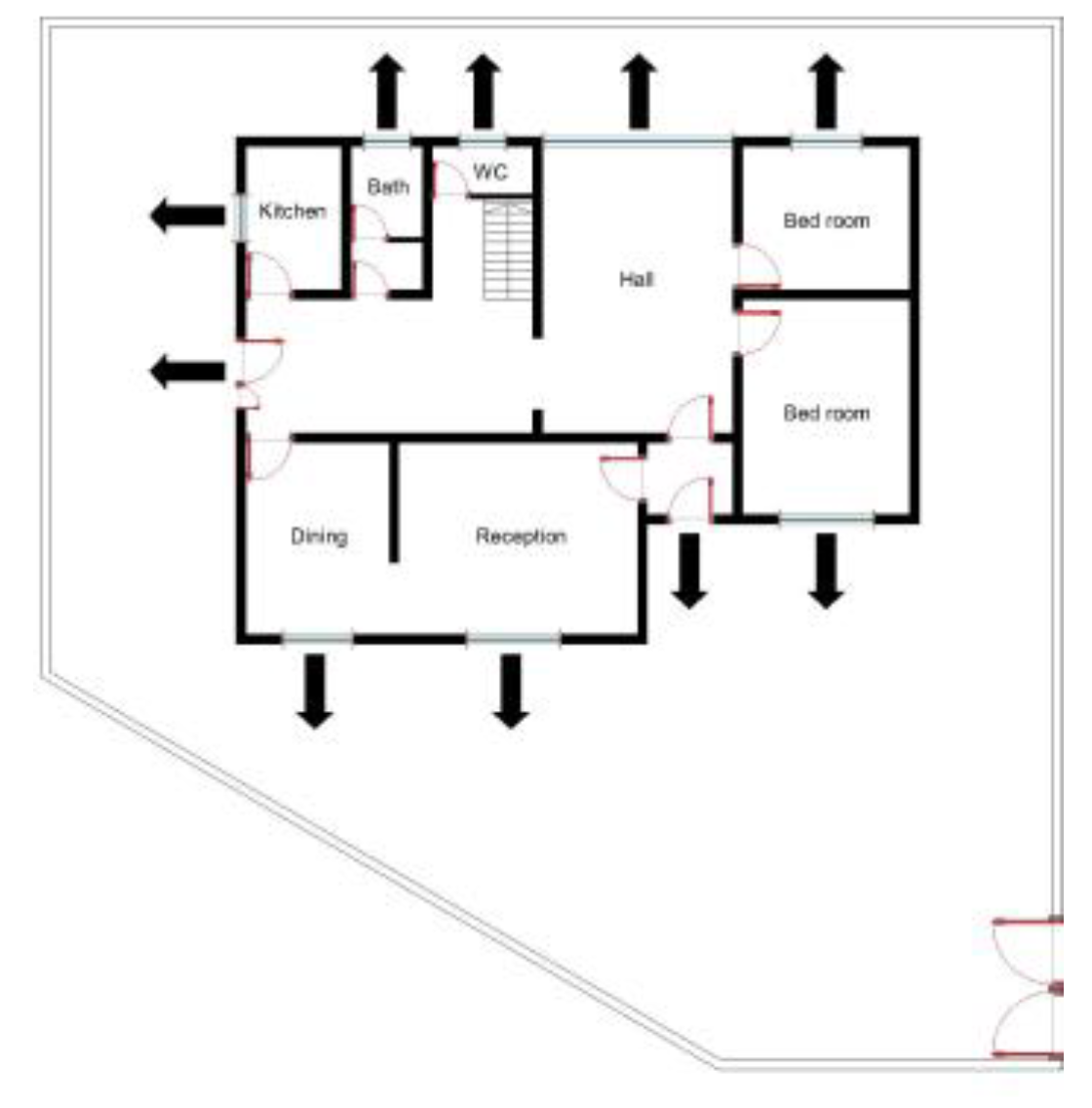

- There is access in the front of the house that leads to indoor spaces then there is another access at the back that leads to outdoor space, this is mainly found in houses with backyards (Figure 8).

- -

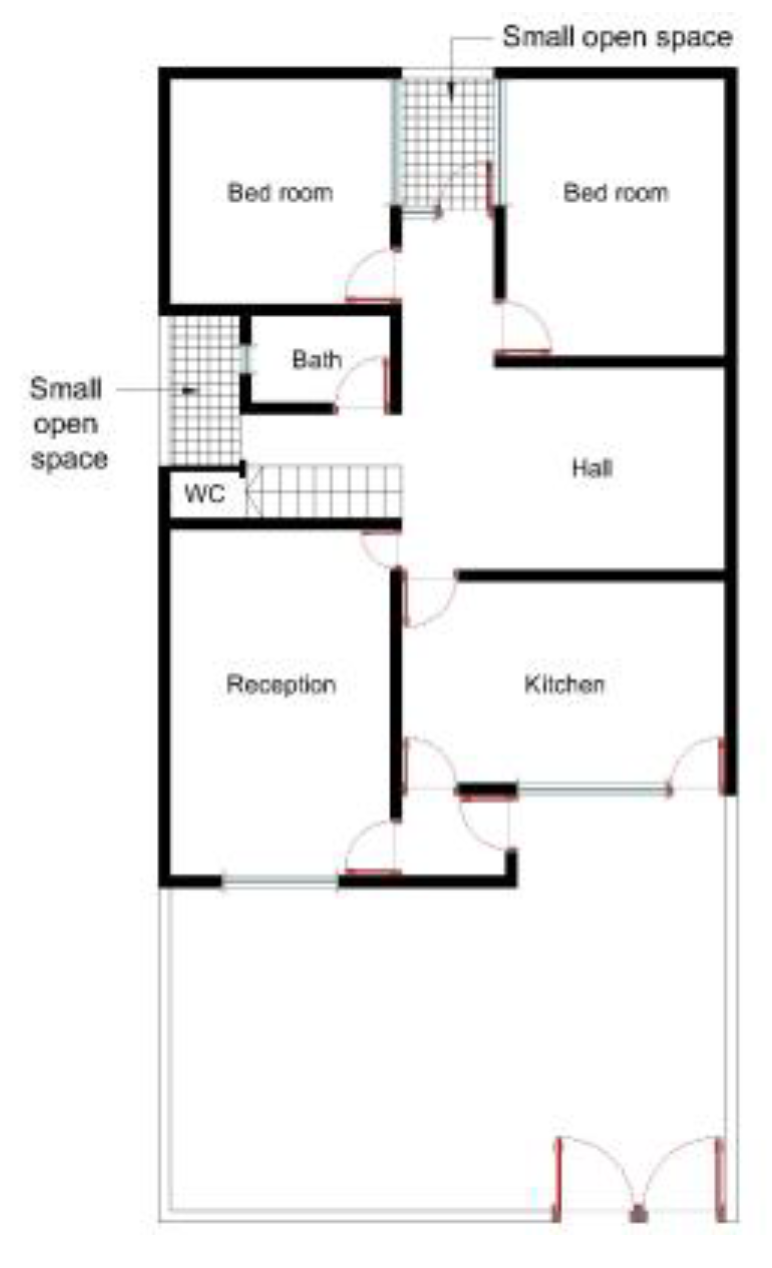

- There is access in front of the house that leads to indoor spaces, in this type usually there is no open space at the back of the house, and it includes small open spaces for natural lighting and ventilation (Figure 9).

- o

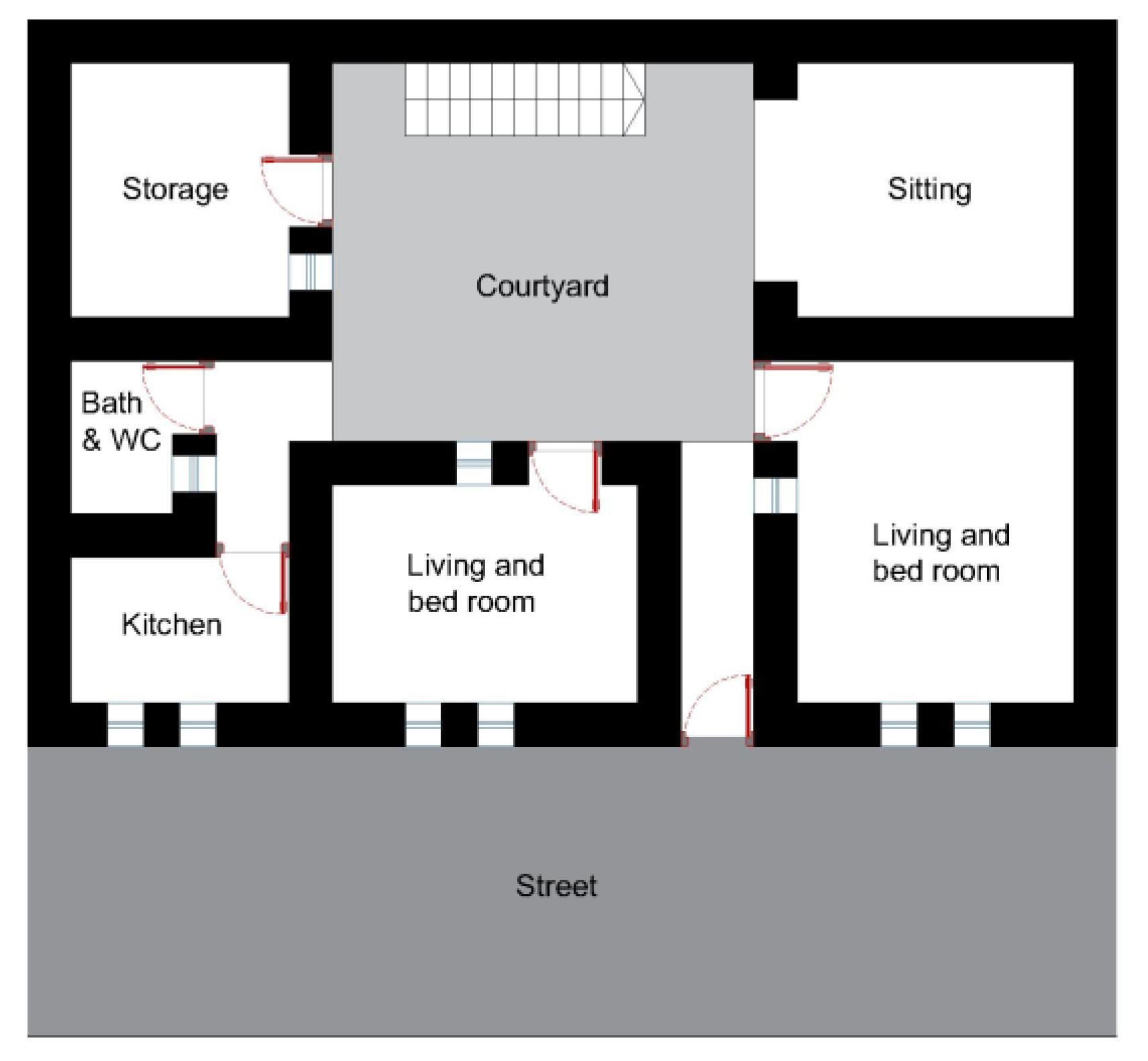

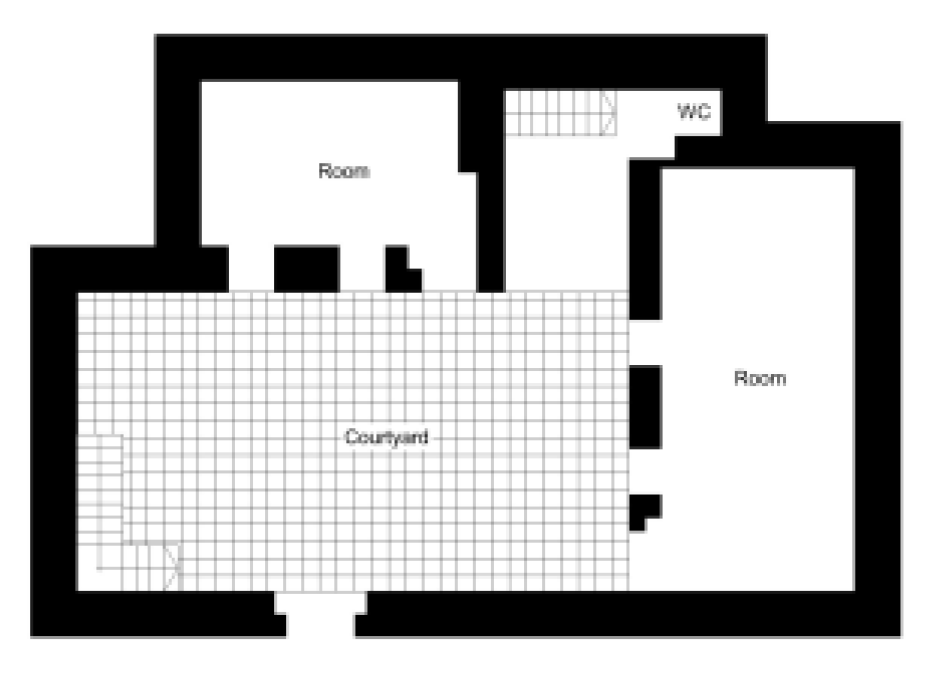

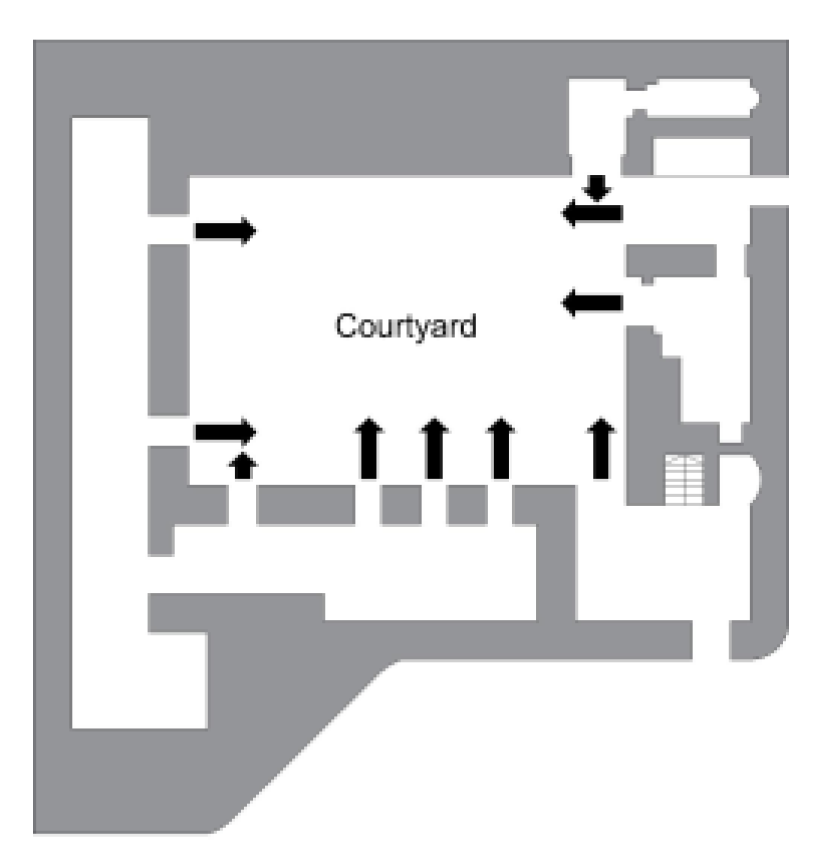

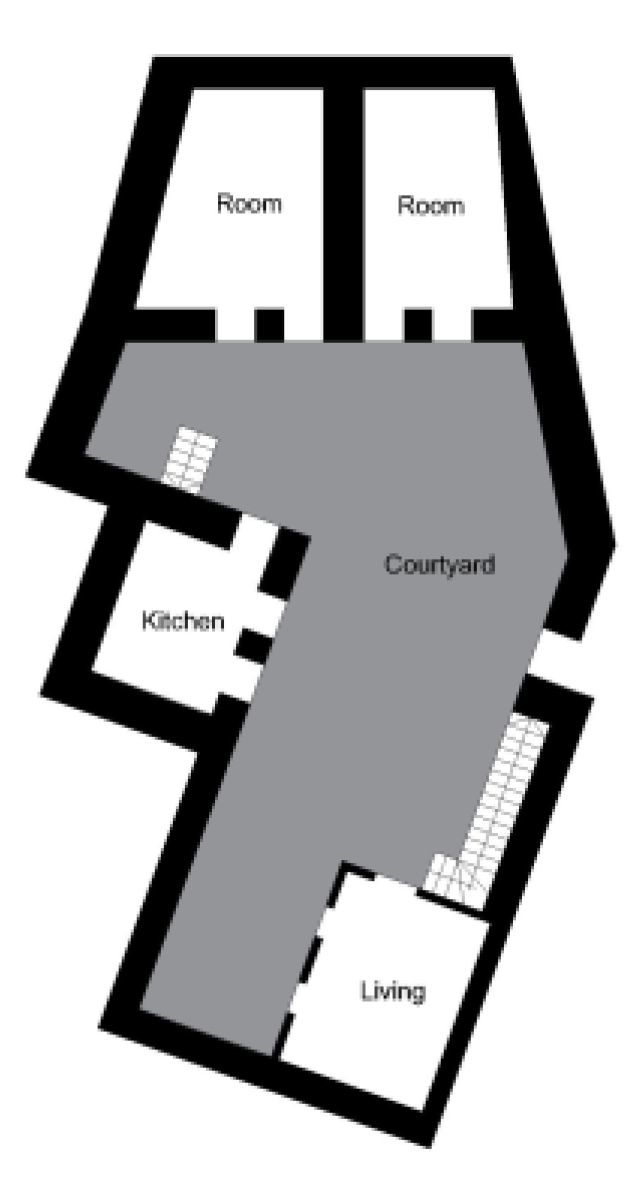

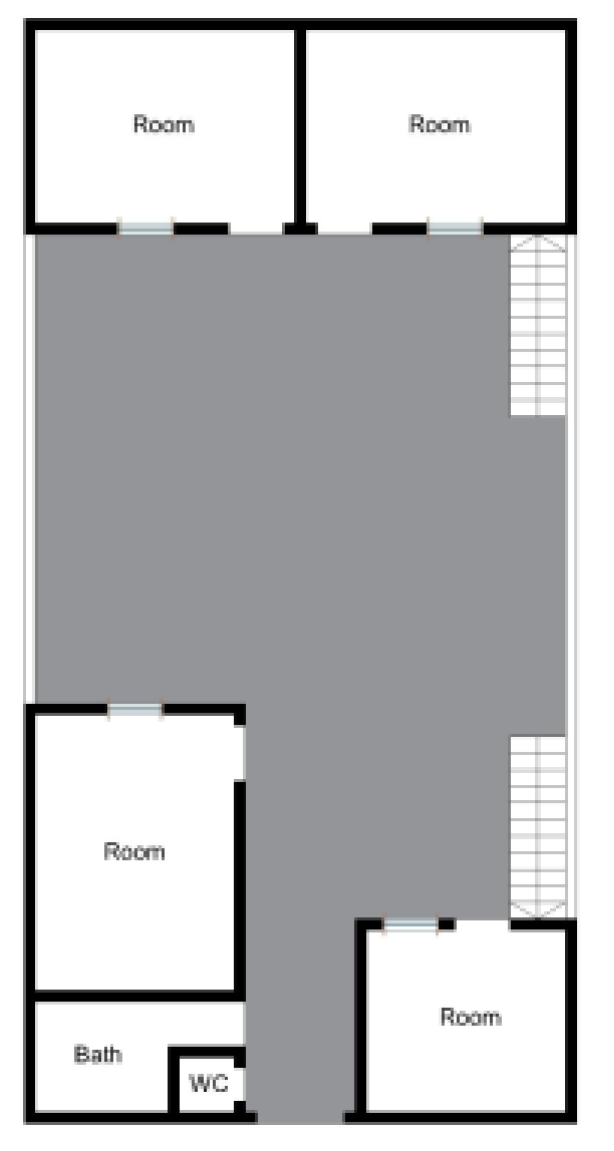

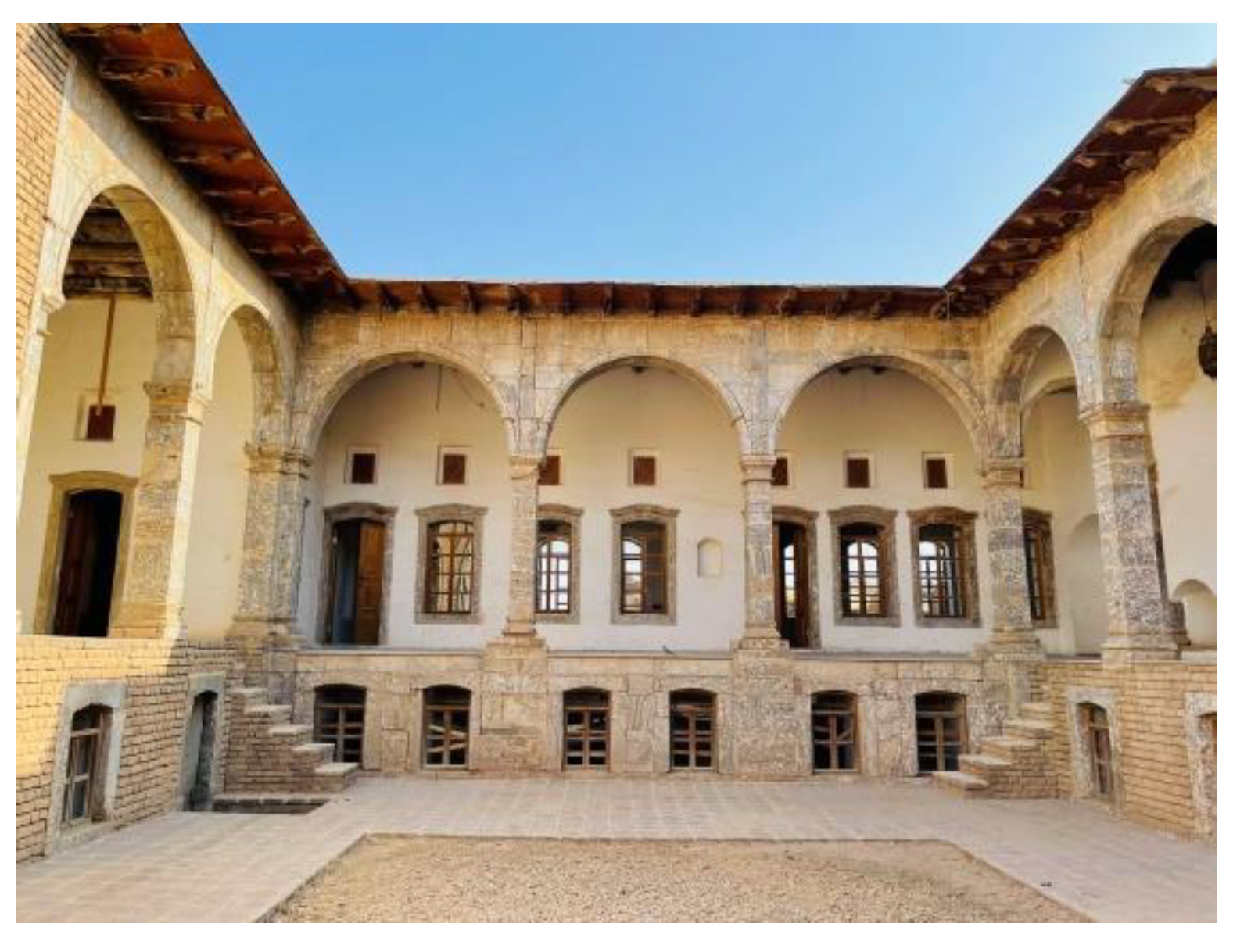

- Stepping from public domain which is an open space to another open space which is usually courtyard, then having access to indoor spaces, this is mainly found in courtyard houses of the period (1900-1929) (Figure 10).

-

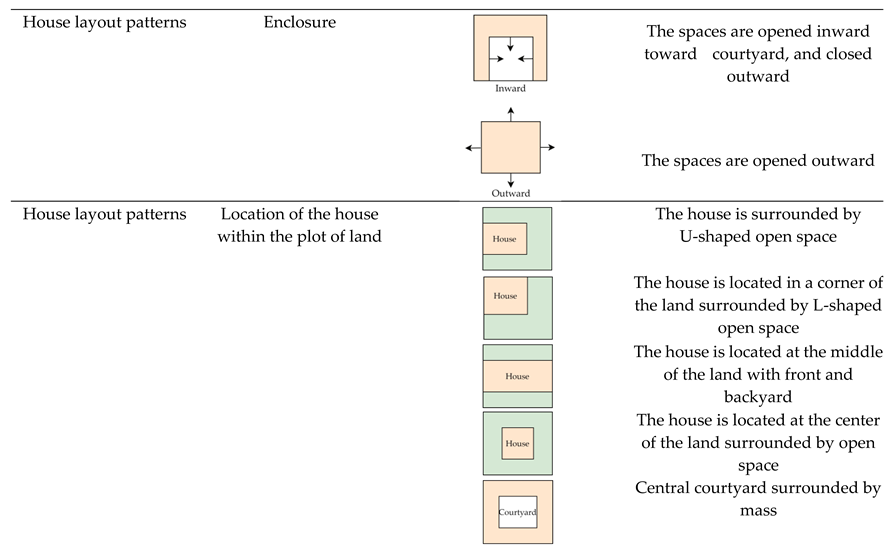

Enclosure, includes two types:

- The location of the house within the land plot is classified into 11 types, indicating a wide range of possibilities for how the house is situated within the borders of the plot. For example, in courtyard houses, the house covers the entire plot of land, while in houses with a setback, there is open space remaining within the plot.

-

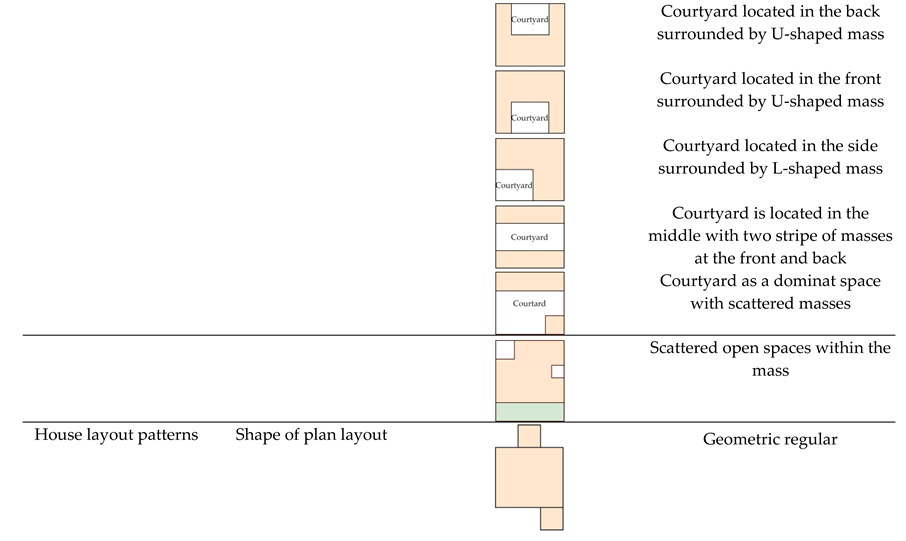

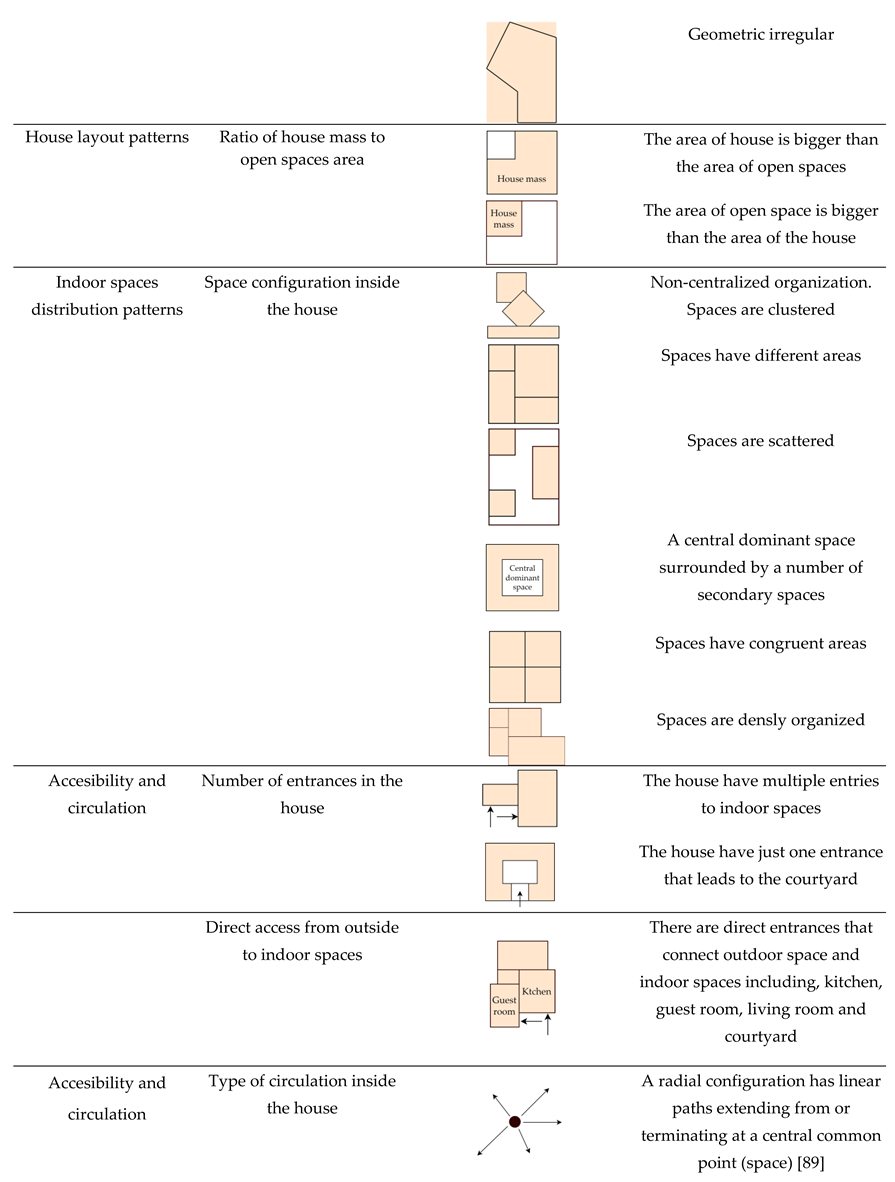

Shape of plan layout, includes two types:

- -

- This typology pertains to house plans with irregular geometrical shapes, which are commonly seen in traditional urban areas where the houses are designed to conform to the irregular and winding pathways and alleys in the area. [85] Houses of this type could be found in the areas inside first ring road in Erbil (1900-1929) (Figure 13).

- -

- Houses with a plan that has a regular geometrical shape are often seen in modern urban areas where the plots are arranged in a grid pattern. Although, for design, orientation, or social reasons, such houses may have some irregularly shaped parts.

-

Ratio of house mass to open spaces area, includes two types:

- -

- When the house has a larger built-up area compared to the open space, it is usually observed in houses built on relatively small plots of land where most of the land is utilized for the built-up area (Figure 14).

- -

- When the house has a smaller built-up area compared to the open space, it is usually observed in houses built on relatively large plots of land in the periods (1930-1959) and (1960-1989) (Figure 15).

-

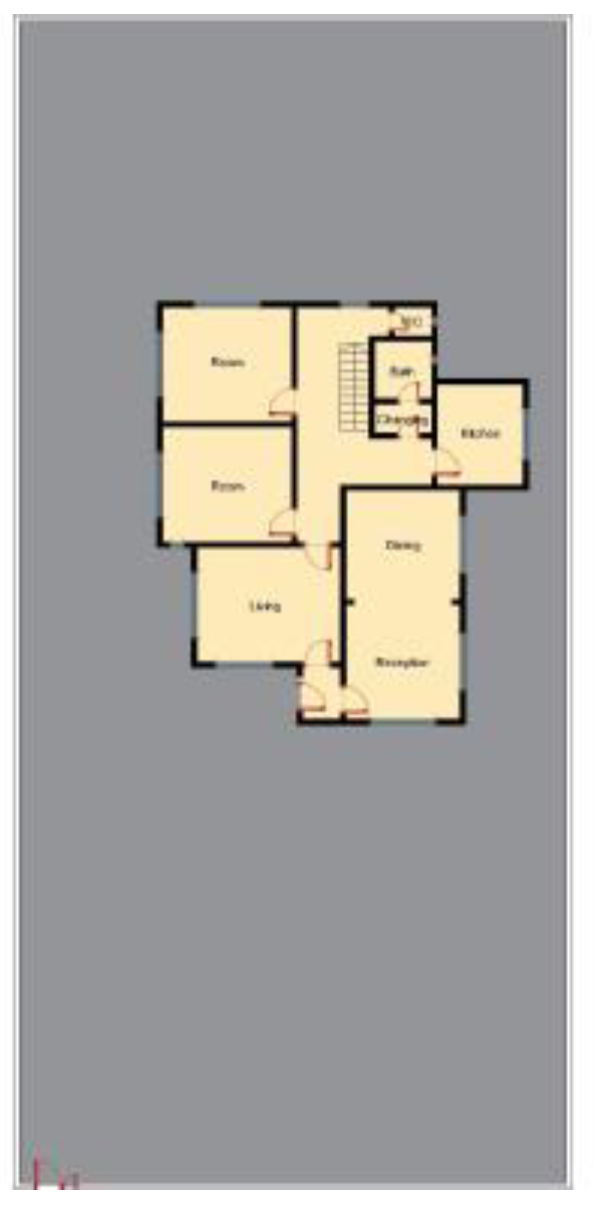

Indoor spaces distribution patterns, includes the following variables:

- -

- Space configuration inside the house, includes six types of arrangement and relation:

- o

- Centralized indoor spaces are typically found in courtyard houses, where the central courtyard serves as the focal point for activities.

- o

- Non-centralized indoor spaces lack a central area of focus.

- o

- Scattered spaces can be found in courtyard houses, particularly those from modern periods (Figure 16).

- o

- Spaces are densely organized with small open spaces between them.

- o

- Spaces being of equal size are a rare occurrence as different functions demand varying sizes of spaces.

- o

- Different sizes of spaces are commonly found in samples.

-

Accesibility and circulation, includes:

- -

- Number of entrances from outdoor to indoor spaces. Two types are found. In the first type the house has only one entrance, which directly leads to the courtyard of the house or in an inclined path for privacy purposes. This is commonly observed in courtyard houses. The second type has multiple entrances leading to various indoor spaces such as guest room, living room, and kitchen.

- -

- Two types of circulation patterns are noticed, radial circulation is found in houses with dominant central space. Network circulation combines between points in the space in the shape of an intersected web. [89]

- Location of vertical circulation (staircase) in the house. Three types are recognized, at the front, middle and back part of the house.

-

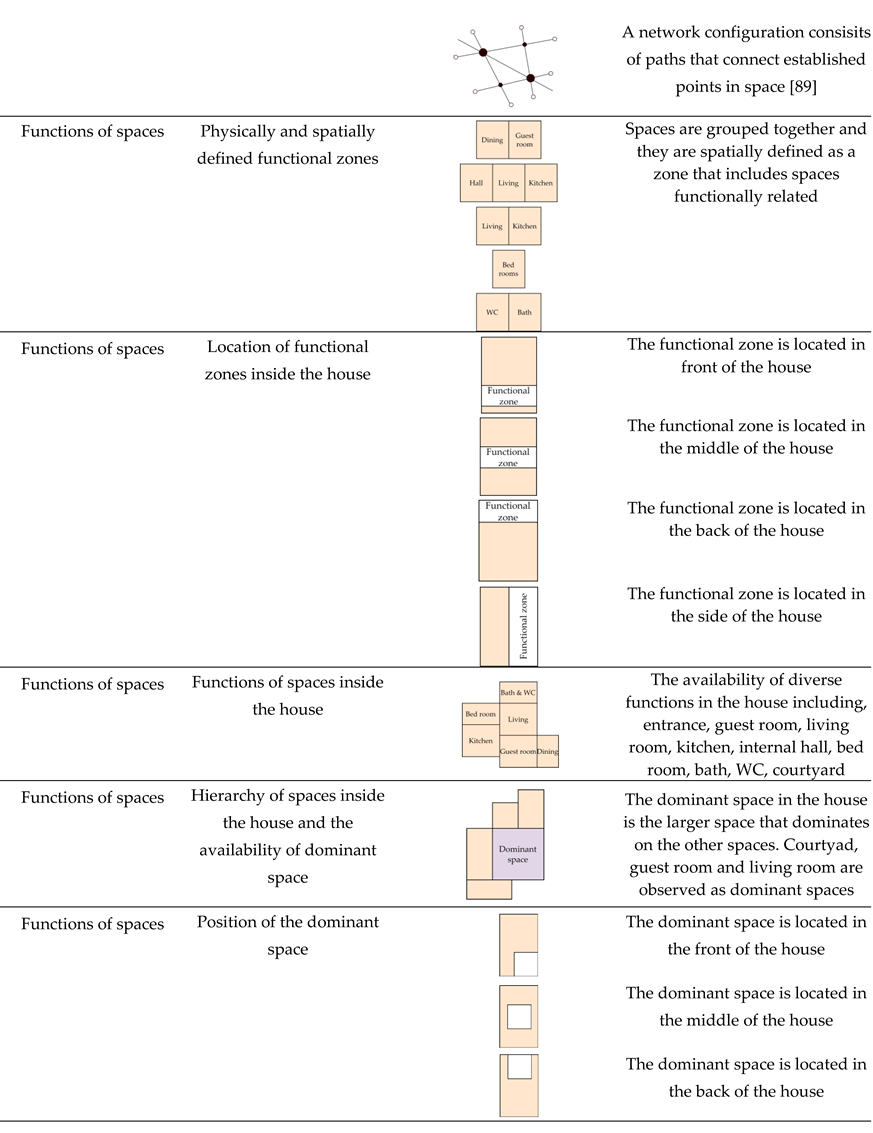

Functions of spaces, include the following:

- -

- Five types of functional zones are noticed in the samples, each representing a physical and direct relationship between spaces that are grouped based on the following aspects:

- o

- Privacy, including the separation between genders and strangers with family members, for instance isolating guest room and dining from other parts of the house. With the guest room having direct access from the outside. Bed rooms also grouped in one zone usually located at the back of the house (Figure 17).

- o

- Family daily life, this includes spaces that are frequently used by family members, such as zone of living and kitchen.

- o

- Service spaces, this type of zone is mostly includes spaces that are serving the family members, such as bath, WC and storage.

- -

- Location of functional zones inside the house. Three types are recognized, the zone is located at the front, middle and the back part of the house. The location of the zone is influenced by above mentioned items of privacy, family daily life and service.

- -

- Functions of spaces inside the house. In the process of analysis for the selected house samples, the paper recognized the following spaces:

- o

- An entrance can refer to either a passageway that leads to interior areas or simply a doorway that provides direct access to the interior from the outside.

- o

- Courtyard, a main space in open courtyard houses, it is the center for daily family activities, in some samples they are including greenaries and fountains.

- o

- Multi-purpose room, in traditional houses usually a room have more than one function, for example the same space is used for sitting and dining and at the night it will become a bed room. For that it is not possible to recognize the specific functions of the spaces.

- o

- Guest room, it is usually used for guests and strangers, having its own entrance.

- o

- Dining room usually connected with the guest room. Mostly this space is used for serving food for guests.

- o

- Living room is used for family members gathering, in some samples it has a direct access from outside.

- o

- Kitchen, it is usually used for cooking and sometimes for family dining and even sitting.

- o

- Interior hall, it is a central space in the house, surrounded by other interior spaces, usually used for family gathering and sitting. In some examples, staircase is located in this space.

- o

- Bed room, including bed room for parents and bed rooms for children. Usually located at the back of the house for privacy.

- o

- Bath and WC, commonly they are separated in two different spaces; in some houses they are within one space.

- o

- Storage, mostly linked with kitchen, it is used for storing dry food or house stuff.

- -

- Dominant space, it is the largest space in the house; usually the courtyard is a dominant space in courtyard houses. In some modern samples the guest room and living room are dominant spaces in the house.

- -

- Position of the dominant space, it is located in the front, middle or back of the house.

-

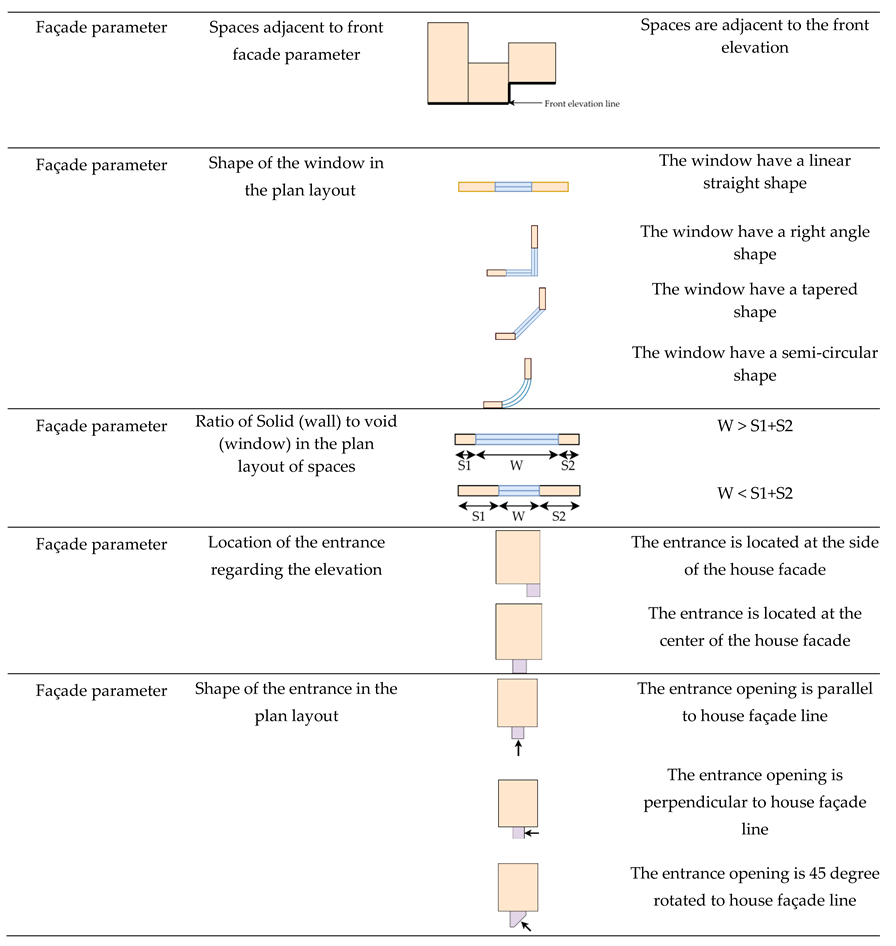

Façade parameter, includes the following variables:

- -

- Spaces adjacent to front facade parameter. Samples show that spaces are differ in their location on the front façade, mostly guest room, living, kitchen are observed.

- -

- Shape of the window in the plan layout, four types are recognized, straight, right angle, tapered and round.

- -

- Ratio of Solid (wall) to void (window) in the plan layout of spaces, two types are recognized, the first when the total length of wall adjacent to façade is larger than the total length of window or vice versa. This type differs according to the function of the space and view to outside spaces.

- -

- Location of the entrance regarding the elevation, two types are found. The entrance is located at the center of the façade, or at the side. When it locates at the center, then it leads to more than one space, but if it is located at the side of the house usually it leads only to guest room. In courtyard houses the entrance is located to the side of the courtyard or having an inclined path in order to trap visibility from outside to the courtyard.

- Shape of the entrance in the plan layout, three types are observed, even the doorway of the entrance is parallel to the façade line, or perpendicular or tapered. This orientation is related to privacy and the view of interior spaces from outside.

-

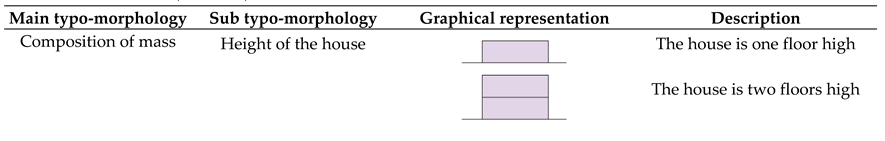

Composition of mass, includes the following variables:

- -

- Height of the house, three types are observed, one floor, two floors and three floors. The latter includes a service floor, ground floor and upper floor.

- -

- Regularity of mass, two types are found. Masses are regular in form comprising of basic geometrical shapes (Figure 18), or the masses are irregular in shape.

-

Composition of the façade, includes the following variables:

- -

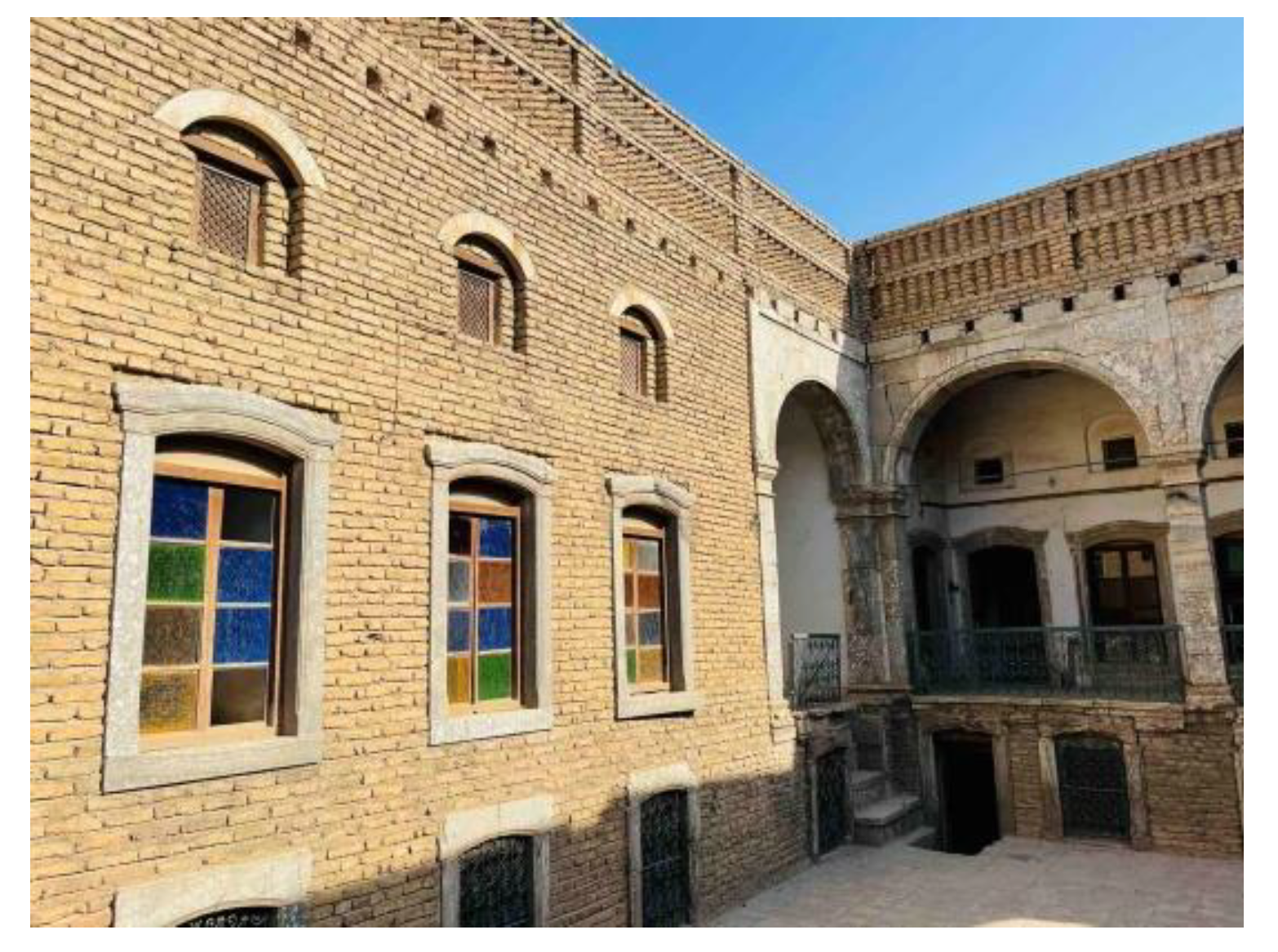

- Ratio of solid to void. In some examples the area of solid (wall) is bigger than the area of void (window). This is related to socio-cultural factors especially the factor of privacy and the visibility of indoor spaces from outdoor. Also the desired view from inside to outside. It is noticed that the traditional houses with direct relationship to street, usually have small size windows (1900-1929) Figure (19). With the advance in technology and the change in way of life, windows became larger.

- -

- Mass articulation even by using different mass heights or using pitched roofs. (Figure 20)

- -

- Façade articulation by using different colors in the same façade or using different textures of different materials within one façade.

- -

- Multi-layering of façade means that the façade comprises of multiple connected masses used in different layers.

-

Ordering principles, includes the following variables:

- -

- Symmetry, it is observed that facades are even symmetric about the facades vertical axis (Figure 21), or they are unsymmetrical.

- -

- Rhythm, this is achieved by repetition and change in size of elements in the façade, or repetition and change in shape. (Figure 22)

- -

- Unity of mass and façade. The effective features are texture; color; briefing; proportion; solid and void; form.

-

Elements of the façade. The elements that are found in the samples are entrance, window, balcony, canopy, overhang, columns, and ornaments. The analysis of those elements are conducted through the following variables:

- -

- Shape of façade element, rectangular, arches and curves are observed.

- -

- Formal type of façade element, two types is recognized, horizontal and vertical element.

- -

- Position of the element regarding the façade line. Three types are observed, the element with the elevation line, eclipsed element and recessed element (Figure 23).

-

Openings, includes the following elements:

- -

- Height of the window from ground level. Two types are noticed, the height of the window is the same level of human sight. The height of the window is above human sight level. The latter can be seen in courtyard traditional houses where the house is directly located on the street, raising window traps visibility of indoor spaces from outside.

- -

- Size of the window. In traditional houses the size of windows that located on the front façade is relatively small, while windows that located on the inner courtyard are bigger, due to increasing privacy and reducing visibility. In the modern design houses, window size became bigger, in some examples it expanded to two floors.

- Finishing materials. It is noticed that diversity of finishing materials are used in the facades, such as brick, cement plastering, marble, granite, lime stone, painting, polystyrene.

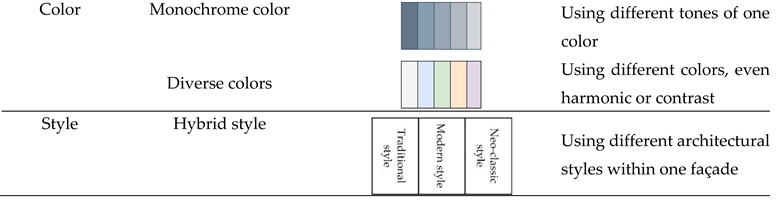

- Using colors in the façade. Samples showed two types, using monochrome colors in the façade and using contrasting colors in the façade.

- Using hybrid style or mixed style within one façade.

3.3. Step Two: Developing a Framework for the Sustainable Tangible and Intangible Factors that Effects on the Continuity of Architectural Identity

3.3.1. Findings of Step Two

- -

- Physical factors including tangible elements of typo-morphology of houses in Erbil city, found in step one.

- -

- Intangible socio-cultural factors, found in step two.

- -

- Tangible sustainable development factors, found in step two.

3. Results

This section m

3.4. Step three: Questionnaire for perception survey

- A description about the research and the aim of the questionnaire.

- General information about the participants including, age, academic qualification and job sector.

- Part one includes questions about architecture identity as a tensional process between keeping past identities and create new ones, that have discussed previously in the literature review.

- Part two includes questions that correlate the sustainable elements of cultural heritage which are derived from literature review and step two of this research as independent variables, and the process of continuity of architectural identity as dependent variable in order to identify which factors have more influence on the continuity of architectural identity in houses of Erbil city.

3.4.1. Sampling and Procedure

- -

- The questions are close ended, tried to be short and direct.

- -

- The answers are designed on a five point Likert scales, including option of totally disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and totally agree.

- -

- The respondents have to choose only one option for each question.

3.4.2. Statistical Analysis

- -

- Frequency of general information about respondents (Appendix 2)

- -

- Reliability of the questionnaire

- -

- Frequency of responses for part one and part two of the questionnaire (Appendix 2)

- -

- Correlation between independent and dependent variables of the research for part two of the questionnaire

- -

- Multiple regression for part two of the questionnaire

3.4.3. Statistical Descriptive Analysis of General Information about Respondents

3.4.4. Reliability of the Questionnaire

3.4.5. Statistical Descriptive Analysis for Part One of the Questionnaire

3.4.6. Correlation between Independent and Dependent Variables of the Research in Part Two of the Questionnaire

3.4.7. Correlation between Independent and Dependent Variables

- -

- A significant positive correlation between the variable of (physical factors of plan layout) and (the continuity of architectural identity) (r = 0.772, p < 0.05)

- -

- A significant positive correlation between the variable of (physical factors of facade) and (the continuity of architectural identity) (r = 0.661, p < 0.05)

- -

- A significant positive correlation between the variable of (socio-cultural factors) and (the continuity of architectural identity) (r = 0.605, p < 0.05)

- -

- A significant positive correlation between the variable of (Sustainable development factors) and (the continuity of architectural identity) (r = 0.390, p < 0.05)

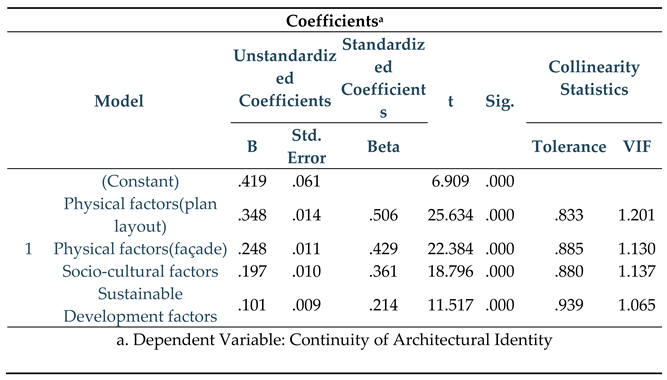

3.4.8. Multiple Regression Analysis

3.4.9. Regression Model

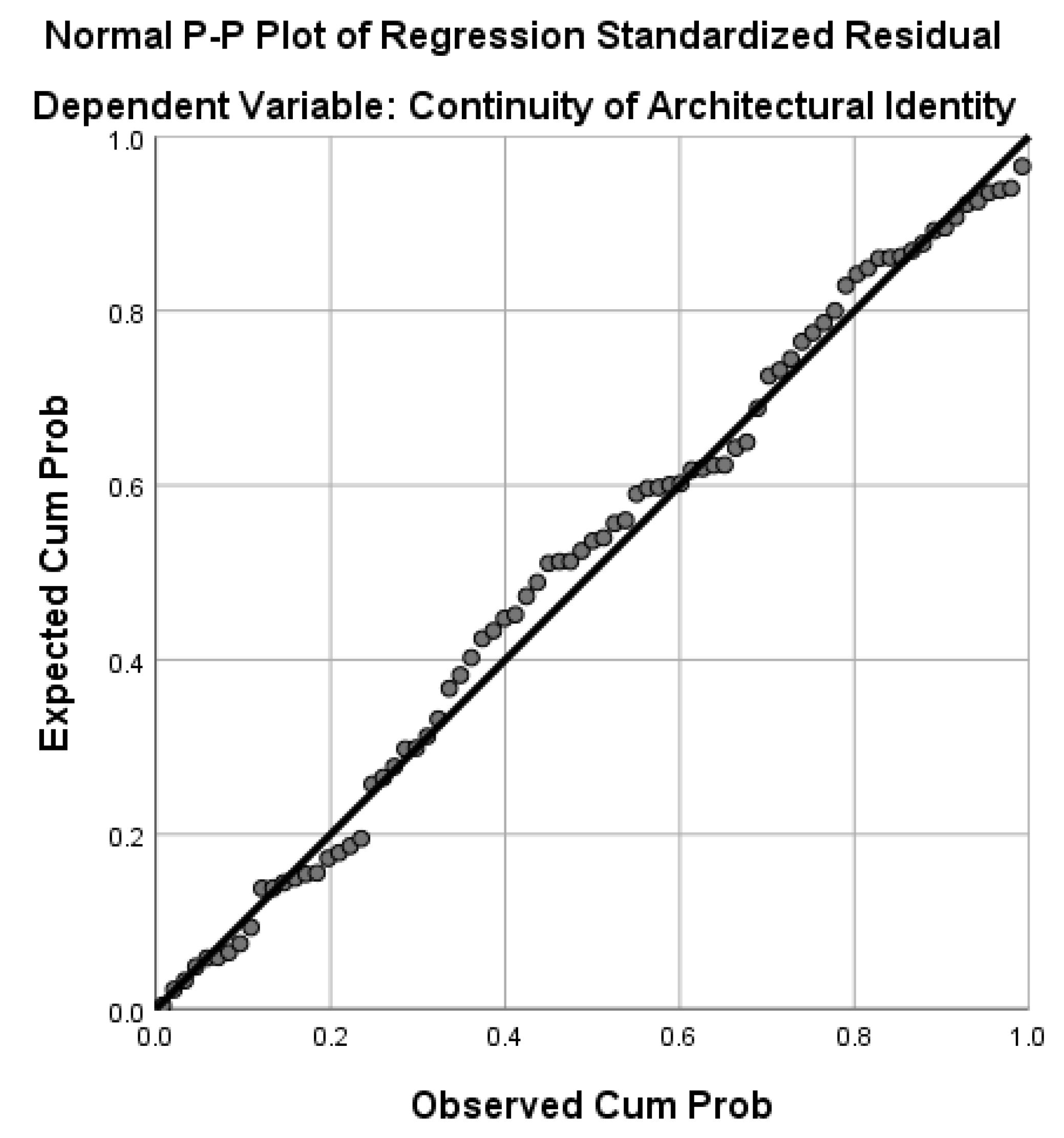

- R=0.988: This indicates a very strong positive correlation between the independent and dependent variables. The closer the value is to +1 or -1, the stronger the relationship.

- R Square=0.976: This represents the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the independent variable(s). In this case, approximately 97.6% of the variability in the dependent variable of continuity of architectural identity can be explained by the independent variables of physical factors related to typo-morphology of house layout and façade, sociocultural factors and sustainable development factors.

- Adjusted R Square=0.975: This is a modified version of R Square that adjusts for the number of independent variables in the model. It is slightly lower than R Square but still indicates a strong relationship.

- Standard error of the estimate=0.04553: This represents the average amount that the dependent variable deviates from the predicted value by the model. In this case, the smaller the value, the better the model is at predicting the dependent variable.

- Durbin Watson=2.308: This is a test for autocorrelation, which is when the residuals are correlated with each other. A value of 2.308 indicates no significant autocorrelation.

3.4.10. ANOVA Analysis of Regression Model

3.4.11. Regression Standardized Residual Analysis

3.4.12. Normal P-P Plot of Regression Standardized Residuals

3.4.13. Coefficient Analysis of Regression Model

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buckingham, D. (2008). Introducing identity. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, Identity, and Digital Media (pp. 1–24). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [CrossRef]

- Hague, C., & Jenkins, P. (2004). Place Identity, Participation and Planning. Routledge.

- Abel, C. (1997). Architecture and identity, towards global eco-culture. London, UK: Architecture Press ITD.

- UNESCO Santiago Field Office. (n.d.). Patrimonio: Cultura. Retrieved from https://en.unesco.org/fieldoffice/santiago/cultura/patrimonio.

- Luke, C., & Kersel, M. M. (2013). Us cultural diplomacy and Archaeology: Soft Power, hard heritage. Routledge.

- ICOMOS. (n.d.). ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and Sites. Retrieved , 2023, from https://www.icomos.org/en. 10 April.

- Matthes, E. H. (2018, July 12). The Ethics of Cultural Heritage. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved April 10, 2023, from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-cultural-heritage/. /.

- Konsa, K. (2013). Heritage as a socio-cultural construct: Problems of definition. Baltic Journal of Art History, 6, 125. [CrossRef]

- Thérond Daniel, & Trigona, A. (2009). Heritage and beyond. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Smith, L. (2010). Uses of heritage. Routledge.

- Lowenthal, D. (1985). The past is a foreign country. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Graham, B. , Ashworth, G., & Tunbridge, J. (2000). A geography of heritage: Power, culture and economy. London, UK: Arnold.

- Hogg, M. , & Abrams, D. (1988). Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes. London: Routledge.

- Koc, M. (2006). Cultural Identity Crisis in the Age of Globalization and Technology. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 51(1), 37-43.

- Ozaki, R. (2005). House Design as a Representation of Values and Lifestyles: The Meaning of Use of Domestic Space. In D. U. R. Garcia-Mira, J.E. Real & J. Romay (Eds.), Housing, Space and Quality of Life. Aldershot, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Graham, H. , Mason, R., & Newman, A. F. (2009). Literature Review: Historic Environment, Sense of Place, and Social Capital. International Centre for Cultural and Heritage Studies (ICCHS).

- Popescu, C. (2006). Space, Time: Identity. National Identities, 8(3), 189-206.

- Salama, A. M. (2005). Architectural Identity in the Middle East: Hidden Assumptions and Philosophical Perspectives. In D. Mazzoleni, G. Anzani, A. M. Salama, M. Sepe, & M. M. Simone (Eds.), Shores of the Mediterranean: Architecture as Language of Peace (pp. 77-85). Intra Moenia.

- Erem, Ö., & Gür, E. (2007). A Comparative Space Identification Elements Analysis Method for Districts: Maslak & Levent, Istanbul. In Proceedings of the 6th International Space Syntax Symposium.

- Baper, S. Y. , & Hassan, A. S. (2012). Factors Affecting the Continuity of Architectural Identity. American Transactions on Engineering & Applied Sciences, 1(3), 227-236.

- Hall, D. G. (1998). Continuity and the Persistence of Objects: When the Whole Is Greater than the Sum of the Parts. Cognitive Psychology, 37(1), 28-59. [CrossRef]

- Correa, C. (1983). Quest for Identity. In R. Powell (Ed.), Architecture and Identity. Singapore: Concept Media/Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

- Escobar, A. (2001). Culture sits in places: Reflections on globalism and subaltern strategies of localization. Political Geography, 20, 139-174.

- Salama, A. M. (2014). Interrogating the practice of image making in a budding context. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 8(3), 74-94.

- Lee, A. J. (2004). From historic architecture to cultural heritage: A journey through diversity, identity and community. Future Anterior, 1(2), 14-23.

- Rjoub, A. (2016). The relationship between heritage resources and contemporary architecture of Jordan. Architecture Research, 6(1), 1-12.

- Torabi, Z. , & Brahman, S. (2013). Effective factors in shaping the identity of architecture. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 15(1), 106-113.

- Horayangkura, V. (2017). In search of fundamentals of Thai architectural identity: A reflection of contemporary transformation. Athens Journal of Architecture [Internet], 3(1), 21-40.

- Al-Naim, M. (2008). Identity in transitional context: open-ended local architecture in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Architectural Research, 2(2), 125-146.

- Salama, A. (2006). Symbolism and Identity in the Eyes of Arabia’s Budding Professionals. Layer Magazine, LAYERMAG, New York, United States. Archnet.

- Bassim, A. , Salih, M., & Alobaydi, D. (2020, March). Metaphor of Symbols of Iraqi Architecture and Urbanism: Studying symbols as identity of Governmental Buildings’ façades in Baghdad, Iraq. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 745, No. 1, p. 012157). IOP Publishing.

- Mahgoub, Y. (2007). Hyper identity: the case of Kuwaiti architecture. International Journal of Architectural Research, 1(1), 70-85.

- Ali, M. , Zarkesh, A., & Yeganeh, M. Development of Housing Architecture Identity in Damascus.

- Baper, S. Y. (2018). The role of heritage buildings in constructing the continuity of architectural identity in Erbil city. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol, 9, 1-12.

- Farhad, S. , Maghsoodi Tilaki, M. J., & Hedayai Marzbali, M. (2020). Assessment of the Residential Satisfaction Role in Place Attachment with an Emphasis on Identity Elements in Traditional Neighborhoods; Case Study: Aghazaman Neighborhood, Sanandaj. Armanshahr Architecture & Urban Development, 13(32), 255-267.

- Di Summa-Knoop, L. T. (2016). Identity and strategies of identification: a moral and aesthetic shift in architecture and urbanism. Journal of aesthetics and Phenomenology, 3(2), 111-123.

- Qashmar, D. M. A. (2018). The dialectical dimensions of architectural identity in heritage conservation (the case of Amman). Arts and Design Studies, 61, 14-22.

- Baper, S. Y. , & Hassan, A. S. (2012). Factors affecting the continuity of architectural identity. American Transactions on Engineering & Applied Sciences, 1(3), 227-236.

- Topçu, K. D. , & Bilsel, S. G. (2010). Urban identities dissolving into the changing consumption culture. In 14th International Planning History Society Conference (IPHS), İstanbul.

- Ashour, R. (2020). In Search of The Traditional Architectural Identity: The Case of Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Islamic Architecture, 6(1), 58-67.9888sdsdsds0064. 9888. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. , & Svejenova, S. (2017). The architecture of city identities: A multimodal study of Barcelona and Boston. In Multimodality, meaning, and institutions (Vol. 54, pp. 203-234). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Alkilidar, M. S. M. , & NeamaAlKhafaji, S. J. (2020). Islamic Architectural Heritage and National Identity in Iraq. TEST Engineering & Management, 83, 14952-14964.

- Mahgoub, Y. (2007). Architecture and the expression of cultural identity in Kuwait. The Journal of Architecture, 12(2), 165-182.

- Lahoud, A. L. (2008). The role of cultural (architecture) factors in forging identity. National Identities, 10(4), 389-398.

- Mair, N. , Zaman, Q. M., Mair, N., & Zaman, Q. M. (2020). Contextual Setting: Political Ideology, Architecture and Identity. Berlin: A City Awaits: The Interplay between Political Ideology, Architecture and Identity, 1-3.

- Niglio, O. (2014). Inheritance and identity of Cultural Heritage. Advances in Literary Study, 2(1), 1-4.

- Al-Mohannadi, A., Furlan, R., & Major, M. D. (2020). A cultural heritage framework for preserving Qatari vernacular domestic architecture. Sustainability, 12(18), 7295.

- Farhan, S. , Akef, V., & Nasar, Z. (2020). The transformation of the inherited historical urban and architectural characteristics of Al-Najaf's Old City and possible preservation insights. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 9(4), 820-836.

- Nooraddin, H. (2012). Architectural identity in an era of change. Developing Country Studies, 2(10), 81-96.

- Ayıran, N. (2012). The role of metaphors in the formation of architectural identity.

- Rakatansky, M. (1995). Identity and the discourse of politics in contemporary architecture. Assemblage, (27), 9-18.

- Da, G. M. P. , & Ariffin, S. A. I. S. (2015). Significance Of Local Involvement In Continuing Local Architectural Identity. Jurnal Teknologi. Penerbit Utm Press.

- Horayangkura, V. (2010). The creation of cultural heritage: towards creating a modern Thai architectural identity. Manusya: Journal of Humanities, 13(1), 60-80.

- Ettehad, S. , Karimi Azeri, A. R., & Kari, G. (2015). The role of culture in promoting architectural identity. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences: Proceedings, 3(4 (s)), pp-410.

- Demiri, D. (1983). The notion of type in architectural thought. Edinburgh Architectural Research, 10, 117-137.

- Salama, A. M. (2006). A typological perspective: the impact of cultural paradigmatic shifts on the evolution of courtyard houses in Cairo. METU Journal of Faculty of Architecture, 23(1), 41-58.

- Gulgonen, A. , & Laisney, F. (1982). Contextual approaches to typology at the Ecoles des Beaux-Arts. Journal of Architectural Education, 35(2), 26-29.

- Leupen, B., Grafe, C., Kornig, N., Lampe, M., & Zeeuw, P. (1997). Design and analysis. OIO Publishers, Rotterdam.

- Pearce, P.J. (1996). Principles of morphology and the future of architecture. International Journal of Space Structures, 11, 103-114.

- Petruccioli, A. (1998). Exoteric, polytheistic fundamentalist typology. In A. Petruccioli (Ed.), Typological processes and design theory, Aga Khan Program for Islamic architecture (pp. 11-22). Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Eruzun, Z. a. K. , & Saatçi, S. (2021). An Analysis of the Plan and Facade Typologies of Boyabat’s Traditional Turkish Houses. Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Civil Engineering, 28(1), 40–55. [CrossRef]

- Mihçioğlu Bilgi, E. , & Uluca Tümer, E. (2020). Building Typologies in Between the Vernacular and the Modern: Antakya (Antioch) in the Early 20th Century. Sage Open, 10(2), 2158244020933318.

- Remali, A. M. , Salama, A. M., Wiedmann, F., & Ibrahim, H. (2016). A chronological exploration of the evolution of housing typologies in Gulf cities. City, Territory and Architecture, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Turgut, D. (2019). An analysis of the plan typology of vernacular Talas Houses. İTÜ Dergisi A, 16(1), 117–125. [CrossRef]

- Mahayuddin, S. A. , Zaharuddin, W. a. Z. W., Harun, S. N., & Ismail, B. (2017). Assessment of Building Typology and Construction Method of Traditional Longhouse. Procedia Engineering, 180, 1015–1023. [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, S. , Ertürk, F., Durak, Ş., & Dülger, A. C. (2017). Importance of Typological Analysis in Architecture for Cultural Continuity: An Example from Kocaeli (Turkey). IOP Conference Series, 245, 072033. [CrossRef]

- Funo, S., Ferianto, B. F., & Yamada, K. (2005). Considerations on Typology of Kampung House and Betawi House of KAMPUNG LUAR BATANG (JAKARTA). Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 4(1), 129–136. [CrossRef]

- Perera, D. , & Pernice, R. (2022). Modernism in Sri Lanka: a comparative study of outdoor transitional spaces in selected traditional and modernist houses in the early post-independence period (1948–1970). Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- BACAK, F. N. , DAĞ GÜRCAN, A., & TERECİ, A. (2021). Residential Typology Research on Rural Architecture Heritage: Çavuş Village (Konya, Beyşehir).

- Chen, Y.-R., Ariffin, S. I., & Wang, M.-H. (2008). The Typological Rule System of Malay houses in Peninsula Malaysia. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 7(2), 247–254. [CrossRef]

- Kien, T. (2008). “Tube House” and “Neo Tube House” in Hanoi: A Comparative Study on Identity and Typology. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 7(2), 255-262.

- Amole, D. (2007). Typological analysis of students’ residences. International Journal of Architectural Researh, 1(3), 76-87.

- Funo, S. , Yamamoto, N., & Silas, J. (2002). Typology of kampung houses and their transformation process-- a study on urban tissues of an Indonesian city. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 1(2), 193–200. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N. A., Jalboosh, F. Y., Fakhoury, L. A., & Ghrayib, R. (2016). Urban and rural Umayyad House Architecture in Jordan: A comprehensive typological analysis at Al-Hallabat. International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR, 10(2), 87. [CrossRef]

- Dursun, P., & Saðlamer, G. (2006). Describing housing morphology in the city of Trabzon. Open House International, 31(2), 72–81. [CrossRef]

- Azad, S. P., Morinaga, R., & Kobayashi, H. (2018). Effect of housing layout and open space morphology on residential environments–applying new density indices for evaluation of residential areas case study: Tehran, Iran. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 17(1), 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Dwijendra, N. K. (2019). Morphology of house pattern in Tenganan Dauh Tukad village, Karangasem Bali, Indonesia. Journal of Social and Political Sciences, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Haraty, H. J. S. , Raschid, M. Y. M., & Yunos, M. Y. M. (2018). Morphology of Islamic Traditional Iraqi Courtyard House Toward Holistic Islamic Approach in New Residential Development in Iraq. International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7(3.7), 379-382.

- Almumar, M. , & Baper, S. (2021). Performance of Traditional Iraqi Courtyard Houses: Exploring Morphology Patterns of Courtyard Spaces. International Transaction Journal of Engineering, Management, & Applied Sciences & Technologies, 12(12), 1-16.

- Kamalipour, H., & Zaroudi, M. (2014). Sociocultural context and vernacular housing morphology: A case study. Current Urban Studies, 02(03), 220–232. [CrossRef]

- Widiastuti, I. (2013). The living culture and typo-morphology of vernacular houses in kerala. International Society of Vernacular Settlement (ISVS) e-Journal, 2(3), 41-53.

- Sun, Y. , & Bao, L. (2021, February). Transitional urban morphology and housing typology in a traditional settlement of 20th century, Nanjing. In ISUF 2020 Virtual Conference Proceedings.

- Rahbarianyazd, R. (2020). Typo- morphological analysis as a method for physical revitalization: The case of famagusta’s residential district. Proceedings Article. [CrossRef]

- Kostourou, F. (2021). Housing growth: Impacts on density, space consumption and urban morphology. Buildings and Cities, 2(1), 55–78. [CrossRef]

- Alyaqoobi, D. , Michelmore, D., & Tawfiq, R. K. (2016). Highlights of Erbil citadel: History and architecture (2nd ed.). High commission for Erbil citadel revitalization (HCECR).

- Location_map_Arbil.png (2213×1774) (wikimedia.org).

- Cohen, L. , Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th ed.). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Sekaran, U. (2009). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. Wiley India Pvt. Ltd.

- Ching, F. D. (2023). Architecture: Form, space, and order. John Wiley & Sons.

- Mzoori, F. A. (2014). Spatial configuration and functional efficiency of house layouts. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

- Landau, S. , Leese, M., Stahl, D., & Everitt, B. S. (2011). Cluster analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Amos, R. (1969). House Form and Culture. Englewood Cliffs (NJ).

- Duran, D. C. , Gogan, L. M., Artene, A., & Duran, V. (2015). The components of sustainable development-a possible approach. Procedia Economics and Finance, 26, 806-811.

- Gražulevičiūtė, I. (2006). Cultural heritage in the context of sustainable development. Environmental Research, Engineering & Management, 37(3).

- Eyyamoğlu, M. , & Akçay, A. Ö. (2022). Assessment of Historic Cities within the Context of Sustainable Development and Revitalization: The Case of the Walled City North Nicosia. Sustainability, 14(17), 10678.

- Zaid, M. A. (2015). Correlation and regression analysis textbook. Oran, Ankara: The Statistical, Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (SESRIC).

| Research steps | Research method |

Research tool |

Type of sample |

Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Qualitative | Typo-morphology analysis | Houses in Erbil city |

The aim is to establish a framework that depicts the physical and typo-morphological characteristics of houses in Erbil city between 1900 and 2020 |

| Step 2 | Qualitative | Checklist analysis | Literature review |

The objective is to develop a framework that portrays both tangible and intangible sustainable elements of cultural heritage that impact the process of continuity of architectural identity |

| Step 3 |

Quantitative |

Questionnaire | Experts in the field of architecture |

To identify the factors that influences on the continuity of architectural identity as a tensional relationship between inheritance and creation of identities. Also to find the most effective tangible and intangible factors that influences on the continuity of architectural identity in the houses in Erbil city for the period (1900-2020) |

| Typo-morphology of houses | Reference |

|---|---|

| Position of house and plot land Shape of plan layout Construction system Features of the facade |

[61] |

| Accessibility Ground floor plan typology Façade typology Structural system and materials |

[62] |

| Internal relationship of spaces Spatial organization |

[63] |

| Plan typology Space functions |

[64] |

| Plan form and layout Roof configuration Construction techniques |

[65] |

| Relation of house area to land plot area Roof type in plan Floor plans and vertical circulation Façade articulation Façade finishing Shape of entrance Shape of windows |

[66] |

| Indoor space arrangements Indoor space functions |

[67] |

| Connection between indoor and outdoor spaces Hierarchy of open spaces Connection and boundaries of functional zonings |

[68] |

| Relation of house with land plot Orientation Plan layout shape Facade arrangement Construction technique Structural condition Building materials Façade elements |

[69] |

| Spatial layout Functional zones Construction |

[70] |

| Spatial composition Relation between mass and void Construction Visibility from street Façade Street accessibility Number of floors Building materials Functions |

[71] |

| Spatial organization Number of floor Plan form |

[72] |

| Spatial organization Relation between house area and plot area Functional zones Number of floor House orientation regarding street House enclosure |

[73] |

| Type of houses in terms of space organization Plan layout Functions |

[74] |

| Spatial patterns | [75] |

| Shape of house layout Relation between house area and plot area Building parameter |

[76] |

| Spatial pattern Function Shape of plan Material |

[77] |

| Form and space arrangement Accessibility and entrance |

[78] |

| Shape of courtyard Mass configuration Position of the courtyard Patterns of indoor and outdoor spaces |

[79] |

| Physical form Spatial configuration |

[80] |

| Spatial arrangement Structure |

[81] |

| Housing typologies | [82] |

| Spatial organization Building and façade typology |

[83] |

| Form typology Mass configuration |

[84] |

| Period | Number of samples |

|---|---|

| 1900-1929 | 20 |

| 1930-1959 | 20 |

| 1960-1989 | 50 |

| 1990-2020 | 50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Factors effecting the continuity of architectural identity | Tangibility of factor | Reference |

| Physical form | Tangible | [34] [27] [35] [37] [24] [38] [40] [41] |

| Self-identity | Intangible | [33] |

| Sustainability | Tangible and intangible | [53] |

| Economy | Tangible | [53] |

| Environment | Tangible and intangible | [48] |

| Politics | Tangible and intangible | [48,49,45] [52] [51] |

| Religious believes | Intangible | [48] |

| History as a concept of time | Tangible and Intangible | [25] [27,28,29,44] [30] |

| spatial organization | Tangible | [27] |

| Building material | Tangible | [27,67] |

| Context as a concept of place | Tangible | [27,43] |

| Culture | Tangible and intangible | [54,37] [43,30,47] |

| Cultural change | Tangible and intangible | [54,37] |

| Sense of belonging | Intangible | [42] |

| Social factors | Intangible | [39] |

| Function | Tangible | [39] |

| Cultural value | Intangible | [54] |

| Socio-cultural factors | Intangible | [47] |

| Way of life | Intangible | [47] |

| Cronbach's Alpha | N of Items |

| .854 | 69 |

| Questions | Totally disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Totally agree |

| Architectural identity is a static object that inherited from the past | 3.8% | 17.7% | 16.5% | 41.8% | 20.3% |

| Architectural identity could be created at any time | 1.3% | 16.5% | 17.7% | 43.0% | 21.5% |

| Architectural identity is the result of the tensional relationship between keeping past identities and creating new identities | 0.0% | 3.8% | 19.0% | 40.5% | 36.7% |

| Factors affecting the process of continuity in architectural identity vary in different cultures and contexts. | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.8% | 41.8% | 54.4% |

| (Time) is an effective factor in the process of continuity of architectural identity | 1.3% | 3.8% | 10.1% | 46.8% | 38.0% |

| (Place) is an effective factor in the process of continuity of architectural identity | 0.0% | 2.5% | 11.4% | 44.3% | 41.8% |

| The level of identity representation, including (architecture, urban, planning, and region) impacts on the process of continuity of architectural identity. | 0.0% | 1.3% | 15.2% | 54.4% | 29.1% |

| Functionality is more representing architectural identity | 1.3% | 29.1% | 40.5% | 22.8% | 6.3% |

| Form as visual aspect is more reflecting architectural identity | 0.0% | 3.8% | 19.0% | 51.9% | 25.3% |

| Non-physical aspects related to build environments and contexts mostly represent identities | 1.3% | 10.1% | 41.8% | 32.9% | 13.9% |

| Continuity of Architectural Identity | ||

| Physical factors (plan layout) | Pearson Correlation | .772** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | |

| N | 79 | |

| Physical factors (façade) | Pearson Correlation | .661** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | |

| N | 79 | |

| Socio-cultural factors | Pearson Correlation | .605** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | |

| N | 79 | |

| Sustainable Development factors | Pearson Correlation | .390** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | |

| N | 79 |

| Model Summaryb | |||||

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 | .988a | .976 | .975 | .04553 | 2.308 |

| a. Predictors: (Constant), Sustainable Development factors, Physical factors(façade), Socio-cultural factors, Physical factors(plan layout) | |||||

| b. Dependent Variable: Continuity of Architectural Identity | |||||

| Model | Sum of squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| Regression | 6.234 | 4 | 1.558 | 751.656 | .000b | |

| 1 | Residual | .153 | 74 | .002 | ||

| Total | 6.387 | 78 | ||||

| a. Dependent Variable: Continuity of Architectural Identity | ||||||

| b. Predictors: (Constant), Sustainable Development factors, Physical factors(façade), Socio-cultural factors, Physical factors(plan layout) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).