Submitted:

15 May 2023

Posted:

17 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

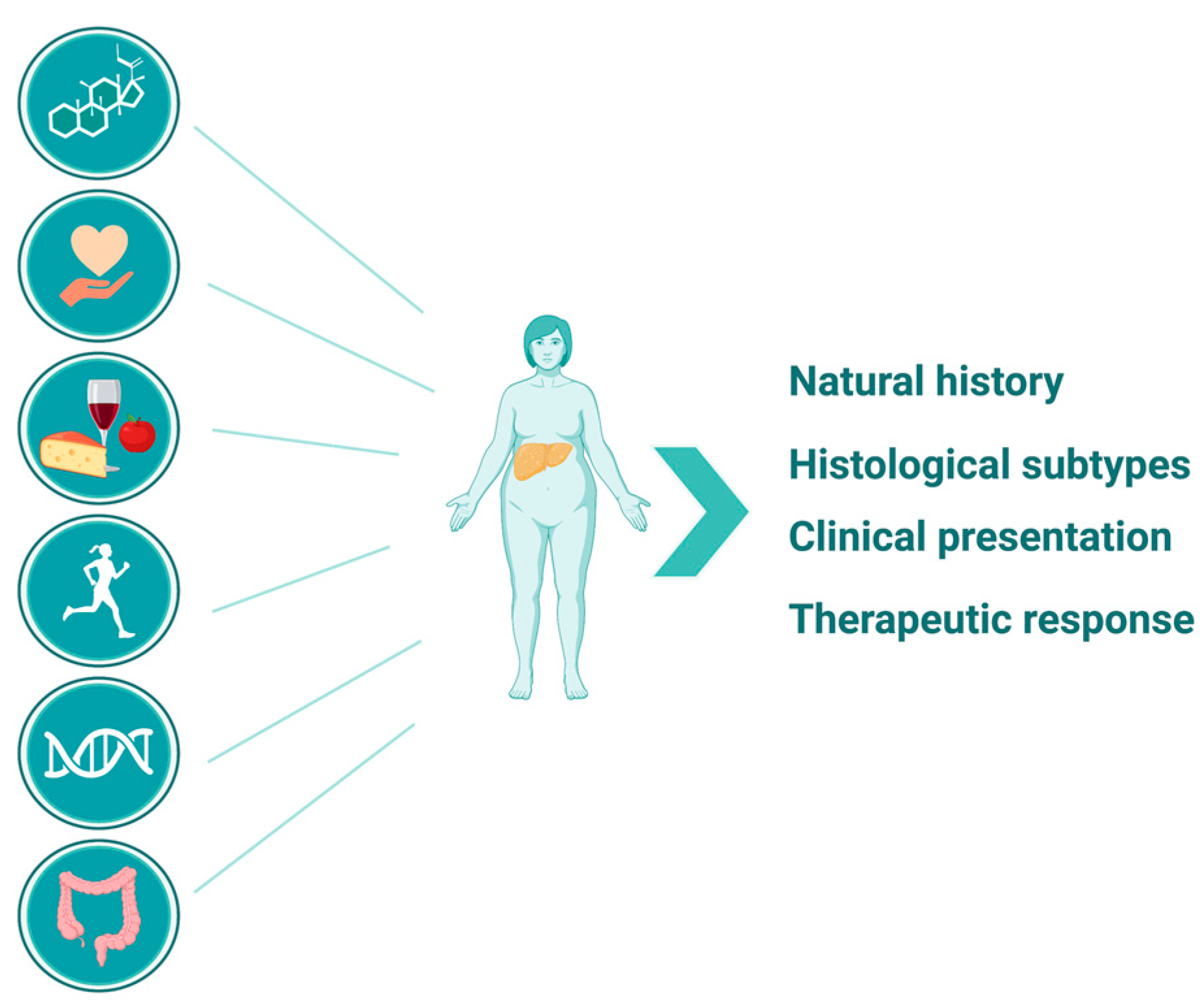

1. Introduction

2. NAFLD in Postmenopausal Women

2.1. Why Does NAFLD Risk Increase after Menopause?

2.2. Strategies for Risk Reduction of NAFLD in Postmenopausal Women

3. Nutritional Factors That May Benefit Postmenopausal Women with NAFLD

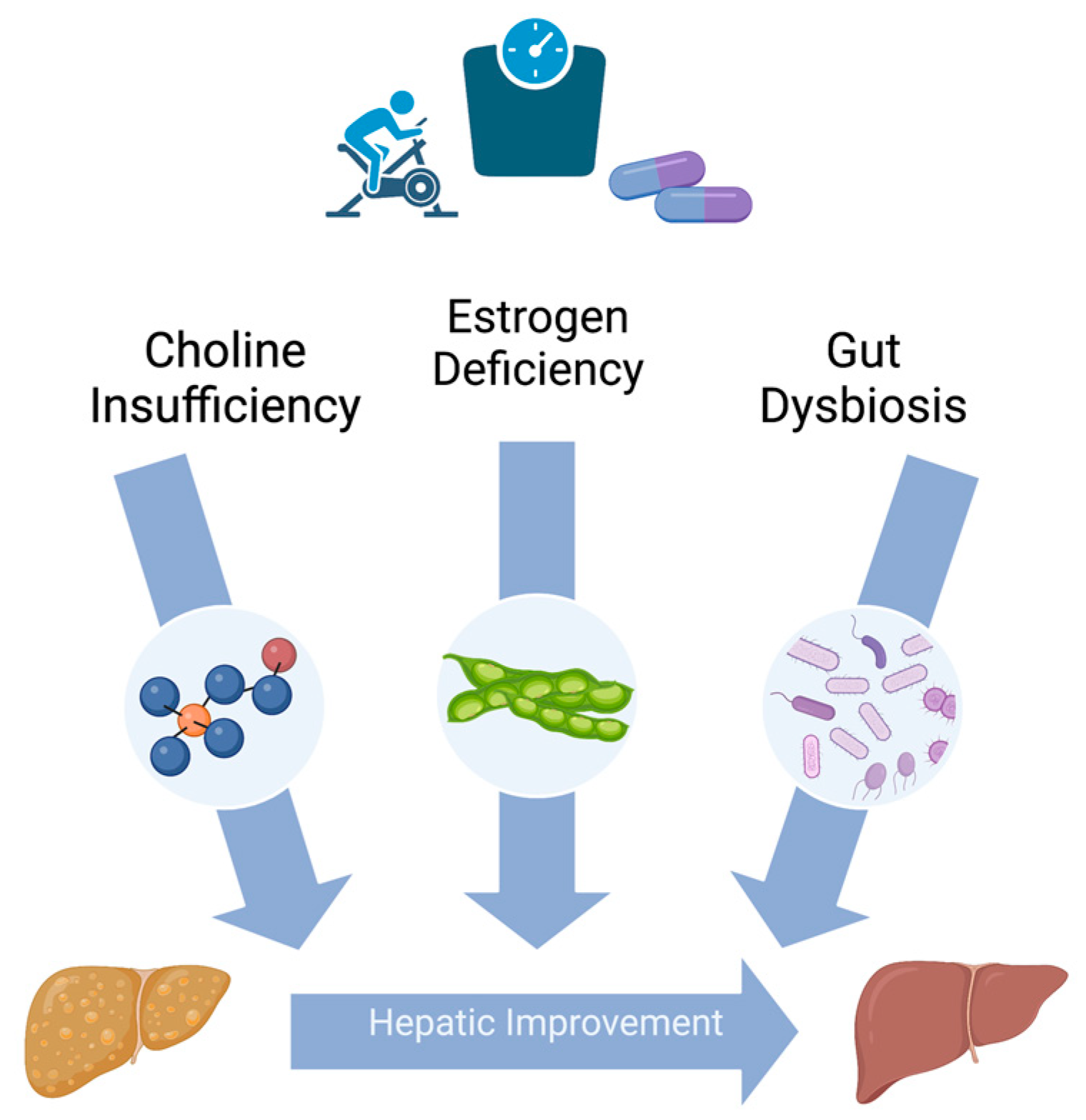

3.1. Choline

3.2. Soy Isoflavones

3.3. Probiotics

4. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parthasarathy, G.; Revelo, X.; Malhi, H. Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: An Overview. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 478–492. [CrossRef]

- Marchesini, G.; Brizi, M.; Morselli-Labate, A.M.; Bianchi, G.; Bugianesi, E.; McCullough, A.J.; Forlani, G.; Melchionda, N. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. Am. J. Med. 1999, 107, 450–455. [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Corey, K.E.; Byrne, C.D.; Roden, M. The complex link between NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus — mechanisms and treatments. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 599–612. [CrossRef]

- Fabbrini, E.; Sullivan, S.; Klein, S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology 2010, 51, 679–689. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73–84.

- Arrese, M.; Arab, J.P.; Barrera, F.; Kaufmann, B.; Valenti, L.; Feldstein, A.E. Insights into Nonalcoholic Fatty-Liver Disease Heterogeneity. Semin. Liver Dis. 2021, 41, 421–434. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Loomba, R.; Rinella, M.E.; Bugianesi, E.; Marchesini, G.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Serfaty, L.; Negro, F.; Caldwell, S.H.; Ratziu, V.; et al. Current and future therapeutic regimens for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2018, 68, 361–371. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, M.; Patel, P.; Dunn-Valadez, S.; Dao, C.; Khan, V.; Ali, H.; El-Serag, L.; Hernaez, R.; Sisson, A.; Thrift, A.P.; et al. Women Have a Lower Risk of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease but a Higher Risk of Progression vs Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 19, 61–71.e15. [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, J.K. NAFLD and NASH in Postmenopausal Women: Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment. Endocrinology 2020, 161. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Pang, H.; Guy, C.D.; Smith, A.D.; Diehl, A.M.; Suzuki, A. Gender and menopause impact severity of fibrosis among patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2013, 59, 1406–1414. [CrossRef]

- Arshad, T.; Golabi, P.; Paik, J.; Mishra, A.; Younossi, Z.M. Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in the Female Population. Hepatol. Commun. 2018, 3, 74–83. [CrossRef]

- Le, M.H.; Yeo, Y.H.; Zou, B.; Barnet, S.; Henry, L.; Cheung, R.; Nguyen, M.H. Forecasted 2040 global prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease using hierarchical bayesian approach. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2022, 28, 841–850. [CrossRef]

- Paik, J.M.; Henry, L.; De Avila, L.; Younossi, E.; Racila, A.; Younossi, Z.M. Mortality Related to Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is Increasing in the United States. Hepatol. Commun. 2019, 3, 1459–1471. [CrossRef]

- Noureddin, M.; Vipani, A.; Bresee, C.; Todo, T.; Kim, I.K.; Alkhouri, N.; Setiawan, V.W.; Tran, T.; Ayoub, W.S.; Lu, S.C.; et al. NASH Leading Cause of Liver Transplant in Women: Updated Analysis of Indications For Liver Transplant and Ethnic and Gender Variances. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 1649–1659. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Golabi, P.; Paik, J.M.; Henry, A.; Van Dongen, C.; Henry, L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Caldwell, S.; Barb, D.; Kleiner, D.E.; Loomba, R. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1797–1835. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, T.; Viñuela, M.; Vidal, C.; Barrera, F. Lifestyle changes in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0263931. [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Gomez, E.; Martinez-Perez, Y.; Calzadilla-Bertot, L.; Torres-Gonzalez, A.; Gra-Oramas, B.; Gonzalez-Fabian, L.; Friedman, S.L.; Diago, M.; Romero-Gomez, M. Weight Loss Through Lifestyle Modification Significantly Reduces Features of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 367–378.e5. [CrossRef]

- Thoma, C.; Day, C.P.; Trenell, M.I. Lifestyle interventions for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: A systematic review. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 255–266. [CrossRef]

- Varol, P.H.; Kaya, E.; Alphan, E.; Yilmaz, Y. Role of intensive dietary and lifestyle interventions in the treatment of lean nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 32, 1352–1357. [CrossRef]

- Sinn, D.H.; Kang, D.; Cho, S.J.; Paik, S.W.; Guallar, E.; Cho, J.; Gwak, G.-Y. Weight change and resolution of fatty liver in normal weight individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, e529–e534. [CrossRef]

- Otten, J.; Mellberg, C.; Ryberg, M.; Sandberg, S.; Kullberg, J.; Lindahl, B.; Larsson, C.; Hauksson, J.; Olsson, T. Strong and persistent effect on liver fat with a Paleolithic diet during a two-year intervention. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 747–753. [CrossRef]

- Liver, E.A.f.t.S.o.t.; Diabetes, E.A.F.T.S.O.; Obesity, E.A.F.T.S.O. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1388–1402.

- Best, N.; Flannery, O. Association between adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and the Eatwell Guide and changes in weight and waist circumference in post-menopausal women in the UK Women’s Cohort Study. Post Reprod. Heal. 2023, 29, 25–32. [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; De Amicis, R.; Battezzati, A.; Bertoli, S. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Metabolically Unhealthy Obesity in Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 858206. [CrossRef]

- Leone, A.; et al. Association between Mediterranean Diet and Fatty Liver in Women with Overweight and Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14.

- Sarkar, M.; Cedars, M.I. Untangling the Influence of Sex Hormones on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Women. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 20, 1887–1888. [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, M. Aging is a risk factor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in premenopausal women. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 237–43. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Hu, Z.; Shrestha, U.K. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its metabolic risk factors in women of different ages and body mass index. Menopause 2015, 22, 667–673. [CrossRef]

- Bertolotti, M.; Lonardo, A.; Mussi, C.; Baldelli, E.; Pellegrini, E.; Ballestri, S.; Romagnoli, D.; Loria, P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and aging: Epidemiology to management. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 14185–204. [CrossRef]

- Cerda, C.; Pérez-Ayuso, R.M.; Riquelme, A.; Soza, A.; Villaseca, P.; Sir-Petermann, T.; Espinoza, M.; Pizarro, M.; Solis, N.; Miquel, J.F.; et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Hepatol. 2007, 47, 412–417. [CrossRef]

- Albhaisi, S.; Sanyal, A.J. Gene-Environmental Interactions as Metabolic Drivers of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rector, R.S.; Thyfault, J.P.; Wei, Y.; A Ibdah, J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome: An update. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; George, J. Genetic contributions to NAFLD: leveraging shared genetics to uncover systems biology. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 40–52. [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, B.; Lindén, D.; Brolén, G.; Liljeblad, M.; Bjursell, M.; Romeo, S.; Loomba, R. Review article: the emerging role of genetics in precision medicine for patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 1305–1320. [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Gomez, E.; Pirola, C.J.; Sookoian, S.; Wilson, L.A.; Belt, P.; Liang, T.; Liu, W.; Chalasani, N. Impact of the Association Between PNPLA3 Genetic Variation and Dietary Intake on the Risk of Significant Fibrosis in Patients With NAFLD. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 116, 994–1006. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.M.; da Costa, K.-A.; Kwock, L.; Galanko, J.; Zeisel, S.H. Dietary choline requirements of women: effects of estrogen and genetic variation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1113–1119. [CrossRef]

- Sokolowska, K.E.; Maciejewska-Markiewicz, D.; Bińkowski, J.; Palma, J.; Taryma-Leśniak, O.; Kozlowska-Petriczko, K.; Borowski, K.; Baśkiewicz-Hałasa, M.; Hawryłkowicz, V.; Załęcka, P.; et al. Identified in blood diet-related methylation changes stratify liver biopsies of NAFLD patients according to fibrosis grade. Clin. Epigenetics 2022, 14, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Albhaisi, S.A.; Bajaj, J.S. The Influence of the Microbiome on NAFLD and NASH. Clin. Liver Dis. 2021, 17, 15–18. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Q.; Ai, P.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Ding, G.; Li, Y.; Feng, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Association between Serum Uric Acid and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease according to Different Menstrual Status Groups. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 2019, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.E.; Yim, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Lim, S.H.; Yang, J.I.; Kim, Y.S.; Yang, S.Y.; Kwak, M.-S.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, S.-H. The influence of metabolic factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Grobe, Y.; Ponciano-Rodríguez, G.; Ramos, M.H.; Uribe, M.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. Prevalence of non alcoholic fatty liver disease in premenopausal, posmenopausal and polycystic ovary syndrome women. The role of estrogens. Ann. Hepatol. 2010, 9, 402–409. [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-S. Relationship between serum uric acid level and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in pre- and postmenopausal women. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 62, 158–163. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Suh, B.-S.; Chang, Y.; Kwon, M.-J.; Yun, K.E.; Jung, H.-S.; Kim, C.-W.; Kim, B.-K.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, Y.; et al. Menopausal stages and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged women. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 190, 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, C.; Ni, J.; Han, X. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in non-menopausal and postmenopausal inpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in China. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2019, 19, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Unalp–Arida, A.; Yates, K.; Sanyal, A.; Guy, C.; Diehl, A.M. Regional anthropometric measures and hepatic fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 8, 1062–1069. [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, M.; Thomas, E.; Sumida, Y.; Eguchi, Y.; Schiff, E.R. The influence of menopause on the development of hepatic fibrosis in nonobese women with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2014, 60, 1792–1792. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Abdelmalek, M.F. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women. Women's Heal. 2009, 5, 191–203. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Wang, F.; Sheng, Y.; Xia, F.; Jin, Y.; Ding, G.; Wang, X.; Yu, J. Estrogen supplementation deteriorates visceral adipose function in aged postmenopausal subjects via Gas5 targeting IGF2BP1. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 163, 111796. [CrossRef]

- Abildgaard, J.; Ploug, T.; Al-Saoudi, E.; Wagner, T.; Thomsen, C.; Ewertsen, C.; Bzorek, M.; Pedersen, B.K.; Pedersen, A.T.; Lindegaard, B. Changes in abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue phenotype following menopause is associated with increased visceral fat mass. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, J.C.; Champagne, C.M.; de Jonge, L.; Xie, H.; Smith, S.R. Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 949–958. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.C. Menopause and diabetes. Climacteric 2023, 26, 216–221. [CrossRef]

- Torosyan, N.; Visrodia, P.; Torbati, T.; Minissian, M.B.; Shufelt, C.L. Dyslipidemia in midlife women: Approach and considerations during the menopausal transition. Maturitas 2022, 166, 14–20. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Kardashian, A.; Sarkar, M. NAFLD in women: Unique pathways, biomarkers and therapeutic opportunities. Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 2019, 18, 425–432.

- Berkovic, M.C.; Bilic-Curcic, I.; Mrzljak, A.; Cigrovski, V. NAFLD and Physical Exercise: Ready, Steady, Go!. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Molina, E.; Furtado, G.E.; Jones, J.G.; Portincasa, P.; Vieira-Pedrosa, A.; Teixeira, A.M.; Barros, M.P.; Bachi, A.L.L.; Sardão, V.A. The advantages of physical exercise as a preventive strategy against NAFLD in postmenopausal women. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 52, e13731. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, J.; Fisher, B.M.; Jaap, A.J.; Stanley, A.; Paterson, K.; Sattar, N. Effects of HRT on liver enzyme levels in women with type 2 diabetes: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Endocrinol. 2006, 65, 40–44. [CrossRef]

- Florentino, G.S.d.A.; Cotrim, H.P.; Vilar, C.P.; Florentino, A.V.d.A.; Guimaraes, G.M.A.; Barreto, V.S.T. NONALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER DISEASE IN MENOPAUSAL WOMEN. Arq. de Gastroenterol. 2013, 50, 180–185. [CrossRef]

- Salpeter, S.R.; Walsh, J.M.E.; Ormiston, T.M.; Greyber, E.; Buckley, N.S.; Salpeter, E.E. Meta-analysis: effect of hormone-replacement therapy on components of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. Diabetes, Obes. Metab. 2005, 8, 538–554. [CrossRef]

- Fakhry, T.K.; Mhaskar, R.; Schwitalla, T.; Muradova, E.; Gonzalvo, J.P.; Murr, M.M. Bariatric surgery improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a contemporary systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 502–511. [CrossRef]

- Riazi, K.; et al. Dietary Patterns and Components in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): What Key Messages Can Health Care Providers Offer? Nutrients 2019, 11.

- Zeisel, S.H.; Da Costa, K.; Franklin, P.D.; Alexander, E.A.; Lamont, J.T.; Sheard, N.F.; Beiser, A. Choline, an essential nutrient for humans. FASEB J. 1991, 5, 2093–2098. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.M.; Dacosta, K.A.; Kwock, L.; Stewart, P.W.; Lu, T.-S.; Stabler, S.P.; Allen, R.H.; Zeisel, S.H. Sex and menopausal status influence human dietary requirements for the nutrient choline. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1275–1285. [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeier, M.; da Costa, K.-A.; Fischer, L.M.; Zeisel, S.H. Genetic variation of folate-mediated one-carbon transfer pathway predicts susceptibility to choline deficiency in humans. 2005, 102, 16025–16030. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Hada, N.; Sakamaki, Y.; Uno, A.; Shiga, T.; Tanaka, C.; Ito, T.; Katsume, A.; Sudoh, M. An improved mouse model that rapidly develops fibrosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 94, 93–103. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Shu, X.-O.; Xiang, Y.-B.; Li, H.; Yang, G.; Gao, Y.-T.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, X. Higher dietary choline intake is associated with lower risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver in normal-weight Chinese women. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 2034–2040. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; et al. Choline: The Underconsumed and Underappreciated Essential Nutrient. Nutr. Today 2018, 53, 240–253.

- Kim, S.; Fenech, M.F.; Kim, P.-J. Nutritionally recommended food for semi- to strict vegetarian diets based on large-scale nutrient composition data. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Noga, A.A.; Zhao, Y.; Vance, D.E. An unexpected requirement for phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase in the secretion of very low density lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 42358–42365. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.M.; E Vance, D. The active synthesis of phosphatidylcholine is required for very low density lipoprotein secretion from rat hepatocytes.. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 2998–3004. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Vance, D.E. Reduction in VLDL, but not HDL, in plasma of rats deficient in choline. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1990, 68, 552–558. [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuka, A.; Matsuyama, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Katayama, A.; Eguchi, J.; Murakami, K.; Teshigawara, S.; Ogawa, D.; Wada, N.; Yasunaka, T.; et al. Insufficiency of phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase is risk for lean non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21721. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Song, J.; Mar, M.-H.; Edwards, L.J.; Zeisel, S.H. Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) knockout mice have hepatic steatosis and abnormal hepatic choline metabolite concentrations despite ingesting a recommended dietary intake of choline. 2003, 370, 987–993. [CrossRef]

- Waite, K.A.; Cabilio, N.R.; Vance, D.E. Choline deficiency-induced liver damage is reversible in Pemt(-/-) mice. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 68–71.

- Vance, D.E. Physiological roles of phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2013, 1831, 626–632. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.L.; Zhao, Y.; Koonen, D.P.Y.; Sletten, T.; Su, B.; Lingrell, S.; Cao, G.; Peake, D.A.; Kuo, M.-S.; Proctor, S.D.; et al. Impaired de novo choline synthesis explains why phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase-deficient mice are protected from diet-induced obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 22403–22413. [CrossRef]

- Piras, I.S.; Raju, A.; Don, J.; Schork, N.J.; Gerhard, G.S.; DiStefano, J.K. Hepatic PEMT Expression Decreases with Increasing NAFLD Severity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9296. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; et al. Polymorphism of the PEMT gene and susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1266–1271.

- Bale, G.; Vishnubhotla, R.V.; Mitnala, S.; Sharma, M.; Padaki, R.N.; Pawar, S.C.; Duvvur, R.N. Whole-Exome Sequencing Identifies a Variant in Phosphatidylethanolamine N-Methyltransferase Gene to be Associated with Lean-Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2019, 9, 561–568. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, K.A.; et al. Identification of new genetic polymorphisms that alter the dietary requirement for choline and vary in their distribution across ethnic and racial groups. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 2970–2978.

- Dong, H.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Hirose, A.; Nozaki, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Ono, M.; Akisawa, N.; Iwasaki, S.; Saibara, T.; et al. The phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase gene V175M single nucleotide polymorphism confers the susceptibility to NASH in Japanese population. J. Hepatol. 2007, 46, 915–920. [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, S.H. People with fatty liver are more likely to have the PEMT rs7946 SNP, yet populations with the mutant allele do not have fatty liver. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 2181–2182. [CrossRef]

- Resseguie, M.E.; da Costa, K.-A.; Galanko, J.A.; Patel, M.; Davis, I.J.; Zeisel, S.H. Aberrant estrogen regulation of PEMT results in choline deficiency-associated liver dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 1649–1658. [CrossRef]

- Resseguie, M.; Song, J.; Niculescu, M.D.; Costa, K.-A.; Randall, T.A.; Zeisel, S.H. PhosphatidylethanolamineN-methyltransferase(PEMT)gene expression is induced by estrogen in human and mouse primary hepatocytes. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 2622–2632. [CrossRef]

- Guerrerio, A.L.; Colvin, R.M.; Schwartz, A.K.; Molleston, J.P.; Murray, K.F.; Diehl, A.; Mohan, P.; Schwimmer, J.B.; E Lavine, J.; Torbenson, M.S.; et al. Choline intake in a large cohort of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 892–900. [CrossRef]

- Mazidi, M.; Katsiki, N.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Banach, M. Adiposity May Moderate the Link Between Choline Intake and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 38, 633–639. [CrossRef]

- Setchell, K.D.R.; Cole, S.J. Variations in isoflavone levels in soy foods and soy protein isolates and issues related to isoflavone databases and food labeling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 4146–4155. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.-W.; Hendry, A. Hypolipidemic Effects of Soy Protein and Isoflavones in the Prevention of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease- A Review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Setchell, K.D.; Brown, N.M.; Zimmer-Nechemias, L.; Brashear, W.T.; E Wolfe, B.; Kirschner, A.S.; E Heubi, J. Evidence for lack of absorption of soy isoflavone glycosides in humans, supporting the crucial role of intestinal metabolism for bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 447–453. [CrossRef]

- Setchell, K.D. and C. Clerici, Equol: history, chemistry, and formation. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1355S–62S.

- Setchell, K.D. The history and basic science development of soy isoflavones. Menopause 2017, 24, 1338–1350. [CrossRef]

- Arai, Y.; Uehara, M.; Sato, Y.; Kimira, M.; Eboshida, A.; Adlercreutz, H.; Watanabe, S. Comparison of isoflavones among dietary intake, plasma concentration and urinary excretion for accurate estimation of phytoestrogen intake.. J. Epidemiology 2000, 10, 127–135. [CrossRef]

- Mayo, B.; Vázquez, L.; Flórez, A.B. Equol: A Bacterial Metabolite from The Daidzein Isoflavone and Its Presumed Beneficial Health Effects. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2231. [CrossRef]

- Akahane, T.; Kaya, D.; Noguchi, R.; Kaji, K.; Miyakawa, H.; Fujinaga, Y.; Tsuji, Y.; Takaya, H.; Sawada, Y.; Furukawa, M.; et al. Association between Equol Production Status and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11904. [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.; Chen, C.; Hu, Y.-Y.; Feng, Q. Protective effect of genistein on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 109047. [CrossRef]

- Hakkak, R.; Spray, B.; Børsheim, E.; Korourian, S. Diet Containing Soy Protein Concentrate with Low and High Isoflavones for 9 Weeks Protects against Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Steatosis Using Obese Zucker Rats. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 913571. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Kumari, S.; Gu, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, X.; Meng, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Soy Food Intake Is Inversely Associated with Newly Diagnosed Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in the TCLSIH Cohort Study. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 3280–3287. [CrossRef]

- Eslami, O.; Shidfar, F.; Maleki, Z.; Jazayeri, S.; Hosseini, A.F.; Agah, S.; Ardiyani, F. Effect of Soy Milk on Metabolic Status of Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 38, 51–58. [CrossRef]

- Deibert, P.; Lazaro, A.; Schaffner, D.; Berg, A.; Koenig, D.; Kreisel, W.; Baumstark, M.W.; Steinmann, D.; Buechert, M.; Lange, T. Comprehensive lifestyle intervention vs soy protein-based meal regimen in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 1116–1131. [CrossRef]

- Maleki, Z.; Jazayeri, S.; Eslami, O.; Shidfar, F.; Hosseini, A.F.; Agah, S.; Norouzi, H. Effect of soy milk consumption on glycemic status, blood pressure, fibrinogen and malondialdehyde in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 44, 44–50. [CrossRef]

- Kani, A.H.; Alavian, S.M.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Adibi, P.; Haghighatdoost, F.; Azadbakht, L. Effects of a Low-Calorie, Low-Carbohydrate Soy Containing Diet on Systemic Inflammation Among Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Parallel Randomized Clinical Trial. Horm. Metab. Res. 2017, 49, 687–692. [CrossRef]

- Kani, A.H.; Alavian, S.M.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Adibi, P.; Azadbakht, L. Effects of a novel therapeutic diet on liver enzymes and coagulating factors in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A parallel randomized trial. Nutrition 2014, 30, 814–821. [CrossRef]

- Setchell, K.D.R.; Brown, N.M.; Lydeking-Olsen, E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol—A Clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 3577–3584. [CrossRef]

- Barańska, A.; Kanadys, W.; Bogdan, M.; Stępień, E.; Barczyński, B.; Kłak, A.; Augustynowicz, A.; Szajnik, M.; Religioni, U. The Role of Soy Isoflavones in the Prevention of Bone Loss in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4676. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-R.; Chen, K.-H. Utilization of Isoflavones in Soybeans for Women with Menopausal Syndrome: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3212. [CrossRef]

- Kanadys, W.; Barańska, A.; Błaszczuk, A.; Polz-Dacewicz, M.; Drop, B.; Malm, M.; Kanecki, K. Effects of Soy Isoflavones on Biochemical Markers of Bone Metabolism in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 5346. [CrossRef]

- Khapre, S.; Deshmukh, U.; Jain, S. The Impact of Soy Isoflavone Supplementation on the Menopausal Symptoms in Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Women. J. Mid-life Heal. 2022, 13, 175–184. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.I.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, I.; Yun, J.; Kim, E.H.; Seo, S.K. Efficacy and Safety of a Standardized Soy and Hop Extract on Menopausal Symptoms: A 12-Week, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2021, 27, 959–967. [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, P.; Puga-Olguín, A.; Rodríguez-Landa, J.F.; Zepeda, R.C. Genistein as Potential Therapeutic Candidate for Menopausal Symptoms and Other Related Diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 3892. [CrossRef]

- Taku, K.; et al. Extracted or synthesized soybean isoflavones reduce menopausal hot flash frequency and severity: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause 2012, 19, 776–790.

- Boutas, I.; Kontogeorgi, A.; Dimitrakakis, C.; Kalantaridou, S.N. Soy Isoflavones and Breast Cancer Risk: A Meta-analysis. Vivo 2022, 36, 556–562. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, F.; Gao, J.; Shan, B.; Ren, Y.; Wang, H.; Gao, Y. Oral isoflavone supplementation on endometrial thickness: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 17369–17379. [CrossRef]

- Ollberding, N.J.; Lim, U.; Wilkens, L.R.; Setiawan, V.W.; Shvetsov, Y.B.; Henderson, B.E.; Kolonel, L.N.; Goodman, M.T. Legume, soy, tofu, and isoflavone intake and endometrial cancer risk in postmenopausal women in the multiethnic cohort study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 104, 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Llaha, F.; Zamora-Ros, R. The Effects of Polyphenol Supplementation in Addition to Calorie Restricted Diets and/or Physical Activity on Body Composition Parameters: A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 84. [CrossRef]

- Finkeldey, L.; Schmitz, E.; Ellinger, S. Effect of the Intake of Isoflavones on Risk Factors of Breast Cancer—A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Intervention Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2309. [CrossRef]

- Lacourt-Ventura, M.Y.; Vilanova-Cuevas, B.; Rivera-Rodríguez, D.; Rosario-Acevedo, R.; Miranda, C.; Maldonado-Martínez, G.; Maysonet, J.; Vargas, D.; Ruiz, Y.; Hunter-Mellado, R.; et al. Soy and Frequent Dairy Consumption with Subsequent Equol Production Reveals Decreased Gut Health in a Cohort of Healthy Puerto Rican Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 8254. [CrossRef]

- Khankari, N.K.; Yang, J.J.; Sawada, N.; Wen, W.; Yamaji, T.; Gao, J.; Goto, A.; Li, H.-L.; Iwasaki, M.; Yang, G.; et al. Soy Intake and Colorectal Cancer Risk: Results from a Pooled Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies Conducted in China and Japan. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 2442–2450. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.-Y.; Ho, S.C.; Cheng, A.; Kwok, C.; Cheung, K.L.; He, Y.-Q.; Lee, R.; Yeo, W. The association between soy isoflavone intake and menopausal symptoms after breast cancer diagnosis: a prospective longitudinal cohort study on Chinese breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 181, 167–180. [CrossRef]

- Quaas, A.; Kono, N.; Mack, W.; Hodis, H.; Paulson, R.; Shoupe, D. The effect of isoflavone soy protein (ISP) supplementation on endometrial thickness, hyperplasia and endometrial cancer risk in postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 97, S6. [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.M.; Lampe, J.W.; Newton, K.M.; Gundersen, G.; Fuller, S.; Reed, S.D.; Frankenfeld, C.L. Being overweight or obese is associated with harboring a gut microbial community not capable of metabolizing the soy isoflavone daidzein to O- desmethylangolensin in peri- and post-menopausal women. Maturitas 2017, 99, 37–42. [CrossRef]

- Frankenfeld, C.L.; Atkinson, C.; Wähälä, K.; Lampe, J.W. Obesity prevalence in relation to gut microbial environments capable of producing equol or O-desmethylangolensin from the isoflavone daidzein. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 526–530. [CrossRef]

- Newton, K.M.; Reed, S.D.; Uchiyama, S.; Qu, C.; Ueno, T.; Iwashita, S.; Gunderson, G.; Fuller, S.; Lampe, J.W. A cross-sectional study of equol producer status and self-reported vasomotor symptoms. Menopause 2015, 22, 489–495. [CrossRef]

- Barnard, N.D.M.; Kahleova, H.; Holtz, D.N.B.; Znayenko-Miller, T.M.; Sutton, M.; Holubkov, R.; Zhao, X.; Galandi, S.; Setchell, K.D.R.P. A dietary intervention for vasomotor symptoms of menopause: a randomized, controlled trial. Menopause 2022, 30, 80–87. [CrossRef]

- Panneerselvam, S.; Packirisamy, R.M.; Bobby, Z.; Jacob, S.E.; Sridhar, M.G. Soy isoflavones ( Glycine max ) ameliorate hypertriglyceridemia and hepatic steatosis in high fat-fed ovariectomized Wistar rats (an experimental model of postmenopausal obesity). J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 38, 57–69. [CrossRef]

- de Kleijn, M.J.; et al. Intake of dietary phytoestrogens is low in postmenopausal women in the United States: the Framingham study(1-4). J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1826–1832.

- Messina, M. Soy and Health Update: Evaluation of the Clinical and Epidemiologic Literature. Nutrients 2016, 8, 754. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L.M.; Choi, M.S.; Cross, T.-W.L. Maximizing the Estrogenic Potential of Soy Isoflavones through the Gut Microbiome: Implication for Cardiometabolic Health in Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients 2022, 14, 553. [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.A.; Lin, J.; Qi, Q.; Usyk, M.; Isasi, C.R.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Derby, C.A.; Santoro, N.; Perreira, K.M.; Daviglus, M.L.; et al. Menopause Is Associated with an Altered Gut Microbiome and Estrobolome, with Implications for Adverse Cardiometabolic Risk in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. mSystems 2022, 7, e0027322. [CrossRef]

- Schwimmer, J.B.; Johnson, J.S.; Angeles, J.E.; Behling, C.; Belt, P.H.; Borecki, I.; Bross, C.; Durelle, J.; Goyal, N.P.; Hamilton, G.; et al. Microbiome Signatures Associated With Steatohepatitis and Moderate to Severe Fibrosis in Children With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 1109–1122. [CrossRef]

- Boursier, J.; Mueller, O.; Barret, M.; Machado, M.; Fizanne, L.; Araujo-Perez, F.; Guy, C.D.; Seed, P.C.; Rawls, J.F.; David, L.A.; et al. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology 2016, 63, 764–775. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-C.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Lin, C.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Wu, Y.-J.; Yong, C.-C.; Chen, K.-D.; Chuah, S.-K.; Yao, C.-C.; Huang, P.-Y.; et al. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study in Taiwan. Nutrients 2020, 12, 820. [CrossRef]

- Le Roy, T.; Llopis, M.; Lepage, P.; Bruneau, A.; Rabot, S.; Bevilacqua, C.; Martin, P.; Philippe, C.; Walker, F.; Bado, A.; et al. Intestinal microbiota determines development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Gut 2012, 62, 1787–1794. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wu, N.; Wang, X.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Dysbiosis gut microbiota associated with inflammation and impaired mucosal immune function in intestine of humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, srep08096. [CrossRef]

- Mouzaki, M.; Wang, A.Y.; Bandsma, R.; Comelli, E.M.; Arendt, B.M.; Zhang, L.; Fung, S.; Fischer, S.E.; McGilvray, I.G.; Allard, J.P. Bile Acids and Dysbiosis in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0151829–e0151829. [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Microbiota and diabetes: an evolving relationship. Gut 2014, 63, 1513–1521. [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.; Shi, J.; Fuhrman, B.; Xu, X.; Veenstra, T.D.; Gail, M.H.; Gajer, P.; Ravel, J.; Goedert, J.J. Fecal microbial determinants of fecal and systemic estrogens and estrogen metabolites: a cross-sectional study. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 253–253. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Sun, Q.; Qin, P.; Wang, Q. Compositional and functional features of the female premenopausal and postmenopausal gut microbiota. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 2655–2664. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Marcos, J.A.; Rangel-Zuñiga, O.A.; Jimenez-Lucena, R.; Quintana-Navarro, G.M.; Garcia-Carpintero, S.; Malagon, M.M.; Landa, B.B.; Tena-Sempere, M.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; et al. Influence of gender and menopausal status on gut microbiota. Maturitas 2018, 116, 43–53. [CrossRef]

- Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Arnoriaga-Rodríguez, M.; Luque-Córdoba, D.; Priego-Capote, F.; Pérez-Brocal, V.; Moya, A.; Burokas, A.; Maldonado, R.; Fernández-Real, J.-M. Gut microbiota steroid sexual dimorphism and its impact on gonadal steroids: influences of obesity and menopausal status. Microbiome 2020, 8, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.; Santoro, N.; Kaplan, R.C.; Qi, Q. Spotlight on the Gut Microbiome in Menopause: Current Insights. Int. J. Women's Heal. 2022, ume 14, 1059–1072. [CrossRef]

- Sharpton, S.R.; et al. Gut microbiome-targeted therapies in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 139–149.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J. The clinical effect of probiotics on patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 14960–14973.

- Szulińska, M.; Łoniewski, I.; Van Hemert, S.; Sobieska, M.; Bogdański, P. Dose-Dependent Effects of Multispecies Probiotic Supplementation on the Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Level and Cardiometabolic Profile in Obese Postmenopausal Women: A 12-Week Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 773. [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, S.T.A.; Silva-Sperb, A.S.; Moraes, H.A.; Longo, L.; de Moura, B.C.; Michalczuk, M.T.; Uribe-Cruz, C.; Cerski, C.T.S.; da Silveira, T.R.; Dall'Alba, V.; et al. Oral 24-week probiotics supplementation did not decrease cardiovascular risk markers in patients with biopsy proven NASH: A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study. Ann. Hepatol. 2023, 28, 100769. [CrossRef]

- Grossman, D.C.; et al. Hormone Therapy for the Primary Prevention of Chronic Conditions in Postmenopausal Women: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2017, 318, 2224–2233.

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S.; Liao, J.; Ye, Z.; Mao, L. Efficacy of probiotics on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2023, 102, e32734. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).