Submitted:

15 May 2023

Posted:

17 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

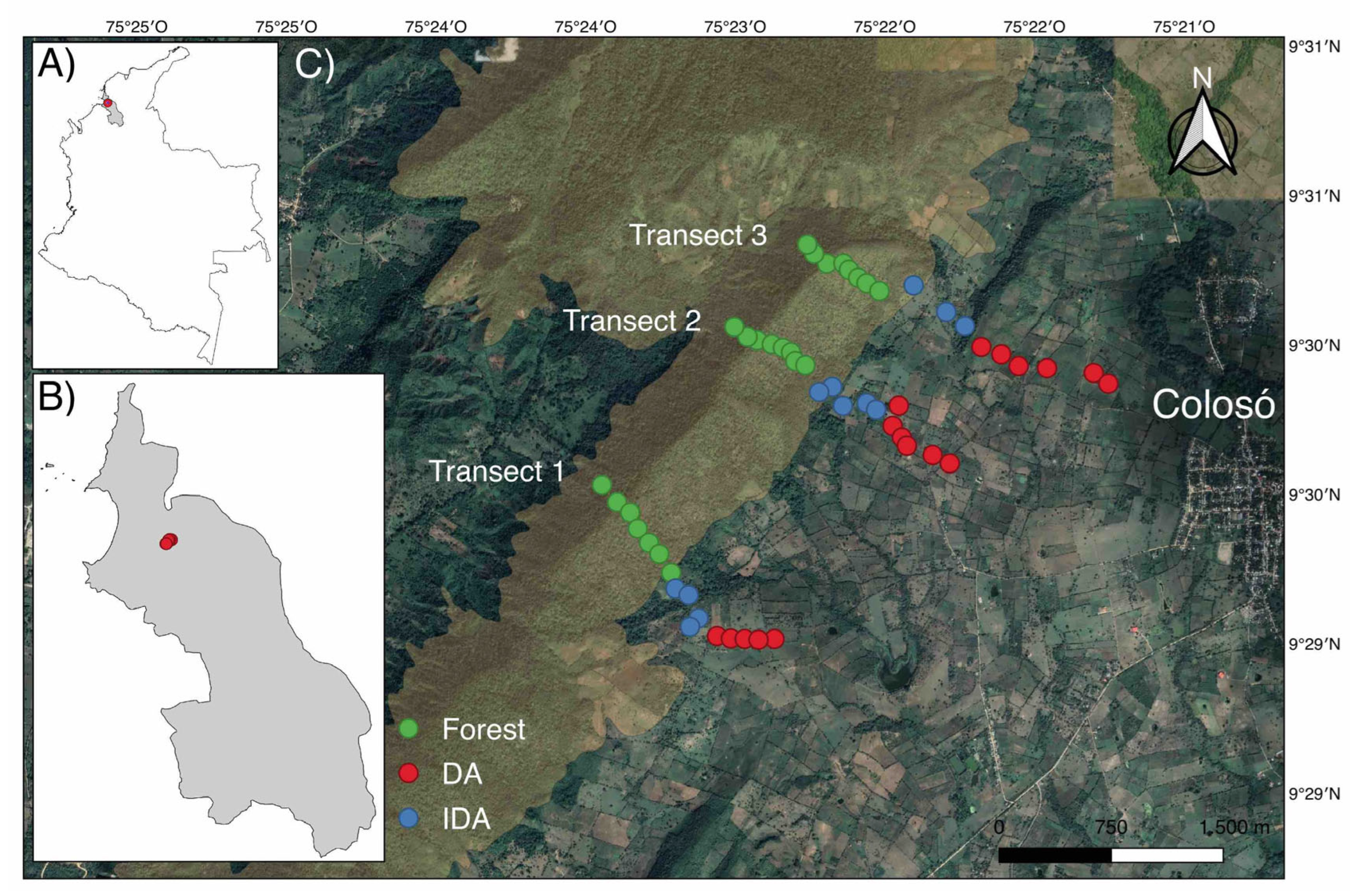

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Biological Material

2.3. Taxonomical Composition

2.4. Community Structure Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Taxonomic Composition

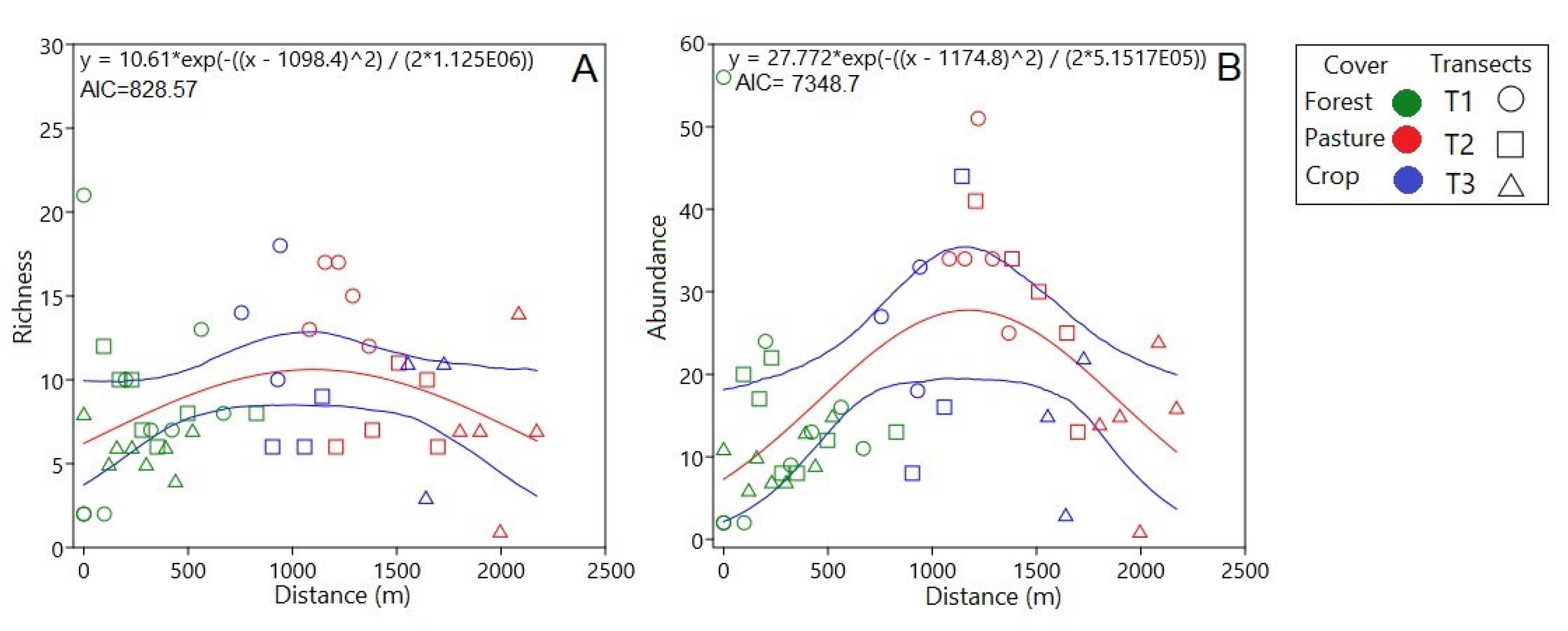

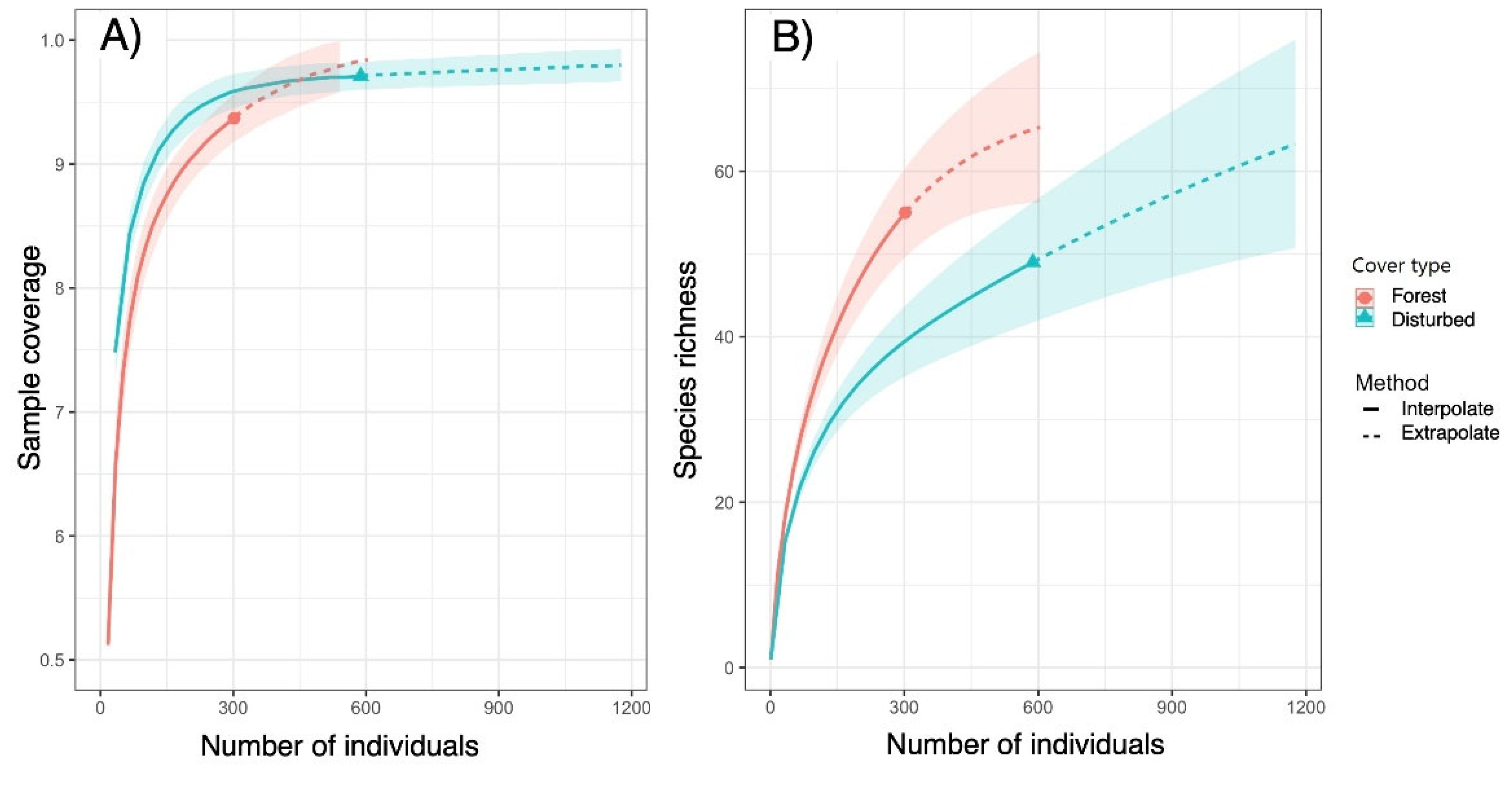

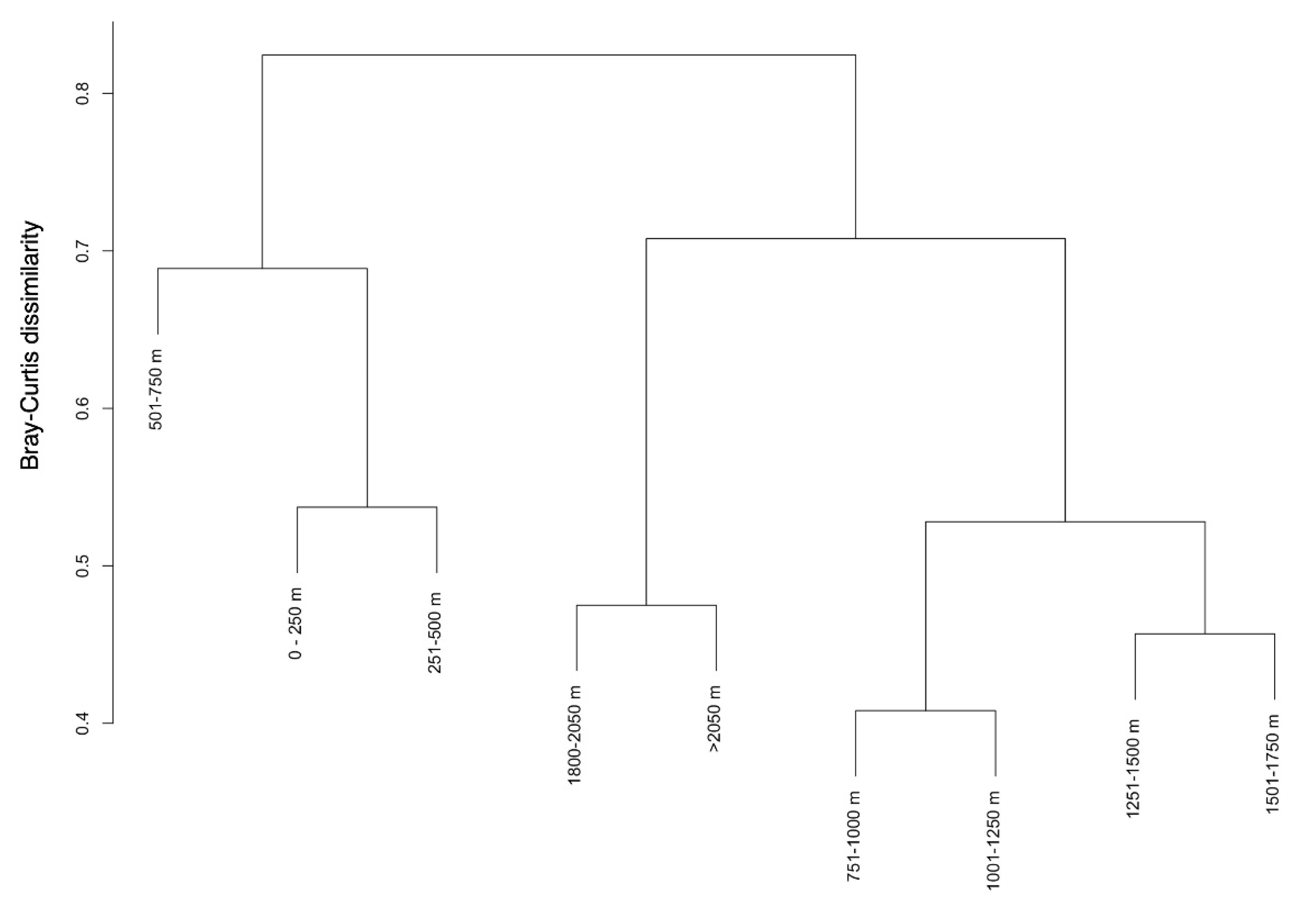

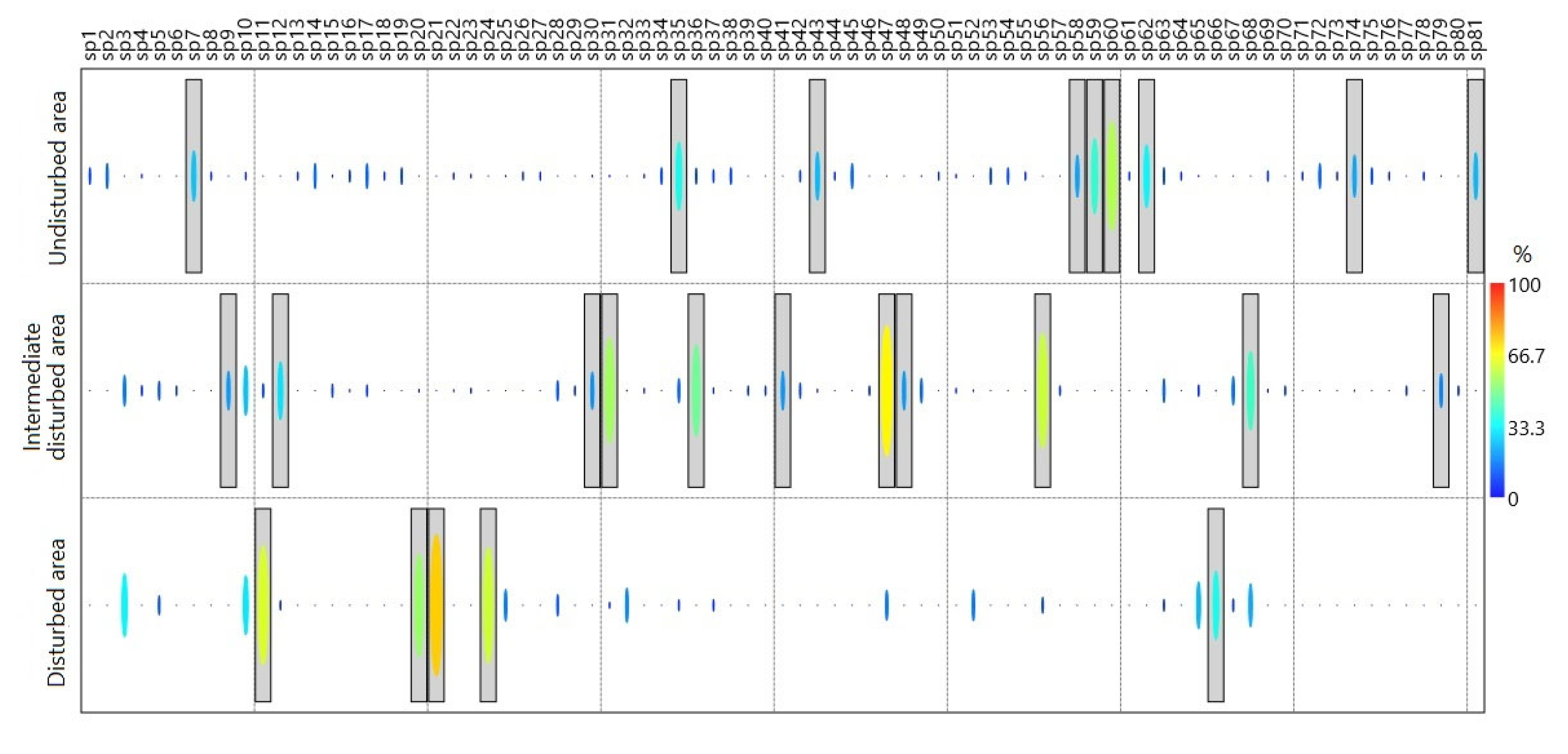

3.2. Ecological Structure of Communities

4. Discussion

4.1. Taxonomic Composition

4.2. Community Structure Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Linares-Palomino, R.; Oliveira-Filho, A.T.; Pennington, R.T. Neotropical seasonally dry forests: diversity, endemism, and biogeography of woody plants. In Seasonally dry tropical forest. Ecology and conservation, Dirzo, R., Young, H., Mooney, H., Ceballos, G., Eds.; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics: 2011; pp. 3–21.

- Banda, K.; Delgado-Salinas, A.; Dexter, K.G.; Linares-Palomino, R.; Oliveira-Filho, A.; Prado, D.; Pullan, M.; Quintana, C.; Riina, R.; Rodríguez, G.M.; et al. Plant diversity patterns in neotropical dry forests and their conservation implications. Science 2016, 353, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizano, C.; Garcia, H. El Bosque Seco Tropical en Colombia; Instituto de Investigacion de Recursos Biologicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH): Bogota, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- García, H.; Corzo, G.; Isaac, P.; Etter, A. Distribución y estado actual de los remanentes del bioma de bosque seco tropical en Colombia: Insumos para su conservación. In El bosque seco tropical en Colombia, Pizano, C., García, H., Eds.; Instituto de Investigacion de Recursos Biológicos, Alexander von Humboldt: Bogota, D.C, 2014; Volume 90, pp. 228–251. [Google Scholar]

- Olascuaga, D.; Sánchez-Montaño, R.; Mercado-Gómez, J. Análisis de la vegetación sucesional en un fragmento de bosque seco tropical en Toluviejo-Sucre (Colombia). Colombia forestal 2016, 19, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.; Pickett, S. Natural disturbance and patch dynamics: an introduction. In The Ecology of Natural Disturbance and Patch Dynamics, Pickett, S.T.A., White, P.S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 1985; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Séguin, A.; Gravel, D.; Archambault, P. Effect of disturbance regime on alpha and beta diversity of rock pools. Diversity 2014, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socolar, J.B.; Gilroy, J.J.; Kunin, W.E.; Edwards, D.P. How should beta-diversity inform biodiversity conservation? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2016, 31, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.A.; Chase, J.M.; Crandall, R.M.; Jiménez, I. Disturbance alters beta-diversity but not the relative importance of community assembly mechanisms. Journal of Ecology 2015, 103, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornelas, M. Disturbance and change in biodiversity. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 2010, 365, 3719–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendix, J.; Wiley, J.J.; Commons, M.G. Intermediate disturbance and patterns of species richness. Physical Geography 2017, 38, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillan, E.; Seshan, H.; Constancias, F.; Drautz-Moses, D.I.; Wuertz, S. Frequency of disturbance alters diversity, function, and underlying assembly mechanisms of complex bacterial communities. Biofilms and Microbiomes 2019, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, J.R.; Lindegarth, M.; Jonsson, P.R.; Pavia, H. Disturbance-diversity models: what do they really predict and how are they tested? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2012, 279, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguso, R.A.; Llorente-Bousquets, J. The Butterflies (Lepidoptera) of the Tuxtlas Mts., Veracruz, México, Revisited: Species-Richness and Habitat Disturbance. The Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 1990, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, K.; Jaros̆, J.; Havelka, J.; Leps̆, J. Effect of small-scale disturbance on butterfly communities of an Indochinese montane rainforest. Biological Conservation 1997, 80, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo-Fordjour, P.; Osei, B.; Kpontsu, E. Butterfly community assemblages in relation to human disturbance in a tropical upland forest in Ghana, and implications for conservation. Journal of Insect Biodiversity 2015, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Cortés, J.L.; Caballero, U.; Miss-Barrera, I.D.; Girón-Intzin, M. Preserving butterfly diversity in an ever expanding urban landscape? A case study in the highlands of Chiapas, MÈxico. Journal of Insect Conservation 2019, 23, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellend, M.; Verheyen, K.; Flinn, K.; Jacquemyn, H.; Kolb, A.; Van calster, H.; Peterken, H.; Graae, B.; Bellemare, J.; Honnay, O.; et al. Homogenization of forest plant communities and weakening of species–environment relationships via agricultural land use. Journal of Ecology 2007, 95, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazoul, J. Impact of logging on the richness and diversity of forest butterflies in a tropical dry forest in Thailand. Biodiversity & Conservation 2002, 11, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Gómez, J.; Prieto-Torres, D.A.; Gonzalez, M.; Morales-Puentes, M.; Escalante, T.; Rojas, O. Climatic affinities of neotropical species of Capparaceae: an approach from ecological niche modelling and numerical ecology. Botanical Journal Of The Linnean Society 2020, 193, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C. Exploring the phylogenetic structure of ecological communities: an example for rain forest trees. The American Naturalist 2000, 156, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Svenning, J.-C.; Mi, X.; Jia, Q.; Rao, M.; Ren, H.; Bebber, D.P.; Ma, K. Anthropogenic disturbance shapes phylogenetic and functional tree community structure in a subtropical forest. Forest Ecology and Management 2014, 313, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo-Silva, E.E.; Santos, B.A.; Arroyo-Rodríguez, V.; Melo, F.P.L.; Faria, D.; Cazetta, E.; Mariano-Neto, E.; Hernández-Ruedas, M.A.; Tabarelli, M. Phylogenetic dimension of tree communities reveals high conservation value of disturbed tropical rain forests. Diversity and Distributions 2018, 24, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, M.F.; Donoso, D.; Levy, E.; Mena, S.; Rodriguez, J.; Willmott, K. Assembly mechanisms of neotropical butterfly communities along an environmental gradient. bioRxiv 2019, 632067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, L.; Alvarez, N.; Espíndola, A.; Pottier, J.; Dubuis, A.; Pradervand, J.-N.; Guisan, A. Phylogenetic alpha and beta diversities of butterfly communities correlate with climate in the western Swiss Alps. Ecography 2013, 36, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Gómez, J.; Solano, C.; Hoffman, W. Recursos florales usados por dos especies de Bombus en un fragmento de bosque subandino (Pamplonita-Colombia). Recia 2017, 9, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sampedro, M.A.; Gómez, F.H.; Ballut, D.G. Estado de la vegetación en localidades abandonadas por “desplazamiento”, en los montes de María Sucre, Colombia Recia 2014, 6, 184–193. 6.

- Aguilera, M. La Mojana: riqueza natural y potencial económico; Banco de la República. Serie de documentos de trabajo sobre economía regional Nº 48. Cartagena, Colombia: 2005; p. 122.

- Herazo-Vitola, F.; Mendoza-Cifuentes, H.; Mercado-Gómez, J. Estructura y composición florística del bosque seco tropical en los Montes de María (Sucre – Colombia). Ciencia en desarrollo 2017, 8, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.; Gompert, Z.; Jiggins, C.; Willmott, K. Mutualistic Interactions Drive Ecological Niche Convergence in a Diverse Butterfly Community. PLoS Biol 2008, 6, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, L.; Iserhard, C.; Santos, J.; Junia, O.; Danilo, R.; Douglas, A.; Augusto, H.; Onildo, a.-F.; Gustavo, A.; Mauricio, U.-P. Studies with butterfly bait traps: an overview. Revista Colombiana de Entomología 2014, 40, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Fraija, N.; Medina, G. Caracterización de la fauna del orden lepidóptera (rhopalocera) en cinco diferentes localidades de los llanos orientales colombianos. Acta Biológica Colombiana 2006, 11, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Espinoza, R.; Condo, F. Sinopsis de la familia Acanthaceae en el Perú. Revista Forestal del Perú 2019, 34, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borror, D.; Delong, D.; Triplehorn, C.; Johnson, N. An Introduction of the study of insects; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College: Philadelphia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Borror, D.; Triplehorn, C.; Johnson, N. An Introduction to the Study of Insects; Hartcourt Brace Jovanovich College: Philadelphia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Triplehorn, C.; Johnson, N. Borror and DeLong's lntroduction to the study of insects, Seventh Edition ed.; Thomson Brooks Cole, USA, 2005.

- Warren, A.D.; Davis, K.J.; Stangeland, E.M.; Pelham, J., P; Willmott, K.R.; Grishin, N.V. Butterflies of America. Available online: http://www.butterfliesofamerica.com/ (accessed on Illustrated Lists of American Butterflies).

- Le Crom, J.F.; Constantino, L.M.; Salazar, J.A. Mariposas de Colombia Tomo 1 Papilionoidae; CARLEC Ltda: Bogota, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Le Crom, J.F.; Constantino, L.M.; Salazar, J.A. Mariposas de Colombia Tomo 2: Pieridae; CARLEC Ltda: Bogota, Colombia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lamas, G. Atlas of Neotropical Lepidoptera. In CheckList: Part 4A Hesperioidea-Papilionoidea, J, H., Ed.; Association for Tropical Lepidoptera Scientific, 2004; p. 479.

- Andrade-C, M.; Henao-Bañol, E.; Triviño, P. Técnicas y Procesamiento para la Recoleccion, Preservacion y Montaje de Mariposas en estudios de Biodiversidad y Conservcion (Lepidoptera:Hesperioidea-Papilionoidea) Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc 2013, 37, 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, A.; Gotelli, N.J.; C, H.T.; Elizabeth, S.; MA, K.H.; Colwell, R.K.; Ellison, A.M. Rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers: a framework for sampling and estimation in species diversity studies. Ecological Monographs 2014, 84, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.; Ma, K.; Chao, A. iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2016, 7, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.; Chao, A.; Gotelli, N.; Shang-Yi, L.; Chang Xuan, M.; Robin L, C.; Jhon T, L. Models and estimators linking individual-based and sample-based rarefaction, extrapolation and comparison of assemblages. Journal of Plant Ecology 2012, 5, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Hidalgo, J. Las divisorias de aguas como elementos del paisaje. Geographycalia 1990, 27, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. In Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike, Parzen, E., Tanabe, K., Kitagawa, G., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, 1974; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Baselga, A. Partitioning the turnover and nestedness components of beta diversity. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2010, 19, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, A.; Orme, C.D.L. betapart: an R package for the study of beta diversity. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2012, 3, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, L. Partitioning diversity into independent alpha and beta components. Ecology 2007, 88, 2427–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcon, E.; Hérault, B. entropart: An R Package to Measure and Partition Diversity. 2015 2015, 67, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electron 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.; Castillo-Campos, G.; Verdú, J. Taxonomic diversity as complementary information to assess plant species diversity in secondary vegetation and primary tropical deciduous forest. Journal of Vegetation Science 2009, 20, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, R.; Clarke, R. New ’biodiversity’ measures reveal a decrease in taxonomic distinctness with increasing stress. Marine Ecology Progress Series 1995, 129, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.M.; Cadotte, M.W.; Carvalho, S.B.; Davies, T.J.; Ferrier, S.; Fritz, S.A.; Grenyer, R.; Helmus, M.R.; Jin, L.S.; Mooers, A.O.; et al. A guide to phylogenetic metrics for conservation, community ecology and macroecology. Biological Reviews 2017, 92, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. A further biodiversity index applicable to species lists: variation in taxonomic distinctness. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2001, 216, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Castillo-Campos, G.; Verdú, J. Taxonomic diversity as complementary information to assess plant species diversity in secondary vegetation and primary tropical deciduous forest. Journal of vegetation Science 2009, 20, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrêne, M.; Legendre, P. Species assemblages and indicator species: The need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecological Monographs 1997, 67, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Valdivia, N.; Ochoa-Gaona, S.; Pozo, C.; Gordon Ferguson, B.; Rangel-Ruiz, L.J.; Arriaga-Weiss, S.L.; Ponce-Mendoza, A.; Kampichler, C. Indicadores ecológicos de hábitat y biodiversidad en un paisaje neotropical: perspectiva multitaxonómica. Revista de Biología Tropical 2011, 59, 1433–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henao-Bañol, E.R.; Gantiva-Q. , C.H. Mariposas (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea-Papilionoidae) del bosque seco tropical (BST) en Colombia. Conociendo la diversidad en un ecosistema amenazado. Boletín Científico Centro de Museos Museo de Historia Natural 2020, 24, 150–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, C.; Chacon, P.; Giraldo, A. Estudio de la comunidad de Lepidopteros diurnos en zonas naturales y sistemas productivos del municipio de Caloto ( Cauca, Colombia). Bol.cient.mus.hist.nat. 2009, 13, 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Gaviria-Ortiz, F.; Henao-Bañol, E. Diversidad de mariposas diurnas (Hesperioidea-Papilionoidea) del parque natural regional el vinculo (Buga-Valle del Cauca). Boletín Científico centro de Museos Museo de Historia Natural 2011, 15, 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Henao-Bañol, E.R.; Andrade-C, M. Registro del género Megaleas (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae: Hesperiinae) para Colombia con descripción de una nueva especie. Revista Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas 2013, 37, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, S.; Muriel, S.; Palacio, J. Diversidad de Lepidopteros diurnos en una área de Bosque Seco Tropical del Occidente antioqueño Actualidades biologicas 2009, 90, 31–41. 90.

- Peña, J.; Reinoso, G. Mariposas diurnas de tres fragmentos de bosque seco tropical del alto valle del Magdalena. Tolima-Colombia. Revista de la Asociación Colombiana de Ciencias Biológicas 2016, 1, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Prince-Chacon, S.; Vargas-Zapata, M.; Salazar-E, J.; Martinez-Hernandez, N. Mariposas Papilionoidea y Hesperioidea (Insecta:Lepidoptera) en dos fragmentos de Bosque Seco Tropical en Corrales de San Luis, Atlantico, Colombia. Boletin de la Sociedad Entomologica Aragonesa 2011, 48, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Pinilla, L.; Mahecha, J.; Dumar, R.; Rios-Malaver, I. Diversidad de mariposas en un paisaje de bosque seco tropical, en la Mesa de los Santos, Santander, Colombia (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea). SHILAP Rev Lepid 2017, 45, 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Zapata, M.; Boom-Urueta, C.; Seña-Ramos, L.; Echeverry-Iglesias, A.; Martinez - Hernandez, N. Composicion vegetal, preferencias alimenticias y abundancia de Biblidinae (Lepidoptera:Nymphalidae) en un fragmento de bosque seco tropical en el departamento del Atlantico, Colombia. Acta Biol Colomb 2015, 20, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, P.; Dahners, H.W. Eumaeini (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) del cerro San Antonio: Dinámica de la riqueza y comportamiento de Hilltopping Rev Colomb Entomol 2006, 32, 179–190. 32.

- Montero, F.; Moreno, M.; Gutiérrez, L. Mariposas (Lepidoptera: hesperioidea y papilionoidea) asociadas a fragmentos de bosque seco tropical en el departamento del Atlántico, Colombia. Boletín Científico Centro de Museos Museo de Historia Natural 2009, 13, 157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Zapata, M.A.; Martinez Hernandez, N.J.; Gutierrez Moreno, L.C.; Prince Chacon, S.; Herrera Colon, V.; Torres Periñan, L.F. Riqueza y Abundancia de Hesperioidea y Papilionoidea(Lepidoptera) en la Reserva Natural las Delicias, Santa Marta Magdalena, Colombia. Acta Biol. Colomb 2011, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Zapata, M.; Boom-Urueta, C.; Seña-Ramos, L.; Echeverry-Iglesias, A.; Martinez Hernandez, N. Composicion vegetal, preferencias alimenticias y abundancia de Biblidinae (Lepidoptera:Nymphalidae) en un fragmento de Bosque Seco Tropical en el departamento del Atlantico, Colombia. Acta Biologica Colombiana 2015, 20, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J.M. Bosque Seco Tropical en Colombia; Banco de Occidente: Cali, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, J. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science 1978, 199, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.; Schulze, C.H.; author_in_Japanese. Diversity of fruit-feeding butterflies (Nymphalidae) along a gradient of tropical rainforest succession in Borneo with some remarks on the problem of "pseudoreplicates". Lepidoptera Science 2000, 51, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanschoenwinkel, B.; Buschke, F.; Brendonck, L. Disturbance regime alters the impact of dispersal on alpha and beta diversity in a natural metacommunity. Ecology 2013, 94, 2547–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadotte, M.W.; Tucker, C.M. Should environmental filtering be abandoned? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2017, 32, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, J.; Melo, A.S.; Bini, L.M. Reconceptualising the beta diversity-environmental heterogeneity relationship in running water systems. Freshwater Biology 2015, 60, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavoine, S.; Baguette, M.; Stevens, V.M.; Leibold, M.A.; Turlure, C.; Bonsall, M.B. Life history traits, but not phylogeny, drive compositional patterns in a butterfly metacommunity. Ecology 2014, 95, 3304–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Hernández, C. Distintividad taxonómica: Evaluación de la diversidad en la estructura taxonómica en los ensambles. In La biodiversidad en un mundo cambiante: Fundamentos teóricos y metodológicos para su estudio, Moreno, C., Ed.; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo/Libermex: Ciudad de México, 2019; pp. 285–306. [Google Scholar]

- Angulo, D.F.; Ruiz-Sanchez, E.; Sosa, V. Niche conservatism in the Mesoamerican seasonal tropical dry forest orchid Barkeria (Orchidaceae). Evolutionary Ecology 2012, 26 991–1010.

- Swenson, N.G.; Enquist, B. Opposing assembly mechanisms in a Neotropical dry forest: implications for phylogenetic and functional community ecology. Ecology 2009, 90, 2161–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, N.J.B.; Adler, P.B.; Godoy, O.; James, E.C.; Fuller, S.; Levine, J.M. Community assembly, coexistence and the environmental filtering metaphor. Functional Ecology 2015, 29, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.J.; Graham, C.H. Niche conservatism: integrating evolution, ecology, and conservation biology. Annual review ecology and systematics 2005, 36, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.; Ackerly, D.; McPeek, M.; Donoghue, M. Phylogenies and community ecology. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 2002, 33, 475–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.H. Insects and mite pests in the human environment. In Urban entomology; Chapman & Hall: Gran Bretaña, 1996; p. 430. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez -Restrepo, L.; Chacon, P.; Constantino, L. Diversidad de Mariposas Diurnas ( lepidoptera:Papilionoidea y Hesperoidea) en Santiago de Cali, Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Entomologia 2007, 33, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagua, G. Comunidad de mariposas y artropodofauna asociada con el suelo de tres tipos de vegetación de la Serranía de Taraira (Vaupés, Colombia). Una prueba del uso de mariposas como bioindicadores. Revista Colombiana de Entomología. 1996, 22, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, L.L. Assesing treats and setting priorices for conservation. Conservation Biology 1991, 5, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adelpha fessonia ernestoi 1 | Euptoieta hegesia3 | Mesosemia carissima 1 |

| Adelpha iphicleola 1 | Eurema agave3 | Mestra hersilia3 |

| Agraulis vanillae3 | Eurema arbela 2 | Microtia elva3 |

| Anartia amathea3 | Eurema daira 2 | Morpho helenor 1 |

| Anartia jatrophae3 | Eurema elathea3 | Morpho helenor peleides 1 |

| Anteos maerula 3 | Fountainea halice 2 | Myscelia leucocyana 1 |

| Archaeoprepona demophon 1 | Glutophrissa drusilla 1 | Neographium anaxilaus 1 |

| Archaeoprepona demophoon 1 | Hamadryas februa ferentina 2 | Nica flavilla 1 |

| Aricoris erostratus3 | Hamadryas feronia 2 | Parides anchises serapis 2 |

| Ascia monuste 2 | Heliconius erato 2 | Parides eurimedes mycale 1 |

| Battus polydamas 2 | Heliconius ethilla 1 | Parides iphidamas 2 |

| Biblis hyperia3 | Heraclides thoasnealces3 | Phoebis agarithe3 |

| Caligo brasiliensis morpheus 1 | Hermeuptychia Hermes 1 | Phoebis argante 2 |

| Callicore pitheas 1 | Historis odius3 | Phoebis sennae3 |

| Chlosyne lacinia 2 | Hypna clytemnestra 2 | Prepona laertes 2 |

| Chlosyne poecile 2 | Itaballia demophile calydonia 2 | Pseudolycaena marsyas3 |

| Cissia themis 2 | Itaballia pandosia 1 | Pyrisitia dina 1 |

| Colobura dirce 1 | Janatella leucodesma 1 | Pyrisitia leuce 1 |

| Consul fabius 1 | Juditha sp.3 | Pyrrhogyra neaerea 1 |

| Danaus eresimus3 | Junonia evarete3 | Siderone galanthis 2 |

| Danaus gilippus 2 | Junonia genoveva3 | Siproeta stelenes 1 |

| Detritivora hermodora 2 | Leptotes cassius3 | Smyrna blomfildia 1 |

| Doxocopa pavon theodora 2 | Libytheana carinenta 1 | Strymon sp.3 |

| Dryadula phaetusa3 | Lycorea halia 2 | Taygetis laches 1 |

| Dryas iulia 2 | Marpesia chiron3 | Temenis laothoe 2 |

| Ectima erycinoides 1 | Melanis electron 1 | Thereus cithonius3 |

| Eunica tatila 1 | Memphis arginussa 1 | Zaretis ellos 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).