Introduction

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are the most common cause of chronic pain of non-dental origin, in the orofacial region. TMD is characterised by unclear, multifactorial aetiology and affects a significant number of people worldwide (incidence: 3.9%; prevalence: 4.6%) (1-3). TMD symptoms can be categorised into masticatory muscle-related symptoms and temporomandibular joint (TMJ)-related symptoms. Clinically, there is a pain in these areas, limitations in jaw movements, and occurrence of joint sounds. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD), a validated protocol used in clinical practice and research, consists of two subprotocols (4).

Axis I subprotocol includes a reliable screener for detecting any pain-related TMD (TMDp), as well as valid diagnostic criteria for distinguishing pain-related TMD from TMJ disorders (disc-displacements, degenerative joint diseases, and subluxation). Pain-related TMD includes masticatory muscles myalgia, arthralgia, which refers to pain in the TMJ, as well as a headache attributed to TMD (4).

Axis II, on the other hand, consists of screening and comprehensive self-report instruments assessing pain intensity, pain-related disability, psychological distress, jaw functional limitations, and oral behavioural habits. Painful symptoms in TMD frequently coexist and might be aggravated by parafunctional behaviours, activities of the mouth, beyond its original functions of chewing, talking and swallowing (5). They include bruxism, repetitive muscle activity that is accompanied by clenching or grinding the teeth and/or pushing the lower jaw while awake or during sleep (6). Psychological variables (such as anxiety and depression) and patients' susceptibility to stress are thought to be relevant in the aetiology of both oral behaviours (OB) and TMD (7). Therefore, the overlapping background of these two disorders and undoubted influence of stress depending on patients’ psychological profile is the reason why connection between OB and TMD is frequently studied (8).

Oxidative stress, defined as an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defense, has been considered as an important factor for the development and progression of various pathological conditions, including chronic pain disorders such as TMD (9). Oxidative stress is associated with inflammation and injury, as well as psychological stressors. For instance, it was found that intermittent exposure to hypobaric hypoxia, which is a stressful event, increases the level of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances and decreases antioxidative activity in the soleus muscle of a rat, suggesting increased levels of oxygen free radicals and presence of oxidative injury (10). Also, prolonged exposure to exogenous stress and psychological stressors leads to increased production of markers of oxidative DNA damage (11). The successful removal of ROS is regulated by the enzymatic antioxidant system, involving proteins wit enzymatic antioxidative properties, which are coded by corresponding genes Particular single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in those genes can modify the activity of critical antioxidant enzymes thus promoting imbalances in the cellular oxido-redox status. Certain genetic variability may predispose individuals to development and severity of certain diseases and influence susceptibility to environmental factors (12).

Although an impaired oxidative protective mechanism has been suggested as an aetiological risk factor for pain disorders such as fibromyalgia, headaches, and TMD, there has been limited research on SNP of genes coding for proteins with antioxidative properties involved in these disorders (13,14). So far, studies have shown that individuals with TMD tend to have higher salivary and serum levels of oxidative stress markers, such as malondialdehyde. There is, on the other hand, lower level of specific antioxidants and consequential decrease of antioxidant capacity compared to healthy controls (15,16). On the contrary, some studies have proposed a compensatory increase in the antioxidant defence, with higher salivary total antioxidant capacity in combination with higher salivary levels of oxidants in TMD patients compared to controls (17,18). Because TMD is linked to anxiety and depression, hypervigilance, and a tendency to somatization, it is important to mention the idea that oxidative damage might be involved in nervous system dysfunction. One study has demonstrated that the expression of genes involved in antioxidative metabolism: glutathione reductase 1 and glyoxalase 1 correlates with anxiety-related traits, with the activity of antioxidant enzymes being highest in the most anxious mice and lowest in the least anxious animals (19).

The cause-and-effect link between chronic pain, OB, psychological stress, and oxidative stress is currently debated, and further research is needed for better understanding of the precise mechanisms through which these conditions influence response to oxidative stress and/or vice versa. The presence of SNPs in genes coding enzymes with antioxidative properties, have been associated with various conditions. They may also be associated with TMD and OB (20-22). Furthermore, since certain patients are more influenced by aggravating factors such as psychological stress and OB, it is important to investigate the gene-behaviour associations in TMD patients.

The study aimed to investigate the distribution of SNPs in genes coding for antioxidant enzymes: catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1), and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) in TMDp patients and in healthy controls. The distribution of SNPs was also evaluated with respect to oral behavioural habits. Another aim was to investigate whether SNPs in these genes can be associated with the participants' psychological and psychosomatic characteristics.

The null hypothesis stated that the investigated SNPs of interest would not be associated to the presence of pain-related TMD or the frequency of harmful oral behaviours.

Materials & Methods

This case-control study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki at the School of Dental Medicine, University of Zagreb. The Ethics Committee at the School of Dental Medicine, University of Zagreb approved the study protocol (05- PA -30- VIII -6/2019). On January 4, 2021, the study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT046. The study protocol was developed in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies (23). Before participating in the study, each subject had to sign an informed consent form.

From January 2020 to September 2022, 85 subjects (76 females, 9 males) were selected from the group of patients referred to the Department of Dentistry at the Clinical Hospital Center Zagreb due to persistent orofacial pain. Participants had to be older than 18 years and had to be diagnosed according to DC/TMD with TMDp ̶ myalgia and/or arthralgia. The average pain on the numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) had to be >30 mm, the complaints had to last longer than three months, and the symptoms had to be persistent (4).

The following exclusion criteria were applied: age less than 18 years, the absence of first molars, removable dentures, bad oral hygiene, periodontal problems, orofacial pathology unrelated to the TMD diagnosis, pain present less than three months prior to the first examination, history of head and neck trauma, headache unrelated to TMD (according to International Classification of Headache Disorders, ICDH II), pain caused by systemic diseases, fibromyalgia, confirmed psychiatric disorders. Patients with a diagnosis of pain-free joint clicking and crepitation were also excluded from the study.

The control group (CTR) comprised 85 healthy participants (62 females, 23 males), students and staff of the School of Dental Medicine, University of Zagreb, and TMD-free patients from the Department of Dentistry at the Clinical Hospital Center Zagreb. All participants were over 18 years of age and in good general health. No history of orofacial pain or TMD was also considered as an inclusion criterion for the control group.

Diagnosis of temporomandibular disorders - clinical examination

Participants were examined by highly skilled and experienced examiners (IZA, EV, MZ) who followed the validated Croatian version of the DC/TMD protocol (24). The examination included palpation of the masticatory muscles and TMJ, assessment of mandibular movements, and evaluation of the existence and character of TMJ noises. To establish a definitive diagnosis of TMDp, a patient must confirm the presence of pain in the TMJ and/or masticatory muscles and pain modification (i.e. aggravation or alleviation) during movement, function or parafunction. Furthermore, during clinical examination, patient was required to confirm the place and site of the discomfort when triggered by the examiner's palpation or functional movements of the jaw. To successfully identify the primary problem of a patient, the discomfort felt by the patient had to be labelled as "familiar." The final diagnosis was determined according to the DC/TMD Diagnostic decision tree (4).

Assessment of psychosocial and psychosomatic characteristics

All participants, both TMDp patients and control subjects, were asked to complete questionnaires that were part of a self-report instrument set of the DC/TMD protocol (Axis II). The instruments used to assess the psychological status of participants were Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) for anxiety, and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression.

Additionally, for assessing psychosomatic characteristics, participants were asked to fill in two additional questionnaires - Somatosensory Amplification Scale (SSAS) for assessing somatization, and Brief Hypervigilance Scale (BHS) for assessing hypervigilance.

Patient Health Care Questionnaire-9, a nine-item instrument, is designed to screen for depressive symptoms. The Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7, a seven-item questionnaire, is used to assess the severity of anxiety symptoms. Both were based on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “0” not at all to “3” almost every day. The possible outcomes range for PHQ-9 was from 0 to 27, while GAD-7 values ranged from 0 to 21 (25,26).

Somatosensory Amplification Scale is a 10-item instrument designed to assess the tendency to detect somatic and visceral sensations and experience them as unusually intense. It consisted of 10 items with responses on a Likert scale from “0” never to “4” always and scores ranging from 0 to 40 (27).

The Brief Hypervigilance Scale is a tool used to assess the state of increased vigilance and arousal that can occur in response to perceived threats or stressors. It is a self-report 5-item questionnaire, each rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “0” not at all like me to “4” very much like me with scores ranging from 0 to 20 (28).

Assessment of oral behavioural habits

The Oral Behaviour Checklist (OBC), a part of the DC/TMD protocol, was used for identifying and quantifying the frequency of jaw overuse behaviour. It comprises 21 items in total. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 4, resulting in a total score range from 0 to 84. However, OBC can be separated into 2 categories: sleep-related oral behaviours and waking-state oral behaviours.

Sleep-related oral behaviours consist of two items: 1) teeth grinding and clenching during sleep and 2) potentially harmful sleeping positions for the masticatory system. Both items require information on the frequency of the specific behaviour, resulting in a score of 0 to 8 points.

The other 19 items focus on oral behaviours during wakefulness (waking-state oral behaviours) that could negatively affect the masticatory system, including activities involving the teeth, tongue, lips, throat, and jaw. Each item requires information on the frequency of the specific behaviour during the day over the preceding month (ranging from none to all of the time) and can lead to a score of 0 to 76 points (29).

Grouping of participants

Study participants were grouped according to pain presence into a pain-related TMD (TMDp, n=85) group and a healthy control group (CTR; n=85).

Additional grouping was made with respect to OBC scores. According to Ohrbach and Knibbe: Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) Scoring Manual for Self-Report Instruments (ACTA), the participants were divided into two groups: a “high-frequency parafunction” group (HFP; n=98) with OBC sum score 25–84 and a “low-frequency parafunction” (LFP; n=72) group, with OBC sum score 1–24.

Extraction of DNA and genotyping

Following a clinical examination, a buccal swab was collected from each participant with a soft nylon bristle brush (the Cytology Rambrush; (Mirandola, Italy, Rimos)). Buccal swab samples were placed into microtubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored at -20 °C for subsequent DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted using the commercially available QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (QIAGENTM, Venlo, The Netherlands), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of extracted DNA, which was of satisfactory quality in all samples, was determined using the 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and etidium bromide staining. The final DNA concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm using the NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) (30).

A total of four SNPs in genes encoding enzymes with antioxidative properties: SOD2 (rs4880), CAT (rs1001179), GPX1 (rs1050450), and NQO1 (rs689452) were genotyped using the pre-developed Taqman™ assays and the TaqPath™ ProAmp™ Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) on an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR Instrument System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, USA, according to manufacturer's instructions. In each experiment, positive controls encompassing all conceivable genotypes and "no template" controls were run

Selection of SNPs

Glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) polymorphism (rs1050450) results in the occurrence of nucleotides C/T at the position 599 ((Reference GPX1 transcript variant 1 Primary Assembly NM_000581.4: C599>T599), resulting in the replacement of proline with leucine (CCC>CTC; Pro200Leu). It is proposed that enzymes with leucine in their protein structure have decreased enzymatic activity (31).

Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) polymorphism (rs4880) results in the occurrence of nucleotides T/C at position 47 (Reference SOD2 transcript variant 1 Primary Assembly NM_000636.4: T47>C47), resulting in the replacement of valine with alanine (GTT>GCT; Val16Ala). It is proposed that valine decreases enzyme activity and leads to increased oxidative stress (32).

Catalase (CAT) polymorphism (rs1001179) results in the occurrence of nucleotides C/T at position 1317 (Reference GRCh38.p14 Primary Assembly NM_001752.4: C1317>T1317), which is -250 bp upstream from the start codon.

NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) polymorphism (rs689452) results in the occurrence of nucleotides C/G at the position 69718561 (Reference GRCh38.p14 Primary AssemblyNC_000016.10g (69709401..69726560): C69718561>G69718561; IVS1- 27C>G), in the first NQO1 intron.

No studies have investigated the involvement of these SNPs with the occurrence of TMD and harmful oral behaviours. However, it is possible that the presence of these SNPs could impact the antioxidative stress response, which is possibly involved in the etiology of chronic pain disorders.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

In a case-control study with a 1:1 participants' ratio, a sample size of 150 patients (75 TMD patients and 75 healthy controls) is required for achieving a power of 80% with a statistical error of 5% (α = 0.05), for the dominant inheritance model. This calculation was based on the assumption of a 5% TMD prevalence rate, as determined by previous studies (33,34).

Chi-squared tests were used for assessing deviations from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Differences between the studied groups (TMDp vs. CTR) and (HFP vs. LFP) were tested using Mann–Whitney U test and square tests for psychological and psychosomatic characteristics and categorical variables, respectively.

Genotype frequencies distribution among the groups (TMDp and CTR; HFP and LFP) was compared using the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. The assessment was performed according to dominant and recessive genetic models. In both models, the minor allele represented the risk allele.

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to examine differences in psychological and psychosomatic characteristics with respect to specific genotype, for each selected SNP.

To assess the associations of genetic, psychological, and psychosomatic parameters with pain-related TMD and with OB frequency, Spearman's correlation coefficients were used.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used for revealing the factors associated with pain-related TMD. Finally, multiple linear regression models were developed to clarify the effects of various factors related to OB frequency and severity. In multiple linear regression models, predictors of oral behaviours frequency were analysed when controlling for demographic variables (age and sex) and the presence of pain-related TMD (myalgia/arthralgia or absence of TMD). The independent variables were: examined genotype, depression, anxiety, somatosensory amplification, and hypervigilance. Any variable found to be significantly associated with a dependent variable was entered into the linear regression model. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

1. Characteristics of participants

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics, and other study relevant characteristics of participants. The TMDp group consisted of 85 patients; 76 women. The control group included 85 participants; 62 women. Women were more represented in the TMPp compared to the CTR group (89.4% vs. 72.9%, p=0.006). No significant differences in other general characteristics between the two groups were found (age: p=0.064; educational level: p=0.676). Trait anxiety, depression, hypervigilance and somatosensory amplification did not differ between TMDp patients and healthy controls (p=0.427, p=0.329, p=0.362, p=0.998, respectively).

Table 2 presents the frequency of oral behaviours in TMDp patients and CTR group. Significantly higher values were found for sleep-related oral behaviours (5.21±2.23 vs. 4.34±1.76, p=0.007), while OBC-tot score and waking-state oral behaviours did not differ significantly between these two groups (29.05±10.75 vs. 25.92±7.26, p=0.161; 24.09 ±10.12 vs. 21.63±6.85, p=0.235, respectively).

Based on the OBC-tot score results, 57.6% (n=98) of the total number of participants were identified as having high-frequency parafunction (out of which 48 belonged to the TMDp and 50 to the CTR group). The rest of the participants, 72 of them, were identified as having low-frequency parafunction. When comparing HFP with LFP individuals (

Table 1), women were more represented in HFP group (86.7% vs. 73.6%, p=0.031), while no significant differences were found for age (p=0.077) and education level (p=0.804). HFP individuals presented significantly higher anxiety (5.05 ± 4.22 vs. 3.42 ± 2.77, p= 0.020) and depression scores (6.01 ± 4.68 vs. 3.90 ± 3.30, p= 0.001), as well as higher hypervigilance (4.59±3.48 vs. 3.47±2.89, p=0.046) and somatosensory amplification (15.79±5.85 vs. 12.19±5.03, p<0.001) when compared to LFP individuals.

2. Participants' genotype

Genotype distribution of four SNPs, with respect to the presence of pain (TMDp/CTR) and frequency of oral behaviours (HFP/LFP), are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4 for recessive and dominant models, respectively.

Analysis of the recessive model (

Table 3) revealed that there was no difference in the distribution of

rs1001179,

rs4880 and

rs1050450 genotypes when TMDp patients were compared with healthy controls (p=0.773, p=0.701, p=0.201, respectively). When assessing the effect of oral behaviour frequency, a significant difference in genotype distribution for

rs1050450 (

GPX1) between HFP and LFP individuals was found; the frequency of

rs1050450 AA genotype was higher in HFP compared to LPI group (14.3% vs. 4.2%, p =0.030). The frequency of patients carrying minor allele T of

rs1001179, as well as the frequency of patients carrying minor allele G of

rs4880 was also slightly higher in HFP than in the LFP group, but the difference was not statistically significant.

There was no difference in the distribution of

rs1001179,

rs4880,

rs1050450 and

rs689452 genotypes between TMDp and CTR, nor between HFP and LFP individuals, when the dominant model was analysed (

Table 4).

3. Psychological and psychosomatic traits with respect to a specific genotype

Data regarding differences in psychological, psychosomatic and behavioural characteristics for the

CAT, SOD2, GPX1 and

NQO1 genes according to the respective genotype group are available on request. Only characteristics that were significantly related to a specific genotype are presented in

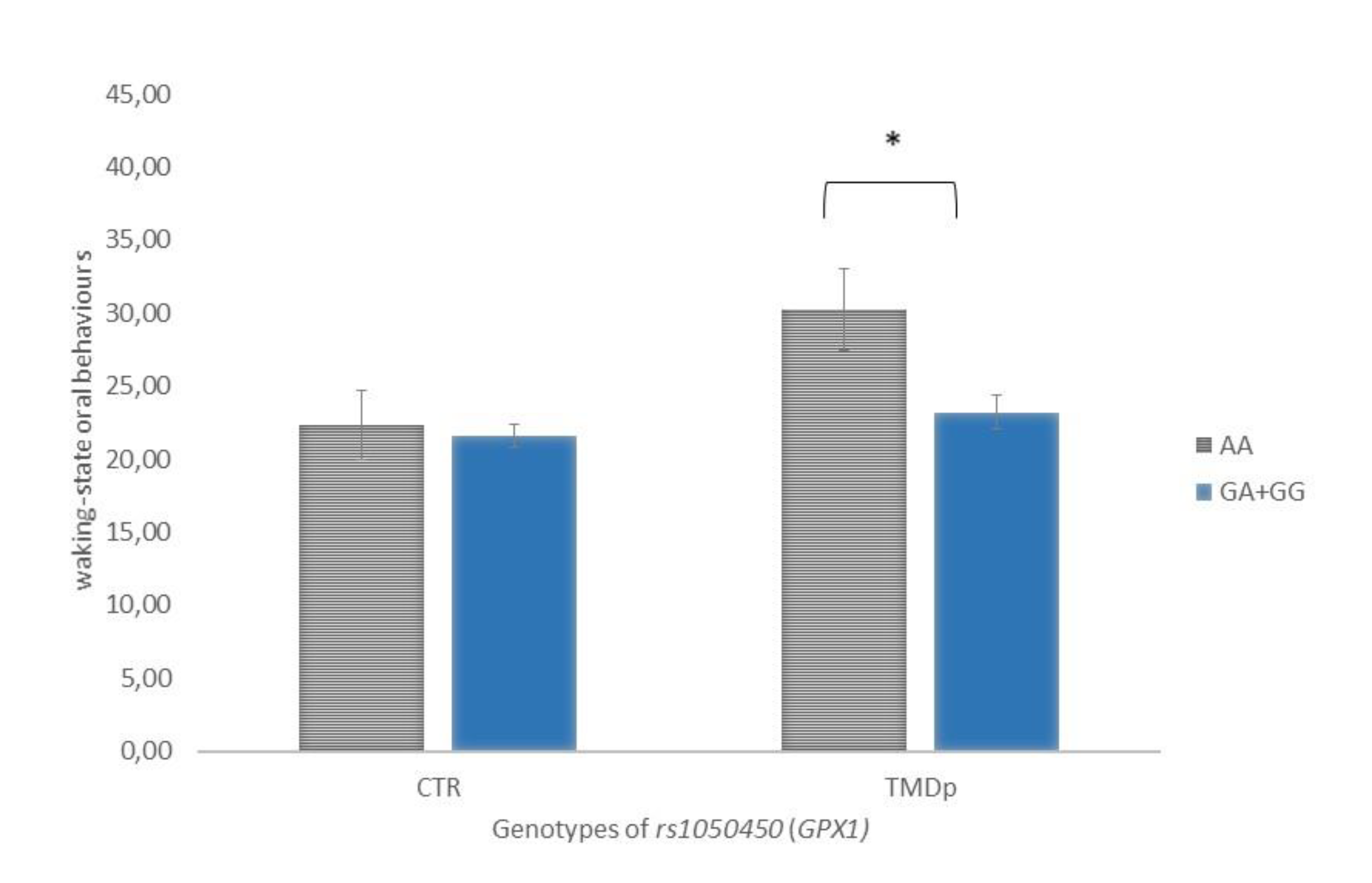

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

3.1. Analysis with respect to the presence of pain (TMDp/CTR)

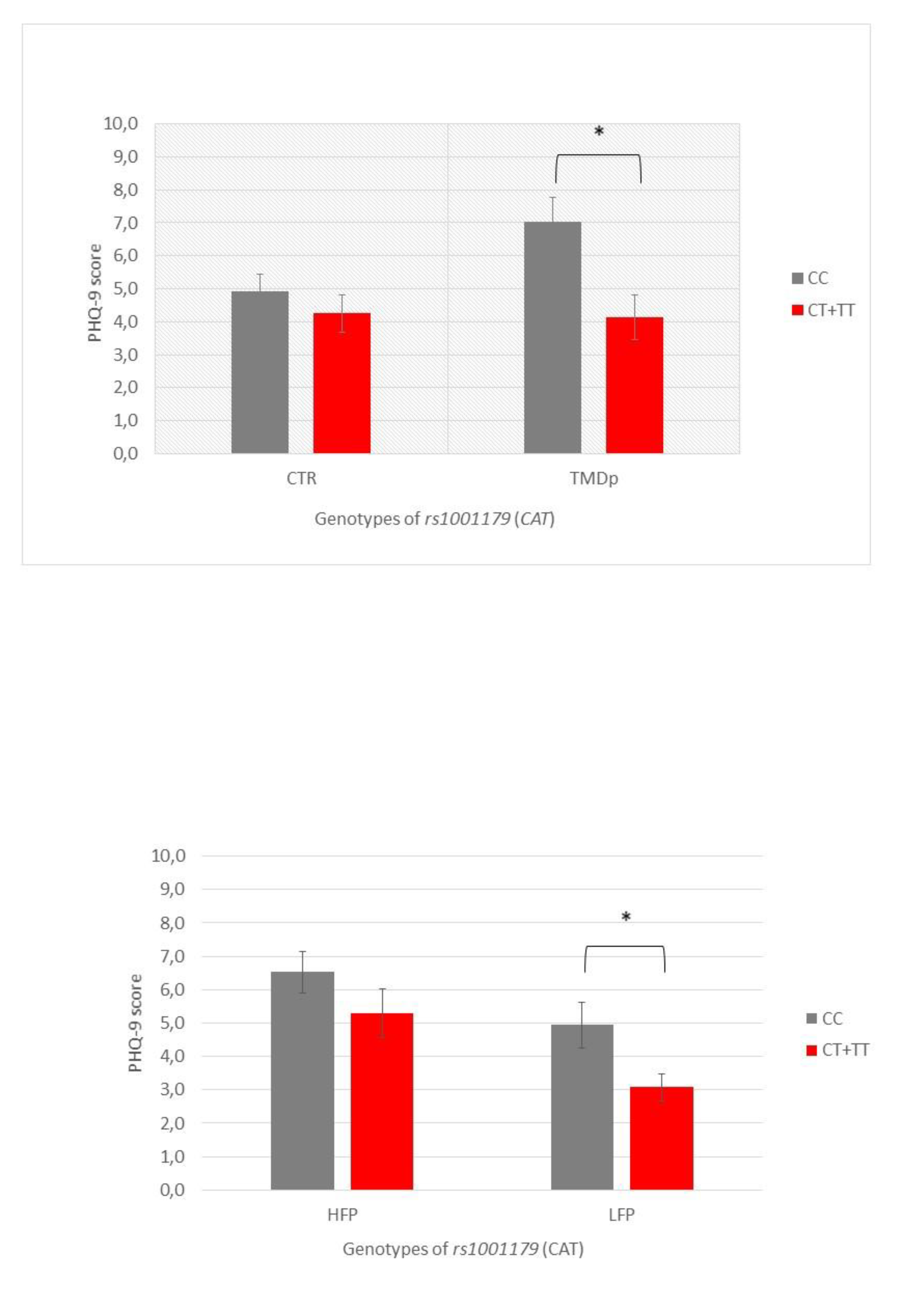

Analysis of examined psychological and psychosomatic characteristics according to genotype revealed that TMD patients, CC

CAT (

rs1001179), reported significantly higher depression scores compared to the CT+TT genotype carriers (PHQ-9: 7.1 vs. 4.2, p=0.002). In the control group, examined characteristics were not related by a specific genotype (

Figure 1A).

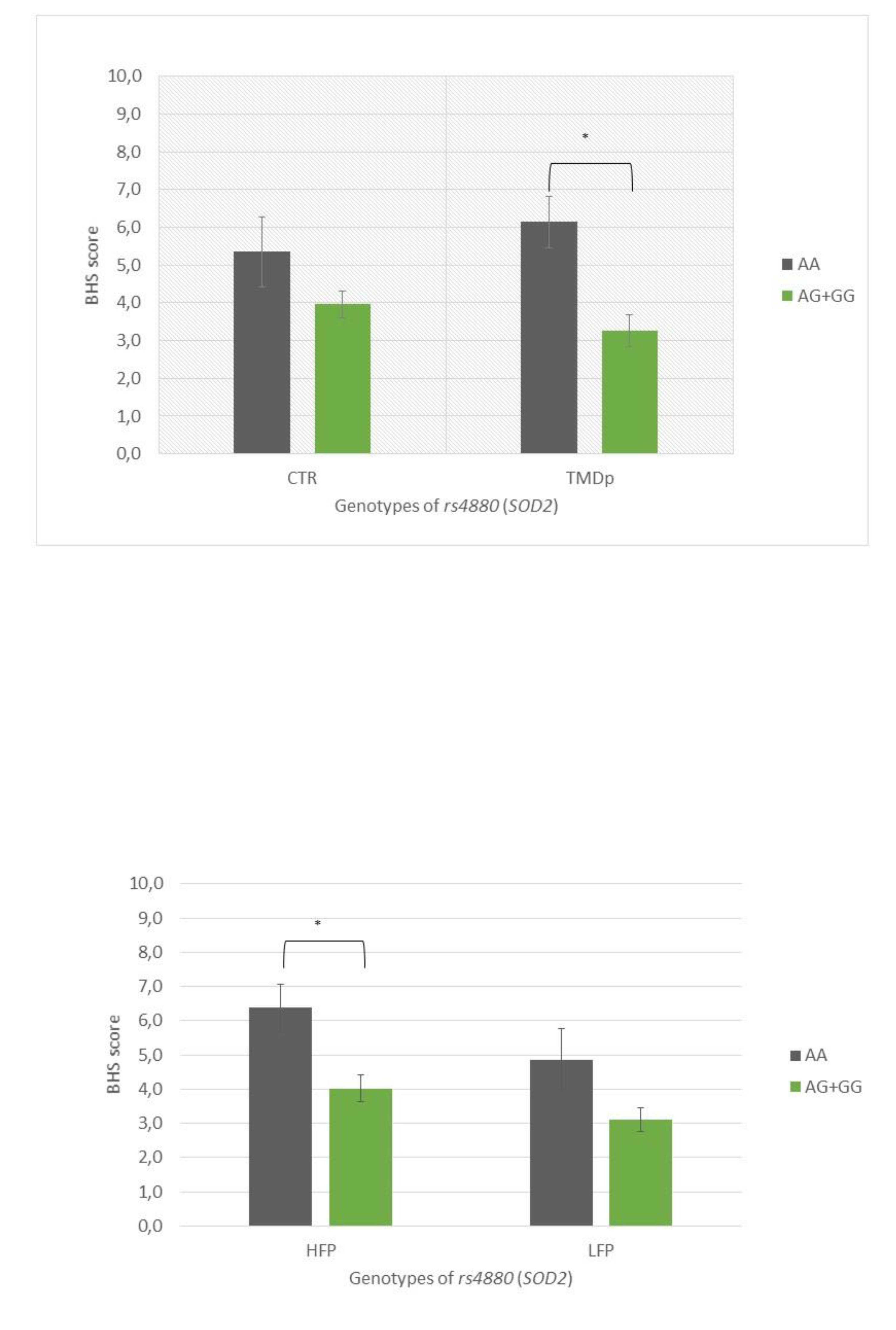

TMD patients, AA

SOD2 (

rs4880) homozygotes, reported significantly higher hypervigilance scores compared to TMD patients carrying the AG+GG genotypes (BHS: 6.14 vs. 3.25, p=0.0001) (

Figure 2A).

When behavioural characteristics were analysed according to the genotype, it was found that TMDp patients, homozygous for minor allele A of the

rs1050450 GPX1, reported significantly more waking-state OB compared to the GA+GG genotype carriers (score: 30 vs. 23, p=0.019). In the control group, waking-state OB were not associated with examined genotype (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Waking-state oral behaviours scores of participants with different genotypes of rs1050450 (GPX1) in TMDp patients and CTR group. Data are expressed as mean ±SME. *represents p<0.05. Abbreviations: CTR, control group—absence of TMD; TMDp, TMD-pain patients—presence of pain disorders including myalgia, arthralgia or both.

Figure 3.

Waking-state oral behaviours scores of participants with different genotypes of rs1050450 (GPX1) in TMDp patients and CTR group. Data are expressed as mean ±SME. *represents p<0.05. Abbreviations: CTR, control group—absence of TMD; TMDp, TMD-pain patients—presence of pain disorders including myalgia, arthralgia or both.

3.2. Analysis with respect to oral behavior frequency (HFP/LFP)

LFP subjects carrying the CC genotype of

CAT rs1001179 polymorphism reported significantly higher depression scores compared to CT+TT genotype carriers (PHQ-9: 4.9 vs. 3.0, p=0.021) (

Figure 1B). HFP subjects with the AA genotype of the

SOD2 SNP

rs4880 reported significantly higher hypervigilance scores compared to AG+GG genotype carriers (BHS: 6.4 vs. 4.0, p=0.003) (

Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

(AB). Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores of participants with different genotypes of rs1001179 (CAT), according to the presence of pain (A) and OB frequency (B). Data are expressed as mean ±SME. *represents p<0.05. Abbreviations: CTR, control group—absence of TMD; TMDp, TMD-pain patients—presence of pain disorders including myalgia, arthralgia or both; HFP, high-frequency parafunction group; LFP, low-frequency parafunction group; Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9.

Figure 1.

(AB). Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores of participants with different genotypes of rs1001179 (CAT), according to the presence of pain (A) and OB frequency (B). Data are expressed as mean ±SME. *represents p<0.05. Abbreviations: CTR, control group—absence of TMD; TMDp, TMD-pain patients—presence of pain disorders including myalgia, arthralgia or both; HFP, high-frequency parafunction group; LFP, low-frequency parafunction group; Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9.

Figure 2.

(AB). Brief Hypervigilance Scale (BHS) scores of participants with different genotypes of rs4880 (SOD2), according to the presence of pain (A) and OB frequency (B). Data are expressed as mean ±SME. *represents p<0.05. Abbreviations: CTR, control group—absence of TMD; TMDp, TMD-pain patients—presence of pain disorders including myalgia, arthralgia or both; HFP, high-frequency parafunction group; LFP, low-frequency parafunction group; BHS, Brief Hypervigilance Scale.

Figure 2.

(AB). Brief Hypervigilance Scale (BHS) scores of participants with different genotypes of rs4880 (SOD2), according to the presence of pain (A) and OB frequency (B). Data are expressed as mean ±SME. *represents p<0.05. Abbreviations: CTR, control group—absence of TMD; TMDp, TMD-pain patients—presence of pain disorders including myalgia, arthralgia or both; HFP, high-frequency parafunction group; LFP, low-frequency parafunction group; BHS, Brief Hypervigilance Scale.

4. Risk factors associated with pain-related TMD

A multivariable logistic regression model was used to find the factors associated with pain-related TMD. Age, sex, and sleep-related OB were included as potential confounders or effect modifiers. According to logistic regression, the probability of TMDp was significantly associated with a higher frequency of sleep-related oral behaviours (OR 1.198, 95% CI 1.020-1.406, p=0.028), female sex (OR 3.190, 95% CI 1.329-7.654, p=0.009) and increasing age (OR 1.041, 95% CI 1.005-1.078, p=0.025) (

Table 5). The explanatory quality (Nagelkerke R2) of this model was 0.147.

5. Risk factors associated with oral behavior frequency

5.1. Risk factors associated with waking-state oral behaviours

AA genotype of the

rs1050450 (GPX1), depression, anxiety, somatosensory amplification, hypervigilance, and sex were shown to have a significant association with waking-state oral behaviours. Due to the strong correlation between depression, anxiety, somatosensory amplification, and hypervigilance, these variables were entered into the model independently (

Table 6).

Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that, after adjustment for age, a significant predictor for waking-state oral behaviours was depression followed by female sex and AA genotype of rs1050450. The whole regression model accounted for 18.1% of the variance (R2=0.181).

When substituted for depression, an increase in anxiety by one scalar point increased waking-state oral behaviours score by 0.721 scalar points, while female sex and GPX1 polymorphism remained significant. The whole regression model accounted for 15.0% of the variance (R2 = 0.150).

One-point increment in the somatosensory amplification score was associated with 0.604 points increments in the waking-state oral behaviours score, while an increase in hypervigilance by one scalar point increased the waking-state oral behaviours score by 0.619 scalar points. However, the GPX1 polymorphism, rs1050450, did not remain significant in these models.

5.2. Risk factors associated with sleep-related oral behaviours

Age, pain-related TMD, depression, anxiety, and somatosensory amplification were shown to have a significant association with sleep-related oral behaviours. Multiple linear regression analysis (

Table 7) revealed that, after adjustment for sex, a significant predictor for sleep-related OB was depression. Furthermore, the presence of TMDp increased the sleep-related oral behaviours scores by 0.636 scalar points. The whole regression model accounted for 7.4 % of the variance (R2 = 0.074).

Due to the high correlation with depression, anxiety (r=0.676; p<0.001) and somatosensory amplification (r=0.354; p<0.001) were first omitted from the analysis. When substituted for depression, both anxiety and somatosensory amplification showed a significant effect on sleep-related oral behaviours scores.

Discussion

The present study examined the relationship between pain-related TMD, oral behaviours, psychological and psychosomatic symptoms, and selected SNPs in four genes coding for proteins with antioxidative properties.

To begin, it is important to offer a brief review of the general TMD-related characteristics of the participants. The participants with a high frequency of oral parafunction, regardless of pain status, had significantly higher scores of somatosensory amplification, anxiety, depression, and hypervigilance. These results might suggest that individuals who engage in more frequent oral parafunction may be at a higher risk of developing these psychological symptoms or those with psychological symptoms may be at higher risk of developing a high frequency of oral parafunction.

Interestingly, no significant differences were observed in the levels of somatosensory amplification, anxiety, depression, or hypervigilance between TMDp patients and healthy controls. This implies that psychological symptoms may be more closely related to parafunctional behaviours than TMD.

The study found that TMDp patients had a higher frequency of sleep-related oral behaviours compared to the healthy controls. Although there was a difference in waking-state oral behaviours between TMDp patients and healthy controls, this difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, the frequency of oral parafunction differed significantly between genders, with more women engaging in a high-frequency parafunction and more men engaging in a low-frequency parafunction. These findings indicate that oral parafunctional behaviours may be linked to psychological symptoms, and it is possible that a gender difference needs to be considered when evaluating and treating individuals with these behaviours. However, it's important to keep in mind the overall disparity in the frequency of women versus men in the study, as there were more women included. Also, this association remains controversial in the literature with some studies reporting differences in parafunctional activities between men and women, while others report no such differences (35-37). Additionally, the findings suggest that sleep-related oral behaviours may be particularly relevant in TMD patients.

Regarding the genotype distribution of polymorphisms in the four oxidative stress-related genes, no differences were found between TMDp patients and healthy controls neither in recessive, nor in dominant models. This could mean that, without considering additional risk factors, inherited variations of selected SNPs wouldn't be recognized as a potential risk factor related to TMD. However, when psychological, and psychosomatic characteristics and oral behaviours were evaluated, examined characteristics were influenced by genotype only in TMDp group. To specify, in patients with pain-related TMD genotype AA of SOD2 polymorphism rs4880 was associated with higher hypervigilance scores, and genotype CC of CAT SNP rs1001179 was associated with higher depression scores. In our earlier work, we discovered a link between psychological characteristics in TMD patients and antioxidant status, where depression and anxiety were both negatively correlated with antioxidant levels. Furthermore, the improvement of depressive symptoms during therapy was associated with a decrease in total antioxidant capacity (38). Such results might be, among other reasons, a reflection of genetic variations found among TMD patients. Both mentioned genotypes contain two copies of the major allele, even though a minor allele was expected to be a risk factor in this study. Some research reported that allele A of rs1001179 (CAT) was associated with a 0.6-fold decrease in risk for acoustic neuroma (39). Galasso et al. revealed the importance of the CAT rs1001179 polymorphism with respect to CAT gene activity. In their model of investigation, leukemic cells harboring the rs1001179 SNP T allele exhibited a significantly higher CAT expression when compared with cells bearing the CC genotype, due to increased binding of two transcription factors, ETS proto-oncogene 1 (ETS-1) and glucocorticoid receptor beta (GR-β). The strength of binding and transcriptional activity of CAT was also dependent on the level of DNA methylation (40). This data implies that even though minor alleles are more likely to be risk alleles in complex diseases that may not always be the case (41).

Since migraine is a chronic pain disorder sometimes found as a comorbid condition to TMD it is interesting to see whether there is a potential genetic overlap. Papasavva et al. investigated how variabilities in SNPs, among which rs4880, rs1001179, and rs1050450 related to the susceptibility to migraine clinical phenotypes and features. What they found is that homozygosity for the minor T allele (rs1001179) was associated with the later age at the onset when compared to homozygosity for the more common allele C (42). It would be interesting to further investigate the connection between TMD and migraine onset and depression. Considering SOD2, no significant association was found for rs4880 variants for clinical features of migraine (42). One case-control study reported that there was a lack of association between oxidative stress-related genes SNPs (among which was rs4880 of SOD2) and chronic migraine (43).

Our findings revealed that polymorphisms in oxidative stress-related genes were not predictive for pain-related TMD. The recessive homozygous genotype of the GPX1 polymorphism rs1050450, together with greater anxiety and depression scores and female gender, was revealed to be a significant predictor of more frequent waking-state oral behaviours. Sleep-related oral behaviours were not predicted by any of examined gene polymorphisms. The latter was predicted by increased age, greater anxiety, depression, and somatization scores. These findings suggest that oxidative stress-related genes may play a role in waking-state oral behaviours, while sleep-related parafunctional activity, as well as pain-related TMD, are more likely a consequence of complex interplay of various biological and psychosocial factors.

The enzyme glutathione peroxidase 1 is a major endogenous antioxidant. Gene GPX1 encodes for this enzyme. Its polymorphism, rs1050450, contains nucleotides C/T in exon 2, resulting in an amino acid substitution of proline to leucine (44-45). In our research, anticodon-biding assay was used which means that the “AA” genotype can be interpreted as “TT” and “GG” as “CC”. With that in mind, we can comment on the scientific and clinical context of our results. Rs1050450 is associated with altered enzyme activity and may potentially influence a person's antioxidant capacity. Mainly, the minor T allele has been associated with decreased GPX1 activity (46). This polymorphism has been studied in relation to various conditions, such as peripheral neuropathy, cardiovascular disease, and migraine (42,47-48). TT homozygosity was connected to patients with longer attack duration compared to patients with shorter attack duration, indicating that the presence of the variant T allele seems to be related to prolonged migraine attacks (42). Our study found that individuals carrying genotype TT of rs1050450 are at a higher risk for experiencing high-frequency waking-state parafunction. Parafunction during wakefulness is more closely linked to various manifestations of stress, which might also be reflected through the variability in the antioxidant defense enzyme activities (49).

The study has several limitations that need to be taken into account when interpreting the data. One of these limitations is potential bias arising from the fact that in CTR and TMDp group participants were not sex-matched. This problem was addressed by applying additional analyses to determine if odds ratios would remain significant when accounting for relevant risk variables and covariates such as sex. Since there could be sex-related differences in pain physiology and clinical outcomes, these additional analyses were critical. Also, our control group represents the general population, in contrast to TMD-prone patients who are predominantly women. Even though our sample size was respectable and adequate according to power analysis, studies with larger sample sizes would yield more valuable insights and produce more conclusive results. Lastly, it is important to consider the possibility of participants not providing truthful responses in self-reported questionnaires, especially on sensitive questions, despite the fact that most of the questionnaires used in the study were validated and are the part of the recommended DC/TMD protocol for research studies. All participants filled out questionnaires in the same clinical setting with a certain level of privacy.

Overall, these findings highlight the need for a comprehensive approach to diagnosing and treating TMD. While genetic factors may play a role to some extent, it is still important to consider a range of other factors such as age, sex, and psychological characteristics when assessing and managing TMD and associated sleep-related oral behaviours. The interindividual variability in the distribution of oxidative stress-related genes' polymorphisms may not have a direct association with the development of pain-related TMD. However, they may play an impotant role in the complex interaction between TMD, behavioural habits, and psychological characteristics of a patient.

The role of the SNPs studied remains largely unexplored in the field of chronic pain and TMD,and further studies on this topic are needed.

Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, it can be concluded that TMDp cannot be directly linked to described polymorphisms in four selected oxidative stress-related genes. However, TMDp patients, homozygous for minor allele A of the rs1050450 GPX1 reported significantly more waking-state oral behaviours compared to the GA+GG genotype carriers. This finding was not observed in healthy participants.

We found that the homozygous AA carriers of the rs1050450 SNP were more often represented in the HFP in comparison with the LFP group of participants. This genotype proved to be a significant risk factor for increased frequency of waking-state oral behaviours, while sleep-related oral behaviours were not shown to be associated with the investigated genetic factors.

The association of waking-state oral behaviours with the oxidative stress-related genes' polymorphisms additionally supports previous observations, that daytime bruxism is more closely linked to various manifestations of stress, which might also be reflected through the variability in the antioxidant defence enzyme activities.

Gene IDs

The genes that were used in this study all had NCBI gene IDs: GPX1 (rs1050450)- 2876; SOD2 (rs4880) - 6648; CAT (rs1001179) - 847; NQO1 (rs689452) - 1728.

Authors Contributions

E.V. conducted participants’ examinations, assisted in the gathering of DNA samples, carried out DNA extraction, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. She also assisted with the study's design and conceptualisation. M.Z. carried out the research (participant examinations, DNA sample collection, DNA extraction, and qPCR analysis) and wrote the paper. K.G.T. provided guidance in the conceptualization and design of the research. She also edited and thoroughly revised the manuscript. M.T. assisted with the DNA extraction procedure and qPCR analysis. In addition to actively collaborating in experimental part of the research. K.V.Đ. assisted with the qPCR analysis and DNA extraction procedure, and she revised the manuscript. I.Z.A. conceptualised, designed, and carried out the research. She analysed and interpreted the data, wrote and critically edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work has been entirely supported by the Croatian Science Foundation Project ‘Genetic polymorphisms and their association with temporomandibular disorders’ (No. IP-2019-04-6211) and ‘Young Researchers’ Career Development Project – Training of Doctoral Students’. Details are available at

https://genpoltmd.wixsite.com/hrzz. The authors thank Prof. Sanja Kapitanović, MD, Ph.D., the Laboratory for Personalised Medicine, Division of Molecular Medicine at the Ruđer Bošković Institute, for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maixner, W.; Diatchenko, L.; Dubner, R.; Fillingim, R.B.; Greenspan, J.D.; Knott, C.; Ohrbach, R.; Weir, B.; Slade, G.D. Orofacial pain prospective evaluation and risk assessment study--the OPPERA study. J Pain. 2011, 12, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, G.D.; Bair, E.; Greenspan, J.D.; Dubner, R.; Fillingim, R.B.; Diatchenko, L.; Maixner, W.; Knott, C.; Ohrbach, R. Signs and symptoms of first onset TMD and sociodemographic predictors of its development: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. J Pain. 2013, 14, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isong, U.; Gansky, S.A.; Plesh, O. Temporomandibular joint and muscle disorder-type pain in U.S. adults: the National Health Interview Survey. J Orofac Pain. 2008, 22, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.P.; List, T.; Svensson, P.; Gonzalez, Y.; Lobbezoo, F.; Michelotti, A.; Brooks, SL.; Ceusters, W.; Drangsholt, M.; Ettlin, D.; Gaul, C.; Goldberg, L.J.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Hollender, L.; Jensen, R.; John, M.T.; De Laat, A.; de Leeuw, R.; Maixner, W.; van der Meulen, M.; Murray, G.M.; Nixdorf, D.R.; Palla, S.; Petersson, A.; Pionchon, P.; Smith, B.; Visscher, C.M.; Zakrzewska, J.; Dworkin, S.F. International RDC/TMD Consortium Network, International association for Dental Research; Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of Pain. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group†. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014, 28, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glaros, A.G.; Williams, K.; Lausten, L. ; The role of parafunctions, emotions and stress in predicting facial pain. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005, 136, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Ahlberg, J.; Lobbezoo, F. Bruxism definition: Past, present, and future - What should a prosthodontist know? J Prosthet Dent. 2022, 128, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, M.I.; Yanık, S.; Keskinruzgar, A.; Taysi, S.; Copoglu, S. : Orkmez, M.; Nalcaci R. Oxidative imbalance and anxiety in patients with sleep bruxism. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012, 114, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohrbach, R.; Michelotti, A. The Role of Stress in the Etiology of Oral Parafunction and Myofascial Pain. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2018, 30, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braz, M.A.; Freitas Portella, F.; Seehaber, K.A.; Bavaresco, C.S.; Rivaldo, E.G. Association between oxidative stress and temporomandibular joint dysfunction: A narrative review. J Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radak, Z.; Lee, K.; Choi, W.; Sunoo, S.; Kizaki, T.; Oh-Ishi, S.; Sizuki, K.; Taniguchi, N.; Ohno. H.; Asano, K. Oxidative stress induced by intermittent exposure at a simulated altitude of 4000 m decreases mitochondrial superoxide dismutase content in soleus muscle of rats. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1994, 69, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masahiro, I.; Shinya, A.; Nagata, S.; Miyata, M.; Hiroshi, K. Relationships between perceived workload, stress and oxidative DNA damage. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2001, 74, 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, A.; Fassett, R.G.; Geraghty, D.P.; Kunde, D.A.; Ball, M.J.; Robertson, I.K.; Coombes, J.S. Relationships between single nucleotide polymorphisms of antioxidant enzymes and disease. Gene. 2012, 501, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assavarittirong, C.; Samborski, W.; Grygiel-Górniak, B. Oxidative Stress in Fibromyalgia: From Pathology to Treatment. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022, 1582432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyik, S.; Altunısık, E.; Neyal, A.M.; Taysi, S. Oxidative stress and DNA damage in patients with migraine. J Headache Pain. 2016, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, C.; Amenábar, J.M. Changes in the salivary oxidative status in individuals with temporomandibular disorders and pain. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2016, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez de Sotillo, D.; Velly, A.M.; Hadley, M.; Fricton, J.R. Evidence of oxidative stress in temporomandibular disorders: a pilot study. J Oral Rehabil. 2011, 38, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, HX.; Luo, J.M.; Long, X.; Li, X.D.; Cheng, Y. Free-radical oxidation and superoxide dismutase activity in synovial fluid of patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2006, 20, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vrbanović, E.; Alajbeg, I.Z.; Vuletić, L.; Lapić, I.; Rogić, D.; Andabak Rogulj, A.; Illeš, D.; Knezović Zlatarić, D.; Badel, T.; Alajbeg, I. Salivary Oxidant/Antioxidant Status in Chronic Temporomandibular Disorders Is Dependent on Source and Intensity of Pain - A Pilot Study. Front Physiol. 2018, 9, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouayed, J.; Rammal, H.; Soulimani, R. Oxidative stress and anxiety: relationship and cellular pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009, 2, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, A.; Robles-Fernandez, I.; Martinez-Gonzalez, L.J.; Carmona, R.; Alvarez-Cubero, M.J. Influence of Oxidative Stress-Related Genes on Susceptibility to Fibromyalgia. Nurs Res. 2021, 70, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourvali, K.; Abbasi, M.; Mottaghi, A. Role of Superoxide Dismutase 2 Gene Ala16Val Polymorphism and Total Antioxidant Capacity in Diabetes and its Complications. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2016, 8, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Djokic, M.; Radic, T.; Santric, V.; Dragicevic, D.; Suvakov, S.; Mihailovic, S.; Stankovic, V.; Cekerevac, M.; Simic, T.; Nikitovic, M.; Coric, V. The Association of Polymorphisms in Genes Encoding Antioxidant Enzymes GPX1 (rs1050450), SOD2 (rs4880) and Transcriptional Factor Nrf2 (rs6721961) with the Risk and Development of Prostate Cancer. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022, 58, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- editor. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders: Assessment Instruments. Version 15May2016. [Dijagnostički kriteriji za temporomandibularne poremećaje (DK/TMP) Instrumenti procjene: Croatian Version 23March2021] Spalj S, Katic V, Alajbeg I, Celebic A. Trans. www.rdc-tmdinternational.org Accessed on.

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsky, A.J.; Goodson, J.D.; Lane, R.S.; Cleary, P.D. The amplification of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 1988, 50, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, R.E.; Delker, B.C.; Knight, J.A.; Freyd, J.J. Hypervigilance in college students: Associations with betrayal and dissociation and psychometric properties in a Brief Hypervigilance Scale. Psychol Trauma. 2015, 7, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbanović, E.; Zlendić, M.; Alajbeg, I.Z. Association of oral behaviours' frequency with psychological profile, somatosensory amplification, presence of pain and self-reported pain intensity. Acta Odontol Scand. 2022, 80, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlendić, M.; Vrbanović, E.; Tomljanović, M.; Gall Trošelj, K.; Đerfi, K.V.; Alajbeg, I.Z. Association of oral behaviours and psychological factors with selected genotypes in pain-related TMD. Oral Dis. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ravn-Haren, G.; Olsen, A.; Tjønneland, A.; Dragsted, L.O.; Nexø, B.A.; Wallin, H.; Overvad, K.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Vogel, U. Associations between GPX1 Pro198Leu polymorphism, erythrocyte GPX activity, alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in a prospective cohort study. Carcinogenesis. 2006, 27, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.; Imbert, A.; Igoudjil, A.; Descatoire, V.; Cazanave, S.; Pessayre, D.; Degoul, F. The manganese superoxide dismutase Ala16Val dimorphism modulates both mitochondrial import and mRNA stability. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005, 15, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, E.P.; Park, J.W. Sample size and statistical power calculation in genetic association studies. Genomics Inform. 2012, 10, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, G.D.; Bair, E.; Greenspan, J.D.; Dubner, R.; Fillingim, R.B.; Diatchenko, L.; Maixner, W.; Knott, C.; Ohrbach, R. Signs and symptoms of first-onset TMD and sociodemographic predictors of its development: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. J Pain. 2013, 14, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieckiewicz, M.; Grychowska, N.; Wojciechowski, K.; Pelc, A.; Augustyniak, M.; Sleboda, A.; Zietek, M. Prevalence and correlation between TMD based on RDC/TMD diagnoses, oral parafunctions and psychoemotional stress in Polish university students. Biomed Res Int. 2014;472346.

- Mirhashemi, A.; Khami, M.R.; Kharazifard, M.; Bahrami, R. The Evaluation of the Relationship Between Oral Habits Prevalence and COVID-19 Pandemic in Adults and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Front Public Health. 2022, 10, 860185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winocur-Arias, O.; Winocur, E.; Shalev-Antsel, T.; Reiter, S.; Levartovsky, S.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Friedman-Rubin, P. Painful Temporomandibular Disorders, Bruxism and Oral Parafunctions before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic Era: A Sex Comparison among Dental Patients. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajbeg, I.Z.; Vrbanović, E.; Lapić, I.; Alajbeg, I.; Vuletić, L. Effect of occlusal splint on oxidative stress markers and psychological aspects of chronic temporomandibular pain: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 10981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, P.; Hutchinson, A.; Rothman, N.; Black, P.M.; Fine, H.A.; Loeffler, J.S.; Selker, R.G.; Shapiro, W.R.; Linet, M.S.; Inskip, P.D. Oxidative response gene polymorphisms and risk of adult brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2008, 10, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, M.; Dalla Pozza, E.; Chignola, R.; Gambino, S.; Cavallini, C.; Quaglia, F.M.; Lovato, O.; Dando, I.; Malpeli, G.; Krampera, M.; Donadelli, M.; Romanelli, M.G.; Scupoli, M.T. The rs1001179 SNP and CpG methylation regulate catalase expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022, 79, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kido, T.; Sikora-Wohlfeld, W.; Kawashima, M.; Kikuchi, S.; Kamatani, N.; Patwardhan, A.; Chen, R.; Sirota, M.; Kodama, K.; Hadley, D.; Butte, A.J. Are minor alleles more likely to be risk alleles? BMC Med Genomics. 2018, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papasavva, M.; Vikelis, M.; Siokas, V.; Katsarou, M.S.; Dermitzakis, E.V.; Raptis, A.; Kalliantasi, A.; Dardiotis, E.; Drakoulis, N. Variability in oxidative stress-related genes (SOD2, CAT, GPX1, GSTP1, NOS3, NFE2L2, and UCP2) and susceptibility to migraine clinical phenotypes and features. Front. Neurol. 2023, 13, 1054333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, G.; Negro, A.; D'Alonzo, L.; Aimati, L.; Simmaco, M.; Martelletti, P.; Borro, M. Lack of association between oxidative stress-related gene polymorphisms and chronic migraine in an Italian population. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015, 15, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Rocha, T.J.; Silva Alves, M.; Guisso, C.C.; de Andrade, F.M.; Camozzato, A.; de Oliveira, A.A.; Fiegenbaum, M. Association of GPX1 and GPX4 polymorphisms with episodic memory and Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2018, 666, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teimoori, B.; Moradi-Shahrebabak, M.; Razavi, M.; Rezaei, M.; Harati-Sadegh, M.; Salimi, S. The effect of GPx-1 rs1050450 and MnSOD rs4880 polymorphisms on PE susceptibility: A case- control study. Mol Biol Rep. 2019, 46, 6099–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuso, P.; García-Martín, E.; Agúndez, J.A.G. Variability of the genes involved in the cellular redox status and their implication in drug hypersensitivity reactions. Antioxidants. 2021, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.S.; Prior, S.L.; Li, K.W.; Ireland, H.A.; Bain, S.C.; Hurel, S.J.; Cooper, J.A.; Humphries, S.E.; Stephens, J.W. Association between the rs1050450 glutathione peroxidase-1 (C > T) gene variant and peripheral neuropathy in two independent samples of subjects with diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012, 22, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charniot, J.C.; Sutton, A.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Cosson, C.; Khani-Bittar, R.; Giral, P.; Charnaux, N.; Albertini, J.P. Manganese superoxide dismutase dimorphism relationship with severity and prognosis in cardiogenic shock due to dilated cardiomyopathy. Free Radic Res. 2011, 45, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, S.N.; Nickel, J.C.; Iwasaki, L.R.; Crow, H.C.; Gonzalez, Y. Association between waking-state oral parafunctional behaviours and bio-psychosocial characteristics. J Oral Rehabil. 2015, 42, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).