Preprint

Article

A Combinatorial TIR1-Aux/IAA Co-Receptor System for Peach Fruit Softening

Altmetrics

Downloads

102

Views

18

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

supplementary.docx (624.28KB )

† These authors contributed too the manuscript equally.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

16 May 2023

Posted:

18 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Fruit softening is an important characteristic of peach fruit ripening. The auxin receptor TIR1 (Transport Inhibitor Response 1) plays an important role in plant growth and fruit maturation, but little research has been conducted on the relation of TIR1 to the softening of peach fruits. In this study, the hardness of isolated peach fruits was reduced under exogenous NAA treatment of low concentration, at the same time, the low concentration of NAA treatment reduced the transcription level of PpPG and Ppβ-GAL genes related to cell wall softening, and PpACS1 genes related to ethylene synthesis. The transient over-expression of the PpTIR1 gene in peach fruit blocks caused significant down-regulation of the expression of early auxin-responsive genes, ethylene synthesis and cell wall metabolic genes related to fruit firmness. Through yeast two-hybrid technology, bimolecular fluorescence complementary technology, and firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay, an interaction between PpTIR1 and PpIAA1/3/5/9/27 proteins was revealed, and the interaction depended on auxin and its type and concentration. These results show that PpTIR1-Aux/IAA module has a possible regulatory effect on fruit ripening and softening.

Keywords:

Subject: Biology and Life Sciences - Horticulture

1. Introduction

Auxin was the earliest plant hormone discovered, and it plays a notable role in the regulation of fruit ripening recently. The application of exogenous auxin during the early ripening stage of strawberry, grape and tomato fruit can inhibit the ripening process [1,2,3]. However, the application of auxin to treat apples, pears and plums before fruit ripening can induce ethylene synthesis, thus promoting fruit softening and ripening [4,5,6]. Peach is a typical climacteric fruit. At present, studies have shown that the softening after peach fruit maturation is related to ethylene synthesis regulated by endogenous auxin [7]. The abrupt change of ethylene at the mature stage of peach fruit was regulated by IAA (indole-3-acetic acid) [8]. Other studies have shown that the inhibition of IAA synthesis during ripening of hard peach leads to the decrease of ethylene synthesis, which makes the fruit no softening [9,10]. At the same time, studies have shown that there is ethylene-independent auxin regulation pathway in peach fruit ripening [11].

Auxin regulates diverse physiological and developmental processes through the perception and transduction of auxin signals. The canonical auxin signaling pathway consists of SCFTIR1/AFBs complex (SKP1, Cullin and auxin signaling F-box protein), transcriptional suppressor Aux/IAA (Auxin/Indole Acetic Acid) and transcription factor ARF (Auxin Response Factor) [12]. In tomato, the transgenic line with the overexpression of SlTIR1 gene manifests changes in leaf morphology and fruit setting compared with the wild type [13]. Other studies on cucumber have found that the auxin receptor gene may play an important role in plant height, leaf morphology and parthenocarpy [14]. Overexpression of plum PslTIR1 gene in tomato decreased the height of transgenic plants, altered fruit development and fruit softening by controlling genes related to cell wall decomposition [15]. TIR1-like auxin-receptors are involved in the regulation of plum fruit development [16].

Degradation of the Aux/IAA repressors is a critical event in auxin signaling. At present, 25 Aux / IAA genes have been identified in tomato, which are involved in the regulation of auxin-mediated multiple signaling pathways. Among them, SlIAA3 is an important factor in the cross-regulation of physiological responses by auxin and ethylene, which regulates tomato leaf morphogenesis, floral organ development, fruit setting and fruit development. SlIAA9 resulted in abnormal leaf shape and parthenocarpy of tomato [17,18]. SlIAA17 plays a role in regulating fruit quality, and it is found that the SlIAA17 silencing line has larger fruit and thicker pericarp [19].

The regulatory mechanisms of Aux / IAAs on peach fruit development and maturation have also attracted much attention. The transient overexpression of the PpIAA1(Ppa010303m)gene in peach fruit can promote the expression of PpPG1 and PpACS1 genes and result in earlier ripening and shorter postharvest storage, which indicates that PpIAA1 acts as a positive regulator to promote fruit ripening and softening. The overexpression of peach PpIAA19 (Ppa011935m) gene in tomato resulted in an increase in plant height and the number of lateral roots, as well as changes in parthenogenesis and fruit morphology [20].

Although many studies have documented the influence of auxin on fruit ripening, the auxin signaling genes have not investigated more. The whole genome analysis of Aux / IAA and ARF gene families in peach fruit was conducted in our previous study [21,22,23]. A total of 4 TIR1/AFBs were identified in peach fruit. The transcript of PpTIR1 (ppa003344m) responds to exogenous auxin and expression level differs in peach fruit with different melting characteristic [24]. PpIAAs were identified, and some Aux/IAAs related to peach fruit ripening were found [22]. In this current study, we treated peach fruits with NAA (1-naphthylacetic acid) and found low concentration treatment delayed the fruit softening and decreased the expression of cell wall-disassembling genes and ethylene biosynthetic genes. We also found over-expression of PpTIR1 gene caused significant down-regulation of the expression of early auxin-responsive genes and cell wall metabolic genes related to fruit firmness. A combinatorial TIR1-Aux/IAA co-receptor system may be involved in this process. Therefore, the regulation of auxin on peach fruit softening is concentration dependent. This study can enrich the theoretical study of drupe fruit ripening and lay a theoretical foundation for the hormone regulation measures of peach fruit softening.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

Experimental samples of the melting peach ‘Okubo’ were picked from the experimental orchard of Beijing University of Agriculture (Changping District, Beijing, China). The fruits at 37, 46, 55, 63, 70, 78, 84, 92, 98 and 110 days after full bloom (DAFB). We divided the development and maturation of peach fruit into four periods: the first rapid growth period (1 to 37 DAFB, S1), the hard core stage (37 to 63 DAFB, S2), the second rapid growth period (63 to 84 DAFB, S3), and mature period (after 84 DAFB, S4). The mature period was further divided into S4-1 (84 to 92 DAFB), S4-2 (92 to 98 DAFB), and S4-3 (after 98 DAFB).

Peach fruits 'Okubo' at the developmental stage of S4-1 were selected and treated with deionized water (H2O), 20 μM NAA and 100 μM NAA. After washing with water and drying naturally, the peach fruit was soaked in the above three solutions respectively. The solution was placed in a vacuum for 30 min, and the vacuum was slowly released to help the solution enter the peach fruit. After natural drying at room temperature, the treated peach fruits were stored under natural light for 14 days at 20±2℃. Samples were taken on the 1st, 7th and 14th day after treatment, and the firmness of fruits was measured.

2.2. Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from peach fruit using EASYspin reagent (Biomen, China). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed as described by Guan et al [22]. The first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using TransScript First-Stand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix kit (TransGen Biotech, China). The cDNA template for qRT-PCR analysis was diluted 10 times with RNase-free water before use. TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara, Japan) reagent was used to perform qRT-PCR analysis on the Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus system ( Thermo Fisher Technologies, USA ). PpTEF-2 (Translation Elongation Factor 2) was used as an internal reference gene. Each line of treated peach fruit pieces was used to represent one biological replicate, and at least three technical replicates were analyzed for each biological replicate. The gene-specific primers used to detect the transcriptional level are listed in Table S1.

2.3. Agrobacterium-Mediated Infiltration

For overexpression of PpTIR1, the CDS fragment was ligated into the pCAMBIA3301-121vector by Seamless Cloning Kit (catalog no.D7010M; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) to generate overexpression constructs. The primers used are listed in Table S1. The resulting constructs were transferred into competent cells of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101). Transient expression followed previously published methods [30]. The fruit of 'Okubo' in the developmental stage of S3 were used for infection. Six fruit pieces with a volume of about 1 cm3 were taken on both sides of the ventral suture of peach fruit and cultured on MS medium for 24 h. Then the pieces were soaked in treatment solution and vacuum treated (-70 Kpa). The vacuum is slowly released to help the solution enter the pulp cells. After vacuum infiltration, the fruit pieces were washed three times with sterile water and cultured on MS medium in the growth chamber ( 20 °C, R.H. 85 % ) for 2 days, then quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 ° C for later use. Each single infection of peach pieces was used as one biological replicate, and three biological replicates were analyzed. The empty vector solution was used as a negative control.

2.4. GUS Histochemical Staining

The transiently overexpressed peach fruit pieces were cut into thin slices (1-3mm). GUS staining solution was added to cover the material completely, and placed at room temperature overnight. After that, the material was transferred to anhydrous ethanol for decolorization 2-3 times. The positive blue spots stained by GUS solution were stable and did not fade in alcohol. The negative control was untreated peach fruit pieces, and the positive control was pieces transiently expressing pCAMBIA3301-121.

2.5. Subcellular Localization Analysis

The construction of subcellular localization analysis was based on the cDNA of peach mesocarp. The CDS fragment of PpTIR1 was amplified by primers (Table S1). PpTIR1 without a stop codon and the full-length coding sequences of the genes were amplified by PCR and constructed into pBI121-GFP vectors by viscous terminal ligation. The successfully sequenced PpTIR1-GFP plasmids were transformed into the competent state of GV3101 Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and the bacteria identified were selected for expanded culture, so that the final value of OD600 was 0.4. Tobacco leaves were injected by solution after being kept in darkness for 2-3 hours at room temperature and cultured for 2 days. The marked areas of tobacco leaves were cut, and the GFP fluorescence signals were detected and photos taken by laser scanning confocal microscopy (LeicaSP5, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.6. Yeast Two-Hybrid

The construction of a yeast two-hybrid vector was based on the cDNA of peach mesocarp. The CDS fragments of PpTIR1, PpIAA1, PpIAA3, PpIAA5, PpIAA9 and PpIAA27 were amplified by primers (Table S1). PpTIR1 without a stop codon and the full-length coding sequences of the genes was amplified by PCR and constructed into pGADT7 and pGBKT7 vectors by viscous terminal ligation. The PpTIR1-DBD and PpIAA1/3/5/9/27-AD plasmids were co-transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109, and the yeast cells that contained these two vectors were screened on SD/-Trp-Leu media. When the transformed cells were inoculated on the strict four-deficiency plate SD/-Trp-Leu-His-Ade/X-α-Gal/ auxin, the colonies grew and turned blue, indicating that plasmid successfully constructed and proteins interacted with each other. In addition, pGADT7 and pGBKT7 were used as the negative controls.

2.7. Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementarities

The bimolecular fluorescence complementary vector was constructed using primers (Table S1) to amplify the CDS fragments, PCR to amplify the full-length coding sequence of the non-stop codon gene, and construction in pSPYNE173 and pSPYCE (M) vectors by viscous terminal ligation. The successfully sequenced PpTIR1-YNE and PpIAA1/3/5/9/27-YCE plasmids were transformed into competent Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells respectively, to produce fusion proteins. Two types of bacteria containing different plasmids were mixed with an equal volume, and 100 μM IAA was added simultaneously. The bacterial solution was injected into tobacco leaves and cultured at room temperature for 2 days. A confocal microscope (LeicaSP5, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) was used for observation and to take images.

2.8. Firefly Luciferase Fragment Complementary Image Technique (LCI)

The firefly luciferase fragment complementary image technology vector was constructed using primers (Table S1) to amplify the CDS fragments and PCR to amplify the full-length coding sequence of non-stop codon gene. The vector was constructed in pCAMBIA1300-nLUC and pCAMBIA1300-cLUC vectors using Seamless Cloning Kit (catalog no.D7010M; Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The PpTIR1-nLUC and PpIAA1/3/5/9/27-cLUC constructs successfully sequenced were transformed in Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101), respectively. The suspension was prepared by two types of constructs solution mixed with an equal volume, and 100 μM IAA was added simultaneously. The suspension was injected into the back of tobacco leaves with 1 mL syringe (without the needle). After culture at room temperature for 2 days, the presence of fluorescence in the area where tobacco leaves was injected was determined by imaging in vivo (Tanon-5200muli, Tanon Science & Technology, Inc., Shanghai, China).

3. Results

3.1. Fruit Firmness Decrease can be Delayed by Low Concentration NAA Treatment

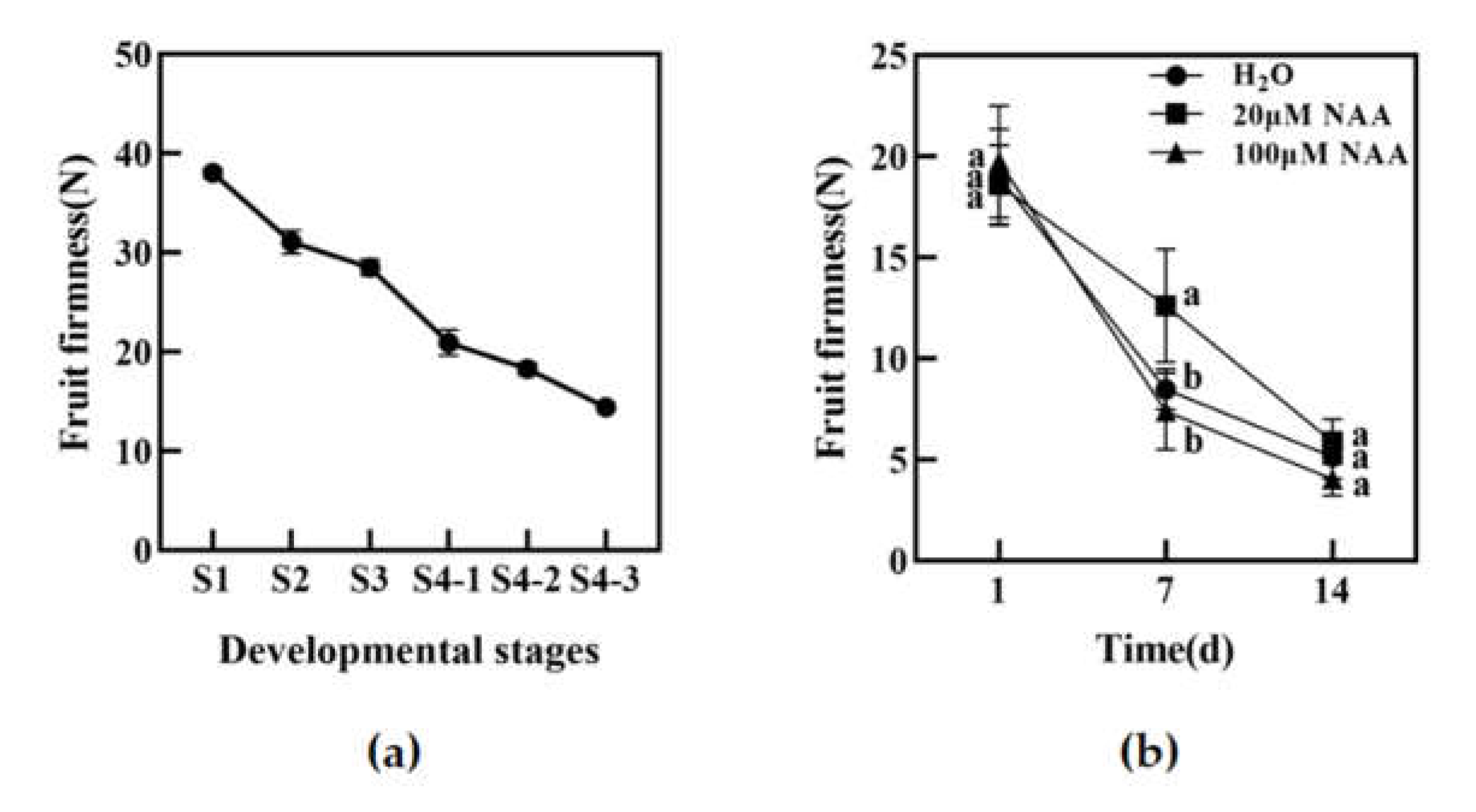

Fruit firmness is an important quality index reflecting fruit texture and storage resistance, and it is also one of the important indexes reflecting fruit softening. As shown in Figure 1a, the fruit firmness of 'Okubo' peach decreased to a certain extent during fruit development and maturation. To clarify the effects of auxin on peach fruit firmness, 'Okubo' peach fruits in the S4-1 period were treated with exogenous hormones NAA. The results are shown in Figure 1b. The firmness of peach flesh decreased in all treatments, but 20 μM NAA treatments delayed the decrease compared with the H2O treatment in 7th. There was no significant difference between the fruit treated with 100 μM NAA and the control after 7 and 14 days. Taken together, these results suggest that low concentration auxin delayed the firmness decrease in peach fruit.

3.2. Low Concentration NAA Treatment Decreased the Activities of Softening-Related Enzymes in Peach Fruit

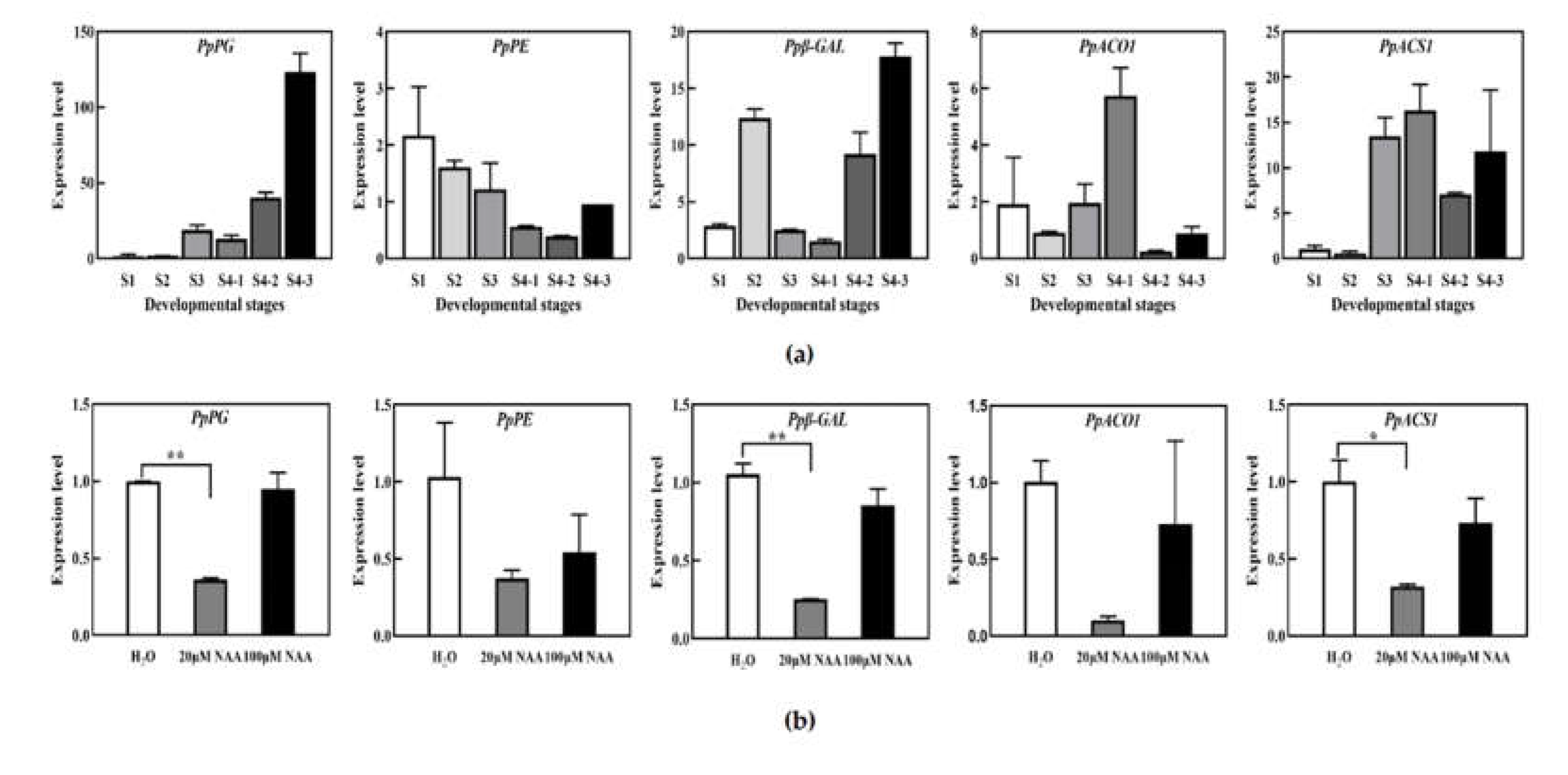

In order to explore the differences of peach fruit softening related enzyme in different development stages, the relative expression levels of fruit cell wall degradation related enzymes PpPE (pectinesterase), PpPG (Polygalacturinase), Ppβ-GAL(β-Galactosidase) and ethylene synthesis related enzymes PpACO1(ACC Oxidase) and PpACS1(ACC synthase) were analyzed by qPCR. As shown in Figure 2a, PpPG and Ppβ-GAL genes suddenly increased in the late stage of fruit development, while the change of PpPE gene was not significant throughout the development period, and the expression levels of PpACO1 and PpACS1 genes increased in the late stage of fruit development. When peach fruits were treated with different concentrations of NAA, it was found that 20uM NAA treatment obviously reduced the transcription level of PpPG and Ppβ-GAL related to cell wall softening, and the expression of PpACS1 genes related to ethylene synthesis. However, there was no significant difference in the expression of these enzymes under 100uM NAA treatment.

3.3. Transient Overexpression of PpTIR1 Gene Affects Expression of Auxin Signal Transduction Factors and Fruit Softening Related Genes

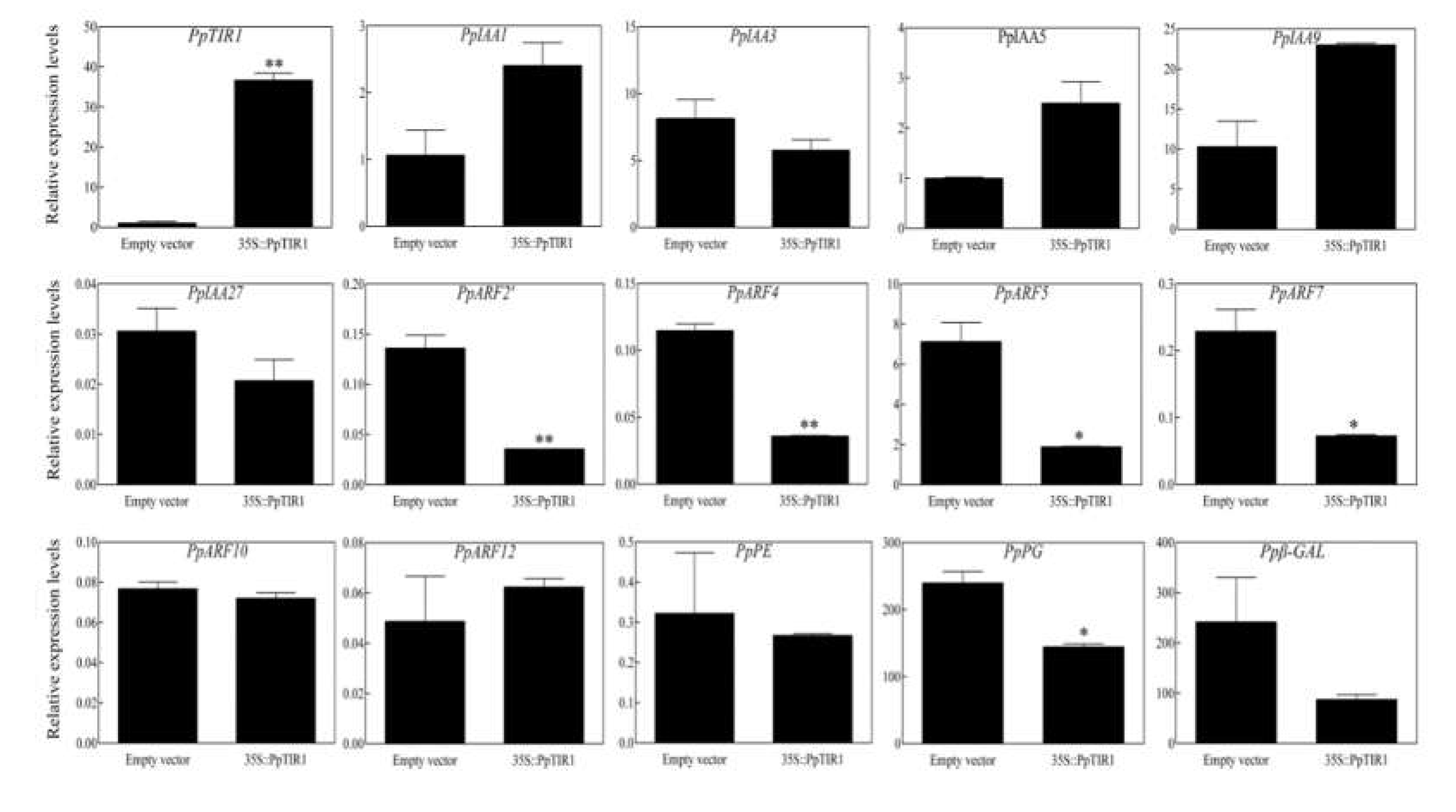

To determine if PpTIR1 participate in the process of peach fruit ripening, the expression level of PpIAAs and PpARFs genes in the auxin signal transduction pathway and those related to cell wall degrading enzymes of fruit softening were detected using qRT-PCR (Figure 3). After transient overexpression of the PpTIR1 gene in piece of peach fruit, its expression increased significantly by approximately 36 times as much as that of the control. The expression of PpIAA1/3/5/9/27 gene did not change significantly, but the level of expression of some PpARF genes changed significantly, among which the expression of PpARF2' and PpARF4 genes was significantly lower by approximately 7 times and 3.7 times lower than that of the control, respectively. The levels of expression of the PpARF5 and PpARF7 genes were lower than that of the control with a decrease of approximately 3.7 times and 3 times, respectively, while the levels of expression of the PpARF10 and PpARF12 genes was not different between the transgenic fruit and control. The overexpression of PpTIR1 affected the expression of some enzymes related to cell wall degradation, in which the expression of PpPG gene decreased by approximately 1.7 times compared with the control, while the expression of PpPE and Ppβ-GAL genes did not change significantly.

3.4. Yeast-2 Hybrid, BiFC, and Luciferase Reporter Assays Suggest that IAA and TIR1 Proteins may Directly Interact

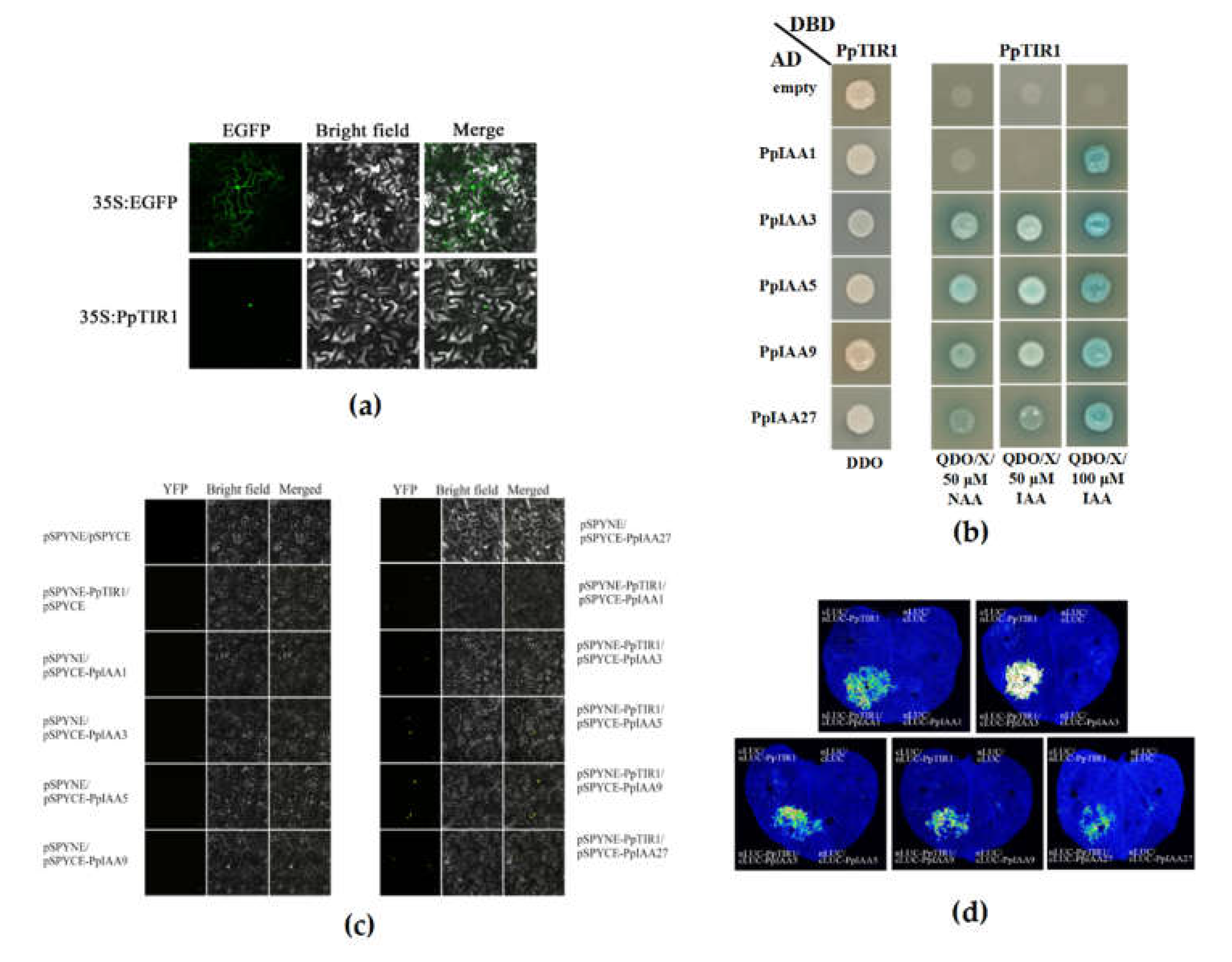

A GFP fusion reporter was used to determine if TIR1 protein localized to the nucleus in tobacco leaves. The coding region of PpTIR1 gene was fused with that of the GFP protein to construct the fusion expression vector PpTIR1-GFP. The fusion expression vector was introduced into tobacco leaf back cells in vivo. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that the full-length PpTIR1::GFP fusions were localized exclusively in the nucleus (Figure 4a).

It has been reported that auxin is required for the interaction between auxin receptor TIR1/AFBs and the Aux/IAA protein that contains domain Ⅱ. Therefore, the Aux/IAA family members of domain Ⅱ in peach were screened out in this study, and five Aux/IAA proteins, which represent different sub-clades of Aux/IAAs and play distinct roles in mediating auxin responses, were selected to determine the interactions with PpTIR1 protein. The Aux/IAA proteins obtained was further to study its regulatory function in peach fruit firmness.

The constructed recombinant plasmid was co-transformed into AH109 yeast receptive cells, and the yeast two-hybrid results are shown in Figure 4b. The yeast cells co-transformed with the recombinant plasmid could grow on DDO (SD/-Trp/-Leu) double-deficiency medium, indicating that the recombinant plasmid co-transformation was successful. Comparable results were observed on QDO/X (SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade+X-α-gal) four-deficiency medium. The yeast co-transformed with the recombinant plasmid could not grow after the addition of 50 μM 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D). The mated yeast (DBD–PpTIR1 and AD–PpIAA3, PpIAA5, PpIAA9or PpIAA27) could grow on the plates following the addition of 50 μM NAA or 50 μM IAA; moreover, 100 μM IAA enhanced the interaction. The binding results confirmed the auxin-induced assembly of stable PpIAA::PpTIR1 co-receptors in yeast.

To further verify the interaction between PpTIR1 and PpIAA proteins, a BiFC assay was used. The yellow fluorescence signal of YFP was observed in the nuclei of tobacco leaf dorsal cells co-transformed with PpTIR1-NYFP and PpIAA1-CYFP, PpIAA3-CYFP, PpIAA5-CYFP, PpIAA9-CYFP and PpIAA27-CYFP constructs in the presence of 100 μM IAA, and an YFP yellow fluorescence signal was not observed in the absence of auxin (Figure 4c). To provide additional evidence for the interaction between PpTIR1 and PpIAA proteins, the firefly luciferase fragment complementary image technique (LCI) test was used in this study. The fluorescence signals could be observed in tobacco leaf back cells co-infected with PpTIR1 and PpIAA1, PpIAA3, PpIAA5, PpIAA9 and PpIAA27 in the presence of 100 μM IAA, but the signals did not appear in tobacco leaf back cells in the absence of auxin (Figure 4d). These results provided additional verification that the interaction between auxin receptor PpTIR1 and PpIAA proteins in peach is dependent on auxin. These results confirmed that PpTIR1 interacts with PpIAA1/3/5/9/27.

4. Discussion

Peach is a kind of respiratory climacteric fruit, and its development and ripening processes experience a series of complex physiological and biochemical changes that relate to size, color, texture, and flavor and fragrance smell. Softening is the most significant textural change during the ripening and postharvest storage of peach fruit, which will not only affect the taste and shelf life of the fruit but also affect the economic benefits of peach industry. Therefore, a study on the mechanism of peach fruit softening has theoretical and practical significance.

It has been reported that there is a relationship between auxin and peach fruit development and softening during ripening. Previous research results from our group showed that the content of IAA in the hard fruit 'Jingyu' was very low and did not increase during the late ripening stage, while the content of IAA in the rapidly dissolving fruit 'Okubo' was significantly higher, which preliminarily revealed that the non-softening of hard fruit was related to low levels of IAA [22]. Therefore, our research focused on the regulation of peach fruit softening by auxin. To explore the relationship between auxin and the softening, 'Okubo' peach fruits in vitro were treated with exogenous NAA at different levels. The results showed that the firmness of peach decrease was delayed after treatment with 20uM NAA, however, 100uM NAA had no obvious effect compared with H2O treatment. These results indicated that low concentration NAA could delay the softening of peach fruit, but there was report indicating a higher accumulation of auxin triggered fast softening of peach fruit [25]. For other flesh fruits, previous studies have reported that exogenous auxin treatment can promote fruit ripening in pears [26]. NAA treatment accelerated the onset of ripening at time points at which apple fruit were not able to ripen naturally [4,27]. However, exogenous auxin treatment can inhibit fruit ripening and softening in strawberry [28] and grape [29,30]. Therefore, the regulatory effect of exogenous auxin on fruit softening may be related to the type of fruit and the concentration of exogenous auxin.

In the auxin signal transduction pathway, after the TIR1/AFBs protein binds to auxin, the Aux/IAAs protein can be degraded through the ubiquitin degradation pathway, thus, relieving the inhibition of transcription factor ARFs, so that the ARFs can regulate the expression of a series of downstream auxin response genes. Therefore, it is of substantial significance to study the interaction between TIR1/AFBs and Aux/IAAs proteins to reveal the physiological function of auxin. Different TIR1/AFBs-Aux/IAAs co-receptors have different results in response to auxin. In Arabidopsis thaliana, rice, tomato and plum, the interaction between TIR1/AFBs and Aux/IAAs proteins was found to depend on auxin, but there was also an auxin-independent interaction in Arabidopsis thaliana and rice [31,32]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the interaction between AtTIR1, AtAFB1, AtAFB2 and AtAFB3 and the AtIAA3/5/7/8/12/28/29/31 protein depends on different concentrations of IAA [31,32]. In tomato, the interaction between SlTIR1/AFBs and the SlAux/IAA protein can be enhanced when exogenous IAA reaches to 100 μM. In plums, PslTIR1, PslAFB2 and PslAFB5 can interact with the AtIAA7 protein in the presence of 100 μM IAA [32]. In this study, there was no interaction between PpTIR1 and the PpIAA1/3/5/9/27 protein in the absence of IAA and 50 μM 2,4-D according to the yeast two-hybrid experiment. There was an interaction between PpTIR1 and the PpIAA3/5/9/27 protein, but the strength of interaction differed depending on the concentration of NAA and IAA. Compared with 50 μM IAA, 100 μM IAA can lead to the interaction between PpTIR1 and the Pp/IAA1 protein. Bimolecular fluorescence complementary and firefly luciferase fragment complementary image techniques were also used to prove the interaction between PpTIR1 and the PpIAA1/3/5/9/27 proteins under the condition of 100 μM IAA. The results of this study reveal that there is an interaction between PpTIR1 and PpIAA proteins, and this interaction may be an important regulatory process involved in the activation of downstream gene expression, thus, realizing the biological function of auxin regulation.

The involvement of TIR1/AFBs in fruit ripening and softening has been reported in some studies [33]. Currently, research on the TIR1/AFBs gene in fruit development, ripening and softening is primarily focused on tomato fruit. In tomato, the overexpression of SlTIR1A affected flower morphology and fruit development, resulting in parthenocarpy formation. This led to the conclusion that SlTIR1A could interact with the SlIAA9 protein and regulate the expression of SlIAA9 and SlARF7 genes at the transcriptional level, thus, affecting fruit setting. The overexpression of SlTIR1B would affect apical dominance, leaf morphology and fruit formation. Other studies on SlTIR1 also showed that the overexpression of SlTIR1 gene caused dwarfing, leaf morphological changes and parthenocarpy in tomato plants. Simultaneously, the overexpression of SlTIR1 gene led to a decrease in the expression of some early auxin response genes, such as SlIAA9, SlARF6 and SlARF7, while the level of expression of SlIAA3 increased [33]. A study on plums showed that the overexpression of PslTIR1 gene led to early fruit setting before flowering, resulting in parthenocarpy and a decrease in the transcription of IAA9 and ARF7 genes. It is hypothesized that PslTIR1 positively regulates auxin response and fruit setting by mediating the degradation of Aux/IAA protein, especially IAA9. In this study, we analyzed the expression of some auxin response genes and cell wall metabolic genes related to fruit firmness by transiently overexpressing the PpTIR1 gene in peach fruit. The results indicated that the overexpression of PpTIR1 gene in peach fruit resulted in a decrease in the expression of PpARF2', PpARF4, PpARF5 and PpARF7 genes, suggesting that the PpTIR1 gene may affect fruit development, ripening and softening by regulating the downstream PpARFs genes. Simultaneously, the overexpression of PpTIR1 gene caused a significant decrease in the expression of PpPG, a gene related to fruit softening, indicating that there was a close relationship between the PpTIR1 gene and peach fruit softening. In a study on plums, it was found that the firmness of plum fruit obtained by the overexpression of PslTIR1 gene was lower than that of wild type fruit, the expression level of soften related genes in transgenic fruit was higher than that in the wild type fruit. These results show that PslTIR1 regulates fruit softening by controlling the level of enzymes related to cell wall decomposition [16]. Whether PpTIR1 can promote or inhibit peach fruit softening need further study.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, PpTIR1 has a regulatory effect on fruit ripening and softening, and the possible manner of regulation is through the interaction between TIR1 and the Aux/IAAs protein to activate the expression of downstream ARFs or other transcription factor genes, thus, further affecting the level of enzymes related to cell wall degradation and ethylene synthesis, which facilitate the regulation of fruit ripening and softening.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: GUS staining to verify the success of PpTIR1 overexpression gene in an isolated peach fruit block; Table S1: Primers for vector construction.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Y.Z.; Methodology, Q.W.; Formal analysis, D.G.; resources, H.Y.; Software, J.W.; Writing—review and editing, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No. 6182003)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Castro, R.I.; González-Feliu, A.; Muñoz-Vera, M.; Valenzuela-Riffo, F.; Parra-Palma, C.; Morales-Quintana, L. Effect of exogenous auxin treatment on cell wall polymers of strawberry fruit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bttcher, C.; Boss, P.K.; Davies, C. , Delaying Riesling grape berry ripening with a synthetic auxin affects malic acid metabolism and sugar accumulation, and alters wine sensory characters. Funct. Plant Biol. 2012, 39, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li. J.; Tao, X.; Li, L.; Mao, L.; Luo, Z.; Khan, Z.U.; Ying, T. Comprehensive RNA-Seq analysis on the regulation of tomato ripening by exogenous auxin. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0156453. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, P.; Lu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Lv, T.; Li, X.; Bu, H.; 1, Liu, W. ; Xu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, A. Auxin-activated MdARF5 induces the expression of ethylene biosynthetic genes to initiate apple fruit ripening. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1781–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, Y.X. Expression and regulation of pear 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase gene (PpACS1a) during fruit ripening, under salicylic acid and indole-3-acetic acid treatment, and in diseased fruit. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 4147–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sharkawy, I.; Sherif, S.M.; Jones, B.; Mila, I.; Kumar, P.P.; Bouzayen, M.; Jayasankar, S. TIR1-like auxin-receptors are involved in the regulation of plum fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 5205–5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Zeng, W.; Liang, N.; Lu, Z.; Liu, H.; Cao, G.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, J.; Li, W.; Fang, W. PpYUC11, a strong candidate gene for the stony hard phenotype in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch), participates in IAA biosynthesis during fruit ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 2015; 22, 7031–7044. [Google Scholar]

- Tadiello, A. , Ziosi, V., Negri, A.S., et al. On the role of ethylene, auxin and a GOLVEN-like peptide hormone in the regulation of peach ripening. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miho, T.; Naoko, N.; Hiroshi, F.; Takehiko, S.; Michiharu, N.; Ken-Ichiro, H.; Hiroko, H.; Hirohito, Y.; Yuri, N. , Increased levels of IAA are required for system 2 ethylene synthesis causing fruit softening in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch). J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuki, M.; Soeno, K.; Shimada,Y. ; Sawamura, Y.; Suesada, Y.; Yaegaki, H.; et al. Insertion of a transposonlike sequence in the 5′-flanking region of the YUCCA gene causes the stony hard phenotype. Plant J. 2018, 96, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainotti, L.; Casadoro, L. The involvement of auxin in the ripening of climacteric fruits comes of age: the hormone plays a role of its own and has an intense interplay with ethylene in ripening peaches. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 3299–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyser, O. Auxin signaling. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176:465–479.

- Ren, Z.; Li, Z.; Miao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Deng, W.; Hao, Y. , The auxin receptor homologue in Solanum lycopersicum stimulates tomato fruit set and leaf morphogenesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2815–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Li, J.; Cui, L.; Zhang, T.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, P.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yu, X.; Lou, Q. New insights into the roles of cucumber TIR1 homologs and miR393 in regulating fruit/seed set development and leaf morphogenesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkawy, I.; Sherif, S.; El Kayal, W.; Jones, B.; Li, Z.; Sullivan, A.; Jayasankar, S. Overexpression of plum auxin receptor PslTIR1 in tomato alters plant growth, fruit development and fruit shelf-life characteristics. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkawy, I.; Sherif, S.M.; Jones, B.; Mila, I.; Kumar, P.; Bouzayen, M.; Jayasankar, S. TIR1-like auxin-receptors are involved in the regulation of plum fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 5205–5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jones, B.; Li, Z.; Frasse, P.; Bouzayen, M. , The tomato Aux/IAA transcription factor IAA9 is involved in fruit development and leaf morphogenesis. Plant Cell. 2005, 17, 2676–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouzayen, M. Genome-wide identification, functional analysis and expression profiling of the Aux/IAA gene family in tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 659–672. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Bassa, C.; Audran, C.; Mila, I.; Cheniclet, C.; Chevalier, C.; Bouzayen, M.; Roustan, J.; Chervin, C. The Auxin Sl-IAA17 transcriptional repressor controls fruit size via the regulation of endoreduplication-related cell expansion. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zeng, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Niu, L.; Pan, L.; Lu, Z.; Cui, G.; Li, G.; Wang, Z. , Over-expression of peach PpIAA19 in tomato alters plant growth, parthenocarpy, and fruit Shape. J Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Guan, D.; Wang, W.; Wang, Q.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y. , Bioinformatics and expression pattern analysis of auxin receptor gene family in peach. Molecular plant breeding, 2021, 20, 6331–6340. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, D.; Hu, X.; Diao, D.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y. , Genome-wide analysis and identification of the Aux/IAA gene family in peach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, D.; Hu, X.; Guan, D.; Wang, F.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y. Genome-wide identification of the ARF (Auxin Response Factor) gene family in peach and their expression analysis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 4331–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Estelle, M. , Diversity and specificity: auxin perception and signaling through the TIR1/AFB pathway. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 21, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco-Valenzuela, T.; Muñoz-Espinoza, C.; Riveros, A.; Pedreschi, R.; Arús, P.; Campos-Vargas, R.; Meneses, C. Expression QTL (eQTLs) analyses reveal candidate genes associated with fruit flesh softening rate in peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch]. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, Y. Expression and regulation of pear 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase gene (PpACS1a) during fruit ripening, under salicylic acid and indole-3-acetic acid treatment, and in diseased fruit. Mol. Biol. Rep.. 2014, 41, 4147–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Tan, D.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, H.; Li, T.; Wang, A. Apple (Malus domestica) MdERF2 negatively affects ethylene biosynthesis during fruit ripening by suppressing MdACS1 transcription. Plant J. 2016, 88, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, R.; González-Feliu, A.; Muñoz-Vera, M.; Valenzuela-Riffo, F.; Parra-Palma, C.; Morales-Quintana, L. Effect of exogenous auxin treatment on cell wall polymers of strawberry fruit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Xie, Z.; Wang, C.; Shangguan, L.; Qian, N.; Cui, M.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, T.; Wang, M.; Fang, J. Abscisic acid, sucrose, and auxin coordinately regulate berry ripening process of the Fujiminori grape. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 2017, 17, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Santo, S.; Tucker, M.; Tan, H.; Burbidge, C.; Fasoli, M.; Böttcher, C.; Boss, P.; Pezzotti, M.; Davies, C. Auxin treatment of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) berries delays ripening onset by inhibiting cell expansion. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 103, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ma, B.; Zhou, Y.; He, S.; Tang, S.; Lu, X.; Xie, Q.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J. , E3 ubiquitin ligase SOR1 regulates ethylene response in rice root by modulating stability of Aux/IAA protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 4513–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, E.S.; Sherif, S.M.; Brian, J.; Isabelle, M.; Kumar, P.P.; Mondher, B.; Subramanian, J. , TIR1-like auxin-receptors are involved in the regulation of plum fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 5205–5215. [Google Scholar]

- Chaabouni, S.; Jones, B.; Delalande, C.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Mila, I.; Frasse, P.; Latché, A.; Pech, J.; Bouzayen, M. , Sl-IAA3, a tomato Aux/IAA at the crossroads of auxin and ethylene signalling involved in differential growth. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1349–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The firmness of peach fruit at different developmental stages (a) and the change of peach fruit firmness under NAA treatment (b). Vertical bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences between the groups (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

The firmness of peach fruit at different developmental stages (a) and the change of peach fruit firmness under NAA treatment (b). Vertical bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences between the groups (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Expression levels of fruit softening related genes and ethylene synthesis related genes at different developmental stages (a) and under NAA treatment (b).

Figure 2.

Expression levels of fruit softening related genes and ethylene synthesis related genes at different developmental stages (a) and under NAA treatment (b).

Figure 3.

Effects of the over-expressed PpTIR1 gene in an isolated peach fruit block on the relative expression levels of some PpIAAs, PpARFs and enzymes related to cell wall degradation (*p <0.05, **p <0.01).

Figure 3.

Effects of the over-expressed PpTIR1 gene in an isolated peach fruit block on the relative expression levels of some PpIAAs, PpARFs and enzymes related to cell wall degradation (*p <0.05, **p <0.01).

Figure 4.

Subcellular localization of PpTIR1proteins fused to the GFP tag and the interaction between PpTIR1 and some PpIAA proteins. PpTIR1-GFP fusion proteins were transiently expressed in leaves of Nicotianatabacum, and their subcellular localization was determined by confocal microscopy (a). The yeast cells co-transformed with the recombinant plasmid could grow on DDO (SD/-Trp/-Leu) double-deficiency medium, indicating that the recombinant plasmid co-transformation was successful. Comparable results were observed on QDO/X (SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade+X-α-gal) four-deficiency medium, Greenish blue indicates positive interactions (b). The interaction between PpTIR1 and some PpIAA proteins was verified by bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Yellow fluorescence indicates positive interactions (c). A firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay was used to verify th interaction between PpTIR1 and some PpIAA proteins. There are four injection points on each tobacco leaf. The upper right is nLUC/cLUC; the upper left is cLUC/nLUC-PpTIR1; the lower right is nLUC/cLUC-PpIAA1, 3, 5, 9, 27, and the lower left is nLUC- PpTIR1/ cLUC-PpIAA1, 3, 5, 9, 27 (d). Scale bar: 20 μm.

Figure 4.

Subcellular localization of PpTIR1proteins fused to the GFP tag and the interaction between PpTIR1 and some PpIAA proteins. PpTIR1-GFP fusion proteins were transiently expressed in leaves of Nicotianatabacum, and their subcellular localization was determined by confocal microscopy (a). The yeast cells co-transformed with the recombinant plasmid could grow on DDO (SD/-Trp/-Leu) double-deficiency medium, indicating that the recombinant plasmid co-transformation was successful. Comparable results were observed on QDO/X (SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade+X-α-gal) four-deficiency medium, Greenish blue indicates positive interactions (b). The interaction between PpTIR1 and some PpIAA proteins was verified by bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Yellow fluorescence indicates positive interactions (c). A firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay was used to verify th interaction between PpTIR1 and some PpIAA proteins. There are four injection points on each tobacco leaf. The upper right is nLUC/cLUC; the upper left is cLUC/nLUC-PpTIR1; the lower right is nLUC/cLUC-PpIAA1, 3, 5, 9, 27, and the lower left is nLUC- PpTIR1/ cLUC-PpIAA1, 3, 5, 9, 27 (d). Scale bar: 20 μm.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated