Submitted:

17 May 2023

Posted:

18 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

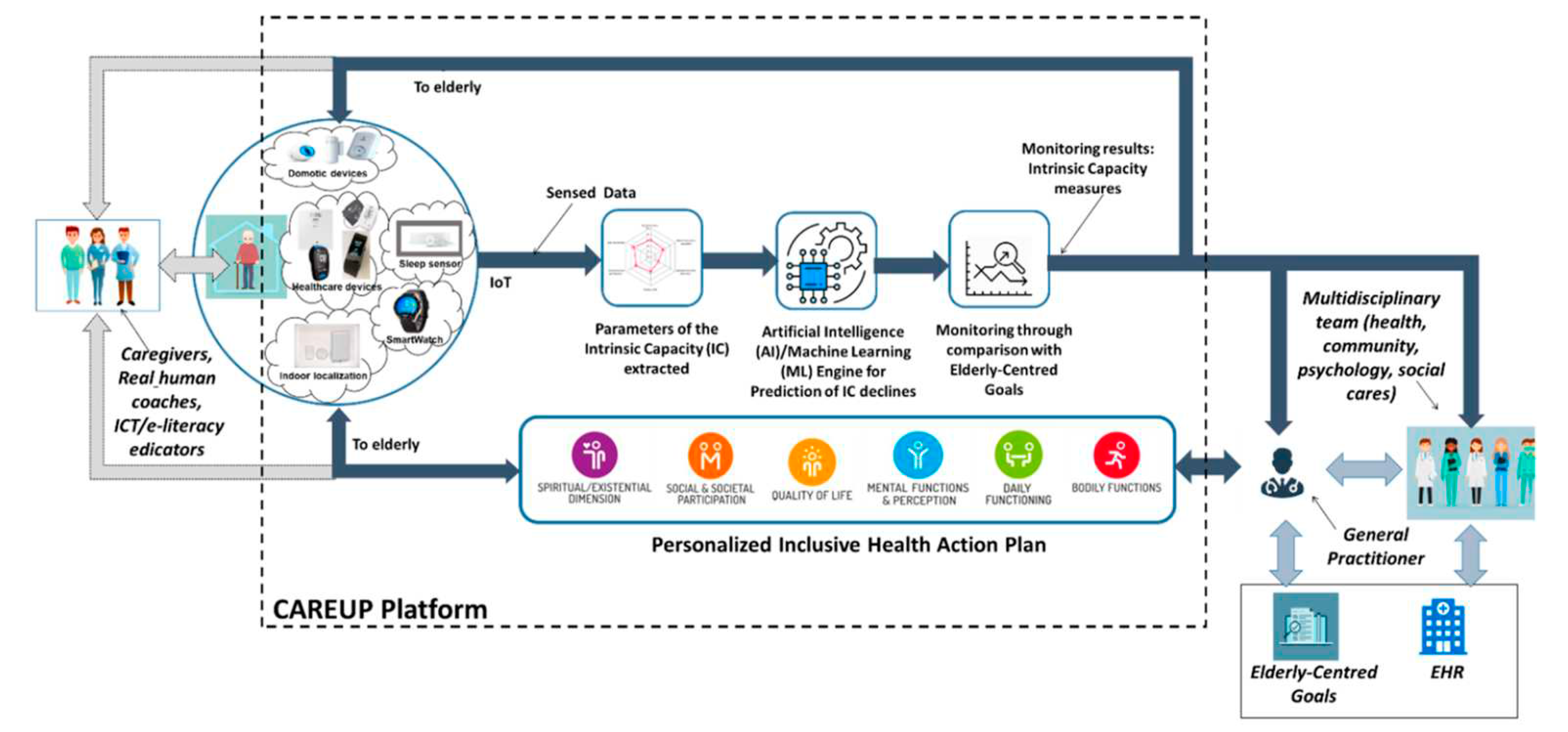

2.1. The CAREUP-based intervention

2.2. The method

2.3. The end-users’ involvement and recruiting strategy

2.3. The interview administration

3. Results

3.1. Primary Users

3.1.1. Sample description

3.1.2. Attitude to health and the use of eHealth technology

3.1.3. Care Plan: Decision making process, Desired and useful features, Perceived barriers

3.2. Secondary Users

3.2.1. Sample description

3.2.2. Perspective on the CAREUP solution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Constitution. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Human aging: Usual and successful. Science 1987, 237, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, M.; Knottnerus, J.A.; Green, L.; van der Horst, H.; Jadad, A.R.; Kromhout, D.; Leonard, B.; Lorig, K.; Loureiro, M.I.; van der Meer, J.W.M.; et al. How should we define health? BMJ-Brit. Med. J. 2011, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abud, T.; Kounidas, G.; Martin, K.R.; Werth, M.; Cooper, K.; Myint, P.K. Determinants of healthy ageing: A systematic review of contemporary literature. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission, Shifting Health Challenges. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/shifting-health-challenges_en (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Golino, H.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; Sadana, R.; Teles, M.; Christensen, A.P.; Boker, S.M. Investigating the broad domains of intrinsic capacity, functional ability and environment: An exploratory graph analysis approach for improving analytical methodologies for measuring healthy aging. 2020.

- Cesari, M.; Araujo de Carvalho, I.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; Cooper, C.; Martin, F.C.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Vellas, B.; Beard, J.R. Evidence for the domains supporting the construct of intrinsic capacity. J. Gerontol. 2018, 73, 1653–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlomann, A.; Seifert, A.; Zank, S.; Woopen, C.; Rietz, C. Use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) devices among the oldest-old: Loneliness, anomie, and autonomy. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, igz050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ienca, M.; Schneble, C.; Kressig, R.W.; Wangmo, T. Digital health interventions for healthy ageing: A qualitative user evaluation and ethical assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 9241-210:2010, Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/52075.html (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Norman, C.D.; Skinner, H.A. eHealth literacy: Essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. J. Med. Internet Res. 2006, 8, e506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, C. Health effects of social isolation and loneliness. J. Aging Life Care 2018, 28, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm, M.; Frost, H.; Cowie, J. Loneliness and social isolation causal association with health-related life-style risk in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangão, M.O. Self-perceived health status. In Handbook of Research on Health Systems and Organizations for an Aging Society; Fonseca, C., Lopes, M.J., Mendes, D., Mendes, F., García-Alonso, J., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chipps, J.; Jarvis, M.A.; Ramlall, S. The effectiveness of e-Interventions on reducing social isolation in older persons: A systematic review of systematic reviews. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 23, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y. Perceived benefits. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2013; pp. 1450–1451. [Google Scholar]

- Quan-Hasse, A.; Williams, C.; Kicevski, M.; Elueze, I.; Wellman, B. Dividing the grey divide: Deconstructing myths about older adults’ online activities, skills, and attitudes. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 1207–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreurs, K.; Quan-Haase, A.; Martin, K. Problematizing the digital literacy paradox in the context of older adults’ ICT use. Can. J. Commun. 2017, 42, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, I.; Schwartz, E.; Xi, W.; Buttigieg, S.C.; McDonnell-Naughton, M.; Wouters, E.J.M.; van Zaalen, Y. Inclusion of older adults in the research and design of digital technology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons Foundation, How Decision-Making Changes with Age. Available online: https://www.simonsfoundation.org/2022/03/02/how-decision-making-changes-with-age (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- De Angeli, A.; Jovanovi´c, M.; McNeill, A.; Coventry, L. Desires for active ageing technology. Int. J. Hum. Comput. 2020, 138, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucchi, L.; Jayousi, S.; Caputo, S.; Paoletti, E.; Zoppi, P.; Geli, S.; Dioniso, P. How 6G Technology Can Change the Future Wireless Healthcare. In 2020 2nd 6G Wireless Summit (6G SUMMIT), Levi, Finland, 17-20 March 2020.

- United Nations, The Age of Digital Interdependence: Report of the UN Secretary-General's High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3865925 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Menghi, R.; Ceccacci, S.; Gullà, F.; Cavalieri, L.; Germani, M.; Bevilacqua, R. How Older People Who Have Never Used Touchscreen Technology Interact with a Tablet. In Human-Computer Interaction-INTERACT 2017, Mumbai, India, 25-29 September 2017.

- Bevilacqua, R.; Felici, E.; Marcellini, F.; Glende, S.; Klemcke, S.; Conrad, I.; Esposito, R.; Cavallo, F.; Dario, P. Robot-era Project: Preliminary Results on the System Usability. In Design, User Experience, and Usability: Interactive Experience Design, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2-7 August 2015.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).