1. Introduction

In ultrasound (US), the nerve cross-sectional area (CSA) has been used for several years and evolved as a diagnostic marker, particularly in compression or peripheral neuropathies. Both, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy (CIDP) and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) are commonly related to CSA enlargement, but - depending on disease stage and genetic background - unaltered CSA values have been found as well [

1]. For example, untreated CIDP patients exhibit larger CSA, probably indicative of greater disease activity, than treated patients [

2].

In amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), CSA heterogeneity is even greater, and patients show reduced, unaltered or enlarged CSA, hampering the translation of nerve US as a pure diagnostic marker into the clinic [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Nerve microvascular blood flow seems to have the potential to indicate inflammation and could in that be a valuable pathophysiological marker across disease entities [

9,

10,

11].

This study investigates CSA and nerve microvascular blood flow of the tibial nerve in a small cohort of ALS, CIDP and CMT patients, which are part of a larger multimodal study applying fusion imaging between nerve US and ultra-high resolution 7 Tesla (T) magnetic resonance neurography (MRN). Ultrasound markers were set into relation to nerve conduction study, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) parameters and clinical diagnostics; with a particular focus on the identification of subtypes within the disease entities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg (No 16/17 13.02.2017 plus addendum 16.03.2018) and all study participants gave written informed consent.

2.2. Patients and Subjects

2.2.1. Recruitment

Recruitment of ALS, CIDP and CMT patients took place from the neuromuscular outpatient clinics of the Departments of Neurology from the Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg, the Hannover Medical School, and the Rostock University Medical Center, Germany.

Age- and sex-matched healthy controls without any neurological or neuromuscular disorder and without neurological symptoms (e.g. tingling paresthesias, paresis, muscle atrophy) were taken from an already existent pool of the Department of Neurology, Magdeburg [

8,

12,

13].

2.2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

ALS patients were included based on the revised El-Escorial criteria with definite, probable, and possible disease [

14]. CIDP patients were included based on the EFNS criteria with appropriate clinical symptoms, nerve conduction studies, and typical cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings [

15]. Prerequisites for the study participation in the group of hereditary neuropathies were typical symptoms and nerve conduction studies, as well as a positive molecular genetic finding for a hereditary neuropathy [

16].

Exclusion criteria were unconfirmed or incomplete diagnoses and secondary diagnoses which made a clear assignment of neurological symptoms to one of the included diagnoses (ALS, CIDP or CMT) difficult or impossible: Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) with neuropathic symptoms, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, positive alcohol and medication history with suspicion of toxic neuropathy or neurological diagnoses with severe impairment of the lower extremity (stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral tumor, peripheral nerve damage due to trauma).

2.2.3. Number of Participants

According to the above criteria, 11 ALS patients, 5 CIDP patients and 5 patients with hereditary neuropathy (4 patients with CMT 1A and one patient with CMT 2A), as well as 15 healthy subjects could be included in the study. Three participants (one CMT patient and two controls) had unilateral ultrasound measures only.

2.3. CSF Data

To determine blood-nerve barrier leakage, total CSF protein concentration (TPC) and albumin quotient (QAlb) were included from 10 ALS and 4 CIDP patients. The timespan between lumbar puncture and US was -4.10 (-0.07 to -109.93) months.

2.4. Quantification of Clinical Symptoms

Clinical symptoms in ALS patients were assessed using the ALS Functional Rating Scale/revised (ASLFRS/R) and statistical analysis took into account the total score (in 12 different categories: speech, salivation, swallowing, handwriting, feeding, dressing/personal hygiene, turning in bed, walking, climbing stairs, dyspnea, orthopnea, and respiratory insufficiency. Each ranging from 0 points = severely impaired/impossible to 4 points = normal/unimpaired) and gross motor function sub-score (turning in bed, walking, climbing stairs, 0-12 points) [

17].

Clinical symptoms in patients with CIDP were quantified using the overall neuropathy limitation scale (ONLS) and statistics were run for the total and the sub-score grading leg disability (Arms grade score: 0 = normal to 5 = disability of both arms prevents all purposeful movements, Legs grade score: 0 = walking/climbing stairs/running unimpaired to 7 = confined to wheelchair or bed, no purposeful movements of legs possible) [

18].

In patients with CMT disease, clinical symptoms were assessed using the CMT Neuropathy Score (CMTNS), which is divided into nine different categories (subjective sensory and motor symptoms, pin sensibility, vibration, arm and leg strength, electrophysiological measurement of the ulnar nerve), each assigned 0-4 points. Overall, a distinction is made between 0-10 points = mildly affected, 11-20 = moderately affected, 21-36 = severely affected. In addition, a modified subscore to quantify lower extremity limitations (subjective sensory an motor symptoms of the legs, pin sensibility, vibration, leg strength; 0-20 points) was employed [

19].

Using the Medical Research Council (MRC)-Sum score (0-60 points), muscle strength grades of the upper/lower extremities and also separately for the lower extremity strength grades (0-30 points) were determined in patients with polyneuropathy (CIDP and CMT) [

20]. The clinical assessment of the symptoms, scoring and US measurement were performed on the same day.

2.5. Nerve Conduction Studies

Bilateral electrophysiology was available for all CIDP and CMT patients. For statistical analysis motor tibial nerve conduction velocity and amplitudes were considered. The time interval between nerve conduction study and US measurement was -1.10 (0.00 to – 7.50) months.

2.6. Imaging

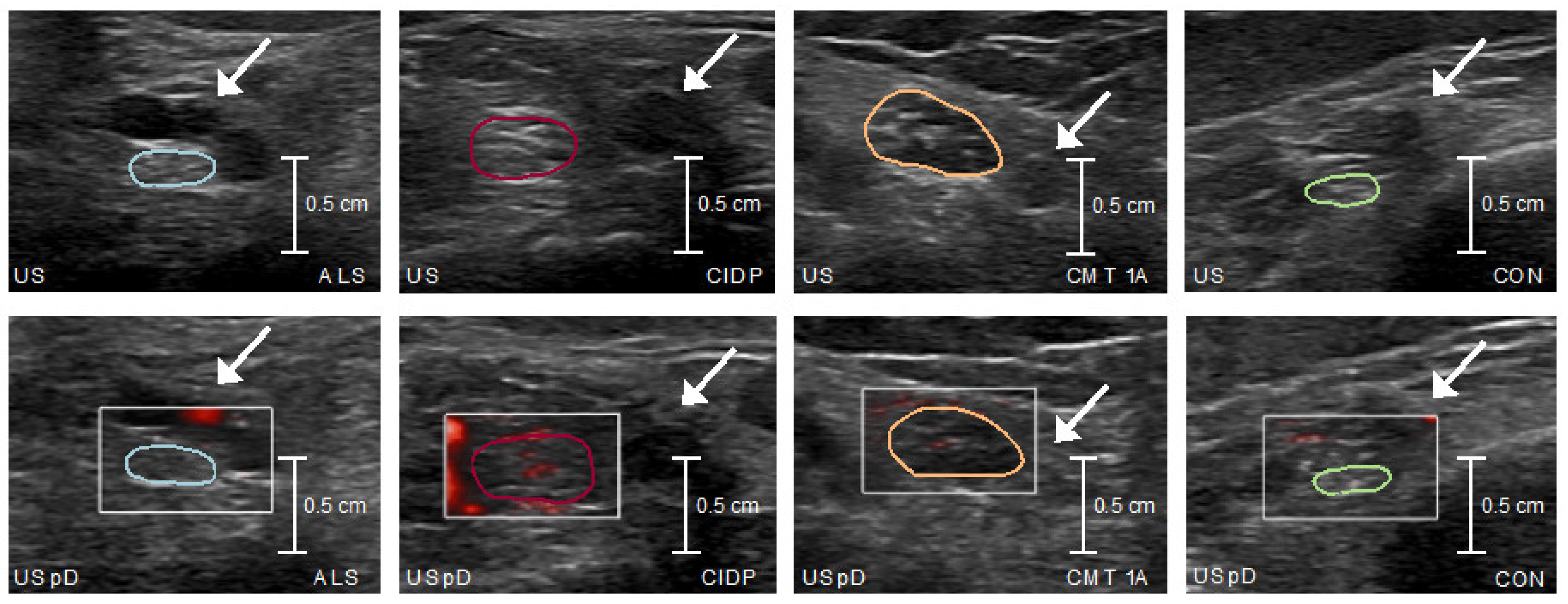

2.6.1. High-Resolution Nerve Ultrasound

Nerve US was performed using a Philips Medical System, Affiniti 70G with an eL18-4 18-MHz broadband ultrasound probe. For this purpose, the study participants lay on an examination couch. B-mode images of bilateral tibial nerves were documented 6 times per side and tibial nerve microvascular blood flow was recorded in three videos per side. Measurements took place at a commonly investigated anatomical location [

21], proximal to the tarsal tunnel at the medial malleolus before branching into the plantar nerves, and were conducted by an experienced investigator (S.S.) blinded against electrophysiology, CSF and clinical patient data. The choice of the anatomical location was further motivated based on the fact that it can be easily detected by the knee coil used in 7T-MRN and make fusion between MRN/ultrasound readily possible [

22].

2.6.2. Analysis of the Image Material

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) US images were analyzed offline by a second investigator (A.H.), not blinded against patient data.

Tibial nerve CSA was manually delineated without the hyperechogenic epineurium using MANGO (Multi-image analysis GUI) [

23].

Microvascular blood flow was visually quantified as follows: grade 0: no blood flow; grade 1: 1 or 2 focal color-encoded spots; grade 2: 1 linear color-encoded line or >2 focal color-encoded spots; grade 3: >1 linear color-encoded line [

24]. Therefore, the video footage (á 30 seconds) of microvascular blood flow measurement by power Doppler was converted into 268 frames, and every 10

th frame was determined visually, so that neuronal blood flow was averaged from a total of 26 individual measures per side.

2.7. Statistics

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) was used for statistical analysis. Normal distribution was assessed through Shapiro-Wilk test. For subgroup comparisons, T-Test, Mann-Whitney-U-Test and Chi-Square-Test were used for demographics, while one-way ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis-Test, both with post-hoc Bonferroni adjustment, were applied for the US data. Pearson’s and Spearman’s rank bivariate correlations were adopted to relate US with electrophysiology, CSF and clinical data in each diagnostic group, respectively. The median split was used to divide the disease groups into severe and mild clinical subgroups, respectively, and then compared with respect to imaging parameters using T-test or Mann-Whitney U-test to distinguish possible inflammatory subgroups.

The intra- and interrater reliabilities for US measures were determined through the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). For this purpose, five measurement series for CSA and microvascular blood flow (each left and right sides) were randomly selected from the entire cohort. ICC was very good to excellent for CSA (intra-rating 0.981, inter-rating 0.976) and blood flow (0.908; 0.816). The interrater (L.W.) was completely blinded against diagnosis and any clinical data.

3. Results

Demographical data are summarized in

Table 1. Subgroups did not differ with regard to age, height, weight and sex. CMT patients had the longest disease duration, followed by CIDP and ALS patients. US and electrophysiology measures did not differ between left and right limb (Supplemental Table) and were averaged for further analysis. When considering the entire cohort, greater CSA was related to younger age, higher weight, and longer disease duration (

Table 2), as well as greater microvascular blood flow (rho=0.375; p=0.024).

Microvascular blood flow did not correlate with any of the demographics, nor with disease duration (

Table 2).

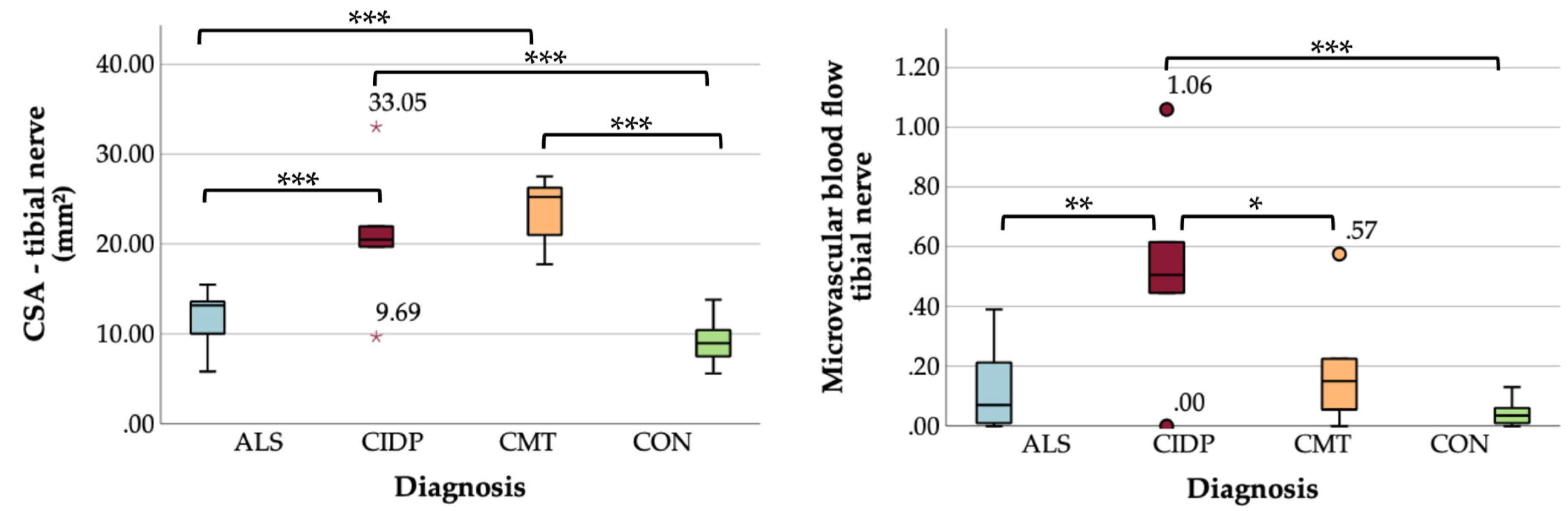

Comparing US measurements among subgroups, CSA was significantly larger in CMT and CIDP compared to ALS and controls, and microvascular blood flow was greatest in the CIDP cohort and higher than in CMT, ALS, and controls (

Table 3 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

In ALS, CSA showed a large-effect size positive correlation with CSF QAlb and with CSF TPC on a trend-level (

Table 4). Comparing ALS patients with blood-nerve barrier leakage (according to QALb > 8 x 10

-3 [

25]) against those without leakage, CSA was slightly larger in the first group (trend-level). There were no associations between microvascular blood flow and CSF parameters (

Table 4 and Supplemental Figure). In CIDP, no correlation between CSF data (TPC, QAlb) and US measures emerged (

Table 4).

When comparing clinical symptoms using adapted scores and imaging parameters (CSA, microvascular blood flow), there was a large-effect size positive correlation between microvascular blood flow and ALSFRS/R gross-motor sub-score in ALS, i.e. greater flow was related to better preserved gross motor function. However, relationship did not survive adjustment for multiple comparisons (

Table 5).

In CIDP and CMT, US data did not correlate with any of the clinical or electrophysiological data (

Table 5 and

Table 6). After subdividing the respective disease groups (ALS, CIDP, and CMT) into mildly or severely affected based on clinical scores, we could not demonstrate any differences in imaging parameters (Supplemental Tables).

4. Discussion

We here show, that tibial nerve CSA and microvascular blood flow differ between CIDP, CMT and ALS. CIDP patients showed enlarged CSA and greatest microvascular blood flow, while CMT patients had enlarged CSA without increased flow, and in ALS both US parameters did not differ from the controls. Interestingly, we found an ALS-subgroup with larger CSA values, that has blood nerve barrier leakage and probably better-preserved motor function.

Our results replicate previous findings reporting group differences for CSA and flow [

10,

26,

27,

28]. The relationship between CSA and body weight is quite well accepted [

28,

32,

33]. An inverse correlation between CSA and age has, on the contrary, rarely been reported [

28,

32,

34]. In our study, this relationship could be best explained by the large CSA in CMT, who had the largest CSA and the youngest age. We could further show, that these US markers differ between peripheral neuropathies, ALS and controls in even very small-sized samples and – for flow – by just applying a simple semi-quantitative approach, supporting the parameters’ diagnostic robustness. While CSA enlargement and microvascular blood flow in CIDP and CMT have mainly been studied in the proximal and upper limb nerves, there has been only rarely a focus on the distal tibial nerve [

1,

10,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. With the exception of one study, uncovering likewise unaltered nerve blood flow, to the best of our knowledge little is known about nerve microvascular flow in ALS so far [

31].

In this independent cohort we replicated our previous results and these of others, reporting an ALS sub-group with larger CSA and, probably, increased nerve microvascular flow in face of blood nerve barrier leakage, supposedly pointing towards the existence of an inflammatory disease subtype [

6,

8,

35]. Of clinical relevance is the hint, that this subtype might display sustained motor function, and – most likely – better long-term outcome [

8]. Ultrasound could be a very valuable (and relatively unique) bedside tool, to identify these patients in the clinic. Thus, the potential of nerve US goes far beyond distinguishing ALS from ALS mimicking neuropathies and may have additional prognostic value. Similarly, in CIDP, CSA and blood flow are establishing as markers for therapeutic-decision making and monitoring [

2,

9,

36,

37]. In CMT, US (and in particular blood flow) could as well aid in the

in-vivo stratification of accompanying nerve inflammation and disease overlaps between CMT and CIDP and could support a refined disease management in peripheral hereditary neuropathies [

38]. This exciting field of the spectrum of peripheral inflammation and degeneration demands in-depth elaboration and rethinking of disease classification in a multicenter design.

The lack of correlation between CSA and electrophysiological scores in CMT and CIDP, as well as the lack of correlation between CSA and clinical symptoms in all three disease subgroups (ALS, CIDP, and CMT), are most likely explained by the small case numbers. Especially for ALS and CIDP, similar results have been shown in the literature [

6,

8,

31]. The missing correlation between ultrasound and electrophysiology might also be explained by the different focus of the two examination techniques. Whereas ultrasound is used to study the focal morphology of a nerve, electrophysiology measures nerve functionality [

6]. Also, peripheral nerve degeneration, i.e. smaller CSA, or peripheral nerve inflammation, i.e. greater CSA, might not necessarily explain the entire variance in nerve function and clinical status. Other limitations of our study include investigators not fully blinded, not all lifestyle factors covered in a controlled manner, and different time intervals between ultrasound measurement and electrophysiology or lumbar puncture for the patients, making a clear comparison difficult. Nevertheless, differences between ultrasound parameters could be shown with very small sample sizes, which support their robustness and should be followed up in further analyses.

The lack of correlation, however, might be superable by the establishment and application of additional US markers, better reflecting the already existent axonal damage and nerve degeneration (e.g. gray scale markers or fascicle measures). Future studies should focus on (i) the validation of CSA and nerve microvascular blood flow as parameters of inflammation by combining these measures with inflammatory peripheral blood biomarkers and (ii) the predictive/prognostic value of these US parameters for the clinic.

Our upcoming analysis, will take already into account the combination of multimodal measures such as US CSA and microvascular blood flow with 7T MRN data, e.g. fascicular T2 intensity and area, to classify the disease subgroups along the spectrum of nerve inflammation and degeneration down to and based on the pathology level.

5. Conclusions

We here demonstrate that US CSA and microvascular blood flow are robust diagnostic markers distinguishing neuropathies and ALS even in very small-sized samples. CSA and flow may have the potential to uncover an ALS disease subtype with more pronounced peripheral nerve inflammation and better sustained clinical function. Our upcoming studies will take advantage of multimodal fusion imaging between US and MRN to disentangle the spectrum of neuroinflammation to neurodegeneration across the disease groups of peripheral neuropathies and ALS, which will prospectively allow a pathophysiologically-based classification to refine therapeutic decision making.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Correlation and comparison between ultrasound measurements in the entire cohort. Ultrasound measures did not differ between the left and right limb; Table S2: Correlation and comparison between nerve conduction study – tibial nerve. Electrophysiology measures did not differ between the left and right limb; Figure S1. Box plots ALS – Blood-nerve barrier leakage. Shows the imaging parameters (CSA and microvascular blood flow) in ALS patients with blood-nerve barrier leakage against those without leakage. Table S3: Subgroup comparison clinical scores – ALS. Clinical ALS-subgroups show no differences for imaging parameters. Table S4: Subgroup comparison clinical scores – CIDP. Clinical CIDP-subgroups show no differences for imaging parameters. Table S5: Subgroup comparison clinical scores – CMT. Clinical CMT-subgroups show no differences for imaging parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H., S.P., J.P., S.G.M., S.V. and S.S.; methodology, A.H. and S.S.; software, F.S.; validation, F.S., S.S.; formal analysis, A.H.; investigation, A.H., L.W., S.S.; resources, S.P., J.P., S.V.; data curation, A.H. and C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, A.H., P.A., S.P., J.P., S.G.M., Y.W., S.H. and S.S.; visualization, A.H.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.V. and S.S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Stiftung für Medizinische Wissenschaft, grant number 02728/STV.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local ethics committee of Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg (No 16/17 13.02.2017 plus addendum 16.03.2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christa Sobetzko for the administrative support of the patient appointments and Anne-Katrin Baum for the excellent technical support in performing the electrophysiological measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

S.P. received honoraria as a speaker/consultant from Biogen GmbH, Roche, Novartis, Teva, Cytokinetics Inc., Desitin, Zambon, Amylyx; and grants from DGM e.V, Federal Ministry of Education and Research, German Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development, EU Joint Programme for Neurodegenerative Disease Research.

References

- Zaidman, C.M.; Harms, M.B.; Pestronk, A. Ultrasound of Inherited vs. Acquired Demyelinating Polyneuropathies. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 3115–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidman, C.M.; Pestronk, A. Nerve Size in Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Neuropathy Varies with Disease Activity and Therapy Response over Time: A Retrospective Ultrasound Study: Nerve Size in CIDP. Muscle Nerve 2014, 50, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, M.S.; Walker, F.O.; Griffin, L.P.; Caress, J.B. Peripheral Nerve and Muscle Ultrasound in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Ultrasound in ALS. Muscle Nerve 2011, 44, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodera, H.; Takamatsu, N.; Shimatani, Y.; Mori, A.; Sato, K.; Oda, M.; Terasawa, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Kaji, R. Thinning of Cervical Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves in ALS as Measured by Sonography. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 125, 1906–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, S.; Abdulla, S.; Debska-Vielhaber, G.; Machts, J.; Dannhardt-Stieger, V.; Feistner, H.; Oldag, A.; Goertler, M.; Petri, S.; Kollewe, K.; et al. Peripheral Nerve Ultrasound in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Phenotypes: Ultrasound in ALS Phenotypes. Muscle Nerve 2015, 51, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A.; Décard, B.F.; Athanasopoulou, I.; Schweikert, K.; Sinnreich, M.; Axer, H. Nerve Ultrasound for Differentiation between Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Multifocal Motor Neuropathy. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noto, Y.-I.; Garg, N.; Li, T.; Timmins, H.C.; Park, S.B.; Shibuya, K.; Shahrizaila, N.; Huynh, W.; Matamala, J.M.; Dharmadasa, T.; et al. Comparison of Cross-Sectional Areas and Distal-Proximal Nerve Ratios in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Diagnostic Nerve US in ALS. Muscle Nerve 2018, 58, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.; Schreiber, F.; Garz, C.; Debska-Vielhaber, G.; Assmann, A.; Perosa, V.; Petri, S.; Dengler, R.; Nestor, P.; Vielhaber, S. Toward in Vivo Determination of Peripheral Nervous System Immune Activity in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2019, 59, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedee, H.S.; Brekelmans, G.J.F.; Visser, L.H. Multifocal Enlargement and Increased Vascularization of Peripheral Nerves Detected by Sonography in CIDP: A Pilot Study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 125, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carandang, M.A.E.; Takamatsu, N.; Nodera, H.; Mori, A.; Mimura, N.; Okada, N.; Kinoshita, H.; Kuzuya, A.; Urushitani, M.; Takahashi, R.; et al. Velocity of Intraneural Blood Flow Is Increased in Inflammatory Neuropathies: Sonographic Observation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2017, 88, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörner, M.; Schreiber, F.; Stephanik, H.; Tempelmann, C.; Winter, N.; Stahl, J.-H.; Wittlinger, J.; Willikens, S.; Kramer, M.; Heinze, H.-J.; et al. Peripheral Nerve Imaging Aids in the Diagnosis of Immune-Mediated Neuropathies—A Case Series. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, S.; Oldag, A.; Kornblum, C.; Kollewe, K.; Kropf, S.; Schoenfeld, A.; Feistner, H.; Jakubiczka, S.; Kunz, W.S.; Scherlach, C.; et al. Sonography of the Median Nerve in CMT1A, CMT2A, CMTX, and HNPP: Ultrasound in CMT and HNPP. Muscle Nerve 2013, 47, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, F.; Garz, C.; Heinze, H.; Petri, S.; Vielhaber, S.; Schreiber, S. Textural Markers of Ultrasonographic Nerve Alterations in amyotro phic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2020, 62, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, B.R.; Miller, R.G.; Swash, M.; Munsat, T.L. El Escorial Revisited: Revised Criteria for the Diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Mot. Neuron Disord. 2000, 1, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint Task Force of the EFNS and the PNS European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society Guideline on Management of Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy: Report of a Joint Task Force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society - First Revision. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2010, 15, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Østern, R.; Fagerheim, T.; Hjellnes, H.; Nygård, B.; Mellgren, S.I.; Nilssen, Ø. Diagnostic Laboratory Testing for Charcot Marie Tooth Disease (CMT): The Spectrum of Gene Defects in Norwegian Patients with CMT and Its Implications for Future Genetic Test Strategies. BMC Med. Genet. 2013, 14, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedarbaum, J.M.; Stambler, N.; Malta, E.; Fuller, C.; Hilt, D.; Thurmond, B.; Nakanishi, A. The ALSFRS-R: A Revised ALS Functional Rating Scale That Incorporates Assessments of Respiratory Function. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999, 169, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.C. A Modified Peripheral Neuropathy Scale: The Overall Neuropathy Limitations Scale. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shy, M.E.; Blake, J.; Krajewski, K.; Fuerst, D.R.; Laura, M.; Hahn, A.F.; Li, J.; Lewis, R.A.; Reilly, M. Reliability and Validity of the CMT Neuropathy Score as a Measure of Disability. Neurology 2005, 64, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleyweg, R.P.; Van Der Meché, F.G.A.; Schmitz, P.I.M. Interobserver Agreement in the Assessment of Muscle Strength and Functional Abilities in Guillain-Barré Syndrome: Muscle Strength Assessment in GBS. Muscle Nerve 1991, 14, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.P.; Kaur, S.; Arora, V. Reference Values for the Cross Sectional Area of Normal Tibial Nerve on High-Resolution Ultrasonography. J. Ultrason. 2022, 22, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, S.; Schreiber, F.; Peter, A.; Isler, E.; Dörner, M.; Heinze, H.; Petri, S.; Tempelmann, C.; Nestor, P.J.; Grimm, A.; et al. 7T MR Neurography-ultrasound Fusion for Peripheral Nerve Imaging. Muscle Nerve 2020, 61, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Imaging Institute—Mango. Available online: https://mangoviewer.com/userguide.html (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, R.; Liu, J.-B.; Hu, B.; Jiang, L.-X. Value of Superb Microvascular Imaging Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Compared with Color Doppler and Power Doppler. Medicine 2017, 96, e6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiber, H. Cerebrospinal Fluid - Physiology, Analysis and Interpretation of Protein Patterns for Diagnosis of Neurological Diseases. Mult. Scler. 1998, 4, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pasquale, A.; Morino, S.; Loreti, S.; Bucci, E.; Vanacore, N.; Antonini, G. Peripheral Nerve Ultrasound Changes in CIDP and Correlations with Nerve Conduction Velocity. Neurology 2015, 84, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, A.; Vittore, D.; Schubert, V.; Lipski, C.; Heiling, B.; Décard, B.F.; Axer, H. Ultrasound Pattern Sum Score, Homogeneity Score and Regional Nerve Enlargement Index for Differentiation of Demyelinating Inflammatory and Hereditary Neuropathies. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016, 127, 2618–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, L.; Liu, M. Reference Values for Lower Limb Nerve Ultrasound and Its Diagnostic Sensitivity. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 86, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padua, L.; Granata, G.; Sabatelli, M.; Inghilleri, M.; Lucchetta, M.; Luigetti, M.; Coraci, D.; Martinoli, C.; Briani, C. Heterogeneity of Root and Nerve Ultrasound Pattern in CIDP Patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 125, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, E.; Noto, Y.; Simon, N.G. Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Peripheral Neuropathy: Structure Meets Function in the Neuromuscular Clinic. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 86, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedee, H.S.; van der Pol, W.L.; van Asseldonk, J.-T.H.; Franssen, H.; Notermans, N.C.; Vrancken, A.J.F.E.; van Es, M.A.; Nikolakopoulos, S.; Visser, L.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Diagnostic Value of Sonography in Treatment-Naive Chronic Inflammatory Neuropathies. Neurology 2017, 88, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, M.S.; Passmore, L.V.; Yoon, J.-S.; Brown, M.E.; Caress, J.B.; Walker, F.O. Cross-Sectional Area Reference Values for Nerve Ultrasonography. Muscle Nerve 2008, 37, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seok, H.Y.; Jang, J.H.; Won, S.J.; Yoon, J.S.; Park, K.S.; Kim, B.-J. Cross-Sectional Area Reference Values of Nerves in the Lower Extremities Using Ultrasonography: Normal CSA of Lower Limb Nerves. Muscle Nerve 2014, 50, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qrimli, M.; Ebadi, H.; Breiner, A.; Siddiqui, H.; Alabdali, M.; Abraham, A.; Lovblom, L.E.; Perkins, B.A.; Bril, V. Reference Values for Ultrasonograpy of Peripheral Nerves: US in Healthy Volunteer Nerves. Muscle Nerve 2016, 53, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeuw, C.; Wijntjes, J.; Lassche, S.; Alfen, N. Nerve Ultrasound for Distinguishing Inflammatory Neuropathy from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Not Black and White. Muscle Nerve 2020, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härtig, F.; Ross, M.; Dammeier, N.M.; Fedtke, N.; Heiling, B.; Axer, H.; Décard, B.F.; Auffenberg, E.; Koch, M.; Rattay, T.W.; et al. Nerve Ultrasound Predicts Treatment Response in Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy—A Prospective Follow-Up. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerasnoudis, A.; Pitarokoili, K.; Gold, R.; Yoon, M.-S. Nerve Ultrasound and Electrophysiology for Therapy Monitoring in Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy: Monitoring Methods of Immune Therapy in CIDP. J. Neuroimaging 2015, 25, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, R.; Toyka, K.V. Immune-Mediated Components of Hereditary Demyelinating Neuropathies: Lessons from Animal Models and Patients. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).