Submitted:

03 June 2023

Posted:

05 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

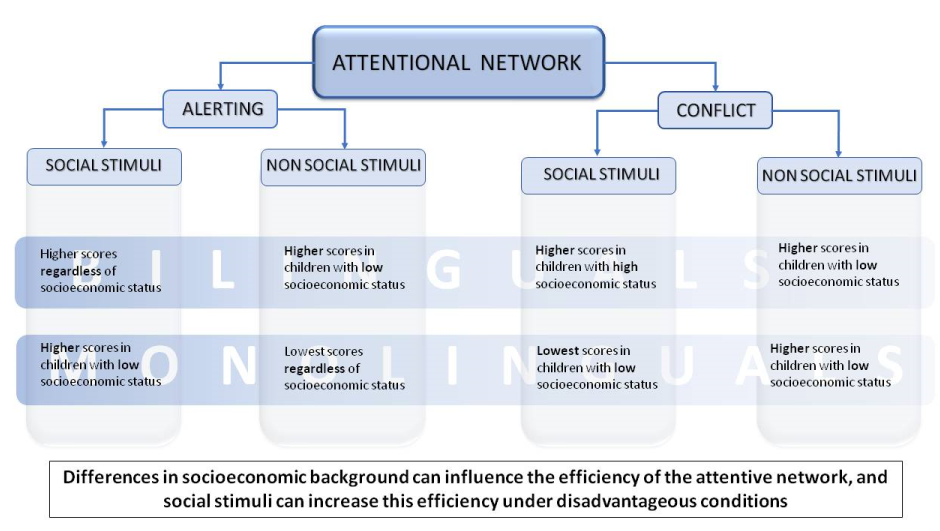

1.1. Bilingualism and the Attentional Network

1.2. Attentional Network and Socioeconomic Status

1.3. Study Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Participants’ Sociocultural and Language Characteristics

2.3.1. Parent Questionnaire

- -

- general information about the child and his/her family;

- -

- parents’ occupations and educational attainment;

- -

- parents’ countries of origin and years of residence in Italy;

- -

- languages spoken at home;

- -

- frequency of activities carried out with the child;

- -

- language proficiency in L1 and L2 (reserved for parents with fluency in a language other than Italian).

2.3.2. Assessment of IQ

2.3.3. Assessment of Language Abilities

2.3.4. Assessment of Working Memory

2.3.5. Assessment of Attentional Networks

2.4. ANT Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Linguistic Group and Socioeconomic Status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Barkley, R. A. , & Fischer, M. (2011). Predicting impairment in major life activities and occupational functioning in hyperactive children as adults: Self-reported executive function (EF) deficits versus EF tests. Developmental Neuropsychology, 36(2), 137–161. [CrossRef]

- Stern, S. , Kirst, C., & Bargmann, C. I. (2017). Neuromodulatory Control of Long-Term Behavioral Patterns and Individuality across Development. Cell, 171(7), 1649–1662.e10. [CrossRef]

- Tamm, L., Loren, R. E. A., Peugh, J., & Ciesielski, H. A. (2021). The association of executive functioning with academic, behavior, and social performance ratings in children with ADHD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 54(2), 124–138. [CrossRef]

- Hopfinger, J. B. , & Slotnick, S. D. (2020). Attentional control and executive function. Cognitive Neuroscience, 11(1-2), 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Fossum, I. N. , Andersen, P. N., Øie, M. G., & Skogli, E. W. (2021). Development of executive functioning from childhood to young adulthood in autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A 10-year longitudinal study. Neuropsychology, 35(8), 809–821. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C. T. , & Hinshaw, S. P. (2020). Executive functions in girls with and without childhood ADHD followed through emerging adulthood: Developmental trajectories. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 49(4), 509–523. [CrossRef]

- Øie, M. G. , Sundet, K., Haug, E., Zeiner, P., Klungsøyr, O., & Rund, B. R. (2021). Cognitive performance in early-onset schizophrenia and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A 25-year follow-up study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 606365. [CrossRef]

- Calabria, M. , Branzi, F., Marne, P., Hernández, M., & Costa, A. (2015). Age-related effects over bilingual language control and executive control. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 18(1), 65–78. [CrossRef]

- Morton, J. B. , & Harper, S. N. (2007). What did Simon say? Revisiting the bilingual advantage. Developmental Science, 10(6), 719–726. [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. , Craik, F. I., & Luk, G. (2012). Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(4), 240–250. [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. (2011). Reshaping the mind: The benefits of bilingualism. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology [Revue Canadienne de psychologie experimentale], 65(4), 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A. , & Martinot, C. Bilingualism and phonological awareness: The case of bilingual (French–Occitan) children. Reading and Writing, 23, 435–452 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Karbach, J. , & Kray, J. (2016). Executive functions. In: Strobach, T. & Karbach, J. (eds) Cognitive training. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, S. , Bialystok, E., Barac, R., Schellenberg, E. G., Cepeda, N. J., & Chau, T. (2011). Short-term music training enhances verbal intelligence and executive function. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1425–1433. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. , Hernández, M., & Sebastián-Gallés, N. (2008). Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: Evidence from the ANT task. Cognition, 106(1), 59–86. [CrossRef]

- Dash, S. , Shakyawar, S. K., Sharma, M. et al. (2019). Big data in healthcare: Management, analysis and future prospects. Journal of Big Data 6, 54. [CrossRef]

- Abutalebi, J., Della Rosa, P. A., Green, D. W., Hernandez, M., Scifo, P., Keim, R., Cappa, S. F., & Costa, A. (2012). Bilingualism tunes the anterior cingulate cortex for conflict monitoring. Cerebral Cortex, 22(9), 2076–2086. [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, G. , Goldsmith, S. F., Lupker, S. J., & Morton, J. B. (2022). Bilingualism and executive attention: Evidence from studies of proactive and reactive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 48(6), 906–927. [CrossRef]

- Antón, E. , Duñabeitia, J. A., Estévez, A., Hernández, J. A., Castillo, A., Fuentes, L. J., Davidson, D. J., & Carreiras, M. (2014). Is there a bilingual advantage in the ANT task? Evidence from children. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 398. [CrossRef]

- Morton, J. B. , & Harper, S. N. (2007). What did Simon say? Revisiting the bilingual advantage. Developmental Science, 10(6), 719–726. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, K. , Filippi, R., Periche-Tomas, E., Papageorgiou, A., & Bright, P. (2018). The importance of socioeconomic status as a modulator of the bilingual advantage in cognitive ability. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1818. [CrossRef]

- Grundy, J. G., Chung-Fat-Yim, A., Friesen, D. C., Mak, L., & Bialystok, E. (2017). Sequential congruency effects reveal differences in disengagement of attention for monolingual and bilingual young adults. Cognition, 163, 42–55. [CrossRef]

- Paap, K. R., Johnson, H. A., & Sawi, O. (2015). Bilingual advantages in executive functioning either do not exist or are restricted to very specific and undetermined circumstances. Cortex, 69, 265–278. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M. L. , Hagen, M. P., Lurie, L. A., Miles, Z. E., Sheridan, M. A., Meltzoff, A. N., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2020). Cognitive stimulation as a mechanism linking socioeconomic status with executive function: A longitudinal investigation. Child Development, 91(4), e762–e779. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S. M., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2008). Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Developmental Science, 11(2), 282–298. [CrossRef]

- Blom, E. , Küntay, A. C., Messer, M., Verhagen, J., & Leseman, P. (2014). The benefits of being bilingual: Working memory in bilingual Turkish-Dutch children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 128, 105–119. [CrossRef]

- Buac, M. , Gross, M., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2016). Predictors of processing-based task performance in bilingual and monolingual children. Journal of Communication Disorders, 62, 12–29. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, S. F. & Morton, J. B. (2018). Time to disengage from the bilingual advantage hypothesis. Cognition, 170, 328–329. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, S. F. , & Morton, J. B. (2018). Sequential congruency effects in monolingual and bilingual adults: A failure to replicate Grundy et al. (2017). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2476. [CrossRef]

- Orsolini, M. , Federico, F., Vecchione, M., Pinna, G., Capobianco, M., & Melogno, S. (2022). How is working memory related to reading comprehension in Italian monolingual and bilingual children? Brain Sciences, 13(1), 58. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Miller, C. A., Sanjeevan, T., van Hell, J. G., Weiss, D. J., & Mainela-Arnold, E. (2019). Bilingualism and attention in typically developing children and children with developmental language disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(11), 4105–4118. [CrossRef]

- Tran, C. D. , Arredondo, M. M., & Yoshida, H. (2015). Differential effects of bilingualism and culture on early attention: A longitudinal study in the U.S., Argentina, and Vietnam. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 795. [CrossRef]

- Buckner, J. C. , Mezzacappa, E., & Beardslee, W. R. (2003). Characteristics of resilient youths living in poverty: The role of self-regulatory processes. Development and Psychopathology, 15(1), 139–162. [CrossRef]

- Noble, K. G. Norman, M. F., & Farah, M. J. (2005). Neurocognitive correlates of socioeconomic status in kindergarten children. Developmental Science, 8(1), 74–87. [CrossRef]

- Conejero, Á. , & Rueda, M. R. (2018). Infant temperament and family socio-economic status in relation to the emergence of attention regulation. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 11232. [CrossRef]

- Mance, G. A. , Grant, K. E., Roberts, D., Carter, J., Turek, C., Adam, E., & Thorpe Jr, R. J. (2019). Environmental stress and socioeconomic status: Does parent and adolescent stress influence executive functioning in urban youth? Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 47(4), 279–294. [CrossRef]

- Mezzacappa, E. (2004). Alerting, orienting, and executive attention: Developmental properties and sociodemographic correlates in an epidemiological sample of young, urban children. Child Development, 75(5), 1373–1386. [CrossRef]

- Ladas, A. I. , Carroll, D. J., & Vivas, A. B. (2015). Attentional processes in low-socioeconomic status bilingual children: Are they modulated by the amount of bilingual experience? Child Development, 86(2), 557–578. [CrossRef]

- Chen, E. , Cohen, S., & Miller, G. E. (2010). How low socioeconomic status affects 2-year hormonal trajectories in children. Psychological Science, 21(1), 31–37. [CrossRef]

- DeCarlo Santiago, C. , Wadsworth, M. E., & Stump, J. (2011). Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(2), 218–230. [CrossRef]

- Garrett-Peters, P. T. , Mokrova, I., Vernon-Feagans, L., Willoughby, M., Pan, Y., & Family Life Project Key Investigators (2016). The role of household chaos in understanding relations between early poverty and children’s academic achievement. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 16–25. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. , Heron, J., Lewis, G., Araya, R., Wolke, D., & ALSPAC study team (2005). Negative self-schemas and the onset of depression in women: Longitudinal study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 186, 302–307. [CrossRef]

- Gullifer, J. W. , Chai, X. J., Whitford, V., Pivneva, I., Baum, S., Klein, D., & Titone, D. (2018). Bilingual experience and resting-state brain connectivity: Impacts of L2 age of acquisition and social diversity of language use on control networks. Neuropsychologia, 117,123–134. [CrossRef]

- Thieba, C. , Long, X., Dewey, D., & Lebel, C. (2019). Young children in different linguistic environments: A multimodal neuroimaging study of the inferior frontal gyrus. Brain and Cognition, 134, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L. M. , & Dunn, D. M. (2007). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Fourth Edition (PPVT-4) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, B. & Bilancia, G. (2006). Batterie per la Valutazione dell’Attenzione Uditiva e della Memoria di Lavoro Fonologica nell’Età Evolutiva (VAUMeLF).

- Wechsler, D. (2003). Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M. R. , Fan, J., McCandliss, B. D., Halparin, J. D., Gruber, D. B., Lercari, L. P., & Posner, M. I. (2004). Development of attentional networks in childhood. Neuropsychologia, 42(8), 1029–1040. [CrossRef]

- Federico, F. , Marotta, A., Adriani, T., Maccari, L., & Casagrande, M. (2013). Attention network test—The impact of social information on executive control, alerting and orienting. Acta Psychologica, 143(1), 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. , Ovtchinnikov, M., Comstock, J. M., McFarlane, S. A., & Khain, A. (2009). Ice formation in Arctic mixed-phase clouds: Insights from a 3-D cloud-resolving model with size-resolved aerosol and cloud microphysics. Journal of Geophysical Research. [CrossRef]

- Federico, F. , Marotta, A., Martella, D., & Casagrande, M. (2017), Development in attention functions and social processing: Evidence from the Attention Network Test. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 35, 169–185. [CrossRef]

- Federico, F. , Marotta, A., Orsolini, M., & Casagrande, M. (2021). Aging in cognitive control of social processing: evidence from the attention network test. Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition, Section B, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition, 28(1), 128–142. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J. , McCandliss, B. D., Sommer, T., Raz, A., & Posner, M. I. (2002). Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14(3), 340–347. [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J. F. , & Bialystok, E. (2013). Understanding the consequences of bilingualism for language processing and cognition. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25(5). [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, M. C. , & Marx, C. (2014). Inhibitory processes in visual perception: A bilingual advantage. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 126, 412–419. [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, M. , Soveri, A., Laine, A., Järvenpää, J., de Bruin, A., & Antfolk, J. (2018). Is bilingualism associated with enhanced executive functioning in adults? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 144(4), 394–425. [CrossRef]

- Monnier, C. , Boiché, J., Armandon, P., Baudoin, S., & Bellocchi, S. (2022). Is bilingualism associated with better working memory capacity? A meta-analysis. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(6), 2229–2255. [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. W. (2002). Working memory capacity as executive attention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(1), 19–23. [CrossRef]

- Kane, M. J. , Brown, L. H., McVay, J. C., Silvia, P. J., Myin-Germeys, I., & Kwapil, T. R. (2007). For whom the mind wanders, and when: An experience-sampling study of working memory and executive control in daily life. Psychological Science, 18(7), 614–621. [CrossRef]

- Kapa, L. L. & Colombo, J. (2013). Attentional control in early and later bilingual children. Cognitive Development, 28(3), 233–246. [CrossRef]

- Claes, N. , Smeding, A., & Carré, A. (2023). Socioeconomic status and social anxiety: Attentional control as a key missing variable? Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 36(4), 519–532. [CrossRef]

- Mogg, K. , Salum, G. A., Bradley, B. P., Gadelha, A., Pan, P., Alvarenga, P., Rohde, L. A., Pine, D. S., & Manfro, G. G. (2015). Attention network functioning in children with anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and non-clinical anxiety. Psychological Medicine, 45(12), 2633–2646. [CrossRef]

| Bilingual | Monolingual | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Raven’s Progressive Matrices | -0.13 | 0.86 | -0.16 | 0.88 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test | 94.09 | 14.56 | 96.2 | 14.88 |

| Digit span | 8.57 | 2.63 | 8.98 | 2.81 |

| Non-word repetition | -1.12 | 1.68 | -1.08 | 1.58 |

| Letter-number sequencing | 9.07 | 3.30 | 9.3 | 4.13 |

| Immediate narrative memory | 9.65 | 3.34 | 10.27 | 2.89 |

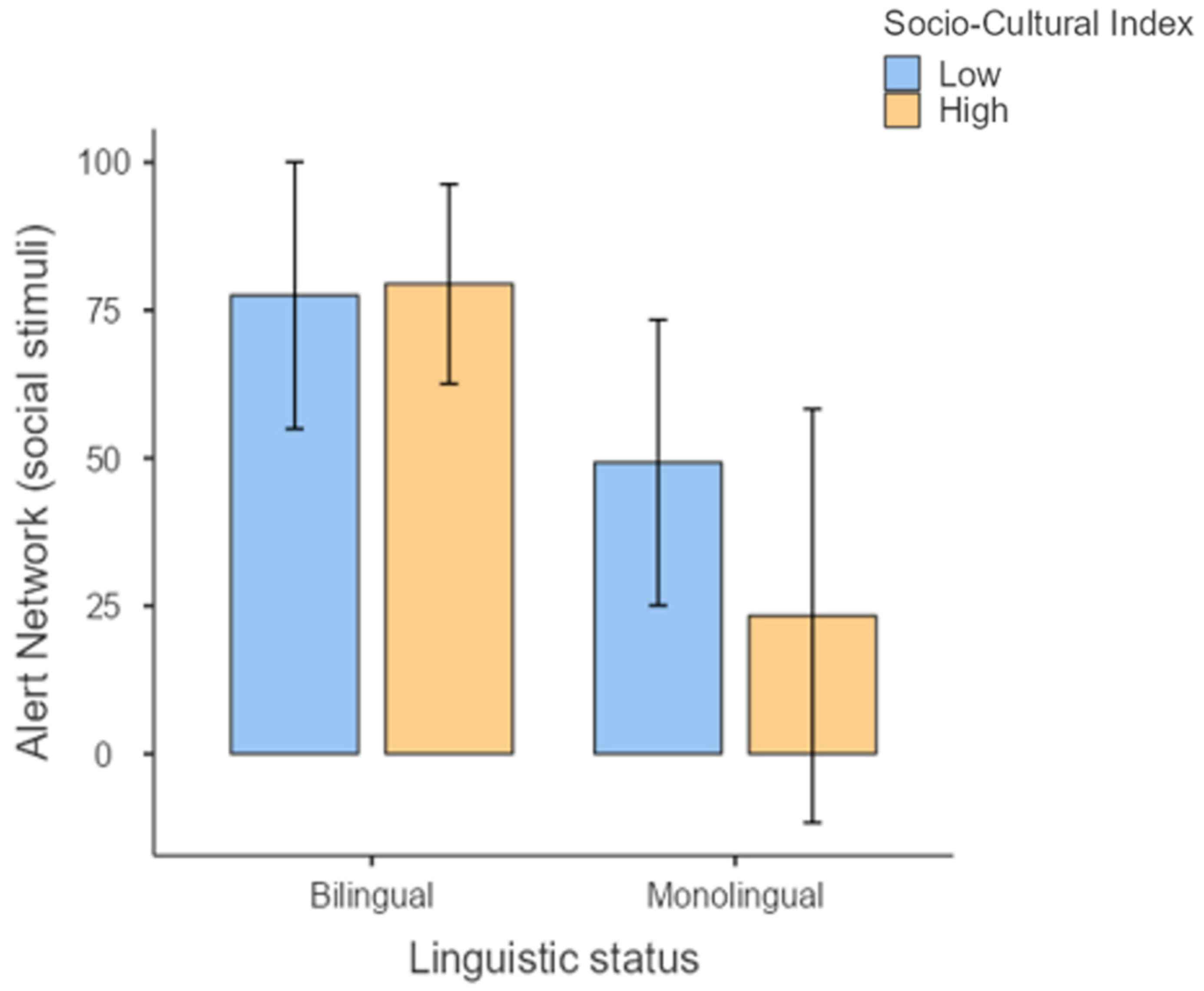

| Alerting photo (rt) | 78.81 | 115.74 | 32.38 | 191.92 |

| Orienting photo (rt) | 30.54 | 136.56 | 45.56 | 106.24 |

| Conflict photo (rt) | 102.62 | 161.17 | 28.80 | 210.97 |

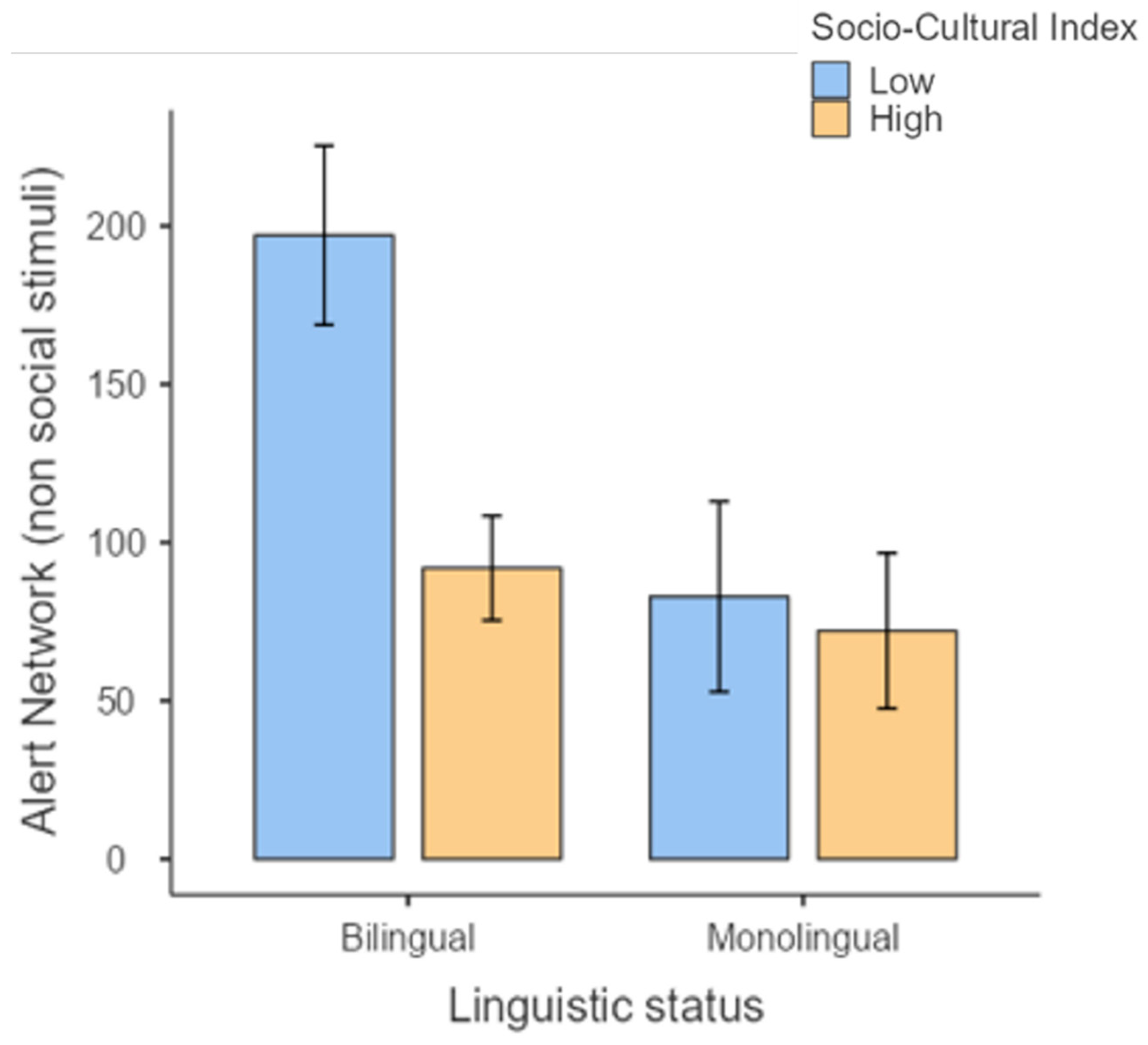

| Alerting fish (rt) | 126.03 | 132.86 | 75.90 | 150.73 |

| Orienting fish (rt) | 14.37 | 111.63 | 12.52 | 114.21 |

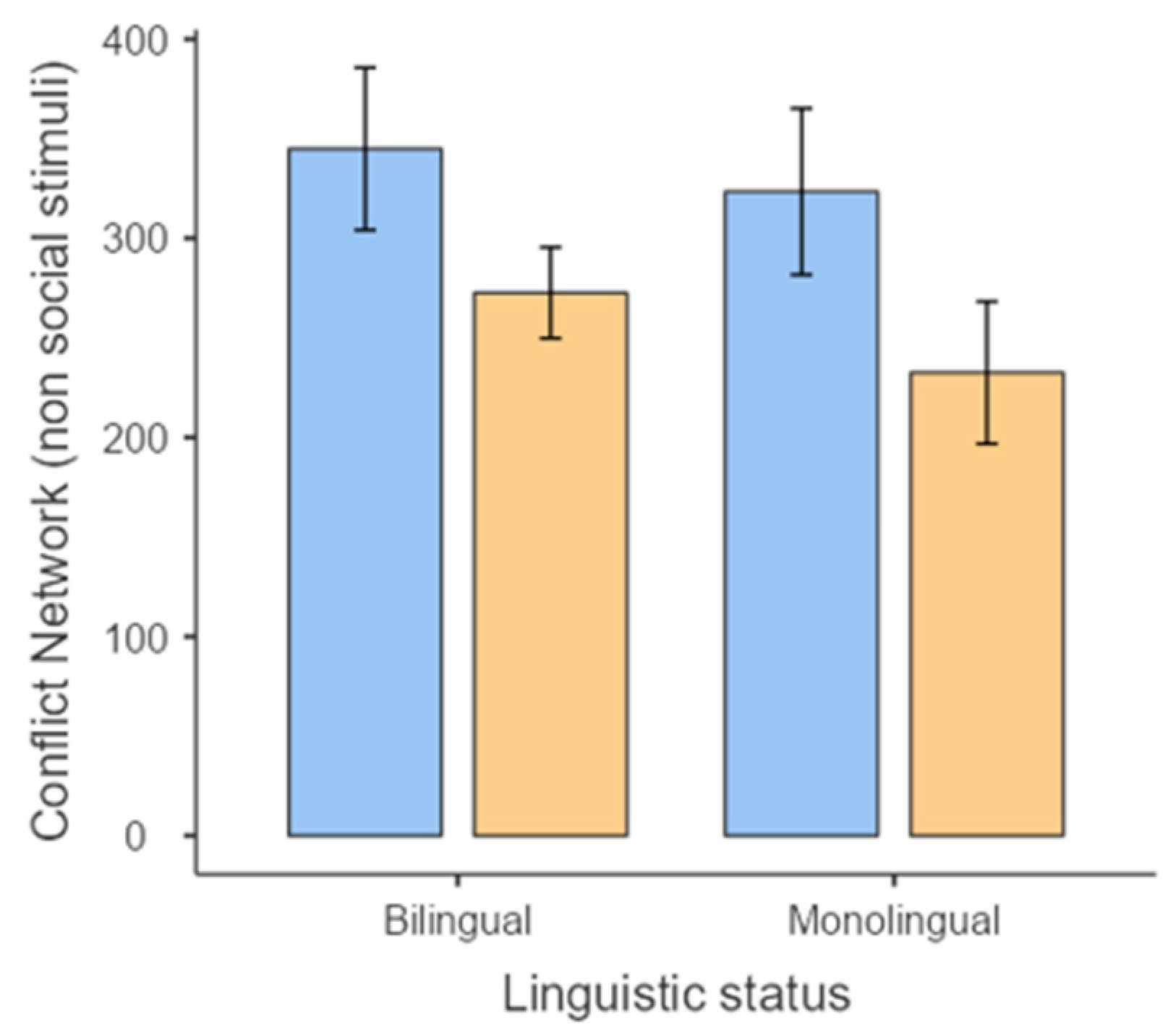

| Conflict fish (rt) | 296.09 | 176.59 | 264.28 | 220.50 |

| Low SES | High SES | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Raven’s Progressive Matrices | -0.31 | 0.89 | -0.06 | 0.85 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test | 94.09 | 14.56 | 96.2 | 14.88 |

| Digit span | 8.57 | 2.63 | 8.98 | 2.81 |

| Non-word repetition | -1.12 | 1.69 | -1.09 | 1.61 |

| Letter-number sequencing | 9.07 | 3.30 | 9.3 | 4.13 |

| Immediate narrative memory | 9.65 | 3.34 | 10.27 | 2.89 |

| Alerting photo | 63.98 | 111.51 | 54.16 | 175.51 |

| Orienting photo | 58.05 | 144.81 | 27.040 | 110.34 |

| Conflict photo | 6.49 | 176.11 | 100.11 | 187.90 |

| Alerting fish | 142.48 | 149.81 | 83.01 | 136.00 |

| Orienting fish | 20.83 | 110.49 | 9.82 | 113.80 |

| Conflict fish | 334.65 | 195.81 | 254.58 | 194.48 |

| Linguistic status | SES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | |

| Raven’s Progressive Matrices | 0.04 | 0.843 | 0 | 0.367 | 0.546 | 0.003 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test | 51.166 | 0 | 0.276 | 0.018 | 0.895 | 0 |

| Non-word repetition | 0.043 | 0.837 | 0 | 0.762 | 0.384 | 0.006 |

| Digit span | 0.043 | 0.837 | 0 | 0.079 | 0.779 | 0.001 |

| Letter-number sequencing | 0.783 | 0.378 | 0.006 | 0.231 | 0.632 | 0.002 |

| Immediate narrative memory | 1.744 | 0.189 | 0.013 | 1.235 | 0.268 | 0.009 |

| Alerting photo | 3.386 | 0.068 | 0.025 | 4.086 | 0.045 | 0.03 |

| Orienting photo | 0.436 | 0.51 | 0.003 | 1.633 | 0.204 | 0.012 |

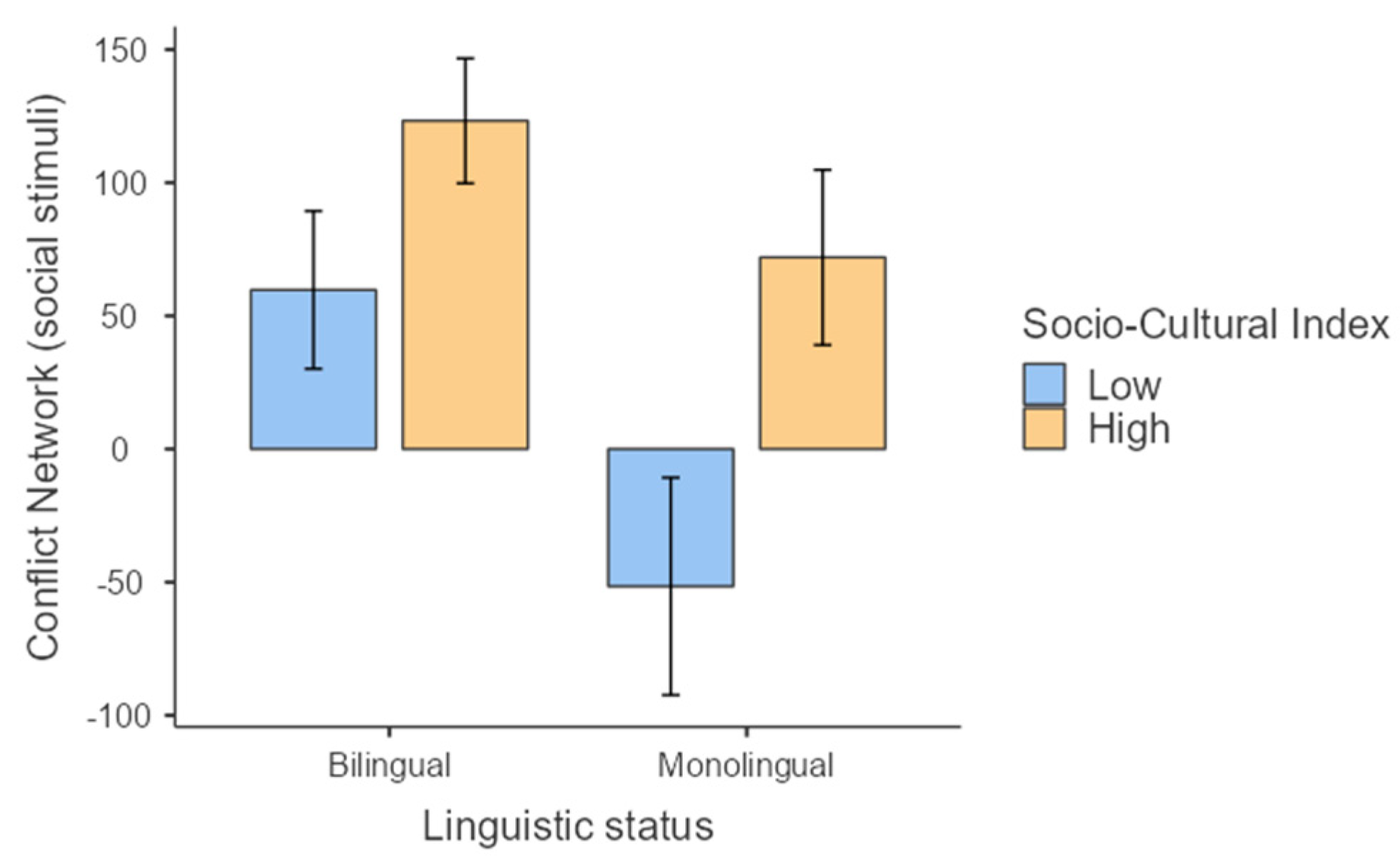

| Conflict photo | 5.194 | 0.024 | 0.037 | 13.756 | 0 | 0.093 |

| Alerting fish | 5.183 | 0.024 | 0.037 | 11.34 | 0.001 | 0.078 |

| Orienting fish | 0.018 | 0.893 | 0 | 1.013 | 0.316 | 0.008 |

| Conflict fish | 1.052 | 0.307 | 0.008 | 4.03 | 0.047 | 0.029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).