1. Introduction

Local programs and policies, such as local sustainability initiatives in general global practices(1) (2) (3) and cases in Japan as the Regional and Circular Ecological Sphere - Local Sustainable Development Goals (local SDGs) concept (4) and decarbonization initiative on the municipality scale (5), are crucial for creating sustainable societies. Local communities face local and global issues, including depopulation, declining birthrate, aging populations, declining local industries, increasing fragility of community bonds, landscapes and culture, climate change, and biodiversity loss. In the past, the public sector was responsible for addressing local societal issues(6), but this approach has limitations, particularly in resolving complex and uncertain issues that involve conflicting values(7). The public sector-driven policies and programs must be more comprehensive to resolve wicked problems(8). Therefore, there is a need for a new approach to local problem-solving that involves the private sector and other stakeholders. Co-creating value chains in a community-based approach with data and context-driven analysis may help to address these complex and uncertain issues and create more sustainable societies(9-11).

Although it is powerful to promote local initiatives, the diverse characteristics of different communities make it difficult to have a single and simple solution, and providing localizing solutions by involving stakeholders through a participatory approach is necessary (12, 13). Design thinking (14) is considered effective in cultivating creative processes by eliciting insights from stakeholders who use the locality concerned (15) (16). However, solving the issues faced requires input from appropriate public sector actors, companies, non-profit organizations, researchers, coordinators, and other parties capable of drawing up (17) (18). Public and private hybrid collaboration is indispensable, and co-creative approaches by various parties in both sectors are growing in importance (19) (20) (21). Multiple studies have pointed out the importance of implementing community co-creation in the field of urban planning (11), renewable energy(22), health service (23), organization (24), business (24, 25), digital community (26), consumer(27) and others. Despite the insights and experiences of these studies, practical frameworks and tools for analyzing co-creation value chains in community governance are still emerging, and further research is necessary.

Collective Impact (28) (CI) outlines the conditions necessary for the successful co-creation of wicked local problems and has influenced many fields (29) since its inception in 2011. The five conditions for collective success are a common agenda, shared measurement systems, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and a backbone organization (28). CI emphasizes the effectiveness of a collaborative process involving public and private sector actors, non-profit organizations, and residents, focusing on representing “a fundamentally different, more disciplined, and higher performing approach to achieving large-scale social impact” (p. 2). (30)

As Kania (2013) (30) indicates, effective shared measurement systems of large-scale social impact are crucial for public and private sector collaborations (31) because measured indicators and descriptions are unquestionably for participants. A Social impact assessment (SIA) is a practical methodology that identifies and measures the specific program's and policy's impact on stakeholders (32). This methodology considers short- and long-term outcomes and requires visualizing stakeholder interactions in a logic model(32). Design thinking is also a valuable tool in this context (33), as it can help to indicate the assessment improvement process. Existing literature on SIA and practice reports can offer valuable insights into measurement systems (34).

SIA can be subjective, making it challenging to select indicators with various methods (35-37). Logic models describes causal relationships between elements extracted from datasets and a community's knowledge (32). However, causal relationships are not appropriate due to being too simple and single to deal with integrative value chains in multiple policies and programs. Hence, a framework based on the Theory of Change (ToC) with systems thinking is needed to address this issue. ToC is a framework used to identify the causal relationships between indicators in SIA. At the same time, systems thinking is a tool for understanding the complexity of these relationships and their impact on the community.

One area for improvement is that it may not fully leverage the existing community power overlooking or undervaluing the strengths and assets already present in the community (38). It results in a lack of ownership and investment from community members without capacity building from the pyramid of the bottoms, leading to limited sustainability and impact (39). Another area is that individual indicators may have different dimensions, making it challenging to handle their relationship with a lack of integration between the different dimensions of sustainability(40). the logic model approach can, sometimes, extend capturing the complexity of community dynamics and the interrelationships between various factors contributing to social change in assets and resources in the community.

Incorporating the community capital, which contents to natural, financial, built, human, social, cultural, political, and digital capital(41), (42), perspective can help overcome these limitations by recognizing a community's strengths and weaknesses and leveraging assets and resources in a co-creative approach to social change. A comprehensive framework that integrates these concepts and methods is necessary to address the challenges of handling elements with the extract dimensions, individual policies and programs, and the value chains they create in a community-based approach. Such a framework ensures meaningful community engagement and effective co-creation initiatives that address the specific needs and contexts of the community, leading to sustainable social change.

There, the purpose of this paper is to propose a framework analyzing mechanisms of co-creation value chains in a community approach based on a narrative review of literature on CI, SIA and community capital on which a fair amount of previous research.

2. Collective impact and its relationship with other concepts

CI was proposed in 2011 as a new framework for stakeholders from various sectors to collaborate in addressing communities' wicked problems. As described earlier, Kania and Kramer (2011) defined collective impact as "the commitment of a group of important actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific social problem (28)." It is a framework for promoting community co-creation based on the five conditions :1) Common agenda, 2) Shared measurement systems, 3) Mutually reinforcing activities, 4) Continuous communication, and 5) Backbone organization. The empirical studies by Kania and Kramer (2011) (28). proposed this framework on the education refining initiative in the greater Cincinnati metropolitan area in the United States, mainly under the governance of Strive, a nonprofit organization. The participants included foundation heads, local government officials, school district representatives, community college presidents from several universities, and hundreds of nonprofit leaders. The initiative stakeholders were sustaining an alignment of collaborative types of efforts: funder collaboratives, public-private partnerships, multi-stakeholder initiatives, social sector networks, and CI initiatives (28).

Various initiatives after its proposal spontaneously led to a deeper discussion of its conditions and highlighted its pros and cons (29) (38), outlining the history in

Table 1. Cabaj and Weaver (2016) argued for the need to upgrade the design and implementation of the CI framework, proposing a shift to a movement-building leadership paradigm and updating the five conditions for CI success as Collective Impact 3.0 (38). Despite their criticism, they follow the fundamental propositions of the framework. Other studies have also identified weaknesses for improvement in its frameworks, such as the inadequate top-down approach of the common agenda, shared measurement system conditions, and the inability to accommodate policy or system change (43).

The CI framework has been the subject of ongoing debate and evolution, with scholars and practitioners arguing for revisions to ensure more significant equity and community participation. Ennis and Tofa's (2020) 's review research with 19 articles highlighted "a lack of analysis of the causes of social issues, and little critical thinking about the nature of "community" or "collaboration" as mechanisms through which to achieve large scale change. (29)" It indicates that understanding a community's status is crucial from a multi-dimension’s perspective, including economic, political, social, and other structures. The community Capital concept could support analyzing the mechanism of the community.

Kania et al. (2022) write that CI has never been a rigid framework that guarantees success but is instead an approach that must be adapted to the circumstances of each community and issue (44). They recommend placing equity at the center of CI efforts and offering five strategies (44) while maintaining the original five conditions. They improve the concepts to adapt to the unique circumstances of each community and issue. summarizes the evolution of the CI framework, with Kania and Kramer (2011)'s framework (28) serving as the base and complemented by the findings of Collective Impact 3.0 and Centering Equity in Collective Impact.

Centering Equity in Collective Impact (30) argues that solutions must be on both the analysis of objective data and an understanding of community context (44). This insight requires a deepening common understanding by closing the gap between objective data and subjective context and integrating the identification and assessment of community-scale value. Kania et al. (2022) suggest that appropriate data and context encourage a new and shared understanding of terminology, history, data, and personal stories (44). The SIA can be a candidate as the supporting methodology to measure it with quantitative and qualitative analysis developing unity between stakeholders from multiple aspects (45). In addition, the community capital concept helps identify the local communities' circumstances, referring to leveraging the resources and assets within a community for sustainable development(41), (42). Reviewing SIA and community capital research can enable issues to create a foundation of objective data and subjective context, unifying the dimensions of the local community and mapping the relationships between different elements.

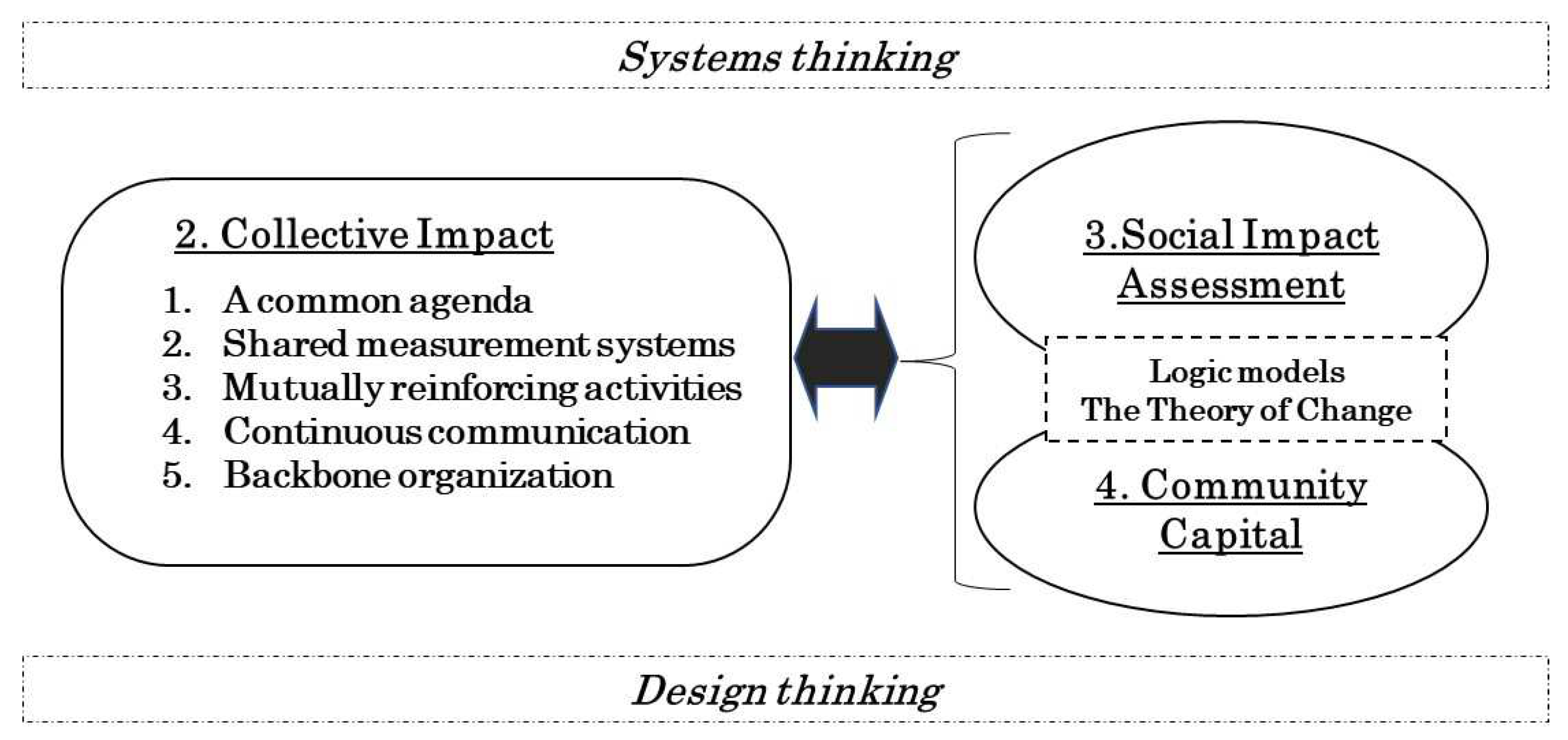

Figure 1 shows the structure of the remainder of this paper. And

Table 2 summarizes interpretation of the key terminologies in this paper. In this section, we have reviewed CI to organize expectations and issues and discussed the roles of SIA (including the ToC) and community capital. The following section will focus on each research field and explain findings for analyzing community co-creation value chain mechanisms.

3. The theory and practice of social impact assessment

3.1. The development of social impact assessment

SIA is part of the cost-benefit analyses in the academic field (48). It is a methodology used to determine whether to implement programs and policies based on estimating benefits versus cost. The New Public Management approach, adopted primarily in the UK, has driven the development of assessment methods to improve accountability, examining results and outcomes from the viewpoints of cost-effectiveness, efficiency, and efficacy (49).

SIA has been primarily developed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of public sector programs and policies but has since expanded to include private sector funds and subsidies. The United Nations and other countries governments and international organizations have utilized this methodology for programs and policies to assess the subsidies and the funds through donations and investments. As a result, there is an increasing development to quantitatively and qualitatively assess the benefits of programs and policies addressing social issues within local communities, in addition to short-term economic benefits, to allocate funds more effectively.

Epstein and Yuthas (2015) describes social impact as a change produced for stakeholders, including beneficiaries, as a result of project activities (50). The definition emphasizes the differences between the changes as the status quo before and after the intervention based on stakeholders' interests. Therefore, how to evaluate the changes encompasses assessment as a crucial component. Weiss (1984) defines evaluation as "the systematic assessment of program or policy implementation or outcomes against a set of explicit or implicit criteria as a means of contributing to their improvement." This definition provides a framework for conducting assessments, analyzing the data collected, and using the findings to improve programs or policies. Weiss's contributions can make SIA supported theoretically.

SIA has spread to more specific topics with practical tools. Epstein and Yuthas (2015) emphasize the importance of expanding the concept linked to social impact investment in policies and programs (50). They describe social investment as the capital used as input, including time, expertise, material assets, network connections, reputation, and other valuable resources (50). They examine methodologies to measure whether policies and programs earn assessments commensurate with social investment (50). Measurement approaches can be helpful for various purposes, including policy or program selection, monitoring during projects, evaluation of the project after completion, and overall assessment of organizational impact. The stakeholders can require identifying the most relevant social impact criteria.

3.2. Logic models and the Theory of Change

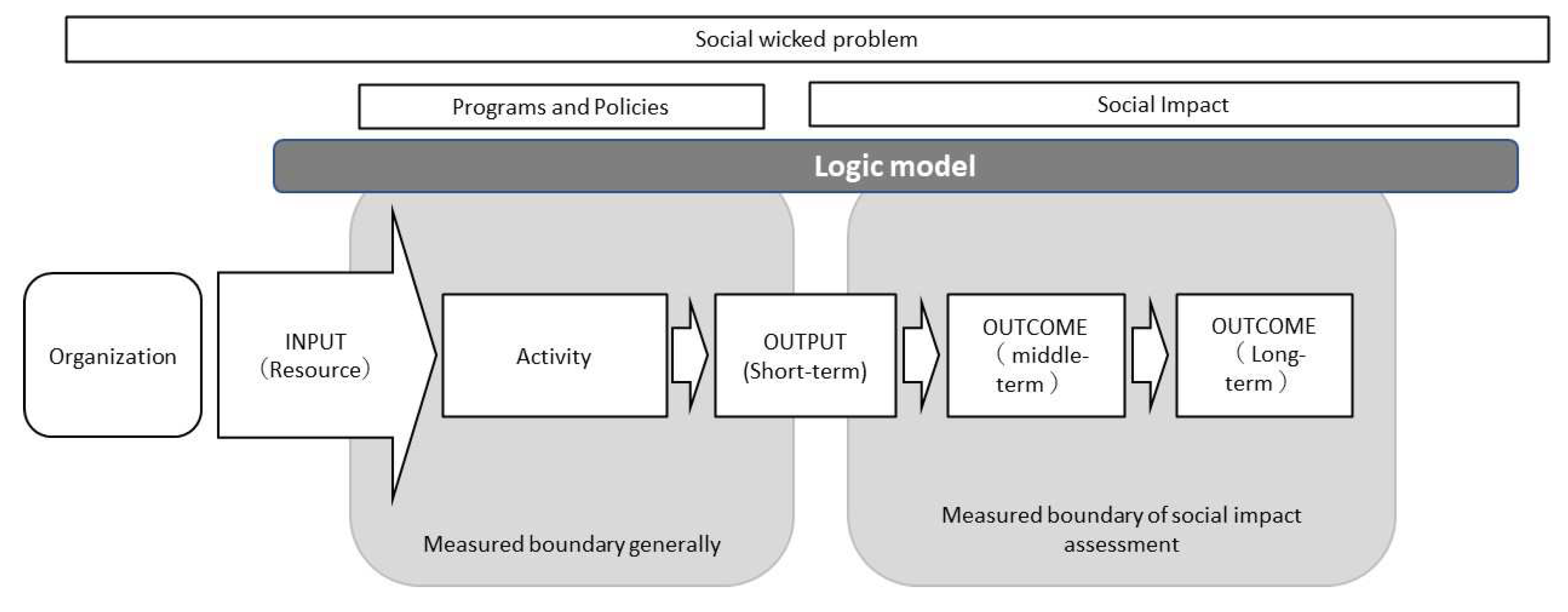

Creating a logic model is an indispensable part of SIA. Epstein and Yuthas (2015) define a logic model as "the logical sequence of activities and events through which the resources invested are transformed into desired social and environmental impacts " (50) Developing a logic model involves five steps: 1) Collect relevant information; 2) Clearly define the issue, including context resolution; 3) Define and tabulate the elements of the issue; 4) Construct a model that shows the issue's change theory; 5) Validate the logic of the issue and stakeholders. Logic models are becoming increasingly commonplace as visual tools that stakeholders find easy to understand.

The theoretical development of logic models themselves have started in the 1970s with the publication of Evaluation--promise and performance by Joseph S. Wholey (51) . Logic models were intended to be used to evaluate the performance of public sector investment and evolved in parallel with cost-benefit analysis. They are beneficial for enabling the flow of inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes to be organized in causal relationships in a way that enables the outcomes that stakeholders put the most value on to be allocated efficiently within limited resources and explained in the same flow as

Figure 3 shows.

Figure 3.

Basic flow of social impact assessment.

Figure 3.

Basic flow of social impact assessment.

The ToC complements these issues that serve as the bedrock of logic models (52) aligned with the system dynamics theory (52). Stroh (2015) asserts that systemic ToC is superior to linear ToC (pp.38) and emphasizes the importance of systems thinking (47). Using logic models in SIA is not two points from systems thinking perspective. One is that the assumption of causal relationships with flows between elements or indicators is not necessarily reasonable. Another is that the co-creating process needs governance because stakeholders include diverse individuals, companies, and organizations. Considering these limitations, incorporating systemic ToC features should result in a better methodology. Strategy 2 in Centering Equity in Collective Impact (focus on systems change, in addition to paradigms and services) is also effectively paying recognition to systems thinking(44).

Stroh (2015) defines system thinking as "the ability to understand these interconnections in such a way as to achieve a desired purpose. (47)" While experts tend to focus on linear causal relationships, social events are often nonlinear with time delays. This characteristic is why conventional solutions only sometimes result in an optimal system. Actions that are good for the system may not be continuous because they require time to take effect. System thinking is crucial for understanding how these situations can occur. Systems thinking is necessary for wicked problems to identify the cores of complex issues and draw feedback loop diagrams between structural points and elements (8). The assessment participants often overlook the interactions between elements, which makes achieving outcomes keep away. Leaders and problem-solving teams must build capacity in identifying leverage points and developing feedback loops between elements to create effective logic models.

Additionally, creating these flows and diagrams should involve dialogue and collaboration among stakeholders to deepen their understanding of systems thinking (53). This process builds the team's capacity to solve wicked problems and becomes a foundation for the co-creative resolution of social issues. Another critical aspect of understanding systems thinking is utilizing collective intelligence linked to design thinking. ToC based on systems thinking should balance people's need for complex insights to embrace their diverse perspectives with their needs.

ToC and logic models for SIA are mutual complements. ToC can provide a design to analyze the relationships between measured elements. In contrast, logic models can show the designed diagrams to produce a visual representation of a program or policy. To effectively understand the structures and mechanisms involved in the relationships between elements, the systems thinking, and logic model needs to organize the multiple design thinking-based elements in time series and other relationships, systematically elucidating and cultivating systems.

3.3. These concepts’ challenges

The SIA faces four main challenges. Firstly, it is challenging to measure monetary value in addressing the demands of financially invested stakeholders, who often require the conversion of sustainability indicators into monetary values, which may not be objectively and validly verifiable. Evidence-based policymaking in the public sector requires objective validity as a source of accountability for public funding, including participants of programs, policies, and taxpayers. However, indicators related to environmental and social aspects that are difficult to translate easily into monetary value pose a challenge. The contingent valuation method (CVM) helps estimate the social value to stakeholders, or alternative indicators are employed. Nevertheless, objectivity and validity remain critical issues. These issues highlight the need for careful consideration and attention to selecting indicators and valuation methods when evaluating programs and policies in a community.

Second, the SIA results often encounter issues, particularly concerning long-term outcomes' uncertainty. Social discount rates, used to determine the present value of future benefits, need to be set appropriately based on the opportunity cost. However, it is difficult to reflect it by the effective yield of government bonds with low long-term risk often used practically. Additionally, it is often difficult to determine whether an outcome results from the policy or program due to counterfactual and deadweight issues. Non-participating stakeholders or communities may also displace outcomes (displacement issues). Furthermore, when an outcome is affected by other organizations or factors, the degree to which the programs and policies concerned affect the outcome must be set (attribution issues). These methodological issues have been challenging still, impeding the more comprehensive practical application of logic models and causing problems after application.

The third issue of using logic models addresses their tendency to reflect the subjective of participants for assessment, who are part of stakeholders. The assessment methods apply to each policy or program with the participation of specific stakeholders, and logic differs depending on the social issue addressed, which makes comparisons between different policies or programs impossible. There is also the risk of logic model creation becoming a mere formality. Therefore, the participatory assessment method must standardize logic models partly and categorize elements' dimensions providing a systematic combination of key performance measurements.

Fourthly, once fixing a logic model, focusing too much on outcome measurement may result in overlooking real improvements. Lowe and Wilson (2017) contend that an outcome-based approach promotes the game of pursuing performance measurement at the expense of true improvements (54). More specifically that especially in social impact bonds or performance-linked private-sector outsourcing, the need for parties pursuing the programs and policies to pay attention to short-term rewards and penalties may hinder achieving long-term outcomes.

As an alternative, he advocates using outcome indicators to develop long-term partnerships for SDGs, well-being, and other such movements, constructing more comprehensive participatory, collaborative frameworks for governance (40). Awareness of the same issues undoubtedly led also to the formulation of the strategies set out in Centering Equity in Collective Impact, and there is clearly a growing need to consider SIA frameworks focused more on achieving long-term outcomes.

4. Concepts of Community Capital

4.1. Capitals in a community

The Inclusive Wealth Index (IWI) is an alternative index to GDP that measures a country's inclusive wealth, increasing the well-being of people, and has been applied to the municipality scale (55). It is based on the stocks and flows model that considers human, natural, and produced capital as stocks and consumption and investment of production and inclusive wealth operating profits as flows. It is a metric for measuring intergenerational well-being and feedback to capital as sustainability indicators. Additionally, other methods of measuring community circumstances include sustainability assessment, community Quality of Life, and local SDGs.

The International Integrated Reporting Framework for Companies (IIRC) provides an assessment method using the six capitals of financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural capital (56). This method is a corporate accounting; thus, evaluation emphasizes quantification and standardization. Companies have traditionally disclosed their financial capital to stakeholders through accounting. However, with the spreading adoption of Corporate Social Responsibility and now Environment, Social and Governance investment reporting, IIRC has been designed to report non-financial information on how the reporting company will be able to continue to create value over the medium to long term. Since corporate value is a quantitatively measurable index using models such as Olson's method (57), many empirical analyses have reported using these capitals as explanatory variables, revealing the effects of non-financial capital on corporate values (58).

Community development research in Japan started with Social Common Capital, (SCC) which refers to the shared resources and relationships in a society that contribute to social well-being, including trust, social networks, and civic engagement discussed by Uzawa (2005) (59). As this concept, a natural environment and social infrastructure capable of sustaining a community, living an economical life and enhancing an its culture. The emergence of case studies published applying the SCC concept in Japan on local industry, local production for local consumption, tourism, and other areas. These studies take their hint from concepts such as endogenous development and local autonomy that seek to rectify the bias of the central-regional structural dichotomy from a social capital perspective.

Table 3 summarizes the types of capital research based on the review. Each field focuses on specific stakeholders. CCF can divide into environment, economy, and society based on the triple-bottom-line approach, which can help analyze the relationship between community capital. SDGs or other global initiatives can play the role of help to understand the community capital concept to stakeholders (40, 60). Concerning this paper's target, CCF is an appropriate framework for adequately dealing with the community- or municipality-scale complemented by other concepts—comparing other three research concepts regarding capital highlights and their distinctive features. For instance, community and local development prioritize natural capital, whereas IWI and IIRC initially consider economic activities. Financial information is more crucial for stakeholders sharing stocks in the private sector, and non-financial information is reference capital related to future corporate value.

The scope is the communities' and stakeholders' concerned policies and programs; thus, this paper adapts CCF to propose a framework. Specific programs and policies involving urban and space developments, such as city center revitalization, construction of renewable energy facilities, waste management, and recycling facilities, can clarify CCF. That focus provides an opportunity to hold the promise of creating CI by measuring capital and analyzing the relationship between elements with the exact dimensions. The community at once refers to the administrative district where a policy or program is implemented, with the stakeholders of the different sectors. To this end, based on the descriptions provided by Nogueira and Ashton et al. (2019) (42) of the eight CCF capitals (48, 49), we will refer to overviews of those capitals.

4.2. Community Capital Framework

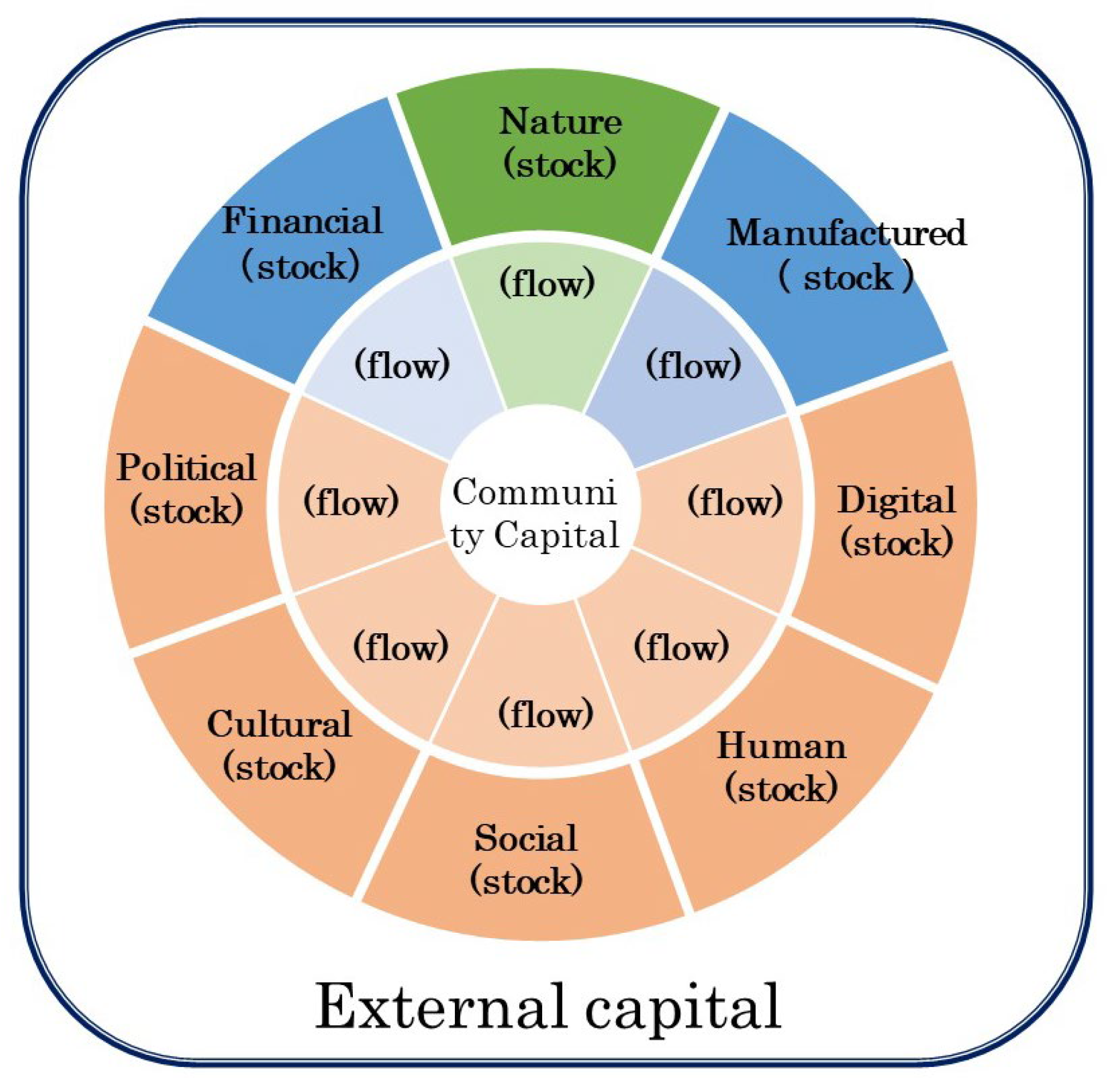

The section describes

community capital as a governance capability of each sector when resolving community issues with limited resources. It is a comprehensive framework combining tangible and intangible assets and resources within a community, including natural, financial, built, human, social, cultural, political, and digital dimensions. It leverages to address social problems and improve community well-being. These eight capitals form the basis for organizing dimensions and analyzing mechanisms for simply integrating value chains, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Eight types of capital and external capital.

Figure 2.

Eight types of capital and external capital.

The CCF allows for the explicit separation and description of the stocks and flows of each capital, enabling the analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the community and the potential for sustainable investment of community capital. Nogueira and Ashton et al. (2019) (42) used a question-based approach of "what" and "how" to uncover the perceptions of community stakeholders on stocks and flows. Additionally, we propose enabling the relationship between endogenous community capital and external capital.

Successfully implementing programs and policies requires the involvement of external stakeholders and their capital. The CI identifies five conditions for achieving this. The latter three conditions involve bringing together core stakeholders to provide a foundation for supporting policies and programs by promoting trust and collaboration among stakeholders within and outside the community effectively and sustainably.

Figure 2. defines community co-creation-based governance as aiming to create a spiral of a capital increase, accumulation, and reinvestment through the input of the community and external capital to achieve long-term outcomes aligned with the CI concepts leading stakeholders in the effort. During this process, a framework must also provide measuring and assessing community capital using SIA.

4.2.1. Natural capital

Natural capital is that natural resources, both renewable and nonrenewable including fauna and flora, as well as their life supporting systems(42).. Stakeholders can show perceptions measured through questions about its composition and functions in CCF (42).

Another research on natural capital has focused on methods using statistical indicators from a macroeconomic perspective. A leading example is research on IWI (55). Natural capital elements can devise into farmland capital, forest capital, and fishery capital. Parts of indicators can convert into a monetary value with indirect multifaceted functions such as CVM.

On the contract, the Natural Capital Protocol is a bottom-up approach to natural capital research emphasizing measurement and accountability for stakeholders in the corporate sector (61). It defines natural capital as renewable and nonrenewable natural resources that generate and provide benefits or services to society and companies. These benefits are ecosystem flows that contribute to the overall value of companies and society. However, a drawback of the Protocol is that it recognizes the inseparability of corporate and community/social activities as they are interconnected.

4.2.2. Financial capital

Financial capital is defined as a productive power in the resources of other types of capital. It includes the resources and assets of an individual or entity translated in the form of a currency that can be accessed, owned, or traded(42). Questions about the structures that enable credits and loans and the institutional structures defining value reveal the stakeholder's perceptions(42). In addition, inquiries, cash flow, and expenditures help understand the dynamics of financial capital for building community co-creation-based governance of policies and programs.

Financial capital is a concept developed in the corporate sector, and its definition is unambiguous. It refers to the pool of funds available to an organization to produce goods or provide services and obtained through financings, such as debt, equity, or grants, or generated through operations or investments. The IIRC recognizes the importance of financial capital (56), and the corporate sector has extensive financial accounting knowledge. In the public sector, financial capital is the funds available for providing public services and includes general and special accounts involving local taxes, national grants to municipalities, local government bonds, and other funds. The funds obtained through loans, stocks, donations, subsidies, grants, and other sources, or generated by business activities or investments, are also included in the definition of financial capital in policies led by the national government and foundations.

4.2.3. Manufactured capital

Manufactured capital is all material goods that includes human-made elements such as physical infrastructures, roads, artifacts, and machines (49). Stakeholder perceptions regarding the use of manufactured capital stocks and flows are uncovered by asking, for stocks, about the infrastructure available and its condition and the portfolio of offerings supporting activities; for flows, about how and where infrastructures are being used, and how and where products and services are being produced and consumed (49).

In statistics, manufactured capital refers, if applying the concept of the stock, to the real capital stock in industry and is estimated respectively for manufacturing and non-manufacturing sectors. Private sector capital stock, on which the Economic and Social Research Institute of the Cabinet Office reports statistics, is divided into tangible and intangible assets and reported accordingly.

In an OECD manual, the Cabinet Office defines public manufactured capital as the products provided by public institutions (general government and public corporations) in 18 key sectors (roads, ports, aviation, railways, public rental housing, sewerage, waste treatment, water supply, city parks, educational facilities, flood control, erosion control, coast, agriculture-forestry-fisheries, postal services, national forests, industrial water supply, government buildings) (62). It measures gross capital stock, net capital stock, and productive capital stock.

4.2.4. Social capital

Social capital is a professional and the social connections among actors. It includes partnerships and collaborations, as well as informal gatherings (49). Stakeholder perceptions regarding the use of social capital stocks and flows are uncovered by asking, for stocks, about the portfolio of organizations, the values exchange, and the structures promoting community engagement; for flows, about how and where partnerships and collaborations are being formed, and how and where events and activities supporting social gathering are happening.

At the same time, discussions on social capital are taking place in many fields. Woolcock (2010) reports that social capital achieves citations in a wide range of academic fields, including economics, political science, sociology, social psychology, business administration, education, and social epidemiology (public health) (63).. As Inaba (2015) points out, the value attributable to social capital, the measurement of social capital, and causal relationships with policy measures have made the concept the subject of considerable criticism. However, this paper employs the concept positively, not only because it represents the state of “community” within a particular community as stocks but serves as a basis for the utilization of external capital, as well as used to strengthen stock and its use as flows.

Social capital concerns are divided into research on networks between individuals and organizational governance in public-private partnerships. Tanaka (2021) (64), who applies a social capital approach with traditional research insights and analyzes their social capital from the perspectives of elements, discusses the former, type of connection, and place of accumulation based on Putnam (2000, 2002) (65) (66). Tanaka (2021) (64) introduces the concepts of bridging and bonding social capital and discusses relations within and outside a community. That paper proposes community autonomy, dependence, and utilization as three types of interaction and suggests that outsiders can have five effects on a community. Place of accumulation refers to how social capital can build up in the community to become a common asset shared by all. The networks, norms of reciprocity, and trust that specific stakeholders promoting a particular policy or program can bring to the community are vital in community co-creation.

It is also essential to accurately understand stakeholder relationships from the perspectives of connection and accumulation. The backbone organizations must pursue measures to unify internal stakeholders and serve as a bridge for outsiders to enter and participate in the community. By exploring these perspectives, it is possible to promote community co-creation and build social capital that benefits everyone.

4.2.5. Humanl capital

Human capital is the ability and capability of individuals to produce and manage their well-being. It includes individual health, knowledge, skills, and motivation (49). Stakeholder perceptions regarding the use of human capital stocks and flows are uncovered by asking, for stocks, about the institutional structures for knowledge creation and differentiation and the institutions maintaining the capacity of individuals to perform, and for flows, about how and where the engagements within these structures are happening, and how the capacity of individuals to perform is defined (49).

The concept of human capital spread extensively to education, human resources, and economic growth. Inclusive wealth theory is a practical candidate to account for human capital, which measures the increase in the present value of lifetime earnings that corresponds to earnings from education. Human capital is quantified by examining education levels and wage structures, with economic value serving as the objective variable.

From another approach, the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) distinguishes between human and intellectual capital to effectively govern the companies' capital(56). Intellectual capital refers to knowledge-based intangibles, such as intellectual property, procedures, protocols, systems, and tacit knowledge. In contrast, human capital refers to people's ability, experience, and willingness to innovate, including their alignment with an organization's governance framework and ethical values. Human capital also involves understanding, developing, and implementing an organization's strategy, as well as loyalties, motivations, and leadership skills.

The CCF framework focuses primarily on human capital but recognizes the importance of utilizing existing intellectual capital or creating new intellectual value. Human capital, including intellectual capital, is relevant to social capital, building up through learning, and can also strengthen through each other. Those relationships can unite people through capital and accumulate those in the community.

4.2.6. Cultural capital

Cultural capital is values and beliefs inherent in social practices or incorporated by communities. It also includes ethnicity, spirituality, heritage, traditions, and daily practices (49). Stakeholder perceptions regarding the use of cultural capital stocks and flows are uncovered by asking, for stocks, about traditions and cultural heritage and the values and beliefs that sustain them; for flows, about the ordinary practices and manifestations of the values and beliefs and how and where new global practices expose to individuals and organizations in the community (49).

Cultural capital is a concept proposed by Pierre Bourdieu (67) that refers to qualifications, abilities, and propensities acquired through long-term training and accumulating knowledge as a cultural value. Scott et al., (2018) (68) summarized that 'Cultural capital can be of three types: The first is 'embodied cultural capital as knowledge accumulated by individuals through socialization). The second is 'objectified cultural capital' as material property owned by individuals. The third is 'institutionalized cultural capital' as academic credentials or professional qualifications. Cultural capital is closely related to education, and research on cultural capital in that context continues today.

4.2.7. Political capital

Political capital is a structure in organizations that determines how decisions are made and power is distributed. It involves hierarchy, inclusion, equity, transparency, access, and participation" (49). Stakeholder perceptions regarding the use of political capital stocks and flows are uncovered by asking, for stocks, about the policies influencing decisions and the power structure; and for flows, about how and where policies are being driven, and how and where decisions are being made (49).

In a review of research on political capital, Schugurensky (2003) argues that political capital includes factors that promote citizenship education and participation in decision-making, as well as the capacity to influence public policy (69). The first factor is knowledge, ranging from general information to legislation and research-based knowledge. The second factor is political skills, including political literacy, understanding of legal documents, and critical analysis skills. The third factor is attitudes, such as self-esteem, motivation, endurance to accept defeat, interest in politics, and trust in the political system. The fourth factor is closeness to power, which refers to the distance between the citizen and political power. Finally, the fifth factor is personal resources, including the time and financial capital people can devote to influencing political decision-making. These factors interact with each other in different ways from context to context. While there are also other political capital factors, the above factors are the most important from the perspective of citizenship education and participation.

The concept of political capital is also related to political entrepreneurship. Policy entrepreneurs (70, 71) , who pursue policy innovations through non-traditional means and work with others in and around policymaking venues, have been identified as significant actors in achieving desired policy outcomes(72).. They exhibit high social acuity, ambition, and tenacity and work tirelessly to establish trust within specific policy circles. Although similar to social and human capital, policy entrepreneurs focus on introducing and implementing new ideas in a particular context. Recent theoretical and empirical research on policy entrepreneurs has highlighted the importance of framing problems, building teams, expanding networks, and working with advocacy coalitions. By expanding the concept of innovation from the corporate sector to public sector policymaking, the role of policy entrepreneurs can be better understood and clarified. This research indicates that policy entrepreneurs can play a crucial role in transforming society and can guide the community through knowledge, political skills, attitudes, closeness to power, and personal resources. Ultimately, policy entrepreneurs have the potential to drive positive change in society by promoting innovative policy solutions and building consensus around them(72).

4.2.8. Digital capital

Digital capital is a "digital infrastructure and data. It includes digital platforms, as well as the mechanisms of data collection, analysis, and storage" (49). Stakeholder perceptions regarding the use of digital capital stocks and flows are uncovered by asking, for stocks, about available digital infrastructures and mechanisms for data collection, and for flows, about how and where infrastructures are being used and data stored (49).

In defining digital capital, Ragnedda, M. (2018) (73) reviews the discourse, including Weber and Bourdieu, leading to cultural capital, highlighting its role as a bridge between online and offline life chances. Ragnedda, M. (2018) defines digital capital in the light of recent technological advances as "a set of internalized ability and aptitude' (digital competencies) as well as 'externalized resources' (digital technology) that can be historically accumulated and transferred from one arena to another. (73) " That goes on to argue that as it grows, this capital affects other forms of capital (economic, social, cultural, personal, and political) in the social sphere and discusses this impact.

Practically, research is increasingly reporting on both the theory and practice of concepts such as smart cities (74), Industry 4.0 (75),, and open innovation (76), and any discussion of digital capital needs to consider this research.

5. Discussion

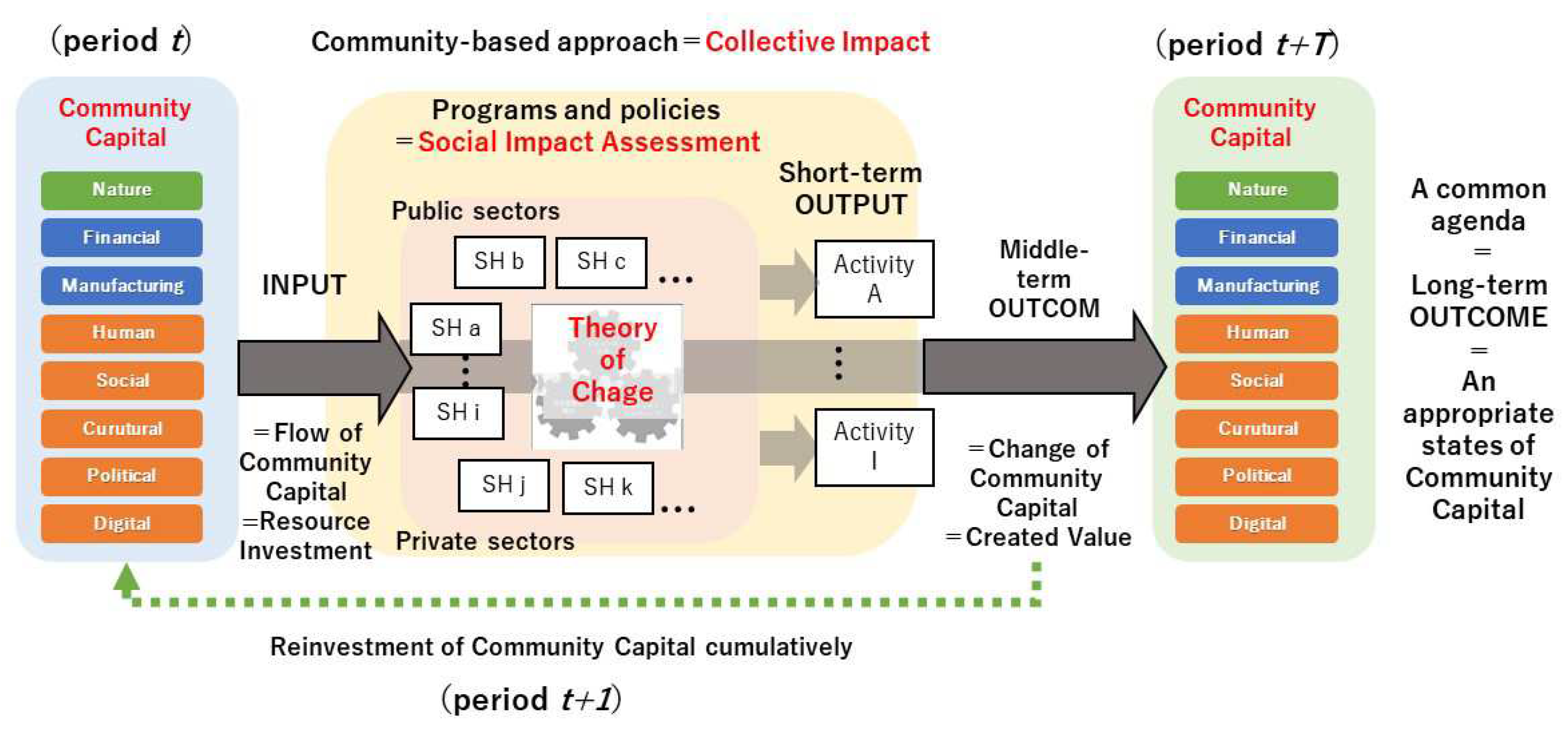

Co-creation is a collaborative process involving stakeholders in designing, implementing, and evaluating initiatives. Community-based approaches are crucial because they enable community members to have a say in decisions that affect them, and it helps ensure that initiatives and tailors to the specific needs and contexts of the community. Co-creation process integrating collective impact, SIA, and community capital can create value chains by bringing together stakeholders to work together. CI emphasizes the importance of collaboration between stakeholders and aligning their efforts toward a shared agenda. In contrast, SIA provides a framework for evaluating the effectiveness of initiatives in achieving their intended outcomes. Community capital is also crucial as it refers to a community's assets, resources, and networks and can provide leverage to support community-based initiatives driving sustainable social change. In terms of literature, there is a growing body of research on co-creation and its importance in community-based approaches. It emphasizes a community's collective assets and capabilities and the importance of collaboration and inclusive decision-making in leveraging these resources for positive outcomes.

Figure 4. proposes analyzing a co-creating a framework based on the previous reviews. The period t status of community capital reveals a specific community's situation. Public-private sectors engage together the various programs and policies with SIA. The input is the resource investment from the stock of community capital in period t as the flow of capital. Community stakeholders aim for a common agenda through dialogue and collaboration, and they are implementing activities toward engagement. The short-term output of each activity is measured and evaluated when the programs and policies for the (t+1) period. If the community capital changes and creates value

depending on this condition, it can be the medium-term outcome. Its outcome can be reinvested in the community, compounded, and increased cumulatively to accumulate community capital. Achieving a common agenda over T periods is a long-term outcome in the context of SIA and an appropriate status of community capital for sustainability.

Figure 4.

A framework analyzing co-creating.

Figure 4.

A framework analyzing co-creating.

Also, considering both community capital stocks and flows (46) enables the proposal of a model for inputting flows from the stocks represented by existing community capital into policies and programs according to circumstances. This model can describe long-term policies and programs for sharing between stakeholders. For example, bringing about social impacts will only be possible if community capital stock is high, indicating that priority should be put on first securing external capital or restoring community capital stocks. If, on the other hand, existing policies or programs are producing desirable outcomes, these outcomes affect the stock of community capital, creating a circular process that increases the flows that can be input. If this happens, community capital based on existing stock increases in value through policies and programs, enabling reinvestment of the increased amount in the next cycle. Introducing the community capital concept in this way enables the proposal of a framework for analyzing mechanisms for collectively generating social impacts and creating value chains.

This framework bringing these concepts together helps analyze mechanisms and governance of the co-creation value chains in a community-based approach. A point is the relationship between a common agenda of CI conditions and the long-term outcomes of SIA. The common agenda must be strongly supportive of various organizations, such as the public and private sectors in the community. When assessing the social impact of a specific programs and policy, participants set the long-term outcome as the common agenda. Each organization uses input and output flow of the community capital from the stocks of the community capital over a specific period and measures the outputs after implementation. Thus, the impact of outputs on outcomes needs to be measured, analyzed, evaluated, and visualized by assembling the ToC using a logic model with systems thinking. The second point is that a collaborative framework based on design thinking must also ensure outcomes consistent with the community context. By introducing CCF with the exact dimensions, balancing stakeholder subjectivity with analyzing objective measurement results is a significant challenge when considering value chains between elements. Lastly, we discuss the role of researchers. They need to play the dual roles of participant and expert and develop an understanding of the difficulties. They require participating as actors in the CI conditions of collective agenda, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and backbone organization. For shared measurement systems, on the other hand, researchers have a significant leadership role in reconciling objective assessments with the subjective perceptions of stakeholders. Since engineering, economics, and management assessment methods mainly ensure objectivity in a specific range, participatory assessment methods must be incorporated to ensure the collective subjective perceptions of stakeholders. In this respect, SIA methodology is critical, and the researcher can use community capital knowledge as an integrating dimension. They become participants in CI by committing to promote stakeholder autonomy.

However, due to the widespread and unquestioned co-creation by government agencies and foundations, several papers point out the crucial need to evaluate and scrutinize the approach more critically and thoughtfully. Wolff's (2016)'s ten questions on CI are crucial in discussing points making our framework more straightforward and more practitioner. The criticism for engaging those in the community most affected by the issues of Wolff's (2016) (43) is valid. Meaningful community engagement is crucial to successful community-based initiatives, and the co-creation process can address it. SIA help involves stakeholders, including community members. It provides a framework for designing, implementing, and evaluating the effectiveness of initiatives in achieving their intended outcomes. It can help ensure the community's needs and perspectives for decision-making. Community capital refers to a community's assets, resources, and networks and can provide leverage to support community-based initiatives, driving sustainable social change. By incorporating SIA and community capital, CI initiatives can involve a broader range of stakeholders, including those most affected by the issues, and create more equitable partnerships.

Another criticism is that CI does not include policy and system changes. ToC with SIAs can follow that point by the partnership's work for essential and intentional outcomes. ToC can help to identify the systemic changes needed to achieve the desired outcomes, and SIA can provide a framework for evaluating the effectiveness of initiatives in achieving their intended outcomes. By incorporating policy change and systems change as essential outcomes of CI initiatives, the partnership can work towards creating sustainable, long-term social change.

In our proposed framework, we have emphasized the importance of collaboration and stakeholder engagement in designing and implementing community-based initiatives. However, we acknowledge that our framework may have limitations, including the potential to overlook the critical role of the Backbone Organization in building leadership as Wolff's (2016) (43) and other papers.

The Backbone Organization is crucial in facilitating communication, coordinating efforts, and supporting stakeholders in achieving shared goals. It also must help to build leadership capacity within the community, enabling community members to take ownership of the initiatives and sustain them beyond the project's life. The role of the Backbone Organization in building leadership could be a critical issue, including strategies such as training and mentorship programs, networking opportunities, and capacity-building initiatives aimed at empowering community members to take on leadership roles within the project and beyond. Additionally, the role of community capital in building leadership within the community is also a challenging issue. By leveraging the community's assets, resources, and networks, we can support the development of community-based leadership capacity and promote sustainable social change.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have proposed a theoretical framework for analyzing community co-creation value chain mechanisms and using them in governance based on a literature review on SIA and community capital from the perspective of CI. Ten years have passed since framing the CI concept first, prompting research that has revealed the concept's issues and potential. We have discussed integrating CI with SIA based on data from systems thinking, practical knowledge from design-based thinking, and the merits of using community capital to measure community capability objectively. Both science-based engineering and economics methodologies and participatory community-based approaches help integrate data and community context; sharing knowledge among stakeholders helps help to sustain participation and prevent the framework from becoming a mere shell. By introducing the concept of community capital and organizing elements under a unified dimension, we could describe the possibilities for analyzing and sharing the subjective perceptions of stakeholders and objective paths of change.

However, although we have attempted to organize issues and integrate concepts with this narrative review, many of those concepts still need to be mature, creating various issues in establishing a framework based on them. The issues and potential of CI must apply to validate its practical implementation. Opinions differ among researchers on the flexibility of a framework based on data and community context from the perspective of universality—a framework incorporating flexibility needs to flourish theoretically and be refined by putting it into practice. We have only investigated CCF mainly of the idea, and we need to identify measurable, practical elements and describe them in unified dimensions. Analysis of the interplay between the different capitals, including trade-offs and integration with systems and design thinking, is another critical area of this research. Finally, the framework's success will depend on its validation through empirical studies and its adaptability to different community contexts.

Funding

This research is funded and supported by the Ministry of the Environment and Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency’s Environment Research and Technology Development Fund [JPMEERF20211002], [JPMEERF22S20900], [JPMEERF21S11904], including part of an inner grant-in-aid in the NIES Fukushima Regional Collaborative Research Center. We express our gratitude to all concerned.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pesch, U.; Spekkink, W.; Quist, J. Local sustainability initiatives: innovation and civic engagement in societal experiments. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 27, 300–317. [CrossRef]

- Moallemi, E.A.; Malekpour, S.; Hadjikakou, M.; Raven, R.; Szetey, K.; Ningrum, D.; Dhiaulhaq, A.; Bryan, B.A. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals Requires Transdisciplinary Innovation at the Local Scale. One Earth 2020, 3, 300–313. [CrossRef]

- Broto, V.C.; Trencher, G.; Iwaszuk, E.; Westman, L. Transformative capacity and local action for urban sustainability. Ambio 2019, 48, 449–462. [CrossRef]

- Marome, W.; Rodkul, P.; Mitra, B.K.; Dasgupta, R.; Kataoka, Y. Towards a more sustainable and resilient future: Applying the Regional Circulating and Ecological Sphere (R-CES) concept to Udon Thani City Region, Thailand. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2022, 14, 100225. [CrossRef]

- Kurachi Y, Morishima H, Kawata H, Shibata R, Bunya K, Moteki J. Challenges for Japan's Economy in the Decarbonization Process. Bank of Japan Research Paper Series, forthcoming. 2022.

- Brown K, Osborne SP. Managing change and innovation in public service organizations: Routledge; 2012.

- Osborne SP, Radnor Z, Strokosch K. Co-production and the co-creation of value in public services: a suitable case for treatment? Public management review. 2016;18(5):639-53. [CrossRef]

- Head BW, Alford J. Wicked problems: Implications for public policy and management. Administration & society. 2015;47(6):711-39. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, V.; Amaxilatis, D.; Mylonas, G.; Munoz, L. Empowering Citizens Toward the Co-Creation of Sustainable Cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 5, 668–676. [CrossRef]

- Leino, H.; Puumala, E. What can co-creation do for the citizens? Applying co-creation for the promotion of participation in cities. Environ. Plan. C: Politi- Space 2020, 39, 781–799. [CrossRef]

- Puerari, E.; De Koning, J.I.J.C.; Von Wirth, T.; Karré, P.M.; Mulder, I.J.; Loorbach, D.A. Co-Creation Dynamics in Urban Living Labs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1893. [CrossRef]

- Polèse M, Stren RE, Stren R. The social sustainability of cities: Diversity and the management of change: University of Toronto press; 2000.

- Reed, M.S.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Dougill, A.J. An adaptive learning process for developing and applying sustainability indicators with local communities. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 59, 406–418. [CrossRef]

- Brown T. Design thinking. Harvard business review. 2008;86(6):84.

- Brown, T.; Wyatt, J. Design Thinking for Social Innovation. Dev. Outreach 2010, 12, 29–43. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D. The circular economy, design thinking and education for sustainability. Local Econ. 2015, 30, 305–315. [CrossRef]

- Buhl, A.; Schmidt-Keilich, M.; Muster, V.; Blazejewski, S.; Schrader, U.; Harrach, C.; Schäfer, M.; Süßbauer, E. Design thinking for sustainability: Why and how design thinking can foster sustainability-oriented innovation development. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1248–1257. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.M.; McGann, M.; Blomkamp, E. When design meets power: design thinking, public sector innovation and the politics of policymaking. Policy Politi- 2020, 48, 111–130. [CrossRef]

- Andonova, L.B. Public-Private Partnerships for the Earth: Politics and Patterns of Hybrid Authority in the Multilateral System. Glob. Environ. Politi- 2010, 10, 25–53. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, N.D.; Roehrich, J.K.; George, G. Social Value Creation and Relational Coordination in Public-Private Collaborations. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 906–928. [CrossRef]

- Villani, E.; Greco, L.; Phillips, N. Understanding Value Creation in Public-Private Partnerships: A Comparative Case Study. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 876–905. [CrossRef]

- Sillak, S.; Borch, K.; Sperling, K. Assessing co-creation in strategic planning for urban energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 74, 101952. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Jackson, C.; Shaw, S.; Janamian, T. Achieving Research Impact Through Co-creation in Community-Based Health Services: Literature Review and Case Study. Milbank Q. 2016, 94, 392–429. [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation of value — towards an expanded paradigm of value creation. 2009, 26, 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Priharsari D, Abedin B, Mastio E. Value co-creation in firm sponsored online communities: what enables, constrains, and shapes value. Internet research. 2020;30(3):763-88. [CrossRef]

- Zwass V. Co-creation: Toward a taxonomy and an integrated research perspective. International journal of electronic commerce. 2010;15(1):11-48.

- Ind, N.; Coates, N.; Lerman, K. The gift of co-creation: what motivates customers to participate. J. Brand Manag. 2019, 27, 181–194. [CrossRef]

- Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact: FSG Beijing, China; 2011.

- Ennis, G.; Tofa, M. Collective Impact: A Review of the Peer-reviewed Research. Aust. Soc. Work. 2019, 73, 32–47. [CrossRef]

- Kania J, Kramer M. Embracing emergence: How collective impact addresses complexity. Stanford Social Innovation Review Stanford; 2013.

- Christens, B.D.; Inzeo, P.T. Widening the view: situating collective impact among frameworks for community-led change. Community Dev. 2015, 46, 420–435. [CrossRef]

- Esteves, A.M.; Franks, D.; Vanclay, F. Social impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 34–42. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin JA, Jordan GB. Using logic models. Handbook of practical program evaluation. 2015:62-87.

- Lisi, I.E. Determinants and Performance Effects of Social Performance Measurement Systems. J. Bus. Ethic- 2016, 152, 225–251. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Liu, P.; Mokasdar, A.; Hou, L. Additive manufacturing and its societal impact: a literature review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 67, 1191–1203. [CrossRef]

- Maas K, Liket K. Social impact measurement: Classification of methods. Environmental management accounting and supply chain management. 2011:171-202. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Alicea, R.J.; Fu, K. Systematic Map of the Social Impact Assessment Field. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4106. [CrossRef]

- Cabaj M, Weaver L. Collective impact 3.0: An evolving framework for community change. Tamarack Institute. 2016:1-14.

- Ansari, S.; Munir, K.; Gregg, T. Impact at the ‘Bottom of the Pyramid’: The Role of Social Capital in Capability Development and Community Empowerment. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 813–842. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.; Pearl, D.S. Rethinking sustainability frameworks in neighbourhood projects: a process-based approach. Build. Res. Inf. 2017, 46, 513–527. [CrossRef]

- Emery, M.; Flora, C. Spiraling-Up: Mapping Community Transformation with Community Capitals Framework. Community Dev. 2006, 37, 19–35. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.; Ashton, W.S.; Teixeira, C. Expanding perceptions of the circular economy through design: Eight capitals as innovation lenses. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 566–576. [CrossRef]

- Wolff T. Ten places where collective impact gets it wrong. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice. 2016;7(1):1-13.

- Kania J, Williams J, Schmitz P, Brady S, Kramer M, Juster JS. Centering equity in collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2022;20(1):38-45. [CrossRef]

- Becker H. Social impact assessment: method and experience in Europe, North America and the developing world: Routledge; 2014.

- Burdge RJ, Vanclay F. Social impact assessment. Environmental and social impact assessment. 1995:31-65.

- Stroh DP. Systems thinking for social change: A practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results: Chelsea Green Publishing; 2015.

- Burdge, R.J.; Vanclay, F. SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT: A CONTRIBUTION TO THE STATE OF THE ART SERIES. Impact Assess. 1996, 14, 59–86. [CrossRef]

- Barraket J, Keast R, Furneaux C. Social procurement and new public governance: Routledge; 2015.

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.R.; Yuthas, K. Managing Social, Environmental and Financial Performance Simultaneously. Long Range Plan. 2015, 48, 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Wholey JS. Evaluation: Promise and performance: Urban Institute Washington, DC; 1979.

- Forrester JW. System dynamics—a personal view of the first fifty years. System Dynamics Review: The Journal of the System Dynamics Society. 2007;23(2-3):345-58. [CrossRef]

- Ellinor L, Girard G. Dialogue: Rediscover the transforming power of conversation: Crossroad Press; 2023.

- Lowe, T.; Wilson, R. Playing the Game of Outcomes-based Performance Management. Is Gamesmanship Inevitable? Evidence from Theory and Practice. Soc. Policy Adm. 2015, 51, 981–1001. [CrossRef]

- Managi S, Kumar P. Inclusive wealth report 2018: Taylor & Francis; 2018.

- Council IIIR. International Framework [Available from: http://integrate-dreporting.org/resources/.

- Olson JE. Data quality: the accuracy dimension: Elsevier; 2003.

- Veltri, S.; Silvestri, A. The value relevance of corporate financial and nonfinancial information provided by the integrated report: A systematic review. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 3038–3054. [CrossRef]

- Uzawa H. Economic analysis of social common capital: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

- Izzo, M.F.; Strologo, A.D.; Granà, F. Learning from the Best: New Challenges and Trends in IR Reporters’ Disclosure and the Role of SDGs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5545. [CrossRef]

- Hein, L.; Bagstad, K.J.; Obst, C.; Edens, B.; Schenau, S.; Castillo, G.; Soulard, F.; Brown, C.; Driver, A.; Bordt, M.; et al. Progress in natural capital accounting for ecosystems. Science 2020, 367, 514–515. [CrossRef]

- Schreyer P, Pilat D. Measuring productivity. OECD Economic studies. 2001;33(2):127-70.

- Woolcock, M. The Rise and Routinization of Social Capital, 1988–2008. Annu. Rev. Politi- Sci. 2010, 13, 469–487. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka T. Sociology of nonresidential citizens - Regional Revitalization in an Era of Declining Population: Osaka University Press; 2021.

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community: Simon and schuster; 2000.

- Putnam RD. Democracies in flux: The evolution of social capital in contemporary society: Oxford University Press, USA; 2002.

- Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. The sociology of economic life: Routledge; 2018. p. 78-92.

- Davies, S.; Rizk, J. The Three Generations of Cultural Capital Research: A Narrative Review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2017, 88, 331–365. [CrossRef]

- Sheingate AD. Political entrepreneurship, institutional change, and American political development. Studies in American political development. 2003;17(2):185-203. [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M.; Norman, P. Policy Entrepreneurship and Policy Change. Policy Stud. J. 2009, 37, 649–667. [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M.; Maurya, D.; He, A.J. Policy entrepreneurship in Asia: the emerging research agenda. J. Asian Public Policy 2020, 13, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Petridou, E.; Mintrom, M. A Research Agenda for the Study of Policy Entrepreneurs. Policy Stud. J. 2020, 49, 943–967. [CrossRef]

- Ragnedda, M. Conceptualizing digital capital. Telematics Informatics 2018, 35, 2366–2375. [CrossRef]

- Camero, A.; Alba, E. Smart City and information technology: A review. Cities 2019, 93, 84–94. [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo M. Industry 4.0, digitization, and opportunities for sustainability. Journal of cleaner production. 2020;252:119869. [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi B, Ferraro G, Filippelli S, Galati F. The past, present and future of open innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management. 2020;24(4):1130-61. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).