Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

19 May 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

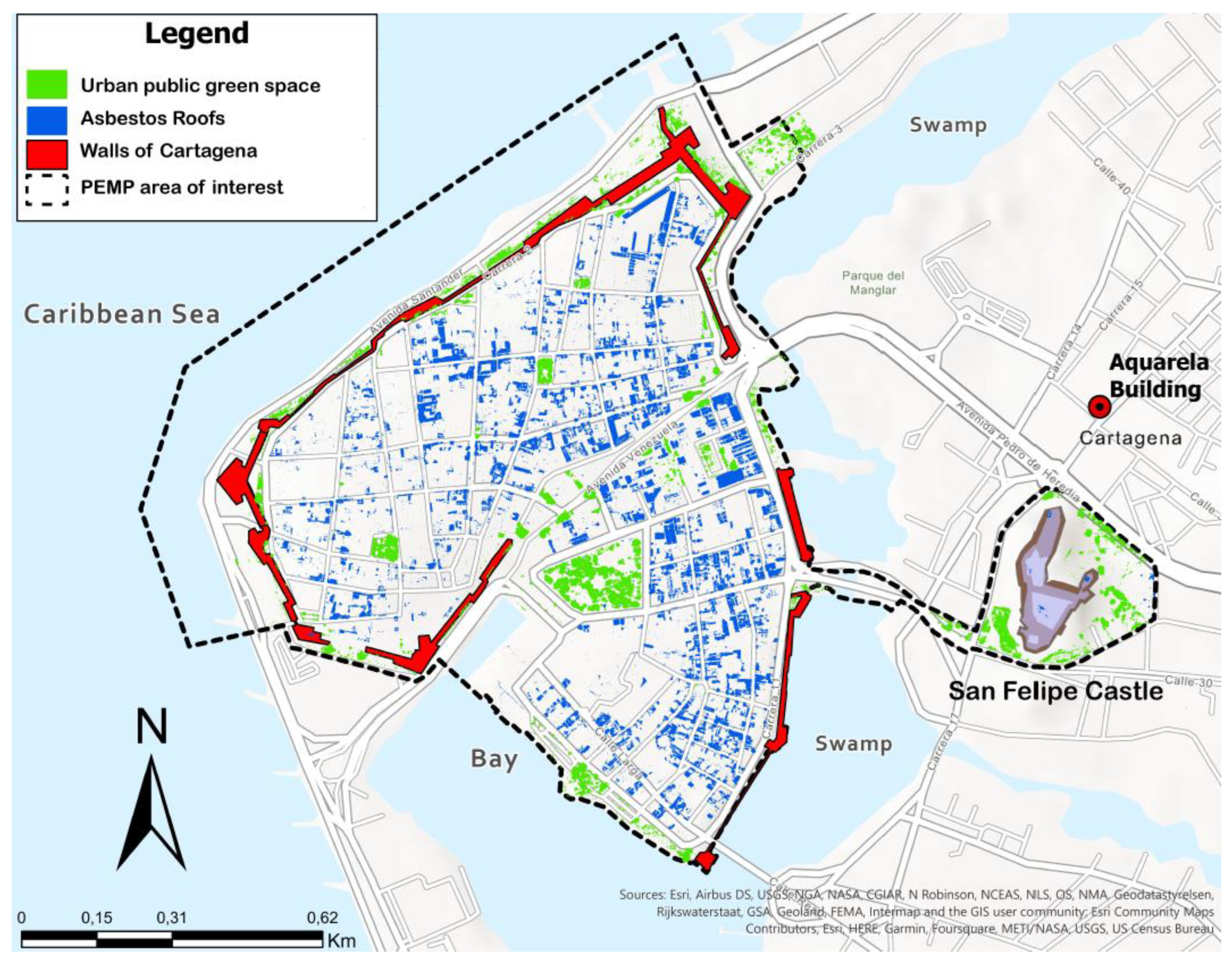

1.1. Case of study

1.2. Research aim

2. Materials and Methods

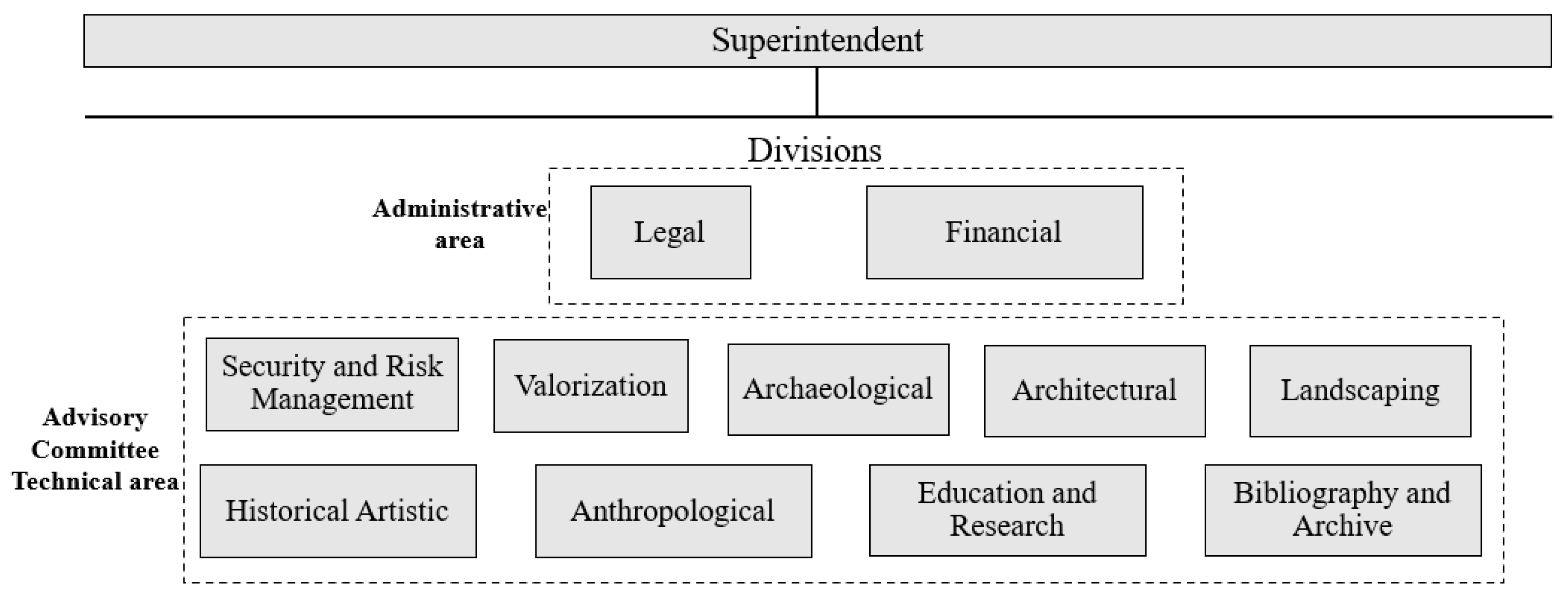

3. Cultural heritage management in Cartagena de Indias

3.1. Special Management and Protection Plan

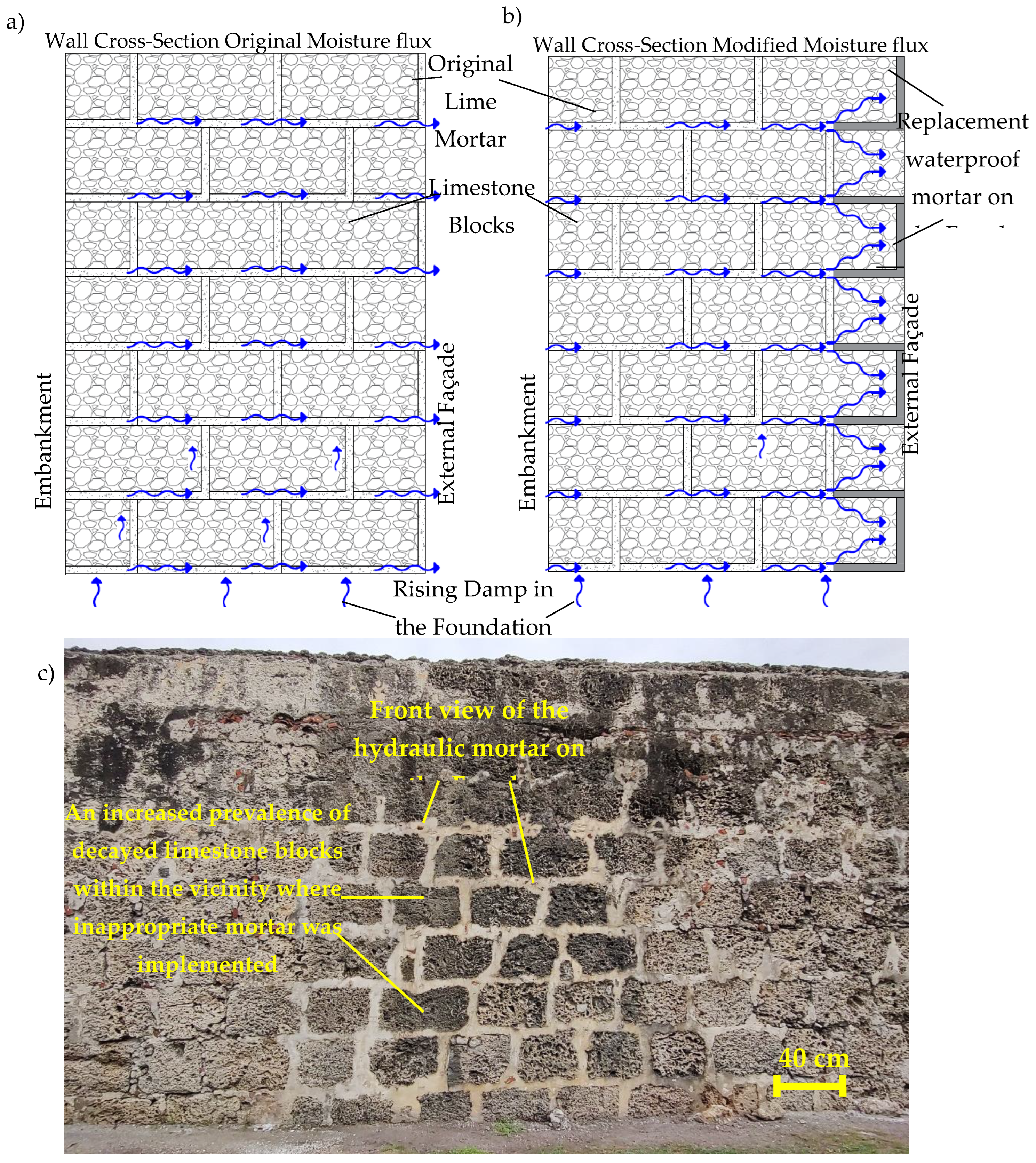

3.2. A critical review of the Cartagena’s material cultural heritage

3.2.1. Criticism of current heritage management

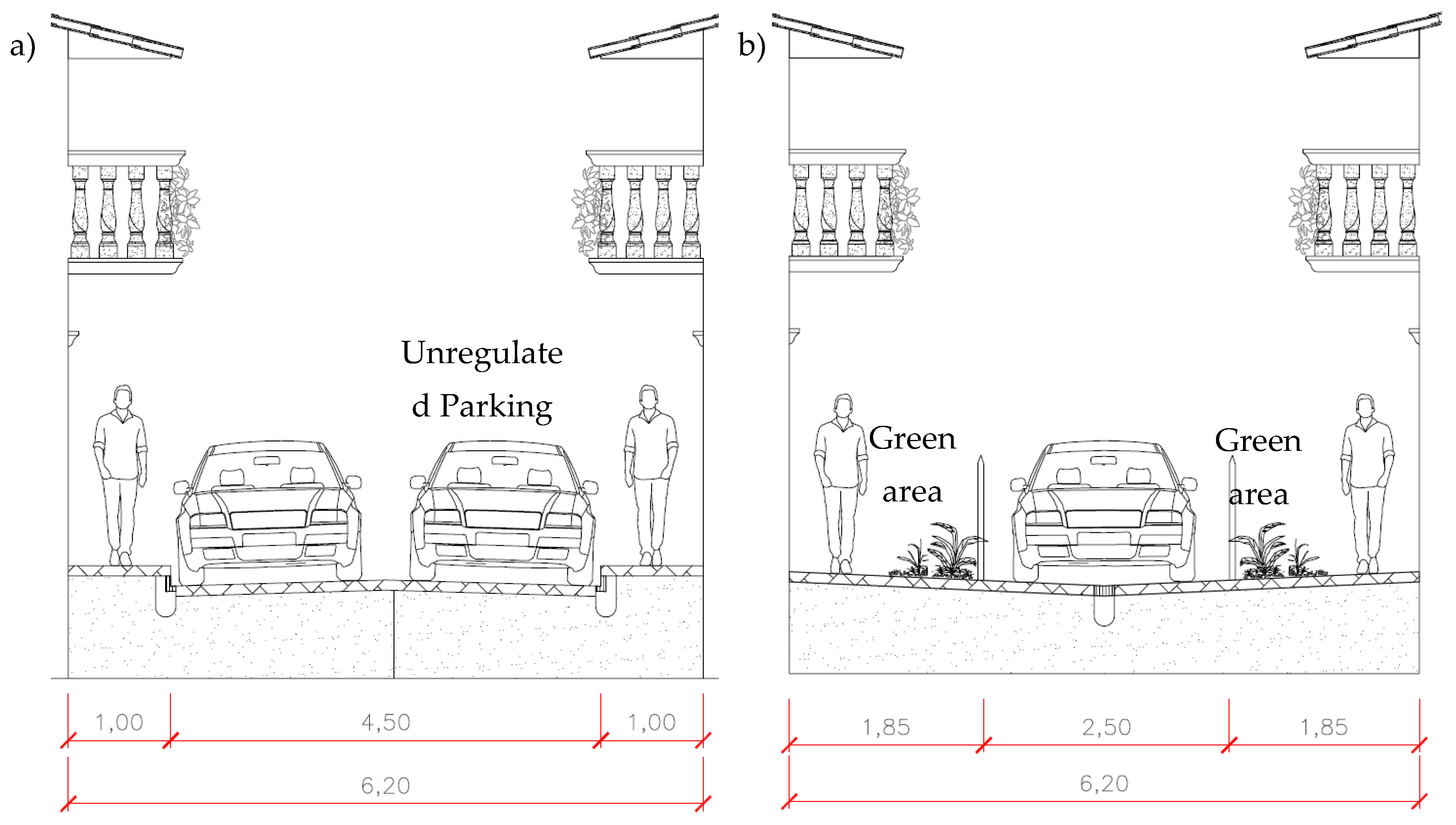

3.2.2. Ramifications of the contemporary heritage management practices

4. Recommendations to improve the cultural heritage in Cartagena.

4.1. Historical heritage management

- Verification and declaration of the cultural interest of real estate in the area.

- Cataloging of goods of cultural interest

- Inspection activity in the field of competence

- Authorization of building interventions in buildings or areas declared of cultural interest.

- Imposition of conservation interventions on cultural heritage

- Granting of contributions and facilitations for interventions for expenses caused by interventions for conservation and restoration of cultural heritage.

- Supervise the design and management of conservation interventions in tangible heritage.

- Concession for the use of cultural assets/concession of filming and audiovisual and photographic reproductions of cultural assets

- Carry out research on cultural heritage in order to know its current state and plan its ordinary and extraordinary maintenance.

4.2. General recommendations to mitigate existing problems

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Díaz-Andreu and A. Pastor Pérez, “Archaeological Heritage Values and Significance,” in Reference Module in Social Sciences, Elsevier, 2023.

- J. Otero, “Heritage Conservation Future: Where We Stand, Challenges Ahead, and a Paradigm Shift.,” Glob. challenges (Hoboken, NJ), vol. 6, no. 1, p. 2100084, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Rizzo and L. C. Herrero Prieto, “Economics and Archaeological Heritage,” in Reference Module in Social Sciences, Elsevier, 2023.

- D. Scarpi and F. Raggiotto, “A construal level view of contemporary heritage tourism,” Tour. Manag., vol. 94, p. 104648, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Park, B.-K. Choi, and T. J. Lee, “The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism,” Tour. Manag., vol. 74, pp. 99–109, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Yan, “Cultural Heritage Tourism: Five Steps for Success and Sustainability,” Tour. Manag., vol. 70, pp. 153–154, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. F. Castro, J. E. Becerra, R. Bellopede, P. Marini, and G. A. Dino, “Introduction to ‘natural stones and cultural heritage promotion and preservation,’” Resour. Policy, vol. 78, p. 102775, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen et al., “Investigation on the spatial and temporal patterns of coupling sustainable development posture and economic development in World Natural Heritage Sites: A case study of Jiuzhaigou, China,” Ecol. Indic., vol. 146, p. 109920, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Edensor, “Heritage assemblages, maintenance and futures: Stories of entanglement on Hampstead Heath, London,” J. Hist. Geogr., vol. 79, pp. 1–12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim, H. Kim, and K. M. Woosnam, “Collaborative governance and conflict management in cultural heritage-led regeneration projects: The case of urban Korea,” Habitat Int., vol. 134, p. 102767, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, B. Zhang, and H. Qiu, “How a hierarchical governance structure influences cultural heritage destination sustainability: A context of red tourism in China,” J. Hosp. Tour. Manag., vol. 50, pp. 421–432, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. J. van Lanen, R. van Beek, and M. C. Kosian, “A different view on (world) heritage. The need for multi-perspective data analyses in historical landscape studies: The example of Schokland (NL),” J. Cult. Herit., vol. 53, pp. 190–205, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, L. Zhao, Y. Chen, N. Zhang, H. Fan, and Z. Zhang, “3D LiDAR and multi-technology collaboration for preservation of built heritage in China: A review,” Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf., vol. 116, p. 103156, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Guerriero, M. Guadagnuolo, I. Titomanlio, and G. Faella, “An integrated approach for the conservation of archaeological buildings: The ‘Re Barbaro’ Palace in Sardinia,” Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit., vol. 27, p. e00244, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Lucchi, “Multidisciplinary risk-based analysis for supporting the decision making process on conservation, energy efficiency, and human comfort in museum buildings,” J. Cult. Herit., vol. 22, pp. 1079–1089, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Mekonnen, Z. Bires, and K. Berhanu, “Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia,” Herit. Sci., vol. 10, no. 1, p. 172, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Cao, S. Zhang, J. Zhao, and Y. Hong, “The Current Status, Problems and Integration of the Protection and Inheritance of China’s World Cultural Heritage in the Context of Digitalization,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2018, vol. 199, no. 2, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Durrant, A. N. Vadher, and J. Teller, “Disaster risk management and cultural heritage: The perceptions of European world heritage site managers on disaster risk management,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 89, p. 103625, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Carbone, L. Oosterbeek, C. Costa, and A. M. Ferreira, “Extending and adapting the concept of quality management for museums and cultural heritage attractions: A comparative study of southern European cultural heritage managers’ perceptions,” Tour. Manag. Perspect., 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, S. Krishnamurthy, A. Pereira Roders, and P. van Wesemael, “Community participation in cultural heritage management: A systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices,” Cities, vol. 96, p. 102476, 2020. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, “Site of Palmyra,” 2017. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/23/ (accessed Apr. 08, 2023).

- R. Temiño and A. Y. Vega, “Looting and Illicit Trafficking of Archaeological Heritage,” in Reference Module in Social Sciences, Elsevier, 2023.

- A. Al-Ansi, J.-S. Lee, B. King, and H. Han, “Stolen history: Community concern towards looting of cultural heritage and its tourism implications,” Tour. Manag., vol. 87, p. 104349, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Vu, “Demand reduction campaigns for the illegal wildlife trade in authoritarian Vietnam: Ungrounded environmentalism,” World Dev., vol. 164, p. 106150, 2023. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, “List of World Heritage in Danger,” 2023, 2023.

- UNESCO, “Conferencia intergubernamental de políticas culturales favorables al desarrollo.,” Estocolmo, 1998.

- A. J. Terán Bonilla, “Consideraciones que deben tenerse en cuenta para la restauración arquitectónica,” Conserva, pp. 101–122, 2004.

- M. Saba, J. L. Á. Carrascal, and A. R. C. Cruz, “Historical-architectural analysis of Cartagena de Indias heritage,” City, Territ. Archit., vol. 10, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. K. Torres Gil, D. Valdelamar Martínez, and M. Saba, “The Widespread Use of Remote Sensing in Asbestos, Vegetation, Oil and Gas, and Geology Applications,” Atmosphere (Basel)., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 172, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Han, X. Huang, H. Liang, S. Ma, and J. Gong, “Analysis of the relationships between environmental noise and urban morphology,” Environ. Pollut., vol. 233, pp. 755–763, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. A. G. Smyth, R. Wilson, P. Rooney, and K. L. Yates, “Extent, accuracy and repeatability of bare sand and vegetation cover in dunes mapped from aerial imagery is highly variable,” Aeolian Res., vol. 56, p. 100799, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Kokaly, D. G. Despain, R. N. Clark, and K. E. Livo, “Mapping vegetation in Yellowstone National Park using spectral feature analysis of AVIRIS data,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 84, no. 3, pp. 437–456, 2003. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Pedrali, N. Borges Júnior, R. S. Pereira, J. Tramontina, E. Alba, and J. Marchesan, “Multispectral remote sensing for determining dry severity levels of pointers in Eucalyptus spp.,” Sci. For., no. No.122, pp. 224–234, 2019.

- M. Tommasini, A. Bacciottini, and M. Gherardelli, “A QGIS Tool for Automatically Identifying Asbestos Roofing,” ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2019, Vol. 8, Page 131, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 131, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Frassy et al., “Mapping asbestos-cement roofing with hyperspectral remote sensing over a large mountain region of the Italian western alps,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 9, pp. 15900–15913, 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Paglietti, S. Malinconico, B. C. della Staffa, S. Bellagamba, and P. De Simone, “Classification and management of asbestos-containing waste: European legislation and the Italian experience,” Waste Manag., vol. 50, pp. 130–150, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Lorenz et al., “Remote sensing for risk mapping of Aedes aegypti infestations: Is this a practical task?,” Acta Trop., vol. 205, no. January, p. 105398, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Vinet and A. Zhedanov, “A ‘missing’ family of classical orthogonal polynomials,” El Univers., 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. Bonifazi, G. Capobianco, and S. Serranti, “Asbestos containing materials detection and classification by the use of hyperspectral imaging,” J. Hazard. Mater., 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Frassy, G. Dalla Via, P. Maianti, A. Marchesi, F. R. Nodari, and M. Gianinetto, “Minimum noise fraction transform for improving the classification of airborne hyperspectral data: Two case studies,” Work. Hyperspectral Image Signal Process. Evol. Remote Sens., vol. 2013-June, no. June, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Industria Comercio y Turismo de Colombia, “Informe mencual del turismo _ Diciembre 2022 - Enero 2023,” Bogota, Colombia, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.mincit.gov.co/getattachment/estudios-economicos/estadisticas-e-informes/informes-de-turismo/2022/diciembre/oee-yv-turismo-diciembre-2-03-2023.pdf.aspx.

- D. M. O. of C. de Indias, “Special Management and Protection Plan for the historic center of Cartagena (PEMP CH, for its initials in Spanish),” Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://pemp.cartagena.gov.co/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&layout=edit&id=147.

- ICOMOS, “Final ICOMOS Advisory mission report in Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena (Colombia) from 12-15 December 2017,” Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://whc.unesco.org/document/168091.

- UNESCO, “43COM 7B.99 - Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena (Colombia) (C 285),” Bakú, Azerbaiyán, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/7551.

- UNESCO, “44COM 7B.167 - Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena (Colombia) (C 285),” Paris, France, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/7883.

- Semana, “La triste historia del caballo que murió en una calle de Cartagena,” 12-05-2015, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, p. 1, May 12, 2015.

- El Espectador, “Carruajes en Cartagena, cuestionados tras muerte de caballos,” 10-09-2014, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, p. 1, Sep. 10, 2014.

- Opinión Caribe, “Se acerca demolición de la torre ‘Aquarela’ en Cartagena,” 2020, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, p. 1, 2020.

- N. Sezavar, M. Pazhouhanfar, R. P. Van Dongen, and P. Grahn, “The importance of designing the spatial distribution and density of vegetation in urban parks for increased experience of safety,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 403, p. 136768, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Diener and P. Mudu, “How can vegetation protect us from air pollution? A critical review on green spaces’ mitigation abilities for air-borne particles from a public health perspective - with implications for urban planning,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 796, p. 148605, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Mueller, J. Milner, M. Loh, S. Vardoulakis, and P. Wilkinson, “Exposure to urban greenspace and pathways to respiratory health: An exploratory systematic review,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 829, p. 154447, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- WHO, “Asbestos,” Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/ipcs/assessment/public_health/asbestos/en/.

- M. Peña-Castro, M. Montero-Acosta, and M. Saba, “A critical review of asbestos concentrations in water and air, according to exposure sources,” Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 5, p. e15730, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- Corporación Turismo Cartagena de Indias, “Retos y Realiadades: El sector turísctico en Cartagena de Indias,” Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 2015. [Online]. Available: https://observatorio.epacartagena.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/sector-turistico-de-cartagena.pdf.

- MitCIT, “Boletin Mensual Turismo Febrero de 2023 - Ministerio de Comercio Industria y Turismo,” Bogotà, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.mincit.gov.co/getattachment/estudios-economicos/estadisticas-e-informes/informes-de-turismo/2023/febrero/oee-yv-turismo-febrero-24-04-2023.pdf.aspx.

- M. Saba, J. Lizarazo-Marriaga, N. Hernandez-Romero, and E. Quiñones-Bolaños, “Physico-mechanical characterization of the limestone used in Cartagena walls and a proposal for their restoration process.,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 214, pp. 420–429, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Saba, J. M. Lizarazo-Marriaga, and E. Quiñones-Bolaños, “Overstress analysis of the Cartagena de Indias walls under different scenarios of masonry mechanical strength,” Case Stud. Constr. Mater., vol. 13, p. e00410, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Saba, N. Hernandez-Romero, E. Quiñones-Bolaños, and J. Lizarazo-Marriaga, “Petrographic of Limestone Cultural Heritage as the Basis of a Methodology to Rock Replacement and Masonry Assessment: Cartagena de Indias Case of Study,” Case Stud. Constr. Mater., 2019.

- M. Saba, E. Quiñones-Bolaños, and F. Martínez-Batista, “Impact of environmental factors on the deterioration of the Wall of Cartagena de Indias (In press, Corrected Proof),” J. Cult. Herit., 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Saba, E. Quiñones-Bolaños, and F. Martínez-Batista, “Impact of environmental factors on the deterioration of the Wall of Cartagena de Indias (In press, Corrected Proof),” J. Cult. Herit., 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Saba, N. Hernandez-Romero, E. Quiñones-Bolaños, and J. Lizarazo-Marriaga, “Petrographic of Limestone Cultural Heritage as the Basis of a Methodology to Rock Replacement and Masonry Assessment: Cartagena de Indias Case of Study,” Case Stud. Constr. Mater., 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. (J. H. F.. Bloemers, H. Kars, A. van der Valk, and M. Wijnen, Eds., The Cultural Landscape & Heritage Paradox. Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

- F. Farrelly, F. Kock, and A. Josiassen, “Cultural heritage authenticity: A producer view,” Ann. Tour. Res., vol. 79, p. 102770, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Shen and H. Chen, “Cultural Heritage Management in China: Current Practices and Problems,” in Cultural Heritage Management: A Global Perspective, P. M. Messenger and G. S. Smith, Eds. University Press of Florida, 2010, pp. 70–81.

- Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte de España, “Instituto del Patrimonio Cultural de España,” 2023. https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/cultura/patrimonio/informacion-general/gestion-en-el-ministerio/instituto-del-patrimonio-cultural-de-espana.html (accessed Apr. 08, 2023).

- Official Gazette of the Italian Republic, “Artícle 32: Superintendencies of Archaeology, fine arts and landscape,” Roma, Italy, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2019/08/07/184/sg/pdf.

- K. Leyendecker and P. Cox, “Cycle campaigning for a just city,” Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect., vol. 15, p. 100678, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Kutty, T. G. Wakjira, M. Kucukvar, G. M. Abdella, and N. C. Onat, “Urban resilience and livability performance of European smart cities: A novel machine learning approach,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 378, p. 134203, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Dhingra, M. K. Singh, and S. Chattopadhyay, “Macro level characterization of Historic Urban Landscape: Case study of Alwar walled city,” City, Cult. Soc., vol. 9, pp. 39–53, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Sgura Viana and J. P. M. Delgado, “City Logistics in historic centers: Multi-Criteria Evaluation in GIS for city of Salvador (Bahia – Brazil),” Case Stud. Transp. Policy, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 772–780, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Alimi, A. T. Oyeyinka, and L. O. Olohungbebe, “Socio-economic characteristics and willingness of consumers to pay for the safety of fura de nunu in Ilorin, Nigeria,” Qual. Assur. Saf. Crop. Foods, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 81–86, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, G. Zhang, and X. Zhang, “Urban street foods in Shijiazhuang city, China: Current status, safety practices and risk mitigating strategies,” Food Control, vol. 41, pp. 212–218, 2014. [CrossRef]

- I. Proietti, C. Frazzoli, and A. Mantovani, “Identification and management of toxicological hazards of street foods in developing countries,” Food Chem. Toxicol., vol. 63, pp. 143–152, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Badrie, A. Gobin, S. Dookeran, and R. Duncan, “Consumer awareness and perception to food safety hazards in Trinidad, West Indies,” Food Control, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 370–377, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Prague Morning, “As of January 2023, Prague Will Ban ‘Cruel’ Horse-Drawn Carriages,” 20-12-2021, Prague, Czech Republic, p. 1, Dec. 20, 2021.

- People for the Ethical Tratment of Animals (PETA), “Palma City Council Signs Off on Horse Carriage Ban, Will Replace Animals With Electric Vehicles,” 2023. https://www.peta.org/features/horse-drawn-carriage-bans/ (accessed Apr. 19, 2023).

- The New York City Council, Operation of horse drawn carriages and to replace the horse drawn carriage industry with a horseless electric carriage program. United States of America, 2022, p. 1.

- N. Rovella et al., “The environmental impact of air pollution on the built heritage of historic Cairo (Egypt),” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 764, p. 142905, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. L. S. Oliveira, A. Neckel, D. Pinto, L. S. Maculan, M. R. D. Zanchett, and L. F. O. Silva, “Air pollutants and their degradation of a historic building in the largest metropolitan area in Latin America,” Chemosphere, vol. 277, p. 130286, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Spagnuolo, C. Vetromile, A. Masiello, M. F. Alberghina, S. Schiavone, and C. Lubritto, “Climate and Cultural Heritage: The Case Study of ‘Real Sito di Carditello,’” Herit. 2019, Vol. 2, Pages 2053-2066, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 2053–2066, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Vidal, R. Vicente, and J. Mendes Silva, “Review of environmental and air pollution impacts on built heritage: 10 questions on corrosion and soiling effects for urban intervention,” J. Cult. Herit., vol. 37, pp. 273–295, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Rêgo and J. Almeida, “A framework to analyse conflicts between residents and tourists: The case of a historic neighbourhood in Lisbon, Portugal,” Land use policy, vol. 114, p. 105938, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Fortich, “Parques urbanos y recreación: un inventario en Cartagena,” Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 2003. Accessed: May 06, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306013197_Parques_urbanos_y_recreacion_un_inventario_en_Cartagena.

- R. Blanco-Bello and K. Victoria-Cogollo, “Los espacios públicos en sectores populares de Cartagena: lugares de encuentro y desencuentro,” Entramado, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 176–190, 2013.

- L. P. Thives, E. Ghisi, J. J. Thives Júnior, and A. S. Vieira, “Is asbestos still a problem in the world? A current review.,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 319, p. 115716, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. De Kock, J. Dewanckele, M. Boone, G. De Schutter, P. Jacobs, and V. Cnudde, “Replacement stones for Lede stone in Belgian historical monuments,” Geol. Soc. London, Spec. Publ., vol. 391, no. 1, pp. 31–46, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. De Kock et al., “Replacement stones for Lede stone in Belgian historical monuments,” Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ., vol. 391, no. 2011, pp. 31–46, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Caracol Cartagena, “Prostitución está alejando turismo familiar en centro de Cartagena,” Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, p. 1, Sep. 07, 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).