The following section presents a systematic account of the existing TCH governance framework in Cartagena, elucidating the involved stakeholders, their respective roles, and responsibilities. An exclusive segment addresses overarching challenges, while suggestions for potential management reorganization based on successful models employed in other nations are proffered. Additionally, twelve significant factors negatively impacting Cartagena's TCH are identified and deliberated upon. While offering general recommendations to alleviate prevailing issues, it is acknowledged that each problem necessitates a tailored approach, thorough study, and bespoke solutions as deemed appropriate by the authors.

3.1. Current Cultural Heritage Governance in Cartagena de Indias

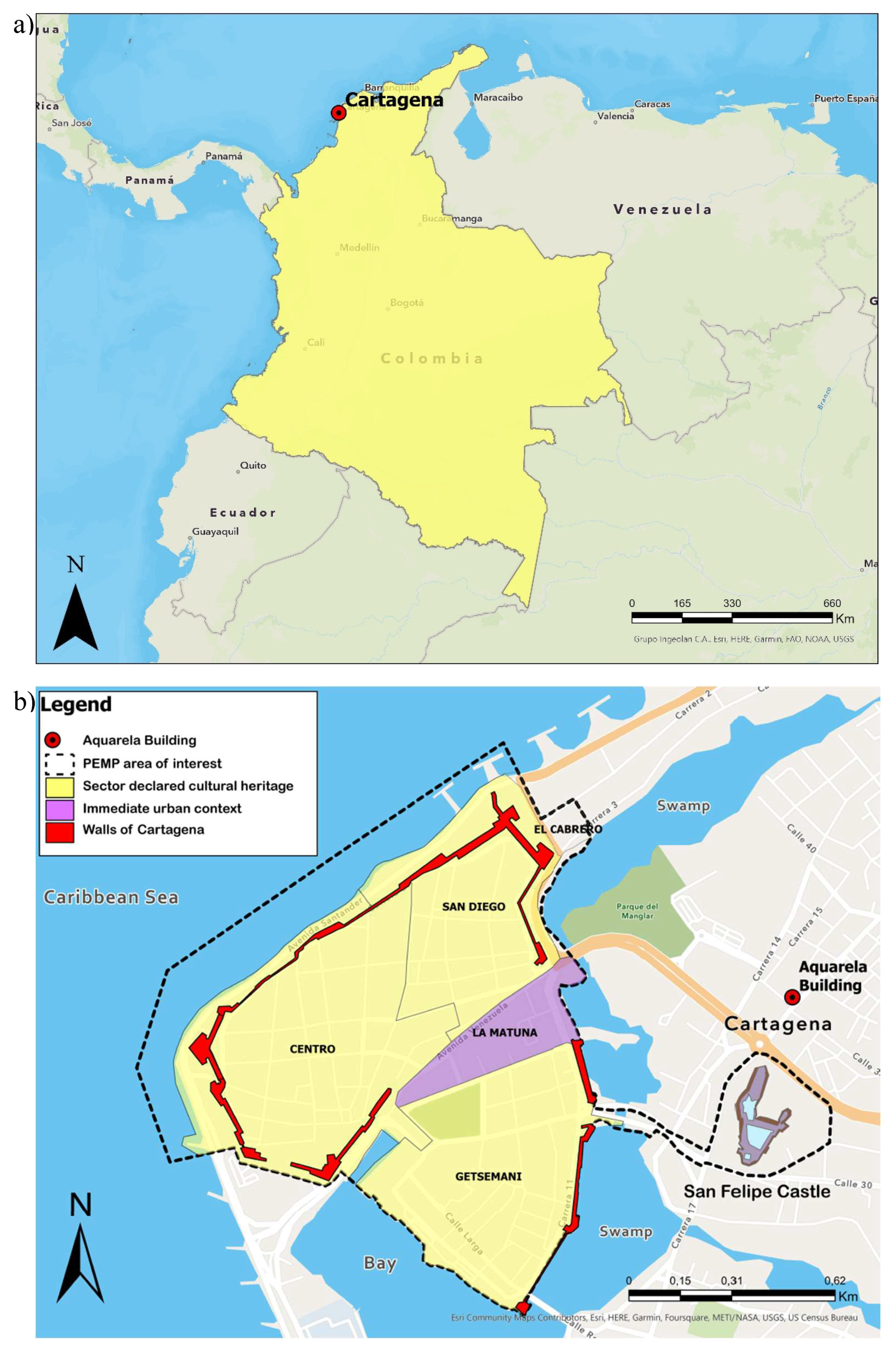

Heritage management in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, faces challenges that endanger its very existence. As mentioned above, since 1984, the city is considered a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which has led to a significant increase in tourism and pressure on historical sites. Tourism being the second source of income in the city after industry, [

51].

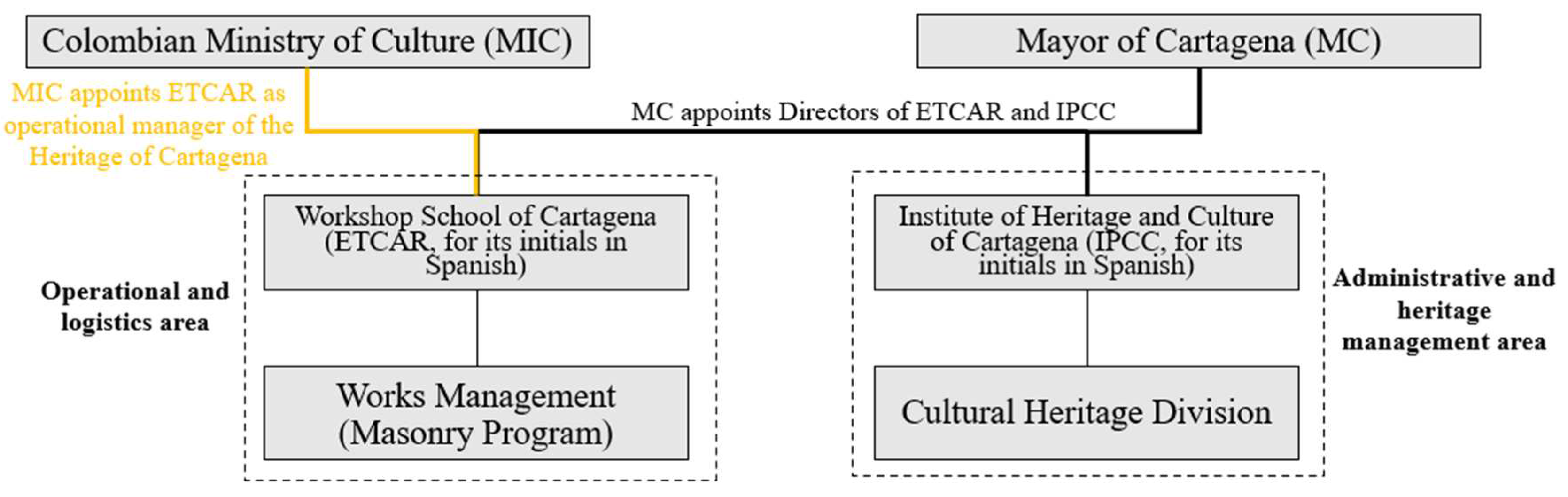

Heritage governance in Cartagena is the responsibility of the Cartagena Heritage and Culture Institute (IPCC, for its initials in Spanish), a public entity in charge of the protection, conservation, research and dissemination of the city's cultural heritage. The IPCC works in collaboration with other government entities and non-governmental organizations to develop restoration and conservation projects and promote cultural tourism.

Conversely, the Workshop School of Cartagena (ETCAR, for its initials in Spanish) is an educational establishment that operates on a non-profit basis and concentrates on providing technical and vocational education to young students hailing predominantly from low-income backgrounds. ETCAR's Masonry Program, titled "Labor Technician in masonry for new construction and restoration," equips students with practical expertise in various domains, including the preservation and restoration of cultural heritage. Since 2016, ETCAR has been designated by the Ministry of Culture of Colombia (MIC) to manage, preserve and value the fortified complex of the city by offering its tools, logistics and the labor of its young students.

The general director in charge of the ETCAR is appointed by the mayor of Cartagena de Indias, as well as the general director of the IPCC. Both entities, ETCAR and IPCC have a specific and independent division dedicated to cultural heritage.

The IPCC and the Escuela Taller de Cartagena are institutions that work together for the management and preservation of the cultural heritage of Cartagena de Indias. The IPCC is the entity in charge of managing, supervising and financing any activity related to material cultural heritage. However, it does not have an operational division of restorers or workers who can effectively carry out activities in the field of ordinary or extraordinary maintenance, consequently, this service is provided by the young people of ETCAR.

In addition, the MIC is the entity at the national level in charge of the promotion and protection of cultural heritage in Colombia. In this sense, it works together with the IPCC and ETCAR for the management and conservation of the cultural heritage of Cartagena de Indias, supporting projects for the restoration and conservation of heritage assets, as well as training programs in traditional trades, (

Figure 3).

3.1.1. A Critical Overview of the Current Cultural Heritage Governance in Cartagena

A comprehensive evaluation of the cultural heritage administration in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, under the purview of the Ministry of Culture (MIC), IPCC, and ETCAR, is imperative to ascertain their merits and shortcomings. Below, the authors highlight certain areas within wealth management that exhibit particular vulnerabilities, according to the information found in the webpages of this entities, and legislation available in Colombia regarding TCH, [

34].

The chain of command between MIC, IPCC and ETCAR is unclear. There is a certain ambiguity and overlapping of roles and functions regarding who controls the TCH, who proposes ideas and projects and who makes the decisions. Particularly, the IPCC and the MIC exhibit overlapping roles, leading to frequent conflicts and a diffusion of responsibility between the entities during critical situations necessitating prompt decision-making. Furthermore, it is found a notable absence of engagement from academic institutions, including faculties of architecture, engineering, heritage observatories, and research groups focused on heritage and restoration, in the governance process. Their involvement is conspicuously absent in project formulation, establishing scientific benchmarks for routine and exceptional maintenance interventions, as well as in the organization of spatial arrangements, traffic management, and the utilization of the heritage sites and their surroundings.

The IPCC and the MIC do not engage in ongoing monitoring of structural, architectural, archaeological, deterioration, and climatic variables surrounding Cartagena's TCH. This prevents the implementation of an efficient and effective management plan. Monitoring is essential to detect changes in heritage conditions and take preventive measures on time. The lack of funding to carry out this type of monitoring also makes it difficult to make decisions based on scientific data and the implementation of protection measures. Therefore, there is a paucity of exceptional restoration and maintenance initiatives and schemes, which restricts the ability to acquire funding from public entities, private corporations, and foreign investment funds to improve the present state of Cartagena's heritage.

Furthermore, the lack of training for the personnel involved in the structure is worrying. The workers in charge of heritage maintenance and restoration do not have an undergraduate degree in civil engineering or architecture or a postgraduate degree in restoration of heritage real estate to carry out interventions that guarantee the protection and conservation of heritage. The lack of education and training of personnel can have extremely negative consequences on the quality of interventions and the preservation of heritage.

On the other hand, the Special Management and Protection Plans (PEMPs, for its initials in Spanish) in Colombia are an essential planning and management instrument crucial to territorial organization. They were established under the General Law of Culture (1185 of 2008) to ensure the preservation, maintenance, and sustainability of cultural heritage. This legal framework specifies a unique regulatory framework for the safeguarding, protection, sustainability, dissemination, and promotion of the Nation's cultural heritage assets, specifically for those designated as Assets of Cultural Interest (BIC, for its initials in Spanish) with respect to tangible assets, in accordance with the valuation criteria and the regulations established by the Ministry of Culture. A preliminary version of the PEMP of the historic center of Cartagena is available on the website of the Mayor's Office of Cartagena. It is a complex and articulated document that should have the objective of complying with the requirements of the Ministry of Culture of Colombia, [

52]. Despite 15 years of effort by the authorities, the completion of this document has proven elusive. However, no judgment can be expressed in this regard since it is a version subject to changes, so it is currently not an official document. Therefore, it can be said that the city does not have an active PEMP.

The opinion of the authors is that heritage Governance in Cartagena is predominantly driven by political motives rather than technical factors. The prevailing governance approach appears passive, while the productive sectors, particularly the tourism and construction industries, assert an influential role by actively shaping heritage management to align with their economic requirements.

3.1.2. Proposing a Reform Framework for Tangible Heritage Conservation Governance in Cartagena

This section has a purposeful nature in order to improve the current state of governance and management of tangible heritage in Cartagena. The proposed approach is grounded in the heritage management practices implemented in the world's most developed countries possessing extensive cultural heritage [

53,

54,

55], with the aim of bringing Colombia's management practices in line with the most advanced global standards. These guidelines could potentially be integrated into Colombia's national heritage management framework.

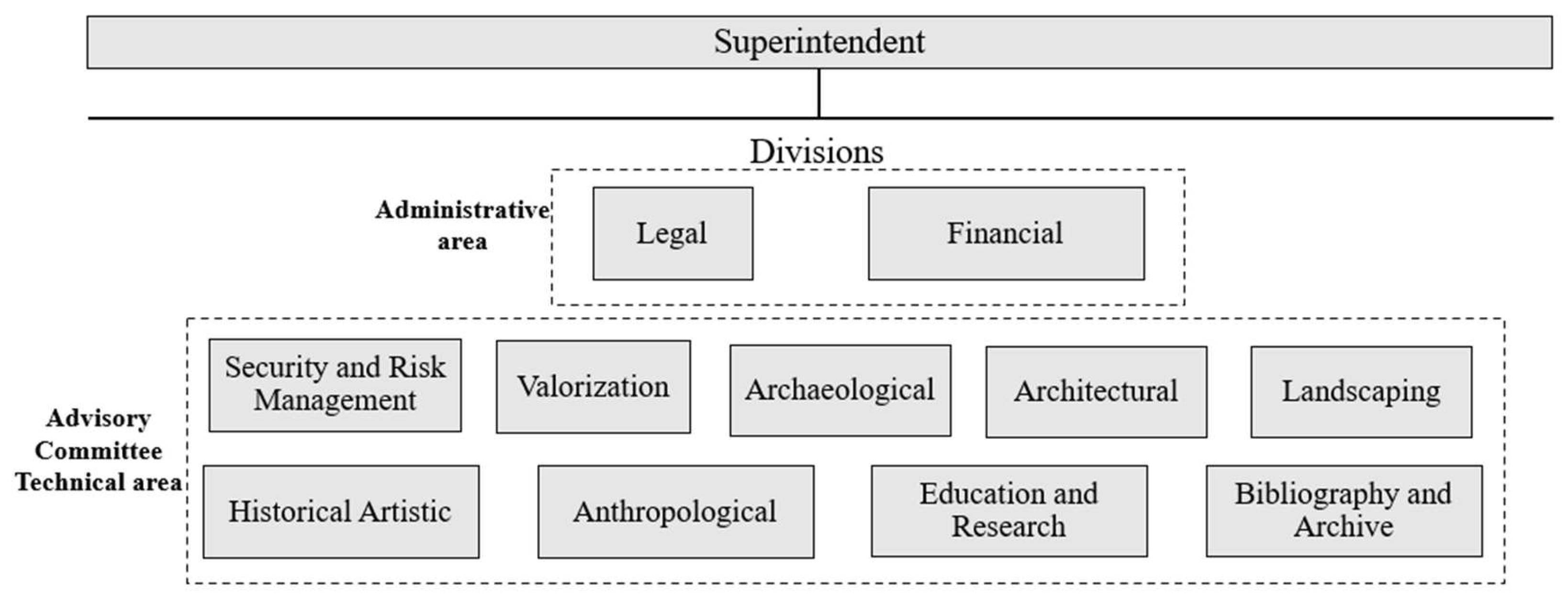

Figure 8 shows the proposed management scheme. The Ministry of Culture of Colombia should create a Superintendence of Cultural Assets at the National level. The Superintendency would be a peripheral body of the Ministry of Culture, made up of state offices distributed throughout the Colombian territory. Indicatively, each Superintendency could cover a department (region of Colombia). The superintendent and his advisory committee should be public officials who have won a public merit contest conducted by the National Civil Service Commission of Colombia. The profiles of each official must be defined by the Ministry of Culture according to its current guidelines. Regarding the Superintendent, her/his profile must include at least a bachelor's degree in architecture/civil engineering/cultural heritage, or similar, a master’s degree and PhD in topics related to cultural heritage, and significance experience studying and managing cultural heritage.

The local superintendents in the development of their functions respond directly to the Ministry of Culture. The functions that the IPCC currently has would pass completely to the Superintendence of the Department of Bolívar according to the scheme proposed above. Although it is called the Superintendence of the Department of Bolívar, it answers only to the Ministry of Culture.

The Superintendency would have various tasks, the most important of which are reported below:

Verification and declaration of the cultural interest of real estate in the area.

Cataloging of goods of cultural interest

Inspection activity in the field of competence

Authorization of building interventions in buildings or areas declared of cultural interest.

Imposition of conservation interventions on cultural heritage

Granting of contributions and facilitations for interventions for expenses caused by interventions for conservation and restoration of cultural heritage.

Supervise the design and management of conservation interventions in tangible heritage.

Concession for the use of cultural assets/concession of filming and audiovisual and photographic reproductions of cultural assets

Carry out research on cultural heritage in order to know its current state and plan its ordinary and extraordinary maintenance.

This organization would have countless advantages over the current organization. To mention a few, the Superintendence will have available a group of expert, public officials, in charge of the Risk Management, Valuation, Archaeology, Architecture, Landscape, Artistic, Anthropological, Education and Research, and library and archive sections. Each area will have its coordinator who will express his opinions to the Superintendent on the projects presented from his perspective and expertise. Currently, there is only a generic Heritage Division in the IPCC Technical Advisory Committee, so it is not clear if and how each expert has a voice on the projects regarding cultural heritage.

Additionally, the Superintendent and the members of the Technical Advisory Committee would not be freely removable and appointed officials, as is the case now in the IPCC, so their expertise and independence will strengthen their action. The continuity of the position, because they are public officials, will guarantee continuity in the management of the patrimony and thus it will be possible to propose long-term projects to generate significant improvements to the cultural heritage.

Any action that includes a material intervention in the heritage of Cartagena or any material asset of the Nation, including ordinary and extraordinary maintenance, should be carried out within the framework of projects or programs financed by the state or by external entities. It must be ensured that the contracted companies or universities have sufficient experience in the specific work and the workforce is qualified with a bachelor's degree in architecture/civil engineering/cultural assets, or similar, and a master's degree in restoration of tangible assets or similar.

In the case of Cartagena, ETCAR could participate in open calls to carry out the interventions programmed by the superintendency, complying with the aforementioned requirements to be able to intervene on the heritage or on the green areas and areas of interest around the heritage.

Finally, construction and/or restoration licenses for heritage assets will continue to be subject to the approval of the Planning Secretariat of the Mayor's Office of Cartagena, which may make observations from the point of view of land use and administration, but not from merit on the ordinary and extraordinary restorations and maintenance that may take place. Both the Mayor's Office of Cartagena and the Governor's Office of Bolívar, the Universities, the other state entities and private companies and foundations may present specific projects that involve heritage. These will be reviewed and evaluated by the Superintendency according to pre-established criteria and their feasibility will depend on the priorities defined by the Superintendency.

Finally, the authors highlight that the proposed structure is an example of how Heritage could be managed in Cartagena and Colombia. There may be other, more efficient and better organized structures, however, what the authors want to convey is that a paradigm shift is needed in heritage management. Those responsible for the heritage cannot be officials of free removal and appointment by mayors or governors who pursue political interests. It is necessary to subtract political power and add technical capacities to guarantee the care of the cultural heritage since it is about goods of National interest and of humanity.

3.2. A Critical Examination of the Contemporary Challenges in Cartagena's Tangible Cultural Heritage

The management of tangible cultural heritage in Cartagena faces significant challenges, such as a lack of adequate funding, the lack of a specialized management and protection plan, and an unclear chain of command with role ambiguities.

In the last decade, the tangible cultural heritage of Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, has been the subject of concern due to a series of problems that affect its conservation and preservation. In the literature there are several calls for attention to the competent authorities of Cartagena by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and UNESCO, [

28,

56,

57]. In particular, the authors, who studied cultural heritage for many years, knowing and living in the city, identified at least 12 problems that must be critically analyzed to understand their impact on the cultural heritage of Cartagena. These problems are briefly described below with some photographic records.

The first problem is related to the lack of regulation of vehicular traffic in the narrow streets of the historic center, a heritage area with tens of thousands of tourists and residents who travel daily, (

Figure 4).

The circulation of vehicles in the narrow streets of the historical district not only engenders noise and congestion but also poses a significant hazard to the structural integrity of heritage buildings and monuments. Furthermore, this situation leads to an unpleasant experience for visitors and locals and exacerbates the decay of heritage components such as pavements, facades and walls, frequently composed of delicate and fragile materials. The issue of total or partial pedestrianization of the historical center, which has received inadequate attention to date, is interrelated with this problem. Moreover, the absence of parking regulations in the heritage zone results in residents, employees, tourists, and the general populace parking inappropriately, thereby restricting the already-limited space available for vehicular traffic or loading and unloading goods for commercial activities. This often triggers long queues of honking vehicles in the downtown streets, contributing to significant noise pollution.

The second problem refers to the mismanagement of rainwater and residual water drainage, which causes frequent flooding and unpleasant odors. The lack of an adequate drainage system affects the stability of heritage buildings and monuments, as well as the health and safety of residents and tourists. In addition, the accumulation of water and waste generates a proliferation of microorganisms that favor the deterioration of heritage, insects and rodents, which increases the risk of vector-borne diseases. This problem is associated with the generally poor condition of the pedestrian platforms and a lack of management of the transversal profile of the historic streets. In the upper part of the wall, the drains do not have adequate slopes, so that in the end the water remains stagnant, favoring its infiltration into the embankment behind the wall. This can generate an increase in the lateral thrust on the walls, leading the structure to behave unpredictably under this new load.

The third problem pertains to the deficiency of sufficient public lighting surrounding the fortifications, which encourages improper utilization of the fortifications, such as acts of public urination and the occupation of homeless individuals who seek shelter in the drains of the structure. Proving this issue with scientific rigor presents a challenge; nevertheless, it is noteworthy that it is rarely addressed in the existing literature. The consequences of this situation extend beyond the city's image and reputation, as it also exerts a detrimental influence on the health and well-being of both citizens and tourists. The absence of adequate public lighting poses difficulties in establishing concrete evidence that supports the negative impacts associated with the inappropriate use of the fortifications. The lack of scientific studies or comprehensive investigations focusing on this specific issue contributes to its underrepresentation in the literature. Consequently, the profound effects on public health and well-being, as well as the tarnishing of the city's image, remain largely unexplored and undocumented.

Recognizing the significance of shedding light on this problem, further research should be conducted to gather empirical data and employ scientific methodologies that can substantiate the claims made regarding the adverse consequences of inadequate public lighting. By addressing this research gap, a more comprehensive understanding of the detrimental effects on both the physical and social aspects of the city can be achieved, thereby facilitating informed decision-making and enabling effective interventions to enhance the well-being and preserve the cultural heritage of Cartagena de Indias.

The fourth problem revolves around the absence of regulation pertaining to street vendors and informal businesses that have established themselves in close proximity, and in some cases, directly on top of monuments and historic buildings. This issue poses a unique challenge in terms of scientific proof, as the direct causal relationship between the presence of these vendors and the specific damage caused to heritage elements is difficult to establish with rigorous scientific rigor. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that this problem is rarely acknowledged or extensively discussed in the existing literature. The impact of unregulated street vendors and informal businesses on the integrity of heritage elements and the overall tourist experience is a crucial concern. The lack of proper guidelines and control measures allows for potential damage to occur, both physically and aesthetically, to the cherished architectural and cultural assets. Moreover, the presence of these vendors can significantly affect the experience of national and international tourists who visit the city, diminishing the authenticity and historical ambiance they seek.

Although scientific investigations that conclusively establish the exact extent of damage caused by unregulated street vendors and informal businesses are limited, anecdotal evidence and observations highlight their potential adverse effects. To address this research gap, further studies are warranted, combining empirical data collection, qualitative analysis, and stakeholder engagement. By shining a scientific spotlight on this issue, a more comprehensive understanding can be achieved, facilitating evidence-based policies, regulations, and interventions that strike a balance between preserving the cultural heritage of Cartagena de Indias and supporting sustainable economic activities.

The fifth problem encompasses the mismanagement of solid waste by both citizens and tourists. Authors have substantiated this issue through on-field observations, underscoring the direct evidence available regarding its occurrence. However, it is noteworthy that despite its practical significance, this problem is seldom mentioned in the literature. The mismanagement of solid waste contributes to the accumulation of refuse in the streets and heritage areas, leading to a multitude of detrimental consequences. From a health perspective, the presence of accumulated waste poses risks such as the spread of diseases, attracting pests and vermin, and causing environmental contamination. Furthermore, the visual pollution created by these unsightly waste piles negatively impacts the aesthetic appreciation of the surrounding heritage elements, detracting from the overall experience of both locals and visitors.

Despite the evident impact and tangible presence of this problem, its inclusion and discussion in scholarly literature remain scarce. The lack of attention given to this issue in scientific research may stem from the difficulty in quantifying and measuring the precise effects of mismanaged solid waste. Nonetheless, the significance of addressing this problem cannot be undermined, necessitating further research efforts to bridge the existing gap.

The sixth problem relates to the presence of horse-drawn carriages. The horses are often in an evident state of precarious health, in fact, on several occasions they have died in full service in the streets of the historic center. News of this kind are common in the local newscasts of Cartagena and Colombia [

58,

59]. This type of practice is not only cruel to animals, but it can also cause damage to pavements and affect the integrity of heritage elements, in addition to generating bad odors due to the excrement of these animals.

The seventh problem is related to the lack of control of environmental pollutants in the historic center. The emission of gases and particles by vehicles and the tourism industry, as well as the lack of regulation of commercial processes, can have a negative impact on the health of citizens and on heritage in general. Currently there is no departmental or national meteorological station in the historic center and there is no control of air and acoustic pollutants by the competent environmental authorities.

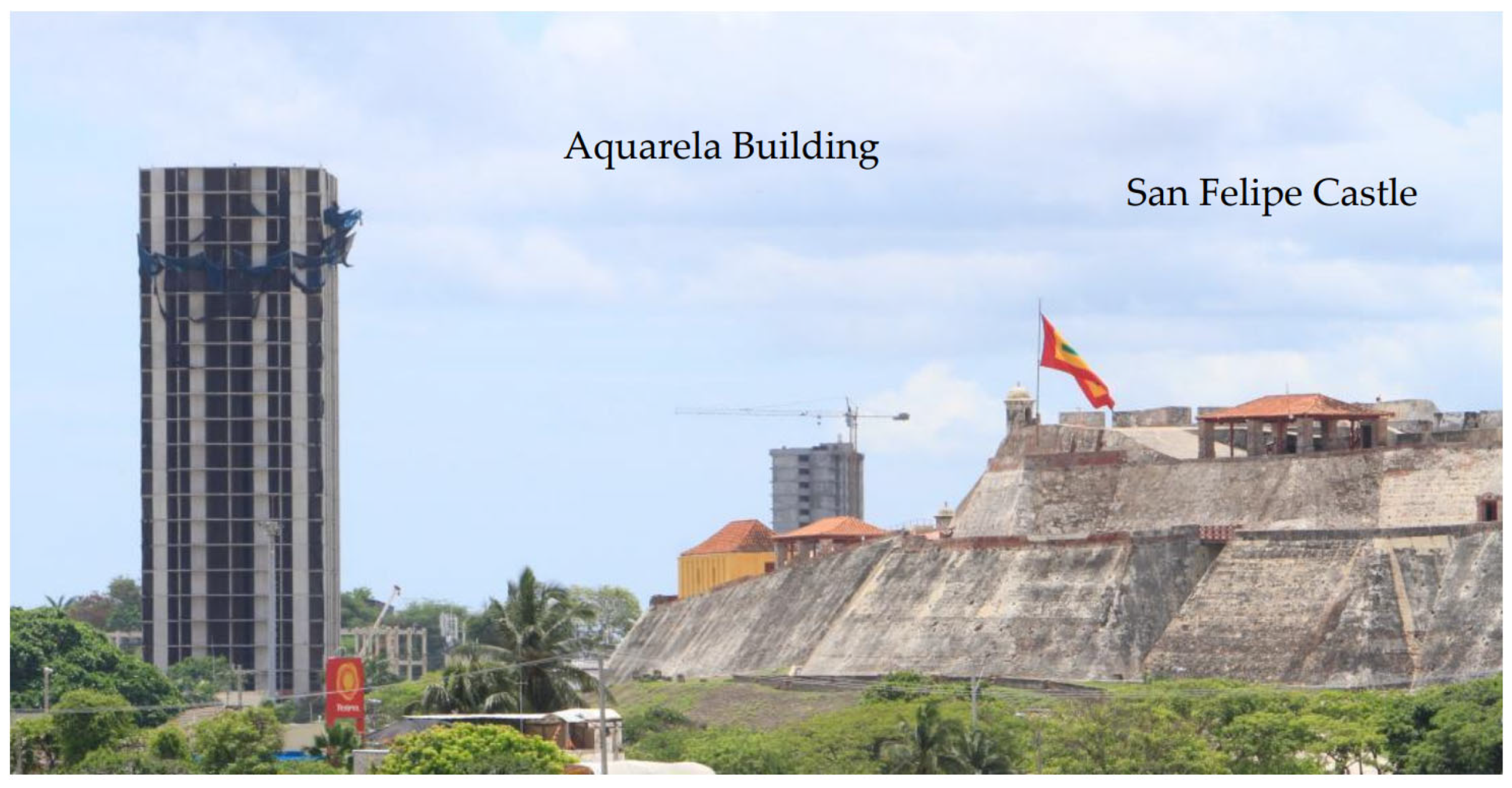

The eighth problem refers to the construction of the Aquarela project located less than 200 meters from the San Felipe de Barajas Castle in the area of heritage interest. This real estate project initially included five towers between 31 and 32 floors (approximately 100 meters high) each. It is worth mentioning that the Castle at its highest point is 40 meters high. This would disturb and destroy the historical-visual and symbolic relationship between the castle and its surroundings, jeopardizing one of the attributes that support the property's Outstanding Universal Value. The construction of this real estate project stopped when the first tower under construction had barely 20 floors (60 meters high, which is its current state). The competent authorities and the public realized only at that moment that this project was going to alter the image of the historic urban landscape, creating a visual interruption in the horizon line. In addition, its height and its modern design contrast with the colonial architecture of the city, which negatively affects the aesthetics and cohesion of the historic center. This situation was generated due to the lack of a comprehensive heritage management plan and the lack of effective regulation by the competent authorities in heritage preservation. As mentioned above, UNESCO in one of its recent committees on the heritage of Cartagena expresses its strong concern, in line with the evaluation of the ICOMOS advisory mission of 2017 [

28,

56,

57], on the impact of the Aquarela project on the values that support the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of the property. Similar conclusions are underlined by the National Council for Cultural Affairs on this point. However, 7 years after the ICOMOS report on the subject, and countless legal proceedings, the building is still there as shown in

Figure 5.

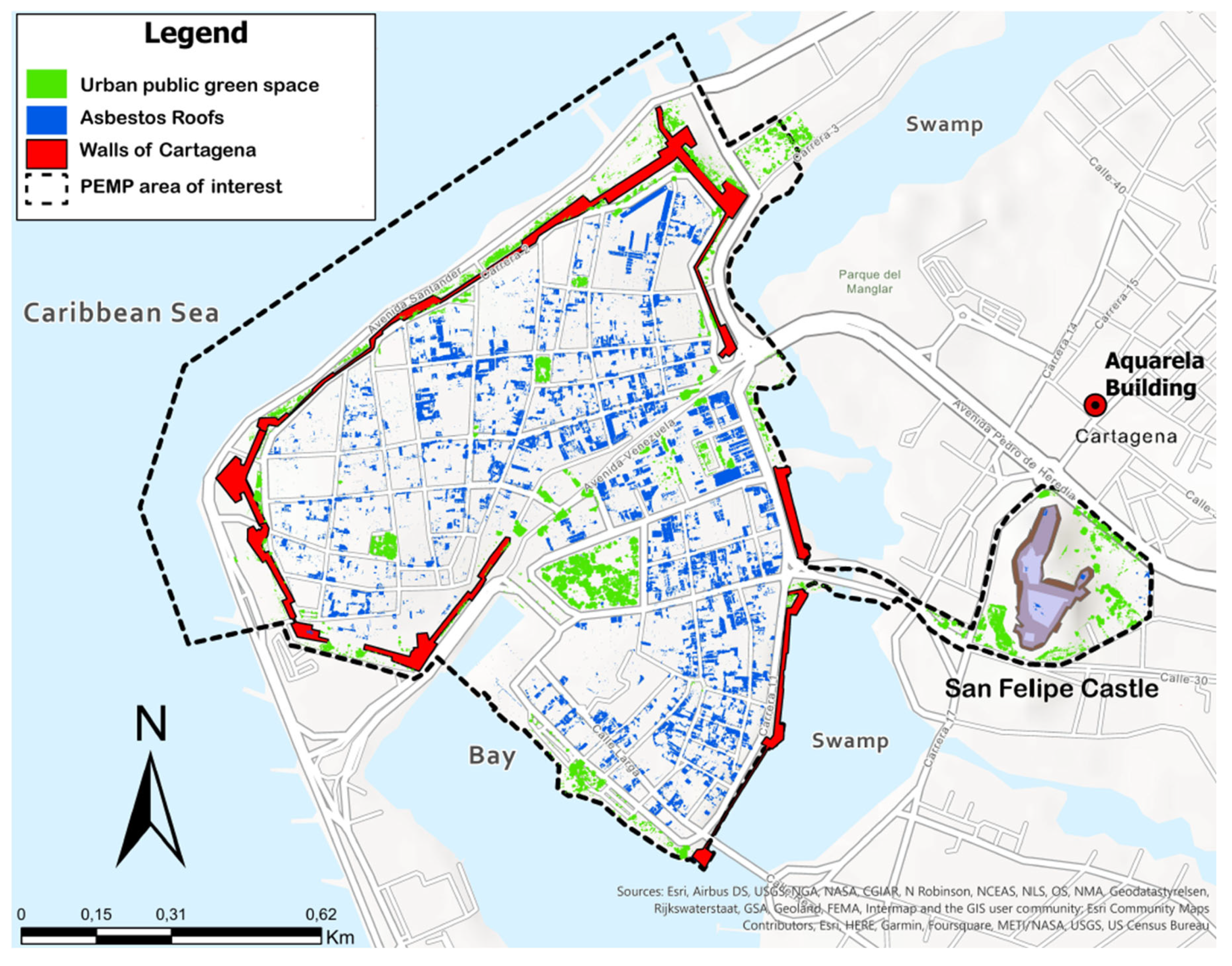

The ninth problem relates to the lack of public green in the historic center of Cartagena de Indias. The area of interest of the PEMP is 147.16 hectares. The classification of hyperspectral images shows that only 3.7% are public green areas that are actually usable by citizens and tourists, (

Figure 6). This may be common in some historical centers around the world. However, it is also accompanied by a tendency in the city to have a shortage of green spaces. As found in the literature, [

61,

62,

63], the scarce presence and care of green areas affects the quality of the air and the health of residents and tourists, in addition to being an important factor in the regulation of temperature and humidity in the environment. The lack of green areas also affects the quality of life, since these areas provide spaces for recreation, rest and relaxation, essential elements for people's physical and emotional well-being.

The tenth problem is the presence of asbestos-cement roofs in the study area. Asbestos, a carcinogenic mineral according to the World Health Organization (WHO), is commonly found embedded in roofs, [

64]. Its presence around the historical heritage has been scarcely studied, since it does not directly affect the heritage itself. However, when the cement matrix deteriorates, it releases asbestos fibers into the air in areas with a large flow of citizen tourists and workers in the tourism industry sector, [

65]. This brings to the fore the need to quantify and mitigate the problem, starting with the most frequented areas. Hyperspectral images shown that of the 1,597 properties in the study area, around 696 have asbestos-cement roofs, being almost 44% of the total, with a total asbestos-cement roof area of 10.5 hectares, (

Figure 6). This substantial quantity raises concerns for the first time within the historical and cultural context of Cartagena.

These two problems (vegetation and asbestos-cement roofs) are graphically evidenced in

Figure 6. Their impact is mainly reflected in more than 300,000 regular and irregular workers in the tourist area, and in the hundreds of thousands of tourists who spend their vacations in the historic center of the city each year, [

66,

67], since the residents in the tourist zone are a fraction of these, in continuous decrease.

Continuing, the problematic eleventh is represented by the lack of a clear methodology to choose replacement materials when there are deteriorated blocks or mortars. The lack of a clear methodology to select replacement materials can have negative consequences on structural integrity and heritage preservation. In fact, this is already reflected in the current state of deterioration of the fortifications, with an inadequate replacement of deteriorated stone blocks and the use of hydraulic mortars that have contributed to worsen the state of deterioration of the structure, [

29,

35,

37,

68]. The permeability of limestone blocks and mortars is an important factor in the durability of the masonry of the structure. Initially, rising dump and moisture from the embankment behind the wall, could escape mainly through the original lime-based mortars of the structure, being a more porous and permeable material than the limestone, [

38,

69]. Once the original mortars deteriorated, due to weathering or biodeterioration, they were progressively replaced by common hydraulic mortars, used in modern buildings. This generated a change in the pattern of moisture output, since now the most porous material is the limestone of the masonry blocks.

Figure 7 a) and b) show the original flow and the modified flow of moisture before and after the inappropriate mortar replacement. Therefore, a greater lateral hydraulic thrust can be generated in the structure. An image taken in-situ, in the Bastion of Santo Domingo (

Figure 7 c), allows to identify a pattern of greater deterioration in the limestone blocks in the area concerned by the replacement of inappropriate mortar. This bad practice in restoration generates an acceleration of the deterioration of the limestone blocks around the intervened areas in sectors of the Cartagena fortifications.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning the "Paradox of Theseus", which is a concept of the philosophy of identity that refers to the problem of determining the identity of an object over time. [

70,

71]. If all the parts of a ship are replaced over time, is it still the same ship? This problem arises when restorations and repairs are carried out on heritage assets. How much of the original structure must be preserved and how much can be replaced? At what point is the authenticity of heritage lost? It is a dilemma that arises in the management of tangible cultural heritage and one that requires a careful and well-informed approach. How do the competent authorities over the tangible heritage of Cartagena face this paradox?

Finally, the twelfth refers to the presence of prostitution and intensive sexual tourism in the historic center of Cartagena. This has negative effects on the tangible historical heritage of the city and on the perception of the city as a cultural destination, as well as on the quality of life of residents. In addition, sex tourism can generate a demand for accommodation infrastructure and services that do not meet heritage conservation standards. As a result, these activities may contribute to the degradation and deterioration of the city's cultural heritage.

It is evident that the competent authorities must undertake prompt and decisive measures to ensure the safeguarding and conservation of Cartagena's cultural heritage and to transform its management paradigm. This is imperative not only for the citizens' sense of identity and belonging but also because it constitutes a crucial source of income and economic development for both the city and the nation.

3.2.1. General Recommendations to Mitigate Existing Problems

To address the issues mentioned in section 3.2. of this document requires a multidisciplinary approach and coordinated action among the different actors involved, including competent authorities, universities and research groups, restoration experts, civil organizations, residents, and tourists.

Some recommendations are proposed below in the same order as the 12 problems mentioned above. This section does not intend to be exhaustive in analyzing the problem or in proposing the solution, since for this it would be necessary to carry out a specific research work for each problem with a general direction that points to the safeguarding of the city's heritage. Some of the solutions proposed below in this section are well known by heritage experts and have been theorized and implemented in literature and case studies in other cities around the world for at least 4 decades. However, in developing countries, such as Colombia, they continue to present alarming concern.

Regarding the first problem, lack of regulation of vehicular traffic, the implementation of restricted traffic zones can be considered, which limit the movement of vehicles in the historic center and promote the use of more sustainable means of transport, such as bikes, public transport and electric transport, [

72]. In addition, the implementation of measures to reduce the speed of vehicular traffic and the promotion of road safety education for drivers and pedestrians can be considered. Technical solutions can also be implemented, such as pavements that are more resistant to traffic and the implementation of loading and unloading areas for commercial purposes. The smart city concept should be applied in Cartagena as in other cities in the world, [

73,

74]. In the literature, there are investigations that relate urban merchandise transport and land use planning, as in the case of the center of the city of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, [

75]. The study uses geoprocessing techniques to analyze the spatial concentration of Freight Trip Generation Centers and GIS Multi-Criteria Assessment to identify suitability maps for urban logistics activities and land use compatibility. City Logistic strategies are established to support land use planning and the organization of logistics flows, considering the efficiency required by urban freight transport and the social costs involved in traffic congestion, environmental impacts and conservation of resources. energy. These City Logistic strategies and measures aim to support the improvement of urban logistics in the study area and could be useful in the case of Cartagena, as well as an identification of stakeholders and agreement on traffic limitation measures supported by statistical studies and comparison with other similar case studies worldwide.

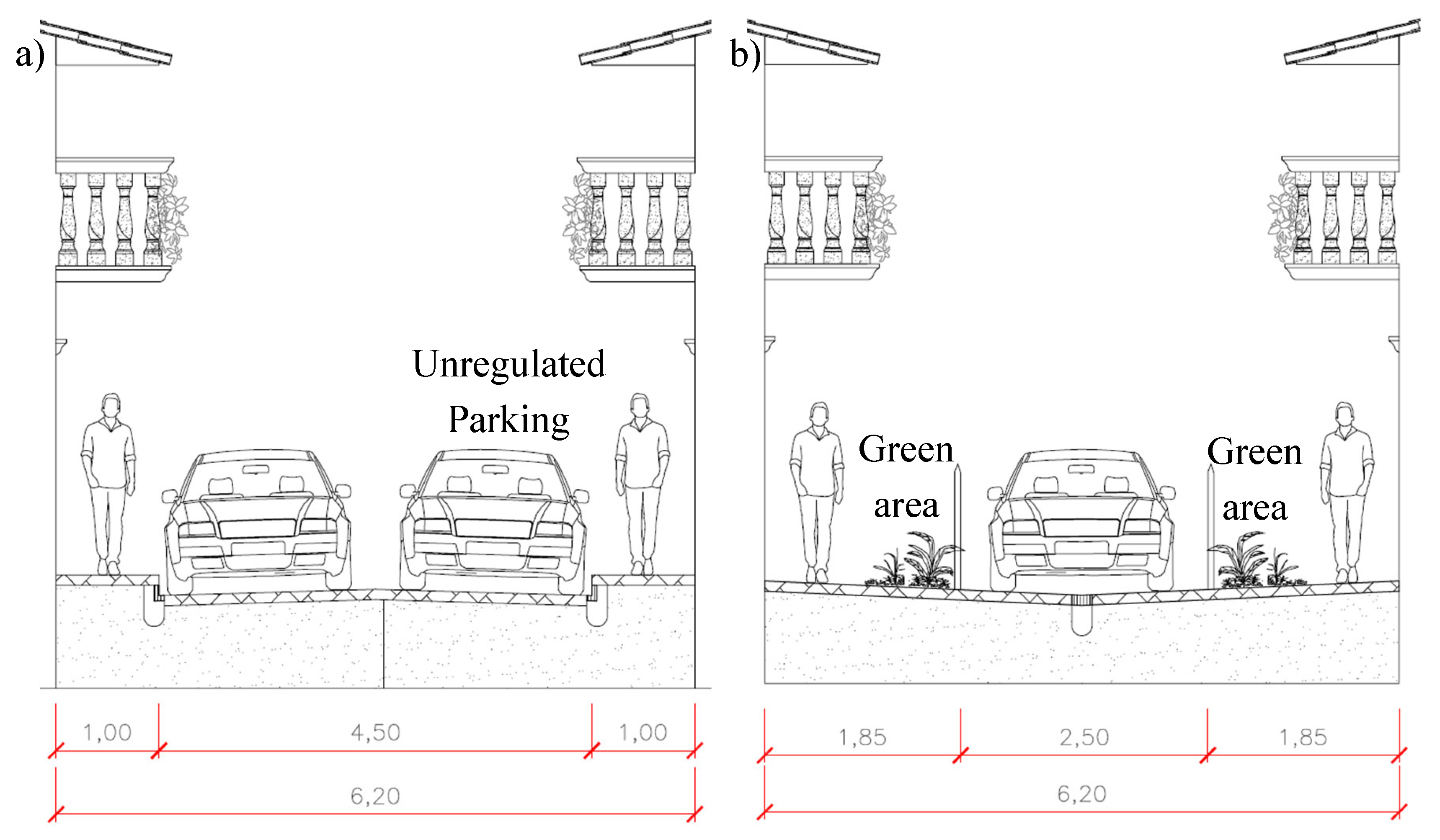

Figure 9 a) shows the typical cross-sectional profile of the historic streets of Cartagena. Its classic profile is observed, with more than 70% of the space dedicated to vehicular lanes, which thus become abusive parking lots, generating an oversaturation of vehicles in the center in search of parking. On the other hand,

Figure 9 b) proposes a reduction in the space for the vehicular lane, eliminating the possibility of parking in the narrow streets of the center, in order to reduce the vehicular flow. Additionally, the space for pedestrians is expanded. It is suggested to create a green space in the streets, now completely absent. The change in slope of the street profile will allow optimizing the maintenance of rainwater drainage. Spaces for unloading and loading goods should be identified in the city with a specific study on the concentration of commercial activities that have the greatest demand. There is currently no strategy to deal with this problem, whereby loading and unloading vehicles enter, exit and park without any restrictions of any kind.

Regarding the second problem, it requires the implementation of adequate drainage systems and the construction of infrastructures for the collection and treatment of wastewater. This may include the construction of cisterns and storage tanks, as well as the construction of storm drainage systems that integrate with the city's drainage system. It is also necessary to carry out adequate maintenance of the sidewalks and pavements to ensure that water flows into the drainage systems and does not accumulate in the streets. The Historic Center of Cartagena is located in some sectors below sea level, with a shallow water table, consequently, the drainage system requires a specific study and design that is beyond the scope of this work. To address the first two problems a reorganization of the transversal profile of the streets of the historical center is crucial.

Figure 9 shows a typical current section and a possible alternative to improve current conditions. A reconfiguration of urban spaces ought to involve a reduction in the width of the roadway to accommodate motor vehicle transit, while simultaneously eliminating any opportunities for unlawful parking within the street. Such measures should facilitate a greater human presence within the city's urban spaces and prioritize the expansion of public greenery wherever feasible. In addition, the operation of urban drainage would be simplified, with a single grid in the cross section instead of two, with lower management and maintenance costs.

Regarding the third problem, an improvement in public lighting is required, especially in the areas close to the fortifications. This may include the implementation of energy efficient LED lighting systems, which minimize the impact on the environment and reduce operating costs. Security measures may also be implemented to prevent unauthorized access to fortifications, which may include hiring security guards and installing surveillance cameras. These are security measures suggested by common sense, however, in the historic center of Cartagena they are not implemented.

The fourth problem is related to the lack of regulation of street vendors and informal businesses in areas close to monuments and historic buildings. To address this problem, measures can be implemented such as the creation of a registration and control system for informal vendors, as well as the delimitation of specific areas for their location, to reduce their presence in heritage areas. In addition, awareness and education campaigns can be established to promote the importance of heritage conservation and respect for regulations. In the literature [

76,

77,

78,

79] a discussion on the subject is found, analyzing the importance of street food vending in developing countries as a socioeconomic activity that provides prepared meals and employment opportunities. However, the informal nature of the street food trade can lead to unsanitary practices and health risks. Policies and regulations for the safe trade of street food are weak and poorly enforced in most developing countries. A security approach to the street food trade is recommended that starts with good agricultural practices and permeates the entire business chain. They also suggest the implementation of Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points, raising awareness through the dissemination of information, educating vendors and consumers on hygiene and safe food practices, and involving all stakeholders in the trade. The proper management of street food trade would guarantee safe practices and generate a safer and healthier society.

The fifth problem refers to the mismanagement of solid waste. It is a common complex problem among developing countries, which does not involve only the patrimonial part of the city but the entire city and almost the entire country. Again, the solutions are well known in the professional world, thus some general suggestions will be included here. Awareness and education campaigns on proper waste management and the importance of separation and recycling can be implemented. This would at least avoid having waste in the patrimonial streets. In addition, control measures and sanctions can be established for those who do not comply with the established regulations and creating selective waste collection programs in these heritage areas, to clean up the image of the city, a showcase for Colombia in the world.

To address the sixth problem, regarding horse-drawn carriages in the historic center, regulations and norms can be established to restrict the use of animals for this purpose in the historic center and promote sustainable transportation alternatives, such as bikes or electric vehicles. In some cities of the world such as Prague in the Czech Republic, starting from 1 January 2023, horse-drawn carriages were no longer permitted due to concerns about animal welfare and public safety, [

80]. The move is part of the city's efforts to reinvent itself as a destination for culture and gastronomy, moving away from its previous image as a city of cheap beer and strip clubs. While supporters argue that the carriages provide a romantic link to history and provide jobs, critics say the practice is cruel to the horses and can lead to accidents. Other cities, such as Budapest, Kraków, Palma de Mallorca, Chicago, New York, Melbourne, Montreal, are also either in process or already forbidden horse-drawn carriages, [

81,

82].

The seventh problem is related to the lack of control of environmental pollutants in the historic center, which can generate negative impacts on health and heritage, as well as in other historic centers around the world, [

83,

84,

85]. To monitor this problem, weather stations and pollutant measurement stations can be installed in the historic center that can be consulted in real time, with early warning systems that allow, together with the vehicular traffic restrictions addressed in point 1, to control and reduce the contaminants. In the literature, studies of environmental monitoring both outdoors and indoors are common in historic city centers, [

85,

86]. In addition, permanent noise control meters can be added, generating a monitoring and early warning system to prevent negative impacts on public health, and thus avoid conflicts between residents, tourists and commercial activities, [

87].

The eighth problem refers to the construction of the Aquarela Building, which has altered the image of the historic urban landscape and has generated a visual interruption in the horizon line. To solve this problem, the building should be demolished with the highest priority, to prevent UNESCO from inserting Cartagena's heritage among the assets at Risk. According to UNESCO regulations, this is the first step towards removing heritage from its list, with incalculable negative impacts on the tourism industry, employment, and the image of the city and the country.

The ninth problem refers to the lack of green areas in the historic center. Cartagena in general is one of the cities in Colombia with the least green areas per inhabitant, due to high building speculation and lack of application of urban regulations, [

88,

89]. To solve this problem, initiatives for reforestation and restoration of green areas in the historic center can be promoted, as well as the creation of parks and gardens that promote biodiversity and recreation. These spaces have been conceived, designed and implemented on several occasions in Cartagena, however, the problem is that resources are not budgeted to monitor the trees planted, so in the end, these activities are often only propaganda with little impact on the city and the historic center. The Superintendency should be in charge of caring for these green areas since they are included in the area of heritage interest.

The tenth problem, related to the presence of asbestos-cement roofs in the heritage area, requires a comprehensive, complex and articulated strategy between environmental authorities, heritage management authorities, including companies and private construction companies, to minimize the dispersion of fibers in the environment during maintenance work, and removal. As well as establishing specific guidelines for the safe disposal and removal of the material. In developed countries in Europe or Australia, among others, there are strict regulatory frameworks on this problem, [

46,

90]. However, in developing countries, such as Colombia, this problem is still unknown or in the regulatory phase. Consequently, long awareness campaigns should be carried out, as well as pressure on the competent authorities to propose regulations that aim to solve the problem.

Regarding the problematic eleventh, the materials used for the replacement should be selected based on physicochemical, mechanical and aesthetic parameters to avoid affecting the mechanical behavior of the structure. There are methodologies in the literature that propose selecting replacement blocks based on mass, porosity, even using non-destructive techniques such as ultrasound, or making thin sections of the stone to evaluate and compare the petrographic characteristics of the stone of the structure and of quarry stone, [

37,

91,

92]. On the other hand, with respect to replacement mortars, non-hydraulic lime-based mortars are required, with dosages that must be custom formulated through physicochemical and mechanical analyzes of the original mortars in-situ. The hydraulic mortars widely used in the structure and shown in

Figure 7 c), must be entirely replaced, since their permanence in the structure generates damage that spreads and worsens each year.

Finally, the presence of prostitution and intensive sexual tourism in the historic center, [

93]. It is a complex and morally relevant issue. Therefore, Colombian regulations should be followed in this regard without tolerance zones. Constant monitoring of social workers and health authorities could help mitigate the problem. In addition, national and international advertising campaigns should show the cultural value of Cartagena's heritage and discourage prostitution.

In the context of Cartagena's Tangible Cultural Heritage, the concept of resilience becomes vital due to the city's governance issues and the potential threat of UNESCO classifying it as heritage in danger. Urban resilience, pertaining to tangible cultural heritage, pertains to the city's capacity to adapt, endure, and recover from shocks and stresses while safeguarding its cultural heritage assets, [

94,

95]. It necessitates the implementation of strategies and measures that preserve, protect, and sustainably manage the cultural heritage despite challenges like natural disasters, climate change, urbanization, and social disruptions. By integrating tangible cultural heritage into urban planning and development processes, urban resilience ensures the preservation of Cartagena's cultural identity, social fabric, and historical significance during crises. Additionally, leveraging cultural heritage assets as resources for community building, economic development, and sustainable tourism plays a vital role. Engaging local communities and stakeholders in the planning, decision-making, and implementation of resilience strategies empowers them to actively contribute to the enhancement of tangible cultural heritage resilience. This comprehensive approach enables Cartagena to withstand disruptions while simultaneously safeguarding and celebrating its cultural heritage, contributing to the city's overall well-being and vibrancy.

As mentioned above, the problems of Cartagena's heritage are complex and articulated among themselves. The objective of this paper is not to propose a specific solution to each of them, but rather to highlight the problems and propose conceptual solutions. This, although it seems basic in the context of developed countries, in Colombia and in developing countries is of primary importance and relevance, since they are problems that tourists and citizens experience daily and that have been there for many decades without a solution.