Submitted:

18 May 2023

Posted:

19 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. The Rwanda Context and Unpaid Care Work

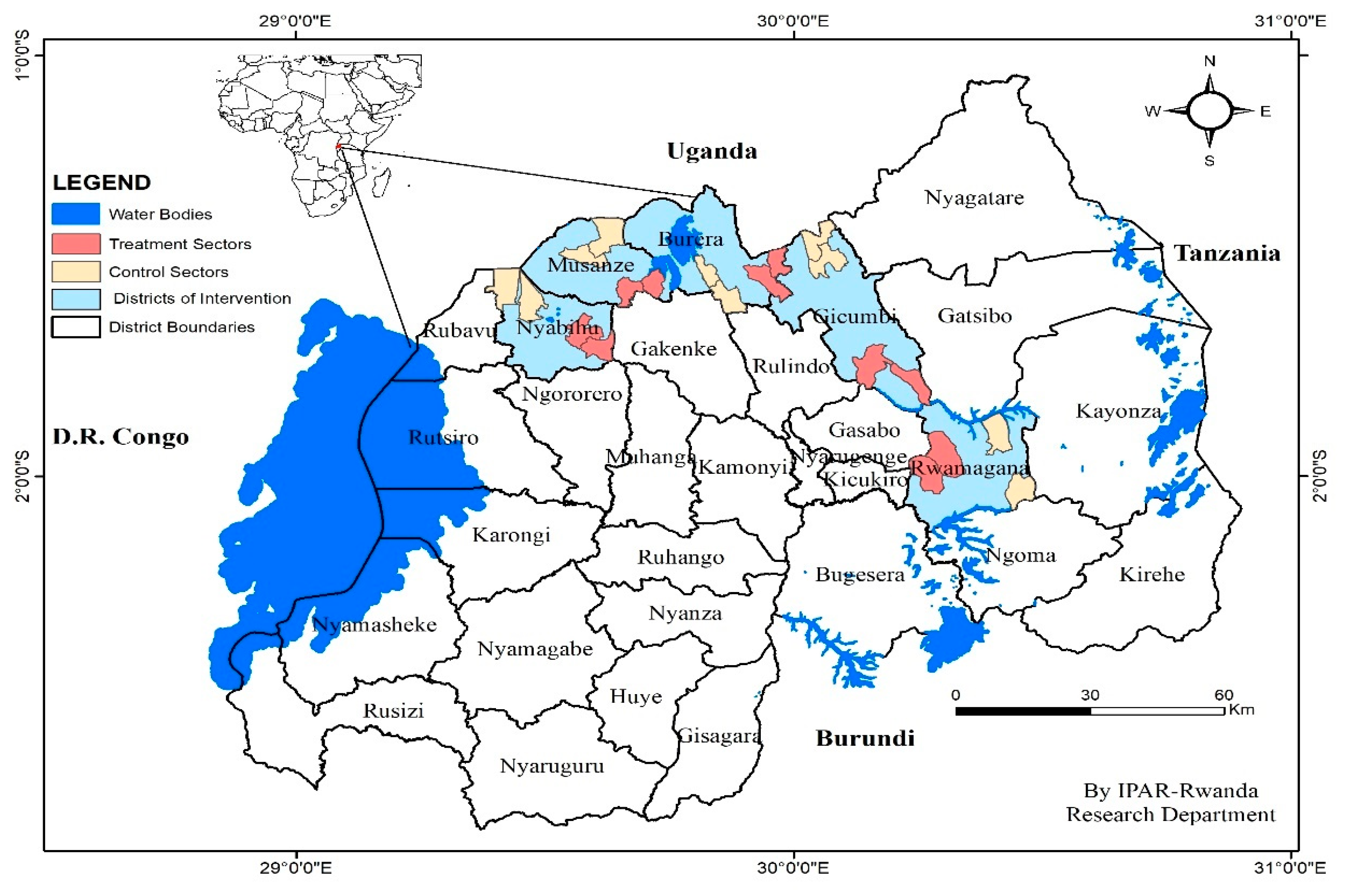

3. Methodology/Methods/Design

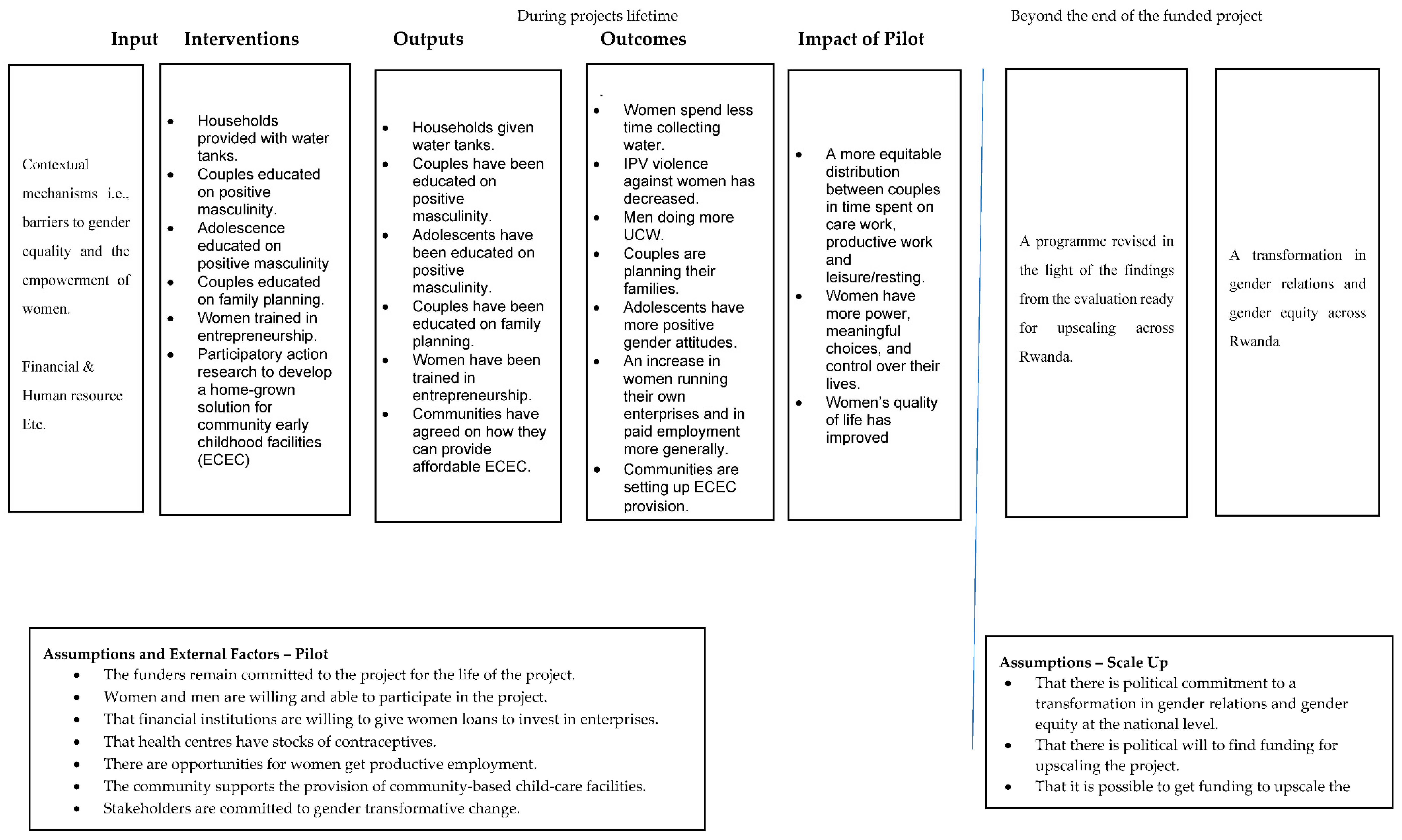

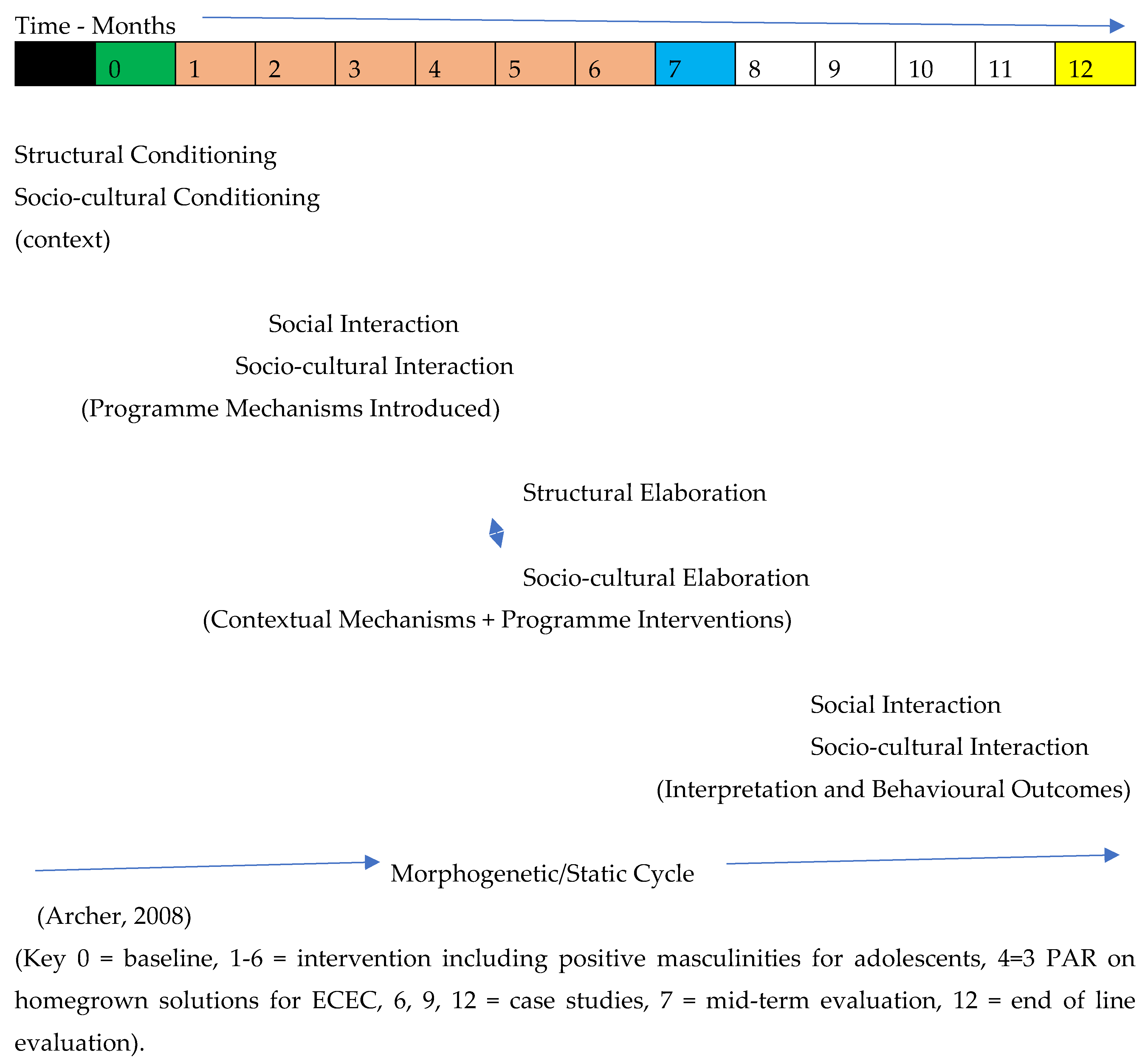

3.1. Study Design

- water tanks for rainwater harvesting to reduce the time women spend collecting water;

- a training session on positive masculinities aimed at increasing the UCW men do, reducing IPV and more generally leading to women’s empowerment;

- two training sessions on entrepreneurship for women to enable them to set up household enterprises and become economically empowered;

- two training sessions on sexual and reproductive health rights to couples to encourage family planning, use of modern contraception, and respect for women’s right to bodily integrity;

- Regular home visits by trained workers and monitoring for the six months of project implementation.

- Enumerate the outcome patterns - what mechanisms worked for what women in what circumstances in reducing and redistributing UCW;

- To show what impact the mechanisms had on gender relations, women’s empowerment, and their quality of life;

- To uncover how the interventions tackled the barriers to reducing and redistributing women’s UCW and gender equality and women’s empowerment;

- To explain how and why the interventions worked how they overcame the barriers to gender equality and women’s empowerment in the intervention clusters.

3.2. Participants and Sample Size

3.3. Intervention and Research Implementation

3.4. Data analysis

3.5. Ethical Considerations and Safeguarding

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Availability of data

Acknowledgement

Competing interests

Disclaimer

| i | The main characteristics of UCW are that it is: unpaid, the individual performing the work is not paid in cash and/or in kind; care, the activity provides for the health, wellbeing and maintenance of members of the household or community; and work, the activity involves mental and /or physical effort and is costly in terms of time (Ferrant et al., 2014). |

| ii | It is not possible within the limits of writing a research protocol to discuss critical realism as an enquiry paradigm. For the interested reader Andrew Sayer (2000) and Danermark et. al. (2019) provide accessible introductions. |

| iii | R des F did consider including a community child-care intervention based on the Rwandan Government’s policy, but the Ministry of Gender advised that it would be premature to do this as insufficient was known about the acceptability and practicality of such provision. |

| iv | The research will follow the requirements of UK R&I policy on safeguarding and UK R&I Guidance on Safeguarding in International Development. There are four safeguarding issues relating to the project, the risks associated with COVID-19, interviewing vulnerable women, the risks of junior researchers being bullied and harassed by more senior researchers, and the risk of researchers being distressed by the disclosures that vulnerable women make. |

References

- Abbott, P., and D’Ambruoso, L. (2019). Rwanda Case Study: Promoting the Integrated Delivery of Early Childhood Development.

- Abbott, P., and Malunda, D. (2016). The Promise and the Reality: Women’s Rights in Rwanda. African J. Int. Comp. Law 24, 561–581. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P., Malunda, D., Mugisha, R., Mutesi, L., and Rucogoza, M. (2012). Women’s Economic Empowerment in Rwanda: A Situational Analysis.

- Action Aid (2020). National Level Research to Assess the Effect of Unpaid Care Work on Women’s Economic Participation in Rwanda.

- Archer, M. (1996). Social integration and system integration: developing the distinction. Sociology 30, 679–699. [CrossRef]

- Archer, M. (2008). Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bilfield, A., Seal, D., and Donald, R. (2020). Brewing a More Balanced Cup: Supply Chain Perspectives on Gender Transformative Change within the Coffee Value Chain. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 11, 26–38.

- Bonell, C., Moore, G., Warren, E., and Moore, L. (2018). Are randomized Controlled Trials Positivist? Reviewing the Social Science and Philosophy Literature to Assess Positivist Tendencies of Trials of Social Interventions in Public Health and Health Services. Trials 19, 238.

- Budlender, D. (2010). “What do Time Use Studies Tell Us about Unpaid Care Work? Evidence from Seven Countries,” in Time Use Studies and Unpaid Care Work, ed. D. Budlender (Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development).

- Chopra, D. (2021). “Paid Work and Unpaid Care Work in India, Nepal, Tanzania, and Rwanda: A Bi-directional Relationship,” in Women’s Economic Empowerment: Insights from Africa and South Asia, eds. K. Grantham, G. Dowie, and A. de Haan (London and New York, NY: Routledge).

- Chopra, D., Kelbert, A. W., and Iyer, P. (2013). Empowerment of Women and Girl.

- Danermark, B., Ekström, M., and Karlsson, J. C. (2019). Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences. London and New York, NY: Routledge.

- Doyle, K., Levtov, R. G., Barker, G., Bastian, G. G., Bingenheimer, J. B., Kazimbaya, S., et al. (2018). Gender-transformative bandebereho couples’ intervention to promote male engagement in reproductive and maternal health and violence prevention in Rwanda: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 13, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Eggers del Campo, I., and Steinert, J. I. (2020). The Effect of Female Economic Empowerment Interventions on the Risk of Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma, Violence, Abus. [CrossRef]

- Ferrant, G., Pesando, L. M., and Nowacka (2014). Unpaid Care work: The missing Link in the analysis of Gender Gaps in Labour Outcomes.

- Ferrant, G., and Thim, A. (2019). Measuring Women’s Economic Empowerment Time Use Data and Gender Inequality.

- Geertz, C. (1975). Interpretation of Culture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press Available at: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B01M1GJ0D1/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1.

- Halim, D., Perova, E., and Reynolds, S. (2021). Childcare and Mothers’ Labor Market Outcomes in Lower- and Middle-Income Countries. [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, E., Karim, N., Mohanraj, P., and Wu, D. (2015). Measuring Gender-transformative change A Review of Literature and Promising Practices.

- IDRC (2020). Mapping the Policy Landscape for Women’s Economic Empowerment in Rwanda.

- Jensen, S. K., Placencio-Castro, M., Murray, S. M., Brennan, R. T., Goshev, S., Farrar, J., et al. (2021). Effect of a home-visiting parenting program to promote early childhood development and prevent violence: A cluster-randomized trial in Rwanda. BMJ Glob. Heal. 6, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. (2012). Empowerment, Citizenship and Gender Justice: A Contribution to Locally Grounded Theories of Change in Women’s Lives. Ethics Soc. Welf. 6, 216–232. [CrossRef]

- Katabarwa, J. K. (2020). Policy Mapping: Women’s Economic Empowerment in Rwanda.

- Kennedy, L., and Roelen, K. (2017). ActionAid’s Food Security and Economic Empowerment Programme in Muko Sector, Northern Rwanda: Guidelines for Achieving the Double Boon.

- Long, K., Brown, J. L., Jones, S. M., Aber, J. L., and Yates, B. T. (2015). Cost Analysis of a School-Based Social and Emotional Learning and Literacy Intervention. J. Benefit-Cost Anal. 6, 545–571. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-benefit-cost-analysis/article/abs/cost-analysis-of-a-schoolbased-social-and-emotional-learning-and-literacy-intervention-1/2167979501B6C6D158F337F1458E407A.

- Meyer, S. B., and Lunnay, B. (2013). The Aplication of Abductive and Retroductive Inference for the Design and Analysis of Theory-Driven Sociological Research. Sociol. Res. Line 18, 12. Available at: https://www.socresonline.org.uk/18/1/12/12.pdf.

- Mies, M. (1986). Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour. London: Zed Books. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M. (2014). Measuring Gender Transformative Change.

- National Institute of Statistics (2020a). Labour Force Survey Annual Report 2019. Available at: https://www.statistics.gov.rw/datasource/labour-force-survey-2019.

- National Institute of Statistics (2020b). Labourforce Survey 2019 Thematic Report on Gender.

- National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (2018). The Fifth Integrated Living Conditions Survey: Main Indicators Report.

- Nicholas, N., Ovenden, G., and Vlais, R. (2020). Evaluating Behaviour Change Programs for Men who Use Domestic and family Violence: Key Findings and Future Directions.

- Pawson, R. (2013). The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto. London: Sage.

- Porter, S., McConnell, T., and Reid, J. (2017). The Possibility of Critical Realist Randomised Controlled Trials. Trials 18, 133.

- Rohwerder, B., Müller, C., Nyamulinda, B., Chopra, D., Zambelli, E., and Hossain, N. (2017). ‘You Cannot Live Without Money’: Balancing Women’s Unpaid Care Work and Paid Work in Rwanda.

- Ruane-McAtee, E., Amin, A., Hanratty, J., Lynn, F., Willenswaard, K. C. van, Reid, E., et al. (2019). Interventions addressing men, masculinities and gender equality in sexual and reproductive health and rights: an evidence and gap map and systematic review of reviews. BMJ Glob. Heal. 4, e001634. [CrossRef]

- Seedat, S., and Rondon, M. (2021). Women’s wellbeing and the burden of unpaid work. BMJ 374, n1972. [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, M. (2013). Women’s unpaid work in the home is a ‘major human rights issue. UN News.

- Vogel, L. (1983). Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [CrossRef]

- World Bank (2020). Women Business and the Law 2020. Available at: http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/102741522965756861/WBL-Key-Findings-Web-FINAL.pdf.

- World Bank (2022). Overview Rwanda. #Africa Can. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/rwanda/overview#1 [Accessed February 27, 2022].

| Research Questions | Survey Data Questions | 7-day Time Diaries | FGDs & Key Informant Interviews | Case Study Households | Participatory Action Research - ECEC | Cost Analysis |

| For which women and under what circumstances, and how does providing households with labour-saving devices (water tanks) reduce the burden of UCW for women? | Time spent collecting water by all members of the household | Tell me about how the time members of your household spent collecting water has changed since you started using a water tank? Why has this change occurred? | ||||

| For which women and under what circumstances, and how does training in entrepreneurship enable women to set up productive micro-enterprises? | Employment, borrowing, contribution to household cash income | Time spent running an enterprise by women | Please tell me about any changes in women’s income-generating strategies in your village in the last 6 months. Why and how have these changes taken place. What are the barriers to women setting up enterprises? |

What changes have occurred in your household’s income-generating strategy in the last 3 months? Why and how have these changes occurred? What would have to change for you/your wife to set up an enterprise? |

||

| For which men under what circumstances and how does taking part in positive masculinity dialogues lead to positive changes in attitudes and behaviour to gender equality and the empowerment of women? (As reported by husbands and wives) | Economic empowerment Political empowerment Decision making in the household. Control over economic resources Bodily integrity and domestic violence (women only) |

Time spent doing income-generating work. Time spent on leisure and personal care. |

Please tell me about any changes in men’s behaviour in the last 6 months. Why do you think these changes have taken place? Why do some men think that it is OK to abuse their wives? How can domestic violence be prevented? |

Have there been any changes in the relationship between you and your husband(wife) in the last 3 months? Why have these changes occurred? |

||

| For which men, under what circumstances and how does taking part in positive masculinity dialogues lead to them taking on more responsibility for UCW? (As reported by women and men. | Gender roles Gendered division of labour in the household |

Time spent doing UCW | Tell me about men’s attitudes to care and domestic work? Why do you think that men have these attitudes? |

Have there been any changes in who is responsible for your household's care or domestic work in the last 3 months? What would have to change for your husband/you to take on more responsibility for it? |

||

| For which women and under what circumstances have the interventions positively impacted their wellbeing and quality of life? | Kessler Psychological Distress Scale Quality of life scale Domestic violence questions (wives only). |

What makes women dissatisfied with their lives and why? What changes would make women more satisfied with their lives and why? |

Tell me about any changes in how you feel about your life in general over the last 3 months. What changes in your daily life would be necessary for you to enjoy life more? |

|||

| For which couples, under what circumstances, and why has there been a redistribution of reproductive and productive labour? (As reported by husbands and wives). | How much of the unpaid care work do you do? If these 20 beans represented all the UCW done in your household, how many would represent your share? | Time spent on a different activity across the day and week | What are the expectations in your village of what women and men are responsible for in your village? What would have to change for the division of labour between men and women to change |

What are the main tasks you are responsible for in looking after your household, and what are your partner's responsibilities? Why is this the case? |

||

| How cost-effective is the programme, and how can it be scaled -up? | Cost analysis of interventions. | |||||

| What is the feasibility, desirability, and practicability of introducing Homebased ECD Facilities? | Time spent caring for children under 7-years. | Tell me about policies that could be introduced to enable women to have more time to do paid work? | What difference would it make to your household if there was ECEC for infants and young children? How would it make this difference? | Participants asked, over a series of three workshops, to agree on homegrown solutions that would work for them. | ||

| What are the key lessons from the research findings for programming and policy formulation for women’s empowerment in Rwanda? | Acceptability of the recommendations from the participatory workshops. | Acceptability of the recommendations from the participatory workshops. | Recommendations from participatory workshops. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).