Submitted:

19 May 2023

Posted:

22 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Sources and Search Procedure

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

3. Results

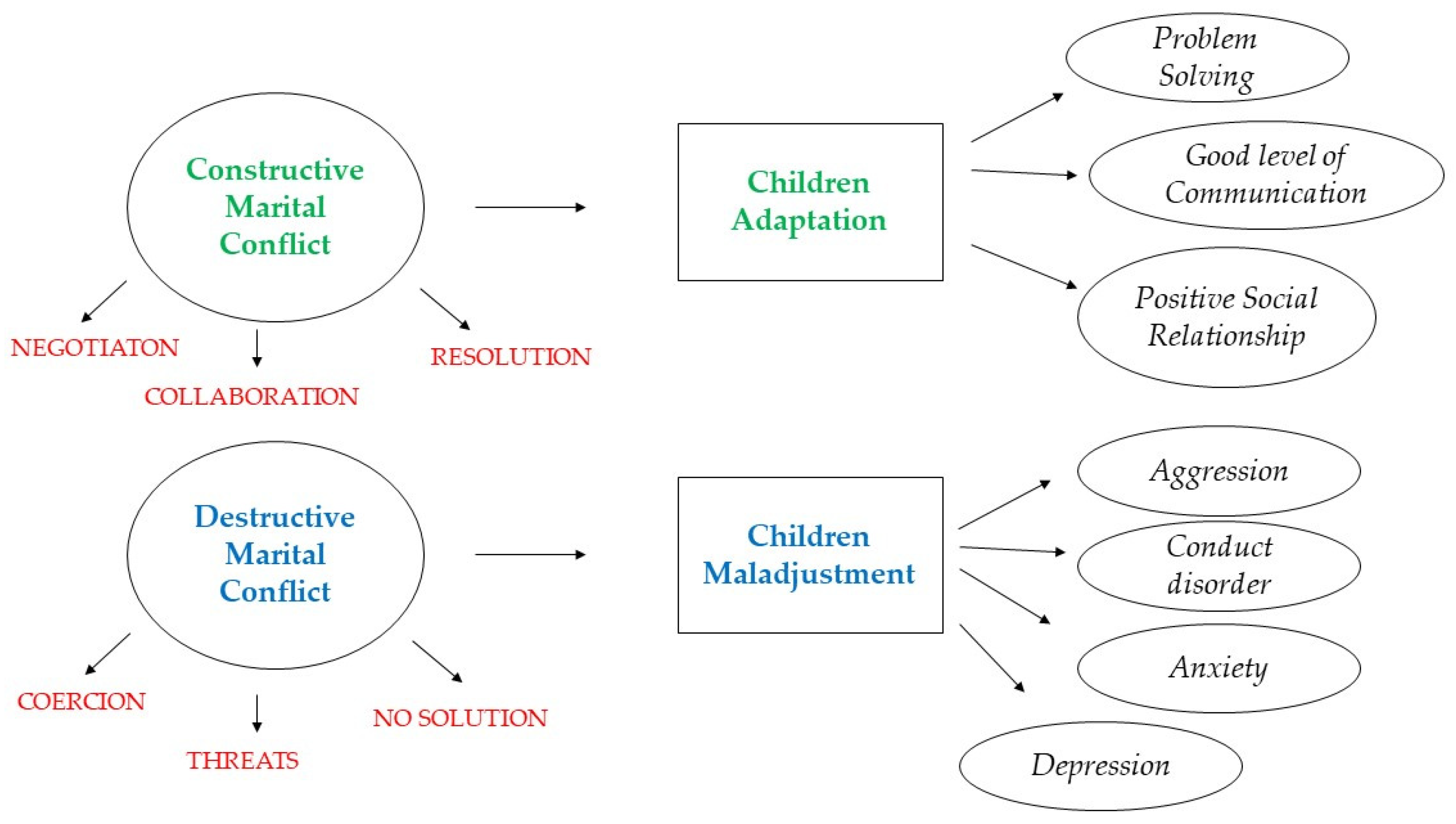

3.1. Styles of Conflict: Constructive and Destructive Marital Conflict

3.2. Relationship between Constructive and Destructive Marital Conflict and Children and Adolescents’ Adaptation

3.3. Relationship between 5 different processes of Conflict and Children and Adolescents’ Adaptation

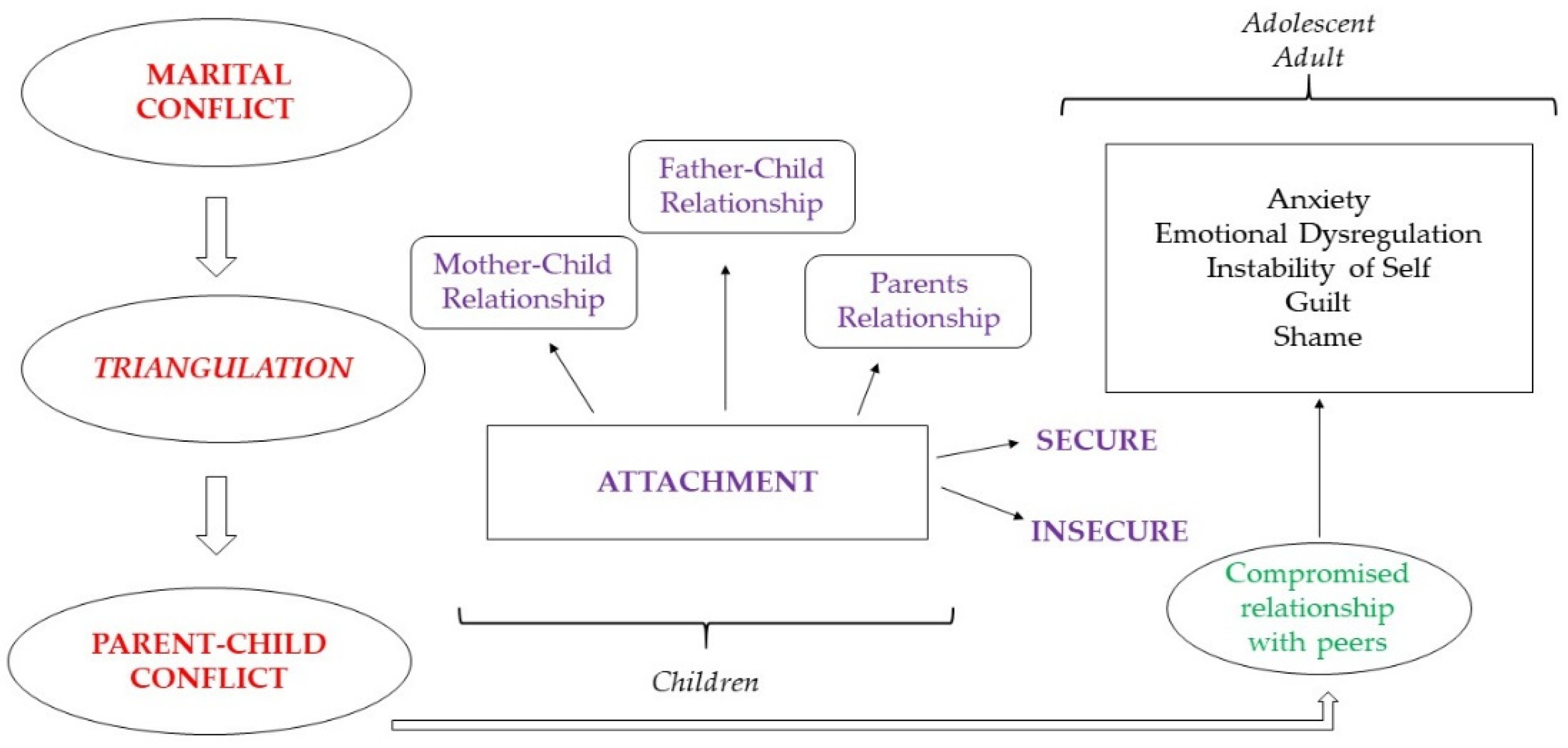

3.4. Relationship between Marital Conflict, Triangulation and Attachment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gambini, P. Psicologia della famiglia: La prospettiva sistemico-relazionale; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scabini, E.; Cigoli, V. Il famigliare: Legami, simboli e transizioni; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Volpi, R. La fine della famiglia; Mondadori: Milano, Italia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, J.S.; Kelly, J.B. Effects of divorce on the visiting father-child relationship. Am. J. Psychiatry 1980, 137, 1534–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein, J.S. Children of Divorce: Preliminary Report of a Ten-Year Follow-up of Older Children and Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Psychiatry 1985, 24, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malagoli Togliatti, M.; Lubrano Lavadera, A. I figli che affrontano la separazione dei genitori. Psicol Clin Sv 2009, 1, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Deater-Deckard, K. Children’s views of their changing families; York Publishing Services: York, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, N.W. Psicodinamica della vita familiare; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italia, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, K.; LaToya, B.V.; Barber, B.K. When there is conflict. Interparental conflict, parent-child conflict, and youth problem behaviors. J Fam Iss 2008, 29, 780–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, E. La strada della donna; Astrolabio: Roma, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Lebow, J.L. Integrative family therapy for families experiencing high-conflict divorce. In Handbook of Clinical Family Therapy, 1st ed.; Lebow, J.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New Jersey, US, 2005; pp. 516–542. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, M. The Resolution of Conflict: Constructive and Destructive Processes; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh, M.; Buckhalt, J.A.; Mize, J.; Acebo, C. Marital Conflict and Disruption of Children's Sleep. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, C.; Lange, G.; Franck, K.L. Adolescents' Cognitive and Emotional Responses to Marital Hostility. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.M.; Fosco, G.M. Family and individual risk factors for triangulation: Evaluating evidence for emotion coaching buffering effects. Fam. Process. 2021, 61, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, R.E. Interparental conflict and the children of discord and divorce. Psychol. Bull. 1982, 92, 310–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Cummings, E.M.; Harold, G.T.; Shelton, K.H. Categories and continua of destructive and constructive marital conflict tactics from the perspective of U.S. and Welsh children. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Papp, L.M.; Goeke-Morey, M.C. Children's Responses to Everyday Marital Conflict Tactics in the Home. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.H.; Barfoot, B.; Frye, A.A.; Belli, A.M. Dimensions of marital conflict and children's social problem-solving skills. J. Fam. Psychol. 1999, 13, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, K.; Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Constructive and destructive marital conflict, emotional security and children’s prosocial behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, C.; Welsh, D.P. A process model of adolescents' triangulation into parents' marital conflict: The role of emotional reactivity. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterbrooks, M.A.; Emde, R.N. Marital and parent-child relationships: The role of affect in the family system. In Relationships within families: Mutual influences, 2nd ed.; Hinde, R.A., Hinde, J.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York; NW, 1988, pp. 83-103.

- Sturge-Apple, M.L.; Davies, P.T.; Cummings, E.M. Impact of Hostility and Withdrawal in Interparental Conflict on Parental Emotional Unavailability and Children's Adjustment Difficulties. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 1623–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.T.; Myers, R.L.; Cummings, E.M. Responses of Children and Adolescents to Marital Conflict Scenarios as a Function of the Emotionally of Conflict Endings. MPQUA5 1996, 42(1), pp 1-21.

- Grych, J.H.; Fincham, F.D. Marital conflict and children's adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, L. Growing in divorced; Linden Press, 1983.

- Buehler, C.; Anthony, C.; Krishnakumar, A.; Stone, G.; Gerard, J.; Pemberton, S. Interparental Conflict and Youth Problem Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. J. Child Fam. Stud. 1997, 6, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.M. Interparental conflict and threat appraisal during adolescence: identifying sensitive periods of risk for psychological maladjustment, substance use, and diminished school adjustment. M. Sc. Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University. 2021. Available online: https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/files/final_submissions/24945.

- Annunziata, D.; Hogue, A.; Faw, L.; Liddle, H.A. Family Functioning and School Success in At-Risk, Inner-City Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotterer, A.M.; Hoffman, L.; Crouter, A.C.; McHale, S.M. A Longitudinal Examination of the Bidirectional Links Between Academic Achievement and Parent–Adolescent Conflict. J. Fam. Issues 2008, 29, 762–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, A.C.; Margolin, G. Family Conflict, Mood, and Adolescents' Daily School Problems: Moderating Roles of Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms. Child Dev. 2015, 86, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Roeser, R.W. Schools as Developmental Contexts During Adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Kern, M.L.; Vella-Brodrick, D.; Hattie, J.; Waters, L. What Schools Need to Know About Fostering School Belonging: a Meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 30, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P. Children and marital conflict. The impact of family dispute and resolution. Guilford: New York, NW, 1994.

- Pryor, J. The quiet face of parental conflict: Is silence really golden? A preliminary examination of emotional conflict and adolescent well-being. Proceeding of the National Council on Family Relations Annual Conference, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 2003, November.

- Wang, L.; Crane, D.R. The Relationship Between Marital Satisfaction, Marital Stability, Nuclear Family Triangulation, and Childhood Depression. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2001, 29, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S.Y.; Gu, M.; Synchaisuksawat, P.; Wong, W.W. The relationship between parent-child triangulation and early adolescent depression in Hong Kong: The mediating roles of self-acceptance, positive relations and personal growth. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 109, 104676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. Manuale diagnostico e statistico dei disturbi mentali. Raffaello Cortina: Milano, 2013.

- Bernet, W.; Wamboldt, M.Z.; Narrow, W.E. Child Affected by Parental Relationship Distress. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canevelli, F.; Lucardi, M. La mediazione familiare. Dalla rottura del legame al riconoscimento dell’altro; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Andolfi, M. Il bambino nella terapia familiare; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andolfi, M. La terapia familiare multigenerazionale: Strumenti e risorse del terapeuta; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Haley, J.; Hoffman, L. Tecniche di terapia della famiglia; Astrolabio: Roma, Italia, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin, S. Famiglie e terapia della famiglia; Astrolabio: Roma, Italia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, B.D. Parental alienation and the dynamics of the enmeshed parent-child dyad: adultification, parentification, and infantilization. Fam. Court. Rev. 2011, 49, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loriedo, C.; Picardi, A. Dalla teoria generale dei sistemi alla teoria dell’attaccamento. Percorsi e modelli della psicoterapia sistemico-relazionale. Franco Angeli: Milano, Italia, 2000.

- Pingitore, M. (Ed.) Nodi e snodi dell’alienazione parentale. Nuovi strumenti psicoforensi per la tutela dei diritti dei figli. Franco Angeli: Milano, Italia, 2019.

- Cigoli, V.; Galimberti, C.; Mombelli, M. Il legame disperante. Il divorzio come dramma di genitori e figli; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cigoli, V. Il patto infranto: Tipologie di divorzio e ritualità del passaggio. In La crisi di coppia: Una prospettiva sistemicco-relazionale; Andolfi, M., Ed.; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italia, 1999; pp. 397–429. [Google Scholar]

- Malagoli Togliatti, M.; Lubrano Lavadera, A. (Eds.) Bambini in tribunale: l’ascolto dei figli contesi. Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italia, 2011.

- Gardner, R.A. Recent trends in divorce and custody litigation. Academy Forum 1985, 29(2) pp. 3-7.

- Boszormenyi-Nagi, I.; Spark, G. M. Lealtà invisibili: La reciprocità nella terapia familiare intergenerazionale; Astrolabio: Roma, Italia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Boni, S. Separazioni conflittuali e minori. Profiling 2016, 7(2).

- De Renoche, I.; Della Giustina, L. Bambini dentro il contesto di separazione genitoriale; particolari risvolti del conflitto di lealtà. 2015, 3, 156–160. [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, D.; Doyle, A.B.; Brengdon, M. The quality of adolescents’ friendships: Associations with mothers’ interpersonal relationships, attachment to parents and friends, and prosocial behavior. J Adolesc. 2001, 24, pp. 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, C.; Franck, K.L.; Cook, E.C. Adolescents' Triangulation in Marital Conflict and Peer Relations. J. Res. Adolesc. 2009, 19, 669–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, P.M. A Dynamic-Maturational Model of Attachment. Aust. New Zealand J. Fam. Ther. 2006, 27, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, P.M. Raising Parents: Attachment, Parenting and Child Safety. Willan: Cullompton, UK, 2008.

- Dallos, R.; Vetere, A. Systems Theory, Family Attachments and Processes of Triangulation: Does the Concept of Triangulation Offer a Useful Bridge? J. Fam. Ther. 2011, 34, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.S.; Hinshaw, A.B.; Murdock, N.L. Integrating the Relational Matrix: Attachment Style, Differentiation of Self, Triangulation, and Experiential Avoidance. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2016, 38, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosco, G.M.; Grych, J.H. Adolescent Triangulation Into Parental Conflicts: Longitudinal Implications for Appraisals and Adolescent-Parent Relations. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, K.A. Children’s Responses to Interparental Conflict: A Meta-Analysis of Their Associations With Child Adjustment. Child Dev. 2008, 79, 1942–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, P.T.; Cummings, E.M. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggio, H.R. Parental marital conflict and divorce, parent-child relationships, social support, and relationship anxiety in young adulthood. Pers. Relationships 2004, 11, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, K.; Vaughn, L.B.; Barber, B.K. When There Is Conflict: Interparental conflict, parent-child conflict, and youth problem behaviors. J. Fam. Issues 2007, 29, 780–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilino, W.S. Impact of Childhood Family Disruption on Young Adults' Relationships with Parents. J. Marriage Fam. 1994, 56, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditti, J.A. Rethinking Relationships between Divorced Mothers and Their Children: Capitalizing on Family Strengths. Fam. Relations 1999, 48, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, T.M.; Hutchinson, M.K.; Leather, D.M. Surviving the Breakup? Predictors of Parent-Adult Child Relations after Parental Divorce. Fam. Relations 1995, 44, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, P.R.; Booth, A. Consequences of Parental Divorce and Marital Unhappiness for Adult Well-Being. Soc. Forces 1991, 69, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Amato, P.R. Parental Marital Quality, Parental Divorce, and Relations with Parents. J. Marriage Fam. 1994, 56, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, G.; Uhlenberg, P. Effects of Life Course Transitions on the Quality of Relationships between Adult Children and Their Parents. J. Marriage Fam. 1998, 60, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, T.M.; Uhlenberg, P. The Role of Divorce in Men's Relations with Their Adult Children after Mid-Life. J. Marriage Fam. 1990, 52, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, T.M.; Hutchinson, M.K.; Leather, D.M. Surviving the Breakup? Predictors of Parent-Adult Child Relations after Parental Divorce. Fam. Relations 1995, 44, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.; Dunlop, R. Parental divorce, parent–child relations, and early adult relationships: A longitudinal Australian study. Pers. Relationships 1998, 5, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, P.R.; Booth, A. The legacy of parents' marital discord: Consequences for children's marital quality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grych, J.H. Interparental conflict as a risk factor for child maladjustment: Implications for the Development of Prevention Programs. Fam. Court. Rev. 2005, 43, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M.; Bonds, D.; Sandler, I.; Braver, S. Parent psychoeducational programs and reducing the negative effects of interparental conflict following divorce. Fam. Court. Rev. 2004, 42, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuthnot, J.; Gordon, D.A. Does mandatory divorce education for parents work? Fam. Court. Rev. 1996, 34, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, H.E.; Sizemore, K.M.; Shideler, M.J.; LaGraff, M.R.; Moran, H.B. Parenting Together: Evaluation of a Parenting Program for Never-Married Parents. J. Divorce Remarriage 2017, 58, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchik, S.A.; West, S.G.; Westover, S.; Sandler, I.N.; Martin, A.; Lustig, J.; Tein, J.-Y.; Fisher, J. The children of divorce parenting intervention: Outcome evaluation of an empirically based program. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1993, 21, 293–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson-McClure, S.R.; Sandler, I.N.; Wolchik, S.A.; Millsap, R.E. Risk as a moderator of the effects of prevention programs for children from divorced families: a six-year longitudinal study. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2004, 32, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebow, J. Integrative family therapy for disputes involving child custody and visitation. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).