Submitted:

19 May 2023

Posted:

22 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

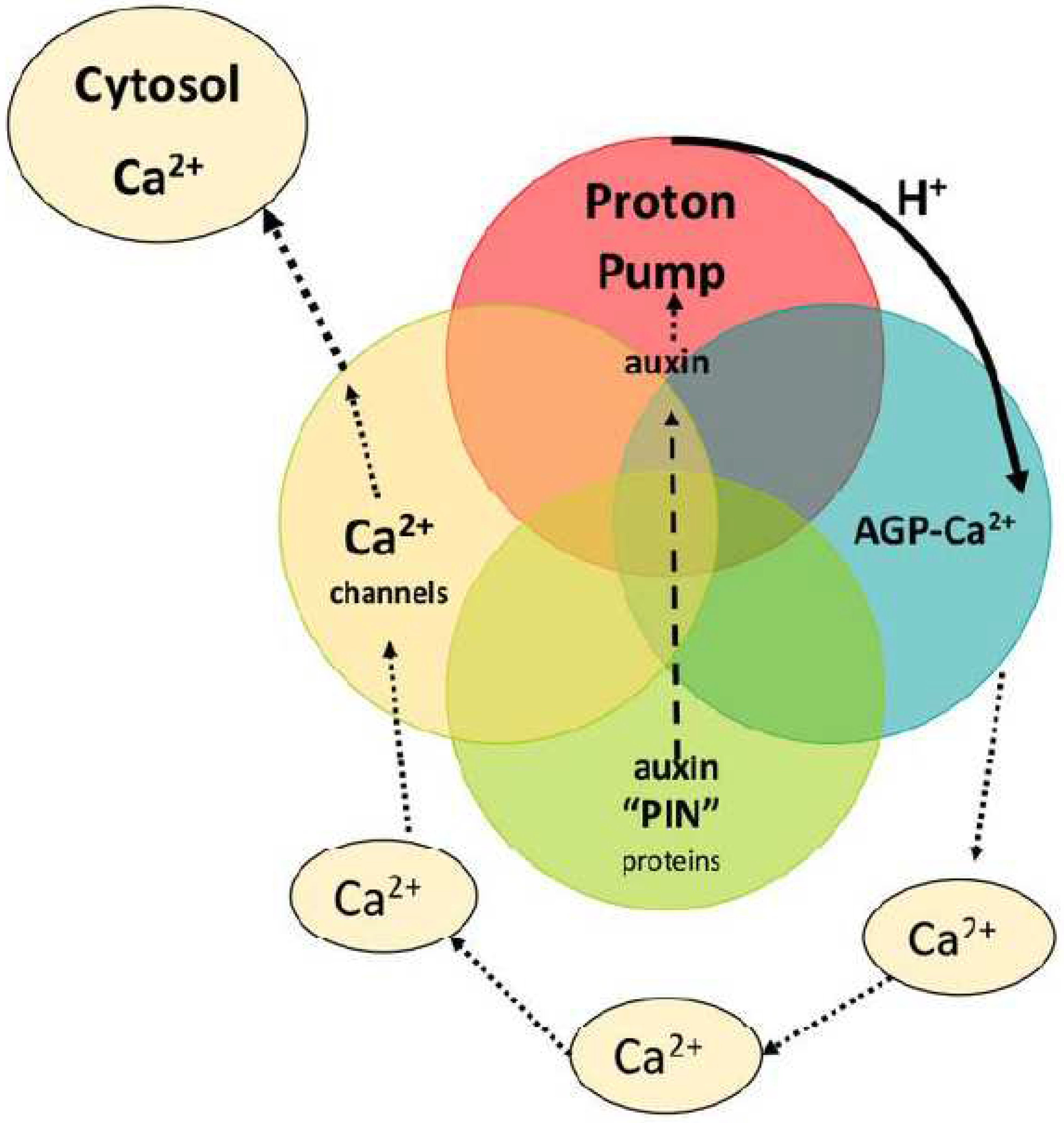

- Auxin efflux PIN proteins transport auxin

- Auxin activates proton pump to generate protons

- Protons release Ca2+ from AGP-Ca2+

- Open Ca2+ channels supply cytosolic Ca2+

Historical Back Ground

Simplicity

The Mathematical Basis

Cytosolic Ca2+: is AGP Glucuronic Acid the Source?

GlcAT Knockouts Affect Ca2+ Homeostasis

Pinball Machine is Random?

What Connects Auxin with Ca2+ Signaling?

Origin of Growth Oscillations and Ion Fluxes

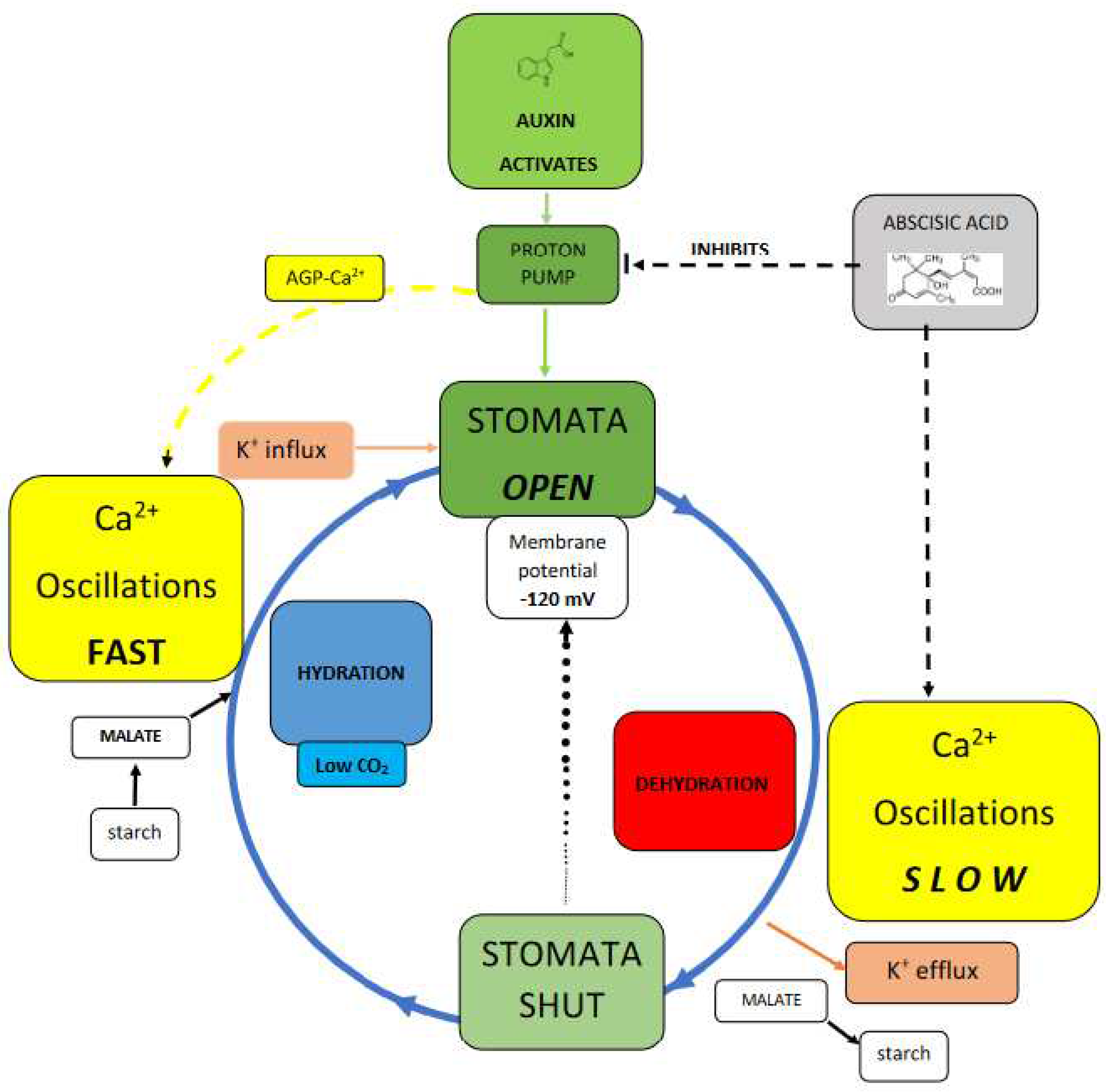

Stomata Test the Pinball Hypothesis

Final Conclusions

References

- Ng, C.K.-Y.; Mcainsh, M.R.; Gray, J.E.; Hunt, L.; Leckie, C.P.; Mills, S.; Hetherington, A.M. Calcium-based signalling systems in guard cells. New Phytol. 2001, 151, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.J.; Mehta, S.; Israelsson, M.; Godoski, J.; Grill, E.; Schroeder, J.I. CO2 signaling in guard cells: Calcium sensitivity response modulation, a Ca2+-independent phase, and CO2 insensitivity of the gca2 mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 163, 7506–7511. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.-H.; Bohmer, M.; Hu, H.; Nishimura, N.; Schroeder, J.I. Guard Cell Signal Transduction Network:Advances in Understanding Abscisic Acid, CO2, and Ca2+ Signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 561–591. [Google Scholar]

- Parramona, C.M.; Wang, Y.; Hills, A.; Vialet-Chabrand, S.; Griffiths, H.; Rogers, S.; Lawson, T.; Lew, V.L.; Blatt, M. An Optimal Frequency in Ca2+ Oscillations for Stomatal Closure Is an Emergent Property of Ion Transport in Guard Cells. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, P. David Keilin's Respiratory Chain Concept and Its Chemiosmotic Consequences. Nobel Lect. Chem. 1978, 1971–1980, 295–330. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.; Ferraz, R.; Dupree, P.; Showalter, A.M.; Coimbra, S. Three Decades of Advances in Arabinogalactan-Protein Biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 610377. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.; Varnai, P.; Lamport, D.T.A.; Yuan, C.; Xu, J.; Qiu, F.; Kieliszewski, M.J. Plant O-Hydroxyproline Arabinogalactans Are Composed of Repeating Trigalactosyl Subunits with Short Bifurcated Side Chains. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 24575–24583. [Google Scholar]

- Lamport, D.T.A.; Varnai, P. Periplasmic arabinogalactan glycoproteins act as a calcium capacitor that regulates plant growth and development. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Holdaway-Clarke, T.; Feijo, A.; Hackett, G.R.; Kunkel, J.G.; Hepler, P.K. Pollen Tube Growth and the lntracellular Cytosolic Calcium Gradient Oscillate in Phase while Extracellular Calcium Influx is Delayed. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1999–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mollet, J.C.; Kim, S.; Jauh, G.Y.; Lord, E.M. Arabinogalactan proteins, pollen tube growth, and the reversible effects of Yariv phenylglycoside. Protoplasma 2002, 219, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lamport, D.T.A.; Tan, L.; Held, M.A.; Kieliszewksi, M.J. The Role of the Primary Cell Wall in Plant Morphogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2674. [Google Scholar]

- Ringer, S. A further Contribution regarding the influence of the different Constituents of the Blood on the Contraction of the Heart. J. Physiol. 1883, 4, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Brewbaker, J.L.; Kwack, B.H. The essential role of calcium ion in pollen germination and pollen tube growth. Am. J. Bot. 1963, 50, 859–865. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge, M.J. Elementary and global aspects of calcium signalling. J. Physiol. 1997, 499, 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin-Tong, V.E. Signaling and the modulation of pollen tube growth. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 727–738. [Google Scholar]

- Very, A.-A.; Sentenac, H. Cation channels in the Arabidopsis plasma membrane. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Turing, A.M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Phil Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 1952, 237, 37–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.; Xu j Held, M.A.; Lamport, D.T.A.; Kieliszewski, M. Arabinogalactan Structures of Repetitive Serine-Hydroxyproline Glycomodule Expressed by Arabidopsis Cell Suspension Cultures. Plants 2023, 12, 1036. [Google Scholar]

- Hepler, P.K. The Cytoskeleton and Its Regulation by Calcium and Protons. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lamport, D.T.A.; Kieliszewski, M.J.; Showalter, A.M. Salt stress upregulates periplasmic arabinogalactan proteins: Using salt stress to analyze AGP function. New Phytol. 2006, 169, 479–492. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer, L.; Shafee, T.; Johnson, K.L.; Bacic, A.; Classen, B. Arabinogalactan-proteins of Zostera marina L. contain unique glycan structures and provide insight into adaption processes to saline environments. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8232. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer, L.; Classen, B. The Cell Wall of Seagrasses: Fascinating, Peculiar and a Blank Canvas for Future Research. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 588754. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Hernandez, F.; Tryfona, T.; Rizza, A.; Yu, X.L.; Harris, M.O.B.; Webb, A.A.R.; Kotake, T.; Dupree, P. Calcium Binding by Arabinogalactan Polysaccharides Is Important for Normal Plant Development. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3346–3369. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, O.O.; Held, M.A.; Showalter, A.M. Three β-Glucuronosyltransferase Genes Involved in Arabinogalactan Biosynthesis Function in Arabidopsis Growth and Development. Plants 2021, 10, 1172. [Google Scholar]

- Kapil, V.; Schran, C.; Zen, A.; Chen, J.; Pickard, C.J.; Michaelides, A. The first-principles phase diagram of monolayer nanoconfined water. Nature 2022, 609, 512–517. [Google Scholar]

- Irving, H.R.; Gehring, C.A.; Parish, R.W. Changes in cytosolic pH and calcium of guard cells precede stomatal movements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 1790–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Chater, C.; Kamisugi, Y.; Movahedi, M.; Fleming, A.; Cuming, A.C.; Gray, J.E.; Beerling, D.J. Regulatory Mechanism Controlling stomatal Behavior Conserved across 400 Million Years of Land Plant Evolution. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Vanneste, S.; Friml, J. Calcium: The missing link in auxin action. Plants 2013, 2, 650–675. [Google Scholar]

- Dindas, J.; Scherzer, S.; Roelfsema, M.R.G.; von Meyer, K.; Muller, H.M.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.S.; Palme, K.; Dietrich, P.; Becker, D.; Bennett, M.J.; Hedrich, R. AUX1-mediated root hair auxin influx governs SCFTIR1/AFB-type Ca2+ signaling. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1174. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, A.S.; Peer, W.A. An auxin-binding protein resurfaces after deep dive. Nature 2022, 609, 475–476. [Google Scholar]

- Baluska, F.; Mancuso, S. Root apex transition zone as oscillatory zone. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 354. [Google Scholar]

- Hepler, P.K. The Cytoskeleton and Its Regulation by Calcium and Protons. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, A.; Palmgren, M. Root hair growth from the pH point of view. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 949672. [Google Scholar]

- Habets, M.E.; Offringa, R. PIN-driven polar auxin transport in plant developmental plasticity: A key target for environmental and endogenous signals. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 362–377. [Google Scholar]

- Lamport, D.T.A.; Tan, L.; Held, M.A.; Kieliszewksi, M.J. Phyllotaxis Turns Over a New Leaf-A New Hypothesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jezek, M.; Blatt, M. The Membrane Transport System of the Guard Cell and Its Integration for Stomatal Dynamics. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 487–519. [Google Scholar]

- Parramona, C.M.; Wang, Y.; Hills, A.; Vialet-Chabrand, S.; Griffiths, H.; Rogers, S.; Lawson, T.; Lew, V.L.; Blatt, M. An Optimal Frequency in Ca2+ Oscillations for Stomatal Closure Is an Emergent Property of Ion Transport in Guard Cells. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.-H.; Bohmer, M.; Hu, H.; Nishimura, N.; Schroeder, J.I. Guard Cell Signal Transduction Network:Advances in Understanding Abscisic Acid, CO2, and Ca2+ Signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 561–591. [Google Scholar]

- Giannoutsou, E.; Apostolakos, P.; Galatis, B. Spatio-temporal diversification of the cell wall matrix materials in the developing stomatal complexes of Zea mays. Planta 2016, 244, 1125–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C.K.-Y.; Mcainsh, M.R.; Gray, J.E.; Hunt, L.; Leckie, C.P.; Mills, S.; Hetherington, A.M. Calcium-based signalling systems in guard cells. New Phytol. 2001, 151, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Falhof, J.; Pedersen, J.T.; Fuglsang, J.T.; Palmgren, M. Plasma Membrane H+ATPase Regulation in the Center of Plant Physiology. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peak, D.; Hogan, M.T.; Mott, K.A. Stomatal patchiness and cellular computing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2220270120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Battey, N.H.; James, N.C.; Greenland, A.J.; Brownlee, C. Exocytosis and Endocytosis. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Campanoni, P.; Blatt, R. Membrane trafficking and polar growth in root hairs and pollen tubes. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Day, I.S.; Reddy, V.S.; Ali, G.S.; Reddy, A.S.N. Analysis of EF-hand-containing proteins in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, 0056–1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.-H.; Hills, A.; Batz, U.; Amtmann, A.; Lew, V.L.; Blatt, M. Systems Dynamic Modeling of the Stomatal Guard Cell Predicts Emergent Behaviors in Transport, Signaling, and Volume Control. Plant Physiol. 2020, 159, 1235–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Inoue, S.; Kinoshita, T. Abscisic Acid Suppresses Hypocotyl Elongation by Dephosphorylating Plasma Membrane H+-ATPase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 845–853. [Google Scholar]

- Adem, G.D.; Chen, G.; Shabala, L.; Chen, Z.-H.; Shabala, S. GORK Channel: A Master Switch of Plant Metabolism? Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 434–445. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, B.; Munemasa, S.; Wang, C.; Nguyen, D.; Yong, T.; Yang, P.G.; Poretsky, E.; Waadt, R.; Aleman, F.; Schroeder, J.I. Calcium specificity signaling mechanisms in abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis guard cells. eLife 2015, 4, e03599. [Google Scholar]

- Lamport, D.T.A.; Tan, L.; Kieliszewksi, M.J. A Molecular Pinball Machine of the Plasma Membrane Regulates Plant Growth—A New Paradigm. Cells 2021, 10, 10081935. [Google Scholar]

- Lamport, D.T.A.; Northcote, D.H. Hydroxyproline in primary cell walls of higher plants. Nature 1960, 188, 665–666. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, M.C.; Terneus, K.A.; Hall, Q.; Tan, L.; Wang, Y.; Wegenhart, B.; Chen, L.; Lamport, D.T.A.; Chen, Y.; Kieliszewksi, M.J. Self-assembly of the plant cell wall requires an extensin scaffold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2226–2231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lamport, D.T.A.; Tan, L.; Held, M.A.; Kieliszewski, M.J. Root-shoot gravitropism paradox resolved. Acad. Lett. 2022, 2022, 4998. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).