1. Introduction

An illness known as gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes uncomfortable symptoms and/or problems. By affecting the lower esophageal sphincter, momentarily loosening it, clearing esophageal acid, and postponing stomach emptying, a hiatus hernia may contribute to the pathogenesis of esophageal syndrome [

1]. Pharmacologic acid suppression has typically been used to treat GERD, albeit up to 50% of patients experience little to no relief from it. As we understand more about the pathophysiology and etiologies of GERD, we can see that the disease progresses in ways that go beyond how acidic the refluxate is. Refluxate composition and esophageal factors like structural, mechanical, biochemical, and physiological aspects can both affect how symptoms present themselves and how they respond to therapy [

2] Depending on where you reside, the disease's prevalence can range from a few to more than 30% of the adult population. According to global estimates, up to 35.5% of adults in Poland, for example, who report experiencing abdominal pain may have this illness. If the condition is not treated, it may worsen and lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma and other severe complications. Patients with GERD are typically treated with pharmacotherapy, but more importantly, lifestyle modifications, including dietary adjustments, are crucial to the disease's management. Many factors may play a part in the disease's emergence. There are both modifiable and non-modifiable factors, such as lifestyle, nutrition, and excessive body weight. Non-modifiable factors include age, gender, and genetics. Excessive body weight, especially obesity, moderate/high alcohol intake, smoking, postprandial and vigorous physical activity, and a lack of regular physical activity are all risk factors for GERD symptoms. Many studies have connected nutritional factors such as fatty, fried, sour, and spicy foods/products, orange and grapefruit juice, tomatoes and tomato preserves, chocolate, coffee/tea, carbonated beverages, and alcohol to GERD symptoms. This partially includes eating patterns like irregular mealtimes, consuming a lot at once, and eating right before sleep may be linked to GERD symptoms.

The findings of the studies that are currently accessible frequently conflict, making it unclear how lifestyle, diet, and eating habits play a role in GERD risk. It is essential to identify modifiable risk factors for this disease and its symptoms in order to adopt effective dietary prevention and [3 ] diet therapy of GERD. Therefore, GERD and IBD are becoming significant health issues globally. Several global societies are formulating treatment, guidelines, and management of both pediatric and adult GERD and IBD incidences and their psychiatric consequences. For instance, these included North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN 2019) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN 2019) (Rosen et al., 2018). Albeit similar surveillance and recommendations are scarce in the Middle Eastern Countries. Thus, the occurrence rates and stimulants are still not yet clear in the Middle Eastern populations including Saudi Arabia. Regular surveillance for understanding the diseases is limited.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a chronic digestive functional disorder. Constipation (IBS-C), diarrhea (IBS-D), or both gastrointestinal discomfort and altered bowel patterns are the most common gastrointestinal symptoms reported by patients. Because there has not been a conclusive study and no biomarker has been found, IBS continued to be diagnosed clinically. Although the disease is still largely a mystery, the turn of the 20th and 19th centuries is when the earliest IBS reports first appeared. Identification was made at this time only following a comprehensive investigation and "extensive failed operations" to rule out infectious, inflammatory, or malignant disease. The IBS was and still "often misdiagnosed and poorly understood" since early 1970s, and the problem of ineffective or unnecessary surgery persists till today [

4]. The IBS disease affects between much more than 5% and 20% of people worldwide, depending of geographical regions, and their lifestyles, as indicated by widely known global surveillance programs of study. However, the prevalence of IBS in the Gulf countries and African is still not yet fully understood due to lack of high quality surveillance data. In Saudi Arabia the recorded rates vary, although a rate of around 14.4% is recorded. This IBS records were predicted by food hypersensitivity, morbid anxiety, and family history [

5]. For these incidences, the gastroenterology clinics have received referrals for 30% to 50% of IBS cases. A thorough review of the patient's symptoms, a thorough nutritional history (including diet contents and types) and medications, medical, surgical, and psychological history, an evaluation of the patient for the presence of cautionary indicators (such as "red flags" of anemia, hematochezia, unintentional weight loss, or a family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease), and a guided physical examination are all necessary for the traditional diagnosis of IBS[

6].

There are several clues on the close association of GERD, IBD, and psychiatric coexistence and consequences, albeit these relationships have not been widely established for the differences in global population structures. However, up to 79% of IBS sufferers experience symptoms of gastric reflux disease (GERD), and 71% of GERD sufferers experience symptoms of IBS (IBS). There are two main potential theoretical reasons explaining why GERD patients frequently experience IBS symptoms. The first hypothesis states that a sizable proportion of patients have both GERD and IBS. The second hypothesis proposes that the range of GERD manifestations includes IBS-like symptoms. A general gastrointestinal disorder that affects smooth muscle or sensory afferents may be the cause of the first hypothesis, which is supported by genetic studies and similarities in gastrointestinal sensory-motor abnormalities. Studies demonstrating a reduction in IBS-like symptoms in GERD patients receiving anti-reflux therapy primarily lend support to the alternative hypothesis. The close connection between GERD and IBS may be explained by GERD's impact on various GI tract levels or by GERD and IBS' high overlap rate caused by similar GI dysfunction [

7]. In the same way that mental health deterioration and psychiatric disorders can negatively affect treatment outcomes. The GERD can both create and exacerbate mental complications in patients. Low doses of antidepressants and anxiety medications have been shown in studies to be helpful in treating such conditions. Therefore, it is crucial to look into how these variables affect each other's prevalence in GERD patients [

8].

Significant evidences exists in the coexistence and associations of GERD and IBD syndromes and their aggravation by psychiatric consequences. The mechanisms underlying severity, complications, and outcomes of this triad is not yet fully understood. According to a study conducted by Sibelli et al. 2016, the risk of developing IBS was double for anxiety cases at baseline compared to those who were not. In the aforementioned study, depression yielded comparable results[

9]. Anxiety and depression have been shown in prospective studies to double the risk of subsequent IBS, but this risk factor is only found in one-quarter of people who develop IBS. This clearly indicates that the vast differences in global populations as well as differences among people in a population determine the ultimate nature of the triad disorders. Thus, psychiatric disorders do not precede three-quarters of IBS onsets, and other risk factors must be important in these people. Individuals who have psychiatric disorders prior to IBS onset may be considered a subgroup of IBS sufferers with a different pattern of etiological factors than the rest, but no previous research has addressed this issue [

10]. IBS patients who are anxious or depressed have more severe gastrointestinal symptoms and a lower quality of life, according to the literature. [

11]. The link between IBS and emotional and physical abuse is less clear in the literature than the link between IBS and sexual abuse [

12]. In Northern Saudi Arabia, anxiety and depression were found to be significantly associated with IBS. However, this association was only investigated based on patients' self-reports of anxiety, depression, or both [

5]. A study that included 6476 patients, 3185 (49.2%) men and 3291 (50.8%) women, suggests that there is a significant overlap between GERD and IBS, with a remarkable predominance in women; it also points to the association of upper gastrointestinal symptoms with IBS in patients suffering from both GERD and IBS, particularly nausea and vomiting, with a significant trend toward affecting women [

13]. According to the literature, the prevalence of GERD and IBS in the Iranian population is comparable to that reported in Western countries.

Gender differences in the incidence and prevalence rates of GERD, IBS, and psychiatric disorder triad is of a paramount significance in the management of the disease and treatment options. More research is needed to determine the cause of the increased prevalence of these complaints in women [

14]. There is some evidence, though it is limited and preliminary, of a link between functional heartburn (FH) and IBS. Some studies have found that FH and IBS may share common pathophysiological mechanisms, such as visceral hypersensitivity, and that drugs that act as visceral pain modulators (such as antidepressants) may benefit both disorders when tested separately [

15]. He et al. conducted a systematic review with meta-analysis and discovered a significant positive association between psychosocial disorders and GERD[

16].

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

Cross-sectional descriptive study design. The design will be based on a comprehensive online questionnaire sent out to different regions of Saudi Arabia to understand the regional causes, if any, of any or all of these disorders in the country. This study will be descriptive analysis and stratified; we will present absolute numbers, proportions, and graphical distributions. We will conduct exact statistical tests for proportions and would show p-values where appropriate (a p-value <0.05 will be considered statistically significant). The test used in these will be Chi-square test analysis for significance as explained below.

Study population

The sample will be taken from the adults 18 years old and over in different regions of Saudi Arabian provinces.

Inclusion Criteria:

Adult populations 18 years of age from either gender living in Saudi Arabia and has never been out of the country for extended periods at the time of the development of any of these disorders. Any participant experienced any of these syndromes outside of Saudi Arabia will be excluded form the study. Any participant under 18 years of age will be also excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis of the data

Data analysis

The data were collected, reviewed and then fed to Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 21 (SPSS: An IBM Company). All statistical methods used were two tailed with alpha level of 0.05 considering significance if P value less than or equal to 0.05. Descriptive analysis was done by prescribing frequency distribution and percentage for study variables including participants personal data, employment, frequency of coexistence of the triad disorders, disease tirade stimulant and Potential link between GERD or IBS and anxiety/depression. Cross tabulation for showing Factors associated with disease tirade among study participants and distribution of the disease's tirade by their onset of diagnosis using Pearson chi-square test for significance and exact probability test if there were small frequency distributions (P: Pearson X2 test; $: Exact probability test ).

3. Results

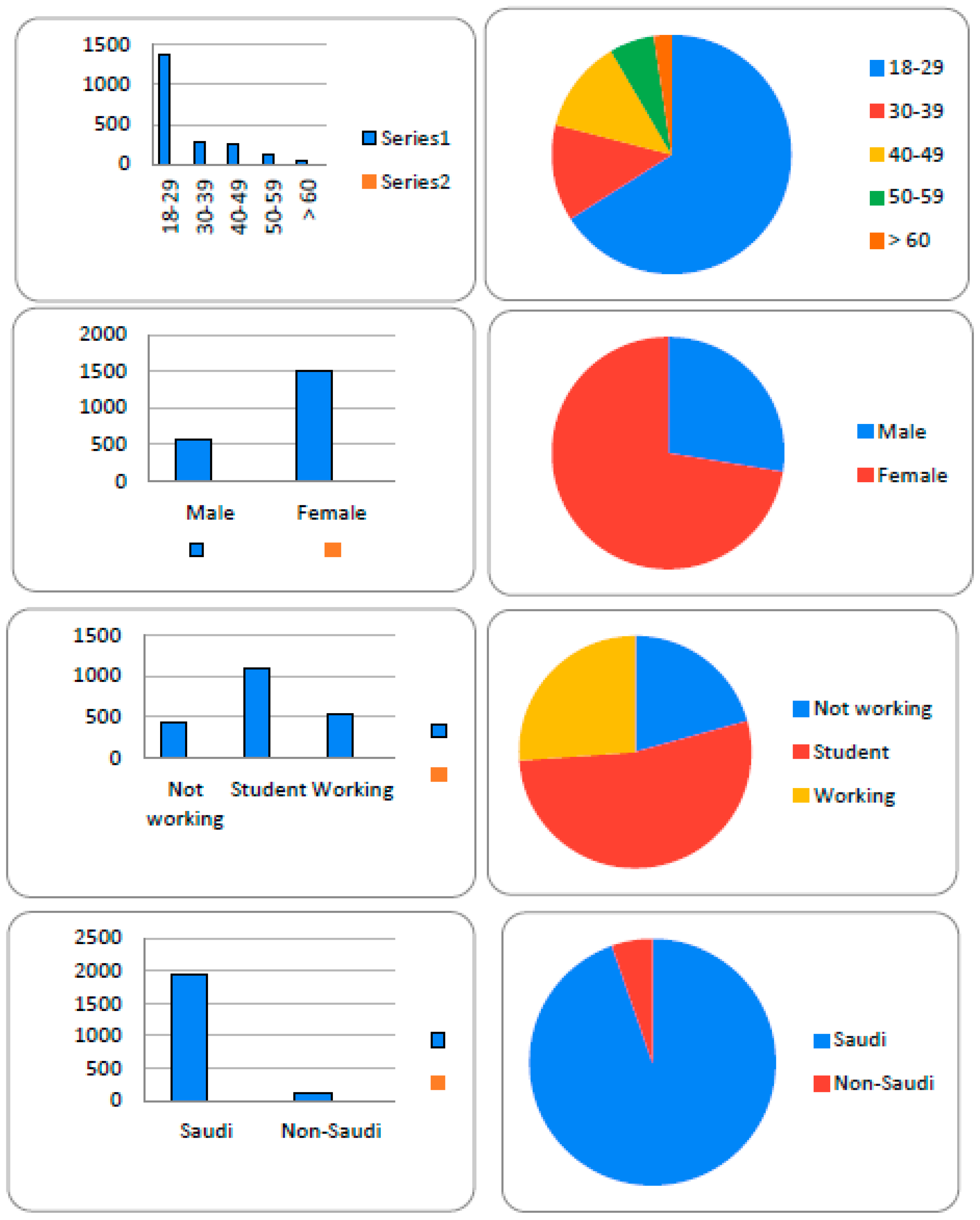

A total of 2067 participants completed the study questionnaire. As shown in

Figure 1 (a, b, c, and d); participants’ ages ranged from 18 to more than 60 years with mean age of 26.8 ± 12.9 years old. These were as follows: the most age group participated was 18 -29 years old (66%, n=1364) and the overwhelming majority of participants were young Saudi females (72.4%, n=1496) while male participants were 26.7% (n=571). Based on employment status, a total of 1099 (53.2%) were students, 428 (20.7%) were not working, and 540 (26.1%) were employed. The majority were Saudi nationals (94.7%, n= 1957) while only 5% (n=110) were not Saudis (

Figure 1 a,b,c, and d). The disease triad frequency of coexistence, time of start, aggravating factors, and treatment options are shown in

Table 1. The triple psychological syndromes of anxiety (60.7%), stress (60.7%), and depression (60.6%) were the most frequent (averaged 60.7); whereas, IBD (48.7%) and GERD (36.3%), respectively were the second and third prevalent, respectively. Other symptoms occurred very limited and non-significantly. With respect to the first occurrence, an average of 51 % of respondents reported that they had the related sings of depression, anxiety, and stress first while 33.9%, and 24.3% reported IBD and GERD, respectively, were the first signs that show up. In most respondents (59.2%, n=1178), these signs first appeared recently and 33.6% (n=669) reported occurrence during adult life, and only in 7.2% (n=144) the signs noticed during childhood (7.2%, n=144)).

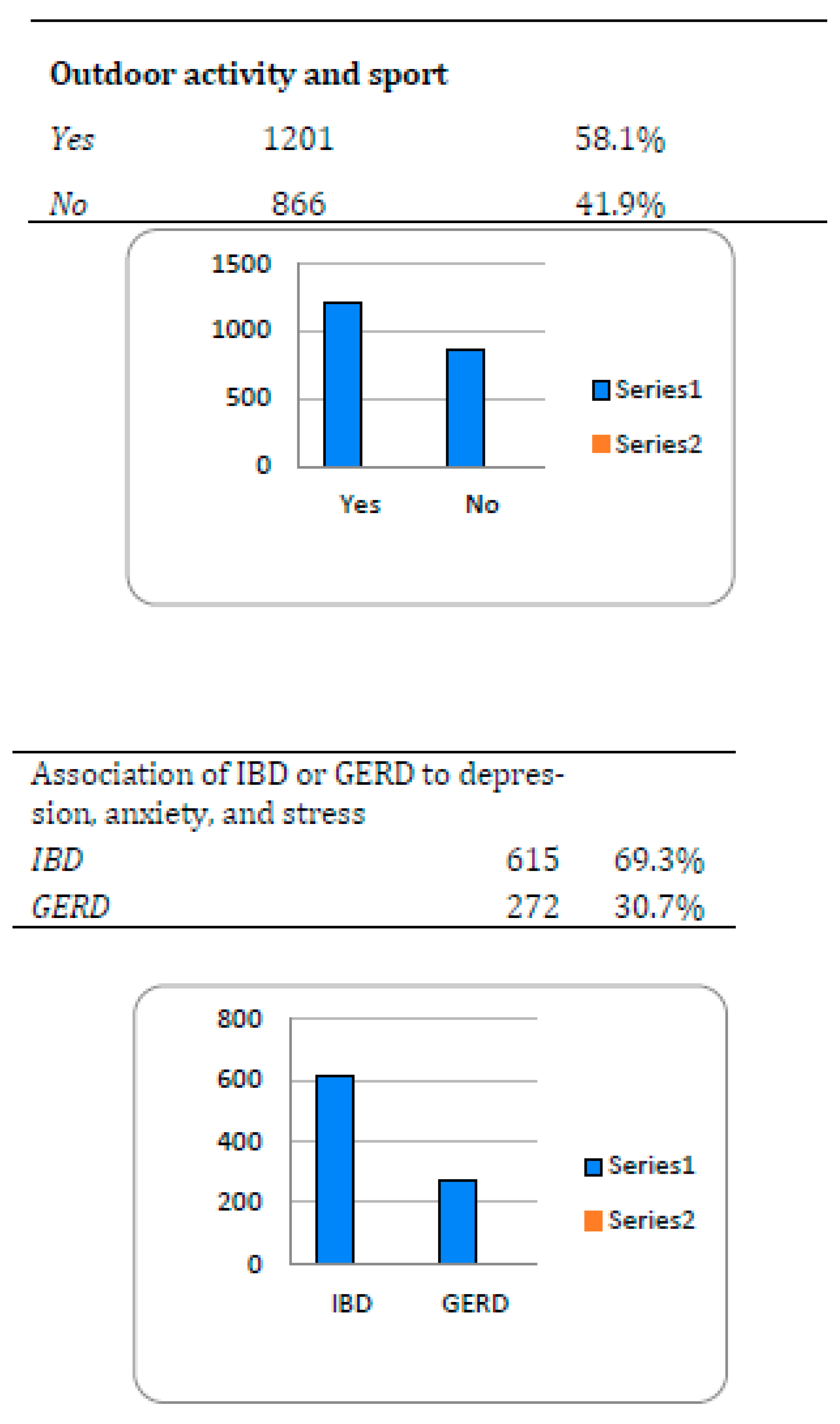

In this study, aggravating factors examined showed different types. For instance, 32.9% (n=681) respondents acknowledge genetic and other aggravating factors for the diseases. Among these, a total of 476 (69.9%) came from family genetic history for IBD followed by 215(31.6%) and 175 ((25.7), respectively, had genetically inherited the triple syndrome (depression, anxiety, and stress) and GERD. However, about 18.3% sought treatment (n=378) where only 66 (3.2%) of these had procedures such as colectomy or a colostomy bag. Little over half of the studied population (58.1%, n=1201) played sports or were active in outdoor activities (Figure 3). With respect to potential risk of association between GERD or IBS and psychological factors (anxiety, depression, and stress) in Saudi population; 42.9% (n=887) developed depression, anxiety, stress signs when they have had gastroesophageal reflux diseases; of which 69.3% noticed after IBD and 30.7% after GERD (Figure 3).

Demographic factors associated with the disorders studied among study participants, female respondents were more likely to get these condition(s) at 72.4%(n=1496) compared to 27.6% males (n=571). Age increment breakdown showed that 66%(n=1364) were young at age range between 18-29 years while 13% and 12.5% were between age ranges (30-39) and 40-49), respectively. Seniors aged 50-59 and over 60 were the least frequent responders at 6% and 2%, respectively. Age- and gender-specific associations of GERD, IBD, and psychological disorders among populations was in the current study (

Table 2 and

Table 3). For instance, GERD was more prevalent among old age participants, IBD was more common among those aged 40-49 years, and psychological disorders among younger age participants with recorded statistical significance (P value =.001). On the distribution of the disease's tirade by their time of onset and diagnosis, most disease tirade appeared recently or during adulthood. A total of 59.9% of GERD started recently, compared to about 57.8% of psychological disorders and 54.4% of IBD (P=.002) (

Table 3). However, gender-specific analysis revealed that psychological disorders and IBD were more common among females; whereas, GERD was frequent among males with significant differences (P=.001). Similarly, IBD was significantly higher among workers and others than among students while psychological disorders were more frequent among students (P=.001). Others factors including habits, surgical history and nationality were insignificantly associated with disease tirade.

4. Discussion

This comprehensive study addressed a fundamental issue in one of the rapidly rising chronic disorders, the neurogastroenterology, in this region, and has laid a solid foundation in understanding its frequency, complications, and factors. Since these are typical millennial responses to high demanding life endeavors, it creates a mixed perception. These were primarily young Saudi females (72.4%, n=1496) students (1099 (53.2%) between ages of 18-29 years compared to 26.7% (n=571) males implying impact of an array of challenges including IT, OMICS, pandemics, …etc. However, while millennial response across the global shares a common theme; intriguingly, this study reveals a unique scenario in this region. For instance, while in US and UK diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, and obesity were reported irrespective of gender [

17,

18,

19], age-, and gender-specific neurogastroenterology syndromes such as IBD, GERD, anxiety, depressions, and stress were common in young females. However, the disease triad frequency of coexistence, time of start, aggravating factors, and treatment options were quite consistent with stimulating factors. For instance, psychological syndromes of anxiety (60.7%), stress (60.7%), and depression (60.6%) were the most frequent (averaged 60.7); whereas, IBD (48.7%) and GERD (36.3%), respectively were the second and third prevalent, respectively. In addition, consistent with this, the majority developed sings of depression, anxiety, and stress first and were mostly encountered recently (59.2%, n=1178) in their lifestyle. This leads to an important question that has become a theme for this generation [

20]; do they overthink and so loose diligence and creativity? Nevertheless, they would benefit from tailored direction, treatment, and understanding that will go a long way in shaping and building a stronger future[

21,

22,

23].

In this study, we report on significantly lower awareness, attention, and treatment to the aggravating factors for the disorders studied. This was also supported by the significant paucity in high quality data in this region and recommendations made by others for increased education [

24]. For example, while 32.9% (n=681) had genetic and other aggravating factors of whom 476 (69.9%) inherited IBD followed by 215(31.6%) and 175 (25.7) for psychological and GERD, respectively, only 18.3%, (n=378) sought treatment. Furthermore, too late realization and interventions were evident in the low rates (3.2%) who had procedures such as colectomy or a colostomy bag at later stage of the disease. Understanding cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy were found significantly reducing depression and anxiety symptoms in patients in Ontario, Canada and elsewhere [

25,

26].

Little over half of the studied population (58.1%, n=1201) played sports or were active in outdoor activities (Figure 3). With respect to potential risk of association between GERD or IBS and psychological factors (anxiety, depression, and stress) in Saudi population; 42.9% (n=887) developed depression, anxiety, stress signs when they have had gastroesophageal reflux diseases; of which 69.3% noticed after IBD and 30.7% after GERD (Figure 3). Sedentary time and reduced physical activity are associated with multiple adverse health conditions including oesophageal adenocarcinoma in different countries including China and UK [

27]. However, adjustment for a healthy threshold specific to the patient or population structure is imperative to avoid adverse outcomes as reported by others [

28,

29].

Among the demographic factors associated with the disorders showed that female respondents were more likely than male counterparts with 72.4%(n=1496) compared to 27.6% males (n=571). Age groups indicated that 66%(n=1364) were young between 18-29 years while only 13% and 12.5% were (30-39) and 40-49), respectively. Seniors aged 50-59 and over 60 were the least frequent responders at 6% and 2%, respectively. These findings indicate age and gender-specific associations of GERD, IBD, and psychological disorders among populations. For instance, GERD was more prevalent among old age participants, IBD was more common among age groups 40-49 years, and psychological disorders among younger age participants with recorded statistical significance (P value =.001). It is intriguing that despite significant differences in population genetic structures, lifestyles, and nutritional aspects at different geographic regions, this pattern remains similar to reports from global communities including Korea [

30], Palestine [

31], USA [

32,

33], UK [

34], China [

35]. This common syndrome is consistent with the widely established scientific notion that the gut nerve cells we’re born with are the same ones we die with. More importantly, a specific set of microbial populations are in-balance that defines homo-sapiens. This has been well established and continuously updated; particularly, in the human gut as a source for vertical transmission into newborn babies. In a global concert, a recent report identified conserved set of bacterial taxa in the healthy human gut microbiota worldwide that has a conserved role in metabolic across human populations, despite apparent lifestyle differences36. For instance, predominant shared microbial responses in various diseases and a specific inflammatory bowel disease signal [

37]. the role of balanced gut microbiome, the human-signatures, has been found play significant roles in shaping and regulating gut neurons and structure [

38]. For instance, microbiome signatures have been found to reduce stress [

39]. Moreover, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) remains as one of the prominent disorders with significant changes in the gut microbiome composition and without definitive treatment [

40]. The recent appearance of GERD (59.9%), psychological disorders (57.8%) and IBD (54.4%) with highly significant difference (P=.002) is potentially COVID-19 pandemic consequence. Persistent alterations in the fecal microbiome during the time of the pandemic [

41]. The altered gut microbiome was found due to the consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection leading to systemic host immunity and the gut milieu [

42]. These changes are potentially associated with changes in hormones, stress, and anxiety. This explains gender-specific syndromes in psychological disorders and IBD which were more common among young females and GERD was frequent among males with significant differences (P=.001).

5. Conclusion

We report on age-, and gender-specific neurogastroenterology syndromes of IBD, GERD, and mental health issues such as anxiety, depressions, and stress in primarily young Saudi women. In these mostly student millennial, psychological disturbances appeared first that predisposed to neurogastroenterology. The GERD was more prevalent among old age while IBD was more common in mid-age groups. Intriguingly, despite the significantly mosaic genetic population structures of different countries, their lifestyles, and nutritional habits, the pattern of these disorders remains similar to reports from global communities. This is quite evident in Saudi population as one of the most uniform genetic populations. Thus, the common human-syndrome is consistent with the widely established scientific notion that the gut nerve cells we’re born with are the same ones we die with. A potential reason is the factors leading to dysbiosis gut microbiome signatures. This is clearly exemplified by the altered gut microbiome post-covid-19 and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Unfortunately, there is significantly lower awareness on the disorders and their aggravating factors such as reduced physical activity, patterns of inheritance and the treatment opportunities which are also supported by the significant paucity in high quality published data in this region. Populations would benefit from recommendations of tailored educational and awareness programs.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Scientific Research Deanship at the University of Ha’il-Saudi Arabia through the proje.ct number RG20064.

Auothor contributions

Conceptualization, Ahmed Alsolami and Kamaleldin Said; Data curation, Ahmed Alsolami, Ziyad A. Melibari, Yaseer Alharbi, Ali Almutlag, Rana Aboras, Fayez Saud Alreshidi, Anas Fathuddin, Fawwaz Alshammari, Fawaz Alrashid, Sara Osman and Kamaleldin Said; Formal analysis, Ahmed Alsolami, Ziyad A. Melibari, Yaseer Alharbi, Ali Almutlag, Rana Aboras, Fayez Saud Alreshidi, Anas Fathuddin, Fawwaz Alshammari, Fawaz Alrashid, Sara Osman and Kamaleldin Said; Funding acquisition, Ahmed Alsolami and Kamaleldin Said; Investigation, Ahmed Alsolami and Kamaleldin Said; Methodology, Ahmed Alsolami, Ziyad A. Melibari, Yaseer Alharbi, Ali Almutlag, Rana Aboras, Fayez Saud Alreshidi, Anas Fathuddin, Fawwaz Alshammari, Fawaz Alrashid, Sara Osman and Kamaleldin Said; Project administration, Ahmed Alsolami and Kamaleldin Said; Resources, Ahmed Alsolami, Ziyad A. Melibari, Yaseer Alharbi, Ali Almutlag, Rana Aboras, Fayez Saud Alreshidi, Anas Fathuddin, Fawwaz Alshammari, Fawaz Alrashid, Sara Osman and Kamaleldin Said; Software, Ahmed Alsolami, Ziyad A. Melibari, Yaseer Alharbi, Ali Almutlag, Rana Aboras, Fayez Saud Alreshidi, Anas Fathuddin, Fawwaz Alshammari, Fawaz Alrashid, Sara Osman and Kamaleldin Said; Supervision, Ahmed Alsolami and Kamaleldin Said; Validation, Ahmed Alsolami, Ziyad A. Melibari, Yaseer Alharbi, Ali Almutlag, Rana Aboras, Fayez Saud Alreshidi, Anas Fathuddin, Fawwaz Alshammari, Fawaz Alrashid, Sara Osman and Kamaleldin Said; Visualization, Ahmed Alsolami, Ziyad A. Melibari, Yaseer Alharbi, Ali Almutlag, Rana Aboras, Fayez Saud Alreshidi, Anas Fathuddin, Fawwaz Alshammari, Fawaz Alrashid, Sara Osman and Kamaleldin Said; Writing – original draft, Ahmed Alsolami and Kamaleldin Said; Writing – review & editing, Ahmed Alsolami, Ziyad A. Melibari, Yaseer Alharbi, Ali Almutlag, Rana Aboras, Fayez Saud Alreshidi, Anas Fathuddin, Fawwaz Alshammari, Fawaz Alrashid, Sara Osman and Kamaleldin Said.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The standard guidelines were followed during this research according to the IRB protocols. The ethical application for this study was reviewed and (Approved) by the Research Ethics Committee (REC at the University of Ha’il (KSA), dated 22/10/2020 and endorsed by University President letter number Nr. 13675/5/42 dated 08/03/1441 H; for Deanship Project RG20064, REC# H-2020-187, and H-2021-212. The KACST Institutional Review Board (IRB) registration numbers are H-8-L-074 IRB log 2021-11 that also Approved the projects of this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in the manuscript, additional files are attached along with this submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The ethical application for this study was reviewed and (Approved) by the Research Ethics Committee (REC at the University of Ha’il (KSA), dated 22/11/2020 and H-2021-212. The KACST Institutional Review Board (IRB) registration numbers are H-8-L-074 IRB log 2021-11 that also Approved the projects of this study.

References

- Oshima, T.; Miwa, H. Pathogenesis of Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease. Nihon Rinsho 2007, 65, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Yadlapati, R. Pathophysiology and Treatment Options for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Looking beyond Acid. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2021, 1486, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taraszewska, A. Risk Factors for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptoms Related to Lifestyle and Diet. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 2021, 72, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, M.H.; Alhazmi, A.H.; Ujaimi, M.H.; Alsarei, M.; Alafifi, M.M.; Baalaraj, F.S.; Shatla, M.; Alharbi, M.H.; Alhazmi, A.H.; Sr. , M.H.U.; السريعي, م.; Alafifi, M.M.; Baalaraj, F.S.; Sr., M.S. The Prevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Its Relation to Psychiatric Disorders Among Citizens of Makkah Region, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.H.; Alateeq, F.A.; Alshammari, K.I.; Alshammri, A.S.S.; Alabdali, N.A.N.; Alsulaiman, M.A.S.; Algothi, S.M.I.; Altoraifi, A.S.; Almutairi, M.Q.; Ahmed, H.G.; Alharbi, S.H.; Alateeq, F.A.; Alshammari, K.I.; Alshammri, A.S.S.; Alabdali, N.A.N.; Alsulaiman, M.A.S.; Algothi, S.M.I.; Altoraifi, A.S.; Almutairi, M.Q.; Ahmed, H.G. Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Dietary Habits in Northern Saudi Arabia. Health N Hav 2019, 11, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Mohammed Alshahrani, S.S.; Abdulmajid Bin Rakhis, R.; Bishan Awad khalban, A.; Aouda Alshahrani, N.S.; Hassan Hussian Al-Rashdi, M.; Hassan Hatshan Alqarni, A.; Mana Alqhtani, M.S.; Abdulrahman Almehery, K.; Ali Alhadeer, S.; Ali Alshehri, A.; Mahdi Ali Alamry, A.; Ahmed Ali AlMassaud, H.; Ayidh Alasiri, A.A.; Saeed Alasmary, A. Prevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Functional Dyspepsia and Their Overlap in Saudi Arabia. bahrainmedicalbulletin.com 2023, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Gasiorowska, A.; Poh, C.H.; Fass, R. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)--Is It One Disease or an Overlap of Two Disorders? Dig Dis Sci 2009, 54, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadi, S.A.H.S.; Shafikhani, A.A. Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disorder. Electron Physician 2017, 9, 5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibelli, A.; Chalder, T.; Everitt, H.; Workman, P.; Windgassen, S.; Moss-Morris, R. A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of the Role of Anxiety and Depression in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Onset. Psychol Med 2016, 46, 3065–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, F. Risk Factors for Self-Reported Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Prior Psychiatric Disorder: The Lifelines Cohort Study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2022, 28, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midenfjord, I.; Polster, A.; Sjövall, H.; Törnblom, H.; Simrén, M. Anxiety and Depression in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Exploring the Interaction with Other Symptoms and Pathophysiology Using Multivariate Analyses. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2019, 31, e13619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sansone, L.A. IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME: Relationships with Abuse in Childhood. Innov Clin Neurosci 2015, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yarandi, S.S.; Nasseri-Moghaddam, S.; Mostajabi, P.; Malekzadeh, R. Overlapping Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Increased Dysfunctional Symptoms. World J Gastroenterol 2010, 16, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massarrat, S.; Saberi-firoozi, M.; Soleimani, A.; Himmelmann, G.; Hitzges, M.; Keshavarz, H. Peptic Ulcer Disease, Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Constipation in Two Populations in Iran. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995. [Google Scholar]

- de Bortoli, N.; Martinucci, I.; Bellini, M.; Savarino, E.; Savarino, V.; Blandizzi, C.; Marchi, S. Overlap of Functional Heartburn and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2013, 19, 5787–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wang, Q.; Yao, D.; Li, J.; Bai, G. Association Between Psychosocial Disorders and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2022, 28, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudoin, C.E.; Hong, T. Predictors of COVID-19 Preventive Perceptions and Behaviors Among Millennials: Two Cross-Sectional Survey Studies. J Med Internet Res 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagener, A.; Stassart, C.; Etienne, A.M. At the Peak of the Second Wave of COVID-19, Did Millennials Show Different Emotional Responses from Older Adults? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinson, M.L.; Lapham, J.; Ercin-Swearinger, H.; Teitler, J.O.; Reichman, N.E. Generational Shifts in Young Adult Cardiovascular Health? Millennials and Generation X in the United States and England. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2022, 77 (Suppl 2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corgnet, B.; Espín, A.M.; Hernán-González, R. Creativity and Cognitive Skills among Millennials: Thinking Too Much and Creating Too Little. Front Psychol 2016, 7, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gabalawy, R.; Sommer, J.L. “We Are at Risk Too”: The Disparate Mental Health Impacts of the Pandemic on Younger Generations: Nous Sommes Aussi à Risque: Les Effets de La Pandémie Sur La Santé Mentale Des Générations Plus. Can J Psychiatry 2021, 66, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzotto, N.; Marciano, L.; de Bruijn, G.J.; Schulz, P.J. The Empowering Role of Web-Based Help Seeking on Depressive Symptoms: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, R.; Spaccarotella, K.; Quick, V.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Generational Differences: A Comparison of Weight-Related Cognitions and Behaviors of Generation X and Millennial Mothers of Preschool Children. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshaikh, O.M.; Alkhonain, I.M.; Anazi, M.S.; Alahmari, A.A.; Alsulami, F.O.; Alsharqi, A.A. Assessing the Degree of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Knowledge Among the Riyadh Population. Cureus 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.H.; Zhang, J.Z.; Jin, S.Y.; Jiang, C.G.; Gao, X.Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Zh. H. Neural Correlates of Abnormal Cognitive Conflict Resolution in Major Depression: An Event-Related Potential Study. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H.; Soulodre, C.; Laing, A.; Kaulback, K.; Mitchell, A.; Thota, A.; Ng, V.; Sikich, N.; Dhalla, I.; Kates, N.; McCabe McMaster University, R.; Joseph, S.; Hamilton, H.; Kasperski, J.; Carter, S.; Laposa, J.; Mancuso, E. Psychotherapy for Major Depressive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Health Technology Assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2017, 17, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann, A.T.; Mallon, K.P.; Hunter, R.F.; Cardwell, C.R.; McMenamin, Ú.C.; Spence, A.D.; Coleman, H.G. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Risk of Oesophago-Gastric Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study within UK Biobank. United European Gastroenterol J 2018, 6, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.N.; Wong, C.; Heidenheim, P. Does Running Cause Gastrointestinal Symptoms? A Survey of 93 Randomly Selected Runners Compared with Controls. N Z Med J 1994, 107, 328–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, F.M.; Petriz, B.; Marques, G.; Kamilla, L.H.; Franco, O.L. Is There an Exercise-Intensity Threshold Capable of Avoiding the Leaky Gut? Front Nutr 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, T.H.; Ko, J.; Kim, S.S.; Yoon, J.S. Lacrimal Drainage Obstruction and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Nationwide Longitudinal Cohort Study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019, 53, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qumseya, B.J.; Tayem, Y.; Almansa, C.; Dasa, O.Y.; Hamadneh, M.K.; Al-Sharif, A.F.; Hmidat, A.M.; Abu-Limon, I.M.; Nahhal, K.W.; Alassas, K.; Devault, K.; Wallace, M.B.; Houghton, L.A. Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Middle-Aged and Elderly Palestinians: Its Prevalence and Effect of Location of Residence. Am J Gastroenterol 2014, 109, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, H.G.; Reider, B.D.; Whiting, A.B.; Prichard, J.R. Sleep Patterns and Predictors of Disturbed Sleep in a Large Population of College Students. J Adolesc Health 2010, 46, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, B.A.; Brian, M.S.; Morrell, J.S. The Relationship between Sleep Duration and Metabolic Syndrome Severity Scores in Emerging Adults. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F.M. Procrastination and Stress: A Conceptual Review of Why Context Matters. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Shi, S.; Dong, Y.; Cheng, H.; Li, T. The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress and Academic Procrastination between Physical Activity and Depressive Symptoms among Chinese College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piquer-Esteban, S.; Ruiz-Ruiz, S.; Arnau, V.; Diaz, W.; Moya, A. Exploring the Universal Healthy Human Gut Microbiota around the World. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2022, 20, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas-Egbariya, H.; Haberman, Y.; Braun, T.; Hadar, R.; Denson, L.; Gal-Mor, O.; Amir, A. Meta-Analysis Defines Predominant Shared Microbial Responses in Various Diseases and a Specific Inflammatory Bowel Disease Signal. Genome Biol 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicentini, F.A.; Keenan, C.M.; Wallace, L.E.; Woods, C.; Cavin, J.B.; Flockton, A.R.; Macklin, W.B.; Belkind-Gerson, J.; Hirota, S.A.; Sharkey, K.A. Intestinal Microbiota Shapes Gut Physiology and Regulates Enteric Neurons and Glia. Microbiome 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konturek, P.C.; Brzozowski, T.; Konturek, S.J. Stress and the Gut: Pathophysiology, Clinical Consequences, Diagnostic Approach and Treatment Options. J Physiol Pharmacol 2011, 62, 591–599. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari, P.; Shoaie, S.; Nielsen, L.K. Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Microbiome; Switching from Conventional Diagnosis and Therapies to Personalized Interventions. Journal of Translational Medicine 2022 20:1 2022, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, F.; Lui, G.C.Y.; Yeoh, Y.K.; Li, A.Y.L.; Zhan, H.; Wan, Y.; Chung, A.C.K.; Cheung, C.P.; Chen, N.; Lai, C.K.C.; Chen, Z.; Tso, E.Y.K.; Fung, K.S.C.; Chan, V.; Ling, L.; Joynt, G.; Hui, D.S.C.; Chan, F.K.L.; Chan, P.K.S.; Ng, S.C. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, T.; Wu, X.; Wen, W.; Lan, P. Gut Microbiome Alterations in COVID-19. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2021, 19, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).