Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

23 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

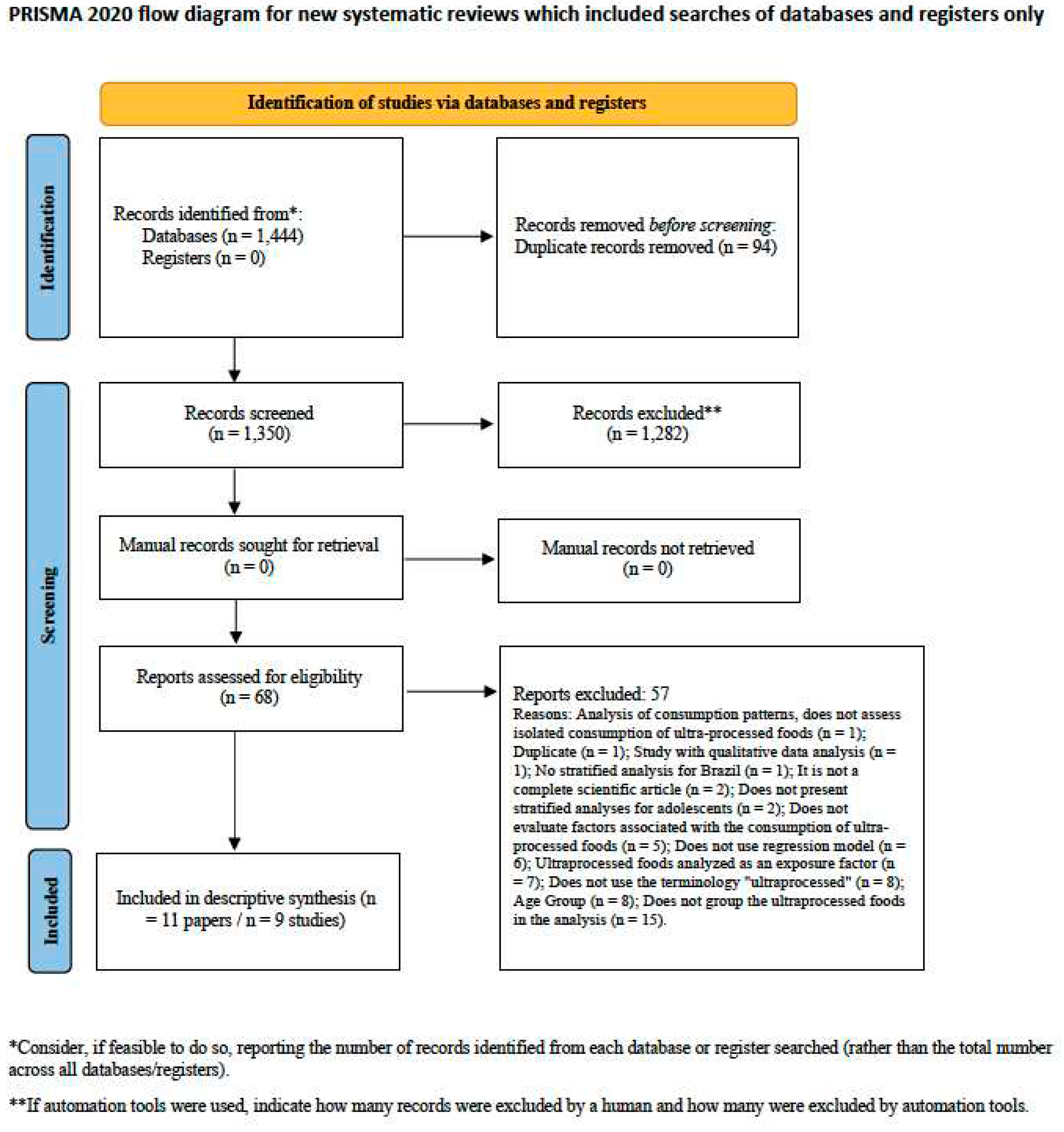

2. Materials and Methods

- Participants: Brazilian adolescents aged 11 to 19 years.

- Exposures: Individual, interpersonal, environmental and policy factors, with no restriction.

- Outcome: consumption of ultra-processed foods, measured by instruments that used the NOVA classification.

- Study design: scientific papers published in peer-review journals, which reported observational studies (e.g., case-controls, cohorts or cross-sectional studies).

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Registration

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Monteiro, C.A. Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 729–731. [CrossRef]

- Harb, A.A.; Shechter, A.; Koch, P.A.; St-Onge, M.P. Ultra-processed foods and the development of obesity in adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chen. X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Qiu, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, J.; Nie, J. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 86. [CrossRef]

- Louzada, M.L.D.C.; Costa, C.D.S.; Souza, T.N.; Cruz, G.L.D.; Levy, R.B.; Monteiro, C.A. Impact of the consumption of ultra-processed foods on children, adolescents and adults' health: scope review. Cad. Saude Publica 2022, 37(suppl 1), e00323020.

- Mazloomi, S.N.; Talebi, S.; Mehrabani, S.; Bagheri, R.; Ghavami, A.; Zarpoosh, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Wong, A.; Nordvall, M.; Kermani, M.A.H.; et al. The association of ultra-processed food consumption with adult mental health disorders: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of 260,385 participants. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, G.; Dinu, M.; Madarena, M.P.; Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Sofi, F. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 308–318. [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.S.; Del-Ponte, B.; Assunção, M.C.F.; Santos, I.S. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and body fat during childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 148-159. [CrossRef]

- Melo, B.; Rezende, L.; Machado, P.; Gouveia, N.; Levy, R. Associations of ultra-processed food and drink products with asthma and wheezing among Brazilian adolescents. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 29, 504–511. [CrossRef]

- Werneck, A.O.; Hoare, E.; Silva, D.R. Do TV viewing and frequency of ultra-processed food consumption share mediators in relation to adolescent anxiety-induced sleep disturbance? Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5491–5497. [CrossRef]

- Lane, K.E.; Davies, I.G.; Darabi, Z.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Khayyatzadeh, S.S.; Mazidi, M. The association between ultra-processed foods, quality of life and insomnia among adolescent girls in northeastern Iran. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 6338. [CrossRef]

- Louzada, M.L.; Baraldi, L.G.; Steele, E.M.; Martins, A.P.; Canella, D.S.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Cannon, G.; Afshin, A.; Imamura, F.; et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and obesity in Brazilian adolescents and adults. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, N.; Foster, C. Developing and applying a socio-ecological model to the promotion of healthy eating in the school. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1101–1108. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.H.; Ciliska, D.; Dobbins, M.; Micucci, S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2004, 1, 176–184. [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, E.N.; Retondario, A.; Alves, M.A.; Bricarello, L.P.; Rockenbach, G.; Hinnig, P.F.; Neves, J.D.; Vasconcelos, F.A.G. Utilization of food outlets and intake of minimally processed and ultra-processed foods among 7 to 14-year-old schoolchildren. A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2018, 136, 200–207. [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, P.C.F.P.; Arruda, I.K.G.; Coelho, P.B.P.; Queiroz, P.M.A.; Maio, R.; Silva Diniz, A. Consumption of ultraprocessed foods, nutritional status, and dyslipidemia in schoolchildren: a cohort study Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 1194-1199. [CrossRef]

- Monteles, L.; Santos, K.; Gomes, K.R.O.; Pacheco, R.; Malvina, T.; Gonçalves, K.M.; The impact of consumption of ultra-processed foods on the nutritional status of adolescents. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2019, 46, 429–435. [CrossRef]

- Santos Costa, C.; Formoso Assunção, M.C.; Santos Vaz, J.; Rauber, F.; Oliveira Bierhals, I.; Matijasevich, A.; Horta, B.L.; Gonçalves, H.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Santos, I.S. Consumption of ultra-processed foods at 11, 22 and 30 years at the 2004, 1993 and 1982 Pelotas Birth Cohorts. Public Health Nutr. 2021; 24, 299–308. [CrossRef]

- Viola, P.C.A.F.; Carvalho, C.A.; Bragança, M.L.B.M.; França, A.K.T.D.C.; Alves, M.T.S.S.B.E.; Silva, A.A.M. High consumption of ultra-processed foods is associated with lower muscle mass in Brazilian adolescents in the RPS birth cohort. Nutrition 2020, 79-80, 110983. [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.A.; Azeredo, C.M.; Peres, M.F.T.; Escuder, M.M.L.; Levy, R.B. Availability and consumption of ultra-processed foods in schools in the municipality of São Paulo, Brazil: results of the SP-Proso. Cad. Saude Publica 2022, 37(suppl 1), e00162920.

- Melo, A.S.; Neves, F.S.; Batista, A.P.; Machado-Coelho, G.L.L.; Sartorelli, D.S.; Faria, E.R.; Netto, M.P.; Oliveira, R.M., Fontes, V.S.; Cândido, A.P.C. Percentage of energy contribution according to the degree of industrial food processing and associated factors in adolescents (EVA-JF study, Brazil). Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4220-9. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.L.; Gratão, L.H.A.; Carmo, A.S.D.; Costa, A.B.P.; Cunha, C.F.; Oliveira, T.R.P.R.; Mendes, L.L. School type, eating habits, and screen time are associated with ultra-processed food consumption among Brazilian adolescents. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1136–1142. [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.D.S.; Flores, T.R.; Wendt, A.; Neves, R.G.; Assunção, M.C.F.; Santos, I.S. Sedentary behavior and consumption of ultra-processed foods by Brazilian adolescents: Brazilian National School Health Survey (PeNSE), 2015. Cad. Saude Publica 2018, 34, e00021017.

- Noll, P.R.E.S.; Noll, M.; Abreu, L.C.; Baracat, E.C.; Silveira, E.A.; Sorpreso, I.C.E. Ultra-processed food consumption by Brazilian adolescents in cafeterias and school meals. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7162. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.B.; Elias, B.C.; Warkentin, S.; Mais, L.A.; Konstantyner, T. Factors associated with the consumption of ultra-processed food by Brazilian adolescents: National Survey of School Health, 2015. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2021, 40, e2020362. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Saunders, T.J.; Carson, V.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Chastin, S.F.M.; Altenburg, T.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) - Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 75. [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Gray, C.E.; Poitras, V.J.; Chaput, J.P.; Saunders, T.J.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Okely, A.D.; Connor Gorber, S.; et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: an update. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41(6 Suppl 3), S240–265. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Shao, J.; Chen, D.; Cui, N.; Tang, L.; Fu, Y.; Xue. E.; Lai, C.; et al. Sedentary time and the risk of metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13510. [CrossRef]

- Rezende, L.F.; Rodrigues Lopes, M.; Rey-López, J.P.; Matsudo, V.K.; Luiz Odo, C. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes: an overview of systematic reviews. PLoS One 2014, 9, e105620. [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.O.; Guimarães, J.S.; Leite, F.H.M.; Mais, L.A.; Horta, P.M.; Bortoletto Martins, A.P.; Claro, R.M. Analysing persuasive marketing of ultra-processed foods on Brazilian television. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 1067–1077. [CrossRef]

- Maia, E.G.; Costa, B.V.L.; Coelho, F.S.; Guimarães, J.S.; Fortaleza, R.G.; Claro, R.M. Analysis of TV food advertising in the context of recommendations by the Food Guide for the Brazilian Population. Cad. Saude Publica 2017, 33, e00209115. [CrossRef]

- Fraga, R.S.; Silva, S.L.R.; Santos, L.C.D.; Titonele, L.R.O.; Carmo, A.D.S. The habit of buying foods announced on television increases ultra-processed products intake among schoolchildren. Cad. Saude Publica 2020, 36, e00091419. [CrossRef]

- Duran AC, Ricardo CZ, Mais LA, Martins APB, Taillie LS. Conflicting messages on food and beverage packages: front-of-package nutritional labeling, health and nutrition claims in Brazil. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2967. [CrossRef]

- Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Alimentos. Available online: https://www.abia.org.br/numeros-setor (accessed on May 16, 2023).

- Johnson, B.J.; Hendrie, G.A.; Golley, R.K. Reducing discretionary food and beverage intake in early childhood: a systematic review within an ecological framework. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 1684–1695. [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.G.; Ricardo, C.Z.; Machado, P.P.; Rauber, F.; Azeredo, C.M.; Levy, R.B. Eating meals with parents is associated with better quality of diet for Brazilian adolescents. Cad. Saude Publica 2019, 35, e00153918.

- Ribeiro, E.H.C.; Guerra, P.H.; Oliveira, A.C.; Silva, K.S.; Santos, P.: Santos, R.; Okely, A.; Florindo, A.A. Latin American interventions in children and adolescents' sedentary behavior: a systematic review. Rev. Saude Publica 2020, 54, 59. [CrossRef]

- Carmo, A.S.D.; Assis, M.M.; Cunha, C.F.; Oliveira, T.R.P.R.; Mendes, L.L. The food environment of Brazilian public and private schools. Cad. Saude Publica 2018, 34, e00014918. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira. 1ed; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brasil, 2014.

- Benvindo, J.L.S. Adesão ao Programa Nacional De Alimentação Escolar: fatores associados e a qualidade nutricional das refeições. Master degree. Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil, July 30, 2018.

- Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação. Nota Técnica nº 2974175/2022/COSAN/CGPAE/DIRAE.

- Mello, G.T.; Lopes, M.V.V.; Minatto, G.; Costa, R.M.D.; Matias, T.S.; Guerra, P.H.; Barbosa Filho V.C.; Silva, K.S. Clustering of physical activity, diet and sedentary behavior among youth from low-, middle-, and high-income countries: a scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10924. [CrossRef]

- Leech, R.M.; McNaughton, S.A.; Timperio, A. The clustering of diet, physical activity and sedentary behavior in children and adolescents: a review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 4. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Place (Data collection) | Sample size (%F) | Age range (mean) | Sampling | Instrument used to assess food intake | Point prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correa et al., 2018 [15] | Florianópolis-SC (2012–13) | 888 (52)a | 11–14 (nd) | P | QUADA-3 | Previous Day |

| Gadelha et al., 2019 [16] | Recife-PE (2008–13) | 238 (61) | 10–16 (11; 15) | nd | FFQ | Previous Month |

| Monteles et al., 2019 [17] | Teresina-PI (nd) | 617 (57) | 14–19 (17) | P | Food recall | Previous Day |

| Costa et al., 2020 [18] | Pelotas-RS (2015) | 3.514 (48) | 11 (11) | Birth Cohortb | IDS and FFQ | Previous Year |

| Viola et al., 2020 [19] | São Luís-MA (2016) | 1.525 (53) | 18–19 (nd) | Birth Cohortc | FFQ | Previous Year |

| Leite et al., 2021 [20] | São Paulo-SP (2017) | 2.680 (47) | 14–15 (15) | P | Food recalld | Previous Week |

| Melo et al., 2021 [21] | Juiz de Fora-MG (2018–19) | 804 (58) | 14–19 (16) | P | Food recall | Previous Week |

| Rocha et al., 2021 [22] | Country (2013–14) | 71.553 (56) | 12–17 (15) | P | Food recall | Previous Day |

| Costa et al., 2018 [23] | Country (2015)e | 16.324f (nd); 102.072 (53) | 14–15 (nd) | P | Food recall | Previous Week |

| Noll et al., 2019 [24] | ||||||

| Silva et al., 2021 [25] | ||||||

| Legends: a: Considers the percentage of girls in the total sample (7–14 years old); b: All children born in Pelotas (2004); c: All children born in 10 maternity hospitals in São Luís (March 1997 - February 1998); d: adapted from the National School Health Survey, 2015; e: Articles generated from data of the National School Health Survey 2015; f: Sample 2 of the National School Health Survey, 2015: %F: percentage of females; FFQ: food frequency questionnaire; IDS: instrument developed for the study; MA: Maranhão; nd: not described; MG: Minas Gerais; P: sample composed by probabilistic method; PE: Pernambuco; PI: Piaui; QUADA-3: Previous Day Food Questionnaire; RS: Rio Grande do Sul; SC: Santa Catarina; SP: São Paulo. | ||||||

| Reference | Sample profile | Study Design | Representativeness (level) | instruments used to assess food intake | Losses and / or withdrawals | Statistical analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correa et al., 2018 [15] | Low | CS | Low (city) | Low | Low | Low |

| Gadelha et al., 2019 [16] | Moderate | CS-CO | nd | Low | nd | Low |

| Monteles et al., 2019 [17] | Low | CS | nd | Low | nd | Low |

| Costa et al., 2020 [18] | Low | CS-CO | Low (city) | Low | Low | Low |

| Viola et al., 2020 [19] | Low | CS-CO | Low (city) | Low | Low | Low |

| Leite et al., 2021 [20] | Low | CS | Low (city) | Low | Low | Low |

| Melo et al., 2021 [21] | Moderate | CS | Low (city) | Low | Low | Low |

| Rocha et al., 2021 [22] | Low | CS | Low (country) | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Costa et al., 2018 [23] | Low | CS | Low (country) | Low | Low | Low |

| Noll et al., 2019 [24] | ||||||

| Silva et al., 2021 [25] | ||||||

| Legends: CS: cross sectional study; CS-CO: cross-sectional analysis based on cohort study; nd: not described | ||||||

| Sedentary Behavior – Individual domain (n = 5) |

|---|

| Costa et al., 201823 (sitting and screen time): Linear trend, with dose-response effect Melo et al., 202121 (screen time): β = 0.38 (95%CI = 0.13–0.62) Rocha et al., 202122 (Eating in front of screens): β = 4.2 (95%CI = -3.1–5.3) Rocha et al., 202122:(>2 h/d on screens): β = 4.2 (95%CI = 1.2–4.3) Silva et al., 202125 (Sitting time): PR = 1.13 (95%CI = 1.11–1.16) Silva et al., 202125 (Eating while watching television): PR = 1.09 (95%CI = 1.07–1.10) Gadelha et al. 201916 (screen time): 2008-9: OR = 0.75 (95%CI = 0.22–2.75) Gadelha et al. 201916 (screen time): 2012-13: OR = 1.40 (95%CI = 0.66–2.95) |

| Administrative dependence of the school – Environmental domain (n = 4) |

| Noll et al., 201924 (private school): PR = 1.29 (95%CI = 1.23–1.35) Rocha et al., 202122 (private school): β = 1.9 (95%CI = 0.8–2.9) Silva et al., 202125 (private school): β = 1.11 (95%CI = 1.02–1.09) Monteles et al., 201917 (private school): β+* = -0.06 (95%CI = -3.50–0.40) |

| Body Mass Index – Individual domain (n = 4) |

| Melo et al., 202121: β = 0.03 (95%CI = 0.05–0.00) Monteles et al., 201917 (≥25.0 kg/m2): β+* = 0.11 (95%CI = 10.9–3.94) Viola et al., 202019: β = 0.01 (95%CI = 0.03–0.01) Gadelha et al., 201916 (2008–9): OR = 0.70 (95%CI = 0.16–3.10) Gadelha et al., 201916 (2012–13): OR = 1.04 (95%CI = 0.25–4.34) |

| Maternal schooling – Interpersonal domain (n = 4) |

| Costa et al., 202023: Inverse dose-response relationship (p = 0.003) Silva et al., 202125 (lack of maternal education): PR = 0.88 (95%CI = 0.83–0.94) Gadelha et al., 201916: (2008–9): OR = 0.68 (95%CI = 0.04–13.19) Melo et al., 202121: β = 0.16 (95%CI = -0.07–0.39) |

| Age – Individual domain (n = 4) |

| Noll et al., 201924 (16–19 years old): PR = 0.89 (95%CI = 0.85–0.93) Silva et al., 202125 (<15 years old): PR = 1.08 (95%CI = 1.06–1.11) Gadelha et al., 201916 (2008–9): β = 0.34 (SE = 0.02) Gadelha et al., 201916 (2012–13): β = 0.15 (SE = 0.06) Melo et al., 202121: β = -0.31 (95%CI = -0.34–0.96) |

| Waist circumference – Individual domain (n = 4) |

| Gadelha et al. 201916: 2012–13: OR = 1.44 (95%CI = 0.02–0.94) Gadelha et al., 201916: 2008-9: RR = 0,37 (95%CI = 0,06; 2,31) Viola et al., 202017: β = -0,02 (95%CI = -0,05; 0,01) Melo et al., 202121: β = -0,04 (95%CI = -0,10; 0,02) |

| Gender – Individual domain (n = 3) |

| Monteles et al., 201917 (females): β+ = 0.39 (95%CI = 7.3–12.4) Noll et al., 201924 (females): PR = 1.12 (95%CI = 1.10–1.15) Costa et al., 202023: No differences (p = 0.47) |

| Socioeconomic level – Individual domain (n = 3) |

| Melo et al., 202121: β = 0.12 (95%CI = 0.03–0.21) Monteles et al., 201917 (≥ 2 minimum wages): β+ = -0.01 (95%CI = -2.60–2.10) Costa et al., 202023: No differences (p = 0,93) |

| Legends: *: compared to adolescents who had Body Mass Index up to 24.9 kg/m2; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; PR: prevalence ratio; SE: standard error. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).