Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

23 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R)

2.1. Structure

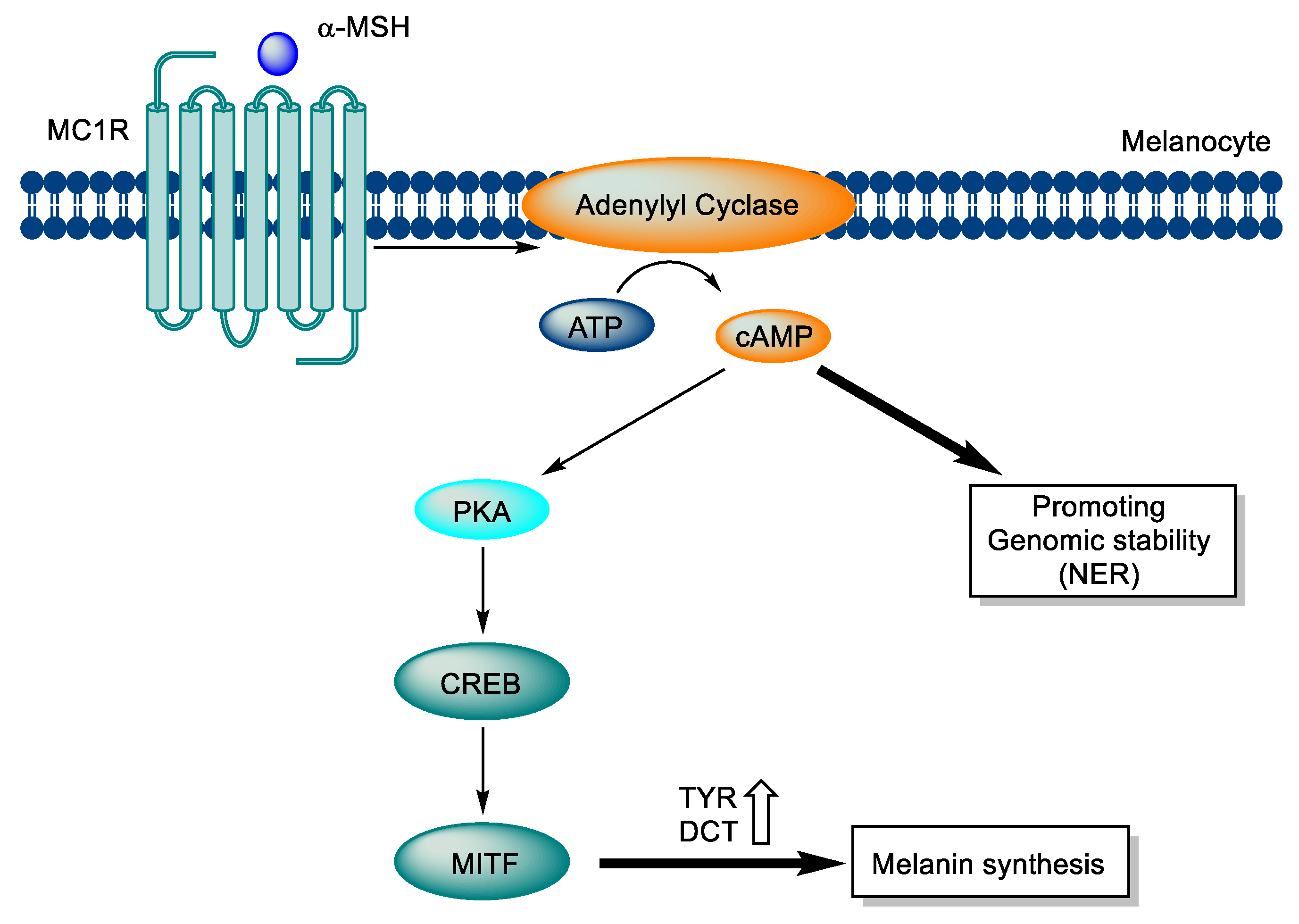

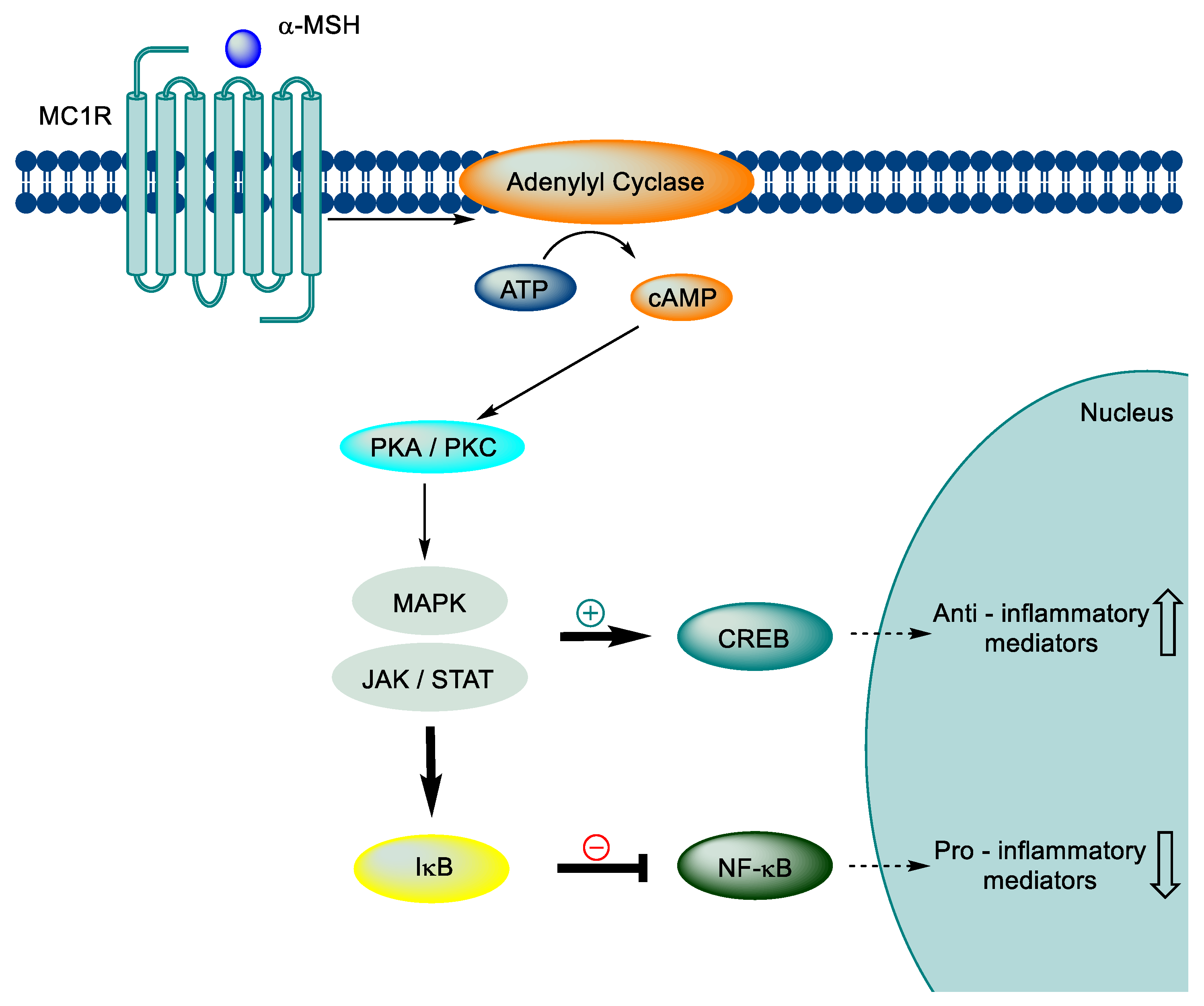

2.2. Signaling pathway

3. MC1R related diseases

3.1. Melanoma

3.2. Systemic sclerosis

3.3. Neuroinflammation

3.4. Atherosclerosis

4. Modulators

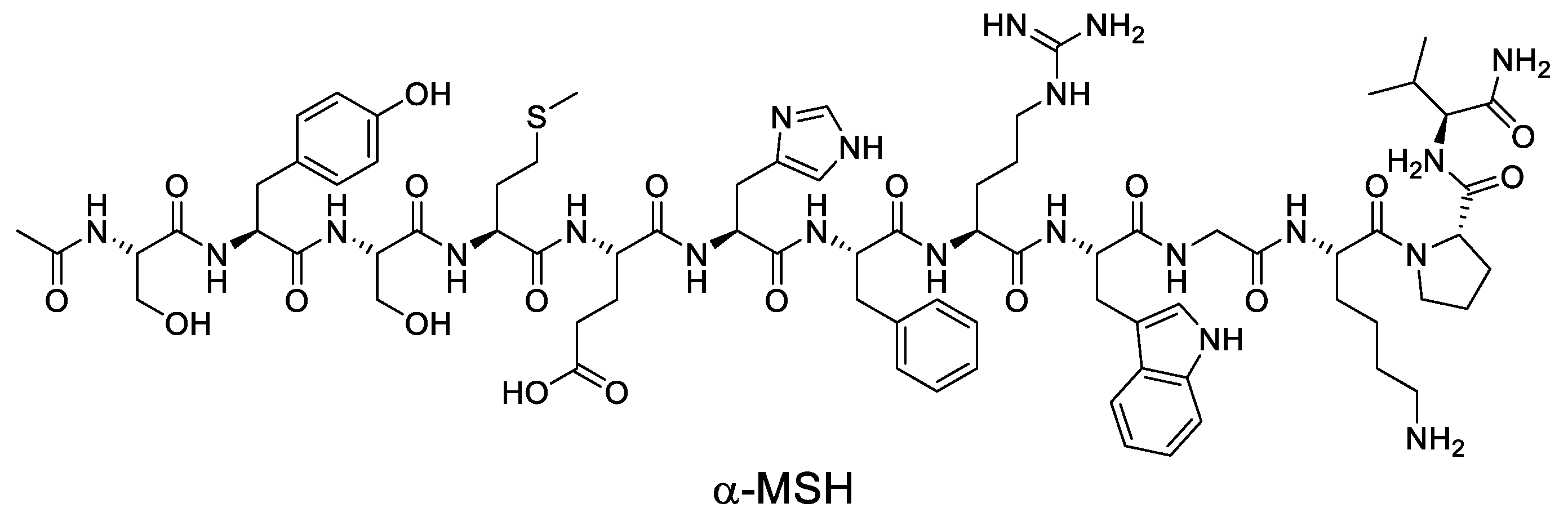

4.1. Endogenous ligands

4.2. Synthetic Peptide modulators

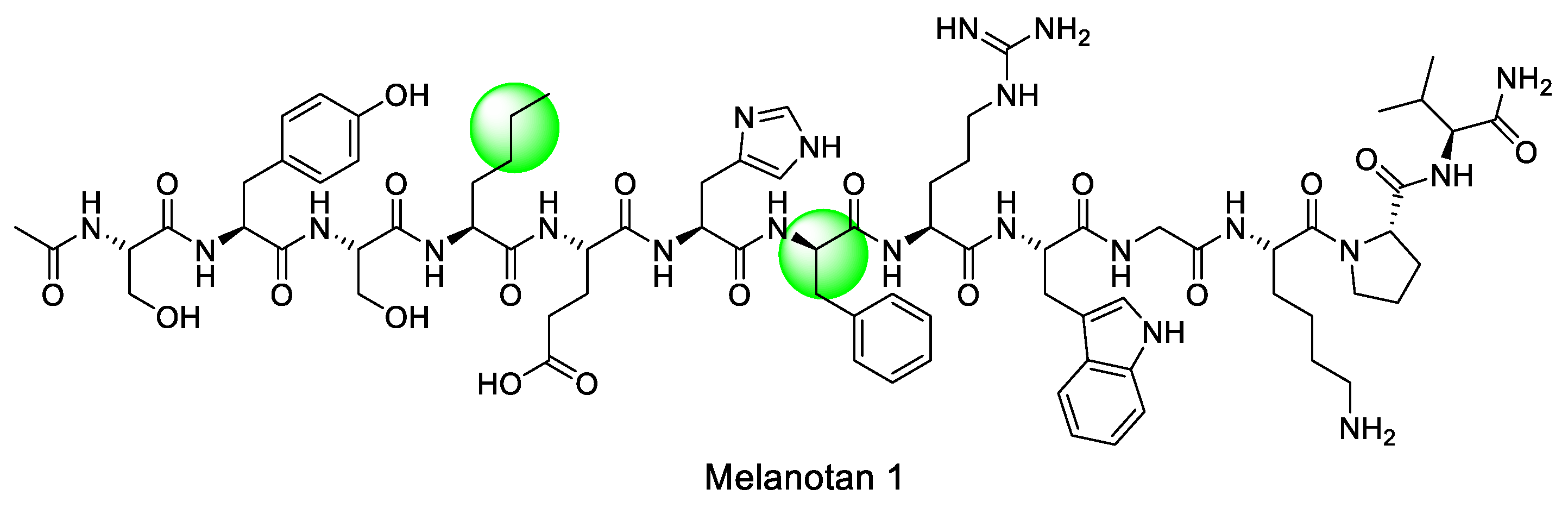

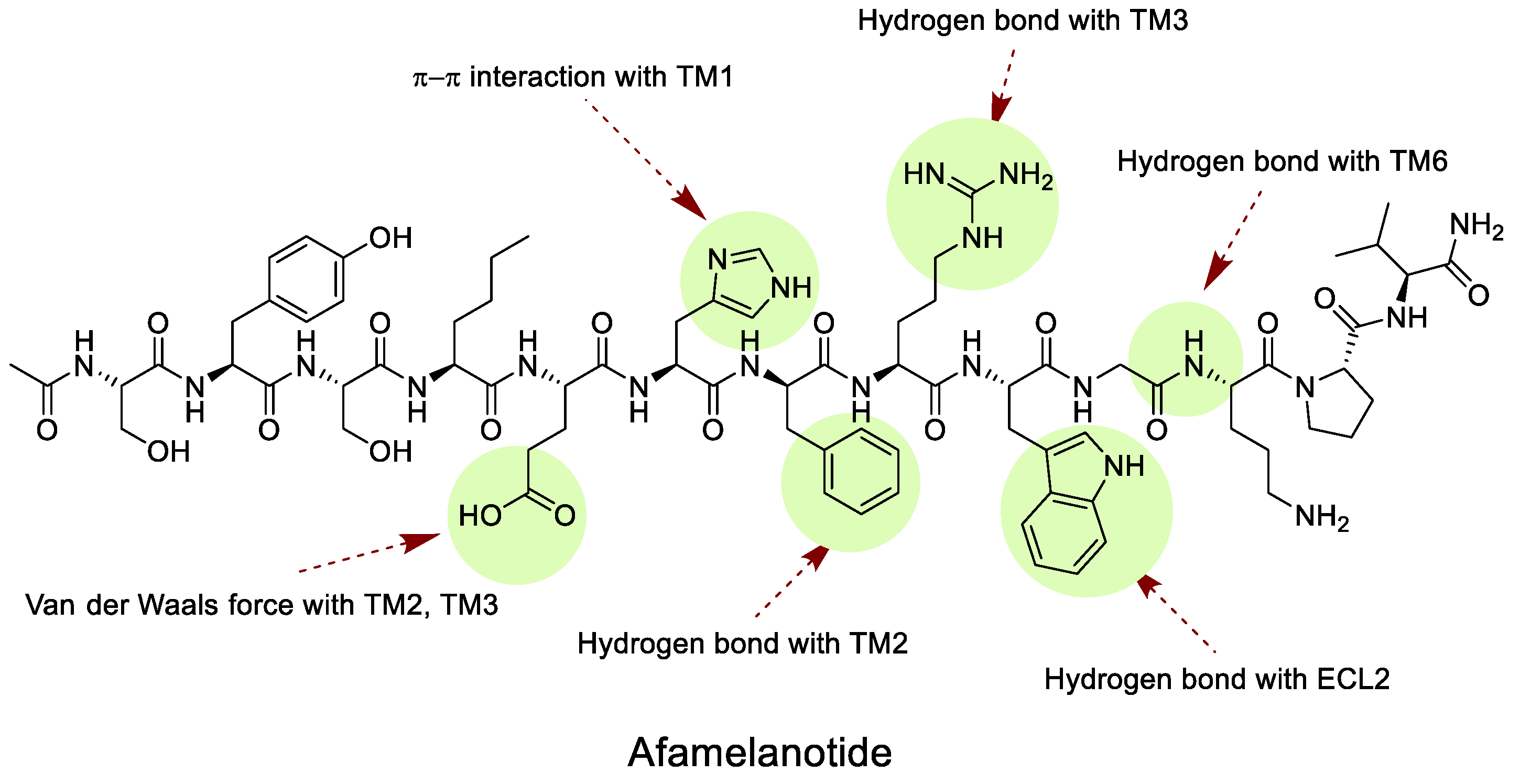

4.2.1. Melanotan I (MT-I)

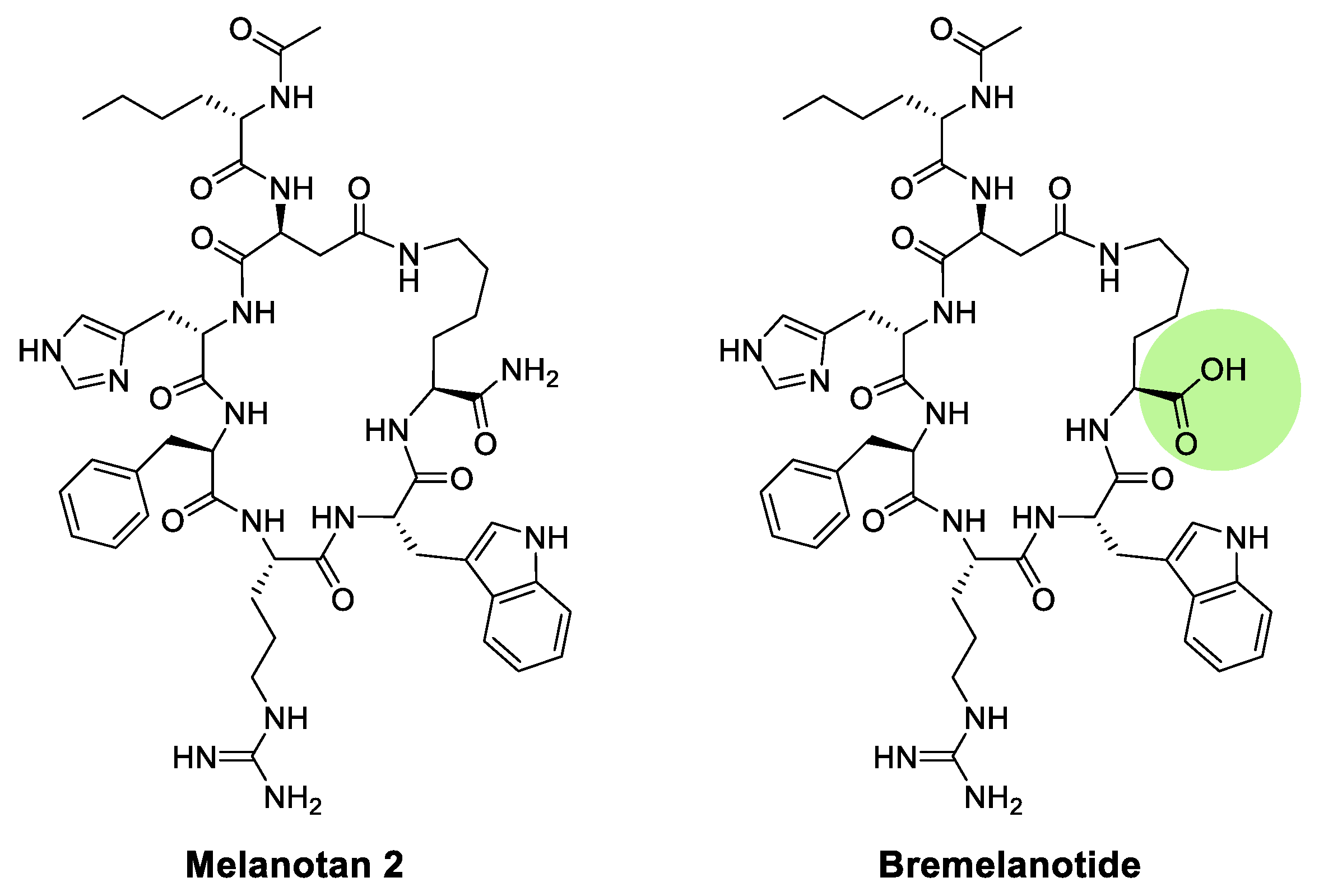

4.2.2. Melanotan II (MT-II)

4.3. Small molecule modulators

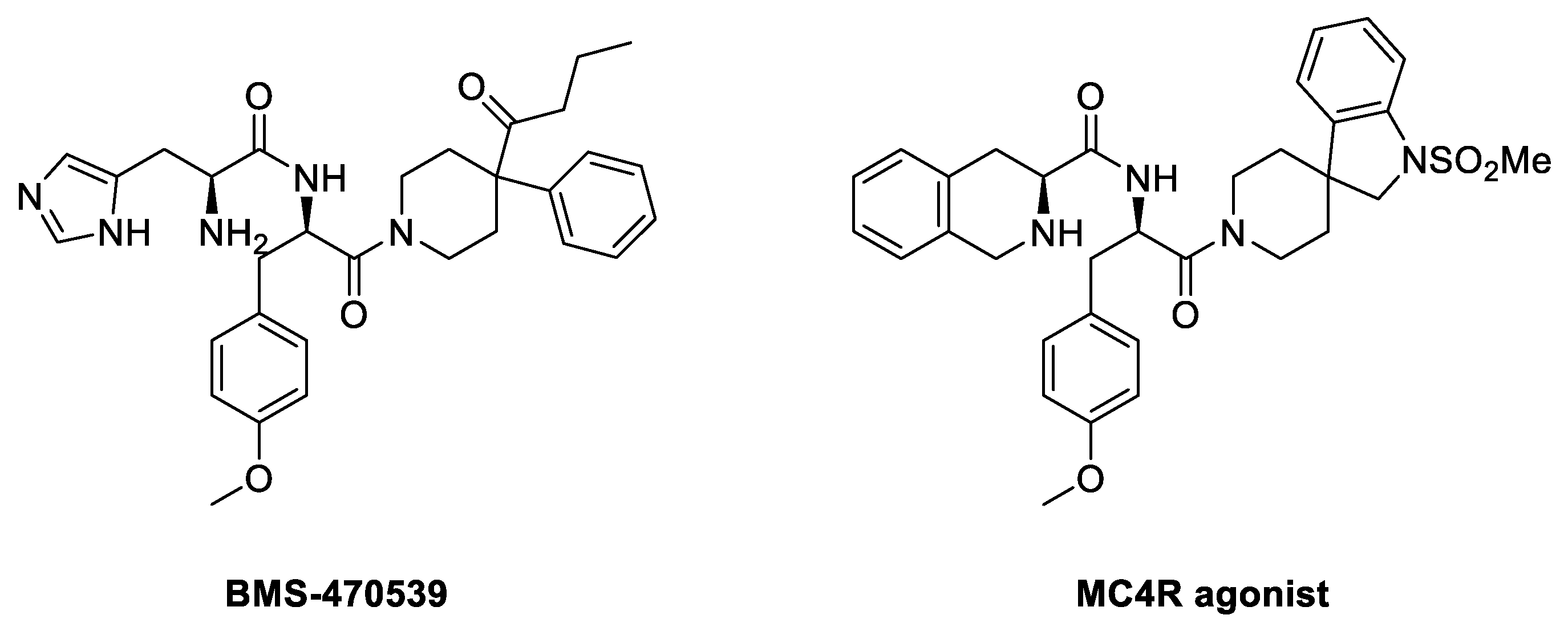

4.3.1. BMS-470539

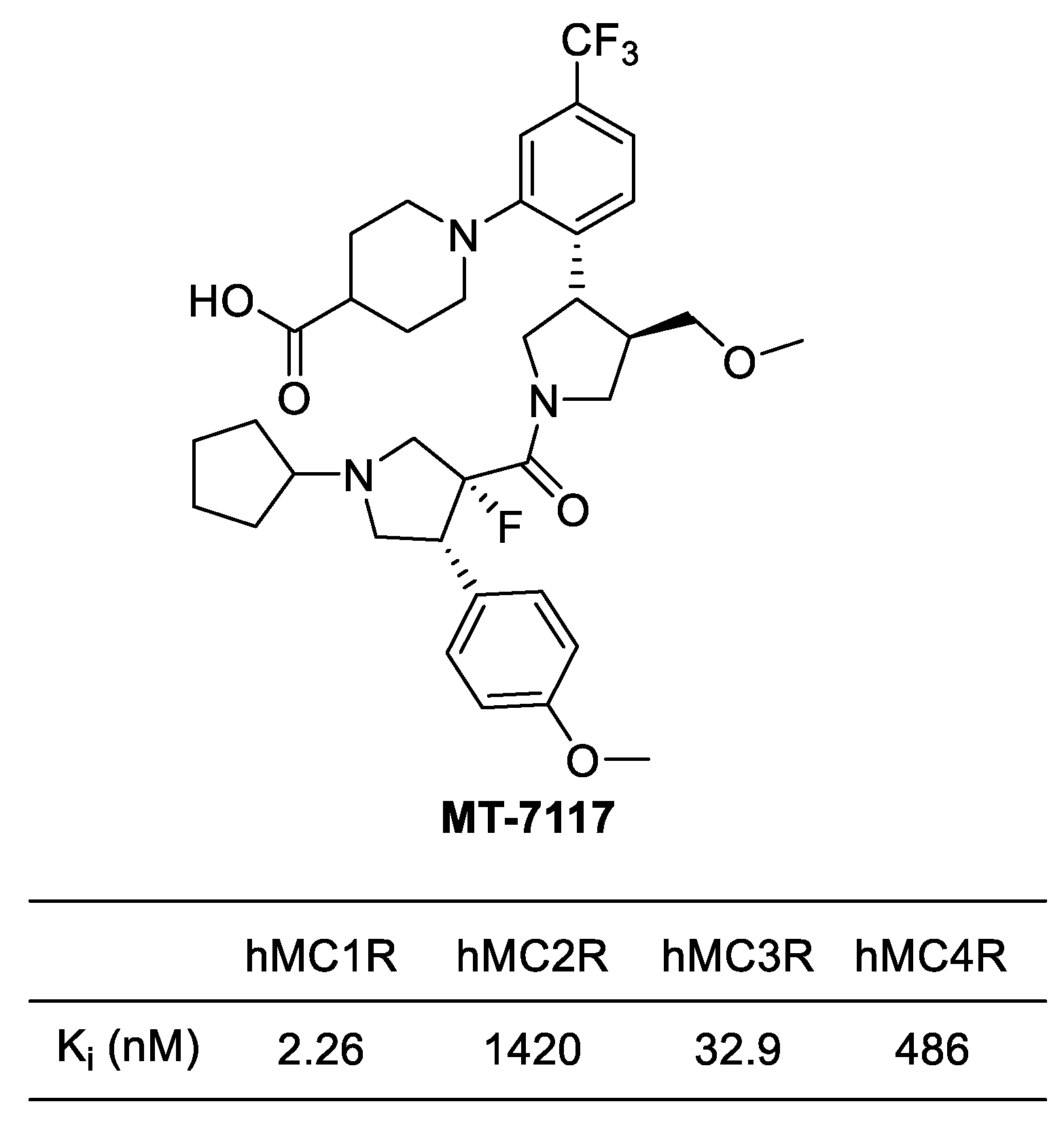

4.3.2. MT-7117 (Dersimelagon)

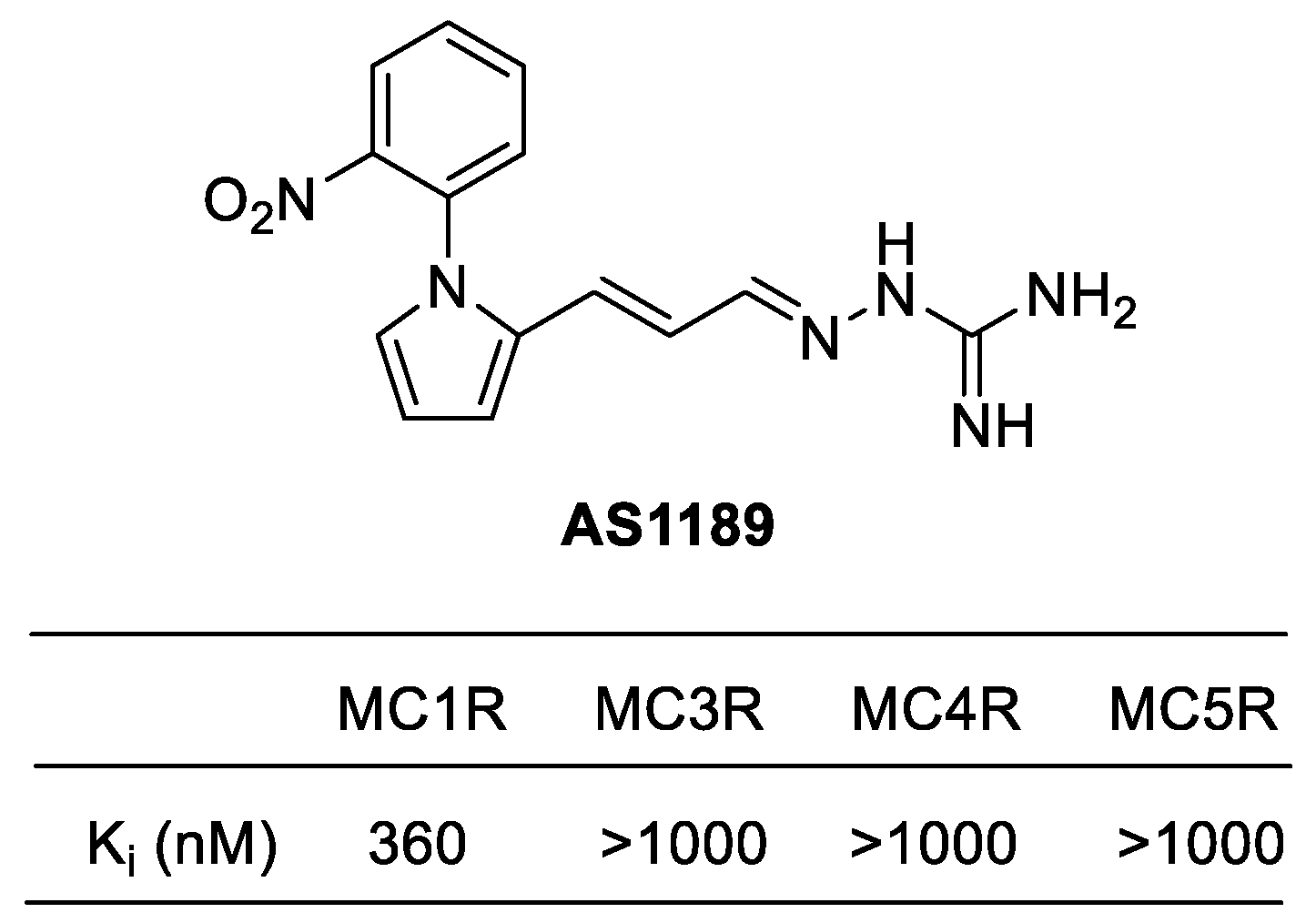

4.3.3. AP1189 (Resomelagon)

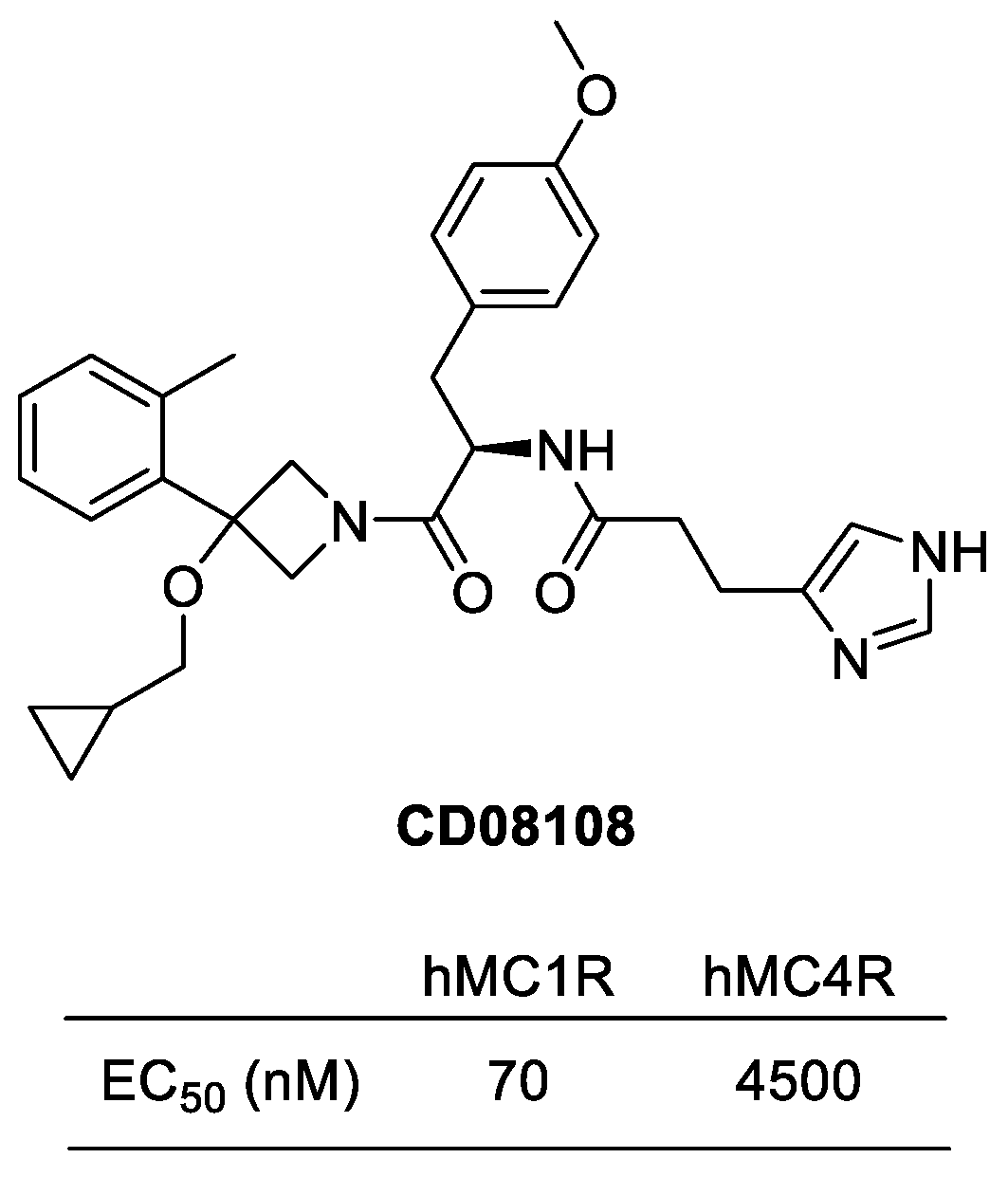

4.3.4. CD08108

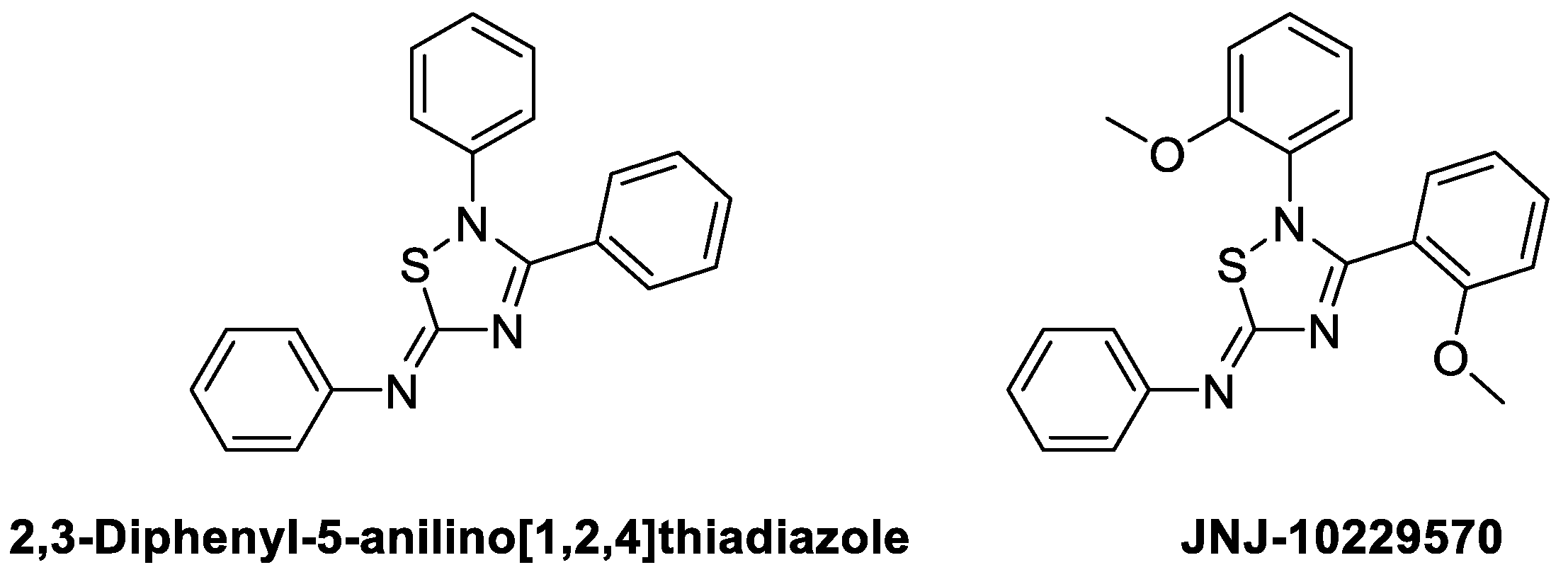

4.3.5. JNJ-10229570

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cawley, N.X.; Li, Z.; Loh, Y.P. 60 YEARS OF POMC: Biosynthesis, trafficking, and secretion of pro-opiomelanocortin-derived peptides. J Mol Endocrinol 2016, 56, T77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dores, R.M.; Liang, L.; Davis, P.; Thomas, A.L.; Petko, B. 60 YEARS OF POMC: Melanocortin receptors: evolution of ligand selectivity for melanocortin peptides. J Mol Endocrinol 2016, 56, T119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo-Payet, N. 60 YEARS OF POMC: Adrenal and extra-adrenal functions of ACTH. J Mol Endocrinol 2016, 56, T135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, J.M.; Ceriani, G.; Macaluso, A.; McCoy, D.; Carnes, K.; Biltz, J.; Catania, A. Antiinflammatory effects of the neuropeptide alpha-MSH in acute, chronic, and systemic inflammation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1994, 741, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, A.; Cutuli, M.; Garofalo, L.; Carlin, A.; Airaghi, L.; Barcellini, W.; Lipton, J.M. The neuropeptide alpha-MSH in host defense. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000, 917, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutuli, M.; Cristiani, S.; Lipton, J.M.; Catania, A. Antimicrobial effects of alpha-MSH peptides. J Leukoc Biol 2000, 67, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, M.F.; Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; Montero-Melendez, T.; Werneck, S.M.; Correa, J.D.; Soriani, F.M.; Garlet, G.P.; Souza, D.G.; Teixeira, M.M.; Silva, T.A.; et al. Melanocortin agonism as a viable strategy to control alveolar bone loss induced by oral infection. FASEB J 2016, 30, 4033–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-SanMiguel, A.B.; Martin, A.I.; Nieto-Bona, M.P.; Fernandez-Galaz, C.; Villanua, M.A.; Lopez-Calderon, A. The melanocortin receptor type 3 agonist d-Trp(8)-gammaMSH decreases inflammation and muscle wasting in arthritic rats. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2016, 7, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-SanMiguel, A.B.; Villanua, M.A.; Martin, A.I.; Lopez-Calderon, A. D-TRP(8)-gammaMSH Prevents the Effects of Endotoxin in Rat Skeletal Muscle Cells through TNFalpha/NF-KB Signalling Pathway. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0155645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiri, J.J.; Thapa, K.; Kaipio, K.; Cai, M.; Hruby, V.J.; Rinne, P. Melanocortin 3 receptor activation with [D-Trp8]-gamma-MSH suppresses inflammation in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2020, 880, 173186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y. Structure, function and regulation of the melanocortin receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 2011, 660, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf Horrell, E.M.; Boulanger, M.C.; D'Orazio, J.A. Melanocortin 1 Receptor: Structure, Function, and Regulation. Front Genet 2016, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantz, I.; Shimoto, Y.; Konda, Y.; Miwa, H.; Dickinson, C.J.; Yamada, T. Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of a fifth melanocortin receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994, 200, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantz, I.; Miwa, H.; Konda, Y.; Shimoto, Y.; Tashiro, T.; Watson, S.J.; DelValle, J.; Yamada, T. Molecular cloning, expression, and gene localization of a fourth melanocortin receptor. J Biol Chem 1993, 268, 15174–15179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desarnaud, F.; Labbe, O.; Eggerickx, D.; Vassart, G.; Parmentier, M. Molecular cloning, functional expression and pharmacological characterization of a mouse melanocortin receptor gene. Biochem J 1994, 299 ( Pt 2) Pt 2, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, K.G.; Robbins, L.S.; Mortrud, M.T.; Cone, R.D. The cloning of a family of genes that encode the melanocortin receptors. Science 1992, 257, 1248–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaible, E.V.; Steinstrasser, A.; Jahn-Eimermacher, A.; Luh, C.; Sebastiani, A.; Kornes, F.; Pieter, D.; Schafer, M.K.; Engelhard, K.; Thal, S.C. Single administration of tripeptide alpha-MSH(11-13) attenuates brain damage by reduced inflammation and apoptosis after experimental traumatic brain injury in mice. PLoS One 2013, 8, e71056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Becher, E.; Mahnke, K.; Hartmeyer, M.; Schwarz, T.; Scholzen, T.; Luger, T.A. Evidence for the differential expression of the functional alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor MC-1 on human monocytes. J Immunol 1997, 158, 3378–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, W.; Stutz, S.; Eberle, A.N. Homologous and heterologous regulation of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptors in human and mouse melanoma cell lines. Cancer Res 1994, 54, 2604–2610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, W.; Solca, F.; Stutz, S.; Giuffre, L.; Carrel, S.; Girard, J.; Eberle, A.N. Characterization of receptors for alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone on human melanoma cells. Cancer Res 1989, 49, 6352–6358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghanem, G.E.; Comunale, G.; Libert, A.; Vercammen-Grandjean, A.; Lejeune, F.J. Evidence for alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (alpha-MSH) receptors on human malignant melanoma cells. Int J Cancer 1988, 41, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.W.; Newton, R.A.; Beaumont, K.A.; Helen Leonard, J.; Sturm, R.A. Quantitative analysis of MC1R gene expression in human skin cell cultures. Pigment Cell Res 2006, 19, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donatien, P.D.; Hunt, G.; Pieron, C.; Lunec, J.; Taieb, A.; Thody, A.J. The expression of functional MSH receptors on cultured human melanocytes. Arch Dermatol Res 1992, 284, 424–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Laorden, B.L.; Sanchez-Mas, J.; Turpin, M.C.; Garcia-Borron, J.C.; Jimenez-Cervantes, C. Variant amino acids in different domains of the human melanocortin 1 receptor impair cell surface expression. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2006, 52, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frandberg, P.A.; Doufexis, M.; Kapas, S.; Chhajlani, V. Cysteine residues are involved in structure and function of melanocortin 1 receptor: Substitution of a cysteine residue in transmembrane segment two converts an agonist to antagonist. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001, 281, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, E.; von Heijne, G. Properties of N-terminal tails in G-protein coupled receptors: a statistical study. Protein Eng 1995, 8, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhajlani, V.; Xu, X.; Blauw, J.; Sudarshi, S. Identification of ligand binding residues in extracellular loops of the melanocortin 1 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996, 219, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Borron, J.C.; Sanchez-Laorden, B.L.; Jimenez-Cervantes, C. Melanocortin-1 receptor structure and functional regulation. Pigment Cell Res 2005, 18, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, J.A.; Freedman, N.J.; Lefkowitz, R.J. G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Annu Rev Biochem 1998, 67, 653–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, L.M.; Lefkowitz, R.J. The role of beta-arrestins in the termination and transduction of G-protein-coupled receptor signals. J Cell Sci 2002, 115, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strader, C.D.; Fong, T.M.; Tota, M.R.; Underwood, D.; Dixon, R.A. Structure and function of G protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Biochem 1994, 63, 101–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qanbar, R.; Bouvier, M. Role of palmitoylation/depalmitoylation reactions in G-protein-coupled receptor function. Pharmacol Ther 2003, 97, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulein, R.; Hermosilla, R.; Oksche, A.; Dehe, M.; Wiesner, B.; Krause, G.; Rosenthal, W. A dileucine sequence and an upstream glutamate residue in the intracellular carboxyl terminus of the vasopressin V2 receptor are essential for cell surface transport in COS.M6 cells. Mol Pharmacol 1998, 54, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, B.; Schwartz, T.W. Molecular mechanism of agonism and inverse agonism in the melanocortin receptors: Zn(2+) as a structural and functional probe. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003, 994, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Chen, Y.; Dai, A.; Yin, W.; Guo, J.; Yang, D.; Zhou, F.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, M.W.; Xu, H.E. Structural mechanism of calcium-mediated hormone recognition and Gbeta interaction by the human melanocortin-1 receptor. Cell Res 2021, 31, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrett, S.G.; Horrell, E.M.W.; Christian, P.A.; Vanover, J.C.; Boulanger, M.C.; Zou, Y.; D'Orazio, J.A. PKA-mediated phosphorylation of ATR promotes recruitment of XPA to UV-induced DNA damage. Mol Cell 2014, 54, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadekaro, A.L.; Leachman, S.; Kavanagh, R.J.; Swope, V.; Cassidy, P.; Supp, D.; Sartor, M.; Schwemberger, S.; Babcock, G.; Wakamatsu, K.; et al. Melanocortin 1 receptor genotype: an important determinant of the damage response of melanocytes to ultraviolet radiation. FASEB J 2010, 24, 3850–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Mosby, N.; Yang, J.; Xu, A.; Abdel-Malek, Z.; Kadekaro, A.L. alpha-MSH activates immediate defense responses to UV-induced oxidative stress in human melanocytes. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2009, 22, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokot, A.; Metze, D.; Mouchet, N.; Galibert, M.D.; Schiller, M.; Luger, T.A.; Bohm, M. Alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone counteracts the suppressive effect of UVB on Nrf2 and Nrf-dependent gene expression in human skin. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3197–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Malek, Z.A.; Swope, V.B.; Starner, R.J.; Koikov, L.; Cassidy, P.; Leachman, S. Melanocortins and the melanocortin 1 receptor, moving translationally towards melanoma prevention. Arch Biochem Biophys 2014, 563, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, I.; Tada, A.; Ollmann, M.M.; Barsh, G.S.; Im, S.; Lamoreux, M.L.; Hearing, V.J.; Nordlund, J.J.; Abdel-Malek, Z.A. Agouti signaling protein inhibits melanogenesis and the response of human melanocytes to alpha-melanotropin. J Invest Dermatol 1997, 108, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsam, R.T.; Gutkind, J.S. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2007, 7, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, S.R.; Ram, P.T.; Iyengar, R. G protein pathways. Science 2002, 296, 1636–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herraiz, C.; Garcia-Borron, J.C.; Jimenez-Cervantes, C.; Olivares, C. MC1R signaling. Intracellular partners and pathophysiological implications. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017, 1863, 2448–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohm, M.; Schulte, U.; Kalden, H.; Luger, T.A. Alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone modulates activation of NF-kappa B and AP-1 and secretion of interleukin-8 in human dermal fibroblasts. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999, 885, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Narazaki, M.; Kishimoto, T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 6, a016295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfiglio, V.; Camillieri, G.; Avitabile, T.; Leggio, G.M.; Drago, F. Effects of the COOH-terminal tripeptide alpha-MSH(11-13) on corneal epithelial wound healing: role of nitric oxide. Exp Eye Res 2006, 83, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, E.; Mahnke, K.; Brzoska, T.; Kalden, D.H.; Grabbe, S.; Luger, T.A. Human peripheral blood-derived dendritic cells express functional melanocortin receptor MC-1R. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999, 885, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholzen, T.E.; Sunderkotter, C.; Kalden, D.H.; Brzoska, T.; Fastrich, M.; Fisbeck, T.; Armstrong, C.A.; Ansel, J.C.; Luger, T.A. Alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced vasculitis by down-regulating endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalden, D.H.; Scholzen, T.; Brzoska, T.; Luger, T.A. Mechanisms of the antiinflammatory effects of alpha-MSH. Role of transcription factor NF-kappa B and adhesion molecule expression. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999, 885, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dong, L.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. alpha-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone protects retinal vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress and apoptosis in a rat model of diabetes. PLoS One 2014, 9, e93433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimberti, D.; Baron, P.; Meda, L.; Prat, E.; Scarpini, E.; Delgado, R.; Catania, A.; Lipton, J.M.; Scarlato, G. Alpha-MSH peptides inhibit production of nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha by microglial cells activated with beta-amyloid and interferon gamma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999, 263, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, R.; Carlin, A.; Airaghi, L.; Demitri, M.T.; Meda, L.; Galimberti, D.; Baron, P.; Lipton, J.M.; Catania, A. Melanocortin peptides inhibit production of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide by activated microglia. J Leukoc Biol 1998, 63, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherzadeh, S.; Sharma, S.; Chhajlani, V.; Gantz, I.; Rajora, N.; Demitri, M.T.; Kelly, L.; Zhao, H.; Ichiyama, T.; Catania, A.; et al. alpha-MSH and its receptors in regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by human monocyte/macrophages. Am J Physiol 1999, 276, R1289–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottani, A.; Giuliani, D.; Neri, L.; Calevro, A.; Canalini, F.; Vandini, E.; Cainazzo, M.M.; Ruberto, I.A.; Barbieri, A.; Rossi, R.; et al. NDP-alpha-MSH attenuates heart and liver responses to myocardial reperfusion via the vagus nerve and JAK/ERK/STAT signaling. Eur J Pharmacol 2015, 769, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buggy, J.J. Binding of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone to its G-protein-coupled receptor on B-lymphocytes activates the Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem J 1998, 331 Pt 1, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrika, I.; Muceniece, R.; Wikberg, J.E. Effects of melanocortin peptides on lipopolysaccharide/interferon-gamma-induced NF-kappaB DNA binding and nitric oxide production in macrophage-like RAW 264.7 cells: evidence for dual mechanisms of action. Biochem Pharmacol 2001, 61, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlo, S.; Kooijman, R.; Beck, I.M.; Kolmus, K.; Spooren, A.; Haegeman, G. Cyclic AMP: a selective modulator of NF-kappaB action. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011, 68, 3823–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.K.; Aggarwal, B.B. Alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone inhibits the nuclear transcription factor NF-kappa B activation induced by various inflammatory agents. J Immunol 1998, 161, 2873–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, D.Y.; Lin, Y.J.; Tao, Y.X. Melanocortin Regulation of Inflammation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J.A.; Fisher, D.E. The melanoma revolution: from UV carcinogenesis to a new era in therapeutics. Science 2014, 346, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenkranz, A.A.; Slastnikova, T.A.; Durymanov, M.O.; Sobolev, A.S. Malignant melanoma and melanocortin 1 receptor. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2013, 78, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar-Onfray, F.; Lopez, M.; Lundqvist, A.; Aguirre, A.; Escobar, A.; Serrano, A.; Korenblit, C.; Petersson, M.; Chhajlani, V.; Larsson, O.; et al. Tissue distribution and differential expression of melanocortin 1 receptor, a malignant melanoma marker. Br J Cancer 2002, 87, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbah, Z.; Puig-Butille, J.A.; Simonetta, F.; Badenas, C.; Cervera, R.; Mila, J.; Benitez, D.; Malvehy, J.; Vilella, R.; Puig, S. Molecular characterization of human cutaneous melanoma-derived cell lines. Anticancer Res 2012, 32, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eggermont, A.M. Advances in systemic treatment of melanoma. Ann Oncol 2010, 21 Suppl 7, vii339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriyama, N.; Yoshino, Y.; Yuan, B.; Horikoshi, A.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Hatta, Y.; Toyoda, H.; Takeuchi, J. Speciation of arsenic trioxide metabolites in peripheral blood and bone marrow from an acute promyelocytic leukemia patient. J Hematol Oncol 2012, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Melendez, T.; Boesen, T.; Jonassen, T.E.N. Translational advances of melanocortin drugs: Integrating biology, chemistry and genetics. Semin Immunol 2022, 59, 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, B.; Yin, C.; Liu, W.; Han, C.; Chen, B.; Liu, T.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; et al. Palmitoylation-dependent activation of MC1R prevents melanomagenesis. Nature 2017, 549, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejon-Grinan, M.; Herraiz, C.; Olivares, C.; Jimenez-Cervantes, C.; Garcia-Borron, J.C. cAMP-independent non-pigmentary actions of variant melanocortin 1 receptor: AKT-mediated activation of protective responses to oxidative DNA damage. Oncogene 2018, 37, 3631–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, C.P.; Ong, V.H. Targeted therapies for systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013, 9, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allanore, Y.; Simms, R.; Distler, O.; Trojanowska, M.; Pope, J.; Denton, C.P.; Varga, J. Systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015, 1, 15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, D.; Lin, C.J.F.; Furst, D.E.; Goldin, J.; Kim, G.; Kuwana, M.; Allanore, Y.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Distler, O.; Shima, Y.; et al. Tocilizumab in systemic sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020, 8, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distler, O.; Highland, K.B.; Gahlemann, M.; Azuma, A.; Fischer, A.; Mayes, M.D.; Raghu, G.; Sauter, W.; Girard, M.; Alves, M.; et al. Nintedanib for Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 2518–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; Suzuki, T.; Kawano, Y.; Kojima, S.; Miyashiro, M.; Matsumoto, A.; Kania, G.; Blyszczuk, P.; Ross, R.L.; Mulipa, P.; et al. Dersimelagon, a novel oral melanocortin 1 receptor agonist, demonstrates disease-modifying effects in preclinical models of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res Ther 2022, 24, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, B.J.; Reis, C.; Ho, W.M.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.H. Neuroprotective Strategies after Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 22368–22401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, A.; Gilland, E.; Bona, E.; Hagberg, H. Microglia activation after neonatal hypoxic-ischemia. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 1995, 84, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fu, S.; Liu, Y.; Luo, H.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Gao, M.; Cheng, Y.; Xie, Z. NDP-MSH binding melanocortin-1 receptor ameliorates neuroinflammation and BBB disruption through CREB/Nr4a1/NF-kappaB pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; McIntyre, K.W.; Gillooly, K.M.; Yang, Y.; Haycock, J.; Roberts, S.; Khanna, A.; Herpin, T.F.; Yu, G.; Wu, X.; et al. A selective small molecule agonist of the melanocortin-1 receptor inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine accumulation and leukocyte infiltration in mice. J Leukoc Biol 2006, 80, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Doycheva, D.M.; Gamdzyk, M.; Yang, Y.; Lenahan, C.; Li, G.; Li, D.; Lian, L.; Tang, J.; Lu, J.; et al. Activation of MC1R with BMS-470539 attenuates neuroinflammation via cAMP/PKA/Nurr1 pathway after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in rats. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, P.; Rami, M.; Nuutinen, S.; Santovito, D.; van der Vorst, E.P.C.; Guillamat-Prats, R.; Lyytikainen, L.P.; Raitoharju, E.; Oksala, N.; Ring, L.; et al. Melanocortin 1 Receptor Signaling Regulates Cholesterol Transport in Macrophages. Circulation 2017, 136, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, A.; Gatti, S.; Colombo, G.; Lipton, J.M. Targeting melanocortin receptors as a novel strategy to control inflammation. Pharmacol Rev 2004, 56, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinne, P.; Silvola, J.M.; Hellberg, S.; Stahle, M.; Liljenback, H.; Salomaki, H.; Koskinen, E.; Nuutinen, S.; Saukko, P.; Knuuti, J.; et al. Pharmacological activation of the melanocortin system limits plaque inflammation and ameliorates vascular dysfunction in atherosclerotic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014, 34, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, P.; Kadiri, J.J.; Velasco-Delgado, M.; Nuutinen, S.; Viitala, M.; Hollmen, M.; Rami, M.; Savontaus, E.; Steffens, S. Melanocortin 1 Receptor Deficiency Promotes Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E(-/-) Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2018, 38, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscowitz, A.E.; Asif, H.; Lindenmaier, L.B.; Calzadilla, A.; Zhang, C.; Mirsaeidi, M. The Importance of Melanocortin Receptors and Their Agonists in Pulmonary Disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 2019, 6, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spana, C.; Taylor, A.W.; Yee, D.G.; Makhlina, M.; Yang, W.; Dodd, J. Probing the Role of Melanocortin Type 1 Receptor Agonists in Diverse Immunological Diseases. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Srivastava, P.; Feng, D.; Lin, Y.; Vanderburg, C.R.; Xu, Y.; McLean, P.; Frosch, M.P.; Fisher, D.E.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; et al. Melanocortin 1 receptor activation protects against alpha-synuclein pathologies in models of Parkinson's disease. Mol Neurodegener 2022, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.K.; Funasaka, Y.; Slominski, A.; Ermak, G.; Hwang, J.; Pawelek, J.M.; Ichihashi, M. Production and release of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) derived peptides by human melanocytes and keratinocytes in culture: regulation by ultraviolet B. Biochim Biophys Acta 1996, 1313, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, E.; Trautinger, F.; Kock, A.; Schwarz, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Simon, M.; Ansel, J.C.; Schwarz, T.; Luger, T.A. Proopiomelanocortin-derived peptides are synthesized and released by human keratinocytes. J Clin Invest 1994, 93, 2258–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Malek, Z.; Scott, M.C.; Suzuki, I.; Tada, A.; Im, S.; Lamoreux, L.; Ito, S.; Barsh, G.; Hearing, V.J. The melanocortin-1 receptor is a key regulator of human cutaneous pigmentation. Pigment Cell Res 2000, 13 Suppl 8, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollmann, M.M.; Lamoreux, M.L.; Wilson, B.D.; Barsh, G.S. Interaction of Agouti protein with the melanocortin 1 receptor in vitro and in vivo. Genes Dev 1998, 12, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, S.G.; Harris, C.O.; Ittoop, O.R.; Nichols, J.S.; Parks, D.J.; Truesdale, A.T.; Wilkison, W.O. Agouti antagonism of melanocortin binding and action in the B16F10 murine melanoma cell line. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 10406–10411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candille, S.I.; Kaelin, C.B.; Cattanach, B.M.; Yu, B.; Thompson, D.A.; Nix, M.A.; Kerns, J.A.; Schmutz, S.M.; Millhauser, G.L.; Barsh, G.S. A -defensin mutation causes black coat color in domestic dogs. Science 2007, 318, 1418–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder, J.; Bartels, J.; Christophers, E.; Schroder, J.M. Isolation and characterization of human beta -defensin-3, a novel human inducible peptide antibiotic. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 5707–5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, B.D.; Ollmann, M.M.; Kang, L.; Stoffel, M.; Bell, G.I.; Barsh, G.S. Structure and function of ASP, the human homolog of the mouse agouti gene. Hum Mol Genet 1995, 4, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Willard, D.; Patel, I.R.; Kadwell, S.; Overton, L.; Kost, T.; Luther, M.; Chen, W.; Woychik, R.P.; Wilkison, W.O.; et al. Agouti protein is an antagonist of the melanocyte-stimulating-hormone receptor. Nature 1994, 371, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nix, M.A.; Kaelin, C.B.; Ta, T.; Weis, A.; Morton, G.J.; Barsh, G.S.; Millhauser, G.L. Molecular and functional analysis of human beta-defensin 3 action at melanocortin receptors. Chem Biol 2013, 20, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swope, V.B.; Jameson, J.A.; McFarland, K.L.; Supp, D.M.; Miller, W.E.; McGraw, D.W.; Patel, M.A.; Nix, M.A.; Millhauser, G.L.; Babcock, G.F.; et al. Defining MC1R regulation in human melanocytes by its agonist alpha-melanocortin and antagonists agouti signaling protein and beta-defensin 3. J Invest Dermatol 2012, 132, 2255–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.I.; Lerner, A.B. Amino-acid sequence of the alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. Nature 1957, 179, 1346–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruby, V.J.; Wilkes, B.C.; Hadley, M.E.; Al-Obeidi, F.; Sawyer, T.K.; Staples, D.J.; de Vaux, A.E.; Dym, O.; Castrucci, A.M.; Hintz, M.F.; et al. alpha-Melanotropin: the minimal active sequence in the frog skin bioassay. J Med Chem 1987, 30, 2126–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, T.K.; Sanfilippo, P.J.; Hruby, V.J.; Engel, M.H.; Heward, C.B.; Burnett, J.B.; Hadley, M.E. 4-Norleucine, 7-D-phenylalanine-alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone: a highly potent alpha-melanotropin with ultralong biological activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1980, 77, 5754–5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, M.E.; Marwan, M.M.; al-Obeidi, F.; Hruby, V.J.; Castrucci, A.M. Linear and cyclic alpha-melanotropin [4-10]-fragment analogues that exhibit superpotency and residual activity. Pigment Cell Res 1989, 2, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Obeidi, F.; Castrucci, A.M.; Hadley, M.E.; Hruby, V.J. Potent and prolonged acting cyclic lactam analogues of alpha-melanotropin: design based on molecular dynamics. J Med Chem 1989, 32, 2555–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, G.; Todd, C.; Cresswell, J.E.; Thody, A.J. Alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone and its analogue Nle4DPhe7 alpha-MSH affect morphology, tyrosinase activity and melanogenesis in cultured human melanocytes. J Cell Sci 1994, 107 ( Pt 1) Pt 1, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, G.; Kyne, S.; Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K.; Todd, C.; Thody, A. Eumelanin and phaeomelanin contents of human epidermis and cultured melanocytes. Pigment Cell Res 1995, 8, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorr, R.T.; Dvorakova, K.; Brooks, C.; Lines, R.; Levine, N.; Schram, K.; Miketova, P.; Hruby, V.; Alberts, D.S. Increased eumelanin expression and tanning is induced by a superpotent melanotropin [Nle4-D-Phe7]-alpha-MSH in humans. Photochem Photobiol 2000, 72, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langendonk, J.G.; Balwani, M.; Anderson, K.E.; Bonkovsky, H.L.; Anstey, A.V.; Bissell, D.M.; Bloomer, J.; Edwards, C.; Neumann, N.J.; Parker, C.; et al. Afamelanotide for Erythropoietic Protoporphyria. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, A.M.; McKay, J.T.; Bonkovsky, H.L. Advances in the management of erythropoietic protoporphyria - role of afamelanotide. Appl Clin Genet 2016, 9, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, M.E.; Hruby, V.J.; Blanchard, J.; Dorr, R.T.; Levine, N.; Dawson, B.V.; al-Obeidi, F.; Sawyer, T.K. Discovery and development of novel melanogenic drugs. Melanotan-I and -II. Pharm Biotechnol 1998, 11, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessells, H.; Hruby, V.J.; Hackett, J.; Han, G.; Balse-Srinivasan, P.; Vanderah, T.W. Ac-Nle-c[Asp-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-Lys]-NH2 induces penile erection via brain and spinal melanocortin receptors. Neuroscience 2003, 118, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessells, H.; Levine, N.; Hadley, M.E.; Dorr, R.; Hruby, V. Melanocortin receptor agonists, penile erection, and sexual motivation: human studies with Melanotan II. Int J Impot Res 2000, 12 Suppl 4, S74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossler, A.S.; Pfaus, J.G.; Kia, H.K.; Bernabe, J.; Alexandre, L.; Giuliano, F. The melanocortin agonist, melanotan II, enhances proceptive sexual behaviors in the female rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2006, 85, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, L.E.; Earle, D.C.; Garcia, W.D.; Spana, C. Co-administration of low doses of intranasal PT-141, a melanocortin receptor agonist, and sildenafil to men with erectile dysfunction results in an enhanced erectile response. Urology 2005, 65, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadiack, A.M.; Sharma, S.D.; Earle, D.C.; Spana, C.; Hallam, T.J. Melanocortins in the treatment of male and female sexual dysfunction. Curr Top Med Chem 2007, 7, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugo, W.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Sun, L.; Song, C.; Moreno, B.H.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Berent-Maoz, B.; Pang, J.; Chmielowski, B.; Cherry, G.; et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Features of Response to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma. Cell 2016, 165, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

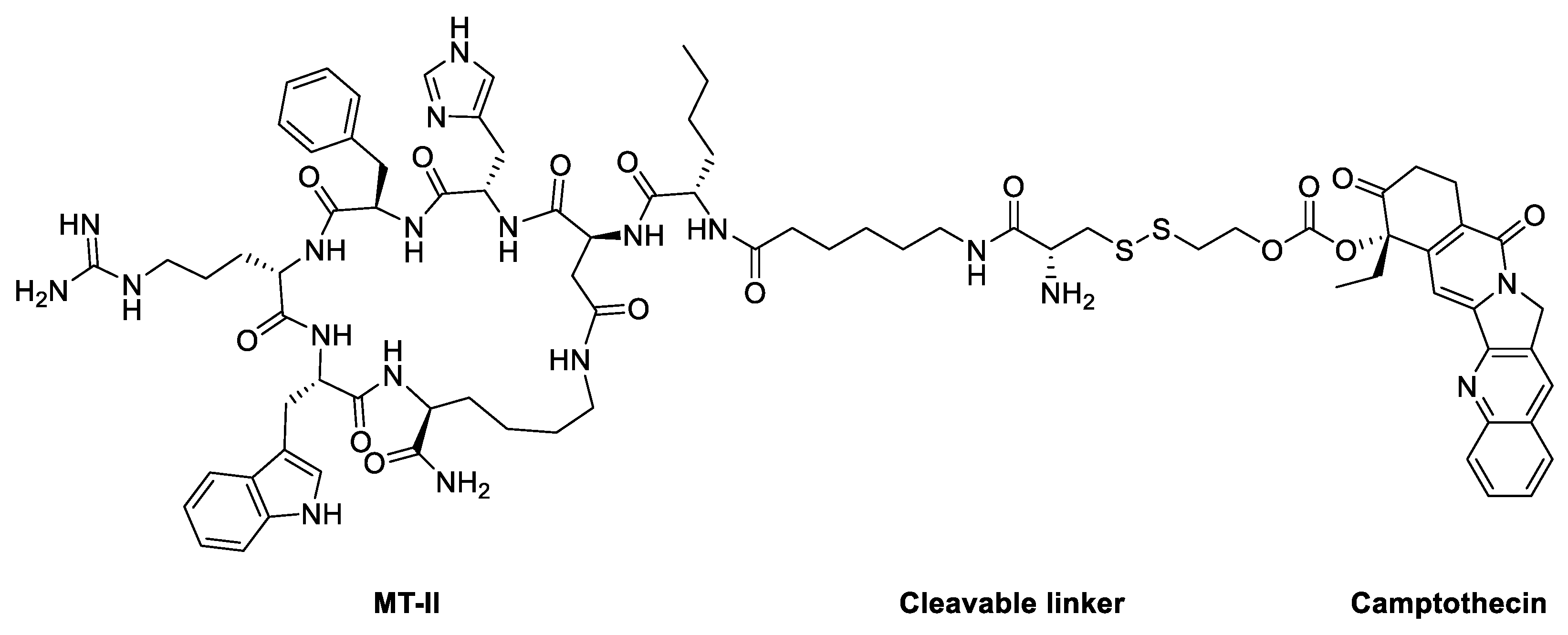

- Zhou, Y.; Mowlazadeh Haghighi, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Hruby, V.J.; Cai, M. Development of Ligand-Drug Conjugates Targeting Melanoma through the Overexpressed Melanocortin 1 Receptor. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2020, 3, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minder, E.I. Afamelanotide, an agonistic analog of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, in dermal phototoxicity of erythropoietic protoporphyria. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2010, 19, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskell-Luevano, C.; Rosenquist, A.; Souers, A.; Khong, K.C.; Ellman, J.A.; Cone, R.D. Compounds that activate the mouse melanocortin-1 receptor identified by screening a small molecule library based upon the beta-turn. J Med Chem 1999, 42, 4380–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpin, T.F.; Yu, G.; Carlson, K.E.; Morton, G.C.; Wu, X.; Kang, L.; Tuerdi, H.; Khanna, A.; Tokarski, J.S.; Lawrence, R.M.; et al. Discovery of tyrosine-based potent and selective melanocortin-1 receptor small-molecule agonists with anti-inflammatory properties. J Med Chem 2003, 46, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, A., T.E.N. Jonassen, and T. Lundstedt, Phenyl pyrrole aminoguanidine derivatives. 2007, WO2007141343.

- Bouix-Peter, C., Oxazetidine derivatives, process for preparing them and use in human medicine and in cosmetics. 2013, WO2013001030.

- Eisinger, M.; Li, W.H.; Anthonavage, M.; Pappas, A.; Zhang, L.; Rossetti, D.; Huang, Q.; Seiberg, M. A melanocortin receptor 1 and 5 antagonist inhibits sebaceous gland differentiation and the production of sebum-specific lipids. J Dermatol Sci 2011, 63, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ju, W.; Tin, T.D.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.S.; Park, C.H.; Kwak, S.H. Effect of BMS-470539 on lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil activation. Korean J Anesthesiol 2020, 73, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Kawano, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Kondo, M.; Funayama, K.; Tanemura, S.; Miyashiro, M.; Nishi, A.; Yamada, K.; Tsuda, M.; et al. Melanogenic effect of dersimelagon (MT-7117), a novel oral melanocortin 1 receptor agonist. Skin Health Dis 2022, 2, e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstedt, T., et al., N-phenylpyrrole guanidine derivatives as melanocortin receptor ligands. 2008, US7442807.

- Montero-Melendez, T.; Gobbetti, T.; Cooray, S.N.; Jonassen, T.E.; Perretti, M. Biased agonism as a novel strategy to harness the proresolving properties of melanocortin receptors without eliciting melanogenic effects. J Immunol 2015, 194, 3381–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiteau, J.G.; Rodeville, N.; Martin, C.; Tabet, S.; Moureou, C.; Muller, F.; Jetha, J.C.; Cardinaud, I. Development of a Kilogram-Scale Synthesis of a Novel MC1R Agonist. Organic Process Research & Development 2015, 19, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, W.H.; Anthonavage, M.; Eisinger, M. Melanocortin-5 receptor: a marker of human sebocyte differentiation. Peptides 2006, 27, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfield, R.L.; Wu, P.P.; Ciletti, N. Sebaceous epithelial cell differentiation requires cyclic adenosine monophosphate generation. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2002, 38, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Anthonavage, M.; Huang, Q.; Li, W.H.; Eisinger, M. Proopiomelanocortin peptides and sebogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003, 994, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouboulis, C.C. Acne and sebaceous gland function. Clin Dermatol 2004, 22, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Schagen, S.; Alestas, T. The sebocyte culture: a model to study the pathophysiology of the sebaceous gland in sebostasis, seborrhoea and acne. Arch Dermatol Res 2008, 300, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiboutot, D.; Gollnick, H.; Bettoli, V.; Dreno, B.; Kang, S.; Leyden, J.J.; Shalita, A.R.; Lozada, V.T.; Berson, D.; Finlay, A.; et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009, 60, S1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).