Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

23 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

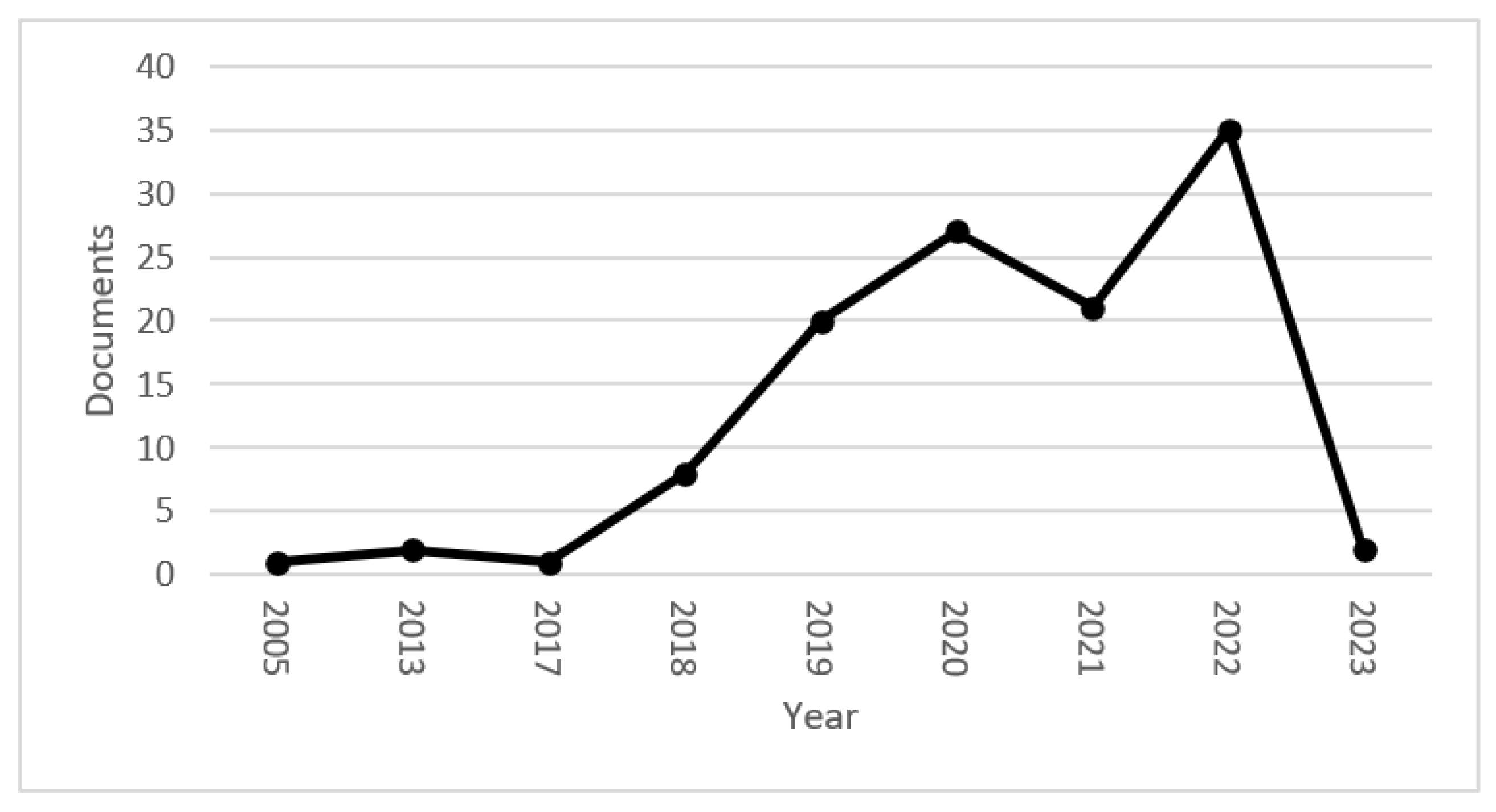

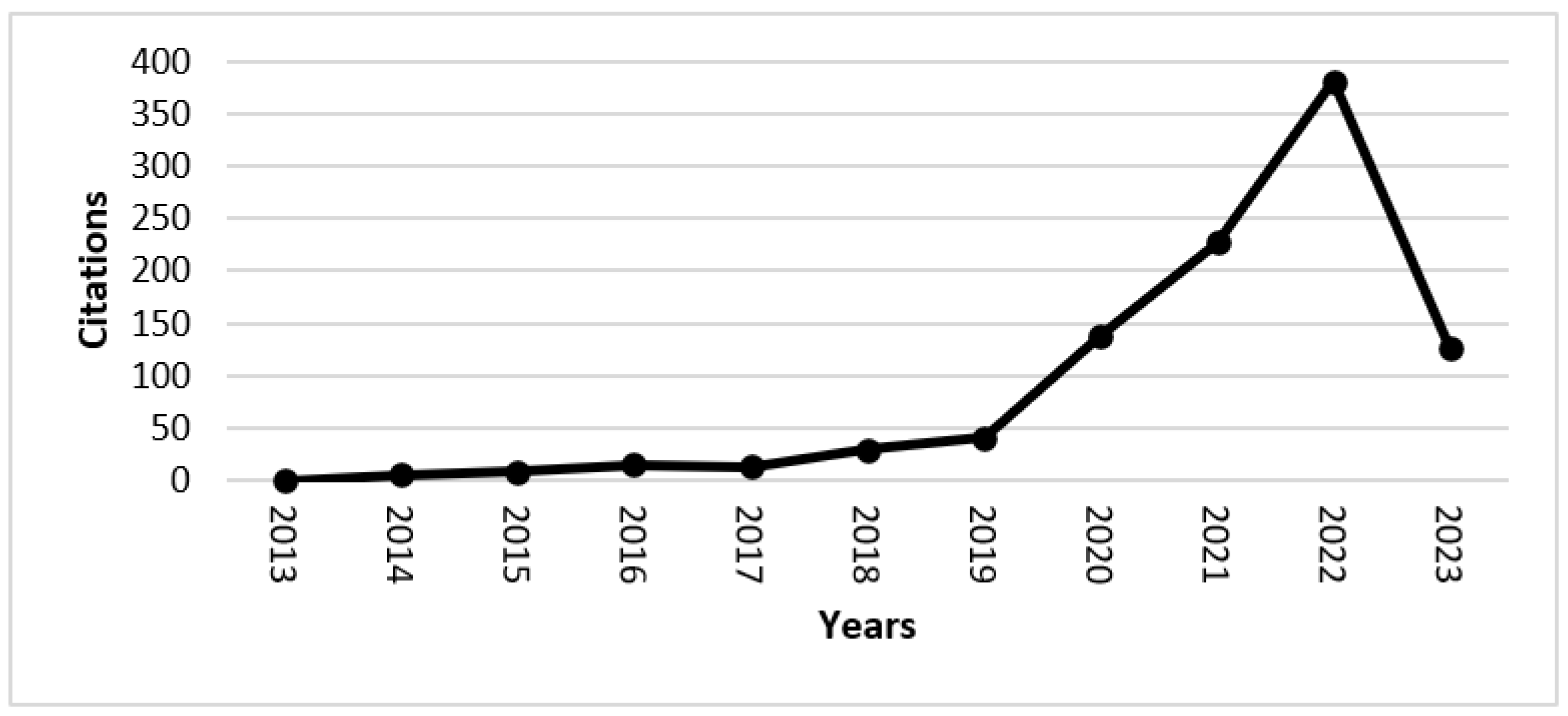

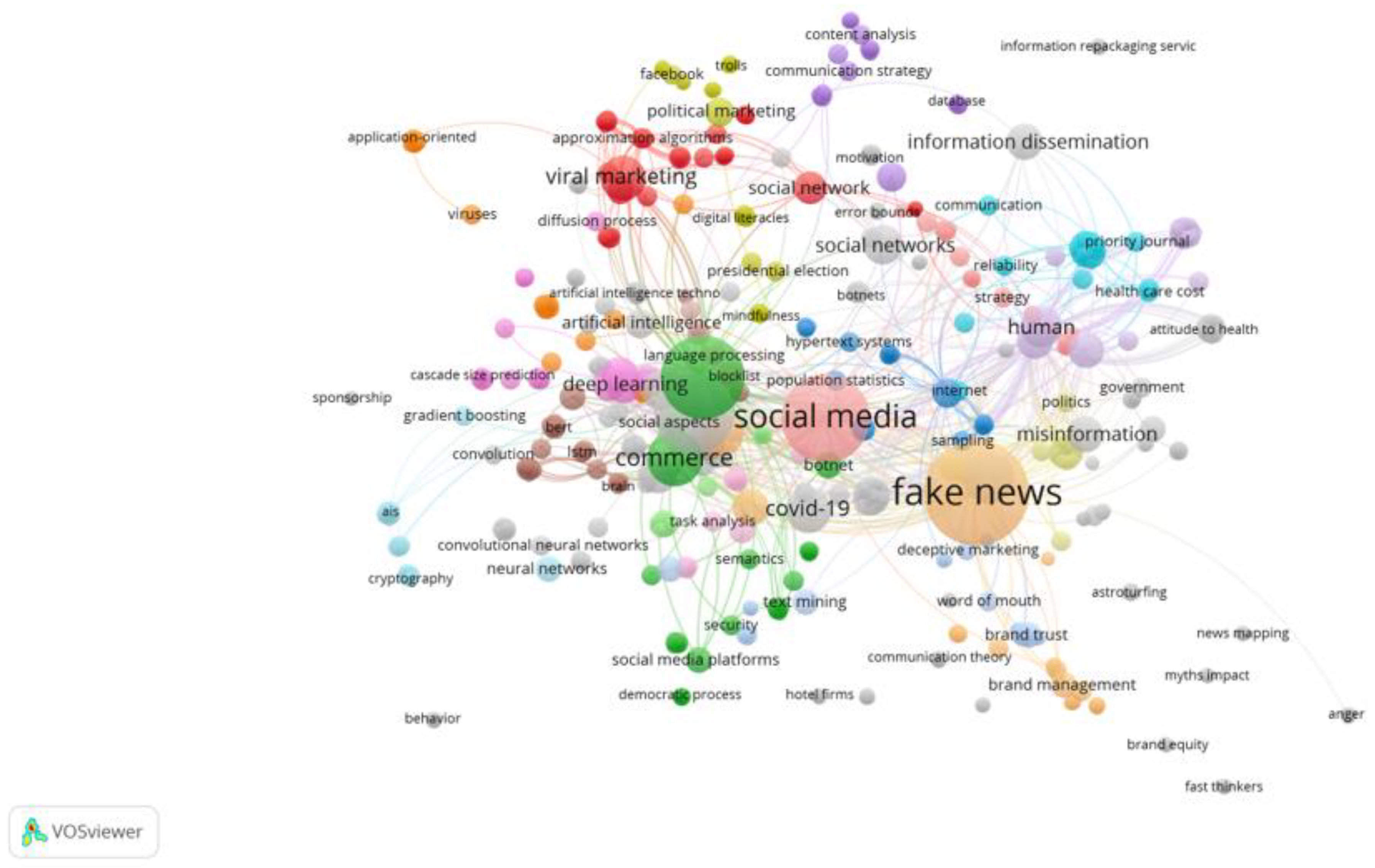

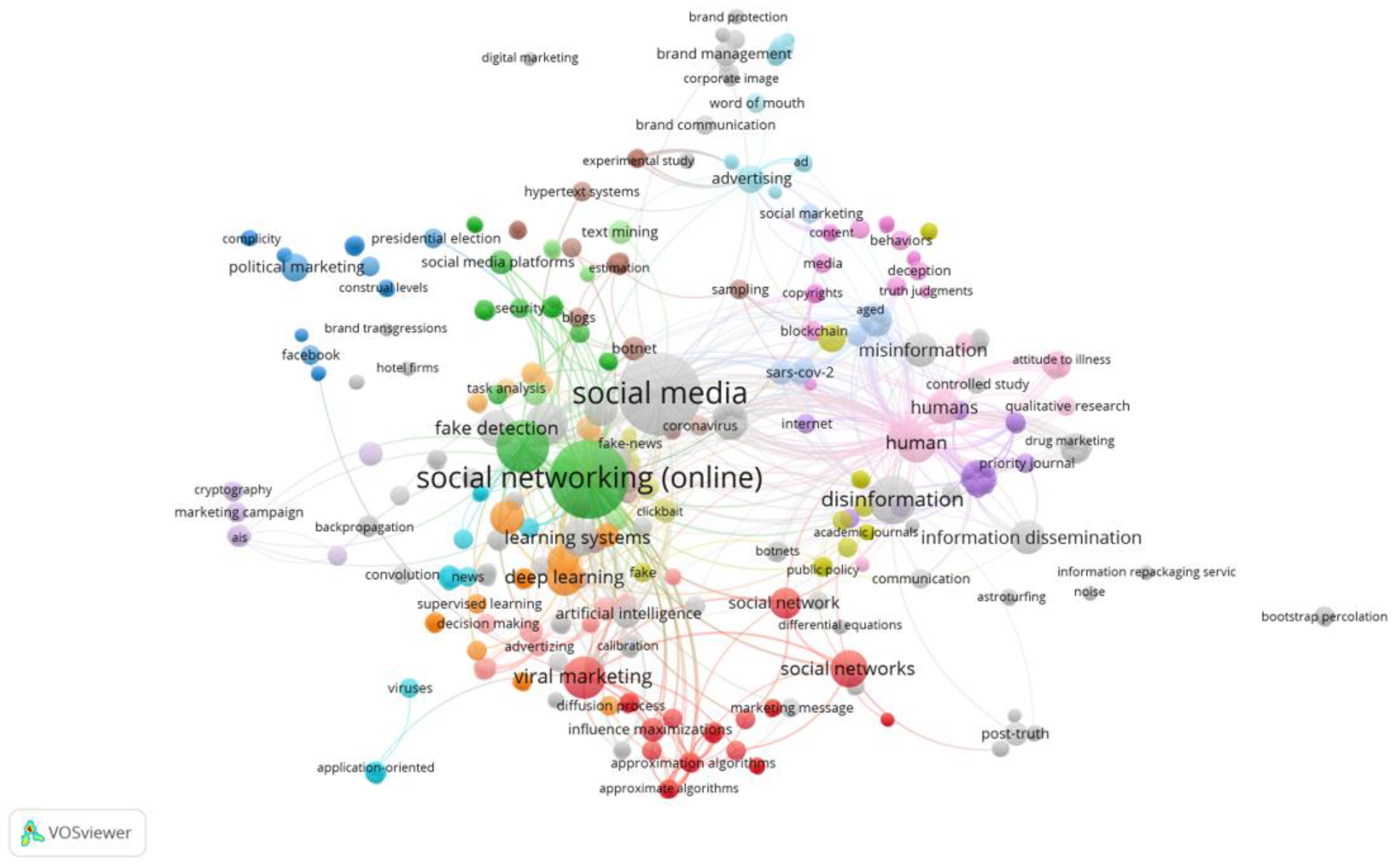

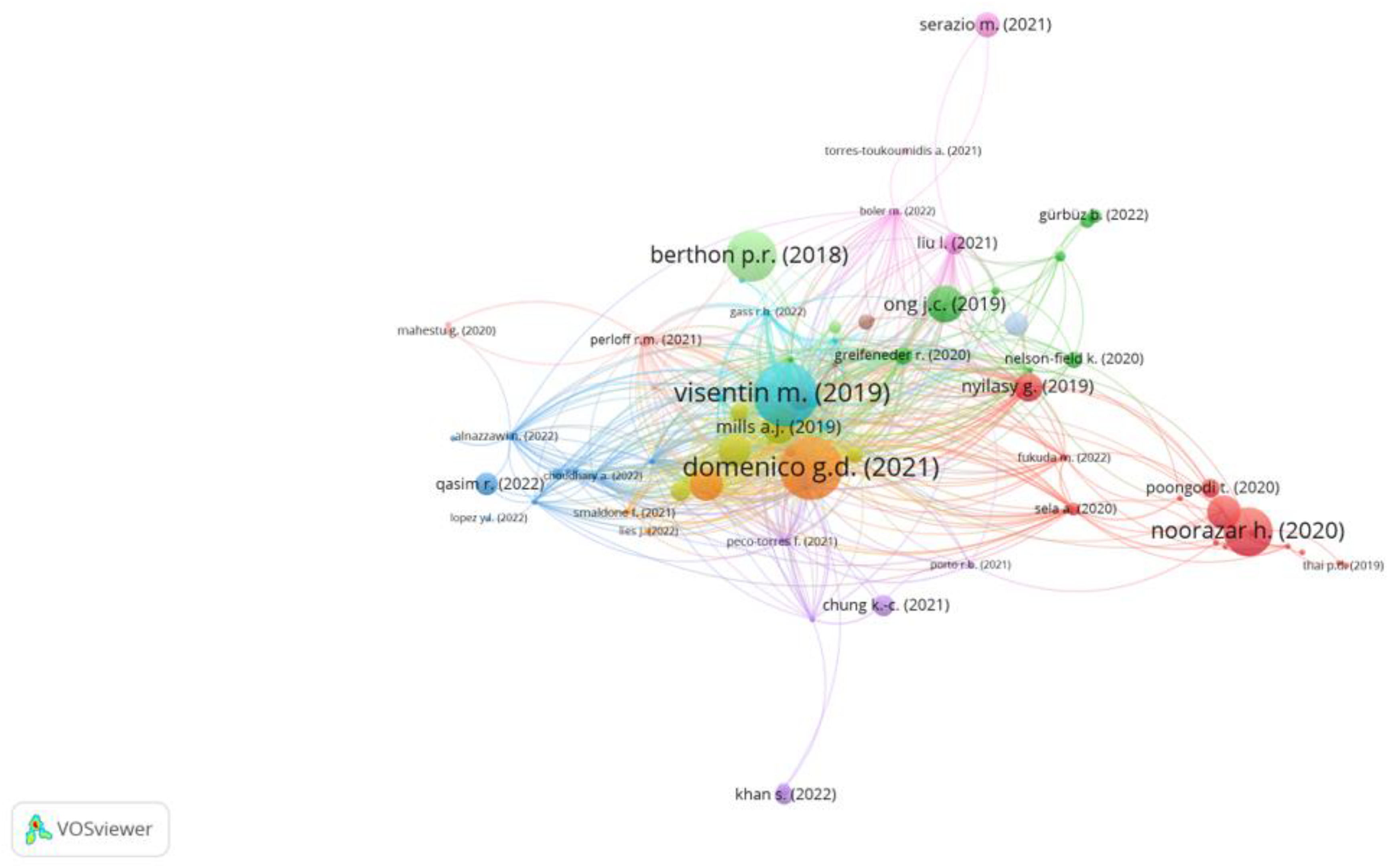

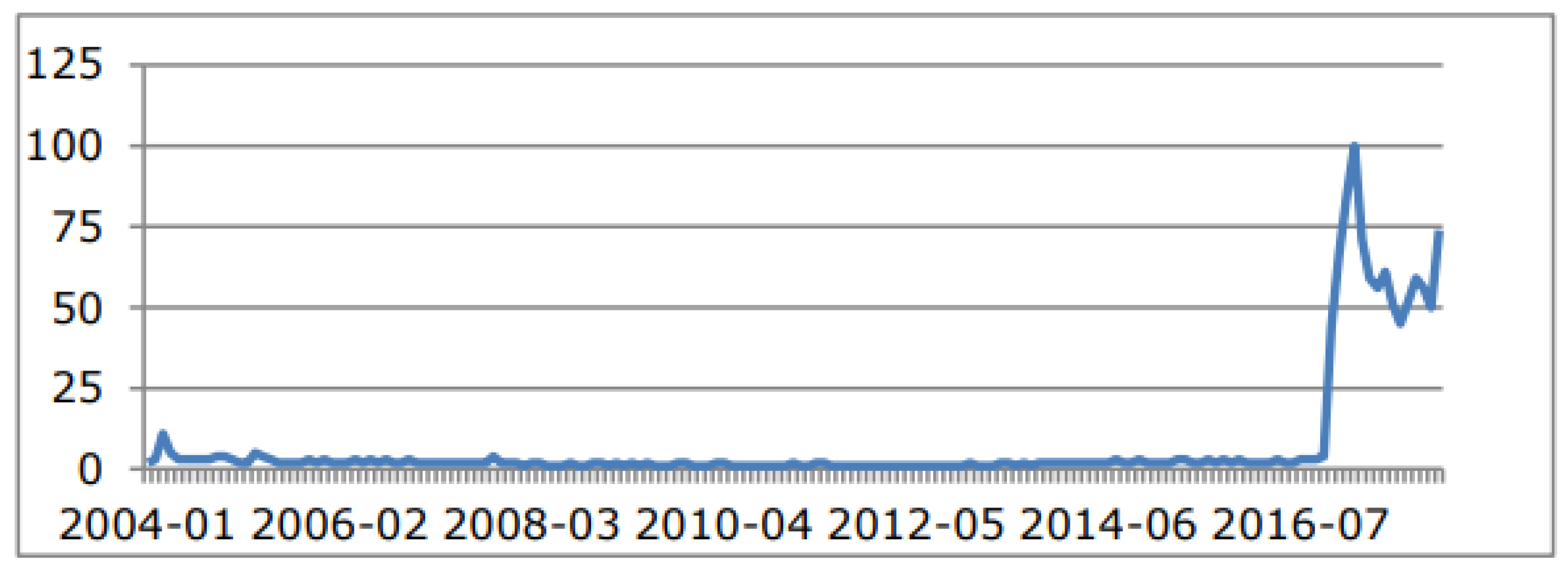

3. Literature analysis: themes and trends

4. Theoretical perspectives

4.1. Definition of Fake News

4.2. Types of Fake News

4.2.1. Disinformation

4.2.2. Misinformation

4.2.3. Malinformation

4.2.4. Commentaries and opinions

4.2.5. Clickbait and conspiracy theories

4.2.6. Rumors

4.2.7. Sensationalism

4.3. The Prevalence of Fake News in Marketing

4.4. Causes of Fake News in Marketing

4.4.1. Profit-driven motives of businesses

4.4.2. Lack of regulation in the advertising industry

4.4.3. Confirmation bias among consumers

4.4.4. Social media algorithms that prioritize engagement over the accuracy

4.5. Technologies for Analyzing and Detecting Fake News in Marketing

4.5.1. Artificial Intelligence (A.I.)

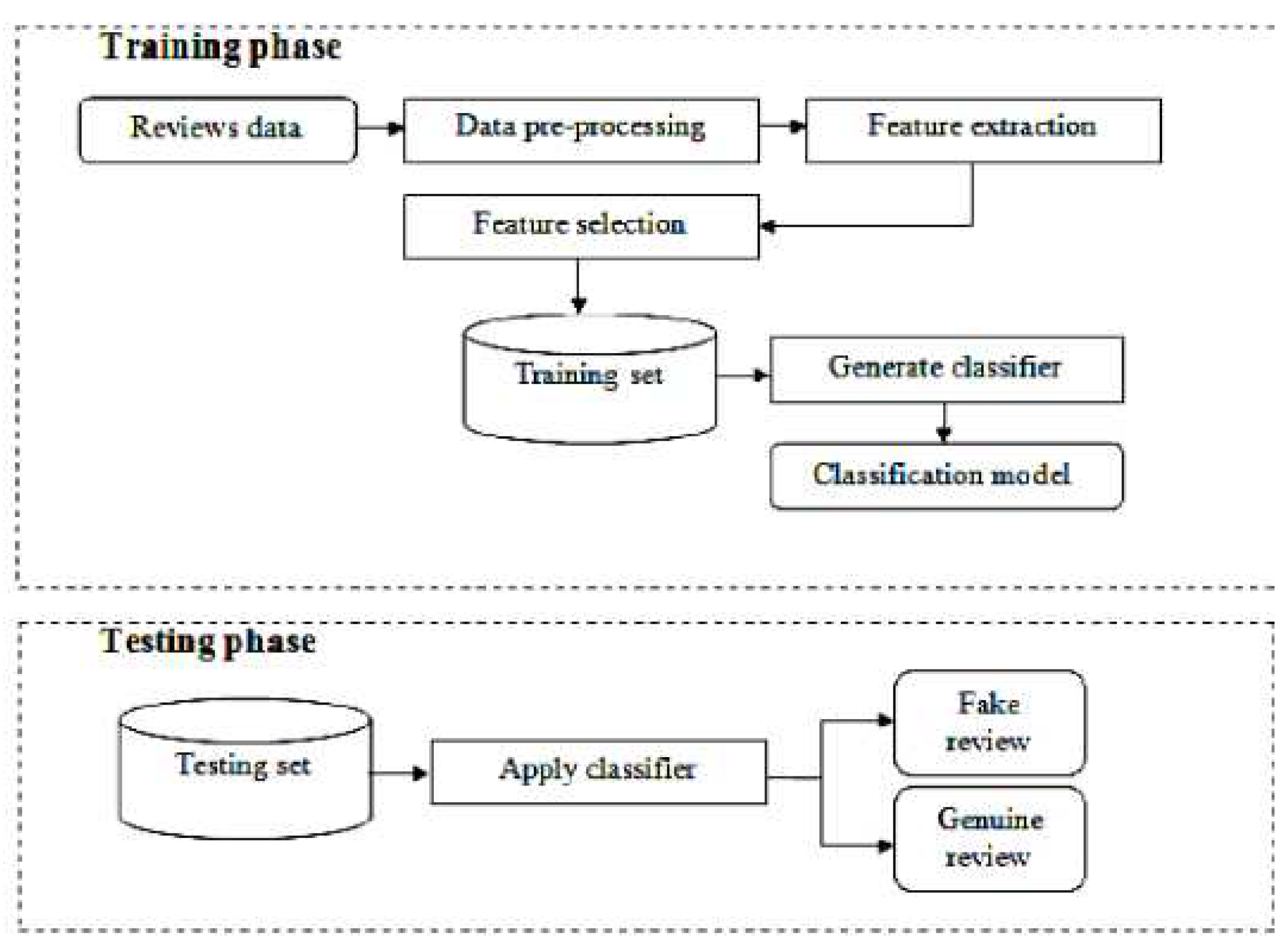

4.5.2. Machine Learning

4.6. The Impact of Fake News on Brand Equity, Consumer Trust and Experiences

4.7. Impact of Fake News on Firm Performance

4.8. Ethical and Legal Implications of Fake News in Marketing

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Documents | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixing fake news: Understanding and managing the marketer-co ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Approximate Algorithms for Data-Driven lnfluence Limitation | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| What to believe, whom to biame, and when to share: exploring .. | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Noise, Fake News, and Tenacious Bayesians | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| The fake news effect: what does it mean for consume, behavio ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Using Social Media to Detect Fake News lnformation Related t ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Understanding Factors to COVID-19 Vaccine Adoption in Gujara ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Artificial lntelligence Model to Predict the Virality of Pre ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| MetaGeo: A General Framework for Social User Geolocation Ide ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Can you be Mindful? The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Driven ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Estimating the Bot Population on Twitter via Random Walk Bas ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| A Fine-Tuned BERT-Based Transfer Learning Approach forText ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | 2 | 13 |

| Cryptonight mining algorithm with yac consensus for social m ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| lnstitutional Advertising in the Face ofCOVID-19 Hoaxes: St... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| ln These Uncertain limes: Fake News Amplifies the Desires to ... | 2022 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| War on Diabetes in Singapore: a policy analysis | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Tourísts’ information literacy self-efficacy: its role in th ... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | 2 |

| Launcher nodes for detecting efficient influencers insocial ... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 |

| A survey for the application of blockchain technology in the ... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | 4 | 11 |

| Evolutionary Computation in Social Propagation over Complex ... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | 2 |

| The dynamics of political communication: Media and politics ... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | - | 4 |

| Social media privacy management strategies: A SEM ... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 7 | 1 | 11 |

| The other ‘fake’ news: Professional ideais and objectiv... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 15 |

| The Effects of Fake News on Consumers’ Brand Trust: An Ex... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | - | 3 |

| Fight Against Corona: Exploring Consumer-Brand Relationship ... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Online influencers: Healthy food or fake news | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | - | 4 |

| Accountability Journalism During the Emergence of COVID-19: ... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Challenging post-communication: Beyond focus on a ‘few bad a ... | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Fake news, social media and marketing: A systematic review | 2021 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 16 | 53 | 24 | 94 |

| lnterdisciplinary Lessons Learned While Researching Fake New ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 6 | - | 7 |

| IMPACT OF FAKE NEWS ANO MYTHS RELATED TO COVID-19 | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Entrepreneurial marketing and digital political communicatio ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Marketing of identity politics in digital world (netnography ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | 2 |

| Fake news or true lies? Reflections about problematic conten ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 27 |

| Daley--Kendal models in fake-news scenario | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 3 | - | 5 |

| Recent advances in opinion propagation dynamics: a 2020... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 18 | 29 | 5 | 56 |

| [Why does fake news have space on social media? A discussion ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 2 |

| Fake news and brand management: a Delphi study of ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 13 |

| A false image of health: how fake news and pseudo-facts spre ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| The truth (as I see it): philosophical considerations infl... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 1 | 3 | - | 8 |

| lnvestigating the emotional appeal of fake news using artif ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 25 |

| A trust model for spreading gossip insocial networks: A mui. .. | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 3 | - | 4 |

| lmproving information spread by spreading groups | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 3 | - | 4 |

| What is new and truel about fake news? | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Blockchain in Social Networking | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 |

| The effect of fake news in marketing halal food: a moderatin ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 8 | 1 | 10 |

| The attention economy and how media works: Sim pie truths for ... | 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 2 | 1 | 7 | |

| Hepatitis E vaccine in China: Public health professional per. .. | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 3 | - | - | 5 |

| Fraudulent News Detection using Machine Learning Approaches | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | 3 | |

| Does Deceptive Marketing Pay? The Evolution of Consumer... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | - | 14 |

| lnformation cascades modeling via deep multi-task learning | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 10 | 12 | 2 | 27 |

| Transformations of Professional Political Communications in ... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | 3 |

| Using Social Networks to Detect Malicious Bangla Text Conten ... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 4 | 7 | - | 15 |

| lnformation diffusion prediction via recurrent cascades conv ... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | 22 | 35 | 10 | 78 |

| The relationship between fake news... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 25 |

| Fake news: When the dark side of persuasion takes over | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 20 |

| Fake News, Real Problems for Brands: The lmpact of Content T ... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 12 | 31 | 37 | 15 | 97 |

| [Fake news: The new power in the post-truth era, Noticias fa ... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | ||||

| When Disinformation Studies Meets Production Studies: Social... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | 9 | 13 | 2 | 32 |

| Hop-based sketch for large-scale infiuence analysis | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| [Presidential campaign in post-truth era: lnnovative digital. .. | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | 1 | - | 3 |

| The Effectiveness, reasons and problems in current awareness ... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 3 |

| Understanding Online Trust and lnformation Behavior Using De ... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| NLP based sentiment analysis forTwitter’s opinion mining an ... | 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | 2 |

| [Death of the traditional newspaper: A strategic assess... | 2018 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Oncology, “fake” news, and legal liability | 2018 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 5 | 2 | - | 9 |

| Brands, Truthiness and Post-Fact: Managing Brands in a Post- ... | 2018 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 4 | 22 | 11 | 14 | 7 | 62 |

| Marketing libraries in an era of”Fake news” | 2018 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 15 | |

| The ethics of psychometrics insocial media: A Rawlsian appr. .. | 2018 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Fake news and social media: The role of the receiver | 2018 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 1 | - | - | 4 |

| Disinformation, dystopia and post-reality insocial media: A ... | 2018 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | 2 |

| Contrasting the spread of misinformation in online social ne ... | 2017 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 26 |

| Battling the Internet water army: Detection of hidden paid p ... | 2013 | - | 5 | 8 | 15 | 22 | 12 | 22 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 117 |

| Total | 0 | 5 | 8 | 15 | 23 | 19 | 41 | 137 | 224 | 381 | 127 | 984 |

References

- Ummah, N.H.; Fajri MS, A. Communication strategies used in teaching media information literacy for combating hoaxes in indonesia: A case study of indonesian national movements. [Komunikacijos strategijos ir medijų informacijos raštingumas kovojant prieš melagingas žinias Indonezijoje: Indonezijos visuomeninių judėjimų pavyzdžiai] Informacijos Mokslai, 2020, 90, 26-41. [CrossRef]

- Alnazzawi, N.; Alsaedi, N.; Alharbi, F.; Alaswad, N. Using social media to detect fake news information related to product marketing: the fakeAds corpus. Data, 2022, 7, 44. [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, G.; Sit, J.; Ishizaka, A.; Nunan, D. Fake news, social media and marketing: A systematic review. Journal of Business Research, 2021, 124, 329-341. [CrossRef]

- Martens, B.; Aguiar, L.; Gomez-Herrera, E.; Mueller-Langer, F. The digital transformation of news media and the rise of disinformation and fake news. Digital Economy Working, 2018, Paper 2018-02, Joint Research Centre Technical Reports. [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, G.; Visentin, M. Fake news or true lies? Reflections about problematic contents in marketing. International Journal of Market Research, 2020, 62, 409-417. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Sánchez, M.A.; Palos-Sánchez, P.R.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A. Systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis on virtual reality and education. Education and Information Technologies, 2023, 28, 155-192. [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Marrone, M.; Singh, A.K. Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Australian Journal of Management, 2020, 45, 175-194. [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. How Industry 4.0 and Sensors Can Leverage Product Design: Opportunities and Challenges. Sensors 2023, 23, 1165. [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. Sustainability and the Digital Transition: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimundo, R.; Rosário, A. Blockchain System in the Higher Education. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozarth, L.; Budak, C. Market forces: Quantifying the role of top credible ad servers in the fake news ecosystem. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. 2021, Vol. 15; pp. 83–94.

- Corzo CA, R. Fake news: The new power in the post-truth era. [Noticias falsas: El nuevo poder en la era de la posverdad]. Opcion, 35, Special Edition. 2019, 25, 364-413.

- Sousa, B.B.; Silva, M.S.; Veloso, C.M. The quality of communication and fake news in tourism: A segmented perspective. Quality - Access to Success. 2020, 21, 101-105.

- de Regt, A.; Montecchi, M.; Lord Ferguson, S. A false image of health: How fake news and pseudo-facts spread in the health and beauty industry. Journal of Product and Brand Management. 2020, 29, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N.; Shea, E. Marketing libraries in an era of “fake news”. Reference and User Services Quarterly. 2018, 57, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabchenko, N.A.; Malysheva, O.P.; Gnedash, A.A. Presidential campaign in post-truth era: Innovative digital technologies of political content management in social networks politics. [Управление Пoлитическим Кoнтентoм В Сoциальных Сетях В Периoд Предвыбoрнoй Кампании В Эпoху Пoстправды] Polis (Russian Federation). 2019, (2), 92-106. [CrossRef]

- Perloff, R.M. The dynamics of political communication: Media and politics in a digital age. The dynamics of political communication: Media and politics in a digital age. 2021, pp. 1-512. [CrossRef]

- Brody, D.C. Noise, fake news, and tenacious bayesians. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmanian, E. Fake news: A classification proposal and a future research agenda. Spanish Journal of Marketing – ESIC. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Flostrand, A.; Pitt, L.; Kietzmann, J. Fake news and brand management: A Delphi study of impact, vulnerability and mitigation. Journal of Product and Brand Management. 2020, 29, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flostrand, A.; Wallstrom, Å.; Salehi-Sangari, E.; Pitt, L.; Kietzmann, J. Fake news and the top high-tech brands: A Delphi study of familiarity, vulnerability and effectiveness: An abstract. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pomerance, J.; Light, N.; Williams, L.E. In these uncertain times: Fake news amplifies the desires to save and spend in response to COVID-19. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research. 2022, 7, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.C.; Robertson, J.; Kirsten, M. The truth (as I see it): Philosophical considerations influencing a typology of fake news. Journal of Product and Brand Management. 2020, 29, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Framewala, A.; Patil, A.; Kazi, F. Shapley based interpretable semi-supervised model for detecting similarity index of social media campaigns. Paper presented at the Proceedings - 2020 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence, 270-274., CSCI 2020. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Nakajima, K.; Shudo, K. Estimating the bot population on Twitter via random walk-based sampling. IEEE Access. 2022, 10, 17201–17211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G. Fake news: When the dark side of persuasion takes over. International Journal of Advertising. 2019, 38, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarda, R.F.; Ohlson, M.P.; Romanini, A.V. Disinformation, dystopia and post-reality in social media: A semiotic-cognitive perspective. Education for Information. 2018, 34, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J. Online astroturfing: A problem beyond disinformation. Philosophy and Social Criticism. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.C.; Cabañes JV, A. When disinformation studies meet production studies: Social identities and moral justifications in the political trolling industry. International Journal of Communication. 2019, 13, 5771–5790. [Google Scholar]

- Amoruso, M.; Auletta, V.; Anello, D.; Ferraioli, D. Contrasting the spread of misinformation in online social networks. In Paper presented at the Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, 3 1323-1331, AAMAS. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greifeneder, R.; Jaffé, M.E.; Newman, E.J.; Schwarz, N. What is new and true1 about fake news? The psychology of fake news: Accepting, sharing, and correcting misinformation. 2020, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, X. Topic-aware popularity and retweeter prediction model for cascade study. Paper presented at the Proceedings - 2022 IEEE 9th International Conference on Cyber Security and Cloud Computing and 2022 IEEE 8th International Conference on Edge Computing and Scalable Cloud, 172-179., CSCloud-EdgeCom 2022. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Latif, S.; Ahmed, N. Using social networks to detect malicious Bangla text content. Paper presented at the 1st International Conference on Advances in Science, ICASERT 2019. 2019., Engineering and Robotics Technology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, J. Habituation effect in social networks as a potential factor silently crushing influence maximisation efforts. Scientific Reports. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ghalibi, M.; Al-Azzawi, A.; Lawonn, K. NLP based sentiment analysis for twitter’s opinion mining and visualization. Paper presented at the Proceedings of SPIE - the International Society for Optical Engineering; 1104. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Seoane, J.; Corbacho-Valencia, J. Institutional advertising in the face of COVID-19 hoaxes: Strategies, messages and narratives in the Spanish case. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Noorazar, H. Recent advances in opinion propagation dynamics: A 2020 survey. European Physical Journal Plus. 2020, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ow Yong, L.M.; Koe LW, P. War on diabetes in Singapore: A policy analysis. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Huang, Y. Intelligent clickbait news detection system based on artificial intelligence and feature engineering. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Nguyen, U.T. An attention-based neural network using human semantic knowledge and its application to clickbait detection. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society. 2022, 3, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serazio, M. The other ‘fake’ news: Professional ideals and objectivity ambitions in brand journalism. Journalism. 2021, 22, 1340–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, V. Fake news and social media: The role of the receiver. In Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Social Media, 62-68., ECSM 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Govindankutty, S.; Gopalan, S.P. SEDIS—A rumor propagation model for social networks by incorporating the human nature of selection. Systems. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, B.; Mawengkang, H.; Husein, I.; Weber, G. Rumour propagation: An operational research approach by computational and information theory. Central European Journal of Operations Research. 2022, 30, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolia, V.; Singh, R.R.; Deshpande, S.; Dave, A.; Rathod, R.M. Understanding factors to COVID-19 vaccine adoption in Gujarat, India. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempster, G.; Sutherland, G.; Keogh, L. Scientific research in news media: a case study of misrepresentation, sensationalism and harmful recommendations. Journal of Science Communication. 2022, 21, A06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Zain-ul-abdin, K.; Li, C.; Johns, L.; Ali, A.A.; Carcioppolo, N. Viruses going viral: Impact of fear-arousing sensationalist social media messages on user engagement. Science Communication. 2019, 41, 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, P.R.; Pitt, L.F. Brands, truthiness and post-fact: Managing brands in a post-rational world. Journal of Macromarketing. 2018, 38, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, A.; Farah, M.F.; Ramadan, Z. What to believe, whom to blame, and when to share: Exploring the fake news experience in the marketing context. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2022, 39, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahestu, G.; Sumbogo, T.A. Marketing of identity politics in digital world (netnography study on Indonesian presidential election 2019). Paper presented at the Proceedings of 2020 International Conference on Information Management and Technology, 693-698., ICIMTech 2020. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, B.C.; Borges, J. Why does fake news have space on social media? A discussion in the light of infocommunicational behavior and digital marketing. [Por que as fake news têm espaço nas mídias sociais? Uma discussão a luz do comportamento infocomunicacional e do marketing digital] Informacao e Sociedade. 2020, 30. [CrossRef]

- Nigam, S.; Bang, M. Airline marketing or fake news? Airline Business. 2018, 34, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson-Field, K. The attention economy and how media works: Simple truths for marketers. The attention economy and how media works: Simple truths for marketers. 2020, pp. 1-152. [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.J.; Pitt, C.; Ferguson, S.L. The relationship between fake news and advertising: Brand management in the era of programmatic advertising and prolific falsehood. Journal of Advertising Research. 2019, 59, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, R.B.; de Moura, A.F.; Aragão, L.M.; Borges, C.P. Electoral marketing from the perspective of behavioral psychology: Effect on voters and voting in executive and legislative positions. [Marketing eleitoral na perspectiva da psicologia comportamental: Efeito no eleitor e no voto em cargos do executivo e legislativo] Revista Brasileira De Marketing. 2021, 20. [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Kim, H.; Lee, G.M.; Jang, S. Does deceptive marketing pay? the evolution of consumer sentiment surrounding a pseudo-product-harm crisis. Journal of Business Ethics. 2019, 158, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, K.; Beuk, F.; Bal, A.; Zhu, Z. Fake news and the willingness to share: The role of confirmatory bias and previous brand transgressions: An abstract. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.; Martins, F.A. Launcher nodes for detecting efficient influencers in social networks. Online Social Networks and Media, 25. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, C.; Da Costa, R.L.; Dias Á, L.; Pereira, L.; Santos, J.P. Online influencers: Healthy food or fake news. International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising. 2021, 15, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Monzoncillo, J.M. The dynamics of influencer marketing: A multidisciplinary approach. The dynamics of influencer marketing: A multidisciplinary approach. 2022, pp. 1-210. [CrossRef]

- Amoncar, N. Entrepreneurial marketing and digital political communication – a citizen-led perspective on the role of social media in political discourse. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship. 2020, 22, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, C.L.; Mendieta, C. Micro-targeting and non-profit marketing: Loss of serendipity or effective strategy? Paper presented at the 8th European Conference on Social Media, ECSM 2021. 2021; 41-49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lies, J. Marketing intelligence: Boom or bust of service marketing? International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence. 2022, 7, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LotRiet, R. Death of the traditional newspaper: A strategic assessment. [Die dood van die tradisionele koerant:’n Strategiese assessering] Tydskrif Vir Geesteswetenskappe. 2018, 58, 716-735. [CrossRef]

- Macnamara, J. Challenging post-communication: Beyond focus on a ‘few bad apples’ to multi-level public communication reform. Communication Research and Practice. 2021, 7, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Han, C. A survey for the application of blockchain technology in the media. Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications. 2021, 14, 3143-3165. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A.; Awan, T.M.; Paracha, O.S. The fake news effect: What does it mean for consumer behavioral intentions towards brands? Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society. 2022, 20, 291-307. [CrossRef]

- Miletskiy, V.P.; Cherezov, D.N.; Strogetskaya, E.V. Transformations of professional political communications in the digital society (by the example of the fake news communication strategy). In Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Communication Strategies in Digital Society Seminar, 121-124., ComSDS 2019. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sela, A.; Milo, O.; Kagan, E.; Ben-Gal, I. Improving information spread by spreading groups. Online Information Review. 2020, 44, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, P.D.; Dinh, T.N. Hop-based sketch for large-scale influence analysis. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, N.; Tsugawa, S. Effects of truss structure of social network on information diffusion among twitter users. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Visentin, M.; Pizzi, G.; Pichierri, M. Fake news, real problems for brands: The impact of content truthfulness and source credibility on consumers’ behavioral intentions toward the advertised brands. Journal of Interactive Marketing. 2019, 45, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanian, E.; Esfidani, M.R. It is probably fake but let us share it! role of analytical thinking, overclaiming and social approval in sharing fake news. Journal of Creative Communications. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medya, S.; Silva, A.; Singh, A. Approximate algorithms for data-driven influence limitation. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. 2022, 34, 2641–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wagner, A.L. ; Zheng X, -; Xie J, -, Boulton, M.L., Chen K, -, Eds.; Lu, Y. Hepatitis E vaccine in china: Public health professional perspectives on vaccine promotion and strategies for control. Vaccine. 2019, 37, 6566-6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.; Chen, C.; Tsai, H.; Chuang, Y. Social media privacy management strategies: A SEM analysis of user privacy behaviors. Computer Communications. 2021, 174, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Arora, A. Continuous attention mechanism embedded (CAME) bi-directional long short-term memory model for fake news detection. International Journal of Ambient Computing and Intelligence. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Y.L.; Grimaldi, D.; Garcia, S.; Ordoez, J.; Carrasco-Farre, C.; Aristizabal, A.A. Artificial intelligence model to predict the virality of press articles. Paper presented at the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. 2022, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschen, J. Investigating the emotional appeal of fake news using artificial intelligence and human contributions. Journal of Product and Brand Management. 2020, 29, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poongodi, T.; Sujatha, R.; Sumathi, D.; Suresh, P.; Balamurugan, B. Blockchain in social networking. Cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology applications. 2020, pp. 55-76. [CrossRef]

- Kitts, B.; McCoy, N.; Van Den Berg, M. The future of online advertising: Thoughts on emerging issues in privacy, information bubbles, and disinformation. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Technology and Society, Proceedings, 2019-November. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, F.; Trajcevski, G.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, F. Information cascades modeling via deep multi-task learning. In Paper presented at the SIGIR 2019 - Proceedings of the 42nd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 2019; 885-888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, X.; Wu, X. Evolutionary computation in social propagation over complex networks: A survey. International Journal of Automation and Computing. 2021, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakulapati, V.; Mahender Reddy, S. Multimodal detection of COVID-19 fake news and public behavior Analysis—Machine learning prospective. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Arora, B. A review of fake news detection using machine learning techniques. In 2021 Second International Conference on Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC). 2021, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Qasim, R.; Bangyal, W.H.; Alqarni, M.A.; Ali Almazroi, A. A fine-tuned BERT-based transfer learning approach for text classification. Journal of Healthcare Engineering. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajesh, K.; Kumar, A.; Kadu, R. Fraudulent news detection using machine learning approaches. Paper presented at the 2019 Global Conference for Advancement in Technology, GCAT 2019. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, K.; Trajcevski, G.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, F. Information diffusion prediction via recurrent cascades convolution. Paper presented at the Proceedings - International Conference on Data Engineering, 770-781., 2019-April. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.K.; Srivastava, R.; Choudhury, T.; Yadav, A.K. Computational intelligence in web mining. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bankole, O.; Reyneke, M. The Effect of Fake News on the Relationship between Brand Equity and Consumer Responses to Premium Brands: An Abstract. In Marketing Opportunities and Challenges in a Changing Global Marketplace: Proceedings of the 2019 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference.; pp. 2020461–462. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, K.; Srinivasan, V.; Zhang, X. Battling the internet water army: Detection of hidden paid posters. In Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, 116-120., ASONAM 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fârte, G. , & Obadã, D. The effects of fake news on consumers’ brand trust: An exploratory study in the food security context. Romanian Journal of Communication and Public Relations. 2021, 23, 47-61. [CrossRef]

- Bhansali, R.; Schaposnik, L.P. A trust model for spreading gossip in social networks: A multi-type bootstrap percolation model. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2020, 476. [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Fleischmann, K.R.; Koltai, K.S. Understanding online trust and information behavior using demographics and human values. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, F.; D’Arco, M.; Marino, V. Fight against corona: Exploring consumer-brand relationship via twitter textual analysis. Paper presented at the Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. 2021, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, D.K.; Meel, P.; Yadav, A.; Singh, K. A framework of fake news detection on web platform using ConvNet. Social Network Analysis and Mining. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hil, A.M.; Al-Wesabi, F.N.; Alsolai, H.; Ali OA, O.; Nemri, N.; Hamza, M.A.; Rizwanullah, M. Cryptonight mining algorithm with yac consensus for social media marketing using blockchain. Computers, Materials and Continua. 2022, 71, 3921-3936. [CrossRef]

- Cabonero, D.A.; Tindaan, C.B.; Attaban, B.H.; Manat, D.A. The effectiveness, reasons and problems in current awareness services in an academic library towards crafting an action plan. Library Philosophy and Practice. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boler, M.; Trigiani, A.; Gharib, H. Media education: History, frameworks, debates and challenges. International Encyclopedia of Education: Fourth edition. 2022, pp. 301-312. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Mustafaraj, E. How dependable are “first impressions” to distinguish between real and fake news websites? Paper presented at the HT 2019 - Proceedings of the 30th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media. 2019; 201-210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazari, S. Investigation of generational differences in advertising behaviour and fake news perception among Facebook users. International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising. 2022, 17(1-2), 20-47. [CrossRef]

- Khan, E.A.; Chowdhury MM, H.; Hossain, M.A.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Giannakis, M.; Dwivedi, Y. Impact of fake news on firm performance during COVID-19: An assessment of moderated serial mediation using PLS-SEM. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack Rotfeld, H. And a comedian shall show journalists the way. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2005, 22, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinil, Y. The anatomy of the virus-marketing campaign of book titled “A világháló metaforái”. [A világháló metaforái kötet vírusmarketing kampányának anatómiája] Informacios Tarsadalom. 2013, (1), 87-97.

- Kabha, R.; Kamel, A.M.; Elbahi, M.; Hafiz AM, D.; Dafri, W. Impact of fake news and myths related to covid-19. Journal of Content, Community and Communication. 2020, 12, 270-279. [CrossRef]

- Gass, R.H.; Seiter, J.S. Persuasion: Social influence and compliance gaining, seventh edition. Persuasion: Social influence and compliance gaining, seventh edition. 2022, pp. 1-474. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Qi, X.; Zhang, K.; Trajcevski, G.; Zhong, T. MetaGeo: A general framework for social user geolocation identification with few-shot learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, G.; Malliaros, F.D. Influence learning and maximization. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, L.; Luo, X.; Wang, C.; Sui, Y. Demystifying the underground ecosystem of account registration bots. In Paper presented at the ESEC/FSE 2022 - Proceedings of the 30th ACM Joint Meeting European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering. 2022; 897-909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, G.; Abouei Mehrizi, M. Mitigating negative influence diffusion is hard. Paper presented at the International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 332-341., Proceedings. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Rau, P.P. Deep learning model for humor recognition of different cultures. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sample, C.; Jensen, M.J.; Scott, K.; McAlaney, J.; Fitchpatrick, S.; Brockinton, A.; Ormrod, A. Interdisciplinary lessons learned while researching fake news. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotacallapa, M.; Berton, L.; Ferreira, L.N.; Quiles, M.G.; Zhao, L.; MacAu EE, N.; Vega-Oliveros, D.A. Measuring the engagement level in encrypted group conversations by using temporal networks. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Shahzad, K.; Shabbir, O.; Iqbal, A. Developing a framework for fake news diffusion control (FNDC) on digital media (DM): A systematic review 2010–2022. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, M. The ethics of psychometrics in social media: A Rawlsian approach. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. 2018, 1722–1730. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Hakak, S.; Deepa, N.; Prabadevi, B.; Dev, K.; Trelova, S. Detecting COVID-19-related fake news using feature extraction. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisker, Z.L. The effect of fake news in marketing halal food: A moderating role of religiosity. Journal of Islamic Marketing. 2020, 12, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peco-Torres, F.; Polo-Peña, A.I.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M. Tourists’ information literacy self-efficacy: Its role in their adaptation to the “new normal” in the hotel context. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2021, 33, 4526–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Naval, V. ; Igartua J, -; Arcila-Calderón, C.; González-Vázquez, A.; Blanco-Herrero, D. Ibero-American research on political communication from framing theory (2015-2019). [la investigación iberoamericana sobre comunicación política desde la teoría del encuadre (2015-2019)] Prisma Social. 2022, 39, 124-155.

- Gringarten, H.; Fernández-Calienes, R. Ethical branding and marketing: Cases and lessons. Ethical branding and marketing: Cases and lessons. 2019, pp. 1-195. [CrossRef]

- Piqueira JR, C.; Zilbovicius, M.; Batistela, C.M. Daley–Kendal models in fake-news scenario. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 2020, 548. [CrossRef]

- Bonsu, S. Deceptive Advertising: A Corporate Social Responsibility Perspective. International Journal of Health and Economic Development. 2020, 6, 1-15. https://gsmi-ijgb.com/wp-content/uploads/IJHED-V6-N2-P01-Samuel-Bonsu-Deceptive-Advertising.

- The Lancet Oncology. Oncology, “fake” news, and legal liability. The Lancet Oncology. 2018, 19, 1135. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, P.; Arakpogun, E.O.; Vu, M.C.; Olan, F.; Djafarova, E. Can you be mindful? the effectiveness of mindfulness-driven interventions in enhancing the digital resilience to fake news on COVID-19. Information Systems Frontier. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Toukoumidis, A.; Lagares-Díez, N.; Barredo-Ibáñez, D. Accountability journalism during the emergence of COVID-19: Evaluation of transparency in official fact-checking platforms. 2021. [CrossRef]

| Fase | Step | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration | Step 1 | Setting up the research problem. |

| Step 2 | The process of looking for relevant literature. | |

| Step 3 | Analyses of the chosen studies that are critical. | |

| Step 4 | Combining data from various sources. | |

| Interpretation | Step 5 | Presenting conclusions and suggestions. |

| Communication | Step 6 | Presenting the LRSB report. |

| Database Scopus | Screening | Publications |

|---|---|---|

| Meta-search | keyword: fake news | 7,387 |

| Inclusion Criteria | keyword: fake news, marketing | 117 |

| Screening | Published until April 2023 |

| Title | SJR | Best Quartile | H index |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Lancet Oncology | 12.27 | Q1 | 382 |

| IEEE Transactions On Neural Networks And Learning Systems | 4.22 | Q1 | 221 |

| Journal Of Business Ethics | 2.44 | Q1 | 208 |

| IEEE Transactions On Knowledge And Data Engineering | 2.43 | Q1 | 183 |

| Business Horizons | 2.38 | Q1 | 97 |

| Journal Of Business Research | 2.32 | Q1 | 217 |

| International Journal Of Contemporary Hospitality Management | 2.29 | Q1 | 100 |

| International Journal Of Physical Distribution And Logistics Management | 1.95 | Q1 | 117 |

| Journalism | 1.80 | Q1 | 69 |

| International Journal Of Advertising | 1.74 | Q1 | 67 |

| Journal Of The Association For Consumer Research | 1.46 | Q1 | 20 |

| Information Systems Frontiers | 1.43 | Q1 | 73 |

| Vaccine | 1.39 | Q1 | 191 |

| Journal Of Advertising Research | 1.33 | Q1 | 90 |

| Computer Communications | 1.30 | Q1 | 109 |

| Frontiers In Public Health | 1.30 | Q1 | 64 |

| Health Research Policy And Systems | 1.29 | Q1 | 55 |

| Journal Of Macromarketing | 1.14 | Q2 | 58 |

| Proceedings International Conference On Data Engineering | 1.14 | - / * | 148 |

| International Conference On Information And Knowledge Management Proceedings | 1.04 | - / * | 127 |

| Scientific Reports | 1.01 | Q1 | 242 |

| Journal Of Product And Brand Management | 1.00 | Q1 | 90 |

| Spanish Journal Of Marketing Esic | 0.98 | Q2 | 18 |

| IEEE Access | 0.93 | Q1 | 158 |

| Online Social Networks And Media | 0.93 | Q1 | 15 |

| Physica A Statistical Mechanics And Its Applications | 0.89 | Q1 | 170 |

| IEEE Transactions On Engineering Management | 0.88 | Q1 | 97 |

| Education For Information | 0.87 | Q1 | 20 |

| Frontiers In Psychology | 0.87 | Q1 | 133 |

| Central European Journal Of Operations Research | 0.82 | Q2 | 35 |

| International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health | 0.81 | Q1 | 139 |

| International Journal Of Automation And Computing | 0.80 | Q2 | 41 |

| Proceedings Of The Royal Society A Mathematical Physical And Engineering Sciences | 0.79 | Q1 | 137 |

| Peer To Peer Networking And Applications | 0.77 | Q2 | 36 |

| International Journal Of Communication | 0.75 | Q1 | 45 |

| Journal Of Healthcare Engineering | 0.68 | Q2 | 37 |

| Social Network Analysis And Mining | 0.68 | Q1 | 38 |

| Computers Materials And Continua | 0.67 | Q2 | 44 |

| International Journal Of Ambient Computing And Intelligence | 0.67 | Q2 | 21 |

| Journal Of Consumer Marketing | 0.65 | Q2 | 106 |

| Online Information Review | 0.63 | Q1 | 64 |

| Systems | 0.62 | Q2 | 22 |

| European Physical Journal Plus | 0.61 | Q2 | 67 |

| Communication Research And Practice | 0.58 | Q1 | 9 |

| International Journal Of Market Research | 0.57 | Q2 | 57 |

| Journal Of Islamic Marketing | 0.55 | Q2 | 43 |

| Proceedings Of The International Joint Conference On Neural Networks | 0.51 | - / * | 82 |

| Reference And User Services Quarterly | 0.49 | Q2 | 35 |

| Philosophy And Social Criticism | 0.45 | Q1 | 34 |

| Journal Of Research In Marketing And Entrepreneurship | 0.42 | Q2 | 23 |

| Journal Of Information Communication And Ethics In Society | 0.36 | Q1 | 21 |

| Journal Of Creative Communications | 0.31 | Q2 | 13 |

| Polis Russian Federation | 0.31 | Q2 | 8 |

| International Journal Of Internet Marketing And Advertising | 0.28 | Q3 | 21 |

| Prisma Social | 0.24 | Q3 | 9 |

| ACM International Conference Proceeding Series | 0.23 | - / * | 128 |

| Advances In Intelligent Systems And Computing | 0.22 | Q4 | 48 |

| Smart Innovation Systems And Technologies | 0.22 | Q3 | 27 |

| Informacijos Mokslai | 0.21 | Q3 | 2 |

| Quality Access To Success | 0.21 | Q3 | 22 |

| Tydskrif Vir Geesteswetenskappe | 0.21 | Q3 | 6 |

| Romanian Journal Of Communication And Public Relations | 0.19 | Q3 | 5 |

| Eai Springer Innovations In Communication And Computing | 0.18 | Q4 | 14 |

| Proceedings Of SPIE The International Society For Optical Engineering | 0.18 | - / * | 179 |

| Informacao E Sociedade | 0.17 | Q3 | 7 |

| Informacios Tarsadalom | 0.17 | Q3 | 5 |

| Journal Of Content Community And Communication | 0.17 | Q3 | 6 |

| Revista Brasileira De Marketing | 0.16 | Q4 | 6 |

| Airline Business | 0.10 | Q4 | 6 |

| 1st International Conference On Advances In Science Engineering And Robotics Technology 2019 Icasert 2019 | 0.00 | - / * | 2 |

| Ht 2019 Proceedings Of The 30th ACM Conference On Hypertext And Social Media | 0.00 | - / * | 5 |

| International Journal Of Interactive Multimedia And Artificial Intelligence | 0.00 | - / * | 3 |

| International Symposium On Technology And Society Proceedings | 0.00 | - / * | 15 |

| Library Philosophy And Practice | 0.00 | - / * | 24 |

| Opcion | 0.00 | - / * | 20 |

| Proceedings Of The 2013 IEEE ACM International Conference On Advances In Social Networks Analysis And Mining Asonam 2013 | 0.00 | - / * | 29 |

| Proceedings Of The 2019 IEEE Communication Strategies In Digital Society Seminar Comsds 2019 | 0.00 | - / * | 3 |

| Proceedings Of The 5th European Conference On Social Media Ecsm 2018 | 0.00 | - / * | 4 |

| Proceedings Of The Annual Hawaii International Conference On System Sciences | 0.00 | - / * | 92 |

| Proceedings Of The International Joint Conference On Autonomous Agents And Multiagent Systems Aamas | 0.00 | - / * | 55 |

| SIGIR 2019 Proceedings Of The 42nd International ACM SIGIR Conference On Research And Development In Information Retrieval | 0.00 | - / * | 23 |

| 2019 Global Conference For Advancement In Technology Gcat 2019 | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| 2022 International Conference On 4th Industrial Revolution Based Technology And Practices Icfirtp 2022 | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| 8th European Conference On Social Media Ecsm 2021 | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Attention Economy And How Media Works Simple Truths For Marketers | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Cryptocurrencies And Blockchain Technology Applications | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Data | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Developments In Marketing Science Proceedings Of The Academy Of Marketing Science | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Dynamics Of Influencer Marketing A Multidisciplinary Approach | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Dynamics Of Political Communication Media And Politics In A Digital Age | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Esec Fse 2022 Proceedings Of The 30th ACM Joint Meeting European Software Engineering Conference And Symposium On The Foundations Of Software Engineering | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Ethical Branding And Marketing Cases And Lessons | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| IEEE Open Journal Of The Computer Society | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| International Encyclopedia Of Education Fourth Edition | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Jornal Of Interactive Marketing | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Lecture Notes In Computer Science Including Subseries Lecture Notes In Artificial Intelligence And Lecture Notes In Bioinformatics | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Persuasion Social Influence And Compliance Gaining Seventh Edition | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Proceedings 2020 International Conference On Computational Science And Computational Intelligence Csci 2020 | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Proceedings 2022 IEEE 9th International Conference On Cyber Security And Cloud Computing And 2022 IEEE 8th International Conference On Edge Computing And Scalable Cloud Cscloud Edgecom 2022 | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Proceedings Of 2020 International Conference On Information Management And Technology Icimtech 2020 | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Psychology Of Fake News Accepting Sharing And Correcting Misinformation | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Springer Proceedings In Business And Economics | - / * | - / * | - / * |

| Sustainability Switzerland | - / * | - / * | - / * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).