1. Introduction

The importance of forests in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is widely recognized [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, recent literature suggests that forest education is not meeting the rapidly changing demands of the labor market, and the significance of forests and forest-related professions is often undervalued [

5,

6].To ensure that forests make a maximum contribution to the SDGs, a workforce proficient in forestry and related disciplines, as well as widespread public knowledge of forest-related issues based on broad ranges of disciplines and knowledge systems, is essential [

7].

Forest education plays a vital role in developing the necessary knowledge, skills, and values for sustainable forest management and achieving environmental, social, and economic goals at various levels [

6,

8,

9,

10]. However, scholarly sources highlight shortcomings in forest-related education, including inadequacy, outdatedness, and insufficiency, leading to limited awareness and understanding of forests and poorly equipped forest graduates who are ill-prepared for changing workplace demands [

11]. Challenges persist globally, such as low student enrolment in forest education programs and limited integration of forest-related subjects in curricula [

12].

The forest-based sector has experienced changes in recent years due to evolving societal demands, leading to new trends in forest education globally [

13,

14]. These changes are reflected in the labor market and the expectations of students for more diverse experiences and skills. The need for real-life solutions to problems such as climate change calls for holistic and cross-sectoral approaches, which have led to changes in university curricula towards more multidisciplinary programs. However, despite an overall increase in the number of forestry graduates and advancements towards gender parity, forest education has been insufficiently addressed in existing international efforts and collaborative efforts between leading institutions started to emerge. Forest education has been missing from the global forest policy agenda for nearly 20 years [

15]. However, there has been renewed interest in forest education, as reflected in increased activities of research organizations and NGOs, and its inclusion on the agenda of the 14th session of the United Nations Forum on Forests [

16,

17]. IUFRO and IFSA Joint Task Force on Forest Education as a collaborative project aims to bring together NGOs, researchers, and students to shape the future of forest education, strengthen forest education and highlight ways to make the sector attractive to young people [

18]. This signals a growing realization that forest education can be part of the solution reducing deforestation and forest degradation, protecting ecosystems, enhancing livelihoods and human health, conserving biodiversity, and mitigating and adapting to climate change [

11,

19]. Strengthening forest education is essential for sustainable forest management and achieving global development goals [

12].

Forest education must adapt to the numerous challenges facing the forest sector, which includes changes in societal expectations regarding forest goods and services, alterations in employment trends, and a lack of interest in the sector [

20]. Furthermore, the ageing workforce in many countries and outdated curriculums must be addressed. Urgently, forest education needs to be revitalized and expanded, with new opportunities emerging from modern digital information and communication technologies and green economy jobs. Education systems must also integrate indigenous and traditional forest-related knowledge to manage and safeguard natural resources [

11]. The Sustainable Development Goal 4, Quality Education, underlines the need for improved education on sustainable development. Without a resurgence in forest education, it will be difficult to achieve sustainable forest management and recognize the full value of forest goods and services. Additionally, without robust and suitable forest education, it is unlikely that forests and trees will fulfil their potential contributions to global development goals, including the SDGs, the targets of the UNFCCC, the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework of the CBD, the United Nations Strategic Plan for Forests, and other global goals.

Considering the rapid pace of climate change and the threat of crossing planetary limits, the upcoming decade is crucial for effective management of natural resources and environmental governance [

21,

22]. The issue of deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and increasing social disparities only heighten the urgency. Creating a space for scenario planning and exploring various paths is a vital tool in shaping environmental policy [

23]. This study utilized a role-playing game focusing on the changes in central African forests to teach about drivers of deforestation and other global challenges [

24].

Role-playing games, from haptic tabletop games, over computer-supported RPGs, to fully computerized Agent-Based Models, have a rich history of use in research and practice. These types of games have been employed and refined for over four decades in the fields of adaptive environmental management science and participatory action research [

25,

26,

27]. Role-playing games have been proven to be effective tools for facilitating decentralized problem-solving and promoting a bottom-up approach that empowers participants to actively engage with complexity and uncertainty—in contrast, top-down prescriptive approaches that rely on expert-driven solutions have been shown to have limited effectiveness in managing complexity and uncertainty [

28]. Our assumption is that by providing students with an immersive experience of “being inside the system” of study, role-playing games offer a powerful alternative to traditional classroom learning methods.

2. Materials and Methods

The game session discussed in this paper took place with 6 Students from the “International Management of Forest Industries” Master at the Berner University of Applied Science in January 2023 over the course of one week (5 continuous days, with 4 to 6 hours gameplay and debriefing per day). It was facilitated by CG and PW. As the course was conducted online with students located off campus, we relied on an online whiteboard (Mural) to aid our discussions (which took place on Zoom) and to monitor our progress. Additionally, we utilized a role-playing game as our primary method for engaging in-depth discussions on forest change and deforestation drivers. Although traditionally played in person, we created a Mural-compatible beta version of the game.

MineSet is a simulation model game that explores the impact of forestry activities on the tropical forest landscapes in Central Africa. Players take on the roles of CEOs of logging and mining companies, and they must interact with markets, government, and NGOs to design strategies and shape the environment, economy, and society with their actions. The game considers economic and financial constraints, demographic development, governance, transparency, technical innovation, and cultural differences to reflect the major drivers of land use change in the tropics. The objective is for players to balance development and conservation demands of the system. It has been used for academic research and workshops with a focus on forest management, logging, and mining activities [

24].

During a game of MineSet, players gain basic understanding of the intricate dynamics involved in land use change within the tropical forests of Central Africa. Through a step-by-step process, players are exposed to the complexities of the system, allowing them to deepen their knowledge and insight into the environmental, social, and economic factors in a playful manner. The game has loosely defined temporal and geographical scales. One hexagon is said to represent 500 km2 and one turn 10 years, but none of these values have an impact on the flow of the game. They just help participants enter the game by providing them with familiar elements. To help players learn the rules by playing, the story is set to begin in the 1960s with high-density forests on either side of a single road connecting two urban centers and minimal regulations in place. Farmers and hunter-gatherers live along this road—representing the resettlement imposed by colonial powers in the late XIX century to early XX. Each player is responsible for managing a logging or mining company with the same starting conditions. In total there are 9 concessions, which are located north and south of the already existing road connecting the east and west of the gamescape (the game landscape board). Throughout the game, players must compete to acquire logging concessions, construct roads, harvest timber (precious red wood, or common brown wood), and sell their products on the global market. Each concession in the game has unique characteristics such as resources, biodiversity, exposure, and market access, leading to a distinct situation for each player. Concessions are randomly assigned to players at the beginning of the game, which comprises multiple phases. During the initial phase, players have a brief period to strategize and discuss with others before harvesting timber from their concession and sell it to the market. The decisions made by the players affect the landscape and provide insights into the impact of their choices. In the final phase of the round, players can choose to invest in improving their creditworthiness for future rounds, or alternatively, invest in e.g., a sawmill, infrastructure, or acquire additional concessions. There are several strategies to play MineSet, depending on the goal of the player. Every strategy evolves and may change during the game session various times.

Additionally, players' strategic decisions are influenced by global events and expectations. During the 1960s and 1970s, players can prioritise road network development and schedule timber extraction, including precious red wood and common brown wood. During the 1980s, the concept of sustainability gained recognition, leading to an increasing significance of public opinions. Consequently, companies were compelled to adopt more environmentally friendly practices. As public opinion rose, credit ratings improved, resulting in greater access to loans from banks for increased investments. This allowed companies to expand their logging operations, highlighting the financial aspect of sustainability during that decade. In the 1990s, the focus shifted to environmental aspects, introducing biodiversity through an NGO promoting environmental studies and the hiring of biologists to evaluate biological diversity. Certification schemes like FSC offer access to regulated European markets or less regulated alternatives like Asian markets. The 2000s and 2010s highlight social justice, with advocacy groups playing a central role. Throughout the game, tensions escalate due to increased migration influenced by neighboring conflicts, impacting concessions and the wider landscape.

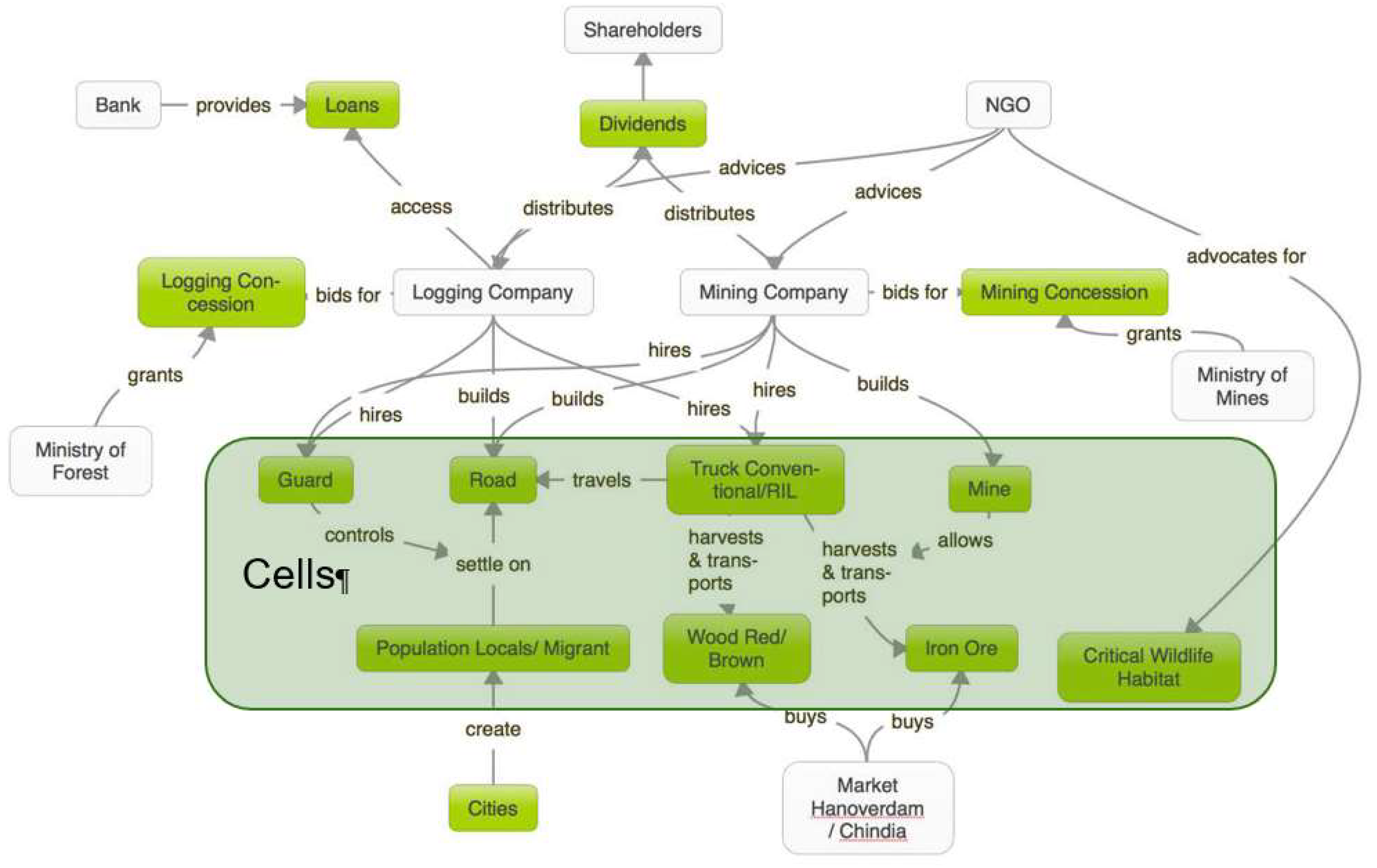

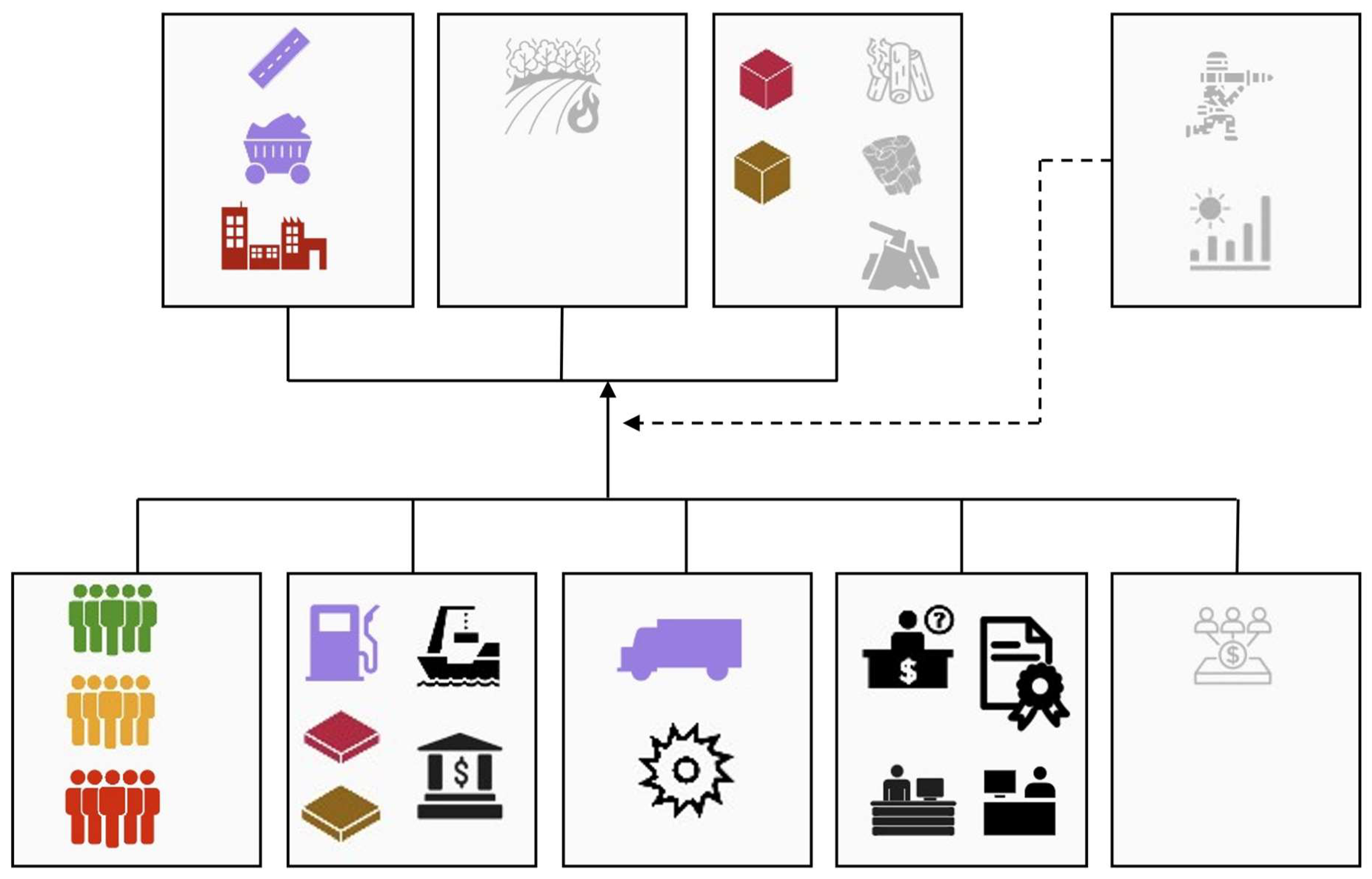

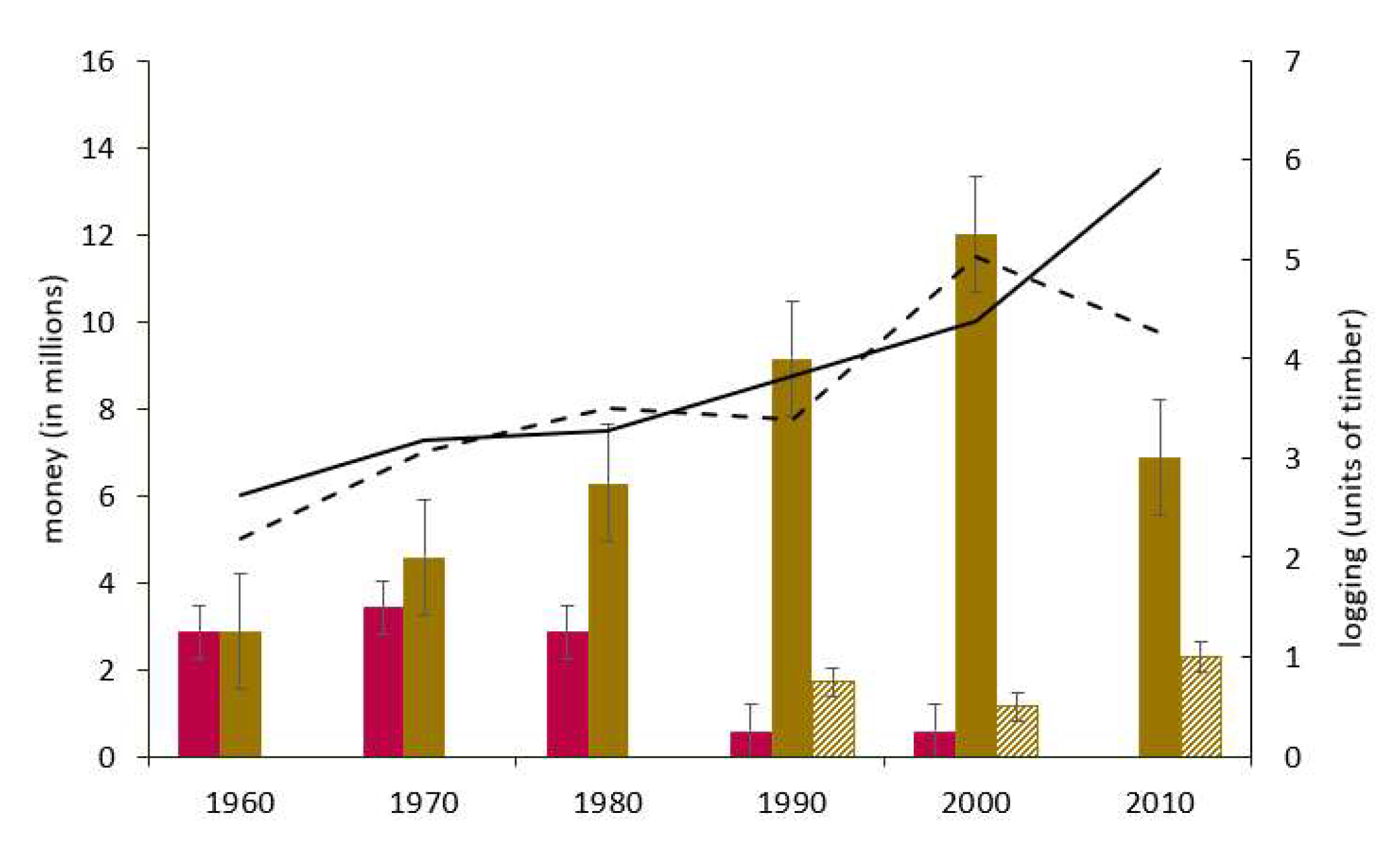

MineSet features all the major underlying drivers of land use change in the tropics, including demographics, economical and finance signals, governance and transparency, technological changes, and cultural differences (

Figure 1,

Figure 2). As the game unfolds, players discover the complexity of the system and devise new rules and strategies to balance development and conservation.

Central to the MineSet model is the process of forest growth and the interaction between ecological processes and human activities. Each cell has a value of Forest cover (F) ranging from 0 to 10, represented visually with a different color according to three broad land cover types. In addition, each cell has a Maximum Forest Cover (Fmax) also ranging from 0 to 10. F cannot exceed Fmax. Roads, local populations, and mines reduce Fmax, while logging directly reduces F without affecting Fmax. F will increase by 1 unit every turn, up to Fmax. Plantations and silvicultural practices will double the rate of forest growth. Players embark on a journey of discovery, gradually unravelling and comprehending the intricate mechanisms of the system as they progress through gameplay. With these simple rules, the MineSet model reflects the four processes of deforestation, forest degradation, forest natural growth, and restoration [

24].

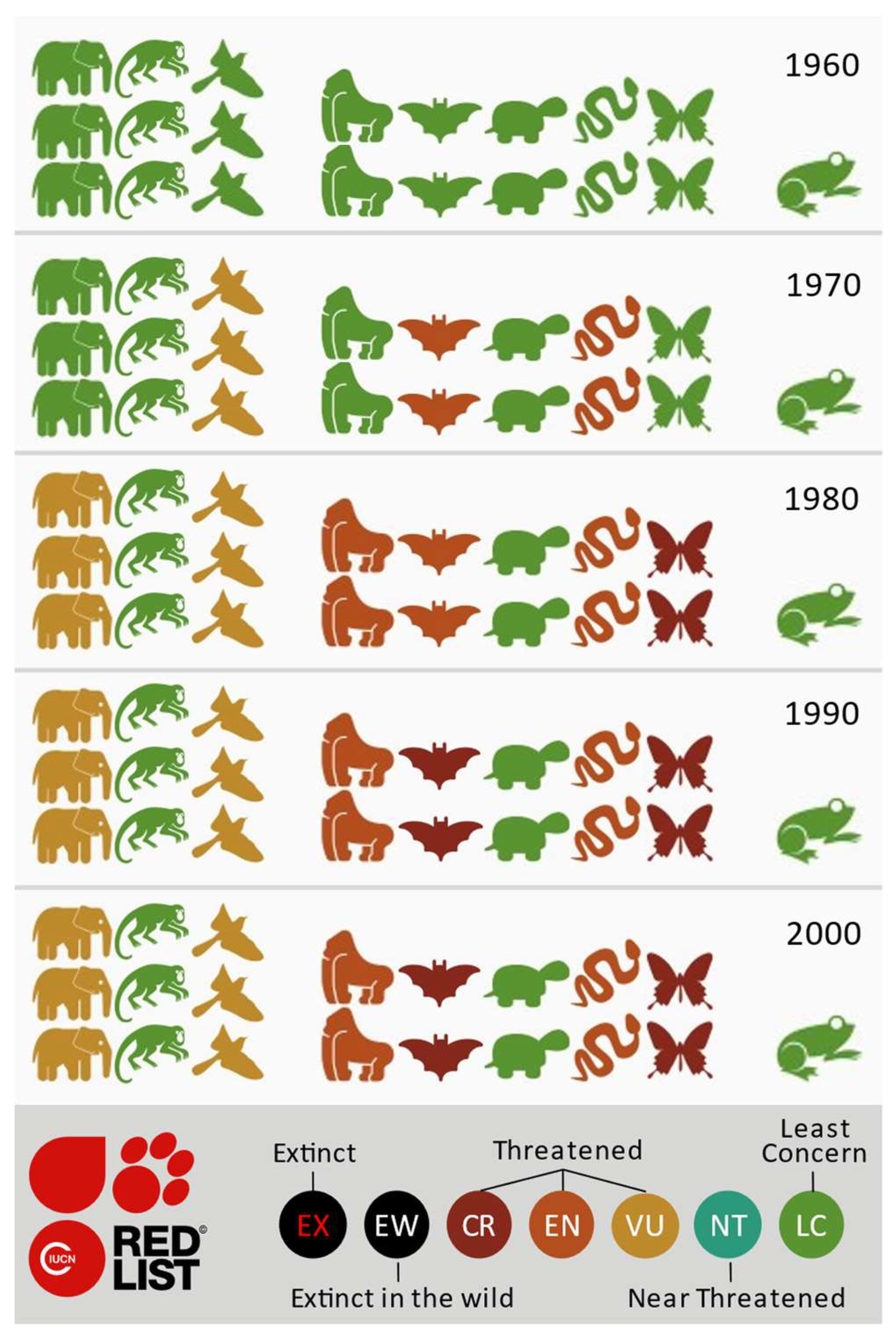

Biodiversity is explicitly taken into account in the model through the existence of endemic species represented by tokens located on specific cells. Each of these biodiversity tokens can be in three states as per IUCN Red List terminology: Least Concerned, threatened, or extinct. Based on the land cover type of the cell the species token is placed on, the token will shift from one state to the other. Transitions are reversible except for the last one, where an extinct species is permanently lost.

3. Results

The drivers of deforestation observed in the MineSet game included unsustainable logging operations and agricultural expansion represented as migrants and settlers tokens, proximity to international markets (capital-driven deforestation), and insufficient capital (poverty-driven deforestation). By playing the game, the students could gain a deeper understanding of human behaviour and agency as factors that shape the system (

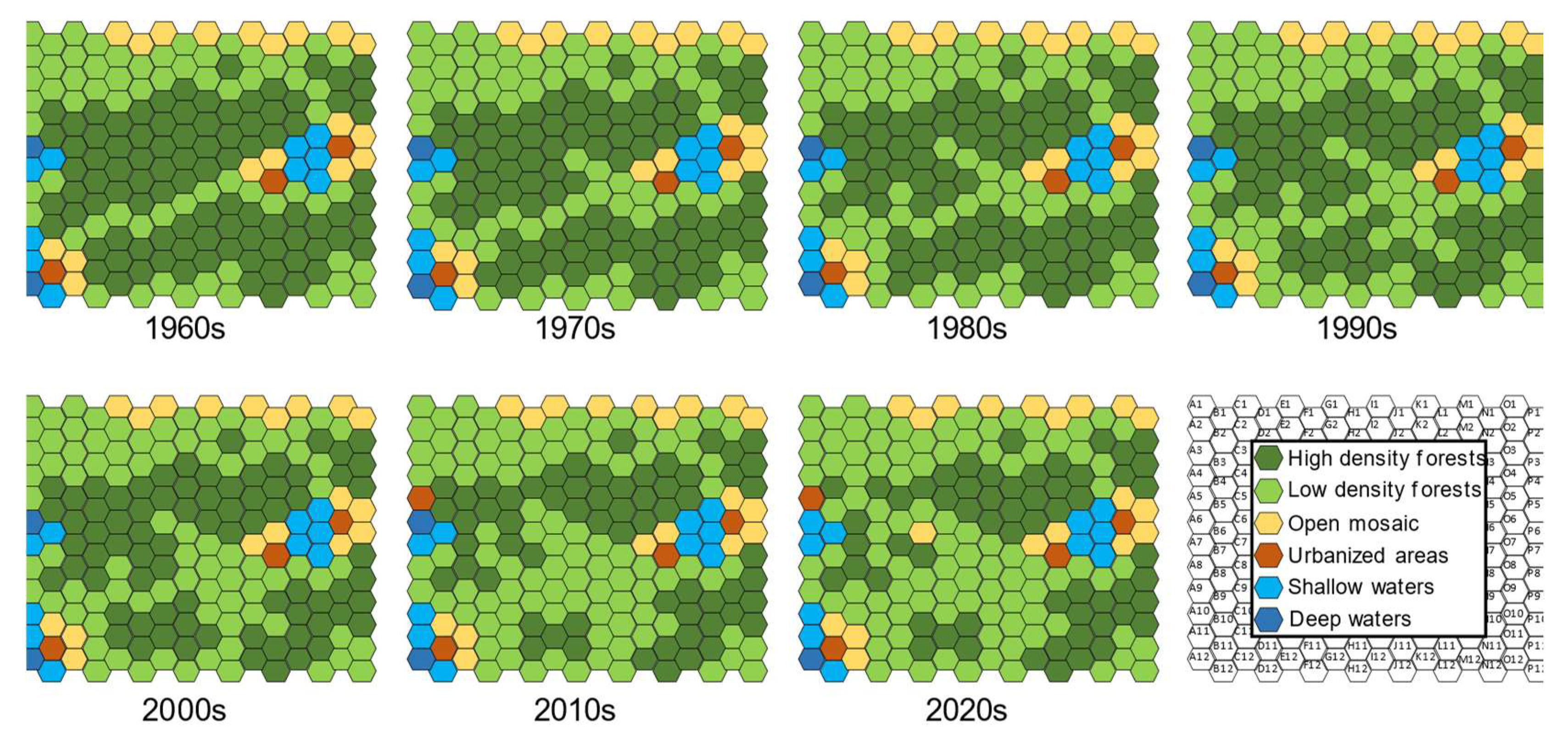

Figure 2). During the game, the participating students had the opportunity to directly observe and experience the changes in the forest landscape in Central Africa (

Figure 3).

3.1. Applied strategies for forest landscape management

The students who played MineSet made a series of critical decisions that shaped the gamescape (game landscape,

Figure 3) and social and economic outcomes. Their strategies varied from intensive logging and infrastructure construction in the 1960s to prioritizing sustainability and managing the environment in the 2010s. Each decade presented unique challenges and opportunities that required different approaches to earn money from logging while protecting the environment and satisfying stakeholders.

In the 1970s, players diversified their approaches to earning money from logging by conducting scientific assessments, inventories, and cooperating with the public and government. They expanded harvest volume and roads, sold wood to the international market and shareholders, and built only one road and bought only one truck to gain access to the European market.

The 1980s saw players move to more profitable markets that required certification such as FSC or PEFC. They intensified wood extraction by building additional roads and buying more trucks, controlling migrant groups, and only used existing infrastructure. Investing in a sawmill to sell sawn wood to Europe was also a common strategy.

In the 1990s, players started processing wood at the sawmill and selling sawn wood to the international market. They pursued certification by presenting a management plan, conservation areas, reduced harvesting (e.g., by use of reduced impact logging), and resolving problems with the local community to get an FSC certificate. Sustainable management, biodiversity inventory, and endangered species protection were also emphasized.

The 2000s saw players switch to the domestic market and harvest more red wood—where available—for revenue. They returned to the international market after fulfilling FSC certification guidelines, constructed a sawmill to resolve local community issues, and implemented sustainable harvesting overall. Some players went back to the local market with sawn wood and earned good money. Others switched to alternative markets, invested in biodiversity inventory, and thought about either following the “extract and expand”-approach or aiming at certification in case of growing external public pressure (either shareholders or credit rating system, or international press).

In the 2010s, players prioritized the sustainability factor as resources continue to be depleted, protected endangered species, and reduced infrastructure expansion. Some could not make any decisions due to the demand for certification, while others took only what was needed, managed the environment well, and sold wood to the local market.

3.2. Experiencing the consequences of the applied strategies

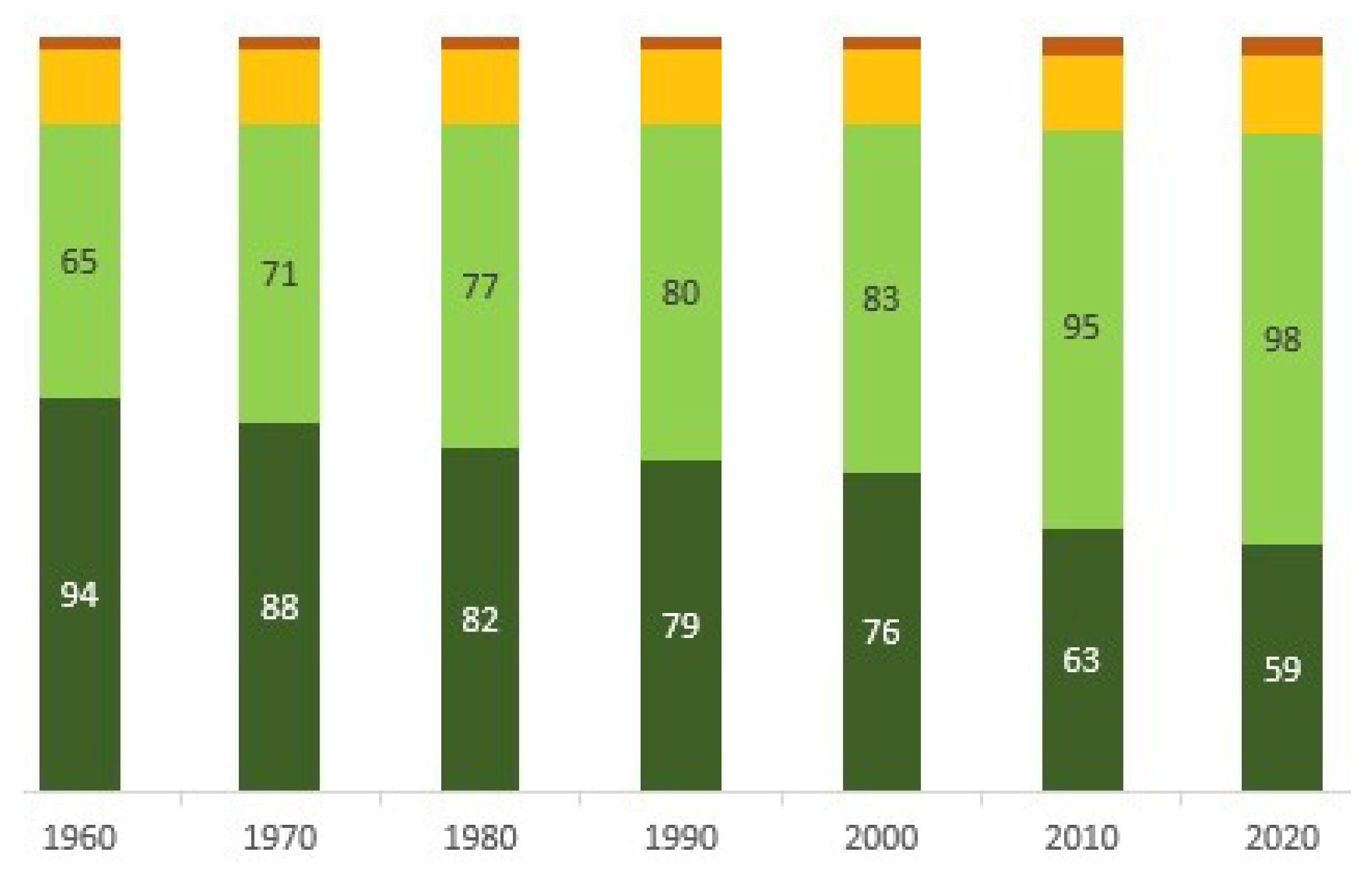

The changes directly observed included the loss of tree cover, degradation and fragmentation, which ultimately led to the replacement of primary forests by secondary forests or even fully degraded forests (

Figure 3,

Figure 4). Changes that players were able to detect indirectly or with a time delay, related to economy. Logging corporations in the game made a steady profit by selling brown and red wood (

Figure 5). However, this profit came with significant environmental consequences, such as a growing list of threatened species (

Figure 6), growing migrant population, fluctuating public opinions and unstable market prices.

During their decision-making process in the MineSet game, students experienced different drivers of deforestation and forest change. These drivers included unsustainable logging operations, road expansion, liberal granting of concessions, poor binding forestry regulation, agricultural expansion in the form of migrant settlers, and infrastructure development aimed at improving access to urban areas and markets. These drivers were primarily motivated by specific demands such as economic development, gaining access to the European or Chinese market, and growing as a company to earn more money. Some students also experienced uncontrolled logging activities with no restrictions, controls, or punishments, and no certification was in place to regulate these activities at certain times and in some of the concessions.

The MineSet game experience of the students highlights the impact of policies, certification, and public expectations on the decisions made by forest players. Certification schemes emerged in the 1990s and played a crucial role in determining market access and profitability for forest players. Complying with certification requirements was found to be challenging, as some players found it too time-consuming or ineffective. New agencies also affected forest governance and management, but player participation varied. Biodiversity commitments impacted forest conservation and restoration, but some players prioritized economic returns. Some players demonstrated social and environmental responsibility through certification, while others opted for non-certified markets. The absence of strict forest policies allowed some players to prioritize full business efficiency and even consider corrupt practices. However, players faced demands for sustainability efforts and certification, especially on the European market, leading some to seek access to alternative and less regulated or restrictive Asian markets [

31]. The students' experience highlights the complexity of forest management, where players must balance economic, social, and environmental factors while navigating changing policies and market demands.

4. Discussion

The simulation game employed in this study spans a 60-year timeframe, with each round representing a decade, starting from 1960 and extending beyond 2020. The game encompasses a wide range of topics, including sustainability, biodiversity, certification, financial crises, war, pandemics, among others. By immersing participants in gameplay, the game offers an interactive and experiential learning opportunity that allows students and practitioners to explore their own perspectives and analyze the intricate factors influencing international forest governance. Notably, a well-designed and effectively executed game session can have a profound and enduring impact on participants, evoking strong emotional responses. Throughout gameplay, individuals may experience a spectrum of emotions, such as surprise, frustration, triumph, anger, and joy, which contribute to a heightened level of engagement and deeper understanding. Moreover, the topics and discussions that emerge during the game continue to resonate with participants even after the session concludes, thereby enhancing the overall learning experience [

32].

4.1. Transformative learning

In the last decade, there has been a growing interest among educational researchers in transformative experiences. Kevin Pugh [

33] has recommended that science classrooms should be reoriented to incorporate such experiences, while transformative learning theory and social justice education have emphasized the significance of creating "disorienting dilemmas" to transform students’ worldviews [

34]. In the context of this discussion, during their gameplay of MineSet, the students were presented with a few critical aspects that were surprising to them. Firstly, they were taken aback by how their collective decisions had a negative impact on the forests, which helped them comprehend that managing tropical forest landscapes is a multifaceted task that involves difficult choices. Secondly, the students realized that unexpected events and feedback could significantly influence the system and outcomes. Lastly, they came to understand that stakeholders may have different interests and goals, which can result in either cooperation or conflicts. These surprising elements of the game underscore the value of games like MineSet, which provide a realistic and immersive experience that can prepare students for real-world scenarios in forestry and environmental contexts.

Transformative learning is a process that involves critically evaluating one's existing assumptions and beliefs to bring about a profound shift in worldview [

35]. This transformative process is facilitated by being exposed to alternative viewpoints and engaging in conscious reflection. In the context of higher education, transdisciplinary approaches have the potential to foster transformative learning by exposing students to diverse knowledge and perspectives. These approaches emphasize reflexivity, encouraging students to unpack their values, norms, and worldviews as they grapple with sustainability issues. However, there is an ongoing discussion on how to effectively design transdisciplinary learning experiences that optimize transformative learning. Scholars such as Mezirow [

36], Fisher and McAdams [

37], and Leal Filho et al. [

38] have contributed to this discourse. In our observations, we have found that strategy games have proven to be particularly effective in promoting transformative learning within transdisciplinary contexts.

Optimal learning occurs when individuals actively engage in learning practices that are directly relevant to their specific situations. These practices are primarily influenced by unconscious processes in the brain, by our mental models, shaped by previous learning experiences and motivational states [

39]. In the realm of higher education, achieving transformative learning often requires the participation of stakeholders [

40,

41]. However, incorporating real stakeholders into the classroom is hindered by practical challenges, including scheduling conflicts, time constraints, and other commitments. While virtual platforms provide an alternative, organizing stakeholder engagement remains a complex endeavor. To overcome these obstacles and emulate the inclusion of stakeholders, the integration of role-play games emerges as an elegant solution.

By assuming different roles, students actively participate in the game and gain first-hand experience of stakeholder perspectives, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of diverse viewpoints. This immersive approach enables them to navigate the complexities of decision-making within forest landscapes. One student emphasized the value of such games, stating, “[games]effectively demonstrate the long-term impacts of our decisions within a condensed time frame.” Throughout the gameplay, students interacted with a range of actors, including big logging companies, concession holders, Indigenous communities, government officials, and non-governmental organizations, other land users and nature protection groups. These interactions provided opportunities to exchange perspectives on deforestation and gain a comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics at play. Importantly, the game also facilitated timely reassessment and adjustment of strategies, underscoring the intricate web of interactions among stakeholders involved in specific issues.

To evaluate the effectiveness and scope of substituting actual stakeholder involvement with role-play games, further scientific research is essential. Nonetheless, the incorporation of role-play games in educational settings signifies a significant advancement towards fostering transformative teaching practices. By immersing students in dynamic scenarios and encouraging active engagement, these games promote critical thinking, empathy, and a holistic understanding of real-world challenges [

42]. Ultimately, the inclusion of role-play games offers a promising avenue to bridge the gap between theory and practice, equipping students with the skills and perspectives necessary to navigate complex issues and contribute to meaningful change in the world.

Through the game, students were introduced to the drivers of deforestation and gained a new appreciation for the impact that individual decisions can have on the collective outcome. They learned how different actors in the system have different incentives and interests, and how these can lead to trade-offs between environmental, economic, and social objectives. By exploring these drivers and trade-offs through the game, students gained a deeper understanding of the challenges associated with managing forest landscapes.

Trade-offs emerged as a critical concept in the MineSet game. Students learned that managing forest landscapes involves difficult choices and that there are no easy solutions. They gained insights into the interplay between environmental, social, and economic objectives and saw how these can sometimes conflict with each other. By experiencing these trade-offs first-hand, students were better equipped to understand the complexity of forest management and to appreciate the importance of balancing competing interests.

Constructivist teaching is centered on the belief that learners in general actively construct knowledge rather than passively receive it [

43]. It promotes critical thinking skills, nurtures self-motivated and independent learners, and recognizes the dynamic interplay between internal factors and external conditions [

44]. This approach emphasizes five key characteristics: active, constructive, self-directed, social, and situational learning processes [

42]. Knowledge is constructed within various contexts and through social interactions. Learners co-create knowledge in a self-organized manner, benefiting from complex and authentic learning environments that encourage experiential learning, multiple perspectives, social collaboration, and instructional support [

45]. Gaming simulation aligns well with constructivist theories, challenging traditional notions of knowledge and supporting diverse perspectives [

42]. It embraces the idea that there is no singular best approach to learning, echoing the principles of constructivism and systems thinking, which encourage exploration of complexity and reject simplistic solutions in understanding human behavior.

4.2. When teachers become facilitators

The impact of teachers’ actions in the classroom on student learning is widely acknowledged. However, there is a lack of data regarding which teaching practices effectively support learning in inclusive classrooms, particularly data derived from direct observations of teachers [

46]. When integrating gaming into the classroom, the teacher's role shifts to that of a facilitator or game master, extending beyond traditional curriculum instruction. During gameplay, various emotions may arise, demanding immediate attention [

47]. The teacher must possess facilitation skills to adeptly manage these strong emotions stemming from both successful and frustrating gameplay. Emotions experienced by participants can span from joy and happiness to frustration, sadness, or even anger, influenced by their decisions and outcomes within the game. The teacher or facilitator must assess the situation and create opportunities for meaningful discussions, often accomplished through debriefing sessions that are integral to the learning process [

32]. While debriefings usually follow a structured format [

48], in the classroom, they can encompass specific topics or themes. Typically, a debriefing consists of several steps, inter alia: (1) acknowledging explicit emotions and inquiring about participants' feelings, (2) discussing the events that unfolded during the game, and (3) drawing comparisons between the game and real-world situations, and (4) what could be changed, i.e., the “what if” discussion. To ensure fruitful outcomes from the game and ensuing discussions, skilled facilitation becomes imperative. While the game sessions can be enjoyable, the process of confronting one's cognitive limitations and challenging incorrect assumptions may lead to frustration and discomfort [

49]. Effective facilitation thus plays a crucial role in transforming these challenging personal experiences into valuable opportunities for learning and self-reflection [

23]. This approach allows students to co-learn or develop soft competencies which have been identified as key for workplace success. The soft skills development has high importance in our class and includes leadership and management, human relations, and communication.

4.2. Limitations

The original MineSet game is a physical, haptic tabletop game, which has the advantage of facilitating interplayer exchanges and emotional engagement. However, for this particular instance of the game, the students played an online version. While the online version allowed for remote play and accessibility, it lacked the tactile and emotional aspects of the physical game. The students offered valuable feedback on how the MineSet game could be improved for educational purposes. To enhance the overall learning experience, they suggested two key changes. Firstly, the students recommended the development of a fully standardised online version of the game, which would be optimal for remote play. While the beta-run of the game on Mural was generally successful, waiting times increased as the game master had to keep track of everything, and instructions for online play took some time for everyone to understand. A standardised online version would also reduce the need for a game master and allow students to proceed through the game at their own pace. Secondly, the students suggested providing an instruction sheet before the start of the game to provide a clear impression of the game mechanics. This would reduce the time needed for the game master to explain the game, increasing the efficiency of the game, and improving the overall learning experience. The students also highlighted the importance of improving the accessibility and connectivity of the game, which would allow more participants to engage with the game remotely. These suggestions would help to maximise the benefits of the game as an educational tool, making it easier for teachers to integrate it into their curriculum and helping students to better understand the complex dynamics of deforestation.

4.4. Using games beyond the classroom

The students provided insights on the usefulness of games like MineSet beyond teaching. As future managers and decision-makers in the fields of forestry and other environmental contexts, they recognized the importance of such games in preparing them for real-world scenarios. While games like MineSet provide an alternative to lecture-based learning, the students believed that bringing real actors such as politicians, business people, or locals to the table could further support real action and policy. Moreover, through the possible role swaps the game promotes empathy, which could help overcome opposition in politics or culture, leading to more informed decision-making.

MineSet can be a useful tool for exploring the transitions and future of tropical forest landscapes due to its ability to simulate the direct and indirect drivers of forest change, as well as mimic forest degradation and recovery. What makes the game particularly valuable is that it brings agency to the table. Real people, such as students or anyone who commits their time and energy to attend a game play workshop, can enter different roles, such as big corporations with the power to make landscape-level and long-term impacts, governments, the World Bank, communities, NGOs, and more. By allowing players to step into these roles and interact with each other, the game creates a realistic and immersive experience, as in “this feels real” (see [

50]), that can help players understand the complex dynamics of tropical forest landscapes.

Ultimately, the MineSet game can help players develop a better understanding of the challenges and opportunities involved in sustainable forest management. By exploring different scenarios and outcomes, players can gain insights into how different decisions and actions can affect the landscape over time in a safe space [

28,

51]. This can be particularly useful for policymakers, as they can use the game to test different policy options and evaluate their potential impact before implementing them in real life [

23].

Education possesses the potential to effectively engage and raise awareness among diverse individuals, ranging from ordinary citizens, students to educators and high-level decision-makers. However, it is crucial to recognize that information alone is insufficient to instigate significant change [

52,

53]. While reinforced learning entails gradual shifts in behavior or improvements in performance, insight learning manifests as sudden and dramatic behavioral changes [

54]. Surprises, arising from disparities between incoming information and our established expectations formed by mental models, prompt specific behavioral responses aimed at revising these mental models to enhance our ability to anticipate future states of the world [

55]. As players engage in gameplay, they undergo emotional responses, and the impact of their decisions shapes their values and priorities. It is this transformative power of games that makes them effective tools, such as MineSet, not only within classrooms but also in realms like policy making [

23]. While we have presented an example related to forests, the application of such games can extend to any complex subject within the domains of environmental management and governance.

4.5. Towards sustainable forestry: Critical thinking and social innovations

Strategy games in forest education provide an innovative tool for fostering sustainability through critical thinking and transdisciplinary understanding. By engaging with real-world scenarios and using creative problem-solving skills, students develop a nuanced understanding of complex sustainability challenges and the interconnections between stakeholders. This approach can promote motivation and collaboration, preparing the next generation of leaders in the sustainability field, yet fostering changes on the ground c.f. social innovations. By promoting collaboration and creativity among students, working together to devise effective solutions for sustainability challenges, students can develop a sense of ownership and agency over these issues [

56]. This approach can inspire new ideas and approaches to sustainability, leading to social innovations that benefit communities and the society as a whole. Moreover, by engaging with a range of disciplines and stakeholders, students can develop a more comprehensive understanding of sustainability challenges and the need for transdisciplinary solutions. This approach can help break down silos and promote collaboration across sectors and fields and can be a valuable tool for fostering social innovations [

57,

58] to address the complex sustainability challenges in forestry.

After playing the MineSet game, students summarised that games like MineSet can be useful for educating and empowering local communities to overcome problems related to sustainable forestry. They also believe that governmental and non-governmental decision-makers could benefit from the game ability to show different perspectives on the same issue. MineSet includes multiple actors and stakeholders, making it suitable for teaching international forestry classes and providing a better understanding of their behaviour towards sustainable forestry. The game can prevent conflicts among stakeholders by guiding participants to think and discern without blaming others, thus helping decision-makers create informed policies.

5. Conclusions

The integration of role-playing and strategy games, such as MineSet, shows promise for enhancing forest education in classrooms. In the context of evolving global conditions and challenges in the forestry sector, innovation in the classroom becomes increasingly important. Forest education plays a crucial role in sustainable forest management and meeting societal demands on forest resources. However, concerns persist regarding the insufficiency and outdated nature of current forest education. To address these challenges, it is essential to attract talented students to forest programs, provide ongoing learning opportunities, and broaden access to educational materials through online platforms. The MineSet game serves as a valuable tool by offering immersive experiences that provide insights into complex issues like deforestation. By assuming different stakeholder roles and emphasising trade-offs in forest management, the game nurtures critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving skills. Additionally, the MineSet game is instrumental in teaching international forestry by illustrating stakeholder behaviour and the challenges associated with sustainable forestry. Its play-based design facilitates unbiased thinking and fosters equitable decision-making. Incorporating such innovative tools into forest education enhances the training of future forest managers and policymakers, optimising the contributions of forests to sustainable development. Continued exploration and implementation of these educational games are crucial for overcoming limitations in forest education, increasing awareness and understanding of forests, and related professions. Embracing innovative approaches in the classroom equips students to tackle complex forest issues, paving the way for effective and sustainable forest management practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.O.W., M.M. and C.A.G.; methodology, C.A.G. and P.O.W.; validation, E.R., L.V.C., R.L., J.R., T.R., M.Z. and O.S. formal analysis, all; data curation, P.O.W., R.L., M.Z. O.S., C.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.O.W., M.M., E.R., J.R. and T.R.; writing—review and editing, all; visualization, P.O.W., M.Z., O.S. and C.A.G.; supervision, C.A.G. and P.O.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

C.A.G. and P.O.W. disclose their shareholding in LEAF Inspiring Change (

https://leafic.ch/), a Swiss spin-off of ETH. LEAF provides consultancy services, including the utilization of strategy games, to clients in both the public and private sectors.

References

- Bloomfield, G.; Bucht, K.; Martínez-Hernández, J.C.; Ramírez-Soto, A.F.; Sheseña-Hernández, I.; Lucio-Palacio, C.R.; Ruelas Inzunza, E. Capacity building to advance the United Nations sustainable development goals: An overview of tools and approaches related to sustainable land management. J. Sustain. For. 2018, 37, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, F.; Busch, J. Forests and SDGs: Taking a Second Look. 2017. https://www.wri.org/insights/forests-and-sdgs-taking-second-look.

- Agarwal, B. Gender equality, food security and the sustainable development goals. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 34, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, L.; Drazen, E.; Johnson, W.R.; Bukoski, J.J. The future of tropical forests under the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Journal of Sustainable Forestry. 2018, 37, 221–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.L.; Ward, D. Professional education in forestry. Commonwealth Forests. 2010, 76–93. http://www.cfa-international.org/docs/Commonwealth%20Forests%202010/cfa_layout_web_chapter5.pdf.

- O'Hara, K.L.; Salwasser, H. Forest science education in research universities. Journal of Forestry 2015, 113, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kofinas, G.P.; Folke, C.; Abel, N.; Clark, W.C.; Olsson, P.; Smith, D.M.S.; Walker, B.; Young, O.R.; Berkes, F. Ecosystem stewardship: sustainability strategies for a rapidly changing planet. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sample, V.A.; Bixler, R.P.; McDonough, M.H.; Bullard, S.H.; Snieckus, M.M. The promise and performance of forestry education in the United States: Results of a survey of forestry employers, graduates, and educators. Journal of Forestry 2015, 113, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cristofaro, M.; Taber, A. Boosting Education for Greener Forests. SDG Knowledge Hub. Available online: https://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/guest-articles/boosting-education-for-greener-forests/.

- Bardsley, D.K.; Cedamon, E.; Paudel, N.S.; Nuberg, I. Education and sustainable forest management in the mid-hills of Nepal. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 319, 115698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Piñeros, S.; Walji, K.; Rekola, M.; Owuor, J.A.; Lehto, A.; Tutu, S.A.; Giessen, L. Innovations in forest education: Insights from the best practices global competition. Forest Policy and Economics. 2020, 118, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekola, M.; Sharik, T.L. Global assessment of forest education – Creation of a Global Forest Education Platform and Launch of a Joint Initiative under the Aegis of the Collaborative Partnership on Forests (FAO-ITTO-IUFRO project GCP/GLO/044/GER); Forestry Working Paper No. 32; FAO: Rome, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUFRO. Post-2020 Strategy. 2023. https://www.iufro.org/fileadmin/material/science/divisions/toolbox/iufro-strategy-2020-post.pdf.

- Owuor, J.A.; Giessen, L.; Prior L.C.; Cilio, D.; Bal, T.L.; Bernasconi, A.; Burns, J.; Chen, X.; Goldsmith, A. A.; Jiacheng, Z.; Kallioniemi, M.; Kastenholz, E.; Larasatie, P.; Lehikoinen, A.; Lewark, S.; Maciel Viana, C.; Montero de Oliveira, F.E.; Oberholzer, F.; Sharik, T.L.; Schwärzli, J.; Schweinle, J.; Viitanen, J.; Wästerlund, D.; Yovi, E. Y.; Winkel, G. Trends in forest-related employment and tertiary education: insights from selected key countries around the globe; European Forest Institute (EFI): 2021.

- Hamid, O.Y.; Ibrahim, A.M. Regional Assessment of Forest Education in Near East and North Africa. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Rome. 2021. https://www.fao.org/3/cb6740en/cb6740en.pdf.

- UNFF (United Nations Forum on Forests). 14th Session of the UN Forum on Forests (UNFF14). 2019. https://enb.iisd.org/events/14th-session-un-forum-forests-unff14.

- Rekola, M.; Nevgi, A.; Sandström, N. Regional Assessment of Forest Education in Europe. 2021. FAO. Rome, Italy.

- IUFRO; IFSA. Joint IUFRO-IFSA Task Force on Forest Education. 2023. https://www.iufro.org/science/task-forces/forest-education/#:~:text=The%20Joint%20IUFRO%2DIFSA%20Task,the%20future%20of%20forest%20education.

- Temu, A.B. Future forestry education: responding to expanding societal needs. World Agroforestry Centre, 2008.

- Owuor, J.A. and Rodríguez-Piñeros, S. Best practices in forest education in Europe from the global best practices competition. In: Schmidt, P., Lewark, S., and Weber, N. (Eds.), Twenty years after the Bologna declaration – Challenges for higher forestry education. 2021. SILVA Publications 17, Dresden. Pre-publication published online at https://ica-silva.eu/.

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin III, F.S.; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; Nykvist, B. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society 2009, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; Folke, C. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.A.; Savilaakso, S.; Verburg, R.W.; Stoudmann, N.; Fernbach, P.; et al. Strategy games to improve environmental policymaking. Nature Sustainability 2022, 5, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Speelman, E.N. Landscape approaches, wicked problems and role-playing games. ForDev Working Paper 01. Department of Environmental Systems Science, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich, Switzerland. 2017. [CrossRef]

- D'Aquino, P.; Le Page, C.; Bousquet, F.; Bah, A. Using self-designed role-playing games and a multi-agent system to empower a local decision-making process for land use management: The SelfCormas experiment in Senegal. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. 2003, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Barreteau, O.; Le Page, C.; D'aquino, P. Role-playing games, models and negotiation processes. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2003, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Souchère, V.; Millair, L.; Echeverria, J.; Bousquet, F.; Le Page, C.; Etienne, M. Co-constructing with stakeholders a role-playing game to initiate collective management of erosive runoff risks at the watershed scale. Environmental Modelling & Software. 2010, 25, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.A.; Vendé, J.; Konerira, N.; Kalla, J.; Nay, M.; Dray, A.; Delay, M.; Waeber, P.O.; Stoudmann, N.; Bose, A.; Le Page, C. Coffee, farmers, and trees—shifting rights accelerates changing landscapes. Forests 2020, 11, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, M.; Du Toit, D.R.; Pollard, S. ARDI: A co-construction method for participatory modeling in natural resources management. Ecology and Society 2011, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, H.J.; Lambin, E.F. Proximate Causes and Underlying Driving Forces of Tropical Deforestation. BioScience 2002, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, N.; Levi, M. East Meets West in Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Finance: Policy Dialogue and Differentiation on Security, the Timber Trade and 'Alternative' Banking. Asian Criminology 2008, 3, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Dray, A.; Waeber, P. Learning begins when the game is over: Using games to embrace complexity in natural resources management. GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 2016, 25, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, K.J. Transformative experience: An integrative construct in the spirit of Deweyan pragmatism. Educational Psychologist. 2011, 46, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacek, D.W.; Gary, K. Transformative experience and epiphany in education. Theory and Research in Education. 2020, 18, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. How critical reflection triggers transformative learning. Adult and Continuing Education: Teaching, learning and research 2003, 4, 199. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, P.B.; McAdams, E. Gaps in sustainability education: The impact of higher education coursework on perceptions of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Raath, S. , Lazzarini, B., Vargas, V.R., de Souza, L., Anholon, R., Quelhas, O.L.G., Haddad, R., Klavins, M., Orlovic, V.L. The role of transformation in learning and education for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.W. Mind, brain, and education: Building a scientific groundwork for learning and teaching. Mind, Brain, and Education 2009, 3, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarime, M.; Trencher, G.; Mino, T.; et al. Establishing sustainability science in higher education institutions: towards an integration of academic development, institutionalisation, and stakeholder collaborations. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7 (Suppl 1), 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syaharuddin, S.; Mutiani, M.; Handy, M.R.N.; Abbas, E.W.; Jumriani, J. Putting Transformative Learning in Higher Education Based on Linking Capital. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn). 2022, 16, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriz, W.C. A systemic-constructivist approach to the facilitation and debriefing of simulations and games. Simulation & Gaming 2010, 41, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, R. Vygotsky, Piaget, and education: A reciprocal assimilation of theories and educational practices. New Ideas in Psychology 2000, 18, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwin, A.; Oshige, M. Self-regulation, coregulation, and socially shared regulation: Exploring perspectives of social in self-regulated learning theory. Teachers College Record. 2011, 113, 240–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, H.; Mandl, H.; Renkl, A. Was lernen wir in Schule und Hochschule: Träges Wissen?

- Finkelstein, S.; Sharma, U.; Furlonger, B. The inclusive practices of classroom teachers: A scoping review and thematic analysis. International Journal of Inclusive Education 2021, 25, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crookall, D. Engaging (in) gameplay and (in) debriefing. Simulation & Gaming. 2014, 45, 416–427. [Google Scholar]

- Crookall, D. Serious games, debriefing, and simulation/gaming as a discipline. Simulation & Gaming. 2010, 41, 898–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmierbach, M.; Chung, M.Y.; Wu, M.; Kim, K. No one likes to lose. Journal of Media Psychology 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauvelle, É.; Garcia, C. AgriForEst: Un jeu pour élaborer des scénarios sur un terroir villageois d’Afrique Centrale. VertigO - la revue électronique en sciences de l'environnement. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, S.P.; Cornioley, T.; Dray, A.; Waeber, P.O.; Garcia, C.A. Exploring livelihood strategies of shifting cultivation farmers in Assam through games. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chess, C.; Johnson, B.B. Information is not enough. In Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change; Moser, S.C., Dilling, L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: 2007; pp. 223–233. [CrossRef]

- Waeber, P.O.; Stoudmann, N.; Langston, J.D.; Ghazoul, J.; Wilmé, L.; Sayer, J.; Nobre, C.; Innes, J.L.; Fernbach, P.; Sloman, S.A.; Garcia, C.A. Choices we make in times of crisis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.J.; Krajbich, I. Computational modeling of epiphany learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 4637–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelfranchi, C. Mind as an anticipatory device: For a theory of expectations. In Brain, Vision, and Artificial Intelligence: First International Symposium, BVAI 2005, Naples, Italy, October 19–21, 2005. Proceedings 1, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2005; pp. 258–276. 19 October. [CrossRef]

- SIMRA (Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas). Innovative, Sustainable and Inclusive Bioeconomy, Topic ISIB-03-2015. 2016. Available online: www.simra-h2020.eu (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Melnykovych, M.; Nijnik, M.; Soloviy, I.; Nijnik, A.; Sarkki, S.; Bihun, Y. Social-ecological innovation in remote mountain areas: Adaptive responses of forest-dependent communities to the challenges of a changing world. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijnik, M.; Kluvánková, T.; Nijnik, A.; Kopiy, S.; Melnykovych, M.; Sarkki, S.; Barlagne, C.; Brnkaláková, S.; Kopiy, L.; Fizyk, I.; Miller, D. Is There a Scope for Social Innovation in Ukrainian Forestry? Sustainability. 2020, 12, 9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).