Submitted:

23 May 2023

Posted:

25 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2021, 71, 209–49. [CrossRef]

- Leporrier J, Maurel J, Chiche L, Bara S, Segol P, Launoy G. A population-based study of the incidence, management and prognosis of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2006, 93, 465–474. [CrossRef]

- Choti MA, Sitzmann JV, Tiburi MF, Sumetchotimetha W, Rangsin R, Schulick RD, et al. Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2002, 235, 759–66. [CrossRef]

- Mann CD, Metcalfe MS, Leopardi LN, Maddern GJ. The clinical risk score: emerging as a reliable preoperative prognostic index in hepatectomy for colorectal metastases. Arch Surg. 2004, 139, 1168–72. [CrossRef]

- Cummings LC, Payes JD, Cooper GS. Survival after hepatic resection in metastatic colorectal cancer: a population-based study. Cancer 2007, 109, 718–26. [CrossRef]

- Reich, H.; McGlynn, F.; DeCaprio, J.; Budin, R. Laparoscopic excision of benign liver lesions. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991, 78 Pt 2, 956–958. 1: PMID, 1833. [Google Scholar]

- Katkhouda, N.; Fabiani, P.; Benizri, E.; Mouiel, J. Laser resection of a liver hydatid cyst under videolaparoscopy. Br. J. Surg. 1992, 79, 560–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koffron, A. , Geller, D. , Gamblin, T. C. & Abecassis, M. Laparoscopic liver surgery: Shifting the management of liver tumors. Hepatology 2006, 44, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson NR, Hauch A, Hu T, Buell JF, Slakey DP, Kandil E. The safety and efficacy of approaches to liver resection: a meta-analysis. JSLS 2015, 19, e2014⋅00186. [CrossRef]

- Schiffman SC, Kim KH, Tsung A, Marsh JW, Geller DA. Laparoscopic versus open liver resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: a metaanalysis of 610 patients. Surgery 2015, 157, 211–222. [CrossRef]

- Koffron AJ, AuffenbergG,Kung R,Abecassis M. Evaluation of 300 minimally invasive liver resections at a single institution: less is more. Ann Surg. 2007, 246, 385–92. [CrossRef]

- Simillis C, Constantinides VA, Tekkis PP, Darzi A, Lovegrove R, Jiao L, et al. Laparoscopic versus open hepatic resections for benign and malignant neoplasm meta-analysis. Surgery. 2007, 141, 203–11. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen KT, Marsh JW, Tsung A, Steel JJ, Gamblin TC, Geller DA. Comparative benefits of laparoscopic vs open hepatic resection: a critical appraisal. Arch Surg. 2011, 146, 348–56. [CrossRef]

- Rao A, Rao G, Ahmed I. Laparoscopic or open liver resection? Let systematic review decide it. Am J Surg. 2012, 204, 222–31. [CrossRef]

- Castaing D, Vibert E, Ricca L, Azoulay D, Adam R, Gayet B. Oncologic results of laparoscopic versus open hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases in two specialized centers. Ann Surg 2009, 250, 849–855. [CrossRef]

- Fretland, A.A.; Dagenborg, V.J.; Bjornelv, G.M.W.; Kazaryan, A.M.; Kristiansen, R.; Fagerland, M.W.; Hausken, J.; Tonnessen, T.I.; Abildgaard, A.; Barkhatov, L.; et al. Laparoscopic versus open resection for colorectal liver metastases: The OSLO-COMET randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the eects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamina, M.; Guller, U.; Weber, W.P.; Oertli, D. Propensity scores and the surgeon. Br. J. Surg. 2006, 93; 389–394. [CrossRef]

- Tzanis D, Shivathirthan N, Laurent A, Abu Hilal M, Soubrane O, Kazaryan AM, et al. European experience of laparoscopic major hepatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013, 20, 120–124. [CrossRef]

- Ciria R, Cherqui D, Geller DA, et al. Comparative short-term benefits of laparoscopic liver resection: 9000 cases and climbing. Ann Surg. 2016, 263, 761–77. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani F, Rawashdeh M, Stanton L, et al. Propensity score–based analysis of outcomes of laparoscopic versus open liver resection for colorectal metastases. Br J Surg. 2016, 103, 1504–1512. [CrossRef]

- Montalti R, Berardi G, Laurent S, Sebastiani F, Ferdinande L, Libbrecht LJ et al. Laparoscopic liver resection compared to open approach in patients with colorectal liver metastases improves further resectability: oncological outcomes of a case–control matched-pairs analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014, 40, 536–544. [CrossRef]

- Untereiner X, Cagniet A, Memeo R, Tzedakis S, Piardi T, Severac F, et al. Laparoscopic hepatectomy versus open hepatectomy for colorectal cancer liver metastases: comparative study with propensity score matching. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr [Internet]. 2016, 5, 290–9. [CrossRef]

- Ratti F, Fiorentini G, Cipriani F, Catena M, Paganelli M, Aldrighetti L. Laparoscopic vs open surgery for colorectal liver metastases. JAMA Surg [Internet]. 2018, 153, 1028–35. [CrossRef]

- Beppu T, Wakabayashi G, Hasegawa K, Gotohda N, Mizuguchi T, Takahashi Y, et al. Long-term and perioperative outcomes of laparoscopic versus open liver resection for colorectal liver metastases with propensity score matching: a multi-institutional Japanese study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci [Internet]. 2015, 22, 711–20. [CrossRef]

- Kazaryan AM, Marangos IP, Røsok BI, Rosseland AR, Villanger O, Fosse E et al. Laparoscopic resection of colorectal liver metastases: surgical and long-term oncologic outcome. Ann Surg 2010, 252, 1005–1012. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X-L, Liu R-F, Zhang D, Zhang Y-S, Wang T. Laparoscopic versus open liver resection for colorectal liver metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies with propensity score-based analysis. Int J Surg [Internet]. 2017, 44, 191–203.

- Robles-Campos R, Lopez-Lopez V, Brusadin R, Lopez-Conesa A, Gil-Vazquez PJ, Navarro-Barrios Á, et al. Open versus minimally invasive liver surgery for colorectal liver metastases (LapOpHuva): a prospective randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc [Internet]. 2019, 33, 3926–36. [CrossRef]

- Wong-Lun-Hing EM, van Dam RM, van Breukelen GJP, Tanis PJ, Ratti F, van Hillegersberg R, et al. Randomized clinical trial of open versus laparoscopic left lateral hepatic sectionectomy within an enhanced recovery after surgery programme (ORANGE II study). Br J Surg [Internet]. 2017, 104, 525–35. [CrossRef]

- Berardi G, Van Cleven S, Fretland ÅA, et al. Evolution of laparoscopic liver surgery from innovation to implementation to mastery: perioperative and oncologic outcomes of 2,238 patients from 4 European specialized centers. J Am Coll Surg. 2017, 225, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks KR, Kuo YH, Davis JM, O’ Brien B, Hagopian EJ. Laparoscopic versus open liver resection: a meta-analysis of long-term outcome. HPB (Oxford). 2014, 16, 109–18. [CrossRef]

- Fretland AA, Sokolov A, Postriganova N, Kazaryan AM, Pischke SE, Nilsson PH, et al. Inflammatory response after laparoscopic versus open resection of colorectal liver metastases: Data from the Oslo-CoMet trial. Medicine (Baltimore) [Internet]. 2015, 94, e1786. [CrossRef]

- Tohme S, Goswami J, Han K, et al. Minimally invasive resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases leads to an earlier initiation of chemotherapy compared to open surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015, 19, 2199–2206. [CrossRef]

| Open | Laparoscopic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 212 | 91 | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years)* | 66 (57-72) | 69 (61.5-74) | 0.054 |

| Sex (male) | 134 (63.2) | 54 (59.3) | 0.891 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 27.1 (24.1-30.4) | 26.1 (23.4-29.4) | 0.054 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scale 1 2 3 4 |

15 (7.1) 146 (68.9) 50 (23.6) 1 (0.5) |

9 (9.9) 69 (75.8) 13 (14.3) 0 (0.0) |

0.246 |

| Anaerobic threshold$ (ml/min/kg) | 11.5 (±3.3) | 12.0 (±2.7) | 0.283 |

| Hemoglobin (Hb)$ (g/L) | 134 (±15.3) | 134 (±15.4) | 0.848 |

| White Cell Count (WCC)$ (109/L) | 7.39 (±5.05) | 6.95 (±1.73) | 0.415 |

| Tumour biology | |||

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)* (ng/mL) | 5.4 (2.4-18.7) | 5.3 (2.4-14.4) | 0.094 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 134 (63.2) | 46 (50.5) | 0.054 |

| Synchronous primary | 121 (57.1) | 49 (53.8) | 0.694 |

| Right-sided primary | 157 (74.1) | 69 (75.8) | 0.857 |

| Node positive primary | 133 (62.7) | 53 (58.2) | 0.543 |

| Synchronous lung metastasis | 36 (17.0) | 10 (11.0) | 0.247 |

| Bilobar liver metastasis | 98 (46.2) | 24 (26.4) | 0.002 |

| Number of metastases* | 2 (1-4) | 1 (1-3) | 0.002 |

| Largest metastasis (mm)* | 30 (20-50) | 30 (20-40) | 0.579 |

| Major hepatectomy | 91 (42.9) | 30 (33.0) | 0.135 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Pringle time (min) * | 25 (7-43) | 37 (9-55) | 0.042 |

| Highest intra-operative lactate* | 2.3 (1.5-3.3) | 2.5 (1.5-3.5) | 0.511 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml) * | 450 (200-920) | 300 (100-500) | 0.002 |

| Operation time (min) * | 190 (150-270) | 240 (180-300) | 0.002 |

| ITU stay (days) * | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-1) | 0.091 |

| Hospital stay (days) * | 6 (5-9) | 5 (3-6) | 0.0008 |

| Complication >grade II | 30 (14.2) | 9 (9.9) | 0.354 |

| R1 (any metastasis+) | 76 (35.9) | 22 (24.2) | 0.060 |

| Closest margin (mm) * | 2 (0.2-6) | 5 (1-10) | 0.002 |

| 30-day mortality | 2 (0.94) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

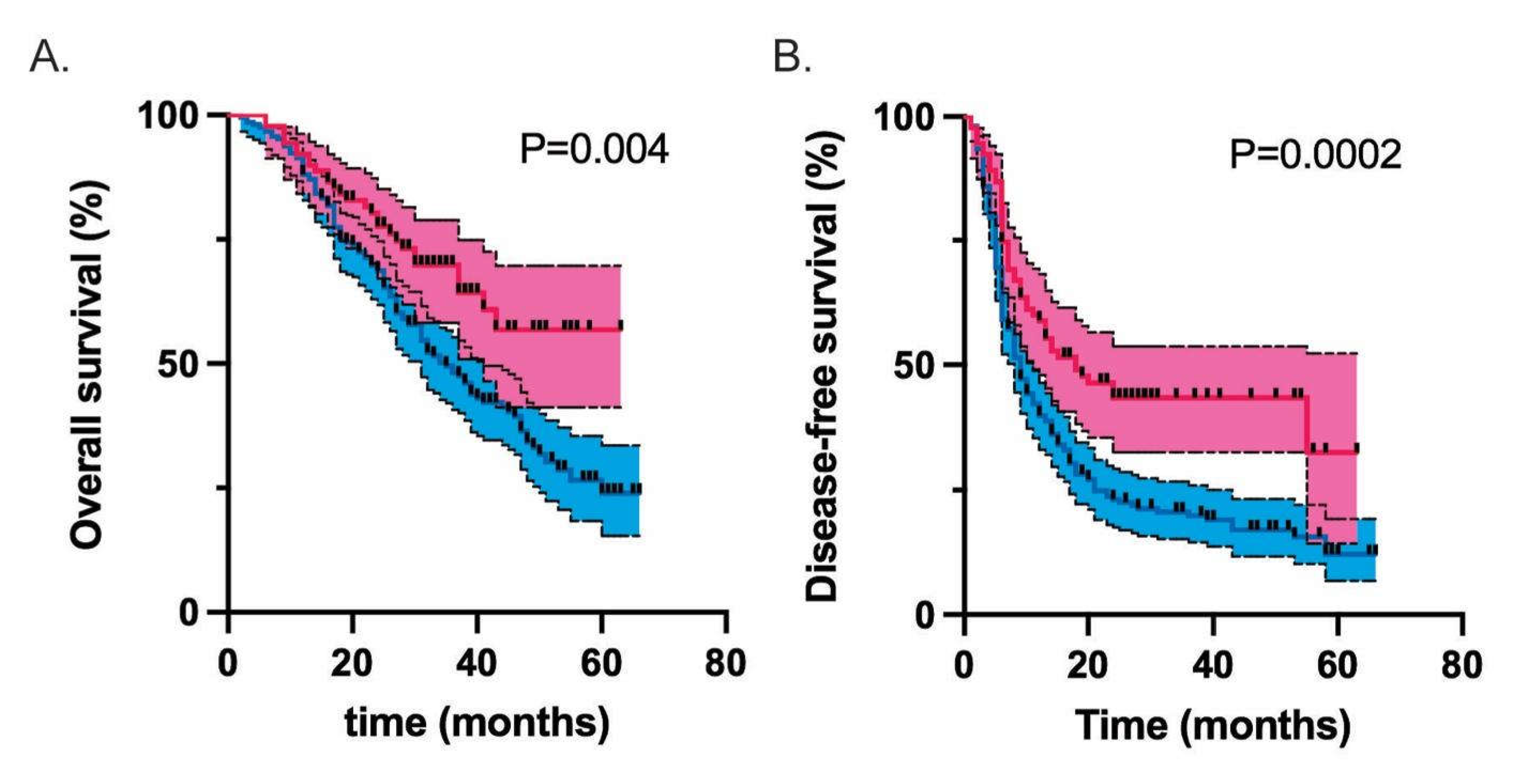

| Median overall survival (months) | 35 | Undefined | 0.004 |

| Median disease-free survival (months) | 9 | 18 | 0.0003 |

| Open | Laparoscopic | P | |

| Total N (%) | 82 (50.0) | 82 (50.0) | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years)* | 68 (61-75) | 69 (59-74) | 0.856 |

| Sex (male) | 48 (58.5) | 51 (62.2) | |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 25.9 (23.5-28.7) | 26.5 (24.0-29.8) | 0.302 |

| ASA 1 2 3 |

9 (11.0) 58 (70.7) 15 (18.3) |

9 (11.0) 60 (73.2) 13 (15.9) |

0.915 |

| Anaerobic threshold$ (ml/min/kg) | 12.0 (±2.9) | 11.8 (±2.8) | 0.680 |

| Hb$ (g/L) | 133 (±15.1) | 133 (±15.9) | 0.994 |

| WCC$ (109/L) | 6.82 (±1.6) | 6.86 (±1.13) | 0.907 |

| Tumour biology | |||

| CEA* (ng/mL) | 5.5 (2.8-17.8) | 5.0 (2.3-14.1) | 0.269 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 49 (59.8) | 44 (53.7) | 0.528 |

| Synchronous primary | 51 (62.2) | 43 (52.4) | 0.269 |

| Right-sided primary | 61 (74.4) | 62 (75.6) | 1.0 |

| Node positive primary | 55 (67.1) | 48 (58.5) | 0.332 |

| Synchronous lung metastases | 13 (15.9) | 10 (12.2) | 0.653 |

| Bilobar metastases | 30 (36.6) | 24 (29.3) | 0.406 |

| Number of metastases* | 2 (1-3) | 1 (1-3) | 0.492 |

| Largest metastasis (mm)* | 30 (20-45) | 30 (22-41.5) | 0.789 |

| Major hepatectomy | 28 (34.1) | 29 (35.4) | 1.0 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Pringle time (min) * | 21.5 (2.0-40.5) | 40 (12-55.5) | 0.005 |

| Highest intra-operative lactate* | 2.23 (1.6-3.1) | 2.5 (1.5-3.5) | 0.499 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml) * | 400 (150-738) | 300 (100-500) | 0.026 |

| Operation time (min) * | 160 (120-240) | 240 (180-300) | <0.0001 |

| ITU stay (days) * | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-1) | 0.912 |

| Hospital stay (days) * | 6 (5-8) | 5 (3-6) | 0.014 |

| Complication >grade II | 6 (7.3) | 7 (8.5) | 1.0 |

| R1 (any metastasis+) | 29 (35.4) | 21 (25.6) | 0.235 |

| Closest margin (mm) * | 2 (0-6) | 5 (1-10) | 0.008 |

| 30-day mortality | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

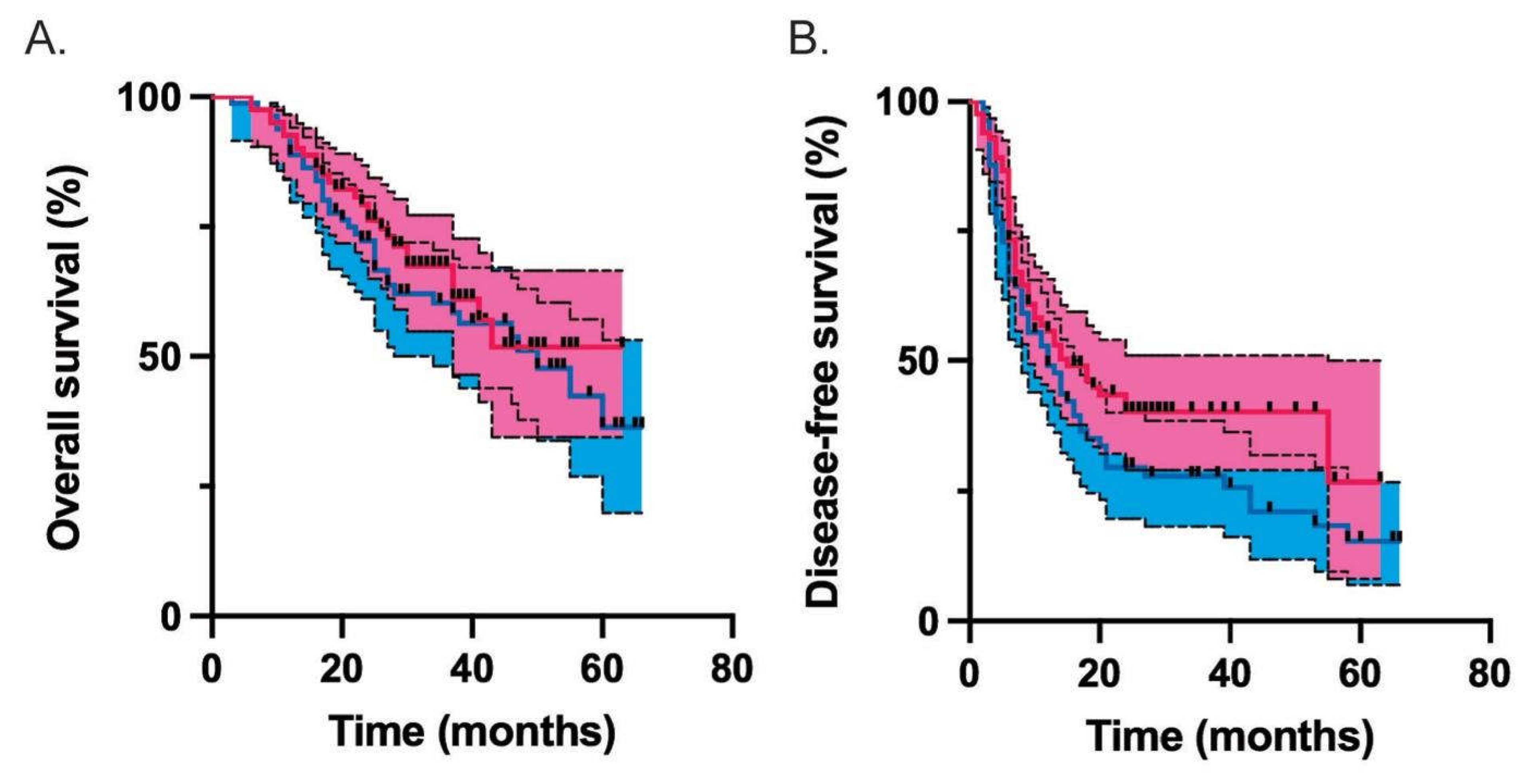

| Median overall survival (months) | 50 | undefined | 0.442 |

| Median disease-free survival (months) | 12 | 15 | 0.096 |

| Model | Overall survival | Disease-free survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Unadjusted | 0.59 (0.42-0.85) | 0.004 | 0.55 (0.41-0.76) | <0.001 |

| Propensity score matched | 0.83 (0.51-1.36) | 0.442 | 0.74 (0.5-1.09) | 0.129 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).