Submitted:

24 May 2023

Posted:

25 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

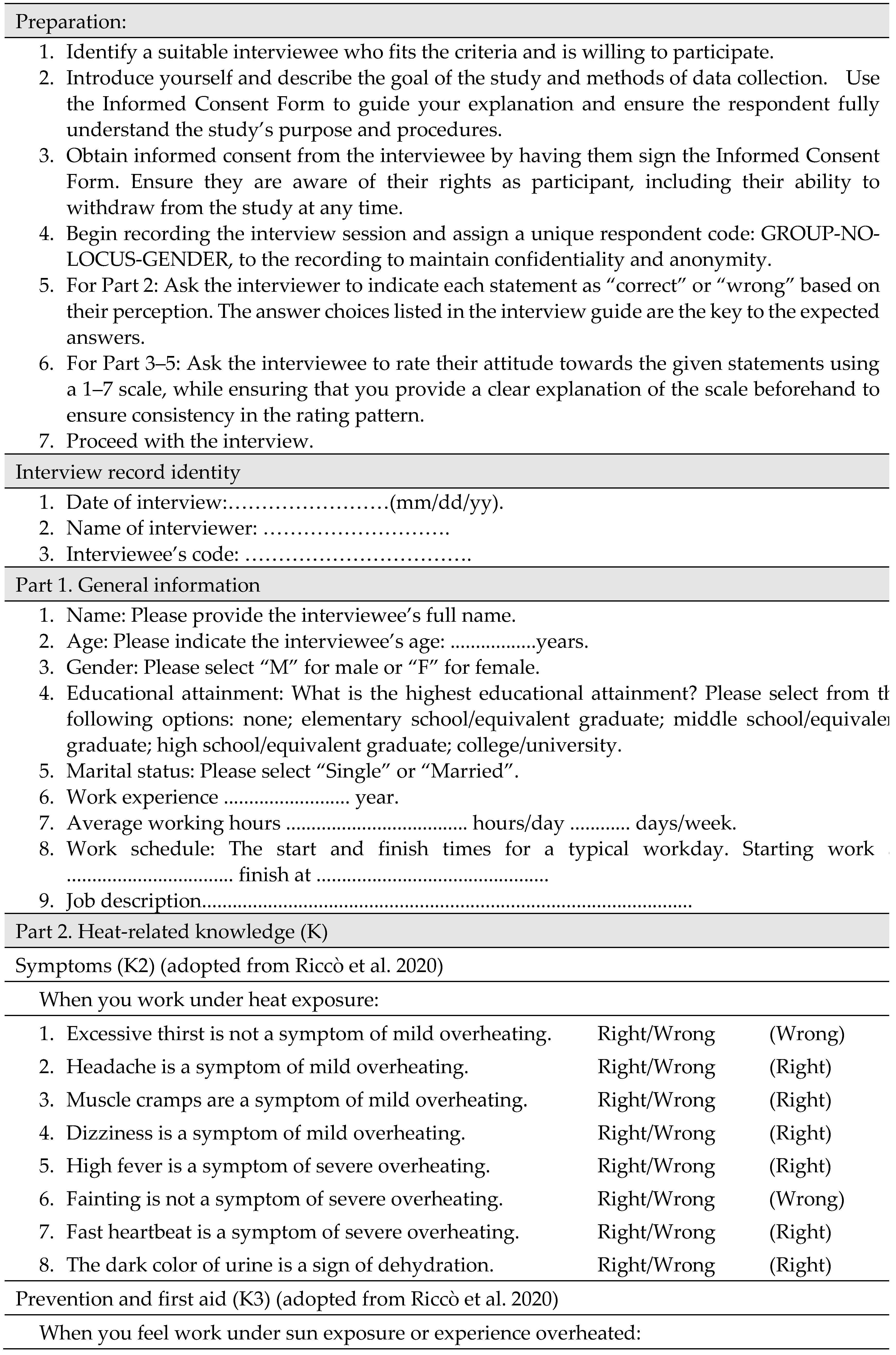

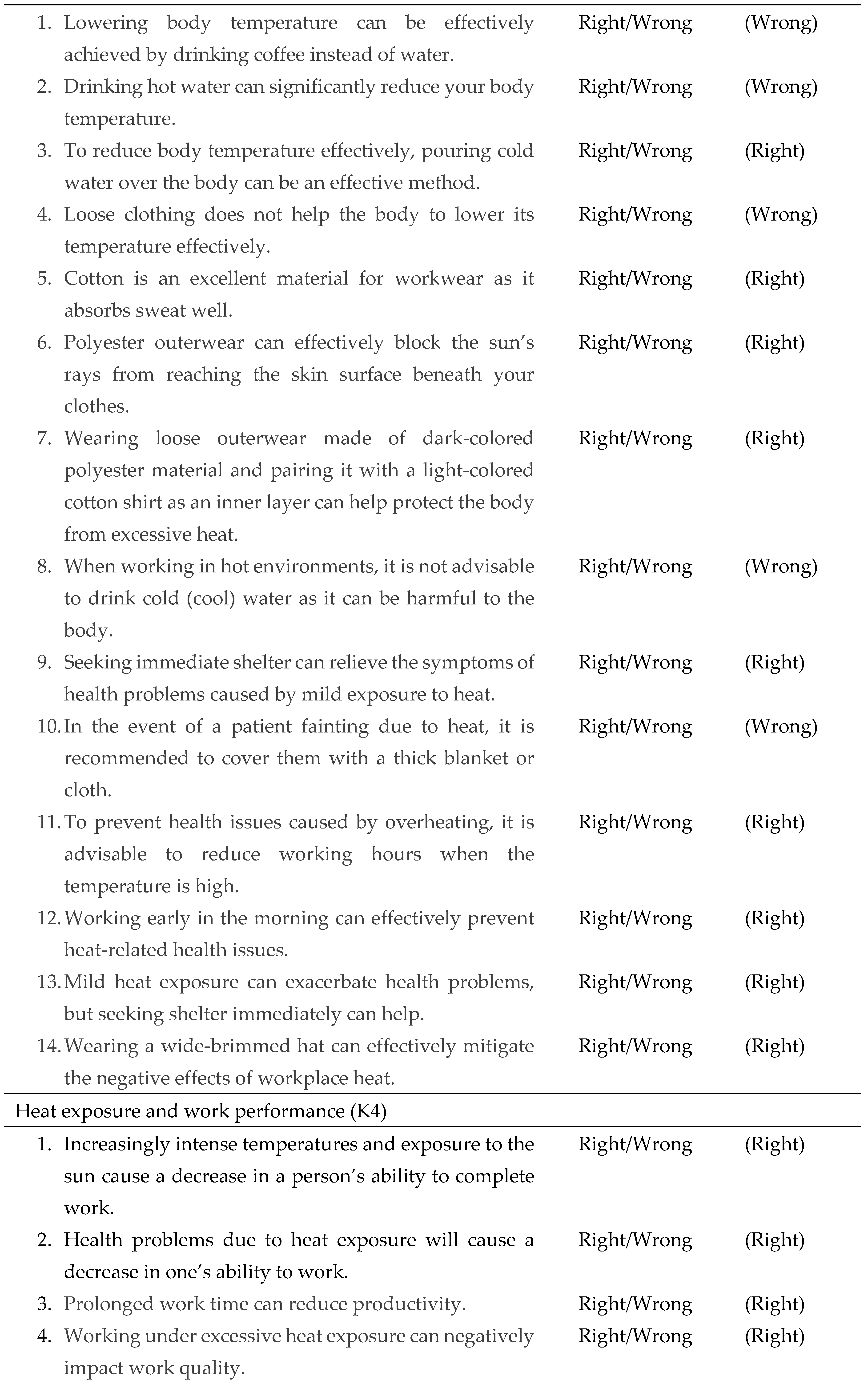

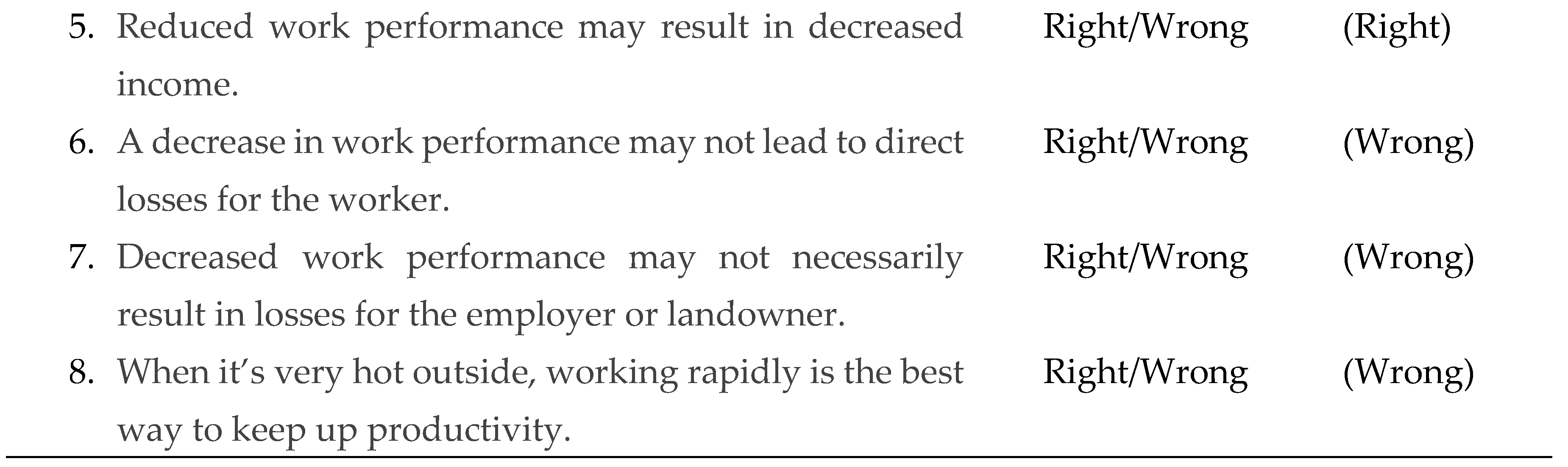

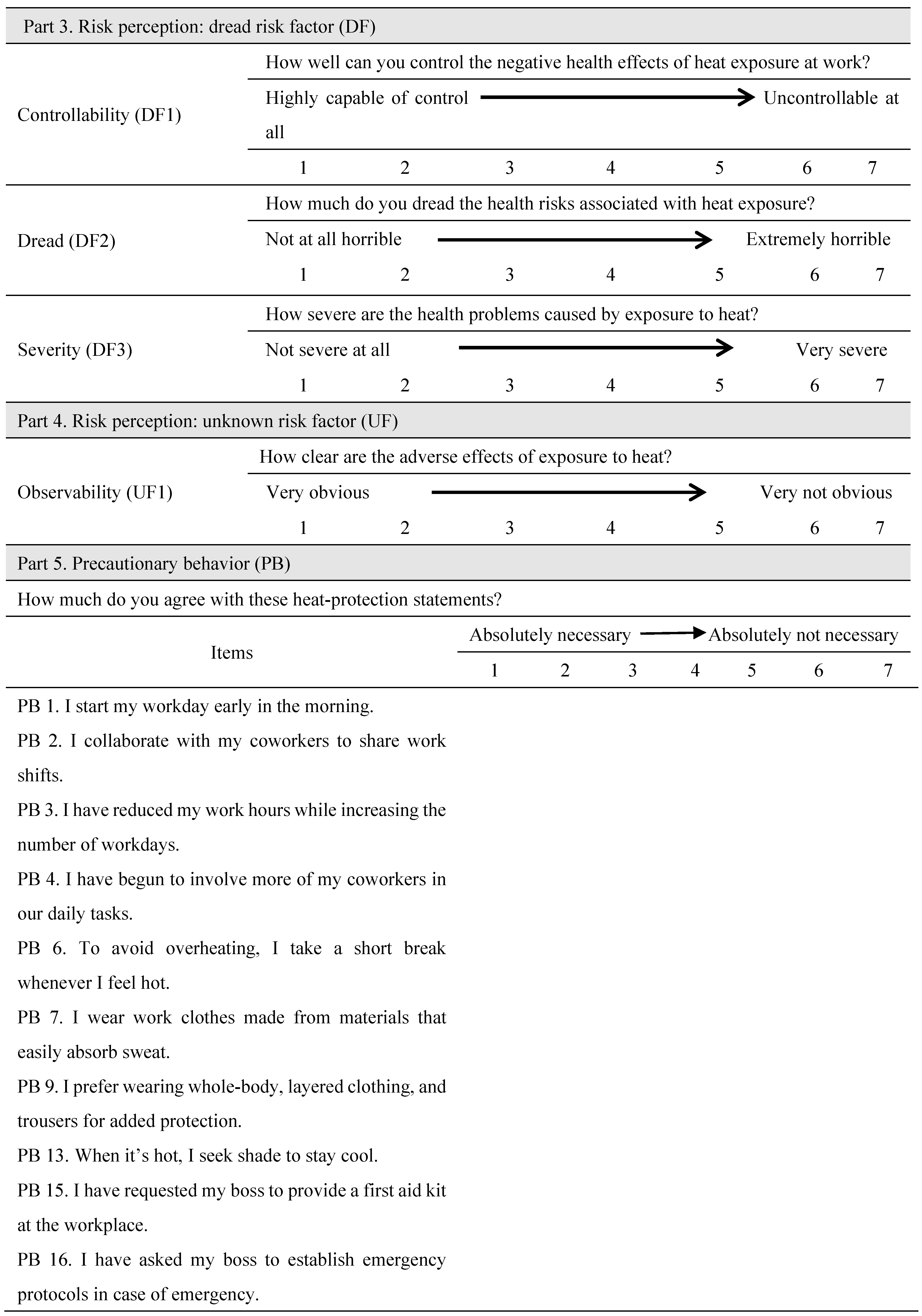

2. Materials and Methods

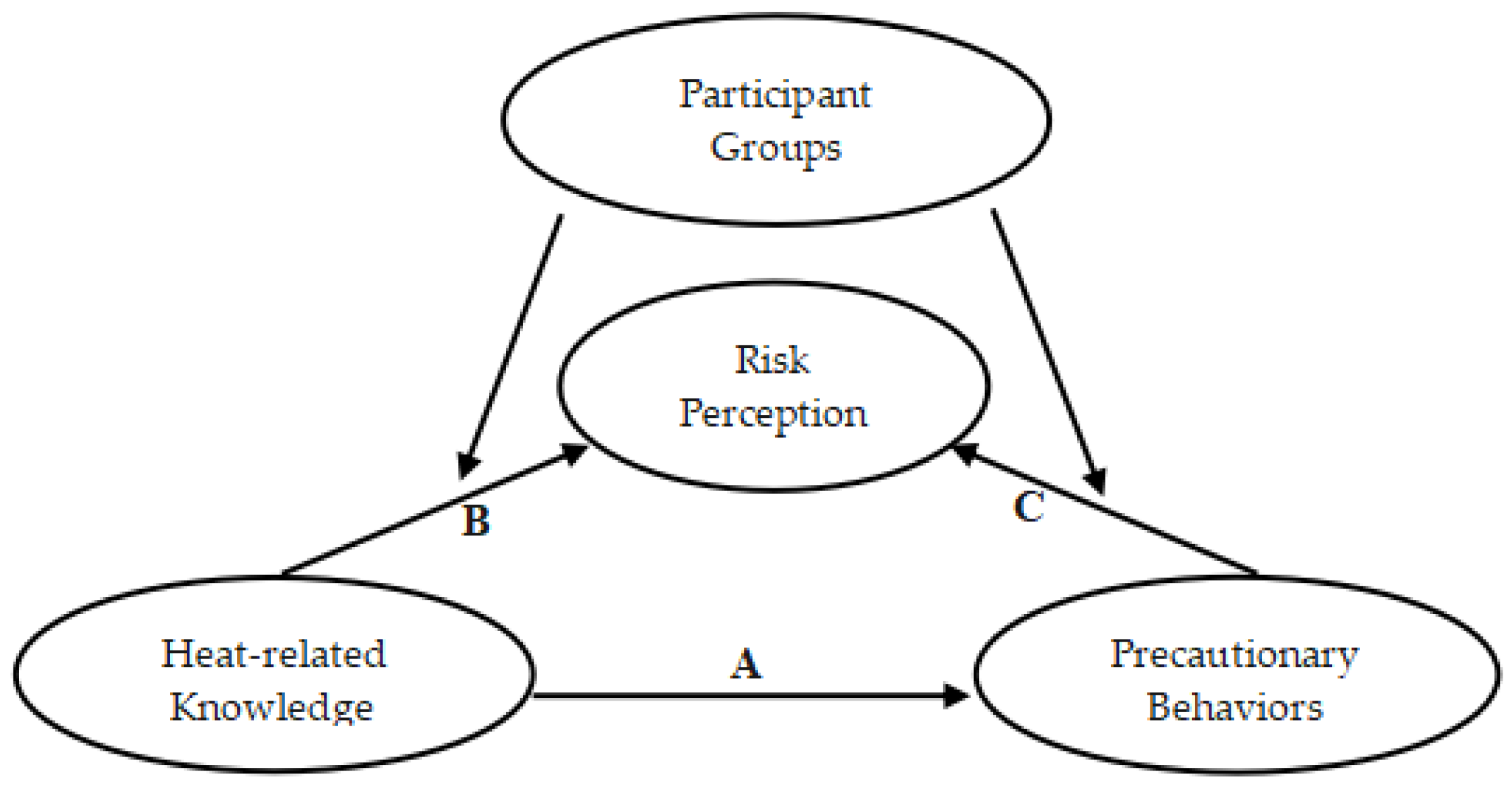

2.1. Hypothesis

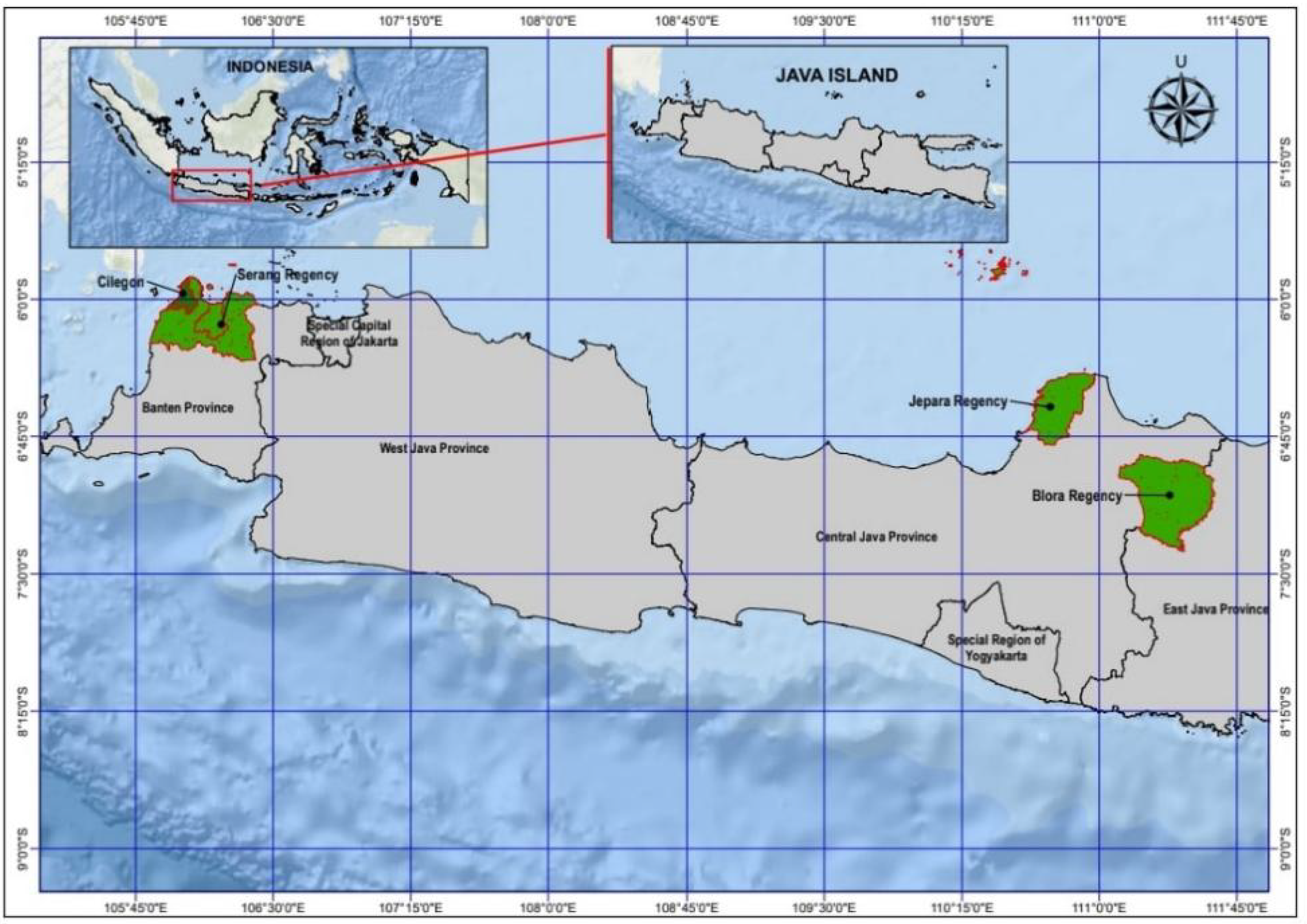

2.2. Survey and Survey Participants

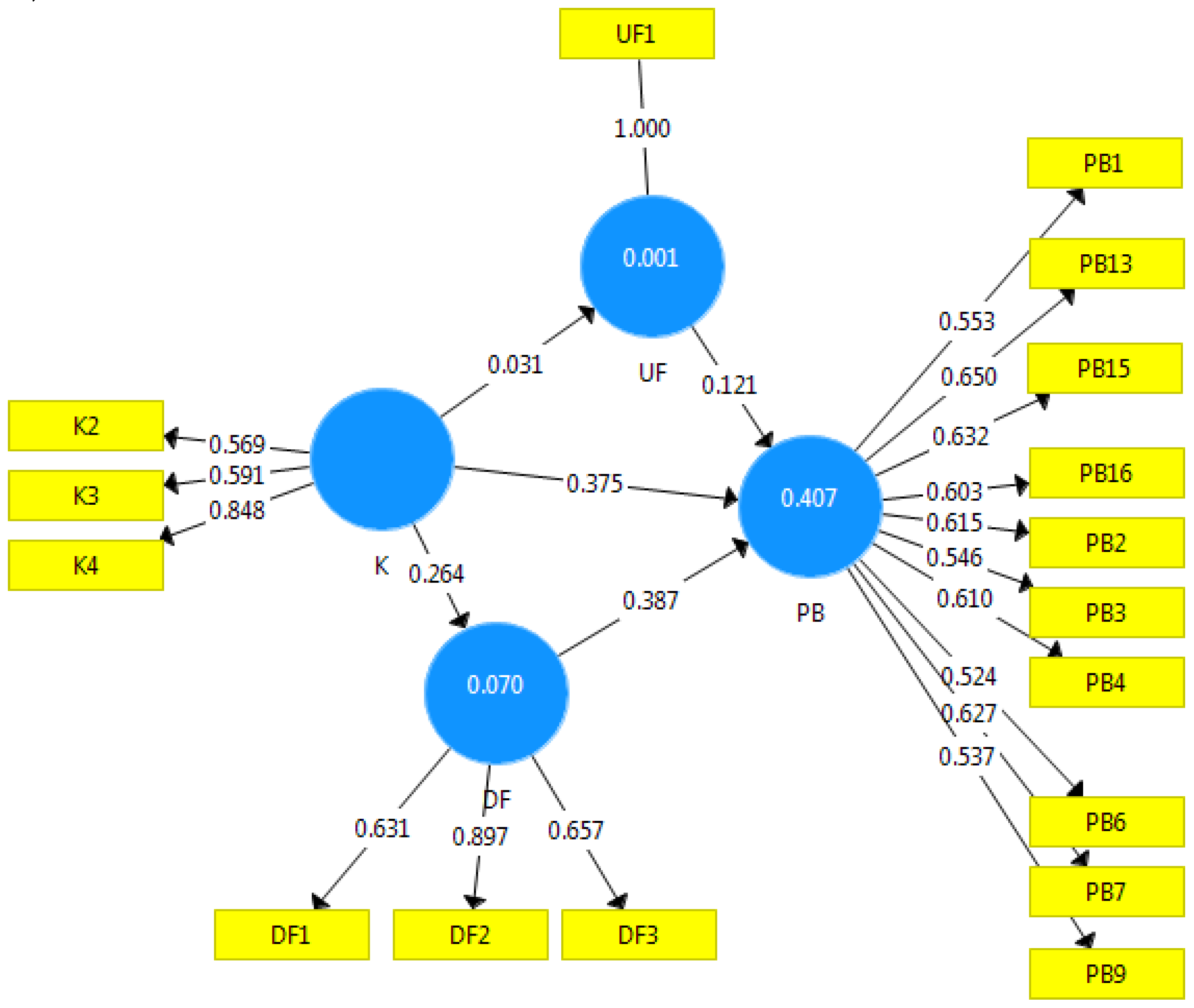

2.3. Models

2.4. Latent variables

3. Results

3.1. Structural Model Evaluation

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- IPCC, ‘Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.’, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. K. R. Matthews, R. L. T. K. R. Matthews, R. L. Wilby, and C. Murphy, ‘Communicating the deadly consequences of global warming for human heat stress’, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 114, no. 15, pp. 3861–3866, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Mora et al., ‘Global risk of deadly heat’, Nat Clim Chang, vol. 7, no. 7, pp. 501–506, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Badan Meteorologi, Klimatologi, dan Geofisika (BMKG), ‘Perubahan Iklim: Proyeksi Perubahan Iklim.’, 2022. https://www.bmkg.go.id/iklim/?p=proyeksi-perubahan-iklim (accessed Sep. 18, 2022).

- BPS, ‘Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia 2013′, 2013.

- BPS, ‘Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia 2021′, 2021.

- T. Kjellstrom, D. T. Kjellstrom, D. Briggs, C. Freyberg, B. Lemke, M. Otto, and O. Hyatt, ‘Heat, Human Performance, and Occupational Health: A Key Issue for the Assessment of Global Climate Change Impacts’, Annu Rev Public Health, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 97–112, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Oppermann, T. E. Oppermann, T. Kjellstrom, B. Lemke, M. Otto, and J. K. W. Lee, ‘Establishing intensifying chronic exposure to extreme heat as a slow onset event with implications for health, wellbeing, productivity, society and economy’, Curr Opin Environ Sustain, vol. 50, pp. 225–235, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Constance and B. Shandro, ‘Heat-related Illness’, in A Practical Guide to Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Caring for Children in the Emergency Department, N. E. Amieva-Wang, Ed., New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011, pp. 234–236. [Online]. Available: http://assets.cambridge.org/97805217/00085/frontmatter/9780521700085_frontmatter.

- M. Riccò et al., ‘Risk perception of heat related disorders on the workplaces: A survey among health and safety representatives from the autonomous province of Trento, Northeastern Italy’, J Prev Med Hyg, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. E66-75, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Varghese, A. B. M. Varghese, A. Hansen, P. Bi, and D. Pisaniello, ‘Are workers at risk of occupational injuries due to heat exposure? A comprehensive literature review’, Saf Sci, vol. 110, pp. 380–392, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Schmeltz, E. P. M. T. Schmeltz, E. P. Petkova, and J. L. Gamble, ‘Economic Burden of Hospitalizations for Heat-Related Illnesses in the United States, 2001–2010′, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 13, no. 9. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Butler, ‘Climate Change, Health and Existential Risks to Civilization: A Comprehensive Review (1989–2013)’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 15, no. 10. 2018. [CrossRef]

- ILO, ‘Working on a warmer planet: The impact of heat stress on labour productivity and decent work’, Geneva, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_711919.

- S. M. Pawson et al., ‘Plantation forests, climate change and biodiversity’, Biodivers Conserv, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 1203–1227, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Boisvenue and S. W. Running, ‘Impacts of climate change on natural forest productivity—evidence since the middle of the 20th century’, Glob Chang Biol, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 862–882, 06. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Spector, Y. J. J. T. Spector, Y. J. Masuda, N. H. Wolff, M. Calkins, and N. Seixas, ‘Heat Exposure and Occupational Injuries: Review of the Literature and Implications’, Curr Environ Health Rep, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 286–296, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Becker, ‘The Health Belief Model and Sick Role Behavior’, Health Educ Monogr, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 409–419, Dec. 1974. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Jones, J. D. C. L. Jones, J. D. Jensen, C. L. Scherr, N. R. Brown, K. Christy, and J. Weaver, ‘The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation’, Health Commun, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 566–576, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Rosenstock, ‘The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior’, Health Educ Monogr, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 354–386, Dec. 1974. [CrossRef]

- E. Y. Yovi, D. E. Y. Yovi, D. Abbas, and T. Takahashi, ‘Safety climate and risk perception of forestry workers: a case study of motor-manual tree felling in Indonesia’, Int J Occup Saf Ergon, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 2193–2201, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Girma, L. S. Girma, L. Agenagnew, G. Beressa, Y. Tesfaye, and A. Alenko, ‘Risk perception and precautionary health behavior toward COVID-19 among health professionals working in selected public university hospitals in Ethiopia’, PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 10, p. e0241101, Oct. 2020, [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Johnson, M. J. E. Johnson, M. Gulanick, S. Penckofer, and J. Kouba, ‘Does Knowledge of Coronary Artery Calcium Affect Cardiovascular Risk Perception, Likelihood of Taking Action, and Health-Promoting Behavior Change?’, J Cardiovasc Nurs, vol. 30, no. 1, 2015.

- K.Y. Kao, C. K.Y. Kao, C. Spitzmueller, K. Cigularov, and C. L. Thomas, ‘Linking safety knowledge to safety behavior: a moderated mediation of supervisor and worker safety attitudes’, Eur J Work Organ Psychol, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 206–220, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. K. Avkiran, ‘Rise of the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: An Application in Banking’, in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Recent Advances in Banking and Finance., N. K. Avkiran and C. M. Ringle, Eds., Springer Link, 2018, p. 267.

- K. J. Preacher and A. F. Hayes, ‘Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models’, Behav Res Methods, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 879–891, 2008. [CrossRef]

- F. Taglioni et al., ‘The influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in Reunion Island: knowledge, perceived risk and precautionary behavior’, BMC Infect Dis, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 34, 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhu and F. Deng, ‘How to Influence Rural Tourism Intention by Risk Knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Attitude’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 10. 2020. [CrossRef]

- BPS of Central Java Province, ‘Suhu Udara 2018–2020′, 2022. https://jateng.bps.go.id/indicator/151/694/1/suhu-udara.html (accessed Sep. 18, 2022).

- BPS of Cilegon City, ‘Keadaan Suhu Udara per Bulan di Kota Cilegon Tahun 2013′, 2013. https://cilegonkota.bps.go.id/statictable/2015/04/22/9/keadaan-suhu-udara-per-bulan-di- kota-cilegon-tahun-2013.html (accessed Sep. 18, 2022).

- BPS of Cilegon City, ‘Suhu Udara Menurut Bulan di kota Cilegon 2017′, 2017. https://cilegonkota.bps.go.id/indicator/151/75/1/suhu-udara-menurut-bulan-di-kota- cilegon-2017.

- L. Peng, J. L. Peng, J. Tan, L. Lin, and D. Xu, ‘Understanding sustainable disaster mitigation of stakeholder engagement: Risk perception, trust in public institutions, and disaster insurance’, Sustain Dev, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 885–897, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Hair, C. M. J. F. Hair, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt, ‘Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance’, Long Range Plann, vol. 46, no. 1–2, pp. 1–12, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Henseler, C. M. J. Henseler, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt, ‘A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling’, J Acad Mark Sci, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 115–135, 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Dijkstra and J. Henseler, ‘Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 297–316, Jan. 2015, [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor. 2662.

- J. F. Hair, G. T. M. J. F. Hair, G. T. M. Hult, R. C.M., and M. Sarstedt, A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), 2nd Editio. SAGE Publications Inc, 2016. [Online]. Available: https://us.sagepub. 2445. [Google Scholar]

- T. Ramayah, C. T. Ramayah, C. Hwa, F. Chuah, H. Ting, and M. Memon, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0: An Updated and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis. 2016.

- P. M. Bentler and D. G. Bonett, ‘Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures.’, Psychol Bull, vol. 88. American Psychological Association, US, pp. 588–606, 1980. [CrossRef]

- T. Kjellstrom, S. T. Kjellstrom, S. Gabrysch, B. Lemke, and K. Dear, ‘The “Hothaps” programme for assessing climate change impacts on occupational health and productivity: an invitation to carry out field studies’, Glob Health Action, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 2082, Nov. 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. Slovic, ‘Perception of Risk’, Science (1979), vol. 236, no. 4799, pp. 280–285, Apr. 1987. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Beckmann and M. Hiete, ‘Predictors Associated with Health-Related Heat Risk Perception of Urban Citizens in Germany’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 3. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Ning et al., ‘The impacts of knowledge, risk perception, emotion and information on citizens’ protective behavior during the outbreak of COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in China’, BMC Public Health, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 1751, 2020. [CrossRef]

- de Zwart, I. K. Veldhuijzen, J. H. Richardus, and J. Brug, ‘Monitoring of risk perceptions and correlates of precautionary behavior related to human avian influenza during 2006–2007 in the Netherlands: results of seven consecutive surveys’, Int J Behav Med, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 2193–2201, Oct. 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. Samadipour, F. E. Samadipour, F. Ghardashi, M. Nazarikamal, and M. Rakhshani, ‘Perception risk, preventive behavior and assessing the relationship between their various dimensions: A cross-sectional study in the Covid-19 peak period’, Int J Disaster Risk Reduc, vol. 77, p. 103093, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Mishra and D. Suar, ‘Do Lessons People Learn Determine Disaster Cognition and Preparedness?’, Psychol Dev Soc J, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 143–159, Dec. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. Brug, A. R. J. Brug, A. R. Aro, A. Oenema, O. de Zwart, J. H. Richardus, and G. D. Bishop, ‘SARS Risk Perception, Knowledge, Precautions, and Information Sources, the Netherlands’, Emerg Infect Dis journal, vol. 10, no. 8, p. 1486, 2004. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Harper, L. P. C. A. Harper, L. P. Satchell, D. Fido, and R. D. Latzman, ‘Functional Fear Predicts Public Health Compliance in the COVID-19 Pandemic’, Int J Ment Health Addict, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 1875–1888, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Iorfa et al., ‘COVID-19 Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Precautionary Behavior Among Nigerians: A Moderated Mediation Approach’, Front Psychol, vol. 11. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020. 5667.

- J. Brug, A. R. J. Brug, A. R. Aro, A. Oenema, O. de Zwart, J. H. Richardus, and G. D. Bishop, ‘SARS Risk Perception, Knowledge, Precautions, and Information Sources, the Netherlands’, Emerg Infect Dis, vol. 10, no. 8, p. 1486, 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Bonafede et al., ‘Perception Heat Stress: Results from a Pilot Study Conducted in Italy during the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020′, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 13. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Mızrak, A. S. Mızrak, A. Özdemir, and R. Aslan, ‘Adaptation of hurricane risk perception scale to earthquake risk perception and determining the factors affecting women’s earthquake risk perception’, Nat Hazards, vol. 109, no. 3, pp. 2241–2259, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Finucane, A. M. L. Finucane, A. Alhakami, P. Slovic, and S. M. Johnson, ‘The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits’, J Behav Decis Mak, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- K. Skagerlund, M. K. Skagerlund, M. Forsblad, P. Slovic, and D. Västfjäll, ‘The Affect Heuristic and Risk Perception—Stability Across Elicitation Methods and Individual Cognitive Abilities’, Front Psychol, vol. 11. 2020.

- K. P. Poulianiti, G. K. P. Poulianiti, G. Havenith, and A. D. Flouris, ‘Metabolic energy cost of workers in agriculture, construction, manufacturing, tourism, and transportation industries’, Ind Health, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 283–305, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Y. Yovi and Y. Yamada, ‘Addressing Occupational Ergonomics Issues in Indonesian Forestry: Laborers, Operators, or Equivalent Workers.’, Croat J For Eng, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 351–363, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Y. Yovi and W. Prajawati, ‘High risk posture on motor-manual short wood logging system in Acacia mangium plantation’, Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 11–18, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Orom, R. J. W. H. Orom, R. J. W. Cline, T. Hernandez, L. Berry-Bobovski, A. G. Schwartz, and J. C. Ruckdeschel, ‘A Typology of Communication Dynamics in Families Living a Slow-Motion Technological Disaster’, J Fam Issues, vol. 33, no. 10, pp. 1299–1323, Jan. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Staupe-Delgado, ‘Progress, traditions and future directions in research on disasters involving slow-onset hazards’, Disaster Prev Manag, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 623–635, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Meraklı and S. Küçükyavuz, ‘Risk aversion to parameter uncertainty in Markov decision processes with an application to slow-onset disaster relief’, IISE Trans, vol. 52, no. 8, pp. 811–831, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Nixon, ‘Slow Violence, Gender, and the Environmentalism’, J Commonw Postcolon Stud, vol. 13, no. 2, 2011.

- K. Morrison, ‘The role of traditional knowledge to frame understanding of migration as adaptation to the “slow disaster” of sea level rise in the South Pacific’, in Identifying emerging issues in disaster risk reduction, migration, climate change and sustainable development., K. Sudmeier-Rieux, M. Fernández, I. M. Penna, J. M., and J. C. Gaillard, Eds., Springer, 2017, pp. 249–266.

- S. K. Beckmann and M. Hiete, ‘Predictors Associated with Health-Related Heat Risk Perception of Urban Citizens in Germany’, Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 17, no. 3. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Schweiker, G. M. M. Schweiker, G. M. Huebner, B. R. M. Kingma, R. Kramer, and H. Pallubinsky, ‘Drivers of diversity in human thermal perception—A review for holistic comfort models’, Temperature, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 308–342, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Seimetz, S. E. Seimetz, S. Kumar, and H.-J. Mosler, ‘Effects of an awareness raising campaign on intention and behavioral determinants for handwashing’, Health Educ Res, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 109–120, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Whitmer and V. K. Sims, ‘Fear Language in a Warning Is Beneficial to Risk Perception in Lower-Risk Situations’, Hum Factors, p. 00187208211029444, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Lefevre, W. C. E. Lefevre, W. Bruine de Bruin, A. L. Taylor, S. Dessai, S. Kovats, and B. Fischhoff, ‘Heat protection behavior and positive affect about heat during the 2013 heat wave in the United Kingdom’, Soc Sci Med, vol. 128, pp. 282–289, 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Hass, J. D. L. Hass, J. D. Runkle, and M. M. Sugg, ‘The driving influences of human perception to extreme heat: A scoping review’, Environ Res, vol. 197, p. 111173, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Y. Yovi, Y. E. Y. Yovi, Y. Yamada, M. Zaini, C. Kusumadewi, and L. Marisiana, ‘Improving the OSH knowledge of Indonesian forestry workers by using safety game application: Tree felling supervisors and operators’, Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 75–83, 2016.

- L. Duckworth and J. J. Gross, ‘Behavior change’, Organ Behav Hum Decis Process, vol. 161, pp. 39–49, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forestry workers | Paddy farmers | ||

| Age | Mean = 44; SD = 11 | Mean = 50; SD = 13 | |

| Gender | Female | 27 | 118 |

| Male | 183 | 97 | |

| Education | Elementary school | 123 | 168 |

| Middle-high school | 85 | 47 | |

| College degree | 2 | 0 | |

| Marital status | Single | 34 | 94 |

| Married | 176 | 121 | |

| Work experience | Mean = 9; SD = 8 | Mean = 9; SD = 8 | |

| Work hour/day | Mean = 7; SD = 1 | Mean = 7; SD = 1 | |

| Variable | Sub-variable |

|---|---|

| Heat-related knowledge | Symptoms (K2) |

| Prevention and first aid (K3) | |

| Work performance (K4) | |

| Risk perception | |

| Dread risk factor (DF) | Controllability (DF1) |

| Dread (DF2) Severity (DF3) | |

| Unknown risk factor (UF) | Observability (UF1) |

| Precautionary behavior (PB) | I start my workday early in the morning (PB1) |

| I collaborate with my coworkers to share work shifts (PB2) | |

| I have reduced my work hours while increasing the number of workdays (PB3) | |

| I have begun to involve more of my coworkers in our daily tasks (PB4) | |

| To avoid overheating, I take a short break whenever I feel hot (PB6) | |

| I wear work clothes made from materials that easily absorb sweat (PB7) | |

| I prefer wearing whole-body, layered clothing, and trousers for added protection (PB9) | |

| When it’s hot, I seek shade to stay cool (PB13) | |

| I have requested my boss to provide a first aid kit at the workplace (PB15) | |

| I have asked my boss to establish emergency protocols in case of emergency (PB16) |

| Variable | VIF | Variable | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of signs of health concerns associated with extreme heat-exposure in the workplace (K2) | 1.049 | I have reduced my work hours while increasing the number of workdays (PB3) | 1.257 |

| Heat exposure avoidance and first aid (K3) | 1.087 | I have begun to involve more of my coworkers in our daily tasks (PB4) | 1.344 |

| Heat exposure effect on work performance (K4) | 1.126 | To avoid overheating, I take a short break whenever I feel hot (PB6) | 1.441 |

| Controllability (DF1) | 1.118 | I wear work clothes made from materials that easily absorb sweat (PB7) | 1.777 |

| Dreadness (DF2) | 1.58 | I prefer wearing whole-body, layered clothing, and trousers for added protection (PB9) | 1.404 |

| Severity (DF3) | 1.44 | When it’s hot, I seek shade to stay cool (PB13) | 1.61 |

| Observability (UF1) | 1 | I have requested my boss to provide a first aid kit at the workplace (PB15) | 1.871 |

| I start my workday early in the morning (PB1) | 1.335 | I have asked my boss to establish emergency protocols in case of emergency (PB16) | 1.741 |

| I collaborate with my coworkers to share work shifts (PB2) | 1.357 |

| Variable | R2 | R2 Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dread risk factors (DF) | 0.07 | 0.068 | |

| Precautionary behavior (PB) | 0.407 | 0.403 | |

| Unknown risk factor (UF) | 0.001 | -0.001 |

| Variable | SSO | SSE | Q² (1-SSE/SSO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dread risk factors (DF) | 1,275.00 | 1,063.2 | 0.166 |

| Heat-related knowledge (K) | 1,275.00 | 1,228.2 | 0.037 |

| Precautionary behavior (PB) | 4,250.00 | 3,365.8 | 0.208 |

| Unknown risk factor (UF) | 425 | 1 |

| Value | Saturated Model | Estimated Model |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.097 | 0.098 |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.568 | 0.561 |

| Variable | Original Sample (O) |

Sample Mean (M) | Standard Dev. (STDEV) |

T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values |

Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF→PB | 0.387 | 0.393 | 0.037 | 10.544 | 0 | Significant |

| K→DF | 0.264 | 0.269 | 0.047 | 5.671 | 0 | Significant |

| K→PB | 0.375 | 0.378 | 0.039 | 9.561 | 0 | Significant |

| K →UF | 0.031 | 0.03 | 0.048 | 0.641 | 0.522 | No Sig. |

| UF→PB | 0.121 | 0.119 | 0.038 | 3.203 | 0.001 | Significant |

| Variable | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Dev. (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p values | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K→DF→PB | 0.102 | 0.105 | 0.019 | 5.281 | 0 | Significant |

| K→UF→PB | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.603 | 0.547 | No sig. |

| Moderation Variable | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Dev. (STDEV) | T Statistics (O/STDEV|) | p values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (K→PB) | -0.028 | -0.031 | 0.051 | 0.544 | 0.587 |

| Gender (K→PB) | -0.025 | -0.014 | 0.051 | 0.495 | 0.621 |

| Participant groups (K→PB) | -0.112 | -0.103 | 0.051 | 2.194 | 0.029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).