1. Introduction

Whole-body balance in the standing posture with horizontal gaze is based on the alignment chain from the head to the feet, and it is well known that degenerative changes in spinopelvic alignment cause compensatory changes in alignment including those in the lower extremities [

1,

2,

3]. Several studies have shown that degenerative changes in the spine begin with a decrease in lumbar lordosis (LL) and progress eventually to a spinopelvic imbalance that leads to a reduction of quality of life [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Sagittal vertical axis (SVA) is a spinopelvic sagittal plane parameter that measures the offset between a plumb line from C7 to the pelvis and has been widely used as an indicator of spinopelvic sagittal balance in the treatment of patients with spinal deformity [

1]. Spinopelvic sagittal balance parameters have been reported to deteriorate when degenerative spinal alignment changes exceed compensation by lordotic change of the cervical/thoracic spine and sacral/pelvic rotation [

4,

6].

Knee flexion (KF) is a definitive and effective compensatory mechanism to handle changes in spinopelvic sagittal alignment [

3,

5], and patients with severe spinopelvic imbalance attempt to maintain standing balance by flexing their knee joints [

4,

7]. If spinal malalignment in the sagittal plane exceeds the limits of spinopelvic compensatory mechanisms including pelvic retroversion, knee joint flexion is thought to be recruited. This requires excessive activity of the quadriceps and psoas muscles to maintain a standing posture and is not an economical state [

4]. In addition, the importance of spinopelvic sagittal imbalance on whole-spine radiographs is minimized by KF in patients with severe degenerative spine conditions [

3]. Evaluation of KF is considered necessary when assessing spinopelvic sagittal balance in the treatment of patients with spinal deformity.

There is no doubt that KF and pelvic rotation are effective compensatory mechanisms for handling changes in spinopelvic alignment in the standing position [

8,

9,

10]. However, few studies have addressed whole-body compensatory mechanisms in response to degenerative change of spinopelvic sagittal balance in large healthy cohorts with no history of spinal treatment. The differences in the behavior of compensatory alignment, including that in the lower extremities, between compensated spinopelvic sagittal balance and the decompensated state are still unclear. We hypothesized that if the specific recruitment of KF to compensate for degenerative change of spinopelvic sagittal balance could be clarified, the threshold value of KF angle indicating decompensated spinopelvic balance could be a useful indicator for the treatment of spinal deformity. The purposes of this study were first, to show the differences in the involvement of whole-body compensatory alignment change, including that by the lower extremities, in each condition of compensated and decompensated spinopelvic sagittal balance, and second, to determine the cutoff value of KF angle that suggests spinopelvic sagittal imbalance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

We enrolled 330 healthy subjects from the spine medical checkup database of our hospital. Subjects with any past and/or current medical history of spinal disease or neurological disease or treatment of hip or knee joint disease affecting assessment in the standing posture were excluded from this cross-sectional, observational analysis.

Responses to a questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) score were obtained from all participants to evaluate their clinical complaints, and they all underwent whole-body X-ray using a scanning X-ray imaging system (EOS Imaging, Paris, France). The examination posture was a “hands-on-cheek” posture with their fingers lightly touching together in the standing position with horizontal gaze. The participants were instructed to relax as much as possible during the X-ray.

This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design.

2.2. Whole-body sagittal plane parameters

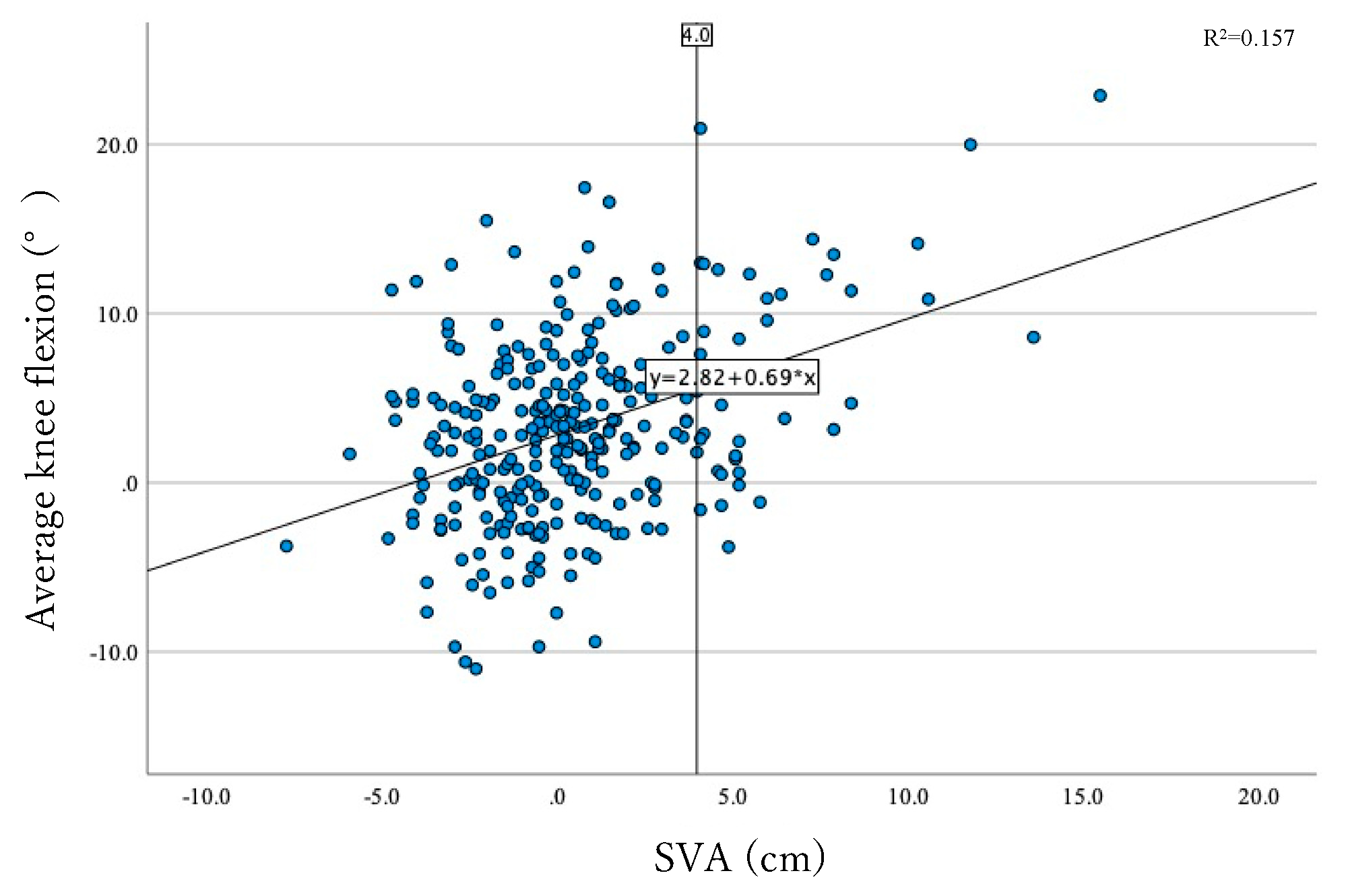

The SterEOS software program (SterEOS 1.6, Postural Assessment Workflow, EOS Imaging) was used to measure the radiographical parameters. Sagittal plane alignment in the whole body from cranio-cervical junction to ankle joint was analyzed in this study. The following parameters were analyzed: occipito-C2 angle (O-C2 angle: McGregor line–C2 endplate), C2-7 lordotic angle (C2 endplate–C7 caudal endplate), T1 slope, thoracic kyphosis (TK: T1-12), LL (L1-S1), sacral slope (SS), pelvic tilt (PT), pelvic incidence (PI), KF angle (average of left and right KF angles, KF angle was measured as an angle between the femoral axis and the tibial axis: the line connecting the intercondylar fossa of the femur and the center of the inferior articular surface of the tibia), and ankle angle (AA: tibia shaft-vertical line) as spinopelvic and lower extremity alignment parameters; and SVA, CAM-HA/knee/ankle offset (the distance from a plumb line from the acoustic meatus to the center of the femoral head/knee joint/ankle joint), and T1 pelvic angle (TPA) as global balance parameters. Kyphosis and lordosis are defined as the angle between the upper endplate of a selected vertebra and the lower endplate of another selected vertebra. The correlation between KF and SVA in the overall subjects enrolled in this analysis was investigated.

2.3. Correlations between lack of ideal lumbar lordosis and whole-body compensation alignment

We divided the subjects into two groups according to the compensation status of spinopelvic sagittal balance. The compensation status was determined by SVA, and subjects with a measured SVA of < 4 cm were assigned to the compensated group (group C), and those with a SVA ≥ 4 cm were assigned to the decompensated group (group D). Patient demographic data including age, sex, height, weight, and ODI [

11] and the radiographic parameters described above were compared between these two groups.

We calculated the ideal lumbar lordosis (iLL) from the measured spinopelvic parameters with reference to the formula proposed by Schwab et al. [

6,

12] and analyzed the correlation of lack of iLL with the compensatory parameters to clarify the recruitment of the compensatory mechanisms in each group: lack of iLL = measured LL – (PI + 9). The compensatory parameters included O-C2 angle, C2-7 lordotic angle, T1-slope, TK (T1-12), SS, PT, KF, and AA.

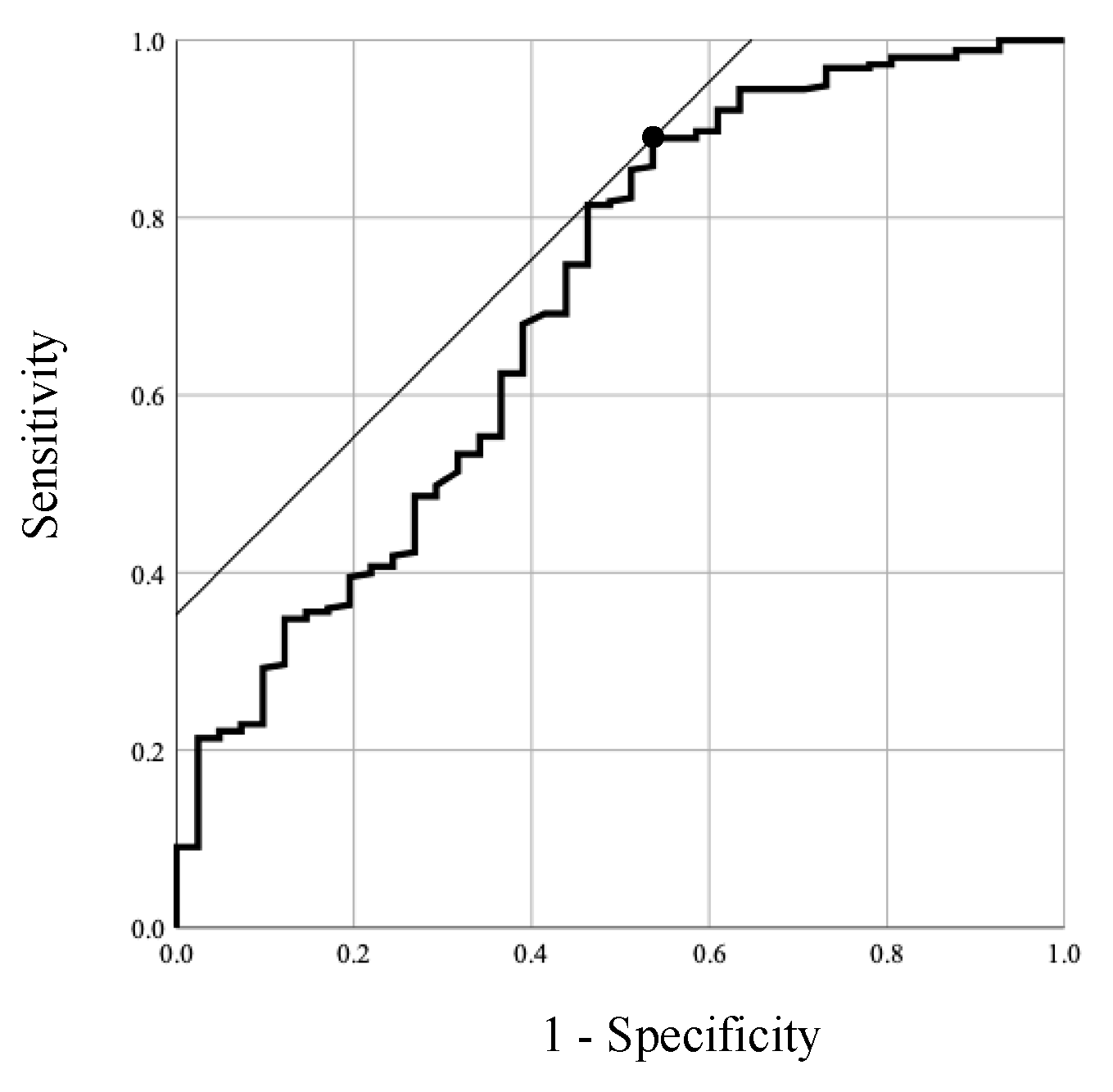

We determined the threshold of KF angle that suggests recruitment of knee joint flexion indicative of a spinopelvic sagittal imbalance by drawing receiver operator characteristics (ROC) curves and performing a cutoff analysis. The existence of spinopelvic sagittal imbalance was defined as SVA > 4 cm, and an ROC curve for KF was drawn. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated, and a cutoff value for KF angle indicating spinopelvic sagittal imbalance was determined at the coordinate point with the maximum sum of sensitivity and specificity.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare demographic data and radiographic parameters of the two compensation groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to show the correlation between KF and SVA and to measure the strength of correlations between lack of iLL mismatch and each compensatory parameter. The strength of the correlation between each parameter was described using the absolute value of r (r = .20–.39: weak, r = .40–.59: moderate, r = .60–.79: strong, and r = .80–1.0: very strong correlation). P values of < .05 were considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analyses.

3. Results

After exclusion of subjects meeting the exclusion criteria, 294 subjects were included in the statistical analysis. Their average age was 58.0 ± 12.7 years, 59.9% of the subjects were male (n=176), and their average ODI score was 11.0 ± 10.2. The overall correlation between SVA and KF was r = .396 (p < .001). A dot plot displaying the correlation between SVA and KF is shown in

Figure 1. There were 253 patients in group C with compensated spinopelvic sagittal balance (SVA < 4) and 41 patients in group D with spinopelvic sagittal imbalance (SVA ≥ 4). The demographic data and radiographic parameters between the two groups can be compared in

Table 1. There were significant differences between group C and group D, respectively, in age (56.7 ± 12.8 and 65.7 ± 9.5 years, p < .001), height (162.2 ± 9.1 and 159.3 ± 9.0 cm, p = .043), ODI score (10.1 ± 9.7 and 16.8 ± 11.4, p = .001), C2-7 lordotic angle (1.3 ± 11.3 and 8.2 ± 10.2 degrees, p < .001), T1-slope (23.3 ± 8.6 and 29.2 ± 8.2 degrees, p < .001), LL (47.4 ± 12.0 and 35.3 ± 18.1 degrees, p < .001), Lack of iLL (-1.4 ± 10.2 and -17.3 ± 15.9 degrees, p < .001), PT (14.2 ± 7.1 and 20.9 ± 10.2 degrees, p < .001), KF (2.5 ± 5.0 and 7.3 ± 6.5 degrees, p < .001), AA (5.3 ± 3.0 and 6.6 ± 3.3 degrees, p = .028), SVA (-0.4 ± 2.1 and 6.2 ± 2.7 cm, p < .001), CAM-HA (-2.4 ± 2.9 and 2.5 ± 3.9 cm, p < .001), CAM-Knee offset (-0.2 ± 2.9 and 2.9 ± 3.8 cm, p < .001), CAM-Ankle offset (2.7 ± 3.0 and 6.8 cm ± 3.4, p < .001), and TPA (9.3 ± 6.5 and 21.0 ± 11.0 degrees, p < .001).

Correlation analysis of Lack of iLL with each compensatory parameter showed a strong correlation for PT (r =-.723, p < .001), a weak correlation for TK (r = 275, p < .001) and SS (r = .267, p < .001), and very weak correlations for KF (r = -.153 , p = .015) and AA (r = -.129, p = .040) in Group C. In Group D, the correlations were strong for PT (r = -.796, p < .001), moderate for TK (r = .462, p = .002), SS (r = .577, p < .001), and KF (r = -.415, p = .007), and weak for AA (r = -.334, p = .033) (

Table 2)

The ROC curve of KF angle for prediction of spinopelvic sagittal imbalance (SVA > 4) is shown in

Figure 2. The AUC was 0.704 (95% confidence interval, 0.61–0.80). The optimal cutoff value for KF angle was determined to be 8.4 degrees, which maximizes the sum of sensitivity (89%) and specificity (46%).

4. Discussion

In this study, differences in the whole-body compensatory parameters of the different compensatory phases of spinopelvic sagittal balance were shown in a relatively large cohort of subjects with no history of spinal treatment. Comparative analysis of the compensatory and decompensatory groups revealed that during the decompensatory phase of spinopelvic sagittal balance, the standing posture is maintained by recruitment of whole-body compensatory parameters from the spine to the feet, excluding craniocervical and cervical alignment. There was a significant correlation between SVA and KF angle in the overall subject population. In contrast, the correlation between Lack of iLL and KF angle was very weak in group C with compensated spinopelvic sagittal balance.

As LL decreases with spinal degeneration, the discrepancy between LL and PI, which is considered a constant, becomes larger [

2,

13]. As long as spinal deformity can be compensated for, spinopelvic sagittal balance is maintained by the compensatory mechanism in the spine [

3,

8]. The initial major compensatory mechanism at work in the early phase of this change in spinal alignment is an increase in PT due to posterior pelvic retroversion [

9,

14]. In the present study we similarly found a strong correlation between Lack of iLL and PT in Group C, with compensated spinopelvic sagittal balance.

With the progression of degeneration, Lack of iLL becomes greater, and as spinopelvic sagittal balance declines into the decompensated phase, compensatory alignment changes in the whole body are recruited [

14]. In group D with decompensated spinopelvic sagittal balance, we found a stronger correlation between Lack of iLL and TK, and recruitment of KF and ankle dorsiflexion in the maintenance of a standing posture. KF is the definitive and effective compensatory mechanism, and past reports have shown that ankle flexion is also an important compensatory mechanism, especially in the elderly [

5,

7,

15]. Obeid et al. [

5] reported a correlation between lack of theoretical LL and KF in a study of patients with major spinal deformity. Diebo et al. [

8] analyzed 161 adult patients with sagittal spinal malalignment and reported that as PI-LL increased, the contribution of TK and PT to the compensation cascade decreased and that of KF angle and pelvic shift increased. The correlation between Lack of iLL and KF angle was very weak in Group C, which supports the findings of these other studies. However, the analyses of these previous studies were limited to patients with spinal deformities, whereas the present study is the first, to our knowledge, to analyze a series of patients with no history of spinal treatment and to calculate the threshold for KF angle that indicates spinopelvic sagittal imbalance.

In the cutoff analysis using the ROC curve, we found that the KF angle indicating spinopelvic imbalance was 8.4 degrees. Hasegawa et al. [

14] classified their cohorts, which included healthy subjects and patients with spinal deformity, according to health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and reported significant differences in TPA, C2-7 kyphosis, PI-LL, PT, and KF between these groups. They also reported the threshold value of KF angle for severe disability to be 8 degrees, which is very similar to the cutoff value for KF angle determined in the present study. Additional validation studies are needed to determine if the cutoff value for KF in the present study is a relevant radiographic indicator of preferable outcomes related to HRQOL in the treatment of adult subjects with spinal deformities.

A limitation of this study is the lack of information on knee degenerative joint disease and range of motion of the knee because of the retrospective study design. The subjects in Group D with spinopelvic sagittal imbalance were older, and we cannot rule out that osteoarthritis or other diseases affecting knee joint range of motion might have affected the results of the analysis [

16].

5. Conclusions

The present study shows differences in the correlation strength between Lack of iLL and whole-body compensatory parameters between the two different phases of spinopelvic sagittal balance. In the subjects with compensated spinopelvic balance, there was a strong correlation between Lack of iLL and PT and a weak correlation between Lack of iLL and TK. In the subjects with decompensated spinopelvic sagittal balance, there was a stronger correlation between Lack of iLL and TK, and recruitment of KF and AA. The cutoff value for KF angle indicative of decompensated spinopelvic balance from ROC analysis was 8.4 degrees. Future studies will be needed to validate whether the cutoff value determined in this study can be used as a potential outcome measure in the treatment of spinal deformity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.O., H.N., T.K., K.I., M.T., M.M., S.I., N.S., Y.O. and S.I.; formal analysis, J.O.; investigation, J.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.O.; writing—review and editing, H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konan Kosei Hospital. IRB approval No. 2022-012(0478)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Diebo BG, Varghese JJ, Lafage R, Schwab FJ, Lafage V. Sagittal alignment of the spine: What do you need to know? Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015 Dec;139:295-301. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi T, Atsuta Y, Matsuno T, Takeda N. A Longitudinal Study of Congruent Sagittal Spinal Alignment in an Adult Cohort. Spine. 2004 Mar 15;29(6):671-6. [CrossRef]

- Barrey C, Roussouly P, Le Huec J-C, D’Acunzi G, Perrin G. Compensatory mechanisms contributing to keep the sagittal balance of the spine. Eur Spine J. 2013 Nov;22(6):834-41. [CrossRef]

- Le Huec JC, Charosky S, Barrey C, Rigal J, Aunoble S. Sagittal imbalance cascade for simple degenerative spine and consequences: algorithm of decision for appropriate treatment. Eur Spine J. 2011 Sep;20(5):699-703. [CrossRef]

- Obeid I, Hauger O, Aunoble S, Bourghli A, Pellet N, Vital J-M. Global analysis of sagittal spinal alignment in major deformities: correlation between lack of lumbar lordosis and flexion of the knee. Eur Spine J. 2011 Sep;20(5):681-5. [CrossRef]

- Schwab F, Lafage V, Patel A, Farcy J-P. Sagittal plane considerations and the pelvis in the adult patient. Spine. 2009 Aug 1;34(17):1828-33. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero E, Liabaud B, Challier V, Lafage R, Diebo BG, Vira S, et al. Role of pelvic translation and lower-extremity compensation to maintain gravity line position in spinal deformity. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016 Mar;24(3):436-46. [CrossRef]

- Diebo BG, Ferrero E, Lafage R, Challier V, Liabaud B, Liu S, et al. Recruitment of Compensatory Mechanisms in Sagittal Spinal Malalignment Is Age and Regional Deformity Dependent: A Full-Standing Axis Analysis of Key Radiographical Parameters. Spine. 2015 May 1;40(9):642-9. [CrossRef]

- Protopsaltis T, Schwab F, Bronsard N, Smith JS, Klineberg E, Mundis G, et al. TheT1 pelvic angle, a novel radiographic measure of global sagittal deformity, accounts for both spinal inclination and pelvic tilt and correlates with health-related quality of life. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Oct 1;96(19):1631-40. [CrossRef]

- Lafage R, Liabaud B, Diebo BG, Oren JH, Vira S, Pesenti S, et al. Defining the role of the lower limbs in compensating for sagittal malalignment. Spine. 2017 Nov 15;42(22):E1282-E8. [CrossRef]

- Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry disability index. Spine. 2000 Nov 15;25(22):2940-53.

- Aoki Y, Nakajima A, Takahashi H, Sonobe M, Terajima F, Saito M, et al. Influence of pelvic incidence-lumbar lordosis mismatch on surgical outcomes of short-segment transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015 Aug 20;16(1):213. [CrossRef]

- Lamartina C, Berjano P. Classification of sagittal imbalance based on spinal alignment and compensatory mechanisms. Eur Spine J. 2014 Jun;23(6):1177-89. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa K, Okamoto M, Hatsushikano S, Watanabe K, Ohashi M, Vital J-M, et al. Compensation for standing posture by whole-body sagittal alignment in relation to health-related quality of life. Bone Joint J. 2020 Oct;102(10):1359-67. [CrossRef]

- Jalai CM, Cruz DL, Diebo BG, Poorman G, Lafage R, Bess S, et al. Full-Body Analysis of Age-Adjusted Alignment in Adult Spinal Deformity Patients and Lower-Limb Compensation. Spine. 2017 May 1;42(9):653-61. [CrossRef]

- Murata Y, Takahashi K, Yamagata M, Hanaoka E, Moriya H. The knee-spine syndrome: association between lumbar lordosis and extension of the knee. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2003 Jan;85(1):95-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).