1. INTRODUCTION

Malaria remains a major public health threat, with morbidity and mortality rates on the rise in several parts of the world as revealed in latest editions of the World Malaria Report [

1,

2,

3]. Efforts to eliminate the disease are hampered in particular by the increasing spread of insecticide and antimalarial drug resistance [

2,

4,

5,

6], exacerbated by the complexity of malaria parasite populations and the lack of a broadly effective vaccine [

7,

8,

9]. Host responses to natural infection are often not sufficiently protective given their slow development rates, short half-lives and allele-specificity [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. It is known that repeated infection with malaria parasites or subclinical carriage of parasites for long durations can result in sustained natural antimalarial immunity, and that infection with multiple parasite clones can increase the breadth, especially of adaptive antibody responses, leading to stronger protection against subsequent malaria [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Multiclonal infections originate either from co-transmission by mosquito vectors of genetically different parasite clones in a single blood meal (co-infections) or from overlapping infection in cases of repeated exposure to the bite of infected mosquitoes (superinfections) [

21,

22]. Indeed, in areas of high perennial transmission of the most deadly form of malaria parasites,

P. falciparum, infection with multiple clones of the parasite is common as well as high prevalence of asymptomatic parasitaemia [

23]. Whether multiclonal infections occur as a result of waning natural immunity that allow for the expansion of multiple genetically distinct parasite clones, or due to the introduction of new parasite populations in the community remains not well understood. Therefore, understanding the association between multiclonal infection and host immune responses may be essential for predicting the risk of clinical malaria and monitoring success of malaria control interventions.

In this study, we sought to assess the prevalence and the host and parasite factors associated with multiclonal

P. falciparum infection in an area of high perennial transmission and high prevalence of asymptomatic malaria parasitaemia in Cameroon, one of 11 “high burden high impact” countries that accounted for 68% of the global estimated malaria cases and 70% of global estimated deaths in 2021 [

3]. The country can be stratified into three zones of varying malaria transmission intensity, with over 70% of its population residing in areas of high and perennial transmission of

P. falciparum [

24]. Data on the genetic diversity of

Plasmodium parasites in Cameroon is very limited, and none of the published work explored the host and parasite factors associated with polyclonal infection. We found a strong positive correlation between multiplicity of infection and parasite density, and that the frequency of polyclonal infection was highest in children and generally in participants with low levels of IgG antibodies against protective

P. falciparum antigens, suggesting the dependence of both parasite density and polyclonality on the underlying host adaptive immune responses.

2. Materials and methods

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Human Health Research of Cameroon (Ethical clearance N°: 2018/09/1104/CE/CNERSH/SP) and authorized by the Ministry of Public Health (D30-989/L/MINSANTE/SG/DROS). The field studies were also approved by local administrative authorities, including the senior divisional officer in Esse and village chiefs. Informed consent was obtained from participants over 19 years of age and from parents or legal representatives of children under the age of 19. Assent was also obtained from all children aged 12 to 19 years.

Study design and sample collection

This study was conducted in five villages (Afanetouana (Af), Koutou (Ko), Meboe (Me), Ondoundou (On) and Ntouessong (Nt)) in the locality of Esse, Central Region of Cameroon, and belonging to the Yembouni population group [

25]. The study area has been described previously [

26,

27] and, like all communities neighboring the city of Yaounde, malaria transmission in the area is perennial and hyperendemic [

24]. The blood samples were collected during a cross-sectional study conducted in November and December 2018. Participants were adults and children, excluding children under 2 years of age and pregnant women. Approximately 3 mL of venous blood was collected in EDTA-coated tubes and used for malaria diagnosis by rapid diagnostic test (RDT, Standard Q Rapid Test, SD Biosensor) and for blood hemoglobin quantification using an automated hemoglobinometer (Mission Hb, USA). Axillary temperature was also recorded for each participant. All febrile cases (axillary temperature ≥37.5°C) with confirmed parasitaemia by RDT were immediately treated with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) according to national guidelines.

Detection and quantification of Plasmodium species

The detection and quantification of infecting

Plasmodium species were performed by multiplex nested PCR and light microscopy, respectively [

27]. Briefly, thick blood films were prepared using 5 µl of whole blood samples, followed by Giemsa staining and examination under a 100x immersion oil lens. A blood slide was declared positive when a concordant result was obtained by at least two of three independent microscopists. Slides were declared negative if no parasites were detected after a count of 500 white blood cells. Parasite density was determined based on the number of parasites per at least 200 leucocytes counted on a thick film, assuming a total white blood cell count of 8000 cells/μL of whole blood.

Genomic DNA was extracted from dried blood spots (Whatman grade 3) containing 50 µl of whole blood using the Chelex method [

28], and used to screen for

Plasmodium species infections by multiplex nested PCR targeting the 18S ssrRNA genes of

P. falciparum,

P. ovale,

P. malariae, and

P. vivax, as described by Snounou

et al [

29]. For the first PCR reaction, 5 μL of genomic DNA were used in a 20 μL total volume reaction with 0.2 µM of

Plasmodium genus-specific outer primers and 10 µl of Platinum green Hot start PCR 2X master mix (Cat: 13000014, Invitrogen). Nested PCR was performed with 2 μL of the PCR product, 0.2 µM species-specific primers and 10 µl of Platinum green Hot start PCR 2X master mix. Both PCR steps were performed under the same cycling conditions, which included initial denaturation and enzyme activation at 95°C for 15 minutes, and 43 cycles of 95°C for 45 seconds and 55°C for 90 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR assays were performed using a SimpliAmp thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) and the different

Plasmodium species were identified on the basis of the size of the PCR product after analysis on 1.2% agarose gel under a UV transilluminator (Quantum, Vilber Lourmat). Asymptomatic infections were defined as the presence of

Plasmodium parasites in peripheral blood, detected by multiplex nested PCR, in the absence of fever (temperature < 37.5°C) at least 48 hours before enrollment into the study. Symptomatic infections were defined as positive for

Plasmodium infection by any one of three methods (RDT, thick smear microscopy, or multiplex nested PCR) and a history of fever (temperature ≥ 37.5 °C) within 48 hours before enrollment. Participants with negative results for all three tests were considered uninfected with malaria parasites.

Plasmodium falciparum genotyping using msp2 and polyα markers

P. falciparum genotyping was performed targeting two well-characterized polymorphic markers,

msp2 and

polyα as previously described [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. The primer sequences and amplification conditions for each marker are described in

Table 1.

All reactions were carried out in a final volume of 20 µL containing 200 nM of each primer, 4 µl of 5x Hot FIREpol blend master mix (Solis BioDyne) and nuclease-free water. In the first PCR, 5µl of purified DNA sample was used and in the nested reaction 2µl of amplicon was used. The

msp2 genotype was identified based on the size of the PCR products using a 2% agarose gel stained with 0.01% of ethidium bromide and analyzed under a UV transilluminator. Identification of the

polyα polymorphism was performed after SDS-PAGE on a 12% polyacrylamide gel. The amplification product was identified after staining the polyacrylamide gel with 0.01% ethidium bromide on a shaker at room temperature for 30 minutes and analyzed under a UV transilluminator. Expected heterozygosity (

He), which is a key determinant of population structure, representing the probability of being infected by two parasite populations with different alleles at a given locus was determined according to the formula

He = n / (n -1) * (1 -

) with n: number of isolates analyzed, and p: allele frequency of the i-th allele.

He values close to 0 indicate no genetic diversity, while an

He value close to 1 indicates high allelic diversity [

32,

36]. Complexity of infection, also known as multiplicity of infection (MOI), was defined as the number of infecting genotypes per sample per genotyping method, whereas overall MOI was defined as the highest number of alleles detected by either of these genotyping methods (

msp2 or

polyα). Samples with more than one allele (MOI>1) were classified as polyclonal infections, whereas those with a single allele by both genotyping methods were considered as monoclonal infections.

Anti-P. falciparum IgG antibody ELISA

Levels of plasma IgG to four highly reactive recombinant antigens: MSP-1p19, MSP3, MSP4p20, and EBA175 (MRA-1162) [

37,

38], and to two soluble antigen extracts: mixed-stage antigen (anti-

Pf ) and merozoite antigen (anti-MZ

) of

P. falciparum were measured by indirect ELISA. The soluble extracts were obtained from laboratory maintained

P. falciparum 3D7 parasites by freeze-thaw fractionation in PBS, pH 7.4 containing protease inhibitors, whereas the

P. falciparum Merozoite Surface Proteins were produced using a baculovirus insect cell expression system (MSP-1p19 and MSP-4p20) or in

E. coli (MSP3) [

37,

39,

40]. Microtiter plates (F96 CERT-Maxisorp) were coated with 100 µl of 2 mg/ml soluble antigen extract or 0.5 mg/ml recombinant antigen diluted in 0.1 M bicarbonate buffer and incubated overnight at 4˚C. After washing with PBS, pH 7.2, and blocking with 1% BSA in PBS, pH 7.2 for 1 h, the plates were further incubated for 1 h with plasma samples diluted 1/250 in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 1%BSA. Plasma from 10 unexposed European blood donors (EFS, France) was used as naive controls, while a pool of highly reactive IgG from adults living in Yaounde was used as a positive control. A goat anti-human IgG antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:20,000) was used as secondary antibody and the resulting complexes were detected using TMB as a chromogenic substrate (ThermoScientific, USA). The reaction was stopped by adding 50 µl of 2N sulfuric acid solution, and optical densities (OD) were measured using a spectrophotometer at 450 nm wavelength. Data were presented as OD ratios (average OD of the sample/mean OD of unexposed samples) prior to statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/MP 13.0 and GraphPad Prism 8.0.1. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to determine the host and parasite factors associated with polyclonal infections in the study area. Only associated variables with p<0.05 were included in the multivariate analysis. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the median between two groups. Spearman's test was used to determine the correlation between two quantitative parameters. All participants <15 years of age were classified as children, whereas participants aged ≥15 years were considered adults.

3. Results

Frequency of polyclonal P. falciparum infection in the study population

Of 353 individuals tested for malaria parasites by multiplex nested PCR, 316 (89.5%) were positive for

P. falciparum infection, of which 88.6 % were

Pf mono-infections, 8.9 % were

Pf +

Pm, 1.9 % were

Pf +

Po, and 0.6% were

Pf +

Pm +

Po. The demographic and parasitological characteristics of the study population are described elsewhere [

27]. Genotyping of the

Pf-positive samples resulted in 250 (79.1%) positive amplifications at the

msp2 locus and 215 (68.0%) at the

polyα locus, for a combined genotyping success rate of 88.0% (278/316). Of the 38 PCR positive but non-genotyped samples, 23 (60.5%) were submicroscopic infections and 15 (39.5%) were low density infections (mean parasitaemia: 273 p/µl, range: 38-1288 p/µl). The characteristics of the genotyped and non-genotyped population are presented in

Table 2.

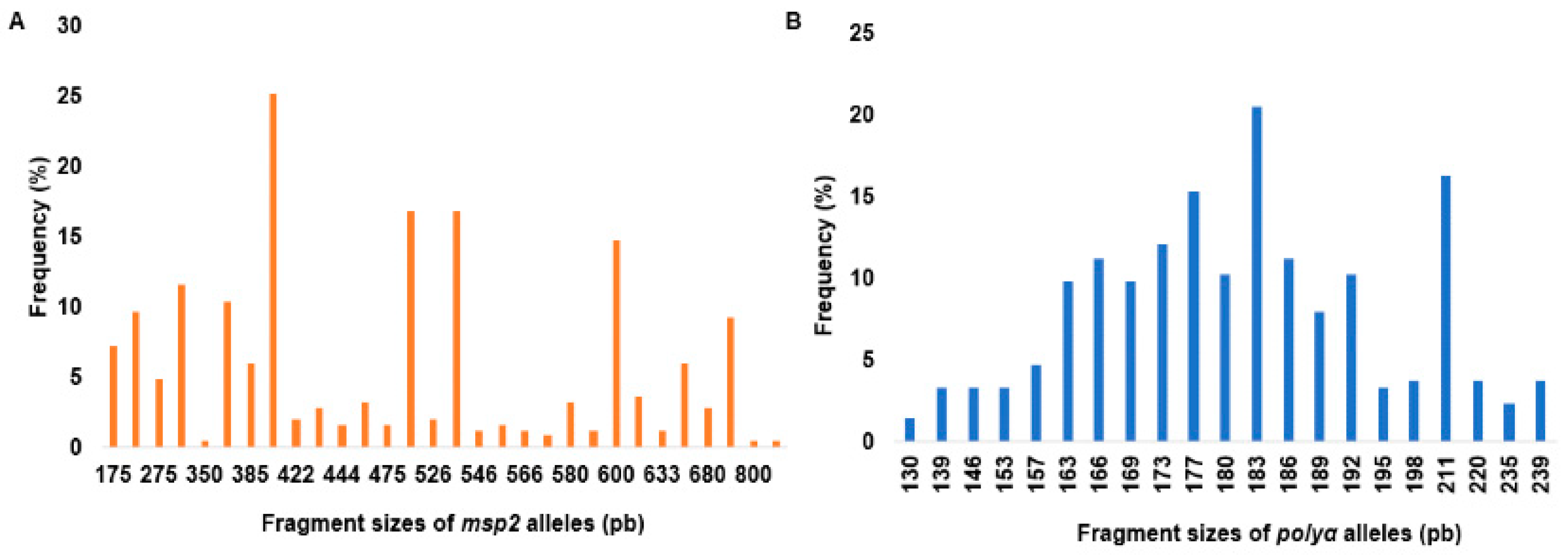

As shown in

Figure 1, a total of 30 alleles appearing at frequencies between 0.4% and 25.2% were detected at the

msp2 locus, whereas 21 alleles were identified at the

polyα locus at frequencies between 1.4% and 20.5%.

The mean number of parasite clones per infected participant (MOI) was 1.70 (range: 1-8 clones) by msp2 genotyping and 1.67 (range: 1–6 clones) by polyα microsatellite analyses, for a combined MOI of 1.95 in the study population. The mean MOI was 1.58 (range: 1–5 clones) in individuals with submicroscopic infection and 2.1 (range: 1–8 clones) in the microscopy positive subjects (p<0.0001). It was 1.91 (range: 1-6 clones) in the asymptomatic individuals compared to 2.08 (range: 1-8 clones) in the symptomatic population (p = 0.6931), and it was 2.3 (range: 1-8 clones) in children compared to 1.60 (range: 1-5) in adults (p <0.0001). The mean number of clones per infected subject varied according to locality with Ntouessong having the highest mean MOI (MOI: 2.3, range: 1-8 clones), followed by Afanetouana (MOI: 2.1, range: 1-6 clones), Ondoundou (MOI: 1.9, range: 1-5 clones), Meboe (MOI: 1.77, range: 1-5 clones) and Koutou (MOI: 1.64, range: 1-4 clones). Expected heterozygosity (He) was generally high (0.54-0.91 for the msp2 alleles and 0.58-0.87 for the polyα marker) in all the villages studied. The mean expected heterozygosity was 0.82 considering the msp2 alleles and 0.85 when considering the polyα microsatellite marker. These results indicate a high genetic diversity of malaria parasites in the study population, with children and microscopically positive participants carrying the highest number of parasite clones.

The frequency of polyclonal infection in the study population, taking into account both allelic markers, was 60.1% (167/278), of which 80.2% were asymptomatic infections. The frequency was 37.21% in submicroscopic and 70.31% in the microscopy positive individuals (p<0.0001). It was 60.36% in asymptomatic participants as against 58.93% in the febrile subjects (p = 0.8450). Approximately 63.47% (106/167) of individuals with polyclonal infections had parasitaemia greater than the population median, compared to only 28.82% (32/111) of high parasitaemia among individuals with monoclonal infections. The frequency of polyclonal infection varied with age and participant’s village. It was 88.24% in children under five years old, 76.56% in children between 5-10 years old, 66.67% in 10-15 years old, and 46.85% in children and adult greater than or equal to 15 years of age. The frequency of polyclonal infection was highest in Ntouessong (74.3%), followed by Afanetouana (65.0%), Ondoundou (63.8%), Meboe (49.4%) and Koutou (47.7%). Together, these data suggest a high frequency of polyclonal P. falciparum infection in the study area and its probable association with age, parasite density and participant’s village.

Associated factors of P. falciparum polyclonal infections in the study area

Univariate and multivariate analyses were undertaken to identify host demographic and parasite factors associated with polyclonal infection in the study area. As shown in

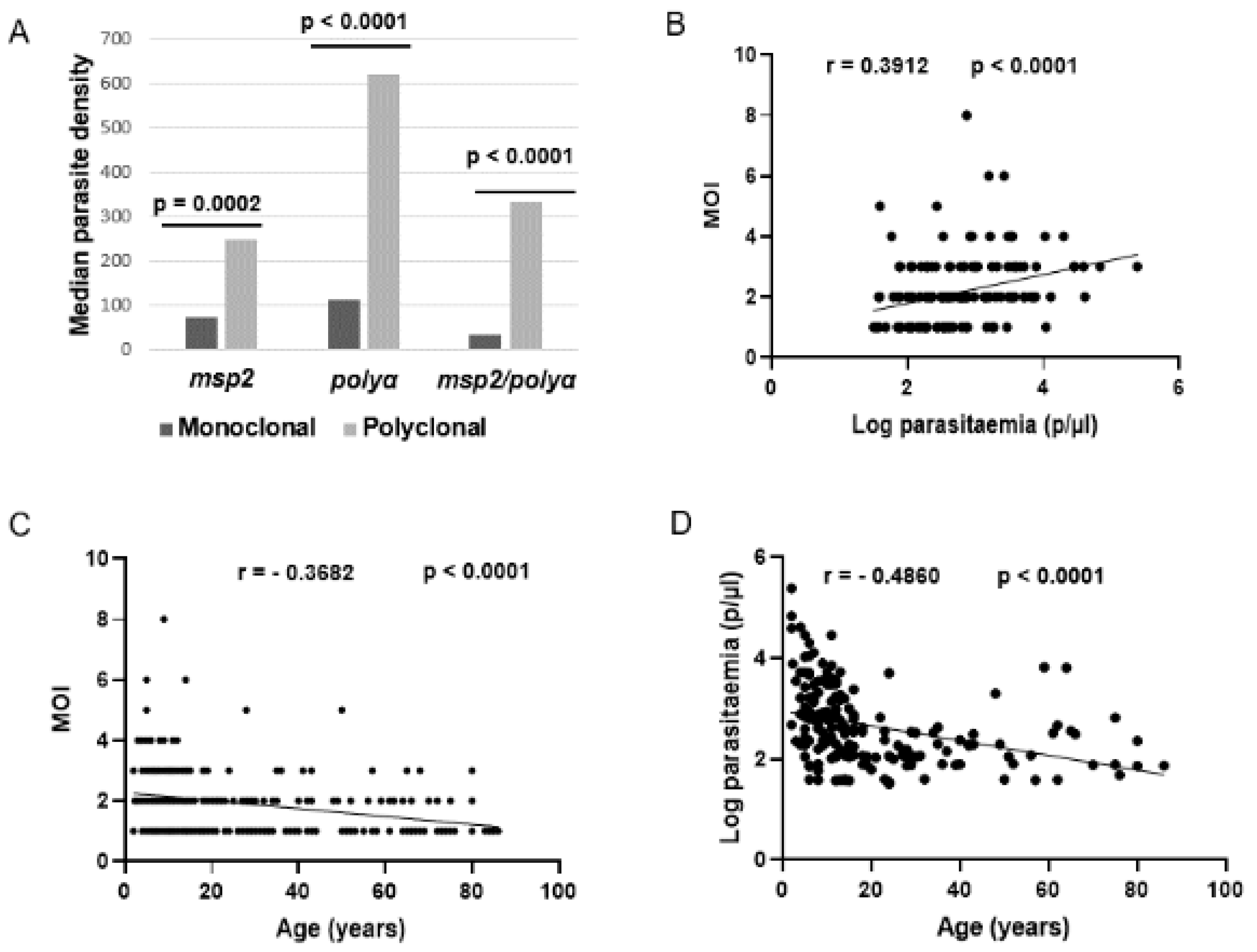

Table 3, infection with two or more parasite clones was independently associated with age, participant’s village, and parasite density.

Indeed, polyclonal infections were 3 times more likely to occur in children than adults (OR = 3.241, p< 0.0001) and were 4 times more likely to occur in participants with high parasite densities than those with low parasitaemia (OR = 4. 290, p< 0.0001). Median parasite densities were generally higher in participants with polyclonal infections than those with monoclonal infections, and the number of parasite clones increased significantly with parasite density (r = 0.3912, p<0.0001) (

Figure 2). In contrast, the number of parasite clones as well as parasite densities decreased significantly with age (r = -0.3682, p<0.0001 and r = -0.4860, p<0.0001, respectively) (

Figure 2). These findings suggest a direct link between parasitaemia and MOI, and their possible influence by a host age-related factor.

Frequencies of polyclonal infection were similar between bed-net users and non-users (OR = 1.176, p = 0.5082), suggesting a minor role of host exposure in acquisition of polyclonal infection. Additionally, polyclonal infections were not associated with clinical status (asymptomatic or symptomatic) or with time to previous fever episode (cf

Table 3). Together, these findings suggest a lack of role of polyclonal infections in protection against clinical malaria in infected individuals.

Association of P. falciparum polyclonal infection with underlying acquired immunity

To investigate the impact of underlying host antibody responses on the complexity of infection and frequency of polyclonal infection in the area, plasma IgG to four highly reactive

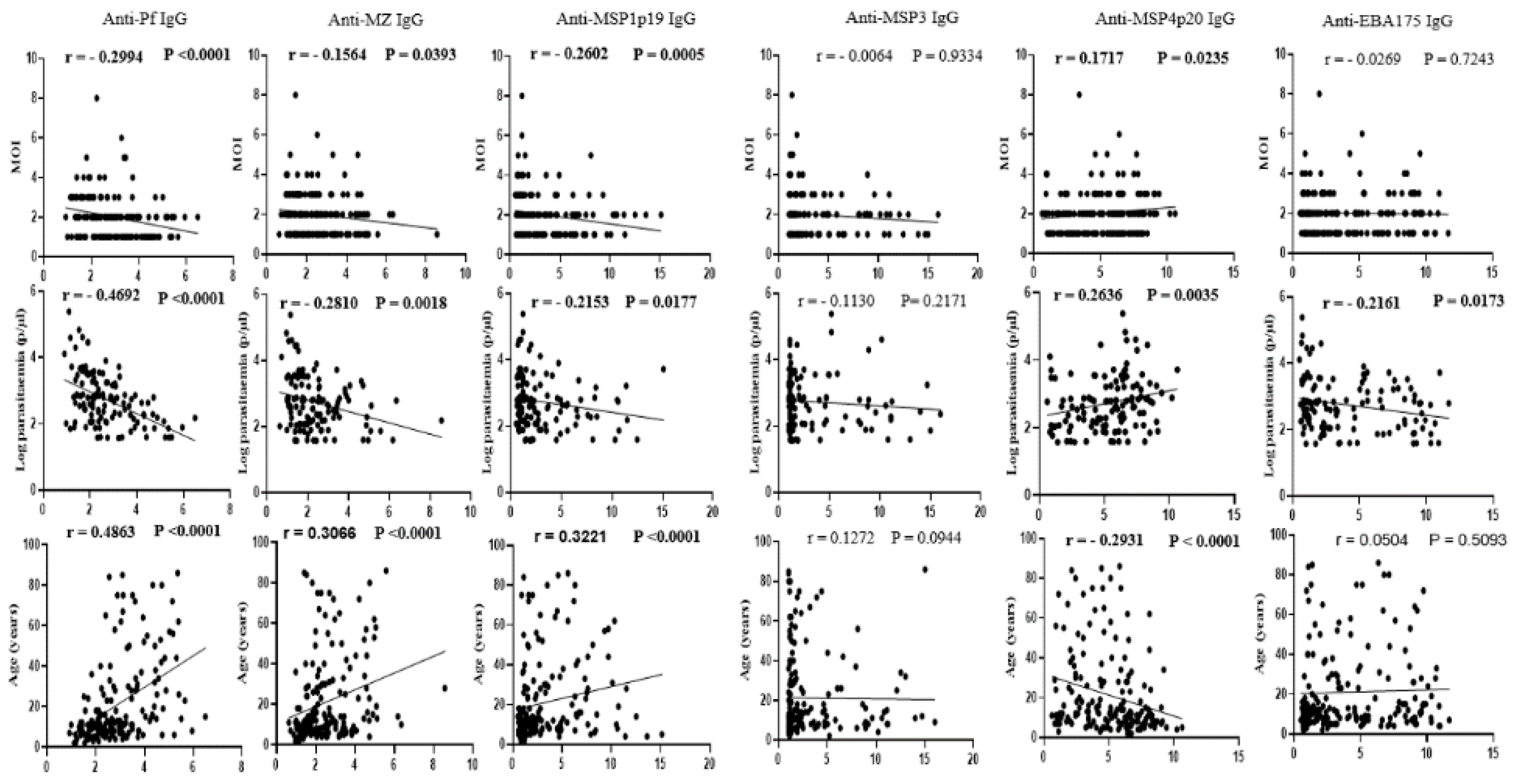

P. falciparum recombinant antigens (MSP1p19, MSP3, MSP4p20 and EBA175) and two antigen extracts (mixed stage extract and merozoite extract) were assessed by indirect ELISA. As shown in

Figure 3, the number of parasite clones per infected sample correlated negatively with IgG levels to five of these antigens (MSP1p19: r = -0.2602, p = 0.0005; MSP3: r = -0.0064, p = 0.9334; EBA175: r = -0.0269, p = 0.7243; anti-Pf: r = -0.2994, p<0.0001; and anti-MZ: r = -0.1564, p = 0.0393), but correlated positively with the IgG level to the recombinant MSP4p20 protein (r = 0.1717, p = 0.0235).

Similarly, a negative correlation was observed between parasite density and IgG levels against the five antigens (MSP1p19: r = -0.2153, p = 0.0177; MSP3: r = -0.1130, p = 0.2171; EBA175: r = -0.2161, p = 0.0173; anti-Pf: r = -0.4692, p<0.0001; and anti-MZ: r = -0.2810, p = 0.0018), whereas a positive correlation was observed for IgG levels to MSP4p20 (r = 0.2636, p = 0.0035). Plasma IgG levels increased with age for all five antigens (MSP1p19: r = 0.3221, p<0.0001; MSP3: r = 0.1272, p = 0.0944; EBA175: r = 0.0504, p = 0.5093; anti-Pf: r = 0.4863, p<0.0001; and anti-MZ: r = 0.3066, p<0.0001), and decreased for the MSP4p20 antigen (r = -0.2931, p<0001). Overall, these data suggest a potential role for underlying host antibody responses in limiting blood parasite densities as well as the number of infecting parasite clones per individual, with the highest parasitemia and number of clones observed generally in participants with low plasma levels of anti-Plasmodium IgG.

4. Discussion

Studies undertaken in malaria-endemic areas worldwide, particularly in areas of perennial

P. falciparum transmission, suggest high prevalence of polyclonal infections and its implication in protection against recurrent malaria attacks [

17,

19,

20]. This study aimed to determine the prevalence and associated risk factors of polyclonal

P. falciparum infections in an area of high perennial transmission and high prevalence of asymptomatic malaria parasitaemia in Cameroon. To increase the analytical sensitivity of the genotyping approach, two well-characterized allelic markers (

msp2 and

polyα) were amplified by nested PCR and samples were considered polyclonal if multiple alleles were detected by either one or both genotyping methods. Association of the underlying host adaptive immune responses with polyclonality (frequency and MOI) was assessed by measuring total IgG levels against several highly reactive

P. falciparum antigens and against total soluble extracts (merozoite and mixed-stage) of a laboratory strain (

P. falciparum 3D7 strain).

Consistent with published data on the genetic diversity of malaria parasites in hyperendemic areas [

32,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45], we observed high prevalence of polyclonal infections in the study area and a positive association with parasitaemia. Approximately 29% of individuals with monoclonal infections also had parasite densities above the population median, indicating a partial or indirect relationship between parasitaemia and clone number. Indeed, both the number of clones and parasite density negatively correlated with age, but was differentially associated with the sampling location, with the highest mean parasitaemia observed in Meboe while the highest mean clone number was found in Ntouessong. These findings are consistent with an independent relationship between parasitaemia and clone number, and a possible role for an age-related host factor in controlling both parasitaemia and clone numbers, albeit in an independent manner.

Parasitaemia and clone number correlated negatively with IgG levels against multiple highly reactive and protective antigens of

P. falciparum, as well as against the merozoite soluble extract. Indeed, our study is the first to report an association between complexity of

P. falciparum infection and anti-

Plasmodium antibody responses. In a previous study in Nigeria [

46], the authors found no correlation between IgG levels against

PfCSP, a circumsporozoite protein and marker of exposure to

P. falciparum, despite a strong correlation with age. In general, with the exception of IgG levels against the MSP4p20 antigen, IgG levels increased with age, consistent with the acquisition of antimalarial immunity in long-term residents of malaria endemic zones [

10,

12] . The positive correlation observed between anti-MSP4p20 antibody levels and parasitaemia or MOI, and the negative correlation observed with age are consistent with the recognized role of this antigen as a strong marker of

P. falciparum infection [

47,

48]. Overall, our data suggest a possible implication of host antibody responses in the control of both parasitaemia and clone number in the study population. Indeed, increased levels of protective antibodies, particularly against polymorphic parasite proteins may limit the expansion of certain clones, resulting in lower multiplicity of infection and possibly lower parasitaemia in some individuals. In addition, anti-

Plasmodium antibodies are generally clonotype-specific and may be short-lived [

10,

15,

38]. Therefore, decreased levels of genotype-specific antibodies in previously exposed individuals may allow such genotypes to thrive following a reinfection, resulting in polyclonal infection.

In conclusion, the findings reported in this work are consistent with a dependence in areas of high parasite diversity of both parasitaemia and clonality on the degree of protective antibody immunity at the time of infection. A major drawback in this study concerns the limited sample size relative to the total population of the study area and our failure to genotype up to 12% of the PCR-confirmed infections, which may have skewed some of the factors studied. Further study of the parasite determinants of multiclonal host immunity could lead to the discovery of more effective vaccines to accelerate malaria elimination efforts globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A. and T.L.; Methodology, M.F.B., B.F., E.E., F.M., C.D., R.K., G.C., N.M., C.S., S.K. and N.E.; Resources, R.P.; Data curation, M.F.B. and B.F.; Formal analysis, M.F.B., B.F., E.E., C.E.E.M., and G.C.; Writing-original draft preparation, M.F.B. and B.F.; Writing-review and editing, N.E., S.E.N., C.E.E.M., R.P., J.P.A.A., T.L. and L.A.; Supervision, L.A., T.L., J.P.A.A., and F.E.; Funding acquisition, L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a capacity building grant from the Institute Pasteur International Division to LA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Cameroon National Ethics Committee for Human Health Research of Cameroon (Ethical clearance N°: 2018/09/1104/CE/CNERSH/SP) of September 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the field team and the laboratory staff at Centre Pasteur du Cameroun and, most importantly, residents of the Esse Health district in Cameroon who participated in this study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

-

WHO World Malaria Report 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2019; ISBN 978-92-4-156572-1.

-

WHO World Malaria Report 2020 20 Years of Global Progress and Challenges; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-001579-1.

- WHO World Malaria Report 2022. 2022.

- Dhorda, M.; Amaratunga, C.; Dondorp, A.M. Artemisinin and Multidrug-Resistant Plasmodium Falciparum – a Threat for Malaria Control and Elimination. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 2021, 34, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Cha, S.; Jacobs-Lorena, M. New Weapons to Fight Malaria Transmission: A Historical View. Entomological Research 2022, 52, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, R.; Kissoon, S.; Lakan, V.; Kheswa, N. Rolling Back Malaria in Africa – Challenges and Opportunities to Winning the Elimination Battle. S Afr Med J 2019, 109, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckee, C.O.; Gupta, S. Modelling Malaria Population Structure and Its Implications for Control. In Modelling Parasite Transmission and Control; Vol. 673, pp. 112–126; Michael, E., Spear, R.C., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4419-6063-4. [Google Scholar]

- Naung, M.T.; Martin, E.; Munro, J.; Mehra, S.; Guy, A.J.; Laman, M.; Harrison, G.L.A.; Tavul, L.; Hetzel, M.; Kwiatkowski, D.; et al. Global Diversity and Balancing Selection of 23 Leading Plasmodium Falciparum Candidate Vaccine Antigens. PLoS Comput Biol 2022, 18, e1009801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouattara, A.; Barry, A.E.; Dutta, S.; Remarque, E.J.; Beeson, J.G.; Plowe, C.V. Designing Malaria Vaccines to Circumvent Antigen Variability. Vaccine 2015, 33, 7506–7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpogheneta, O.J.; Duah, N.O.; Tetteh, K.K.A.; Dunyo, S.; Lanar, D.E.; Pinder, M.; Conway, D.J. Duration of Naturally Acquired Antibody Responses to Blood-Stage Plasmodium Falciparum Is Age Dependent and Antigen Specific. Infect Immun 2008, 76, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, K.P.; Marsh, K. Naturally Acquiredimmunity to Plasmodiumfalciparum. immunoepidemiology 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, J.T.; Hollingsworth, T.D.; Reyburn, H.; Drakeley, C.J.; Riley, E.M.; Ghani, A.C. Gradual Acquisition of Immunity to Severe Malaria with Increasing Exposure. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2015, 282, 20142657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, K.; Roe, M.; Fowkes, F.J. The Role of Naturally Acquired Antimalarial Antibodies in Subclinical Plasmodium Spp. Infection. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2022, 111, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.T.; Griffin, J.T.; Akpogheneta, O.; Conway, D.J.; Koram, K.A.; Riley, E.M.; Ghani, A.C. Dynamics of the Antibody Response to Plasmodium Falciparum Infection in African Children. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2014, 210, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yman, V.; White, M.T.; Asghar, M.; Sundling, C.; Sondén, K.; Draper, S.J.; Osier, F.H.A.; Färnert, A. Antibody Responses to Merozoite Antigens after Natural Plasmodium Falciparum Infection: Kinetics and Longevity in Absence of Re-Exposure. BMC Med 2019, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, L.E.; Acquah, F.K.; Ayanful-Torgby, R.; Oppong, A.; Abankwa, J.; Obboh, E.K.; Singh, S.K.; Theisen, M. Dynamics of Anti-MSP3 and Pfs230 Antibody Responses and Multiplicity of Infection in Asymptomatic Children from Southern Ghana. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereczky, S.; Liljander, A.; Rooth, I.; Faraja, L.; Granath, F.; Montgomery, S.M.; Färnert, A. Multiclonal Asymptomatic Plasmodium Falciparum Infections Predict a Reduced Risk of Malaria Disease in a Tanzanian Population. Microbes and Infection 2007, 9, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rono, J.; Osier, F.H.A.; Olsson, D.; Montgomery, S.; Mhoja, L.; Rooth, I.; Marsh, K.; Färnert, A. Breadth of Anti-Merozoite Antibody Responses Is Associated With the Genetic Diversity of Asymptomatic Plasmodium Falciparum Infections and Protection Against Clinical Malaria. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2013, 57, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondén, K.; Doumbo, S.; Hammar, U.; Vafa Homann, M.; Ongoiba, A.; Traoré, B.; Bottai, M.; Crompton, P.D.; Färnert, A. Asymptomatic Multiclonal Plasmodium Falciparum Infections Carried Through the Dry Season Predict Protection Against Subsequent Clinical Malaria. J Infect Dis. 2015, 212, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumner, K.M.; Freedman, E.; Mangeni, J.N.; Obala, A.A.; Abel, L.; Edwards, J.K.; Emch, M.; Meshnick, S.R.; Pence, B.W.; Prudhomme-O’Meara, W.; et al. Exposure to Diverse Plasmodium Falciparum Genotypes Shapes the Risk of Symptomatic Malaria in Incident and Persistent Infections: A Longitudinal Molecular Epidemiologic Study in Kenya. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, 73, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, C.; Sinha, A. Plasmodium and Malaria: Adding to the Don’ts. Trends in Parasitology 2021, 37, 935–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.; Volkman, S.; Daniels, R.; Schaffner, S.; Sy, M.; Ndiaye, Y.D.; Badiane, A.S.; Deme, A.B.; Diallo, M.A.; Gomis, J.; et al. R H: A Genetic Metric for Measuring Intrahost Plasmodium Falciparum Relatedness and Distinguishing Cotransmission from Superinfection. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.; Koepfli, C. Systematic Review of Plasmodium Falciparum and Plasmodium Vivax Polyclonal Infections: Impact of Prevalence, Study Population Characteristics, and Laboratory Procedures. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio-Nkondjio, C.; Ndo, C.; Njiokou, F.; Bigoga, J.D.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Etang, J.; Ekobo, A.S.; Wondji, C.S. Review of Malaria Situation in Cameroon: Technical Viewpoint on Challenges and Prospects for Disease Elimination. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESSE COUNCIL ESSE MUNICIPAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN. 2013, 209.

- Essangui, E.; Eboumbou Moukoko, C.E.; Nguedia, N.; Tchokwansi, M.; Banlanjo, U.; Maloba, F.; Fogang, B.; Donkeu, C.; Biabi, M.; Cheteug, G.; et al. Demographical, Hematological and Serological Risk Factors for Plasmodium Falciparum Gametocyte Carriage in a High Stable Transmission Zone in Cameroon. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogang, B.; Biabi, M.F.; Megnekou, R.; Maloba, F.M.; Essangui, E.; Donkeu, C.; Cheteug, G.; Kapen, M.; Keumoe, R.; Kemleu, S.; et al. High Prevalence of Asymptomatic Malarial Anemia and Association with Early Conversion from Asymptomatic to Symptomatic Infection in a Plasmodium Falciparum Hyperendemic Setting in Cameroon. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2021, 106, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plowe, C.V.; Djimde, A.; Bouare, M.; Doumbo, O.; Wellems, T.E. Pyrimethamine and Proguanil Resistance-Conferring Mutations in Plasmodium Falciparum Dihydrofolate Reductase: Polymerase Chain Reaction Methods for Surveillance in Africa. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1995, 52, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snounou, G.; Viriyakosol, S.; Jarra, W.; Thaithong, S.; Brown, K.N. Identification of the Four Human Malaria Parasite Species in Field Samples by the Polymerase Chain Reaction and Detection of a High Prevalence of Mixed Infections. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology 1993, 58, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajogbasile, F.V.; Kayode, A.T.; Oluniyi, P.E.; Akano, K.O.; Uwanibe, J.N.; Adegboyega, B.B.; Philip, C.; John, O.G.; Eromon, P.J.; Emechebe, G.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Plasmodium Falciparum in Nigeria: Insights from Microsatellite Loci Analysis. Malar J 2021, 20, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.J.C.; Su, X.-Z.; Bockarie, M.; Lagog, M.; Day, K.P. Twelve Microsatellite Markers for Characterization of Plasmodium Falciparum from Finger-Prick Blood Samples. Parasitology 1999, 119, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metoh, T.N.; Chen, J.-H.; Fon-Gah, P.; Zhou, X.; Moyou-Somo, R.; Zhou, X.-N. Genetic Diversity of Plasmodium Falciparum and Genetic Profile in Children Affected by Uncomplicated Malaria in Cameroon. Malar J 2020, 19, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.; Kassa, M.; Mekete, K.; Assefa, A.; Taye, G.; Commons, R.J. Genetic Diversity of the Msp-1, Msp-2, and Glurp Genes of Plasmodium Falciparum Isolates in Northwest Ethiopia. Malar J 2018, 17, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranford-Cartwright, L.C.; Taylor, J.; Umasunthar, T.; Taylor, L.H.; Babiker, H.A.; Lell, B.; Schmidt-Ott, J.R.; Lehman, L.G.; Walliker, D.; Kremsner, P.G. Molecular Analysis of Recrudescent Parasites in a Plasmodium Falciparum Drug Efficacy Trial in Gabon. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1997, 91, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Khan, A.; Israr, M.; Shah, M.; Shams, S.; Khan, W.; Shah, M.; Siraj, M.; Akbar, K.; Naz, T.; et al. Genomic Miscellany and Allelic Frequencies of Plasmodium Falciparum Msp-1, Msp-2 and Glurp in Parasite Isolates. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukari, Z.; Okonu, R.; Nyarko, S.B.; Lo, A.C.; Dieng, C.C.; Salifu, S.P.; Gyan, B.A.; Lo, E.; Amoah, L.E. The Diversity, Multiplicity of Infection and Population Structure of P. Falciparum Parasites Circulating in Asymptomatic Carriers Living in High and Low Malaria Transmission Settings of Ghana. Genes 2019, 10, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbengue, B.; Fall, M.M.; Varela, M.-L.; Loucoubar, C.; Joos, C.; Fall, B.; Niang, M.S.; Niang, B.; Mbow, M.; Dieye, A.; et al. Analysis of Antibody Responses to Selected Plasmodium Falciparum Merozoite Surface Antigens in Mild and Cerebral Malaria and Associations with Clinical Outcomes. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2019, 196, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor Yman; James Tuju; Michael T. White; Gathoni Kamuyu; Kennedy Mwai; Nelson Kibinge; Muhammad Asghar; Christopher Sundling; Klara Sondén; Linda Murungi; et al. Distinct Kinetics of Antibodies to 111 Plasmodium Falciparum Proteins Identifies Markers of Recent Malaria Exposure. NATURE COMMUNICATIONS, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, S.; Petres, S.; Holm, I.; Fontaine, T.; Rosario, S.; Roth, C.; Longacre, S. Soluble and Glyco-Lipid Modified Baculovirus Plasmodium Falciparum C-Terminal Merozoite Surface Protein 1, Two Forms of a Leading Malaria Vaccine Candidate. Vaccine 2006, 24, 5997–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oeuvray, C.; Bouharoun-Tayoun, H.; Gras-Masse, H.; Bottius, E.; Kaidoh, T.; Aikawa, M.; Filgueira, M.; Tartar, A.; Druilhe, P. Merozoite Surface Protein-3: A Malaria Protein Inducing Antibodies That Promote Plasmodium Falciparum Killing by Cooperation with Blood Monocytes. Blood 1994, 84, 1594–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, M.; Msangeni, H.A.; Pedersen, B.V.; Shayo, D.; Bedker, R. Diversity of Plasmodium Falciparum Populations and Complexity of Infections in Relation to Transmission Intensity and Host Age: A Study from the Usambara Mountains, Tanzania. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2001, 95, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diouf, B.; Diop, F.; Dieye, Y.; Loucoubar, C.; Dia, I.; Faye, J.; Sembène, M.; Perraut, R.; Niang, M.; Toure-Balde, A. Association of High Plasmodium Falciparum Parasite Densities with Polyclonal Microscopic Infections in Asymptomatic Children from Toubacouta, Senegal. Malar J 2019, 18, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyedeji, S.I.; Bassi, P.U.; Oyedeji, S.A.; Ojurongbe, O.; Awobode, H.O. Genetic Diversity and Complexity of Plasmodium Falciparum Infections in the Microenvironment among Siblings of the Same Household in North-Central Nigeria. Malar J 2020, 19, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogier, C.; Trape, J.-F.; Bonnefoy, S.; Ntoumi, F.; Mercereau-Puijalon, O.; Contamin, H. Age-Dependent Carriage of Multiple Plasmodium Falciparum Merozoite Surface Antigen-2 Alleles in Asymptomatic Malaria Infections. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1995, 52, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondo, P.; Derra, K.; Rouamba, T.; Nakanabo Diallo, S.; Taconet, P.; Kazienga, A.; Ilboudo, H.; Tahita, M.C.; Valéa, I.; Sorgho, H.; et al. Determinants of Plasmodium Falciparum Multiplicity of Infection and Genetic Diversity in Burkina Faso. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, F.; Tögel, E.; Beck, H.-P.; Enwezor, F.; Oettli, A.; Felger, I. Analysis of Plasmodium Falciparum Infections in a Village Community in Northern Nigeria: Determination of Msp2 Genotypes and Parasite-Specific IgG Responses. Acta Tropica 2000, 74, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffi, D.; Touré, A.O.; Varela, M.-L.; Vigan-Womas, I.; Béourou, S.; Brou, S.; Ehouman, M.-F.; Gnamien, L.; Richard, V.; Djaman, J.A.; et al. Analysis of Antibody Profiles in Symptomatic Malaria in Three Sentinel Sites of Ivory Coast by Using Multiplex, Fluorescent, Magnetic, Bead-Based Serological Assay (MAGPIXTM). Malar J 2015, 14, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Richie, T.L.; Stowers, A.; Nhan, D.H.; Coppel, R.L. Naturally Acquired Antibody Responses to Plasmodium Falciparum Merozoite Surface Protein 4 in a Population Living in an Area of Endemicity in Vietnam. Infect Immun 2001, 69, 4390–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).